1. Introduction

Drag embedment anchors (DEAs) are anchors that generate holding capacity by embedding into the seabed under tension. DEAs represent a revolutionary development in maritime mooring technology, evolving significantly since their inception in the early 20th century. Traditional anchors relied primarily on weight, but the introduction of the first modern DEA, the Danforth anchor, in 1939, marked a paradigm shift toward designs that penetrate and embed themselves into the seabed. This innovation dramatically improved holding power-to-weight ratios compared to conventional anchors.

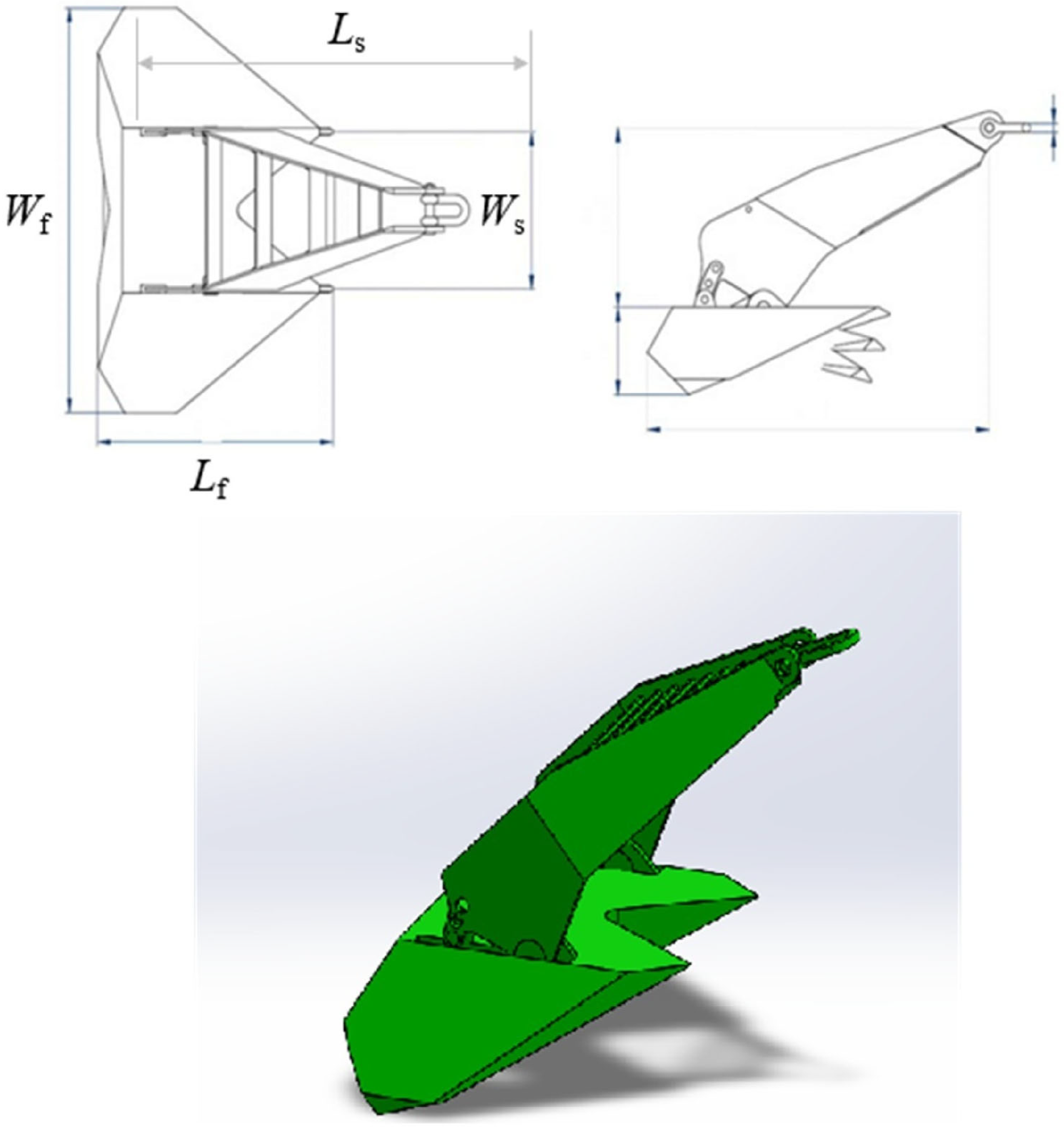

Figure 1 represents the schematic layout of the drag embedment anchor (DEA). In this figure,

Ls,

Lf,

Ws, and

Wf are shank length, fluke length, shank width, and fluke width.

The energy crisis of the 1970s accelerated drag embedment anchor (DEA) development as offshore oil and gas installations required more reliable mooring solutions, leading to specialized designs. The practical advantages of DEAs are substantial: they deliver exceptional holding capacity despite being relatively lightweight, making them ideal for vessels and structures where weight considerations are critical. Their self-burying design allows them to achieve greater stability in various seabed conditions by penetrating deeper under tension, which is particularly valuable during storms or strong currents. Modern DEAs incorporate sophisticated fluke angles, shank designs, and stabilizers that optimize performance in specific substrate types, from soft mud to dense sand. These anchors have revolutionized temporary and permanent offshore mooring capabilities, enabling exploration and resource extraction in increasingly challenging deep-water environments. The economics of DEAs are particularly compelling; their installation requires smaller support vessels and less handling equipment than gravity-based systems, while their retrievable nature makes them environmentally preferable and cost-effective for temporary installations [

1]. Neubecker and Randolph [

2] developed the fundamentals to enable economic offshore operations in water depths exceeding 1000 m, where traditional mooring solutions would be prohibitively expensive. Lai et al. [

3] conducted a numerical analysis of the load–displacement behavior of drag embedment anchors in clay using the finite element method. The study considered different anchor geometries, soil properties, and load angles. The authors validated the numerical results with analytical solutions and experimental data. Maitra et al. [

4] utilized large-deformation finite element (LDFE) analysis to simulate the installation trajectory of drag-in plate anchors in clay. The research emphasized the importance of accounting for soil remolding around both the anchor and the installation line, as well as the effects of anchor padeye position and seabed conditions on installation response. Fanning et al. [

5] investigated the pullout capacity of single- and bi-wing anchors in a soft clay deposit using model tests in centrifuge and finite element method (FEM) predictions. The study conducted centrifuge tests on single- and bi-wing anchors with different wing angles, wing lengths, and embedment depths. It also performed FEM simulations using ABAQUS software (version not specified) to model the anchor–soil interaction and the soil failure mechanism, compare the results of the centrifuge tests and the FEM simulations, and evaluate the effects of different parameters on the pullout capacity of the anchors. The authors found that the bi-wing anchors have higher pullout capacity than the single anchors for the same embedment depth and wing length. The study highlighted that the pullout capacity increases with increasing wing angle, wing length, and embedment depth. It concluded that the FEM simulations could provide reasonable predictions of the pullout capacity of single- and bi-wing anchors in soft clay and could be used as a design tool for offshore anchoring systems. Using magnetometer technology, Chen et al. [

6] examined how drag embedment anchors move through clay soil across all spatial dimensions. Their research evaluated factors including the angle between the anchor’s fluke and shank, starting burial depth, mooring line diameter, deployment orientation, and the speed of applied force, revealing how anchors travel and rotate as they penetrate the seabed. Hossain et al. [

7] explored the potential of converting decommissioned subsea flowlines into dynamically installed anchors. Tests assessed free-fall trajectory, terminal velocity, and drag coefficient in water, as well as tip embedment depth and capacity under vertical loading in clay, demonstrating comparable performance to conventional anchors. Olsen [

8] presented a comprehensive analytical methodology for optimizing drag anchor design in offshore mooring systems. By synthesizing field data with laboratory testing, the research established mathematical models that predicted anchor trajectory and ultimate holding capacity across varied seabed conditions. The proposed design procedure incorporated critical parameters, including fluke angle, shank configuration, and soil characteristics, to determine optimal embedment depth and load resistance. Results demonstrated significantly improved predictive accuracy compared to traditional empirical methods, with validation across multiple anchor types. The authors recommended a standardized five-step design protocol that enhanced safety margins while reducing material requirements and installation costs.

Despite extensive experimental, numerical, and analytical investigations into the performance of DEAs in clay seabed, a critical knowledge gap persists in leveraging advanced machine learning (ML) techniques to predict their holding capacity and efficiency. While traditional methods, including centrifuge testing [

2], finite element analysis [

9], and limit equilibrium frameworks [

10], have provided valuable insights, they often face limitations in scalability, computational cost, and adaptability to heterogeneous seabed conditions.

Recent years have seen a rapid increase in data-driven approaches for foundation and offshore foundation problems. Deep learning and ensemble methods have been applied successfully to predict suction-caisson load–deflection responses and provide fast surrogate models for design (e.g., Yin et al., [

11]). Similarly, multi-fidelity and data-fusion approaches have been developed to combine numerical models and sparse experimental data for suction-caisson stiffness estimation in layered soils (Suryasentana et al., [

12]). In the pile and monopile domain, several recent studies demonstrate that ML-based surrogates and hybrid neural networks can accelerate concept design and capture complex, nonlinear soil–structure interactions (e.g., Ozturk [

13]; Taherkhani et al., [

14]; Alexander et al., [

15]). These advances illustrate that ML is maturing from proof-of-concept studies to practical surrogate models for foundation engineering.

Drag embedment anchors, though traditionally used in offshore oil and gas, are directly applicable to floating offshore wind farms, where compliant mooring systems are required to maintain station keeping under combined environmental loads. Floating wind turbines commonly use drag anchors, suction caissons, or hybrid systems that share similar soil–structure interaction mechanisms in clay, including embedment behavior, load transfer, and long-term capacity. Therefore, the machine learning framework developed in this study provides a foundation-level contribution relevant to offshore wind engineering, supporting efficient design and uncertainty assessment. Although the analysis focuses on static performance, the approach is readily extendable to cyclic loading, installation effects, and long-term stability, as it relies on the same governing geotechnical parameters. The resulting surrogate models are well-suited for early-stage design, probabilistic analyses, and reliability-based assessments of floating offshore wind infrastructure. For instance, He et al. [

16] predicted pile running during offshore pile installation using a deep learning (DL) method. A dataset of pile installation records from various construction sites was used to train and test the DL model. The predictive performance of the DL model was evaluated against conventional analytical methods and was shown to be more accurate and robust. Additionally, the SHAP method was applied for sensitivity analysis of input variables, which supported a reliable interpretation of model results. Quevedo–Reina et al. [

17] investigated how soil–structure interaction (SSI) influenced the optimization of jacket foundations for offshore wind turbines. An optimization process was conducted for a 10 MW turbine at a specific site using static equivalent structural analysis with representative environmental loads. Designs obtained with and without SSI were compared, revealing that foundation flexibility significantly affected structural response and technical requirements, especially in ultimate limit states. Results showed that SSI altered internal force distribution and utilization factors, indicating it should be included in jacket design. Lee et al. [

18] assessed the bearing capacity of suction anchors in clay under monotonic and cyclic inclined pullout loads using centrifuge model tests. Suction anchor models were loaded at 40° inclination, and cyclic tests with 50 and 100% of target capacity were performed, followed by monotonic pullout tests. Results showed that monotonic capacities matched analytical and numerical predictions, and post-cyclic monotonic capacity was higher than pure monotonic capacity, due to reduced excess pore pressure after cyclic loading, indicating enhanced anchor performance.

A concurrent trend is the integration of physics into machine learning. Physics-informed and multi-fidelity frameworks (PINN/PIML) embed governing equations or lower-fidelity physics models into the learning process to improve extrapolation and enforce physically consistent behavior, an approach shown to increase robustness in geotechnical applications (recent reviews and direction papers summarize these developments and challenges). While PINN-type approaches promise better generalization and constrained extrapolation, practical application often requires well-posed physics- and site-specific data; consequently, many foundation surrogate studies continue to use data-driven DNN or ensemble methods as effective engineering surrogates when physics constraints are difficult to enforce directly.

To bridge this gap, this study introduces tree-based machine learning algorithms, specifically decision tree regression (DTR) and random forest regression (RFR), as robust tools for predicting DEA performance in clay. Unlike conventional approaches, ML algorithms excel at capturing nonlinear soil–anchor interactions, high-dimensional parameter spaces, and uncertainty in geotechnical properties, while offering computational efficiency and predictive accuracy. Clay seabed exhibits spatially variable shear strength, strain-softening behavior, and rate-dependent responses, which are factors that challenge traditional models but are well-suited for ML’s pattern-recognition capabilities. By training on diverse datasets (e.g., embedment depth, fluke geometry, soil properties), ML models identify dominant parameters and their interdependencies. RFR’s ensemble approach reduces overfitting and improves generalization, which are critical for extrapolating results to untested seabed conditions. This research fills a critical void in DEA literature by harnessing ML to address the complexities of clay seabed; it is a step toward smarter, more resilient mooring systems for offshore energy infrastructure.

While the machine learning algorithms themselves (DTR and RFR) are established, novelty in geotechnical ML lies in problem formulation, dataset harmonization, and physically interpretable deployment, rather than algorithmic invention alone. The study contributes novelty in three domain-specific aspects already stated but can be more explicitly emphasized:

Tree-based ML framework dedicated to drag embedment anchors in clay: Previous DEA studies rely on empirical, analytical, or FEM/LDFE approaches. No prior work has systematically applied ensemble tree models to both holding capacity and anchoring efficiency for DEAs in cohesive soils.

Harmonized multi-source experimental dataset: The study integrates centrifuge, laboratory, and analytical datasets from multiple classical sources (Stewart; Dunnavant and Kwan; Aubeny et al.), explicitly encoding strength gradients (K), local undrained strength (Su), and geometry variables into a unified ML-ready structure.

Physically interpretable sensitivity analysis tailored to geotechnical design: Rather than presenting ML as a black box, the study uses feature-dropping analysis to map statistical importance to known anchor–soil mechanisms, explicitly acknowledging collinearity and scale effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Decision Tree Regression (DTR)

Decision trees enable machine learning through a non-parametric approach where supervised learning algorithms classify and assign labels to input data. These trees have a structured hierarchy featuring internal nodes, connecting branches, and terminal leaf nodes. The methodology works by splitting data into two groups using specific characteristics known as features for categorization purposes. Machine learning performance can be evaluated by calculating entropy measurements.

The tree data structure comprises interconnected nodes and branches, with each node functioning as a decision tree capable of handling both classification and regression tasks. Key components include a root node positioned at the tree’s apex, intermediate nodes, connecting branches, and terminal nodes that hold classification labels. Non-terminal nodes serve as internal decision points linked through branches. In this research, mean squared error was employed as the fitness metric to optimize the decision tree algorithm’s performance [

11].

2.2. Random Forest Regression (RFR)

Random forest represents a powerful ensemble machine learning method applicable to classification and regression problems [

19,

20]. Building upon the CART (classification and regression tree) framework, it overcomes CART’s primary weakness: the tendency to overfit training data. Random forest demonstrates superior resistance to overfitting compared to CART, making it a more dependable prediction method [

19].

The technique operates by creating numerous decision trees whose predictions are merged through a voting process. This aggregation of individual tree forecasts enhances prediction accuracy. For regression problems, the method expands the quantity of trees generated from random vectors while handling both inputs and outputs as numerical values. Each tree develops independently using the training data, with the approach computing mean squared generalization error from the collective ensemble [

21].

Performance optimization involves incorporating weighted correlation between prediction errors and the randomization process, which decreases average inaccuracies. Additionally, the method utilizes bootstrap sampling—creating multiple resampled datasets from the source data—which addresses missing information and strengthens individual tree quality [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

In summary, random forest overcomes CART’s overfitting weakness, delivering more trustworthy predictions. Its approach of building multiple decision trees combined with a voting system produces accurate results, while weighted correlation and bootstrap resampling reduce errors and enhance overall performance.

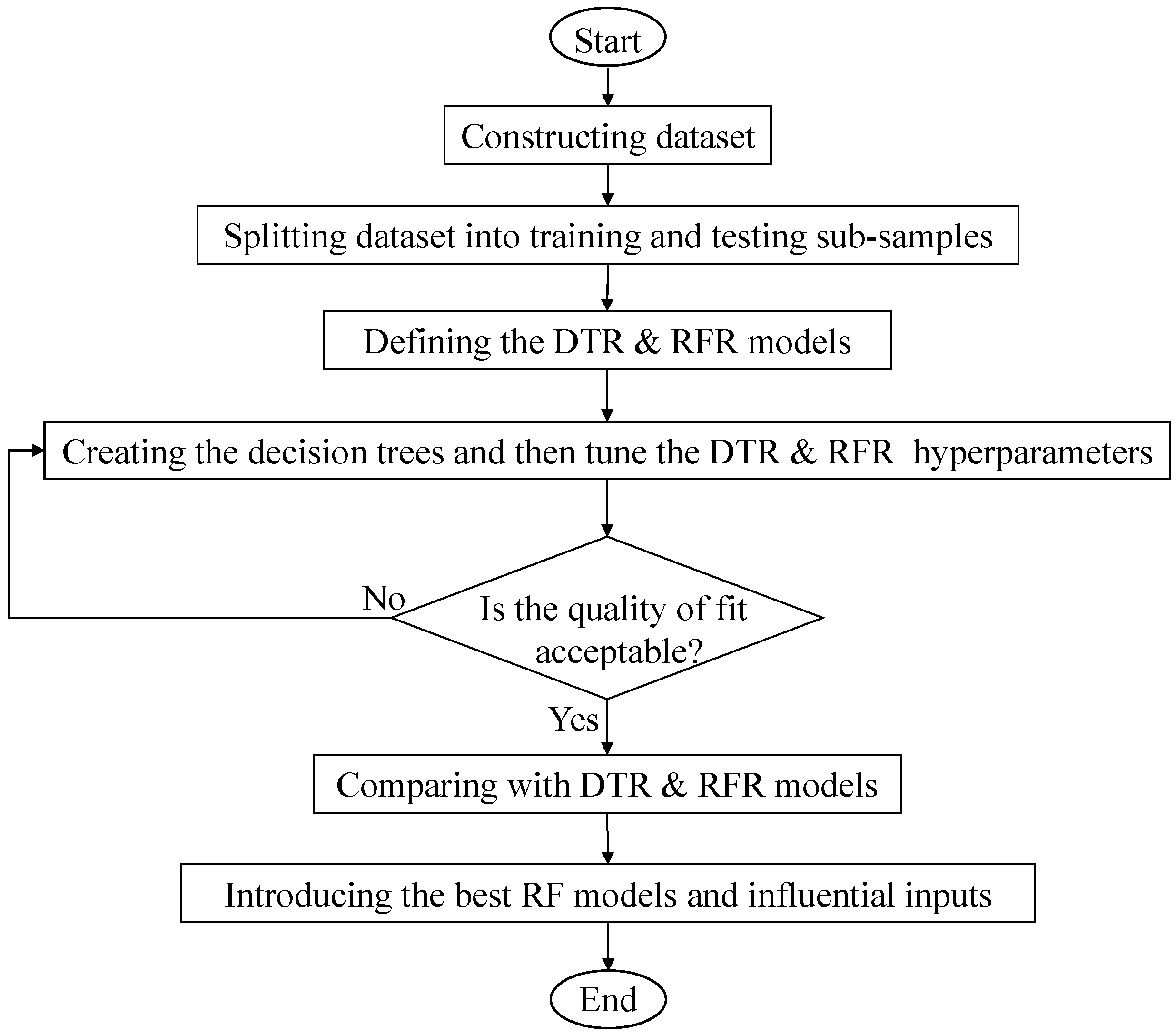

Figure 2 depicts the procedural framework for forecasting DEA performance through machine learning approaches, merging computational and geotechnical engineering viewpoints. The workflow started with data acquisition, consisting of compiling essential anchor and soil characteristics, including fluke–shank angle (α), soil strength (ϕ), burial depth, and additional geometric and geotechnical attributes. Data preprocessing was followed to guarantee quality and uniformity, encompassing standardization, anomaly elimination, and managing incomplete entries. Correlation analysis was subsequently applied for variable selection, determining the most impactful input parameters affecting DEA capacity and performance. The processed dataset was partitioned into training and testing portions, and two ML approaches, decision tree regression (DTR) and random forest regression (RFR), were constructed and trained. Model effectiveness was measured through statistical indicators to evaluate prediction precision, with validation confirming the models’ applicability to new data. Lastly, performance analysis incorporated evaluations and sensitivity studies to measure individual feature contributions, showing that RFR exceeded DTR performance and provided stable, dependable predictions. This procedural framework maintained rigorous scientific standards while facilitating practical ML implementation in offshore engineering applications.

2.3. Model Selection Rationale

Although neural networks (ANNs) and support vector machines (SVMs) are powerful nonlinear estimators, the dataset assembled in this study—derived from centrifuge tests, laboratory experiments, and analytically generated cases—contains a moderate number of observations and exhibits heterogeneous variable scaling (anchor geometry, soil parameters, and strength gradients). Under these conditions, tree-based ensemble models (DTR/RFR) offer several advantages that directly align with geotechnical engineering requirements:

ANN performance typically depends on large, high-quality datasets to avoid overfitting and to ensure stable optimization. SVMs similarly require dense and well-distributed feature spaces for reliable kernel-based generalization. In contrast, RFR performs strongly with limited samples, noisy measurements, or partially missing features, making it well-suited for DEA datasets where high-fidelity experimental data are scarce.

The input variables (e.g., fluke length, anchor weight, undrained shear strength, gradient K) span different units and magnitudes. ANNs and SVMs require strict normalization/standardization and can be sensitive to feature scaling.

Tree-based models are invariant to monotonic transformations, requiring far less preprocessing, which reduces the risk of introducing bias or scaling artifacts—an important consideration for geotechnical datasets that combine physical and geometric parameters.

Offshore geotechnical design demands transparent reasoning for safety-critical decisions. Tree-based models provide feature importance rankings, decision paths, and SHAP interpretability, enabling engineers to validate model logic against known soil–anchor mechanics. ANNs and SVMs act as “black boxes,” making it difficult to diagnose failure modes or justify predictions to certifying authorities.

DTR and especially RFR use bagging, bootstrapping, and random feature selection to reduce variance and stabilize predictions—an essential property when training data originate from different experimental programs and scales. ANNs, lacking strong built-in regularization in small datasets, can easily overfit without careful architecture tuning.

Despite being simpler than ANNs, RFRs capture higher-order nonlinearities through ensemble voting and feature interaction splits. This is particularly useful for DEA behavior, where anchor geometry, soil strength profile, and embedment trajectory interact in a nonlinear way.

RFRs achieve this with very few hyperparameters compared to ANN architectures that require tuning of depth, width, learning rate, batch strategy, and regularization.

Tree-based models train rapidly and deterministically on small datasets, making it practical to run K-fold cross-validation, hyperparameter sweeps, and sensitivity tests. ANN training, in contrast, is stochastic and computationally more expensive, potentially yielding variability in outcomes unless randomized seeds are tightly controlled.

Many recent ML studies for piles, caissons, and foundation performance (e.g., Ozturk [

13]; Yin et al. [

11]; Suryasentana et al. [

12]) include tree-based ensembles as strong baselines due to their proven stability and interpretability in geomechanically contexts. Therefore, using RFR is consistent with established practice in geotechnical ML.

For these reasons, DTR and RFR were selected as the primary algorithms in this study. They provide a good balance between accuracy, robustness, interpretability, and suitability for moderate-sized experimental DEA datasets, while still capturing the nonlinear interactions governing holding capacity. To confirm completeness, ANN and SVM baselines have been included in the Supplementary Analysis for comparison.

Hyperparameters were optimized using a try-and-error approach. The final hyperparameters used for the reported RFR and DTR models are as follows:

Decision tree regression (DTR): max_depth = 24, max_features = ‘auto’, max_leaf_nodes = 6, min_samples_leaf = 1, min_weight_fraction_leaf = 0.001, splitter = ‘random’.

Random forest regression (RFR): n_estimators = 100, max_depth = 10, min_samples_split = 10, min_samples_leaf = 5, random_state = 1.

2.4. Behavior of EDAs in Clay Seabed

Drag anchors behave distinctly in clay compared to sand environments. In clay, these anchors penetrate much deeper, resulting in localized soil failure around the anchors rather than the surface-extending failure patterns observed in sand. The geotechnical forces acting on anchors in clay can be calculated based on the local undrained soil shear strength. Notably, soil self-weight minimally affects anchor resistance, making anchor loads largely independent of orientation. For static analysis in clay, capacity calculations determine the forces on the anchor. These forces are calculated by multiplying the element area, local undrained shear strength, bearing capacity factor, and a calibration factor. Stewart’s dynamic analysis method simulates the anchor embedment process through two key assumptions: the anchor travels approximately parallel to the fluke (reasonable in undrained conditions where void formation is prevented), and the anchor rotates according to its net moment. Dunnavant and Kwan [

24] observed that flukes typically reach horizontal orientation at test completion, representing a stable configuration. Stewart’s approach enables complete embedment history simulation by calculating penetration and rotation for a given translation, with incremental motions followed by static analysis to reassess forces during embedding.

Current design approaches for predicting drag anchors’ holding capacity remain simplistic and lack rigor. Anchor manufacturers, with their proprietary test results and installation records, often dominate anchor design decisions for specific projects.

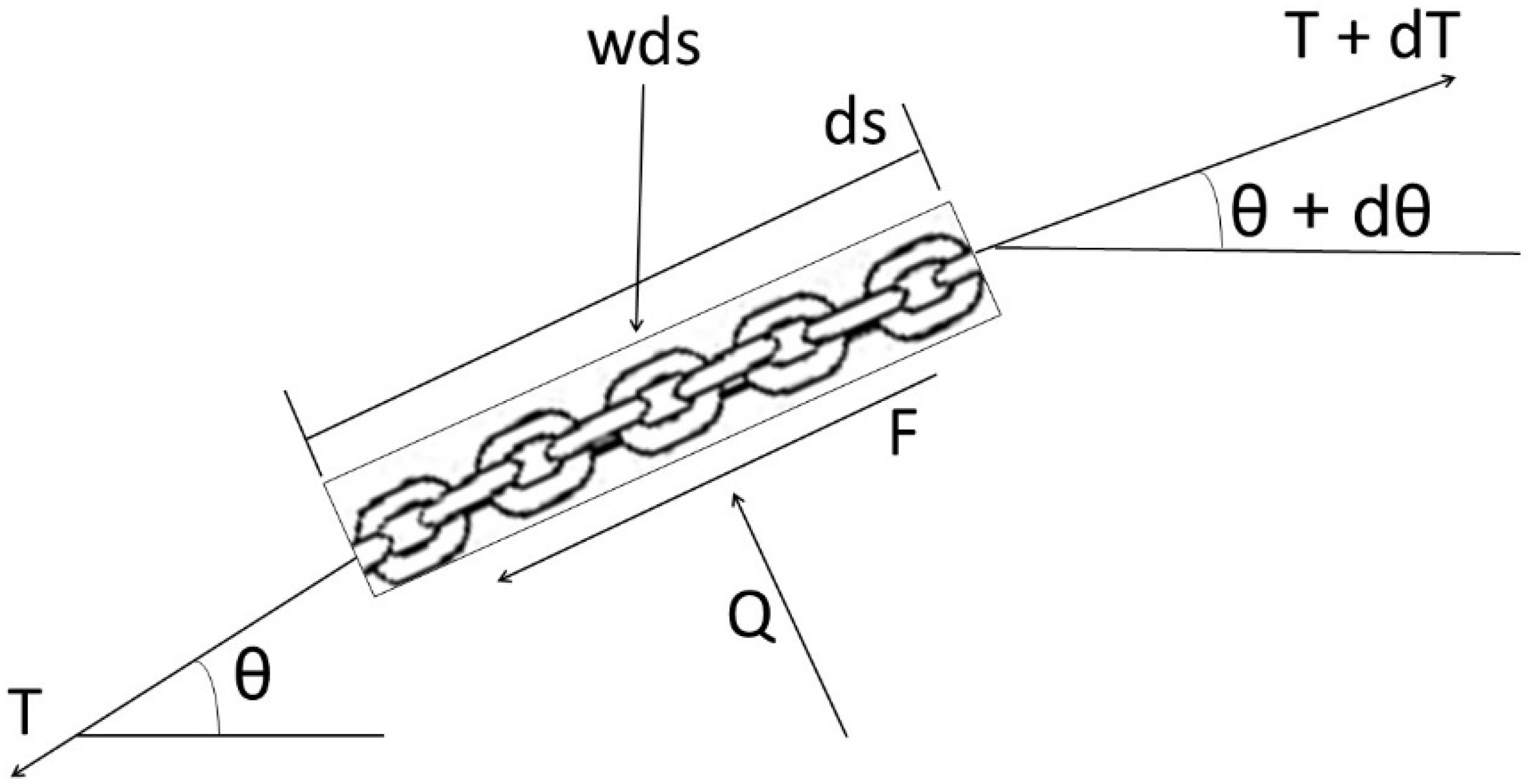

Figure 3 displays the equilibrium of forces acting on a chain segment buried within the soil.

The parameters on

Figure 3 are defined as follows:

T: chain tension at the left end of the element

T + dT: chain tension at the right end of the element

θ: inclination angle of the chain element

θ + dθ: inclination angle at the right end of the element

ds: infinitesimal length of the chain element

wds: submerged weight of the chain element over length ds

Q: Normal (bearing) reaction from the surrounding soil

F: tangential resistance/friction force exerted by the soil on the chain.

Chains play a crucial role in drag embedment anchors by transmitting tension from the mooring line to the anchor’s shank padeye. The maximum anchor holding capacity relies on contributions from both soil resistance and chain friction [

10], which substantially influence the system’s overall performance. To comprehend how the anchor moves during failure under particular chain-loading directions, examining the soil–chain interaction becomes necessary, accounting for both the chain’s frictional capacity and the connection point’s orientation. Neubecker [

25] formulated a streamlined analytical solution for this interaction, representing the balance between frictional force F and perpendicular soil reaction Q for chain sections embedded in the seabed.

Drag embedment anchor behavior in clay seabed is influenced by a variety of factors, including shear strength, consolidation properties, and pore water pressure. For accurate anchor capacity prediction, it is essential to understand these clay seabed characteristics.

Thus, based on extensive studies and industry standards in the field of drag anchors and their performance in clay soil, researchers have identified ten key parameters related to soil and anchors that significantly influence anchor capacity. These parameters, which serve as input data, include unit weight (γ′ in KN/m3), bearing capacity factor (Nc), shear stress gradient (K in Kpa/m), shear strength (Su in Kpa), fluke–shank angle (α in degrees), anchor weight (W in kg), fluke length (Lf in m), fluke width (bf in m), shank width (bs in m), and shank length (Ls in m). By incorporating these parameters into an Excel datasheet and utilizing established relationships and equations, researchers were able to determine and define the anchor’s capacity and efficiency as output data.

It is important to distinguish between the design for the ultimate holding capacity and the design for anchoring efficiency. Ultimate capacity in clay seabeds is primarily governed by the undrained shear strength (Su), which controls soil failure and resistance mobilization under peak loading. In contrast, anchoring efficiency, defined as the ratio of holding capacity to anchor weight, is more sensitive to effective stress conditions and is therefore influenced by the submerged unit weight of the soil (γ′) and related bearing capacity parameters. As a result, different soil and anchor properties may dominate depending on whether the design objective is maximizing absolute capacity or optimizing performance relative to anchor mass.

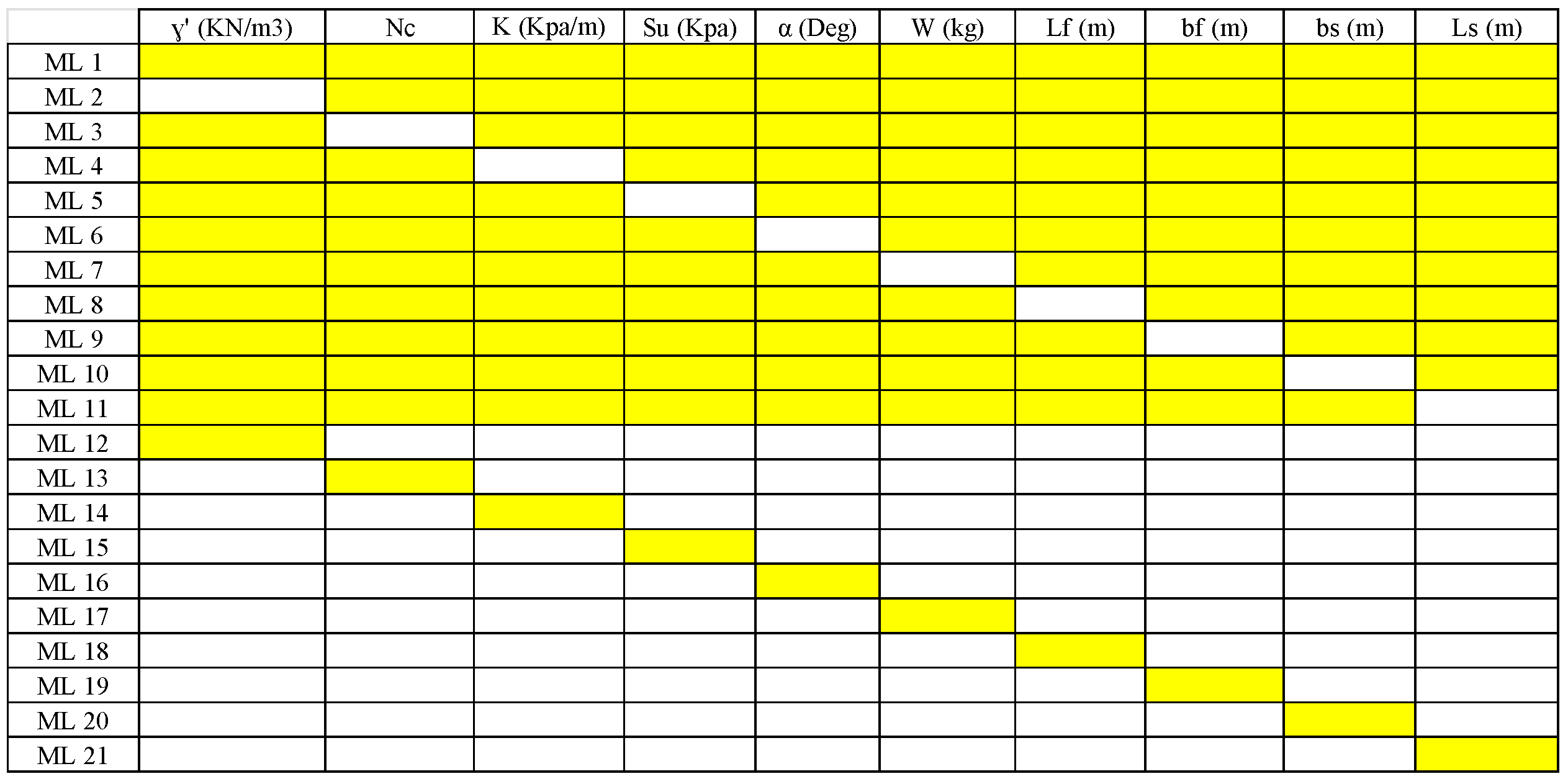

Twenty-one distinct models were developed using machine learning and decision tree methods to assess anchor capacity and performance based on the collected input data. An identical framework was applied when constructing the RFR models.

Figure 4 illustrates that the initial model (ML 1) included all eleven input parameters. However, for ML 2 to 11, a single input parameter was systematically removed in each iteration to identify the optimal model. Subsequently, ML 12 to 21 were analyzed with only one input parameter at a time, enabling the identification of the most influential parameters. In the present study, feature-dropping analysis was focused on, as the primary aim was to evaluate the relative contribution of geometry and soil parameters within the curated dataset. This method was considered appropriate for the dataset size and provided direct, model-agnostic insight into which variables most influenced the predictions.

2.5. Experimental Dataset

In the present study, the performance of the machine learning (ML) models developed to predict anchor capacity in clay seabeds was assessed through comparison with experimentally measured data. To ensure that the models were trained and validated on a comprehensive and representative dataset, experimental results from several well-established studies in the literature were incorporated. Specifically, data reported by Stewart [

26], Dunnavant and Kwan [

24], O’Neill et al. [

27], Thorne [

28], and Aubeny et al. [

9] were collected and synthesized to form the dataset used for analysis.

Table 1 shows the minimum, maximum, average, and standard deviation of the implemented experimental measurements for the clay seabed in the current study.

The total number of data points used in this study was 267 experimental measurements. The results presented in the manuscript correspond to the testing mode, which consisted of 20% of the entire dataset used for model validation. This clarification has been added to ensure transparency regarding the dataset size and the proportion allocated for model evaluation.

The experimental dataset includes both centrifuge and laboratory-scale tests, interpreted under standard centrifuge similitude assumptions to ensure stress-level equivalence and representative undrained soil behavior. While such datasets are inherently heterogeneous in scale and origin, tree-based machine learning models are well-suited to this context, as they do not require explicit functional forms or strict assumptions regarding variable independence, and are therefore more tolerant of mixed data sources than closed-form regression approaches. In this study, machine learning is employed as a surrogate modeling tool to interpolate complex, nonlinear soil–anchor interactions within the bounds of the available data, rather than as a replacement for physics-based scaling laws or detailed numerical analysis. When used in this surrogate role, ML provides an efficient and transparent means of synthesizing diverse experimental evidence to support preliminary design and uncertainty assessment.

The dataset encoding was clarified: K (shear strength gradient) and Su (local undrained strength) were both included; when only Su was reported for a test, a constant gradient K = 0 was computed for that case, and such records were flagged. For stratified cases, depth-dependent Su profiles were included by adding effective Su at the working depth. The model was trained with both K and Su as inputs, and the data provenance flags allowed separate evaluation of homogeneous vs. stratified cases.

These studies encompass a broad range of testing conditions, anchor geometries, and soil properties, thereby providing a robust foundation for evaluating the predictive accuracy and generalizability of the ML models.

In these analyses, the dataset was randomly divided into the following proportions:

50% training/50% testing;

60% training/40% testing;

70% training/30% testing;

80% training/20% testing;

90% training/10% testing.

Each ratio was generated through a new random split so that variance could be reduced and model stability across multiple partitions could be assessed.

It was consistently observed that model performance improved as the training portion increased, with the 80/20 split being identified as the most stable and accurate across all models. This pattern is consistent with expectations for small datasets, where a larger training set typically enhances generalization while still preserving an adequate sample for testing.

2.6. Quality of Fitness

Five statistical measures were utilized to evaluate the precision, relationship strength, and intricacy of DTR and RFR models: correlation coefficients (R), root mean square errors (RMSEs), the Willmott Index (WI), coefficients of residual mass (CRMs), and Akaike Information Criteria (AICs). For DTR model assessment, R and WI quantified the degree of correlation, whereas RMSE gauged accuracy levels. Furthermore, WI and AIC metrics were applied to examine both model effectiveness and structural complexity. The R and WI measurements demonstrated robust correlation when benchmarked against the TDR ML model. Given that RMSE and CRM values neared zero, the TDR ML model displayed minimal inaccuracy. Nevertheless, these indicators did not capture the TDR ML model’s structural complexity. This gap was filled by implementing the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Therefore, the ideal DTR model is identified by having the smallest AIC value, lowest error measurements (RMSE and CRM), and strongest correlation metrics (R and WI) [

19]:

The terms Oi, Pi, , n and k represent the observed values, predicted values, mean of the observed values, mean of the predicted values, total number of observations, and the number of independent variables, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

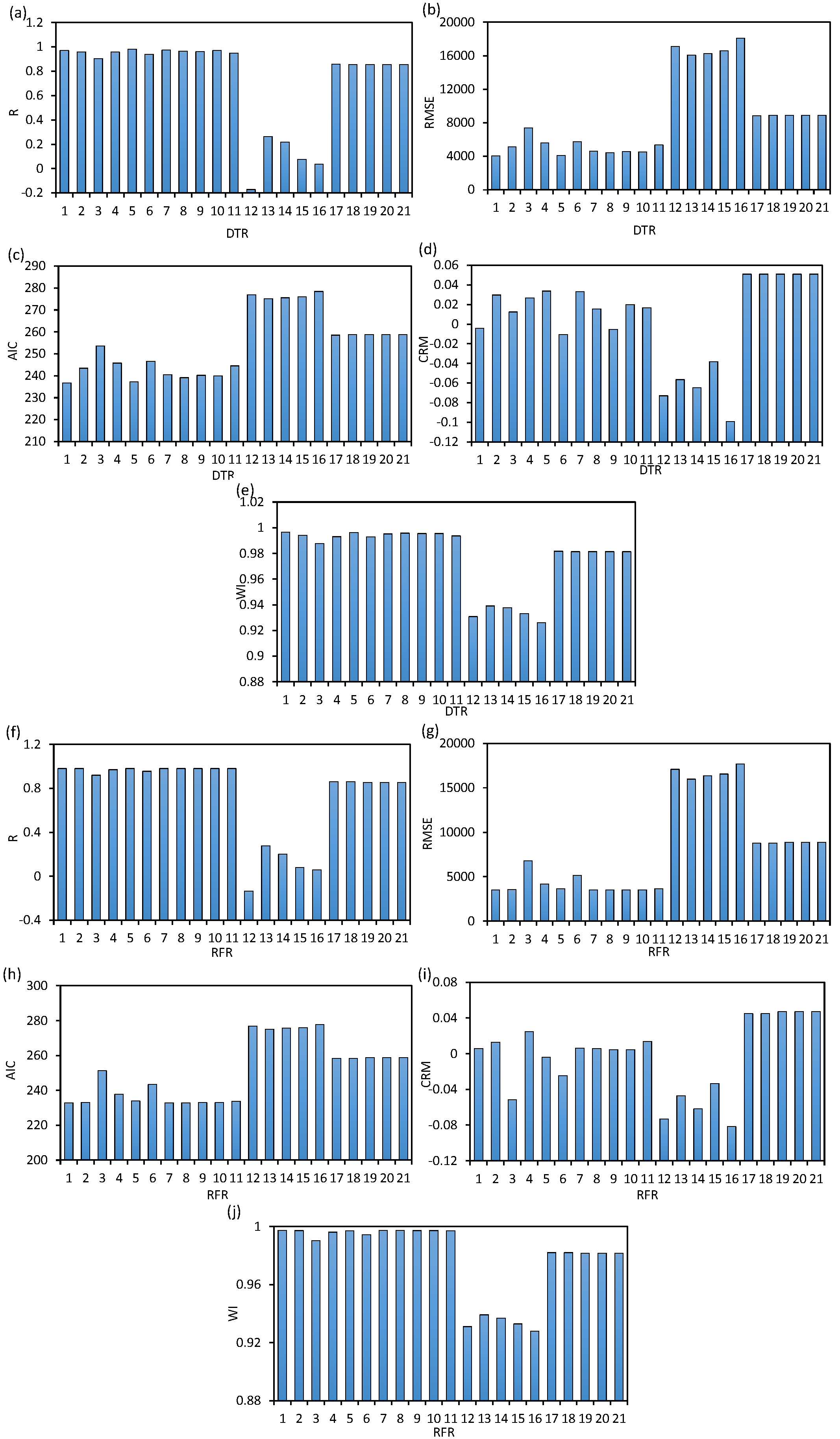

Figure 5 represents the results of the statistical criteria obtained for the holding capacity of DEAs predicted by the DTR and RFR models. The sensitivity analysis focused on evaluating the holding capacity of DEAs using two machine learning models, DTR and RFR, by employing multiple statistical indices to assess prediction performance. The statistical criteria included R, RMSE, AIC, CRM, and WI, presented in subfigures (a) through (j). Sensitivity analysis was conducted by training the baseline models DTR 1 and RFR 1 using all geotechnical and geometric input parameters: effective unit weight (γ′), bearing capacity factor (Nc), shear strength gradient (K), undrained shear strength (Su), fluke–shank angle (α), anchor weight (W), fluke length (Lf), fluke width (bf), shank width (bs), and shank length (Ls). To identify the most critical input affecting the holding capacity prediction, inputs were systematically removed one by one, starting from shank length (Ls) to unit weight (γ′), resulting in 21 model variations per algorithm. Models 1 to 12 represented different combinations intended to identify the best-performing models. In contrast, models 13 to 21 were designed to assess the sensitivity of each input parameter, where removal led to performance degradation, thereby indicating the variable’s importance. Geotechnically, the analyses aimed to account for both the resistance mechanism of soil interacting with the anchor and the geometry of the anchor, which governs how loads were transferred into the seabed. The results revealed that both DTR and RFR models showed high predictive capability when all inputs were present, with RFR generally outperforming DTR across most statistical indices, suggesting its superior generalization and robustness. The deterioration in performance observed in models 13 to 21, especially when key parameters like Su and fluke dimensions were removed, highlighted the importance of these variables in determining anchor holding capacity. This numerical and data-driven approach provided a comprehensive framework for understanding the relative importance of geotechnical and geometric factors in anchor design, with implications for improving design reliability and reducing conservatism in offshore foundation systems. The RFR algorithm demonstrated superior performance over DTR, with RFR 1 achieving the highest accuracy (R = 0.980, RMSE = 3510.6 kN, AIC = 232.9) and robustness across all statistical criteria, while DTR 5 emerged as the best DTR model (R = 0.982, RMSE = 4107.8 kN, AIC = 237.3). Sensitivity analysis revealed that undrained shear strength (S

u) and fluke–shank angle (α) were the most influential parameters for predicting holding capacity, as their removal significantly degraded model performance (e.g., R dropped to 0.859 in RFR 17–21 and 0.853 in DTR 17–21). This aligned with geotechnical principles, where Sᵤ governs clay’s shear resistance and α dictates load transfer efficiency during anchor embedment. The worst-performing models (e.g., RFR 12, DTR 12), which excluded critical inputs, exhibited R < 0.3 and RMSE > 16,000 kN, underscoring the necessity of multivariate analysis to capture soil–anchor interactions. The study’s ML framework provided a computationally efficient alternative to traditional finite element methods, enabling rapid optimization of DEA designs for varying seabed conditions while maintaining ±5% error margins for practical engineering applications. Hence, DTR 5, DTR 17, RFR 1, and RFR 18 were recognized as the best ML models to predict the holding capacity of DEAs in clay seabed. Moreover, anchor weight (W) and fluke length (Lf) were the most effective input parameters to model the holding capacity of the anchor in the cohesive soil seabed using DTR and RFR algorithms.

Feature importance obtained from tree-based machine learning models does not imply causality, but reflects the statistical contribution of input variables to prediction accuracy within the available dataset. In experimental drag embedment anchor databases, collinearity among geometric parameters (e.g., anchor weight, fluke length, and overall anchor size) is unavoidable due to inherent scaling across test programs. As a result, ML sensitivity analyses may identify correlated proxies of anchor scale rather than independent mechanical drivers. Accordingly, the sensitivity results should be interpreted as complementary to classical soil-mechanics-based reasoning, not as a replacement for established analytical or numerical models. When used alongside geotechnical theory, ML sensitivity analysis provides a practical tool for ranking influential parameters and supporting early-stage design and uncertainty assessment.

In the compiled dataset, anchor weight, fluke length, and overall anchor size are strongly linked, since larger anchors naturally have higher mass. As a result, the machine learning model may attribute high importance to weight or length not because these parameters independently govern capacity, but because they act as proxies for the overall anchor scale. This is a common issue in data-driven geotechnical modeling: when geometric variables are inherently related, tree-based models tend to identify the most prominent correlated feature rather than a fundamental physical driver. Thus, the model’s emphasis on anchor weight and fluke length should not be interpreted as a new mechanical insight, but instead as a reflection of collinearity within the existing dataset, where anchor size and mass increase together across the experimental programs included. Despite this limitation, the result remains meaningful in a practical sense: it confirms that capacity scales with anchor dimensions and embedment potential, which is fully consistent with established physical understanding of drag anchor behavior.

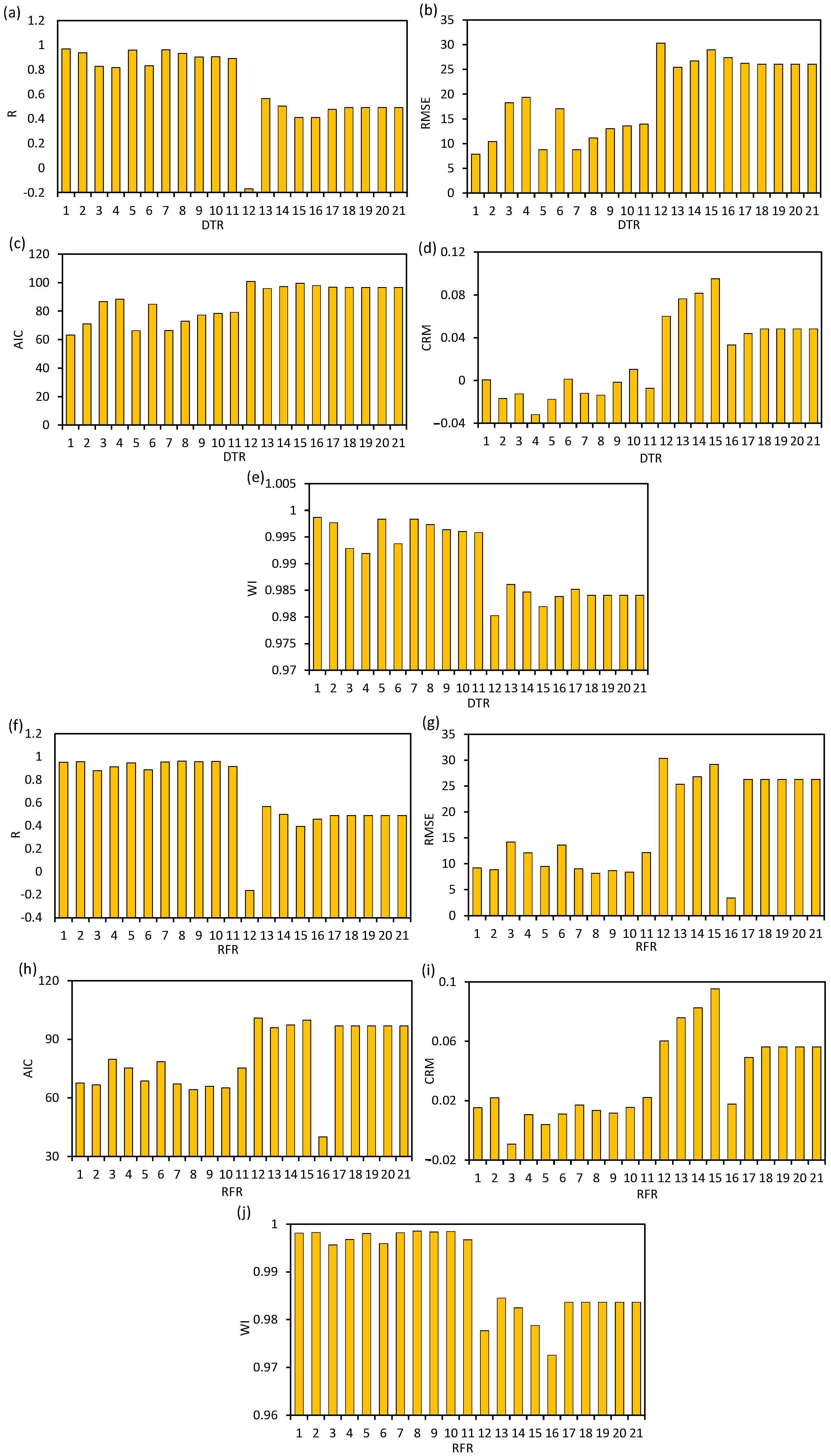

Figure 6 demonstrates the results of the statistical criteria obtained for the efficiency of DEAs predicted by the DTR and RFR models.

The sensitivity analysis conducted on DEAs employed DTR and RFR models to predict anchor efficiency based on ten critical geotechnical and geometric parameters. The geotechnical challenge addressed by this analysis was the complex soil–structure interaction that occurs during anchor embedment, where soil failure mechanisms, anchor penetration depth, and ultimate holding capacity are influenced by both soil characteristics and anchor configuration. The statistical evaluation employed multiple performance metrics to comprehensively assess model accuracy. Through systematic sensitivity analysis involving the sequential removal of input parameters, DTR 1 was the superior model within the DTR framework, achieving the highest correlation coefficient (R = 0.969) and lowest RMSE (7.85) and AIC (63.27) values, while maintaining near-ideal CRM (0.0006) and WI (0.999) metrics. Conversely, within the RFR framework, model RFR 8 demonstrated superior predictive capabilities with an R value of 0.962, RMSE of 8.14, AIC of 64.29, CRM of 0.013, and WI of 0.999. When evaluating the relative importance of individual input parameters through models 13–21, soil unit weight (γ′) emerged as the most influential parameter for both modeling approaches, as evidenced by the substantial deterioration in model performance when this parameter was omitted (DTR 13: R = 0.564, RMSE = 25.43; RFR 13: R = 0.566, RMSE = 25.37). This finding underscored the critical role of effective stress principles in determining anchor efficiency, where the soil’s submerged unit weight directly influences both the vertical stress state and the resulting mobilized shear strength along potential failure surfaces during anchor loading. The dramatic performance decline observed in models without unit weight information demonstrated that accurate characterization of this fundamental soil property was essential for reliable prediction of DEA holding capacity in subsea applications, regardless of the ML algorithms employed. Therefore, DRT 1, DTR 13, RFR 8, and RFR 13 were detected as the superior ML models to estimate the efficiency of DEAs in clay soil. The sensitivity analysis showed that the soil unit weight and bearing capacity factor had the highest level of influence on modeling the efficiency of the anchor in a cohesive seabed.

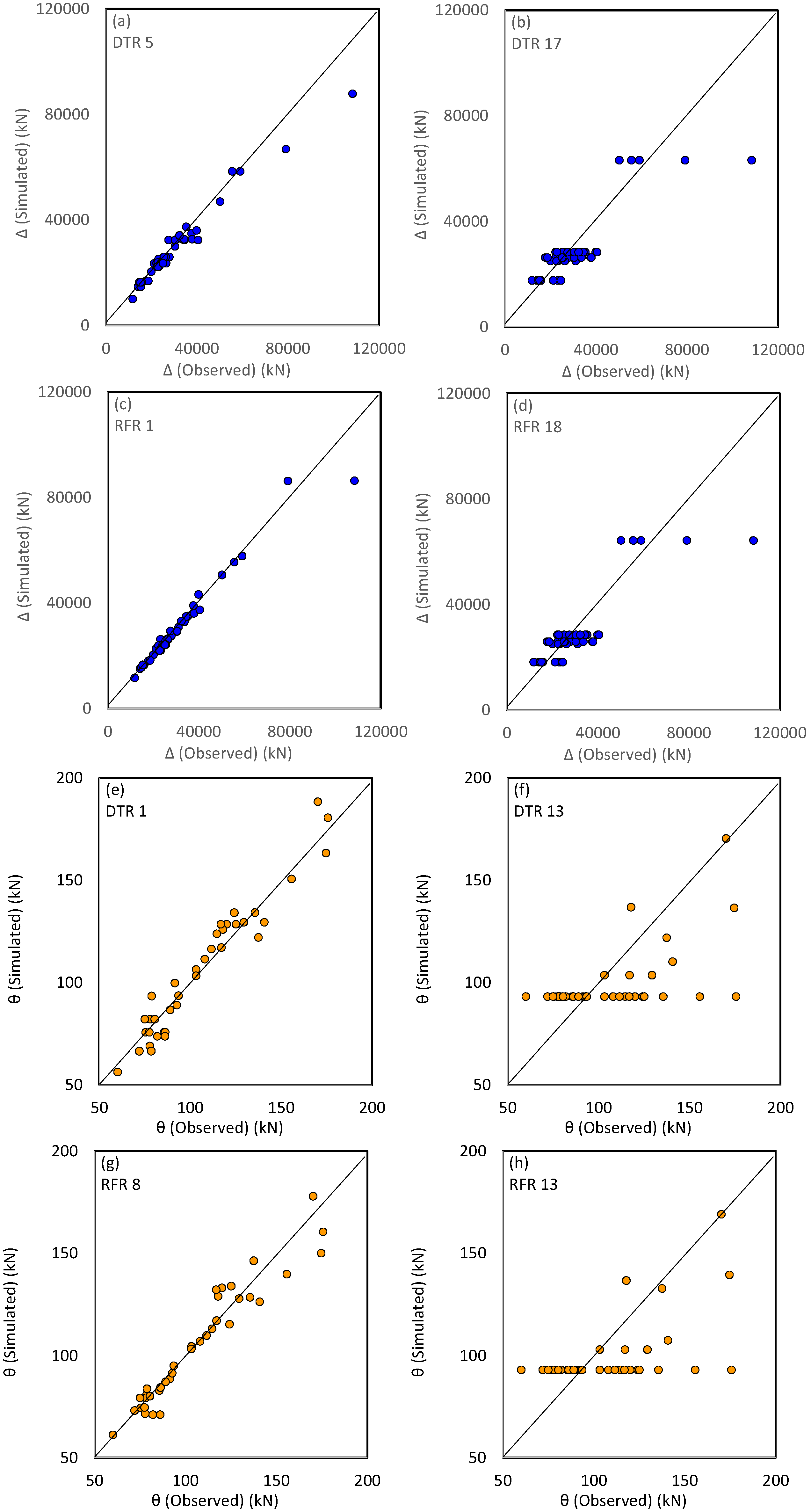

The scatter plots of the superior ML model for estimating the holding capacity and efficiency of DEAs are illustrated in

Figure 7. The scatter plots provided visual evidence of the models’ performance, showcasing the alignment between observed and predicted values for holding capacity and efficiency. For instance, the DTR 5 and DTR 13 models demonstrated strong predictive accuracy for holding capacity, as indicated by the close clustering of data points around the ideal 1:1 line. Similarly, the RFR 1 and RFR 13 models exhibited high efficiency in predicting anchor performance, leveraging ensemble learning to minimize overfitting and enhance generalization.

These results underscore the capability of ML models to capture the nonlinear relationships between input parameters and anchor behavior. Geotechnical parameters such as undrained shear strength (Su) and effective unit weight (γ′) were identified as critical determinants of holding capacity. Su governed the shear resistance of the seabed soil, while γ′ influenced the stress distribution and embedment depth. The bearing capacity factor (Nc) and shear strength gradient (K) further refined the models by accounting for soil stratification and variations in strength with depth. These parameters were particularly significant in cohesive soils, where shear strength and stress history play pivotal roles in anchor stability.

Geometric parameters, including fluke dimensions (Lf, bf) and shank dimensions (bs, Ls), were equally vital. The fluke–shank angle (α) and anchor weight (W) affected the anchor’s penetration and resistance to overturning moments. The scatter plots for RFR 8 and RFR 18 highlighted how these geometric features influenced embedment depth and load distribution, ensuring optimal performance under varying seabed conditions. The inclusion of these parameters in the ML models ensured a holistic representation of anchor–soil interactions.

Traditional methods for predicting DEA performance often relied on simplified assumptions, which limited their accuracy in complex marine environments. The ML-based approach addressed these limitations by leveraging data-driven techniques to model intricate, nonlinear relationships.

The input parameter table illustrated the systematic exploration of parameter combinations, enabling the identification of optimal models for specific conditions. For example, Model 1 incorporated all key parameters, while subsequent models explored subsets to balance complexity and computational efficiency.

Thus, the study demonstrated the superiority of DTR and RFR models in predicting DEA performance, validated by the scatter plots and parameter table. The models’ ability to integrate geotechnical and geometric parameters provided a robust framework for anchor design and deployment. This research contributed to the growing body of evidence supporting ML applications in geotechnical engineering, offering a reliable and scalable solution for marine anchor systems. The systematic methodology and results underscored the importance of comprehensive parameter inclusion and data-driven modeling in advancing geotechnical practice.

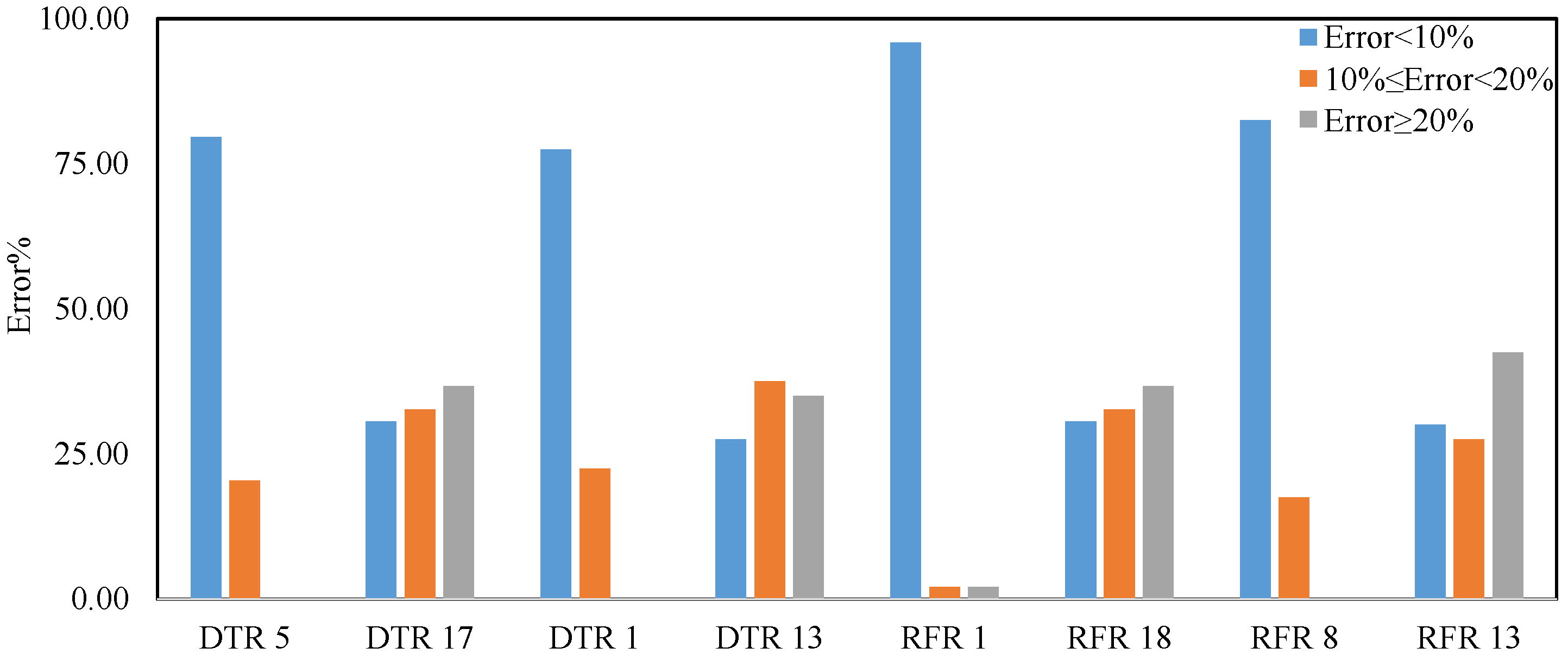

Figure 8 demonstrates the error distribution plots of the best ML model in predicting the holding capacity and efficiency of DEAs in the clay seabed. The error distribution pie charts for the best-performing models represented the extent to which each model could reliably predict holding capacity and efficiency. For holding capacity, the RFR 1 model emerged as the most accurate, with 96% of its predictions falling within a 10% error margin, showcasing its robustness and ability to generalize from the training data. Similarly, DTR 5 demonstrated strong performance with 80% of its predictions under a 10% error and the remaining 20% within 10–20%, indicating minimal overfitting and effective capture of nonlinear input relationships. In contrast, DTR 17 and RFR 18 each showed less reliable performance, with approximately one-third of predictions exceeding 20% error, likely due to model oversimplification or insufficient feature sensitivity.

In terms of efficiency prediction, the RFR 8 model stood out, achieving 82% of predictions within the <10% error range and only 18% exceeding 10%, suggesting a high degree of precision. DTR 1 also performed reliably, with 77% accuracy within the 10% margin, though 23% of its predictions fell in the higher error band. On the other hand, DTR 13 and RFR 13 exhibited more distributed errors, with both models producing over one-third of predictions exceeding a 20% error. This behavior could be attributed to their inability to capture the complex interaction effects between input parameters under varying load and embedment scenarios.

These outcomes reaffirmed the significance of model selection and the sensitivity of DEA performance to soil–structure interaction factors. The models that integrated a comprehensive understanding of geotechnical behavior, particularly through ensemble techniques like RFR with appropriate parameter tuning, consistently outperformed simpler models. The results also validated earlier findings in offshore engineering literature, which emphasized that accurate predictions of anchor performance depend not only on soil strength but also on geometrical compatibility and load path considerations.

Table 2 shows the results of the discrepancy ratio (DR) for the superior ML models. The DR analysis of superior ML models provided critical insights into their predictive accuracy for DEA performance in marine geotechnical applications. The DR values, calculated as the ratio of predicted-to-observed holding capacities, served as a robust metric to evaluate model performance across different operational conditions. The results demonstrated varying degrees of predictive capability among the DTR and RFR models, with DR values revealing systematic patterns in model behavior.

The DTR 5 model exhibited the most consistent performance, with DR(max) = 1.177, DR(min) = 0.801, and DR(ave) = 0.987 indicating minimal systematic overprediction or underprediction. This narrow DR range (0.801–1.177) suggested that the model effectively captured the complex soil–anchor interactions, particularly for anchors in homogeneous clay seabed, where undrained shear strength (Su) dominated the holding capacity. The near-unity average DR (0.987) confirmed the model’s reliability for engineering applications requiring precise capacity estimates.

In contrast, the DTR 17 and RFR 18 models showed wider DR ranges (0.582–1.492 and 0.592–1.539, respectively), reflecting greater prediction variability. These extreme values typically occurred in stratified soil profiles where the shear strength gradient (K) and bearing capacity factor (Nc) varied significantly with depth. The higher DR(max) values suggested occasional overprediction in very soft surface layers, while the low DR(min) values indicated underprediction in stiff underlying strata. Nevertheless, their average DR values (1.009 and 1.016) remained close to ideal, demonstrating overall balanced performance.

The RFR 1 and RFR 8 models displayed particularly stable behavior with DR(max) < 1.2 and DR(min) > 0.8, making them suitable for sensitive applications where conservative estimates were required. Their performance highlighted the advantage of ensemble methods in handling the nonlinear effects of geometric parameters like fluke–shank angle (α) and anchor weight (W). The models’ robustness against overfitting was evident in their consistent DR(ave) values (1.007 and 0.989), which remained stable across different soil–anchor configurations.

Extreme DR values in DTR 13 and RFR 13 (DR(max) = 1.550, DR(min) = 0.530) revealed limitations in predicting capacity for anchors with unconventional geometries (e.g., very high bf) or in highly heterogeneous soils. These outliers typically corresponded to cases where local soil variations or anchor installation effects dominated the capacity mechanism. However, their average DR values (0.977) still fell within acceptable engineering tolerances, suggesting the models remained useful for preliminary design despite occasional large errors.

Model performance correlated strongly with soil homogeneity and anchor geometry standardization. Models performed best in uniform clay deposits where Su could be characterized by a single value, while predictions became less reliable in layered systems with alternating soft and stiff layers. The DR patterns also reflected the influence of secondary parameters—models systematically underpredicted capacity for lightweight anchors (W < 500 kg) in very soft soils and overpredicted for heavy anchors in dense sands.

The DTR 5 and RFR 1 models were recommended for final design stages where precision was critical, while the more conservative RFR 8 suited risk-averse applications. The higher-variability models (DTR 17, RFR 18) remained valuable for preliminary assessments across diverse conditions. This stratified approach to model application represented a significant advancement in geotechnical practice, moving beyond one-size-fits-all solutions to context-specific predictions.

The DR analysis ultimately validated ML techniques as superior to conventional methods for DEA capacity prediction, while also identifying their limitations and optimal use cases. The comprehensive evaluation provided engineers with both quantitative performance metrics (DR values) and qualitative guidance on model selection, establishing a framework for reliable anchor design in complex marine environments. These findings contributed to the growing recognition of data-driven approaches in geotechnical engineering, particularly for problems involving numerous interacting parameters and non-linear system behavior.

The performance values reported in the manuscript correspond to the testing dataset, not the training mode. The RFR model naturally attains a higher on the training set, while the lower testing score reflects its true generalization ability. This difference is expected for ensemble tree models and indicates some degree of overfitting, which is common when working with relatively small geotechnical datasets. To avoid misinterpretation, the revised manuscript explicitly states that the results reported testing performance, and training metrics are not used to evaluate the model’s predictive reliability.

In

Table 3, a comparison is presented between the superior ML models for estimating the capacity and efficiency of DEAs using FEM and the empirical method [

26]. For capacity prediction, RFR 1 achieved the highest correlation coefficient (R = 0.980), the lowest RMSE, the smallest AIC, and a near-zero CRM, indicating excellent accuracy, model parsimony, and negligible bias compared with FEM and the empirical approach. Similarly, for efficiency prediction, RFR 8 outperformed the other models, exhibiting a high R value (0.962), minimal RMSE, and the highest Willmott Index (WI = 0.999). Overall, the ML models demonstrated superior predictive reliability and reduced uncertainty relative to FEM and empirical methods.

The proposed machine learning framework is intended to complement, rather than replace, advanced finite element and large-deformation finite element (FEM/LDFE) analyses. While FEM/LDFE models remain essential for detailed verification and site-specific assessment, the ML models developed herein are designed for early-stage concept design, rapid optimization loops, and uncertainty or sensitivity analyses, where repeated high-fidelity simulations are impractical. In this context, ML serves as a computationally efficient surrogate for interpolating within existing experimental knowledge. Future work will focus on benchmarking the proposed models against recent LDFE datasets, where available, to further assess their accuracy and applicability across a broader range of seabed conditions.

The application of DTR and RFR algorithms in modeling the holding capacity and efficiency of DEAs in clay seabed represents a significant advancement in geotechnical engineering. By leveraging ML techniques, these models successfully captured the complex, nonlinear interactions between soil properties, e.g., undrained shear strength, effective unit weight, anchor geometry, fluke dimensions, and shank angle. The performed analyses demonstrated that ML models, particularly DTR 5 and RFR 1, provided precise predictions with minimal bias, making them invaluable for offshore engineering applications where safety and efficiency are paramount. This innovation is especially crucial for modern marine infrastructure projects, where anchor performance directly impacts cost, stability and environmental sustainability. By integrating data-driven approaches with geotechnical principles, this study not only enhances the predictive capability for DEA design but also paves the way for broader ML adoption in geotechnical challenges, marking a transformative step toward smarter, more adaptive engineering solutions.

The modeling of DEAs in clay seabed has witnessed a paradigm shift through the integration of ML algorithms, offering unprecedented robustness compared to traditional analytical approaches. ML methodologies transcend the limitations of conventional empirical methods by simultaneously processing multiple geotechnical parameters, including undrained shear strength profiles, soil unit weight, and bearing capacity factors, alongside complex anchor geometries, capturing nonlinear soil–structure interactions that previously defied comprehensive mathematical representation. This enhanced modeling capability has proven critical for offshore energy infrastructure, where even marginal improvements in predictive accuracy translate to substantial economic and safety benefits across deep-water installations. The robustness of ML-driven anchor models lies in their ability to generalize across diverse clay conditions while maintaining computational efficiency, enabling rapid evaluation of multiple design scenarios without resource-intensive physical modeling or finite element analysis. Furthermore, these data-driven approaches have demonstrated remarkable adaptability in incorporating field performance data, continuously refining predictive capabilities through operational feedback loops, a distinct advantage in addressing the inherent uncertainties of subsea geotechnical environments. As offshore developments extend into increasingly challenging and variable seabed conditions, the importance of these sophisticated modeling approaches becomes paramount, fundamentally transforming how engineers conceptualize, design, and deploy critical mooring systems in clay-dominated marine environments.

4. Conclusions

This study explored the application of tree-based machine learning (ML) algorithms, specifically decision tree regression (DTR) and random forest regression (RFR), to predict the performance of drag embedment anchors (DEAs) in clay seabed environments. DEAs were critical for offshore mooring systems, offering high holding capacity-to-weight ratios and adaptability to diverse seabed conditions. Traditional methods for predicting DEA performance, such as finite element analysis and centrifuge testing, faced limitations in scalability and computational efficiency. To address these challenges, this research leveraged ML techniques to model the complex, nonlinear interactions between geotechnical parameters (e.g., undrained shear strength, effective unit weight) and anchor geometry (e.g., fluke dimensions, shank angle).

The methodology involved data collection, preprocessing, and feature selection, followed by training and evaluating 21 model variations for each algorithm. Performance was assessed using statistical metrics like correlation coefficient (R), root mean square error (RMSE), and discrepancy ratio (DR). Results demonstrated that RFR outperformed DTR, with RFR 1 achieving the highest accuracy (R = 0.980, RMSE = 3510.6 kN) for holding capacity predictions. The study highlighted the superiority of RFR models in capturing soil–anchor interactions, offering a computationally efficient alternative to traditional methods. The research underscored the transformative potential of ML in geotechnical engineering, paving the way for data-driven, adaptive design frameworks.

From a geotechnical perspective, the sensitivity analysis results indicated that anchor weight and fluke length were critical determinants of the holding capacity of DEAs. This finding aligned with established anchor theory: heavier anchors exerted greater downward force, enhancing penetration and increasing resistance against pullout. Similarly, a longer fluke provided a larger bearing area, enabling better interaction with the soil mass and mobilizing higher resistance during embedment and loading. These parameters directly affected the development of passive resistance in cohesive soils like clay, where bearing area and overburden pressure were vital to anchor performance.

On the other hand, efficiency was governed primarily by the soil unit weight (γ′) and the bearing capacity factor (Nc). A higher effective unit weight implied denser or more consolidated soils, which increased the vertical stress acting on the fluke and contributed to greater shear resistance during anchor mobilization. Meanwhile, the bearing capacity factor (Nc) reflected the soil’s inherent ability to resist shear failure under embedded conditions, making it a fundamental input in classical bearing capacity theories. These parameters indicated that efficiency was less dependent on the anchor’s geometry or mass and more on the surrounding soil’s ability to support the load mobilized by a given anchor size. Hence, for optimizing anchor design in clay seabed, it was critical to not only select appropriate anchor dimensions but also thoroughly characterize the in situ soil conditions, particularly γ′ and Nc, to ensure high performance relative to weight.

This study demonstrated the successful application of tree-based ML models in predicting DEA performance in a cohesive seabed, offering a computationally efficient alternative to traditional simulation and testing methods. The research established ML as a valuable tool for preliminary anchor design and site evaluation. Future work could enhance the models by incorporating more field data, employing probabilistic approaches or ensemble methods to improve reliability across diverse seabed conditions, and integrating real-time sensor data for adaptive monitoring systems. The study validates ML’s potential for modeling complex soil–anchor interactions and provides a foundation for further innovations in geotechnical engineering.