1. Introduction

According to marine casualty and incident statistics reported by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) for the period 2014–2023 [

1], collisions account for 21.3% of ship-related occurrences, ranking as one of the most frequent casualty event types. Furthermore, 80.1% of maritime accidents are attributed to human factors. These figures highlight the need for a quantitative and reliable system capable of assessing collision risk and supporting navigational decision-making, particularly in situations where mariners fail to correctly perceive the encounter geometry or perform timely evasive actions.

The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs) [

2] require all vessels to employ all available means to determine whether a risk of collision exists. Accordingly, traditional collision-risk assessment has been primarily based on the distance at the closest point of approach (DCPA) [

3] and the time to the closest point of approach (TCPA) [

3], which are standard metrics employed in Automatic Radar Plotting Aids (ARPA) and other navigational support systems. Beyond these classical indicators, numerous studies have explored alternative approaches, including statistical analysis [

4], vessel-domain-based methods [

5,

6], weighted risk indices [

3], collision-risk perception studies [

7], fuzzy comprehensive evaluation [

8,

9], time-to-safety-distance analysis [

10], artificial neural networks (ANN)) [

11], Dempster–Shafer evidence theory (DST) [

12,

13,

14], sparse kernel machines [

15,

16], and deep learning-based models [

17].

The risk of vessel collisions arises from the complex interplay of multiple factors, and the relationships between these factors and the resulting risk have not been fully characterized. Consequently, evaluating collision risk under inherent uncertainty requires an approach that does not rely solely on predefined theoretical relationships among variables but instead learns patterns directly from observational data while accounting for the temporal and situational variability of the maritime environment. In this context, the present study adopts an interval type-2 fuzzy inference system (IT2FIS) [

18,

19,

20,

21] to provide a more reliable interpretation of uncertain risk signals generated during vessel encounters. By representing membership-function uncertainty through the Footprint of Uncertainty (FOU), the IT2FIS offers greater robustness than type-1 fuzzy models to noise, sensor errors, and ambiguity in human judgment, making it particularly suitable for collision-risk assessment in highly uncertain maritime environments.

Moreover, when a collision threat exists, vessels must be able to predict the risk sufficiently in advance to execute timely evasive maneuvers. Such prediction becomes more reliable when not only the current state but also past risk information is incorporated. However, uncertainties inevitably arise during observation and estimation in real-world maritime operations, necessitating a principled mechanism to handle them.

The DST [

22,

23] provides a representative evidence-theoretic framework well-suited for handling such uncertainty [

12,

24,

25], as it expresses independent pieces of evidence as basic probability assignments (BPAs) and combines them through Dempster’s rule [

22,

23]. This makes the framework particularly effective for sequential collision-risk estimation, where fusing historical and current uncertain information yields more stable and refined predictions than those obtained from single-time-point assessments. Nevertheless, classical Dempster’s rule has well-known limitations, producing counterintuitive or unstable results under high conflict [

26,

27,

28]. To address this issue, several alternative combination rules have been proposed, including the Robust Combination Rules (RCRs) [

29] as well as the Yager [

30] and Dubois–Prade [

31] rules. In this study, RCRs are adopted as the primary fusion mechanism to evaluate their applicability to maritime collision-risk fusion.

In terms of risk labeling, previous studies typically employed either Lenart’s time-based criterion [

10] or Fujii’s spatial vessel-domain model [

5] in isolation. This study integrates the two criteria to construct a three-level risk label—Safe, Moderate, and High—thereby capturing the gradual transitions in collision risk that binary labels fail to represent.

Building upon this foundation, we propose a new collision-risk assessment framework that integrates IT2FIS-based BPA generation with DS-based temporal fusion. The major contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

A multi-level risk labeling scheme that combines Lenart’s and Fujii’s criteria, overcoming the limitations of binary classification;

An IT2FIS–based collision-risk inference module that models structural uncertainties in AIS data and converts them into BPAs;

An DST-based temporal fusion mechanism incorporating RCRs, which mitigates the limitations of classical Dempster’s rule and is empirically validated against several evidence-combination strategies.

Unlike conventional Type-1 fuzzy systems, classical fuzzy–DST models, or hybrid approaches that rely on static fuzzy rules or single-time-point evidence fusion, this study introduces several methodological advances that have not been explored in maritime collision-risk assessment. First, an IT2FIS-based mechanism is proposed to generate time-indexed BPAs by directly mapping the FOU into belief structures, enabling explicit modeling of structural uncertainties in AIS-derived encounter variables. Second, a temporal evidence-fusion framework is developed to sequentially accumulate IT2-derived uncertain signals, whereas most existing fuzzy–DST approaches perform instantaneous, non-temporal fusion. Third, the applicability of RCRs to collision-risk fusion is systematically evaluated, which has not previously been examined in the maritime collision-risk context. Finally, a hybrid three-level risk-labeling scheme integrating Fujii’s spatial vessel domain and Lenart’s temporal criterion is introduced, allowing more realistic risk transitions than traditional binary labeling.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the proposed methodology.

Section 3 presents the AIS-based experimental results, including representative encounter case studies.

Section 4 provides a detailed discussion, and

Section 5 concludes the paper with directions for future research.

2. Methodology

Vessel navigation is influenced by various factors such as weather conditions, traffic density, tidal currents, and maneuvering performance, while AIS measurements inevitably contain noise and sensor errors. Therefore, a collision-risk assessment framework must explicitly account for these sources of uncertainty. In this study, we propose a collision-risk evaluation methodology that integrates the IT2FIS with DST. The theoretical background of type-2 fuzzy sets and evidence-theoretic information combination, including RCRs, is summarized in

Appendix A and

Appendix B, respectively. The AIS data collected from the study area undergo filtering, grouping, normalization, and temporal interpolation to ensure geometric and temporal consistency. The processed data are then fed into the IT2FIS, which models input uncertainty through the FOU and produces time-indexed BPAs for collision risk.

Risk inference incorporates both Lenart’s time-based criterion and Fujii’s spatial vessel-domain concept to reflect the combined temporal and geometric characteristics of vessel encounters. The resulting BPAs constitute a sequential, trajectory-based dataset, in which the BPA at each time step is fused with the accumulated evidence from previous steps using DST combination rules to generate the final fused BPA and its associated uncertainty.

2.1. Preprocessing AIS Data

A comprehensive preprocessing procedure was applied to the collected AIS data to ensure reliability, temporal continuity, and coordinate consistency. The raw AIS messages contained both static and dynamic vessel information; in this study, the key dynamic variables extracted included the maritime mobile service identity (MMSI), timestamp, latitude, longitude, course over ground (COG), speed over ground (SOG), and heading. All records were grouped by MMSI to construct individual vessel trajectories. To ensure data quality, missing values and duplicated records (based on MMSI–timestamp pairs) were removed, and abnormal entries were filtered out. Furthermore, only vessels belonging to the target vessel categories, as identified through vessel-type metadata, were retained for analysis. Because AIS-reported positions typically reference the antenna location rather than the geometric center of the vessel, positional corrections were performed using each vessel’s length overall (LOA), beam, and antenna-offset information. This correction step is important for improving the geometric consistency of position measurements when applying Fujii’s safety domain and Lenart’s time-to-safety-distance criteria, both of which are defined with respect to the vessel’s centroid.

To achieve uniform temporal resolution, each trajectory was resampled on an equally spaced 1-min time grid, and linear interpolation was applied to latitude, longitude, course, speed, and heading. The interpolated trajectory dataset is defined as:

where

denotes the

-th trajectory and

is the time index within the trajectory. Here,

and

represent the centroid-corrected latitude and longitude at time

;

,

, and

correspond to the course over ground, speed over ground, and heading angle, respectively. Thus,

constitutes a time-ordered geometric trajectory of the vessel.

2.2. Computation of Collision Risk Indicators

To quantitatively describe the dynamic encounter between two vessels, four fundamental collision risk indicators were derived: DCPA, TCPA, instantaneous distance, and relative bearing.

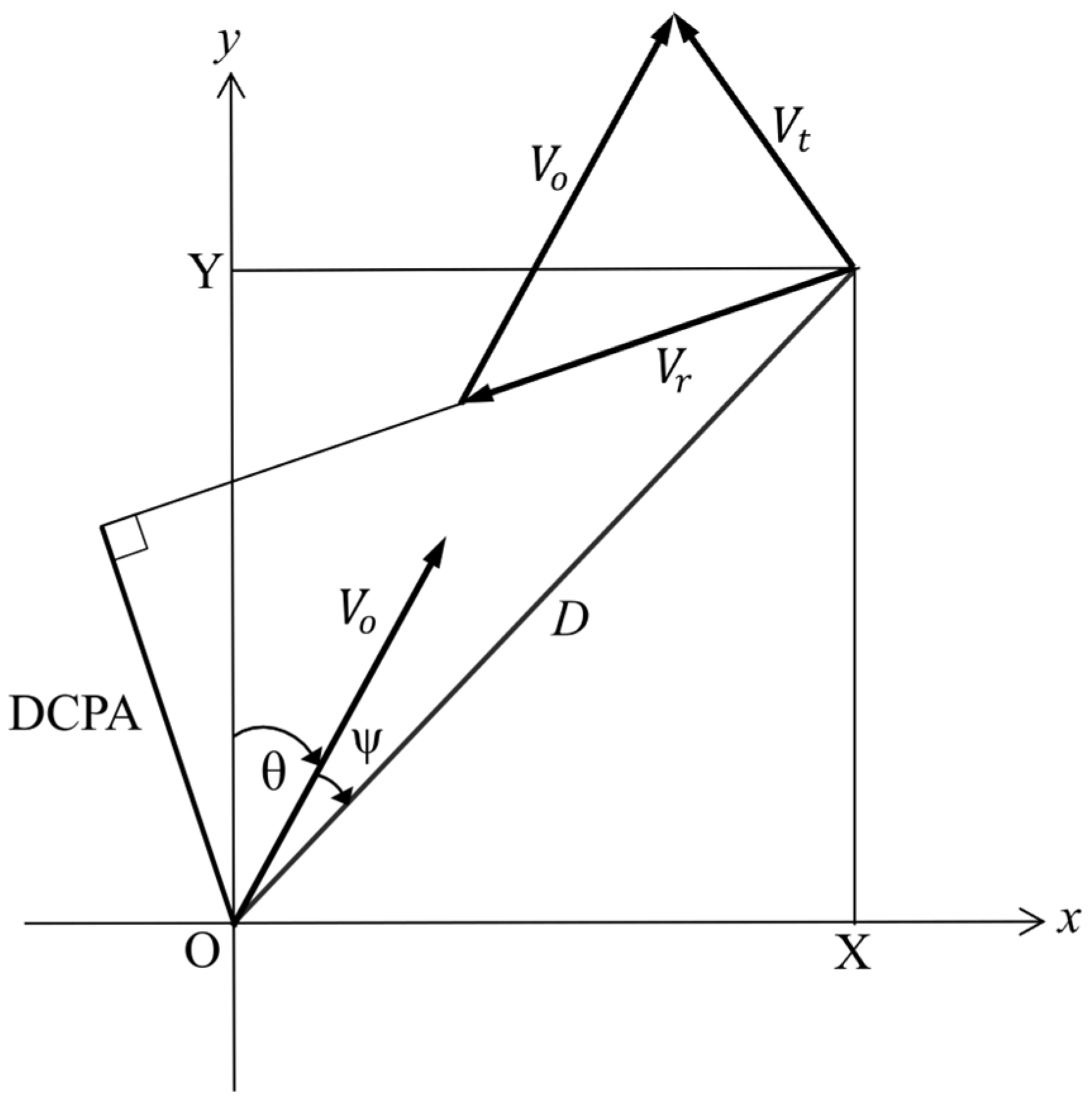

Figure 1 illustrates the geometric configuration of a two-vessel encounter in a Cartesian coordinate system (

,

). In this coordinate frame, the own vessel is located at the origin

, moving with velocity

and course angle

, while the target vessel is located at position (

,

) with velocity

. The relative velocity vector is denoted as

, the instantaneous distance between the two vessels is

, and the relative bearing is represented by

. The relative bearing expresses the encounter geometry between the own vessel and the target vessel and is computed from the difference in their position and heading vectors.

Let [

,

] be the

and

components of the relative velocity

. Then, the geometric collision parameters are defined as follows [

3,

10]:

where

denotes the magnitude of the relative velocity between the two vessels. The relative bearing

of the target vessel with respect to the own vessel is calculated as:

where

is the angle between the relative position vector and the

x-axis. To maintain continuity within the range

–

,

is wrapped to

as

. In the subsequent fuzzy inference process, the

is decomposed into two orthogonal trigonometric components to avoid angular discontinuity:

which represent the lateral and longitudinal aspects of the encounter geometry, respectively.

These five indicators—DCPA, TCPA, , , and —form the primary input variables of the IT2FIS for instantaneous collision-risk evaluation, enabling the integration of both spatial and temporal risk characteristics.

2.3. Multi-Level Collision Risk

Collision risk between vessels must account for both temporal proximity and spatial proximity. Accordingly, this study defines a multi-level risk framework by integrating two complementary criteria.

2.3.1. Time-Based Risk

The time-based criterion [

10] proposed by Lenart evaluates collision risk using the time required for two vessels to reach a predefined safety distance

. Given the relative speed

, DCPA, and TCPA, the times at which the inter-vessel distance equals

are expressed as:

where

denotes the time required for the distance between vessels to change from

to DCPA. Based on these quantities, the time-based risk level is defined as:

where

is the critical time-to-safety threshold, set to 10 min [

10] in this study. The values of

were assigned according to the relative-bearing-dependent domain of Goodwin’s vessel domain model [

32]. This

-based logic provides a more conservative assessment than relying on TCPA alone and structurally prevents the omission of situations in which

.

2.3.2. Spatial Risk

Spatial risk is evaluated using the elliptical safety domain [

4] proposed by Fujii. For a vessel

with length

, the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the safety ellipse are defined as

(longitudinal) and

(lateral). The radial extent in direction

(bearing of the target vessel in the own vessel’s heading frame) is:

A spatial collision threat occurs when the inter-vessel distance

is less than or equal to the sum of the directional ellipse radii:

2.3.3. Final Multi-Level Risk

The final collision-risk level integrates both the time-based and spatial-domain assessments:

Thus, a high-risk level (2) is assigned when both a temporal approach threat and a spatial domain overlap occur simultaneously, reflecting the operational understanding that imminent collision risk arises from the concurrence of time-critical and proximity-based conditions. This multi-level risk formulation serves as the ground truth for training the IT2FIS model and for subsequent DST-based temporal combination, allowing the framework to capture both the temporal continuity of collision risk and the uncertainty inherent in spatial proximity.

2.4. Construction of Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Inference System

In this study, an IT2FIS was constructed to jointly evaluate temporal and spatial collision-risk factors. The system takes as input several kinematic indicators of vessel-to-vessel encounters (e.g., DCPA, TCPA, , ) and produces a BPA at each time step that represents the degree of belief over multiple risk classes. To explicitly account for uncertainty, interval type-2 fuzzy sets with upper and lower membership functions are employed, thereby generating mass functions that are directly compatible with DST.

2.4.1. Rule Base Structure Generation

The antecedent structure of the IT2FIS was initialized automatically by applying subtractive clustering [

33] to the training data. In this approach, every data point is treated as a potential cluster center, and the local data density within a predefined cluster influence range (CIR) is computed to evaluate the suitability of each point as a center.

Data points located in high-density regions are selected as cluster centers, and nearby points are suppressed using an exponential decay function. Consequently, smaller CIR values tend to yield a larger number of fine-grained rules, whereas larger CIR values produce fewer, more generalized rules. Each selected cluster center is used as the center of a Gaussian membership function in the antecedent part of a fuzzy rule. The membership function width

for each input variable

is determined by scaling the local standard deviation around the cluster center,

, with a global factor

, as follows:

where

denotes the rule (cluster) index and

denotes the input-variable index. Through this procedure, the number and location of rules are determined in a data-driven manner without pre-specifying the rule count, allowing the IT2FIS structure to adapt to the underlying data distribution.

2.4.2. Design of Interval Type-2 Membership Functions

For each input variable

and rule

, an interval type-2 Gaussian membership function with an upper membership function (UMF) and a lower membership function (LMF) is defined as:

where

is the cluster center,

is the width determined in the previous step,

controls the relative height of the LMF, and

adjusts the horizontal lag between UMF and LMF. This construction models the epistemic uncertainty of the membership functions, ensures that

holds for all

, and thus guarantees valid IT2 semantics.

2.4.3. Voting-Based Consequent Assignment

The consequent class of each rule is automatically determined using the labeled training data. The procedure is based on the data-driven consequent assignment method in [

34]. First, the degree to which each training sample

belongs to rule

is computed as:

Each sample is then weighted according to its true class label

. For a given class

, the weighted vote accumulated by rule

is defined as:

A higher weight

is assigned when

(the high-risk level) to emphasize the importance of correctly capturing dangerous situations. Each rule thus obtains a voting strength for all classes, and the consequent class

is determined as follows:

This mechanism allows each rule to automatically specialize in the class region it most strongly represents, without requiring manual labeling of rules, while reflecting both the data distribution and rule activation patterns.

To improve learning efficiency and interpretability, a rule pruning procedure based on rule importance was applied to the rules generated by subtractive clustering. The importance score of rule

is defined as the total vote across all classes:

Rules with high importance scores represent major data patterns, whereas rules with low scores are more likely to correspond to noise or redundant information. In this study, only the top rules with the highest importance scores were retained, resulting in a compact and interpretable IT2FIS rule base.

2.4.4. Inference and BPA Computation

The trained IT2FIS produces, at each time step, a BPA that encodes belief, plausibility, and ignorance over the collision-risk classes. This process integrates fuzzy inference with DST mass computation in a unified manner.

For each input, membership degrees with respect to the UMF and LMF are computed, yielding and . Consequently, each rule has an interval firing strength, with upper and lower bounds and , respectively. The interval represents the uncertainty in the rule activation due to input uncertainty.

The IT2FIS adopted in this study is a Sugeno-type structure [

35], where each rule’s consequent is defined as a constant output centroid

. The rule outputs are aggregated using their interval firing strengths, and the overall system output is obtained as a single interval type-2 fuzzy set, represented by a lower and upper bound

. This interval is numerically estimated using the Karnik–Mendel (KM) type-reduction algorithm [

36]:

where

is the total number of rules. The resulting interval

describes the uncertainty in the defuzzified output of the type-2 system and is used as the support interval for DST mass assignment.

For each risk class

, the basic probability mass

is computed as the average overlap between the output interval and a triangular membership function centered at class

:

where

represents the half-width of the triangular membership function that governs the overlap between adjacent classes. The resulting

represents the mean degree of belief that the IT2FIS output belongs to class

.

If the sum of the class masses is less than 1, the remaining mass is assigned to the frame of discernment

as ignorance:

with all masses normalized to satisfy

Through this procedure, each time-step output of the IT2FIS is converted into a BPA vector that is fully compatible with DST, and is subsequently used in the temporal combination stage.

2.5. Hyperparameter Optimization

Because the performance of the IT2FIS strongly depends on its antecedent structure and membership-function shapes, an automated hyperparameter tuning procedure based on Bayesian optimization (BO) was adopted. Five key hyperparameters were optimized: the cluster influence range (

), the membership-function width scaling factor (

), the lower membership-function scaling factor (

), the lower lag (

), and the window half-width (

) that controls class overlap in the BPA integration stage. The search ranges for these variables are summarized in

Table 1.

Optimization was performed using 5-fold cross-validation. For each candidate hyperparameter configuration (treated as continuous variables), an IT2FIS model was trained and evaluated on a validation subset, and the following objective function

to be minimized is defined as:

where

is the average F1-score across classes,

is the mean ignorance, and

is the false negative rate for the critical (high-risk) class. Thus, hyperparameter sets that simultaneously achieve high F1, low ignorance, and low critical false negatives are preferred.

Bayesian optimization employed a Gaussian process surrogate with an Expected Improvement (EI) acquisition function [

37] and was allowed up to 100 objective evaluations. The optimal hyperparameters for each fold were stored together with the corresponding validation metrics (

,

,

), and the results were analyzed across folds. This procedure enabled the IT2FIS to adapt its structure to the data characteristics while mitigating overfitting and yielding a reliability-oriented collision-risk inference model.

2.6. Temporal Evidence Fusion Framework

While the IT2FIS produces a BPA at each time step independently, real-world vessel collision risk exhibits strong temporal continuity. Therefore, this study employs a temporal evidence fusion framework in which the cumulative evidence from previous time steps is combined with the current observation using Dempster’s rules, resulting in a time-consistent estimate of collision risk.

2.6.1. Temporal Decay

For each time step

, the reliability of past evidence is assumed to decay over time. The accumulated mass function

from the previous time step is adjusted using the following decay operation [

23,

29]:

where

is the decay coefficient controlling the memory retention of past evidence. A dynamic, half-life-based decay scheme is applied as follows:

where

is the time interval between consecutive steps and

denotes the time required for the reliability to decay to half its value. Here,

corresponds to perfect memory, whereas

indicates partial forgetting.

The decayed mass is then fused with the current mass using a selected combination rule. In this study, five combination rules on the single-frame hypothesis were compared: Dempster (normalized product), Yager (conflict to ignorance), RCR-S (robust combination rule with symmetric redistribution), and RCR-L (robust combination rule with logarithmic weighting).

2.6.2. Pignistic Transformation and Decision Making

Given the fused BPA at time

, the Pignistic Probability (

) [

38] for each class

is computed by redistributing the mass assigned to the frame

uniformly over the singleton hypotheses:

Here, denotes the number of elements in the frame of discernment and ensures that ignorance mass is evenly allocated to all classes. The final predicted class at time is then determined as: .

The performance of each fusion model is evaluated using the same metrics (, , ) as those employed in IT2FIS training, thereby ensuring consistency between the optimization and evaluation procedures.

2.6.3. Optimization of Temporal Fusion Parameters

Because collision-risk estimation involves temporal continuity, the selection of the decay coefficient

and the logarithmic weighting parameter

in the RCR-L rule directly affects uncertainty propagation and the stability of temporal estimates. To minimize undesirable uncertainty propagation and to maximize fusion stability, these temporal fusion parameters were optimized via grid search within predefined discrete ranges (

Table 2), using the same objective function as in

Section 2.5.

The parameter, which controls as per the above equation, plays a critical role: overly large values (i.e., ) cause excessive retention of outdated evidence, increasing the risk of misjudgment, whereas overly small values lead to rapid forgetting and overemphasis on recent observations, potentially resulting in unstable estimates. The logarithmic weighting parameter in the RCR-L rule governs the strength of conflict redistribution: smaller values make the rule closer to a conservative conjunctive combination, while larger values lead to more optimistic, disjunctive-like behavior.

2.7. Model Evaluation Metrics

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate both the predictive reliability and safety-critical conservatism of the multi-level (safe = 0, moderate = 1, high = 2) collision-risk classifier based on time-series AIS data. To this end, three key metrics were computed on the test sets of each cross-validation fold:

,

, and

. For consistency with the optimization objectives described in

Section 2.5, the same indicators were employed to quantitatively assess model performance and to ensure coherence between the optimization and evaluation procedures. For each class

, the

is defined as:

Here, denotes the number of samples correctly classified as class , the number of samples incorrectly predicted as class , and the number of true class- samples misclassified as other classes. reduces the impact of class imbalance and is particularly useful for assessing the model’s ability to discriminate between the moderate (1) and high (2) risk classes.

In safety-critical applications, missing an actual high-risk situation can directly lead to severe accidents. The

is defined as the proportion of samples in the critical risk set

that are misclassified as non-critical:

where

is the indicator function,

is the true class,

is the predicted class, and

indexes time. A lower

indicates that the model more reliably detects critical risk situations.

In DST, ignorance is represented by the mass assigned to the frame

. The

metric quantifies the average model uncertainty over time:

Smaller values indicate more confident and reliable inferences. Together, , , and provide a comprehensive evaluation of both predictive accuracy and uncertainty management for the proposed collision-risk assessment framework.

3. Experiments

3.1. Data Collection

The study area was defined as the coastal waters adjacent to the approaches of Busan and Ulsan Ports in the southeastern region of Korea. This region represents one of the busiest port-approach waterways in the country, where inbound and outbound traffic frequently intersects with vessels transiting along the coast. Owing to the high traffic density and the frequent formation of complex encounter geometries, the area is well suited for collision-risk analysis. The spatial extent of the study area is illustrated in

Figure 2.

To observe vessel encounter patterns within this area, automatic identification system (AIS) data were utilized. AIS messages were collected over an 18-day period from 1 April to 18 April 2014 (KST). The dataset was obtained from a graduate research laboratory during the author’s doctoral studies. For reliable evaluation, the dataset was restricted to vessels classified as cargo ships, tankers, dangerous-goods carriers, and passenger ships. To assess the reliability of the AIS data used in this study, a quantitative data quality analysis was conducted on the preprocessed dataset, which consisted of 1,527,662 AIS records. The median reporting interval was 30 s (mean 113.9 s), and 95.3% of consecutive updates occurred within 3 min. Large jumps exceeding 5 kt occurred in only 0.004% of consecutive reports, while large inter-report variations greater than 45° were observed in 0.15% of cases. The median inter-report position displacement was approximately 170 m and was used as an indirect indicator of GPS position noise; the mean difference between reported and trajectory-derived speed was 0.75 kt. For sailing vessels ( > 3 kt), the mean – difference was 3.69°, reflecting high directional consistency. Overall, these results indicate a moderate noise level consistent with operational AIS data.

All extracted trajectories (6556) were resampled at 1-min intervals, and encounter-related indicators—including inter-vessel distance, DCPA, TCPA, and relative bearing—were computed for vessel pairs observed at the same timestamps. Based on these features, encounter cases were formed for each own–target vessel pair. Finally, 1458 encounter cases (comprising 35,119 time-indexed samples) were selected for analysis by retaining only those with a minimum duration of 10 min and in which the risk label (Lenart-based criterion) indicated a hazardous state for at least 30% of the trajectory.

3.2. Model Development

To develop the IT2FIS-based collision risk assessment model, a trajectory-level stratified five-fold cross-validation was conducted. Each trajectory was assigned exclusively to a single fold to prevent temporal leakage, and the top 12% of long-duration trajectories were evenly distributed across folds to maintain balance. In each fold, 80% of the trajectories were used for training and the remaining 20% for testing, while the model hyperparameters were independently optimized through Bayesian optimization. The final performance was computed by aggregating predictions such that every trajectory was evaluated exactly once by a model that had not been trained on it.

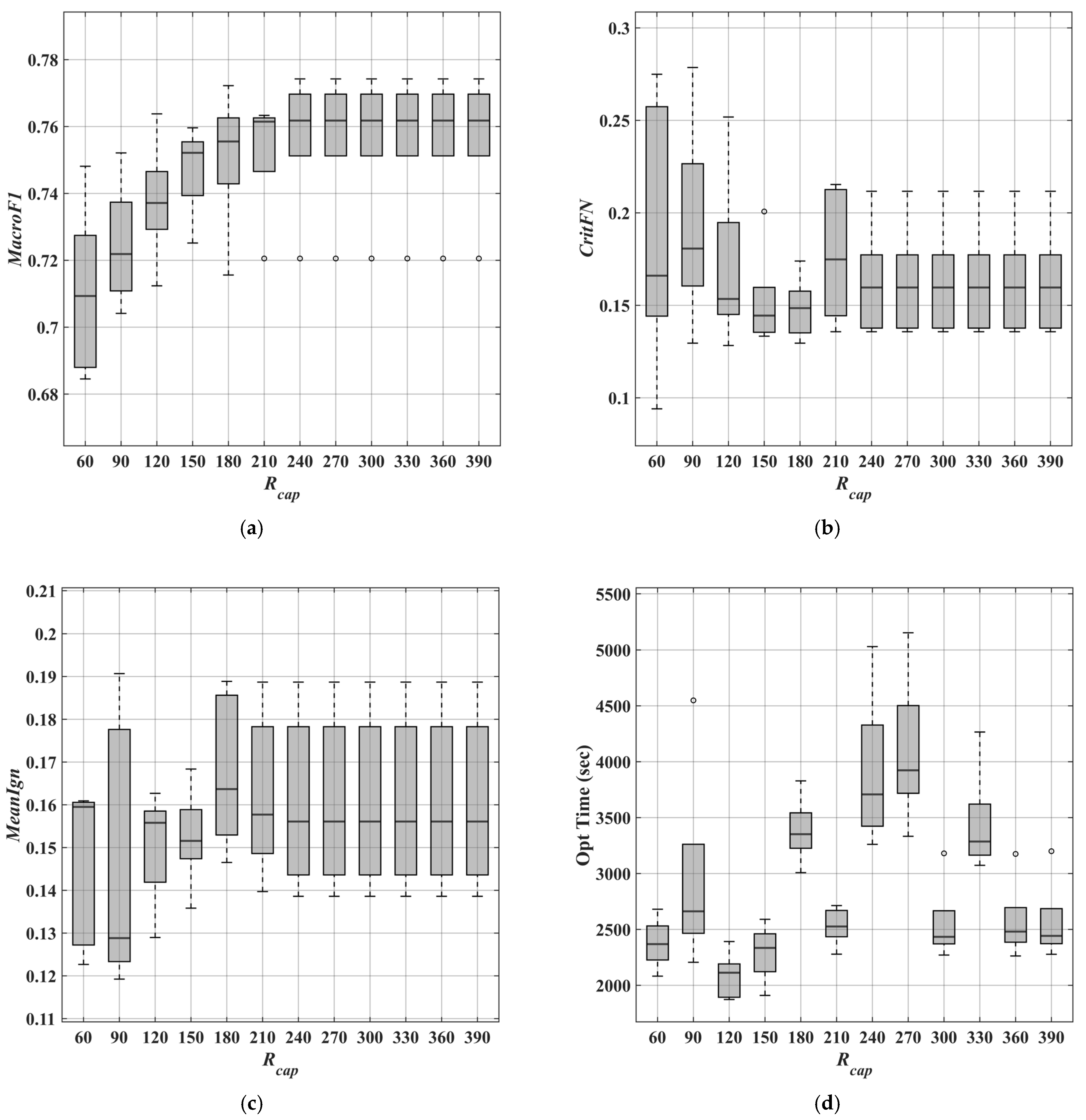

Performance variations with respect to the parameter

were analyzed using the boxplots in

Figure 3 and the summary statistics in

Table 3. As shown in

Figure 3a, the median

increased progressively with larger

values and reached a saturation region beyond

= 240. For low

settings (60–120), the interquartile range (IQR) and whisker lengths were relatively large, indicating substantial fold-to-fold variability; in contrast,

= 150 exhibited the narrowest box width and thus the most stable distribution. The

(

Figure 3b) exhibited a high median and large variability at

= 60, followed by a decreasing trend from

= 90 to

= 150. Beyond

= 180, the whiskers widened again, suggesting increased dispersion.

(

Figure 3c) reached its lowest median at

= 90 and then slightly increased up to

= 150, after which both the median and IQR grew steadily, indicating larger discrepancies among folds. Optimization time (

Figure 3d) varied nonlinearly with

. The range of

= 120–150 yielded the lowest and most stable computation times, whereas

= 240–270 exhibited markedly higher medians and greater variability, indicating increased computational overhead.

Table 3 quantitatively summarizes these trends using mean and standard deviation.

increased from 0.710 at

= 60 to a saturated level of approximately 0.757 beyond

= 40. The

= 150 configuration achieved an average

of 0.747 with the smallest standard deviation (±0.013). Although

= 180 achieved the lowest mean

(0.148), the absolute difference from

= 150 was only 0.004.

remained comparatively low at

= 150 (0.153 ± 0.012), outperforming the

= 180–390 range. Optimization time for

= 150 also fell within the shortest and most stable interval among the candidate configurations.

Based on these quantitative trends, = 150 was selected as the default configuration for all subsequent cross-validation and fusion experiments.

The results in

Table 4 indicate that the optimal performance was achieved not by the largest rule base but by an intermediate configuration (

= 150), where moderate pruning effectively removed redundant rules while preserving sufficient rule diversity. This pattern suggests that fuzzy rule systems benefit from a well-balanced rule base size, as both excessive pruning and minimal pruning can diminish representational capacity and overall efficiency.

The five-fold cross-validation results obtained under the

= 150 configuration are summarized in

Table 5. Each fold consisted of approximately 1166 training trajectories and 292 test trajectories, and the stratified partitioning ensured that the distribution of encounter types remained consistent across folds. The

ranged from 0.7252 to 0.7596, indicating minimal fold-to-fold variability, while the

and

also exhibited stable performance levels. The optimization time per fold ranged from approximately 1900 to 2600 s, confirming that the computational cost associated with the

= 150 model remains practical for real-world applications. These results demonstrate that the stable behavior observed in the

sensitivity analysis is consistently reproduced during full cross-validation, indicating that the selected configuration provides reliable predictive performance across diverse encounter scenarios.

The hyperparameters optimized for the

= 150 model via Bayesian optimization are presented in

Table 6, revealing parameter-specific variation patterns.

showed the highest stability, converging within a narrow range of 0.0301–0.0314 across all folds, while

also remained relatively consistent between 0.435 and 0.496. In contrast,

and

exhibited larger deviations, with fold 3 selecting comparatively higher values than the other folds.

remained extremely small (≤0.001) for most folds but increased substantially in fold 3, resulting in the largest inter-fold discrepancy among the parameters. Overall, while certain hyperparameters displayed strong convergence, others varied meaningfully depending on fold-specific data characteristics, indicating that the optimization process adapts dynamically to the underlying trajectory patterns.

To evaluate the contribution of the FOU within the proposed IT2FIS framework, a comparative experiment was conducted against the type-1 FIS baseline under identical modeling conditions, including the same input variables, the same three-level risk labels, and the same five-fold cross-validation partitions. The type-1 FIS was implemented by generating initial rules using subtractive clustering followed by ANFIS (adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system) training, and the optimal cluster radius (0.25) was determined through a grid search over the range [0.25, 0.60].

Table 7 summarizes the performance comparison between the two models. The IT2FIS achieved a 13.0% improvement in

over the type-1 FIS (0.661), and this difference was statistically significant (t = 7.546,

p = 0.0017). Furthermore, the

decreased by 42.2%, indicating that the IT2FIS more reliably identified high-risk situations compared with the Type-1 baseline (t = 7.322,

p = 0.0019). Overall, these results suggest that incorporating FOU into the inference process provides measurable benefits in terms of classification performance and robustness.

3.3. Performance Comparison of DS-Based Temporal Fusion Rules

The time-series outputs of the trained IT2FIS model were fused using four DST–based temporal combination rules—Dempster (DEMP), Yager, RCR-S, and RCR-L—and their performance was evaluated across all encounter cases. For each rule, optimal hyperparameters (

and

) were first identified within predefined search ranges, and

Table 8 summarizes the key performance metrics (

,

,

) obtained under these optimal configurations.

As shown in

Table 8, the fusion strategies form two clear groups depending on the temporal window

, which directly controls the temporal decay of accumulated evidence. In the wide-window group (RCR-S, DEMP), which operate with

values of 120 s and 150 s, the slow temporal decay of evidence produces stable long-term estimates. Accordingly, these methods achieved very low uncertainty (

= 0.0588 and 0.0606) and the best overall objective scores (0.1961 and 0.1982), with RCR-S providing the most balanced performance. In contrast, the Yager and RCR-L rules use short temporal windows (

= 30 s and 15 s), resulting in rapid temporal decay and strong emphasis on recent observations. This increased responsiveness yielded the highest

values (0.7493 and 0.7496) and lowest

scores (0.1633 and 0.1375), but at the cost of substantially higher uncertainty, particularly for RCR-L (

= 0.3817), which led to the poorest objective score (0.2428). Overall, slow-decay strategies (RCR-S, DEMP) provide stable and uncertainty-robust risk estimation, whereas fast-decay strategies (YAGER, RCR-L) enhance short-term sensitivity but lack long-term temporal stability.

The results in

Table 8 are obtained from a single evaluation using the final selected configuration, where IT2FIS-generated BPAs from cross-validation are used as fixed inputs. These results are presented for descriptive comparison rather than statistical inference.

Computational performance was evaluated using the developed model. An encounter was defined as a vessel pair, and computation time was measured per pair-update (per time step). The average processing time was 4.886 ± 1.176 ms for IT2FIS-based BPA generation and 0.170 ± 0.006 ms for RCR-S temporal fusion, resulting in an overall computation time of approximately 5.1 ms per encounter update. Given the typical update intervals used in operational AIS-based vessel monitoring systems, the proposed framework is suitable for real-time vessel monitoring applications.

3.4. Encounter Case Study

To examine the operational characteristics of the proposed IT2FIS–DST collision risk assessment framework, three representative encounter scenarios defined by the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs)—head-on, starboard crossing, and port crossing—were selected for detailed analysis. For each trajectory pair, fundamental geometric metrics such as the minimum DCPA, minimum distance, and initial relative bearing were computed, and encounter candidates were classified based on the COLREG-prescribed relative bearing sectors. Among trajectories falling within the head-on (354–6°), starboard crossing (6–112.5°), and port crossing (247.5–354°) domains, representative cases were selected using a weighted risk index composed of normalized DCPA and minimum distance (0.6·DCPA + 0.4·distance). The three resulting real-world encounter cases were subsequently used to evaluate and compare the temporal risk evolution generated by the proposed model.

3.4.1. Head-On Situation

Encounter case #1112 represents a prototypical head-on scenario in the dataset, in which the two vessels approached to a minimum distance of 0.243 km, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The own vessel (LOA 79 m), a general cargo ship, traveled at an average speed of 10.4 kt, while the target vessel (LOA 66 m) traveled at an average speed of 9.7 kt. Both vessels belonged to the general cargo category and therefore exhibited comparable maneuvering characteristics. Throughout the encounter, the own vessel maintained a relatively steady course, whereas the target vessel executed a starboard alteration to avoid collision.

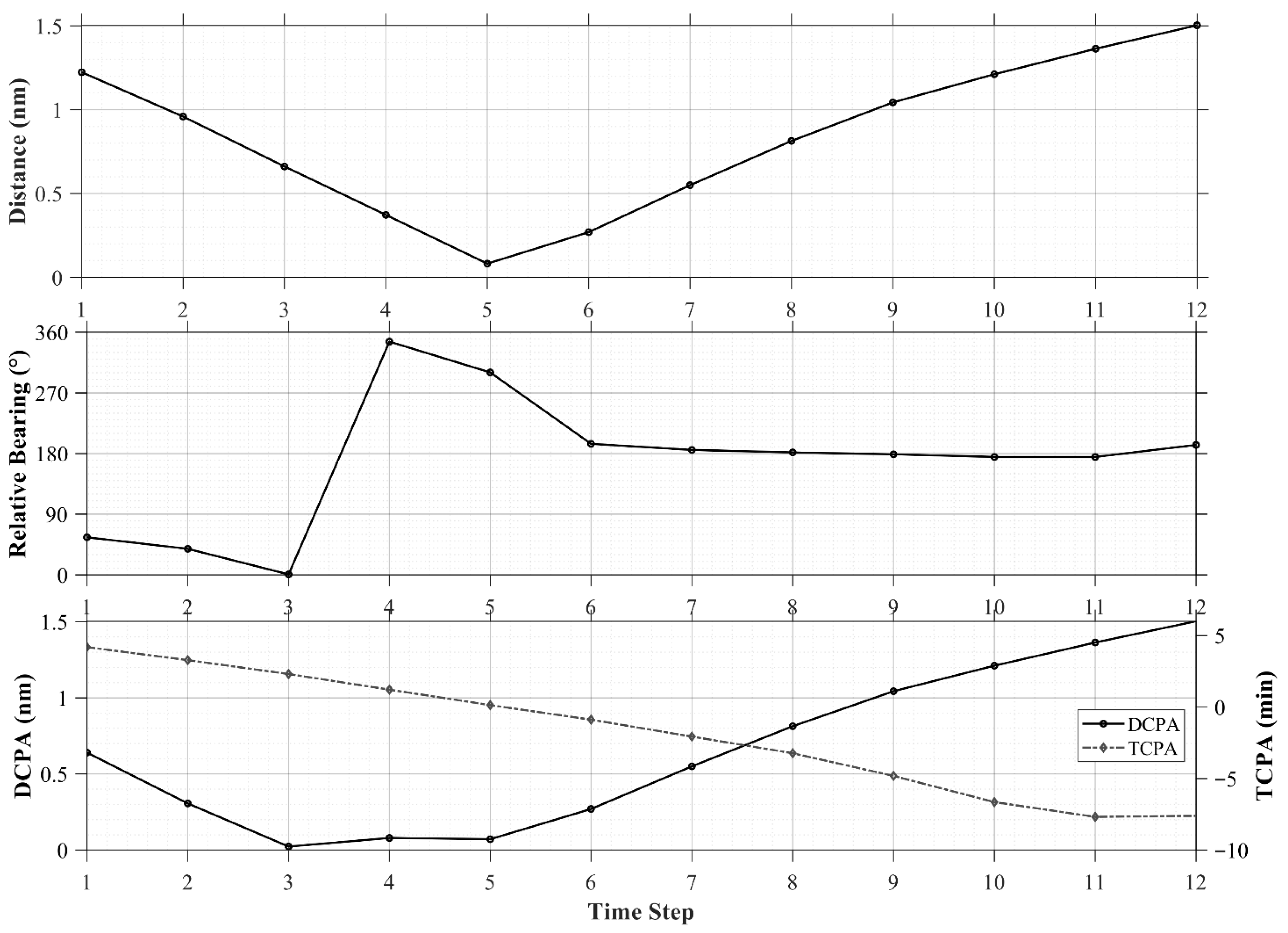

The kinematic profiles in

Figure 5 illustrate the typical relative-motion structure of a head-on encounter. The relative bearing initially started at 2.8°, fluctuated rapidly, and ultimately converged toward approximately 180° immediately prior to the closest approach, clearly reflecting the mutual head-on geometry. The distance decreased from an initial 2.17 nm to 0.13 nm and subsequently increased, forming the characteristic V-shaped pattern representing the approach–minimum-distance–separation sequence.

Additionally, the DCPA decreased from an initial value of 0.33 nm, indicating entry into a high-risk region, while the TCPA declined steadily from 6.39 min, accurately capturing both the moment of closest approach and the subsequent divergence phase.

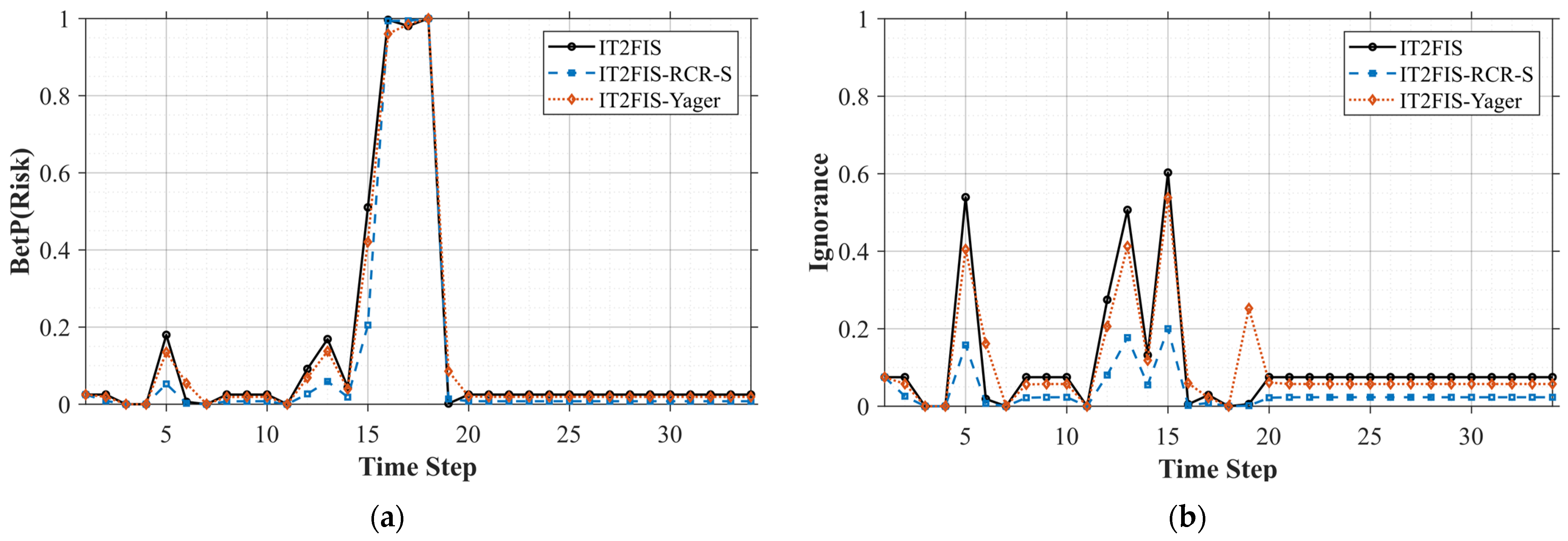

The time-varying risk estimates presented in

Figure 6a exhibit highly similar patterns across all three fusion strategies. During time steps 1–5, the risk level remained low with BetP ≤ 0.2. As the vessels rapidly closed in during steps 6–8, the estimated risk increased sharply, reaching its maximum near the minimum distance, and subsequently decreased to near zero after step 9 as the vessels executed avoidance maneuvers. All three strategies detected the onset and decline of risk at nearly identical time points, with closely aligned peak positions and durations.

In contrast, the ignorance time series shown in

Figure 6b reveals clearer differences among the fusion methods. Prior to the minimum distance, at step 5, IT2FIS exhibited a pronounced uncertainty peak of approximately 0.52, whereas IT2FIS-Yager produced a lower value of 0.39 and IT2FIS-RCR-S yielded the smallest uncertainty level at 0.17. When the risk reached its maximum during steps 6–8, all strategies converged toward near-zero ignorance, indicating that sufficient supporting evidence had accumulated to enable reliable risk assessment. Following the encounter, during steps 11–19, IT2FIS, IT2FIS-Yager, and IT2FIS-RCR-S maintained ignorance levels of approximately 0.08, 0.06, and 0.03, respectively. This demonstrates that IT2FIS-RCR-S consistently produced the lowest uncertainty throughout the entire scenario, while IT2FIS retained the highest residual uncertainty. In summary, although all three methods produced similar time-evolution profiles of risk in the head-on case, temporal fusion—and particularly the RCR-S rule—substantially reduced ignorance relative to the baseline IT2FIS output.

3.4.2. Starboard Crossing Situation

Encounter case #270 represents a typical starboard-crossing situation in which the own vessel (LOA 122 m) is required to keep out of the way of the target vessel (LOA 112 m) approaching from its starboard side. As shown in

Figure 7, the two vessels passed as close as 0.152 km, representing the closest encounter among the three case studies examined in this research. Both vessels were oil tankers and maintained comparable average speeds of 7.55 kt and 7.59 kt for the Own and Target vessels, respectively. During the encounter, the Own vessel executed a distinct starboard alteration to avoid collision.

The collision-risk indicators presented in

Figure 8 further highlight the geometric characteristics of a starboard-crossing encounter. The inter-vessel distance decreased sharply from 1.22 nm to 0.08 nm before increasing immediately thereafter, forming an asymmetric V-shaped pattern. The relative bearing began at 55.7°, shifted to 346.1° in response to the Own vessel’s alteration maneuver, and subsequently converged toward approximately 180° after passing, reflecting the canonical relative-motion structure of a starboard-crossing situation. Similarly, the DCPA steadily decreased from an initial value of 0.64 nm, indicating increasing proximity risk, while the TCPA decreased from approximately 4.19 min to zero and then turned negative, precisely marking the moment of minimum distance.

The BetP-based temporal risk estimates in

Figure 9a clearly illustrate the rapidly evolving risk characteristics of the starboard-crossing encounter. A moderate risk level of approximately 0.2–0.3 is already present at steps 1–2, indicating earlier risk perception compared with the head-on case. Subsequently, a sharp escalation in risk occurs during steps 3–4, with BetP reaching its maximum level, and the peak appearing at steps 4–5. The notably short duration of this peak indicates a rapidly developing close-quarters situation, which is typical of high-risk starboard-crossing encounters. After passing, the risk level declines swiftly to nearly zero over steps 6–12, confirming that the avoidance maneuver was successfully executed.

The ignorance time series in

Figure 9b exhibits even more pronounced differences among the fusion strategies. During the initial phase (steps 1–3), both IT2FIS and IT2FIS–Yager show high ignorance values exceeding 0.5, reflecting substantial initial uncertainty, whereas IT2FIS–RCR-S maintains considerably lower values, indicating greater stability in accumulated evidence. When the risk signal becomes clearer (steps 3–5), all three strategies converge toward near-zero ignorance. After passing (steps 6–8), all methods display a renewed increase in uncertainty; however, IT2FIS–RCR-S shows the smallest rise and consistently maintains the lowest overall ignorance level. These results demonstrate that IT2FIS–RCR-S offers the most stable suppression of uncertainty across both pre-encounter and post-encounter phases.

3.4.3. Port Crossing Situation

Encounter case #20 represents a typical port-crossing situation in which the target vessel (LOA 110 m) approaches from the port side while the own vessel (LOA 211 m) acts as the stand-on vessel. As illustrated in

Figure 10, the two vessels closed to a minimum distance of 0.250 km. The own vessel, a general cargo ship, proceeded at an average speed of 8.3 kt, whereas the target vessel, a tanker, was sailing at an average speed of 9.5 kt. During the encounter, the target vessel executed a starboard alteration to avoid collision, while the own vessel—despite being the stand-on vessel—also altered course to port; nevertheless, the vessels passed each other without incident.

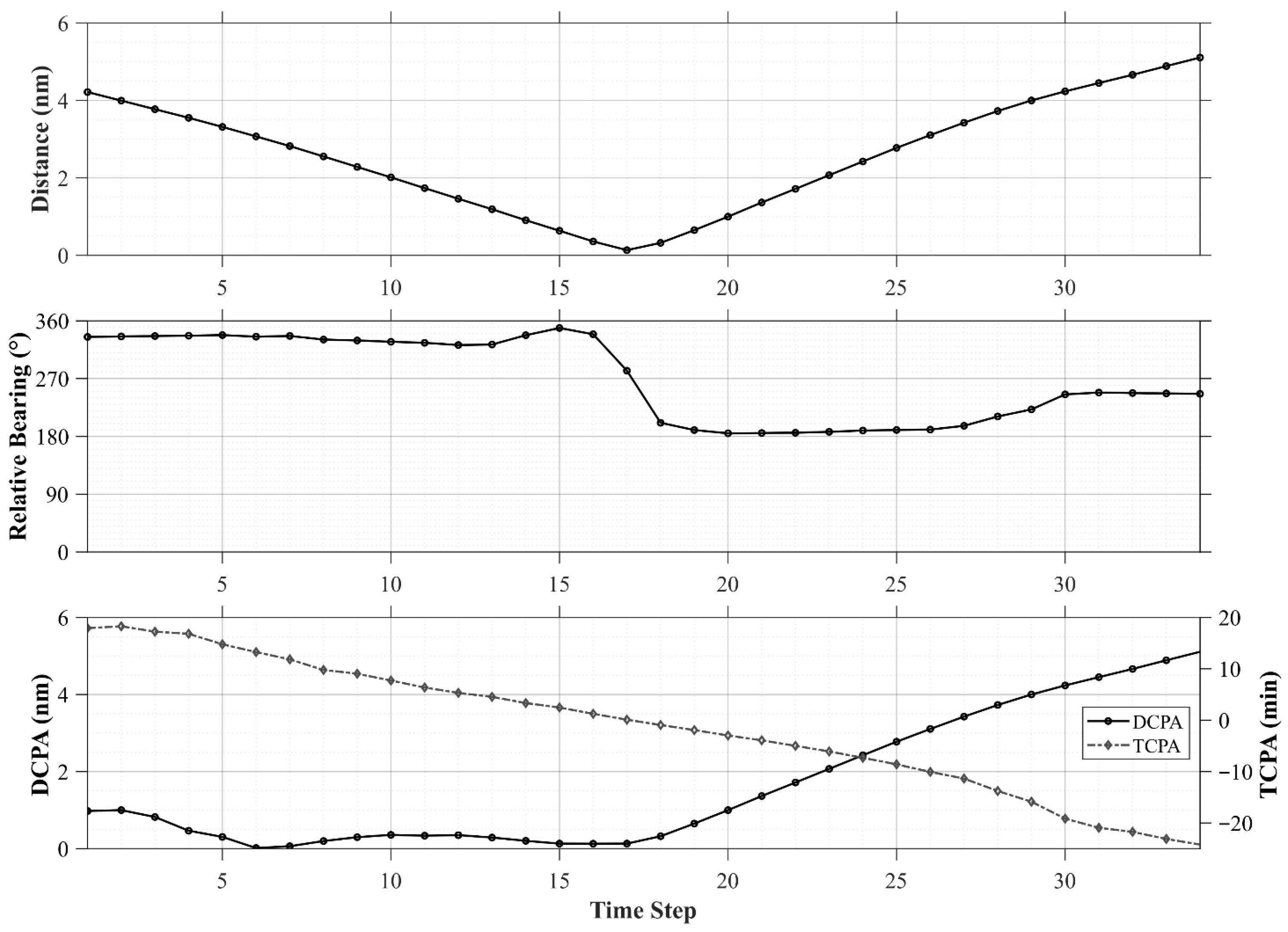

The collision-risk metrics presented in

Figure 11 clearly capture the characteristics of this encounter. The distance gradually decreased from 4.22 nm to 0.14 nm before increasing again, depicting the approach–passing–separation sequence. The relative bearing began at approximately 334.9°, shifted rapidly during the approach phase, and converged to around 180° at the passing moment, accurately reflecting the geometric structure of a port-crossing situation. Additionally, the DCPA exhibited a long-term gradual decrease from an initial value of 0.98 nm, while the TCPA steadily declined from 17.92 min to zero before turning negative, indicating the relatively gradual evolution of this encounter.

The BetP-based temporal risk estimates shown in

Figure 12a exhibit broadly similar patterns across all fusion strategies. During the gradual approach phase (time steps 1–14), the estimated risk remained very low, with BetP values below 0.2. A pronounced high-risk interval emerged at time steps 15–18, where the BetP values sharply increased and approached 1.0, capturing the onset of the closest-point interaction. Following this peak, the risk decreased rapidly from time step 19 onward as the vessels entered the passing and separation phases, ultimately stabilizing at values below 0.05.

In contrast, the Ignorance time series in

Figure 12b reveals clear differences among the fusion strategies in their handling of uncertainty. The baseline IT2FIS exhibited prominent uncertainty peaks exceeding 0.5 at time steps 5 and 12–15, reflecting its heightened sensitivity to local input fluctuations. The IT2FIS-RCR-S method, however, maintained the lowest Ignorance levels—approximately 0.18–0.22 in the same intervals—demonstrating its superior capability for suppressing uncertainty. The IT2FIS-Yager rule achieved lower uncertainty than the baseline IT2FIS, yet consistently higher than that of IT2FIS-RCR-S.

4. Discussion

This study proposed a new collision-risk assessment framework that integrates an IT2FIS with DST to address the inherent uncertainty present in AIS measurements. The approach represents sensor errors, environmental variability, and behavioral ambiguity through the FOU and transforms these characteristics into time-indexed BPAs that are systematically incorporated into the temporal evidence-combination process. This yields a more robust assessment than conventional type-1 fuzzy or single-time-point models. In particular, integrating Lenart’s time-based criterion with Fujii’s spatial vessel-domain into a three-level risk label enables the model to capture gradual transitions in collision risk that binary schemes fail to represent, resulting in a more realistic depiction of encounter dynamics.

The sensitivity analysis highlighted a clear trade-off between model complexity and performance. steadily increased with larger rule bases and saturated beyond = 240, while remained lowest and most stable within the 150–180 range. stayed relatively low for = 90–150 but increased at higher rule counts, and computation time exhibited an irregular pattern with its most efficient and stable behavior at = 120–150. Overall, = 150 provided the most balanced configuration in terms of accuracy, uncertainty reduction, and efficiency, with minimal variability across folds. These patterns, consistently observed under stratified five-fold cross-validation with Bayesian optimization, indicate that expanding the rule base does not necessarily yield better performance, and that structural simplicity can enhance model stability in operational environments.

Temporal evidence-fusion experiments further revealed distinct behavioral characteristics among combination rules. All fusion strategies were evaluated under identically pre-optimized and settings, and the RCR-S rule exhibited the most consistent uncertainty suppression. IT2FIS-RCR-S reduced from 0.1525 (baseline IT2FIS) to 0.0588 while maintaining stable performance in and . This improvement stems from the rule’s adaptive weighting between conjunctive and disjunctive behavior based on conflict intensity, thereby mitigating the excessive normalization of Dempster’s rule and the elevated uncertainty typical of Yager’s rule. In contrast, IT2FIS-YAGER and IT2FIS-RCR-L demonstrated higher responsiveness to risk fluctuations but suffered from increased uncertainty, leading to lower overall objective performance. These comparisons emphasize that, in collision-risk assessment, stable suppression of uncertainty can be more critical than heightened sensitivity alone.

Case studies based on COLREG-defined encounter situations further validated the practical effectiveness of the proposed framework. Across head-on, starboard-crossing, and port-crossing scenarios, the model successfully reproduced the temporal evolution of risk—characterized by rising, peak, and diminishing phases—while reflecting encounter geometry and evasive maneuvers in the BetP time series. IT2FIS-RCR-S consistently exhibited substantially lower uncertainty than the standalone IT2FIS output, particularly around the minimum-distance region. This demonstrates the superiority of temporal fusion over single-shot assessments for real-time situation awareness and decision reliability, underscoring the framework’s potential utility in maritime autonomous surface ship (MASS) operations and vessel traffic service (VTS) environments.

Although the present analysis focuses on pairwise vessel encounters without explicitly modeling fairway geometry or traffic separation schemes, the study area includes port-approach waters where such navigational constraints may be encountered. The proposed framework is designed to assess collision risk based on relative-motion variables. This enables temporally consistent and uncertainty-aware risk indications that complement conventional CPA-based alarms across both open-water and constrained environments.

Despite these promising results, the study has several limitations. The analysis relied on AIS data collected over an 18-day period from a single coastal region (Busan–Ulsan), which may constrain generalizability to other waterways or seasonal conditions. The model assumes pairwise vessel encounters and does not account for multi-vessel interactions, which are common in real maritime traffic. In addition, safety distances and vessel-domain parameters derived from Lenart and Fujii may require adaptation for different vessel types and traffic characteristics. Key parameter settings, including the time-to-safety threshold and the Fujii elliptical safety domain coefficients, were adopted based on established formulations in prior studies, but their sensitivity to varying operational conditions was not examined here. From a methodological perspective, the proposed framework may also exhibit reduced reliability under certain conditions. Encounters with sparse or irregular AIS reporting may limit the ability of discrete-time observations to capture abrupt changes in relative geometry. Although the IT2FIS structure is designed to mitigate short-term noise and minor data gaps through the FOU, prolonged missing data are expected to increase uncertainty and weaken temporal consistency. In addition, situations involving highly conflicting evidence, such as ambiguous encounter geometries or frequent maneuvering, may lead to elevated ignorance within the DST fusion process, resulting in conservative or delayed risk escalation. Moreover, although representative high-risk near-collision cases were examined, full reconstruction of documented collision incidents was beyond the scope of the available data. In this context, environmental factors such as weather and visibility conditions could be considered in future extensions by adjusting the uncertainty bounds of the fuzzy membership functions or the reliability of the associated BPAs. Future work should therefore incorporate parameter-sensitivity analyses, adaptive domain formulations, large-scale multi-season AIS datasets, dynamic fusion-parameter adaptation based on encounter type, integration of mariner perception studies, and quantitative comparisons with statistical and machine-learning models, as well as verified accident reconstructions, to enhance operational applicability.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an uncertainty-aware collision-risk assessment framework that integrates an IT2FIS with DST and demonstrates its effectiveness using real-world AIS data from a coastal traffic environment. By jointly incorporating Lenart’s temporal criterion and Fujii’s spatial vessel-domain concept into a three-level risk labeling scheme, the proposed approach enables a more nuanced and temporally consistent representation of collision risk evolution than conventional binary or single-time-point methods.

The IT2FIS component captures uncertainty arising from sensor noise, environmental variability, and maneuvering ambiguity through the footprint of uncertainty, while the DST-based temporal fusion mechanism aggregates time-indexed evidence to stabilize risk assessment over successive observations. Sensitivity analysis further indicates that increasing model complexity does not necessarily improve performance, and that a moderately sized rule base provides a robust balance between accuracy, uncertainty reduction, and computational efficiency. Among the examined fusion strategies, the RCR-S rule consistently achieved superior uncertainty suppression while maintaining stable detection performance, highlighting the importance of conflict-aware temporal fusion in safety-critical maritime applications.

Case studies based on COLREG-defined encounter situations further confirmed that the proposed framework can reliably reproduce the temporal progression of collision risk, including escalation, peak risk, and resolution phases associated with evasive maneuvers. The reduced uncertainty observed in the temporally fused belief outputs, particularly near minimum-distance regions, demonstrates the advantage of sequential evidence integration over instantaneous risk estimation. These characteristics make the proposed framework well suited for practical maritime safety applications where reliable and interpretable risk information is required under time-varying and uncertain conditions.

From a practical perspective, the proposed IT2FIS–DST framework has clear implications for real-time maritime safety systems. Its interpretable structure and uncertainty-aware design make it suitable for deployment in vessel traffic service (VTS) decision-support environments, where operators must continuously assess evolving encounter situations involving incomplete and noisy information. Moreover, the framework can serve as a risk-assessment module within maritime autonomous surface ship (MASS) navigation systems, supporting risk-aware collision-avoidance decision making and human-in-the-loop supervision in accordance with e-Navigation principles.

Future research will focus on extending the proposed framework in several directions. These include validation using larger and multi-season AIS datasets from diverse waterways, extension to large-scale multi-vessel encounter scenarios, and adaptive tuning of fuzzy membership functions and fusion parameters based on encounter type and traffic conditions. Incorporating environmental factors such as weather and visibility through uncertainty modulation, as well as integrating mariner risk perception and verified accident reconstructions, will further enhance operational realism. In addition, systematic quantitative comparisons with statistical and machine-learning-based approaches under consistent experimental settings represent an important avenue for future investigation. Through these extensions, the proposed framework can be further developed into a robust and operationally applicable collision-risk assessment solution supporting next-generation maritime safety systems.