Abstract

To ensure ship safety, safety culture is a critical factor in the organization of shipping companies. The safety climate has been evaluated to determine the level of a particular group’s safety culture. This study investigated South Korean seafarers’ safety culture awareness to compare whether there are differences between those who work on ships engaged in domestic and international voyages. In the latter, reinforced international regulations are applied. A questionnaire survey was conducted with 261 Korean seafarers using seven indicators representing the safety climate used in the aviation and maritime fields. Results showed that seafarers engaged in ocean-going navigation had a higher awareness of management involvement, organizational commitment, learning, and reporting systems, which yielded more positive effects than those engaged in domestic navigation. However, this did not significantly affect communication or employee empowerment. The survey methodology in this study can be used as an effective measure to assess the maritime safety climate; thus, it is possible to prepare policies and educational programs aimed at improving maritime safety.

1. Introduction

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) enacts various conventions and guidelines regarding the structure, equipment, and operation of ships to ensure navigational safety and protect the marine environment, and all vessels engaged in international voyages are subject to these regulations. However, marine casualties have continuously occurred and human errors have been known to be major causes of accidents, such as that of the Herald of Free Enterprise, which capsized in the Dover Strait in 1987, killing 193 people, and the Exxon Valdez, which spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil. Accordingly, the importance of the human factor has been raised in the international community. In 1994, the IMO introduced the International Safety Management (ISM) Code. The ISM Code requires a structured management system and documentation regarding ship operation, and ship company employees must implement safety measures to enhance the safety culture in their organization. The IMO recognizes the effectiveness of the ISM Code in promoting a safety culture and encourages its implementation in the maritime sector [1,2,3,4,5].

An approach that prioritizes safety for seafarers and ship owners is the best means of ensuring the safe operation of ships. Human error can be prevented by workers with high safety concerns. In 2019, 338 commercial vessels were involved in maritime accidents in Korea: 223 of these were domestic vessels (9.3% of 2388 registered ships) and 115 were international vessels (7.6% of 1026 registered vessels) [6]. The accident rate for domestic vessels is much higher than that for international vessels. Because safety culture is an important factor for safety management in the organization of ships and shipping companies, evaluating seafarers’ awareness of safety culture is a proactive manner of preventing ship accidents. To achieve this, developing the means to quantitatively evaluate seafarers’ perception of safety culture using appropriate indicators is required. In this study, two categories of seafarers—those embarking on international or domestic vessels—were compared and analyzed based on key factors for evaluating safety culture.

The goal was to investigate differences in Korean seafarers’ safety culture awareness. To this end, a tool was developed, and a quantitative evaluation was conducted on a group of seafarers embarking on international vessels and one embarking on domestic vessels. Various reinforced regulations, such as the international convention for the safety of life at sea, the convention on the international regulations for preventing collisions at sea, and the international convention on standards of training, certification and watchkeeping for seafarers (STCW), are being applied to ships engaged in international voyages. Furthermore, port state control and several statutory inspections are also being conducted on international vessels.

Do seafarers working on international ships have a higher safety culture awareness level? This question was answered through a quantitative evaluation, and the safety culture awareness level based on seven safety indicators was examined. There have been various studies on safety culture aboard international ships; however, no studies have assessed seafarers’ perceptions using the safety culture indicators in Korea. Therefore, this study is meaningful because the first to quantitatively analyze seafarers’ safety culture perception using safety culture indicators in the field of maritime affairs in Korea.

2. Theoretical Review

2.1. Safety Culture and Safety Climate

In the Chernobyl accident report by the International Atomic Energy Agency in 1986 [7], safety culture was mentioned for the first time by indicating that the main cause of the nuclear accidents was a “poor safety culture.” Subsequently, in 1991, research on the components of safety culture in the aviation field and the evaluation of the awareness of pilots’ safety culture for strengthening safety awareness were conducted with the accident analysis of the Continental Express Flight 2574 [8,9].

Following the Herald of Free Enterprise accident, studies on safety culture have been actively conducted in the marine sector since the late 1980s. The International Chamber of Shipping defines safety culture as sharing the notions of applying the best safety practices in the working field that will ultimately alleviate risks [10].

Although safety culture has been studied in various fields, there is still no consensus on its definition [11,12]. However, considering previous studies, safety culture in the maritime sector can be described as promoting safety improvements throughout the workplace by sharing the value of safety first with ship employees, and shipping companies acting and thinking on the basis of safety [13,14].

Another important aspect of safety culture is the safety climate, which is a temporary state in which safety culture can be measured [15]. That is, the safety climate has been measured in various studies to understand the safety culture, and it can represent the overall safety culture of a society [5].

2.2. Indicators and Evaluation of Safety Culture

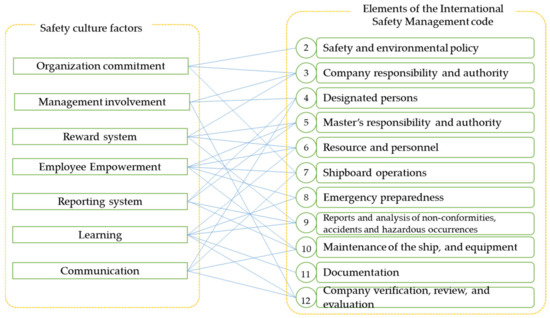

Wiegmann et al. [12] defined the elements constituting safety culture by analyzing 107 documents and 30 papers on safety culture and safety climate (Figure 1). Five indicators constitute a good safety culture: “management involvement, reward system, reporting system, employee empowerment, and organizational commitment” (p. 11).

Figure 1.

Safety culture indicators [12].

Lappalainen [16] noted that the five elements of safety culture defined by Wiegmann et al. [12] do not clearly present a continuous improvement process related to safety culture; however, they can be supplemented by a reward and reporting system. In South Korea, a quantitative survey [17] targeting 248 pilots to measure their safety cultural level was conducted by the Korea Transportation Safety Authority (KTSA) using the five indicators shown in Figure 1. Wiegmann et al. [18] developed the commercial aviation safety survey (CASS) scale. Whereas the CASS consists of 86 items, the KTSA [19] selected 46 items from the CASS scale after considering practical constraints such as pilots’ busy schedules; therefore, aviation pilots’ perceptions of safety culture could be identified by element.

As a practical plan for the application and improvement of safety culture, various studies have been conducted to measure the level of safety culture. Although quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods exist, as shown in Table 1 [12,19], no assessment method has been recognized as a global standard [20]. Qualitative assessments include observation, focus-group discussions, historical information reviews, and case analysis.

Table 1.

Measurement of safety culture (Source: adapted from [8]).

Quantitative evaluation methods include structured interviews, in which standardized items are asked to obtain short-answer responses from respondents, and Q-Sort, which is a means of surveying and observing behavior through symbol cards. Safety culture can be measured through questionnaires containing safety factors or indicators, which make it easy to investigate people’s perceptions of culture.

Table 2 presents studies that use quantitative techniques and organized indicators of the safety culture used in those studies. The aviation and shipping industries have quantitatively measured safety culture using these various indicators.

Table 2.

Summary of safety culture dimensions (Source: adapted from [8]).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology and Design Appropriateness

Quantitative techniques were used to enable the use of standardized research methods for related topics and the collection and analysis of data for a short period. The safety climate represents an aspect of safety culture and measuring the cultural perception of seafarers enables us to grasp the level of safety culture.

Studies on safety climate [11,20] have been conducted in the nuclear power industry and aviation sector since the 1990s. Since the late 2000s, maritime workers’ cultural awareness of safety has been assessed in several studies [7,26,27,28,29,30].

Teperi et al. [28] interviewed employees working in the maritime field to assess safety culture using a qualitative method. The qualitative method is useful to pose research questions to interviewees and closely investigate their thoughts as members of an organization or society. Meanwhile, the quantitative method has the advantage of being able to rapidly measure safety culture by using a previously developed and verified survey tool. For instance, Havold [29] conducted a large survey to measure the safety culture of tankers.

In Korea, a survey [30] targeting seafarers was conducted to scrutinize their behavioral characteristics to improve safety culture; however, in Korea, no studies have quantitatively analyzed seafarers’ awareness of safety culture using safety culture indicators.

Therefore, in this study, safety climate was measured through quantitative techniques. Specifically, a questionnaire was developed using questionnaires for aviation pilots and seafarers based on the safety culture indicators used in past research. This study used the five safety indicators developed by Wiegmann et al. [12]. Additionally, it also introduced two indicators provided by the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) [25] for evaluation in the maritime field.

To evaluate the safety cultural awareness among Korean seafarers, a survey was conducted of seafarers employed on international navigation ships or domestic ships. To ensure the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, an exploratory factor analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (Armonk, NY, USA).

3.2. Research Model

As shown in Figure 2, two categories of seafarers, consisting of seafarers aboard international navigation ships and those sailing in domestic waters, were analyzed and compared using seven factors.

Figure 2.

Research model (Source: adapted from [8]).

3.3. Development of the Questionnaire and Indicators for the Survey

To ensure valid research results, it is necessary to select appropriate indicators. As highlighted above, Wiegmann et al. [12] introduced five safety indicators. These indicators were selected through an extensive examination of the relevant literature of safety climate and culture. Moreover, in addition to Wiegmann et al.’s indicators, two factors required for measuring safety culture related to the ISM Code—communication and learning [27]—were added by analyzing the components of the ISM Codes. This is because the members need to learn about emergency measures or how to improve the system’s safety culture to enhance their safety culture awareness of the ISM Code, for which communication among members is essential. In Figure 3, each element of the safety culture was analyzed, and the seven indicators were matched with the relevant items. Learning and communication items were significantly correlated with the ISM Code elements. Consequently, a questionnaire was composed using the seven factors that represent safety culture (Table 3) [8].

Figure 3.

Relationship between the International Safety Management (ISM) Code and safety culture factors (Source: adopted from [8]).

Table 3.

Description of the seven safety culture indicators (Source: adopted from [8]).

3.4. Hypothesis

The ISM Code is intended to promote safety culture in shipping [34] and to reduce maritime accidents caused by human error. In addition to the ISM Code, various international rules and regulations are being applied, and intensified education and training programs are provided to seafarers embarking on international voyages.

The research question was whether the cultural awareness of safety differs between seafarers embarking on international vessels and those embarking on domestic vessels. The main research hypothesis was that “cultural awareness of safety of the seafarers working on international vessels will differ from that of seafarers working on domestic vessels.” We also established seven sub-hypotheses by applying the same logic to the seven safety culture factors (Table 4).

Table 4.

The seven sub-hypotheses (H) (Source: Adopted from [7]).

3.5. Questionnaire Design

To assess seafarers’ safety culture awareness, the indicators and questionnaires were selected from the reviewed literature, and the terms were revised to suit the maritime field. Consequently, it was composed of only 43 items considering seafarers’ busy schedules. No new survey items were created; instead, those from Wiegmann et al. [20] and KTSA [19] were used. Learning and communication indicators, which were composed of items presented in the ABS [27] and Song [24], were also added. The responses to each item followed a five-point Likert scale, and the items corresponding to each index were randomly arranged. Some items were reverse-scored. Item examples are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Questionnaire item examples (Source: adopted from [8]).

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ General Characteristics

The survey was conducted in South Korea in the second half of 2017. It was mainly conducted on incumbent seafarers on vacation, and we collected 261 questionnaires. Of these, 208 questionnaires were used for analysis after excluding nonconformities such as questionnaires with missing data (Table 6).

Table 6.

Respondents’ general characteristics (Source: adopted from [8]).

4.2. Validity and Reliability of Survey Items

When developing a survey or conducting statistical analysis, the validity and reliability of these tools should be ensured. Specifically, reliability analysis indicates the accuracy of a measurement tool and confirms whether respondents were consistently measured, whereas validity indicates whether the tool accurately measures the concept. Using Cronbach’s α, the reliability of our survey was confirmed. All seven factors obtained a value of 0.6 or more, indicating the reliability of the scale. Each item was sorted by the same factor through an exploratory factor analysis. Six items were removed due to low reliability; thus, 37 items were eventually used in the questionnaire.

To validate the measurement tool, an exploratory element was analyzed, and questions with a value of factor loading more than 0.4 were used. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure had a value of 0.928, which was appropriate for the variables. Bartlett’s test of sphericity revealed a p-value < 0.01, confirming that the element analysis model was appropriate.

4.3. Analyzing Indicators of Safety Culture between the Groups

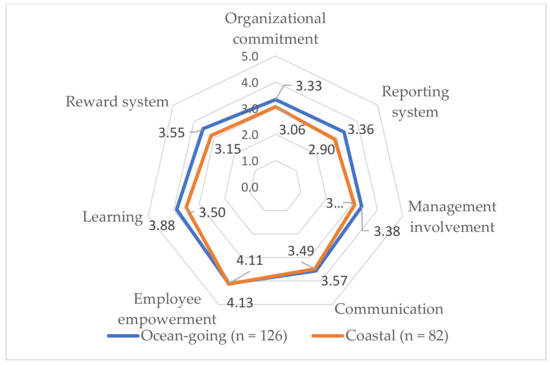

The average values of seafarers’ awareness were 3.50 and 3.33 for those working on international or domestic ships, respectively. Figure 4 compares each element of safety culture.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of awareness on indicators of safety culture (Source: adopted from [8]).

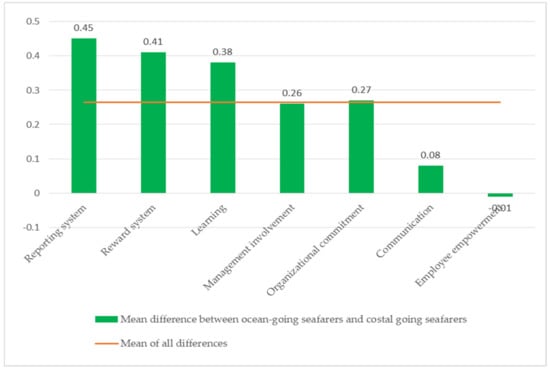

Figure 5 compares the differences in perceptions between groups by each indicator.

Figure 5.

Differences in perception of the indicators (Source: adopted from [8]).

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

To verify the seven hypotheses established in the previous section, independent sample t-tests were performed for each indicator (Table 7). Significant (p < 0.05) differences were revealed between groups concerning the perception of the safety culture, including management involvement, reporting system, reward system, organizational commitment, and learning.

Table 7.

Results of t-test (Source: adapted from: [8]).

According to these results, H1, H2, H3, H5, and H6 were supported, whereas H4 and H7 were rejected (Table 8).

Table 8.

Verification of the hypotheses (Source: adapted from: [8]).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study quantitatively measured safety culture awareness in Korean seafarers. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire were verified. This study also verified differences in safety culture awareness between seafarers embarking on international and domestic ships, including several safety factors: communication, learning, reporting system, employee empowerment, reward system, organizational commitment, and management involvement. Prior studies were reviewed to select these safety culture indicators and ISM codes that promote marine safety culture were also analyzed.

Seafarers’ safety culture awareness level is directly related to maritime safety and can be ascertained by continuously improving the measurement techniques and by analyzing the seven indicators used. For example, items that showed the greatest difference between the groups were reporting systems, reward systems, and learning, which are understood to be the strongest factors related to seafarers’ safety perception on international vessels. Policies and training measures are needed to promote these factors on domestic vessels. In contrast, no differences were observed between groups concerning employee empowerment or communication—regardless of the navigational area, our Korean seafarers demonstrated common values for these factors.

To enhance ships’ safety, it is important to improve seafarers’ safety awareness. This study found that there was a significant difference in safety culture awareness between groups of seafarers embarking on international ships and those embarking on domestic ships. In particular, seafarers working on domestic (vs. international) vessels had relatively low levels of the following safety indicators: learning, reporting system, reward system, organizational commitment, and management involvement. Various reasons exist for such differences; however, the most representative factors originated from the education level and the Safety Management System (SMS) according to the relevant studies conducted in Korea [34,35]. Therefore, in this section, we propose implications focusing on seafarers’ education and SMSs.

To improve the safety culture awareness of Korean seafarers engaged in domestic voyages, it is also necessary to review the maritime education policy. Mandatory education under the STCW has been introduced and implemented in Korea; however, the international convention was only partially introduced in Korean law for seafarers aboard domestic vessels. Kim [30] indicated that, among Korean seafarers, the education level of those aboard domestic ships is low, which affects the safety culture awareness. Therefore, the educational systems currently in operation in Korea should be improved by including subjects that can strengthen safety culture factors, such as reporting systems and learning. It would be an optimal policy to implement an education system related to safety culture and human elements, such as leadership and teamwork, for seafarers aboard both international and domestic ships. Domestic shipping companies should also provide more support related to seafarer training.

The SMS is implemented in accordance with the Maritime Safety Act in Korea; however, the audit system for domestic ships is being implemented as a simplified system compared to international vessels [34]. In particular, related to the reporting system, the learning and rewarding systems were identified as vulnerable factors among domestic vessel seafarers and the reporting system needs to be reinforced with the safety management manager of the shipping company. Moreover, since the reward and punishment system are key factors in promoting safe behavior and stopping unsafe behavior, the reward system in the safety management system of ships sailing in domestic ports needs to be strengthened. These problems can be solved by reinforcing the internal audit system, which is lacking in the current SMS for domestic vessels under domestic law.

Because maritime safety culture is an intangible concept, it is difficult to measure and comprehend. However, the safety culture awareness level can be measured through the measurement methodology used in this study, which was prepared based on related research cases and aviation research cases. Furthermore, it is possible to use it to prepare measures to improve the awareness of maritime safety culture. By evaluating the safety culture awareness level for each factor, it can be used to identify deficiencies and positive elements, and to develop specialized systems that can improve safety awareness.

A limitation of the study is that only a quantitative method was employed. In recent research trends related to safety culture, qualitative study (individual interviews, group discussions) have become more recognized [28]. Therefore, more in-depth results should be obtained through interviews with seafarers in future studies. Furthermore, more complex aspects of education, salary levels, size of shipping companies, and occupational awareness could impact the findings; therefore, these need to be considered in further studies. Finally, in Korea, few studies have quantitatively examined maritime safety culture, and none have measured seafarers’ safety culture perceptions. Future researchers should study seafarers in other Asian countries and globally.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This study was written from a thesis at World Maritime University in 2017, and I would like to express my gratitude to Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs, WMU Vice President, who guided me in writing the thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, P. The ISM Code: A Practical Guide to the Legal and Insurance Implications; Informa Law from Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. Revised Guidelines on the Implementation of the International Safety (ISM) Code by Administrations, Resolution A; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2013; p. 1071. [Google Scholar]

- Kongsvik, T.Ø.; Størkersen, K.V.; Antonsen, S. The relationship between regulation, safety management systems and safety culture in the maritime industry. In Safety, Reliability and Risk Analysis: Beyond the Horizon; Steenbergen, R., Ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2013; pp. 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder-Hinrichs, J.U. Human and organizational factors in the maritime world—Are we keeping up to speed? WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2010, 9, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization. International Management Code for the Safe Operation of Ships and Pollution Prevention; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Maritime Institute. Statistical Handbook—Shipping & Port Field; Korea Maritime Institute: Busan, Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, Y. Employee engagement in the shipping industry: A study of engagement among Indian officers. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2015, 14, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M. A Study on the Effectiveness of the ISM Code on the Seafarers’ Awareness of Safety Culture. Master’s Thesis, World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thaden, T.L.; Gibbons, A.M. The Safety Culture Indicator Scale Measurement System (SCISMS); National Technical Information Service Final Report; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 1–57.

- International Chamber of Shipping. Implementing an Effective Safety Culture. 2013. Available online: http://www.ics-shipping.org/docs/default-source/resources/safety-security-and-operations/implementing-an-effective-safety-culture.pdf?sfvrsn=8 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Guldenmund, F.W. The nature of safety culture: A review of theory and research. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Zhang, H.; von Thaden, T.L.; Sharman, G.; Mitchell, A. A Synthesis of Safety Culture and Safety Climate Research; University of Illinois, Aviation Research Lab: Savoy, IL, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. Safety@Sea Conference—“Building a Resilient Safety@Sea Culture”. 2016. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/SecretaryGeneral/SpeechesByTheSecretaryGeneral/Pages/SAfetyatSEaconf2016.aspx (accessed on 26 November 2016).

- International Maritime Organization. Assessment of the Impact and Effectiveness of Implementation of the ISM Code; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.L.; Wiegmann, D.A.; von Thaden, T.L.; Sharman, G.; Mitchell, A. Safety culture: A concept in chaos? Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2002, 46, 1404–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, J. Finnish Maritime Personnel’s Conceptions on Safety Management and Safety Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Turku, Turku, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Transportation Safety Authority. A Study on Development and Application of Aviation Safety Culture Index; Korea Transportation Safety Authority: Gimcheon-si, Korea, 2008.

- Wiegmann, D.A.; Zhang, H.; von Thaden, T.L.; Sharman, G.; Gibbons, A. Development and Initial Validation of a Safety Culture Survey for Commercial Aviation Federal Aviation Administration Technical Report AHFD-03-3/FAAA-03-1; The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.J. Review of safety culture for implementation in commercial aviation. Aviat. Dev. 2012, 59, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S.; Flin, R. Safety culture: Philosopher’s stone or man of straw? Work Stress 1998, 12, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, R. The development of a new safety culture evaluation index system. Proc. Eng. 2012, 43, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H. An Empirical Analysis on the Perception of Safety Culture: Focused on Air Traffic Controllers and Pilots. Master’s Thesis, Korea Aerospace University, Goyang, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ek, Å.; Runefors, M.; Borell, J. Relationships between safety culture aspects—A work process to enable interpretation. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, V.; Kurt, R.E.; Turan, O.; De Wolff, L. Safety culture assessment and implementation framework to enhance maritime safety. Transp. Res. Proc. 2016, 14, 3895–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Bureau of Shipping. Safety Culture and Leading Indicators of Safety; American Bureau of Shipping: Houston, TX, USA, 2012; Available online: https://maritimesafetyinnovationlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/abs-safety-culture-and-leading-indicators-of-safety.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2017).

- Bhattacharya, S. The effectiveness of the ISM Code: A qualitative enquiry. Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P. Cracking the Code; The Nautical Institute: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Teperi, A.-M.; Lappalainen, J.; Puro, V.; Perttula, P. Assessing artefacts of maritime safety culture—Current state and prerequisites for improvement. WMU J. Marit. Aff. 2019, 18, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håvold, J.I. Safety culture and safety management aboard tankers. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2010, 95, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-M. Study on Improving Safety Cultures by Analysing Behavior Characteristics of Korean Seafarers. J. Korean Soc. Mar. Environ. Saf. 2013, 19, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, L.; Wilhelmsen, C.; Kaplan, B. Assessing safety culture. Nucl. Saf. 1993, 34, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Ek, Å. Safety Culture in Sea and Aviation Transport Ergonomics and Aerosol Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2006. Available online: http://portal.research.lu.se/ws/files/4508145/546921.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Glendon, A.; Stanton, N. Perspectives on safety culture. Saf. Sci. 2000, 34, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs. Research on the Improvement of the Safety Management System for Prevention of Large-scale Maritime Accident; Ministry of Land, Transport and Maritime Affairs: Seoul, Korea, 2010.

- Kim, Y. Reviewing the Problematic Issues of Revised Current Law Provisions Regarding the Safety of Vessel after the Sewol Disaster Occurred. J. Korea Ins. Mar. Law 2015, 37, 247–288. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002049370 (accessed on 20 December 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).