Abstract

Buddhist aesthetics, as a profound intrinsic value of pleasure, has continually attracted scholars to shed light on its influential effects. Its aesthetic nature, however, has drawn on the laws of profound Buddhist thoughts, which is challenging for empiricists to generate evidence for. Though some individual components or factors deriving from Buddhist aesthetics have been developed and exploited in previous studies, a holistic construct of Buddhist aesthetics remains ambiguous and lacks a pragmatically useable measure. This study fills this gap by creating a Buddhist aesthetics scale. A total of fifteen items have been found valid and reliable to measure three determinants, namely, value, acumen, and response. This scale can be used in further empirical studies in designing objects aiming to elicit the unique Buddhist aesthetic experience. Moreover, it can be utilized in measuring Buddhist aesthetics as a determinant in relevant practices, such as religious psychotherapy, cognitive engineering, and business.

1. Introduction

A religious belief has been discussed as the embodied form of supreme beauty (Garrett 2012); research on the aesthetic appraisal of artworks is evident throughout religious studies across the world. Numerous artistic representations of the religious subject matter have worked as a sensory way to map the spiritual world onto reality, such as painting, sculpture and so forth (Kraft 1992; Pakhoutova and Helman-Wazny 2012; Male 2018). The abstract spirituality and doctrine of a specific religion can be perceived through observing religious artwork with sensational forms and symbols (Meyer 2010). For instance, the visual narration depicting the legends of the Buddha were aesthetically designed in early Buddhist art (Hallman 2006). The pictorial artworks depicting Jesus Christ carried and symbolized the hidden message throughout Christian history (Vera et al. 2017).

Recent research suggests a shifting focus on the mental experience of religion and aesthetics from the perspective of cognitive science (Long 2019). The academic conception of aesthetics refers to the perceptual attitudes and cognitive evaluation towards external objects (Adorno 2004; Shimamura and Palmer 2011). Dewey (2005) illustrates that an aesthetic experience happens when the internal meaning connects an external object with an individual. Later scholars have continued to enrich the academic understanding of aesthetic experience; that is a psychological state of mind when perceiving an artwork, which is characterized by some neurological manifestations, such as attention (Wanzer et al. 2018; Parsons 1987; Ramachandran and Hirstein 1999). For this reason, aesthetic experience has been discussed as “an aesthetics-oriented method” to nourish religious belief in the relevant studies (McRoberts 2004). Material objects with symbolic religious meanings tend to contribute to the configuration of religious experiences (Winchester 2017). The reason lies in the psychologically aesthetic power of religious practices. For example, Bychkov (2019) studied how aesthetic observation in a religious environment can influence human belief in reality.

Buddhism, known for its spirituality beyond physical reality, has differed significantly from Western rational positivism (Hummel 2010; Assandri 2019). Scholars argue that Buddhist values teach a way of understanding real life, such as life suffering (Fuderich 2007), compassion (Kraft 1992), and inner peace (Lee et al. 2013) and so forth. It has been suggested that Buddhist thoughts under these distinctive doctrines imply a transition from ethics to aesthetics (Voyce 2015). Also, it has been argued that what links Buddhism and aesthetics is the common nature of the intrinsic value of pleasure, as Buddhism advocates the aesthetic pleasure of “inner” beauty (Bahm 1957; Patnaik 2017). For instance, Buddhist artworks or objects, such as an image of the Buddha, have been regarded as the “outer” beauty manifesting the “inner” aesthetic laws of virtue in Buddhism (Cooper 2017). Indeed, many scholars have exerted efforts in defining and revealing the underlying nature of Buddhist aesthetics; it has remained ambiguous in relevant research to discover the concrete effects of Buddhism in terms of aesthetics.

More recent literature shows an increasing academic interest on the aesthetics of Buddhism in a wider range of disciplines, such as art and design (Song et al. 2018), psychotherapy (Cormack et al. 2018), cognitive engineering (Van Dam et al. 2018), ecology (Lim 2019), business (Lucas 2018; Milligan 2018) and so forth. For example, Macmillan (2006) suggested that superior design is not just about the aesthetic improvement of the quality of our lives; it is also about the value created for the viewers. According to the report “the value of good design” (CABE 2002), superior designs can perform, convert, astonish, and fulfill its purpose, sharing both social and economic values with their reviewers, particularly aesthetics value, cultural value, useable value, and emotional value. Take Zen, a specific Buddhism-related aesthetic attitude, as an example. It has been regarded as an essential appealing style in landscape design (Brown 2019). Figure 1 depicts a Zen garden in Ryōan-Ji, Tokyo, Japan. It is admired for visual simplicity by the minimalist approach. People enjoy Zen aesthetics as “less is more”. Thompson (2018) also has discussed how aesthetic experience can improve the state of Buddhist mindfulness in psychotherapy.

Figure 1.

Zen aesthetics in Ryōan-ji, Tokyo.

Buddhist aesthetics are a common phenomenon in countries with Buddhist culture, describing ‘the beauty of an inner state of mind’ or ‘the beauty of the inner reality’ (Cooper 2017). Although some research has addressed Buddhist aesthetics in different contexts, only limited research has empirically explored how aesthetic pleasure elicited by Buddhist objects should be defined and subsequently be measured, which leaves a research gap for further investigation. Also, it is necessary to holistically understand and determine the antecedents of Buddhist aesthetics, considering the significant role of Buddhist mindfulness in increasing awareness and attention to the present, decreasing negative thinking and feelings, and refreshing the mind (Thompson 2018). More specifically, most research has examined how specific components such as emptiness (Pelowski 2012), and inner peace (Lee et al. 2013) explain variations in evaluations of Buddhist aesthetic experience respectively. The results of these studies make it, consequently, difficult to help relevant researchers understand the empirical effects of the Buddhist aesthetic experience holistically. Accordingly, it is both theoretically and practically significant to explore the antecedents of Buddhist aesthetics. Thus, this study conducts an empirical approach to develop and validate a Buddhist aesthetics scale. It contributes to the current academic understanding of the impact of the aesthetic pleasure elicited by Buddhist artworks and objects.

2. Defining Buddhist Aesthetic Experience

Inada (1994) construes that Buddhist aesthetic nature derives from the momentary understanding of reality, which is characterized by dynamic elusiveness. Following this cue, people can find it aesthetically pleasing to be enlightened by Buddhist thoughts, such as the notion of nothingness and impermanence, because the fundamental beauty in Buddhism is rooted in meaning-making towards real life, which is the Buddhist philosophy of being. Many eastern scholars’ preliminary research into Buddhist paintings and poems has centered on the expression of such enlightening moments (D. Wang 1987). Consequently, the aesthetic characteristics of superiority and elegance have been argued. Zhang (1988) has elaborated such characteristics into sensible artistic forms, such as exaggerated visual proportions, lively details, and closeness, which are aimed to construct a sense of pleasure beyond momentary reality.

More recently, Pelowski (2012) has argued a more concrete cognitive model to approach the appreciation of Buddhist artworks, which is constructed by a process starting from self-image, cognitive mastery, secondary control, and meta-cognitive re-assessment to aesthetic phase. According to Pelowski’s theory based on cognitive observations, approaching religious artworks or objects can be regarded as a way of constructing an “ideal self-image”. The cognitive mastery and meta-cognitive re-assessment stage here is in line with the conception of self-realization in Buddhism, since the existence of a separate self is fundamental in Buddhist thoughts.

Prominently, Buddhist art is mundane and material at the same time. From the perspective of artistic artifacts, the definition of aesthetics refers to the emotional and experiential perceptions of the object without particular motives; it is in line with the broad term of “aesthetic response” (Hekkert et al. 2017). It happens between an observer and artifact cognitively and may not necessarily be preconditioned by an appraisal of emotion, which is slightly different from Pelowski (2012)’s argument of self-image.

Based on the aforementioned discussion, the definition of Buddhist aesthetic experience adopted here is thus a synthetic cognition towards a material object attached with Buddhist meanings, ranging from the expressive forms in Buddhist art to the cognitive response of aesthetic pleasure. Buddhist beauty is the distinctive aesthetic response elicited by meaningful material forms with Buddhist thoughts. In other words, similarly to other cognitive processes, Buddhist aesthetics are especially characterized by some fundamental laws of Buddhist appreciation of artifacts, namely, the value of realization, the acumen of details, and the response of materials.

3. Research Procedure

Although the concepts and characteristics of Buddhist aesthetics have been discussed to some extent, limited previous research has addressed the formal measurement for artworks or objects from a perceptual and cognitive perspective. It is worth noting that the development of a Buddhist aesthetics scale would contribute to the sensory evaluation of Buddhism aesthetic objects and support comparative research in Buddhist psychotherapy, Buddhist practices, Buddhist item categories, and Buddhism art, such as Buddhist paintings. In order to address this issue, we attempt to develop and construct a valid and reliable Buddhist aesthetics scale following the guidelines of scale development (Churchill 1979). This scale tends to measure the general Buddhist aesthetics experience rather than rely on a specific category. The development and validation of this scale will be presented and discussed in the following sections.

3.1. Items Generation

First of all, three major streams of relevant research were reviewed: the theoretical work of the centrality of visual aesthetics and perceived aesthetics from a psychological perspective (Workman and Caldwell 2007; Bloch et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2017; Lee and Koubek 2010; Hekkert et al. 2017), the explicit aesthetics of Buddhist items (Inada 1994; Schopen 2006), as well as religious aesthetics literature, especially the religious aesthetics of items and symbols from a sensory perspective (Meyer 2010, 2006; Prohl 2010). Then, 42 college students at a major university in the eastern part of China were recruited to describe their experience and feelings when viewing Buddhism items or symbols. The questions include, for example, “Could you describe the feeling after you have seen a beautiful Buddhist item?”, “Could you explain the special experience when you encounter some Buddhist symbols?”. Accordingly, the characteristics of Buddhist aesthetics could be summarized into three dimensions: Buddhist aesthetics value, Buddhist aesthetics acumen, and Buddhist aesthetics response (Bloch et al. 2003). A total number of 39 items are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement item categories, keywords, and references.

3.2. Refinement and Item Reduction

According to the guidelines of scale development (Churchill 1979; DeVellis 2017; Gheorghe 2018), the initial items generation process tends to be over-inclusive. Regarding this issue, an item refinement process was conducted to select specific statements, representing the whole constructs of the Buddhist aesthetics scale (Gerbing and Anderson 1988; Kim 2017). As a result, the initial 39 items were revised and refined. This was based on the validity of the contents by a panel of experts, which included five related researchers majoring in religion study, culture study and Buddhism art from a major university in the east of China. To be more specific, researchers tried to evaluate and revise each item based on its redundancy, relevance, and clarity, and then classified items to the three aforementioned theoretical dimensions (Gerbing and Anderson 1988; Gheorghe 2018). During this process, some ambiguous items were modified. For example, one item, “Owning Buddhist item or symbol that have with superior designs makes me feel good”, was ambiguous. Therefore, it was modified to “Owning Buddhist item or symbol with superior designs makes me feel good about myself”. After this process, 21 items were discarded, while 18 items remained and were clustered into three theoretical dimensions: Buddhist aesthetics value, Buddhist aesthetics acumen, and Buddhist aesthetics response (Bloch et al. 2003) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Buddhist aesthetics scale items of the three factors.

4. Scale Development and Factor Analysis

This research attempts to identify phrases as the measurement items of the Buddhist aesthetics scale and determine the related reliability and validity of different constructs. Specifically, all 18 items were formed and measured based on a 9-point Likert scale. Participants would respond to the scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree. SPSS 23 and AMOS 24 for Windows were used to conduct statistical analysis, the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of distinctive constructs, and to examine the model fit indices of the theoretical structure.

4.1. Pre-Study

Following the scale development procedure (DeVellis 2017; Kim 2017), 102 undergraduate students from a major university in eastern China were recruited in the pilot study to determine the consistency and clarity of the current scale. The scale was formatted in a 9-point Likert scale. Some confusing questions were accordingly modified. For example, “I have long developed a skill to differentiate the difference in Buddhist items or symbol” was modified to “Being able to see subtle differences in Buddhist item or symbol designs is one skill that I have developed over time”. Accordingly, we tried to ensure the consistency and clarity of this scale. Besides, the Cronbach’s alpha of the pilot study was 0.96, which was considered to be reliable.

4.2. Respondents

Buddhism was introduced to China during the Han dynasty and influenced and interacted with traditional Chinese culture, and eventually become part of Chinese ideology (Assandri 2019; Li et al. 2018). Chinese people are quite familiar with Buddhism and consider Buddhism as part of their daily lives (Guang 2013). Therefore, conducting this study in the context of China was considered as appropriate and effective. The sample contained 257 unique responses from China. To be more specific, 191 (74.31%) participants were women and 66 (25.69%) were men. The participants’ ages ranged from 12–60: 113 were between the age of 12 and 20 (31.65%); 109 were between the age of 21 and 22 (42.41%), and 35 were between the age of 23 and 60 (25.94%). In terms of residence, 210 were from the eastern part of China (81.71%) and 47 were from the northern part of China (18.29%).

4.3. Data Screening and Exploratory Factor Analysis

The normal distribution of the current data set was validated through the skewness and kurtosis index. The threshold value for skewness and kurtosis is between −2 and 2 (Groeneveld and Meeden 1984). The results showed that Skewness ranged from −0.258 to 0.08 and kurtosis ranged from −0.104 to 0.719, which confirms normal univariate distribution.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to reduce the dimensionality and explore the appropriate structure of the current scale. Therefore, a principal axis factoring analysis with varimax orthogonal rotation was conducted. The results showed the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling was 0.973 and Bartlett’s test (chi-square) value was 8487.12 (p = 0.000), suggesting that it is suitable for factor analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell 1996). Each construct was examined and determined in terms of eigenvalues and the scree plot (W. Wang 2002). In terms of item selection for the three factors, three items were discarded because of double loading onto multiple factors with coefficients greater than 0.50 (Roemer and Gratz 2004; Woosnam and Norman 2016). Specifically, item R2 “If a Buddhist item or symbol’s design really ‘speaks’ to me, I feel a strong motivation to approach”, item V4 “Beautiful Buddhist item or symbol designs make our world a better place to live”, and item A5 “I can discover the unique beauty in a Buddhist item or symbol” all have double-loading on two factors (with loadings of 0.552, 0.544 and 0.512 on factors 3, 1 and 2, respectively). Factor loadings with varimax rotation were provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Varimax rotation method for the Buddhist aesthetics scale in three factors.

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the initial scale with 18 items. However, the results showed that the original model did not provide an adequate model fit (χ2(132) = 438.057, p = 0.000; SRMR = 0.046; RMSEA = 0.095; CFI = 0.964; NFI = 0.950; IFI = 0.964; TLI = 0.959; and GFI = 0.838). Following the suggestions from Woosnam and Norman (2016), reasonable modifications were introduced based on the correlated residuals and cross-loadings, producing a good model fit (Hooper et al. 2008). Regarding this, the first modified model contained 15 items excluding the double-loading items (R2, V4 and A5). The results showed that this model had a good model fit (χ2(87) = 241.716, p = 0.000; SRMR = 0.040; RMSEA = 0.083; CFI = 0.978; NFI = 0.966; IFI = 0.978; TLI = 0.973; and GFI = 0.893). The second modified model contained 14 items excluding R1, producing a better model fit for the data (χ2(74) = 169.536, p = 0.000; SRMR = 0.033; RMSEA = 0.071; CFI = 0.985; NFI = 0.974; IFI = 0.985; TLI = 0.982; and GFI = 0.914). Table 4 presents the model fit indices for the original and revised models.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of the constructs.

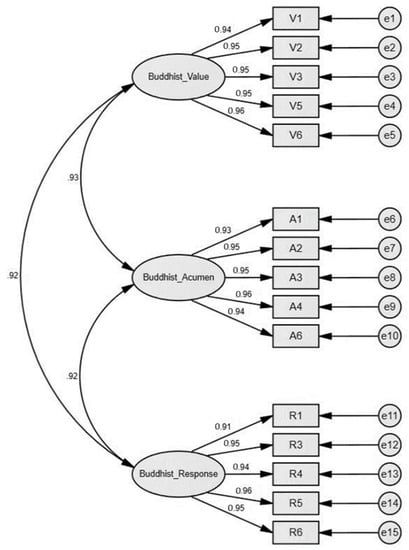

Although the model with 14 items achieved a better model fit, we still supported the second model that includes R1 “Sometimes the way a Buddhist item or symbol looks seems to reach out and grab me”. There are two reasons why we preserved R1: firstly, “to reach or to grab” was the recurring statements in the item generation process; secondly, the modification indices were primarily the tools which should follow the previous theory (Hooper et al. 2008; Roemer and Gratz 2004; Woosnam and Norman 2016). Consequently, the scale with 15 items was finalized to three distinct constructs, factors 1–3, with the standard coefficients ranging from 0.94–0.96, 0.93–0.96, and 0.91–0.96, respectively. Even the GFI of this model (0.893) is slightly below the threshold. Figure 2 shows the path diagram of the Buddhist aesthetics scale.

Figure 2.

The path diagram of the Buddhist aesthetics scale.

4.5. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Confirmatory factory analysis was conducted to determine the convergent and discriminant validity of the current scale. For convergent validity, the standardized factor loadings should be above the threshold, 0.5 or above (Huang et al. 2013), C.R. (t-value) should be above the threshold, 2 or above, and the averaged variances expected (AVE) value should also be above the threshold, 0.5 or above (Fornell and Larcker 2006). Table 5 shows that the C.R. (t-value), standardized factor loadings, and AVE achieved adequate values.

Table 5.

Convergent and discriminant validity of the Buddhist aesthetics scale.

The correlation coefficients, the maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV) tend to be used to assess discriminant validity. To specify, the threshold for MSV and ASV values should be less than the AVE value (Fornell and Larcker 2006). The results of Table 6 show that, in the current study, all the AVE values are above the MSV and ASV values, suggesting that the four constructs achieved satisfactory discriminant validity.

Table 6.

Correlation and discriminant validity of the Buddhist aesthetics scale.

5. Discussion, Conclusions, and Limitations

Buddhist aesthetics, as a profound intrinsic value of pleasure, play a significant role in increasing awareness to the present, decreasing negative feelings, and refreshing the mind, which has continually attracted scholars to shed light on its influential effects (Thompson 2018). It is a frequent phenomenon in countries with Buddhist culture. Indeed, different emerging fields, such as design (Song et al. 2018) and psychotherapy (Cormack et al. 2018), have realized that the Buddhist aesthetic experience tends to positively enhance mental spirituality and ‘inner’ pleasure (Shimamura and Palmer 2011; Thompson 2018). Its aesthetic nature draws on the underlying laws of Buddhist thoughts; however, antecedents are seldom empirically discussed (Inada 1994). Though some individual components or factors deriving from Buddhist aesthetics, such as inner peace (Lee et al. 2013) and emptiness (Pelowski 2012), have been developed and exploited in previous studies, a holistic construct of Buddhist aesthetics remains ambiguous and lacks a pragmatically useable measure.

In order to achieve a better understanding of Buddhist aesthetics, the current study fills this gap by developing and validating a Buddhist aesthetics scale. Regarding this, this study has several theoretical contributions. To begin with, it is the first development and validation of a Buddhist aesthetics scale. To date, Buddhist aesthetics have only been qualitatively explored in different contexts. This study provides a quantitative way to measure the perception of Buddhist aesthetics, at least for the impact of the aesthetic pleasure elicited by Buddhist artworks and objects. Second, it contributes to Buddhist aesthetics literature by exploring the antecedents and the relationship between each construct since it extends the scope of previous research which are mainly discussed from the perspective of inner peace or inner pleasure, rather than from a holistic perspective. Also, this study has some practical implications. For example, it can be utilized in measuring Buddhist aesthetics as a determinant in relevant practices, such as religious psychotherapy, cognitive engineering, and business.

To specify, this study has explored the relevant constructs and factors by reviewing previous literature and studies. Finally, three prominent determinants have been revealed, namely, Buddhist aesthetics value, Buddhist aesthetics acumen, and Buddhist aesthetics response (see Table 1). A total of fifteen items has been found valid and reliable to measure these three determinants. These items were tested to be reliable, valid and generalizable. Therefore, this scale tends to capture a holistic measurement for objects associated with the aesthetic pleasure of Buddhism, ranging from experiential cognition to behavior level.

The scale developed in this study has been aimed to measure the immediate perceptions when observing an object and is, however, not necessarily restricted to use in the visual condition. Since it measures the Buddhist aesthetic experience and pleasure as such, it could, therefore, tend to be operated to capture the consequent perceptions of various kinds of other multimodal instances, whether they are a Buddhist poem, a Buddhist song, or a Buddhist movie clip. Studies in other diverse fields are encouraged to test its generalizability further.

Conceptually, Buddhist aesthetics has been argued as concrete and singular senses in this study from a practical perspective. However, as a latent construct, it cannot be directly and objectively observed. Consequently, choosing more items from our scale would be more effective and accurate to capture a holistic construct of Buddhist aesthetics.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, this scale has been validated only in the context of an Asian country, to be specific, China. Buddhist diversity, nevertheless, should be taken into considerations in further studies as scholars have noted that the thinking and practices of Buddhism are different across regions (Padgett 2000; Prebish and Baumann 2013). Moreover, it would be theoretically significant to compare the difference in the perceptions across different Buddhist regions. Secondly, the validity of the scale in different languages remains ambiguous. Additional studies are needed to test the generalizability when translating the scale into different languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, research design, formal analysis, and writing—review and editing, Z.Q.; Data collection, methodology, data processing, and data curation, Y.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. 2004. Aesthetic Theory. London: A&C Black, p. 416. [Google Scholar]

- Assandri, Friederike. 2019. Conceptualizing the Interaction of Buddhism and Daoism in the Tang Dynasty: Inner Cultivation and Outer Authority in the Daode Jing Commentaries of Cheng Xuanying and Li Rong. Religions 10: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahm, Archie J. 1957. Buddhist Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 16: 249–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, Peter H., Frédéric F. Brunel, and Todd J. Arnold. 2003. Individual Differences in the Centrality of Visual Product Aesthetics: Concept and Measurement. Journal of Consumer Research 29: 551–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kendall H. 2019. Japanese Gardens and Landscapes, 1650–1950 by Wybe Kuitert. The Journal of Japanese Studies 45: 204–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, Oleg. 2019. ‘He Who Sees Does Not Desire to Imagine’: The Shifting Role of Art and Aesthetic Observation in Medieval Franciscan Theological Discourse in the Fourteenth Century. Religions 10: 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CABE. 2002. The Value of Good Design: Economic and Social Value. London: Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, Gilbert A. 1979. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research 16: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, David E. 2017. Buddhism, Beauty and Virtue. In Artistic Visions and the Promise of Beauty. Cham: Springer, pp. 125–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, Dulcie, Fergal W. Jones, and Michael Maltby. 2018. A ‘Collective Effort to Make Yourself Feel Better’: The Group Process in Mindfulness-Based Interventions. Qualitative Health Research 28: 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, Robert F. 2017. Scale Development: Theory and Applications, 16th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, John. 2005. Art as Experience. New York: Berkley Pub. Group. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 2006. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuderich, Urakorn Khajornwit. 2007. Beyond Survival: A Study of Factors Influencing Psychological Resilience among Cambodian Child Survivors. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Stephen M. 2012. Theological Aesthetics. In The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbing, David W., and James C. Anderson. 1988. An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. Journal of Marketing Research 25: 186–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, Huza. 2018. The Psychometric Properties of a Romanian Version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15). Religions 10: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneveld, Richard A., and Glen Meeden. 1984. Measuring Skewness and Kurtosis. The Statistician 33: 391–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, Xing. 2013. Buddhist Impact on Chinese Culture. Asian Philosophy 23: 305–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, Ralph J. 2006. The Art Object in Hindu Aesthetics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 12: 493–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, Paul, T. W. Allan Whitfield, Lin-Lin Chen, Helmut Leder, Janneke Blijlevens, and Clementine Thurgood. 2017. The Aesthetic Pleasure in Design Scale: The Development of a Scale to Measure Aesthetic Pleasure for Designed Artifacts. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 11: 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael Mullen. 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Chun-Che, Yu-Min Wang, Tsin-Wei Wu, and Pei-An Wang. 2013. An Empirical Analysis of the Antecedents and Performance Consequences of Using the Moodle Platform. International Journal of Information and Education Technology 3: 217–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, Leonard M. 2010. Handbook of Religion and Mental Health. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61: 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, Kenneth K. 1994. The Buddhist Aesthetic Nature: A Challenge to Rationalism and Empiricism. Asian Philosophy 4: 139–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sungwon. 2017. Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment of University Students. Religions 8: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, Kenneth Lewis. 1992. Inner Peace, World Peace: Essays on Buddhism and Nonviolence. SUNY Series in Buddhist Studies; Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Sangwon, and Richard J. Koubek. 2010. Understanding User Preferences Based on Usability and Aesthetics before and after Actual Use. Interacting with Computers 22: 530–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yi-Chen, Yi-Cheng Lin, Chin-Lan Huang, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2013. The Construct and Measurement of Peace of Mind. Journal of Happiness Studies 14: 571–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Miao, Yun Lu, Fenggang Yang, Miao Li, Yun Lu, and Fenggang Yang. 2018. Shaping the Religiosity of Chinese University Students: Science Education and Political Indoctrination. Religions 9: 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Hui Ling. 2019. Environmental Revolution in Contemporary Buddhism: The Interbeing of Individual and Collective Consciousness in Ecology. Religions 10: 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Jeffery. 2019. Religious Experience, Hindu Pluralism, and Hope: Anubhava in the Tradition of Sri Ramakrishna. Religions 10: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Michael. 2018. The Need for and Nature of Buddhist Economics. Cham: Springer, pp. 205–21. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, Sebastian. 2006. Added Value of Good Design. Building Research & Information 34: 257–71. [Google Scholar]

- Male, Emile. 2018. The Gothic Image. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McRoberts, Omar M. 2004. Beyond Mysterium Tremendum: Thoughts toward an Aesthetic Study of Religious Experience. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 595: 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2006. Religious Sensations: Why Media, Aesthetics and Power Matter in the Study of Contemporary Religion. In Inaugural Lecture. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit. 2010. Aesthetics of Persuasion: Global Christianity and Pentecostalism’s Sensational Forms. South Atlantic Quarterly 109: 741–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, Matthew D. 2018. Corporate Bodies in Early South Asian Buddhism: Some Relics and Their Sponsors According to Epigraphy. Religions 10: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, Douglas. 2000. ‘Americans Need Something to Sit On,’ or Zen Meditation Materials and Buddhist Diversity in North America. Journal of Global Buddhism 1: 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Pakhoutova, Elena, and Agnieszka Helman-Wazny. 2012. Tools of Persuasion: The Art of Sacred Books. Orientations Magazine 43: 124–29. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Michael J. 1987. How We Understand Art: A Cognitive Developmental Account of Aesthetic Experience. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, Priyadarshi. 2017. The ‘Aesthetic in Everyday Life’: An Exploration through the Buddhist Concept of Vikalpa. Cham: Springer, pp. 237–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pelowski, Matthew. 2012. Satori, Koan and Aesthetic Experience: Exploring the ‘Realization of Emptiness’ in Buddhist Enlightenment via an Empirical Study of Modern Art. Psyke & Logos 2: 236–68. [Google Scholar]

- Prebish, Charles S., and Martin Baumann. 2013. Westward Dharma: Buddhism beyond Asia. Oakland: University of California Press, vol. 40, p. 6368. [Google Scholar]

- Prohl, Inken. 2010. Religious Aesthetics in the German-Speaking World Central Issues, Research Projects, Research Groups. Material Religion 6: 237–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, Vilayanur S., and William Hirstein. 1999. The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies 6: 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer, Lizabeth, and Kim L Gratz. 2004. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 30: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schopen, Gregory. 2006. The Buddhist ‘Monastery’ and the Indian Garden: Aesthetics, Assimilations, and the Siting of Monastic Establishments. Journal of the American Oriental Society 126: 487–505. [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura, Arthur P., and Stephen E. Palmer. 2011. Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Xiao, Zhaoqi Wu, Li Ouyang, and Jei Ling. 2018. Influence of Song Porcelain Aesthetics on Modern Product Design. Cham: Springer, pp. 166–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 1996. Using Multivariate Statistics. New York: Harper Collins, p. 980. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Geoffrey. 2018. Aesthetic Experience and Mindfulness. Human Science Perspectives 2: 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam, Nicholas T., Marieke K. van Vugt, David R. Vago, Laura Schmalzl, Clifford D. Saron, Andrew Olendzki, Ted Meissner, Sara W. Lazar, Catherine E. Kerr, Jolie Gorchov, and et al. 2018. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science 13: 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, Vicente, Carmen Ávila, Vicente Jara Vera, and Carmen Sánchez Ávila. 2017. Four Versions of the Christus by the Massys: Deciphering the Meaning of the Letters. Religions 8: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyce, Malcolm. 2015. From Ethics to Aesthetics: A Reconsideration of Buddhist Monastic Rules in the Light of Michel Foucault’s Work on Ethics. Contemporary Buddhism 16: 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Dianhong. 1987. Overview of Buddhist aesthetic studies in recent years. Journal of Central China Normal University: Humanities and Social Sciences Edition 4: 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weng. 2002. Evaluating the Use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Taiwan: 1993–1999. Chinese Journal of Psychology 44: 239–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzer, Dana Linnell, Kelsey Procter Finley, Steven Zarian, and Noreen Cortez. 2018. Experiencing Flow While Viewing Art: Development of the Aesthetic Experience Questionnaire. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 12: 1–12. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Faca0000203 (accessed on 27 May 2019). [CrossRef]

- Winchester, Daniel. 2017. ‘A Part of Who I Am’: Material Objects as ‘Plot Devices’ in the Formation of Religious Selves. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 56: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woosnam, Kyle M., and William C. Norman. 2016. Scale Development and Factor Structure Confirmation of Constructs within Durkheim’s Theoretical Framework of Emotional Solidarity. Whitehall: Travel and Tourism Research Association, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Workman, Jane E., and Lark F. Caldwell. 2007. Centrality of Visual Product Aesthetics, Tactile and Uniqueness Needs of Fashion Consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 31: 589–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Freeman, Adriana Samper, Andrea C. Morales, and Gavan J. Fitzsimons. 2017. It’s Too Pretty to Use! When and How Enhanced Product Aesthetics Discourage Usage and Lower Consumption Enjoyment. Journal of Consumer Research 44: 651–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiaoling. 1988. The Formation and Transformation of the Aesthetic Characteristics of Chinese Buddhist Art. Journal of Anhui Normal University (Humanities & Social Sciences) 31: 86–88. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).