1. Introduction

The deep sea contains abundant resources and life codes, acting as a strategic new frontier that humans have not yet fully explored. Since the rise of AUVs in the 1960s, they have been widely applied in fields such as deep-sea resource exploration, military reconnaissance, and pipeline inspection, owing to their autonomy and concealment advantages [

1,

2,

3]. Currently, there are obvious limitations regarding the endurance of commercial AUVs. For example, REMUS-600S (USA): 24 h of operation at 4.5 kn; MT-88 (Russia): 6 h of operation at 2 kn; Hugin 1000 (Norway): 20 h of operation at 2 kn; Deep C (Germany): up to 60 h of operation at 1 kn; Qianlong-1 (China): 30 h of operation at 2 kn; and Naga AUV (China): improved to 42 h of operation at 2 kn [

4,

5]. Generally, their endurance does not exceed 60 h, which makes it difficult to meet the needs of long-term observation.

To break through the endurance bottleneck, research institutions worldwide have conducted studies on docking-station-based residency technology. Examples include the U.S.-developed Odyssey-II, REMUS, and Bluefin systems, as well as research efforts by the Shenyang Institute of Automation Chinese Academy of Sciences, Zhejiang University, and Harbin Engineering University in China. However, this type of technology requires the development of dedicated docking stations, resulting in a complex system and high costs [

6,

7,

8]. In 1992, the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) first proposed the AUV bottom-landing residency technology and initiated the earliest research on this technology. This technology enables long-term bottom-landing residency and survey operations with lower control efforts, and extremely low energy consumption. The first developed bottom-landing residency platform (NPS AUV) [

9] ultimately completed marine trials. This AUV was equipped with one ballast tank each at its bow and stern; downward driving force was obtained by filling these tanks with water. During the process of descending to the seabed, vertical duct thrusters were used to assist in manipulating the rudders, adjusting the AUV’s speed and attitude to ensure it landed softly on the seabed at a low speed. During the bottom-landing period, the power system was shut down, and long-term residency observation tasks were performed at key target sites. After the mission, ballast must be jettisoned for rapid ascent to conclude the operation. A single dive only allows for one bottom-landing event, and the AUV must ascend nearby immediately after bottom-landing, making it unable to carry out a covert mission. During the bottom-landing period, the bottom of the AUV is in direct contact with the seabed; affected by seabed sediment, the bottom-mounted detection equipment is vulnerable to damage. Additionally, the adsorption force of seabed sediment poses significant safety risks.

In 1998, Florida Atlantic University (USA) developed the ANS AUV-Magellan [

10] and conducted marine trials. Its bottom-landing method still relied on filling ballast tanks with water to provide driving force. After completing bottom-landing residency and observation, high-pressure gas from on-board high-pressure cylinders was released to blow water out of the ballast tanks, enabling bottom-leaving. This solution achieves bottom-landing and bottom-leaving by changing the platform’s displaced weight. It can restore buoyancy by blowing seawater out with high-pressure cylinders. However, during the bottom-landing period, the bottom of the AUV is in direct contact with the seabed. Affected by seabed sediment, the bottom-mounted detection equipment is prone to damage, and the adsorption force of seabed sediment poses certain safety risks.

In 2000, Florida Atlantic University (USA) modified the Ocean Explorer Ⅱ AUV for acoustic detection [

11]. This AUV controlled the slow release of bottom-landing driving force by exhausting air from a pre-inflated airbag, enabling soft landing followed by bottom-landing residency for acoustic monitoring. When ascent was required, high-pressure gas cylinders were activated to inflate the airbag, providing driving force for bottom-leaving and ascent. Meanwhile, the airbag-driven mechanism presents significant implementation challenges under the high-pressure conditions of deep water.

Mehul Sangekar, a researcher from the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), developed an AUV capable of obtaining measurement data with micron-level resolution through bottom-landing observation [

12]. For bottom-landing, this AUV uses rigid fixed brackets installed at its bottom for support. It is configured with slight negative buoyancy and paired with vertical duct thrusters to achieve bottom-landing and bottom-leaving operations. During bottom-landing, the AUV’s bottom-mounted brackets contact the seabed, protecting the bottom-mounted detection equipment from damage and minimizing safety risks. The system is simple and reliable but is of a relatively large size.

Webb Research Corporation (USA) optimized the gliding and bottom-landing characteristics of underwater gliders with different configurations, and finally proposed a new disk-shaped underwater glider (Discus Glider) [

13]. Gliding lift is provided by a gliding wing—installed at the stern and shaped like an aircraft wing—while driving buoyancy is supplied by a micro buoyancy adjustment mechanism. Tests to verify gliding and bottom-landing performance were conducted in both pool and shallow-sea environment. This research provides a reference solution for the subsequent development of bottom-landing residency observation using gliders.

Wei Hou and Hongwei Zhang from Tianjin University (China), along with their team, developed a prototype AUV-VBS that achieves bottom-landing driven by gravity adjustment. In September 2005, this prototype completed lake trials, realizing fixed-point bottom-landing residency and long-term reconnaissance and detection.

Two long cylindrical ballast tanks are symmetrically arranged on the left and right sides of the AUV’s bottom. A hydraulic system drives the water injection valves at both ends of the tanks, allowing control over the water injection rate and volume to regulate different bottom-landing speeds and forces. After completing the bottom-landing mission, the suspension device of the ballast tanks is disconnected and released by fusing wires [

14,

15,

16,

17]. This solution only enables one bottom-landing event per dive; after bottom-landing, the AUV must ascend nearby immediately, making it unable to carry out covert missions.

Zhe Wu from the 715th Research Institute of China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) integrated and installed a set of hydraulically driven four retractable hydraulic cylinder legs on an AUV platform with a diameter of 324 mm [

18]. As shown in hydraulic cylinder support scheme (

Figure 1), the hydraulic system drives the cylinders to extend the legs for supporting bottom-landing. During the period of bottom-landing, the support plates at the ends of the legs come into contact with seabed sediment. The bottom-landing driving force is achieved by configuring the AUV in a negative buoyancy state; after completing the bottom-landing mission, ballast is jettisoned for rapid ascent. This solution only allows for one bottom-landing event per dive; after bottom-leaving, the AUV must ascend nearby immediately, making it unable to carry out covert missions.

Baowei Song and his team from Northwestern Polytechnical University (NPU, China) designed a hydraulic system capable of driving a three-stage hydraulic cylinder leg mechanism. As shown in three-stage hydraulic cylinder support scheme (

Figure 2). They completed the principal design, parameter calculation, equipment selection, and 3D detailed design of the support mechanism [

19]. Baowei Song and his colleagues also proposed an anchor chain-based bottom-landing scheme [

20]. The driving force for bottom-landing comes from the AUV’s negative buoyancy. Two weights are suspended at the bow and stern positions of the AUV’s bottom, as shown in the working schematic diagram (

Figure 3).

Other types of submersibles with bottom-landing capabilities mainly include Human Occupied Vehicles (HOVs) and Autonomous Remotely Operated Vehicles (ARVs). HOVs primarily achieve unpowered descent using jettisonable ballast. Upon reaching the predetermined depth, they jettison the ballast and adjust their state to slight negative buoyancy via a water suction/drainage buoyancy adjustment mechanism before navigating. When arriving at the intended operation site, they achieve stable bottom-landing operations by combining vertical thrusters with more slight negative buoyancy; after completion, they depart from the seabed using vertical thrusters. Typical representative HOVs include China’s HOV “

Jiaolong”, HOV “

Shenhai Yongshi”, and HOV “

Fendouzhe” [

21]. The bottom-landing process of ARVs [

22,

23] involves trimming the ARV to a near-zero buoyancy state first, then navigating to the operation site either autonomously or remotely. During the bottom-landing process, vertical thrusters first provide driving force, and four horseshoe-shaped legs at the ARV’s bottom act as supports to achieve stable landing.

Addressing the limitations of existing technologies, this study develops a bottom-landing system that combines variable buoyancy adjustment with a telescopic bottom-landing mechanism. Verification via pool, lake, and sea tests has demonstrated favorable results. This study makes four distinct original contributions to the field of underwater bottom-landing technology, with significant academic innovation and engineering application value:

An integrated bottom-landing scheme is innovatively proposed. This design breaks through the limitations of single-support or single-buoyancy control systems, realizing flexible and stable posture adjustment during the landing process; a targeted design strategy for dual seabed types is developed, incorporating impact suppression technology for hard seabeds and adsorption control technology for soft seabeds. This solves the key adaptability problem of underwater equipment facing heterogeneous seabed environments, significantly improving landing reliability in complex marine geological conditions. The universal bottom-landing criterion and attitude self-adjustment strategy for both flat and uneven seabeds are established. This fills the gap of lacking a unified theoretical framework for diverse seabed topographies, enhancing the system’s robustness and environmental adaptability through active attitude correction. The function of multi-site covert residency with low energy consumption is achieved, which innovatively balances long-duration operation and stealth performance. This expands the application scenarios of underwater equipment in marine resource exploration, environmental monitoring, and other fields, providing a new technical path for energy-saving and multi-task coverage operations.

These contributions systematically address the core challenges of adaptability, stability, universality, and energy efficiency in underwater bottom-landing technology, providing important theoretical support and technical reference for the development and engineering application of advanced underwater systems.

2. Variable Buoyancy-Driven Telescopic Retention and Bottom-Landing Technology

Based on the current research status, this study focuses on the core technical bottlenecks of long-term bottom-landing and retention, and conducts research on four key technologies: the matching of bottom-landing driving force, the prediction and protection of bottom-landing impact force on hard seabeds, the prediction and suppression of bottom-leaving adsorption force on soft seabeds [

24,

25], and the control strategy for bottom-landing and bottom-leaving. Based on the research results of the key technologies, this study proposes to adopt the drive of a variable buoyancy adjustment mechanism, supplemented by the support of a telescopic bottom-landing mechanism, and combine the corresponding control strategy to complete the research on the autonomous bottom-landing technology of deep-sea AUVs. Finally, the application tests in water tanks, lakes, and seas will be completed.

2.1. Research on Bottom-Landing Driving Force Matching

When an AUV conducts seabed-tracking surveys, it is necessary to adjust the platform to zero-buoyancy cruising. To implement the technical scheme of multi-site reciprocating operations including bottom-landing, bottom-leaving, and cruising, this paper selects a variable buoyancy adjustment mechanism as the output and recovery mechanism for the driving force of bottom-landing and bottom-leaving. Different bottom-landing forces will result in different bottom-landing speeds, which will in turn generate impact responses on rigid substrates. This section focuses on carrying out prediction research on the AUV’s diving and bottom-landing processes under different attitudes and with different bottom-landing driving forces, respectively.

2.1.1. The Influence of Pitch Angle on Driving Force

The curves showing the relationship between driving force and velocity under the condition of zero roll angle and different pitch angles are presented in the figure below (

Figure 4). The horizontal axis represents the bottom-landing velocity (V

L), with the unit of kn. The vertical axis represents the bottom-landing driving force (F

L), with the unit of N.

Analysis from the figure shows that at the same velocity, the maximum driving force is required when both the roll angle and pitch angle are zero. Conversely, under the condition of the same driving force, the bottom-landing velocity is the smallest when there is zero roll angle and zero pitch angle. However, from the results, it is not true that a larger angle leads to a higher velocity; there exists a certain abnormal trend. This is because the AUV is equipped with a large number of bottom detection devices, which cause significant damage to its hull lines. When the AUV dives at different pitch angles and different velocities, local eddy currents are formed, complicating the local flow field and resulting in increased driving force.

2.1.2. The Influence of Roll Angle on Driving Force

The curves showing the relationship between driving force and velocity under the condition of zero pitch angle and different roll angles are presented in the figure below (

Figure 5). The horizontal axis represents the bottom-landing velocity (

VL), with the unit of kn. The vertical axis represents the bottom-landing driving force (

FL), with the unit of N.

Analysis from the figure reveals that at the same velocity, the maximum driving force is required when both the roll angle and pitch angle are zero. Conversely, under the condition of the same driving force, the bottom-landing velocity is the smallest when both the roll angle and pitch angle are zero. For further analysis, as the roll angle increases, the flow-facing area of the bottom-landing plate decreases, leading to a slight reduction in driving force. Generally, the roll angle of an AUV can be eliminated through trimming, and it can usually be easily controlled within 0.5°, with its impact on the driving force being negligible. Comprehensive analysis indicates that the core of attitude control should focus on the optimization and regulation of the pitch angle.

2.2. Research on Prediction and Protection of Bottom-Landing Impact Force on Hard Seabed

When an AUV conducts bottom-landing operations in the deep-sea environment, it inevitably needs to make contact with the deep-sea seabed sediment. The sediment types can be divided into two categories. One is the hard sediment of the rock type. For bottom-landing under such environmental conditions, it is necessary to fully consider the collision impact under different driving forces and different attitude conditions. At the same time, research should be carried out on the self-locking performance and collision strength of the bottom-landing mechanism to ensure the safe realization of the AUV’s bottom-landing process. The other sediment type is soft sediment. For this type, it is necessary to predict the bottom-leaving adsorption force, evaluate the safety of bottom-leaving, and ensure the safe implementation of the AUV’s bottom-leaving process.

According to the classical theoretical analysis model [

26], there is a linear relationship between the bottom-landing movement velocity of an AUV and the force acting on its body.

where

is the linear theoretical force of the bottom-landing mechanism,

is the stiffness coefficient of the hard rock sediment, and

is the vertical movement velocity of the AUV at the contact position. The stiffness coefficient can be calculated using the following formula [

26],

where

is the average compressive elastic coefficient of the hard rock sediment environment, and

is the contact area between the bottom-landing mechanism and the seabed. The magnitude of

is determined by factors such as the elastic modulus of the seabed sediment environment and the geometric shape of the contact area [

26].

where

is the shape factor of the contact surface, with a value range of 1~2, and the value used in the calculation of this paper is 1.25.

is the elastic modulus of the hard rock sediment, with a value of 105 MPa used in this paper;

is Poisson’s ratio of the hard rock sediment, with a value of 0.18 used in the calculation of this paper. After substituting Equation (3) into Equation (2) and rearranging the formula, we can obtain,

A tubular bottom-landing support is installed at the bottom of the “

Jiaolong” submersible, with a contact area of approximately 50 mm

2. The bottom-landing legs of the “

Shenhai Yongshi” and “

Fendouzhe” submersibles adopt a design integrated with their hull lines, resulting in a significantly larger bottom-landing contact area compared to the “

Jiaolong”. The total area of the four horseshoe-shaped bottom-landing legs at the bottom of the “

Haidou-1” ARV is 90,792 mm

2. The design of the bottom-landing contact area at the bottom of the AUV refers to the above-mentioned designs, and its size should be no smaller than the above values as much as possible. An excessively small bottom-landing contact area will increase the risk of subsidence and, at the same time, raise the design requirements for the structural impact strength when bottom-landing on hard sediment. The initial selected bottom-landing area of the AUV is 100,000 mm

2. Based on this initially selected design value, the preliminary calculated stiffness coefficient K

Z is 429 MN/m. The preliminary bottom-landing design scheme of the AUV is specifically shown in the figure below. It adopts two bow- and stern- supporting legs to achieve bottom-landing. As shown in the preliminary design scheme (

Figure 6). The preliminary designed planar area of the two bottom-landing plates is 100,000 mm

2, with each bottom-landing plate having an area of 50,000 mm

2.

To determine a reasonable bottom-landing driving force, the bottom-landing velocities under different driving force conditions were calculated separately. Substituting the obtained vertical velocity into Equation (1) yields the theoretical force. Similarly, the magnitude of the maximum equivalent stress of the simulated bottom-landing impact can be calculated using explicit dynamic analysis software. Taking the driving forces under different velocity conditions as the initial state, the landing support was made to impact the rock substratum at different pitch angles. The rock material has a density of 2650 Kg/m

3, a compressive strength of 180 MPa, and a tensile strength of 12 MPa; its Poisson’s ratio and elastic modulus are as described in the previous section. Through this process, the maximum equivalent stress under different bottom-landing velocities can be obtained. It should be noted that the setting of different pitch angles needs to be defined by establishing a local coordinate system; generally, selecting the

Z-axis direction of the local coordinate system as the impact movement direction is a commonly used setting. The main load-bearing components of the bottom-landing mechanism are made of TC4 titanium alloy, which has a yield strength of 825 MPa. The bilinear kinematic hardening criterion was adopted, with a tangent modulus of 82.5 MPa, an elastic modulus of 1.048 × 10

11 Pa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.31, and a density of 4428.78 Kg/m

3. After completing the impact calculation, the maximum equivalent stress was extracted, respectively. The specific calculation results are shown in the figure below (

Figure 7).

It can be observed from the figure that as the vertical velocity (velocity is proportional to the driving force) increases, the maximum equivalent stress of the bottom-landing impact increases. With the increase in the AUV’s pitch angle, the maximum equivalent stress of the bottom-landing impact increases significantly. Therefore, it is necessary to control the bottom-landing velocity and bottom-landing pitch angle; otherwise, when the AUV lands on a rigid substratum, it is likely to cause damage to the bottom-landing mechanism.

The TC4 material is selected for the design of the bottom-landing mechanism. As can be seen from the above figure, when the steady-state velocity is greater than 0.3 kn, the maximum equivalent stress caused by the impact increases at a relatively high rate, and the impact safety factor decreases significantly at this time. Therefore, it is reasonable to design the driving force corresponding to the range of 0.2 to 0.3 kn. The driving force under unsteady working conditions is calculated using hydrodynamic numerical analysis software (STAR1002), and the specific results are shown in the figure below (

Figure 8). It can be seen from the figure that designing the driving force of the variable buoyancy adjustment mechanism to be 30 N can well meet the requirements of the bottom-landing driving force. Taking the seawater density as 1.021 Kg/m

3, when the AUV lands at a velocity of 0.3 kn, the corresponding variable buoyancy is 32.9/9.8/1.021 L = 3.28 L. Therefore, the maximum oil displacement of the buoyancy adjustment mechanism in this paper should be designed to be no less than 3.3 L.

2.3. Study on Prediction and Suppression of Bottom-Leaving Adhesion Force for Soft Seabeds

Increasing the area of the bottom-landing plate can reduce the pressure on the bottom-landing contact surface and lower the risk of the bottom-landing plate sinking, but the adsorption force will increase accordingly. Conversely, reducing the area of the bottom-landing plate will increase the pressure on the contact surface, raise the risk of the bottom-landing plate sinking, and decrease the adsorption force correspondingly. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct research and prediction on the bottom-leaving adsorption force for bottom-landing plates of different shapes, so as to evaluate whether the AUV has the safe bottom-leaving driving capability.

For the condition of soft seabed sediment, the bottom-landing process is equivalent to a soft bottom-landing. There is no need to consider the impact response of the bottom-landing driving force during the bottom-landing process. This paper focuses on the research of the bottom-leaving driving force for soft sediment. When an AUV lands on the seabed, the bottom-landing plate at the bottom of the bottom-landing mechanism will contact the seabed sediment. When it needs to leave the seabed after the bottom-landing process is completed, it is necessary to overcome the adsorption force caused by the sediment. The causes of the adsorption force mainly consist of three aspects: first, the adhesion force of the soft sediment; second, the negative pore water pressure generated during the bottom-leaving process; and third, the lateral friction force generated on the side of the bottom-landing support structure.

According to the Skempton model [

27], the formula for calculating the bottom-leaving force required for the bottom-landing plate to leave the seabed is as follows:

where

is the lifting force under the ultimate bearing capacity of the sediment;

is the shear strength of the sediment;

is the horizontal projected contact area between the bottom-landing plate and the sediment;

is the immersion depth of the bottom-landing plate in the sediment;

is the width of the bottom-landing plate;

is the length of the bottom-landing plate;

is the underwater self-weight of the bottom-landing plate; and

is the weight of the sediment displaced by the bottom-landing plate immersed in the sediment (where

is the wet bulk density) [

27].

Since the additional force caused by the immersion depth D of the bottom-landing plate in the sediment is in the same direction as the lifting force, and the self-weight of the bottom-landing plate is in the opposite direction to the lifting force, substituting these into the lifting force calculation formula gives the following result: when the bottom-landing plate is immersed in the sediment, the theoretical adsorption force

exerted by the sediment on the bottom-landing plate is [

27],

First, it is assumed that the immersion depth

= 5 mm, and the variation relationship of the adsorption force under different length–width ratios of the bottom-landing plate is studied. The area of the bottom-landing plate is constrained to 101,086 mm

2, and the length and width of the bottom-landing plate are adjusted. The calculation results of the adsorption force corresponding to different

/

ratios are as described in the figure below (

Figure 9).

It can be concluded from the above figure that for a bottom-landing plate with the same area, the length-to-breadth ratio (L/B) is inversely correlated with the adsorption force. The ideal design dimension of the bottom-landing plate is the maximum / ratio, which corresponds to the minimum adsorption force. Moreover, when / is greater than 3, the reduction in adsorption force tends to slow down. Meanwhile, in order to reduce navigational drag, improve the maximum endurance of the AUV, and lower the difficulty of straight-line navigation control, it is necessary to enable the bottom-landing plate to retract into the hull line after completing the bottom-landing task. Considering the rotary body hull line characteristic of the AUV with a parallel middle section diameter of 800 mm, when / = 3.3125 is selected, the bottom-landing plate can be conveniently retracted into the hull line, and the increase in adsorption force is not significant when the / value is further increased.

Based on the bottom-landing experience of “

Haidou-1” and “

Wenhai-1” during their sea trials in the South China Sea, the settlement depth in the waters of the South China Sea generally does not exceed 100 mm. The dimension parameters of the bottom-landing plate are as follows:

= 101,086 mm

2,

= 397.5 mm, and

= 120 mm. Substitute these parameters into the above formula to calculate the sediment adsorption force, respectively, when the settlement depth ranges from 0 to 100 mm. It can be concluded from the diagram that the immersion depth of the bottom-landing structure is positively correlated with the adsorption force. As shown in the figure below (

Figure 10). However, when the immersion depth does not exceed 100 mm, the seabed maximum adsorption force is no more than 18.8 N. Therefore, according to the design of the current bottom-landing scheme, the safety of detaching from the seabed is relatively high.

2.4. Development of Variable Buoyancy Adjustment Mechanism

Based on the research results of the bottom-landing driving force, an oil suction/drainage buoyancy adjustment mechanism [

28,

29] is designed as the output and recovery mechanism for the deep-sea bottom-landing and bottom-leaving driving force. The system uses a high-pressure piston pump to drive the high-pressure oil, and a built-in ultrasonic sensor is adopted as the real-time liquid level detection sensor. The calculation formula for the driving torque of the buoyancy adjustment mechanism is as follows:

where

is the maximum output pressure difference, defined as the difference between the outlet pressure and the inlet pressure of the high-pressure piston pump, which can be understood as the maximum output pressure of the piston pump here.

V0 is the displacement of the high-pressure piston pump, and this parameter is one of the key selection parameters for hydraulic pumps.

is the hydraulic mechanical efficiency, and

= 0.95 in this paper. The calculation formula for the system flow rate is as follows:

where n is the rotational speed of the driving motor, which is also required not to exceed the allowable rotational speed of the hydraulic pump.

is the transmission efficiency of the motor-pump unit.

where

is the output efficiency of the motor, which can be obtained from the motor selection manual.

is the volumetric efficiency of the pump, which can also be obtained from the hydraulic pump selection manual. The motor power can be derived from the above two formulas.

where the unit of

is MPa, the unit of

is L/min,

is dimensionless, and the unit of

is KW. Based on the above theoretical calculation results, the following mechanism is designed (

Figure 11).

Based on the results of the overall optimization and design of the AUV, the buoyancy adjustment mechanism is installed near the metacenter of the AUV, so the oil suction and drainage process has little impact on the attitude of the AUV. The bladder for buoyancy adjustment is fixed directly above the center of buoyancy, while the mechanism body, which is relatively heavy, is arranged directly below the center of gravity. Through statics calculation, the change in the AUV’s own attitude before and after the oil suction and drainage is small. The theoretical value of the trim change is less than 0.15°, so the impact on the attitude can be ignored [

30], indicating that the design and layout are effective.

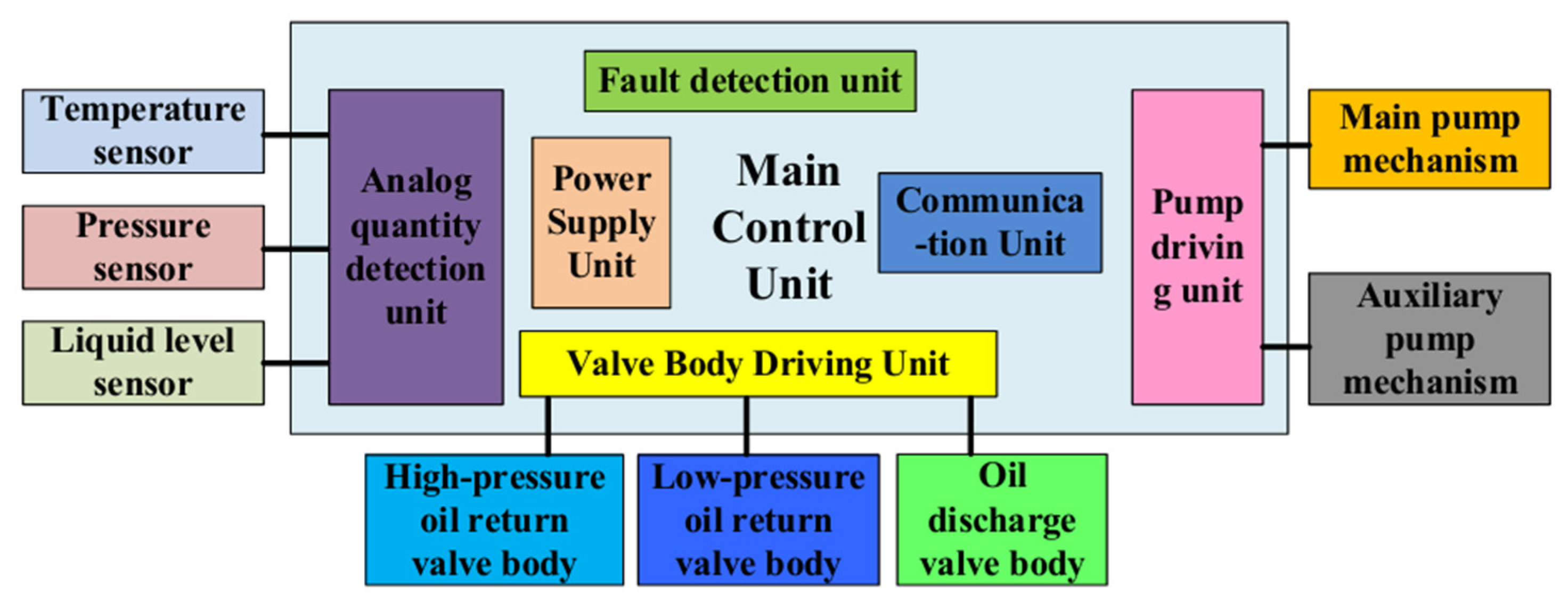

The composition of the buoyancy adjustment system is shown in the figure below (

Figure 12). The system mainly consists of a detection part (left part), a main control part (middle part), and a drive part (right part).

2.5. Development of “Biped” Telescopic Bottom-Landing Mechanism

Based on the research results on adsorption force, the designed area of the bottom-landing plates is optimized to 50,543 mm

2 (two plates), divided into bow and stern plates. The mechanism is designed as two sets of bow and stern parallel-acting components, and the whole is supported by a “biped” telescopic bottom-landing mechanism. According to the calculation results of the driving force for leaving off the seabed in the previous chapter, a T-shaped transmission thread screw pair is initially selected as the transmission pair of the telescopic mechanism. The nominal diameter of the driving screw is initially selected as

d = 16 mm. Since the mechanism needs to have strong self-locking force in the extended state, a single-start T-shaped screw is chosen in the design, with the pitch initially set as

P = 4 mm. To ensure that the mechanism itself has strong driving capability and attitude adjustment ability, the initial design value of the axial load of the thread pair is tentatively set at 10 Kg. The calculation formula for the rotational torque of the thread pair is as follows.

where

is the axial load, and

is the corrected sliding friction efficiency, which is taken as 0.4 in this paper. Substituting each known quantity into the above formula, we can achieve

= 0.16 Nm. Based on this torque, the selection of the drive motor can be completed. The design and physical diagram of the mechanism are shown in the figure below (

Figure 13).

To ensure the self-locking performance of the mechanism and improve the reliability of the mechanism when land on the seabed, a self-locking force test was conducted on the machined lead screw. Under the measured load condition of 10 Kg, the heavy object did not slide down along the thread, and the test effect is shown in the figure below (

Figure 14).

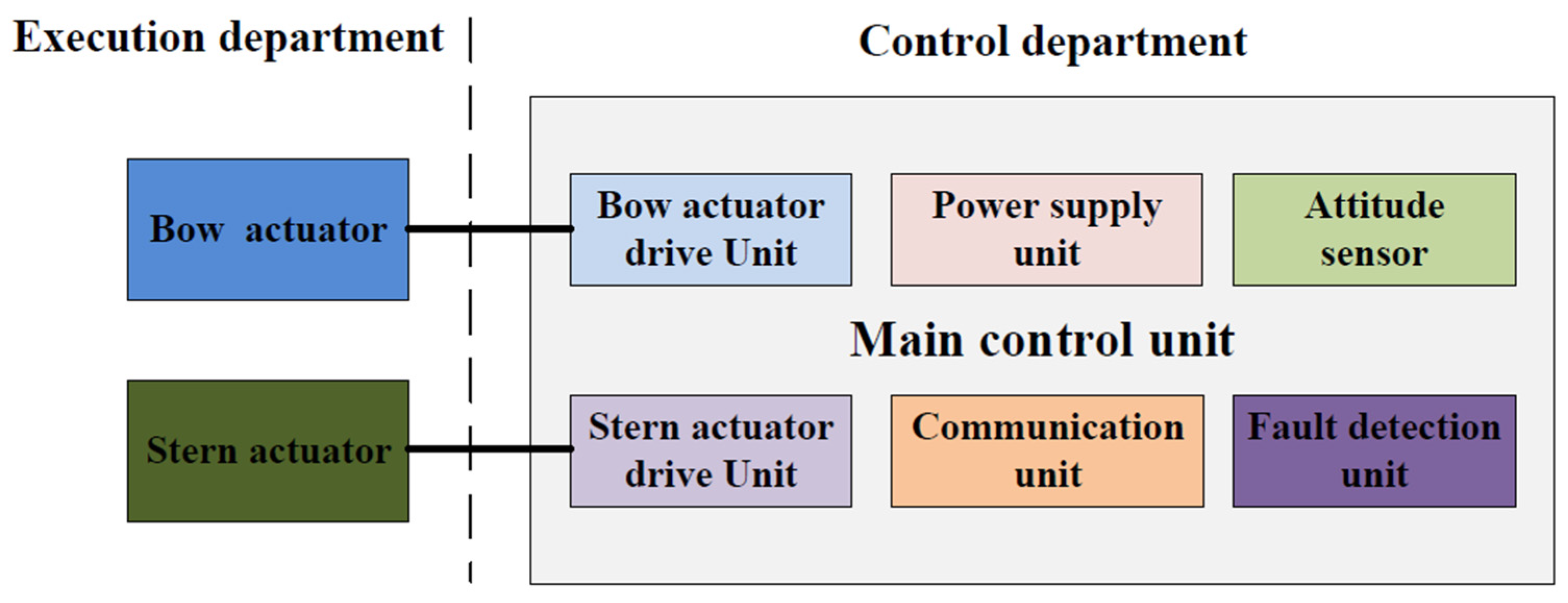

The system composition of the “biped” bottom-landing mechanism is shown in the figure below (

Figure 15). The system is generally divided into two parts: the execution part and the control part. The execution part is supported by two sets of mechanisms (bow and stern).

The logic control diagram of the “biped” bottom-landing mechanism is shown in the figure below (

Figure 16). The main functions of the system include the control and detection of the bow and stern sets of executive mechanisms, as well as the sensing and adjustment of excessive pitch angles. When the seabed is uneven, the system can adjust the pitch attitude according to the attitude sensing data [

31,

32].

2.6. Research on Control Strategies for Bottom-Landing and Bottom-Leaving

2.6.1. Landing Criteria and Procedures

Bottom-landing control relies on vertical channel motors and buoyancy adjustment to control the AUV to land on the seabed with a certain heading, and then perform resident detection after adjusting the pitch attitude. For the bottom-landing control process, it is first necessary to manipulate the AUV to complete a hovering action at a fixed height of 3 m, then control the “biped” bottom-landing mechanism to extend the bottom-landing plate, turn on the buoyancy adjustment mechanism to recover buoyancy, make the AUV obtain negative buoyancy, and drive the AUV to land on the seabed. As the height from the seabed becomes smaller and smaller during bottom-landing, the altimeter and Doppler will enter the blind zone. Therefore, it is necessary to use the change in depth value as the criterion for judging whether the bottom-landing is completed. The target value is determined by subtracting the extended length of the bottom-landing mechanism and the installation height of the altimeter from the current water depth value [

33]. When the target value δ remains unchanged for one minute, and both the mean value and variance of the target value are 0, it is considered that the bottom-landing is completed. At this time, the buoyancy adjustment is turned off, and the bottom-landing process is exited. The calculation of the control target value δ is as follows,

where

represents the current water depth value,

h0 represents the hovering water depth value before bottom-landing,

denotes the installation height of the depth gauge relative to the altimeter on the AUV,

stands for the extension length of the bottom-landing mechanism, and

is a constant (this paper takes

= 0.01). The scenario diagram for calculating the landing criterion is shown in the figure below (

Figure 17). The full name of DVL is Doppler Velocity Log.

When the seabed is uneven, there is a difference in the extension length between the bow and stern legs of the bottom-landing mechanism, which is used to adjust the underwater bottom-landing attitude of the AUV. After adjustment, the pitch angle of the AUV is approximately 0. The target value at this time is corrected as follows:

where

is the extension length of the stern bottom-landing mechanism,

is the extension length of the bow bottom-landing mechanism, and

is the seabed inclination angle, which can be specifically calculated by the following formula.

where

is the horizontal distance between the depth gauge and the stern bottom-landing leg, with

= 0.9 m;

is the horizontal distance between the depth gauge and the bow bottom-landing leg, with

= 1.8 m. The scenario diagram for calculating the landing criterion is shown in the figure below (

Figure 18). When

=

, the criterion calculation process is similar to the above procedure and will not be repeated here.

2.6.2. Bottom-Leaving Control Strategy

Bottom-leaving control relies on buoyancy adjustment by draining oil to control the AUV to leave the seabed, enabling the AUV to surface to a navigable state through static driving. As specifically shown in the bottom-landing and -leaving control process (

Figure 19). At this time, the impact on the seabed’s ecological environment is minimal, and there is no need to consider environmental restoration issues. The surfacing process uses the depth variation as the criterion [

34]. The control target value δ

s is calculated as follows,

When the AUV meets the above criteria, the DVL and altimeter will normally obtain the height data relative to the seabed. At this point, it is considered that the bottom-leaving operation is completed; the buoyancy adjustment should be turned off, the bottom-landing mechanism retracted, and the bottom-leaving command exited. The AUV can then carry out subsequent exploration tasks.

Using the above-mentioned bottom-landing and bottom-leaving methods, the AUV can complete multi-point bottom-landing and resident observation, and can also carry out resident exploration and observation in sensitive waters. After the mission is completed, the AUV leaves the seabed and can navigate to safe waters convenient for recovery according to the mission plan, jettison its ballast to surface, and be recovered.