Assessing the Impact of Port Emissions on Urban PM2.5 Levels at an Eastern Mediterranean Island (Chios, Greece)

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Quantify ship-related PM2.5 increments during docking events.

- Characterize seasonal and spatial variations between urban and suburban monitoring sites.

- Determine the key meteorological and ship related factors that influence plume transport.

- Build a data-driven, scientific understanding of ship plume impacts in insular environments to guide effective mitigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

| Characteristic | Ship A | Ship B | Ship C | Ship D | Ship E | Ship F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gross tonnage (GT) | 30,694 | 29,422 | 15,362 | 8126 | 8126 | 5466 |

| Deadweight (DWT) (tons) | 7622 | 6148 | 3348 | 1960 | 1960 | 8661 |

| Length overall (m) | 192.91 | 192.50 | 141.54 | 141 | 141 | 154 |

| Beam (m) | 29.40 | 27.28 | 23.00 | 21 | 21 | 21.67 |

| Year built | 1988 | 1987 | 1990 | 2007 | 2007 | 1978 |

| Passengers | 2213 | 2210 | 1462 | 1715 | 1715 | 12 |

| Cars | ~750 | ~748 | 274 | 418 | 418 | - |

| Lane meters (m) | 2400 | 2105 | ~900 | - | - | 1650 |

| Total engine power (MW) | 17.5 | ~17.2 | ~9.8 | 31.7 | 31.7 | 11.6 |

| Max speed (kt) | ~20.5 | ~22 | ~21 | - | - | - |

| Number of calls at port (August and February 2022) | 57 | 44 | 30 | 12 | 14 | 13 |

| Average time at port per call (min) | 47 | 46 | 37 | 20 | 21 | 60 |

2.2. Materials

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

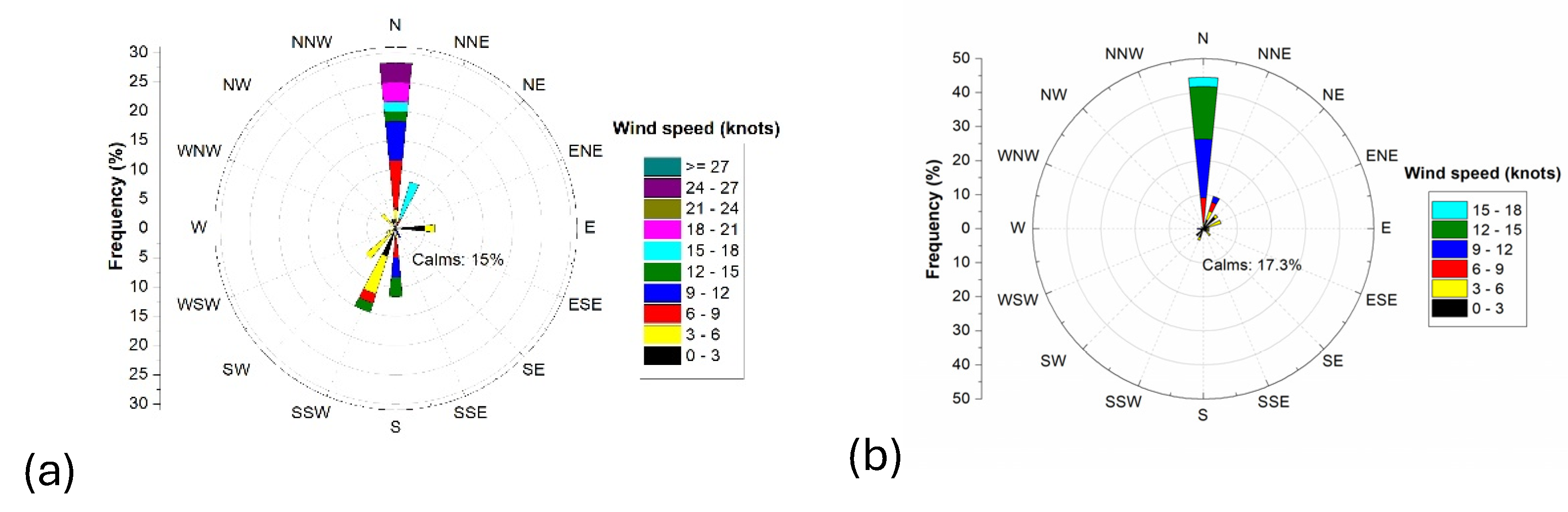

2.3.1. Wind Direction

2.3.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of the Influence of Ship Docking Events on PM2.5 Levels in Chios City

3.2. Uncertainty Analysis of PM2.5 Enhancements by Wind Sector

3.3. Correlation of Concentration Change with Ship’s Particulars and Meteorology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIS | Automatic Identification System |

| DWT | Deadweight Tonnage |

| ΔC and % ΔC | Absolute and Relative PM2.5 Concentration Change During Docking |

| ECA | Emission Control Area |

| EMSA | European Maritime Safety Agency |

| GT | Gross Tonnage |

| HNMS | Hellenic National Meteorological Service |

| ISM Code | International Safety Management Code |

| MGO | Marine Gas Oil |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter with Aerodynamic Diameter ≤ 2.5 µm |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter with Aerodynamic Diameter ≤ 10 µm |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| Ro-Pax | Roll-on/Roll-off Passenger Ship |

| Ro–Ro | Roll-on/Roll-off Cargo Ship |

| VLSFO | Very Low Sulphur Fuel Oil |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

References

- Verschuur, J.; Koks, E.E.; Hall, J.W. Ports’ Criticality in International Trade and Global Supply-Chains. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boile, M.; Theofanis, S.; Perra, V.-M.; Kitsios, X. Coastal Shipping during the Pandemic: Spatial Assessment of the Demand for Passenger Maritime Transport. Front. Future Transp. 2023, 4, 1025078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa Zadeh, S.B.; López Gutiérrez, J.S.; Esteban, M.D.; Fernández-Sánchez, G.; Garay-Rondero, C.L. Scope of the Literature on Efforts to Reduce the Carbon Footprint of Seaports. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.; Williams, I.; Preston, J.; Clarke, N.; Odum, M.; O’Gorman, S. Ports in a Storm: Port-City Environmental Challenges and Solutions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Mfum, S.; Hudson, M.D.; Osborne, P.E.; Roberts, T.J.; Zapata-Restrepo, L.M.; Williams, I.D. Atmospheric Pollution in Port Cities. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobarra, D.; Yubero, E.; Carratala, A. Trends of Anthropogenic Sources in a Southeastern Mediterranean Coastal Site over Five Years. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 355, 121279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Czech, H.; Anders, L.; Passig, J.; Etzien, U.; Bendl, J.; Streibel, T.; Adam, T.W.; Buchholz, B.; Zimmermann, R. Impact of Fuel Sulfur Regulations on Carbonaceous Particle Emission from a Marine Engine. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasopolos, A.T.; Hopke, P.K.; Sofowote, U.M.; Mooibroek, D.; Zhang, J.J.Y.; Rouleau, M.; Peng, H.; Sundar, N. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Low-Sulphur Marine Fuel Regulations at Improving Urban Ambient PM2.5 Air Quality: Source Apportionment of PM2.5 at Canadian Atlantic and Pacific Coast Cities with Implementation of the North American Emissions Control Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.; Hammingh, P.; Colette, A.; Querol, X.; Degraeuwe, B.; Vlieger, I.D.; Van Aardenne, J. Impact of Maritime Transport Emissions on Coastal Air Quality in Europe. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 90, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merico, E.; Donateo, A.; Gambaro, A.; Cesari, D.; Gregoris, E.; Barbaro, E.; Dinoi, A.; Giovanelli, G.; Masieri, S.; Contini, D. Influence of In-Port Ships Emissions to Gaseous Atmospheric Pollutants and to Particulate Matter of Different Sizes in a Mediterranean Harbour in Italy. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 139, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Russo, M.; Gama, C.; Borrego, C. How Important Are Maritime Emissions for the Air Quality: At European and National Scale. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fameli, K.M.; Kotrikla, A.M.; Psanis, C.; Biskos, G.; Polydoropoulou, A. Estimation of the Emissions by Transport in Two Port Cities of the Northeastern Mediterranean, Greece. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandolfi, M.; Gonzalez-Castanedo, Y.; Alastuey, A.; De La Rosa, J.D.; Mantilla, E.; De La Campa, A.S.; Querol, X.; Pey, J.; Amato, F.; Moreno, T. Source Apportionment of PM10 and PM2.5 at Multiple Sites in the Strait of Gibraltar by PMF: Impact of Shipping Emissions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2011, 18, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducruet, C.; Polo Martin, B.; Sene, M.A.; Lo Prete, M.; Sun, L.; Itoh, H.; Pigné, Y. Ports and Their Influence on Local Air Pollution and Public Health: A Global Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, N.; Pey, J.; Reche, C.; Cortés, J.; Alastuey, A.; Querol, X. Impact of Harbour Emissions on Ambient PM10 and PM2.5 in Barcelona (Spain): Evidences of Secondary Aerosol Formation within the Urban Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Jiao, L.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Du, W.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y.; Deng, J.; Hong, Y.; Chen, J. Source Identification of PM2.5 at a Port and an Adjacent Urban Site in a Coastal City of China: Impact of Ship Emissions and Port Activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavroulas, I.; Grivas, G.; Liakakou, E.; Kalkavouras, P.; Bougiatioti, A.; Kaskaoutis, D.G.; Lianou, M.; Papoutsidaki, K.; Tsagkaraki, M.; Zarmpas, P.; et al. Online Chemical Characterization and Sources of Submicron Aerosol in the Major Mediterranean Port City of Piraeus, Greece. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, D. The Impact of Shipping on Air Quality in the Port Cities of the Mediterranean Area: A Review. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, D.; Gambaro, A.; Belosi, F.; De Pieri, S.; Cairns, W.R.L.; Donateo, A.; Zanotto, E.; Citron, M. The Direct Influence of Ship Traffic on Atmospheric PM2.5, PM10 and PAH in Venice. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2119–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donateo, A.; Gregoris, E.; Gambaro, A.; Merico, E.; Giua, R.; Nocioni, A.; Contini, D. Contribution of Harbour Activities and Ship Traffic to PM2.5, Particle Number Concentrations and PAHs in a Port City of the Mediterranean Sea (Italy). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 9415–9429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Louie, P.K.K.; Li, M.; Fu, Q. Atmospheric Pollution from Ships and Its Impact on Local Air Quality at a Port Site in Shanghai. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 6315–6330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkavouras, P.; Bougiatioti, A.; Grivas, G.; Stavroulas, I.; Kalivitis, N.; Liakakou, E.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Pilinis, C.; Mihalopoulos, N. On the Regional Aspects of New Particle Formation in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Comparative Study between a Background and an Urban Site Based on Long Term Observations. Atmos. Res. 2020, 239, 104911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrlis, E.; Lelieveld, J. Climatology and Dynamics of the Summer Etesian Winds over the Eastern Mediterranean. J. Atmos. Sci. 2013, 70, 3374–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, M. Chian Shipping: The Merchant Marine of Chios Through the Ages; Private Edition: Chios, Greece, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Athanasiadou, E.; Paraskevopoulou, A.T. Agricultural Heritage Landscapes of Greece: Three Case Studies and Strategic Steps towards Their Acknowledgement, Conservation and Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShipNext Ports. Available online: https://shipnext.com/port/chios-grjkh-grc (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- EMSA. The EU Maritime Profile. Available online: https://www.emsa.europa.eu/eumaritimeprofile/section-2-the-eu-maritime-cluster.html#ownership (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- IACS. A Guide to Managing Maintenance in Accordance with the Requirements of the ISM Code. Available online: https://safety4sea.com/wp-content/uploads/ISM-Code/REC74%202008%20%28Managing%20Maintenance%29.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Marine Traffic Vessels. Available online: https://www.marinetraffic.com/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Vessel Finder Vessels. Available online: https://www.vesselfinder.com/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Stavroulas, I.; Grivas, G.; Michalopoulos, P.; Liakakou, E.; Bougiatioti, A.; Kalkavouras, P.; Fameli, K.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Mihalopoulos, N.; Gerasopoulos, E. Field Evaluation of Low-Cost PM Sensors (Purple Air PA-II) Under Variable Urban Air Quality Conditions, in Greece. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fameli, K.-M.; Kotrikla, A.-M.; Kalkavouras, P.; Polydoropoulou, A. The Influence of Meteorological Parameters on PM2.5 Concentrations on the Aegean Islands. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2023, 26, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSalehy, A.S.; Bailey, M. Environmental Data Analytics for Smart Cities: A Machine Learning and Statistical Approach. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megaritis, A.G.; Fountoukis, C.; Charalampidis, P.E.; Denier Van Der Gon, H.A.C.; Pilinis, C.; Pandis, S.N. Linking Climate and Air Quality over Europe: Effects of Meteorology on PM2.5 Concentrations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 10283–10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhou, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Duan, Y.; Li, J. Intense Secondary Aerosol Formation Due to Strong Atmospheric Photochemical Reactions in Summer: Observations at a Rural Site in Eastern Yangtze River Delta of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 571, 1454–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, K.; Grivas, G.; Liakakou, E.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Mihalopoulos, N. Assessing the Contribution of Regional Sources to Urban Air Pollution by Applying 3D-PSCF Modeling. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriou, K.; Stavroulas, I.; Grivas, G.; Chatzidiakos, C.; Kosmopoulos, G.; Kazantzidis, A.; Kourtidis, K.; Karagioras, A.; Hatzianastassiou, N.; Pandis, S.Ν.; et al. Intra- and Inter-City Variability of PM2.5 Concentrations in Greece as Determined with a Low-Cost Sensor Network. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 301, 119713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ma, Z.; Yuang, Z. Urban Design and Pollution Using AI: Implications for Urban Development in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgabi, N.A.; Mokgwetsi, T. Dilution and Dispersion of Inhalable Particulate Matter. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 127, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeke, R.; Matthias, V.; Grawe, D. Parameterizing the Vertical Downward Dispersion of Ship Exhaust Gas in the near Field. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 5935–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMEP/EEA. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2023. 1.A.3.d Navigation. 2023. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2023 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Issa Zadeh, S.B. Environmental Benefits of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Smart Ports via Implementation of Smart Energy Infrastructure. GMSARN Int. J. 2024, 18, 431–439. [Google Scholar]

| Month | Site | ΔC (μg/m3) | % ΔC | Wind Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2022 | Urban | −0.3 | −1.7 | All directions (60 obs.) |

| Suburban | −0.2 | −1.7 | ||

| August 2022 | Urban | 2.8 | 28 | All directions (110 obs.) |

| Suburban | 0.3 | 3.4 | ||

| February 2022 | Urban | 0.8 | 6.1 | Northern (23 obs.) |

| Suburban | 0.3 | 2.3 | ||

| August 2022 | Urban | 5.0 | 48 | Northern (58 obs.) |

| Suburban | 0.4 | 4.5 | ||

| February 2022 | Urban | 0.7 | 4.7 | Southern (10 obs.) |

| Suburban | 2.4 | 27 | ||

| August 2022 | Urban | −0.7 | −5.1 | Southern (1 obs.) |

| Suburban | 0.0 | −0.3 | ||

| February & August 2022 combined | Urban | 1.7 | 19 | All directions (170 obs.) |

| Suburban | 0.1 | 3.0 |

| Wind Sector | N | Median %ΔC | IQR %ΔC | 95% CI %ΔC (Bootstrap) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northerly | 81 | 25.5 | 35.6 | [18.4, 31.5] |

| Southerly | 10 | −0.8 | 23.2 | [−7.0, 19.4] |

| Other | 79 | 0.3 | 19.1 | [−2.5, 4.8] |

| All sectors | 170 | 9.7 | 34.0 | [5.2, 14.3] |

| All sectors, excluding southerly | 160 | 10.7 | 34.0 | [5.8, 14.9] |

| Urban Station | Suburban Station | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coef. | Significance | Correlation Coef. | Significance | |

| Power (kW) | 0.02 | 0.76 | −0.02 | 0.84 |

| Time at port (min) | 0.02 | 0.77 | −0.10 | 0.22 |

| Weed speed (kt) | 0.33 ** | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.74 |

| wd_sin | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.68 |

| wd_cos | 0.34 ** | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Temperature (°C) | 0.34 ** | <0.001 | 0.17 * | 0.03 |

| Dew Point (°C) | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.17 * | 0.03 |

| Pressure (hPa) | −0.16 * | 0.04 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kotrikla, A.M.; Fameli, K.M.; Polydoropoulou, A.; Grivas, G.; Kalkavouras, P.; Mihalopoulos, N. Assessing the Impact of Port Emissions on Urban PM2.5 Levels at an Eastern Mediterranean Island (Chios, Greece). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010035

Kotrikla AM, Fameli KM, Polydoropoulou A, Grivas G, Kalkavouras P, Mihalopoulos N. Assessing the Impact of Port Emissions on Urban PM2.5 Levels at an Eastern Mediterranean Island (Chios, Greece). Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleKotrikla, Anna Maria, Kyriaki Maria Fameli, Amalia Polydoropoulou, Georgios Grivas, Panayiotis Kalkavouras, and Nikolaos Mihalopoulos. 2026. "Assessing the Impact of Port Emissions on Urban PM2.5 Levels at an Eastern Mediterranean Island (Chios, Greece)" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010035

APA StyleKotrikla, A. M., Fameli, K. M., Polydoropoulou, A., Grivas, G., Kalkavouras, P., & Mihalopoulos, N. (2026). Assessing the Impact of Port Emissions on Urban PM2.5 Levels at an Eastern Mediterranean Island (Chios, Greece). Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010035