Abstract

This study examines depression among Latter-day Saint teens, particularly how religiosity and the parent–child relationship are associated with depressive symptomology. Although there is an abundance of research on adolescent depression and on adolescent religiosity, there is less research addressing the connection between the two. The research questions include: Does religiosity among Latter-day Saint teens reduce their rates of depression? What aspects of religiosity affect depression most significantly? How does religious coping influence depression? How does the parent–child relationship affect depression rates among Latter-day Saint teens? Being a sexual minority and living in Utah were related to higher levels of depression. Greater depression was also associated with more anxiety and poorer physical health. Authoritative parenting by fathers was associated with lower depression for daughters but not sons. Finally, feeling abandoned by God was related to higher depression, while peer support at church was associated with lower depression.

Research documents a decline in Christian religious affiliation and participation among Americans over the past several decades. Of the silent generation (those born between 1928 and 1945), 85% identified as “Christian” in their religious beliefs. However, of the younger millennial generation (those born between 1990 and 1996), only 56% are affiliated with a Christian religion in the United States (Cooperman et al. 2015). Other researchers have noted a “clear decline in outward religious expression” among young adults (Uecker et al. 2007, p. 1667), and an overall decline in religious participation in adolescents as they move through the teenage years.

One study reported that 43% of eighth graders attended church services regularly, as compared to 33% of twelfth graders (Smith et al. 2002). Another prevalent trend is that more teens and adults are identifying as “nones”—a term suggesting no religious affiliation. In the early 1980s, more than 90% of high school seniors identified with one religious group or another. Only 10% chose “none” as their religious affiliation. However, in 2016, 31% identified religiously as a “none” (Twenge 2017).

Despite these trends, religion still appears to be a significant force in the lives of many American teens and is linked to many positive outcomes. For example, studies have found that religious affiliation and participation are inversely related to juvenile drug, alcohol, and tobacco use, as well as a host of other externalizing or delinquent behaviors (Smith 2003). Adolescents who report higher levels of personal and familial religiosity appear to have greater self-esteem and healthier psychological functioning (Ball et al. 2003). Other studies show that religiosity is negatively related to suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and actual suicide (Donahue and Benson 1995). Studies have also shown an inverse relationship between religious participation, teenage sexual activity, and pregnancy (Lammers et al. 2000; Whitehead et al. 2001). Adolescent religious participation has been positively associated with physical health (Jessor et al. 1998), family cohesion (Varon and Riley 1999), effective coping (Shortz and Worthington 1994), and academic achievement (Muller and Ellison 2001; Regnerus 2000).

With fewer adolescents participating in religious activities and society becoming more culturally secular, will religion continue to have similar influences in the lives of those involved today—especially in light of what appears to be an increase in mental health challenges, such as anxiety and depression? Furthermore, less is known about the specific aspects of religiosity that may relate to mental health and how these variables might interact with family processes to influence adolescent mental health. We will examine the interaction between four variables: parenting style, religiosity, gender, and mental health. The purpose of the present study was to examine what aspects of their faith and family relate to their mental health within a cohort of Latter-day Saint teens. Although Latter-day Saint adolescents have not drawn the attention of many researchers, they have been called the “spiritual athletes” of their generation because of their spiritual sacrifices, devotion, and energy towards their faith (Dean 2010). These qualities may add further nuance towards the outcomes of the study.

1. Literature Review

A recent study reported that between 2005 and 2014, the prevalence of major depressive episodes among adolescents increased from 8.7% to 11.3% (Mojtabai et al. 2017). The prevalence of depression among adolescents ranged from 5% to 15% and affects one in five people before adulthood (Dew et al. 2010). Other experts have estimated that among high school teens, up to 30% have reported episodes of depression (Arntzen 2017). Furthermore, there appears to be a gender gap associated with major depressive disorder (MDD) in adolescents. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) revealed that 19.5% of adolescent girls but only 5.8% of adolescent boys reported a major depressive episode in 2015 (Bose et al. 2016; see also Lewinsohn et al. 1998).

Because of the deleterious effect of depression on adolescent well-being, it is important we further understand what may increase or mitigate depression. Teenage depression is associated with low academic success and poor psychosocial development (Birmaher et al. 1996). Birmaher et al. (1996) also reported that 70% of youth who experience depression might eventually develop major depressive disorder. These trends become even more concerning when contemplating the possible long-term consequences. Most mental health disorders in adulthood are preceded by an internalizing disorder in adolescence (Pine et al. 1998). If a method exists to prevent or decrease adolescent depression, it may also act as a preventative measure for adult depression. In 1993, the United States spent USD $44 billion on adult depression; working to prevent depression among youth may be more cost effective in the long run and alleviate much suffering (Lewinsohn et al. 1998). This necessitates a better understanding of adolescent depression.

1.1. Correlates of Adolescent Depression

Distinguishing between cause from effect in psychology is often difficult. Diego et al. (2001) identified commonalities between depressed teens. Many spent less time doing homework, had fewer friends, felt lonely, exercised less, had suicidal thoughts, and used marijuana or cocaine. In addition, Diego et al. (2001) also found that very few of these teens had positive relationships with their parents.

Lewinsohn et al. (1998), found that almost half of depressed teens have another mental health disorder and teens who smoked were twice as likely to have depression at some point. This study also identified a prototypical case of depression: a 16-year old female with low self-esteem/poor body image, low feelings of self-worth, pessimistic, overly dependent on others, feels that she is receiving little support from her family, and is coping poorly with both major and minor stressors (such as conflicts with parents, physical illness, poor school performance, and relationship breakups). Birmaher’s findings are congruent: 60–70% of adolescents had experienced one or more “severe” stressful life event(s) in the year prior to the onset of the MDD, including loss, divorce, bereavement, and exposure to suicide (1996).

In terms of biological factors, adult twin and adoption studies have shown that genetic factors may account for at least 50% of the variance in the transmission of mood disorders (Birmaher et al. 1996). Other twin studies have reported the positive relationship between heritability and depression (Pinheiro et al. 2018). A meta-analysis documented the “familial” factor with the onset of depression and concluded that this mood disorder is often influenced by genetic influences (Sullivan et al. 2000).

Additionally, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) found that depression is more prevalent among females who have a family history of depression (Niarchou et al. 2015). One study documented that depression in boys increased by 21% between 2012 and 2015; however, during that same period, depression in girls increased by 50% (Twenge 2017). There are also environmental factors that can influence adolescent depression. One study reported that females who reported low emotional closeness to their parents were 2.3 times more likely to report higher depressive symptoms than those who reported a higher emotional connection. The same study reported that female adolescents are more susceptible to stressors that do not affect males as much (Lewis et al. 2015).

Girgus and Yang (2015) explored gender differences in depression from a developmental perspective. There appears to be few gender differences in younger children—the prevalence of depression being about equal. Beginning in early adolescence; however, rates of female depression begin to increase. By late adolescence, girls are nearly twice as likely as teenage boys to be depressed. One theory that may explain this difference is that females ruminate and coruminate (discuss problems with other people) more than males. Another theory postulates that there are three common ways to react to a negative situation: to ruminate, problem-solve, or engage in distracting behaviors. Boys are supposedly more likely to engage in two of the latter, and therefore have lower rates of depression by later adolescence than girls (Girgus and Yang 2015). It is also possible that depression is equally prevalent among men and women; however, men do not disclose it. Psychiatric drugs are also prescribed more often to women than men (Studd and Morgan 1992).

1.2. Parenting Effects on Depression and Effects of Depression on Parenting

Children are more likely to experience depression if they perceive interactions between their parents and themselves as uncaring, unsupportive, and negative (Diego et al. 2001). In turn, when children are depressed, they often have less in-depth or lengthy communication with their mothers and view their parents as more critical, angry, or sad (Chiariello and Orvaschel 1995). Betts et al. (2009) found that parents who were over-protective with low levels of nurturing, unavailable caregivers, cold, controlling and intrusive were more likely to have depressed children. Lack of nurturance and the lack of parental encouragement of autonomy created an insecure bond between the parent and child, resulting in the adolescent often having low self-confidence and difficulty in establishing trusting and supportive relationships. Such insecurity led to learned helplessness (Betts et al. 2009). Irons and Gilbert (2005) agreed that insecure attachment had negative implications—that children either felt socially inferior or compensated with competition.

Studies have shown that parental depression can have an impact on adolescent depression. Depressed mothers have been found to exercise excessive authority, control, criticism, disapproval, insufficient parental care, nurturance, and support (Chiariello and Orvaschel 1995). Approximately 15 million adolescents in the United States reside with a parent who suffers from depression. These teens are at three to four times greater risk for depression than the general population (Compas et al. 2015). Additional findings in children of depressed mothers included delay in acquiring self-regulation strategies, lower scores on measures of mental and motor development, more school problems, less social competence, lower levels of self-esteem, and higher levels of behavioral problems (Goodman and Gotlib 1999).

1.3. Religiosity and Adolescent Depression

Multiple studies have examined the relationship between depression and religion (Sanders et al. 2015; Stearns et al. 2018; Yonker et al. 2012). For example, individuals who struggle with personal religiosity—whether that includes feelings of abandonment by God, loss of faith, trials, or viewing themselves as unworthy—were shown to have poorer mental health outcomes (Rippentrop et al. 2005). Another study found that religion is positively associated with mental health in adolescents and is a significant predictor of lower levels of depression (Sanders et al. 2015). Similarly, Stearns et al. (2018) found that individuals who reported high levels of religiosity also reported lower levels of depression. Results of a meta-analysis indicated that spirituality and religiosity has a positive effect on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults (Yonker et al. 2012). Further, attending religious services has been found to be a protective factor against suicide (Anderson et al. 2015).

There are many potential reasons religious adolescents generally fare so well, especially when it comes to depressive symptoms. They are often affiliated with a strong, positive support network, including peers and adults. Their religious doctrines may provide a means to manage stress and maintain a positive outlook on life (Cotton et al. 2006). Further, religious beliefs could provide a means for problem solving and coping. Religion also often inspires adolescents to set goals and to look towards the future optimistically (Cotton et al. 2005). Wright and co-authors found that spirituality and the role of religious beliefs in an adolescent’s interactions in life were directly associated with lower levels of depression (Wright et al. 1993). Pearce et al. (2003) reported that if adolescents considered themselves spiritual, and have had positive religious experiences, they reported lower levels of depression. Religion appears to provide adolescents with a framework to navigate difficult circumstances, to interpret difficult experiences more positively, and to have adults and peers as a built-in support system (Pearce et al. 2003).

Anderson et al. (2015) suggested that spirituality should be incorporated in more clinical interventions. Despite lower levels of religiosity among clinicians, many clients in psychotherapy use religious beliefs to cope and want to discuss spirituality (Anderson et al. 2015). The positive effects of religion extend beyond Christianity. A study of patients receiving hemodialysis in Jordan discovered that the more religious Muslims were, the less likely they reported depressive symptoms (Musa et al. 2018). Researchers found that spiritual wellness practices such as fasting, prayer, fostering positive relationships, expressing beliefs through art, and studying religious materials served as protective factors against depression.

However, certain religious beliefs have been associated with distress. For example, those who believed that suffering is caused by a non-benevolent God struggled more with the divine and, in turn, experienced lower levels of well-being and higher levels of distress (Wilt et al. 2016). Studies have highlighted the negative mental health effects that are caused when one feels abandonment by God. These feelings about God may be influenced by the parent-child relationship. A study conducted by Exline et al. (2013) found that how a child views their parent has a large influence on the child’s feelings of abandonment by God. The more the child views their parents as cruel, the more they felt abandoned by God and saw God as cruel. These feelings were then related to feelings of anger towards the divine. Another study found that those who experienced sexual abuse growing up also experienced feelings of being abandoned by God. For these victims, the feeling of abandonment brought out anger and increased doubt in God and his promises (Rudolfsson and Tidefors 2014). Other studies among various religious groups have established the strong relationship between depression and negative religious coping such as feeling abandoned by God. (Braam et al. 2010).

1.4. Possible Construct Interaction

The extant literature clearly shows a relationship between religiosity, parenting style, gender and depression. Based on Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner 1999), we theorized that there were likely interactions between these well-established correlates to depression. Bronfenbrenner’s theory focuses on how proximal processes (i.e., direct, reciprocal, enduring, increasingly complex interactions) become the driving force behind developmental changes in adolescence. Proximal processes are the first of four interrelated aspects of the process–person–context–time (PPCT) model for understanding how adolescents internalize influences (Bronfenbrenner 1995). Family religiosity and parenting practices are examples of a proximal process which likely influences the development of children. However, in Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory, that influence will likely differ based on person-level constructs such as gender, temperament, and even biological issues. Each of these processes and person-level characteristics are also contained within a specific context such as a family or a religious community. Finally, the impact of these constructs likely varies over time. Rather than examining each construct independently, the bioecological model encourages researchers to examine the processes, person-level characteristics, contexts, and time variables of interest simultaneously. One way to do this is to look for interactions between the constructs already known to influence depression.

1.5. Latter-Day Saint Youth as an Important Understudied Sample

Although there has been a significant amount of research dedicated to how religious participation affects internalizing and externalizing behaviors of protestant adolescents, fewer studies have examined Latter-day Saint (LDS) teens. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a total church membership of 16,118,169—presently there are 6.6 million Latter-day Saints in the United States (Mormon Newsroom 2018).

In July 2002, Christian Smith and his team of researchers began the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), a national, random digit-dial telephone survey. Findings indicated that activity rates and outcomes for LDS youth (also known as Mormons) generally compared favorably to other religious youth. For example, 40% of all youth surveyed attend church services at least weekly compared to 71% of LDS youth (Smith and Denton 2005, p. 37). LDS youth also appeared strongly motivated by their religion. When asked, “Would you attend Church if it were totally up to you?” Almost 70% of LDS youth responded “Yes” to that query, with 47% of Protestant youth, and 40% of Catholic teens responding in the same manner (Smith and Denton 2005, p. 37). Smith and Denton summarized their research on LDS youth stating, “when belief and ‘social outcomes’ are measured, ‘Mormon kids tend to be on top’” (Dean 2010, p. 47). In addition, Kenda Creasy Dean, a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary summarized, “Mormon teenagers tend to be the ‘spiritual athletes’ of their generation, conditioning for an eternal goal with an intensity that requires sacrifice, discipline, and energy” (Dean 2010, p. 51).

However, these LDS youth are still susceptible to the problems and challenges common to adolescents. Indeed, Utah (a state that has over 50% Latter-day Saints) has a higher than national rate of teen suicide, which has increased substantially over the last decade, leading many to examine what factors in Utah may exacerbate or ameliorate mental health problems (Annor et al. 2017). The purpose of this study is to examine the prevalence of depression among Latter-day Saint teens and how religiosity and the parent–child relationships are associated with depressive symptomology. This study focuses on the following specific research questions: Does religiosity among Latter-day Saint teens reduce their rates of depression? If so, what aspects of religiosity affect depression most significantly? For example, we hypothesize that the more daily spiritual experiences an individual has, the less depressed they will be. Moreover, we hypothesize that positive religious coping, peer and leader support at Church, and family religious practices will protect and insulate adolescents from depressive symptoms.

We also examined how religiosity and parenting may combine as they relate to teen depression. As referenced earlier, when parents are harsh, teens may develop a negative, punitive view of God. Combined with family religious activities, it may be that harsh parenting has an even greater negative effect given that harshness is associated with religious activities and, hence, the teen may develop even more negative views of God. We therefore examined whether the relationship between family religious practices and depression is moderated by parenting style.

Given gender differences in rates of depression and religiosity, it may influence how parenting and religion are associated with depression. We therefore examined gender as a moderator in our analyses.

2. Methods

2.1. Measures

For each scale we employed confirmatory factor analysis to create a factor score for use in analyses. By using factor scores rather than summing or averaging the items in a scale, measurement error is reduced. We calculated reliability of factor scores using Rakov’s maximal reliability method (MR; Raykov 2012).

Depression. Teen depression was assessed using the 10-item self-report Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children—10 (CES-D—10; Bjorck et al. 2010). Participants respond by rating the degree to which they have experienced each item in the past week (e.g., “I felt lonely”, “I felt depressed”), with a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“a lot”). The MR for this scale was excellent, at 0.99

Daily Spiritual Experiences. A subscale of the National Institute on Aging/Fetzer Religion and Spirituality Scale (Idler et al. 2003; Underwood and Teresi 2002) was used to examine the regularity with which teens felt some connection with God/spirituality with response categories being 1 = “never or almost never” to 6 = “many times a day”. Items include “I feel God’s love for me” and “I feel guided by God.” The MR for this scale was 0.97.

Positive Religious Coping and Abandonment by God. Both positive and negative religious coping were measured using the religious coping scale of Pargament et al. (2011). For positive coping, participants were asked to think of how they deal with problems in their life and then asked the degree to which they used various strategies to cope (e.g., “Sought God’s love and care”, and “Looked for a stronger connection with God”). Responses range from 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“a great deal”). The MR for this scale was 0.96.

For negative coping, participants were asked how often they did things that indicated tension, conflict, and struggle with the sacred (e.g., “Questioned God’s love for me”, “Wondered whether God had abandoned me”). We conceptualized this construct as “Abandonment by God.” A question regarding church support within this scale was omitted to keep this scale conceptually distinct from the separate church support scale (see below). The MR for this scale was 0.97.

Parenting Style. Parenting behaviors and styles of parenting were measured using the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire—Short Version (PSDQ; Robinson et al. 2001). Children reported on both parents, and the parent reported on their own parenting, as well as the parenting of the other parent. Thus, there are two reports for each parent, one from a child and one from a parent. Responses are on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of the respective parenting styles and/or specific dimension of parenting behavior.

The authoritative subscale is 15 items and includes question such as “My parent is responsive to my feelings” and “My parent takes my desires into account”. The authoritarian subscale is 12 items and includes question such as “My parent explodes in anger toward me” and “My parent scolds and criticizes to make me improve.” Items were rephrased when parents responded about themselves or about the other parent. The MR was good (0.96 and above) for all reports of authoritative and authoritarian parents.

Private religious practices. Six items from the work of Smith and Denton (2005) were used to measure private religious practices. These include question about private prayer, meditation, scripture reading, listening to various types of religious media, and fasting. Responses ranged from 1 (“not in the past year”) to 9 (“more than once a day”). The MR for this scale was acceptable at 0.75.

Support at church. Two scales were used to measure support at church, one regarding the support of peers at church and the other regarding support from church leaders. These come from the Multi-Faith Religious Support Scale (Bjorck et al. 2017). Items included “I am valued by other teens [religious leaders] in my religious group” and “Other teens [leaders] in my religious group care about my life and situation.” Responses ranged from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). The MR for both of these scales was 0.98.

Controls. Several controls were added to the model including the child’s age, their gender (1 = female, 0 = male), whether they lived in Utah or Arizona, their physical health (rated on a five-point scale from “poor” to “excellent”), family income, race (1 = white, 0 = other), and whether the parents were married (1 = married, 0 = not married). Sexual orientation was also included. Less than 2% identified as gay or lesbian, with 3% responding they were “questioning” their gender. This variable was dichotomized with 1 = heterosexual, 0 = other (heterosexual, n = 764; not heterosexual, n = 32). Parent depression was also controlled. The CES-D—10 was also used for parents and had good reliability (MR = 0.99). Finally, to get a more direct measure of depression, we controlled for child anxiety which was measured with the six-item Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (Spence 1998).

2.2. Sample

Participants were taken from Wave 2 of the Family Foundations of Youth Development project, a longitudinal study of families with adolescents. This project has a strong emphasis on adolescent faith and mental health development with detailed scales on numerous related issues such as internalizing and externalizing problems and pro-social behaviors and beliefs. The project also has extensive scales examining family processes and influences. Data for the second wave were collected from Utah and Arizona (the first wave included only families in Utah). Families were recruited using the InfoUSA national database which contains over 80 million households across the United States. Contact information was obtained for households with children between the ages of 12 and 16. To recruit, potential participants were sent letters with follow-up phone calls. One teen and one parent filled out the survey, with the teen being compensated USD $30 and the parent compensated USD $40. For the current study, we selected only LDS youth for a total n of 796 with 251 in Arizona and 545 in Utah. Mean age of teens was 14.21 (SD = 1.09) with a range from 11 to 17. The majority of children in the study came from homes with two married biological parents (93%). Ninety-one percent of the sample identified as white, with the other 9% split between Hispanic, “mixed,” Asian, Black, and “other.” Median yearly household income was relatively high at USD $100,000. The lower 15% of the parents made less than USD $60,000 a year and the higher 15% of the parents made above USD $150,000. Forty-six percent of the teens were male. The vast majority had married parents (97%). Paternal data were imputed for those who did not report they had a father. While this imputation may seem counterintuitive, allowing those who did not have a father to remain in the sample allows the analyses to be more representative, particularly as we can control for having a father or not. However, the analyses are substantively identical when excluding those who did not have fathers. The only difference is that the interaction between being female and family religious practices becomes significant when fitting the model excluding those without fathers (n = 11; it was very close to significance prior to the 11 being removed). However, because the three-way interaction is present, this is only interpretable in context of the three-way interaction. Prototypical plots for females (estimated at +/– 1 standard deviation from the mean) revealed no significant differences in depression for females across family religiosity. Thus, whether we remove or retain the 11 teens without fathers, the results are substantively identical.

3. Analysis Plan

Analyses were conducted in the program Stata 15 (StataCorp 2018). Missing data were minimal (0 to 3.6%) and a single imputation was conducted using the Stata procedure ICE to produce a complete dataset for analysis (Royston 2005). Regarding missing data, the only restriction was that the youth had to indicate they were currently a Latter-day Saint. With minimal amount of missingness, we used single imputation to impute missing values.

A regression was constructed with teen depression as the dependent variable with family, religious, and control variables specified as independent variables. After the initial regression model, a series of models were tested to examine whether the relationship between the independent variables and depression varied by child gender. This was done with Stata’s ibn. prefix on gender which, for each independent variable, gave the value of its relationship to depressions separately for males and females. An interaction was considered if, for males or females, the relationship between the independent variable and depression was significant for one gender but not both. We also examined whether the relationship between family religious practices and depression was moderated by parenting style. Finally, we examined whether this differed by child gender. That is, we examined whether the interaction between parenting style and religiosity differed by child gender. When a control variable was not significantly related to the depression at p < 0.10, it was dropped for the sake of parsimony and power.

4. Results

Correlations. In Table 1, all independent variables and controls were significantly related to depression except for parents’ perceptions of their authoritarian parenting and the teen’s race.

Table 1.

Correlations and descriptives (n = 796).

Regression models.Table 2 contains final model results. Significant relationships not moderated by child gender included peer support at church (B(SE) = −0.09(0.03), p < 0.001) and abandonment by God (B(SE) = 0.18(0.02), p < 0.001). These relationships were in the hypothesized direction such that greater peer church support was related to less depression and greater abandonment by God was related to more depression. Significant controls were teen anxiety (B(SE) = 0.21(.02), p < 0.001), being from Utah (B(SE) = 0.05(0.02), p < 0.01), teens’ physical health (B(SE) = −0.03(0.01), p < 0.001), and the teen being heterosexual (B(SE) = −0.08(0.04), p < 0.05). Parent income, marital status, and teen race were not related to depression at p < 0.10 and were therefore dropped from the model.

Table 2.

Predicting teen depression (n = 796).

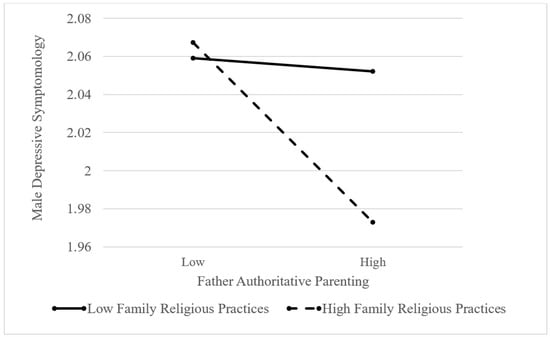

Several effects were moderated by gender. These included females experiencing less depression when they reported their father was more authoritative (B(SE) = −0.05(0.02), p < 0.01) and males reporting more depression the more private religious practices they engaged in (B(SE) = 0.02(0.01), p < 0.05). There was also a three-way interaction between gender, parent report of authoritative parenting by the father, and family religious practices. That is, the two-way interaction between authoritative parenting by the father and family religious practices is significant for males (B(SE) = −0.03(0.03), p < 0.05) but not for females. A graph of this interaction was produced (see Figure 1). In this interaction, estimated depression does not appear associated with family religious practices when father authoritative parenting is low (i.e., at low authoritative parenting, there is almost no difference in depression whether the family religious practices were high or low). In contrast, when father authoritative parenting is high, depression is substantially less when family religious practices are also high. In other words, the combination of an authoritative father and high family religious (religiosity) was related to lower levels of teen depression.

Figure 1.

Interaction between paternal authoritative parenting and family religious practices for male teens.

5. Discussion

This study examined the relationship between family, faith, and depression in a sample of Latter-day Saint adolescents and identified factors indicative of greater depression. This enables us to better identify those who may be at greatest risk for depressive symptoms. Furthermore, this study also illuminates how faith and family may interact in their association with risk. This goes beyond simply controlling for faith or family factors, but rather employs a more comprehensive conceptualization by examining whether the impact of family and faith may, in part, be dependent on one another.

For basic demographics, youth in Utah reported higher depression compared to adolescents in Arizona. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services cite two studies of adolescent depression in both states with conflicting findings. A 2018 study measured depression with a single question that asked how often youth felt sad or hopeless. In this study, Utah adolescents appeared to experience less depression (33% of Utah adolescents experienced depressive symptoms compared to 36% of Arizona youth; both groups however had higher values than the United States average of 31%). However, a 2017 study that measured adolescent depression found Utah adolescents experienced more depression than Arizona adolescents, 14% to 12%, with the United States average being 13% (Arizona Adolescent Mental Health Facts 2018). The measure used to assess depression in the current study from the CES-D−10 more closely aligned with the measure used in the 2017 study mentioned above, which also had Utah adolescents experiencing higher levels of depression. Since there are more LDS youth in Utah than Arizona, it could be argued that something about the LDS faith is driving the slightly higher depression rates in Utah. However, the fact that LDS youth in Arizona have lower levels of depression than LDS youth in Utah raises the possibility that there are other personal-level, or contextual influences besides the LDS faith that are driving the higher Utah depression rates. Our measures do not provide enough detail to know for sure. One possible contributing factor might be elevation. Higher altitude has been associated with a higher suicide rate (Betz et al. 2011; Brenner et al. 2011) with some suggesting greater depression as a possible mechanism (Gamboa et al. 2011). Indeed, in examining the counties from which the sample was primarily drawn, the Utah counties have between three and seven times the elevation of the Arizona counties.

The National Alliance on Mental Health states that LGBTQ youth experience almost three times more mental health conditions than heterosexual youth (LGBTQ/NAM, 2019). Other national and international studies have found similar outcomes (Mustanski et al. 2010; Shenkman and Shmotkin 2011). Studies have found that these negative outcomes stem from several causes including prejudice and stigma, higher levels of substance abuse, higher suicidality, and even disparities in care (Russell and Fish 2016).

In addition, and not surprisingly, depression was associated with greater anxiety and physical health problems. Further, as has been found in other research (e.g., Petterson et al. 2017), those who identified as heterosexual reported lower levels of depression than those identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or questioning.

Regarding religiosity, two aspects had main effects on depression: abandonment by God and support at church from teens. Previous research has found that individuals who perceive God has abandoned them often report depressive symptoms (Rippentrop et al. 2005; Dew et al. 2010) and that church support is related to fewer depressive symptoms (Nooney and Woodrum 2002). Interestingly, these are both relational constructs. That is, when teens feel cared about by God and/or their peers at church, their depression is lower. This may indicate that, for depression, a key protective factor within religion is whether the individual’s religious experiences facilitate connections with the divine and with others. This fits well with Bronfenbrenner’s theory that: “The developmental power of proximal processes (in this case religious practices) are substantially enhanced when they occur within the context of a relationship between persons who have developed a strong emotional attachment to each other” (Bronfenbrenner 2000, p. 130). Thus, if adolescents feel disconnected from a close relationship with their family or God, they may be more susceptible to depression. Given the current study uses cross-sectional data we cannot determine whether individuals who are depressed distance themselves (and/or perceive more distance) from God and peers or whether poor connections with God and peers increases depression. Likely the relationship between religious connections and depression is transactional, with each affecting the other. In any case, given they are at increased risk for depressive symptomology, it would be important for church organizations to identify those lower on these connections and attempt to foster those connections for their members.

Contrary to hypotheses, positive religious coping was not significantly related to depression. It may be that more nuanced measures of coping are needed. There are other types of coping that we did not examine. For example, Pargament et al. (2001) developed a model that looked at three religious coping styles: self-directed coping, collaborative coping, and deferring coping. These three styles of coping may relate to depression. In one study on adolescent religious coping, the researchers found that the collaborative religious coping style served as a protective factor against negative mental health outcomes (Molock et al. 2006). Therefore, for religious adolescents, encouraging a collaborative relationship with God can minimize the effects of negative mental health outcomes. Although there has been a significant amount of research in the areas of adolescents, religious coping, and serious medical conditions, more research will need to be conducted in the arena of religious coping and mental health.

Regarding parenting, paternal authoritative parenting was associated with lower depression in daughters but not sons, indicating a differential impact of the person-level construct of gender—both the gender of the parent and the gender of the child. Other research has found unique effects of paternal involvement on the psychological wellbeing of daughters (e.g., Flouri and Buchanan 2003), though without longitudinal data it is unclear whether this is a father effect (the father’s authoritative parenting reducing daughter’s depression), a daughter effect (fathers being more authoritative towards daughters who are less depressed), or whether there is a third explanation. Whatever the explanation, a father’s less authoritative behaviors may be a signal of greater mental difficulties for their daughter(s).

The significant three-way interaction between gender, family religious practices, and paternal authoritative parenting is suggestive of the conditions under which family and faith may exert a more pronounced influence. In this instance, when either family religious practices (a proximal process) or paternal authoritative parenting (both a process and a context) were low, neither one appeared related to depression. That is, depression was essentially the same across levels of authoritative fathering when family religious practices were low. Further, when paternal authoritative parenting was low, there was no significant difference in depression across levels of family religious practices. However, when both paternal authoritative parenting and religious practices were high, there was an associated lower level of depression. It is possible that regular family religious practices provide a forum in which the positive parenting can occur. This connects with Bronfenbrenner’s theory that “to be effective, the interaction must occur on a fairly regular basis over extended periods of time” (Bronfenbrenner 1999, p. 5).

Family religious practices may provide a regular and enduring context for authoritative parenting to have an effect. Why this would be the case only for male children is not entirely clear given, as noted earlier, fathering has typically been related more strongly to daughters’ mental wellbeing than sons’. It is possible, as suggested by our findings, that paternal authoritative behaviors exert more of an influence on sons when in combination with other positive family practices, whereas for daughters the effect ranges across a variety of family contexts.

Although there are many studies that suggest religion can be a positive influence on physical and mental health, religion can also exacerbate problems (see Pruyser 1977; Pargament et al. 2001). Research from this study reveals that sometimes, religion can be detrimental to an individual’s well-being. For example, religiosity has been found to discourage individuals from seeking mental health help (Blank et al. 2002).

6. Conclusions

This study confirms findings from prior research in several areas. Being a sexual minority and experiencing higher levels of anxiety were associated with greater depression. Contrary to hypotheses, church leader support, positive religious coping, and daily spiritual experiences were unrelated to depression. Religion and spirituality were not uniformly associated with lower depression as many studies have found. For this sample, peer church support was associated with lower depression but feeling abandoned by God was related to higher levels of depression. There was also evidence that fathers’ authoritative parenting has a main effect on depression for daughters. Further, father authoritative parenting interacted with family religious practices predicting adolescent depression for sons. That is, if both authoritative parenting and family religious practices were high, depression levels were low in sons. However, if both were not high, neither was related to depression levels in a significant way.

7. Limitations

The sample used in the current study is homogenous, being primarily White and all LDS. Furthermore, 92% of our sample represented intact families, with a mother and father present in the home. In order for our findings to be generalizable, in the future, our participants in the study will need to be more diverse. Further, as mentioned, this study is unable to examine the direction of effects. It may be that the effects flow from depression to the family and religious variables. Still, the study does identify factors that can help identify teens that may be at most risk for depression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.O., M.A.G., & W.J.D.; Methodology, W.J.D. and M.A.G.; Formal Analysis, W.J.D.; Resources, M.D.O., M.A.G., and W.J.D.; Data Curation, W.J.D.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.D.O., M.A.G., C.K., B.W.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.D.O., M.A.G., C.K., B.W.M.; Supervision, M.D.O.; Project Administration, M.D.O., W.J.D.; Funding Acquisition, W.J.D., M.D.O., M.A.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, Naomi, Suzanne Heywood-Everett, Najma Siddiqi, Judy Wright, Jodi Meredith, and Dean McMillian. 2015. Faith-adapted psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 176: 183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annor, Francis, Amanda Wilkinson, and Marissa Zwald. 2017. Epi-Aid # 2017–2019: Undetermined Risk Factors for Suicide among Youth Aged 10–17 Years—Utah, 2017; Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Arizona Adolescent Mental Health Facts. 2018. Text, HHS.gov. Available online: https://hhs.gov/oah/facts-and-stats/national-and-state-data-sheets/adolescent-mental-health-fact-sheets/arizona/index.html (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Arntzen, Elsie. 2017. 2017 Montana Youth Risk Behavior Survey 14. Available online: http://opi.mt.gov/portals/182/page%20files/yrbs/17mt_yrbs_fullreport.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Ball, Joanna, Lisa Armistead, and Barbara-Jeanne Austin. 2003. The relationship between religiosity and adjustment among African-American, female, urban adolescents. Journal of Adolescence 26: 431–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, Jennifer, Eleonora Gullone, and Janice Allen. 2009. An examination of emotion regulation, temperament, and parenting style as potential predictors of adolescent depression risk status: A correlational study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 27: 473–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, Marian E., Morgan A. Valley, Steven R. Lowenstein, Holly Hedegaard, Deborah Thomas, Lorann Stallones, and Benjamin Honigman. 2011. Elevated suicide rates at high altitude: Sociodemographic and health issues may be to blame. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 41: 562–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birmaher, Boris, Neal Ryan, Douglas Williamson, David Brent, Joan Kaufman, Ronald Dahl, James Perel, and Beverly Nelson. 1996. Childhood and adolescent depression: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35: 1427–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorck, Jeffrey, Robert Braese, Joseph Tadie, and David Gililland. 2010. The Adolescent Religious Coping Scale: Development, validation, and cross-validation. Journal of Child and Family Studies 19: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorck, Jeffrey, Grace Kim, Dawna Cunha, and Robert Braese. 2017. Assessing religious support in Christian adolescents: Initial validation of the Multi-Faith Religious Support Scale-Adolescent (MFRSS-A). In Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, Advance Online Publication. No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, Michael, Marcus Mahmood, Jeanne Fox, and Thomas Guterbock. 2002. Alternative mental health services: The role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health 92: 1668–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, Jonaki, Sara Hedden, Rachel Lipari, and Eunice Park-Lee. 2016. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from 2015 National Survey of Drug Use and Health; North Bethesda: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Braam, Arjan, Agnes Schrier, Wilco Tuinebreijer, Aartjan Beekman, Jack Dekker, and Matty De Wit. 2010. Religious coping and depression in multicultural Amsterdam: A comparison between native Dutch citizens and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese/Antillean migrants. Journal of Affective Disorders 125: 269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, Barry, David Cheng, Sunday Clark, and Carlos A. Camargo Jr. 2011. Positive association between altitude and suicide in 2584 U.S. counties. High Altitude Medicine & Biology 12: 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1995. Developmental ecology through space and time: A future perspective. In Examining Lives in Context: Perspectives on the Ecology of Human Development. Edited by Phillis Moen, Glenn H. Elder and Kurt Luscher. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 619–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1999. Environments in developmental perspective: Theoretical and operational models. In Measuring Environment Across the Life Span: Emerging Methods and Concepts. Edited by Sarah L. Friedman and Theodore D. Wachs. Washington: American Psychological Association, pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 2000. Ecological systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology. Edited by Alan E. Kazdin and Alan E. Kazdin. Washington and New York: American Psychological Association Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 129–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chiariello, Mary, and Helen Orvaschel. 1995. Patterns of parent-child communication: Relationship to depression. Clinical Psychology Review 15: 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, Bruce, Rex Forehand, Jennifer Thigpen, Emily Hardcastle, Emily Garai, Laura McKee, and Sonya Sterba. 2015. Efficacy and moderators of a family group cognitive–behavioral preventive intervention for children of parents with depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 83: 541–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperman, Alan, Gregory Smith, and Katherine Ritchey. 2015. America’s Changing Religious Landscape. Washington: Pew Research Center, vol. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton, Sian, Elizabeth Larkin, Andrea Hoopes, Barbara Cromer, and Susan Rosenthal. 2005. The impact of adolescent spirituality on depressive symptoms and health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Heath 36: 529e7–529e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, Sian, Kathy Zebracki, Susan Rosenthal, Joel Tsevat, and Dennis Drotar. 2006. Religion, spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: A review. Journal of Adolescent Health 38: 472–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Kenda C. 2010. Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers is Telling the American Church. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dew, Rachel, Stephanie S. Daniel, David B. Goldston, William V. McCall, Margatha N. Kuchibhatla, Charlie Schleifer, Mary F. Triplett, and Harold G. Koenig. 2010. A prospective study of religion/spirituality and depressive symptoms among adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 120: 149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, Miguel, Christopher Sanders, and Tiffany Field. 2001. Adolescent depression and risk factors. Adolescence 36: 491–98. [Google Scholar]

- Donahue, Michael, and Peter L. Benson. 1995. Religion and the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Social Issues 51: 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exline, Julie J., Stephanie J. Homolka, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2013. Negative views of parents and struggles with God: An exploration of two mediators. Journal of Psychology and Theology 41: 200–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouri, Eirini, and Ann Buchanan. 2003. The role of father involvement in children’s later mental health. Journal of Adolescence 26: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, Jorge L., Ricardo Caceda, and Alberto Arregui. 2011. Is depression the link between suicide and high altitude? High Altitude Medicine & Biology 12: 403–4. [Google Scholar]

- Girgus, Joan, and Kaite Yang. 2015. Gender and Depression. Current Opinion in Psychology 4: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, Sherryl, and Ian Gotlib. 1999. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review 106: 458–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, Elen, Marc Musick, Christopher Ellison, Linda George, Neal Krause, Marcia Ory, and David Williams. 2003. Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research: Conceptual background and findings from the 1998 General Social Survey. Research on Aging 25: 327–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irons, Chris, and Paul Gilbert. 2005. Evolved mechanisms in adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms: the role of the attachment and social rank systems. Journal of Adolescence 28: 325–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessor, Richard, Mark Turbin, and Frances Costa. 1998. Risk and protection in successful outcomes among disadvantaged adolescents. Applied Developmental Science 2: 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, Cristina, Marjorie Ireland, Michael Resnick, and Robert Blum. 2000. Influences on adolescents’ decision to postpone onset of sexual intercourse: A survival analysis of virginity among youths aged 13–18 years. Journal of Adolescent Health 26: 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn, Peter, Paul Rohde, and John Seely. 1998. Major depressive disorder in older adolescents: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review 18: 765–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Andrew, Peter Kremer, Kim Douglas, John W. Toumborou, Mohajer A. Hameed, George C. Patton, and Joanne Williams. 2015. Gender differences in adolescent depression: Differential female susceptibility to stressors affecting family functioning. Australian Journal of Psychology 67: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtabai, Ramin, Mark Olfson, and Beth Han. 2017. National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics 138: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molock, Sherry, Rupa Puri, Samantha Matlin, and Crystal Barksdale. 2006. Relationship between religious coping and suicidal behaviors among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology 32: 366–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormon Newsroom. 2018. LDS Statistics and Church Facts | Total Church Membership. Available online: https://www.mormonnewsroom.org/facts-and-statistics (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- Muller, Chandra, and Christopher Ellison. 2001. Religious involvement, social capital, and adolescents’ academic progress: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of 1988. Sociological Focus 341: 55–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, Ahmad, David Pevalin, and Murad Al Khalaileh. 2018. Spiritual well-being, depression, and stress among hemodialysis patients in Jordan. Journal of Holistic Nursing 36: 354–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustanski, Brian, Robert Garofalo, and Erin Emerson. 2010. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health 100: 2426–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niarchou, Maria, Stanley Zammit, and Glyn Lewis. 2015. The Avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC) birth cohort as a resource for studying psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A summary of findings for depression and psychosis. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology 50: 1017–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nooney, Jennifer, and Eric Woodrum. 2002. Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 359–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Nalini Tarakeshwar, Christopher Ellison, and Keith Wulff. 2001. Religious coping among the Religious: The Relationships between Religious Coping and Well-being in a National sample of Presbyterian Clergy, Elders, and Members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Margaret Feuilleand, and Donna Burdzy. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Michelle, Todd Little, and John Perez. 2003. Religiousness and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Adolescent Psychology 32: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petterson, Lanna, Doug VanderLaan, Tonje Persson, and Paul Vasey. 2017. The relationship between indicators of depression and anxiety and sexual orientation in Canadian women. Archives of Sexual Behavior 40: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, Daniel, Patricia Cohen, Diana Gurley, Judith Brook, and Yuju Ma. 1998. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 55: 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, Marina, Jose Morosoli, Lucia Colodro-Conde, Paulo Ferreira, and Juan Ordoñana. 2018. Genetic and environmental influences to low back pain and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A population-based twin study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 105: 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruyser, Paul W. 1977. The seamy side of current religious beliefs. Bulletin of the Menniger Clinic 41: 329–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, Tenko. 2012. Scale construction and development using structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. Edited by Rick H. Hoyle. New York: Guilford, pp. 472–92. [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus, Mark. 2000. Shaping schooling success: Religious socialization and educational outcomes in urban public schools. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 39: 363–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippentrop, Elizabeth, Elizabeth Altmaier, Joseph Chen, Ernest Found, and Valerie Keffala. 2005. The relationship between religion/spirituality and the physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain 116: 311–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Clyde, Barbara Mandleco, Susan Olsen, and Craig Hart. 2001. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSQD). In Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques. Edited by John Touliatos, Barry F. Perlmutter and George W. Holden. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 3, pp. 319–21. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, Patrick. 2005. Multiple imputation of missing values: Update. Stata Journal 5: 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolfsson, Lisa, and Inga Tidefors. 2014. I have cried to him a thousand times, but it makes no difference: Sexual abuse, faith, and images of God. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 910–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Stephen, and Jessica Fish. 2016. Mental health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 12: 465–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Peter, Kawika Allen, Lane Fischer, Morgan Richards, David Potts, and Richard Potts. 2015. Intrinsic religiousness and spirituality as predictors of mental health and positive psychological functioning in Latter-day Saint adolescents and young adults. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 871–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenkman, Geva, and Dov Shmotkin. 2011. Mental health among Israeli homosexual adolescents and young adults. Journal of Homosexuality, Suicide, Mental Health, and Youth Development 58: 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortz, Joianne, and Everett Worthington. 1994. Young adults’ recall of religiosity, attributions, and coping in parental divorce. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33: 172–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian. 2003. Theorizing religious effects among American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, and Melinda Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian, Melinda Denton, Robert Faris, and Mark Regnerus. 2002. Mapping American adolescent religious participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Susan H. 1998. A measure of anxiety symptoms among children. Behaviour Research and Therapy 36: 545–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. 2018. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15.1. College Station: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, Melanie, Danielle Nadorff, Ethan Lantz, and Ian McKay. 2018. Religiosity and depressive symptoms in older adults compared to younger adults: Moderation by age. Journal of Affective Disorders 238: 522–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studd, John, and Jaquelinem Morgan. 1992. Gender and depression. The Lancet 340: 8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Patrick, Michael C. Neale, and Kenneth S. Kendler. 2000. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: Review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry 157: 1552–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean. 2017. IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—And Completely Unprepared for Adulthood (122–123). New York: Atria Books. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker, Jeremy E., Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. Vaaler. 2007. Losing my religion: The social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Social Forces 85: 1667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, Lynn G., and Jeanne A. Teresi. 2002. The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varon, Stuart R., and Anne W. Riley. 1999. Relationship between maternal church attendance and adolescent mental health and social functioning. Psychiatric Services 50: 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, Barbara D., Brian Wilcox, and Sharon Rostosky. 2001. Keeping the Faith: The Role of Religious and Faith Communities in Preventing Teen Pregnancy. Washington: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Wilt, Joshua A., Julie J. Exline, Joshua B. Grubbs, Crystal L. Park, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2016. God’s role in suffering: Theodicies, divine struggle, and mental health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 352–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Loyd S., Christopher J. Frost, and Stephen J. Wisecarver. 1993. Church attendance, meaningfulness of religion, and depressive symptomology among adolescents. Journal of Youth Adolescence 22: 559–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, Julie E., Chelsea A. Schnabelrauch, and Laura G. DeHaan. 2012. The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence 35: 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).