Natural Fracturing in Marine Shales: From Qualitative to Quantitative Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Traditional Research History of Natural Fractures

2.1. Tectonic Fractures

2.2. Bedding-Parallel Fractures

3. Advances in Fracture Timing Analysis

4. Advances in Geochemical Analysis of Fracture Cements

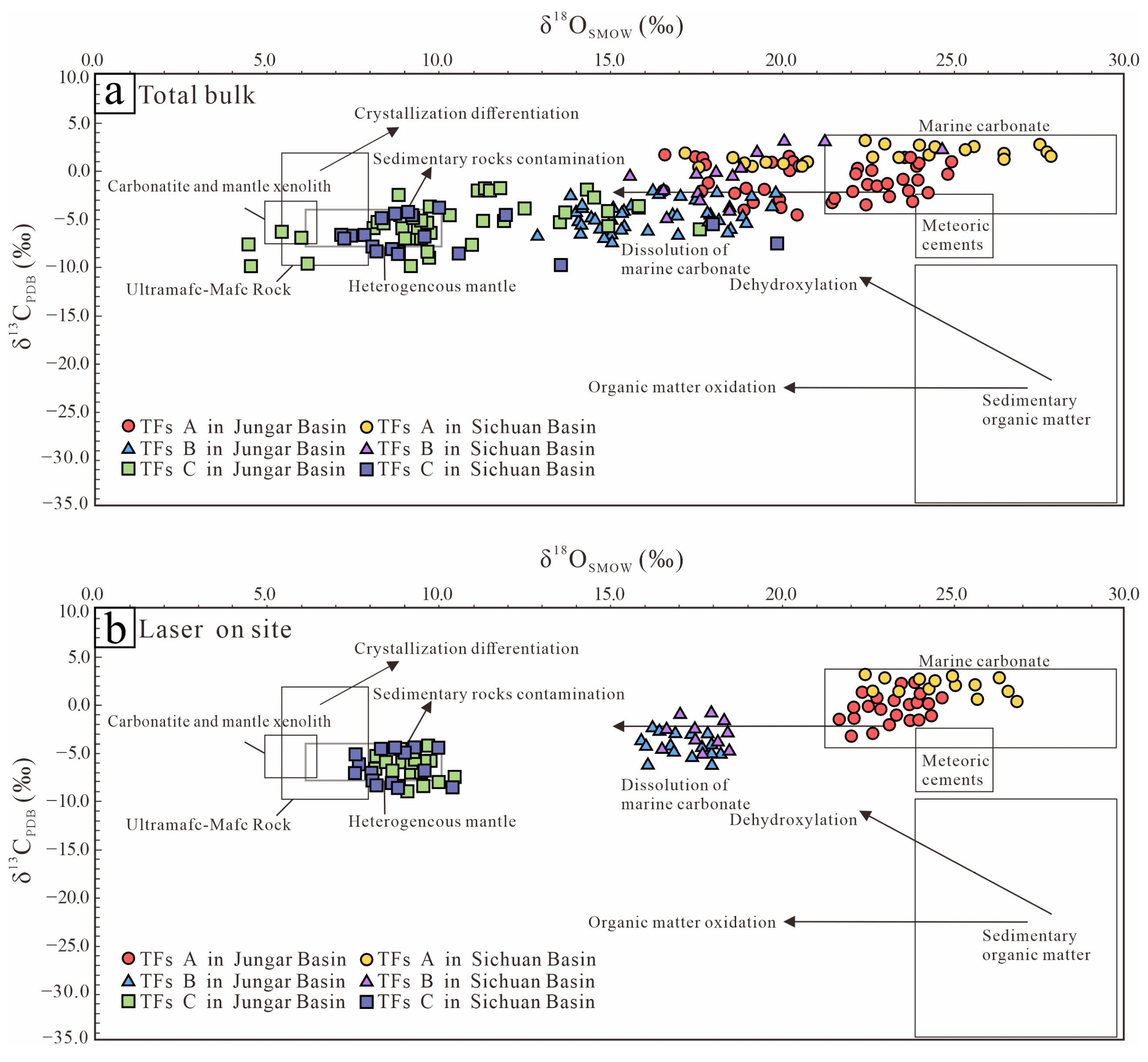

4.1. Traditional”Bulk Rock”Analysis

4.2. High-Precision Micro-Area In Situ Geochemical Analysis

5. Advances in Fracture Geochronology Analysis

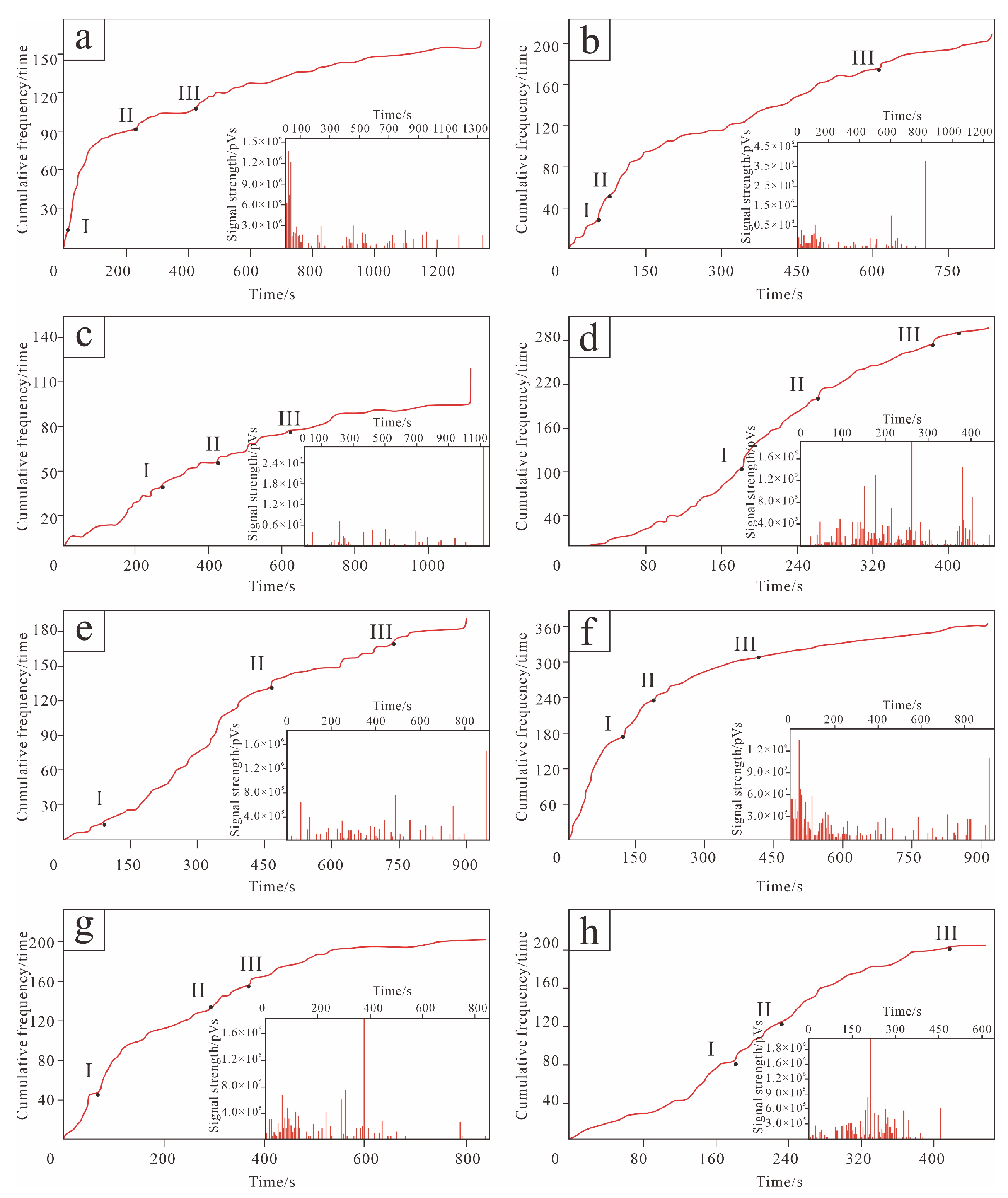

5.1. Fluid Inclusion Methodology

5.2. K-Ar and Ar-Ar Dating

5.3. Isotope Dilution Methods

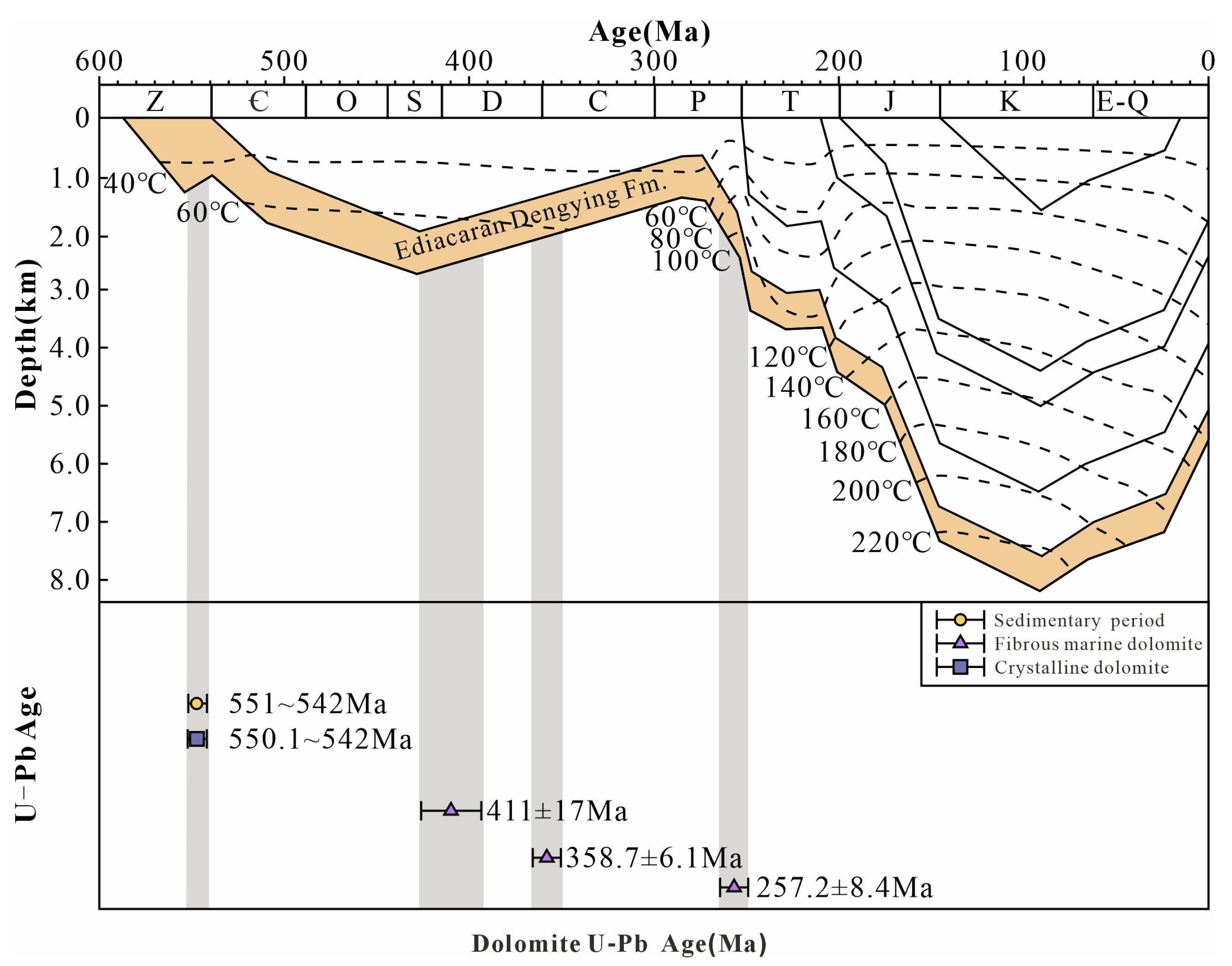

5.4. Carbonate U-Pb Dating

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Evolution of Research Methods: The quantitative evolution of tectonic fracture research—from theoretical models based on structural curvature and elastic strain energy to numerical stress field simulations—has significantly improved the efficiency of fracture prediction and the accuracy of distribution patterns. The integration of geomechanics and fractal theory has enhanced the clarity and applicability of fracture characterization. For bedding-parallel fractures, the adoption of cement geochemistry and critical stress analysis has elucidated the synergistic interactions among sedimentary microfacies, tectonic stress, and fluid activity, contributing to a more systematic and mechanistically transparent understanding. However, research in this area remains largely qualitative, particularly regarding the dynamic mechanisms of fracture aperture and closure, limiting current practical applicability.

- (2)

- Technological Breakthroughs: Advances in micro-scale in situ analytical techniques (e.g., LA-ICP-MS, femtosecond laser ablation) allow high-precision spatial resolution of trace elements and isotopes within fracture cements. These methods reduce ambiguity in fluid interpretation and provide clearer geochemical fingerprints compared to traditional approaches. Similarly, carbonate U-Pb dating offers more reliable geochronological constraints on fluid events.

- (3)

- Identification of Multi-phase Fractures: The application of the rock acoustic emission (Kaiser) effect combined with stress-field reconstruction has made it possible to efficiently identify multi-phase fracture events. Coupling these with geochemical and geochronological data provides explicit insights into the spatiotemporal relationships among tectonic events, hydrocarbon generation/expulsion, and fracture development, greatly improving interpretive clarity.

- (4)

- Current Challenges and Future Outlook: Despite progress, key challenges remain, including the difficulty in distinguishing overlapping multi-phase fluid events and the limited capacity for dynamic simulation of fracture behavior. Future work should focus on integrating artificial intelligence, multi-scale numerical simulations, and 4D modeling to achieve quantitative permeability characterization and predictive accuracy of fracture networks. Further research into the cross-scale coupling of fractures, fluids, and hydrocarbon migration will be critical to supporting practical applications in deep and ultra-deep exploration.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, S.P.; Eichhubl, P.; Laubach, S.E.; Reed, R.M.; Lander, R.H.; Bodnar, R.J. A 48 m.y. history of fracture opening, temperature, and fluid pressure: Cretaceous Travis Peak Formation, East Texas basin. GSA Bull. 2010, 122, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.R.; Fitts, J.P.; Bromhal, G.S.; Mclntyre, D.L.; Tappero, R.; Peters, C.A. Dissolution-Driven Permeability Reduction of a Fractured Carbonate Caprock. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2013, 30, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, A.; Eichhubl, P.; Bodnar, R.J.; Laubach, S.E.; Davis, S. Natural hydraulic fracturing of tight-gas sandstone reservoirs, Piceance Basin, Colorado. GSA Bull. 2015, 127, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Laubach, S.E. Subsurface fractures and their relationship to stress history in East Texas basin sandstone. Tectonophysics 1988, 156, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubach, S.E.; Ward, M.E. Diagenesis in porosity evolution of opening-mode fractures, Middle Triassic to Lower Jurassic La Boca Formation, NE Mexico. Tectonophysics 2006, 419, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, G.S.; Agosta, F.; Aldega, L.; Prosser, G.; Smeraglia, L.; Tavani, S.; Looser, N.; Guillong, M.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Billi, A. Structural architecture and maturity of Val d’Agri faults, Italy: Inferences from natural and induced seismicity. J. Struct. Geol. 2024, 180, 105084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeraglia, L.; Aldega, L.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Billi, A.; Bigi, S.; di Marcantonio, E.; Fiorini, A.; Kylander-Clark, A.; Carminati, E. Structural and stratigraphic control on fluid flow in the Mt. Conero anticline, Italy: An analog for offshore resource reservoirs in fold-and-thrust belts. J. Struct. Geol. 2025, 200, 105502. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, A.; Eichhubl, P.; Cumella, S.P.; Bodnar, R.J.; Laubach, S.E.; Becker, S.P. Testing the basin-centered gas accumulation model using fluid inclusion observations: Southern Piceance Basin, Colorado. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 2297–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.F.W.; Reed, R.M.; Holder, J. Natural fractures in the Barnett Shale and their importance for hydraulic fracture treatments. AAPG Bull. 2007, 91, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laubach, S.E.; Fall, A.; Copley, L.K.; Marrett, R.; Wilkins, S. Fracture porosity creation and persistence in a basement-involved Laramide fold, Upper Cretaceous Frontier Formation, Green River Basin, USA. Geol. Mag. 2016, 153, 887–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.E.; Laubach, S.E.; Lander, R.H. Natural fracture characterization in tight gas sandstones: Integrating mechanics and diagenesis. AAPG Bull. 2009, 93, 1535–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.A. Geologic Analysis of Naturally Fractured Reservoirs; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2001; pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.B.; Qi, J.F.; Wang, Y.X. Origin type of tectonic fractures and geological conditions in low-permeability reservoirs. Acta Pet. Sin. 2007, 28, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.L.; Zeng, W.T.; Wang, Z.; Jiu, K.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.X.; Wang, X.H. Method and application of tectonic stress field simulation and fracture distribution prediction in shale reservoir. Earth Sci. Front. 2016, 23, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Hooker, J.N.; Gale, J.F.W.; Gomez, L.A.; Laubach, S.E.; Marrett, R.; Reed, R.M. Aperture-size scaling variations in a low-strain opening-mode fracture set, Cozzette Sandstone, Colorado. J. Struct. Geol. 2009, 31, 707–718. [Google Scholar]

- Schirripa Spagnolo, G.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Aldega, L.; Castorina, F.; Billi, A.; Smeraglia, L.; Agosta, F.; Prosser, G.; Tavani, S.; Carminati, E. Interplay and feedback between tectonic regime, faulting, sealing horizons, and fluid flow in a hydrocarbon-hosting extensional basin: The Val d’Agri Basin case, Southern Italy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 646, 118982. [Google Scholar]

- Curzi, M.; Aldega, L.; Billi, A.; Boschi, C.; Carminati, E.; Vignaroli, G.; Viola, G.; Bernasconi, S.M. Fossil chemical-physical (dis)equilibria between paleofluids and host rocks and their relationship to the seismic cycle and earthquakes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 254, 104801. [Google Scholar]

- Smeraglia, L.; Bernasconi, S.; Manniello, C.; Spanos, D.; Pagoulatos, A.; Aldega, L.; Kylander-Clark, A.; Jaggi, M.; Agosta, F. Regional scale, fault-related fluid circulation in the Ionian zone of the external Hellenides fold-and-thrust belt, western Greece: Clues for fluid flow in fractured carbonate reservoirs. Tectonics 2023, 42, e2023TC007867. [Google Scholar]

- Curzi, M.; Caracausi, A.; Rossetti, F.; Rabiee, A.; Billi, A.; Carminati, E.; Aldega, L.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Boschi, C.; Drivenes, K.; et al. From fossil to active hydrothermal outflow in the back-arc of the central Apennines (Zannone Island, Italy). Geochem. Geophys Geosystems 2022, 23, e2022GC010474. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, D.V.; Hemming, S.R.; Turrin, B.D. Laschamp Excursion at Mono Lake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2002, 197, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.D. Optimizing experimental design for coupled porous media flow studies. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 1990, 3, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudigel, P.T.; Murray, S.; Dunham, D.P.; Frank, T.D.; Fielding, C.R.; Swart, P.K. Cryogenic Brines as Diagenetic Fluids: Reconstructing the Diagenetic History of the Victoria Land Basin using Clumped Isotopes. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2018, 224, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dering, G.M.; Micklethwaite, S.; Cruden, A.R.; Barnes, S.J.; Fiorentini, M.L. Evidence for dyke-parallel shear during syn-intrusion fracturing. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2019, 507, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, D.; Bonini, M.; Corti, G.; Agostini, A.; Del Ventisette, C. Forced folding above shallow magma intrusions: Insights on supercritical fluid flow from analogue modelling. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2017, 345, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.J.; Hu, A.P.; Cheng, T.; Liang, F.; Pan, W.Q.; Feng, Y.X.; Zhao, J.X. Laser ablation in situ U-Pb dating and its application to diagenesis-porosity evolution of carbonate reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 1062–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Su, A.; Chen, H.H.; Feng, Y.X.; Zhao, J.X.; Wang, Z.C.; Hu, M.Y.; Jiang, H.; Nguyen, A.D. In situ U-Pb dating and geochemical characterization of multi-stage dolomite cementation in the Ediacaran Dengying Formation, Central Sichuan Basin, China: Constraints on diagenetic, hydrothermal and paleo-oil filling events. Precambrian Res. 2022, 368, 106481. [Google Scholar]

- Worden, R.H.; Benshatwan, M.S.; Potts, G.J.; Elgarmadi, S.M. Basin-Scale Fluid Movement Patterns Revealed by Veins: Wessex Basin, UK. Geofluids 2015, 16, 149–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Hu, W.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liao, Z.; Li, W. Resetting of Mg isotopes between calcite and dolomite during burial metamorphism: Outlook of Mg isotopes as geothermometer and seawater proxy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 208, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, P.J.; Giles, M.R.; Ainsworth, P. K-Ar dating of illites in Brent Group reservoirs: A regional perspective. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1992, 61, 377–400. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, D.; Schneider, J.; Chiaradia, M. Timing and metal sources for carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb mineralization in the Franklinian Basin (North Greenland): Constraints from Rb-Sr and Pb isotopes. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 79, 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, D.F.; Green, P.F.; Parnell, J.; Kelley, S.P.; Lee, M.R.; Sherlock, S.C. Late Palaeozoic hydrocarbon migration through the Clair field, West of Shetland, UK Atlantic margin. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 2510–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.Z.; Guo, H.L.; Zhang, B.M.; Zhang, N. Petrography, classification, terminology and fundamental questions ignored usually of inclusion in sediment rocks. Chin. J. Geol. 2003, 38, 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J.E. Natural fracture pattern characterization using a mechanically-based model constrained by geologic data—Moving closer to a predictive tool. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997, 34, 171. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Song, X.M.; Zhang, A.Q. A new technique to predict fractures of alluvial fan conglomerate reservoir. Acta Pet. Sin. 2000, 21, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- George, H.M. Quantitative fracture study-Sanish Pool McKenzie Country North Dakota. AAPG Bull. 1968, 52, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Price, N.J. Fault and Joint Development in Brittle and Semi-Brittle Rock; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; pp. 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, D.D.; Aydin, A. Progress in understanding jointing over the past century. GSA Bull. 1988, 100, 1181–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cmexob, E.M. The Basic Theory and Methods of Exploration for Fractured Oil and Gas Reservoirs; Petroleum Industry Press: Beijing, China, 1985; pp. 1–233. [Google Scholar]

- Narr, W.; Currie, J.B. Origin of fracture porosity—Example from Altamont Field, Utah. AAPG Bull. 1982, 66, 1231–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Crampin, S. A review of wave motion in anisotropic and cracked elastic-media. Wave Motion 1981, 3, 343–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.H.; Aviles, C.A. Fractal dimension of the 1906 San Andreas fault and 1915 Pleasant Valley faults (abstract). Earthq. Notes 1985, 55, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, C.C.; Pointe, P.R. Fractals in the Earth Sciences; Pointe Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 1–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J.A. Wave speeds and attenuation of elastic waves in material containing cracks. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 64, 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Withjack, M.O.; Olson, J.; Peterson, E. Experimental models of extensional forced folds. AAPG Bull. 1990, 74, 1038–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali, M.R.; Dusseault, M.B. Coupling Geomechanics and Transport in Naturally Fractured Reservoirs. Int. J. Min. Geo-Eng. 2012, 45, 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R. Application and development of finite element and other numerical simulation methods in earth sciences in China. Acta Geophys. Sin. 1994, 37, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.G.; Zhang, L.Y.; Fan, K. The research situation and progresses of natural fracture for low permeability reservoirs in oil and gas basin. Geol. Rev. 2006, 52, 777–782. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.T.; Wen, S.P. Methods of quantitative description and prediction for structural fracture of subsurface reservoir. J. Univ. Pet. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 1996, 20, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.Z.; Zeng, H.R.; Sun, X.J.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.Q. Numerical simulation of reservoir paleostress field. Seismol. Geol. 1999, 21, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Qian, X.L.; Huo, H.; Yang, Y.Q. A new method for quantitative prediction of tectonic fractures–Two-Factor method. Oil Gas Geol. 1998, 19, 3–9+16. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.G.; Lei, M.S.; Wan, T.F.; Jie, W.Q. Numerical simulation of palaeotectonic stress field of Yingchen Fm in Gulong-Xujiaweizi area: Prediction and comparative study of tectoclase development area. Oil Gas Geol. 2006, 27, 78–84+105. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, G.H. Application of the finite element numerical simulation method in fracture prediction. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2008, 15, 24–26+29+112. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.Q. Application of numerical simulation technology for 3D structural stress field in predicting shale fractures. Sci. Technol. West China 2008, 7, 1–2+39. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.B.; Qi, J.F.; Wang, C.G.; Li, Y.L. The influence of tectonic stress on fracture foemation and fluid flow. Earth Sci. Front. 2008, 15, 292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Séjourné, S.; Malo, M.; Savard, M.M.; Kirkwood, D. Multiple origin and regional significance of bedding parallel veins in a fold and thrust belt: The example of a carbonate slice along the Appalachian structural front. Tectonophysics 2005, 407, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, S.K. Lithostratigraphic controls on bedding-plane fractures and the potential for discrete groundwater flow through a siliciclastic sandstone aquifer, southern Wisconsin. Sediment. Geol. 2007, 197, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbold, P.R.; Zanella, A.; Rodrigues, N.; Loseth, H. Bedding-parallel fibrous veins (beef and cone-in-cone): Worldwide occurrence and possible significance in terms of fluid overpressure, hydrocarbon generation and mineralization. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2013, 43, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, S.K.; Henley, R.W.; Heinrich, C.A. Gold precipitation by fluid mixing in bedding-parallel fractures near Carbonaceous slates at the Cosmopolitan Howley gold deposit, northern Australia. Econ. Geol. 1995, 90, 2123–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doolin, D.M.; Mauldon, M. Fracture permeability normal to bedding in layered rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2001, 38, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.J.; Tang, H.J.; An, F.S. Causese of bedding-parallel fractures of tight sand gasreservoir in Xinchang, West Sichuan region. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2003, 30, 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.F.; Mu, L.X.; Zhao, H.Y. Distribution of the fracture within the low permeability sandstone reservoir of Baka oilfield, Tuha Basin, Northwest China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2003, 30, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.F.; Lan, C.L. Fractures and faults distribution and its effect on gas enrichment areas in Ordos Basin. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2006, 33, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.J.; Liu, B.J.; Wang, P. Genesis of bedding-parallel fractures and its influences on reservoirs in Jurassic, Yongjin area, Junggar Basin. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2011, 18, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.P.; Qin, Q.R.; Wang, B.Q.; Liu, Z.L. Controlling factors of fracture distribution in tight sandstone reservoir of Xujiahe Formation in DY structure, western Sichuan. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2011, 18, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.B.; Zheng, B.; Yuan, D.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.Q. Characteristics and main controlling factors of fractures in gas reservoir of Xujiahe Formation, Dayi Structure. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2013, 35, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.M.; He, L.; Wu, J. Genesis of Bedding-Parallel fractures in tight sandstone gas reservoirs of member 4, Xujiahe Formation, Yuanba area, Northeastern Sichuan Basin, and their identification via image logging. Chem. Enterp. 2014, 25, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, C.; Ru, Z. Behavior of propagating fracture at bedding interface in layered rocks. Eng. Geol. 2015, 197, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Cui, Y.K.; Mu, R.; Li, J. Occurrence Characteristics and Relation on Oil and Gas Distribution of Bedding Fractures in Tight Gas Sand. Adv. Geosci. 2021, 11, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.H.; Liu, T.F.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gou, T.; Zhang, M.Y.; He, X. The research progress and consideration of non-tectonic fractures in shale reservoirs. Earth Sci. Front. 2023, 31, 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch, C.V.; Journel, A.G. GSLIB: Geostatistical Software Library and User’s Guide, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lisle, R.J. Detection of zones of abnormal strains in structures using Gaussian curvature analysis. AAPG Bull. 1994, 78, 1811–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bour, O.; Davy, P. On the connectivity of three-dimensional fault networks. Water Resour. Res. 1998, 34, 2611–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B.S. Validating seismic attribute studies: Beyond statistics. Lead. Edge 2002, 21, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.C.; Larsen, E. Fractal geometry of two-dimensional fracture networks at Yucca Mountain, Southwestern Nevada. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Fundamentals of Rock Joints, Björkliden, Sweden, 15–20 September 1985; Centek Publishers: Newton Abbot, UK, 1985; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W.; Hou, G.T.; Huang, S.Y.; Sun, X.W.; Shen, Y.M.; Ren, K.X. Constraints and Controls of Fault Related Folds on the Development of Tectonic Fractures in Sandstones. Geol. J. China Univ. 2014, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.H.P.; Frechen, J.; Degens, E.T. Oxygen and carbon isotope studies of carbonatites from the Laacher See District, West Germany and the Alnö District, Sweden. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1967, 31, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.F.; Zhou, M.F. Generation and evolution of siliceous high magnesium basaltic magmas in the formation of the Permian Huangshandong intrusion (Xinjiang, NW China). Lithos 2013, 162–163, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.C.; Li, C.; Qin, K.Z.; Tang, D.M. A non-plume model for the Permian protracted (266–286 Ma) basaltic magmatism in the Beishan–Tianshan region, Xinjiang, Western China. Lithos 2016, 256, 243–249. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, D.D.; Jiang, Z.X.; Song, Y.; Luo, Q.; Wang, X. Mechanism for the formation of natural fractures and their effects on shale oil accu-mulation in Junggar Basin, NW China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2022, 254, 103973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, E.; Aldega, L.; Bigi, S.; Corrado, S.; D’Ambrogi, C.; Mohammadi, P.; Shaban, A.; Sherkati, S. Control of Cambrian evaporites on fracturing in fault-related anticlines in the Zagros fold-and-thrust belt. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2013, 102, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, E.; Aldega, L.; Trippetta, F.; Shaban, A.; Narimani, H.; Sherkati, S. Control of folding and faulting on fracturing in the Zagros (Iran): The Kuh-e-Sarbalesh anticline. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 79, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercuri, M.; Tavani, S.; Aldega, L.; Trippetta, F.; Bigi, S.; Carminati, E. Are open-source aerial images useful for fracture network characterisation? Insights from a multi-scale approach in the Zagros Mts. J. Struct. Geol. 2023, 171, 104866. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.C.; Bhattacharya, S. Natural fracture mapping and discrete fracture network modeling of Wolfcamp formation in hydraulic fracturing test site phase 1 area, Midland Basin: Fractures from 3D seismic data, image log, and core. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 157, 106474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhubl, P.; Boles, J.R. Focused Fluid Flow along Faults in the Monterey Formation, Coastal California. GSA Bull. 2000, 112, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; He, S.; He, Z.L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, M.L. Genesis of calcite vein its implication to petroleum preservation in Jingshan region, Mid-Yangtze. Oil Gas Geol. 2014, 35, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, S.R.; Cornford, C. Basin geofluids. Basin Res. 1995, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Dong, W.L. Evolution of Fluid Flow and Petroleum Accumulation in Overpressed Systems in Sedimentary Basins. Adv. Earth Sci. 2001, 16, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.J.; Liu, L.; Chi, Y.L.; Wang, D.P. The Basic Type and Drive Mechanism of Basinfluid. World Geol. 2000, 19, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, A.J.; Zhao, W.Z.; Hu, A.P.; She, M.; Chen, Y.N.; Wang, X.F. Major factors controlling the development of marine carbonate reservoirs. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, G.J.; Anantharaman, K.; Baker, B.J.; Li, M.; Reed, D.C.; Sheik, C.S. The microbiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vent plumes: Ecological and biogeographic linkages to seafloor and water column habitats. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Zhang, X.H.; Liu, L.H.; Yu, J.L.; Huang, K.K. Progress of research on carbonate diagenesis. Earth Sci. Front. 2010, 16, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Koeshidayatullah, A.; Corlett, H.; Stacey, J.; Swart, P.K.; Boyce, A.; Roberson, H.; Whitaker, F.; Hollis, C. Evaluating new fault-controlled hydrothermal dolomitization models: Insights from the Cambrian Dolomite, Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Sedimentology 2020, 67, 2945–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.G.; Mei, L.F.; Shen, C.B.; Liu, Z.Q. Response of Hydrocarbon Fluid Sourse to Tectonic Deformation in Multicycle Super-imposed Basin: Example from Palaeozoic and Mesozoic Marine Strata in Yangtze Block. Earth Sci.—J. China Univ. Geosci. 2002, 37, 526–534. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Azmy, K.; He, Z.; Li, S.J.; Liu, E.T.; Wu, S.T.; Wang, J.B.; Li, T.Y.; Gao, J. Fault-controlled hydrothermal dolomitization of Middle Permian in southeastern Sichuan Basin, SW China, and its temporal relationship with the Emeishan Large Igneous Province: New insights from multi-geochemical proxies and carbonate U–Pb dating. Sediment. Geol. 2022, 439, 106215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaubien, S.E.; Schirripa Spagnolo, G.; Ridolfi, R.M.; Aldega, L.; Antoncecchi, I.; Bigi, S.; Billi, A.; Carminati, E. Structural control of gas migration pathways in the hydrocarbon-rich Val d’Agri basin (Southern Apennines, Italy). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 154, 106339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, S.; Zhang, B.Q.; He, Z.L.; Chen, M.F.; Li, T.Y.; Gao, J. Characteristics of paleo-temperature and palep-pressure of fluid inclusions in shale composite veins of Longmaxi Formation at the western margin of Jiaoshiba anticline. Acta Pet. Sin. 2018, 39, 402–415. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.W.; Chen, J.X.; Yuan, S.Q.; He, S.; Zhao, J.X. Constraint of in-situ calcite U-Pb dating by laser ablation on geochronology of hydrocarbon accumulation in petroliferous basins: A case study of Dongying sag in the Bohai Bay Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2020, 41, 284–291. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Z.C.; He, S.; Zhao, Y.Q.; Guo, X.W.; Liu, Y.L.; Chen, J.X.; Zhao, J.X. U-Pb Dating of Calcite Veins Developed in the Middle-Lower Ordovician Reservoirs in Tahe Oilfield and Its Petroleum Geologic Significance in Tahe Oilfield. Earth Sci. 2021, 46, 3203–3216. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.F.; Jiang, W.; Wu, K.J.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.K.; Chen, S.J.; Ran, T. Sedimentation mechanism and petroleum significanceof calcareous cements in continental clastic rocks. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2016, 38, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Jin, Z.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y. Improved understanding of petroleum migration history in the Hongche fault zone, northwestern Junggar Basin (northwest China): Constrained by vein-calcite fluid inclusions and trace elements. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2010, 27, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.D. Stable isotopes and limestone lithification. J. Geol. Soc. 1977, 133, 637–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.R.; Smith, L.B. Structurally controlled hydrothermal dolomite reservoir facies: An overview. AAPG Bull. 2006, 90, 1641–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, B.E.; Smith, L.B. Outcrop analog for Trenton–Black River hydrothermal dolomite reservoirs, Mohawk Valley, New York. AAPG Bull. 2002, 86, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wen, H.G.; Wang, X.; Wen, L.; Shen, A.J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, Q.Q.; She, M.; Ma, C.; Qiao, Z.F.; et al. Formational stages of natural fractures revealed by U-Pb dating and CO-Sr-Nd isotopes of dolomites in the Ediacaran Dengying Formation, Sichuan Basin, southwest China. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2024, 136, 4671–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M. Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks: Influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 1989, 21, 169–200. [Google Scholar]

- Banner, J.L.; Hanson, G.N. Calculation of simultaneous isotopic and trace element variations during water-rock interaction with applications to carbonate diagenesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 3123–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriga, G.; Marchegiano, M.; Peral, M.; Hu, H.M.; Cosentino, D.; Shen, C.C.; Dalton, H.; Brilli, M.; Aldega, L.; Claeys, P.; et al. Long-Term Tectono-Stratigraphic Evolution of a Propagating Rift System, L’Aquila Intermontane Basin (Central Apennines). Tectonics 2024, 43, e2024TC008548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, R.; Salih, N.; Préat, A. Direct Dating of Natural Fracturing System in the Jurassic Source Rocks, NE-Iraq: Age Constraint on Multi Fracture-Filling Cements and Fractures Associated with Hydrocarbon Phases/Migration Utilizing LA ICP MS. Minerals 2025, 15, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Chang, B.; Liu, Y.F.; Tan, J.Q. Thermal History of the Northwestern Junggar Basin: Constraints From Clumped Isotope Thermometry of Calcite Cement, Organic Maturity and Forward Thermal Modelling. Basin Res. 2025, 37, 370060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, J.D.; Hergt, J.; Meffre, S.; Large, R.R.; Danyushevsky, L.; Gilbert, S. In situ Pb-isotope analysis of pyrite by laser ablation (multi-collector and quadrupole) ICPMS. Chem. Geol. 2009, 262, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, J.D.; Horstwood, M.S.; Cottle, J.M. Advances in isotope ratio determination by LA–ICP–MS. Elements 2016, 12, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Zhou, T.F. Minerals in-situ LA-ICPMS trace elements study and the applications in ore deposit genesis and exploration. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 3437–3452. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Y.; Ge, C.; Ning, S.Y.; Nie, L.Q.; Zhong, G.X.; White, N.C. A new approach to LA-ICP-MS mapping and application in geology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2017, 33, 3422–3436. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.M.; Walker, R.J. U-Pb gechronology of calcite-mineralized faults: Absolute timing of rift-related fault events on the northeast Atlantic margin. Geology 2016, 44, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.L.; Zeng, Q.D.; Sun, G.T.; Duan, X.X.; Bonetti, C.; Riegler, T.; Long, D.G.; Kamber, B. Laser AblationInductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) elemental mapping and its applications in ore geology. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2019, 35, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.H.; Wu, F.Y.; Xie, L.W.; Yang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.B. In-situ Sr isotopic measurement of natural geological samples by LA-MC-ICP-MS. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2009, 25, 3431–3441. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.L.; Gao, S.; Dai, M.N.; Zong, C.L.; Li, R.X. In Situ Strontium Isotope Analysis of Fluid Inclusion Using LA-MC-ICPMS. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2009, 28, 313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.X.; Liu, Y.Q.; Jiao, X.; Zhou, D.W. Deep-derived clastics with porphyroclastic structure in lacustrine fine-grained sediments: Case study of the Permian Lucaogou Formation in Jimsar Sag, Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2020, 31, 220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Z.D. A laser-based microanalytical method for the in situ determination of oxygen isotope ratios of silicates and oxides. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.M.; Lu, X.; Gao, B.; Hong, S.X.; Pan, H.F.; Xu, Z.Y.; Bai, X.J. Geochemical analyzing technique of the microzone’s normal position and its application: A case study on the diagenetic evolution of the carbonate reservoir in Gucheng area. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2019, 38, 160–168. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzson, B.; Zeeman, M.J.; Zahniser, M.S.; Emmenegger, L. Quantum cascade laser based spectrometer for in situ stable carbon dioxide isotope measurements. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2008, 51, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, B.X.; Tang, G.Q.; Gao, B.Y.; Wu, S.T.; Li, J. Olivine, clinopyroxene and orthopyroxene reference materials for Li and O isotope in-situ microanalyses and trace element compositions. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2020, 36, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.T.; Chen, H.D.; Xu, F.Y. Geochemistry and dolomitization mechanism of Majiagou dolomites in Ordovician, Ordos, China. Acta Petrol. Sinica 2011, 27, 2230–2238. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.H.; Li, C.Q.; Zhang, X.M.; Chen, H.C.; Lin, Z.M. Using fluid inclusions to determine the stages and main phase of hydrocarbon accumulation in the Tahe oilfield. Earth Sci. Front. 2003, 10, 190. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.Z.; Chen, H.H.; Li, J.; Hu, G.Y.; Shan, X.Q. Using Fluid Inclusion of Reservoir to Deter Hydrocarbon Charging Orders and Times in the Upper Paleozoic of Ordos Basin. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2005, 24, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, X.M.; Liu, Z.F.; Liu, D.H.; Mi, J.K.; Shen, J.G.; Song, Z.G. Using reservoir fluid inclusion data to study the timing of natural gas reservoir formation. Sci. Bull. 2002, 47, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Tao, S.Z.; Zhang, Y.Y. Timing of lithostratigraphic hydrocarbon accumulation in southern Songliao Basin and its exploration implications. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini, B.; Tavani, S.; Mercuri, M.; Mondillo, N.; Pizzati, M.; Balsamo, F.; Aldega, L.; Carminati, E. Structural control on the alteration and fluid flow in the lithocap of the Allumi-ere-Tolfa epithermal system. J. Struct. Geol. 2024, 179, 105035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berio, L.R.; Balsamo, F.; Lucca, A.; Pizzati, M.; Storti, F.; Aldega, L.; Cipriani, A.; Lugli, F.; Mantovani, L.; Moretto, V.; et al. Hydrothermal silicification and active extensional faulting: Insights from the Kor-nos-Aghios Ioannis fault, Lemnos Island, Greece. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025, 137, 4015–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J. Introduction to aqueous-electrolyte fluid inclusions. In Fluid Inclusions: Analysis and Interpretation; Samson, I., Anderson, A., Marshall, D., Eds.; Mineralogical Association of Canada: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2003; Volume 32, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, R.H.; Reynolds, T.J. Fluid inclusion microthermometry. In Systematics of Fluid Inclusions in Diagenetic Minerals; Goldstein, R.H., Ed.; SEPM Short Course: Tulsa, OK, USA, 1994; Volume 31, pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.Y.; Bourdet, J.; Zhang, B.S.; Zhang, N.; Lu, X.S.; Liu, S.B.; Pang, H.; Li, Z.; Guo, X.W. Hydrocarbon charge history of the Tazhong Ordovician reservoirs, Tarim Basin as revealed from an integrated fluid inclusion study. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.F.; Gu, M.W.; Zhang, F.F.; Zhang, L.C.; Xiao, D.S. Hydrocarbon accumulation stages and type division of Shahezi Fm tight glutenite gas reservoirs in the Xujiaweizi Fault Depression, Songliao Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2017, 37, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, G.X.; Li, L.Q.; Sun, Y.M. Theory and Application of Fluid Inclusion Research on the Sedimentary Basins. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2006, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.D.; Zhang, C.; Pan, Z.K.; Huang, Z.X.; Luo, Q.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Z.X. Natural fractures in carbonate-rich tight oil reservoirs from the Permian Lucaogou Formation, southern Junggar Basin, NW China: Insights from fluid inclusion microthermometry and isotopic geochemistry. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 119, 104500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Z. Hydrocarbon inclusion analysis: Application in geochronological study of hydrocarbon accumulation. Geol.-Geochem. 2002, 30, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarelli, V.; Aldega, L.; Corrado, S.; Invernizzi, C.; Casas-Sainz, A. Thermal history of the Aragón-Béarn basin (Late Paleozoic, western Pyrenees, Spain); Insights into basin tectonic evolution. Ital. J. Geosci. 2013, 132, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Chen, H.H.; Zhao, Y.C.; Liu, J.Z.; Chen, L. Using Fluid Inclusions of Reservoir to Determine Hydrocarbon Charging Orders and Times in the Upper Paleozoic in Tabamiao Block, Ordos Basin. Geoscience 2007, 21, 712–718+737. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, G.X.; Lu, H.Z. Validation and representation of fluid inclusion microthermometric data using the fluid inclusion assemblage (FIA) concept. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2008, 24, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Kong, X.Y.; Wang, Q.Q.; She, M.; Liang, F.; Dong, Y.X.; Xu, H.; He, J.H.; Chen, H.D. Mechanisms of bedding fracturing in the Junggar Basin, northwest China: Constraints from in situ U-Pb dating and CO-Nd isotopic analysis of calcite cements. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025, 137, 2027–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Wang, J.; Tao, C.; Hu, G.; Lu, L.F.; Wang, P. The Geochronology of Petroleum Accumulation of China Marine Sequence. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2013, 24, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mark, D.F.; Parnell, J.; Kelley, S.P.; Lee, M.; Sherlock, S.C.; Carr, A. Dating of multistage fluid flow in sandstones. Science 2005, 309, 2048–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.Y.; He, P.; Zhang, S.C.; Zhao, M.J.; Lei, J.J. The K-Ar Isotopic dating of authigenic illites and timing of hydrocarbon fluid emplacement in sandstone reservoir. Geol. Rev. 1997, 43, 540–546. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal, I.T.; Golding, S.D.; Thiede, D.S. K–Ar and Rb–Sr dating of authigenic illite–smectite in Late Permian coal measures, Queensland, Australia: Implication for thermal history. Chem. Geol. 2001, 171, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zwingmann, H.; Todd, A.; Liu, K.Y.; Luo, X.Q. K-Ar dating of authigenic illite and its applications to study of oil-gas charging histories of typical sandstone reservoirs, Tarim basin, Northwest China. Earth Sci. Front. 2004, 11, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Zwingmann, H.; Liu, K.Y.; Luo, X.Q. Perspective on the K/Ar and Ar/Ar geochronology of authigenic illites: A case study from the Sulige gas field, Ordos Basin, China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2014, 35, 407–416. [Google Scholar]

- Del Sole, L.; Viola, G.; Aldega, L.; Moretto, V.; Xie, R.; Cantelli, L.; Vignaroli, G. High-resolution investigations of fault architecture in space and time. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccari, C.; Mazzarini, F.; Tavarnelli, E.; Viola, G.; Aldega, L.; Moretto, V.; Xie, R.; Musumeci, G. How brittle detachments form and evolve through space and time. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2024, 648, 119108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldega, L.; Viola, G.; Casas-Sainz, A.; Marcén, M.; Román-Berdiel, T.; Lelij, R. Unraveling multiple thermo-tectonic events accommodated by crustal-scale faults in northern Iberia, Spain: Insights from K-Ar dating of clay gouges. Tectonics 2019, 38, 3629–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.B.; Huang, Z.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Chen, J.; Han, R.S.; Xu, C.; Guan, T.; Yin, M.D. Age of the Giant Huize Zn-Pb Deposits Determiner by Sm-Nd Dating of Hydrothermal Calcite. Geol. Rev. 2004, 50, 189–195. [Google Scholar]

- Moorbath, S.; Taylor, P.N.; Orpen, J.L.; Treloar, P.; Wilson, J.F. First direct radiometric dating of Archaean stromatolitic limestone. Nature 1987, 326, 865–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.E.; Farquhar, R.M.; Hancock, R.G. Direct radiometric age determination of carbonate diagenesis using U-Pb in secondary calcite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1991, 105, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzi, M.; Viola, G.; Zuccari, C.; Aldega, L.; Billi, A.; Lelij, R.; Kylander-Clark, A.; Vignaroli, G. Tectonic evolution of the Eastern Southern Alps (Italy): A reappraisal from new structural data and geochronological constraints. Tectonics 2024, 43, e2023TC008013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, S.; Smeraglia, L.; Fabbi, S.; Aldega, L.; Sabbatino, M.; Cardello, G.L.; Maresca, A.; Spagnolo, G.S.; Kylander-Clark, A.; Billi, A.; et al. Timing, thrusting mode, and negative inversion along the Circeo thrust, Apennines, Italy: How the accretion-to-extension transition operated during slab rollback. Tectonics 2023, 42, e2022TC007679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzi, M.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Billi, A.; Boschi, C.; Aldega, L.; Franchini, S.; Albert, R.; Gerdes, A.; Barberio, M.D.; Looser, N.; et al. U-Pb age of the 2016 Amatrice earthquake causative fault (Mt. Gorzano, Italy) and paleo-fluid circulation during seismic cycles inferred from inter- and co-seismic calcite. Tectonophysics 2021, 819, 229076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.T.; Zhao, J.X.; Pan, S.Q.; Yan, D.T.; Lu, J.; Hao, S.B.; Gong, Y.; Zou, K. A New Technology of Basin Fluid Geochronology: In-Situ U-Pb Dating of Calcite. Earth Sci. 2019, 44, 698–712. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhead, J.D.; Pickering, R. Beyond 500 ka: Progress and prospects in the U-Pb chronology of speleothems, and their application to studies in palaeoclimate, human evolution, biodiversity and tectonics. Chem. Geol. 2012, 322, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.J.; Zhu, D.Y.; Meng, Q.Q.; Hu, W.X. Hydrothermal activites and influences on migration of oil and gas in Tarim Basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2013, 29, 1045–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Parrish, R.R.; Horstwood, M.S.A.; McArthur, J.M. U–Pb dating of cements in Mesozoic ammonites. Chem. Geol. 2014, 376, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; VanderWal, J.; Roberts, N.M.W.; Winkelstern, I.Z.; Faithfull, J.W.; Boyce, A.J. Fingerprinting fluid source in calcite veins: Combining LA-ICP-MS U-Pb calcite dating with trace elements and clumped isotope palaeothermometry. Tektonika 2024, 2, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhu, D.Y.; Luo, Q.; Liu, L.F.; Liu, D.D.; Yan, L.; Zhang, Y.Z. Major factors controlling fracture development in the Middle Permian Lucaogou Formation tight oil reservoir, Junggar Basin, NW China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 146, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, D.D.; Liu, Q.Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.W.; Ma, C.; Wu, A.B.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Y.Q. Magmatism and hydrocarbon accumulation in sedimen tary basins: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 244, 104531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, Y.X.; Wang, Q.Q.; Liu, D.D.; She, M.; Luo, Q.; Dong, X.P.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, H.D.; Lu, F.F. Coupled formation of fracture assemblages in shale and their influence on permeability. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.Q.; Ren, K.X.; Hui, Q.N.; Liang, Y.L.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, H.L.; Wang, M.Y.; Lu, F.F. Role of Natural Fractures in Fluid Migration within Pore-Developed Dolomite. J. Geol. Soc. 2025, 186, jgs2024-234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Kong, X.Y.; Jiang, Z.X.; Song, Y.; Dong, Y.X.; Luo, Q.; Song, K.H.; Zhang, K.; Lu, F.F. What Controls Oil Saturation in Fractures? J. Earth Sci. 2025, 36, 1315–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.T.; Wang, Y.Q.; Liu, J.Q.; Li, M.X. Evaluation of Carbon Emission Efficiency and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Chinese Oil and Gas Enterprises. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1156–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.Q.; Kong, X.Y.; Gao, B.; Liu, J.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Chen, H.D. A Comprehensive Fracture Characterization Method for Shale Reservoirs. Pet. Sci. 2025, 22, 2660–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z. Natural Fracturing in Marine Shales: From Qualitative to Quantitative Approaches. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2026, 14, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010099

Zhang C, Huang Y, Chen H, Hu Z. Natural Fracturing in Marine Shales: From Qualitative to Quantitative Approaches. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2026; 14(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chen, Yuhan Huang, Huadong Chen, and Zongquan Hu. 2026. "Natural Fracturing in Marine Shales: From Qualitative to Quantitative Approaches" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 14, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010099

APA StyleZhang, C., Huang, Y., Chen, H., & Hu, Z. (2026). Natural Fracturing in Marine Shales: From Qualitative to Quantitative Approaches. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 14(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse14010099