Parametric Study on the Dynamic Response of a Barge-Jacket Coupled System During Transportation

Abstract

1. Introduction

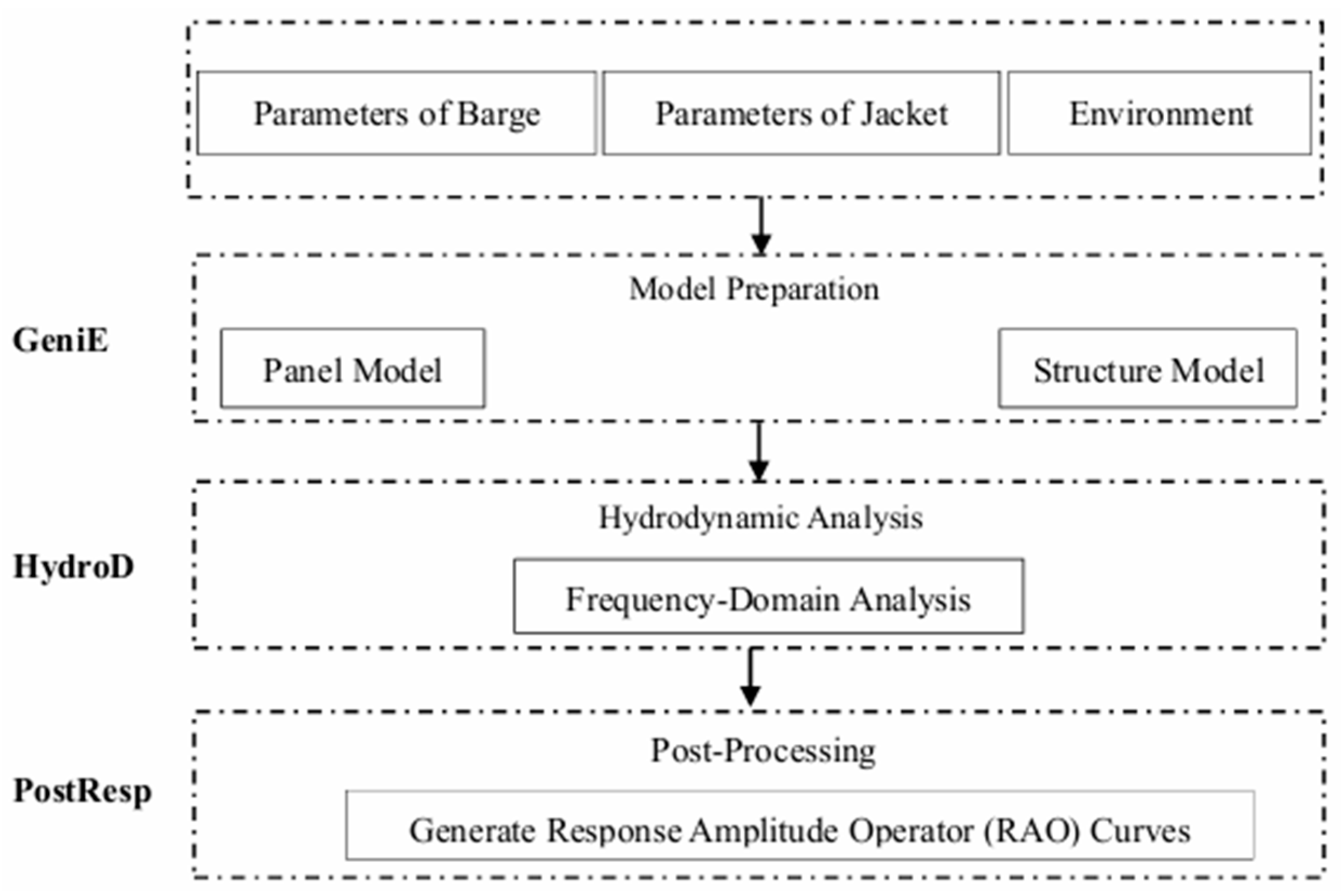

2. Research Methods

3. Numerical Model of Barge-Jacket Coupled System

3.1. Modeling in Genie

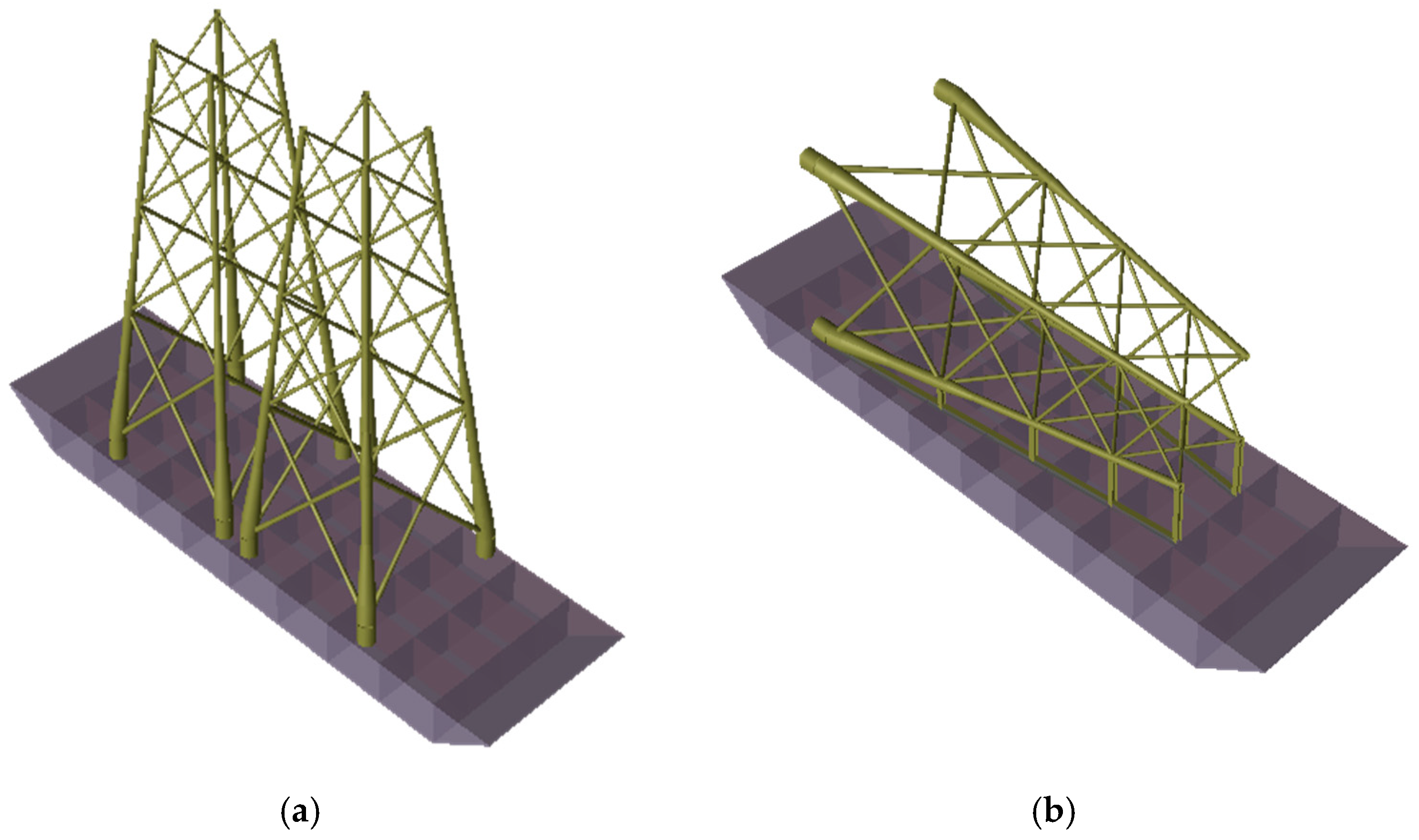

3.2. Jacket Foundation Arrangements

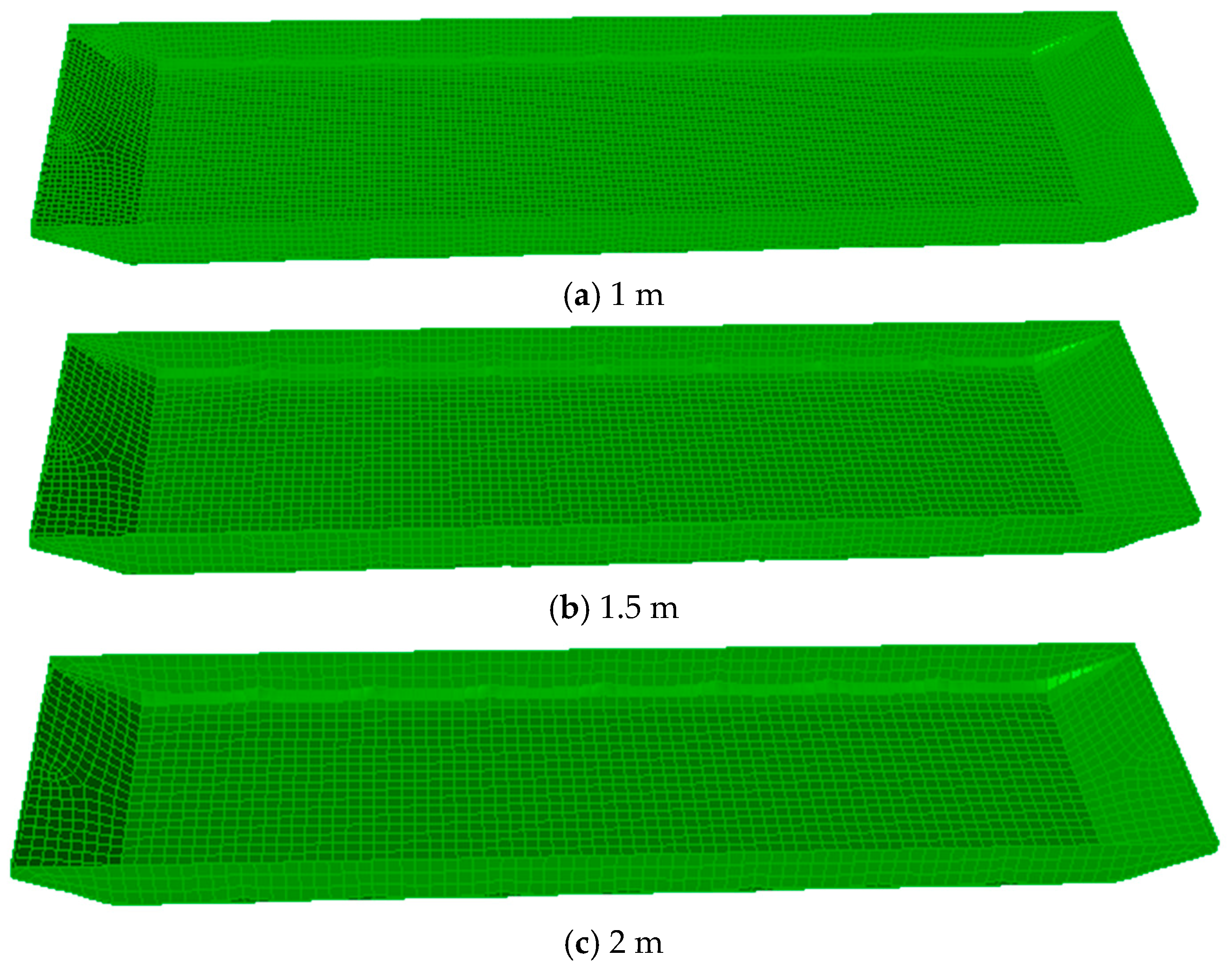

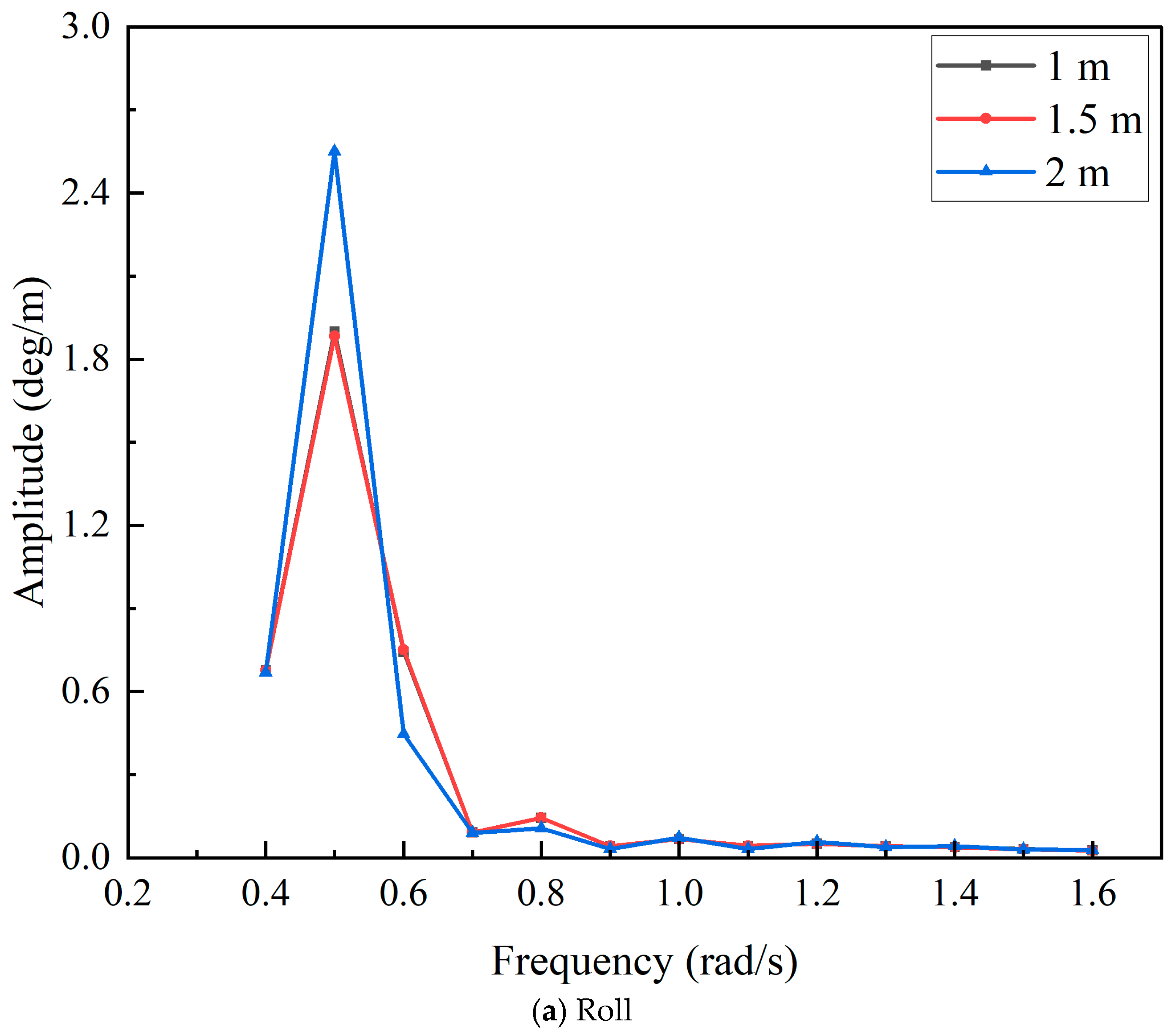

3.3. Panel Mesh Convergence Study

4. Frequency-Domain Hydrodynamic Analyses

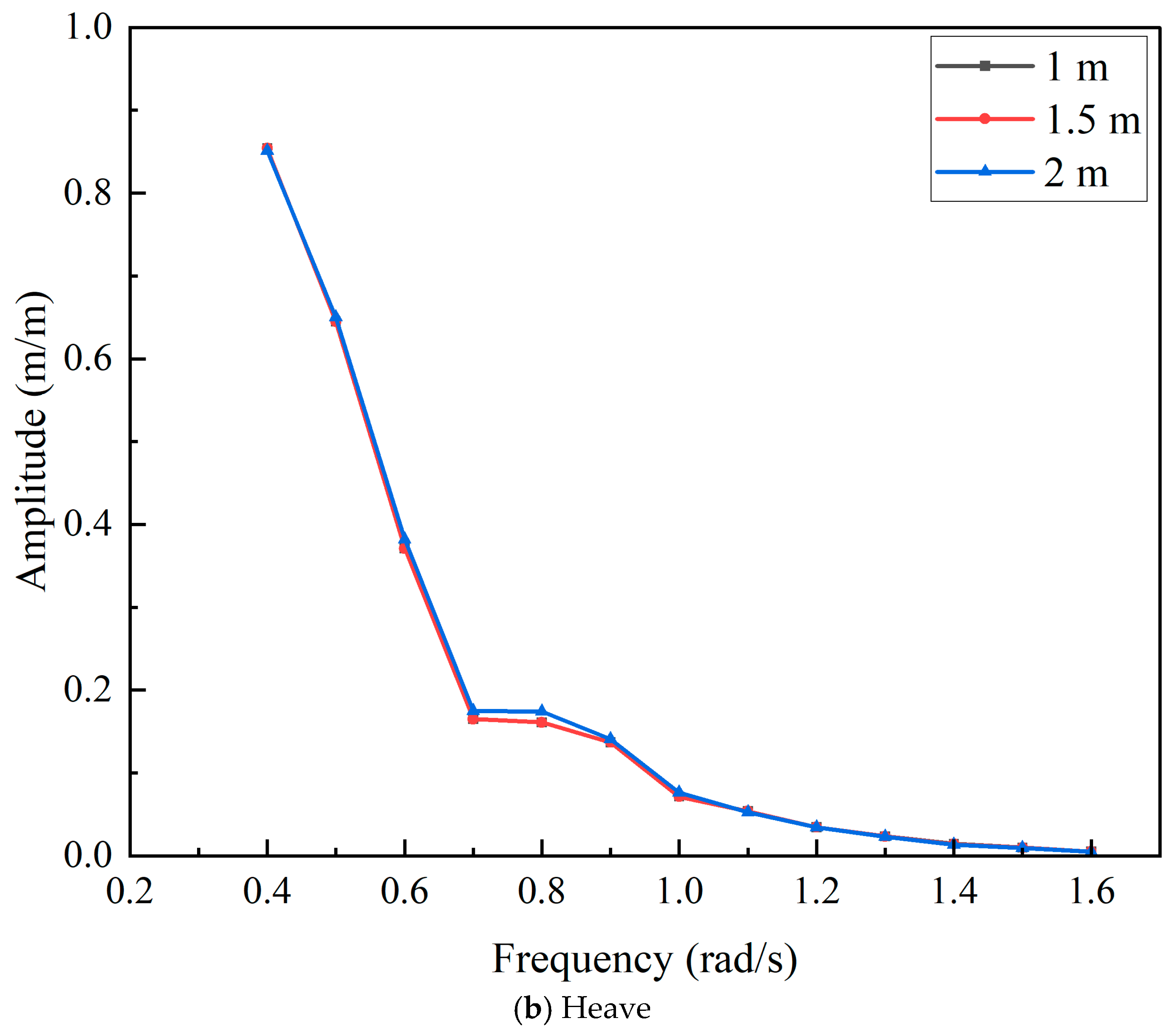

4.1. Influence of Wave Frequency

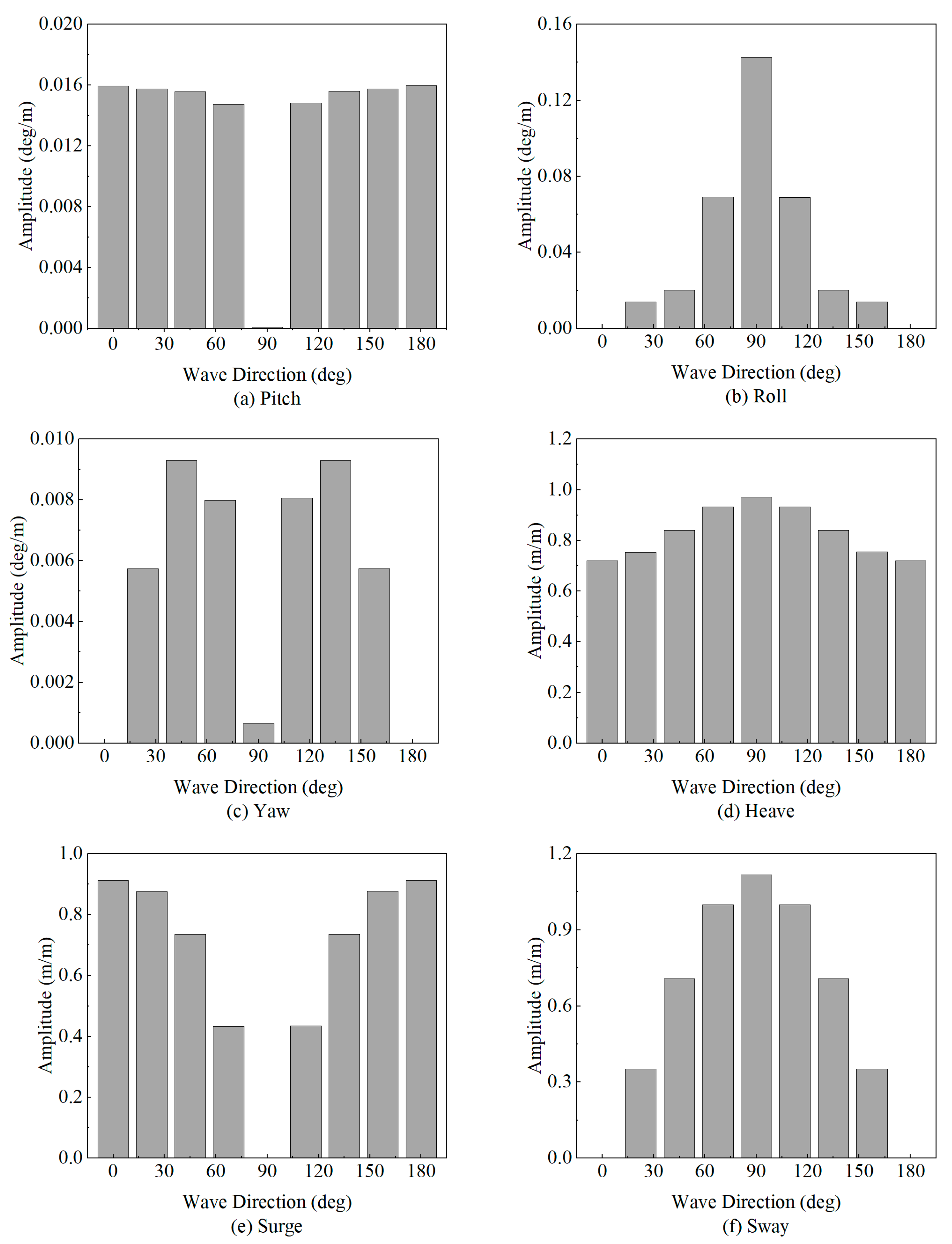

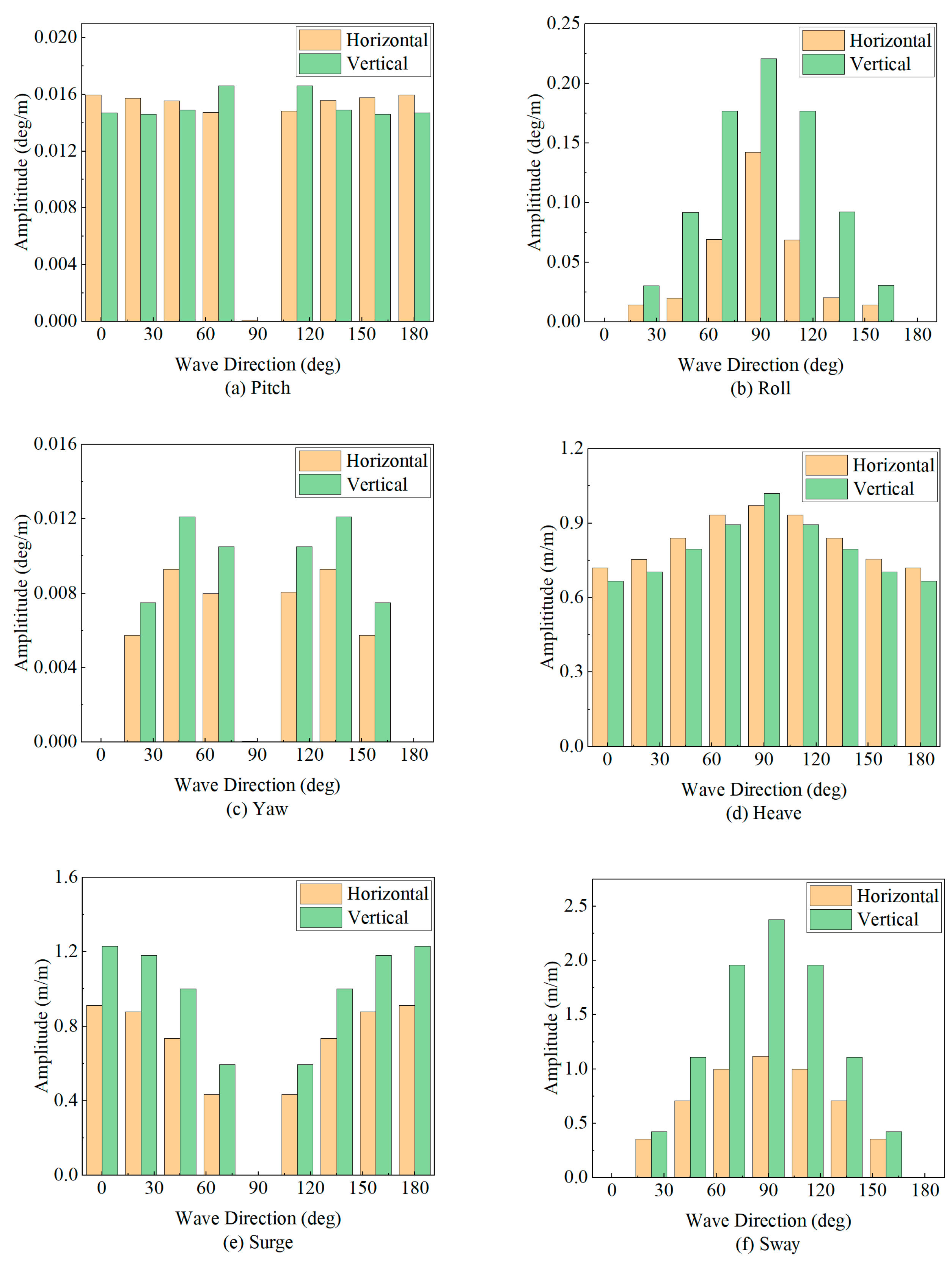

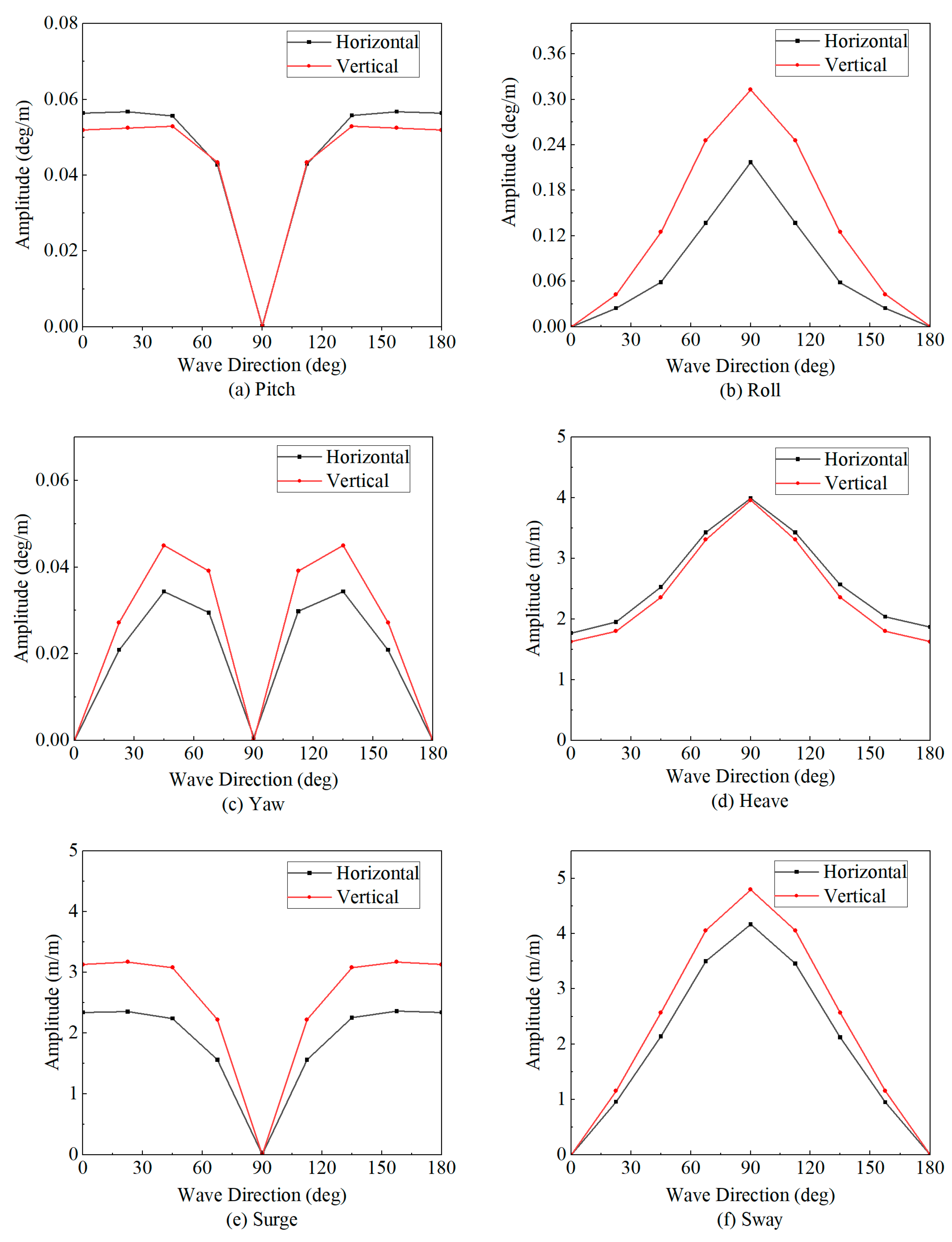

4.2. Influence of Wave Direction

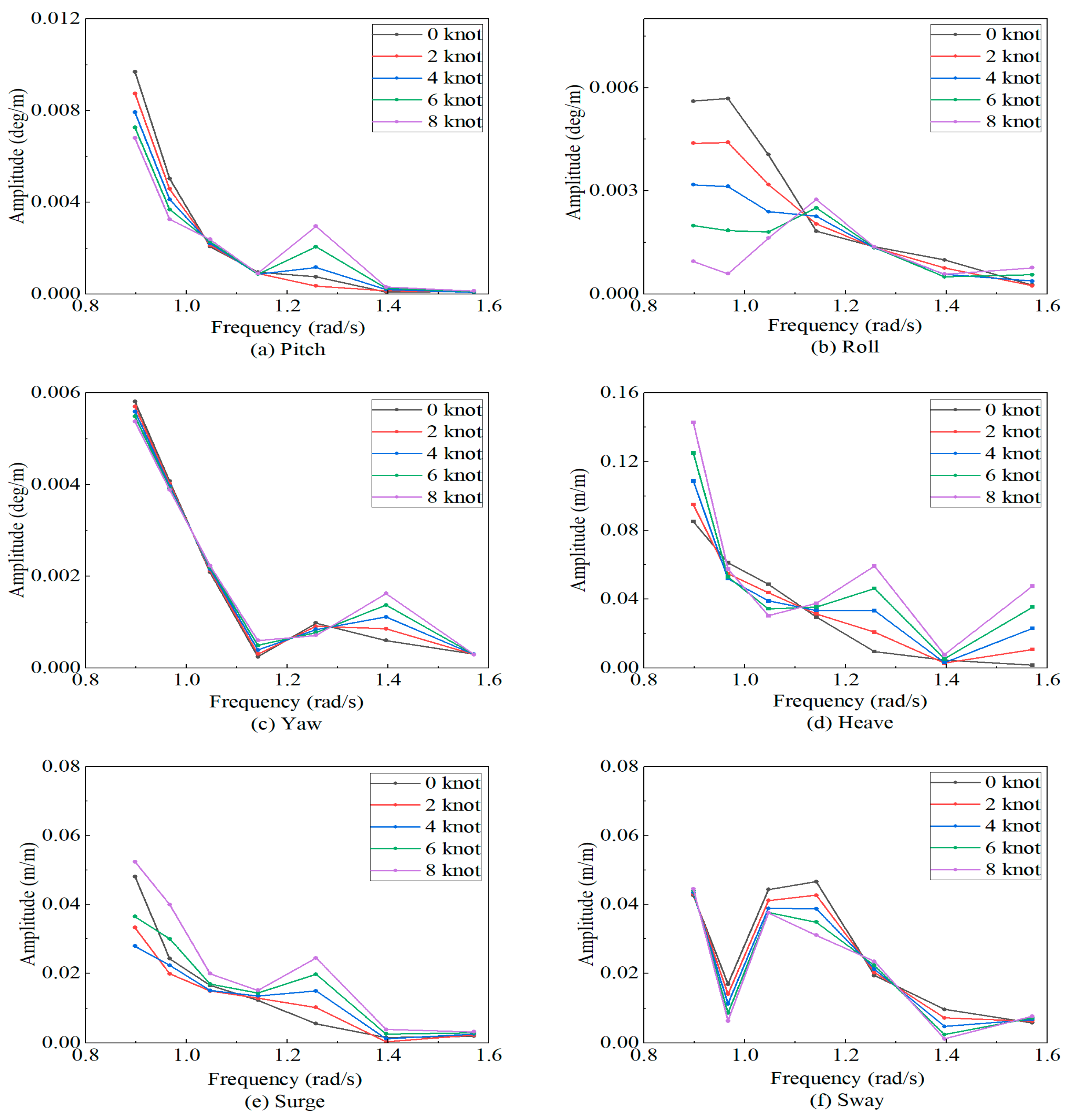

4.3. Influence of Forward Speed

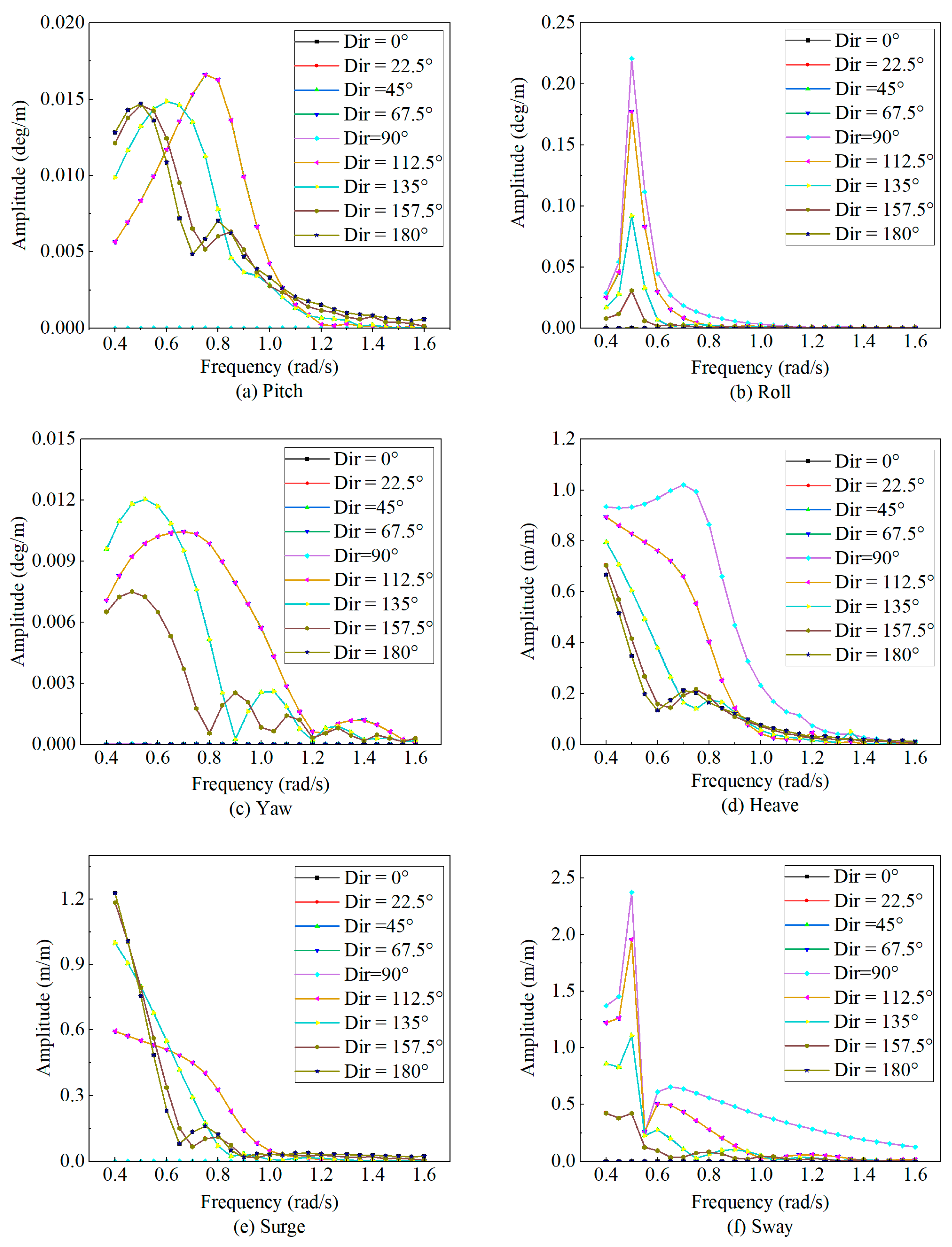

4.4. Influence of Arrangement

4.5. Short-Term Response Analysis

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Influence of Wave Frequency: The motion responses of the coupled system exhibit strong low-frequency dependence. Within the low-frequency wave region (0.5–0.8 rad/s), motion amplitudes are significantly amplified. In contrast, responses in the high-frequency region are significantly smaller and decay gradually. Transport operations should prioritize avoiding sea states within this critical frequency band.

- (2)

- Influence of Wave Direction: Wave direction has a distinct effect on each degree of freedom. Following seas (0°) and head seas (180°) predominantly excite longitudinal motions (surge and pitch), whereas beam seas (90°) induce the largest lateral (sway) and heave responses.

- (3)

- Influence of Forward Speed: Variations in forward speed (0–8 knots) induce relatively minor changes in motion response compared to wave frequency and direction. However, a consistent, gradual increase in Response Amplitude Operators (RAOs) is observed with increasing speed across all six degrees of freedom.

- (4)

- Influence of Jacket Arrangement: Both vertical and horizontal arrangements experience pronounced motion under low-frequency waves, with similar frequency ranges for peak response. However, the horizontal arrangement demonstrates a clear advantage in overall stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| OWT | Offshore Wind Turbine |

| DAF | Dynamic Amplification Factor |

| RAO | Response Amplitude Operator |

| Dir | Direction |

References

- Jiao, Y.F. Wind Power Expands to Deep Sea Areas Expecting a Peak Delivery Year in 2025. 21st Century Business Herald, 13 January 2025. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; Paul, S.; Kumar Saha, A.; Yadav, O. Recent Advancements in Planning and Reliability Aspects of Large-Scale Deep Sea Offshore Wind Power Plants: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 3738–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A.; López-Gutiérrez, J.S.; Esteban, M.D.; Negro, V. A Modified Method for Assessing Hydrodynamic Loads in the Design of Gravity-Based Structures for Offshore Wind Energy. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 85, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widianto, E.Å.; Fosså, K.T.; Hurff, J.; Khan, M.S. Offshore Concrete Gravity-Based Structures. Concr. Int. 2019, 41, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Hu, H.; Hu, J.; Feng, X.; Liu, T.; Ni, Z.; Yan, Y. A Validated Finite Element Framework for Stress Wave and Fatigue Analysis of Extra-Large Diameter Monopiles during Impact Driving. Ocean Eng. 2026, 343, 123449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, J.; Hou, L.; Wang, R.; Cheng, N. Experimental Investigation of the Response of Monopiles in Silty Seabed to Regular Wave Action. China Ocean Eng. 2022, 36, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.C. Construction and Application of Jacket Foundations for Offshore Wind Power Projects. Installation 2025, 57–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, P. Horizontal Bearing Performance of the Four-Bucket Jacket Foundation. J. Marine Sci. Appl. 2025, 24, 542–551. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Lian, J.J.; Yao, Y.; Liu, M.M. Permeability Characteristics and Critical Pressure Differential of Complex Configuration Suction Bucket Foundations for Offshore Wind Power. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2025, 46, 741–746. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.J. Comparison and Analysis of Foundation Type Selection for Offshore Wind Turbines. Ship Stand. Eng. 2025, 58, 109–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.D.; He, M.; Liu, S.Q.; Meng, W.C.; Cui, G.L.; Chen, K.C. Analysis on Stability and Motion Response Sensitivity of Large Jacket in Semi-submersible Barge Transportation. Petro-Chem Equip. 2021, 24, 28–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.L.; Tian, F.; Liu, P. Transportation Analysis of Deepwater Jackets. In Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Conference on Ocean Engineering, Guiyang, China, 1 November 2007; pp. 342–347. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhao, J.N.; Huang, H.Z.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Y.J. Analysis Method for Towing a 300 m Water Depth Deepwater Jacket. Ship Ocean Eng. 2023, 52, 102–104+136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, D.; Liu, J.; Hao, M.N. Offshore Installation Analysis of Deepwater Jacket Based on MOSES Software. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2025, 41, 72–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yang, S.M. Towing Analysis of Jacket Using SESAM Software. Petrochemical Ind. Technol. 2018, 25, 238–240+245. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.S.; Yuan, G.B.; Li, B.C.; Zhang, X.X.; Li, L. Dynamic Analysis and Extreme Response Evaluation of Lifting Operation of the Offshore Wind Turbine Jacket Foundation Using a Floating Crane Vessel. J. Ma. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yuan, G.; Li, B.; Li, C.B.; Ouyang, M.; Li, L.; Shi, W.; Han, Z.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z. Dynamic Analysis of Lift-off Operation of Offshore Wind Turbine Jacket Foundation from the Transportation Barge. Ocean Eng. 2024, 301, 117443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.T.H.; Amdahl, J.; Haver, S.K. Dynamic Amplification of Drag Dominated Structures in Irregular Seas. In Proceedings of the International Conference on OCEANS 15 MTS/IEEE Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Li, C.H.; Wu, X.Y.; Wang, C. Short-Term Motion Response Prediction of Large Upper Modules. Ocean Eng. Equip. Technol. 2016, 3, 25–30. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Yu, D.; Xie, P.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, A. Motion Monitoring of T-Shaped Launching Barge with LW3-1 Jacket Dry-Towing from Qingdao to South China Sea. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 32nd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Nantes, France, 9–14 June 2013; Volume 5, p. V005T06A03. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Luo, H.; Xie, P. Experimental Investigation on Motions Behavior and Loads Characteristic of Floatover Installation with T-Shaped Barge. Ocean Eng. 2020, 195, 106761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Kim, B.; Pham, T.D.; Jung, K. Motion of OC4 5MW Semi-Submersible Offshore Wind Turbine in Irregular Waves. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 32nd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Nantes, France, 9–14 June 2013; Volume 8, p. V008T09A02. [Google Scholar]

- Tahar, A.; Halkyard, J.; Steen, A.; Finn, L. Float Over Installation Method—Comprehensive Comparison Between Numerical and Model Test Results. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2006, 128, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Analysis of Hydrodynamic Characteristics and Installation Dynamics of a Novel Offshore Wind Turbine Transport and Installation Vessel. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.M.; Zhang, W.Z.; Yuan, Y.P.; Lu, H.Y.; Guo, J.B.; Xu, Y.Q. Accelerated Thermal Fatigue and Equivalent Life Assessment Method for Highly Intensified Diesel Engine Pistons. Acta Armamentarii 2022, 43, 3008–3019. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Module Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Length overall (m) | 149.8 |

| Beam (m) | 40.2 |

| Depth (m) | 9.2 |

| Displacement (tons) | 15,000 |

| COG (m) | (0, 0, 5.0) |

| Ixx (kg·m2) | 1.8 × 109 |

| Iyy (kg·m2) | 2.0 × 1010 |

| Izz (kg·m2) | 2.1 × 1010 |

| Module Characteristic | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Length of footprint (m) | 35 | |

| Height of main body (m) | 90 | |

| Total mass (tons) | 2942 | |

| COG (m) | Vertical | (0, 0, 50) |

| Horizontal | (−9.4, 0, 27.9) | |

| Ixx (kg·m2) | Vertical | 5.6 × 109 |

| Horizontal | 1.04 × 109 | |

| Iyy (kg·m2) | Vertical | 8.2 × 109 |

| Horizontal | 2.86 × 109 | |

| Izz (kg·m2) | Vertical | 4.6 × 109 |

| Horizontal | 2.84 × 109 | |

| Wave Direction | Surge | Sway | Heave | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (deg) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) |

| 0 | 0.912 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.800 | 0.719 | 0.400 |

| 22.5 | 0.876 | 0.400 | 0.353 | 0.400 | 0.754 | 0.400 |

| 45 | 0.735 | 0.400 | 0.708 | 0.400 | 0.841 | 0.400 |

| 67.5 | 0.435 | 0.400 | 1.000 | 0.400 | 0.932 | 0.400 |

| 90 | 0.001 | 0.750 | 1.120 | 0.400 | 0.971 | 0.400 |

| 112.5 | 0.435 | 0.400 | 1.000 | 0.400 | 0.932 | 0.400 |

| 135 | 0.736 | 0.400 | 0.707 | 0.400 | 0.841 | 0.400 |

| 157.5 | 0.877 | 0.400 | 0.353 | 0.400 | 0.755 | 0.400 |

| 180 | 0.912 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.800 | 0.721 | 0.400 |

| Wave Direction | Roll | Pitch | Yaw | |||

| (deg) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) |

| 0 | 0.000 | 1.450 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.500 |

| 22.5 | 0.014 | 0.750 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.006 | 0.500 |

| 45 | 0.020 | 0.800 | 0.016 | 0.600 | 0.009 | 0.550 |

| 67.5 | 0.069 | 0.750 | 0.015 | 0.750 | 0.008 | 0.650 |

| 90 | 0.143 | 0.750 | 0.000 | 0.800 | 0.001 | 0.800 |

| 112.5 | 0.069 | 0.750 | 0.015 | 0.750 | 0.008 | 0.700 |

| 135 | 0.020 | 0.800 | 0.016 | 0.600 | 0.009 | 0.550 |

| 157.5 | 0.014 | 0.750 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.006 | 0.500 |

| 180 | 0.000 | 1.450 | 0.016 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.500 |

| Wave Direction | Surge | Sway | Heave | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (deg) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (m/m) | Frequency (rad/s) |

| 0 | 1.228 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.667 | 0.400 |

| 22.5 | 1.184 | 0.400 | 0.422 | 0.400 | 0.704 | 0.400 |

| 45 | 1.000 | 0.400 | 0.855 | 0.400 | 0.795 | 0.400 |

| 67.5 | 0.595 | 0.400 | 1.377 | 0.500 | 0.893 | 0.400 |

| 90 | 0.000 | 0.750 | 1.655 | 0.500 | 1.021 | 0.700 |

| 112.5 | 0.595 | 0.400 | 1.377 | 0.500 | 0.893 | 0.400 |

| 135 | 1.000 | 0.400 | 0.855 | 0.400 | 0.795 | 0.400 |

| 157.5 | 1.184 | 0.400 | 0.422 | 0.400 | 0.704 | 0.400 |

| 180 | 1.228 | 0.400 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.667 | 0.400 |

| Wave Direction | Roll | Pitch | Yaw | |||

| (deg) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) | Amplitude (deg/m) | Frequency (rad/s) |

| 0 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.350 |

| 22.5 | 0.020 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.500 | 0.008 | 0.500 |

| 45 | 0.060 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.600 | 0.012 | 0.550 |

| 67.5 | 0.115 | 0.500 | 0.017 | 0.750 | 0.010 | 0.700 |

| 90 | 0.143 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.800 | 0.000 | 0.500 |

| 112.5 | 0.115 | 0.500 | 0.017 | 0.750 | 0.010 | 0.700 |

| 135 | 0.060 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.600 | 0.012 | 0.550 |

| 157.5 | 0.020 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.500 | 0.008 | 0.500 |

| 180 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.015 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.300 |

| Motion | Maximum Amplitude | Wave Direction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch | Horizontal | 0.057° | Horizontal | 22.5° |

| Vertical | 0.053° | Vertical | 45° | |

| Roll | Horizontal | 0.217° | Horizontal | 90° |

| Vertical | 0.313 | Vertical | 90° | |

| Yaw | Horizontal | 0.034° | Horizontal | 45° |

| Vertical | 0.045° | Vertical | 45° | |

| Heave | Horizontal | 3.99 m | Horizontal | 90° |

| Vertical | 3.96 m | Vertical | 90° | |

| Surge | Horizontal | 2.36 m | Horizontal | 157.5° |

| Vertical | 3.17 m | Vertical | 22.5° | |

| Sway | Horizontal | 4.17 m | Horizontal | 90° |

| Vertical | 4.8 m | Vertical | 90° | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shi, R.; Zhang, X.; Xia, Y.; He, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J. Parametric Study on the Dynamic Response of a Barge-Jacket Coupled System During Transportation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010100

Shi R, Zhang X, Xia Y, He B, Zhang Z, Zhang J. Parametric Study on the Dynamic Response of a Barge-Jacket Coupled System During Transportation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):100. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010100

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Ruilong, Xiaolan Zhang, Yanhui Xia, Ben He, Zhihong Zhang, and Jianhua Zhang. 2026. "Parametric Study on the Dynamic Response of a Barge-Jacket Coupled System During Transportation" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010100

APA StyleShi, R., Zhang, X., Xia, Y., He, B., Zhang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2026). Parametric Study on the Dynamic Response of a Barge-Jacket Coupled System During Transportation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 100. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010100