Abstract

Objective: The aim was to validate a Romanian version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15) and to determine its psychometric properties in religious and highly religious people. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted in different religious confessions. The sample consisted of 146 (67.9%) Orthodox, 58 (27.0%) Seventh-day Adventists, 3 (1.4%) Catholics, one (0.5%) Pentecostal, and 7 (3.4%) others. Data were collected on the Romanian version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15), the Religious Belief Assessment Questionnaire (CACR), and the Moral Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (CACM). Results: The scale’s reliability analysis revealed an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. This demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. The Spearman correlation between the CRS scale’s total score and that of the Intimate and Expressive Religious Belief Assessment Questionnaire indicated positive levels of convergent validity. The Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) revealed good discriminative validity and the confirmatory analysis revealed a satisfactory fit. Conclusions: The validated Romanian version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15) is a valid and reliable measure in detecting the centrality of religiosity.

1. Introduction

Man’s acceptance and positioning in relation to God involves a multidimensional approach to religious engagement including attitudes, beliefs, emotions, experiences and rituals (Küçükcan 2000). In this study we propose a measure of religiosity appropriate to the preeminent religious confessions in Romania. Many researchers have developed various operations of religiosity. An exhaustive presentation of various conceptualizations of religiosity was made by Holdcroft (2006). Thus, she remembers the following models: Fukuyama’s model (1960) examining four dimensions, cognitive, cultic, creedal, and devotional; the model of Glock and Stark (1965) that identified five dimensions of religiosity, experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, and consequential; the model of Allport and Ross (1967) that identified two dimensions, extrinsic and intrinsic; Lenski’s model (1963) that identified four dimensions, associational, communal, doctrinal, and devotional; Ellison’s model (1991) that examined four dimensions of religiosity, denominational ties, social integration, personal sense of the divine, and existential certainty. Many of these measures are specific to different religious cultures. Developed by Huber and Huber (2012), the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15) is a measure of the centrality, importance or prominence of religiosity in personality. Well designed and clearly operationalized, the CRS 15 scale combines Allport’s intrinsic religiosity with Glock’s idea of distinct expressions of religious life (Zwingmann et al. 2011). Starting from the content identified in Glock’s multidimensional model, which involves a religious-centered approach on social expectations, Huber and Huber (2012) redefines the contents of the five dimensions, giving them a psychological perspective. This approach was developed from the perspective of personality psychology inspired by Allport’s ideas and Kelly’s personal constructs of psychology (Zwingmann et al. 2011). Kelly proposed that people organize their experiences by developing bipolar dimensions of meaning or personal constructs. Interconnected hierarchical constructs are used to anticipate and predict how the world and its inhabitants behave, and how people can organize their psychological experience. Moreover, people can continuously test their personal constructs by watching how well these can predict the circumstances of life and review them when they are considered deficient (Raskin 2002) Kelly’s phenomenological and constructivist model emphasizes the individual’s personal perspective. His fundamental postulate is that personal experience and behavior depend radically on the construction of reality. Within this framework, religious beliefs are considered specific ways of building reality (Huber 2007). The model of the centrality of religiosity distinguishes between the centrality of the religious construct system, in the all constructs-personal system, and the religious contents within the construct-religious system (Huber 2009). Huber et al. (2011) postulate that the more centrally the religious construct system is positioned, the more intensive its influence will be on other personal construct systems and, thus, on that person’s experience and behavior. Approaching a person’s world and life from a religious point of view makes it possible to build a system of legitimate and coherent meanings according to which life events are interpreted (Krok 2017). The scale construction strategy is based on two prerequisites. The first concerns the question of representativeness which presupposes the existence of those expressions of representative religiosity for the whole of religious life. The second relates to the generalizability of the religious content targeted by the indicators; the identified contents must be significant and acceptable in most religious traditions (Huber and Huber 2012). The reconfigured content of the dimensions gave the scale a character of universality. Thus, the intellectual dimension refers to themes of interest, hermeneutical skills, styles of thought and interpretations, and as odies of knowledge. The ideological dimension includes beliefs, unquestionable convictions and patterns of plausibility. The dimension of public practice refers to patterns of action and sense of belonging to a particular social organism as well as to a certain ritualized imagination of transcendence. The private practice includes patterns of action, a personal style of devotion to transcendence, and the dimension of religious experience represented as patterns of religious perceptions and as a body of religious experiences and feelings. Based on the scores, the scale makes distinctions between non-religious, religious, and highly religious groups (Huber and Huber 2012). Thus, in the highly religious group, the religious system occupies a central position in personality; from this position, religious content exerts strong influence over other psychological systems. As a consequence, the non-religious fields of experience and action often appear in a religious light. In the religious group, the religious system occupies a subordinate position in personality. From this position, the influence on other psychological systems is weak; as a consequence non-religious fields of experience and action rarely appear in a religious light. In the non-religious group, the religious system occupies a marginal position. Religious content and practices hardly appear in the life of the individual. It is assumed that the religious meanings of these individuals have an ad hoc character and are formed on the basis of other personal constructs (Huber et al. 2011). The centrality of the system of religious meanings indicates its relevance in an individual’s cognitive and emotional system without reference to the specificity of its meaning (Dezutter et al. 2010). Huber’s Centrality of Religiosity was used in different countries in many studies (Batara 2015; Czyżowska and Mikołajewska 2017; Hassan et al. 2016). The aim of the study was to adapt the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15), determine its reliability and validity, and verify the adequacy of the adapted version of the five-dimensional scale.

2. Methods Section

2.1. Sample and Design

A total of 215 participants (63 male, 143 female, 9 gender not specified) with ages ranging from 14–51 years (mean = 19.45, SD = 6.75) were recruited from a general people of various religious confessions in different regions of Romania. Sampling was based on convenience. The scales were completed by participants after they were ensured that their participation in the study was anonymous and confidential. The purpose of the research was explained to every participant. The data were completed on a voluntary basis and with verbal consent. Sociodemographic data included age, gender, education level, marital status, and religious confession. The sample size was estimated to be 150 people. The justification for the sample size was based on a recommendation by (Labăr 2008).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15)

The English version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15), was translated into Romanian using the forward-backward translation design and following the guidelines provided by the literature (Beaton et al. 2000; Dunn et al. 1994). The scale was developed by Huber and Huber (2012) to measure the centrality, importance or salience of religious meanings in personality. The Romanian version of the scale was derived from the English version and was validated by the author. The items were formulated using simple and appropriate language relative to the concept. The scale consisted of 15 items divided into five subscales: intellect (1, 6, 11), ideology (2, 7, 12), public practice (3, 8, 13), private practice (4, 9, 14) and religious experience (5, 10, 15). Each subscale contained three items that measured the objective or subjective frequency or the intensity of personal religious constructs. The answers were measured by a five-point Likert scale, with the exception of certain items that had a different coding system. For events that may not occur regularly, subjective frequencies were recorded in five levels (never, rarely, occasionally, often and very often). For events where the frequency had an insignificant role (e.g., belief in something divine), the intensity or importance was evaluated with: not at all, not very much, moderately, quite a bit, or very much so. The item that refers to participation in religious service was coded as follows: more than once week and once a week—5, one to three times a month—4, a few times a year—3, less often—2 and never—1. The item that refers to the objective frequency of prayer was coded as follows: several times a day and once a day—5, more than once a week—4, once a week and one to three times a month—3, a few times a year or less—2 and never—1. The subscale results were the average of the items. The total result (CRS 15) was the sum of the subscale’s results. For the present sample, the Cronbach alpha for the CRS 15 was 0.93. For the subscales, Cronbach’s alpha was as follows: 0.80 for intellect (mean = 3.20; SD = 0.96), 0.61 for ideology (mean = 4.12; SD = 0.90), 0.82 for public practice (mean = 3.64; SD = 1.16), 0.85 for private practice (mean = 3.96; SD = 1.11) and 0.87 for religious experience (mean = 3.44; SD = 1.13).

2.2.2. The Religious Belief Assessment Questionnaire (CACR)

The Religious Belief Assessment Questionnaire was developed by Cucoș and Labăr (2008) to measure religious belief. The scale consists of 14 items divided into two subscales. The first subscale (CACR_IN) consists of 9 items and measures intimate religious belief. The second subscale (CACR_EX) consists of 5 items and measures expressive religious belief. The measurement is done via a six-point Likert scale (1—not at all true to 6—true to a great extent). The total result of each subscale was the sum of the items. For the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for intimate religious belief was 0.98 (mean = 42.66; SD = 13.43) and 0.90 (mean = 21.74; SD = 16.63) for expressive religious belief.

2.2.3. The Moral Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (CACM)

The Moral Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (CACM) was developed by Cucoș and Labăr (2008) to measure moral behavior. The scale consists of 14 items divided in two subscales. The first subscale (CACM_CR) consists of 8 items and measures specifically Christian moral behavior. The second subscale (CACM_G) consists of 6 items and measures general moral behavior. The measurement was done on a six-point Likert scale (1—not at all true; 6—to a great extent true). The total result of each subscale was the sum of the items. For the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for specifically Christian moral behavior was 0.83 (mean = 37.89; SD = 6.61) and 0.83 (mean = 29.22; SD = 4.97) for general moral behavior.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with SPSS v.20 in order to examine the fit of the CRS 15. We chose (a) the absolute match measures (CMIN/DF) that determined the degree to which the model predicted the observed correlation matrix and whose value was recommended to be below 5, as well as the RMSEA that indicated approximate fits of the pattern in population. We also chose (b) the incremental measures (TLI, CFI) that compared the proposed model to a baseline model that all other models should overtake and that indicated the discrepancy between the two models (Nokelainen 2009). A scale has good reliability if on different occasions, under different conditions and administered by different people the measurements are repeatable (Drost 2011). On a scale ranging between 0 and 1, an internal consistency index of over 0.7 ensures good reliability. Validity refers to the quality of an instrument to measure what it has intended to measure (Kimberlin and Winterstein 2008). Convergent validity was examined with Spearman correlation calculations between the scores of the CRS 15 and the scores of CACR_IN and CACR_EX. The Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) and the methods of known groups were used to examine the discriminative validity. A Mann–Whitney test was conducted to evaluate the possible differences between groups.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

The sample consisted of 146 (67.9%) Orthodox, 58 (27.0%) Seventh-day Adventists, 3 (1.4%) Catholics, one (0.5%) Pentecostal, and 7 (3.4%) others. Table 1 depicts the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in the present study.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants.

3.2. Confirmatory Analysis

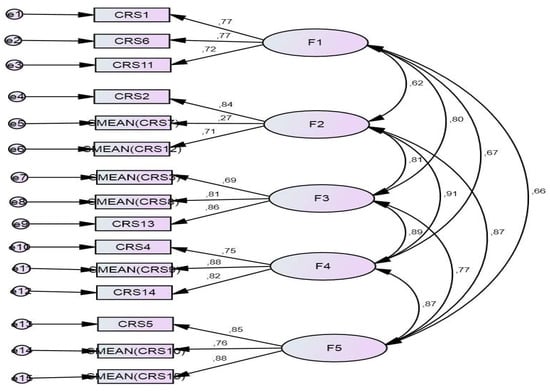

For testing the fit of the CRS scale, we conducted a confirmatory analysis with Amos 20.0. The results revealed a satisfactory fit of the structural model. The results were as follows: CMIN/DF = 2502; p = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.084 [0.069; 0.098]; TLI = 0.921; CFI = 0.94. The model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The theoretical model of the Romanian version of CRS 15.

3.3. Reliability and Validity

The scale’s reliability analysis revealed an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. The corrected item to total correlation was greater than 0.3 except for Item 7 (Item 7: To what extent do you believe in an afterlife—e.g., immortality of the soul, resurrection of the dead or reincarnation?). For theoretical relevance, we decided to keep Item 7 on the scale, because its removal did not lead to a significant increase in reliability (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The 15 item scale.

Convergent validity was supported by a significant correlation (0.83 **) between the CRS 15 total score and the CACR_IN total score and a significant correlation (0.76 **) between the CRS 15 total score and the CACR_EX total score. We also tested the alternative validation methods proposed by Huber and Huber (2012). The first showed that individuals with a high score had a more central religious construct system. This strategy was empirically tested by the high correlation between CRS total score and self-reports of the salience of religious identity (I consider myself a religious person). There is also a high correlation between CRS total score and self-reports of the importance of religion for daily life (Christian teachings help me in everyday life). The results of this strategy are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Convergent validity.

The second strategy consisted of a test of differential prediction assuming that in the highly religious group the system of personal religious constructs would be much more differentiated than that of the religious group and that the religious content (e.g., the experience of forgiveness by God) would have much stronger relevance for general psychological disposition (e.g., the willingness to forgive others in social situations) than in the religious group. We tested that strategy with the Mann–Whitney test. Table 4 depicts the results.

Table 4.

Discriminative validity.

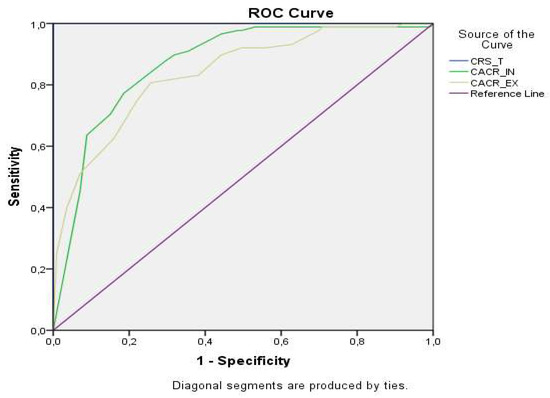

For the categorization of the groups, Huber and Huber (2012) proposes three scores: 1.0 to 2.0 for not religious, 2.1 to 3.9 for religious, and 4.0 to 5.0 for highly religious. We have used this categorization to determine the power of the discrimination of the scale using ROC curve analysis. Sensitivity shows how useful the test is for detecting the condition being investigated. Specificity shows how useful the test is for detecting people who are not being investigated (Søreide 2009). A ROC curve is a two-dimensional representation of classification performance (Fawcett 2004). In practice, the area under the curve is used when we want to see if a measure has predictive value (Fawcett 2006). Table 5 and Figure 2 depict the results of the analysis.

Table 5.

Area under curve, sensitivity and scale specificity.

Figure 2.

Area under curve for CRS 15, CACR_IN, CACR_EX.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to test the psychometric properties of the Romanian version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS 15) in a sample of different religious confessions. This scale has not been used in Romania before. In their studies, Huber and Huber (2012), found useable reliability for the CRS 15 (0.92–0.96). Our study showed a highly acceptable Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. Except for Item 7 (To what extent do you believe in an afterlife—e.g., immortality of the soul, resurrection of the dead or reincarnation?), all items had a correlation factor greater than 0.3 with the sum of the other items together. We considered the small correlation to be due to the word “reincarnation” specific to non-Christian religious traditions, which led to incorrect answers from many respondents. This assumption is in agreement with (Drost 2011), that misinterpretation of scale instructions and the existence of a small number of items can generate answers that lead to a greater degree of error. Other studies found similar psychometric properties of CRS (Zarzycka and Rydz 2014; Krok 2015). A significant correlation between the Romanian version of the CRS 15 total score and the two subscales of the Religious Belief Assessment Questionnaire (intimate and expressive religious belief) has indicated high convergent validity. The results of the alternative validation methods proposed by Huber and Huber (2012) showed good discriminative validity of the scale. These results have been confirmed by ROC curve analysis, which revealed high sensitivity and specificity. The confirmatory analysis showed a satisfactory fit of the Romanian version of CRS 15. The present study, however, has several limitations. A first limitation was Item 7, which led to unclear interpretations by the respondents. This study was conducted with a relatively small sample (n = 215). Some religious confessions were poorly represented and the respondents were recruited only from two areas of Romania.

4.2. Conclusions

The Romanian version of CRS 15 showed high reliability and good convergent and discriminative validity. The acceptable fit and high sensitivity and specificity of the scale are recommendations for its use in detecting the centrality of religiosity. The scale can be used in Romania for both the Orthodox majority population and other religious confessions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Batara, Jame Bryan Lamberte. 2015. Overlap of Religiosity and Spirituality among Filipinos and its Implications towards Religious Prosociality. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 4: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, Dorcas E., Claire Bombardier, Francis Guillemin, and Marcos Bosi Ferraz. 2000. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 25: 3186–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucoș, Constantin, and Adrian Vicențiu Labăr. 2008. Consecințe ale educației religioase asupra formării conduitelor tinerilor. Perspectiva beneficiarilor. Basiliana I: 65–102. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżowska, Dorota, and Kamila Mikołajewska. 2017. Religiosity and Young People’s Construction of Personal Identity. Roczniki Psychologiczne/Annals of Psychology 17: 131–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dezutter, Jesie, Linda A. Robertson, Koen Luyckx, and Dirk Hutsebaut. 2010. Life Satisfaction in Chronic Pain Patients: The Stress-Buffering Role of the Centrality of Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 507–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drost, Ellen A. 2011. Validity and Reliability in Social Science Research. Education Research and Perspectives 38: 105. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Steven C., Rbert F. Seaker, and Mattew A. Waller. 1994. Latent Variables in Business Logistics Research: Scale Development and Validation. Journal of Business Logistics 15: 145. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, Tom. 2004. ROC graphs: Notes and Practical Considerations for Researchers. Machine Learning 31: 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, Tom. 2006. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 27: 861–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Raza, Yousuf Anam, and Rasheed Rakshanda. 2016. Religiosity in Relation with Psychological Distress and Mental Wellbeing Among Muslims. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 5: 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Holdcroft, Barbara B. 2006. What is Religiosity. Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice 10: 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan. 2007. Are Religious Beliefs Relevant in Daily Life. In Religion Inside and Outside Traditional Institutions. Leiden: Brill, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan. 2009. On Opening the Black Box. Religious Determinants of the Political Relevance of religiosity. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor 2008. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 641–61. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo W. Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Stefan, Mathias Allemand, and Odilo W. Huber. 2011. Forgiveness by God and Human Forgivingness: The Centrality of the Religiosity Makes the Difference. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 33: 115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimberlin, Carole L., and Almut G. Winterstein. 2008. Validity and Reliability of Measurement Instruments Used in Research. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 65: 2276–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. Value Systems and Religiosity as Predictors of Non-Religious and Religious Coping with Stress in Early Adulthood. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 3: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2017. Religious Meaning System, Religious Coping, and Eudaimonistic Well-being-direct and Indirect Relations. Roczniki Psychologiczne/Annals of Psychology 17: 665–82. [Google Scholar]

- Küçükcan, Talip. 2000. Can Religiosity be Measured? Dimensions of Religious Commitment: Theories Revisited. Uludağ Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi. 9. Available online: http://www.eskieserler.com/dosyalar/mpdf%20(1135).pdf (accessed on 26 December 2018).

- Labăr, Adrian Vicențiu. 2008. SPSS pentru științele Educației. Metodologia analizei Datelor în Cercetarea Pedagogică. Iași: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Nokelainen, Petri. 2009. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. Retrieved on 22 April. Tampere: Research Centre for Vocational Education, University of Tampere. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin, Jonathan D. 2002. Constructivism in Psychology: Personal Construct Psychology, Radical Constructivism, and Social Constructionism. American Communication Journal 5: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Søreide, Kjetil. 2009. Receiver-operating Characteristic Curve Analysis in Diagnostic, Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker Research. Journal of Clinical Pathology 62: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarzycka, Beata, and Elzbieta Rydz. 2014. Centrality of Religiosity and Sense of Coherence: A Cross-Sectional Study with polish young, middle and late adults. International Journal of Social Science Studies 2: 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwingmann, Christian, Constantin Klein, and Arndt Büssing. 2011. Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Categorization of Instruments. Religions 2: 345–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).