Abstract

Low competitiveness is a common denominator of historically Roman Catholic countries. In contrast, historically Protestant countries generally perform better in education, social progress, and competitiveness. Jesus Christ described the true and false prophets coming on his behalf, as follows: “Ye shall know them by their fruits”. Inspired by this parable, this paper explores the relations between religious systems (‘prophets’) and social prosperity (‘fruits’). It asks how Protestantism influences prosperity as compared to Roman Catholicism in Europe and the Americas. Most empirical studies have hitherto disregarded the institutional influence of religion. Taking the work of Max Weber as their starting point, they have instead emphasised the cultural linkage between religious adherents and prosperity. This paper tests various correlational models and draws on a comprehensive conceptual framework to understand the institutional influence of religion on prosperity in Europe and the Americas. It argues that the uneven contributions of Roman Catholicism and Protestantism to prosperity are grounded in their different historical and institutional foundations and in the theologies that are pervasive in their countries of influence.

1. Introduction

Institutions play a crucial role in the prosperity of societies. Historical evidence shows that institutions are shaped by cultural variables and vice-versa (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Inglehart and Baker 2000; Alesina and Giuliano 2015). In the Americas, these institutional relations can be traced back to European colonisation (Engerman and Sokoloff 2002), and religion has underpinned the cultural values that shape institutions.

At least two dimensions of religion’s influence on prosperity are worth close attention: the institutional and the cultural (Manow 2002, p. 9). However, most empirical works studying religion as a key determiner of prosperity have merely paid scant attention to the institutional effects of religion. Instead, they have mainly concentrated on the cultural influence of religious affiliations (often using the proportion of adherents as a sole indicator of religion) (Acemoglu et al. 2001; La Porta et al. 1999; Hofstede 2001).

This traditional research paradigm, which focuses on the cultural influence of religion, stems from Max Weber’s groundbreaking The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Weber 1905). Weber argued that the Protestant Reformation initiated modern capitalism and that Protestant societies economically outpaced Catholic ones (Weber 1905, p. 133). His assertion, that religion exerts a cultural influence on prosperity through a particular work ethic, has been fiercely criticised over the last century. To this day, the ensuing debate has remained polarised. Numerous quantitative studies have linked religion and prosperity indicators, either supporting (mainly on the cross-country level) or refuting (mainly on the sub-national level) Weber’s basic claim (see, among others: Granato et al. 1996; Hayward and Kemmelmeier 2011; Delacroix and Nielsen 2001; Cantoni 2009; Di Matteo 2015).

Typically, cross-country empirical approaches have ignored decisive Church–State power relations. For instance, the historical agreements (concordats) between individual countries and the Roman Catholic Church–State have been neglected. Moreover, the sociological explanations in several empirical studies are often either Weberian or purely hypothetical, neither further developed nor related to other disciplines and historical sources. An obvious hiatus is evident in the sociology of religion. Critical approaches are lacking, in particular, that is, ones that take “issues of domination and inequality seriously” (Hjelm 2014, p. 857).

This restricted scope means that the interrelations between prosperity and religion tend to be trivialised or misunderstood when analysing religion as a development factor. For instance, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) criticised Weber’s theory of Protestant ethics as one that “does not work”. Likewise, Hofstede (2001) stated that economic industrialisation brings people to believe in more “inclusive” religious systems, such as Protestantism, yet not vice versa. However, such an approach is ahistorical (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Historical timeline of some key religio-political events in Christendom (Source: Author’s chart; based on the theoretical framework of this study). Among others, sources include Woodberry (2012), Miller (2012), Acemoglu et al. (2011), Snyder (2011), Bruce (2007), Berman (2003), Witte (2002), Heussi (1991), D’Aubigne (1862), and Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 340 AD).

Protestantism not only broke the political (as well as the institutional and economic) hegemony of the Roman Catholic Church–State, but also arrested its growing influence in Europe. The modern state and secular institutions emerged from these processes (which later also influenced democracy, the American Constitution, and the French and Industrial Revolutions) (Snyder 2011; Woodberry 2012; Becker et al. 2016; Witte 2002) (see Table 1 and Section 7).

Recent research largely confirms the Reformation’s key role in Europe’s economic and political trajectory, although for very different reasons than those highlighted by Weber (Woodberry 2012; Becker et al. 2016, p. 22). Thus, the notion of a “better” Protestant work ethic might grossly oversimplify an intricate question: Why do Protestant societies have better prosperity indicators than Roman Catholics or Orthodox ones? This paper argues that a particular work ethic is, at best, no more than one of many contributing factors.

La Porta et al. (1998) found that hierarchical Christian religions (i.e., Orthodoxy or Roman Catholicism) unfavourably affect social development. In contrast, various factors account for the robust empirical associations between Protestantism and prosperity: the rise and spread of education and printing (Becker and Woessmann 2009; Androne 2014); the development of democratic institutions (Woodberry 2012); and, the weakening of hierarchical structures (La Porta et al. 1999; Volonté 2015). Therefore, the effects of Christianity on prosperity vary depending on the different institutional emphases that a dominant religious denomination places on a given society.

Insights from disciplines, such as political science (Manow and van Kersbergen 2009), international relations (Snyder 2011), or law (Witte 2002; Berman 2003), have been crucial to understanding the institutional influence of religion on prosperity patterns. Yet, these findings have often not been integrated into the array of explanations that are provided by empirical studies associating religion and prosperity. Therefore, it is necessary to build a comprehensive transdisciplinary theory based on the findings of different disciplines. In turn, this will enhance their explanatory power.

This paper seeks to establish such “synthesised coherence” by interconnecting “work that previously had been considered unrelated” (Golden-Biddle 2007, p. 33).

Christianity has been central to Western civilisation. Nevertheless, the diverse historical trajectories of the various Christian denominations first established and later determined different sets of societal norms and institutions. This study explores the institutional influence of Christianity on prosperity in present-day Europe and the Americas. It is part of extensive doctoral research on qualitative prosperity models and detailed case studies. Therefore, some sections contain “empirical expectations” for further research.

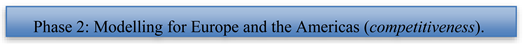

This paper has nine sections: Section 2 presents the research model. Section 3 defines prosperity as a concept linked to competitiveness in the countries studied and associated with biblical notions. Section 4 briefly diagnoses prosperity in Europe and the Americas and establishes that historically Protestant countries perform better than Roman Catholic ones. Section 5 studies the prosperity-religion nexus, reviews some leading empirical works, and shows the influential and often disregarded role of institutional religion on prosperity. Section 6 discusses institutions as prosperity triggers. Section 7 examines the historical influence of religion on different legal traditions in Europe and the Americas. Section 8 presents the materials and methods that were used. Section 9 discusses the empirical results, while Section 10 offers some concluding remarks.

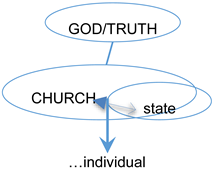

2. Research Model

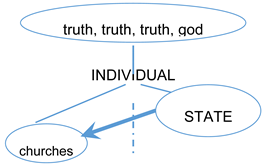

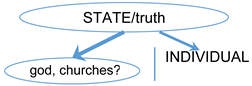

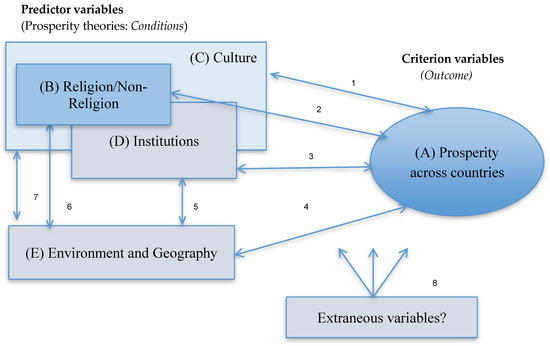

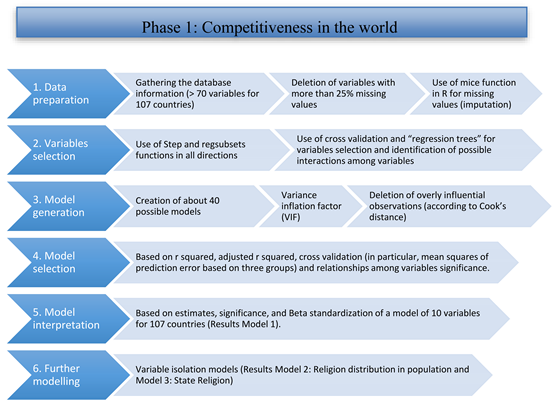

Figure 1 synthesises the logic underlying this study by interrelating the factors and variables of interest. This model, which structures this paper, is of course not exhaustive. Some variables or conditions are embedded within others, and vice versa (see Supplementary Materials).

The variables and factors that are considered in this study are interdependent. This integration helps reconcile previous, mutually exclusive disciplinary approaches. It also highlights the need to explain the religion–prosperity nexus through the interlinkages between diverse factors, theories, and disciplines, rather than through mono-causal explanations of prosperity. The neo-classical economic approach hithero prevalent in the literature considered history, geography, ecology, and culture (including religion and social norms) as “residuals”, thus leaving little room for explicit modelling of these features (Michalopulos and Papaioannou 2017).

Each of these separate theories may contain “a grain of truth” in understanding prosperity imbalances across countries (Moran et al. 2007, p. 3). For example, geography and environment theories explain how seasonal lands may provide better conditions for developing a society and its economy (Diamond 1997; Sachs 2001). Institutional theory has explained how institutions model the prosperity of societies and perpetuate equality loops or concentrations of wealth (North 1990; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012). Cultural theory has focused on how cultural variables (that traditionally include religion) influence prosperity (Landes 1999; Hofstede 2001).

However, some relations are not studied here, since they are less relevant (e.g., environmental influences on culture, and vice-versa. This paper does not theorise the influence of environment and geography, language, and ethnicities on prosperity for reasons of scope, although some of these factors appear in the empirical results. It instead considers the sociology of religion and theological disciplines through an institutional and legal lens. Finally, it also draws on international relations, political science, law, and economics.

3. Outcome: Prosperity and the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI)

This paper defines prosperity in its broader sense, success in general, rather than in purely economic terms (i.e., GDP). Therefore, it links the concepts of “prosperity” and “competitiveness” (GCI), which both result from related identical conditions. The World Economic Forum has developed the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) as a comprehensive proxy of prosperity tracking the performance of nearly 140 countries in terms of twelve categories: institutions, technological readiness, innovation, higher education and training, health and primary education, business sophistication, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, labour market efficiency, market size, financial market development, and goods market efficiency. The World Economic Forum identified such categories as determinants of productivity through empirical and theoretical research, which in turn is the primary determinant of economic growth and prosperity (World Economic Forum 2014).

Thus, the World Economic Forum (2014) defines competitiveness as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of a country. The level of productivity, in turn, sets the level of prosperity that can be reached by an economy.” (p. 4). Consequently, prosperity and competitiveness (GCI) are here often used indiscriminately.

The GCI is a highly comprehensive measure that places countries on an objective scale of prosperity. The fact that institutions, education, transparency, and other factors are already included within the GCI (or prosperity) presents a significant advantage for studies like this one. First, close theoretical and empirical relations exist among these variables. Accordingly, they all belong to the same kind of “prosperity phenomenon” (GCI). Consequently, their causality requires no further discussion, as they are not isolated but aggregated in the GCI. Second, such aggregated factors (GCI) allow for focusing on other (exogenous) determinants of the “competitiveness phenomenon”. Therefore, this paper focuses on the potential exogenous variables that are not included in the GCI (e.g., legal origin and state religion, as background proxies of the influence of religion on institutions).

“Prosperity” is often associated with obeying moral commandments throughout the Holy Scriptures (see Table 5). For instance, “Keep therefore the words of this covenant, and do them, that ye may prosper in all that ye do” (Deuteronomy 29: 9, King James Version). The opposite (the consequence of disobedience) relates to misfortunes: “if thou wilt not hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to observe to do all his commandments and his statutes which I command thee this day; that all these curses shall come upon thee, and overtake thee” (Deuteronomy 28: 15).

Protestant countries have applied the moral principles of the Decalogue in their legal systems (Table 5). In contrast, Catholic countries have mostly based their legal systems on Roman and Canon law, which mostly derives from the Catholic Sacraments and Greek philosophy, rather than from the biblical commandments (Table 4).

The next section finds clear distribution patterns of prosperity in the countries that are studied here: high competitiveness, in countries with a Protestant tradition, and lower competitiveness in countries with a Roman Catholic or Orthodox background.

Empirical expectation: Countries applying the Sola Scriptura principle of the Protestant Reformation may be expected to exhibit higher prosperity rates than others. Such application should be reflected in Protestant-influenced legal origins (i.e., German, English, or Scandinavian).

4. Diagnosis: Prosperity in Europe and the Americas

A review of prosperity indicators in Europe and the Americas reveals that historically Protestant countries have done better than predominantly Roman Catholic ones (Inglehart and Baker 2000; Becker et al. 2016; La Porta et al. 1999).

4.1. Competitiveness (GCI) in Europe and the Americas

Switzerland achieves the highest competitiveness score worldwide. Next, the so-called “advanced economies” are in the top 90–100% (United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Northern Europe). The 70–80% most competitive countries include Italy, Spain, Portugal, Austria, and Ireland. Latin America and the Caribbean countries rank among the 40–80% most competitive (World Economic Forum 2014) (see Supplementary Materials for details).

4.2. Social Progress in Europe and the Americas

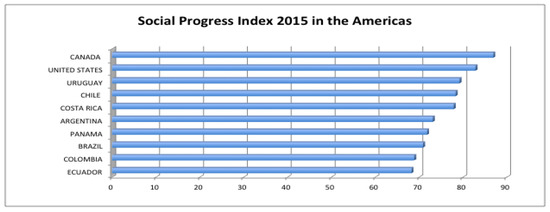

Economic performance alone (GDP) does not fully explain social progress (variables correlate 0.78) (Porter et al. 2015). The Social Progress Index (SPI) is a comprehensive framework for measuring social progress independently of, and complementary to, GDP. The SPI is a robust and holistic framework for determining national social and environmental performance (Porter et al. 2015).

Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland score the highest SPI rates in the world (around 88 each). Mediterranean countries score around 80. All Latin American countries reach average distribution scores, which range from 79 (Uruguay) to 60 (Guyana) (Ibid).

Figure 2 shows the differences in SPI scores in the Americas. Following the historical trend, Canada and the United States have better prosperity conditions (i.e., SPI and GCI) than all Latin American countries. Uruguay exhibits the highest SPI value in Latin America.

Except for some countries (e.g., Uruguay and Chile), the SPI and GCI confirm an old view: “…Latin America is, after all, the only part of the world which is both Christian and underdeveloped” (Levine 1981, p. 35). The next section addresses the prosperity-religion nexus as a feature that help to better explain the imbalanced SPI and GCI differences among countries.

5. Prosperity and Religion

The link between prosperity and religion is undeniable. For instance, in the United States—the second most competitive country worldwide according to the World Economic Forum (2014)—, religion accounts for almost one-third of the national GDP (USD 4.8 trillion annually; Grim and Grim 2016). Only the revenues of faith-based organisations in the US (USD 378 billion annually) represent more than the global annual revenues of Apple and Microsoft combined (Ibid.).

However, empirical research regarding prosperity determinants typically neglects the influence of religion (McCleary and Barro 2003, p. 760). As a determinant, religion suffers from similar mainstream disregard in other disciplines, such as law (Berman 2003; Witte 2002), international relations (Snyder 2011), or political science (Manow and van Kersbergen 2009).

Institutional Influence of Religion on Prosperity

The institutions and cultural values of historically Protestant countries considerably differ from Roman Catholic, Orthodox, or Islamic societies. The enduring effects of Protestantism on prosperity in Europe today, for instance, owe more to the institutional influence of religion in the longue durée than to the number of its adherents, which has significantly diminished over time (Inglehart and Baker 2000, p. 49). For instance, Protestantism’s association with prosperity is partly explained on its historical focus on education and human capital building (Becker and Woessmann 2009).

The interactions between institutions and culture have partly determined the prosperity of nations. Empirical evidence suggests that causality exists in both directions. Culture may change in different ways, depending on the type of institutions, while institutions may work differently, depending on the cultural context (Alesina and Giuliano 2015, p. 938).

Therefore, the entangled cultural and institutional influences of religion sometimes complicate empirical differentiation (Barro and McCleary 2005). However, religion cannot be reduced to the proportion of adherents, although most of the literature on religion as a prosperity determinant has been largely confined to this indicator.

Barro and McCleary (2005) developed an empirical approach to institutional religion in their classification of “State religion”. However, “State religion” is mostly also related to population adherence and it does not account, for instance, for the international agreements (i.e., concordats) between the Roman See and individual countries.

A key feature of other relevant studies (Becker and Woessmann 2009; Becker et al. 2016; Woodberry 2012; Gill 1998) has been to identify how Protestantism has destabilised the institutional hegemony of Roman Catholicism. This has proven more important than the effects of religious believers per se.

Becker et al. (2016) concluded that Protestantism encouraged a wide range of societal developments, based on their comparative examination and state-of-the-art systematic synthesis. Overall, most empirical studies on the consequences of the Reformation associate it with the positive development of governance and the economy. Subsequently, most empirical studies confirm the positive impact of Protestantism on prosperity based on different variables and on various spatial and temporal configurations (Becker et al. 2016).

Economic prosperity has been robustly linked with secularisation and declining levels of religiosity (Barro and McCleary 2003; Inglehart and Baker 2000). Secularisation precedes economic growth, which means that prosperity has not caused secularisation in the past (Ruck et al. 2018). Section 7.3.4 discusses Protestantism as an institutional precursor of secularism.

Thus, most empirical findings to date contradict the prevailing Roman Catholic ideology, which has insisted (however, without providing empirical evidence) on restoring what it praises as a “prosperous and peaceful medieval society” (Restrepo 1939; Ratzinger and Pera 2006). Medieval Christianity allowed for the Roman Church–State to create a theocratical order, in which papal power established a hierarchical society where spiritual power prevailed over temporal power. This Roman Catholic ideal means that the ecclesiastical hierarchy determines the legal principles and basic norms of collective life (Figueroa 2016, p. 155). This perspective calls for reviewing the distinct institutional ideologies of historical Protestantism and Roman Catholicism as the roots of their differences.

6. Institutions as Triggers of Prosperity

Institutions are “the rules of the game in a society” (North 1990, p. 3). They can be either formal (i.e., official and openly codified; e.g., constitutional laws) or informal (i.e., unwritten or socially shared rules) (Helmke and Levitsky 2004). Informal institutions are frequently more persistent than the formal ones (North 1997) and they pertain to how laws are enforced (Woodruff 2006).

The quality of institutions has been theoretically and empirically linked to prosperity (and thus also to transparency) outcomes (North 1990; La Porta et al. 1999; Acemoglu et al. 2001; Acemoglu and Johnson 2005; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Williamson 2000). Such studies have credibly associated empirical evidence and theory. Therefore, institutions are widely accepted as playing a determinant (causal) role in the prosperity of societies even if alternative interpretations exist (Woodruff 2006).

However, several problems arise when considering institutions inter alia as triggers of prosperity:

- Scant agreement exists on how to empirically measure formal or informal institutions. Different studies measuring institutions with varied methods measure different things. Sometimes, even gauging the outcome in isolation from other factors is challenging (Woodruff 2006).

- Endogeneity issues plague the causal approaches of institutions to prosperity, although, to a lesser extent, the effect of political institutions on transparency. However, previous treatments of endogeneity have not been convincing (Persson and Tabellini 2003; Woodruff 2006; Kunicová 2006).

- It is not entirely clear which institutions are fundamental to prosperity-transparency processes (Woodruff 2006, p. 106).

- Formal institutions have little effect on broad prosperity outcomes. However, informal institutions matter and they have a more significant effect (Glaeser et al. 2004; Woodruff 2006; Treisman 2000).

- Although quite strong associations often exist, the causal arrow may point in both directions (from prosperity/transparency to institutional choice and from institutions to prosperity/transparency) (Rose-Ackerman 2006, p. xxv).

- Informal institutions are the most difficult to measure (and change), since they are largely determined by history (Woodruff 2006, p. 121).

Thus, research on institutions and prosperity/transparency has not provided conclusive evidence of causality. The strongest evidence relates to the impact of underlying social structures (informal institutions), which is highly difficult to address, both in prospective and in policy terms (Lambsdorff 2006; Woodruff 2006; Rose-Ackerman 2006).

In practical terms, institutions and transparency/trust may all have coincided with prosperity, as empirical evidence exists for arguing causality in both directions (Fukuyama 1995; Uildriks 2009; Morris 2003; Armony 2004). Therefore, prosperity, transparency (corruption’s opposite), trust, and institutions are inseparable concepts. Ethical transparency/trust values promoting institutional stability and prosperity is one causal cyclical logic that might be expected (Fukuyama 1995).

History and culture have shaped current institutional structures (Acemoglu et al. 2001; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Rose-Ackerman 2006). At the same time, empirical evidence also shows that institutional structures shape cultural values (i.e., trust and civic norms) (Uildriks 2009, p. 7); (Alesina and Giuliano 2015). In any event, religion has played a crucial role in corroborating both cultural values and institutions (Arruñada 2009; Manow 2002; Paldam 2001; Treisman 2000; Inglehart and Baker 2000).

Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) have explained how inclusive institutions create inclusive markets, incentives, and opportunities for prosperity. Inclusive institutions create positive feedback loops, which prevent an elite’s efforts to undermine them. However, throughout its history, Latin America has experienced a negative institutional feedback loop, which has perpetuated corruption, mistrust, and elitist-extractive institutions (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Uildriks 2009).

If political institutions are key (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012), who creates them? Lawyers and policy makers have moral and religious backgrounds (i.e., historically, these are predominantly Protestant in North America and Roman Catholic in Latin America). However, the influence of such values, but, more importantly, the institutional influence of the Church on those elites, is neglected in such works.

On this evidence, it is therefore essential to recognise which revolutions created better institutions. We also need to ask which triggers changed an old regime into a new status quo. Thus, countries that had not fully adopted the principles of such revolutions preserved elements of the old regime. These notions are explored below.

7. Legal Traditions and Prosperity in Europe and the Americas

Countries in Europe and the Americas have either transplanted or developed their legal systems from few legal traditions, rather than writing them from scratch (Watson 1974; La Porta et al. 1998, p. 1115). Thus, the different legal rules, procedures, and institutions at the national and sub-national levels share traditional characteristics that permit classification into groups or families. Along these lines, a legal tradition can be defined as a set of deeply rooted, historically conditioned attitudes about the nature of law, about the role of law in the society and the polity, about the proper organization and operation of a legal system, and about the way law is or should be made, applied, studied, perfected, and taught. The legal tradition relates the legal system to the culture of which it is a partial expression (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 2).

The most widespread legal traditions worldwide are first, Roman civil law, which includes French and other European and Latin American systems; second, common law, which includes most Anglo-Saxon systems; and third, socialist law, which comes from former and current socialist countries (including China and Cuba). The historical dominance of Roman law resulted from Roman imperialism and conquest. Likewise, the current dominance of Roman civil law and of the common law traditions in the modern world “is the direct result of European imperialism in earlier centuries” (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 5) (Table 2). Additionally, such traditions have also spread across the world through borrowing or imitation (e.g., Japan voluntarily adopted the German legal tradition; La Porta et al. 1998, p. 1115). Today, Roman civil law is represented in the French, German, and Scandinavian legal systems (ibid) (see Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Legal traditions in Europe and the Americas (adapted from Witte 2002; Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007; La Porta et al. 2008).

Table 3.

Comparison of institutional performance between different legal traditions (adapted from La Porta et al. 1998, 1999, 2008; World Economic Forum 2014; Transparency International 2016; Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007).

Typically, Southern (Mediterranean) Europe and Latin America have French law. Northern Europe has mostly German, Scandinavian, or English common law. North America inherited English common law. Post-Soviet states have a socialist legal tradition, but most of these countries returned to French civil law after the fall of the Berlin Wall (La Porta et al. 2008, p. 289).

Table 2 presents the most important legal traditions in Europe and the Americas from the Middle Ages to the present. From left to right, Roman and canonical legal traditions chronologically progressed through the centuries. They did not abruptly end after the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, but percolated down after the various revolutions. All legal traditions incorporate Roman law in some form. From bottom to top, a colour gradient represents the closeness to Roman and canon law traditions (ranging to purple). Those legal traditions that are more distant from Roman and canon law (ranging to green) are shown towards the bottom of the table.

Roman and Roman Catholic canon law traditions have defined the institutional status quo or the ancien régime in Europe and the Americas. Violent national revolutions that were directed against the existing legal system gradually interrupted this hegemony in favour of more transcendental views of justice (above all in the last five centuries). Successive national revolutions have reformed and renewed the legal traditions (in some countries more than in others) of the still pervasive and surviving Roman and Catholic canon law regime. Every country in Europe and the Americas traces its legal system back to a revolution (Berman 2003, pp. 16–17). The following sections explain each of these traditions in chronological order.

7.1. Legal Traditions and Current Institutional Performance

The long-term persistence of legal traditions affects institutional performance and therefore also prosperity (Volonté 2015). Table 3 summarises some of the performance indicators of otherwise distinct legal traditions. The French, German, and Scandinavian legal systems belong to the tradition of Roman civil law (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007). Yet, they are all different. Germanic, and, in particular, Scandinavian, legal systems descend less from Roman law than from the French tradition (Zweigert and Kotz, as cited in La Porta et al. 1998, p. 1119). German and the above all Scandinavian legal systems were influenced by the Lutheran Reformation, which modified the foundational principles of Roman (and particularly of canon) law to a certain extent.

French civil law derives from the French Revolution, which also intended to transform the influence of Roman and canonical law. However, this transformation was not always possible due to the inertia of the tradition of Roman law for French Revolution jurists. Moreover, for example, the transformation of canon law was not automatically transplanted to most Latin American countries, which adopted French legal principles after gaining independence (Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007). Several Latin American countries signed concordats with the Roman Church–State after their independence, thus subordinating their civil law to canon law and granting explicit privileges to the Roman Catholic Church–State (Salinas Araneda 2013).

As explained below, most countries having French legal origins also have Roman Catholicism as their dominant religion. Likewise, countries with a socialist legal origin are more likely to exhibit a significant presence of Orthodox religions. Typically, countries of English, German, or Scandinavian legal origin have historically been linked to Protestantism and they are also the most prosperous (La Porta et al. 1999, p. 244) (see Table 3).

7.2. The Roman Civil Law Tradition

The Roman civil law tradition can be traced as far back as the Twelve Tables in ancient Rome (450 B.C). Table 2 and Table 3 show that, mostly modern French law, and, to a lesser extent, German and Scandinavian law currently represent the tradition of Roman civil law. Today, French civil law is both the most influential and also the most widespread system across the world (i.e., it is predominant in Latin America, Southern Europe, and across Asia and Africa). It precedes international law (i.e., the legal developments of the European Union and UN) and it even prevails in a few enclaves of the “common law world” (Louisiana, Quebec, and Puerto Rico) (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, pp. 2–3; La Porta et al. 2008, p. 289). La Porta et al. characterise French civil law, as follows:

[…] originates in Roman law, uses statutes and comprehensive codes as a primary means of ordering legal material […]. Dispute resolution tends to be inquisitorial rather than adversarial. Roman law was rediscovered in the Middle Ages in Italy, adopted by the Catholic Church for its purposes, and from there formed the basis of secular laws in many European countries.(La Porta et al. 2008, p. 289)

Different successive subtraditions constitute modern civil law: (1) Roman civil law (from the Roman Empire); (2) Canon law (from the Roman Catholic Church–State); (3) Commercial law (where pragmatic Italian merchants serve as judges); (4) the influence of revolutions (i.e., German, French, American); and, (5) legal science (descending from the various revolutions) (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007); (Berman 2003).

The first three subtraditions (Roman, canonical, and commercial law) are the fundamental historical sources of institutions, concepts, and procedures in “civil law countries”. In such countries, these subtraditions embody the essential modern codes (typically, these are civil, commercial, and penal, and they belong either to civil or to criminal procedure) (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 14).

Roman and canonical law have the highest historical relevance and they are directly related to religion, institutions, and prosperity.

7.2.1. Roman Civil Law

Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo (2007) characterise Roman law as

the greatest contribution that Rome has made to the Western civilization, and Roman ways of thinking have certainly percolated into every Western legal system. In this sense, all Western lawyers are Roman lawyers. In civil law nations, however, the influence of Roman civil law is much more pervasive, direct, and concrete than it is in the common law world.(Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 11)

Roman law was compiled and codified in the sixth century A.D under Justinian in the Corpus Juris Civilis. It is the most fundamental part both of the European legal tradition (especially in the Mediterranean Region) and of Latin America’s. Today, the civil codes of these countries demonstrate “the influence of Roman law and its medieval and modern revival” (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, pp. 10–11).

7.2.2. Roman Catholic Jurisprudence (Canon Law)

The pan-European Roman Church–State became the first modern state. It established a body of law that was systematised and compiled in Gratian’s Decretum (1140), which was entitled “A Concordance of Discordant Canons” (Berman 2003, p. 4). Ever since its introduction, the canonical law of the Roman Catholic Church–State has strongly influenced civil law. For instance, it was applied across Europe and thus influenced the jus commune of the European states. Notably, it includes various “forged documents treated for centuries as though they were genuine” (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, pp. 11–12).

Likewise, the Roman Catholic sacraments inspired medieval Catholic canonists and moralists to devise entire legal systems. The sacraments provided the framework for organising some of the legal institutions of the Church and society in the Middle Ages (Table 4). However, not all canonical law can be subsumed under the sacraments (Witte 2002, pp. 169–70).

Table 4.

Examples of medieval canon laws supported by Roman Catholic sacraments (adopted from Witte 2002, pp. 169–70).

Moreover, the development of natural law is central to Roman Catholic theology. In particular, Greek philosophy and Roman law—rather than the Scriptures—, influenced natural law (Gula 2002, pp. 120–21; Selling 2018, p. 9). Importantly, it is through natural law that the Catholic Church–State claims the rightness or wrongness of human conduct. The Catholic Church–State bases such claims on its trust in the human capacity to discern and to choose between right or wrong, regardless of religious affiliation (Gula 2002, pp. 120–21). Natural law is, for Roman Catholicism, a reflection of divine law and is only accessible to human reason through the traditions of the Church and sacred texts (Berman 2003, p. 73). The Roman Church–State “has appealed to natural law as the basis for its teachings pertaining to a just society, sexual behaviour, medical practice, human life, religious freedom, and the relationship between morality and civil law…” (Gula 2002, pp. 120–21).

Contrary to Gula’s (2002) idealistic appreciation, the current application of canon law has enabled the Roman Church–State, for instance, to leave the sexual abuse that was committed by Catholic priests unpunished and uncompensated. In Pennsylvania (United States), thousands of sexual abuse complaints have been kept in a “secret archive” that is only accessible to the responsible bishop under the Code of Canon Law. The FBI analysed Diocesan files and found a recurrent scheme for “concealing the truth”. Thus, the Roman Catholic hierarchy applies various protective measures: (1) it uses euphemisms rather than concrete language to describe sexual assaults; (2) it does not conduct genuine investigations with properly trained staff; (3) it sends priests for “evaluation” at church-run psychiatric treatment centres to create a semblance of integrity; (4) it fails to disclose why a priest needs to be removed, or tells his parishioners that he is on “sick leave” or suffering from “nervous exhaustion”; (5) it keeps covering the priest’s housing and living expenses, even if he continues to abuse children; (6) it transfers the priest “to a new location where no one will know he is a child abuser”; and finally, and most significantly; (7) it fails to notify the police (Grand Jury of Pennsylvania 2018, pp. 2–3).

7.3. Protestantism, Revolutions, and Law

This section reviews the historical influence of Protestantism, and of the various subsequent revolutions, on the different legal traditions.

7.3.1. The Sixteenth-Century German-European Revolution

In 1517, Martin Luther and other Reformers initiated a process that culminated in the abolition of Roman Catholic ecclesiastical jurisdiction in future Protestant countries (i.e., England and the Scandinavian countries) (Berman 2003, p. 6). Luther, a canon law expert, condemned Aquinas’s Aristotelian theology and most of the Catholic sacraments due to their lack of biblical foundations (Berman 2003); (Witte 2002).

Likewise, in Luther’s Ninety-five Theses of 1517, and in subsequent debates, he exposed a long list of injustices inherent in canon laws. He also unmasked the “fallacious legal foundation” of papal authority and the “myriad inconsistencies” between the “human laws and traditions” of the Roman Church–State versus the Scriptures (Berman 2003, p. 74). Luther said that the Roman Church should not be a lawmaking institution and emphasised:

In the entire canon law of the pope there are not even two lines which could instruct a devout Christian, (…) it would be a good thing if canon law were completely blotted out, from the first letter to the last, especially the [papal] decretals. More than enough is written in the Bible about how we should behave in all circumstances. […] Unless they abolish their laws and ordinances and restore to Christ’s churches their liberty and have it taught among them, they are to blame for all the souls that perish under this miserable captivity, and the papacy is truly the kingdom of Babylon and of the very Antichrist.(LW 44:179, 202–3, as cited in Witte 2002, p. 55)

Moreover, Luther directly attacked the moral authority of the Roman law (and its lawyers) as part of the same Babylonian system:

“Jurists are bad Christians” (WA TR 3, No. 2809b); “Every jurist is an enemy of Christ” (WA TR 3, Nos. 2837, 3027); and “I shit on the law of the pope and of the emperor, and on the law of the jurists as well”.(WA 49:302 as cited in Witte 2002, p. 2)

Thus, what began as a reformation of the Church and theology rapidly expanded into a reformation of the law and the state, in Germany and beyond (i.e., in Northern Europe, and also later in North America). The key incentive was to deconstruct canon law for the sake of the Gospel and, on this basis, to reconstruct “civil law on the strength of the Gospel” (Witte 2002, p. 3).

Accordingly, the Lutheran Reformation initially abolished medieval Roman and canon law in sixteenth-century Germany. Luther considered this process as imperative for various reasons: Roman and canon law fostered papal tyranny and thus enjoyed unbridled powers of legislation, adjudication, and administration. Second, this law was abusive and self-serving, and, most damningly, granted the clergy special privileges, exemptions, and immunities that elevated it above the laity. Third, it served as an instrument of greed and exploitation to support the luxury and bureaucracy of the Roman Church (LW 31:341, as cited in Witte 2002, pp. 55–56).2 Moreover, since Roman Catholic natural law was founded on the human ability to discern good and evil (Selling 2018); (Gula 2002), its refutation by Protestantism also had a biblical foundation:

The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: Who can know it?(Jeremiah 17:9).

Why should ye be stricken any more? ye will revolt more and more: the whole head is sick, and the whole heart faint.(Isaiah 1:5)

For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh,) dwelleth no good thing: for to will is present with me; but how to perform that which is good I find not. For the good that I would, I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do.(Romans 7:18–19)

Therefore, Protestant jurists considered the Gospel the best source of natural knowledge, given the explicit scriptural claims of the human inability to discern good from evil (Witte 2002, p. 169). Luther, though above all his followers (Melanchthon, Eisermann, and Oldendorp), considered the Bible the supreme source of law for earthly life. Accordingly, they produced a new jurisprudence, one that is theologically based on biblical moral principles, upon which they interpreted subordinate species of legal rules (Berman 2003, p. 8). Consequently, Lutheran jurists laid particular emphasis on the biblical Ten Commandments to ground their jurisprudence, contrary to Catholic canonists, who attached greatest importance to the seven sacraments (Berman 2003); (Witte 2002; see and compare Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 5.

Moral biblical law (associated with prosperity when obeyed or with misfortunes when disobeyed) and its legal application in Protestant countries (adapted from The Holy Bible, King James Version; see Witte 2002; Berman 2003).

However, Lutheran jurists also had to adapt traditional canon laws, which subsequently fell under the control of civil authorities (Witte 2002, pp. 83–84). Therefore, not all Protestant, positive law can be subsumed under the Ten Commandments. It may, in fact, have other biblical or Roman or canonical origins (Witte 2002, p. 170). However, “self-serving papalist accretions” were eradicated in Germany, leaving canon law to return “to its core interpretations and applications of biblical and natural norms” (ibid). This transformed German law, which still largely influences modern Western laws of education, social welfare, and marriage (Witte 2002, p. 295). Moreover, “the Ten Commandments provided the Evangelical jurists with a useful framework for organizing some of the legal institutions of the state” (Witte 2002, p. 170; see Table 5).

Successively, all Europe (and later also other regions) felt the repercussions of the Protestant revolt against the canon-law-based and hierarchical Roman Church–State. The sixteenth-century German Lutheran revolution of theology, law, and institutions took hold in various European countries. While it helped to establish “national legal systems, covering the entire spectrum of jurisdictions” (Berman 2003, p. 8), it elevated monarchies over the Roman Church–State (Berman 2003, pp. 72, 208). In fact, after the Lutheran Reformation,

the idea of the Pope and Emperor as parallel and universal powers disappears, and the independent jurisdictions of the sacerdotium are handed over to the secular authorities.(Skinner 1978, p. 353)

Consequently, the Lutheran Reformation extended across Europe. Even in the remaining Roman Catholic countries (e.g., Spain, France, or Austria), royal powers significantly increased over the Roman Church–State within the kingdoms (Berman 2003, p. 8).

7.3.2. The Seventeenth-Century English-European Revolution

Under the influence of the sixteenth-century German revolution, England also instituted a Protestant state–church to which all citizens had to belong, and both Church and citizens fell under the authority of the monarch. Later, dissenting Calvinists and other oppressed classes initiated the English or Glorious Revolution (1640–1689). This curbed the influence of the state–church and established the supremacy of Parliament over the Crown. Subsequently, the “English Revolution produced a body of law that reflected a Calvinist belief system” (Berman 2003, p. 10). This “reformation of the Reformation” fundamentally and lastingly transformed the English legal system, including checks and balances of political power. The English Revolution also became a European revolution and it succeeded the previous one in Germany (Berman 2003, p. 201).

Akin to the German Lutheran Reformation, the Ten Commandments serve as a basis for a plural system of law in England (Doe and Sandberg 2010). The general principle “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” (second part of the Decalogue that Jesus summarised in Matthew 22:37–39) is a touchstone of civil behaviour (p. 163) (Table 5).

The Protestant Reformation in England and Wales banned the teaching of canon law at universities (Doe and Sandberg 2010, p. 9). Equally, in the courts of Westminster Hall, invoking canon law was increasingly deplored (Helmoz 1987; Pearce 2010). Similar to Germany, not all canon law was eliminated as an authoritative source. In fact, some ordinances were adapted to ongoing developments in English common law.

The expansion of the British Empire resulted in a wide distribution of common law in the British colonies. Therefore, this law is still in force in Great Britain, Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 4).

7.3.3. The Eighteenth-Century United States Revolution

The successive Protestant Reformations involved progressive legal steps towards democracy, and thus increasingly distanced societies from the power of the Roman Church. Each dissenting Protestant revolution took the developments and achievements of the previous one as a basis. The sixteenth-century German-European Reformation had generally increased royal powers as a means of overthrowing the Roman Church–State. The seventeenth-century English-European Revolution made further advances by introducing checks and balances for monarchical powers and by limiting the power of the Church–States. Such developments paved the way for the world’s first-ever democratic constitution: the eighteenth century American Bill of Rights. In the United States, once again, a dissenting Protestant view that was based on the previous reformatory advances became dominant and denied the establishment of a State–Church.

Furthermore, the American constitution expanded the democratic rights and liberties of citizens (thus advancing English legislation, which had already guaranteed rights to the aristocracy over the monarchy) (Miller 2012; Berman 2003; Witte 2002).

The eighteenth-century French-European revolution also helped to nurture its counterpart in the United States. However, the latter implemented a different system of checks and balances in government powers than those that were proposed by the French Revolution, for instance (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007); (Berman 2003).

7.3.4. The Influence of Protestant Revolutions on Secularism

The influence of religion has largely been neglected or obscured in the mainstream literature, despite the critical impact of Protestant reformations on the law and on institutions (Doe and Sandberg 2010, p. 9; Berman 2003, p. 71; Witte 2002, p. 28; Anderson 2009, p. 210). However, the Protestant reformations initiated rapid secularisation. This process diminished the public role of the Roman Church–State and it dismantled imperial hierarchy (Philpott 2001; Snyder 2011). Moreover, these reformations and their associated progressive weakening of the Roman Church–State ultimately resulted in the modern sovereign state system in the seventeenth-century (i.e., the Peace of Westphalia in 1648) (Snyder 2011; Agnew 2010; Shah and Philpott 2011; Philpott 2001).

Much liberal Enlightenment thought was grounded in Protestant secularism (Snyder 2011, p. 17). Therefore, the laic rejection of Roman Catholicism in revolutionary France arose from the influence of Protestantism, in particular, Calvinism. Most Enlightenment theorists of democracy (e.g., Locke, Rousseau, Grotius, Franklin, Adams, Henry, Madison, and Hamilton) came from a Calvinist background, even if they were not religious (Woodberry 2012, p. 248). Enlightenment theorists secularised the ideas that were previously expressed by Calvinist jurists and theologians (e.g., Nonconformist and Puritan covenants formed the basis of the secular social contracts devised by Hobbes and Locke) (Hutson 1998; Lutz 1980; 1988; Nelson 2010; Witte 2007; as cited in Woodberry 2012, p. 248).

Locke’s principle of equality for all people derives explicitly from Protestant ideals (Waldron; Woodberry and Shah; as cited in Woodberry 2012, p. 248). Moreover, Protestant dissenters in Protestant liberal democracies spearheaded egalitarian movements, such as the abolition of slavery, free trade, and peace (Woodberry 2012; Snyder 2011; Kaufmann and Pape 1999). In this sense, the motto has been “no Reformation, no liberal peace” (Snyder 2011, p. 17). Consequently, Protestantism “served as the historically decisive prelude to secularization” (Berger 1990, p. 113). In its wake, religion has since lost much of its past influence (Norris and Inglehart 2004) in specific contexts (e.g., Europe and academia). The rest of the world, however, is as religious as ever. Some regions (e.g., the Middle East) are even more religious than before (Berger 1999).

7.3.5. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth-Century French-European Revolution.

The successive Protestant reformations inspired or initiated transformations from which secular, anti-clerical revolutions arose. These further decreased the power of the Roman Church–State and expanded civil power. The most notable revolution, the French Revolution, utterly suppressed the monarchy in France and extended to most papal states (e.g., Pope Pius VI was taken prisoner until his eventual death). Some of these states were later restored. The Italian nationalism and anti-clericalism that remained after the French Revolution resulted in the nineteenth-century annexation of Rome and the papal states to the former Italian Kingdom. However, it was not until 1929 that the current Vatican State was created through the Lateran Treaty with Mussolini’s National Fascist Party (Gross 2004; Hanlon 2008; Roessler and Miklos 2003).

Rousseau’s Social Contract (1762) and the French Revolution (1789) openly identified Roman Catholicism (and Christianity in general), as opposed to any free republic. In such a Manichean conflict between the Church and the Republican state, the Republic ended up radically subordinating the Church. Consequently, the French Republic eliminated the Church’s control over education, its ownership of large estates, and its right to perform marriage ceremonies (Shah and Philpott 2011, p. 38).

Not only the new French legal philosophy of rationalism, individualism, and utilitarianism, but also the rejection of orthodox Christian doctrines, were associated with deism (i.e., the belief in a Creator’s gift of reason and freewill in exercising that gift (Berman 2003, p. 10).

French rationalist natural secular jurists considered it possible to abolish the old (i.e., Roman-canonical) legal system altogether and to create an entirely new one. However, the jurists that drafted the new system were trained in the old one, of which a significant part was preserved as a result (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015).

Eighteenth and nineteenth-century revolutions (i.e., the French and American revolutions, the Italian Risorgimento and Latin American independence wars) gave rise to administrative and constitutional law under civil law. The French Revolution also bringing forth “secular natural law” (based on deism) was equally important. Montesquieu and Rousseau promoted the importance of separating government powers (judicial, executive, and legislative), as initiated by the French Revolution. After the nineteenth century, the authority of Roman (and canonical) laws gradually declined. The Revolution meant that nationalist ideologies replaced religious ideologies. Feudal institutions were incompatible with such developments (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015).

The French imposed civil codes, abolished guilds, and feudal remnants, and they undermined aristocratic privileges, thus boosting prosperity in the territories that they conquered in Europe (Acemoglu et al. 2011). Consequently, the principal states of Western Europe adopted civil codes, whose archetype is the French Code Napoléon of 1804 (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 10).

A particularly explosive revolutionary development occurred in education. French republicans and liberals repeatedly pushed for a state-supervised, compulsory, educational system. In Belgium, the Liberal Party implemented a programme in the 1870s to significantly restrict the role of the Roman Catholic Church in education (Shah and Philpott 2011, pp. 39–40).

However, even after an age determined by reason and revolution, feudalism survived in Latin America and in certain parts of Europe (especially in southern countries). Feudalism has kept alive the social injustices inherent in its origins. This is understandable because when “the French exported their system, they did not include the information that it really does not work that way and failed to include the blueprint of how it actually does work” (Merryman 1996, p. 116).

For example, the laïcité, or separation of Church and State rooted in the French Revolution, was not automatically transplanted to Latin America. Thus, Colombia did not separate Church and State in its Constitution until 1991. In contrast, feudal legal institutions in the British colonies of North America were already deprived of their pernicious socio-economic influence early on (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015).

7.3.6. Maintaining the Roman Catholic Medieval Status Quo in Latin American Countries Post-Independence

By the onset of the colonial period, the Iberian Peninsula, which was closely associated with the Roman Church, had established its hegemony in Europe. This enabled Spain and Portugal to bring the richest territories in gold and jewels in the Americas under their rule (South and Central).

The Roman Catholic Church–State legitimated Latin American territories as either Spanish or Portuguese colonies from the fifteenth to the early nineteenth centuries. Equally, Spanish and Portuguese settlement guaranteed a Catholic monopoly from 1500 to the early 1900s, thus securing the Church’s hegemony and a feudalist economy (Gill 2013, p. 117). In essence, the conquest was a religious, political, and military endeavour that was actively supported by the Church. It made Latin America a unique cultural entity in the world, one largely possessing the same language (Spanish or Portuguese) and the same religion (Roman Catholicism) as robust, unifying elements (Navarro 2016, p. 111).

The conquerors exploited the indigenous population and established extractive institutions (servitude systems). La mita (“tax or common service paid by Indians”) and la encomienda (“enslavement or Spanish labour system”) were among the most common. These institutions were designed to extract wealth from the people and to perpetuate the power of a ruling elite during the colonial period. This situation persisted, even after independence in Latin American countries, whose present-day institutions descend from la mita or la encomienda. Such social inequality has bred corruption, violence, and political instability (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012).

Even after independence, the Catholic Church–State has been instrumental in securing a population loyal to government, thus perpetuating the status quo, i.e., the hegemony of the Church–State. Protestantism was officially banned, as were Bible distribution and Protestant services in Spanish, among other measures (Gill 2013, p. 119). In the mid-twentieth century, the Catholic Church continued to secure favourable institutional positions for itself in countries, such as Colombia or Argentina (Gill 2013; Munevar 2008; Gill 1998; Levine 1981).

The material and symbolic influence of the Roman Catholic Church has reinforced social arrangements in Latin America, ever since colonisation (Levine 1981, p. 29). The pervasive fusion of Roman Catholicism and politics in Latin America assumes several forms:

it may be expressed in the form and content of law; in the structures of education; in the nature of approved sanctions and mechanisms for resolving social conflict; and, of course, in the accepted processes for legitimating authority. All these manifestations and others are expressions of a belief that the values which orient individuals and inform the structure of institutions cannot be separated from those which relate individuals to the transcendental or divine.(Levine 1981, p. 20)

Protestant missionaries were able to slowly introduce Reformed forms of faith until ignoring Protestantism in Latin America became impossible in the twentieth century, notwithstanding the imposed restrictions (Gill 2013). Protestant missionaries provided the poor with access to literacy, medical assistance, and other services (Gill 2013; Gill 1998; Woodberry 2012). Growing Protestant competition forced many Catholic dignitaries to rethink their strategy with a new “preferential option for the poor” (Gill 2013; Gill 1998; Anderson 2007; Manuel et al. 2006). The Catholic Church promulgated a new social strategy (i.e., Rerum Novarum of 1891; Catholic Action; Second Vatican Council of 1965; Medellin Episcopal Conference of 1968). These developments also gave rise to “Liberation Theology” (Büschges 2018). Regardless of such advances, the Roman Catholic Church still exercises great hegemony in most Latin American countries, while traditional intransigent paradigms remain prevalent (Figueroa 2016; Munevar 2008; Martin 1999; Levine 1981).

The inertia of such institutional legacies and the prevalence of corporatist ideologies (pre-Vatican II) have perpetuated an elitist model of society in Latin America, which remains, by far, the most unequal continent in the world (World Bank 2014).

The Adoption of French Civil Law in Post-Independent Latin American Countries

Most Latin American countries bypassed the (Protestant) European revolutionary processes and directly adopted the French Revolution’s legal tradition (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015; La Porta et al. 2008). Thus, the French legal tradition profoundly influenced all former Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America. The exception to this rule is Cuba, which adopted the socialist legal tradition in the 1960s. Some former British colonies in the Caribbean also have English common law (La Porta et al. 2008).

The influence of the Protestant Reformation on the law and on institutions in Latin America has been minimal or indirect, and has resulted from the US–American influence, for instance (i.e., constitutionalism) (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015). More importantly, the pervasive influence of the Roman Catholic Church–State meant that Latin American countries adopted the legal tradition of the French Revolution without, however, embracing anti-clerical movements (or with fragile anti-clerical components) (Salinas Araneda 2013; La Porta et al. 2008). The exceptions include Uruguay, Chile, and Cuba, as these countries have had successful anti-clerical or laic movements and because their legal systems have long reflected a clear separation of Church and State. Moreover, these countries have never signed a concordat with the Roman Church–State (Da Costa 2009; Salinas Araneda 2013; Ramírez 2009).

Concordats with the Roman Catholic Church–State

Concordats are international treaties between the Roman See (the so-called “Holy See”) and individual countries. Such agreements have been criticised as mutual concessions of privileges between Church and State. The three most important and controversial concordats that were signed by the Catholic Church in the twentieth century were with the Nazi Reich in Germany, with Franco in Spain, and with Fascist Italy (Fumagalli 2011, pp. 438–39).

Eleven Latin-American countries have in force a concordat with the Roman Catholic Church–State (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Republic, and Venezuela). Such states are called “concordatarian”. The extent to which such agreements grant privileges to the Roman Church varies from country to country. The other Latin American countries maintain fewer diplomatic relations with the Vatican (some less, some more), for instance, through formal agreements or the exchange of letters (Corral 2014). Concordats may cover diverse affairs, from tax exemptions for the Roman Church to permitting its intervention in military, educational, and property matters (Corral and Petschen 2004; Forrest et al. 2006; Brownlie 1979; Levine 1981; Figueroa 2016).

Pope Pio IX introduced the template that is used by the Vatican in most concordats with Latin American countries (1846–1878) (Salinas Araneda 2013). It accords extraordinarily extensive rights to the Catholic Church–State, for instance, in educational affairs:

Education in universities, public and private schools and further educational establishments should be under the doctrine of the Catholic Religion. […] the bishops and other local ordinaries would have the free direction of the theology chairs, of canon law, [and] of all the branches of ecclesiastical teaching. […] in addition to the influence they will exert through the strength of their ministry over the religious education of youth, they will ensure that in the teaching of any other branch there is nothing contrary to [the Roman Catholic] religion and morality (article 2). Besides, the bishops retain their right of censure over all books and writings related to dogma and discipline of the Church and public morals.(model of the Bolivian concordat, cited in Salinas Araneda 2013, p. 217; my translation of the original Spanish document)

Latin American concordats are all similar (or in many cases even identical). Their wording attests to the Vatican’s influence rather than that of the countries (Salinas Araneda 2013).

As a rule, concordats ensure religious education in public schools. The conference of bishops, in agreement with the responsible government authorities, approves the curriculum for the teaching of Roman Catholic religion in schools (Schanda 2004). Further, they imply state recognition of the sovereignty of the Roman Catholic Church–State. Consequently, Roman Catholicism is the only religion to possess legal personality under international public law. The other religious denominations are only entitled to enter into agreements under domestic public law, as they possess no international legal personality. This privilege of the Roman Catholic Church–State has sometimes been used to the detriment of other religious denominations (Fumagalli 2011, p. 444).

Therefore, European Union (EU) institutions, such as the European Court of Human Rights, have indirectly challenged Roman Catholic concordats for introducing legislation that is not aligned with international standards into domestic law (Fumagalli 2011, pp. 445–46). In Europe, at least two objections have been leveled at concordats (i.e., treaties and bilateral relations with the Roman Church–State): first, they limit the sovereignty of the state; second, they promote the denominational inequality that arises from the privileges of the Roman Catholic Church–State (Schanda 2004; Cook 2012).

7.3.7. The Twentieth-Century Russian Revolution

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Eastern Orthodox Russia opposed both the papal Roman Church–State and canon law and established its own hierarchy and canon law. However, Russia maintained its tsarish autocracy and its supreme secular and spiritual authority until 1917. The successive Lutheran, Calvinist, dissenting Protestant and deist revolutions all bypassed Russia. Thus, Russia never experienced an evolutionary process from an autocracy to a monarchical high magistracy, to an aristocratic Parliament, and then to a democratic separation of powers. Instead, it underwent abrupt transformation through the Bolshevik revolution, which was inspired, in part, by the eighteenth-century French Enlightenment, and later proclaimed atheism. Moreover, the Russian Revolution led to a totalitarian state that distorted the ideals of social democracy (Berman 2003, p. 18); (Miller 2012).

One of the ideal postulates of the atheistic foundations of Soviet law is the “goodness of humankind”. This involves the acceptance of an inherent human nature, which is capable of establishing a fair and just society (Berman 2003, p. 18). Such a postulate opposes the biblical principle that forms the basis of the Protestant Revolutions: “nothing good can be found in humankind” (see Section 7.3.1 and Table 5). The atheist, Soviet legal principle of the “goodness of humankind” resembles Roman Catholic natural law, in that it trusts the human capacity to discern good from evil (Selling 2018, p. 9; Gula 2002, pp. 120–21). In fact, socialist legal traditions only ever emerged in countries with an Orthodox or Roman Catholic background, but never in countries under Protestant influence. Thus, Andreski (as cited in Grier 1997) has argued that “Protestantism, by promoting prosperity [and equality], prevents the emergence of a social environment propitious to the spread of ideologies preaching violent subversion” (p. 49).

Significant differences exist between the Soviet, Western European, and American legal systems. Contrary to other systems, the Soviet one includes the dictatorship of the Communist Party and the absence of a law that is superior to that of the state. Other distinctive features are the repression of basic civil liberties (e.g., the freedom of religion, speech, and press) and the absence of private land ownership (Berman 2003, p. 19). However, the Russian Revolution’s elevation of the law’s parental role, and of the state’s social and economic role, has had repercussions throughout the world (ibid.). Interestingly, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, most former Soviet countries reinstated the legal tradition of the French Revolution (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015); (La Porta et al. 2008).

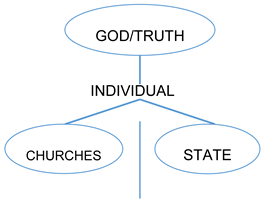

7.4. Religion, Law, and State Models in Europe and the Americas

Significant differences exist between the legal systems (and thus, between the models of the state) in Europe and the Americas. Table 6 summarises the various legal revolutions and traditions, along with their models of state–church-citizen relationships.

Table 6.

Moral and religious beliefs and models of state–church-citizen relations in the legal systems of Europe and the Americas (adapted from Witte 2002; Berman 2003; Miller 2012; Cook 2012; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007).

National legal systems have persisted for decades, or even centuries, while legal traditions have prevailed for centuries or even millennia. In contrast, political discourses may merely last a few years or decades. Therefore, the influence of different legal traditions tends to cluster countries into groups exhibiting affinities between their legal origins and institutional performance.

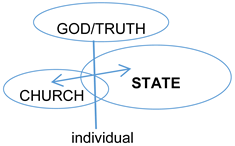

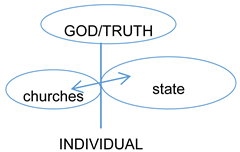

The various Church–State-citizen relationships (Table 6) delineate the historical progression from the original, medieval model of the Corpus Christianum, which entirely rested on Roman and Catholic canon law traditions (Model 1), to the modern legal systems.

1. The Corpus Christianum is the model of the medieval Pan-European Roman Catholic Church–State. In it, the Roman Church–State is the highest power. As such, it alone may access and interpret the divine and guide its small secular arm: the state. In this conception, both Church and State control and coerce the individual. The individual may solely access the divine through the Church, yet never directly. The entire system of moral and legal codes emanates from the Roman Catholic Church–State in the figure of the pope. Legally, the model currently applies to the Roman Church–State; minor changes were made after the Second Vatican Council (Cook 2012; Agnew 2010).

2. The second model (German Revolution) enhances the power of secular authorities (monarchical states), and thereby substantially reduces the influence of the Church. The State provides universal education. The individual is granted direct access to the Scriptures and enjoys direct communion with God (Berman 2003; Witte 2002; Becker and Woessmann 2009).

3. In the third model (English Revolution), oppressed groups and other dissenting forms of Protestantism (e.g., Calvinism, Puritanism) diminished the power of the state–church and thus of the monarchy. This process urged towards the separation of Church and State and sought to empower the individual. This large-scale development towards modern democracy was based on the advances of the Lutheran Reformation in Germany and northern Europe (Berman 2003); (Doe and Sandberg 2010).

4. The fourth model (United States Revolution) further progressed the clear separation of Church and State through a Protestant, dissenting process that was initiated earlier in England (and even before). The resulting democratisation progressively and continuously further empowered the individual (Berman 2003); (Miller 2012).

5. The fifth model (French Revolution) almost coincided with the fourth (these models cross-fertilised each other). However, Protestantism played no direct (or rather a merely indirect) role in France, unlike the previous revolutions. Liberal anti-clericalism fiercely opposed Roman Catholicism and it was also hostile to Protestantism (e.g., it destroyed bibles, ironically as Roman Catholicism did). Therefore, the French Revolution encouraged individual, relative truths (instead of Catholic dogmas or Protestant biblical, moral foundations) by promoting deism and reason. In this conception, the individual and the democratic state are also strengthened, as in the model of the United States Revolution. However, here, the state coerces and controls the churches (Berman 2003; Miller 2012; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007).

6. The sixth model (the Russian Revolution) goes beyond the principles of the French Revolution. The state becomes the most powerful entity and it hopes to liberate individuals from religious, “opiate-like” beliefs and from economic, class-based exploitation. Consequently, the state significantly coerces religion and enhances both the law’s parental role and the state’s social and economic role (Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007).

7.5. A Synthesis of the Institutional Role of Religion in Law, State, and Prosperity

The influence of the various legal traditions has long persisted, even if most revolutions were defeated. For instance, Eastern schism and, in particular, the German, English, American, and French revolutions terminated the hegemonic monopoly of Roman canon law. The Thirty Year War ended the German Revolution, the English Revolution suffered defeat in the early 1800s, the French Revolution in 1870, and the Russian Revolution in the 1990s (Berman 2003).

Yet, all of these revolutions influenced the different legal traditions. Several elements of those revolutions still coexist in some countries more than in others. Roman and canon law percolated into the legal systems of those countries that underwent revolutions to a greater or lesser degree. For instance, the French and German revolutions made the jurists re-adopt and adapt the principles of the old regime in order to build on the respective basis (Witte 2002; Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007). However, Roman and canon law exercised less influence in common law countries (e.g., after the English and United States revolutions) (Doe and Sandberg 2010; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007; Berman 2003).

The Lutheran German Revolution formed the basis of the various later Protestant, dissenting revolutions and legal traditions (i.e., British and American). Some of its concepts (e.g., the separation of state functions from the Church; state-sponsored education) permeate all modern legal systems to this day (Witte 2002; Berman 2003). The English Revolution marked a crucial step towards modern democracy and it limited the power of the monarchies in Europe. Moreover, the British Empire spread common law throughout its colonies across the world (Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007; La Porta et al. 2008).

The revolution in the United States inspired modern constitutionalism and democratic rights across the world. The French Revolution transferred its legal model to its colonies and countries under its influence. Thus, the United States exerted constitutional influence on Latin American countries, while the French Revolution inspired the independence and the creation of the modern Latin American republics. However, the anti-clericalism of those revolutions was not always assimilated. Instead, with the French code, the Roman and Catholic canonical has remained the predominant legal tradition in most Latin American countries to this day, which attests to the pervasive presence (and power) of Roman Catholicism (i.e., concordats, corporatist states, and Catholicism as a state religion) (Berman 2003; Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007; La Porta et al. 2008; Barro and McCleary 2005; Salinas Araneda 2013).

Thus, the basic model of Church–State-citizen relations in most Latin American countries more closely resembles the medieval Corpus Christianum, i.e., a model that is based on Roman and Catholic canon law traditions (Model 1). This happened although Latin American countries adopted several elements from the French legal tradition. Examples of corporatist states in which concordats are effective include Colombia, Venezuela, and Honduras.

On the other hand, Chile and Uruguay are liberal democracies with explicit anti-clerical movements that never allowed concordats to be signed with the Roman Church–State. Consequently, their basic model of Church–State-citizen relations more closely resembles that of the French Revolution (Model 5). After its revolution, Cuba adopted the Russian model (Model 6).

In Europe, Switzerland (following the 1848 Constitution) was influenced by dissenting Protestantism and by United States (US) federalism and constitutionalism, along with French liberalism (Obinger 2009). The Swiss Confederation has never signed a concordat with the Roman Church–State, even if agreements exist at the cantonal level.

The anti-clerical, anti-Roman, and anti-canon law sentiments that influenced sixteenth-century Lutheran Germany resembled those of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century post-revolutionary France. Jurists sought to eliminate the references to Roman and canonical law in both cases. Therefore, Germany and France represent the most atypical legal systems in the “world of civil law”. Their models have assumed intellectual leadership and they have been implemented in several other countries (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015).

Nonetheless, in both instances, the jurists ended up readapting and reincorporating Roman and canon law to suit their new purposes (e.g., the adoption of biblical principles in Lutheranism and of rationalist deism in the French Revolution) (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015; Witte 2002). Consequently, the Roman influence is still highly significant in both cases, notwithstanding the substantial legal contributions of the respective revolutions (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007, p. 13).

Common law is a different case, because British jurists managed to adapt a legal system after the Reformation that was barely influenced by either Roman or canon law (Doe and Sandberg 2010). Thus, common law has no hierarchical source of law. It is less rigid, less rigorous, and less systematic than civil law. Likewise, common law jurisprudence is less influenced by the rationalist dogmas of the French Revolution (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2015).

Legal origins that are associated with Protestant influence (e.g., English common law, German and Scandinavian legal systems) have proven to be more sustainable. They also exhibit higher institutional performance and prosperity than legal origins that are associated with a laic rejection of religion (La Porta et al. 2008). Here, dissenting Protestant religions were the precursors, not only of the Enlightenment, but also of widespread social emancipation (Snyder 2011; Woodberry 2012; Miller 2012).

In contrast, legal origins that are associated with a laic rejection of religion have not proven sustainable over time (e.g., the Soviet tradition) or the elements crucial to their functioning could not be transferred (e.g., French Revolution). For instance, while French legal origins conveyed anti-clerical sentiments to Southern European countries, they were not automatically transferred to most Latin American countries (Merryman and Pérez-Perdomo 2007). As a result, Southern European countries materialised the sovereignty of their states over the Roman Church–State, and thereby attained certain levels of prosperity and institutional performance (higher than in most Latin American countries, but lower than in historically Protestant countries).