Spatio-Temporal Variability of Anthropogenic and Natural Wrack Accumulations along the Driftline: Marine Litter Overcomes Wrack in the Northern Sandy Beaches of Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

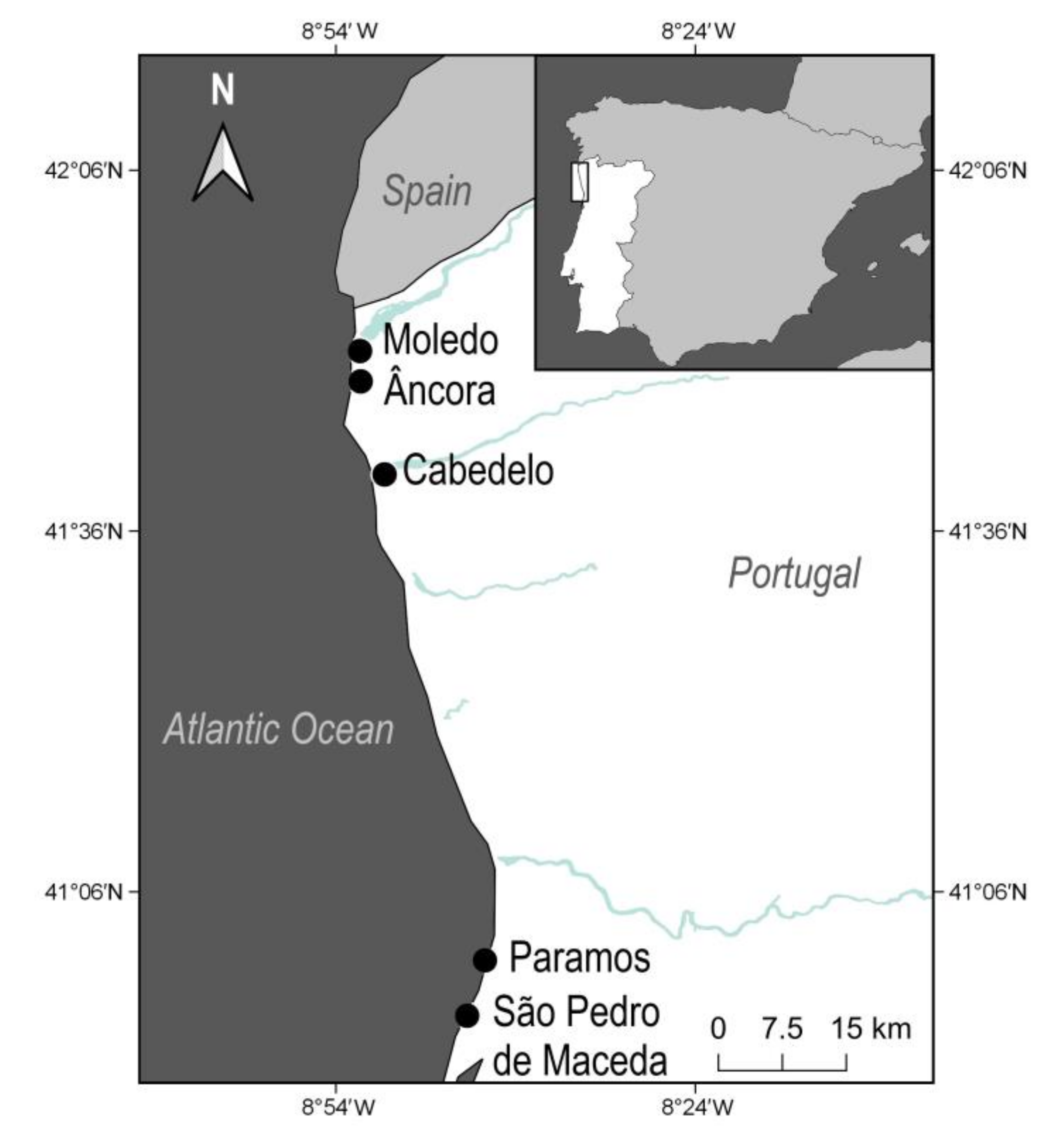

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Collection of Marine Litter and Natural Wrack

2.3. Data Analyses

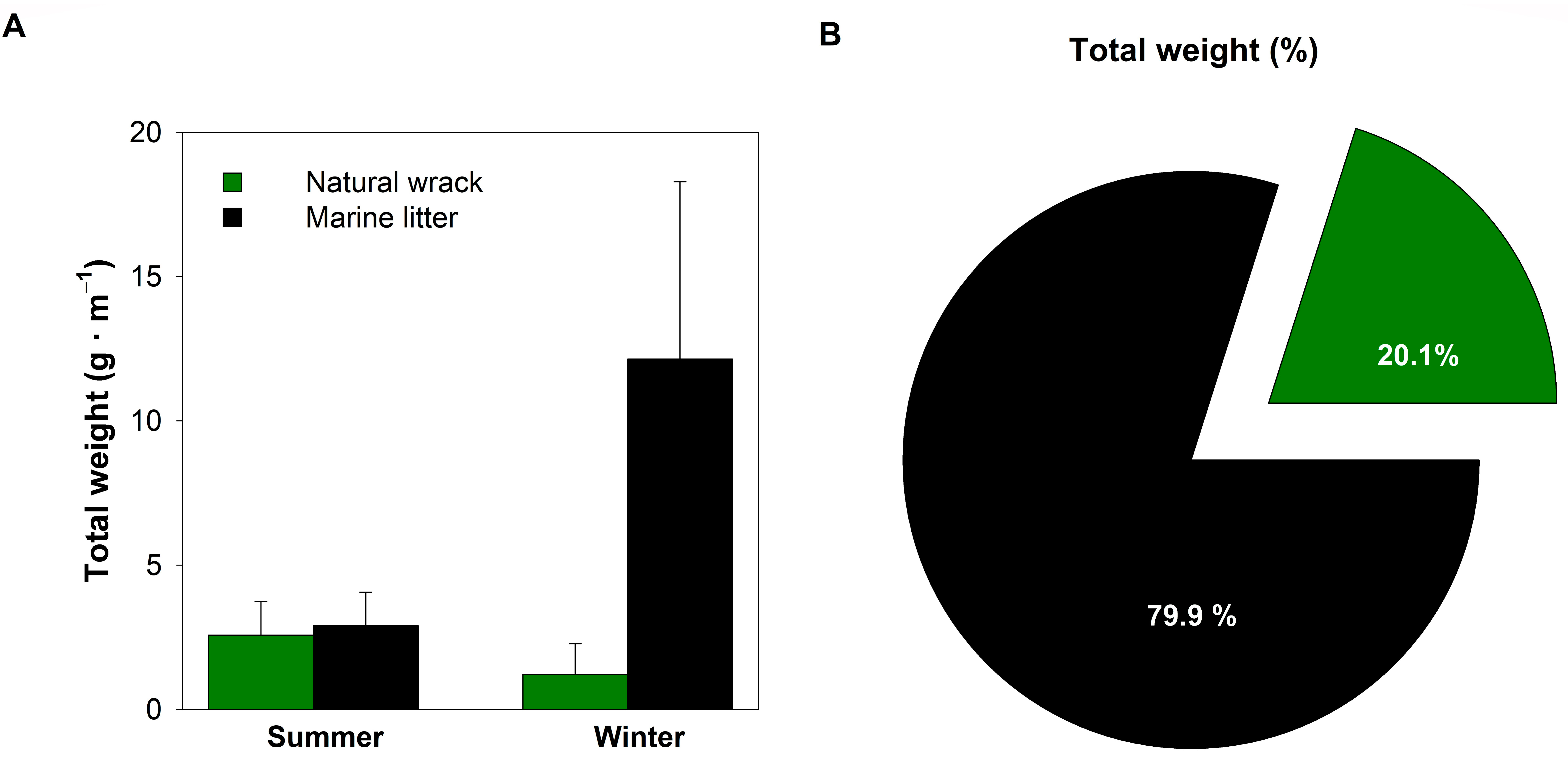

3. Results

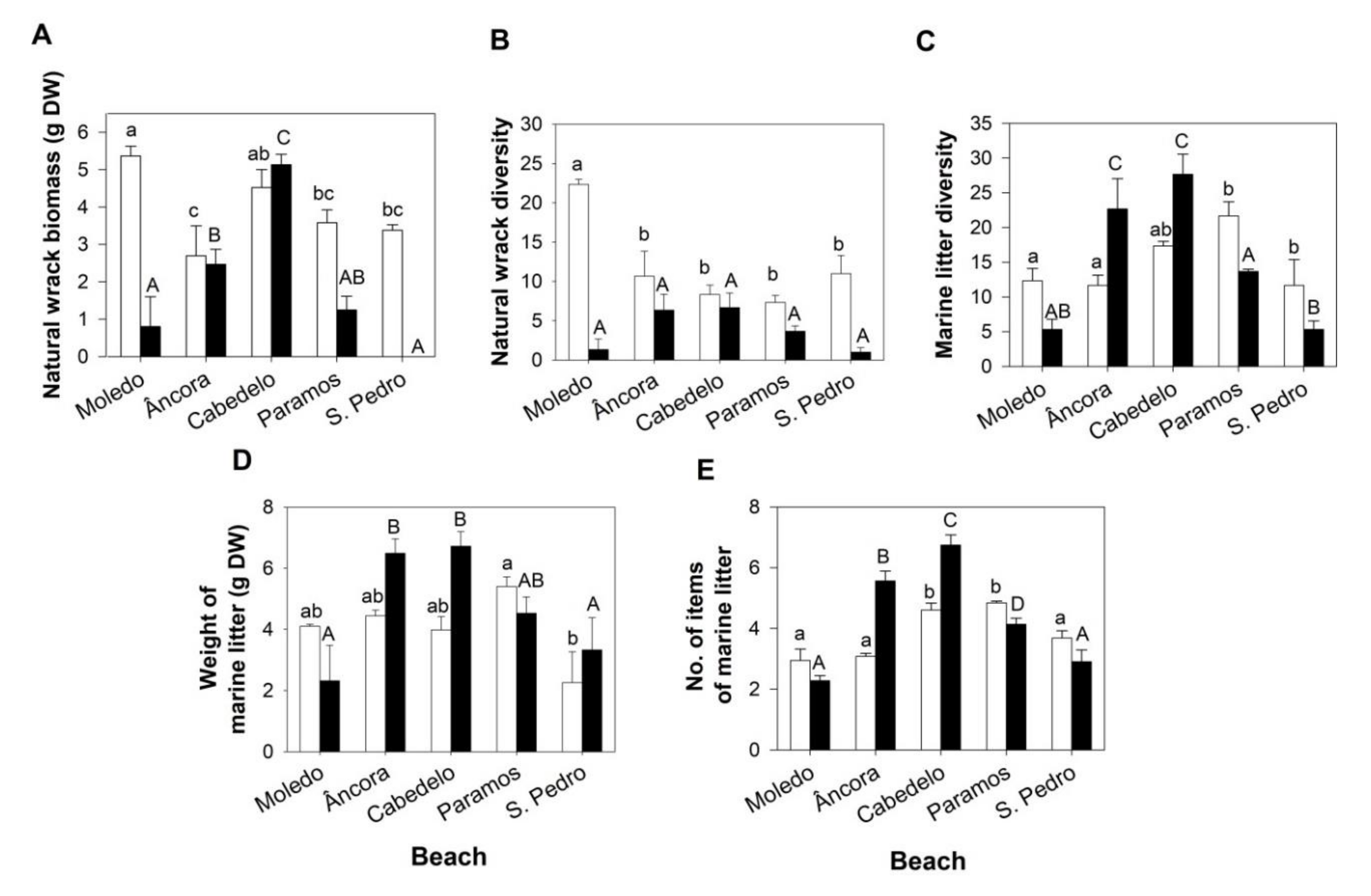

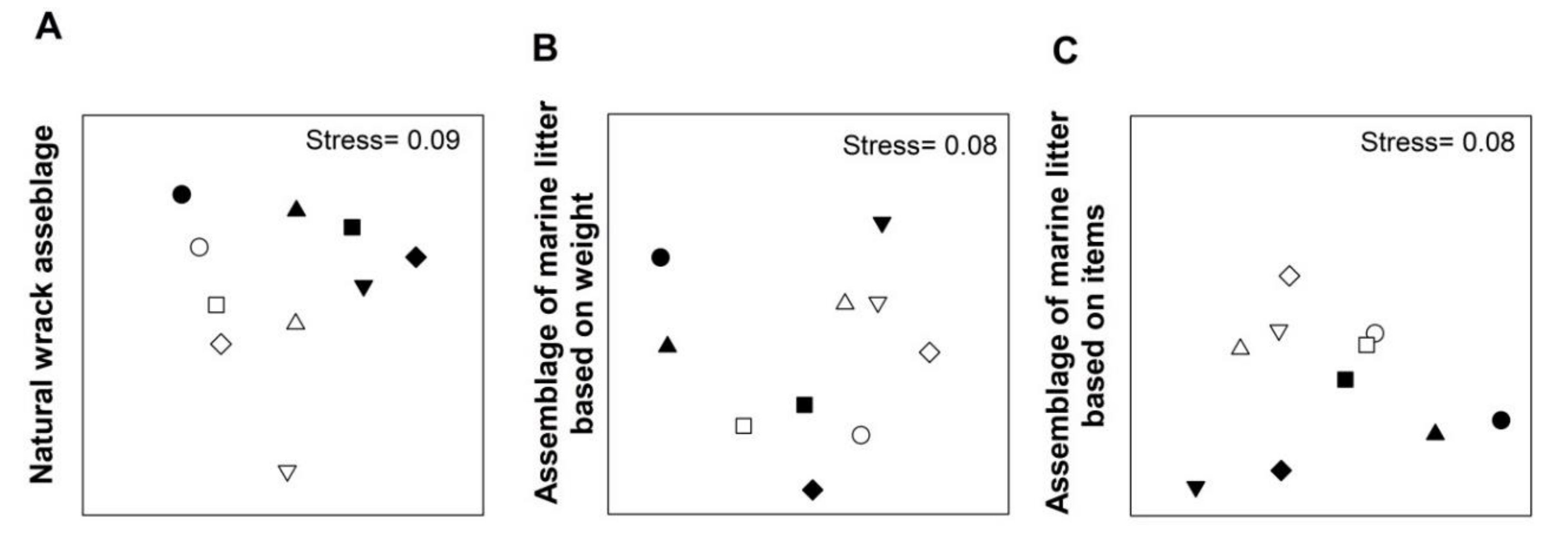

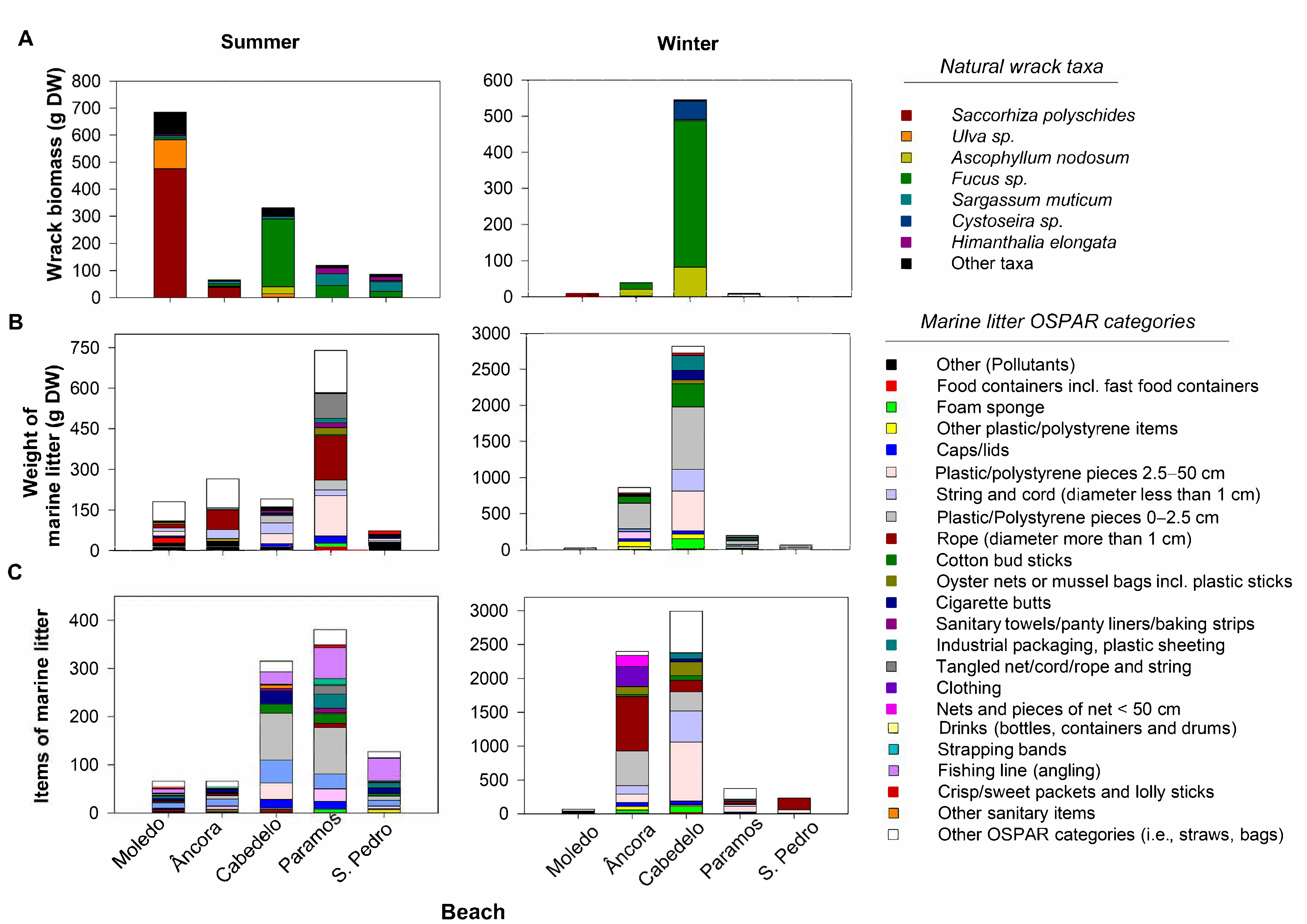

3.1. Composition and Quantification of the Natural Wrack

3.2. Marine Litter

3.2.1. Percentage of Abundance of the Marine Litter Materials and Diversity of OSPAR Categories

3.2.2. Weight of Marine Litter

3.2.3. Items of Marine Litter

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bustamante, R.H.; Branch, G.M.; Eekhout, S. Maintenance of an exceptional intertidal grazer biomass in South Africa: Subsidy by Subtidal Kelps. Ecology 1995, 76, 2314–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggins, D.O.; Simenstad, C.A.; Estes, J.A. Magnification of secondary production by kelp detritus in coastal marine ecosystems. Science 1989, 245, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, J.E.; Hubbard, D.M.; McCrary, M.D.; Pierson, M.O. The response of macrofauna communities and shorebirds to macrophyte wrack subsidies on exposed sandy beaches of southern California. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2003, 58, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra, M.; Rodil, I.F.; Sánchez-Mata, A.; García-Gallego, M.; Mora, J. Fate and processing of macroalgal wrack subsidies in beaches of Deception Island, Antarctic Peninsula. J. Sea Res. 2014, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, C.; Fanelli, G.; Filpa, A.; Cerfolli, F. Giant Reed (Arundo donax) wrack as sink for plastic beach litter: First evidence and implication. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 155, 111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchfield, S.G.; Schulz, K.G.; Kelaher, B.P. The influence of plastic pollution and ocean change on detrital decomposition. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP/MAP Assessment of the Status of Marine Litter, in the Mediterranean; UNEP/Earthprint: Athens, Grece, 2011.

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Cózar, A.; Gimenez, B.C.G.; Barros, T.L.; Kershaw, P.J.; Guilhermino, L. Macroplastics Pollution in the Marine Environment, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128050521. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Devriese, L.; Galgani, F.; Robbens, J.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics in sediments: A review of techniques, occurrence and effects. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 111, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, C.; Estarellas, F.; Deudero, S. Microplastics in the Mediterranean sea: Deposition in coastal shallow sediments, spatial variation and preferential grain size. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 115, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Tudor, D. Litter burial and exhumation: Spatial and temporal distribution on a cobble pocket beach. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001, 42, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusui, T.; Noda, M. International survey on the distribution of stranded and buried litter on beaches along the Sea of Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 47, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Bravo Rebolledo , E.L.; van Franeker, J.A. Deleterious effects of litter on marine life. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar, J.L.; Gamboa, R.L.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M.D. Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 6, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Guidance. In United Nations Environment Programme Mediterranean Action Plan, Proceedings of the 19th Ordinary Meeting of the Contracting Parties to the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean and Its Protocols, Athens, Greece, 9–12 February 2016; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; pp. 93–94.

- Papadopoulou, N. Seabed marine litter, comparison of 4 Aegean trawling grounds. In Proceedings of the 11th Panhellenic Symposium on Oceanography and Fisheries, Mytilene, Greece, 13–17 May 2015; pp. 2013–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheshire, A.; Adler, E.; Barbière, J.; Cohen, Y.; Evans, S.; Jarayabhand, S.; Jeftic, Lj.; Jung, R.-T.; Kinsey, S.; Kusui, T.; et al. UNEP/IOC Guidelines on Survey and Monitoring of Marine Litter. In UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies, No. 186; IOC Technical Series No. 83; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; pp. 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- GESAMP Guidelines for the monitoring and assessment of plastic litter in the ocean. Rep. Stud. 2019, 99, 130.

- Chubarenko, I.; Stepanova, N. Microplastics in sea coastal zone: Lessons learned from the Baltic amber. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 224, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poeta, G.; Conti, L.; Malavasi, M.; Battisti, C.; Acosta, A.T.R. Beach litter occurrence in sandy littorals: The potential role of urban areas, rivers and beach users in central Italy. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 181, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Hinojosa, I.A.; Miranda, L.; Pantoja, J.F.; Rivadeneira, M.M.; Vásquez, N. Anthropogenic marine debris in the coastal environment: A multi-year comparison between coastal waters and local shores. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 71, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.E.; Stieve, E.; Valiela, I.; Hauxwell, J.; McClelland, J. Macrophyte abundance in Waquoit Bay: Effects of land-derived nitrogen loads on seasonal and multi-year biomass patterns. Estuar. Coast. 2008, 31, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochieng, C.A.; Erftemeijer, P.L.A. Accumulation of seagrass beach cast along the Kenyan coast: A quantitative assessment. Aquat. Bot. 1999, 65, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piriz, M.L.; Eyras, M.C.; Rostagno, C.M. Changes in biomass and botanical composition of beach-cast seaweeds in a disturbed coastal area from Argentine Patagonia. J. Appl. Phycol. 2003, 15, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Dias, A.; Melo, R.A. Long-term abundance patterns of macroalgae in relation to environmental variables in the Tagus Estuary (Portugal). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 76, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baring, R.J.; Fairweather, P.G.; Lester, R.E. Nearshore drift dynamics of natural versus artificial seagrass wrack. Estuar. Coast.Shelf Sci. 2018, 202, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, A.; Brown, A. Ecology of Sandy Shores; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, M.; Zimmer, M.; Jelinski, D.E.; Mews, M. Wrack deposition on different beach types: Spatial and temporal variation in the pattern of subsidy. Ecology 2005, 86, 1496–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OSPAR Guideline for monitoring marine litter on the beachs in the OSPAR Maritime Area. OSPAR Comm. 2010, 1, 84.

- Emery, K.O. A simple method of measuring beach profiles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1961, 6, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, A.J. Experiments in Ecology: Their Logical Design and Interpretation Using Analysis of Variance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.J. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001, 26, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Distance-based tests for homogeneity of multivariate dispersions. Biometrics 2006, 62, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Austral Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerfield, P.; Clarke, K. Taxonomic levels, in marine community studies, revisited. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1995, 127, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsgard, F.; Somerfield, P.; Carr, M. Relationships between taxonomic resolution and data transformations in analyses of a macrobenthic community along an established pollution gradient. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 149, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mews, M.; Zimmer, M.; Jelinski, D. Species-specific decomposition rates of beach-cast wrack in Barkley Sound, British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 328, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J.; Kraak, M.H.S.; Parsons, J.R. Plastics in the Marine Environment: The Dark Side of a Modern Gift; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gago, J.; Lahuerta, F.; Antelo, P. Characteristics (abundance, type and origin) of beach litter on the Galician coast (NW Spain) from 2001 to 2010. Sci. Mar. 2014, 78, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, C.; Ventura, M.A.; Martins, A.; Cunha, R.T. Beach debris in the Azores (NE Atlantic): Faial Island as a first case study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biskup, S.; Bertocci, I.; Arenas, F.; Tuya, F. Functional responses of juvenile kelps, Laminaria ochroleuca and Saccorhiza polyschides, to increasing temperatures. Aquat. Bot. 2014, 113, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.G.; Ramos, L. A model for the estimation of annual production rates of macrophyte algae. Aquat. Bot. 1989, 33, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solidoro, C.; Brando, V.; Dejak, C.; Franco, D.; Pastres, R.; Pecenik, G. Long term simulations of population dynamics of Ulvar. in the lagoon of Venice. Ecol. Model. 1997, 102, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plus, M.; Auby, I.; Verlaque, M.; Levavasseur, G. Seasonal variations in photosynthetic irradiance response curves of macrophytes from a Mediterranean coastal lagoon. Aquat. Bot. 2005, 81, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, M.; Borum, J. Nutrient control of algal growth in estuarine waters. Nutrient limitation and the importance of nitrogen requirements and nitrogen storage among phytoplankton and species of macroalgae. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 142, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C. The retreat of large brown seaweeds on the north coast of Spain: The case of Saccorhiza polyschides. Eur. J. Phycol. 2011, 46, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.; Pato, L.S.; Rico, J.M. Nutrient uptake and growth responses of three intertidal macroalgae with perennial, opportunistic and summer-annual strategies. Aquat. Bot. 2012, 96, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, F.; Gómez, M.; Lastra, M.; López, J.; De La Huz, R. Annual cycle of wrack supply to sandy beaches: Effect of the physical environment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 433, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, F.; Gómez, M.; López, J.; Lastra, M.; de la Huz, R. Coupling between macroalgal inputs and nutrients outcrop in exposed sandy beaches. Hydrobiologia 2013, 700, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.; Barreiro, F.; López, J.; Lastra, M.; de la Huz, R. Deposition patterns of algal wrack species on estuarine beaches. Aquat. Bot. 2013, 105, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabarria, C.; Lastra, M.; Garrido, J. Succession of macrofauna on macroalgal wrack of an exposed sandy beach: Effects of patch size and site. Mar. Environ. Res. 2007, 63, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, F.; Fernández, C. Size structure and dynamics in a population of Sargassum muticum (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, N.; Frias, J.P.G.L.; Rodríguez, Y.; Carriço, R.; Garcia, S.M.; Juliano, M.; Pham, C.K. Spatio-temporal variability of beached macro-litter on remote islands of the North Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, S.; Gestoso, I.; Herrera, A.; Riera, L.; Canning-Clode, J. A comprehensive first baseline for marine litter characterization in the Madeira Archipelago (NE Atlantic). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio-Montesinos, F.; Anfuso, G.; Ramírez, M.O.; Smolka, R.; Sanabria, J.G.; Enríquez, A.F.; Arenas, P.; Bedoya, A.M. Beach litter composition and distribution on the Atlantic coast of Cádiz (SW Spain). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 34, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, B.K.; Gilardi, K.V.K.; Gulland, F.M.; Higgins, A.; Holcomb, J.B.; Leger, J.S.; Ziccardi, M.H. Fishing gear–related injury in california marine wildlife. J. Wildl. Dis. 2009, 45, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Bravo, M.; Hinojosa, I.A.; Luna, G.; Miranda, L.; Núñez, P.; Pacheco, A.S.; Vásquez, N. Anthropogenic litter in the SE Pacific: An overview of the problem and possible solutions. Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada 2011, 11, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.T.; Pond, K.; Ergin, A.; Cullis, M.J. The Hazards of Beach Litter; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 753–780. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PlasticsEurope. Plastics—The Facts 2017. An Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data; Plastics Europe: Wemmel, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, J.E.; Hubbard, D.M.; Page, H.M.; Schimel, J.P. Marine macrophyte wrack inputs and dissolved nutrients in beach sands. Estuaries Coasts 2011, 34, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Bishop, M.; Kelaher, B.; Glasby, T. Impacts of detritus from the invasive alga Caulerpa taxifolia on a soft sediment community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 420, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, A.; Ungherese, G.; Ciofini, M.; Lapucci, A.; Camaiti, M. Microplastic debris in sandhoppers. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2013, 129, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannilli, V.; Di Gennaro, A.; Lecce, F.; Sighicelli, M.; Falconieri, M.; Pietrelli, L.; Poeta, G.; Battisti, C. Microplastics in Talitrus saltator (Crustacea, Amphipoda): New evidence of ingestion from natural contexts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 28725–28729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, R.; Hyndes, G.A.; Lavery, P.S.; Vanderklift, M.A. Marine macrophytes directly enhance abundances of sandy beach fauna through provision of food and habitat. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2007, 74, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerman, J.W.; Potts, G.E. Analysis of metals leached from smoked cigarette litter. Tob. Control 2011, 20, i30–i35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.C.P.; Ivar do Sul, J.A.; Costa, M.F. Plastic pollution in islands of the Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.D.A. Marine debris: A proximate threat to marine sustainability in Bootless Bay, Papua New Guinea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 1880–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oigman-Pszczol, S.S.; Creed, J.C. Quantification and classification of marine litter on beaches along Armação dos Búzios, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Coast. Res. 2007, 23, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, M.; de los Ángeles Gallardo, M.; Luna-Jorquera, G.; Núñez, P.; Vásquez, N.; Thiel, M. Anthropogenic debris on beaches in the SE Pacific (Chile): Results from a national survey supported by volunteers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.O.; Abrantes, N.; Gonçalves, F.J.M.; Nogueira, H.; Marques, J.C.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Spatial and temporal distribution of microplastics in water and sediments of a freshwater system (Antuã River, Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Gago, J.; Otero, V.; Sobral, P. Microplastics in coastal sediments from Southern Portuguese shelf waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 114, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Monteiro, P.; Bentes, L.; Henriques, N.S.; Aguilar, R.; Gonçalves, J.M.S. Marine litter in the upper São Vicente submarine canyon (SW Portugal): Abundance, distribution, composition and fauna interactions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 97, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, D.; Sobral, P.; Pereira, T. Marine litter in bottom trawls off the Portuguese coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 99, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Y.; Pham, C.K. Marine litter on the seafloor of the Faial-Pico Passage, Azores Archipelago. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Two-Way ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | DF | MS | F | p-Value | |

| Natural Wrack Biomass | Beach (B) | 4 | 8.315 | 1.2 | 0.433 |

| *Ln(x + 1) transformed | Date (D) | 1 | 29.4 | 46.75 | 0.001 |

| B x D | 4 | 6.954 | 11.06 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 20 | 0.629 | |||

| Natural Wrack Diversity | Beach (B) | 4 | 38.03 | 0.41 | 0.793 |

| Date (D) | 1 | 496.1 | 58.6 | 0.001 | |

| B x D | 4 | 91.97 | 10.86 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 20 | 8.467 | |||

| Marine Litter Diversity | Beach (B) | 4 | 222.5 | 1.56 | 0.339 |

| Date (D) | 1 | 0 | 0 | F = 0 | |

| B x D | 4 | 142.8 | 8.69 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 20 | 16.43 | |||

| Weight of Marine Litter | Beach (B) | 4 | 9.538 | 1.73 | 0.305 |

| *Ln(x) transformed | Date (D) | 1 | 3.053 | 2.24 | 0.15 |

| B x D | 4 | 5.518 | 4.05 | 0.015 | |

| Residual | 20 | 1.363 | |||

| No. of Items of Marine Litter | Beach (B) | 4 | 8.317 | 2 | 0.259 |

| *Ln(x) transformed | Date (D) | 1 | 1.835 | 8.77 | 0.008 |

| B x D | 4 | 4.155 | 19.85 | 0.001 | |

| Residual | 20 | 0.209 | |||

| Natural Wrack Assemblage | Marine Litter Assemblage Based on Weight | Marine Litter Assemblage Based on Items | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of Variation | d.f. | MS | F | P | MS | F | P | MS | F | P |

| Beach (B) | 4 | 9156 | 1.59 | 0.114 | 6301 | 1.26 | 0.212 | 7464 | 1.29 | 0.266 |

| Date (D) | 1 | 17,574 | 14.77 | 0.001 | 7280 | 2.44 | 0.004 | 11,369 | 8.91 | 0.001 |

| B × D | 4 | 5771 | 4.85 | 0.001 | 5017 | 1.68 | 0.002 | 5797.9 | 4.55 | 0.001 |

| Residual | 20 | 1190 | 2985 | 1275.7 | ||||||

| Variable | Date | Beach | Moledo | Âncora | Cabedelo | Paramos | São Pedro de Maceda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assemblage of natural wrack biomass | Summer | Moledo | 1 | 0.035 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.06 | 0.128 | 0.095 | |||

| Cabedelo | 1 | 0.051 | 0.018 | ||||

| Paramos | 1 | 0.237 | |||||

| São Pedro de Maceda | 1 | ||||||

| Winter | Moledo | 1 | 0.041 | 0.014 | 0.167 | 0.363 | |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.007 | 0.113 | 0.002 | |||

| Cabedelo | 1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Paramos | 1 | 0.028 | |||||

| São Pedro de Maceda | 1 | ||||||

| Assemblage of marine litter based on weight | Summer | Moledo | 1 | 0.383 | 0.138 | 0.099 | 0.271 |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.125 | 0.08 | 0.268 | |||

| Cabedelo | 1 | 0.038 | 0.177 | ||||

| Paramos | 1 | 0.046 | |||||

| São Pedro de Maceda | 1 | ||||||

| Winter | Moledo | 1 | 0.051 | 0.042 | 0.081 | 0.153 | |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.33 | 0.091 | 0.038 | |||

| Cabedelo | 1 | 0.05 | 0.021 | ||||

| Paramos | 1 | 0.147 | |||||

| São Pedro de Maceda | 1 | ||||||

| Assemblage of marine litter based on items | Summer | Moledo | 1 | 0.25 | 0.098 | 0.057 | 0.205 |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.041 | |||

| Cabedelo | 1 | 0.087 | 0.032 | ||||

| Paramos | 1 | 0.027 | |||||

| São Pedro de Maceda | 1 | ||||||

| Winter | Moledo | 1 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.035 | |

| Âncora | 1 | 0.049 | 0.036 | 0.004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerrero-Meseguer, L.; Veiga, P.; Rubal, M. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Anthropogenic and Natural Wrack Accumulations along the Driftline: Marine Litter Overcomes Wrack in the Northern Sandy Beaches of Portugal. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8120966

Guerrero-Meseguer L, Veiga P, Rubal M. Spatio-Temporal Variability of Anthropogenic and Natural Wrack Accumulations along the Driftline: Marine Litter Overcomes Wrack in the Northern Sandy Beaches of Portugal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2020; 8(12):966. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8120966

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerrero-Meseguer, Laura, Puri Veiga, and Marcos Rubal. 2020. "Spatio-Temporal Variability of Anthropogenic and Natural Wrack Accumulations along the Driftline: Marine Litter Overcomes Wrack in the Northern Sandy Beaches of Portugal" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 8, no. 12: 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8120966

APA StyleGuerrero-Meseguer, L., Veiga, P., & Rubal, M. (2020). Spatio-Temporal Variability of Anthropogenic and Natural Wrack Accumulations along the Driftline: Marine Litter Overcomes Wrack in the Northern Sandy Beaches of Portugal. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 8(12), 966. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse8120966