The Lion and the Wisdom—The Multiple Meanings of the Lion as One of the Keys for Deciphering Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion

Abstract

:1. Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion

2. Provenance and Literature Review

3. Symbolic Animals in Ancient and Medieval Literature

4. The Conception of Job as a Prophet

Take, my brethren, the prophets, who have spoken in the name of the Lord, for an example of suffering affliction, and of patience. Behold, we count them happy which endure. Ye have heard of the patience of Job, and have seen the end of the Lord; that the Lord is very pitiful, and of tender mercy.50

What can be clearer than this prophecy? No one since the days of Christ speaks so openly concerning the resurrection as he did before Christ. He wishes his words to last for ever; and that they might never be obliterated by age, he would have them inscribed on a sheet of lead, and graven on the rock. He hopes for a resurrection; nay, rather he knew and saw that Christ, his Redeemer, was alive, and at the last day would rise again from the earth.53

5. The Lion in Carpaccio’s Meditation

Thus our Lord, falling asleep in death, physically, on the cross, was buried, yet his divine nature remained awake; as it says in the Song of Songs: ‘I sleep but my heart waketh’ (5:2); and in the Psalm: ‘Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep’ (121: 4).63

6. The Conception of Wisdom in the Book of Job

While they thought only of the things they could see, they were unable to perceive in the Lord the things they could not see; for whilst they contemn the flesh that was to be seen, they never reached to the unseen Majesty.67

7. The Throne, the Wisdom, and the Venetian Self-Image

8. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Source

Aberdeen Bestiary (ca. 1200), Aberdeen Bestiary Projectweb site, translation and transcription Morton Gauld, Colin McLaren & Aberdeen University Library, 1995 http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/what.hti.Franciscus de Retza (German, ca. 1343–1427), Defensorum inviolatae virginitatis Mariae, Basel, 1490.Guillaume le Clerc (William le clerc of Normandy, French, fl. 1210/1211–1227/1238), The Bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc), Ashford, 1936.Isidore of Seville (Spanish, A.D. 560–636), Etymologiarum sive originum Libri XX, ed. E. M. Lindsay, Oxford, 1911, http://bestiary.ca/beasts.Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa (Italian, 1228–1298), The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints, 1275. First Edition 1470. English trans. by William Caxton, 1483. Edited by F.S. Ellis, Edinburgh, 1900 (Reprinted 1922, 1931), Vol. 5, 94ff, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/GoldenLegend-Volume5.asp#Jerome.St. Gregory the Great (Italian, ca. 540–604), Moralia in Job, Oxford, John Henry Parker; J.G.F. AND J. Rivington, London, 1844 (http://www.lectionarycentral.com/GregoryMoraliaIndex.html).St. Jerome (Roman, ca. 347–420), Letters, Translated by W.H. Fremantle, G. Lewis and W.G. Martley. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, Vol. 6. Edited by Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1893.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. Also in http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001.htm.St. Jerome, Contra Joannem Hierosolytitanum, in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 1995, pp. 439–40, http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0347-0420,_Hieronymus,_Contra_Joannem_Hierosolytitanum_Ad_Pammachium_Liber_Unus_[Schaff],_EN.pdf.Secondary Sources

- Balentine, Samuel E. 1999. “Who Will Be Job’s Redeemer?”. Perspectives in Religious Studies 26: 269–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bätschmann, Oskar. 2008. Giovanni Bellini. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, Ron. 1988. Bestiaries and their Users in the Middle Ages. Stroud: Sutton Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Blass-Simmen, Brigit. 2006. Studi dal vivo e dal non più vivo: Carpaccio’s Passion painting with Saint Job. Metropolitan Museum Journal 41: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroughs, Byron. 1911. The Meditation on the Passion of Carpaccio. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 6: 191–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau-Lassay, Louis. 1940. The Bestiary of Christ. New York: Parabola Book. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Simona. 2008. Animals as Disguised Symbols in Renaissance Art. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Coltellacci, Stefano, and Marco Lattanzi. 1981. Studi Belliniani: Proposte Iconilogiche per la Sacra Allegoria degli Uffizi. In Giorgione e la Cultura Venetatra ‘400 e ’500: Mito, Allegoria, Analisi Iconologica. Edited by A. Gentili and C. Ceri Via. De Luca: Roma, pp. 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Emison, Patricia. 1995. The Paysage Moralise. Artibus et historiae 16: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, Herbert. 1980. A Bestiary for St. Jerome: Animal Symbolism in European Religious Art. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffen, Rona. 1986a. Piety and Patronage in Renaissance Venice: Bellini, Titian and the Franciscans. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffen, Rona. 1986b. Bellini, S. Giobbe and Altar Egos. Artibus et Historiae 7: 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffen, Rona. 1989. Giovanni Bellini. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartt, Frederick. 1940. Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion of Christ. Art Bulletin 22: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassig, Debra. 1995. Medieval Bestiaries: Text, Image, Ideology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, T.J. 1975. An Analysis of the Narrative Motifs in the Legend of St. Eustace. In Medievalia et Humanistica. New Series 6; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, Heidi J. 2002. The Venetian images by Bellini and Carpaccio: Job as intercessor or prophet? Review & Expositor 99: 541–68. [Google Scholar]

- Levi D’Ancona, Mirella. 2001. Lo Zoo del Rinascimento: il significato degli animali nella pittura italiana dal 14 al 16 secolo. Lucca: M. Pacini Fazzi. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Kenneth. 1905. Unpublished Manuscripts of Italian Bestiaries. Publications of the Modern Language Association 20: 380–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Kathi. 1954. St. Job as a Patron of Music. Art Bulletin 36: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovich, Atara. 2015. Giobbe il Povero: A Social Reading of Giovanni Bellini’s Sacred Allegory. Global Humanities 2: 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pease, Murray. 1945. New Light on an Old Signature. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 4: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Claude. 1911. An Unrecognized Carpaccio. Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 19: 144–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, Terisio. 1965. Carpaccio: La Leggenda di Sant’Orsola. Firenze: Sadea/Sansoni Editori. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus, Debra. 2010. Venice and its Doge in the Grand Design—Andrea Dandolo and the Fourteenth-Century Mosaics of the Baptistery. In San Marco, Byzantium and the Myths of Venice. Edited by Henry Maguire and Robert S. Nelson. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, pp. 245–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pullan, Brian. 1971. Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Eugene F., Jr. 1985. Saint Jerome in the Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, Joan Olivia. 1979. Hodegetria and Venetia Virgo: Giovanni Bellini’s San Giobbe Altarpiece. Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rosand, David. 1976. Titian’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple and the Scuola della Carità. Art Bulletin 58: 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosand, David. 2001. The Myths of Venice: The Figuration of a State. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt Arcangeli, Catarina. 1998. La Sapienza nel Silenzio Riconsiderano la Altarpiece di San Giobbe. Saggi e Memorie di Storia dell’Arte 22: 11–54. [Google Scholar]

- Smalley, Beryl. 1964. The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sobol, Peter G. 1993. Review of Wilma George and Brunsdon Yapp, The Naming of the Beasts: Natural History in the Medieval Bestiary. Journal of the History of Biology 26: 160–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenti, Alberto. 1973. The Sense of Space and Time in the Venetian World of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. In Renaissance Venice. Edited by John Rigby Hale. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Terrien, Samuel. 1996. The Iconography of Job Through the Centuries: Artists as Biblical Interpreters. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verdier, Philippe. 1952–1953. L’allegoria della Misericordia e della Giustizia di Giambellino agli Uffizi. Atti dell’Instituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere e Arti CXI: 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Joseph A.P. 2009. The Life of the Saint and the Animal: Asian Religious Influence in the Medieval Christian West. Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature & Culture 3: 169–94. [Google Scholar]

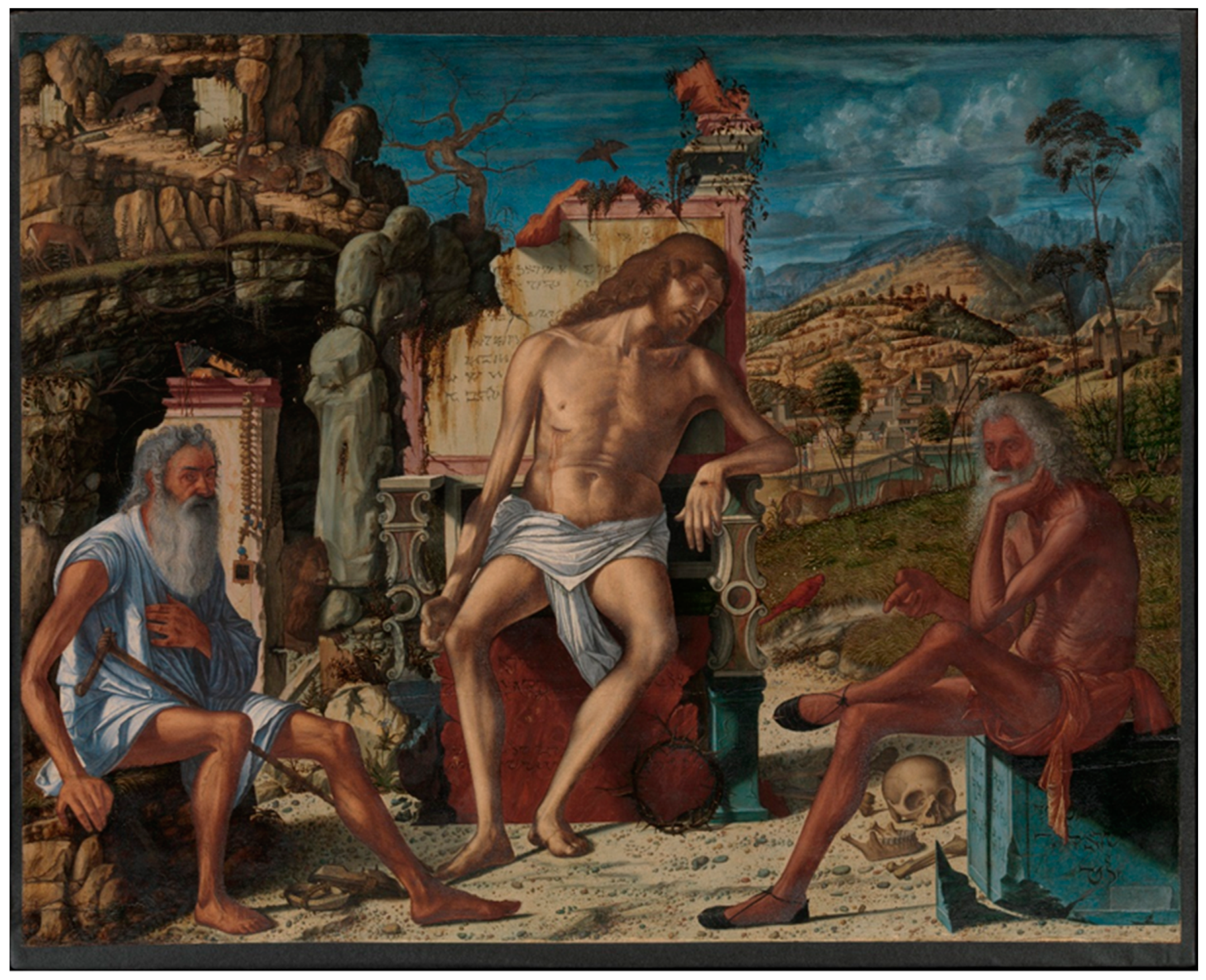

| 1 | Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, ca. 1464–1525/6), Meditation on the Passion, ca. 1490–1510, oil and tempera on wood, 273/4 × 341/8 in. (70.5 × 86.7 cm), New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 2 | On the Christian hermeneutical tradition of ascribing multiple meaning to Biblical figures and verses, see Smalley 1964. |

| 3 | For a short review of the multiple meanings of the figure of Job, see Moscovich 2015, pp. 134–35. |

| 4 | Hornik 2002. The other works of art featuring the figure of Job include Giovanni Bellini’s (Italian, 1435–1518) San Giobbe Altarpiece, Ca. 1445–1487, Oil on Wood, 15 ft. 5⅜ in. × 8 ft. 6 in. (471 × 258 cm), Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia. Giovanni Bellini’s The Sacred Allegory, ca. 1490–1510, oil and tempera on wood, 29 × 47 in. (78 × 119 cm), Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi. Vittore Carpaccio’s Dead Christ, 57 × 72¾ in. (145 × 185 cm), tempera on wood, ca. 1510–1520, Berlin, Staatliche Museum, Gemäldegalerie. To this list, addressed by Hornik, one should also add St. Job and St. Francis, a marble relief above the Church of San Giobbe by Pietro Lombardo (Italian, 1435–1515), and Marcello Fogolino’s (Italian, 1470/1488?–1548) Madonna and Child between Saints Job and Gothard), 79⅞ × 63 in. (203 × 160 cm), oil on wood, ca. 1508, Milan, Pinacoteca Brera. |

| 5 | It might be that one of them (Giovanni Bellini, Pietà, 1460–1465, canvas, 45¼ in. × 10 ft. 3/4 in. [115 × 317 cm], Venice, Doge Palace), a rare composition featuring Christ and two saints, was a precedent to Carpaccio’s Meditation. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Phillips 1911, p. 145; Borroughs 1911, p. 183; for the sources of the legends relating St. Jerome with the lion, see Jacobus de Voragine, vol. 5, pp. 203–5; Friedmann 1980, pp. 19–22, 231–49; Rice 1985, pp. 37–45, 157–58. |

| 8 | St. Jerome, Letters, 22:3, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001.htm; the connection between this letter and this tradition was identified by Friedmann 1980. |

| 9 | Friedmann, ibid., p. 65; see also Rice 1985, pp. 75–76. |

| 10 | Saint Jerome, Letters, 22:3. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | For the scuole and their important part in the Venetian society, see Pullan 1971; for the specific significance of the scuole for interpretation of artworks featuring the figure of Job—see Moscovich 2015, p. 137 ff. |

| 13 | For details of Dead Christ, see endnote No. 3 above. |

| 14 | See below, in the Literature Review section. |

| 15 | Phillips 1911, p. 144; Borroughs 1911; The Metropolitan Museum of Art website, http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/110000284. |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | Saint Gregory the Great, Moralia in Iob, (http://www.lectionarycentral.com/GregoryMoraliaIndex.html); Hartt 1940, pp. 28, 29. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | Friedmann 1980, p. 49; on enhancing the message by repeating symbols that have a similar meaning, see Baxter 1988, pp. 27, 72, 78. |

| 28 | Job, 16:9–14; 10:16; Hornik 2002, p. 554. |

| 29 | Job, 29:17. |

| 30 | |

| 31 | |

| 32 | Blass-Simmen, ibid., 87. |

| 33 | |

| 34 | For the persistence of this literature during the Renaissance, see Cohen, ibid., passim, esp. Introduction; for the connection with Carpaccio’s oeuvre, see Cohen 53–134. |

| 35 | |

| 36 | |

| 37 | Several manuscripts written in Italian, most of them in the Tuscan dialect, were studied over a hundred years ago, see Kenneth McKenzie 1905, 380–433. However, one of these manuscripts, written in the Venetian dialect (probably od. C.R.M.248 [C, G, K], was found in the Museo Civico di Padova [Bibl. Comun.]. McKenzie does not provide enough information on this point. Yet, the provenance of the manuscript written in the Venetian dialect, is probably Venice, and perhaps was in Venice when Carpaccio’s Meditation was painted. Also see Cohen 2008, p. 6; Hassig 1995. A list of bestiaries can also be found on the online catalogue of bestiaries, http://www.bestiary.ca/articles/family/mf_other.htm.) |

| 38 | |

| 39 | (Early Greek copies of the book did not survive, and the earliest texts known to us today are Latin translations from the eight-century A.D. The book was also translated into several Mediterranean languages. See Cohen 2008, p. 4. Baxter, xiii, 29; Aberdeen Bestiary; Hassig 1995, pp. xvi, 5; Sobol 1993, 160–62. The additional sources added during the ages to the text of the Physiologus in the Bestiaries are listed in Hassig 1995, pp. 5–8; see also Cohen 2008, p. 5.) |

| 40 | From Aberdeen University website, http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/what.hti; Sobol (1993) maintains that the book was written in the first or second century A.D. |

| 41 | |

| 42 | Baxter, ibid., p. 72. |

| 43 | Baxter, ibid., pp. 27, 72. |

| 44 | Baxter, ibid., p. 78. |

| 45 | Cohen 2008, p. 5; Baxter, ibid., pp. 192–93, 209, 212. |

| 46 | However, he also found texts written at a later date, and adapted for private reading, see Baxter, ibid., pp. 202–5. |

| 47 | Baxter, ibid., pp. 72, 82. |

| 48 | Baxter, ibid., esp. pp. 37–62. |

| 49 | Baxter, ibid., pp. 156–61, 179–81. Bestiaries that were not owned by monasteries, monks or clergy were very rare, see Baxter, ibid., p. 199. |

| 50 | James, 5:10–11. |

| 51 | Job, 19:25. |

| 52 | |

| 53 | St. Jerome, Contra Joannem Hierosolytitanum, in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, pp. 439–40, http://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0347-0420,_Hieronymus,_Contra_Joannem_Hierosolytitanum_Ad_Pammachium_Liber_Unus_[Schaff],_EN.pdf. |

| 54 | St. Gregory the Great, Moralia, II: XX, xl, 77. |

| 55 | Job, 19: 23–24. |

| 56 | Jacobus de Voragine, vol. 5, pp. 203–5; Friedmann 1980, pp. 19–22, 231–49; Rice 1985, pp. 37–45, 157–58; Levi D’Ancona 2001, pp. 149–50. |

| 57 | Isidore of Seville, 12:2:3–6, http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast78.htm; Levi D’Ancona, ibid., p. 149. |

| 58 | Guillaume le Clerc http://bestiary.ca/beasts/beast78.htm. |

| 59 | Aberdeen Bestiary, Fol.7v, http://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/translat/7v.hti; Hassig, 50, 162, 256; Also see the list of the Christian authors who repeated the legend in Charbonneau-Lassay 1940, p. 11. |

| 60 | Franciscus de Retza, Defensorum, https://archive.thulb.uni-jena.de/ufb/rsc/viewer/ufb_derivate_00002796/Xyl-00008_012r.tif; Also quoted in Levi D’Ancona 2001, p. 149. |

| 61 | Levi D’Ancona (ibid., p. 148) quotes Fillippo Picinelli, Mundus Symbolicus, which is a late source, from the seventeenth century, but it is quite possible that this interpretation existed at an earlier date. |

| 62 | Job, 19:25. |

| 63 | Aberdeen Bestiary, Fol.7v, https://www.abdn.ac.uk/bestiary/ms24/f7v. |

| 64 | Job, 28:12; 28:20. |

| 65 | Job, 28:28. |

| 66 | Job, 19:15. |

| 67 | St. Gregory the Great, Moralia, Vol. II, Book XIV, xli, 49. |

| 68 | Voragine, vol. 6, pp. 83–94; for other versions and sources—see Heffernan 1975. However, since Voragine’s Golden Legend was translated into Italian by Nicolò Malerbi and published in Venice by Nicholas Jenson in 1475 (see Pignatti 1965), therefore it was, most probably, the source used by Carpaccio. Heffernan (p. 67) also mentions that St. Eustace first appears in the pseudo-Jerome Martyrology. It might worth further research, whether this text might have been known—and still attributed to Jerome—in Carpaccio’s milieu, which would form another connection with St. Jerome, and thus with the Mediation as well. |

| 69 | On the narrative parallels and linguistic similarities between the Life of St. Eustace and the Book of Job, see Heffernan, ibid, pp. 72–73. |

| 70 | The artworks commissioned specifically for San Giobbe are Lombardo’s relief and Bellini’s San Giobbe Altarpiece, both featuring St. Francis and Job. For an interpretation of the legend of St. Eustace as reflecting human compassion to all living creatures, due to its Buddhist sources, and for Buddhist influence on Franciscan reverence to all forms of life, see Wilson 2009, esp. pp. 179–83, 188–91, 192. See Heffernan 1975, for another opinion, rejecting the suggestion on the Buddhist source (p. 69), yet referring to the emphasis on the motif of compassion (p. 66). |

| 71 | Job, 5:23. |

| 72 | |

| 73 | |

| 74 | Richardson 1979, p. 118; Goffen, ibid, pp. 48, 139, 157; Rosand 2001, p. 100; for other dates in the history of Venice that were ‘adapted’ to the myths, see also Richardson, ibid., p. 108; Goffen, ibid, p. 149. |

| 75 | |

| 76 | Veneziano, The Virgin Blessing the Doge, a lunette on the tomb of the Doge Francesco Dandolo, Venice, Santa Maria Gloriose Dei Frari. A marble relief by Pietro Lombardo: Doge Leonardo Loredan in front of the Virgin, Venice, Doge Palace. A painting attributed to Vittore Carpaccio, The Virgin with SS. Christopher and John the Baptist and with the Doge Giovanni Mocenigo, 1478–1485, oil on canvas, 9 ft. 8¾ in. × 72½ in. (295.9 × 184.2 cm), London, The National Gallery. Giovanni Bellini, The Virgin blesses the Doge Agostino Barbarigo, 1488, oil on canvas, 8 ft. 30 in. × 87¾ in. (320 × 200 cm), Murano, San Pietro Martire. Jacopo Tintoretto (Italian, 1519–1594), The Madonna with the Doge Alvise Mocenigo and his Family, c. 1573, oil on canvas, 85 in. × 13 ft. 8⅜ in. (216 × 416.6 cm), Washington, National Gallery. Jacopo Tintoretto, The Virgin Blesses the Doge Pietro Loredan, oil on Canvas, Venice, Doge Palace. Jacopo Tintoretto, The Doge Nicolò da Ponte Invoking the Protection of the Virgin, 1584, oil on canvas, Venice, Doge Palace. |

| 77 | Giovanni Bellini’s above-mentioned (see endnote no. 3) San Giobbe Altarpiece, Ca. 1445–1487, and Sacred Allegory. See Richardson 1979, pp. 20, 117; Goffen 1986a, pp. 156–57; Bätschmann 2008, p. 138. |

| 78 | |

| 79 | |

| 80 | One can see examples of this iconography in the relief Venice, attributed to Filippo Calendario, from the west façade of the Doge Palace, Venice; in the statue Justice by Bartolomeo Buon, Porta della Carta, also in the Doge Palace, Venice; in Jacobello del Fiore’s Justice with the Angels Michael and Gabriel, 1421, oil, 133/4 × 353/8 in. (35 × 90 cm), Venice, Galleria del’Accademia; and in Justice by Bonifacio dei Pitati and his studio, Venice, Galleria dell’Accademia. Also see Goffen 1986a, p. 144; Goffen 1986b, p. 64; Rosand 2001, p. 99ff. |

| 81 | |

| 82 | God gave King Solomon superior wisdom, Kings I, 3:13; for the Biblical description of the throne, see Kings I, 10:18–20. |

| 83 | Mathew, 1:1–17; on the special link between King Solomon and the self-image of Venice, see Goffen 1986b, p. 151; Rosand 2001, pp. 96–108. |

| 84 | See Hartt’s analysis, Hartt 1940, p. 31. |

| 85 | Genesis, 49: 9. |

| 86 | Amos, 9:11: “In that day will I raise vp the tabernacle of Dauid, that is fallen, and close vp the breaches thereof, and I will raise vp his ruines, and I will build it as in the dayes of old” |

| 87 | |

| 88 | Explaining the verse “his strength is in his loins, and his force is in the navel of his belly” (Job 40:16), which describes the mythological creature Behemoth, St. Jerome translated the Hebrew word “מָתְנָיו” as “loins”, and explains, “Thus, the descendant of David, who, according to the promise is to sit upon his throne, is said to come from his loins” (St. Jerome 1893, Letter No. 22, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001022.htm). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moscovich, A. The Lion and the Wisdom—The Multiple Meanings of the Lion as One of the Keys for Deciphering Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion. Religions 2019, 10, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050344

Moscovich A. The Lion and the Wisdom—The Multiple Meanings of the Lion as One of the Keys for Deciphering Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion. Religions. 2019; 10(5):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050344

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscovich, Atara. 2019. "The Lion and the Wisdom—The Multiple Meanings of the Lion as One of the Keys for Deciphering Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion" Religions 10, no. 5: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050344

APA StyleMoscovich, A. (2019). The Lion and the Wisdom—The Multiple Meanings of the Lion as One of the Keys for Deciphering Vittore Carpaccio’s Meditation on the Passion. Religions, 10(5), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050344