1. Introduction

As a key component of global trade and marine activities, the ocean places increasing demands on the performance of underwater exploration technologies. Autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), which act as primary platforms for carrying sensing and inspection equipment, play an important role in a wide range of underwater engineering tasks. These applications require AUVs to exhibit high levels of responsiveness, accuracy, and stability in motion control.

This study focuses on trajectory tracking control, which represents a fundamental problem in underwater vehicle motion control. Unlike simple position regulation, trajectory tracking is time-dependent and requires the vehicle to accurately follow a predefined time-varying path in both position and velocity. After deployment from a mothership or docking station, AUVs are typically expected to follow prescribed trajectories to perform underwater exploration missions. However, variations in vehicle structures and onboard payload configurations introduce internal modeling uncertainties. In addition, complex hydrodynamic disturbances, such as turbulence and vortices commonly encountered in ports and coastal environments, further challenge control system performance. Consequently, a variety of control methodologies have been investigated for AUV motion control, including robust control, adaptive control, backstepping control, and intelligent control approaches.

Han et al. [

1] proposed an adaptive fuzzy backstepping control method that integrates a command filter with an adaptive fuzzy scheme. The method constructs virtual control functions based on quantized state feedback to handle discontinuous states and model uncertainties. However, its recursive design introduces considerable computational complexity and relies heavily on expert knowledge for controller tuning. Du et al. [

2] presented an adaptive backstepping sliding mode control strategy employing a condition-based adaptation mechanism, in which the control gain is updated only when necessary to enhance system stability. This approach exhibits adaptability to coupled nonlinearities, unknown system parameters, uncertain disturbances, and input saturation. Tian et al. [

3] developed a trajectory tracking framework combining Bayesian optimization with nonlinear model predictive control (NMPC). Although improved tracking performance was reported, the required system linearization results in high computational burden and still depends on accurate dynamic modeling. Among these approaches, sliding mode control (SMC) is particularly attractive due to its low dependence on precise system models, inherent robustness against disturbances, and guaranteed convergence properties. Owing to these advantages, SMC is adopted in this study as the baseline control strategy for addressing AUV trajectory tracking problems under high robustness requirements.

Sliding mode control is characterized by fast dynamic response, rapid convergence, and a clearly defined control structure, which makes it suitable for practical engineering applications. Hu et al. [

4] introduced an adaptive SMC scheme with predefined performance by designing a sliding surface that explicitly incorporates desired closed-loop behavior, while an adaptive law was employed to estimate external disturbances and uncertain parameters. Nevertheless, predefined performance constraints may become inadequate when the system is subject to sudden or unexpected environmental variations. Luo and Liu [

5] employed a nonlinear disturbance observer to estimate complex external disturbances and improved the integral sliding surface by introducing extended exponential terms for parameter tuning. However, the associated parameters lack adaptability to changing environments, and the method was validated only for trajectory tracking on the horizontal plane. An et al. [

6] developed a fixed-time disturbance observer to estimate unknown external disturbances and implemented an integral sliding mode control (ISMC) scheme, where high-order error terms were incorporated to enhance robustness against uncertainties. Close et al. [

7] combined proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control with fixed-time sliding mode control (FTSMC), smoothing the switching behavior of the control input to achieve fast convergence while mitigating chattering. Guerrero et al. [

8] proposed a saturation-based super-twisting algorithm (STA) within the framework of high-order sliding mode control (HOSMC), extending its application to multi-input multi-output (MIMO) systems and achieving improved tracking accuracy compared with conventional STA methods. Most existing studies addressing chattering in SMC focus on modifying the discontinuous switching function, whereas relatively few investigate how system state information influences control performance. Moreover, the integration of emerging learning-based techniques into SMC-based trajectory tracking remains limited. Inspired by the hybrid control paradigms reported in Gao et al. [

9] and Roopaei et al. [

10], this study explores the feasibility of incorporating autonomous learning capabilities into classical sliding mode control, with the aim of combining modern data-driven methods with traditional control theory.

Intelligent control methods have been widely applied in complex dynamic systems due to their adaptability and self-tuning capabilities. Ebrahimpour et al. [

11] addressed internal and external disturbances in quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) by designing a hybrid control law that combines fuzzy logic control (FLC) with integral sliding mode control (ISMC), supplemented by a disturbance observer to estimate signal gains and mitigate chattering. However, internal model disturbances were not explicitly considered in their framework. Dong et al. [

12] proposed a data-driven adaptive fuzzy sliding mode control scheme in which real-time model parameters are extracted from navigation data and fuzzy control principles are employed to reduce convergence time and chattering. Nevertheless, parameter identification based on recursive least squares (RLS) suffers from limited accuracy and adaptability under rapidly varying conditions. Jiang et al. [

13] employed a radial basis function neural network to model and estimate system uncertainties and time-varying disturbances. Although this approach enhances adaptability, directly learning the system structure through the neural network substantially increases exploration complexity. Despite being developed within the sliding mode control framework, most of the aforementioned methods still rely heavily on prior knowledge and accurate system models. Wang et al. [

14] developed a model-free reinforcement learning approach based on deterministic policy gradients, using a continuous hybrid modeling framework for adaptive tuning of SMC parameters. While this method is suitable for highly uncertain and complex systems, it introduces considerable training cost and implementation complexity due to the use of multiple reinforcement learning modules and a large number of hyperparameters. Moreover, when applied independently to trajectory tracking problems, reinforcement learning methods often face challenges such as high-dimensional state spaces and susceptibility to local optima, which may lead to slow or unstable convergence.

To address these limitations, this study combines deep reinforcement learning (DRL) with SMC to improve AUV trajectory tracking performance. DRL employs deep neural networks as function approximators and has shown potential in reducing the strong dependence of control strategies on accurate hydrodynamic models. Zhang et al. [

15] integrated DRL with PID control in a dock-handling system, where multiple controllers generated candidate control signals that were evaluated and weighted through a neural network-based quality assessment mechanism. Lee and Kim [

16] applied a deep Q-network (DQN) for navigation path planning, followed by conventional control strategies for trajectory tracking. Fang et al. [

17] demonstrated that DRL enables rapid deployment of trajectory and position tracking tasks in AUVs without requiring full system identification. Similarly, Wang et al. [

18] reported that DRL-based path-following algorithms exhibit promising generalization in uncertain ocean environments. More recently, data-driven roadmaps for marine robotics presented by Ma et al. [

19] identified DRL as a key direction for future intelligent control architectures, highlighting its capability to enhance adaptability under environmental uncertainty. In addition, Usama et al. [

20] integrated DRL with robust control frameworks, such as active disturbance rejection control (DRL-ADRC), illustrating how learning-based adaptation can be combined with classical robustness guarantees. Collectively, these studies provide methodological support for developing control strategies with reduced reliance on precise model accuracy, which motivates the proposed DRL-enhanced IISMC framework in this paper.

In parallel, the integration of DRL with SMC has been increasingly investigated as an effective approach to address the long-standing chattering problem. Li et al. [

21] proposed an RL-guided optimization strategy for nonlinear switching functions, enabling adaptive suppression of high-frequency oscillations without compromising robustness. Similarly, Qiu et al. [

22] introduced a cross-domain framework in which RL was employed to tune SMC parameters for vibration attenuation, demonstrating the feasibility of combining data-driven learning with classical discontinuous control laws.

These studies indicate a clear trend in the literature: hybrid RL–SMC controllers retain the robustness inherent to sliding mode control while incorporating adaptive learning capabilities to achieve smoother control performance. This observation supports the effectiveness of the proposed DRL-optimized IISMC, particularly in enhancing adaptability and mitigating chattering effects in AUV motion control.

This study aims to develop and validate a motion control strategy for AUVs operating in nearshore environments for underwater surveying tasks. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

An improved integral sliding mode control (IISMC) scheme is developed by incorporating a nonlinear error-dependent function into the integral term. This design enables the IISMC system to dynamically adjust its control response according to different levels of state errors, thereby enhancing the robustness of the sliding surface structure and allowing rapid correction of trajectory deviations, which improves tracking accuracy. In addition, a modified power reaching law is introduced together with a boundary layer design to ensure smooth control input transitions within the boundary layer and effectively mitigate chattering effects.

A DRL-optimized IISMC (DIISMC) controller is proposed, in which DRL is employed to adaptively tune the sliding surface parameters and boundary layer thickness. This adaptive tuning enables the reaching law to switch between linear and nonlinear forms, allowing the controller to autonomously learn control strategies that are well suited to the dynamic and uncertain conditions of nearshore environments. It is worth noting that the proposed DIISMC framework relies on the structural properties of sliding mode control and bounded disturbance assumptions, rather than on specific mass or geometric parameters. As a result, the method exhibits inherent scale independence and can be applied to different AUV platforms. References [

23,

24] provide theoretical support for the scalability and generalizability of our approach.

The stability and finite-time convergence properties of the proposed control method are theoretically analyzed and rigorously proven. A series of simulation experiments are conducted on AUV trajectory tracking tasks, and performance comparisons are carried out between the proposed DIISMC controller and the baseline IISMC controller. The results demonstrate that the DRL-enhanced controller provides improved trajectory tracking accuracy under nearshore operating conditions.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the kinematic and dynamic modeling of the AUV.

Section 3 describes the proposed IISMC control framework, including the controller design and the DRL-based optimization strategy.

Section 4 presents the simulation and experimental results, with a focus on trajectory tracking performance before and after controller optimization.

Section 5 discusses the issues identified through experimental data analysis and outlines potential directions for future research. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Materials and Methods

Section 2 introduces the coordinate frame definitions adopted for the AUV considered in this study, followed by the corresponding kinematic and dynamic analyses. Based on marine vehicle maneuvering theory, the control objectives are formulated in a mathematical framework to provide a theoretical foundation for the design of the motion control system.

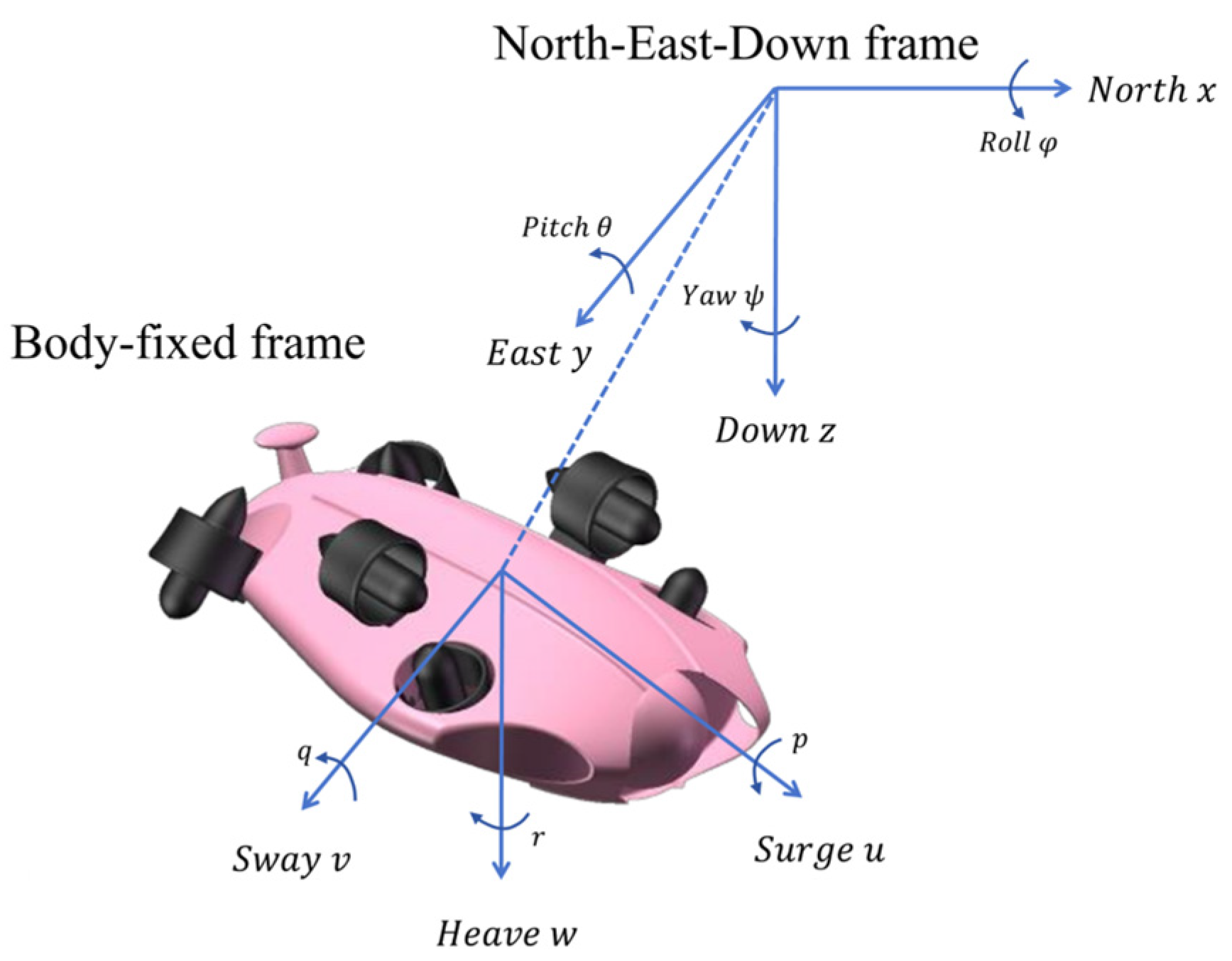

Figure 1 illustrates the overall geometry of the AUV used in this work, together with the definitions of the associated reference coordinate frames.

2.1. Preliminaries

To analyze the motion of the AUV, the North–East–Down (NED) inertial frame and the body-fixed frame are defined, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The vector

represents the position of the AUV in the NED frame, while

denotes its orientation corresponding to the roll, pitch, and yaw angles, respectively. The complete pose of the vehicle is described by the state vector

.

The velocity vector expressed in the body-fixed frame is defined as , which consists of the linear velocity vector and the angular velocity vector .

Remark 1. The AUV used in the experiments is specifically designed for nearshore underwater surveying tasks. Compared with vehicles intended for deep-sea or offshore operations, this AUV operates at relatively low speeds and is subject to simpler hydrodynamic effects. Therefore, only first-order nonlinear hydrodynamic drag is considered in the dynamic model. The corresponding hydrodynamic coefficients are determined following the method described in [

25].

Remark 2. Prior to the experiments, manual calibration was performed to ensure a stable vehicle configuration, resulting in positive buoyancy of the AUV. Under these conditions, coordinate transformations are applied to convert motion information between the NED frame and the body-fixed frame.

Remark 3. In the structural design of the AUV, the center of gravity is defined as with respect to the body-fixed reference origin, while the center of buoyancy is defined as and is located slightly above the center of gravity. This assumption simplifies the dynamic model by eliminating the need to explicitly compute complex restoring force and moment terms.

2.2. Kinematic and Dynamic Modeling

The kinematic model of the AUV considered in this study is defined as:

where

denotes the transformation matrix between the inertial frame and the body-fixed frame. It consists of two components corresponding to the transformations of linear and angular velocities, forming a six-dimensional matrix. Here,

represents a 3 × 3 zero matrix.

is the coordinate transformation matrix for linear velocity, and

is the transformation matrix for angular velocity.

The dynamic model of the AUV is formulated following the standard marine vehicle modeling framework presented in [

26], and is expressed as:

where

denotes the vector of control forces and moments generated by the thrusters and

represents the disturbance vector with unknown structure, including both internal modeling uncertainties and unmeasurable external environmental disturbances.

The inertia matrix consists of the rigid-body inertia matrix and the added mass matrix , such that .

The Coriolis and centripetal matrix accounts for the coupling effects induced by the vehicle motion and is composed of two parts: the rigid-body Coriolis and centripetal matrix , which arises from the rigid-body inertia, and the added-mass Coriolis matrix , which captures the velocity-dependent effects associated with the surrounding fluid. Accordingly, .

The hydrodynamic damping matrix represents the energy dissipation caused by fluid–structure interaction and is composed of linear and nonlinear components. Specifically, the linear damping matrix models low-speed viscous effects, while the nonlinear damping matrix accounts for higher-order drag forces that become dominant at increased velocities. Thus, the total damping matrix is expressed as .

Considering that the AUV employed in this study is laterally symmetric, and that only minor asymmetries exist in the longitudinal and vertical directions, the nonlinear damping matrix is assumed to be diagonal to simplify dynamic modeling and controller design. This assumption implies that the dominant damping contribution in each degree of freedom originates primarily from the corresponding velocity component. Such modeling simplifications have been widely adopted in AUV dynamic modeling and provide satisfactory engineering practicality within acceptable control accuracy margins.

The term represents the hydrostatic restoring forces and moments acting on the AUV, which result from the combined effects of buoyancy and gravitational force . These restoring effects depend on the relative positions of the center of gravity and the center of buoyancy, as well as the roll and pitch angles of the vehicle.

2.3. Thruster Configuration Analysis

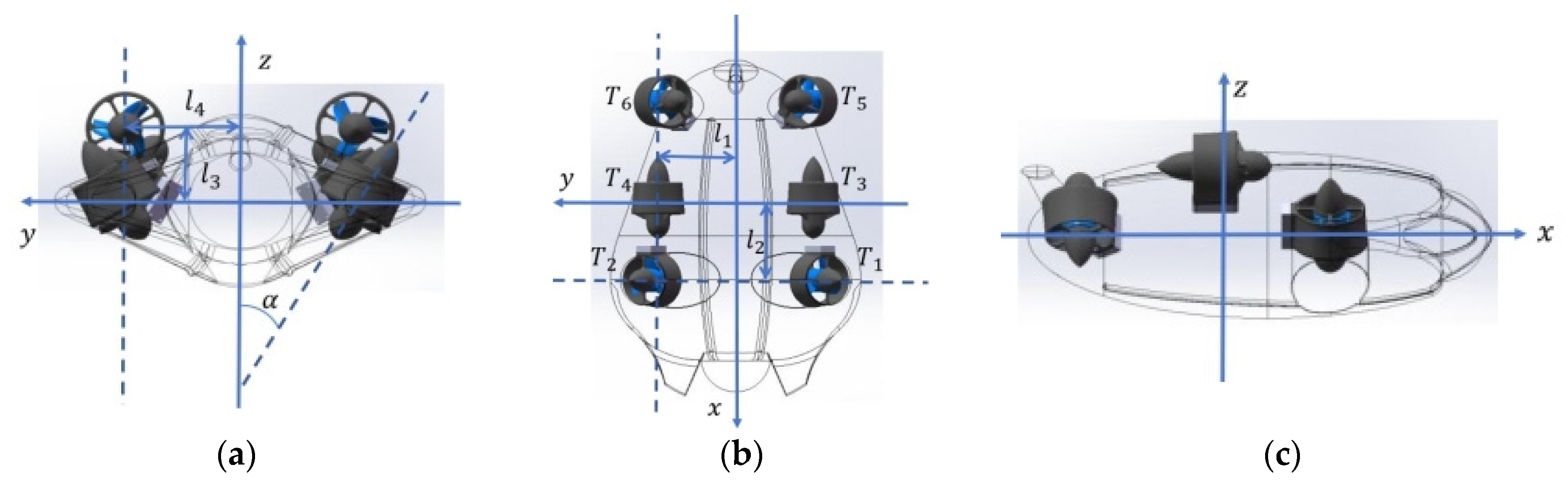

To clearly illustrate the spatial arrangement of the thrusters with respect to the AUV’s body-fixed coordinate system, a three-dimensional isometric projection is employed. The thruster layout and its relationship to the vehicle geometry are further presented through the orthographic views shown in

Figure 2.

The six thrusters, denoted as and , operate cooperatively to achieve full three-dimensional motion of the AUV. In the body-fixed coordinate system, thrusters and are mounted such that their thrust axes are inclined at an angle with respect to the body-frame z-axis. The distances from the centers of these thrusters to the x-axis and y-axis are denoted by and , respectively. Thrusters and are placed symmetrically along the body-frame y-axis at a distance , and their vertical offsets relative to the z-axis are given by .

The overall thrust vector

, which represents the generalized forces and moments acting on the AUV, is distributed among the six thrusters according to the structural configuration. A transformation matrix

is defined to map the control output signal

to the actual thrust vector

. Accordingly, the thrust allocation is expressed as Equation (3):

3. AUV Trajectory Tracking Control Scheme Design

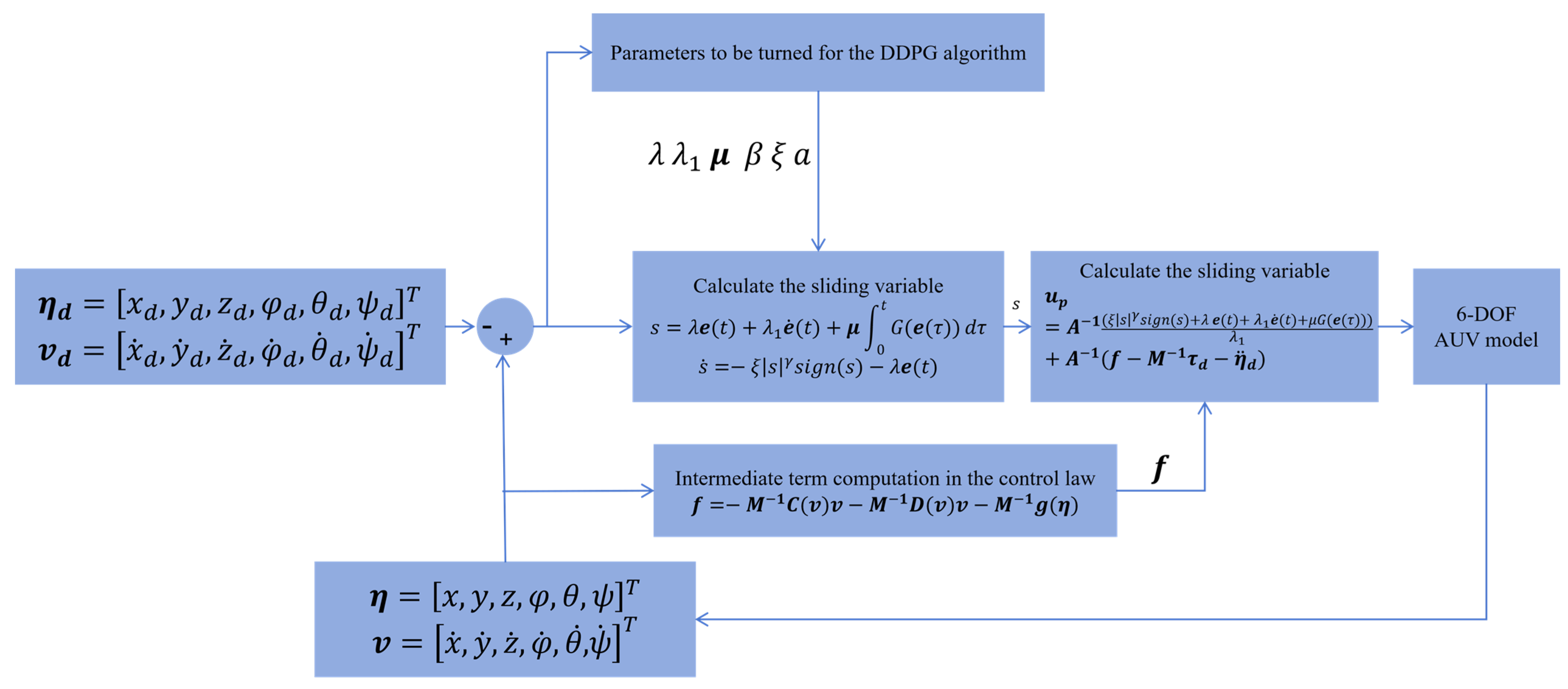

Based on the modeling and analysis presented in the previous sections,

Section 3 introduces the IISMC approach developed for AUV trajectory tracking. The structure and implementation of the IISMC motion controller are described, together with its DRL-optimized extension. In addition, the stability of the proposed control schemes is theoretically analyzed and validated. The overall system architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3.

3.1. Design of the Improved Integral Sliding Mode Control

Before constructing the controller, the following assumptions are made.

Assumption 1. The pitch angle of the AUV is bounded such that in order to avoid potential singularities in the stability analysis.

Assumption 2. The external disturbance signal is assumed to be a bounded and Lipschitz continuous deterministic signal, with its maximum magnitude denoted by , satisfying . In Section 4, the deterministic disturbance is constructed using sinusoidal functions over a finite experimental time horizon and does not involve any stochastic components, thereby ensuring boundedness. Moreover, similar assumptions have been widely adopted in related studies [27,28,29], implying that the disturbance does not exhibit abrupt variations. This formulation facilitates the application of Lyapunov-based theoretical tools for the subsequent stability analysis. To address the AUV trajectory tracking problem, the sliding surface and reaching law of the sliding mode controller are designed. First, a first-order linear sliding surface

is constructed, incorporating the tracking error

and its time derivative

. Here,

and

denote the desired position and velocity profiles, respectively, provided by a predefined reference trajectory. Both are represented as six-dimensional column vectors. For the sake of simplifying the theoretical analysis, all six degrees of freedom (6-DOFs) are treated in a coupled manner, and unified variables

and

are used instead of matrix-form expressions. The sliding surface is defined as Equation (4):

where the tracking error terms are given by:

The dynamic model described in Equation (2) can be rewritten as Equation (6):

By introducing the substitution variables

and

, the tracking error dynamics in Equation (5) can be reformulated as Equation (7):

In this study, the sliding surface is designed as Equation (8):

Compared with conventional ISMC, the proposed control law demonstrates improvements in both structural design and control performance. Traditional ISMC typically incorporates the integral of the error into a first-order linear sliding surface to eliminate steady-state error. However, its tuning flexibility is limited because it usually relies on a single proportional factor, and the integral term is often designed in a linear or signum form, which may lead to chattering and integral saturation.

In contrast, the proposed sliding surface retains the classical first-order linear structure while introducing additional flexibility through the parameters and , allowing more effective adjustment of the system’s responsiveness to state errors. To further compensate for steady-state error, the method incorporates the integral term , which accumulates over time when non-zero errors persist, continuously enhancing the controller output and driving the system state toward the desired trajectory.

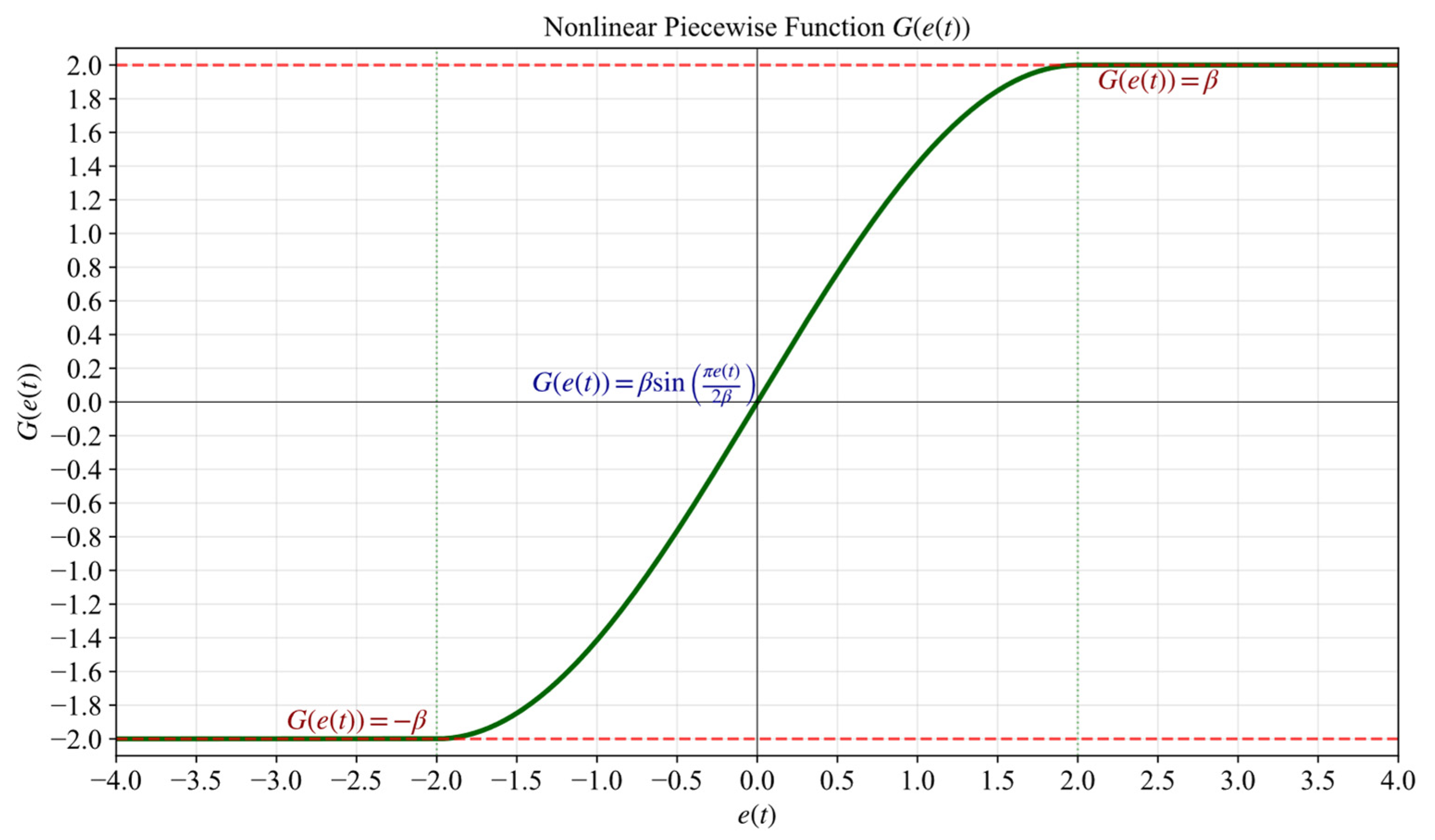

Unlike conventional linear integral functions, the nonlinear error function

is designed as a piecewise-continuous sinusoidal function: when the absolute error is within a small threshold

, the function takes the smooth form

, effectively suppressing chattering; when the error exceeds this range, the function saturates to

, ensuring both fast convergence and robustness while avoiding integral divergence. The functional profile of

is illustrated in

Figure 4. Overall, the proposed method provides advantages over conventional ISMC in terms of steady-state error elimination, chattering suppression, and enhanced tuning flexibility.

This structure ensures both nonlinear sensitivity and bounded control output. Specifically, it provides strong corrective action when the tracking error is large and gradually reduces control intensity as the error diminishes, thereby suppressing chattering and enhancing robustness. The function is defined as:

In Equation , the linear gain parameters and are design variables, while the integral gain is a diagonal positive-definite matrix. The threshold parameter is also subject to controller design.

The time derivative of the sliding surface is expressed as:

By substituting

with

and defining the nonlinear vector

. Equation (10) can be rewritten as:

The reaching law adopted in this study is designed as:

Compared with conventional reaching laws, such as constant-rate, exponential, and power-based schemes, the proposed method directly incorporates the tracking error into the reaching law. This enables direct regulation of the tracking error during the reaching phase, enhancing convergence speed while maintaining effective control responsiveness in the terminal stage. Furthermore, it reduces abrupt transitions caused by high-frequency switching, thereby improving the system’s robustness and smoothness under disturbances and uncertainties.

The nonlinear gain is a tunable design parameter that determines the control intensity in regions with large errors. The exponent d defines the degree of nonlinearity in the reaching law and is implemented in a piecewise manner. When the sliding surface approaches zero, a lower exponent is chosen to ensure a smoother control input, as .

To balance control speed and robustness, the exponent

is typically selected within the range

, allowing exploration of the effect of the power term on the performance of the modified reaching law. The structure of the reaching law is adaptively switched based on the boundary layer thickness to achieve an optimal degree of linearity. The exponent

is treated as a design parameter, defined as Equation (13):

By combining Equations

,

and

, the simplified thrust calculation formula is obtained as Equation

. Letting

, the final expression for the thrust control input is given as Equation

.

3.2. Stability Analysis

To evaluate the stability of the IISMC controller, a theoretical analysis is conducted based on Lyapunov stability theory. A Lyapunov function

and its time derivative

are defined as follows:

To ensure finite-time stability, the following condition must be satisfied:

where

is a positive constant guaranteeing convergence to the equilibrium within a finite time. The second term in Equation

contains the tracking error. To handle this term, the following assumption is introduced:

Assumption 3. In the vicinity of the sliding surface, there exists a constant such that: . Applying Young’s inequality yields:

By introducing the auxiliary parameter

and letting

, the inequality can be simplified as:

This conservative estimate replaces the actual error with its upper bound, ensuring that worst-case stability conditions are met. Consequently, when

, it suffices that:

During the transient phase, when

, the following condition must hold:

Thus, the Lyapunov condition is satisfied when

exceeds a certain threshold

, defined as:

This ensures that the system state reaches the sliding surface in finite time. According to finite-time stability theory [

30,

31,

32], the upper bound on the convergence time

is given by:

Therefore, the convergence time is finite and depends on the initial sliding variable

and the nonlinearity exponent

. From Equations

and

, it follows that

. Considering the relation

, separating variables and integrating yields:

where

is an integration constant. Taking the exponential form gives

. Since

is a constant and

,

decreases monotonically over time and asymptotically approaches zero. Therefore, the sliding surface converges to zero, which ensures that the system state reaches and remains on the sliding manifold, completing the proof of finite-time stability.

It should be noted that this Lyapunov-based stability analysis assumes fixed controller parameters, while the proposed DIISMC framework incorporates online parameter adaptation via DRL. This means that the presented stability analysis does not directly account for time-varying parameters.

In practice, the learned parameters are constrained within predefined bounds, and their variation is relatively slow compared to the system dynamics. Therefore, the stability analysis can be interpreted as guaranteeing local stability for frozen parameter values, which is a standard qualitative assumption in adaptive and learning-based control systems. Reference [

33] provides support for this approach, demonstrating that Lyapunov theory can be effectively applied to analyze the stability of controllers with bounded, slowly varying, time-dependent parameters. Additionally, Reference [

34] investigates adaptive sliding mode control for nonlinear systems with time-varying parameters and bounded disturbances, applying the Lyapunov method to perform a stability analysis and discussing how local stability can be guaranteed when parameter variations are slow. These interpretations highlight a limitation in the current theoretical analysis, while still providing valuable insight into the closed-loop stability behavior under bounded and slowly varying adaptations. These interpretations highlight a limitation in the current theoretical analysis, while still providing valuable insight into the closed-loop stability behavior under bounded and slowly varying adaptations.

This study also employs the traditional SMC method as a benchmark for comparison. Compared to IISMC, the traditional SMC lacks the integral term, and certain parameters used in the IISMC approach are not involved in the SMC framework. Due to its simpler structure, the stability analysis for SMC is based on the classical literature on SMC [

35], which is presented here without the need for a detailed mathematical derivation within this paper.

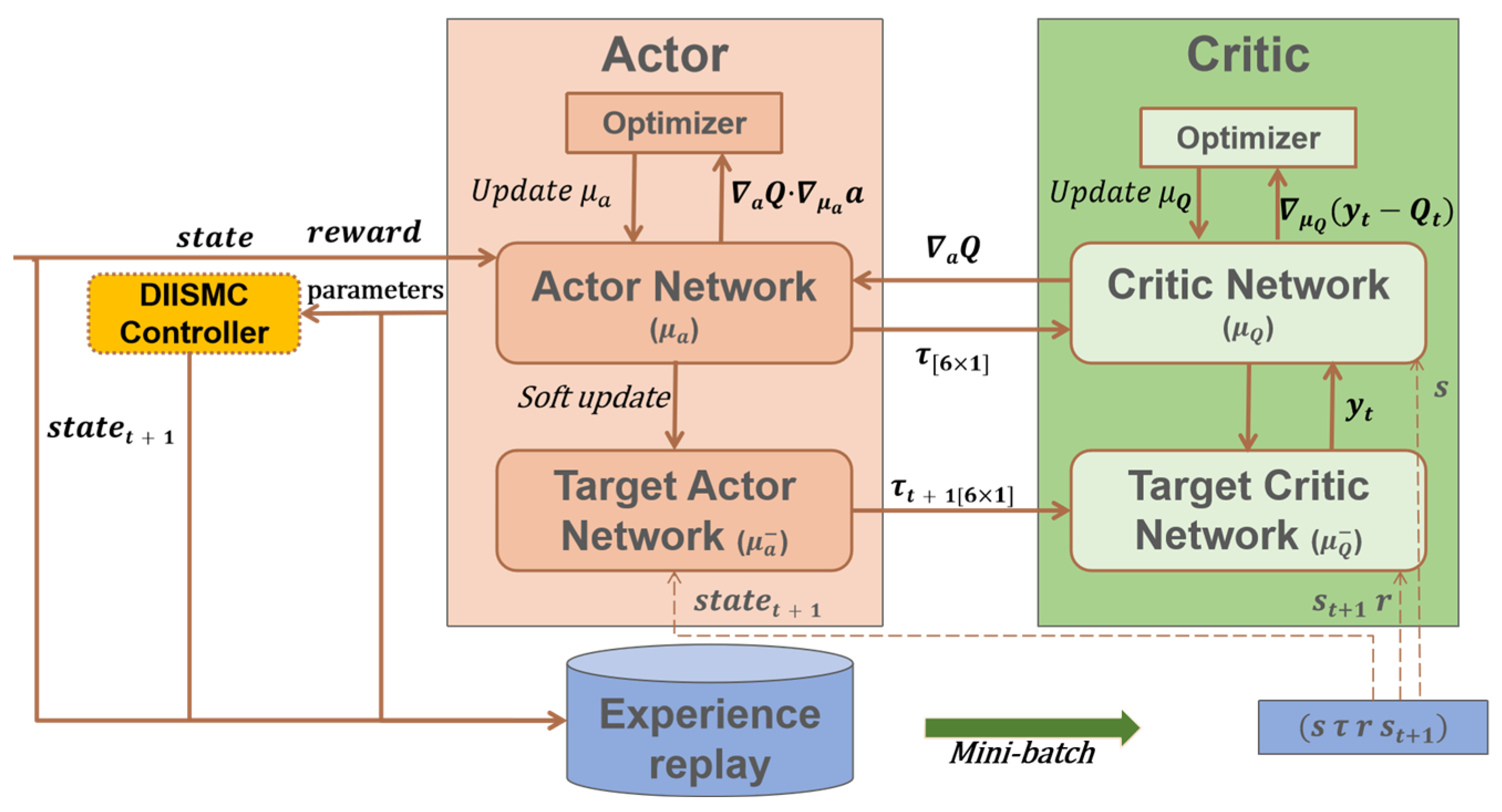

3.3. IISMC Motion Controller Optimized by Deep Reinforcement Learning

To optimize the tunable parameters in the IISMC algorithm, this study employs a DRL framework. The DRL mechanism is leveraged to identify parameter configurations that best adapt to the operating environment, thereby ensuring both trajectory tracking accuracy and robustness for the AUV.

Since the AUV operates in a continuous action space, value-based DRL methods typically require discretization of the action space, which reduces control precision. In contrast, policy-based DRL methods rely on stochastic policies, which often result in slow convergence and high parameter variance. Consequently, both approaches are suboptimal for systems such as AUVs, which demand fast response, high stability, and precise control.

To overcome these limitations, the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm is adopted in this study. DDPG combines the advantages of value-based and policy-based methods, making it suitable for efficient training in continuous action spaces. The principle of the algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 5 and described in [

36].

Both the actor and critic networks in the DDPG framework are implemented as fully connected feedforward neural networks (MLPs). The actor network comprises two hidden layers with 128 and 64 neurons, respectively, employing ReLU activation functions, and outputs continuous control parameters corresponding to the sliding surface and reaching law coefficients. The critic network has a similar architecture, with the state and action inputs concatenated at the second hidden layer. Other related parameters are summarized in

Table 1.

By directly mapping system states to continuous action vectors, the DDPG algorithm eliminates the need for discretizing the action space, thereby preserving control precision. To enhance training stability, target networks are introduced to mitigate instabilities arising from simultaneous updates of the policy and value networks. Furthermore, the deterministic policy structure of DDPG aligns naturally with the control logic of sliding mode control, ensuring continuity of control inputs and maintaining system stability. Collectively, these characteristics enhance both the practical applicability and robustness of the proposed DRL-optimized IISMC motion controller.

In this framework, the current AUV state information and the reward function evaluation are fed into the policy network to generate control signals, which are subsequently evaluated by the critic network to assess their tracking performance. The target policy network maps the next control signal based on the subsequent state sampled from the replay buffer, while the target critic network provides the corresponding evaluation value. The difference between evaluation values at two consecutive time steps is used to perform gradient descent, thereby updating the weights of both the critic and policy networks. At fixed intervals, the weights of the target networks are softly updated. Ultimately, the policy network outputs parameterized control signals, enabling an adaptive control process.

It should be noted that the deep reinforcement learning module is trained offline prior to deployment. During online operation, the controller performs only a forward pass through the trained policy network to update a small set of sliding mode parameters, while the IISMC law itself remains analytically defined. Consequently, the online computational burden is limited, making the approach suitable for real-time implementation on embedded processors commonly.

3.4. Network Configuration and Reward Function Design

A precise definition of the state input vector

is crucial for the performance of the DDPG algorithm. In the context of AUV motion control, this vector should comprehensively represent the vehicle’s pose and velocity information. In this study, the state input

is constructed based on tracking errors and their temporal evolution, including the current tracking error

, its time derivative

, as well as historical error trends. Specifically, the integral of the tracking error over a short time window

and the integral of its derivative

, together with the tracking error and its derivative at the previous time step,

and

, are included to capture both the magnitude and the variation trend of the state deviation. Each of these components is represented as a six-dimensional row vector, resulting in the state vector formulation shown in Equation

:

The reward function

is designed as a piecewise function that evaluates the tracking performance across all 12 dimensions (pose errors and velocity errors) at each time step

t, as defined in Equation

:

Here, denotes the error of the -th component at the corresponding time step , with ranging from 1 to 12. The parameter defines the error threshold, determines the penalty strength for large errors, and is a small positive constant to prevent singularities. The parameter acts as a time weight to balance smoothness during the initial training phase and responsiveness during later stages. is a binary termination flag, taking values of 1 or 0. When , at least one component of the pose or velocity error exceeds the limit, requiring the current training episode to be terminated and restarted. When , all errors are within acceptable limits, and training continues until the episode is completed. A severe penalty is applied in failure cases.

This reward structure combines positive reinforcement and penalties for erroneous exploration, guiding the agent to quickly learn the desired behavior and thereby accelerating convergence during training. The incorporation of multiple reference factors further enhances the stability and robustness of policy learning.

4. Simulation

The algorithm in this study is currently implemented using MATLAB and Simulink (version R2023a) for simulation and verification. To validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed IISMC method and its DDPG-based optimization, a series of simulations were conducted. During these experiments, the algorithm runs on a high-performance computer equipped with an Intel i7 processor, 16 GB of RAM, and a 256 GB SSD storage. This configuration is sufficient to meet the computational requirements of the algorithm, particularly when handling complex control tasks, ensuring stable computational performance. The simulation sampling time is set as , with each training episode lasting , and a total of 200 training episodes. The performance of the proposed controller is compared with that of the traditional SMC method based on a constant-rate reaching law. Furthermore, the improvement resulting from the integration of DDPG with IISMC (hereafter referred to as DIISMC) is evaluated.

The reference trajectory is a three-dimensional spiral with a period of

, defined as Equation (27):

The external disturbances

are generated as a combination of sinusoidal functions with different amplitudes and frequencies, along with constant bias terms. In addition, a Gaussian noise term is superimposed to emulate sensor noise, further testing the robustness of the control system. It should be noted that this noise is not part of the theoretical disturbance model and is introduced solely for simulation purposes. Since no probabilistic modeling is involved, the inclusion of this noise does not affect the validity of the system stability analysis. The disturbance vector is defined as Equation (28):

The physical parameters of the AUV used in the simulations are summarized in

Table 2. The table includes key vehicle characteristics such as mass

, displaced volume

, and density

, as well as the geometric dimensions (length, width, and height). The positions of the center of gravity

and center of buoyancy

are defined relative to the body-fixed frame origin, simplifying the calculation of restoring forces. Moments and products of inertia

describe the rotational dynamics of the vehicle. Hydrodynamic effects are modeled using added mass coefficients

, linear damping coefficients

and nonlinear damping coefficients

. These parameters are adopted from conventional marine vehicle modeling methods and provide a reasonable representation of the dynamics for AUV operations.

Table 3 lists the parameter values used in the experiments along with the corresponding ranges for the DIISMC method. These values were determined based on relevant literature and an iterative simulation-based tuning procedure. To ensure fair comparison, parameters with identical physical meanings in the SMC and IISMC controllers were assigned the same values under identical experimental conditions.

Some parameters are not applicable to the simpler SMC formulation and are therefore marked as “

” in

Table 3. All SMC and IISMC parameters were chosen within the predefined ranges of the DIISMC method to maintain consistency.

Over fifty tuning trials were conducted to identify parameter sets that provided favorable control performance. The values presented in

Table 3 represent one representative set from these trials. Additional comparative simulations were then performed using alternative parameter values and combinations to comprehensively evaluate the performance of each control method.

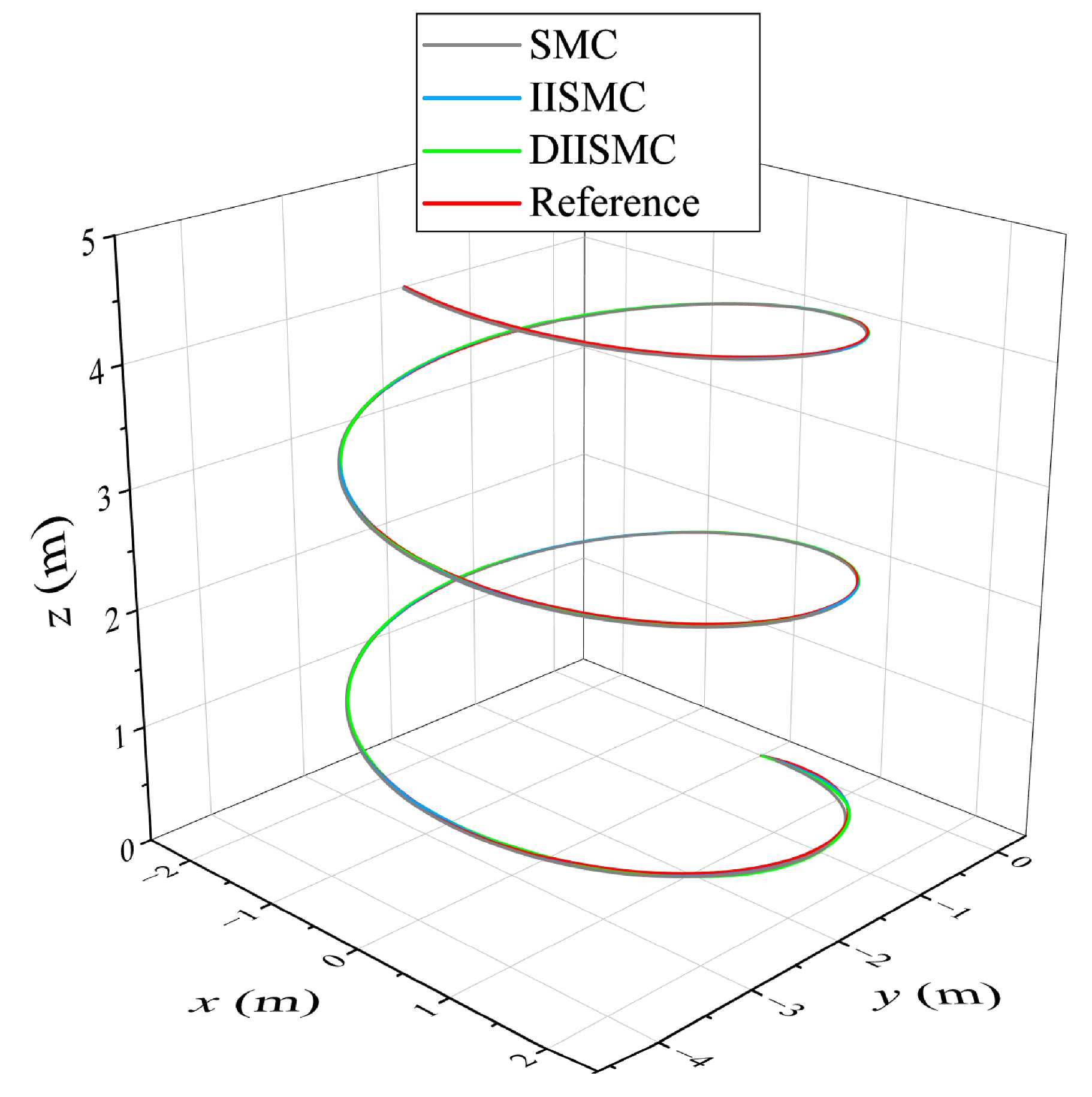

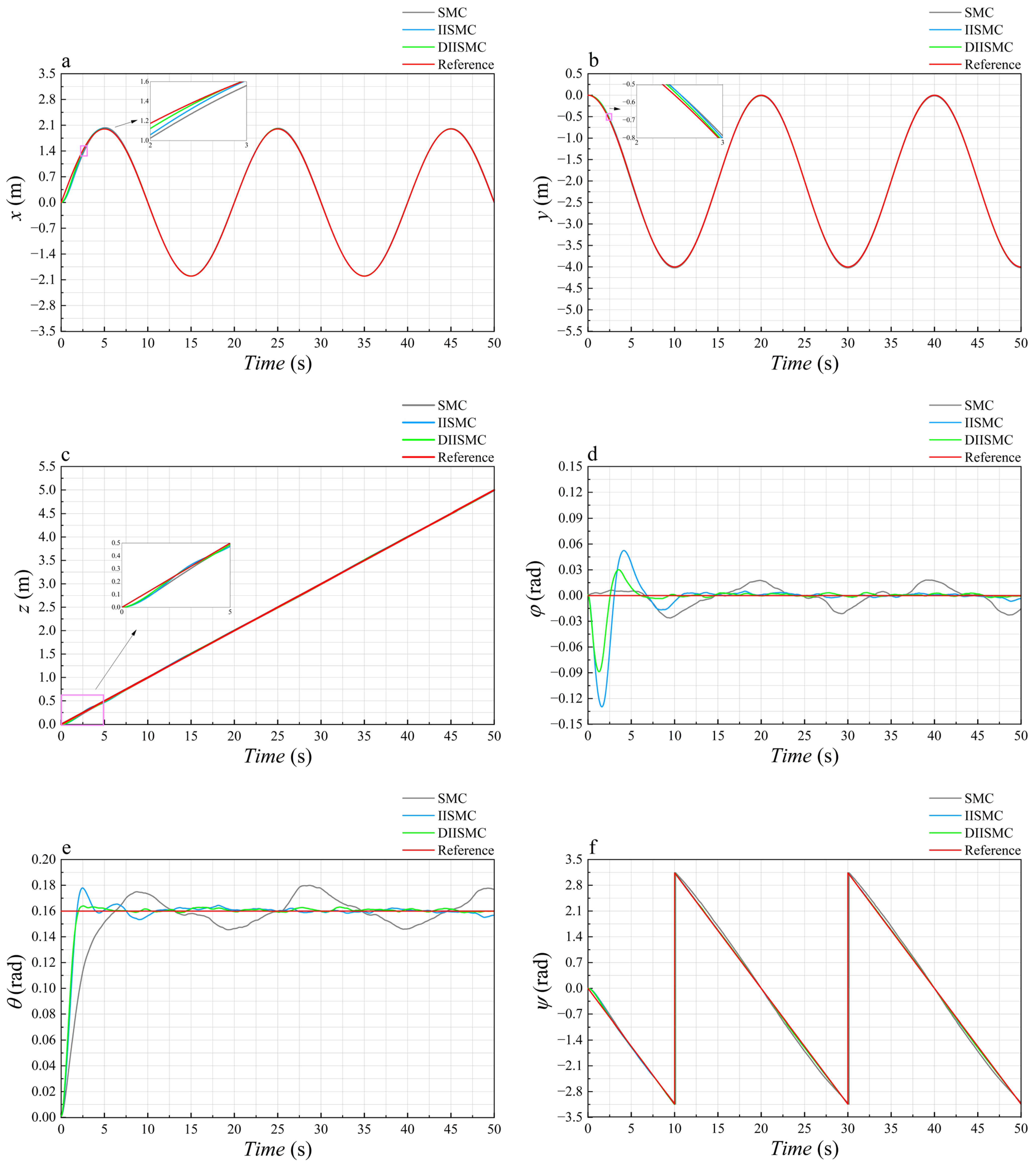

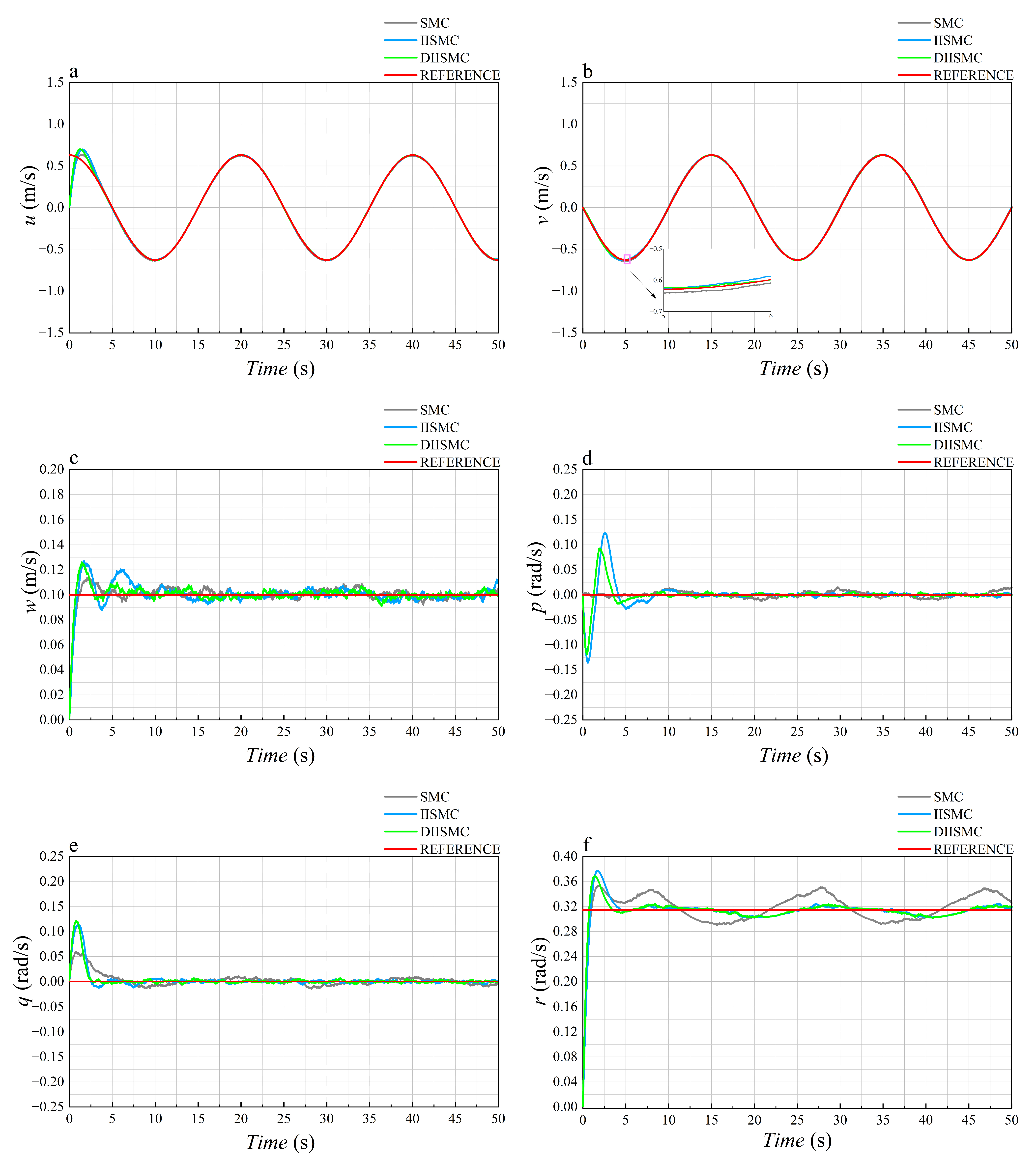

The trajectory tracking results are presented in

Figure 6. The black curve represents the performance of the traditional SMC controller, the blue curve corresponds to the IISMC method, and the green curve illustrates the DDPG-optimized IISMC (DIISMC) controller. The desired helical trajectory is shown in red for reference. The detailed tracking performance in terms of position and velocity, as well as the corresponding tracking errors, are depicted in

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

An analysis of

Figure 7 reveals that all three controllers successfully achieve trajectory tracking in the position domain, with DIISMC and IISMC showing improved tracking accuracy compared to SMC. Considering that the experimental workspace radius is approximately ten times larger than the AUV size, this improvement is expected to translate into satisfactory tracking performance in practical scenarios. Regarding attitude tracking, DIISMC and IISMC exhibit smaller oscillation ranges and faster convergence than SMC, achieving steady-state operation within approximately half a cycle. Moreover, DIISMC demonstrates a noticeable reduction in overshoot compared to IISMC, indicating enhanced pose tracking performance while maintaining stability.

The Analysis of the tracking performance of linear and angular velocities in

Figure 8 shows that DIISMC and IISMC exhibit slightly larger amplitude variations compared to SMC. However, after convergence, there is no significant difference in the oscillation range among the three methods. The relationship between these results and velocity tracking performance will be explored in future studies.

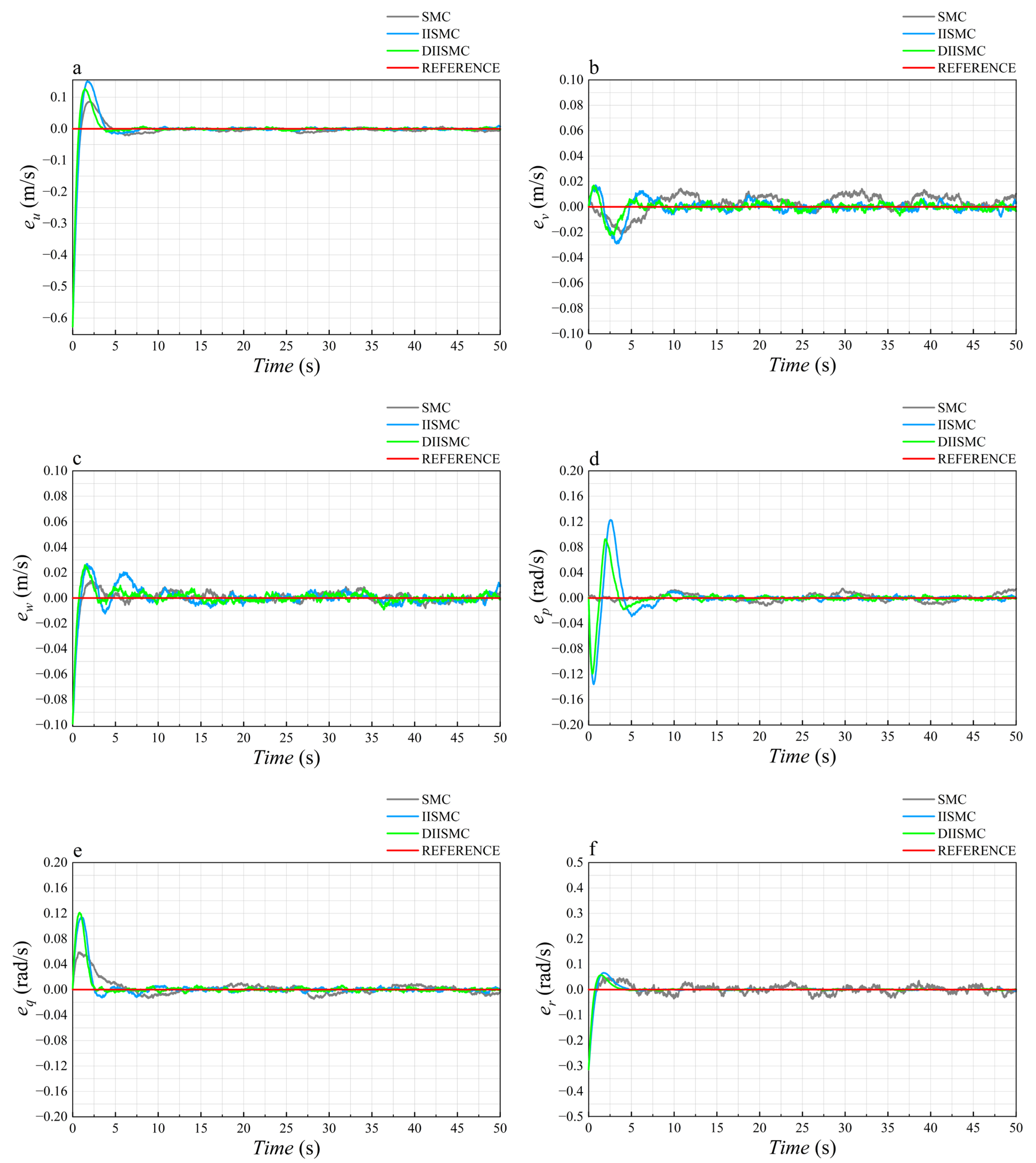

Additionally, the analysis of the error plots in

Figure 9 reveals that DIISMC achieves the fastest convergence and the smallest steady-state errors among the three controllers. Particularly, in

Figure 9f, the yaw angle tracking error, SMC and IISMC show varying degrees of lag, while DIISMC does not exhibit this issue, highlighting its rapid response advantage. However, for the velocity errors presented in

Figure 10, DIISMC does not show significant improvements similar to pose tracking, which will be a key focus of our future work.

Table 4 presents the statistical indicators of tracking performance, including the standard deviation and boundary limits of the tracking errors, thereby quantifying the improvements or deteriorations across the different control methods. A detailed analysis of specific motion dimensions reveals that, compared with the traditional SMC, both IISMC and DIISMC achieve enhanced forward and lateral position tracking. Specifically, the upper bound of the forward position error is reduced to 60.0% and 25.0% of the corresponding SMC value for IISMC and DIISMC, respectively, while the lateral position error upper bound decreases to 89.7% and 66.7%, These results indicate that both the proposed IISMC and the DIISMC methods effectively constrain the range of tracking deviations, demonstrating superior control performance.

Analysis of the error standard deviations indicates that, for IISMC, the standard deviations of forward and lateral position errors are reduced by 9.3% and 46.2%, respectively. For DIISMC, after autonomous parameter adaptation, the standard deviations of pose tracking errors decrease by an average of 35.5%, while those of velocity tracking are reduced by an average of 2.1%. These results demonstrate that the proposed controller effectively limits the frequency of error fluctuations, thereby enhancing overall system stability during the control process. Notably, as observed in

Figure 7f and

Figure 8f, DIISMC successfully mitigates the control lag in yaw regulation, achieving a favorable balance among control speed, accuracy, and stability. Additionally, by extracting the twelve sets of error data shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, and calculating the standard deviations of the control performance errors for both DIISMC and SMC, it is found that DIISMC provides an 18.8% performance improvement over SMC on average. Further, the local zoom-in views in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the process by which the actual trajectory approaches the desired trajectory at specific moments.

Based on the observations from

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the DIISMC method effectively constrains both the error standard deviation and the error bounds. Under steady-state conditions, the fluctuation amplitude is well-controlled, and the system maintains accurate trajectory tracking even in the presence of external disturbances. Overall, the proposed method shows improvements in trajectory tracking accuracy, disturbance rejection, and system robustness, providing a solid foundation for further experimental validation and potential application in marine environments. However, as indicated by the data in

Table 4, IISMC does not outperform traditional SMC in all dimensions. In some cases, the tracking accuracy does not exceed that of SMC, and certain error bounds are not sufficiently suppressed. These limitations will be further analyzed and discussed in

Section 5.