1. Introduction

The geometric parameters of vertical-axis tidal turbine (VATT) blades decisively govern their low-velocity performance. Studies demonstrate that airfoil camber significantly enhances starting torque, with 20% camber blades increasing the power coefficient by up to 24.42% [

1]. Conversely, thickness parameters regulate stall characteristics—thinner profiles (14% thickness) outperform thicker counterparts (18% thickness) in pre-stall lift-to-drag ratio but suffer 41% performance degradation post stall [

2]. Current optimization strategies include coupled curvature-pitch angle design [

3,

4], counter-rotating rotor configurations [

5,

6,

7], and composite material applications [

8]. Among these, response surface methodology and neural networks (e.g., TurbineNet) achieve ≤2% errors in hydrodynamic prediction [

9]. Nevertheless, the influence of blade geometry on startup vortex evolution mechanisms remains unquantified [

10], hindering adaptability in low-velocity conditions.

Wake recovery velocity directly determines array energy capture efficiency. Ducted turbine wakes conform to a double-Gaussian model with accelerated recovery [

11], while staggered array layouts enhance wake recovery by 10%~21% compared to square arrangements [

12,

13,

14]. Environmental perturbations exhibit complex dynamics: waves amplify torque fluctuations threefold [

15]; seabed topography causes ±40% power output variations [

16,

17]; sediment-laden flows alter lift–drag coefficients [

18]; and support structures trigger local scouring [

19]. To address these, array controllers stabilize loads by regulating pitch angles and rotational speeds [

20,

21], and quantum discrete particle swarm optimization improves power generation by 19%. However, existing wake models lack experimental validation under wave–current coupling [

22,

23,

24], limiting their engineering applicability.

High-fidelity numerical simulation is central to performance prediction. Large eddy simulation resolves unsteady vortex shedding [

25], while the SST k-ω model achieves <9.2% error in stall prediction [

26]. Fluid–structure interaction models (e.g., DLFSI [

27]) optimize blade stress distributions. Experimentally, particle image velocimetry (PIV) quantifies near-wake structures [

28], and vessel-mounted ADCP characterizes megawatt-scale turbine wakes [

29]. Yet limitations persist: blade element momentum theory fails to resolve dual-rotor interference; RANS models exhibit >15% deviations in separated flow prediction [

30]; and scaled experiments struggle to replicate real-sea turbulence intensity. Crucially, high-resolution validation of startup vortex evolution remains scarce [

31].

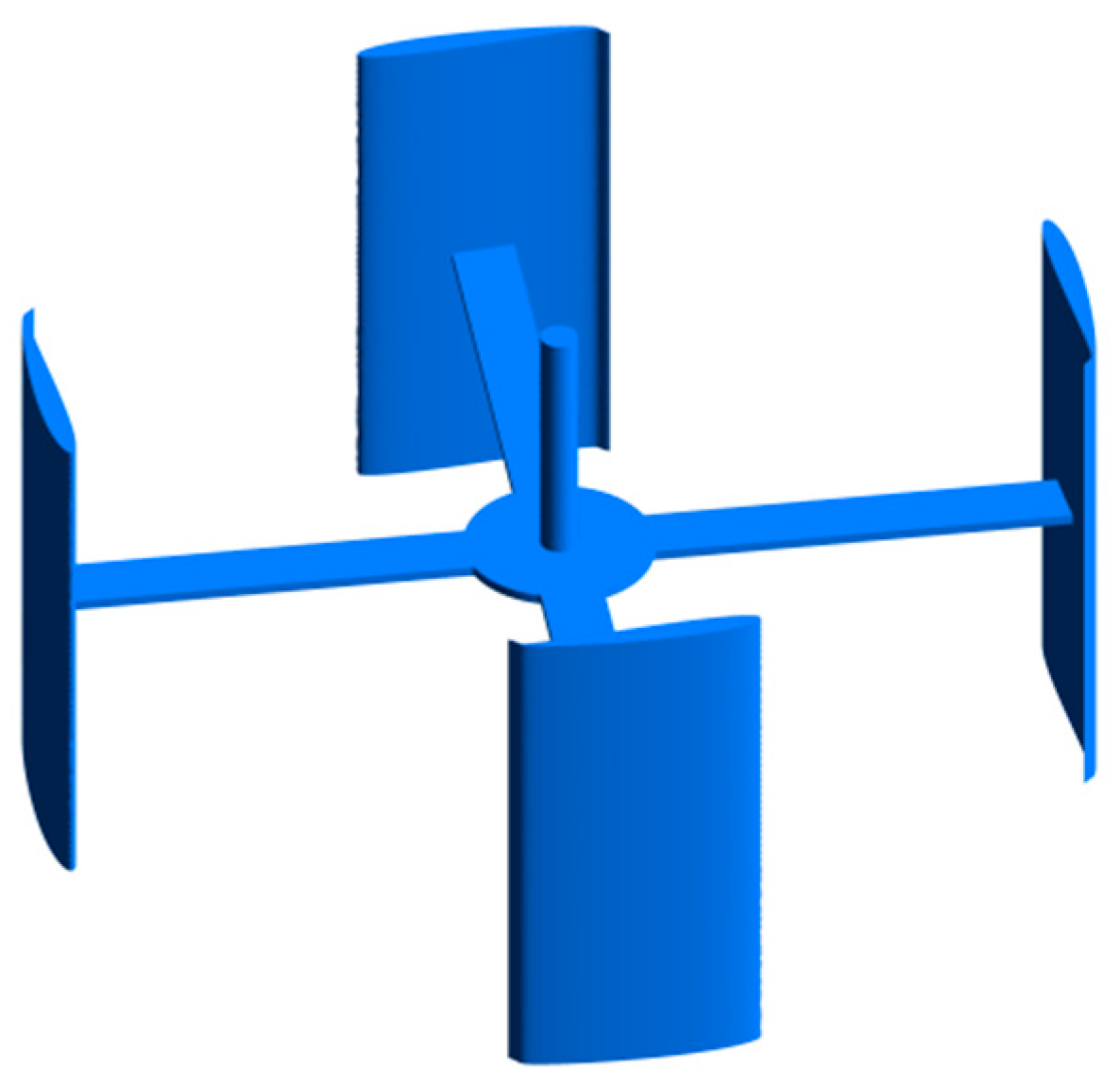

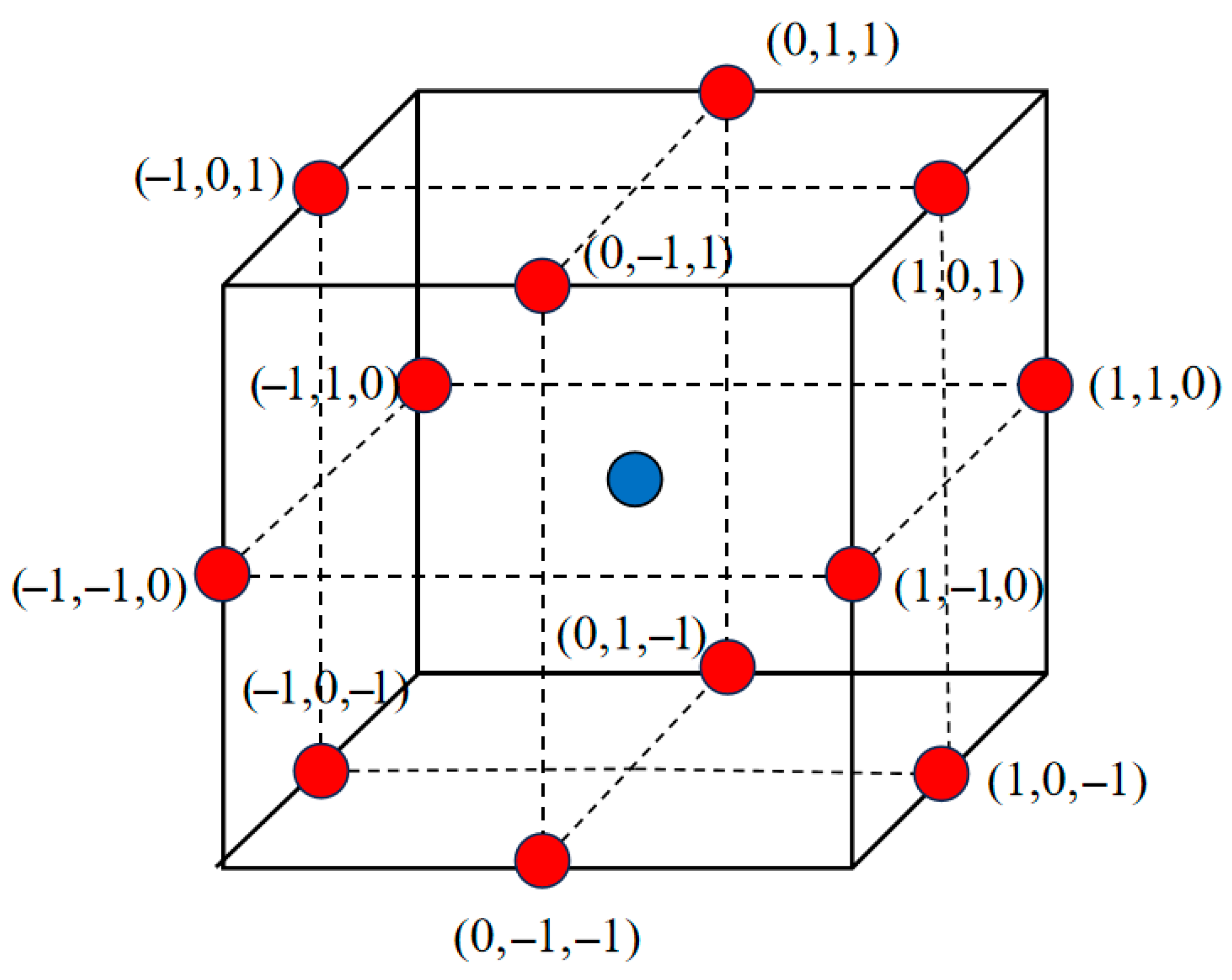

This study addresses this critical gap by establishing an integrated research framework combining parametric airfoil design, response surface optimization, and high-fidelity CFD verification. Unlike previous comparative studies of existing airfoils, our approach systematically explores the design space through three key geometric parameters: maximum thickness ratio (Factor A), location of maximum thickness (Factor B), and maximum camber (Factor C). This methodology enables the identification of optimal airfoil configurations specifically tailored for low-velocity tidal conditions (Reynolds number = 1.6 × 106).

Our contribution advances the field in three significant aspects: (1) development of a parameterization scheme that efficiently captures the geometric characteristics most influential to low-Reynolds number performance; (2) implementation of response surface methodology to navigate the complex multi-parameter design space while minimizing computational cost; and (3) rigorous validation through three-dimensional unsteady simulations that capture the dynamic flow phenomena characteristic of vertical-axis turbines. The optimization framework identifies an airfoil configuration that achieves a 27.5% improvement in power coefficient compared to the baseline NACA 2414 design.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

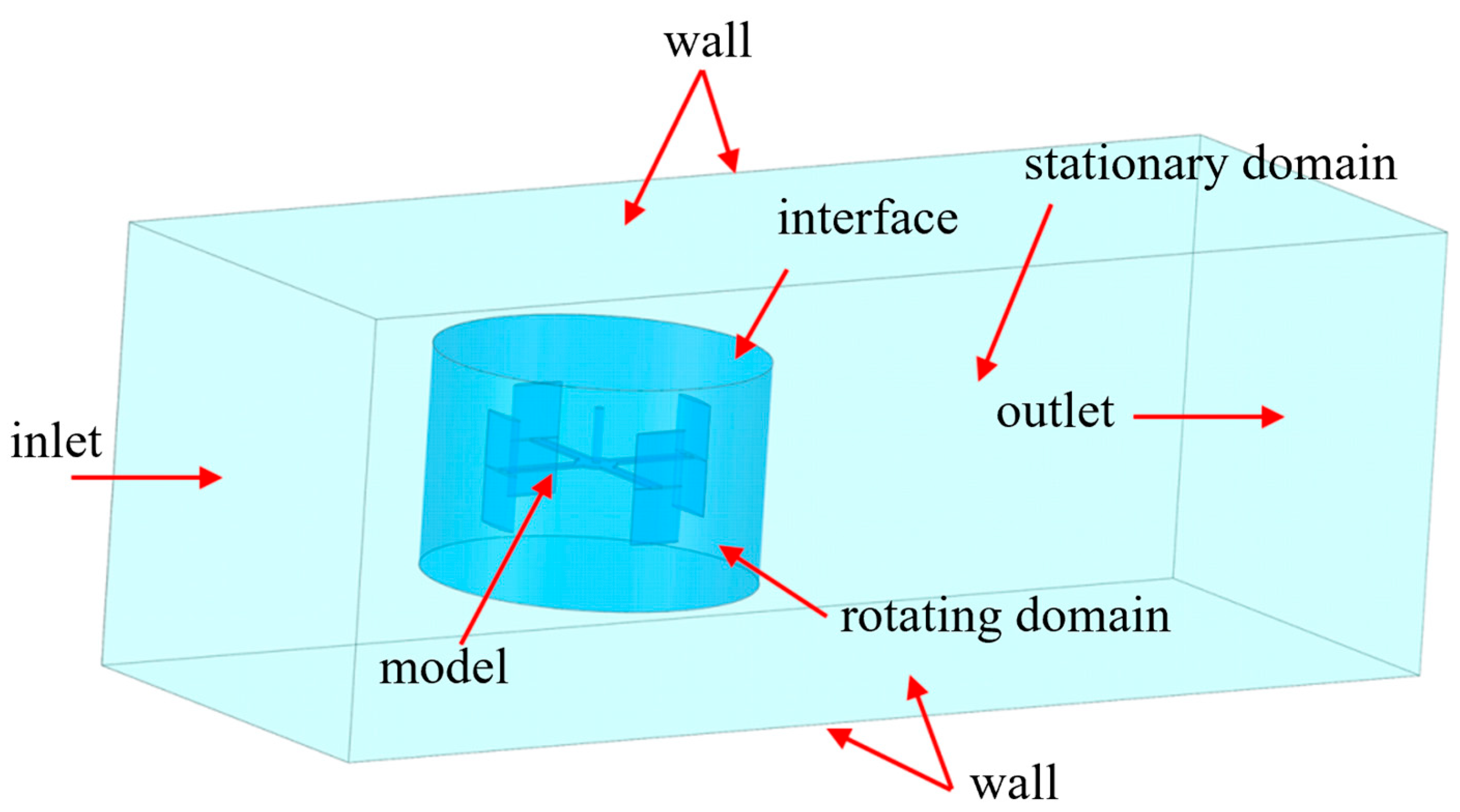

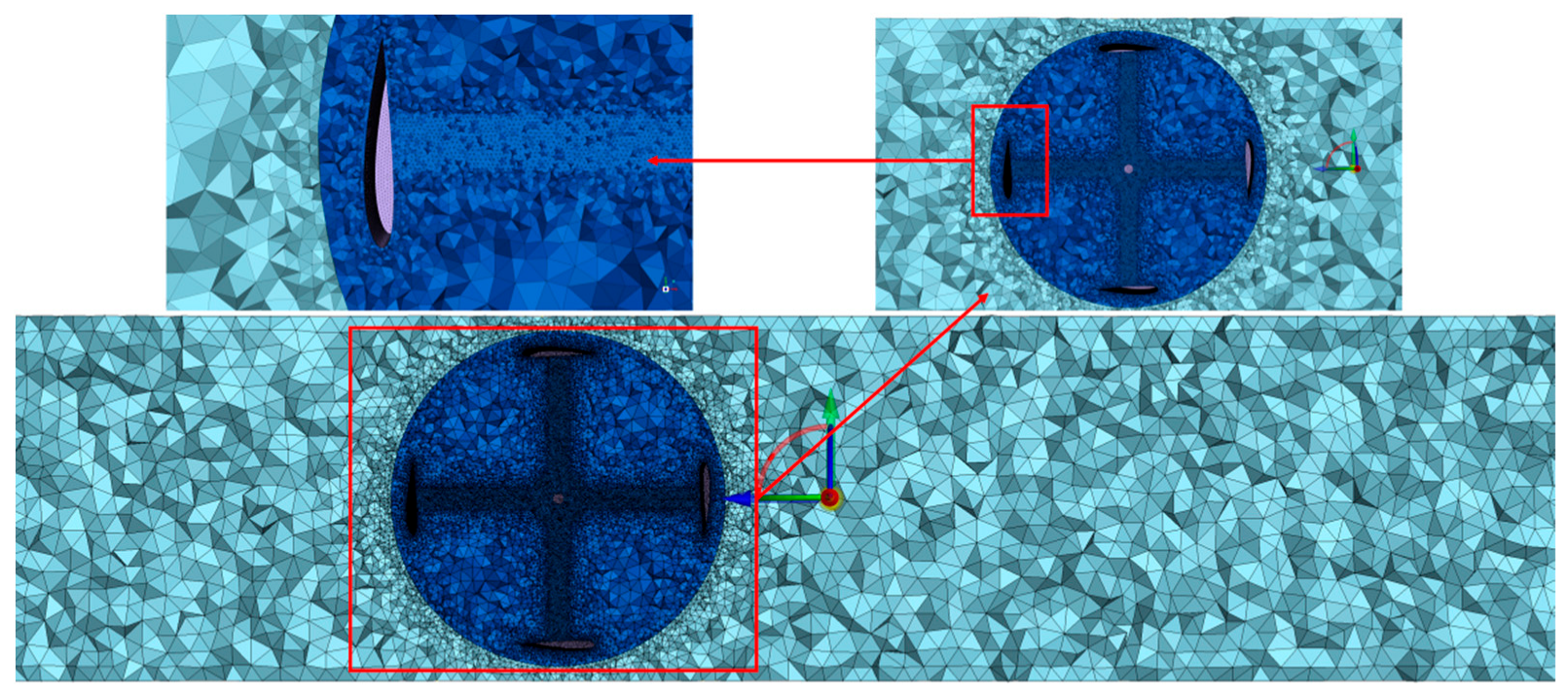

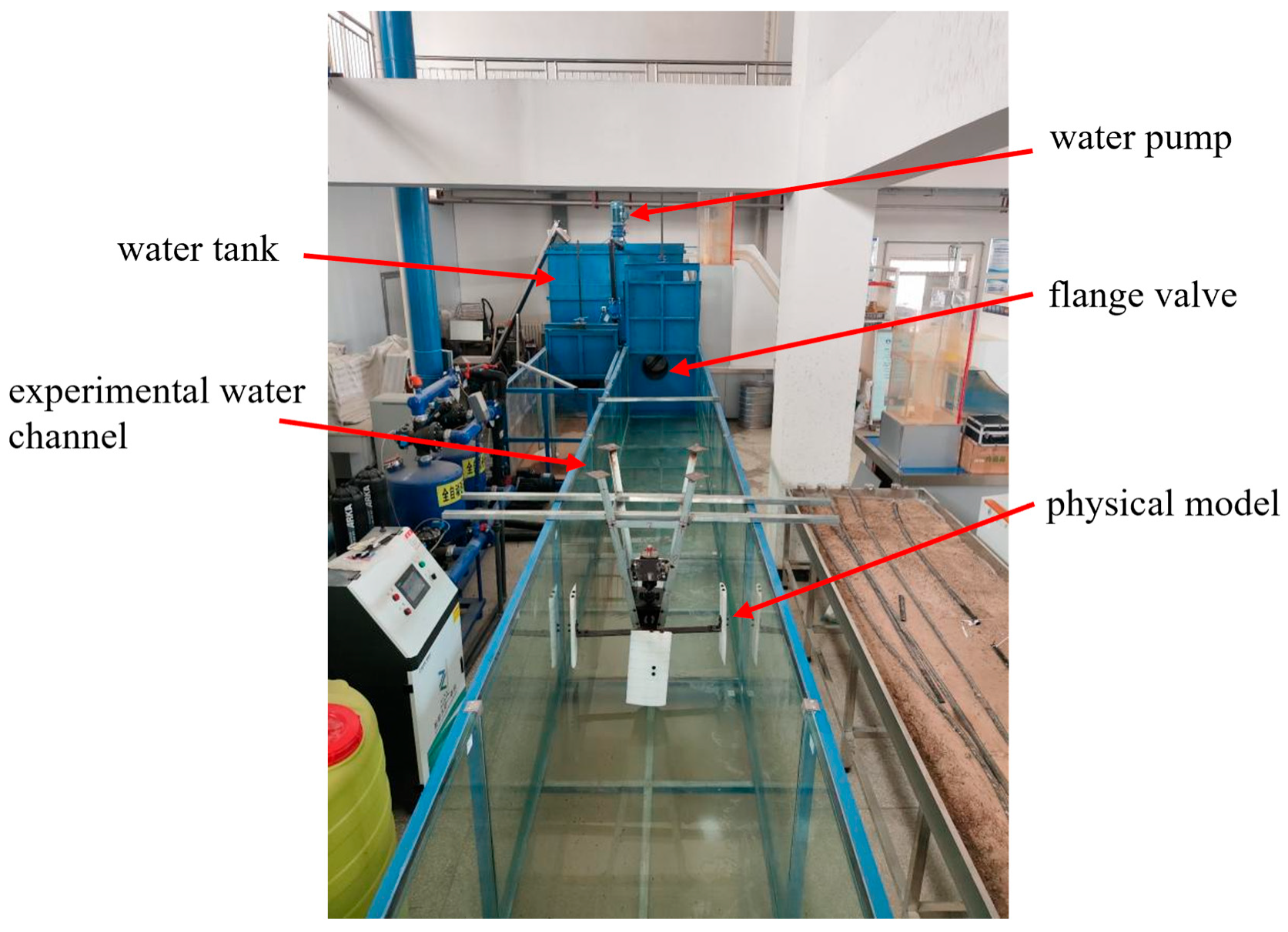

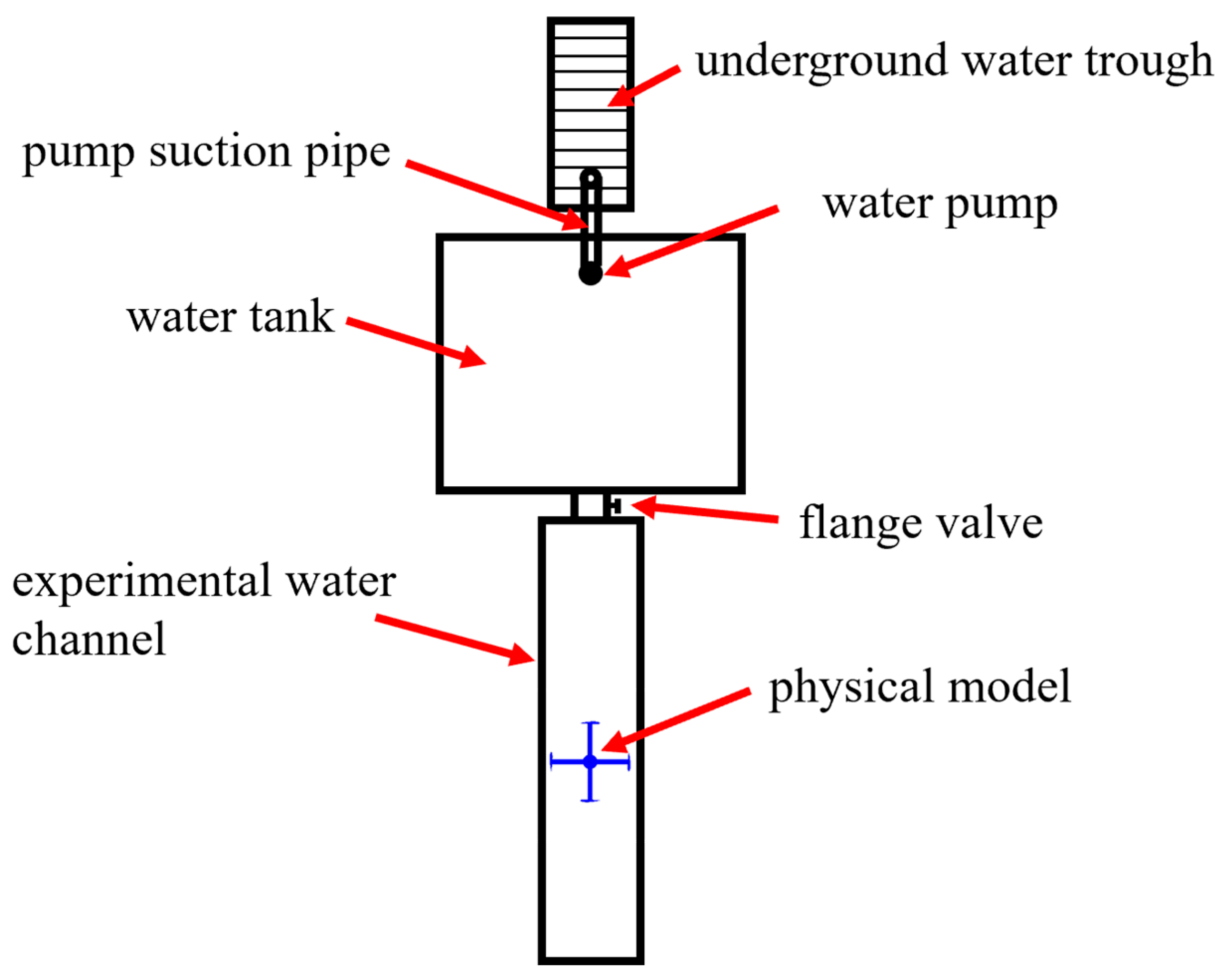

Section 2 details the parametric design methods and computational framework, including model establishment, meshing, numerical model setup, and experimental validation methods;

Section 3 presents the optimization process and validation results, analyzes the influence mechanisms of airfoil parameters on performance, and discusses the research limitations and future work directions;

Section 4 summarizes the main research conclusions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Experimental Results

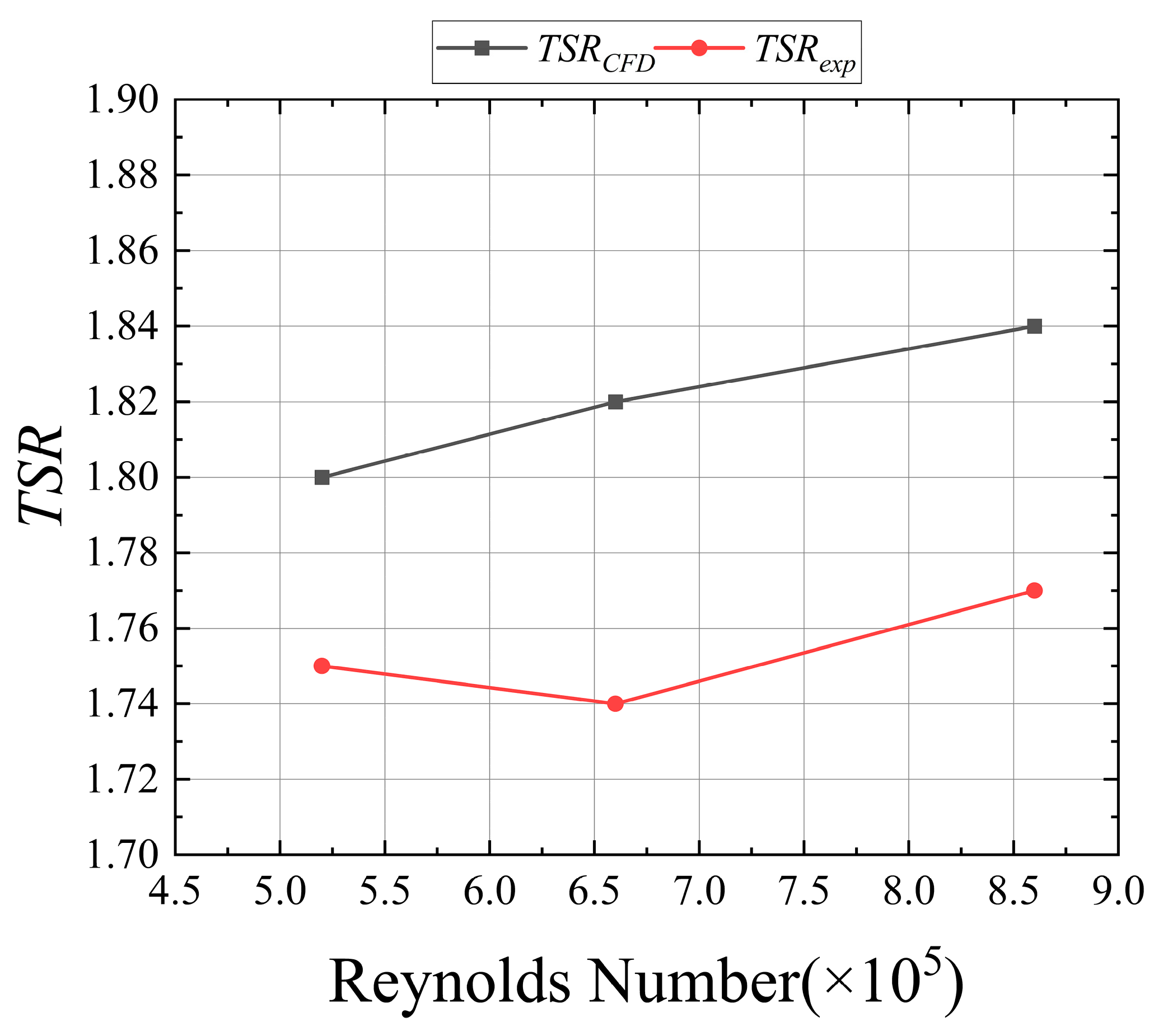

Three-dimensional numerical simulations and validation experiments were conducted on a turbine employing the NACA 2414 airfoil under various Reynolds numbers. The average angular velocity over five cycles during the stable operation phase was obtained, from which

TSRCFD and

TSRexp were calculated. Curves depicting their variation with Reynolds number were plotted, as detailed in

Figure 9.

Three specific Reynolds number points and their corresponding

TSRCFD and

TSRexp values were selected. The relative error ε was calculated using the error formula, with detailed results presented in

Table 7.

Based on the comparison between 3D CFD simulations and experimental data, within the Reynolds number range of Reynolds number = 5.2 × 105 to 8.6 × 105, the simulated and measured Tip Speed Ratio (TSR) values show good agreement. The maximum relative error is only 4.5%, indicating that the established numerical model can reliably capture the hydrodynamic characteristics of the turbine under different flow velocities. The observed systematic deviation primarily stems from simplifications in the turbulence model, mesh discretization errors, and uncertainties in experimental measurements. However, these minor discrepancies are within the acceptable range for engineering applications.

Through high-precision validation of TSR, this study confirms the reliability of the CFD model for performance comparison. Consequently, the conclusion that the performance of the optimized airfoil is significantly improved, derived from the same model, is credible. This provides a solid verification foundation for the entire parametric optimization process.

3.2. Experimental Results Based on RSM

The power coefficient (

CP) for each design combination in the

BBD matrix was obtained through three-dimensional numerical simulations, as shown in

Table 8.

A second-order response surface model was employed to analyze the nonlinear effects of multiple factors on the response variables. The generalized second-order polynomial model takes the form:

where

y denotes the response variable;

xi,

xj represent the coded independent variables;

β0 is the constant term;

βi signifies the linear effect coefficients;

βii indicates the quadratic effect coefficients;

βij corresponds to the interaction effect coefficients; and

ι designates the random error.

The experimental datasets were substituted into Equation to fit regression equations for the response variables, establishing relationships between the independent variables

x and responses

y. The resulting fitted regression equation for

CP is given by Equation (15).

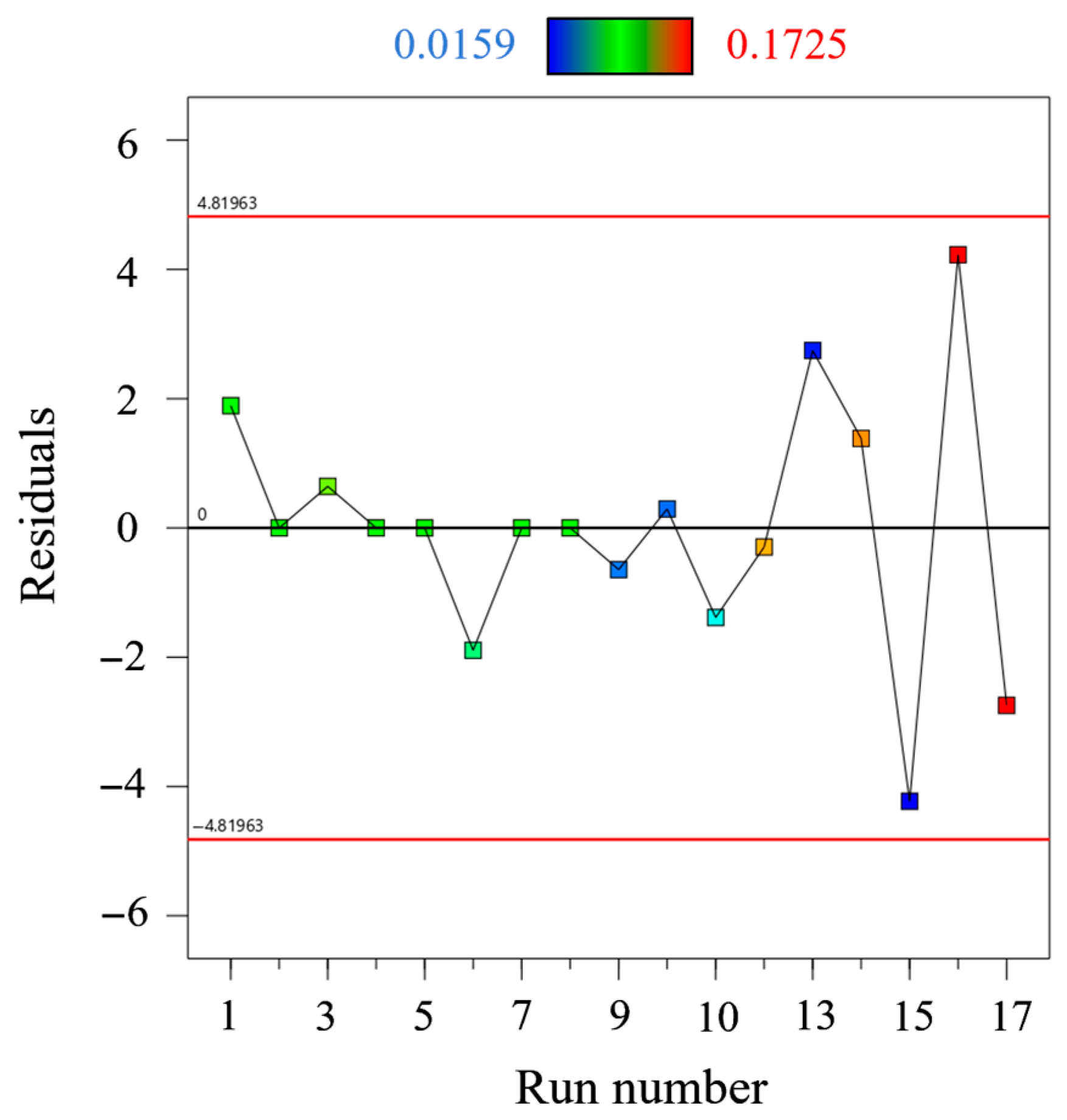

Residual plots were used to validate the regression equations. As shown in

Figure 10, the samples are significantly and randomly distributed on both sides of the x-axis, indicating the acceptability of the response function. However, relying solely on residual inspection is insufficient to fully assess the goodness of fit of the response surface model, as it may not reveal all potential issues. Therefore, the R-criterion was supplemented for a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance and applicability.

The regression equation was examined using R-squared analysis, and the results are presented in

Table 9.

As shown in

Table 9, the

p-value for

CP is 0.0013, which is far below the significance threshold (α = 0.05). Simultaneously, the coefficient of determination (R

2) is 0.9441, and the adjusted R

2 (R

2adj) is 0.8723. Integrating these findings with the residual plot analysis indicates that the established model possesses good reliability and robustness.

3.3. Variable Analysis

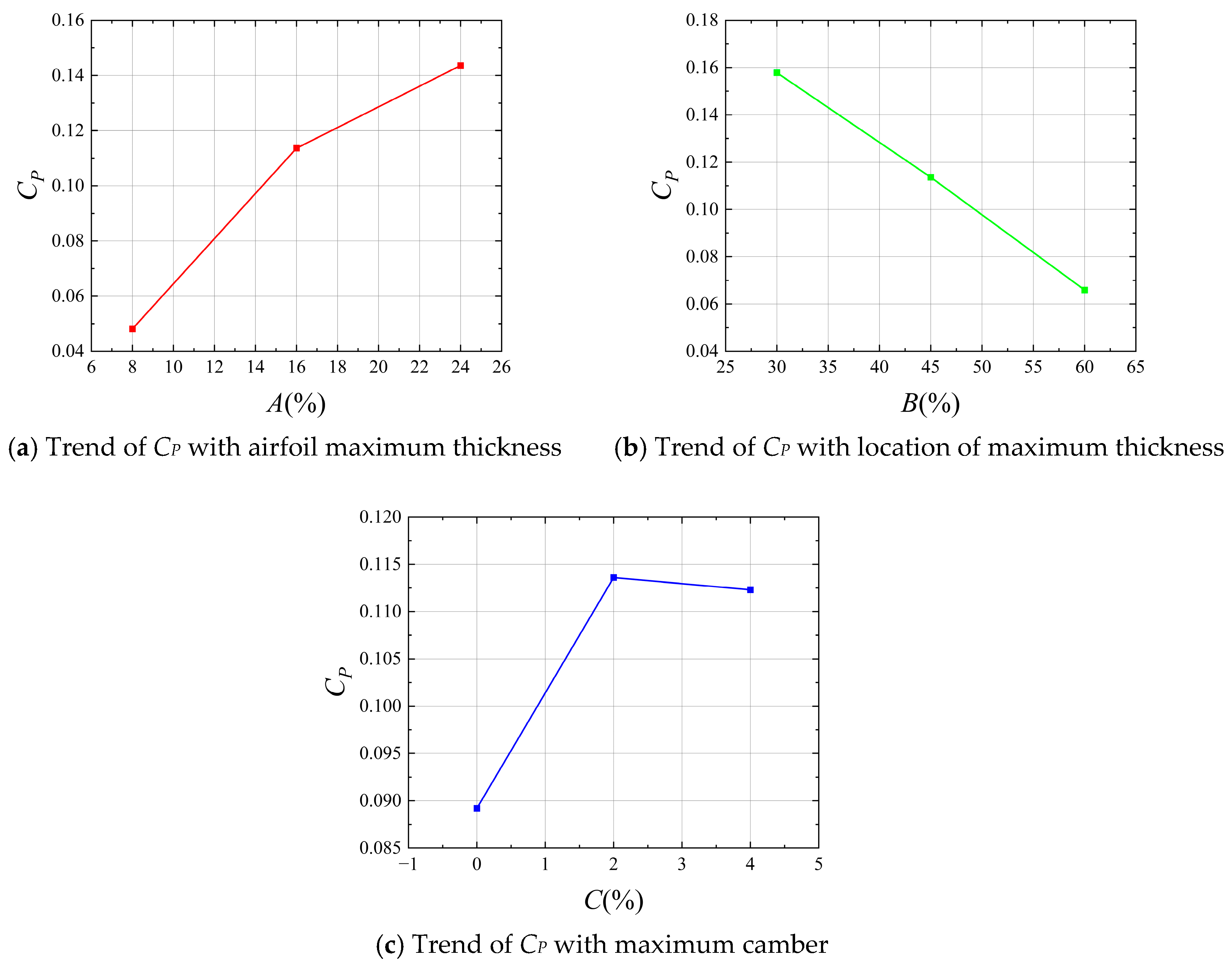

3.3.1. Main Effects Analysis of Variables

Figure 11 illustrates the regulatory trends of the three key airfoil parameters—Maximum Thickness (

A), Location of Maximum Thickness (

B), and Maximum Camber (

C)—on the power coefficient

CP, with the other two parameters held at their median values. As Maximum Thickness (

A) increases,

CP shows a significantly rising positive correlation. In contrast, as the Location of Maximum Thickness (

B) increases,

CP continuously decreases, indicating a negative correlation. For Maximum Camber (

C),

CP rapidly increases when

C rises from 0 to 2, but then slowly declines when exceeding 2, exhibiting an overall characteristic of “rising first, then stabilizing and decreasing.” These differential trends intuitively reflect the directional influence of airfoil geometric parameters on energy extraction efficiency, providing guidance for parameter adjustment in airfoil optimization.

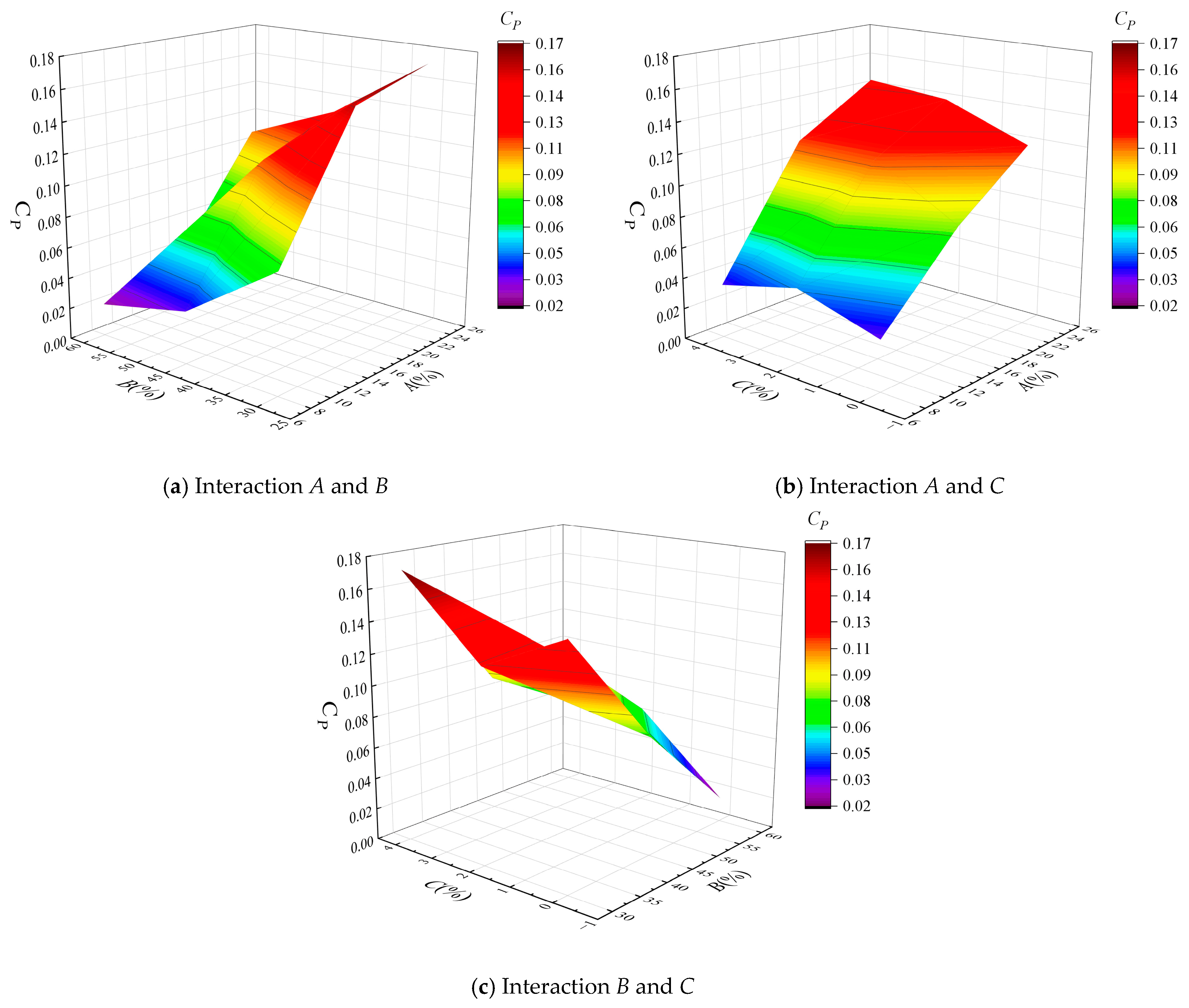

3.3.2. Analysis of Interaction Effects Among Variables

Figure 12 reveals the combined influence of pairwise interactions among airfoil parameters on the power coefficient

CP. In the

A-B interaction,

CP climbs significantly into a high-value region when

A increases and

B decreases (thickness located forward), highlighting that their opposing synergy has the most prominent effect on enhancing

CP. In the

A-C interaction, an increase in

A can maintain

CP in a relatively high range, while changes in

C have a gentler impact on

CP, indicating the dominant role of

A on

CP. In the

B-C interaction,

CP is higher when

B decreases and

C is within a moderate range, and deviating from this combination leads to a decrease in

CP, though the magnitude of influence is weaker than interactions involving

A. Overall, the optimal synergistic direction for improving

CP is “increasing

A, positioning

B forward, and maintaining

C at a moderate level.”

3.4. Results Analysis

Design-Expert 13 software was used to predict the optimal parameter combination for the rotor. The solution process yielded a total of 100 non-dominated solutions (Pareto solution set) that satisfied the constraints. To determine the global optimal design, the following screening procedure was implemented: (1) First, solutions where design variables were at extreme values were excluded based on engineering manufacturability. (2) Subsequently, from the remaining solutions, 5 candidate points with the highest predicted

CP were selected; their design variables are listed in

Table 10. (3) To overcome the prediction uncertainty of the surrogate model, independent, high-precision 3D CFD verification simulations were conducted for these 5 candidate points. A comparison between the simulated and predicted values is shown in

Table 11, with errors generally within 5%, demonstrating the reliability of the response surface model. The verification simulations used the same meshing and turbulence models as the response surface construction phase. (4) The verification results (

Table 11 and

Table 12) show that Optimized Foil 5 achieved a

CP of 0.1887, which is higher than the other candidate points and the original NACA 2414 baseline airfoil (

CP = 0.1480). This indicates that this point lies within a high-performance region where the response surface model fits well.

The above results demonstrate that the research framework established in this paper—comprising parametric design, response surface optimization, and high-fidelity verification—is highly effective and reliable. The engineering screening of hundreds of Pareto solutions and the direct CFD verification of the 5 candidate points not only ensured the robustness of the optimal solution but also confirmed the good predictive capability of the response surface model within the core design space (prediction error < 5.3%). The finally determined optimized airfoil (Optimized Foil 5), while keeping the location of maximum thickness largely unchanged, significantly increased both thickness and camber. Its power coefficient CP reached 0.1887, representing a substantial 27.5% improvement over the baseline NACA 2414 airfoil. This significant performance enhancement fully proves that systematic multi-parameter collaborative optimization can effectively overcome the performance bottlenecks of traditional airfoils under low flow velocity conditions, providing a new and effective approach for the blade design of vertical-axis tidal current turbines.

3.5. Research Limitations and Future Work

This study established an effective framework integrating parametric design, response surface optimization, and high-precision validation, successfully enhancing the power coefficient of the vertical-axis tidal current turbine. However, any research has its boundaries and potential for expansion. This section aims to objectively examine the limitations of the current work and propose possible future research directions accordingly.

3.5.1. Research Limitations

The limitations of this study primarily lie in three aspects: model simplification, design space, and validation scope.

Firstly, both the numerical simulations and experimental validation were based on uniform and stable inflow conditions. In reality, tidal currents in actual marine environments are characterized by unsteadiness, high turbulence intensity, and multidirectional variability. The steady turbulence model and uniform velocity inlet settings adopted in this study, while ensuring the controllability and repeatability of fundamental research, may not fully reflect the performance of the optimized airfoil under complex real sea conditions. Secondly, although the variables involved in the parametric optimization—maximum thickness, location of maximum thickness, and maximum camber—are core aerodynamic parameters, they fail to encompass more detailed geometric features such as leading-edge radius and trailing-edge shape. Consequently, the defined design space may not represent the complete space containing the global optimum. Finally, experimental validation was conducted only within a limited operational range of Reynolds numbers from 5.2 × 105 to 8.6 × 105, primarily comparing the key indicator of Tip Speed Ratio (TSR). The performance and robustness of the optimized airfoil under broader flow velocities, tip speed ratios (especially during low-speed start-up conditions), and varying turbulence intensities require further investigation.

3.5.2. Future Work

Based on the aforementioned limitations, future research can be deepened and expanded from the following three levels.

At the level of mechanism and modeling, future studies could employ higher-fidelity turbulence models such as Scale-Adaptive Simulation (SAS) or Large Eddy Simulation (LES), within Fluent 2024 R1, combined with advanced flow field measurement techniques like Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV). This approach would enable a more detailed revelation of the physical essence of how the optimized airfoil controls flow separation and utilizes vortex dynamics. At the level of optimization design, research can evolve towards multi-objective and high-dimensional development. On one hand, considerations for blade load, cavitation characteristics, and noise levels could be incorporated into the optimization objectives to achieve the co-design of performance and reliability. On the other hand, more flexible geometric parameterization methods could be introduced to expand the design space and explore innovative high-performance airfoils that break traditional paradigms. At the level of engineering validation, the final and most critical step is to test the optimized design in real or quasi-real environments. This includes conducting model experiments in circulating water channels simulating shear flows and oscillatory flows under complex conditions, and ultimately advancing to the fabrication of functional prototypes for long-term operational validation in controlled offshore test sites. This would complete the full cycle from numerical optimization to engineering application, providing more practical solutions for the blade design of vertical-axis tidal current turbines.