1. Introduction

Cavitation on propellers not only leads to a degradation of hydrodynamic performance but also causes structural material erosion on the blade surfaces due to “cavitation erosion.” Furthermore, the periodic “inception-collapse” process of cavitation significantly increases the high-frequency noise level in the surrounding flow field [

1]. Therefore, delaying cavitation inception on the blade surface or reducing the extent of the cavitation region is of great significance for improving the stealth and speed of ships.

Cavitation occurrence is determined when the pressure reduction coefficient of the propeller exceeds the cavitation number. The pressure reduction coefficient is influenced by factors such as the blade section geometry, angle of attack (αk), and position on the blade surface. Traditional metal propellers are typically considered non-deformable rigid bodies during operation; thus, their pressure reduction coefficient distribution is fixed from the design stage under specific conditions and is difficult to adjust. Xiong Ying [

2] employed a low-order panel method based on velocity potential to predict the cavity extent and volume of a propeller under unsteady conditions, noting that predicting the cavitation inception location should incorporate viscous fluid dynamics methods. Yang Qiongfang et al. [

3] utilized the Sauer cavitation model and a modified Shear Stress Transport (SST) turbulence model for cavitation bucket calculations. They proposed that cavitation inception can be judged when the pressure coefficient distribution at the blade tip section no longer changes with increasing cavitation number, and used the sheet cavitation inception curves at the 0.7R section on the blade back and the 0.4R section on the blade face as criteria for visible tip vortex cavitation inception on the back and face, respectively. Nhut Pham-Thanh [

4] conducted cavitation erosion tests on three-blade glass fiber composite propellers with three different resin matrices, finding that the main erosion areas were consistently located at 0.4R and 0.7R. Zheng Chaosheng et al. [

5] combined Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) numerical simulation with a cavitation tunnel test to study the cavitation characteristics of a PC456 metal propeller under oblique flow conditions. The results showed good agreement between the numerical simulations and experimental data, verifying the reliability of the current numerical method.

Theoretically, for a blade section of a specific geometric shape, reducing its pitch angle decreases the inflow angle of attack, thereby reducing the pressure reduction coefficient ζ. Lu Weichuan et al. [

6] verified this conclusion in a study on a two-dimensional hydrofoil. For composite propellers, their structural deformation characteristics influence cavitation performance [

7]. By rationally utilizing the anisotropic stiffness properties of composite materials and designing bend–twist coupling deformation that induces a reduction in pitch angle [

8], cavitation inception can be effectively delayed or the cavitation area reduced. The deformation field characteristics of a composite propeller are primarily determined by its layup parameters. Among the various layup parameters, the ply angle has the most significant impact on propeller performance, and changing the number of plies at the same angle does not significantly affect its strength and open-water performance [

9]. When a multi-angle layup scheme is adopted and the primary ply direction aligns with the propeller skew direction, the composite propeller tends to develop torsional deformation leading to pitch reduction [

10]. Songwen Dong et al. [

11] demonstrated in their study on composite hydrofoils that such structures can suppress sheet cavitation on the suction surface and tip leakage vortex cavitation, reduce flow field pressure fluctuations, and improve the lift-to-drag ratio. He [

12], in computations for a DTMB 4381 composite propeller, found that its adaptive deformation characteristics, the cavitation pattern change in the composite propeller was more gradual compared to the metal propeller, with a smaller impact on propulsive efficiency. Dan-dan Zhang et al. [

13] investigated the cavitation hydrodynamics of a composite propeller under non-uniform wake conditions, finding that its lower pressure fluctuations effectively reduced the impact of cavitation loads on the propeller. It is important to note that the configuration of current composite propellers is typically determined based on the geometry of the corresponding metal propeller. Considering that the FSI deformation of composite propellers is non-negligible [

14], their operating state changes after deformation, making direct performance comparison with metal propellers infeasible. Pre-deformation design of the composite propeller is thus required. Addressing this, the research team of Xiong Ying at Naval University of Engineering [

15,

16] employed a pre-deformation method for the structural design of composite propellers, finding that their hydrodynamic performance was comparable to the metal propeller under design conditions and superior under off-design conditions.

Currently, research on improving propeller anti-cavitation performance mostly focuses on optimizing the external flow field environment, often requiring the addition of appendages or adopting special structural designs. However, such methods may lead to issues such as deterioration of ship noise performance, reduction in propulsive efficiency, and increased manufacturing and maintenance costs. Considering the close relationship between cavitation inception and the inflow angle of attack, composite propellers can, through their inherent FSI deformation design, adjust the inflow angle of attack without relying on complex external structures, providing a new design approach for enhancing propeller anti-cavitation capability. In view of this, this paper takes the new benchmark model propeller PC456 as the research object, employs unidirectional composite layup and pre-deformation design, establishes a two-way FSI numerical algorithm based on CFD multiphase flow, analyzes the deformation field characteristics of the composite propeller under different ply angles, and investigates the influence of different deformation fields on its cavitation performance, thereby providing a theoretical basis and research foundation for the design of low-noise composite propellers.

In summary, the main innovations of this work lie in proposing an intrinsic material-based design approach—rather than relying on external appendages or complex structures—to actively control cavitation inception through tailored FSI deformation of composite propellers. Furthermore, this study systematically investigates the influence mechanism of ply angle on the deformation field and resulting cavitation performance, providing a novel theoretical basis for the design of low-noise composite propellers.

2. Numerical Methodology

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the numerical study, a high-fidelity numerical flow field model must be constructed, and a stable and efficient numerical solution strategy established. Accordingly, this work employs a global hexahedral structural grid to discretize the computational domain. Accounting for fluid viscous effects, appropriate turbulence and cavitation models, along with boundary conditions, are selected. The open-water performance and structural deformation field of the propeller are obtained by solving the steady-state FSI governing equations. Furthermore, the cavitation characteristics within a periodically non-uniform wake field are analyzed utilizing a transient FSI algorithm.

2.1. Governing Equations

Assuming the fluid is incompressible and the contribution of kinetic energy dissipation to internal energy can be neglected, the distributions of the fluid velocity and pressure fields can be determined by solving only the mass and momentum conservation equations:

where

u denotes the fluid velocity within the control volume,

t is time,

ρ is the fluid density,

p is pressure,

μ is the dynamic viscosity coefficient, and

V represents the body force acting on the fluid micro-element within the control volume. The subscripts

i,

j = 1, 2, 3; an overbar “¯” on a physical symbol denotes the time-averaged mean quantity obtained through Reynolds averaging.

M,

C, and

R are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively;

Ma,

Ca, and

Ra are the added mass, added damping, and added stiffness matrices, respectively;

s,

, and

represent the displacement, velocity, and acceleration vectors of the finite element mesh nodes, respectively; and

F(

t) is the nodal force vector matrix, comprising hydrodynamic and centrifugal forces.

Equations (1) and (2) are the fluid continuity and momentum equations, used to solve for the fluid velocity and pressure fields. The Reynolds stress term

, introduced by employing the RANS approach, is resolved using the SST k-ω turbulence model [

17]. This turbulence model adequately accounts for the transport of turbulent shear stresses and automatically switches between the k-ε and k-ω models based on the proximity to the wall, thereby offering a favorable balance between computational accuracy and efficiency.

Equation (3) is the governing equation for transient FSI. When performing a steady-state FSI solution, the time-dependent velocity term

and acceleration term

on the left-hand side of the equation both become zero. Consequently, Equation (3) can be simplified to

2.2. Computational Domain Modeling

An accurate grid model is fundamental to ensuring both the accuracy and efficiency of the CFD approach. Given the distinct characteristics of the fluid and structural physical fields in numerical simulations, differentiated grid generation strategies are required. Factors such as element size, cell count, interface treatment, and local refinement must be comprehensively considered to ensure smooth transfer of key physical quantities like pressure and displacement across the coupling interface. The geometric parameters of the PC456 metal propeller are listed in

Table 1.

- (1)

Fluid Domain Modeling

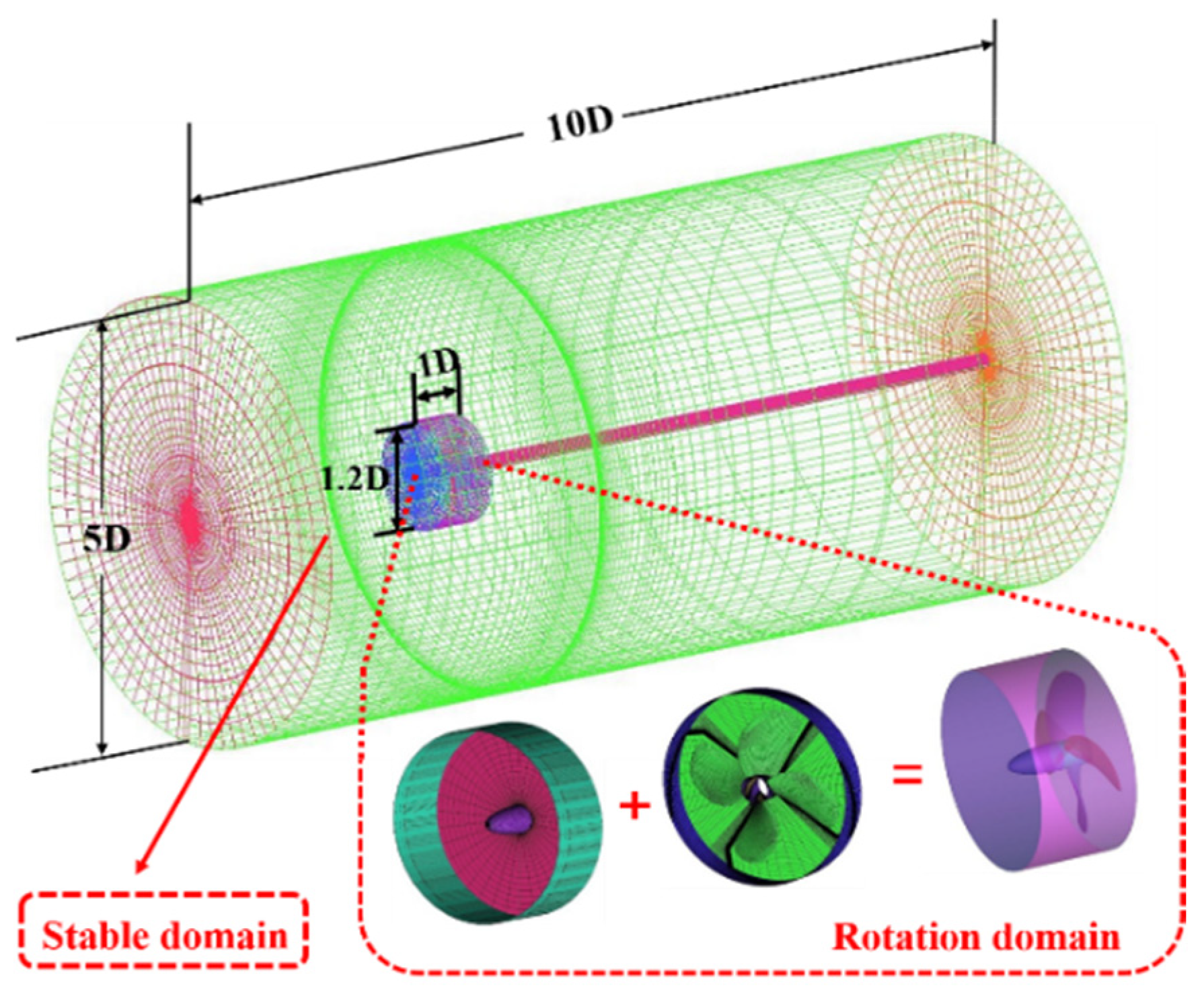

To accurately simulate the hydrodynamic characteristics of the composite propeller, a sufficiently large computational domain is required to minimize the influence of flow field boundaries. At the same time, adequate resolution must be ensured in the flow field region near the propeller blades. Therefore, the construction of the flow field grid must balance computational accuracy and efficiency. In this study, the fluid domain is divided into a stationary domain and a rotating domain. The stationary domain is a cylindrical region with a radius of 5D and an axial length of 10D, discretized using relatively larger grid cells to control the total mesh count. The rotating domain, a cylindrical region with a radius of 1.2D and an axial length of 1D, is meshed with finer cells to accurately capture the flow details around the blades. The grid for the fluid computational domain is shown in

Figure 1. To satisfy the initial boundary conditions required for solving the governing equations, a velocity inlet and a pressure outlet are defined in the computational domain.

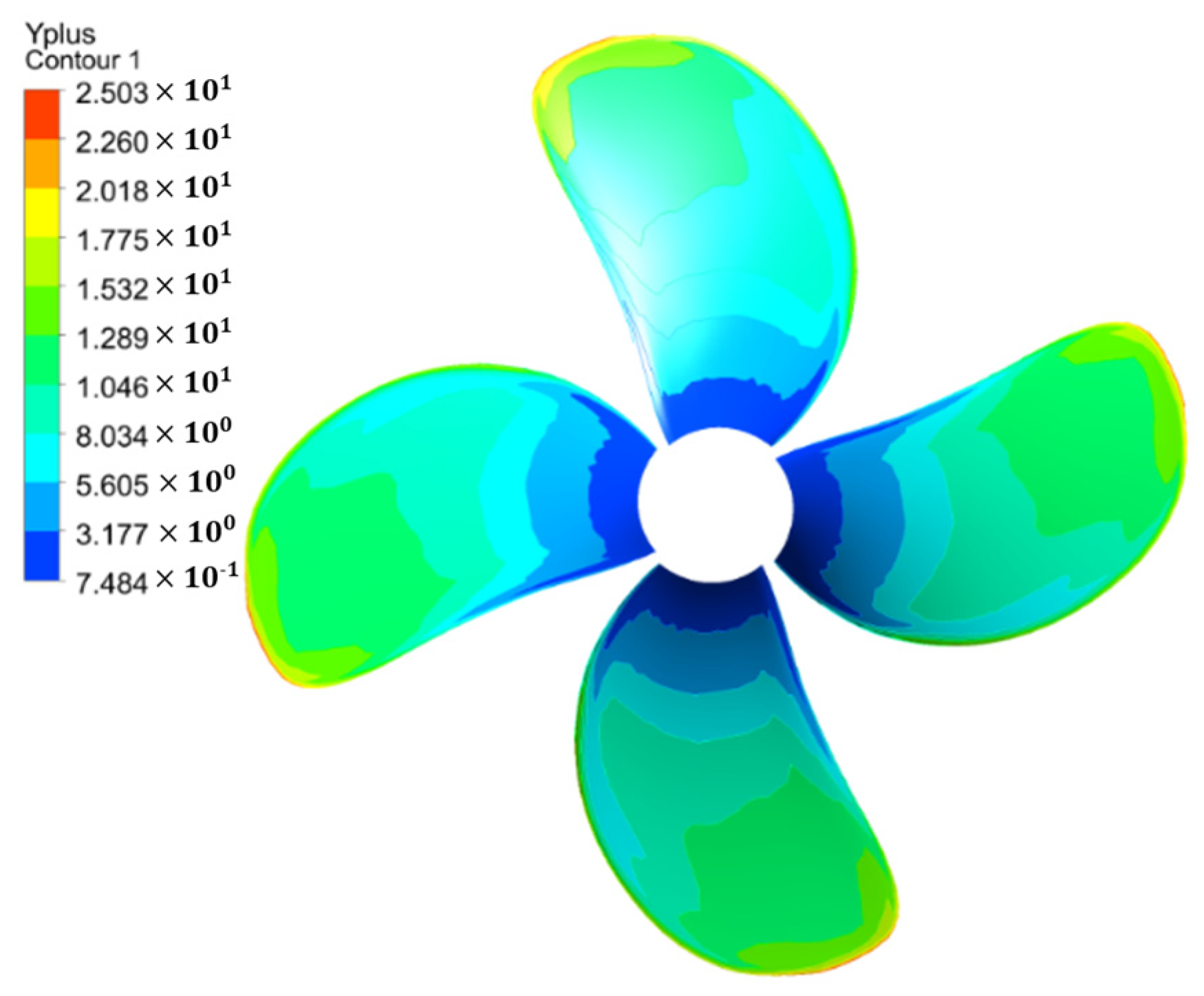

Considering the influence of fluid viscosity near the blade surfaces, a boundary layer mesh is applied in the near-wall region. Among these settings, the height of the first grid layer is particularly critical for the accuracy of the near-wall flow simulation. In CFD methods, the dimensionless parameter Y+ is commonly used to characterize the relative height of the boundary layer mesh. A lower Y+ value enables more accurate resolution of the viscous sublayer flow structures but also significantly increases computational resource consumption. Especially after introducing cavitation models and FSI effects, an excessively small first-layer height can easily lead to mesh distortion in high-curvature regions like the blade tip, causing simulation failure. After comprehensive consideration, the height of the first grid layer on the blade surface is set to 0.03 mm. The corresponding Y+ distribution under the operating condition of advance coefficient J = 0.6 and rotational speed

n = 20 rps is shown in

Figure 2, indicating Y+ values ranging from 0 to 30. Values in other tested conditions also remain within this range, meeting the basic requirement (Y+ ≤ 300) for the automatic wall function in the CFX solver.

- (2)

Structural Modeling

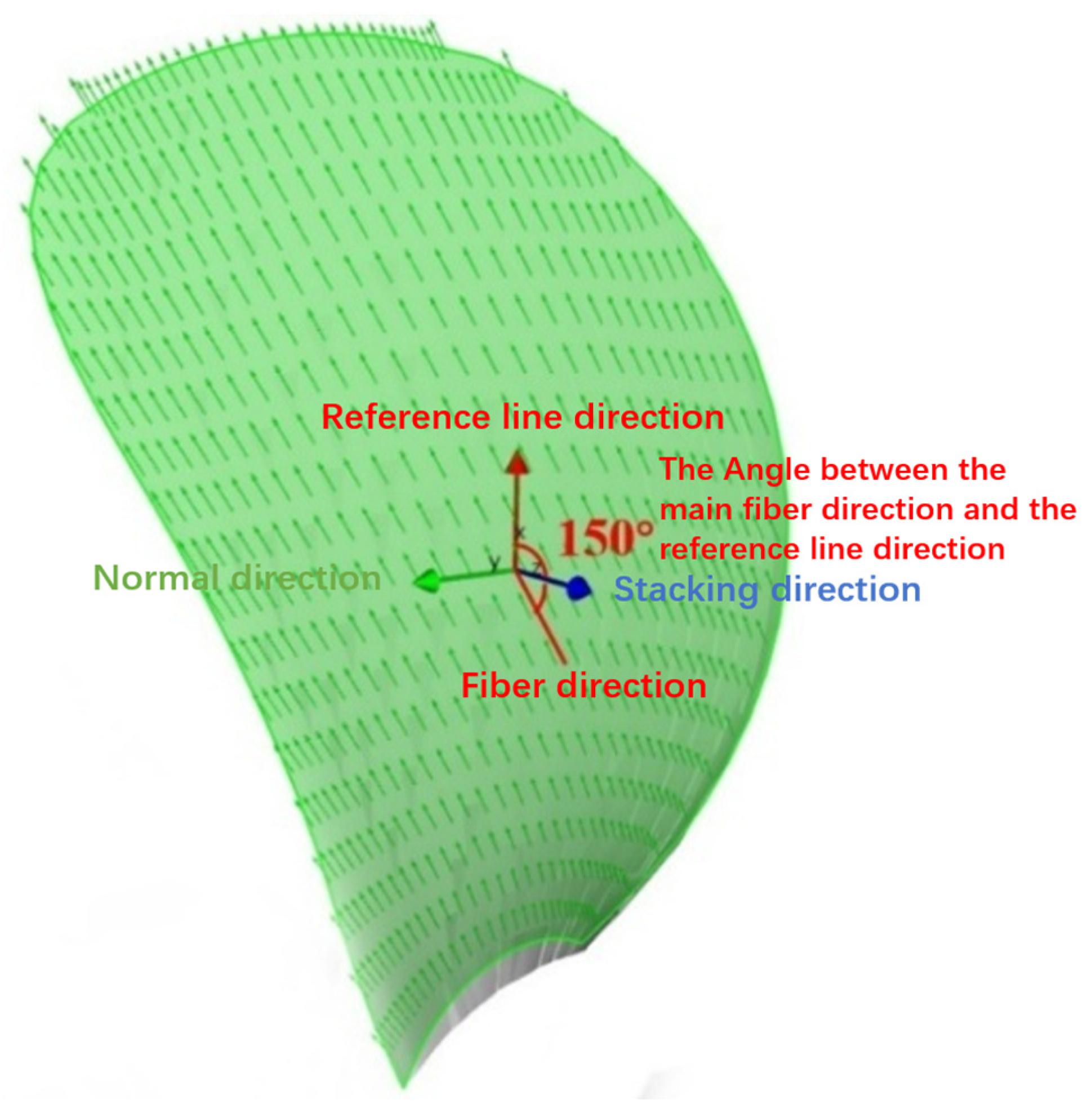

Unlike the fluid domain, which requires high grid density, the structural domain can achieve an accurate description of the “pressure–deformation” relationship with a relatively limited number of elements. The key to efficient solution lies in structural modeling that adequately reflects the geometric features and material properties, thereby ensuring that the computed deformation closely approximates the real structural response. Based on the Workbench ACP module, the composite propeller model is constructed using the blade camber surface as the reference for stacking plies towards the pressure side and the suction side. The ply elements are trimmed and conformed to the blade’s external contour, resulting in a model that more closely represents actual manufacturing processes, as shown in

Figure 3. This module can be integrated with the CFX fluid solver within the same Workbench platform, effectively enhancing the stability and computational efficiency of the FSI algorithm.

2.3. Grid Independence Study

The fundamental principle of the Finite Element Method (FEM) originates from the mathematical concept of integration, achieving approximate representation of continuous physical quantities through discretization and elemental summation. Generally, a greater number of grid elements leads to higher simulation accuracy, but also entails a significant increase in computational resource consumption. Therefore, conducting a grid independence study is a necessary step to determine a mesh configuration that balances computational accuracy and efficiency.

In a grid independence study, the computational domain mesh is typically categorized into three densities: coarse, medium, and fine. The convergence behavior of the numerical results with increasing mesh density is assessed by comparing the errors between the computed hydrodynamic performance and experimental measurements. To ensure a scientifically valid verification process, the variation in mesh count must follow the principle of controlled variables. This means the height of the first grid layer in the boundary layer should be consistent across the three mesh sets. This isolates the effect of mesh density on the results by eliminating potential interference from the turbulence model’s response to near-wall resolution. Furthermore, the grid sizes at the interface between the rotating and stationary domains should be approximately matched to ensure stable and complete data transfer across the interface.

The aforementioned analysis indicates that determining a suitable first-layer grid height is a prerequisite for performing the grid independence study. Preliminary calculations revealed that, after accounting for multiphase flow and FSI effects, an excessively small first-layer height and an overly large number of grid elements substantially increase computational resource demands and can even lead to solution divergence. Consequently, this study first employed a coarse mesh model with a total of 470,000 elements (330,000 in the rotating domain) to compute the cavitation hydrodynamic performance for first-layer heights of 0.005 mm, 0.01 mm, 0.02 mm, 0.03 mm, 0.05 mm, and 0.1 mm. The results indicated that the calculation converged only when the first-layer grid height was greater than or equal to 0.03 mm.

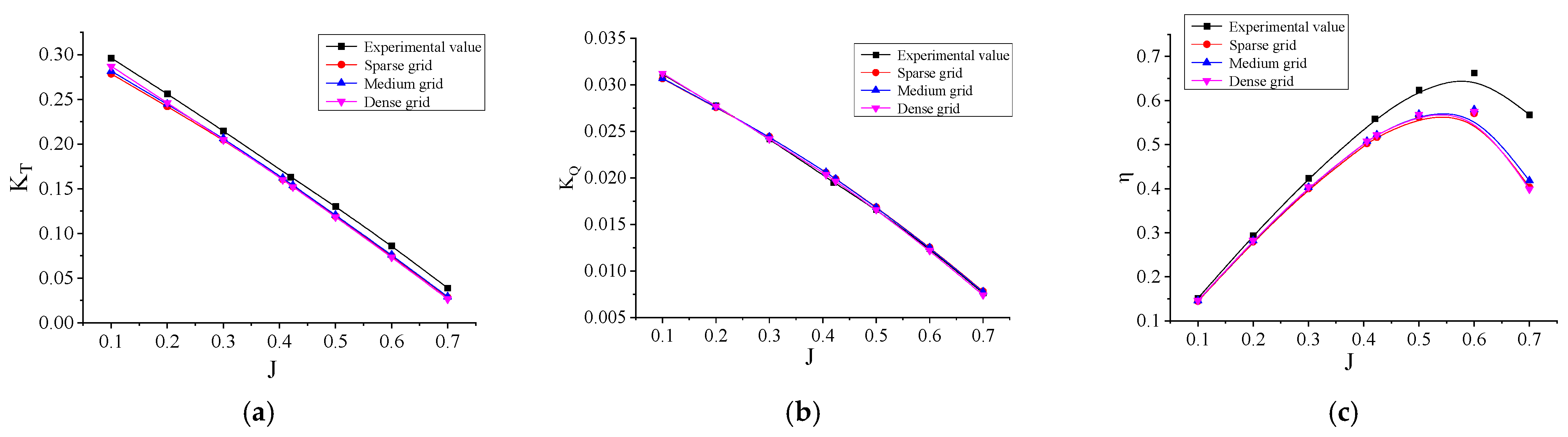

Subsequently, the influence of the total grid number on computational convergence was further investigated, with the results presented in

Table 2. It can be observed that both the total number of grid elements and the number within the rotating domain significantly impact convergence. Cases 1 to 6 show that calculations tend to diverge when the total grid count exceeds 2 million. A comparison between Case 5 and Case 6 demonstrates that, for a similar total mesh count, the number of elements in the rotating domain has a more critical effect on convergence. This is primarily because the rotating domain contains complex viscous boundary layer structures and unsteady flow features, demanding higher mesh resolution. Given finite computational resources, the overall mesh scale must be reasonably controlled to ensure accuracy in these critical regions. In contrast, the flow in the stationary domain is relatively uniform and steady, exhibiting lower sensitivity to its grid count; thus, its mesh can be moderately refined to enhance overall simulation accuracy. Cases 6, 8, and 9 from

Table 2 were selected for the final grid independence verification. A comparison between their computed hydrodynamic performance and experimental values is shown in

Figure 4. The experimental data were obtained from a major fundamental research project on “Cavitating Flow in Water and Control Applications” undertaken by the China Ship Scientific Research Center.

Overall, the open-water performance results obtained with the three mesh densities indicate that denser grids yield results closer to the experimental values. The computational error generally increases with the advance coefficient (J), with the maximum efficiency occurring near J = 0.6. The torque coefficient shows good agreement with experimental data, whereas the thrust coefficient exhibits larger errors at high advance coefficients, consequently leading to noticeable deviations in the computed efficiency within this range.

Regarding the torque coefficient, all three mesh models maintain good consistency with the experimental values. Under the fine mesh configuration, the maximum error is 2.7% at J = 0.7. For J ≤ 0.5, the average error is 0.15%, with a minimum error of only 0.02%, indicating that the selected first-layer grid height setting enables reasonably accurate prediction of the experimental results. For the thrust coefficient, the fitted curves of the computed and experimental values are essentially parallel, with the parallelism improving with mesh refinement. Under the fine mesh, the computed thrust coefficient values are consistently lower than the experimental values by approximately 0.01 across all advance coefficients. Since the thrust coefficient decreases with increasing advance coefficient, the experimental value drops to 0.0389 at J = 0.7. At this point, the fixed deviation of 0.01 leads to a large relative error, which is the primary reason for the significant thrust coefficient error observed at high advance coefficients.

In summary, although a certain deviation exists between the computed and experimental thrust coefficients, the progressive improvement in the parallelism of the fitted curves with mesh refinement suggests that this deviation likely stems primarily from a systematic error associated with the selected turbulence model. Considering the convergent behavior of the torque coefficient with increasing mesh density, it can be concluded that the present grid independence study has achieved its intended objective. To ensure the accuracy of subsequent FSI calculations, the fine mesh model is selected as the basis for further numerical analysis in this paper.

2.4. Validation of Cavitation Performance Calculations

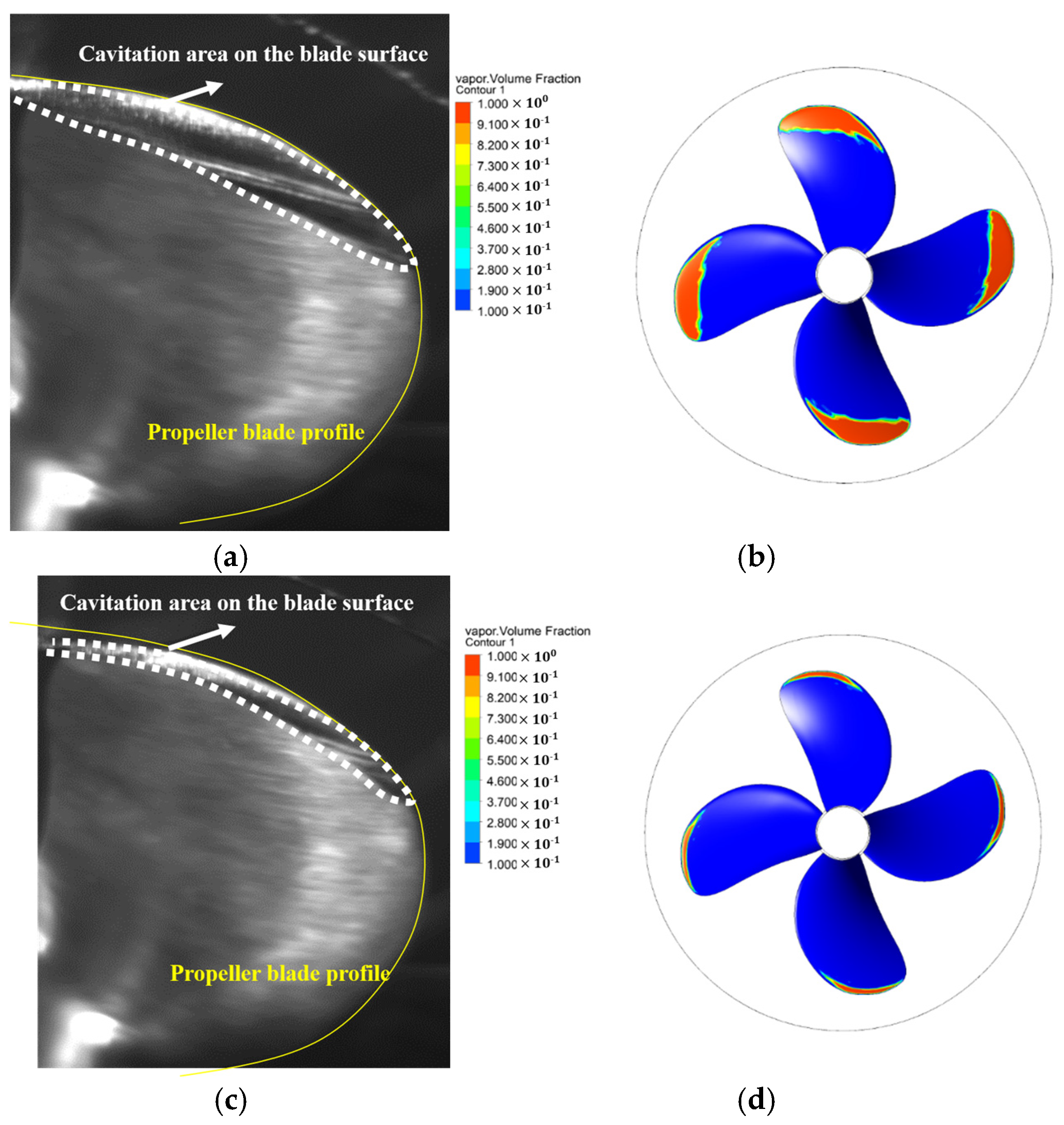

The Rayleigh–Plesset cavitation model was employed in the CFX solver to simulate cavity patterns. Two experimental conditions (Case 1: J = 0.406, σ = 7.27; Case 2: J = 0.424, σ = 8.49) were selected to validate the numerical methodology. With the saturation vapor pressure set to 3169 Pa at 25 °C and using the inlet velocity as the characteristic velocity (V = 2.03 m/s for J = 0.406; V = 2.12 m/s for J = 0.424), the corresponding far-field pressures were determined to be 18,148.47 Pa for Case 1 and 22,190.49 Pa for Case 2 based on the cavitation number definition ().

Compared to open-water conditions, consideration of cavitation effects revealed significant changes in hydrodynamic performance. For Case 1, the thrust coefficient decreased by 0.5%, while the torque coefficient increased by 5.6%, resulting in a 5.7% reduction in efficiency. For Case 2, the thrust coefficient decreased by 1.3%, the torque coefficient increased by 5.6%, and efficiency decreased by 6.5%. This trend indicates that during the incipient cavitation stage, the effect on thrust remains relatively limited, whereas the impact on torque is more pronounced, consequently leading to diminished propulsive efficiency.

The numerical results of cavity patterns, represented by the 0.1 isosurface of vapor volume fraction, are depicted in

Figure 5. Comparison with experimental observations demonstrates good agreement in both the extent and distribution of cavities between numerical predictions and measured data [

18]. This agreement verifies the reliability of the fluid dynamics approach adopted in this study for cavitation simulation.

3. Pre-Deformation Design of the Composite Propeller

When designing composite propellers based on a known metal propeller geometry, the structural deformation under FSI effects must be considered, as it may cause the hydrodynamic performance at the design operating point to deviate from the optimum. Therefore, a reverse pre-deformation must be applied to the composite propeller so that its deformed geometry and hydrodynamic performance under the design condition match those of the metal propeller. It is important to note that pre-deformation design possesses two key characteristics: “propeller model uniqueness” and “operating condition uniqueness.” Propeller model uniqueness means that the required pre-deformation amount differs for different composite propellers. Even for propellers of the same base model, differences in material properties, fiber layup patterns, and structural design will alter their FSI-induced deformation fields, necessitating corresponding adjustments to the pre-deformation. Operating condition uniqueness refers to the fact that the deformation response of the same composite propeller varies under different operating conditions. Pre-deformation is typically designed for the specific design operating point, while its hydrodynamic performance under off-design conditions is evaluated to expand its efficient operating range, aiming to maintain or even improve hydrodynamic performance across a wider range of conditions.

3.1. Determination of the Deformation Field

The ply angle is a critical factor influencing the hydrodynamic performance of composite propellers. Fiber-reinforced polymer composites exhibit significant directionality in properties such as stiffness, modulus, and damping. Combined with the propeller’s geometric parameters, the deformation field can be controlled to optimize hydrodynamic performance. This study uses the PC456 metal propeller as the benchmark, which has a skew angle of 20°. T700 carbon fiber was selected, and unidirectional layups were designed at 30° intervals within the 0–180° range to systematically investigate the deformation fields and hydrodynamic response under different ply angles. The ply angle is defined as the angle between the primary fiber direction and the blade reference line, positive clockwise when facing the pressure side of the blade. Based on this, composite propellers with representative deformation characteristics were selected for pre-deformation design. The carbon fiber material parameters are listed in

Table 3.

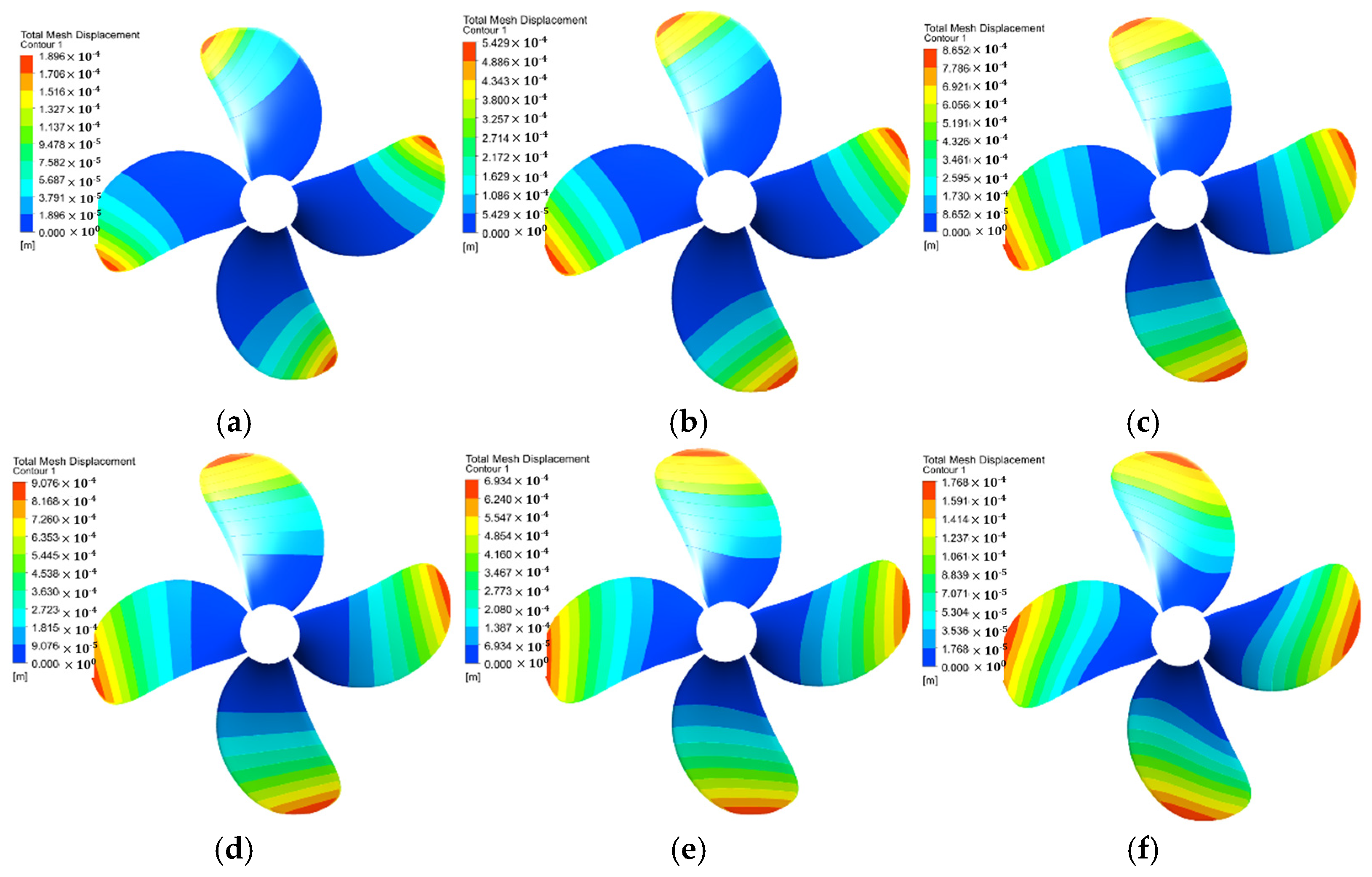

Preliminary hydrodynamic calculations indicated that the PC456 propeller achieves peak hydrodynamic efficiency at an advance coefficient J = 0.6 and rotational speed

n = 20 rps. The open-water performance of composite propellers with different ply angles was computed under this condition, with results presented in

Table 4, and the corresponding deformation field nephograms are shown in

Figure 6.

As the ply angle increases, the open-water performance parameters of the composite propellers first increase and then decrease, with the maximum values consistently occurring at the 120° ply angle. By analyzing the displacement distribution at the same radius from the deformation nephograms, it can be inferred that the deformation at the leading edge is greater than at the trailing edge for this case, resulting in an increased pitch angle and consequently a higher thrust coefficient compared to the metal propeller. The minimum performance values occur at the 0° ply angle, where the leading edge deformation is less than the trailing edge deformation, the pitch angle decreases, and the thrust coefficient is correspondingly reduced. To leverage the advantages of composite propellers in vibration and noise reduction, a deformation field that reduces the pitch angle is desirable to minimize thrust fluctuations in non-uniform wake fields. Therefore, the composite propeller with the 0° ply angle was selected as the target design. Simultaneously, the deformation fields of the 90° and 150° ply angles are also representative. At 90°, the primary fiber direction is approximately perpendicular to the blade reference line, resulting in negligible torsional deformation and a deformation pattern similar to a cantilever beam. At 150°, the bend–twist deformation trend is nearly radially symmetric to that of the 0° case, exhibiting opposite deformation characteristics. Therefore, the 90° and 150° ply propellers were designated as control groups, studied alongside the target 0° propeller to investigate cavitation performance under different deformation fields.

3.2. Pre-Deformation Design Procedure

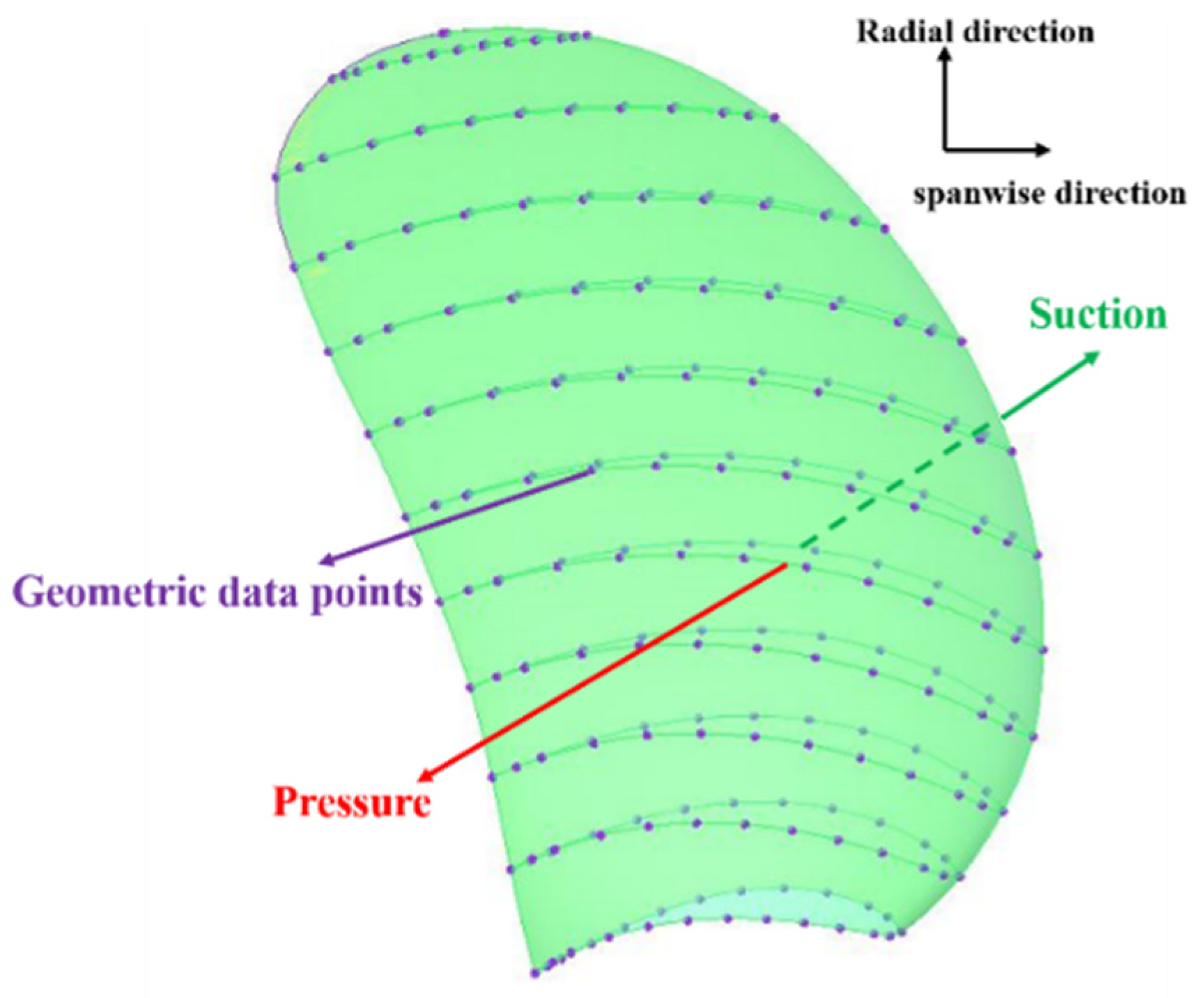

The core of the pre-deformation design for composite propellers lies in accurately extracting the coupled deformation and applying it in reverse, a process involving substantial geometric modeling and mesh regeneration. This study employed secondary development of the computational software to streamline the modeling process and improve design efficiency.

Prior to the initial FSI calculation, the undeformed composite propeller was parametrically modeled. For a single blade geometry, a set of 13 (spanwise) × 11 (chordwise) offset points were defined on both the pressure and suction sides within a Cartesian coordinate system, capturing their 3D coordinates (

Figure 7). Subsequent deformation analysis was based on these points. Given the limitations of the CFD-Post module in batch-processing displacement data of offset points, VBA programming language was used to generate CCL command streams embedded into the monitoring procedure. This enabled real-time monitoring and batch export of the displacement for each offset point during the FSI calculations, balancing deformation assessment efficiency with systematic data processing. After the initial FSI calculation converged, the computed displacement vectors of the offset points were applied in reverse to the original geometry, completing the first pre-deformation modeling step. A subsequent FSI calculation was then performed on the pre-deformed propeller to evaluate whether its hydrodynamic performance recovered to the level of the metal propeller.

Based on the results of the initial pre-deformation, the first data point—with hydrodynamic performance as the independent variable (

X-axis) and pre-deformation amount as the dependent variable (

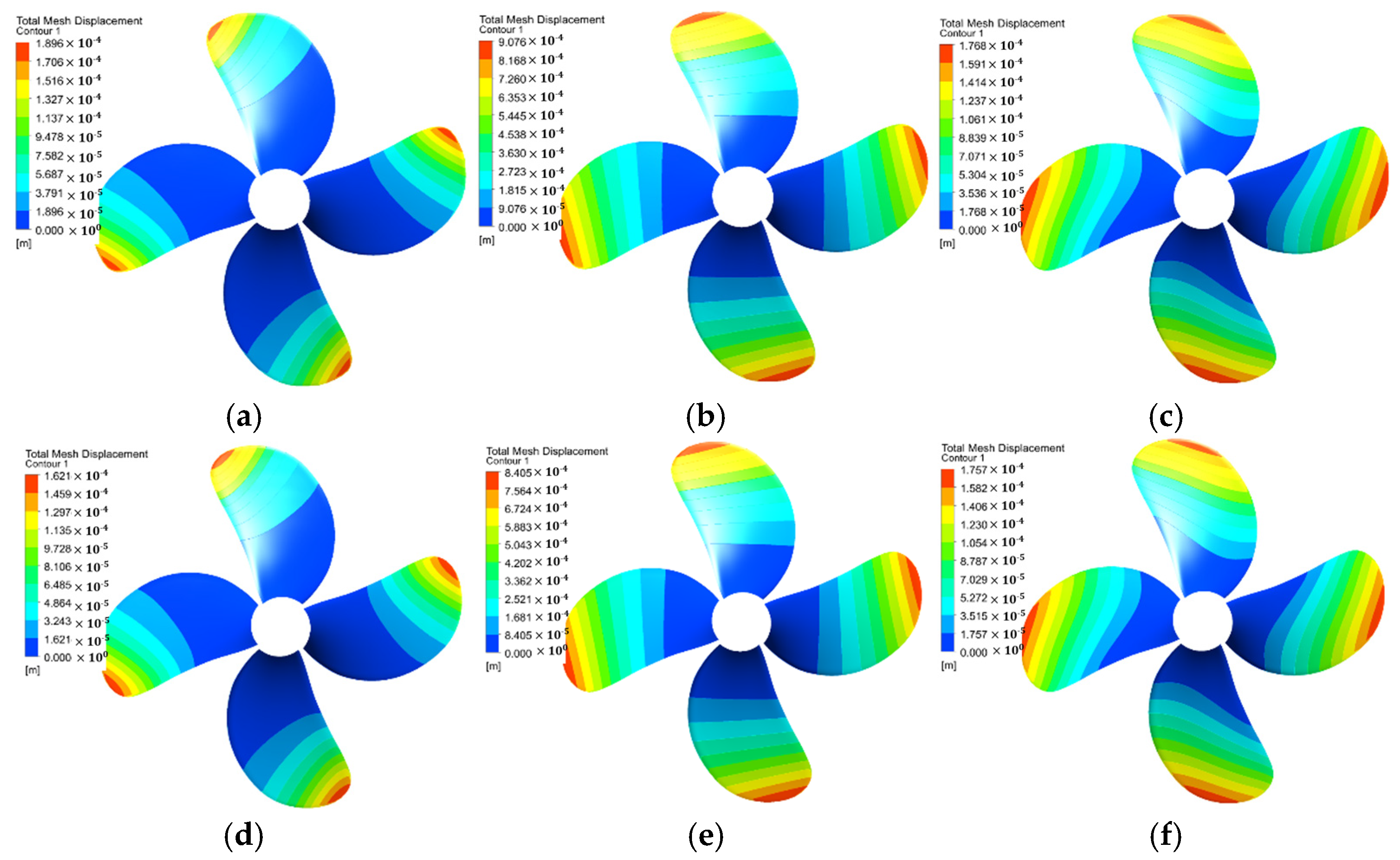

Y-axis)—was obtained. The Lagrangian interpolation formula was used to estimate the required pre-deformation amount for the second iteration. A second pre-deformed propeller was created and its open-water performance evaluated, yielding the second data point. If the design requirements were still not met, the iterative calculation continued. As the number of data points increased, the fitting accuracy of the interpolation model for the relationship between performance and deformation amount gradually improved, ultimately yielding the pre-deformation amount that enabled the composite propeller’s performance to match the metal propeller’s at the design condition. A comparison of the deformation fields before and after the final pre-deformation is shown in

Figure 8, indicating that the deformation trends remain fundamentally consistent, with only minor differences in magnitude.

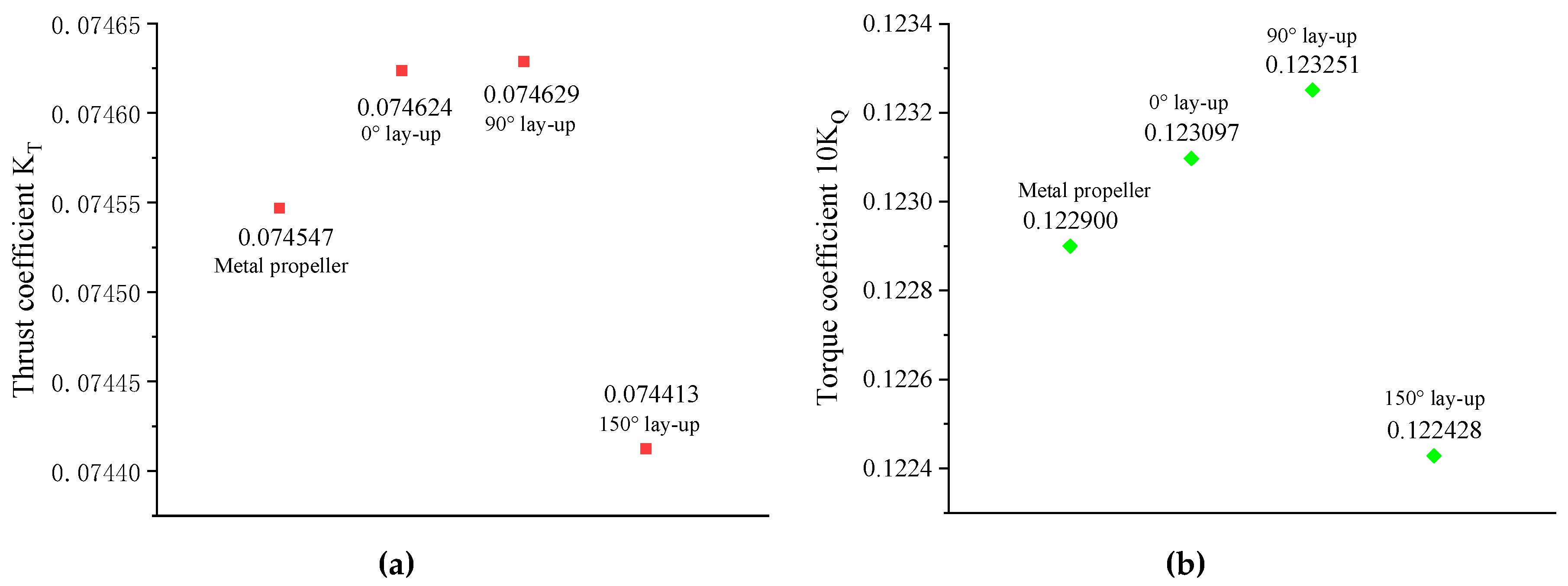

Open-water performance calculations were conducted for the three pre-deformed composite propellers under the condition of J = 0.6 and

n = 20 rps, with the results presented in

Table 5. Compared to the metal propeller, the maximum deviation in both the thrust coefficient and torque coefficient occurred for the torque coefficient of the 150° ply angle propeller, being only 0.38%. This deviation is negligibly small, necessitating the exclusion of the influence of software computational precision on the error analysis. By plotting the scatter distribution of the thrust and torque coefficients (

Figure 9), it was observed that both coefficients exhibited synchronous increasing or decreasing trends relative to the metal propeller’s performance. This indicates that the computational precision is higher than the level of random errors, which would otherwise manifest as irregular random fluctuations.

Performance differences between the three composite propellers and the metal propeller are small; the relative deviation of the torque coefficient is generally higher than that of the thrust coefficient. According to the blade element thrust and torque integration equations [

18]:

The above equations indicate that, for a given inflow velocity and rotational speed, the thrust and torque of a defined blade element are primarily influenced by the pitch angle

β1 (where

β1 is the hydrodynamic pitch angle considering induced velocity). However, the degree of influence of

β1 on thrust and torque is not identical and requires further analysis. Here, the relationship between the thrust and torque equations—which contain the pitch angle parameter as given by Equation (6)—is analyzed based on Equation (5).

Let

x = tan

β1. Since

β1 typically ranges from 2° to 10°, 0 <

x < 0.5. For a practical propeller in a real fluid, the drag-to-lift ratio falls within 0 <

ε < 1. The above expression can be simplified to

Considering the range of x and the properties of the parabolic function, it can be demonstrated that for x ∈ (0, 0.5), f(x) > 4 > 1. This result indicates that the influence of the pitch angle on torque is significantly greater than its influence on thrust. The simulation results agree well with this theoretical relationship.

4. Steady FSI Cavitation Characteristics of the Composite Propeller Under Different Deformation Fields

The pre-deformation design of composite propellers is explicitly tailored for specific operating conditions (e.g., design rotational speed and advance speed). However, during actual navigation, propellers frequently undergo variations in rotational speed and inflow velocity, causing the operational advance coefficient to typically fluctuate around the design value. Consequently, in addition to evaluating the cavitation characteristics of pre-deformed composite propellers under the design condition, it is essential to investigate their anti-cavitation performance under fixed advance coefficients with varying rotational speeds and inflow velocities.

4.1. Cavitation Characteristics at the Design Condition

Given the absence of a cavitation bucket diagram for this new propeller type as a reference, this study focuses on analyzing the cavitation characteristics of the aforementioned three pre-deformed composite propellers under the design condition (J = 0.6,

n = 20 rps). First, steady-state cavitation hydrodynamics calculations were performed for the metal propeller. By progressively reducing the ambient pressure until cavitation inception occurred, the corresponding ambient pressure was determined to be 0.2 atm, resulting in a freestream cavitation number

σV = 3.81. Under this condition, steady-state FSI open-water performance calculations were conducted for the three pre-deformed composite propellers, with the results summarized in

Table 6.

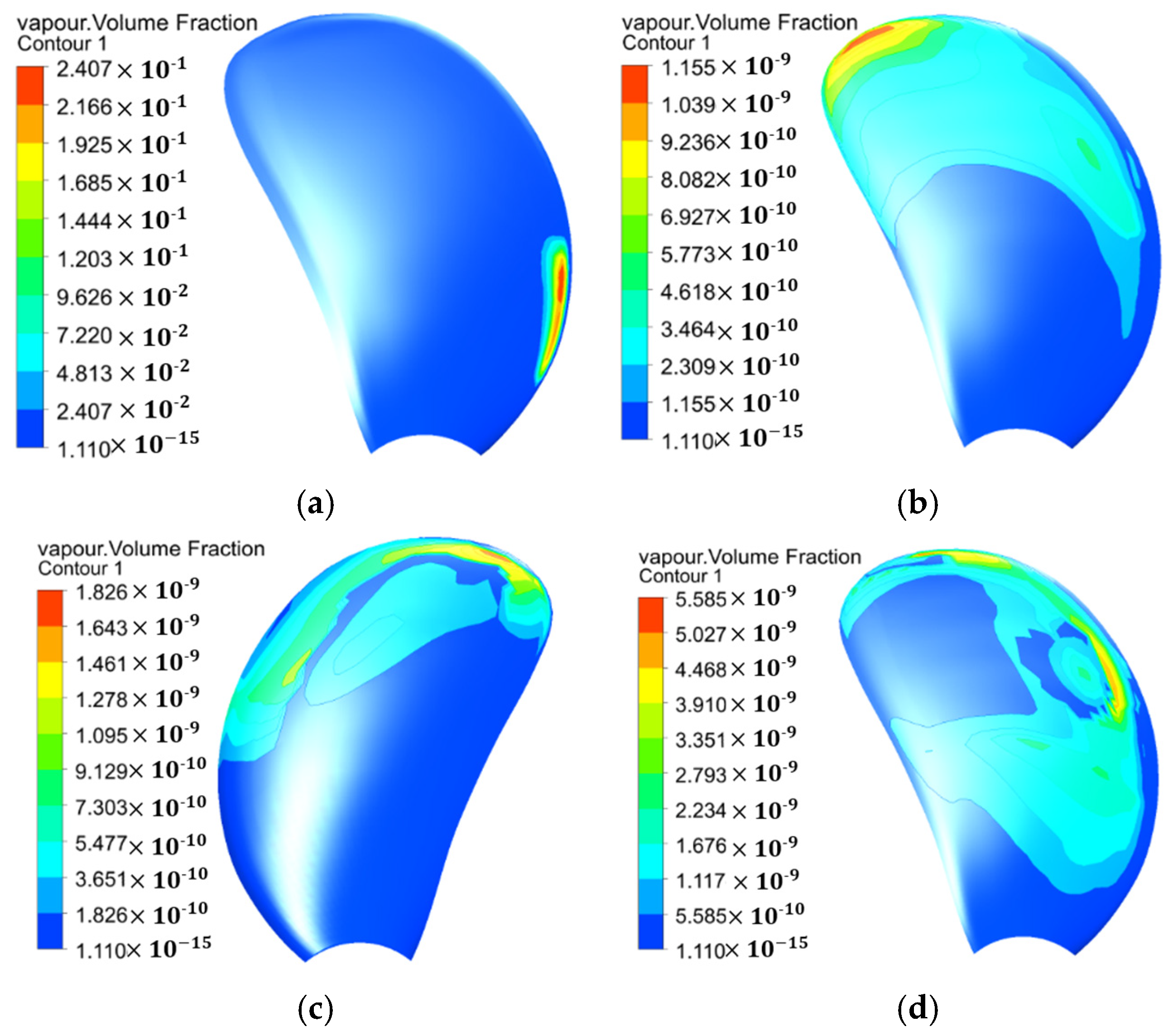

Notably, the hydrodynamic performance of the metal propeller did not decrease but instead increased slightly during the cavitation inception stage. The underlying reason is that although cavitation induces some hydrodynamic loss, the volume of incipient cavitation is small, resulting in limited loss. Simultaneously, the movement of cavities towards low-pressure regions increases the flow velocity past the blade sections, and the resulting pressure differential gain partially compensates for the performance loss. Therefore, at the cavitation inception stage, the overall hydrodynamic performance of the propeller shows no significant degradation and may even exhibit a slight improvement. Under the same cavitation inception condition, the three composite propellers also showed an increasing trend in hydrodynamic performance. However, this alone cannot confirm whether cavitation occurred on them; further analysis combined with cavity pattern plots (

Figure 10) is necessary.

The cavity pattern plots reveal that the incipient cavitation on the metal propeller is located in the mid-chord region of the pressure side near the blade root, consistent with the judgment at the 0.4R location on the blade face reported in the literature [

3]. Its maximum vapor volume fraction (i.e., the ratio of cavity volume to cell volume in the mesh) is 0.2418, indicating that the cavity has reached a visually observable level. In contrast, the maximum vapor volume fractions for the three composite propellers are all on the order of 10

−9, far below the visualization threshold, demonstrating their superior anti-cavitation performance compared to the metal propeller. Further comparison of the cavitation inception trends among the three composite propellers shows that the target deformation field propeller (0° ply angle) has the lowest maximum vapor volume fraction (1.155 × 10

−9), indicating the best anti-cavitation performance. Furthermore, the incipient cavity location for this propeller is at the blade tip, suggesting it might be most susceptible to tip vortex cavitation inception. The 150° ply angle propeller exhibits the worst anti-cavitation performance, with the incipient cavity location shifted upwards along the leading edge, indicating that deformation leading to an increased pitch angle, while potentially beneficial for hydrodynamics, is detrimental to anti-cavitation performance. The 90° ply angle propeller, characterized by a deformation field lacking significant bend–twist coupling and having the largest deformation magnitude, exhibits a pressure distribution different from the other two. Its cavitation is likely to initiate at the blade tip on the pressure side, and its anti-cavitation capability and hydrodynamic performance rank between the other two composite designs. In summary, the target deformation field propeller (0° ply angle) demonstrates the best overall performance in both open-water characteristics and anti-cavitation capability.

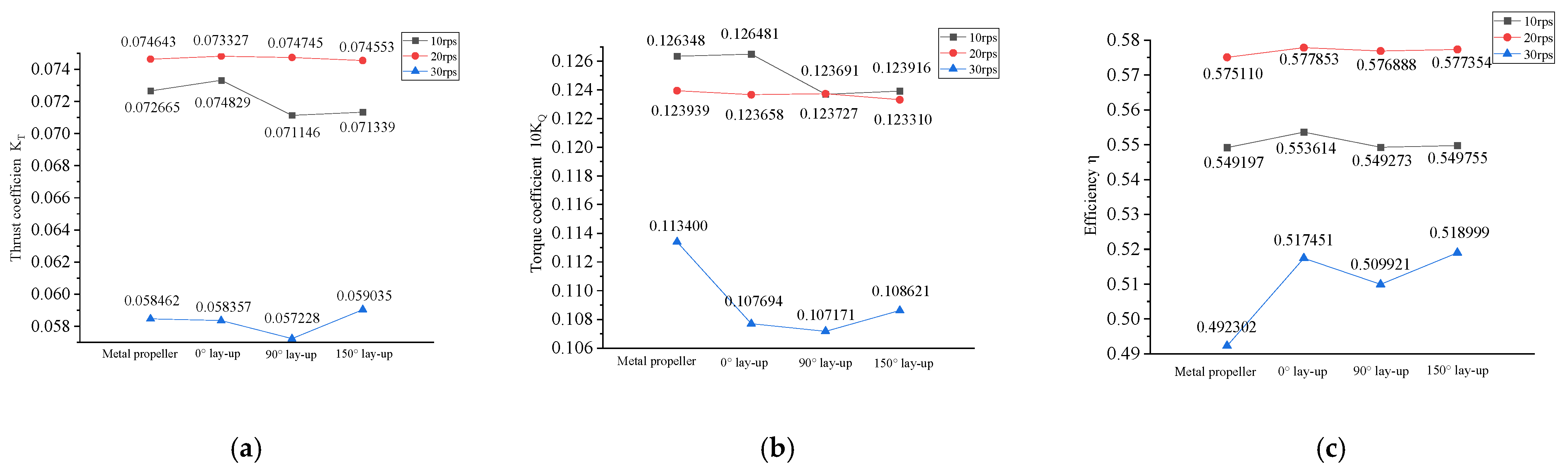

4.2. Cavitation Characteristics Under Variable Rotational Speed and Inflow Velocity

During ship navigation, speed changes are often achieved by adjusting the propeller rotational speed, causing the advance coefficient to fluctuate slightly around the design value. Based on the design condition of the PC456 metal propeller (J = 0.6,

n = 20 rps), while maintaining the same advance coefficient, two additional rotational speeds were selected (

n1 = 10 rps and

n2 = 30 rps) to analyze the cavitation performance of the three pre-deformed composite propellers. The open-water performance calculation results are presented in

Figure 11.

Given the structural complexity of composite propellers, the equivalent pitch method was adopted to analyze the relationship between the thrust coefficient and variations in rotational speed and ply angle. This method simplifies the propeller into a regular rectangular plane, equating the pitch at different radii to an equivalent pitch for this plane, thereby analyzing the relationship between the overall thrust and the equivalent pitch. As described in

Section 3.1, the thrust decrease at the 0° ply angle indicates a reduced equivalent pitch, hence a pre-deformation aiming to increase the pitch was applied; the converse logic applied to the 90° and 150° ply angles. When the rotational speed decreased to 10 rps, the thrust was reduced, and the pre-deformed composite propellers did not fully restore the geometry of the metal propeller. This resulted in the 0° ply propeller having a larger equivalent pitch than the metal propeller, while the 90° and 150° ply propellers had smaller equivalent pitches. Consequently, the 0° ply propeller exhibited the highest thrust coefficient, while the other two showed a decreasing trend [red polyline in

Figure 11a]. When the rotational speed increased to 30 rps, the propeller load increased. The equivalent pitch of the 0° ply propeller became lower than that of the metal propeller; however, extensive sheet cavitation had developed on the blade surfaces at this point, and the thrust coefficient variation no longer followed the equivalent pitch pattern. According to

Figure 11c, the target propeller (0° ply) achieved the highest propulsive efficiency at 10 rps and 20 rps and was second only to the 150° ply propeller at 30 rps. Overall, the target propeller demonstrated superior hydrodynamic performance across a relatively wide operational range, ranking it the best performer, followed by the 150° ply propeller, with the 90° ply propeller performing the worst.

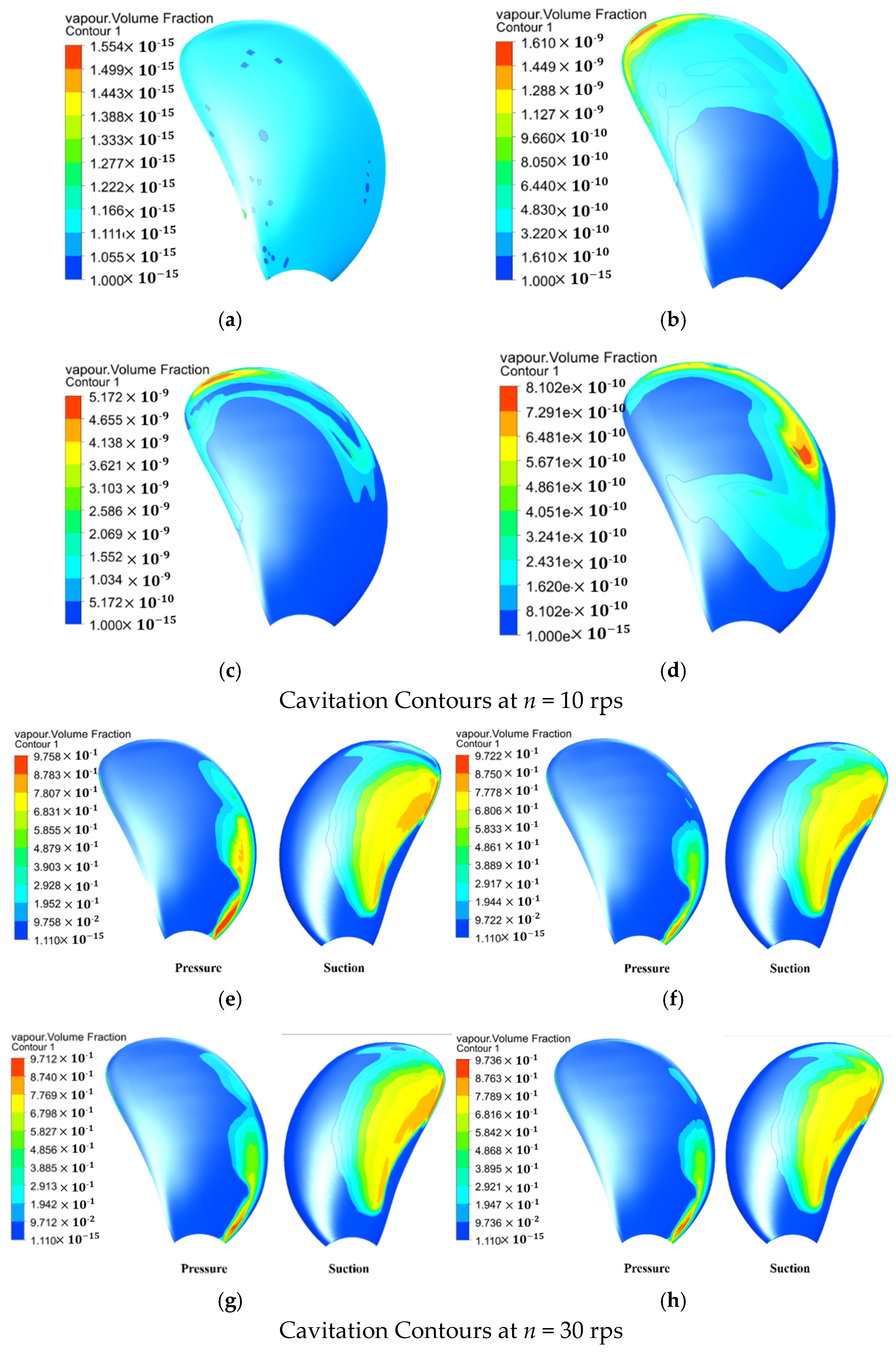

The anti-cavitation performance of the three pre-deformed composite propellers was further analyzed (

Figure 12). At 10 rps, no cavitation was observed on the metal propeller, whereas all three composite propellers showed cavitation tendencies: cavitation was concentrated at the blade tips for the 0° and 90° ply propellers and distributed from the mid-leading edge towards the tip for the 150° ply propeller. This indicates that under low-speed conditions, the anti-cavitation performance of the pre-deformed composite propellers slightly decreased because their geometric parameters did not fully revert to those of the metal propeller. However, the cavitation was not yet visible and had minimal impact on hydrodynamics. Among them, the 90° ply propeller exhibited the worst anti-cavitation performance, with a maximum vapor volume fraction of 5.172 × 10

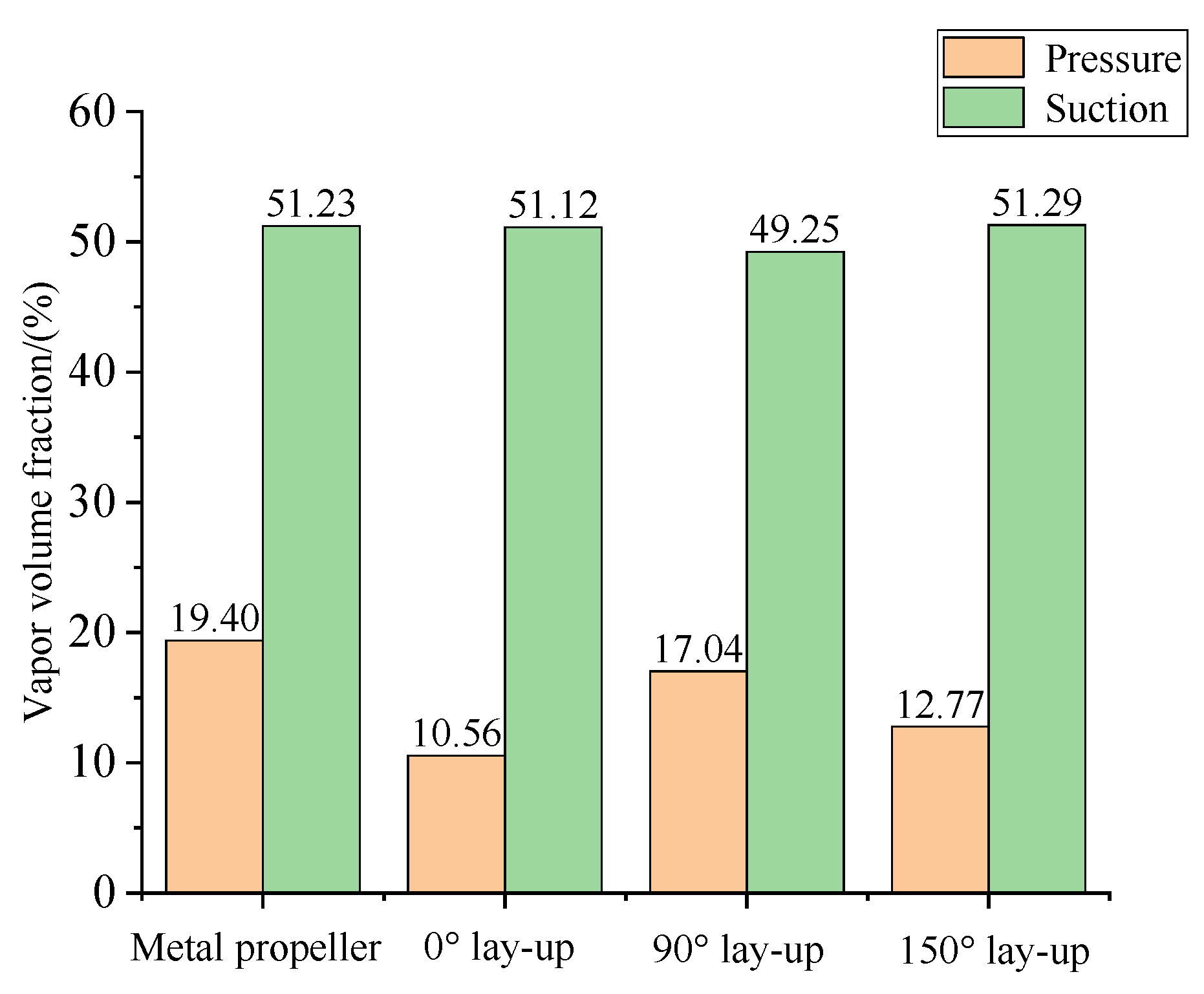

−9. When the rotational speed increased to 30 rps, extensive sheet cavitation appeared on the suction sides of both the metal and composite propellers. The cavitation extent decreased from the trailing edge towards the mid-region of the pressure side; cavitation on the pressure side was concentrated near the leading edge close to the blade root, with a smaller area compared to the suction side. The specific proportions are shown in

Figure 13. Comparing the cavitation areas reveals that the cavitation extent on the pressure sides of all three composite propellers was smaller than that of the metal propeller. The target propeller (0° ply) had the smallest cavitation area on the pressure side, only 10.56%. The cavitation area on the suction sides reached approximately 50% for all propellers, indicating severely degraded cavitation performance. Considering the cavitation area proportions on both the suction and pressure sides, the target propeller (0° ply) is concluded to have the best anti-cavitation performance, followed by the 150° ply propeller, with the 90° ply propeller being the worst.

In summary, under steady-state FSI conditions, the composite propeller with the 0° ply angle effectively utilizes its bend–twist coupling deformation characteristics to delay cavitation inception and reduce the cavitation area once cavitation occurs, thereby enhancing hydrodynamic performance. In contrast, the propellers with 90° and 150° ply angles exhibited lower hydrodynamic performance than the metal propeller at low speed (n = 10 rps). Although their performance improved at high speed (n = 30 rps), their overall cavitation-hydrodynamic performance remained inferior to that of the 0° ply composite propeller.

5. Transient FSI Cavitation Characteristics of the Composite Propeller Under Different Deformation Fields

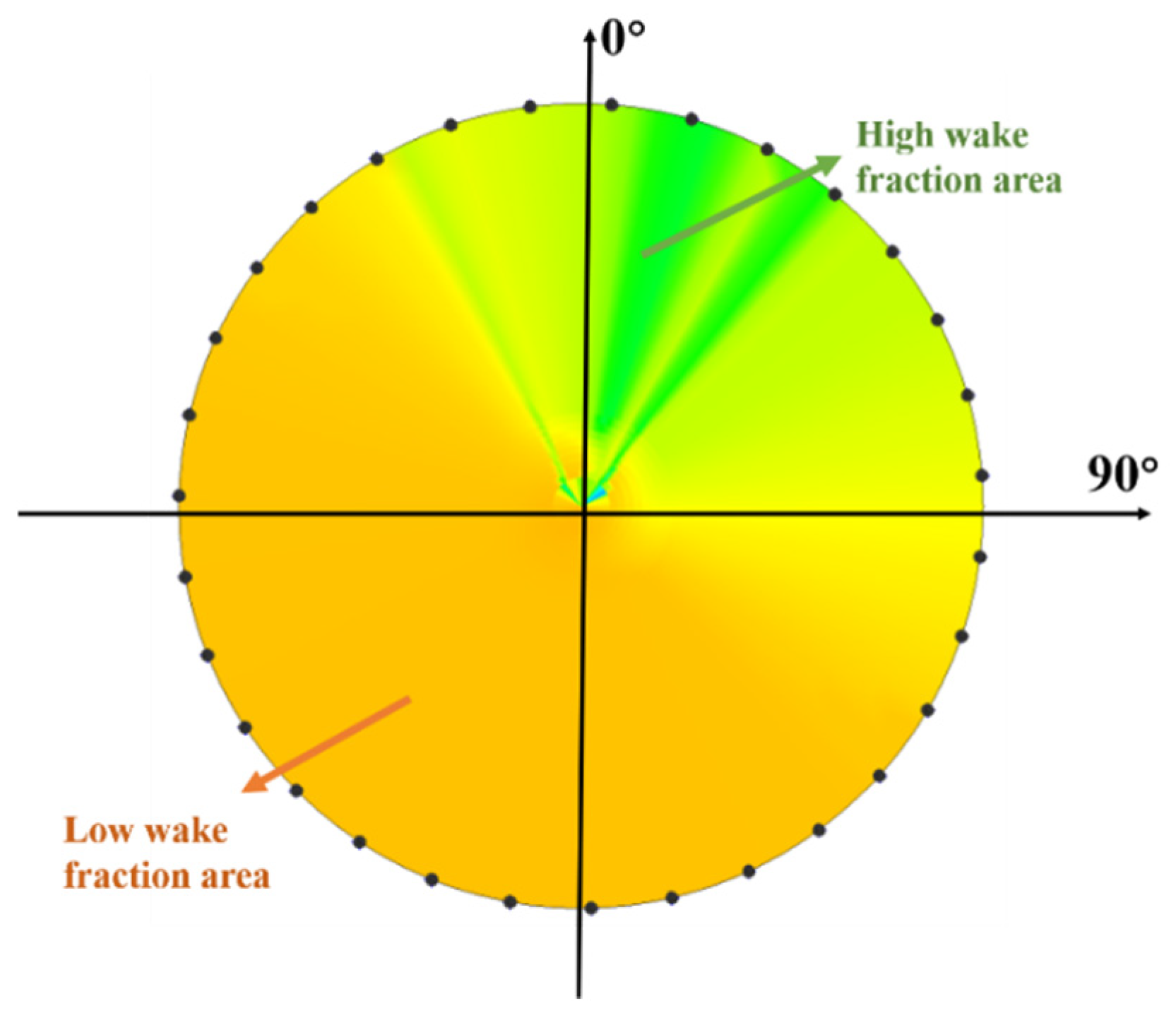

The ship wake field is characterized by low velocity and high wake fraction near the stern region, while the flow becomes more uniform with lower wake fraction below the propeller shaft depth, exhibiting distinct periodic distribution along the circumferential direction, as shown in

Figure 14. In this study, the wake field of a specific vessel served as the velocity boundary condition for transient FSI calculations, with an equivalent average velocity of 2.6 m/s. Maintaining an advance coefficient of J = 0.6, the corresponding rotational speed was 17.83 rps. Within this non-uniform wake field, the propeller’s hydrodynamic performance demonstrates periodic fluctuations, and the flow field inhomogeneity also affects cavitation performance at different phase angles.

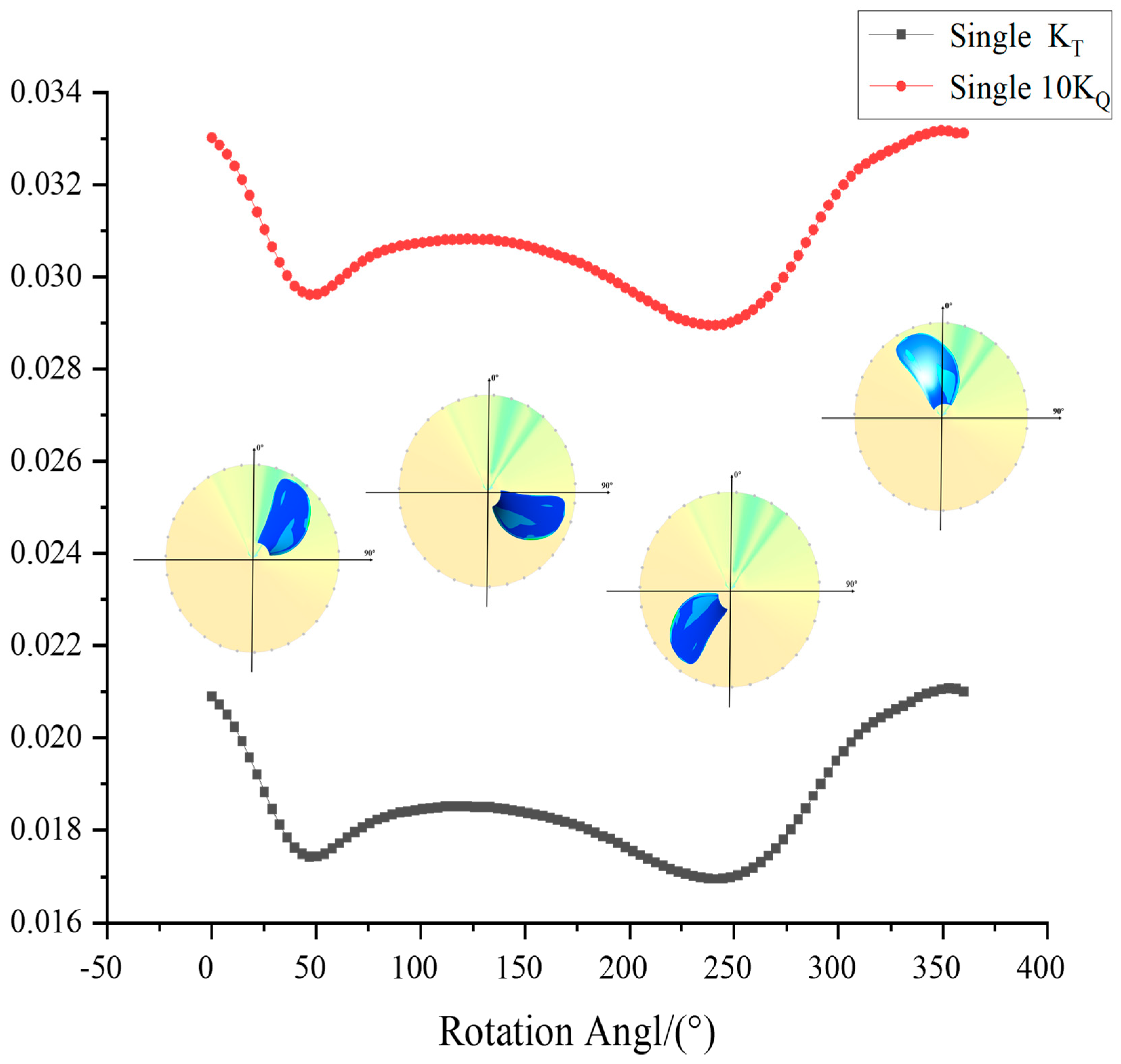

Under the influence of the wake field, both the blade thrust and torque coefficients exhibit significant periodic variations. Taking the metal propeller as an example, the single-blade thrust and torque coefficients reach their maximum values near 350° and their minimum values near 240°. As the blade leading and trailing edges alternately pass through high and low wake regions, secondary peaks in thrust coefficient appear near 120°, with secondary troughs near 40°, as shown in

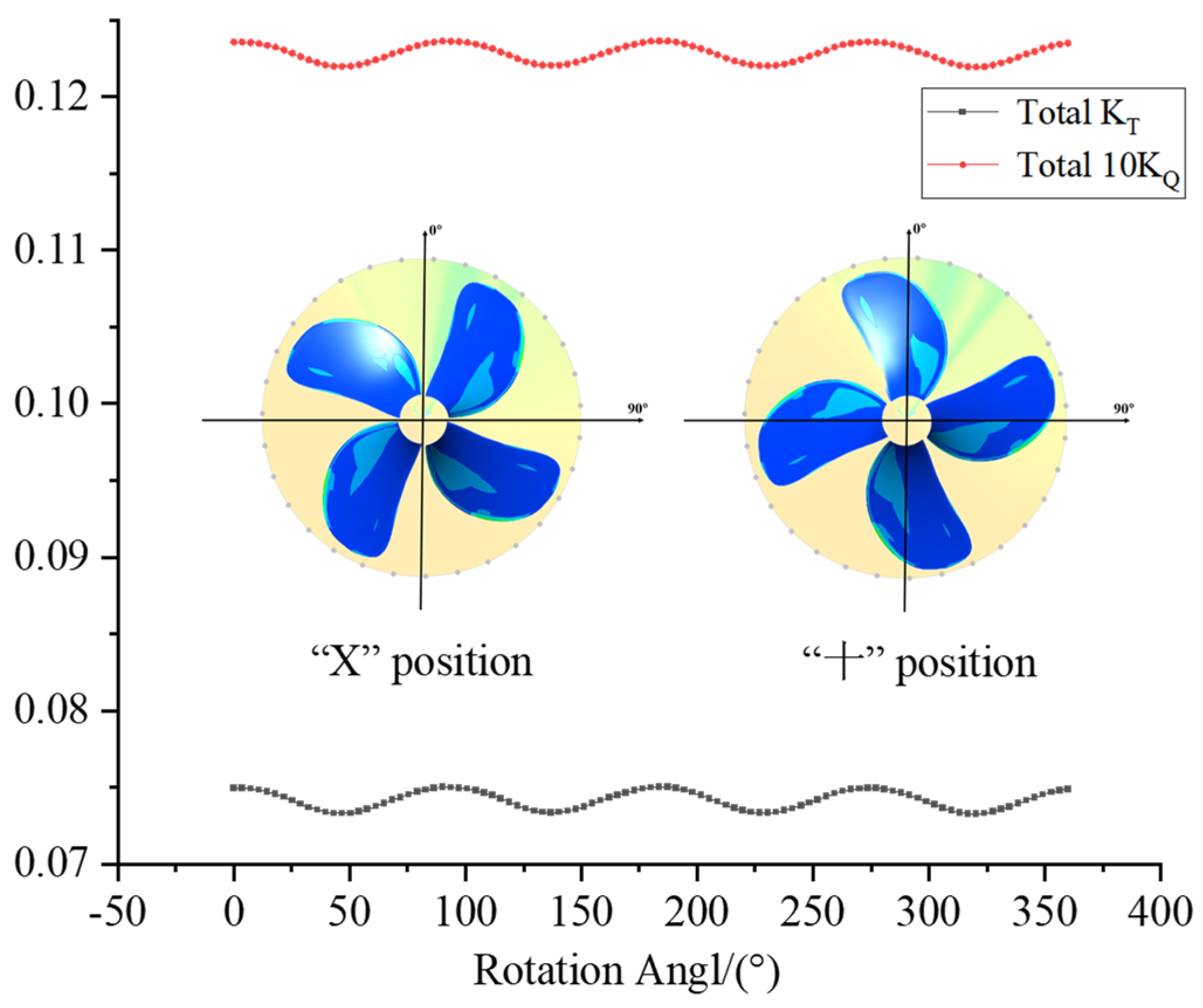

Figure 15. The positions of these peaks and troughs are closely related to the wake fraction distribution. For the entire propeller, the thrust and torque coefficients are maximum when the four blades form an “X” configuration and minimum when they form a “十” (cross) configuration. Since the four blades sequentially pass through high wake regions, the overall open-water performance exhibits four fluctuations per rotational cycle, as shown in

Figure 16.

The variation trends of thrust and torque coefficients for the three composite propellers are generally consistent with the metal propeller. However, due to FSI-induced deformation, differences exist in the fluctuation amplitudes of individual blades, with specific data provided in

Table 7. Overall, the 90° ply composite propeller demonstrates the most significant reduction in thrust fluctuations, reaching 15.7%, followed by the 0° ply at 11.8%, while the 150° ply shows the least effect at only 2.3%. The superior thrust fluctuation suppression of the 90° ply propeller compared to the 0° ply is attributed to its larger maximum coupled deformation of 0.8405 mm, which is 5.2 times that of the 0° ply (0.1621 mm), and its deformation field increases progressively along the blade midline from root to tip. Notably, the 0° ply configuration achieves 75% of the thrust fluctuation reduction effect of the 90° ply with only 19% of its deformation magnitude. This suggests that using more flexible materials to further increase the deformation of the 0° ply propeller could potentially suppress thrust fluctuations more efficiently. Furthermore, the 150° ply not only shows limited effectiveness in reducing thrust fluctuations but also exhibits increased torque fluctuations compared to the metal propeller. This indicates that when the deformation field pattern is opposite to that of the 0° ply, the hydrodynamic performance of composite propellers in non-uniform wake fields may further deteriorate.

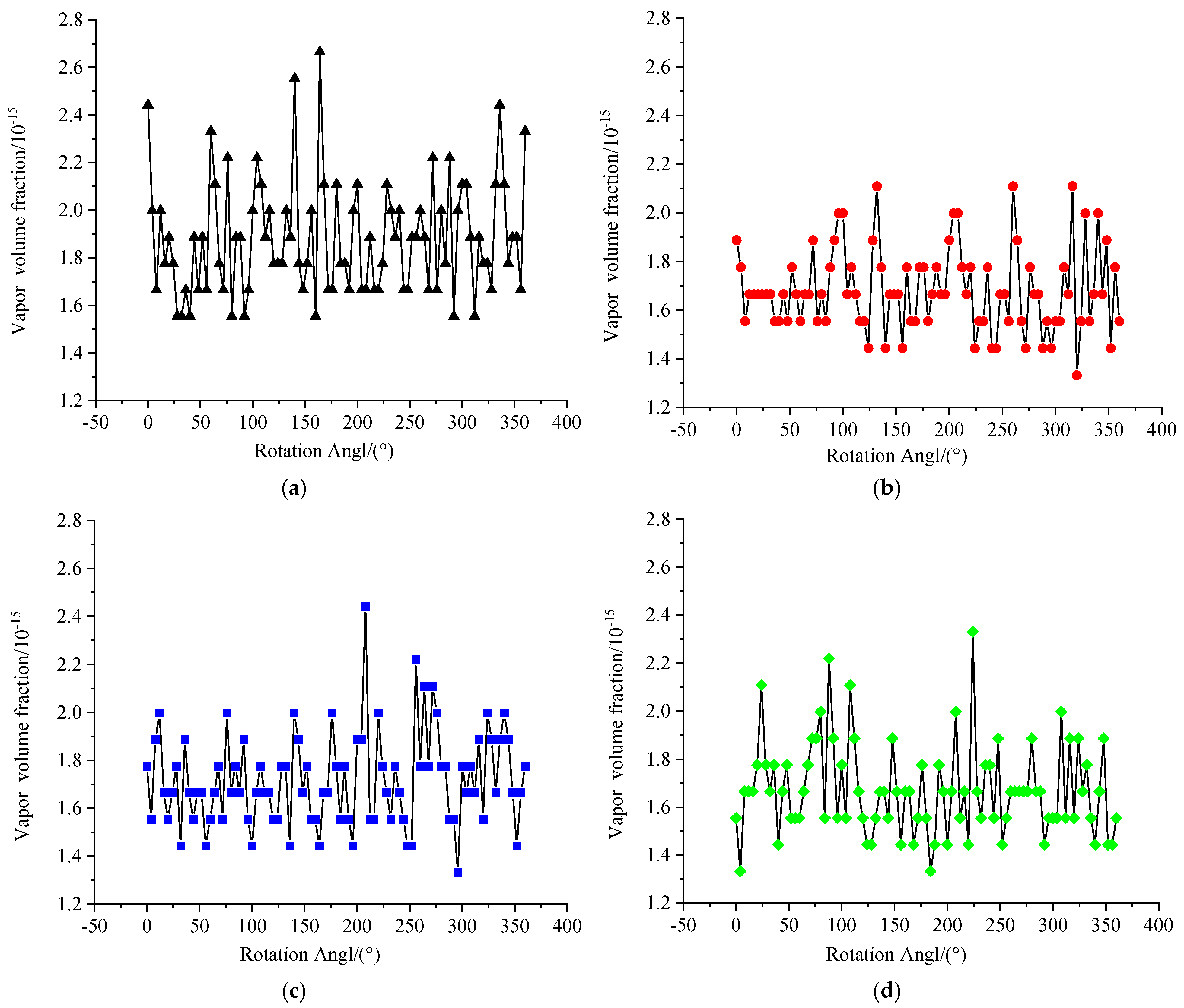

Although the vapor volume fractions for both the metal propeller and the three composite propellers remain on the order of 10

−15 under this wake condition, far below the visualization threshold, the fluctuation characteristics of the maximum vapor volume fraction at different phase angles can still be compared, as shown in

Figure 17. All three composite propellers exhibit lower maximum vapor volume fractions than the metal propeller. The 0° ply propeller shows the narrowest distribution bandwidth during cyclic rotation. Combined with its effective thrust fluctuation suppression, this indicates optimal cavitation fluctuation performance for this configuration, meaning pressure changes on the blade surface are more gradual when traversing high and low wake regions. Consequently, the 0°ply composite propeller possesses the best anti-cavitation capability in non-uniform flow fields.

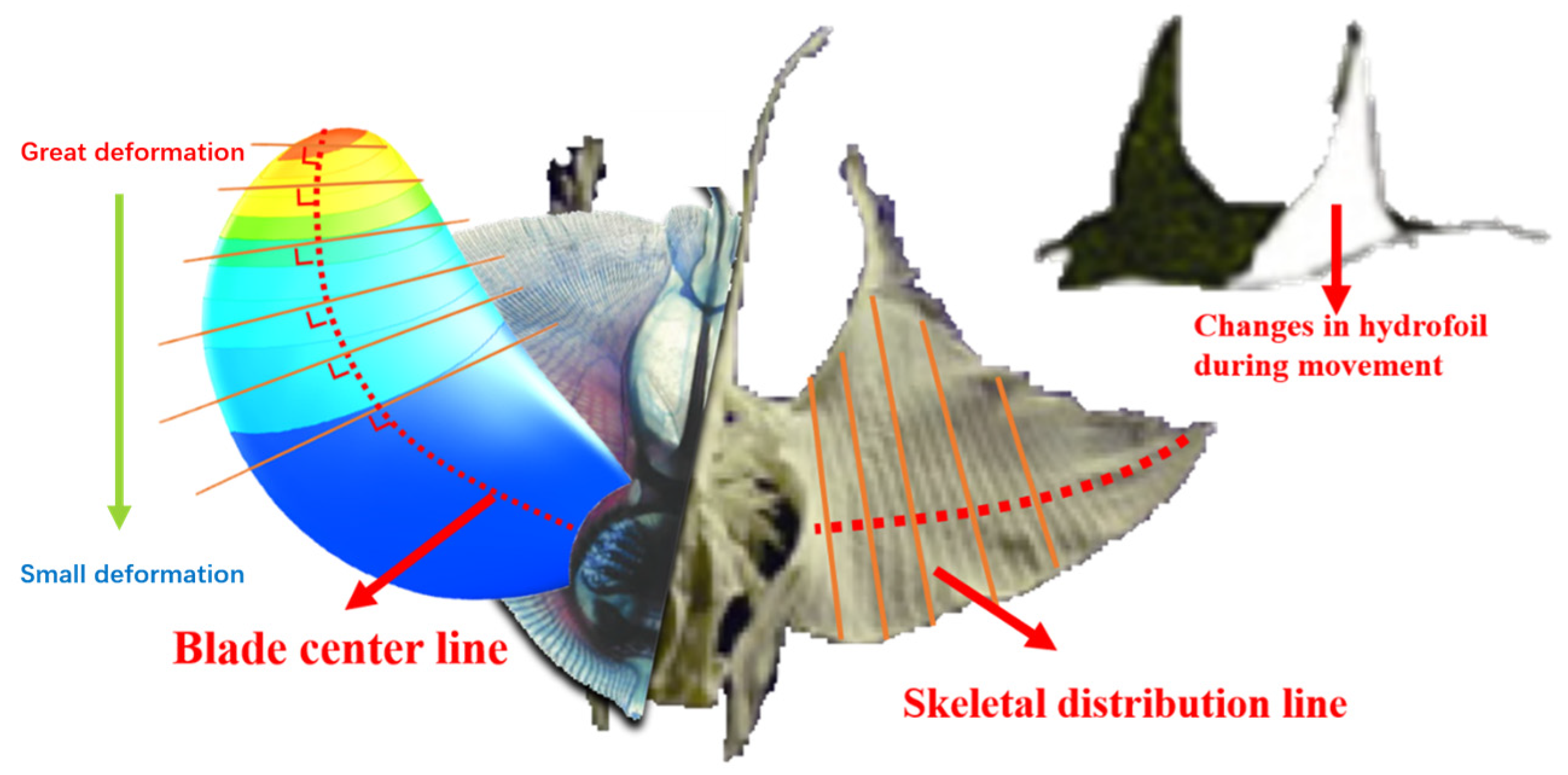

Integrating the thrust fluctuation suppression effectiveness and the maximum vapor volume fraction distribution characteristics, it is concluded that the unsteady cavitation hydrodynamic performance of composite propellers is optimal when the deformation field exhibits a gradient increase along the blade midline from the root to the tip (0° ply). This deformation pattern resembles the fin deformation characteristics of manta rays during swimming, which are known for highly efficient propulsion [

19], as shown in

Figure 18. Research by Tadashi Taketani et al. [

20] also indicates that such gradual deformation towards the blade tip helps reduce pressure fluctuations and improve propulsive efficiency. Conversely, for the PC456 propeller, when the deformation field gradually deviates from this ideal characteristic (90° ply), the cavitation hydrodynamic performance progressively declines. If the deformation field follows an opposite trend (150° ply), the operational performance may further deteriorate, counteracting the original purpose of employing composite materials.

6. Results and Discussion

This study established a CFD-FEM multiphase fluid–structure interaction (FSI) algorithm based on viscous flow theory to systematically investigate the hydrodynamics and cavitation characteristics of composite propellers with distinct pre-designed deformation fields. The primary novelty of this work lies in moving beyond a general analysis of FSI effects to demonstrate a deliberate, performance-driven design methodology. By correlating specific ply angles (0°, 90°, 150°) with resultant deformation patterns and their consequent impact on cavitation, we provide a quantitative framework for tailoring composite propeller deformation to achieve targeted anti-cavitation objectives—an approach distinct from conventional external flow optimization. The core findings and their implications are synthesized as follows.

The decisive role of the fiber ply angle in shaping the deformation field of a unidirectional composite propeller—and consequently its hydrodynamic signature—confirms that the deformation field must be treated as an active design variable, intentionally selected based on performance objectives rather than emerging as a passive outcome. To match or surpass the hydrodynamic performance of the original metal benchmark, a composite propeller derived from direct material substitution necessitates deliberate pre-deformation design. This requirement underscores the “operating condition uniqueness” and “model specificity” of such designs, indicating that optimal ply configurations are not universally applicable.

A key finding is the asymmetric sensitivity of performance coefficients: the propeller’s torque coefficient (KQ) responds far more significantly to changes in the effective pitch angle induced by deformation than the thrust coefficient (KT). This asymmetry is critical for predicting propulsion-system behavior and balancing torque demand with thrust output.

Regarding steady-state cavitation performance, under design conditions (J = 0.6, n = 20 rps), all pre-deformed composite propellers demonstrated superior anti-cavitation capability compared to the metal benchmark. The 0° ply configuration proved most effective, delaying inception and minimizing the cavity area. Performance at off-design speeds showed variation: while slightly inferior to the metal propeller at low speed (n = 10 rps) due to geometric deviation, the composite propellers outperformed in both open-water efficiency and cavitation resistance at high speed (n = 30 rps). The overall steady-state performance ranking was: 0° ply > 150° ply > 90° ply.

In a non-uniform wake field, the 0° ply propeller achieved 75% of the thrust fluctuation reduction observed in its 90° ply counterpart while undergoing only 19% of the latter’s maximum deformation. This suggests that a deformation field characterized by a gradient increasing from root to tip along the blade midline promotes more stable cavitation dynamics and superior unsteady performance. Deviations from this optimal deformation pattern can erode these advantages, potentially leading to performance inferior to the metal benchmark.

Limitations and Future Work: The conclusions are based on a numerical model incorporating several assumptions. Uncertainties arise from the selected turbulence and cavitation models, the simplified linear-elastic composite material properties, and the resolution of the interface dynamics. While a two-way FSI coupling was employed, the potential effects of cavitation-induced damping on structural response were not explicitly modeled. Future work should include experimental validation and investigate more complex layup schemes, different composite materials, and a wider range of dynamic loading conditions.

Scientific and Practical Implications: This research articulates a clear cause-and-effect relationship between ply angle, controlled deformation, and cavitation performance. It provides the marine propulsion community with a principled design strategy: leveraging tailored FSI deformation as an intrinsic mechanism for cavitation control. This approach offers a potential pathway for developing high-efficiency, low-noise propellers without relying on external appendages, thereby addressing key challenges in naval architecture concerning efficiency, acoustics, and cost.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C.; methodology, Z.C.; software, S.W.; validation, S.W.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, S.L.; resources, S.L.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H. and Z.C.; writing—review and editing, Z.C.; project administration, Z.H.; funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, grant number 2024AFB43” and the “National Defense Basic Scientific Research Product Innovation Project, grant number KY10100230067”.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ANSYS 11.0 for the purposes of data processing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Defined | Description | Unit |

| u | / | Velocity | m/s |

| t | / | Time | s |

| ρ | / | Density | Kg/m3 |

| p | / | Pressure | N/m2 |

| μ | / | Dynamic viscosity | Pa·s |

| s | / | Displacement | m |

| F | / | Force | N |

| D | / | Diameter | m |

| R | / | Radius | m |

| n | / | Rotational speed | rps |

| V | / | Flow velocity | m/s |

| σ | / | Cavitation number | / |

| ω | / | Angular velocity | rad/s |

| θ | / | Angle | ° |

| T | / | Thrust | N |

| Q | / | Torque | N·m |

| J | | Advance coefficient | / |

| KT | | Thrust coefficient | / |

| KQ | | Torque coefficient | / |

| η | | Propulsive efficiency | / |

References

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; He, W. Unsteady Cavitation and Noise Performance of a High Skewed Propeller behind the SUBOFF Boat. In ISOPE International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference; ISOPE: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023; ISSN 2095-3844, CN 42-1824/U. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y. Numerical and Experimental Research on Propeller-Induced Pressure Fluctuations and Cavitation in Non-Uniform Flow, 3rd ed. Ph.D. Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2002; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Determination of Propeller Cavitation Initial Inception and Numerical Analysis of the Inception Bucket. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 2012, 46, 410–416. [Google Scholar]

- Nhut, P.-T.; Hoang, V.T.; Young, J.Y. Evaluation of cavitation erosion of a propeller blade surface made of composite materials. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2015, 29, 1629–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, D.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, B.; Zhao, P. Numerical Study of the Propeller Cavitation and Pressure Fluctuation in Oblique Flow. Shipbuild. China 2023, 64, 240–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.C.; Sun, S.Y.; Wang, S.Q. Research on local back cavitation characteristics of two-dimensional hydrofoil based on a semi-analytical closed model. Chin. J. Ship Res. 2024, 19, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, H.-Y.; Hah, Z.-H.; Seol, H.-S. Performance Prediction of Composite Marine Propeller in Non-Cavitating and Cavitating Flow. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Q.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Z.-H. Effects of Composite Propeller Torsional Deformation on Thrust Pulsation. J. Propuls. Technol. 2022, 43, 210177. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, F. The Study of Laying Parameters’ Influences on the Performance of Carbon Fiber Marine Propeller. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, H. The impact of composite propeller’s material stacking sequence on the deformation law. Ship Sci. Technol. 2013, 35, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songwen, D.; Jinxiong, D.; Tiezhi, S. Dynamic response and acoustic characteristics of composite hydrofoil under cavitation-induced vibration. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 013302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B. Study on Cavitation and Cavitation Noise Performance of Composite Propeller Under Non-Uniform Flow Field. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.-D.; Dong, L.-L.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.-Y. Global cavitation and hydrodynamic characteristics of a composite propeller in non-uniform wake. J. Hydrodyn. 2023, 35, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F. Composite Propellers—Fluid-Structure Interaction. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, Z. Effect of Stacking Mode of Composite Laminates and Pre-deformed Design of Composite Marine Propellers. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 42, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Sun, H. Thicken and Pre-Deformed Design of Composite Marine Propellers. J. Propuls. Technol. 2017, 38, 2107–2114. [Google Scholar]

- Peiqing, L. Turbulent Model Theory; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2020; ISBN 978-7-03-065024-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, Z.; Liu, Y. Ship Theory; Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Huang, Q.; Qu, Y.L.; Pan, G. A Review of the Underwater Bionic Flapping Wing Robots. Digit. Ocean. Underw. Warf. 2023, 6, 380–405. [Google Scholar]

- Taketani, T.; Kimura, K.; Ando, S.; Yamamoto, K. Study on Performance of a Ship Propeller Using a Composite Material. In Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Marine Propulsors smp’13, Launceston, Tasmania, Australia, 5–8 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Mesh model of the fluid domain.

Figure 1.

Mesh model of the fluid domain.

Figure 2.

Y+ Distribution on the propeller blade surface.

Figure 2.

Y+ Distribution on the propeller blade surface.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of fiber ply angles for the composite propeller blade.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of fiber ply angles for the composite propeller blade.

Figure 4.

Computed vs. experimental open-water performance for the three mesh sets. (a) Thrust coefficient KT, (b) torque coefficient KQ, (c) efficiency η0.

Figure 4.

Computed vs. experimental open-water performance for the three mesh sets. (a) Thrust coefficient KT, (b) torque coefficient KQ, (c) efficiency η0.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of cavitation area ratio on the blade. (a) Experimental result for Case 1 (11.21%), (b) computed result for Case 1 (16.7%), (c) experimental result for Case 2 (5.03%), (d) computed result for Case 2 (3.7%).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of cavitation area ratio on the blade. (a) Experimental result for Case 1 (11.21%), (b) computed result for Case 1 (16.7%), (c) experimental result for Case 2 (5.03%), (d) computed result for Case 2 (3.7%).

Figure 6.

Deformation field contours of composite propellers with different ply angles. (a) θ = 0°, (b) θ = 30°, (c) θ = 60°, (d) θ = 90°, (e) θ = 120°, (f) θ = 150°.

Figure 6.

Deformation field contours of composite propellers with different ply angles. (a) θ = 0°, (b) θ = 30°, (c) θ = 60°, (d) θ = 90°, (e) θ = 120°, (f) θ = 150°.

Figure 7.

Coordinate points for a single blade geometry.

Figure 7.

Coordinate points for a single blade geometry.

Figure 8.

Comparison of deformation fields for the three composite propellers before and after pre-deformation (a) θ = 0° (before pre-deformation), (b) θ = 90° (before pre-deformation), (c) θ = 150° (before pre-deformation), (d) θ = 0° (after pre-deformation), (e) θ = 90° (after pre-deformation), (f) θ = 150° (after pre-deformation).

Figure 8.

Comparison of deformation fields for the three composite propellers before and after pre-deformation (a) θ = 0° (before pre-deformation), (b) θ = 90° (before pre-deformation), (c) θ = 150° (before pre-deformation), (d) θ = 0° (after pre-deformation), (e) θ = 90° (after pre-deformation), (f) θ = 150° (after pre-deformation).

Figure 9.

Scatter distribution of open-water performance. (a) Thrust coefficient scatter distribution, (b) torque coefficient scatter distribution.

Figure 9.

Scatter distribution of open-water performance. (a) Thrust coefficient scatter distribution, (b) torque coefficient scatter distribution.

Figure 10.

Cavitation patterns of the metal propeller and composite propellers with three deformation fields. (a) Metal propeller (pressure side), (b) 0° ply (pressure side), (c) 90° ply (suction side), (d) 150° ply (pressure side).

Figure 10.

Cavitation patterns of the metal propeller and composite propellers with three deformation fields. (a) Metal propeller (pressure side), (b) 0° ply (pressure side), (c) 90° ply (suction side), (d) 150° ply (pressure side).

Figure 11.

Performance parameters of metal and composite propellers at constant advance coefficient (J = 0.6) and different rotational speeds. (a) Thrust coefficient, (b) torque coefficient, (c) efficiency.

Figure 11.

Performance parameters of metal and composite propellers at constant advance coefficient (J = 0.6) and different rotational speeds. (a) Thrust coefficient, (b) torque coefficient, (c) efficiency.

Figure 12.

Cavitation contours of metal and composite propellers at different rotational speeds. (a) Metal propeller (pressure side), (b) 0° ply (pressure side), (c) 90° ply (pressure side), (d) 150° ply (pressure side); (e) metal propeller, (f) 0° ply, (g) 90° ply, (h) 150° ply.

Figure 12.

Cavitation contours of metal and composite propellers at different rotational speeds. (a) Metal propeller (pressure side), (b) 0° ply (pressure side), (c) 90° ply (pressure side), (d) 150° ply (pressure side); (e) metal propeller, (f) 0° ply, (g) 90° ply, (h) 150° ply.

Figure 13.

Cavitation area ratio of metal and composite propellers at 30 rps.

Figure 13.

Cavitation area ratio of metal and composite propellers at 30 rps.

Figure 14.

Schematic of the axially periodic non-uniform wake field.

Figure 14.

Schematic of the axially periodic non-uniform wake field.

Figure 15.

Time-domain fluctuation curves of thrust and torque coefficients for a single blade of the metal propeller.

Figure 15.

Time-domain fluctuation curves of thrust and torque coefficients for a single blade of the metal propeller.

Figure 16.

Time-domain fluctuation curves of overall thrust and torque coefficients for the metal propeller.

Figure 16.

Time-domain fluctuation curves of overall thrust and torque coefficients for the metal propeller.

Figure 17.

Maximum vapor volume fraction of metal and composite propellers at different phase angles. (a) Metal, (b) 0° ply, (c) 90° ply, (d) 150° ply.

Figure 17.

Maximum vapor volume fraction of metal and composite propellers at different phase angles. (a) Metal, (b) 0° ply, (c) 90° ply, (d) 150° ply.

Figure 18.

Schematic of manta ray motion.

Figure 18.

Schematic of manta ray motion.

Table 1.

Geometric parameters of the PC456 propeller.

Table 1.

Geometric parameters of the PC456 propeller.

| Diameter (m) | Pitch Ratio of 0.7R | Hub Diameter Ratio | Blade Number | Side Rake θs (°) |

|---|

| 0.250 | 0.6998 | 0.147 | 4 | 20 |

Table 2.

Effect of grid number on computational convergence.

Table 2.

Effect of grid number on computational convergence.

| Number | Rotation Domain

(Million) | Stability Domain

(Million) | Total Number of Grids (Million) | Calculation Result |

|---|

| 1 | 500 | 144 | 644 | Divergence |

| 2 | 345 | 104 | 449 | Divergence |

| 3 | 173 | 70 | 243 | Divergence |

| 4 | 163 | 46 | 209 | Divergence |

| 5 | 143 | 14 | 157 | Divergence |

| 6 | 123 | 33 | 154 | Convergence |

| 7 | 91 | 33 | 124 | Convergence |

| 8 | 71 | 14 | 85 | Convergence |

| 9 | 33 | 14 | 47 | Convergence |

Table 3.

Material parameters of T700 carbon fiber.

Table 3.

Material parameters of T700 carbon fiber.

| ρ/kg·m−3 | E1/GPa | E2, E3/GPa | G12, G13, G23/GPa | ν12, ν13 | ν23 |

|---|

| 1500 | 12.5 | 7 | 3.5 | 0.33 | 0.36 |

Table 4.

Open-water performance of composite propellers with different ply angles.

Table 4.

Open-water performance of composite propellers with different ply angles.

| Number | Angle θ (°) | Thrust Coefficient KT | Torque Coefficient 10KQ | Efficiency η0 | Maximum Deformation (mm) |

|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0.07382 | 0.12275 | 0.57426 | 0.192 |

| 2 | 30 | 0.07430 | 0.12355 | 0.57427 | 0.543 |

| 3 | 60 | 0.07642 | 0.12646 | 0.57710 | 0.865 |

| 4 | 90 | 0.07805 | 0.12860 | 0.57957 | 0.908 |

| 5 | 120 | 0.07924 | 0.13006 | 0.58179 | 0.693 |

| 6 | 150 | 0.07630 | 0.12595 | 0.57850 | 0.177 |

| 7 | Metal

propeller | 0.07455 | 0.12290 | 0.57920 | 0 |

Table 5.

Open-water performance of three pre-deformed composite propellers at design condition.

Table 5.

Open-water performance of three pre-deformed composite propellers at design condition.

| Fiber Ply Angle θ (°) | Thrust Coefficient KT | Torque Coefficient 10KQ | Thrust Coefficient Compared to the Deviation of a Metal Propeller | Torque Coefficient Compared to the Deviation of a Metal Propeller |

|---|

| 0 | 0.074624 | 0.12310 | 0.00103 | 0.001604 |

| 90 | 0.074629 | 0.12325 | 0.000944 | 0.002854 |

| 150 | 0.074413 | 0.12243 | −0.0018 | −0.0038 |

Metal

propeller | 0.07455 | 0.12290 | / | / |

Table 6.

Cavitation open-water performance of pre-deformed composite propellers under steady FSI.

Table 6.

Cavitation open-water performance of pre-deformed composite propellers under steady FSI.

| Fiber Ply Angle θ (°) | Thrust Coefficient KTσ | Torque Coefficient 10KQσ | Efficiency ησ | The Deviation Ratio of KTσ and KT | The Deviation Ratio of 10KQσ and 10KQ |

|---|

| 0 | 0.074829 | 0.0123658 | 0.577853 | 0.002744 | 0.004555 |

| 90 | 0.074745 | 0.0123727 | 0.576888 | 0.001715 | 0.003863 |

| 150 | 0.074553 | 0.0123310 | 0.577354 | 0.001892 | 0.003918 |

| Metal propeller | 0.074643 | 0.0123939 | 0.575110 | 0.001288 | 0.008457 |

Table 7.

Comparison of open-water performance between metal propeller and three composite propellers.

Table 7.

Comparison of open-water performance between metal propeller and three composite propellers.

| Fiber Ply Angle θ (°) | Single Blade

Thrust Coefficient △KTS | Single Blade

Torque Coefficient △10KQS | Propeller Thrust Coefficient Pulsation △KTT | Propeller Torque Coefficient Pulsation △10KQT |

|---|

| Large Pulsation Amplitude | Small Pulsation Amplitude | Large Pulsation Amplitude | Small Pulsation Amplitude |

|---|

| 0 | 0.004075 | 0.001052 | 0.004203 | 0.000116 | 0.001481 | 0.000145 |

| 90 | 0.003986 | 0.000971 | 0.000410 | 0.000104 | 0.001416 | 0.000138 |

| 150 | 0.004209 | 0.001094 | 0.000435 | 0.000121 | 0.001641 | 0.000165 |

| Metal propeller | 0.004122 | 0.001087 | 0.004223 | 0.001196 | 0.001679 | 0.00016 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |