Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Virūpākṣa

3. Nāth Śaivism and Vajrayāna in the Konkan

3.1. Nāth Śaivism in the Konkan

3.2. Vajrayāna in the Konkan

Then in Koṅkaṇa he embarked and went to the west up to an island called ḥgro ling[,] in Sanskrit Dramiladvīpa. In the language of the Muhammadans, the barbarians and [the inhabitants] of the small island, it is called la sam lo ra na so (in Śambh: sam lo ra na so). In that island the teachings of the guhyamantras are largely diffused. He heard these from a paṇḍit called Sumati who had acquired the mystic revelations (abhijñā), the mystic power of the Saṃvara (tantra) and of the Hevajra (tantra) and then he learnt the detailed explanation of the Hevajratantra. This Hevajratantra belongs to the system of the Ācārya Padmasambhava. Generally speaking, the tradition of the fourfold tantras is still uninterrupted in that island, and if we except the sublime and largely diffused Kālacakratantra, whatever is in India is also there such as the (Vajra)kīlatantra and the Tantra of the daśakrodhas, many Heruka-tantras, Vajrapāṇi, mkhaḥ ldiṅ (Garuḍa), Māmakī, Mahākāla, etc. Then the sublime order of Hayagrīva which is largely spread in India is to be found there. Moreover there are many sacred teachings (chos) belonging to the Tantras expounded by Padmasambhava. Though the community is numerous, the rules of the discipline are not so pure. The monks wear black garments and usually drink intoxicating liquors …”.(Tucci 1931, p. 690)

4. Vajrayāna-Śaiva Interaction

4.1. Panhale Kaji

4.2. Kadri

5. Final Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| nak | National Archives Kathmandu |

| ngmpp | Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project |

References

Primary Sources

Amaraughaprabodha, ongoing critical edition by Jason Birch.Amṛtasiddhi, ongoing critical edition by James Mallinson and Péter-Dániel Szántó.Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmyam, ed. Śambhu Śarmā Kaḍava. Kāśī: Gorakṣa Ṭilla Yoga Pracāriṇī. 1957.Gopālarājavaṃśāvalī, ed. and tr. by Dhanavajra Vajrācārya and Kamal P. Malla. Nepal Research Centre Publication 9. Stuttgart: Steiner. 1985.Grub thob brgyad bcu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus, see Robinson 1979.Tārārahasyam of Brahmānanda, ed. Jīvānandavidyāsāgara Bhaṭṭācārya. Calcutta: Calcutta Press. 1896.Navanāthacharitra of Gauraṇa, ed. K. Ramakrishnaiya. Madras University Telegu Series No. 7. Madras. 1937.Nityāhnikatilaka. nak 3–384, ngmpp A41/11; palm-leaf; dated c. 1452.Nepālabhūpavaṃśāvalī. See Bajracharya and Michaels 2015.Bodhisattvabhūmi, ed. Wogihara. 1930–1936. Tokyo: Sankibo.Yogajāgama Institut français de Pondichéry transcript T0024.Virūpākṣapañcāśikā with the commentary of Vidyācakravartin, ed. T. Gaṇapati Śāstrī. Trivandrum Sanskrit Series 9. Trivandrum. 1910.Vivekadarpaṇa, ed. V.D. Kulkarni. Marathi Journal Vol. 6, pp. 89-129. Osmania University: Hyderabad. 1971.Ṣaṭsāhasrasaṃhitā. ngmpp b32–6.Sahasrāgama Institut français de Pondichéry transcript T0033.Suprabhedāgama. Published 1931 ce by Devīkoṭaparipālanasaṃgha, editor not named. Transcription available at muktabodha.org.Suvarṇaprabhāsottama, ed. Prods Oktor Skjærvø in This most excellent shine of gold, king of kings of sūtras: The Khotanese Suvarṇaprabhāsottama. 2 Vols. Harvard University. 2004.Sekoddeśa, ed. Giacomella Orofino. Rome: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. 1994.South Indian Inscriptions (Texts) Volume VII. Miscellaneous Inscriptions from the Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada Countries, ed. K.V. Subrahmanya Aiyer. Calcutta: Government of India. 1932.Haṭhapradīpikā of Svātmārāma, ed. Svāmī Digambarjī and Dr Pītambar Jhā. Lonavla: Kaivalyadhām S.M.Y.M. Samiti. 1970.Hevajratantra, ed. David L. Snellgrove in The Hevajra Tantra, A Critical Study. Part II Sanskrit and Tibetan Texts. London: OUP. 1959.Secondary Sources

- Acri, Andrea. 2015. Revisiting the Cult of “Śiva-Buddha” in Java and Bali. In Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern and Early Modern Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, pp. 261–82. [Google Scholar]

- Acri, Andrea. 2016. Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia. Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Singapore: ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Acri, Andrea. 2018. Maritime Buddhism. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Available online: http://oxfordre.com/religion/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.001.0001/acrefore-9780199340378-e-638?rskey=zElCRl&result=1 (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- Badger, George Percy. 1863. The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. Translated from the original Italian Edition of 1510, with a Preface, by John Winter Jones, Esq., F.S.A., and edited, with notes and an introduction, by George Percy Badger. London: The Hakluyt Society. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Ian. 2018. Tibetan Yoga: Somatic Practice in Vajrayāna Buddhism and Dzogchen. In Yoga in Transformation. Vienna: V& R Unipress, pp. 405–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bajracharya, Manik, and Axel Michaels. 2016. Nepālikabhūpavaṃśāvalī. History of Kings of Nepal. A Buddhist Chronicle. Introduction and Translation. Kathmandu: Himal Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bankar, Amol. 2013. Two Inscriptions from the Ghorāvadeśvara Caves near Shelarwadi. In Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 2011 (Volume XCII). Pune: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- PG Bhatt. 1975. Studies in Tuḷuva History and Culture. Manipal: P.G. Bhatt. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, Jason. 2011. The Meaning of haṭha in early Haṭhayoga. Journal of the American Oriental Society 131: 527–54. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, Jason. Forthcoming. The Amaraughaprabodha: New Evidence on its Manuscript Transmission. In Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. Leiden: Brill.

- Bisschop, Peter. 2018. Buddhist and Śaiva Interactions in the Kali Age: The Śivadharmaśāstra as a Source of the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra. Indian-Iranian Journal 61: 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopearachchi, Osmund. 2014. Sri Lanka and Maritime Trade: Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara as the Protector of Mariners. In Asian Encounters: Exploring Connected Histories. London: OUP, pp. 162–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillier, Véronique. 2008. Itinérance et vie Monastique. Les Ascètes Nāth Yogīs en Inde Contemporaine. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de L’homme. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillier, Véronique. 2009. The Pilgrimage to Kadri Monastery (Mangalore, Karnataka): A Nāth Yogī Peformance. In Patronage and Popularisation, Pilgrimage and Procession. Channels of Transcultural Translation and Transmission in Early Modern South Asia. Papers in Honour of Monika Horstmann. Studies in Oriental Religions 58. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 135–46. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, George Weston. 1938. Gorakhnāth and the Kānphaṭa Yogīs. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya, Debiprasad. 1970. Tāranātha’s History of Buddhism in India. Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study. [Google Scholar]

- Cowell, Edward Byles, and Julius Eggeling. 1876. Catalogue of Buddhist Sanskrit Manuscripts in the Possession of the Royal Asiatic Society (Hodgson Collection). The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 8: 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, Shashibhushan. 1946. Obscure Religious Cults, 3rd ed. Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald. 2002. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Ronald M. 2005. Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Prasannavadan Bhagwanji. 1954. Buddhist Antiquities in Karnataka. Journal of Indian History 32: 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande, Madhusudan Narhar. 1986. The Caves of Panhāle-Kāji (Ancient Pranālaka); New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

- Dowman, Keith. 1985. Masters of Mahamudra. Songs and Histories of the Eighty-Four Buddhist Siddhas. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, John R. 2006. Shifting Forms of the Wandering Yogi: The Teyyam of Bhairavan. In Masked Ritual and Performance in South India: Dance, Healing and Possession. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, pp. 147–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, Amitav. 1994. In an Antique Land. London: Granta. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, Shobhana. 1990. Kanheri Inscriptions. Pune: Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, Dominic. 1998. Bhaṭṭa Rāmakaṇṭha’s Commentary on the Kiraṇatantra. Volume 1: Chapters 1–6. Critical Edition and Annotated Translation. Pondicherry: Publications de l’Institut français d’Indologie. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, Dominic. 2004. The Parākhyatantra. A Scripture of the Śaiva Siddhānta. A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation. Pondicherry: Publications de l’Institut français d’Indologie. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, Dominic. 2011. The Throne of Worship: An ‘Archaeological Tell’ of Religious Rivalries. Studies in History 27: 221–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, Edward. 1892. The Travels of Pietro della Valle in India. From the old English Translation of 1664 by G. Havers. London: The Hakluyt Society. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwedel, Albert. 1916. Die Geschichten der vierundachtzig Zauberer (Mahāsiddhas) aus dem Tibetischen übersetzt. Leipzig: Teubner. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2016. Converting the Dākinī: Goddess Cults and Tantras of the Yoginīs between Buddhism and Śaivism. In Tantric Traditions in Transmission and Translation. New York City: OUP, pp. 37–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hatley, Shaman. 2018. The Brahmayāmalatantra or Picumata, Volume I, Chapters 1–2, 39–40 and 83. Revelation, Ritual, and Material Culture in an Early Śaiva Tantra. Pondicherry: École française d’Extreme-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, Harunaga. 2008. Himalayan Encounter: the teaching Lineage of the Marmopadeśa. Studies in the Vanaratna Codex 1: 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson, Harunaga, and Sferra Francesco. 2014. The Sekanirdeśa of Maitreyanātha (Advayavajra) with the Sekanirdeśapañjikā of Rāmapāla. Critical Edition of the Sanskrit and Tibetan Texts with English Translation and Reproductions of the MSS. Serie Orientale Roma fondata da Giuseppe Tucci Vol. CVII. Napoli: Universita degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”. [Google Scholar]

- Jaini, Padmanabh. 1980. The Disappearance of Buddhism and the Survival of Jainism: A Study in Contrast. In Studies in History of Buddhism. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, pp. 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Jamal André. 2018. A Poetics of Power in Andhra, 1323–1450 ce. Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of the Division of the Humanities, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kandahjaya, Hudaya. 2016. Saṅ Hyaṅ Kamahāyānikan, Borobudur, and the Origins of Esoteric Buddhism in Indonesia. In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia. Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons. Singapore: ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute, pp. 67–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kasthuri, K. Anusha. 2016. Preliminary Investigation of Sri Lankan Copper-alloy Statues. STAR: Science & Technology of Archaeological Research 2: 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jinah. 2014. Local Visions, Transcendental Practices: Iconographic Innovations of Indian Esoteric Buddhism. History of Religions 54: 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, Csaba. Forthcoming. Matsyendrasaṃhitā. Pondicherry: École française d’Extreme-Orient.

- Kvaerne, Per. 1977. An Anthology of Buddhist Tantric Songs: A Study of the Caryāgīti. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi, Sylvain. 1905. Le Népal: Étude Historique d’un Royaume Hindou. Paris: Ernest Leroux, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, John K. 1980. Karunamaya. The Cult of Avalokitesvara-Matsyendranath in the Valley of Nepal. Kathmandu: Sahayogi Prakashan. [Google Scholar]

- Luczanits, Christian. 2006. The Eight Great Siddhas in Early Tibetan Painting. In Holy Madness: Portraits of Tantric Siddhas. New York: Rubin Museum of Art and Chicago: Serindia Publications, pp. 76–91. [Google Scholar]

- Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena. 1937. Dictionary of Pali Proper Names. London: Luzac & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Malla, Shiva Raj Shreshtha. 2006. Nanyadeva, His Ancestors and Their Abhijana (Original Homeland). Ancient Nepal 160: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2011. Nāth Saṃpradāya. In Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Leiden: Brill, vol. 3, pp. 407–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson, James. 2013. Yogic Identities: Tradition and Transformation. Smithsonian Institute Research Online. Available online: http://archive.asia.si.edu/research/articles/yogic-identities.asp (accessed on 14 April 2019).

- Mallinson, James. 2014. Hathayoga’s Philosophy: A Fortuitous Union of Non-Dualities. Journal of Indian Philosophy 42: 225–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson, James. Forthcoming a. The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga’s tantric Buddhist source text. In Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions. Leiden: Brill.

- Mallinson, James. Forthcoming b. Yoga and Yogis: the Texts, Techniques and Practitioners of Early Haṭhayoga. Pondicherry: EFEO.

- Mathew, Kalloor Mathen. 1988. History of the Portuguese Navigation in India, 1497–1600. Delhi: Mittal Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, Axel. 1985. On 12th-13th Century relations between Nepal and South India. Journal of the Nepal Research Centre VII: 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Adrián. 2011. Matsyendra’s ‘Golden Legend’: Yogi Tales and Nath Ideology. In Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Nāths. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. 109–28. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju, S. 1969. A Rare Śaivo-Buddhist Work with Vaishnavite Interpolations. In Kannada Studies. Mysore: Institute of Kannada Studies, vol. 3, pp. 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju, S. 1983. Vestiges of Buddhist Art. Marg 35: 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, John. 1998. The Epoch of the Kālacakratantra. Indo-Iranian Journal 41: 319–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondračka, Lubomír. 2011. What should Mīnanāth do to save his life? In Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Nāths. New York: State University of New York Press, pp. 129–42. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, M. Govind. 1946. The Date of Gorakhanātha. New Indian Antiquary 8: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Paranavitana, Senarat. 1928. Mahāyānism in Ceylon. Ceylon Journal of Science Section G.—Archaeology, Ethnology, Etc. 2: 35–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, K. B. 1912. The Ajivikas, a Sect of Buddhist Bhikshus. The Indian Antiquary 41: 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Raeside, Ian M. P. 1982. Dattātreya. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 45: 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, Yadubir Singh. 2009. Hill Fort of Anarta: Discovery of a Unique Early Historical Fort with Cave Dwellings, Buddhist Idols and Remains at Taranga in North Gujarat. Puratattva 39: 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, Gethin. Forthcoming. Rock-cut Buddhist Monasteries of the Southern Konkan. In Pratnamaṇi Felicitation Volume of Prof. Vasant Shinde. New Delhi: B.R. Publishing House.

- Reinelt, Kurt Joachim. 2000. Das Vivekadarpaṇa. Textanalyse und Erlauterungen zur Philosophie und praktischen Erlösungslehre der Nāthayogīs in Mahārāṣṭra. Heidelberg: Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Fakultät fïr Orientalistik und Altertumswissenschaft der Universität Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, James B. 1979. Buddha’s Lions: The Lives of the Eighty-Four Siddhas. Berkeley: Dharma Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saletore, Bhasker Anand. 1936. Ancient Karnāṭaka Vol.1 History of Tuḷuva. Poona Oriental Series No.53. Poona: Oriental Book Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Saletore, Bhasker Anand. 1937. The Kānaphāṭa [sic] Jogis in Southern History. The Poona Orientalist 1: 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 1994. Vajrayāna: Origin and Function. In Buddhism into the Year 2000. International Conference Proceedings. Bangkok/Los-Angeles: Dhammakaya Foundation, pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2001. History through Textual Criticism in the study of Śaivism, the Pañcarātra and the Buddhist Yoginītantras. In Les Sources et le temps. Sources and Time: A Colloquium, Pondicherry, 11–13 January 1997. Edited by François Grimal. Publications du DéPartement d’Indologie 91. Pondicherry: Institut Français de Pondichéry/École Française d’Extrême-Orient, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2005. Religion and the State: Initiating the Monarch in Śaivism and the Buddhist Way of Mantras. Unpublished Article. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2009. The Śaiva Age. In Genesis and Development of Tantrism. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, pp. 41–349. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2011. Śaivism, Society and the State. Unpublished paper. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, Alexis. 2012. The Śaiva Literature. Journal of Indological Studies, 1–113, Numbers 24 and 25 (2012–2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sarde, Vijay. 2014. Nath-Siddhas [sic] Sculptures on the Someshwara Temple at Pimpri-Dumala in Pune. Bulletin of the Deccan College 74: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Sarde, Vijay. 2016. Art and Architecture of Someshwar Temple at Pimpri-Dumala, Pune District, Maharashtra. Historicity Research Journal 2: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sarde, Vijay. 2017. Paścimī Dakkhan se prāpt Matsyendranāth aur Gorakṣanāth ke nav anveṣit Mūrti-Śilp. Arṇava 6: 94–113. [Google Scholar]

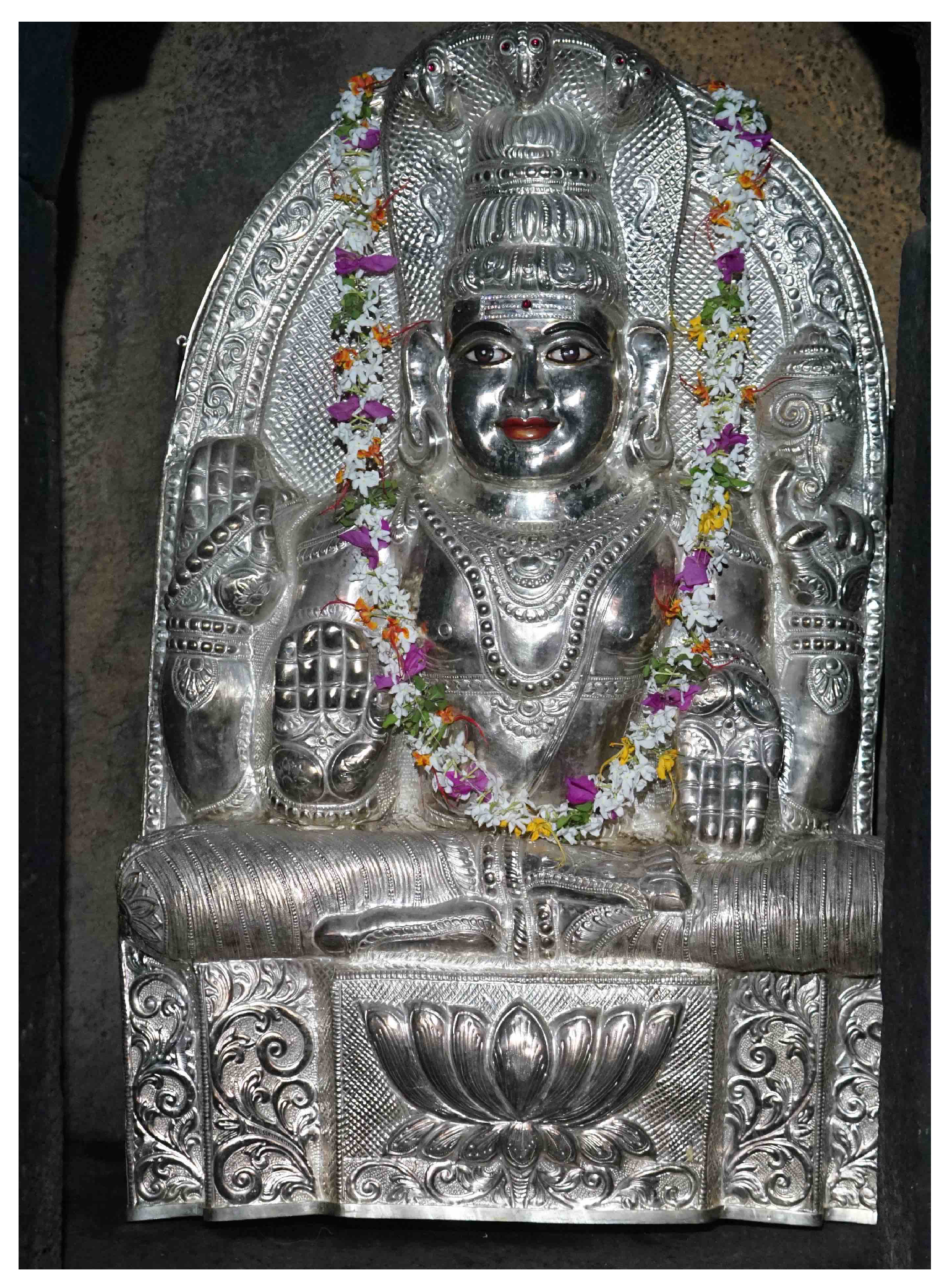

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta. 1939. Foreign Notices of South India: From Megasthenes to Ma Huan. Madras: University of Madras. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, Kurtis R. 2002. The Attainment of Immortality: From Nāthas in India to Buddhists in Tibet. Journal of Indian Philosophy 30: 515–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurleer, Pauline Lunsingh. 2008. The well-Kknown Javan statue in the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, and its place in Javanese sculpture. Artibus Asiae 68: 287–332. [Google Scholar]

- Schoterman, Jan Anthony. 1975. Some remarks on the Kubjikāmatatantra. ZDMG Supplement III 2: 932–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Sukumar. 1956. The Nātha Cult. In The Cultural Heritage of India. Vol. 4: The Religions. Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, pp. 280–90. [Google Scholar]

- Seyfort Ruegg, David. 2001. A Note on the Relationship between Buddhist and ‘Hindu’ Divinities in Buddhist Literature and Iconology: The laukika/lokottara Contrast and the Notion of an Indian ‘Religious Substratum’. In Le parole e i marmi. Studi in onore di Raniero Gnoli nel suo 70∘ compleanno. Rome: Istituto per l’Africa e l’Oriente, pp. 735–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sferra, Francesco. 2003. Some Considerations on the Relationship between Hindu and Buddhist Tantras. In Buddhist Asia 1, Papers from the First Conference of Buddhist Studies Held in Naples in May 2001. Kyoto: Italian School of East Asian Studies, pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Umakant Premanand. 1957. Nāth Siddhoṃ kī Prācīn Śilpamūrtiyāṃ. Nāgarīpracāriṇī Patrikā varṣa 62: 174–207. [Google Scholar]

- Shetti, B.V. 1988. Bronzes of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. In The Great Tradition. Indian Bronze Masterpieces. New Delhi: Brijbasi, pp. 70–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sompura, Kantilal F. 1968. The Structural Temples of Gujarat. Ahmedabad: Gujarat University. [Google Scholar]

- Sompura, Kantilal F. 1969. Buddhist Monuments and Sculptures in Gujarat-A Historical Survey. Hoshiarpur: Vishveshvaranand Institue. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2012. Selected Chapters from the Catuṣpīṭhatantra. Doctoral thesis, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2015. Early Works and Persons Related to the So-called Jñānapāda School. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 36: 537–62. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2016a. Some unknown/unedited fragments of Cakrasaṃvara literature. Paper presented at Conference ‘Transgression and Encounters with the Terrible in Buddhist and Śaiva Tantras’, Zurich, Switzerland, February 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2016b. A Brief Introduction to the “Amṛtasiddhi, ongoing critical edition by James Mallinson and Péter-Dániel Szántó”. Paper presented at Sanskrit Texts on Yoga, A Manuscript Workshop, London, UK, September 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. 2017. Tantric Buddhist Communities and Seeking Patronage at Medieval Indian Courts. Cambridge: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Szántó, Péter-Dániel. Forthcoming. Siddhas. In Brill’s Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Leiden: Brill.

- Templeman, David. 1983. The Seven Instruction Lineages by Jonang Tāranātha. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Templeman, David. 1995. The Origin of Tārā Tantra: Sgrol ma‘i Rgyud kyi Byung khung Gsal Bar Byed pa‘i lo Rgyus Gser gyi Phreng ba zhes Bya ba. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works and Archives. [Google Scholar]

- Templeman, David. 1997. Buddhaguptanātha: A Late Indian Siddha in Tibet. In Tibetan Studies. Proceedings of the 7th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Graz 1995. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, vol. II, pp. 955–65. [Google Scholar]

- Truschke, Audrey. 2018. The Power of the Islamic Sword in Narrating the Death of Indian Buddhism. History of Religions 57: 406–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, Giuseppe. 1931. The Sea and Land Travels of a Buddhist Sādhu in the Sixteenth Century. The Indian Historical Quarterly VII: 683–702. [Google Scholar]

- Tuladhar-Douglas, Will. 2006. Remaking Buddhism for Medieval Nepal: the fifteenth-century reformation of Newar Buddhism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Veluppillai, Alvapillai. 2013. Comments on the History of Research on Buddhism among Tamils. In Buddhism among Tamils in pre-colonial Tamilakam and Īlam. Uppsala: Uppsala Universiteit, vol. 3, pp. 58–101. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, Ramaswamy. 1990. A History of the Tamil Siddha Cult. Madurai: Ennes Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Verardi, Giovanni. 2011. Hardships and Downfall of Buddhism in India. Delhi: Manohar Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- White, David Gordon. 1996. The Alchemical Body. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yule, Henry, and Burnell Arthur Coke. 1903. A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursive, 2nd ed. London: J. Murray. [Google Scholar]

| 1. | I use the designation “Nāth” here even though it was not current during the period under consideration (and I do the same for “Hindu”). See (Mallinson 2011, p. 409) for a discussion of the usage of the term Nāth as the name of a grouping of yogi lineages. I use the vernacular form “Nāth” rather than the Sanskrit “Nātha” because it is in vernacular usage that the designation “Nāth” is most usually found. |

| 2. | (Dasgupta 1946, pp. 194–95) denies the possibility of Buddhist origins for the Nāths, partly on the spurious grounds that they were the first alchemists so must have existed before the Pātañjalayogaśāstra because of its mention (4.1) of auṣadhi, medicinal herbs, and thus long predated the esoteric forms of Buddhism with which they have much in common. In east India, Nepal and Tibet, continues Dasgupta, the Nāths’ traditions “got mixed up with those of the Buddhist Siddhācāryas”, a process which was facilitated by their common heritage of tantra and yoga. White (1996, pp. 106–9) suggests that Gorakṣanātha, the second of the human Nāth gurus, was originally Śaiva before being made out in later myths to be Buddhist, concluding that “since no extant tantric or Siddha alchemical works, either Hindu or Buddhist, emerged out of Bengal prior to the thirteenth century, we need not concern ourselves any further with the imagined east Indian Buddhist origins of Gorakhnāth or the Nāth Siddhas”. (White does not address the possibility of elements of Nāth tradition deriving from Buddhist traditions from other parts of India.) Briggs (1938, p. 151 n. 1) names the stages of development of Buddhism in Bengal as Mantrayāna, Vajrayāna and then Kālacakrayāna, and that “[t]hese Buddhist elements were absorbed into the Nāthamārga”. Sen (1956, pp. 281–86) writes of the Nāths’ “Buddhist affiliation” and states that “[b]oth the Nātha cult and Vajrayāna had fundamental unity in their esoteric or yogic aspects”, but makes no suggestion as to which of the two traditions came first. Templeman (1997, p. 957) talks of a “shared praxis” which persisted up to the seventeenth century. In contrast, the polymath writer, poet and scholar M.Govinda Pai, who was from the Tuḷu region (whose Kadri monastery is the focus of this article), says that “the Nātha cult is known to have developed itself out of the Vajrayāna system of the Mahāyāna Buddhism, and thus being in its origin a form of Tāntrik Buddhism before it transformed itself into Tāntrik Śaivism, it naturally betrays no less affinity with the Buddhistic than with the Brāhmanical Tantra” (Pai 1946, p. 64), and his compatriot P. Gururaja Bhatt, who wrote the definitive history of Tuḷunāḍu, concurs (Bhatt 1975, p. 291). Bouillier (2008, pp. 85–86) notes how early historians of the Tuḷu region affirmed that the site was Buddhist before it became Nāth, but that from the 1970s local historians have denied Buddhism’s primacy. Thus Bhatt (1975, pp. 370–72), despite asserting the Nāths’ Buddhist origins, will not entertain the possibility that Kadri was Buddhist before being Nāth and ties himself in various improbable knots trying to defend his position. |

| 3. | (Sanderson 1994, pp. 92–99). See also Sanderson 2001; (Sanderson 2009, pp. 124–20). For summaries of the different positions held in this debate, see (Acri 2015, pp. 263–65) and (Hatley 2016, pp. 37–38). |

| 4. | (Hatley 2016, p. 30), the findings of which article were subsequently refined by Hatley (2018, pp. 114–20) on consideration of tantric medical texts, leading him to conclude that “[f]inding potential intertextuality at the level of the Śaiva Gāruḍa- and Bhūtatantras, Buddhist Kriyātantras, and the early Vidyāpīṭha points toward what is likely to be a history of interaction, shared ritual paradigms, and textual appropriation extending back to the earliest strata of tantric literature”. |

| 5. | Seyfort Ruegg 2001; (Sferra 2003, p. 62). |

| 6. | Sanderson 1994, p. 92. |

| 7. | Birch 2011, pp. 535–36; Isaacson and Sferra (2014, pp. 100–1); Mallinson (forthcoming b). There is one occurrence of the term haṭhayoga in the c. 3rd century ce Bodhisattvabhūmi (p. 318 ll. 11–17), which is part of the Yogācārābhūmiśāstra. |

| 8. | |

| 9. | Birch (forthcoming). |

| 10. | There have been many Virūpākṣas other than Virūpākṣa the siddha: a Buddhist king known in early Pali sources (Malalasekera 1937 s.v. Virūpakkha; I thank Hartmut Buescher for this reference); one of four great kings of early Mahāyāna in the pre-5th century Suvarṇaprabhāsottama (6.1.1, 6.3.1, 6.6.25; I thank Gergely Hidas for this reference); a form of Rudra mentioned in the Skandapurāṇa (72.64 in the edition in preparation by Peter Bisschop et al.; I thank Professor Bisschop for this reference); one of eight yakṣas in the Śivadharma (pp. 193–208); a form of Śiva whose teachings are given in the c. 12th-century Virūpapañcāśikā; and a form of Śiva which is the central deity of Vijayanagara. Monier-Williams (s.v. virūpacakṣus) gives many more references. |

| 11. | See (Dowman 1985, pp. 43–52) and (Davidson 2005, pp. 49–54) for overviews of Virūpākṣa’s legends (which are first found in the c. 12th-century Grub thob brgyad bcu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus of Smon grub shes rab, which is translated in Grunwedel 1916; Robinson 1979 and Dowman 1985); and (Chattopadhyaya 1970, p. 404) for a list of works in Tibetan attributed to him. |

| 12. | A painting from the Drigung tradition which predates 1217 ce is perhaps the earliest Tibetan depiction of Virūpākṣa (Luczanits 2006, p. 82). |

| 13. | In the Grub thob brgyad bcu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus, Virūpa is said to have been born at Tripurā in East India and studied at the Somapurī vihāra, which is near Paharpur in Bangladesh (Robinson 1979, pp. 27–28). Tāranātha says that Virūpa lived in Mahrata, i.e., Maharashtra, that he visited Srisailam and that his disciple Kāla Virūpa practised in the Konkan (Templeman 1983, p. 18 and Chattopadhyaya 1970, p. 215). Both Smon grub shes rab and Tāranātha also tell a story of Virūpa destroying an icon of Śiva. The former names the destroyed Śiva as Maheśvara and locates his temple in the unidentified land of Indra (Robinson 1979, pp. 29–30); the latter names the Śiva Viśvanātha and locates his temple in Triliṅga, i.e., the present-day Telangana region (Templeman 1983, p. 15). As a result of a transmission whose details are unknown to me, current Tibetan legend (see e.g., http://www.ludingfoundation.~ org/Archive2016.html accessed 7 June 2018) accords with the c. 1280 ce Marathi Līḷācaritra in locating this episode at Bhīmeśvara, which is one of the three liṅgas referred to in the name of Triliṅga and whose temple complex at Draksharama houses a shrine to Virūpa; on the Līḷācaritra’s story, see footnote 13. |

| 14. | |

| 15. | One of the texts attributed to Virūpākṣa in the Vanaratna codex (on which see Isaacson 2008) is entitled Amarasiddhi. Cowell and Eggeling (1876, p. 28) report the name of the text as Amarasiddhiyantrakam but a transcription of the text kindly shared with me by Péter-Dániel Szántó shows that its name is Amarasiddhi (f.47 recto and verso). Chattopadhyaya (1970, p. 404) mentions an Amarasiddhivṛtti among Tibetan works attributed to Virūpākṣa. |

| 16. | Baker 2018, pp. 421–22. Schaeffer (2002, p. 527, n. 12) finds no connection between the Virūpākṣa of the Amṛtasiddhi and the Virūpākṣa of the lam ‘bras tradition, but in the Vanaratna codex described by Isaacson (2008), one of whose texts is, as noted above, an Amarasiddhi of Virūpākṣa, after the text of the Marmopadeśa there is a lineage of teachers which starts from Virūpākṣa and which Isaacson (2008, pp. 3–4) identifies as being very close to some of the lam ’bras lineages. |

| 17. | See e.g., Tucci 1931, p. 690. |

| 18. | Vīra Rājendra Coḍā, who flourished c. 1130 ce, is recorded as having made a donation to Bhīmeśvara at Drākṣārāma in an undated inscription (Epigraphia Indica Vol. IV, p. 51). |

| 19. | I am grateful to Amol Bankar for sharing with me these identifications of Virūpākṣa (personal communication 12 June 2018). Bankar identifies as Virūpākṣa the Dabhoi image, which is one of a group of twelve siddhas of whom some are clearly Nāths (Shah 1957), because, despite considerable damage to the sculpture, it is evident that he is accompanied by a woman and that there are images of the sun and moon above him. Both these motifs are suggestive of the legend of Virūpākṣa in which he stops the sun’s path through the sky so that a lady innkeeper will keep serving him and he will not have to pay his bill (see e.g., Robinson 1979, p. 29). A siddha depicted on the exterior of cave 14 at Panhale Kaji is sitting with a yogapaṭṭa in a posture common in Tibetan images of Virūpākṣa and is accompanied by a woman who may be pouring him a drink. Bankar’s identification as Virūpākṣa of an image of a siddha at Pimpri Dumal (reproduced in Sarde 2014, p. 6, fig. 10) is more tentative, being dependent upon the siddha, who is standing, being accompanied by an anthropomorphic image of Sūrya, the sun god, and pointing at the sky. |

| 20. | I thank Amol Bankar for informing me of the Kāmākhyā Virūpa image, which depicts the tavern episode summarised in footnote 19. |

| 21. | Caryāgīti 3 (Kvaerne 1977, pp. 81–86). I thank Lubomír Ondračka for informing me of this reference. |

| 22. | The middle Indic dohā verses of the Caryāgīti, as well as those of the Dohākośas attributed to the siddhas Saraha and Kāṇha, are usually said to be from east India but this is based on an unwarranted identification of their language as eastern Apabhraṃśa (Szántó forthcoming). |

| 23. | Varṇaratnākara, p. 57. |

| 24. | See footnote 13 and Navanāthacaritramu, p.135 which says that Virūpākṣa was the son of a Maratha king. |

| 25. | The Līḷācaritra was compiled between 1274 and 1287 ce but then lost and reconstructed in the early 14th century (Raeside 1982, p. 491). |

| 26. | Vikramārkacaritramu 6.4 (Jones 2018, p. 199, n. 7). |

| 27. | Tārārahasya, p. 69. |

| 28. | Līḷācaritra pūrvārdha 198–99, Ajñāta Līḷā 27. Elsewhere in the Līḷācaritra there are said to be four oḷīs or lineages of the Nāth tradition, vajroḷī, amaroḷī, siddhoḷī and divyoḷī, of which only the first two are extant in the Kali era (Līḷācaritra, uttarārdh 475). Vajraolī/vajrolī and amaraolī/amarolī are compounds of vajra and amara with olī, which Hemacandra says means kulaparivāṭī, i.e., “lineage” (Deśināmamālā 1.164b; I thank Alexis Sanderson for this reference, which is from the extensive commentary accompanying his forthcoming translation of Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka). The distinction between Vajra and Amara lineages, while here being broadly understandable as one between Buddhist and Śaiva traditions, may also reflect a distinction in practice between traditions which engage in sexual rituals (Vajrayāna Buddhists and Kaula Śaivas), and those which spurn such rituals in favour of a method of celibate yoga aimed at jīvanmukti (the Vajrayāna Amṛtasiddhi and the Śaiva Amaraughaprabodha). Ultimately the celibate yoga tradition of the Amaraughaprabodha came to dominate the Nāth saṃpradāya. |

| 29. | I thank Amol Bankar, who is editing the Tattvasāra, for providing me with this information. |

| 30. | Navanāthacaritramu, p. 135. |

| 31. | This part of the story is perhaps an echo of an episode in Tibetan treatments of Virūpākṣa in which he is rebuked by his fellow monks for eating pigeons, prompting him to abandon his monastery and then restore the pigeons to life (see e.g., Dowman 1985, pp. 44–46). |

| 32. | His disciples are named as Rasendrapāya, Ratnapāya, Uccaya, Kālapāya, Vajrakākanātha, Jālāndhra, Śaindrapāla (Jālāndhra’s student), Kāmaṇḍa, Pūrṇagirinātha, Endiyāṇiguru, Bhuvanendra and Trilocanasiddha (Navanāthacaritramu, pp. 211–14). |

| 33. | Vikramārkacaritramu 6.4 (Jones 2018, p. 199, n. 7). |

| 34. | Haṭhapradīpikā 1.9. |

| 35. | Both mīna and matsya mean fish. In Śaiva texts which predate the haṭha corpus, Mīnanātha and Matsyendra are one and the same (see e.g., Devīdvyardhaśatikā vv. 161c-163b and Ciñcinīmatasārasamuccaya 7.50 (I thank Alexis Sanderson for these references), in both of which Mīnanātha is given as the name of the propagator of the Kaula Pūrvāmnāya, who elsewhere is identified as Macchanda (Tantrāloka 1.7), Matsyendra (Kaulajñānanirṇaya 11.43) and Macchaghna (Kaulajñānanirṇaya chapter colophons)). Subsequent Tibetan and Indian siddha lists and depictions include two fish-related siddhas (e.g., Lūyipa and Mīnapa in the Grub thob brgyad cu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus, Matsyendra and Mīna in the Haṭhapradīpikā (1.5), and statuary in Maharashtra (Sarde 2017)). |

| 36. | Mīnanātha is invoked in the maṅgala verse of the long recension of the Amaraughaprabodha. The hemistich in which his name is given (after Ādinātha) is not found in the two manuscripts of the older, short recension, but is likely to have dropped out in the course of their transmission. Two siddhas are mentioned in the other hemistich, Cauraṅgi and Siddhabuddha. Their close association in legend with Matsyendra indicates that Mīnanātha here is another name for Matsyendra. |

| 37. | Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya chps. 48–53. |

| 38. | See footnote 13. |

| 39. | See footnote 19. |

| 40. | Virūpākṣa is included, together with Mañjunātha, in a list of 84 siddhas current at the Nāth headquarters in Gorakhpur: http://yogindr.blogspot.com/2014/03/chaurasi-siddhas.html. This is likely to be due to their inclusion in the list of nine Nāths in the Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya, which was edited under the auspices of the Nāth order in 1956. |

| 41. | Exceptions are tantric Buddhist images from the Himalayan region, the Caryāgīti, whose place of composition is uncertain, and the Maithili Varṇaratnākara. |

| 42. | Navanāthacaritramu 213 (the title is given as Amṛtajñasiddhi). By identifying Virūpākṣa as the author of the Amṛtasiddhi and locating his origins in present-day Maharashtra, the Navanāthacaritramu points to that region as the place of composition of the Amṛtasiddhi, an inference supported by parallels between the Amṛtasiddhi and the c. 12th- or 13th-century old Marathi Vivekadarpaṇa, whose teachings on the yogic body are similar to those of the Amṛtasiddhi (see e.g., Vivekadarpaṇa ch. 5 on the sun and moon) and which, like the Amṛtasiddhi, gives its chapters the unusual designations of viveka and lakṣaṇa. On the date of the Vivekadarpaṇa, see Reinelt 2000, pp. 93–95. |

| 43. | Navanāthacaritramu canto 1 (Jones 2018, pp. 185–86). |

| 44. | Navanāthacaritramu cantos 4–5 (Jones 2018, pp. 189–94). |

| 45. | |

| 46. | The Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya is a palimpsest of Buddhist, Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava teachings, reflecting the passing of the control of the Mañjunātha temple from Vajrayāna Buddhists to Nāth Śaivas and then Mādhva Vaiṣṇavas, with the latter responsible for its final redaction. For an overview of its contexts and context, see Nagaraju 1969. |

| 47. | Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya 14.9, 48.7, 50.11, 50.17, 53.27. The c. 15th-century Ānandakanda, which was composed at Srisailam, gives a list of nine Nāths whose fourth is Koṅkaṇeśvara and may correspond to Virūpākṣa (1.3.47a-48b):

|

| 48. | See (Schoterman 1975, pp. 934–35); (Sanderson 2011, pp. 44–45 and 2014, pp. 62–64), and (Mallinson 2011, pp. 412–14). The Śaiva tradition of the southern Nāths is Śāmbhava, a variant of the Paścimāmnāya (Kiss forthcoming). The oldest known statues of Nāths date from the 12th century ce onwards and are found in western India and the Deccan (Sarde 2017, pp. 96, 108–10). |

| 49. | Tantrāloka 29.32. |

| 50. | Kiss (forthcoming, p. 32) says that the Matsyendrasaṃhitā was “composed in South India, probably in the Tamil region, or alternatively, around Goa, in the 13th- century”. Kiss chooses the Tamil region over the Konkan because of the mention in the Matsyendrasaṃhitā of the god Śāstṛ, whom he identifies as a specifically Tamil deity, but the Kadri Mañjunāth temple has an image of Śāstṛ dated to the twelfth century and other, earlier images of Śāstṛ are found in the region (Bhatt 1975, pp. 354–55) and plates 290 and 291. Of the two toponyms mentioned in the Matsyendrasaṃhitā, the first, Gomanta, is likely to be in present-day Goa (Kiss forthcoming, pp. 30–31) while the location of the second, Alūra, whose king’s dead body was taken over by Matsyendra, is uncertain. Kiss gives various possible identifications of Alūra, including Ellora, Eluru in Andhra Pradesh and Vellore (Kiss forthcoming, p. 31). The five manuscripts of the Matsyendrasaṃhitā all have the reading alūrādhipatiṃ bhūpaṃ dākṣiṇātyaṃ purā kila (55.3ab). The text is likely to have been redacted in the early 19th century at the request of the Mahārāja of Jodhpur (Kiss forthcoming, p. 32); perhaps the original reading, obscure to north Indian scribes, was ālupādhipatiṃ, referring to a king of the Ālupa dynasty, which ruled the Tuḷu region from the early centuries ce until the end of the 14th century (Bhatt 1975, p. 18), and whose capital was at Mangalore from the 11th to 13th centuries, the likely period of composition of the Matsyendrasaṃhitā. In the Navanāthacaritramu, the king who plays the same rôle in the story of Matsyendra rules over Kadri, which at the time would have been under Ālupa rule. The Matsyendrasaṃhitā does not, however, mention Kadri in its version of the story of Gorakṣa rescuing Matsyendra. Supporting a Tamil origin for the Matsyendrasaṃhitā is its identification of Gorakṣa as a Coḷā king (paṭalas 1 and 55) and its naming at 55.20 of Matsyendra’s son and grandson as Kharparīśa and Vyālīndra, both of whom are associated with alchemy in various Tamil traditions but are not mentioned in texts associated with Kadri (or Srisailam). |

| 51. | Deshpande 1986. Panhale Kaji has various Nāth statues, including a group of 9 or perhaps 10 siddhas. A group of 12 Nāth siddhas, dating to 1230 ce, is found at Dabhoi near Ahmedabad in Gujarat. A statue of Matsyendra from the Kadri monastery and now in the Mangalore Government Museum has been dated to the 10th century, but, as will be explained below, this date is likely to be too early and was probably proposed for ideological reasons. |

| 52. | Bhatt 1975, p. 299 and plates 303 and 304(a). |

| 53. | I thank Manu Devadevan for sharing with me his transcription and translation of this inscription. Bouillier (2008, p. 96) reports that the inscription refers to Candranātha as a king (arasu) but Devadevan tells me that this is not the case. Bhatt (1975, p. 295) notes that an inscription from Mangalore dated 1434 ce mentions “the gift of land to one Jugādikuṇḍala Jōgi-Puruṣa by Jōgi-Oḍeya alias Chauṭa”. |

| 54. | Bhatt 1975, p. 294. |

| 55. | Badger 1863, pp. 111–13. |

| 56. | Grey 1892, pp. 345–52. |

| 57. | Tashrīh al-Aqvāṃ chp. 104 (British Library Board, Add.27255 f.399). I thank Bruce Wannell for translating this passage for me. |

| 58. | This migration is recorded in the Teyyam performances regularly put on by the Cōyī (the vernacular for yogī) caste in northern Kerala, in which it is precipitated by the death of the king’s son and the resultant ending of his lineage (Freeman 2006, pp. 167–69). |

| 59. | On the rājyābhiṣeka, see Bouillier 2008, chp. 6. |

| 60. | (Sastri 1939, pp. 104–5). On early traces of Buddhism in Karnataka see (Nagaraju 1983, pp. 6–10). |

| 61. | Acri 2016, p. 8. |

| 62. | (Szántó 2016b, p. 2). The exact location of Mahābimba is uncertain. I know of two further possible references to it. Tāranātha says that in Koṅkaṇa his guru Buddhaguptanātha saw “the self-created image of Mañjuśrī in the middle of a pond. It is called Jñānakāya... Then he saw also the bimbakāya which looks like a rainbow raising the stūpa of the accumulated vapour beyond touch” (Tucci 1931, p. 696). A manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā dated 1015 ce mentions a pilgrimage site in Koṅkaṇa called Mahāviśva, which Szántó (2012, Vol. 1/2 p. 40, fn. 61) suggests may be a corruption of Mahābimba. A puzzling verse in the long recension of the Amaraughaprabodha (67 in Jason Birch’s edition, from which the variant readings below are taken), which does not appear to fit its context and is also found, with significant variants, at Sekoddeśa 26, indicates that these two unusual compounds may refer to a single object, which lights up various heavenly bodies (including smoke (dhūma) and specks of dust (marīci), suggestive of the vapour reported by Tāranātha):

|

| 63. | Bhatt 1975, plate 298(a). A relief of the Buddha still in situ at Kadri has been dated to the ninth or tenth centuries (Bhatt 1975, plate 304(b)). |

| 64. | Szántó 2015, pp. 546 and 550–52. |

| 65. | Szántó 2015, p. 558. |

| 66. | Davidson 2002, p. 159. |

| 67. | Hevajratantra 1.6.16. |

| 68. | Cambridge University Library Add. 1643. |

| 69. | These are Lokanātha in Śrīkhairavaṇa, Sahasrabhuja Lokanātha in Śivapura, Lokanātha at Mahāviśva, Khaḍgacaitya in Kṛṣṇagiri (i.e., Kanheri), a caitya on Pratyekabuddha peak at Kṛṣṇagiri and a Lokanātha caitya at Marṇṇava (Kim 2014, pp. 42, 44, 66–68). |

| 70. | Epigraphia Carnatica VII Sk 170. |

| 71. | Epigraphia Carnatica VII Sk 169. |

| 72. | (Nagaraju 1983, pp. 12–13 and fig. 9), which draws on the 1941 Annual Report of the Mysore Archaeological Department but has a better picture of the statue. |

| 73. | Bhatt 1975, p. 373 and plate 304a (b). |

| 74. | Indian Antiquary X, pp. 185ff.; Annual Report on South Indian Epigraphy 1927–28, Appendix E, Nos. 65–66. |

| 75. | |

| 76. | Desai 1954, p. 91. |

| 77. | |

| 78. | Bhatt 1975, pp. 372–73. |

| 79. | Chattopadhyaya 1970, p. 325. |

| 80. | Templeman 1983, p. 56. |

| 81. | Templeman 1983, p. 60. |

| 82. | See (Templeman 1983, pp. 17–18) on Virūpa’s disciple Kāla Virūpa practising asceticism in the Konkan before returning to his guru in the Maratha region; (Templeman 1983, p. 81) on the siddha Nāgopa; (Templeman 1995, p. 5) on king Haribhadra, who mastered the siddhi of making magical pills; and (Chattopadhyaya 1970, p. 351) on Jñānākaragupta. |

| 83. | Templeman 1983, pp. 82–83. |

| 84. | Templeman 1983, p. 94. |

| 85. | (Yule and Burnell 1903, p. 28) s.v. Anchediva:

Anjediva was taken over by the Portuguese in 1505 (Mathew 1988, p. 163). The name of the island given by Tāranātha appears to be San Lorenzo, but the Portuguese church on Anjediva has always been known as Nossa Senhora das Brotas (Our Lady of the Springs) in homage to the island’s good supply of fresh water. San Lorenzo was a name for Madagascar, but that is by no means a “small island”, so it seems that either Tāranātha was again conflating his sources or he was, as suggested by Templeman (1997, p. 962, n. 38), referring to a Portuguese settlement by that name elsewhere in the Konkan. The only such reference I have found is to a church of San Lorenzo in Goa mentioned by della Valle in the early 17th century, but which was no longer standing in the 19th century (Grey 1892, p. 495). |

| 86. | Anjediva is now under the control of the Indian Navy and closed to visitors, including local Christians wanting to visit its two churches. I visited the neighbouring Kurumgad, another possible candidate for Tāranātha’s island, in March 2016, only to discover that it was covered in Portuguese fortifications dating to the beginning of the 16th century and to be told that all the other habitable islands in the vicinity were similarly fortified. |

| 87. | Tucci 1931, p. 692, n. 2. |

| 88. | The location of a thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara at a site called Śivapura in a 1025 ce manuscript of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (see p. 10) indicates another possible site of Vajrayāna-Śaiva interaction (I thank Andrea Acri for suggesting this in an email dated 24th January 2019). Bankar (2013) and Sarde (2016) describe early Buddhist sites in the Deccan which were later occupied by Nāths, but there is no evidence of Vajrayāna Buddhism at the sites, nor of direct links between the Buddhist and Nāth traditions. |

| 89. | Deshpande (1986, p. 121) dates the oldest caves at Panhale Kaji to before the 5th century, but Rees (forthcoming) has shown that a later date, probably in the latter half of the first millennium, is more likely. |

| 90. | See figure |

| 91. | Deshpande 1986, pp. 146–48. |

| 92. | On Kadri, see Bouillier 2008, chp. 4 and Bouillier 2009; also Saletore 1937; Pai 1946; (Bhatt 1975, pp. 287–97) and (Freeman 2006, pp. 164–67). |

| 93. | See South Indian Inscriptions Vol. VII No. 191, in which the transcription of the part of the inscription which gives its year reads thus:

As it stands this is an unlikely formulation which must correspond to the year 4069 (4000 + 68 + 1) of Kaliyuga, i.e., 967–68 ce, and this date has been repeated in most secondary literature on Kadri. Pai, however, without viewing the inscription itself, demonstrated that gate must be a misreading of śate (ga and śa are similar in the Grantha script in which the inscription is written), not only because śate is much better Sanskrit, but also because the tithi given only makes sense if the year is 1068 rather than 968 (Pai 1946, pp. 60–62). Dominic Goodall visited Kadri in 2017 and confirmed that the correct reading is śate (personal communication 6th February 2017). |

| 94. | Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya 13.10–11:

I do not know what image is being referred to as Viṣṇu here; it may no longer be at the site. |

| 95. | Alexis Sanderson first suggested this to me, in a meeting in December 2010. His identification was subsequently confirmed to me by Christian Luczanits (email communication 30 January 2018). |

| 96. | I thank Christian Luczanits for this identification (email communication 26 April 2016). |

| 97. | I thank Christian Luczanits (email communication 26 April 2016) and Andrea Acri (email communication 24 January 2019) for these observations. |

| 98. | Comparison of photographs of the image show that its composition has been altered in recent years, and confirm that the mūrti is not of one piece with the plinth. The photographs in the Government of Madras’s Annual Report for Epigraphy for the Year Ending 31 March 1921 (Plate 1), Bhatt (1975, plates 300 and 301) and Shetti (1988, fig. 10) show the prabhāvalī (halo) behind Mañjuvajra higher than it is today, and the image now has a metal sheet between it and the plinth. The sheet has small posts at its rear which support the prabhāvalī in its new position. In the oldest photograph Mañjuvajra holds a lotus flower in each of his middle left and right hands as he does today, while in the photographs found in Bhatt 1975 and Shetti 1988 the lotuses are not in Mañjuvajra’s hands but in those of his two attendants. |

| 99. | The image is identifiable as Matsyendra (whose name means “lord of fish”) because the subject is seated on a fish. |

| 100. | The Lokeśvara image has four arms and his other right hand may have held something, but is now empty. Matsyendra, being human-born, has only two arms. |

| 101. | |

| 102. | Grey 1892, p. 348. |

| 103. | Personal communication from Shreekant Jadhav 27th February 2019. |

| 104. | South Indian Inscriptions Vol. VII No. 189 (pp.84–85). |

| 105. | The head or Rājā of the monastery does play a role in the temple’s annual car festival (Nagaraju 1969, p. 68). |

| 106. | Photographs of the statues without their silver coverings are reproduced by Bhatt (1975, plates 303 and 304(a)). Cauraṅginātha (“Chowranginatha” on the label) is referred to as Śṛṅginātha by Bhatt (1975, p. 299). As noted by Bouillier (2008, p. 84), no source is known for the ascription of the names to these images. They now have full-length silver covers replicating, with embellishment, the iconography of the stone images, but at the base of the cover on the image said to be of Matsyendra is a fish which is not found on the image beneath. |

| 107. | Bhatt 1975, p. 299 and plates 303 and 304(a). |

| 108. | Bhatt 1975, p. 290, n. 1, p. 296, n. 27. The best known temple of Śiva Mañjunātha is at Dharmasthala, c. 50 kilometres inland from Mangalore. The Mañjunātha liṅga at Dharmasthala, which is of the usual iconic form unlike the simple svayambhū liṅga at Kadri, is said to be the original object of worship at Kadri Mañjunātha and to have been transported to Dharmasthala from Kadri in the 16th century by Vādirāja, the maṭhādhipati of the Mādhva maṭha at Udipi (Nagaraju 1969, p. 68). |

| 109. | Kandahjaya 2016, p. 88 and, n. 60, table p.91. The Vimalaprabhā commentary on the Kālacakratantra, whose teachings have some parallels with those of the Amṛtasiddhi, opens with an invocation to Mañjunātha. |

| 110. | See page 23. |

| 111. | |

| 112. | Loc. cit. |

| 113. | South Indian Inscriptions Vol. VII No. 189 (pp. 84–85) dated śaka 1308 prescribes materials for the worship of Śrīmañjinātha of Kadaḷi. No.190 (pp. 85–87) dated śaka 1311 is very hard to read, but mentions Mañjinātha and possibly the establishment of an image at the temple. I thank Manu Devadevan for sharing with me his transcriptions and translations of these Kannada inscriptions. |

| 114. | Grey 1892, p. 348. |

| 115. | Bouillier 2008, p. 96 and n. 42, citing a transcription by Ānandanāth Jogī. |

| 116. | The actual name Mangalore is not given; Gauraṇa writes of “a large city on the western shore rich in auspiciousness (maṅgalāvṛtam)”: poṃgāru paścimāṃbudhitīramunanu maṃgaḷāvṛtam agu mahanīyam aina puṭabhedanamu (Navanāthacaritramu, p.176). |

| 117. | The 55th and last paṭala of the Matsyendrasaṃhitā, which dates to perhaps the 13th century, tells a version of the story similar to that found in the Navanāthacaritramu (see Kiss forthcoming, p. 12 for a synopsis). Ondračka (2011) analyses medieval Bengali versions of the legend and Muñoz (2011, pp. 115–27) gives summaries and analysis of current north Indian versions. The Kaulajñānanirṇaya, which is ascribed to Matsyendra and is transmitted in a manuscript dated to the mid-11th-century on palaeographic grounds (nak ms. 3–362/ngmpp A48/13; I thank Shaman Hatley for the dating (personal communication 15th January 2018)), tells the story of Matsyendra overhearing Śiva teach Pārvatī the Kaula doctrine but not that of his sojourn at Kadri, suggesting that it predates the events on which the legend is likely to be based. |

| 118. | This is perhaps the Narendra Hill in Sawantwadi, southern Maharashtra. I thank Jason Birch for this suggestion. |

| 119. | |

| 120. | |

| 121. | Navanāthacaritramu, p.94. |

| 122. | I thank Jamal Jones for this observation (personal communication 23 March 2018). |

| 123. | (Sanderson 2005, pp. 135–36, n. 345) writes “[t]he term *Anuttarayogatantra that has long been current in academic writing on Tibetan Buddhism does not occur to my knowledge in any Sanskrit text but is an erroneous reconstruction from Tibetan rnal ’byor bla med kyi rgyud, which rather renders the Sanskrit yoganiruttaratantram”. It is noteworthy that unlike the Haṭhapradīpikā, which teaches royal (rāja) yoga and haṭha yoga, the Navanāthacaritramu uses the name anuturya rather than haṭha or a related term, perhaps because of haṭha’s negative connotations (on which see Mallinson forthcoming b). |

| 124. | See the forthcoming edition of the Amṛtasiddhi by Péter-Dániel Szántó and me for details. |

| 125. | Szántó 2015, p. 543. |

| 126. | See (Birch 2011, p. 535) and (Mallinson forthcoming b). |

| 127. | Amaraughaprabodha (short recension) verse 7. |

| 128. | p. 13. |

| 129. | On Mīnanātha and Matsyendranātha, see note 35. |

| 130. | The first half of the maṅgala verse, which mentions Ādinātha and Mīnanātha, is absent in the two manuscripts of the older recension of the Amaraughaprabodha. |

| 131. | Cauraṅgi does not occur in northern lists of the nine Nāths, but he is included in a list of 84 siddhas given in the early 14th-century Maithili Varṇaratnākara (p. 57), in which his name comes third, after Mīnanātha and Gorakṣaṇātha [sic]. His story was current in Bengal and Mithila (it is told in the Gorakh Vijay cycle) and is popular in Punjab, where he is known as Pūraṇ Bhagat (see e.g., White 1996, pp. 298–99). Cauraṅgi’s legend is also found in the Grub thob brgyad cu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus, a 12th-century Tibetan account of the lives of the 84 siddhas (the story is similar to that taught in the Navanāthacaritramu) and he is mentioned in the 13th-century Marathi Jñāneśvarī (pp. 1730–40). |

| 132. | The bulk of the Kadalīmañjunāthamāhātmya, chp. 15–45, is devoted to their exploits. |

| 133. | Haṭhapradīpikā 1.6. |

| 134. | |

| 135. | Jones 2018, p. 199, n. 7: siddhabuddhuni buddhicittaṃbunaṃ jerci. |

| 136. | Similarly, the Nāth presence at Panhale Kaji did not result in the destruction or removal of Buddhist statuary. |

| 137. | Thus Amaraughaprabodha (short recension) 35 is a reworking of Amṛtasiddhi 19.15, in which the Vajrayāna concept of the vicitrakṣaṇa, one of four kṣaṇas or “moments” associated with the four blisses experienced during sexual ritual, becomes vicitrakvaṇaka, “having variegated tones”, an epithet of the anāhata, “unstruck”, sound heard internally by the yogi. At vv. 38 and 40 of its short recension the Amaraughaprabodha retains the Amṛtasiddhi’s teachings on the Vajrayāna concepts of paramānanda and sahajānanda, and similarly, at vv. 39 and 40, those of atiśūnya and mahāśūnya. |

| 138. | See Bajracharya and Michaels 2016, pp. 5–51 for a translation of a legend explaining the identification of Avalokiteśvara and Matsyendra in the 1830 ce Nepālikabhūpavaṃśāvalī. Of particular note is that Lokeśvara became Matsyendra after overhearing the Kaulajñāna, the Kaula doctrine which is the subject of the Kaulajñānanirṇaya of Matsyendra (on which see footnote 117). See also Locke 1980, pp. 288–89 and chp. 13, and Tuladhar-Douglas 2006, pp. 181–82. |

| 139. | Bajracharya and Michaels 2016, pp. 69–72, Malla 2006, pp. 4–9. Cf. Michaels 1985 and Lévi 1905, pp. 218–21, 353 (in the latter reference, Lévi names Bengal, Malabar and Sri Lanka as possible sources for the Nepalese Matsyendra cult). |

| 140. | The 15th-century Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha identifes Avalokiteśvara and Matsyendra (Tuladhar-Douglas 2006, p. 7). Arguing against claims of an earlier identification is the absence of mentions of Matsyendra, Gorakṣa or Lokeśvara in the late 14th-century Gopālarājavaṃśāvalī. |

| 141. | On the former, see Verardi 2011; on the latter as a recurrent historical trope, see Truschke 2018. |

| 142. | Desai 1954, pp. 91–92. |

| 143. | See footnote 13. |

| 144. | Nityāhnikatilaka f.16v3-f.18r5, for an edition of which by Alexis Sanderson, see https://www.academia.\protect\discretionary{\char\hyphenchar\font}{}{}edu/35397806/Mallinson$_$Harvard$_$Talk$_Nov_$2017$_$Handout. |

| 145. | On which see p. 13. |

| 146. | Līḷācaritra pūrvārdha 198–99, A.27. I thank Amol Bankar for this reference and for sharing with me his translation of the relevant passage. |

| 147. | I thank Alexis Sanderson for this reference, which is from a draft of his forthcoming commentary on the Tantrāloka. |

| 148. | Ṣaṭsāhasrasaṃhitā ff. 351v-353r, for an edition of which by Alexis Sanderson and me, see https:\protect\discretionary{\char\hyphenchar\font}{}{}//www.\protect\discretionary{\char\hyphenchar\font}{}{}academia.\protect\discretionary{\char\hyphenchar\font}{}{}edu/35397806/Mallinson$_$Harvard$_$Talk$_$Nov$_$2017_Handout. The instruction takes place at Arbuda, i.e., Mount Abu. There are no material remains at Abu from the period under consideration which indicate either a Buddhist or Nāth presence, but there is material evidence for both traditions at Taranga, a site 70 kilometres due south of Abu best known for its magnificent 13th-century Jain Ajītnāth temple. On the opposite side of the Siddhaśilā hill at Taranga from the Ajītnāth temple is a small temple complex with two shrines containing images now worshipped as Hindu goddesses called Dhāraṇ Mātā and Tāraṇ Mātā. Dhāraṇ Mātā is flanked by six slightly smaller sculptures. The priests at the shrine dress her in the attire of a goddess, but she and the others are all male figures whose iconography indicates that they are Buddhist, with some dating to perhaps the 6th century (I thank Ken Ishikawa for this tentative dating). Tāraṇ Mātā is a beautiful female image who has been identified as Kurukullā (Sompura 1969, pp. 29–30); see also (Sompura 1968, p. 72) and (Rawat 2009), but is in fact the Buddhist goddess Tārā, as can be inferred from her retinue (I thank Christian Luczanits for this identification (personal communication 21st June 2017)). On the hill itself is a cave, known locally as jogan dā guphā, “the cave of the yogis”, which has a small makeshift shrine centred on a freestanding panel depicting in relief four Buddhist images of seated meditating figures. On the top of the hill is a small temple from perhaps the 19th-century (I thank Crispin Branfoot for confirming my tentative dating), which now houses the pādukā of a Jain saint but has eight statues of Nāth yogis on its roof, suggesting that it was originally a Nāth shrine. Tāranātha mentions a yoginī disciple of Śāntigupta (his guru’s guru) called Tāraṅgā, who travelled widely, including to the Konkan (Templeman 1983, p. 93). |

| 149. | E.g. Matsyendra, who is mentioned in the early 11th-century Tantrāloka as the propounder of the Śaiva Kaula doctrine in the kali age (1.7, 29.32 and 30.102), or Virūpa, who is Buddhist in early sources such as the Grub thob brgyad cu rtsa bzhi’i lo rgyus and the Līḷācaritra. |

| 150. | E.g. Gorakṣa, whose earliest textual mentions, which date to the 13th century, are found in both Śaiva and Buddhist texts (Mallinson 2014, p. 233, n. 28). |

| 151. | Thus for Schaeffer, the first scholar to study closely the Amṛtasiddhi, it “cannot be comfortably classified as either Buddhist or non-Buddhist” (2002, p. 515). |

| 152. | See (Szántó 2017, pp. 7–8) on the Gāhaḍāvala Jayacandra, and the Nityakaumudī (ngmpp b35–26 and nak 4/324), which is a commentary on the Śaiva Vīracandra’s 1072 ce Nityaprakāśa whose colophon says that it was commissioned by the Pāla monarch Rāmapāla’s guru, Śambhudatta. I thank Péter-Dániel Szántó for this reference. |

| 153. | (Gokhale 1990, p. 70); see ibid., p. 10 for more on connections between Kanheri and Gauḍa. |

| 154. | See footnote 50. |

| 155. | Matsyendrasaṃhitā paṭalas 1 and 55. |

| 156. | The Tirumantiram mentions the Kālacakra[tantra] (Tirumantiram “III chp.14”; see (Venkatraman 1990, p. 193) for this reference, which I have been unable to confirm). The Kālacakratantra may be dated to between 1025 and 1040 ce (Newman 1998). The Tirumantiram is cited in a commentary on the Yāpparuṅgalakkārigai by Guṇasāgara, who was active c. 1100 (Venkatraman 1990, p. 193). A text-critical study of the Tirumantiram remains a desideratum; if the text as it is currently constituted does not contain additions to its earliest layer, it may thus be dated to the second half of the 11th century ce. (On the implausibility of the very early datings of the Tirumantiram often found in secondary sources, see Goodall 1998, p. xxxvii, n. 85 and Goodall 2004, pp. xxix-xxx.) |

| 157. | The Tirumantiram makes no mention of the Nāth tradition but its doctrinal parallels with the Matsyendrasaṃhitā lead Kiss (forthcoming, pp. 51–52) to conclude that the two texts are “not completely unrelated”. The Tirumantiram’s yoga method has much in common with that of the Amṛtasiddhi, but, like the haṭhayoga of other Vajrayāna texts and in contrast with the celibate yoga of the Amṛtasiddhi, includes sexual intercourse without ejaculation. (In the sexual ritual taught in paṭala 40 of the Matsyendrasaṃhitā the yogi is to ejaculate.) The Tirumantiram mentions the Buddhist Kālacakratantra (see note 156) and celebrates the Śaiva site of Chidambaram, which is also a cultic centre for the Keralan caste yogis who moved south from Kadri in perhaps the 17th century (Freeman 2006, pp. 172–73). |

| 158. | The Kadri Lokeśvara, for example, resembles a Coḷā Śiva sold by Christies in New York in 2015: https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/a-large-bronze-figure-of-shiva-south-5875978-details.aspx |

| 159. | |

| 160. | Kandahjaya (2016, p. 160) notes that the Śāriputra has been variously dated to between the 5th to 15th centuries. Its mention of Matsyendra indicates that it was composed in the latter few centuries of this period. Paranavitana (1928, pp. 60–62) edits the verses describing Avalokiteśvara thus:

Avalokiteśvara/Nātha is identified with eight Nāthas in the Śāriputra: Śiva Nātha, Brahma Nātha, Viṣṇunātha, Gaurī Nātha, Matsyendra Nātha, Bhadra Nātha, Bauddha Nātha and Gaṇa Nātha (ibid.). Additionally, Avalokiteśvara’s role as the protector of mariners in Sri Lanka (Bopearachchi 2014, p. 182), is echoed by Matsyendra’s identification as a fisherman in many of the various legends associated with him. |

| 161. | Jayabhadra gives his place of birth in his (Szántó 2016a, p. 2). |

| 162. | See (Scheurleer 2008, p. 292, n. 21). I thank Andrea Acri for drawing my attention to this statue (personal communication 24th January 2019). |

| 163. | (Veluppillai 2013, pp. 65–77); see also (Acri 2018, p. 13). |

| 164. | |

| 165. | Jaini 1980; see also (Bouillier 2008, p. 112). |

| 166. | See (Bisschop 2018, p. 396) on Avalokiteśvara as a Buddhist Īśvara in the pre-630 ce Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mallinson, J. Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India. Religions 2019, 10, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040273

Mallinson J. Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India. Religions. 2019; 10(4):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040273

Chicago/Turabian StyleMallinson, James. 2019. "Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India" Religions 10, no. 4: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040273

APA StyleMallinson, J. (2019). Kālavañcana in the Konkan: How a Vajrayāna Haṭhayoga Tradition Cheated Buddhism’s Death in India. Religions, 10(4), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10040273