Abstract

In this paper, I explain the problem of the dreamer in the Zhuangzi. I aim to show that no difference exists between dreaming states and waking states because we have a fluctual relationship with these two stages. In both, “we are dreaming.” Put another way, from a psychoanalytical point of view, one stage penetrates the other and vice versa. The difference between dreaming and non-dreaming disappears because dreaming is a structural process. Also, from a psychoanalytical perspective, all confirmations and negations about dreams and non-dreams leads to one point: the being, or rather the becoming, of the subject. How does this solve the problem of the True Person/True Human Being (zhenren真人)? Does such a person have dreams or not? Does the True Person sleep without dreams, as we find in the Zhuangzi? From a psychoanalytic perspective, this is not possible. To prove this, I will present few passages from the Zhuangzi and offer a psychoanalytic explanation of them based on Jacques Lacan’s theory of the fantasy and desire.

1. Introduction

When we begin to think about dreams, certain questions arise: How much of imaginative perception, of dreams, can the experience of the subject take in? How much of one’s identity or authenticity remains once the subject turns back upon its dreams? How far does our “I” emerge in dreams? To what extent are dreams properties of ourselves and belong to us? How do we define the Dream?1 Do dreams have meanings at all? Are they coincidental images, or rather are they meaningful projections with their own traces?2 Dreams, as psychical phenomena, are products of the mind, and are a form of thinking. As Sigmund Freud pointed out, “The dream as a whole is a distorted substitute for something else, something unconscious,” (Freud 2015, p. 89). The dream is the guardian of sleep, providing a disguised satisfaction for wishes that are repressed while we are awake. The interpretation of dreams is the road that leads us to knowledge of the unconscious in psychic life (Freud 2010).

According to the French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, who is also called the French Freud, each person is refracted through processes of fantasy, desires, and dreams. No experience exists that is free from these notions. Psychoanalytic discourse shows that fantasy, desires, and dreams are deeply and strongly intertwined with the social domain, with the relationship between self and society, between conscious and unconsciousness, and finally between our identity and society. In this paper, by analyzing passages from the Zhuangzi,3 I would like to show that this process and this relation is unavoidable also for the True Person or True Human Being (zhenren 真人) described in the Zhuangzi.

2. The Dreamer and Their Identity

In a dream, we experience the illusion of logic. Though everything proceeds according to a plan of narration, this is a delusion. From a psychoanalytical point of view, in a dream, repetitive patterns emerge, and because of them we experience the illusion of a continual narration. However, this chain is actually dashed with intervals from one repetition to the next. Simply speaking, in a dream, we articulate our unconscious desires. To explain this process, let us look closer at the fragment from Chapter II of the Zhuangzi. It is a part of discussion between Ju Quezi and Chang Wuzi:

How, then, do I know that delighting in life is not a delusion? How do I know that in hating death I am not like an orphan who left home in youth and no longer knows the way back? Lady Li was a daughter of the border guard of Ai. When she was first captured and brought to Qin, she wept until tears drenched her collar. But when she got to the palace, sharing the king’s luxurious bed and feasting on the finest meats, she regretted her tears. How do I know that the dead don’t regret the way they used to cling to life? ‘If you dream of drinking wine, in the morning you will weep. If you dream of weeping, in the morning you will go hunting.’ While dreaming you don’t know it’s a dream. You might even interpret a dream in your dream—and then you wake up and realize it was all a dream. Perhaps a great awakening would reveal all of this to be a vast dream. And yet, fools imagine they are already awake—how clearly and certainly they understand it all! This one is a lord, they decide, that one is a shepherd—what prejudice! Confucius and you are both dreaming! And when I say you’re dreaming, I’m dreaming too.(Ziporyn 2009, p. 19)

Commonly, we consider the relationship between dreaming and non-dreaming in this way. Sleep is connected with states in which we are not thinking, whereas wakefulness is connected with rational thought. Both are presented as opposites. The problem emerges when we start to think about both of these linked states in that way, we cannot distinguish between what is a dream and what is not. The passage from Chapter II shows that everything is an illusion. We cannot be sure of what is a dream and what is not. This is correlated with one of the fundamental issues in the Zhuangzi’s thought, namely, the Transformation of Things (hua化). In this sense, we can say that dream becomes non-dream, and non-dream becomes dream. Everything is fluctual and unstable. Because of the Transformation of things, the movement from one state to another is smooth.4 In this passage, we find the claim that the difference between reality and sleeping states disappears. If this is true, we can assume that the dream is not only a mental image arising within a dream, but also is a kind of projection in reality. For Jacques Lacan, in reality (the non-sleeping state), which, in his theory, is called a symbolic state, that kind of projection takes form of fantasy.5 Our position in the dream is that of someone who does not see.

In the field of the dream (…) what characterizes the images is that it shows. (…) Look up some description of a dream, any one (…)—place it in its co-ordinates, and you will see that this it shows is well to the fore. So much is it to the fore, with the characteristics in which it is co-ordinated—namely, the absence of horizon, the enclosure, of that which is contemplated in the waking state, and, also, the character of emergence, of contrast, of stain, of its images, the intensification of their colours. (…) The person does not see where it is leading, he follows.(Lacan 1979, p. 75)

This means that we do not look at the image from our conscious position. Rather, the image shows itself:

But the very image that the subject makes present through his behavior and that is constantly reproduced in it, is ignored by him, in both senses of the word: he does not know that things image explains what he repeats in his behavior, whether he considers it to be his own or not; and he refuses to realize (meconait) the importance of this image when he evokes the memory it represents.(Lacan 2007, p. 68)

For Lacan, beyond all images that appear in dreams and in reality, there is always one fundamental fantasy that is unconscious. He recognizes the power of the image in fantasy, but this is not because of any intrinsic quality of the image in itself, but rather is because of the place it occupies in the symbolic structure. (For Lacan, symbolic structure is the reality when we are awake.) To explain this on the basis of the fragment from Chapter II of the Zhuangzi, we have to subvert the order in the sentences: I weep, and in a dream I’m dreaming about drinking wine. I go to hunting, and in a dream I’m weeping. Behind what the subject does and that about which he dreams is a hidden, unconscious desire, which in reality can never be fulfilled. The fantasy protects us from realizing the impossibility of the desire. Of course, the whole passage from Chapter II, tells us that no difference exists between dreaming and non-dreaming or between life and death, but from a psychoanalytic perspective, it also tells us something about the becoming and identification. For Jacques Lacan, the key term for the relationship between the dream, identity, and reality is the desire.

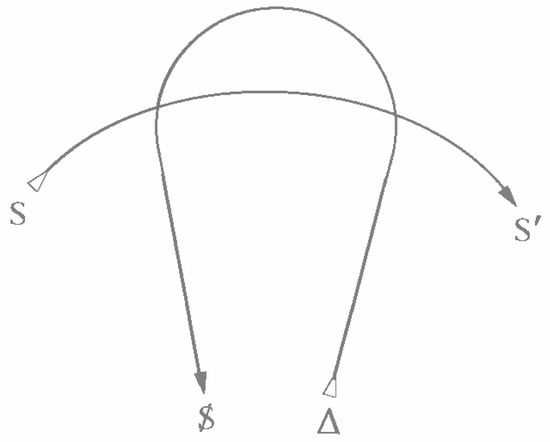

In Figure 1 we can see Lacanian graph of desire:

Figure 1.

Graph of desire. Source: J. Lacan (1966, p. 805) Subversion du sujet et dialectique du desir, in: Ecrits, Paris, Edition du Seuil.

The horizontal line in the graph represents the signifying chain. The horseshoe-shaped line represents the vector of the subject’s intentionality. The intersections of these two lines illustrate the nature of retroaction, namely, the message. As Lacan explains:

This is what might be called its elementary cell [the graph- aut.]. In it is articulated what I have called the “button tie” (…) The diachronic function of this button tie can be found in a sentence, insofar as a sentence closes its signification only with its last term, each term being anticipated in the construction constituted by the other terms and, inversely, sealing their meaning by its retroactive effect. But the synchronic structure is more hidden, and it is this structure that brings us to the beginning.(Lacan 2007, pp. 681–82)

We see here the realization of desire in a dream and in reality (a symbolic order). In this sense, language is the insurmountable limit and metaphor of being. Every message, claim, and statement tells us something about the subject. Of course, it is only partial, fragmented, and always incomplete “information” about the desire of the subject.6

Desire is also established by what is lost at the intersection of imaginary and symbolic orders. Desire penetrates human subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and cultural processes, so it cannot be limited only to the sleeping state. When we look again at the fragment of the passage from Chapter II of the Zhuangzi, we can clearly see in this context the relationship between the dream and reality. “If you dream of drinking wine, in the morning you will weep. If you dream of weeping, in the morning you will go hunting,” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 19). What does this fragment tell us about desire? Does desire have a negative connotation? To answer for this question from a Lacanian perspective, we have to say more about fantasy and its function.

For Lacan, fantasy is a fruitless attempt to respond to the enigma of desire. Fantasy exists in the symbolic structure or order (the non-sleeping, waking state). Simply speaking, fantasy derives from psychic projection. It is like an immobile, freeze-frame image whose function is the concealing of the traumatic image that will come next. In fantasy, the image is absolutely not in opposition to perceptual traces. Fantasy has the power and potential to rework memory by means of both the pressure of unconscious desires and the defensive strategies applied by the subject. The object is always represented in the fantasy as in the dream. Fantasy is like a scenario in which the object is the cause of desire. In this way, the subject searches for imaginary and concrete objects to take their place in the realization of the desire, as fantasy is the knotting in the typology of the three stages: Real, Symbolic, and Imaginary.

Lacan presents fantasy in the following formula: $◇a (Lacan 1973, p. 190). “$” is the subject. “◇”is the desire “a” is an object of desire. This formula is to be read as a barred subject in relation to the other. The barred subject is not equal to the absolute, complete denial of oneself. Rather, this bar means that the subject is “dependent” on the relation to the other, becoming herself in relation to the other. In this way, the bar on the subject means that she is always alienated, divided from herself. The barred subject never knows herself completely, but rather will always be cut off from her own knowledge. This means that the subject never can be fully self-conscious. It also denotes that desire constitutes the subject. Lacan explains this in the following way: “Let us say that in its fundamental use the phantasy (fantasme) is that by which the subject sustains himself at the level of his vanishing desire, vanishing in so far as the very satisfaction of demand hides his object from him,” (Lacan 2005, p. 207).

Fantasy is connected with desires, and human desire is a desire for the desire of the other. In this sense, we can say that the person contemplates itself in the other, and so I find in the other the desire of my desire. The object of desire is located prior to the desire and functions as its cause. Thus, the fragment from the chapter II reading, from a psychoanalytic perspective, denotes to us something about the becoming of the subject. All formulations, dreams, and regrets “create” and “shape” human identity. Desire is the heart of human existence. It is not any kind of desire as such, but rather is unconscious desire. As the graph of desire shows, when you articulate your desire, you bring it into existence. By your desires, you identify yourself as a human being, and the metaphorical realization of desires can be fulfilled in the dream:

The phantasy is the support of desire; it is not the object that is the support of desire. The subject sustains himself as desiring in relation to an ever more signifying ensemble. This is apparent enough in the form of scenario it assumes, in which the subject, more or less recognizable, is somewhere, split, divided, generally double, in his relation to the object, which usually does not show its true face either.(Lacan 1979, p. 185)

The desire is realized in the dream and without success in the fantasy.7 It isn’t the phenomenon which is entirely given. For Lacan, the clue of the relation between the dream and the identity of the subject is the naming of its own desire. (It is also important in the process of psychoanalytic treatment.) In naming the desire, the subject brings its own presence, but as Lacan pointed out, the desire can never fully be articulated by the speech, as “desire is articulated that it is not articulable,” (Lacan 2007, p. 681).

To more deeply explain this relationship, let us consider a passage from The Chapter VI of the Zhuangzi. In this fragment, we see the problem of identification in the state of dreaming and that of being awake:

You temporarily get involved in something or other and proceed to call it “myself”—but how can we know if what we call “self” has any self to it? You dream you are a bird and find yourself soaring in the heavens, you dream you are a fish and find yourself submerged in the depths. I cannot even know if what I’m saying now is a dream or not. An upsurge of pleasure does not reach the smile it inspires, a burst of laughter does not reach the jest that evoked it. But when you rest securely in your place in the sequence, however things are arranged, and yet separate each passing transformation from the rest, then you enter into the clear oneness of Heaven. (Ziporyn 2009, p. 89)

The passage tells us that we never be able to know the ultimate truth of what is a dream and what is not. Even if you do not dream during sleep, you are dreaming in reality. And even if you do not have a dream in reality or in a sleeping state, in fact, this non-dreaming can be an illusion and you may be in a dreaming state. In this passage, the person doubts which state he is actually in, dreaming or not dreaming: “I cannot even know if what I’m saying now is a dream or not” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 89). This question is connected with a subversive question about his identity: “How can we know if what we call ‘self’ has any self to it?” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 89) Because of the transformation (hua 化) of things, everything is fluctual and unstable, including dreaming and non-dreaming, and identity and non-identity. It is like an oneiric movement where illusion becomes reality and reality becomes an illusion. And in this sense, of course it is not possible for him to identify himself fully as a subject conscious of his own self, his own “I”. How can we view this process from the perspective of psychoanalysis? From the psychoanalytic perspective the, problem looks different. When we sleep, we are present and absent at the same time. How is this possible? It is not true that when we are awake, we are fully conscious and that during sleep, we are not. This is because during sleep, we dream, and we “dream” also in reality. Lacan sees the problem in this way:

If the function of the dream is to prolong the sleep, if the dream, after all, may come some near to the reality that causes it, can we not say that it might correspond to this reality without emerging from sleep? (…) The question that arises … is—What is it that wakes the sleeper? Is it not in the dream, another reality?”(Lacan 1979, pp. 57–58)

This is the mark of ourselves as subjects. We don’t have here an empty process of transformation, but, on the contrary, we have in this movement the emergence of the subject. The dream contains portions of everything: the absurd, tragedy, drama, but nothing exclusively is the unconscious narration of the subject, a narration about herself in which all desires can be fulfilled, and in which all desires can be realized. It is a vibration, a fantasy existence, in which everything is breaking down and cracking under the weight of the permanent becoming of the subject. In the passage, the person mentions different dreams: dreams of being a fish, of being a bird. How are these dreams correlated with identity? The Desire is one of the fundamental issues for the construction of the identity of the subject. It’s also important to notice that for Lacan, desire isn’t only instinctual or based on biological impulses.

In the passage from chapter VI of the Zhuangzi we can see that dreaming to be a fish, a bird,8 or to be a human (“I cannot even know if what I’m saying now is a dream or not”; Ziporyn 2009, p. 89) is the realization in the dream of a desire that is repressed in reality (the symbolic order in Lacanian theory). Thus, according to Lacan’s formula of desire, the subject (here the person who dreams to be a fish or a bird) in reality finds the partial recompensation of desire in the objet petit a, and the images in the dream (the fish, the bird, and, very often in the Zhuangzi, a tree) are metaphorical representations of the desire for the other. Further on we can read: “An upsurge of pleasure does not reach the smile it inspires, a burst of laughter does not reach the jest that evoked it,” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 89). The contentment is only a small recompensation for the smile it caused.

3. The True Person and The Problem of Dreams

No difference exists between dreaming and waking, because a dream is also a kind of waking. When we articulate our dreams, we also in fact articulate our desires. By our dreams, we identify ourselves as humans with desires. How can we describe the True Person in this context? Does the True Person sleep without dreams? Let us go further and look closer at the problem of identifying the person who doesn’t dream. In chapter VI of the Zhuangzi we can find a description of the Genuine Human Being, the True Person:9

The Genuine Human Beings of old slept without dreaming and awoke without worries. Their food was plain but their breathing was deep. The Genuine Human Beings breathed from their heels, while the mass of men breathe from their throats. Submissive and defeated, they gulp down their words and just as soon vomit them back up. Their preferences and desires run deep, but the Heavenly Impulse is shallow in them. The Genuine Human Beings of old understood nothing about delighting in being alive or halting death. They emerged without delight, submerged again without resistance. Swooping in they came and swooping out they went, that and no more. They neither forgot where they came from nor asked where they would go. Receiving it, they delighted in it. Forgetting about it, they gave it back. This is what it means not to use the mind to push away the Course, not to use the Human to try to help the Heavenly. Such is what I’d call being a Genuine Human Being.”(Ziporyn 2009, pp. 40–41)

In this passage we see that for the Genuine Human Beings in the process of the transformation, not only do the boundaries between dream and not dream disappear, but also between live and death. As the text reads,” The Genuine Human Beings of old understood nothing about delighting in being alive or halting death.” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 40). We can consider that if you don’t make distinction between dreaming and not-dreaming, you might not see the difference between life and death. Thus, we can see that transformation, from philosophical perspective, is “incarnation of ambivalence” and without distinction one can “you keep all doors open any time”10

A new problem emerges in this fragment: does the Genuine Human Being have dreams at all? From a psychoanalytical perspective, the claim that the true person sleeps without dreams only shows that by this articulation, he communicates hidden, repressed desires. It also doesn’t mean that the True Human Being is free from dreams. On the contrary, within dreams appears everything that is repressed in reality. So the question is, does the True Person not follow his own desires? Does he not follow his own dreams? My answer is that even if he tries, he cannot avoid this problem. It is not possible even in the case of the True Person.

Psychoanalysis teaches us that dreams are the guardians of sleep and not its disturbers. The function of dreams is to get rid of psychical stimuli that are interfering with sleep. This process allows a repressed impulse to get satisfaction possible in these circumstances in the shape of hallucinatory satisfaction. Thus in this sense, the statement in the Zhuangzi passage shows that the True Person is dreaming to not have a dream. This repressive negation or disavowal of dreams, paradoxically, will find a way of realization in dreams. Is the True Person free from dreams? From a psychoanalytic perspective, of course not. What we have here is simply the speaking of hidden desires that can be realized in a dream. The Genuine Human Being isn’t free from dreams, and therefore he isn’t free from desires. According to the graph of desire (Figure 1) if you identified yourself as a human, even if you are a True Human, you already make distinctions, and so you place yourself and your identity within the net of desires and fantasies. The desire occurring in this context is not to have dreams.

For a better explanation of this problem let’s come back again to chapter II from the Zhuangzi:

If we follow whatever has so far taken shape, fully formed, in our minds making that our teacher, who could ever be without the teacher? The mind comes to be what it is by taking possession of whatever it selects out of the process of alternation -but does that mean it has to truly understand that process? The fool takes something up from it too. But to claim that there are any such things as “right” and “wrong” before they come to be fully formed in someone’s mind in this way—that is like saying you left for Yue today and arrived there yesterday. This is to regard to nonexistent as existent. The existence of the nonexistent is beyond the understanding of even divine sage-king Yu—so what possible sense could it make to someone like me?(Ziporyn 2009, p. 11)

Does the True Person really sleep without dreams? If we connect the passage above (to regard the non-existing as existing) with the identification of the True Human being we see that from a philosophical perspective, the True Person doesn’t exist. Rather, she is another illusion. In a philosophical sense, being a True Person means not being a True Person, not to be human at all. From a psychoanalytic perspective, the True Person in this indeterminate sense becomes a subject—without-identity with identity. True Person becomes a false image without making any distinctions and differences, and by becoming this she creates herself from the beginning, thereby becoming a subject. If she becomes a subject, she then has desires, dreams and fantasies.

As Lacan explains in one of his seminars: “Being of non-being, that is how I, as subject, come on the scene, conjugated with the double aporia of a true survival that is abolished by knowledge of itself,” (Lacan 2005, p. 229). We see here the person with a distorting effect. “If we choose being, the subject disappears, it eludes us, it falls into non-meaning. If we choose meaning, it survives only deprived of that part of non-meaning that is, strictly speaking, that which constitutes in the realization of the subject, the unconscious,” (Lacan 1979, p. 211). The meaning should be understood here in connection with desire (see Figure 1).

I also think that from a psychoanalytical point of view, in this fragment of chapter II about the existence of nonexistence, we have an ontological loop without a solution. When we connect this fragment with the subject and its identity, we will see that through the process of denial, the subject will always come back to its false identity. The negation of being creates the being, and then the negation of the whole of this process (the negation of the being creates being) leads again to being. This process does not have an end.

We can present this process in the following chain:

Subject = being → no-subject = being → (no-subject = being) = being → [no-subject = being) = being] = being →…

Lacan illustrates this problem in this way:

The subject constitutes himself only by subtracting himself from it and by decompleting is essentially, such that he must, one and the same time count himself here and function only as a lack here.(Lacan 2007, p. 683)

The subject, at each stage, becomes what he was (to be) before that, and he will have been is only announced in the future perfect tense.(Lacan 2007, p. 684)

What he wants to say is that there does not exist some linear, temporal process in which the subject becomes. Rather, it is a fluctual, spatial process. In this process of becoming, dreams, fantasies, and desires are the inevitable part of the subject. If it exists and becomes the subject, then so too emerge dreams, desires, and fantasies. All these phenomena create the being of the subject, every subject, and even the True Human Being. When we return to the True Human Being, we remark that his non-dreaming desire becomes a process of his becoming, of formulating his identity with desires and fantasies:

In the Phantasy, the subject is frequently unperceived, but he is always there, whether in the dream or in any of the more or less developed forms of day-dreaming. The subject situated himself as determined by the phantasy.(Lacan 1979, p. 185)

In chapter VI of the Zhuangzi, dying Zilai says to his friend Zili, “All at once I fall asleep. With a start I awaken” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 46). This statement above only confirms the process of transformation. We don’t find it here at a transcendental level, but again we find the claim that the difference between death and dreams is an illusion, as well as that between dream and non-dream or even maybe between the True Person and not. In this case, psychoanalysis will ask not only for the transformation of things or the relation between sleep and non-sleep, just as philosophy will, but also it will ask about the roots of this claim. Why did he think he was falling asleep but now is awake? Does this statement not contradict fundamental issue—the being and becoming by denying? Let’s look closer at whole passage of this story. The fragment begins with the friends Ziji, Ziyi, Zili, and Zilai. One of them says, “Who can see nothingness as his own head, life as his own spine, and death as his own ass? Who know the single body formed by life and death, existence and nonexistence? I will be his friend!” (Ziporyn 2009, p. 45). Later while sick Zilai says,

… getting it is a matter of the time, coming and losing it is just something else to follow along with. Content in the time and finding one’s place in the process of following along, joy and sorrow are unable to seep in. This is what the ancients called the Dangle and Release. We cannot release ourselves-being beings, we are always tried up by something. But it has long been the case that mere beings cannot overpower Heaven.(Ziporyn 2009, p. 45)

One and the same thing can be viewed from a negative or affirmative perspective, but nevertheless, it is problematic to make these kinds of differentiations and divisions, because in fact, all the time, we look at one and the same thing, one and the same existence, one and the same being, and one and the same becoming. Is the True Person really the True Person? Is the True Human Being really a True Human Being? Where are the boundaries of the assertions? There are no such boundaries from a spatial perspective. If we look at them not on a temporal level but from the spatial dimension of permanent, fluctual movement and transformation, the differentiations become another illusion. The limits always arise from the temporal perspective. However, it is important to notice that psychoanalysis, unlike philosophy, articulates the subject’s question in a particular way: “(…) the question of his existence bathes the subject, supports him, invades him, tears him apart even, is shown in the tensions, the lapses, the phantasies (fantasmes) (…)” (Lacan 2005, pp. 214–15).

4. Conclusions

In the Zhuangzi, the problem of the non dreaming person, when we approach it from the spatial, psychoanalytical level, is a paradox. The claim that the True Person sleeps without dreaming becomes absurd. Even if you hide your desires, as a True Human Being, in fact you make an identification of yourself by creating a desire not to have a desire, by creating a desire not to have dreams. Nevertheless, someone can assume counterargument from a famous sentence from the Zhuangzi, namely, that, “I have lost me” (吾丧我) (Ziporyn 2009, p. 9). But this is another key problem with the identification of the subject. By the losing itself, the subject becomes a being through non-being. By the illusion of losing the ego, the subject arises not on the level of self-reflection, but on the level of denying of one’s own existence, on the level of self-denial. Its psychoanalytical meaning, I can say is a disavowal. Again, I don’t see here any mysterious stage on which subject loses itself. Rather there is a creation of a kind of surrealistic identity by self-denial. The subject is alien to itself, and here we clearly see the split within the self and the creation of an illusory image about the self. The subject is instinctually empty. If we consider the subject from a philosophical perspective, however, behind these deliberations, psychoanalysis shows that the subject in its fantasies is able to represent itself as maintaining a desire. From a psychoanalytic perspective, the creation of the subject by his dreams and fantasies is the process ex nihilo which also, paradoxically, places him in a question (see the formula of fantasy above). The existence of the subject and its essence, its identity, is rooted not in not having dreams, not in being the True Human being, not in losing himself, but rather in his structural distortion, in the rupture from which even the True Human being is not free, just as he is not free from dreams and desires. In this sense the statement that True Human being sleeps without dreams is only an illusory wish, a desire by which the subject comes into being.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Allinson, Robert E. 2012. Snakes and Dragons, Rat’s Liver and Fly’s Leg: The Butterfly Dream Revisited. Dao 11: 530–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, Steven C. 2005. The Dao of Rhetoric. New York: State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, Paul J. 2016. Guo Xiang on Self-So Knowledge. Asian Philosophy 26: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, Paul J. 2017. Imagination in the Zhuangzi: The Madman of Chu’s Alternative to Confucian Cultivation. Asian Philosophy 27: 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, Paul J., Hans Rudolf Kantor, and Hans Georg Moeller. 2018. Incongruent Names: A Theme in the History of Chinese Philosophy. Dao Journal of Comparative Philosophy 17: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyers, Tom. 2012. Lacan and the Concept of the Real. London: Palgrave Mamillan. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders, Sara. 1993. The Dream Discourse Today. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 2010. Interpretations of the Dreams. Translated by James Strachery. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 2015. A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. London: Dodo Collections. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskins, Robert W. 1997. The Transformation of Things. A Reanalysis of Chuang Tzu’s Butterfly Dream. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 24: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1966. Au-de la du Principe de Realite, Ecrits. Paris: Edition du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1973. Les Quatre Concepts Fondamentaux De La Psychoanalyse. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1979. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 2005. Ecrits. A selsction. Translated by Alan Sheridan. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 2007. Ecrits. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, Hans Georg, and Paul J. D’Ambrosio. 2017. Genuine Pretending: On The Philosophy of the Zhuangzi. New York: Columbia Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, Hans Georg. 1999. Zhuangzi’s Dream of the Butterfly: A Daoist Interpretation. Philosophy East and West 49: 439–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, Hans Georg. 2017. On second-order observation and genuine pretending: Coming to terms with society. Thesis Eleven 143: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancy, Jean Luc. 2009a. Identity and Trembling, in The Birth to Presence. Translated by Brian Holmes. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nancy, Jean Luc. 2009b. The Fall of Sleep. Translated by Charlotte Mandell. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, James F. 2008. The Limits of Dream. Oxford: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, Andrea. 2004. The Mind at Night. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haute, Philippe. 2002. Against Adaptation. Lacan’s Subversion of the Subject. Translated by Paul Crowe, and Miranda Vankert. New York: Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziporyn, Brook. 2009. Zhuangzi. The Essential Writing. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In the Western philosophical tradition, many Authors are focused on the topic of dreaming as it relates to issue in the relation mind and body. For example, Descartes asked whether you can be sure that you are not at this moment only dreaming that you are awake. Kant claimed that the madman is a waking dreamer. Compare this to the idea that: “Sleep, perhaps, has never been philosophical” (Nancy 2009a, p. 13). “There is no phenomenology of sleep, for it shows of itself only its disappearance, its burrowing and its concealment. But by concealing itself, it brings, on the other hand, the possibility, further and stronger than any phenomenality, of a disposition of intentions and aims as well as the fulfillment of sense”. (Nancy 2009b, p. 13). |

| 2 | In the literature concerning the dreams it is possible to find scientific analyses based on the function of the brain and psychoanalytic interpretations. Very often, both explanations function in opposition. See for example: (Rock 2004; J. F. Pagel 2008; S. Flanders 1993). |

| 3 | In the article I will not discuss perhaps the most paradigmatic passage about the dreams in the Zhuangzi, namely the butterfly allegory. Lacan explained the butterfly parable in one of his Seminars (see Lacan 1979, p. 76). It would probably require an entire article to adequately deal with this issue. For expert philosophical treatments of the butterfly dream, see (Gaskins 1997; Moeller 1999; Allinson 2012). |

| 4 | In the context of the transformation an influential explanation of the butterfly dream is given by Hans-Georg Moeller, whose analysis is decidedly different from dominant interpretation of skepticism or relativism. In Moeller’s interpretation Zhuang Zhou does not remember his dream, and as a consequence it is not possible to decide which instance is the reality and which one is a dream (see: Moeller 1999, pp. 439–50). As Moeller explains: “The segments are separated from each other by a sharp distinction -and this is precisely the reason they can be seamlessly connected with each other. The sharply distinguished segments constitute a continuous and perfectly connected whole just because they have nothing in common with each other. What is continuous is the process from segment to segment: each segment is complete in itself precisely because no part of it is transferred to the following segment” (Moeller 1999, p. 443). |

| 5 | Lacan distinguishes three stages or orders on which the subject functions: the Real, the Symbolic, and the Imaginary. He presented relations between these stages in the form of borromean rings. Each ring represents one stage. For secondary sources about the three orders, see, for example, (Eyers 2012; P. Van Haute 2002). |

| 6 | P. J. D’Ambrosio, H. R. Kantor and H. G. Moeller argue that incongruity between names and actualities or names and things is a constant theme in the history of Chinese thought. (See: P. J. D’Ambrosio et al. 2018). |

| 7 | Lacan saw a triadic relation between need, demand, and desire. Needs concern the biological level. A demand is its expression in the form of a request. A desire is a surplus irreducible to either. As he wrote “The desire begins to take shape in the margin in which demand becomes separated from need.” (Lacan 2005, p. 237). |

| 8 | It’s very interesting that these two creatures occur very often in the Zhuangzi in the context of a dream. |

| 9 | A new and innovative philosophical interpretation of the zhenren is offered by H. G. Moeller and P. D’Ambrosio (see: Moeller and D’Ambrosio 2017). Their True Person is strongly correlated with the creation of new terminology concerning identity. By this intervention, the authors present a fresh understanding of the term True Person. In this context, see also, H. G. Moeller (2017); P. J. D’Ambrosio (2017); P. J. D’Ambrosio (2016). For other, “classical” interpretations of the zhenren, see, for example, S. C. Combs 2005, pp. 37–43. |

| 10 | Moeller writes: “What is Daoistic is not the blurring of the borderlines between the segments, between (the two) Zhuang Zhou (s) and the butterfly, between being awake and dreaming, between life and death, nor the doubts about one’s “real I”, but rather the belief that the authenticity of each segment of a whole is guaranteed by the very fact that the segments are not connected to each other by any continuous bridge between them. It is un-Daoistic to believe that life and death are about the same and not clearly divided from each other: rather, life and death are as different, from the Daoist point of view, as they can possibly be” (Moeller 1999, p. 443). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).