A Hybrid LSTM-UDP Model for Real-Time Motion Prediction and Transmission of a 10,000-TEU Container Ship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Hydrodynamic Methods in the Framework of Potential Flow Theory

2.2. Basic Concepts of the LSTM Model

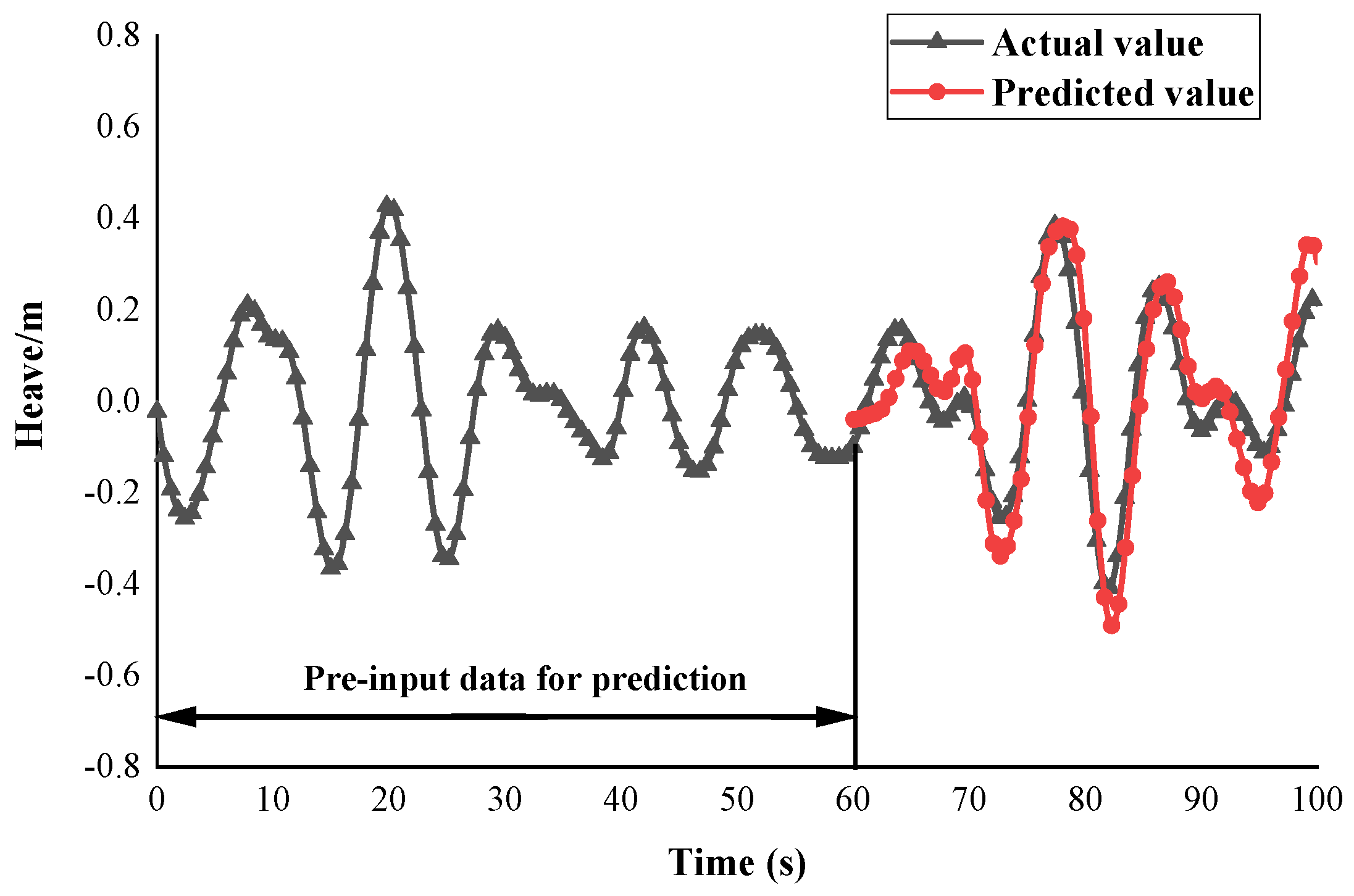

2.3. Principle of Prediction of Ship Motion Using the LSTM Model

2.4. Set-Up and Training of Prediction Model

2.4.1. Dataset Description and Preprocessing

2.4.2. Model Development and Optimization

2.4.3. Model Deployment Preparation

3. Data Transmission Using the UDP Protocol

3.1. UDP Communication Initialization

3.2. Data Update and Accumulation

3.3. Normalization of Prediction Set Data

3.4. Model Prediction and Data Processing Workflow

3.5. Real-Time Data Transmission and Archiving

4. Result Presentation and Discussion

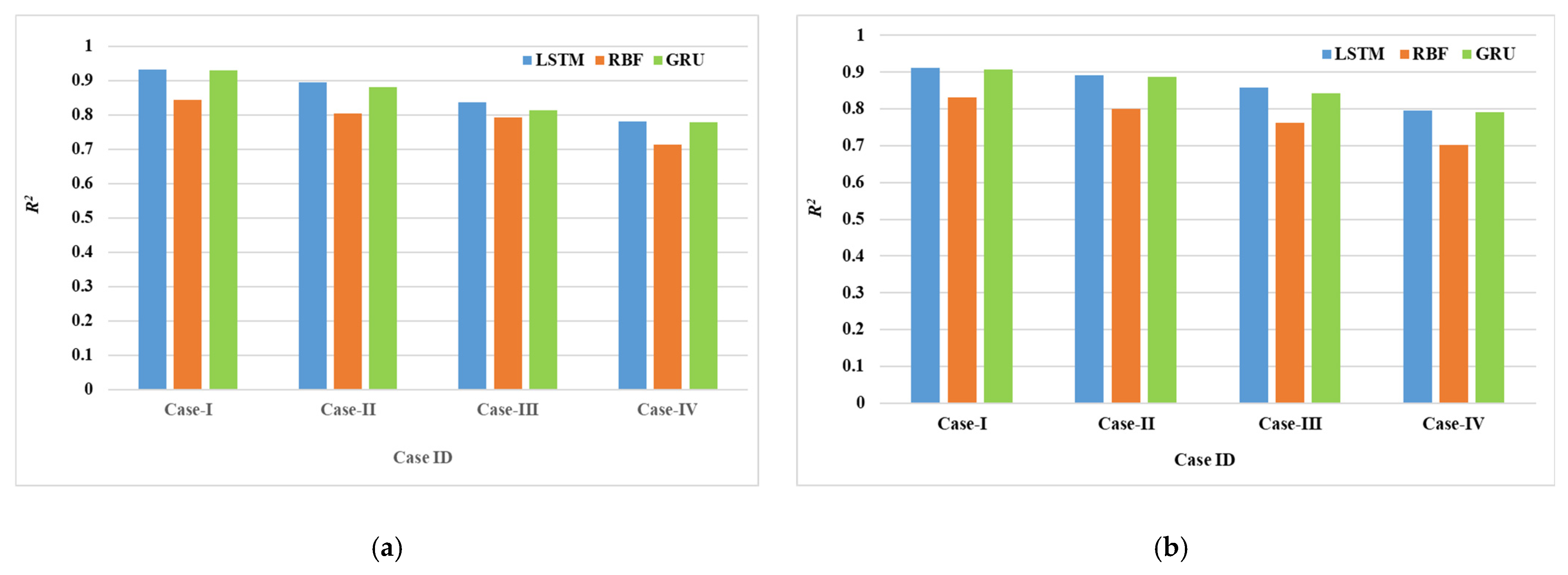

4.1. Comparison Between the Proposed Model and Other Models

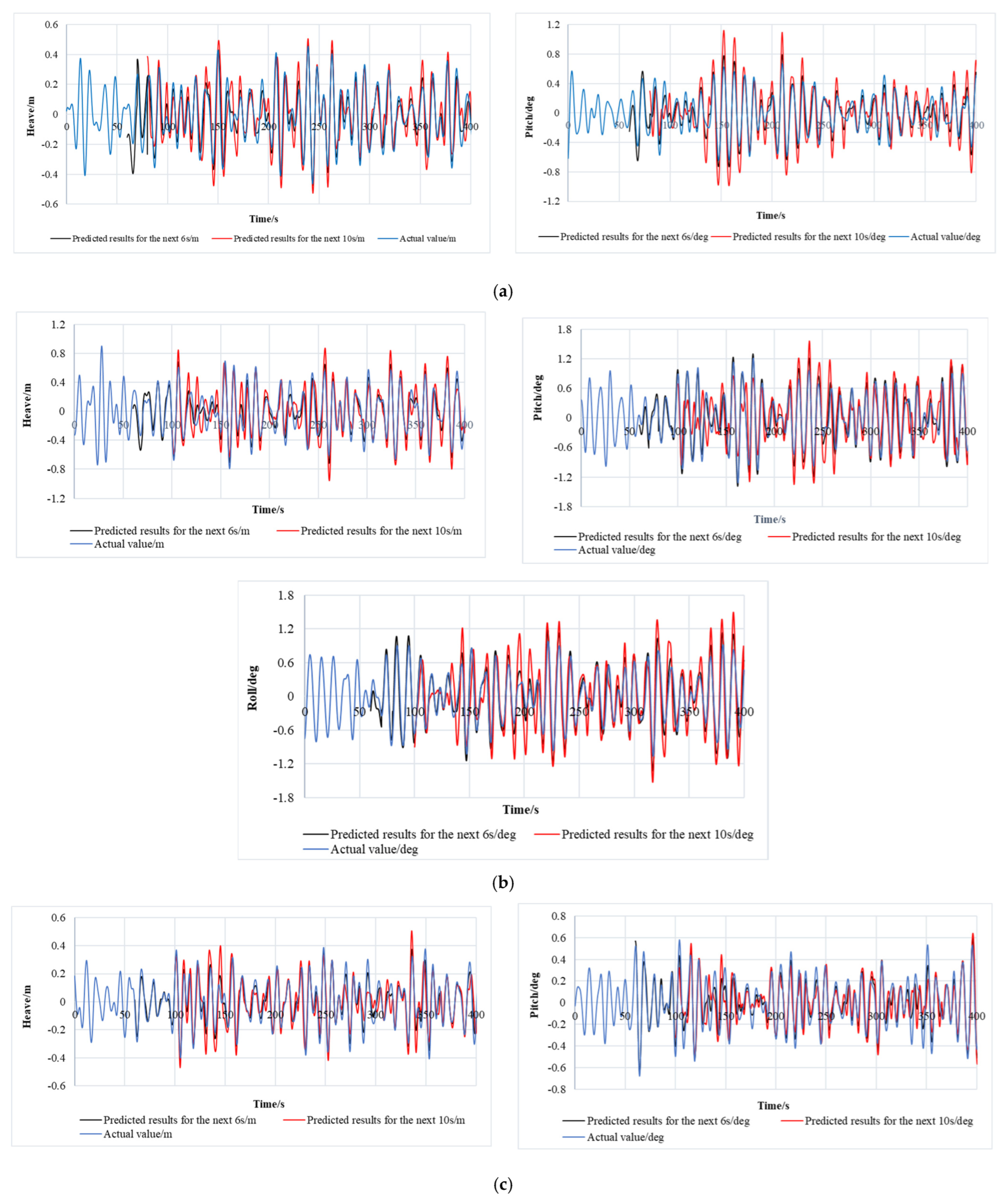

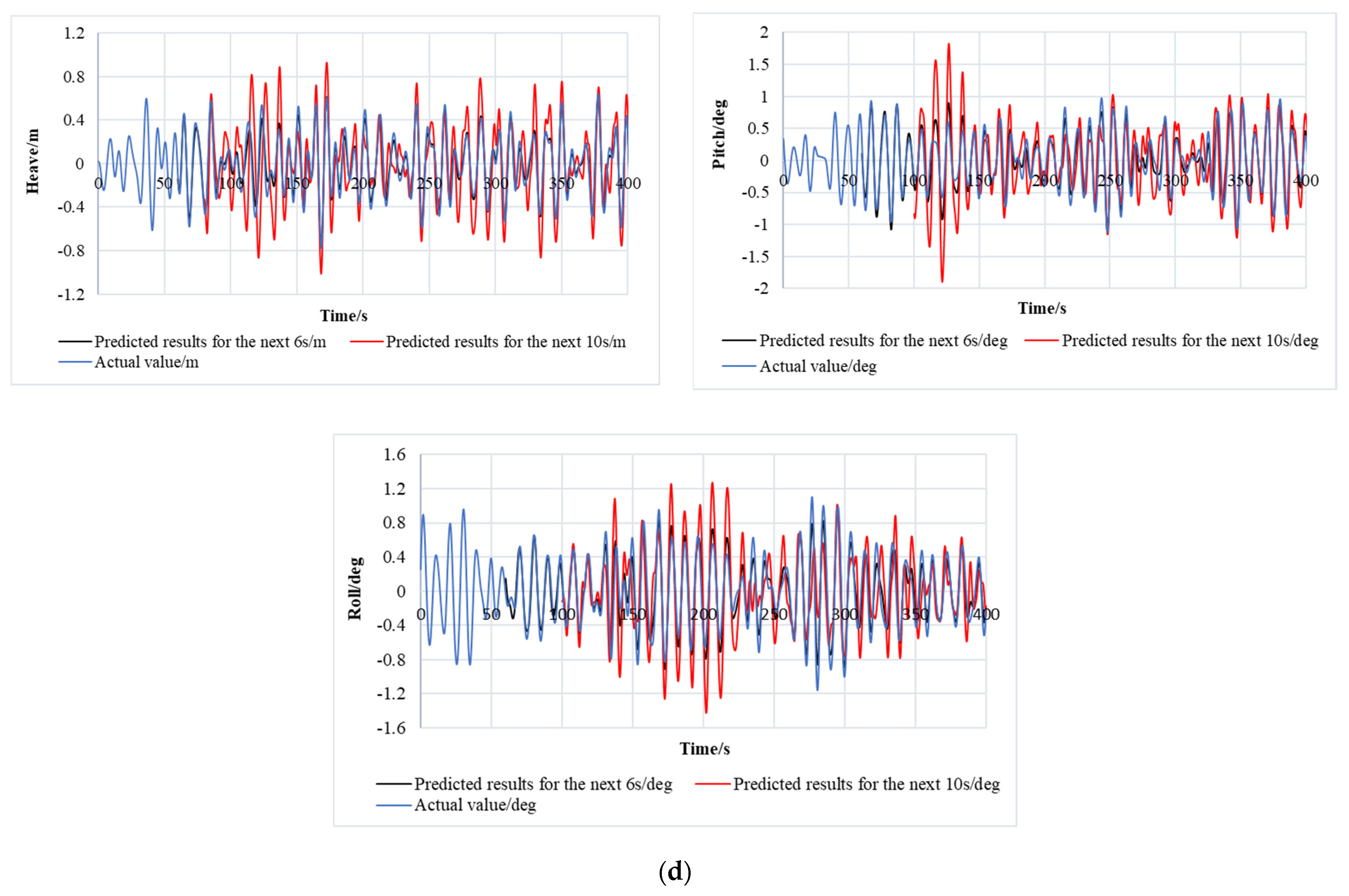

4.2. Comparison Among Multi-Time Scale-Predicted Results

5. Conclusions

- To evaluate the performance in predicting future motions of the ship, a comparative analysis is carried out between the proposed method and two other neural network models. The results show that the close correspondence between the predicted and actual values validates the efficacy of deep learning, specifically the gated architecture of LSTM networks, in modeling complex nonlinear temporal dynamics, thereby establishing its suitability for ship motion prediction. Moreover, for the proposed method, the training data typically originate from motion records of real-world ships.

- Real-time prediction across multiple time scales was implemented for ship motions in random waves. A key finding is the certain correspondence between the overall trends of the predictions and the actual recorded results. Besides, the prediction accuracy will decrease significantly as the predictable time scale increases. The decrease in accuracy is not only reflected in the overestimation or underestimation of peak value, but also in the frequency dislocation of the time series.

- The primary limitation of the present model lies in the fixed format of input data. The input dimensions must align with the model’s initialization parameters, and the training process depends heavily on GPU acceleration. Furthermore, the CUDA version must be compatible with PyTorch; otherwise, the system defaults to CPU processing, which significantly impedes training speed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, X. Displacement motion prediction of a landing deck for recovery operations of rotary UAVs. Int. J. Contr. Autom. Syst. 2013, 11, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.M.; Duan, W.Y.; Han, Y.; Chen, Y. A review of short-term prediction techniques for ship motions in seaway. J. Ship Mech. 2014, 18, 1534–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Ji, X.; Gui, H.B. Real-Time Prediction of Multi-Degree-of-Freedom Ship Motion and Resting Periods Using LSTM Networks. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Cong, W.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J. Harnessing LSTM for Nonlinear Ship Deck Motion Prediction in UAV Autonomous Landing Amidst High Sea States. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Nonlinear Dynamics, Vibration and Control, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 4–6 December 2023; pp. 820–830. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Lu, T.; Huang, J.; He, X.; Sun, X. An Improved VMD–EEMD–LSTM Time Series Hybrid Prediction Model for Sea Surface Height Derived from Satellite Altimetry Data. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Lu, W.; Li, X. Probabilistic prediction of the heave motions of a semi-submersible by a deep learning model. Ocean. Eng. 2022, 247, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A Bayesian extension of the minimum AIC procedure Autoregressive model fitting. Biometrika 1979, 66, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumori, I.R. Real time prediction of ship response to ocean waves using time series analysis. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 81, Boston, MA, USA, 16–18 September 1981; pp. 1082–1089. [Google Scholar]

- Triantafyllou, M.; Athans, M. Real time estimation of the heaving and pitching motions of a ship using a Kalman filter. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 81, Boston, MA, USA, 16–18 September 1981; pp. 1090–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, C.; Cunha, C. Bivariate autoregressive models for the time series of significant wave height and mean period. Coast. Eng. 2000, 40, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, J.P. Machine learning for naval architecture, ocean and marine engineering. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2023, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateus, B.C.; Mendes, M.; Farinha, J.T.; Assis, R.; Cardoso, A.M. Comparing LSTM and GRU Models to Predict the Condition of a Pulp Paper Press. Energies 2021, 14, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buestán-Andrade, P.A.; Santos, M.; Sierra-García, J.E.; Pazmiño-Piedra, J.P. Comparison of LSTM, GRU and Transformer Neural Network Architecture for Prediction of Wind Turbine Variables. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Soft Computing Models in Industrial and Environmental Applications, Salamanca, Spain, 5–7 September 2023; pp. 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gers, F.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to Forget: Continual Prediction with LSTM. Neural Comput. 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, R.; Price, W. On the relationship between “dry modes” and “wet modes” in the theory of ship response. J. Sound Vib. 1976, 45, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, R.; Price, W. Hydroelasticity of Ships; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kolway, H.G.; Coumatos, L.M.J. State-of-the-Art in Non-Aviation Ship Helicopter Operations. Nav. Eng. J. 1975, 87, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, J.L. Flight Deck Motion System (FDMS): Operating Concepts and System Description; Defence R&D Canada: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.L.; Huang, X.Y.; Li, K.; Fu, M.L.; Luo, Y.; Chen, M. Multi-step motion attitude prediction method of USV based on CNN-GRU model. Ship Sci. Technol. 2024, 46, 132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasimehr, H.; Paki, R. Improving time series forecasting using LSTM and attention models. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2022, 13, 673–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Singh, B. A Comparative Study of Loss Functions for Deep Neural Networks in Time Series Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data, Machine Learning, and Applications, Silchar, India, 19–20 December 2021; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Du, M.C.; Ji, X.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhao, W.D. Prediction of Ship Future Motions at Different Predictable Time Scales for Shipboard Helicopter Landing in Regular and Irregular Waves. Ships Offshore Struct. 2024, 19, 2172–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Gui, H.B.; Dong, P.S. Nonlinear time-domain hydroelastic analysis for a container ship in regular and irregular head waves by the Rankine panel method. Ships Offshore Struct. 2019, 14, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Library ID | The Name of the Library |

|---|---|

| 1 | File and Path Operations Libraries

|

| 2 | Data Serialization and Network Communication Libraries

|

| 3 | Iterator Utilities Library

|

| 4 | PyTorch Deep Learning Libraries

|

| 5 | Numerical Computing and Data Manipulation Libraries

|

| 6 | Random Number and Excel I/O Libraries

|

| Case ID | Forward Speed U (knot) | Significant Wave Height H1/3 (m) | Spectral Peak Period TZ (s) | Heading Angle β (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-I | 10 | 6 | 9.5 | 0 |

| Case-II | 10 | 10 | 11 | 45 |

| Case-III | 14 | 6 | 9.5 | 0 |

| Case-IV | 14 | 10 | 11 | 45 |

| Model | Number of Neurons | Hidden Layer | Activation Function | Learning Rate | Iterations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 20 | 2 | Tanh(x) | 0.006 | 150 |

| RBF | 20 | 2 | Radial basis function | 0.006 | 150 |

| GRU | 20 | 2 | Tanh(x) | 0.006 | 150 |

| Model | Data Volume (Training/Prediction) | Time Consumption of Training | Time Consumption of Prediction (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | 32,000/8000 | 1 h 45 min | 0.08 |

| RBF | 32,000/8000 | 1 h 39 min | 0.07 |

| GRU | 32,000/8000 | 1 h 47 min | 0.09 |

| Case ID | Predictable Time Scale | R2 | Loss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heave | Pitch | Roll | Heave | Pitch | Roll | ||

| Case-I | 6 s | 0.9315 | 0.9121 | —— | 6.95 × 10−4 | 7.09 × 10−4 | —— |

| 10 s | 0.8894 | 0.9071 | —— | 7.45 × 10−4 | 7.37 × 10−4 | —— | |

| Case-II | 6 s | 0.8935 | 0.8911 | 0.8123 | 7.45 × 10−4 | 7.39 × 10−4 | 8.07 × 10−4 |

| 10 s | 0.8784 | 0.8801 | 0.8093 | 7.95 × 10−4 | 7.97 × 10−4 | 8.71 × 10−4 | |

| Case-III | 6 s | 0.8375 | 0.8571 | —— | 7.85 × 10−4 | 7.79 × 10−4 | —— |

| 10 s | 0.8084 | 0.8001 | —— | 7.15 × 10−4 | 7.27 × 10−4 | —— | |

| Case-IV | 6 s | 0.7815 | 0.7957 | 0.7436 | 7.75 × 10−4 | 7.89 × 10−4 | 8.52 × 10−4 |

| 10 s | 0.7464 | 0.7460 | 0.7062 | 8.45 × 10−4 | 8.37 × 10−4 | 8.99 × 10−4 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, Q.; Liao, X.; Xu, J.; Lian, Y.; Chen, Z. A Hybrid LSTM-UDP Model for Real-Time Motion Prediction and Transmission of a 10,000-TEU Container Ship. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010101

Yu Q, Liao X, Xu J, Lian Y, Chen Z. A Hybrid LSTM-UDP Model for Real-Time Motion Prediction and Transmission of a 10,000-TEU Container Ship. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Qizhen, Xiyu Liao, Jun Xu, Yicheng Lian, and Zhanyang Chen. 2026. "A Hybrid LSTM-UDP Model for Real-Time Motion Prediction and Transmission of a 10,000-TEU Container Ship" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010101

APA StyleYu, Q., Liao, X., Xu, J., Lian, Y., & Chen, Z. (2026). A Hybrid LSTM-UDP Model for Real-Time Motion Prediction and Transmission of a 10,000-TEU Container Ship. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010101