An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

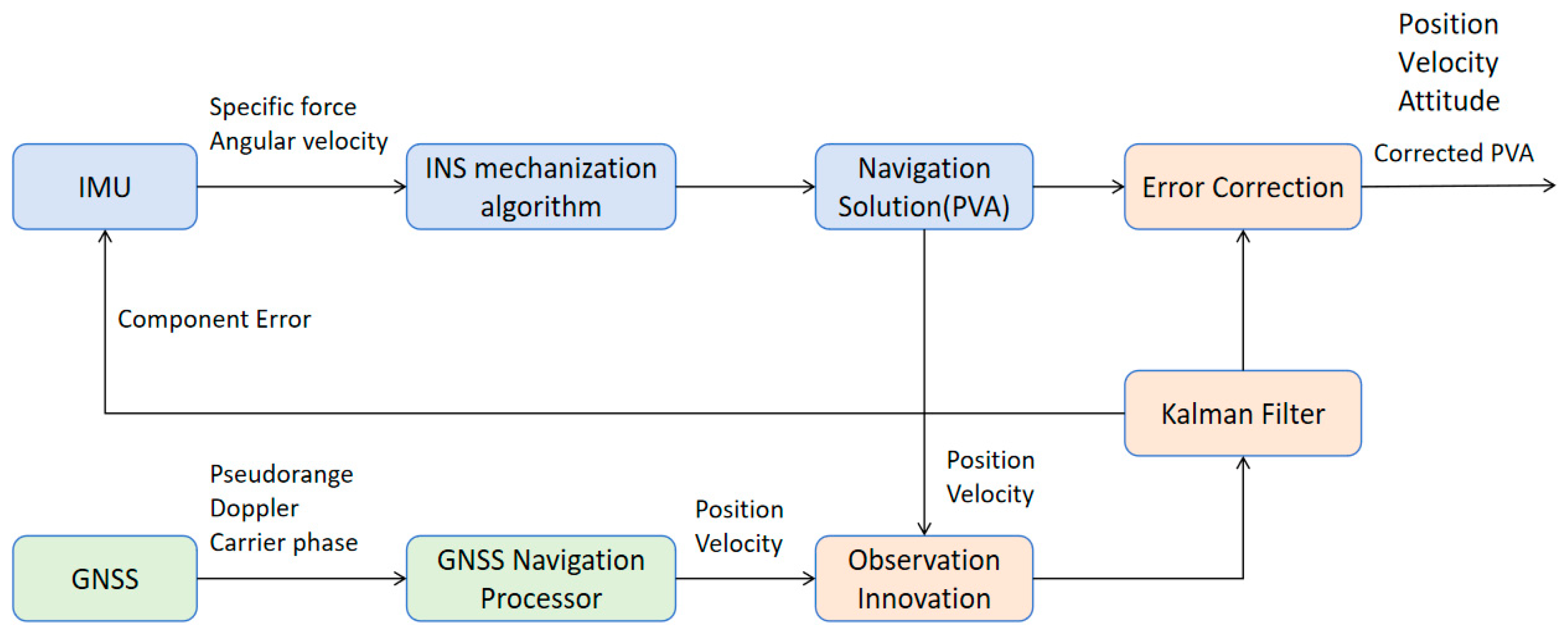

- (1)

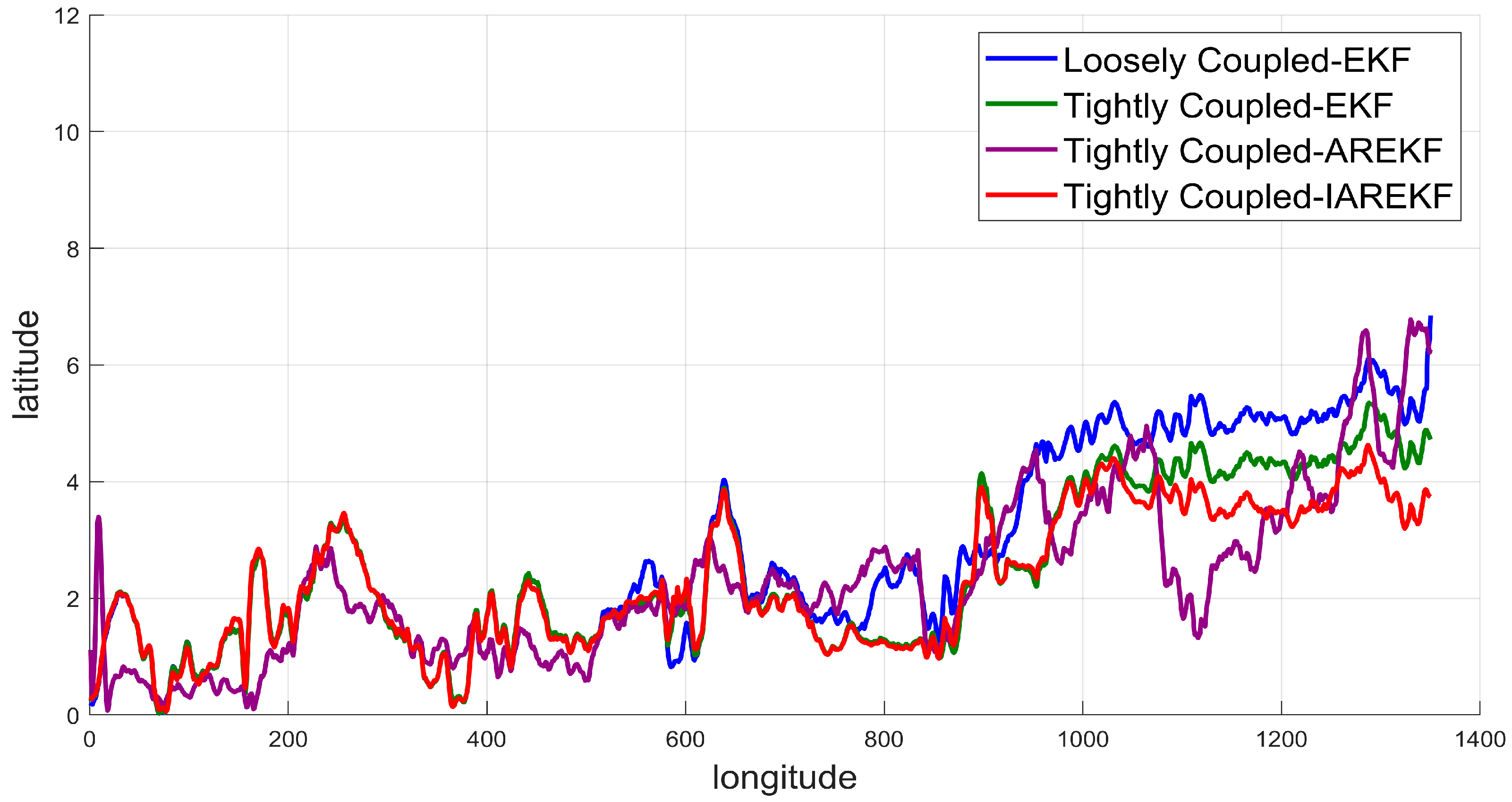

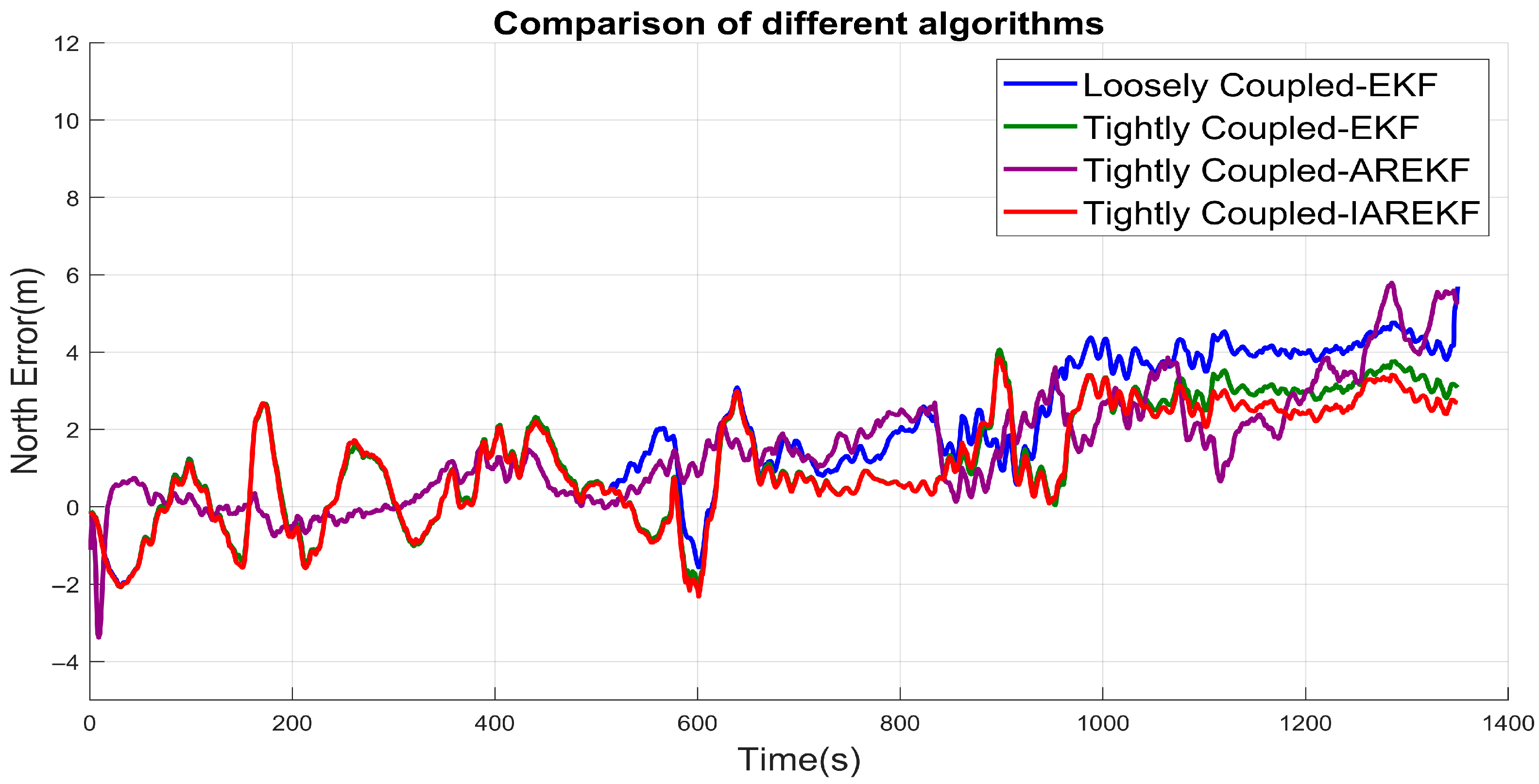

- Establishing a Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Mathematical Model: This paper first establishes a mathematical model for tightly coupled GNSS/INS integrated navigation and further analyzes the accuracy differences between loosely coupled and tightly coupled models in practical applications. Through processing and analysis of actual Arctic navigation data, the navigation accuracy performance of the two combined methods is explored in depth. Research shows that the tightly coupled model can more effectively integrate GNSS and INS data compared to the loosely coupled model, improving the system’s navigation accuracy and robustness, especially in complex environments. Comparative experiments further verify the advantages of tightly coupled integrated navigation under extreme navigation conditions.

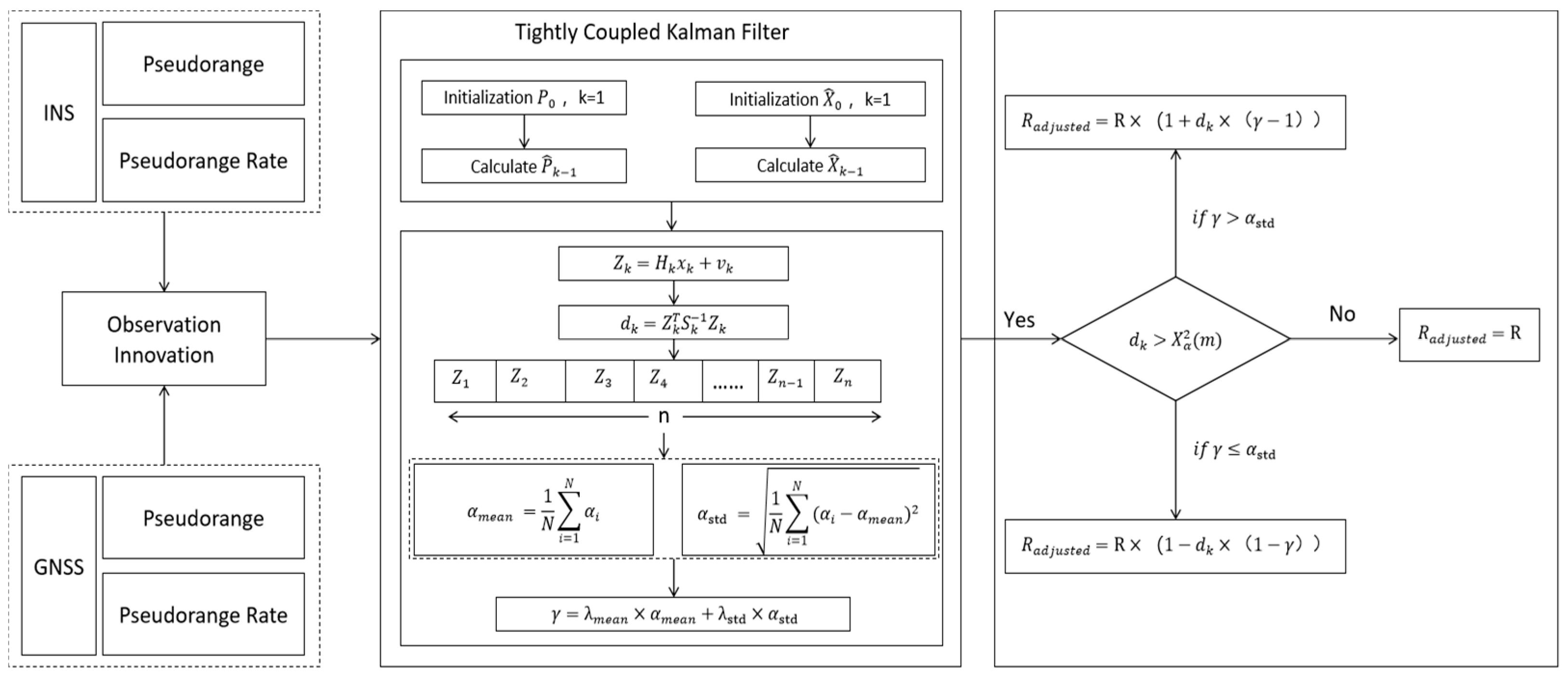

- (2)

- Extended Kalman Filter Optimization: To address the degradation problem of Arctic GNSS signals, this paper first replaces the traditional Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) with an Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter (AREKF) based on Mahalanobis distance. By calculating the Mahalanobis distance of the residuals and comparing it with a set chi-square threshold, the innovative covariance matrix is dynamically adjusted. Furthermore, a sliding window-based observation noise covariance matrix estimation framework is used to further improve the system’s robustness and estimation accuracy under GNSS signal anomalies.

- (3)

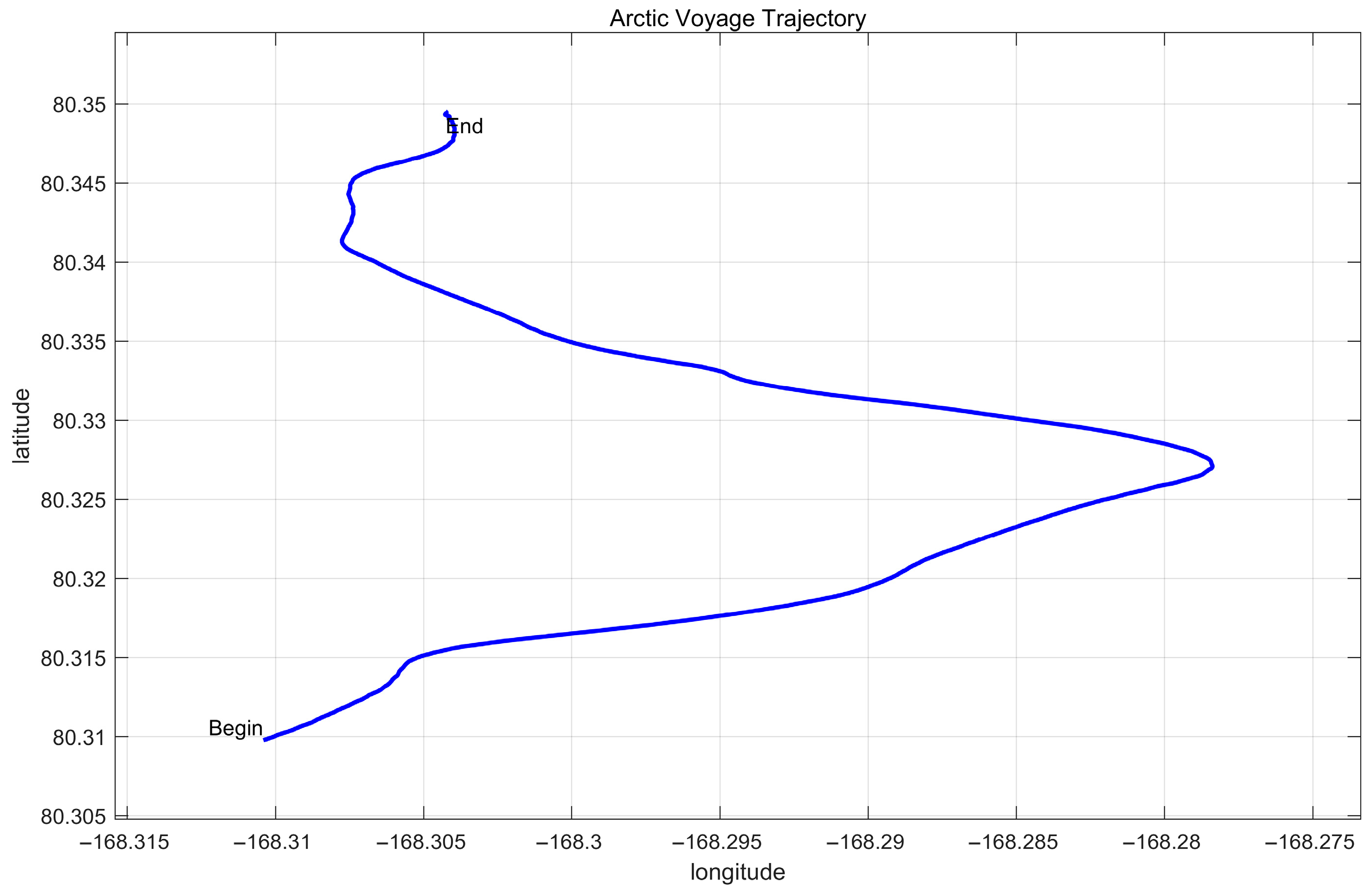

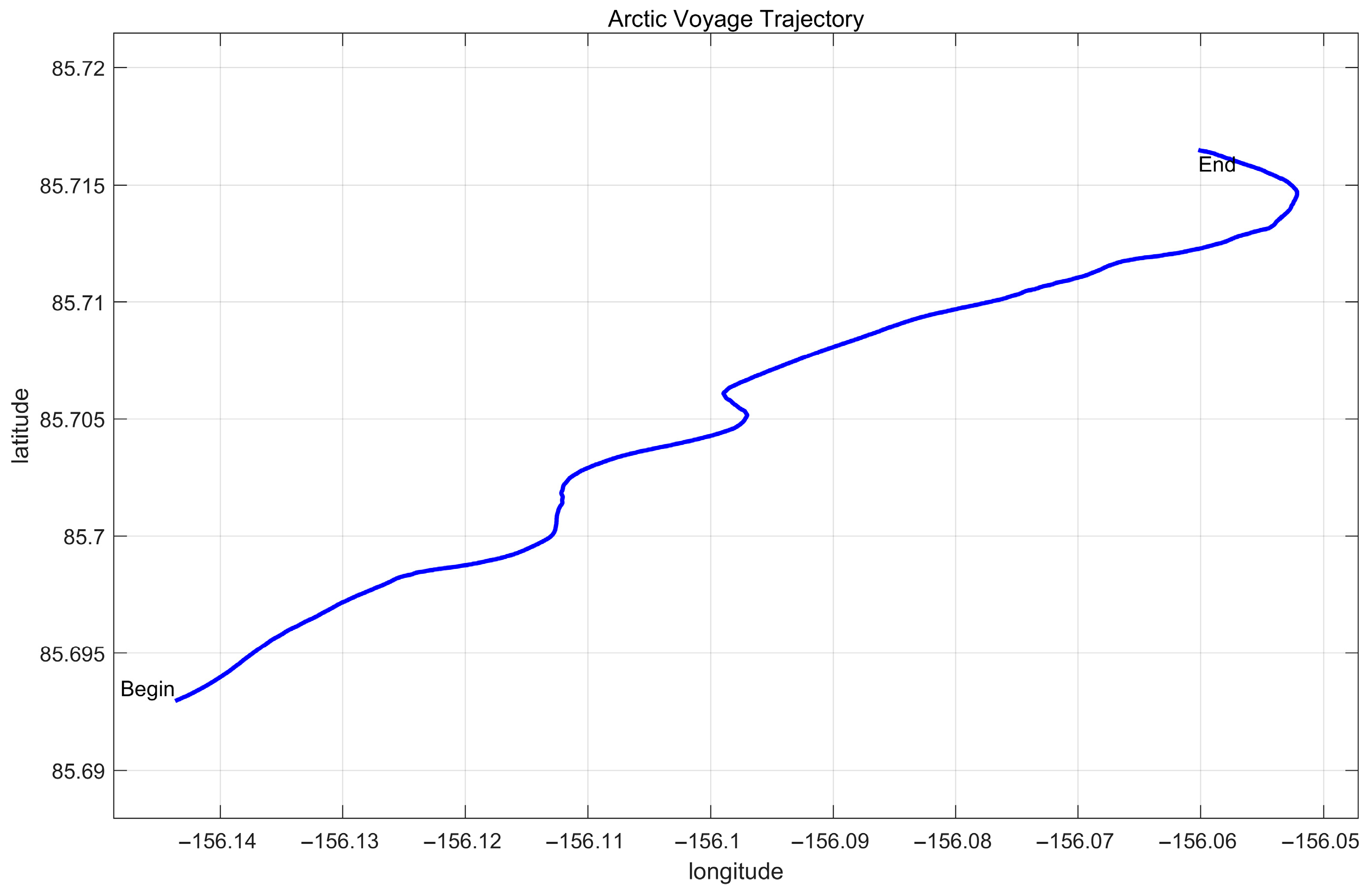

- Arctic Shipborne Data Validation: To verify the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method, this paper validated it using real Arctic shipborne data, covering two continuous trajectories of approximately 1300 s at latitudes of 80.3° and 85.7°. In the test at latitude 80.3°, the horizontal positioning accuracy was improved by 61.78% compared to the traditional method; in the test at latitude 85.7°, the horizontal positioning accuracy was improved by 21.7%. Experimental results show that under extreme conditions of severe GNSS signal degradation, the proposed method can effectively maintain excellent horizontal accuracy and robustness.

2. System Model and Filtering Algorithm

2.1. Common Part of GNSS/INS Dynamic Model

2.2. GNSS/INS Tight-Coupled System Model

2.3. Filtering Algorithm

3. Results

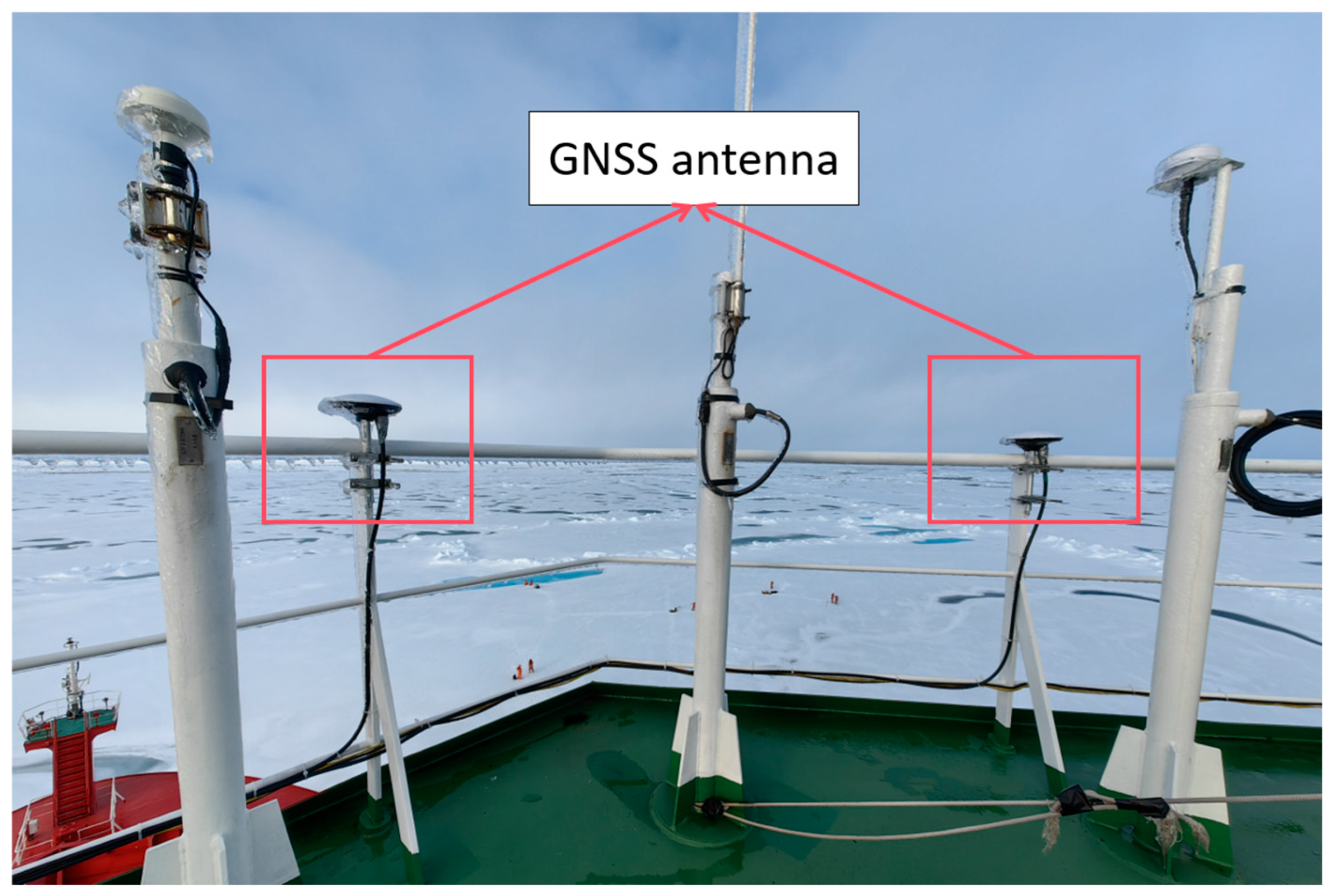

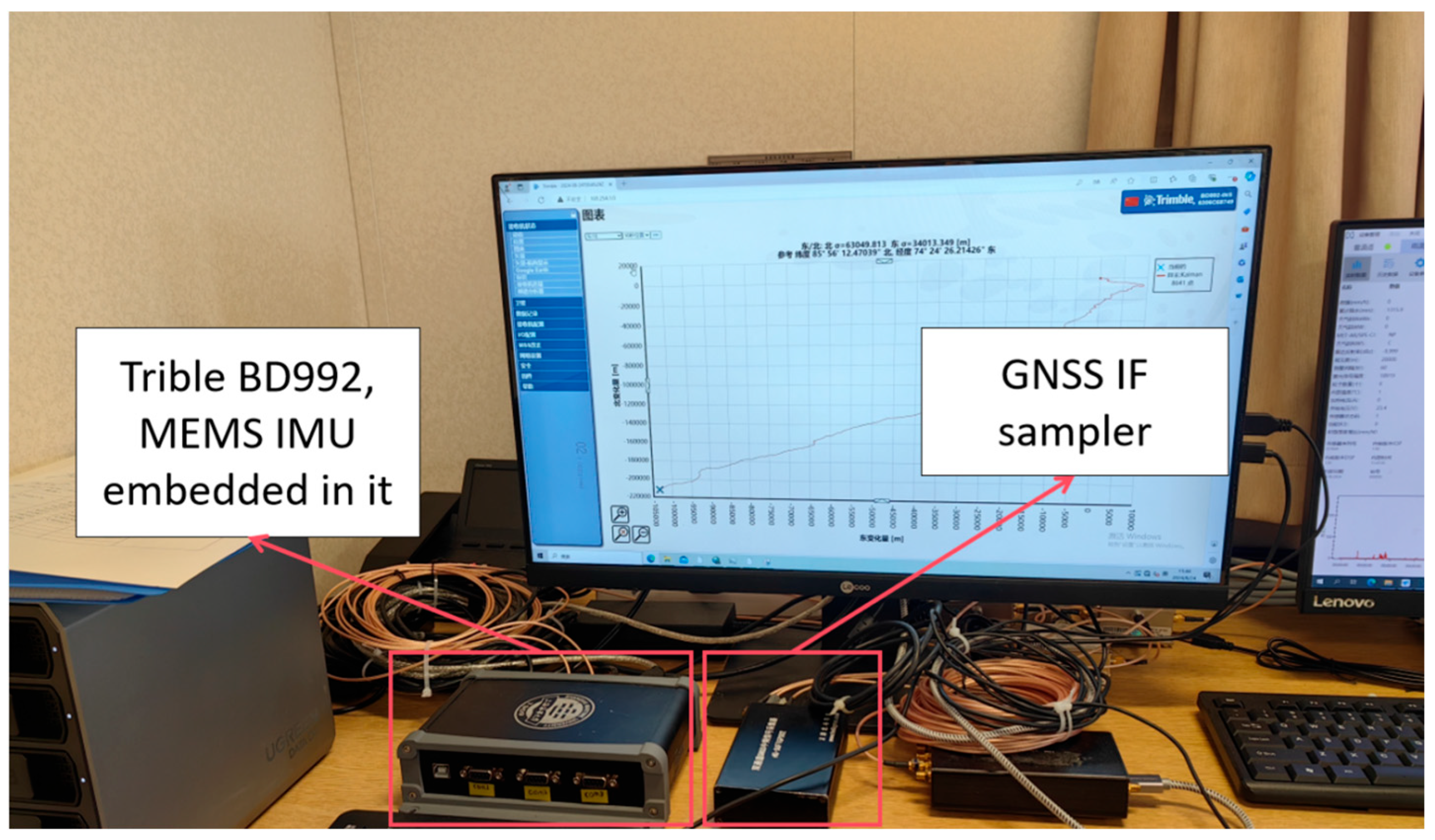

3.1. Experimental Description

3.2. Experimental Equipment

- (1)

- A STIM300 (Sensonor AS, Horten, Norway), a tactical-grade MEMS IMU co-located with a Trimble BD992 dual-frequency GNSS receiver inside a rigid enclosure.

- (2)

- A GNSS Intermediate Frequency (IF) sampler (HG-SOFTGPS01-B) for capturing raw GNSS signals.

- (3)

- Two GNSS antennas rigidly mounted on the vessel deck to reduce lever-arm effects.

3.3. Experimental Equipment and Route

4. Discussion

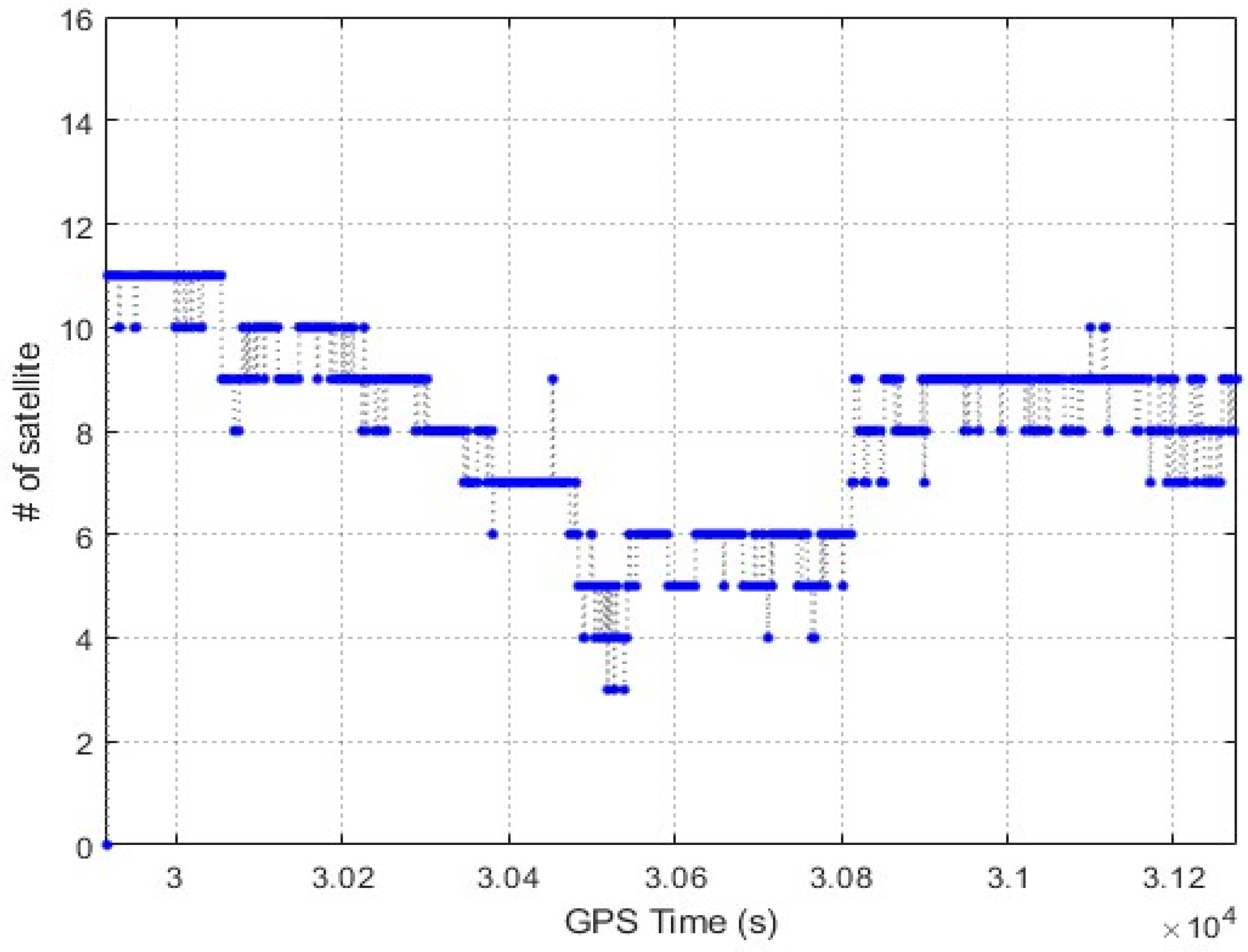

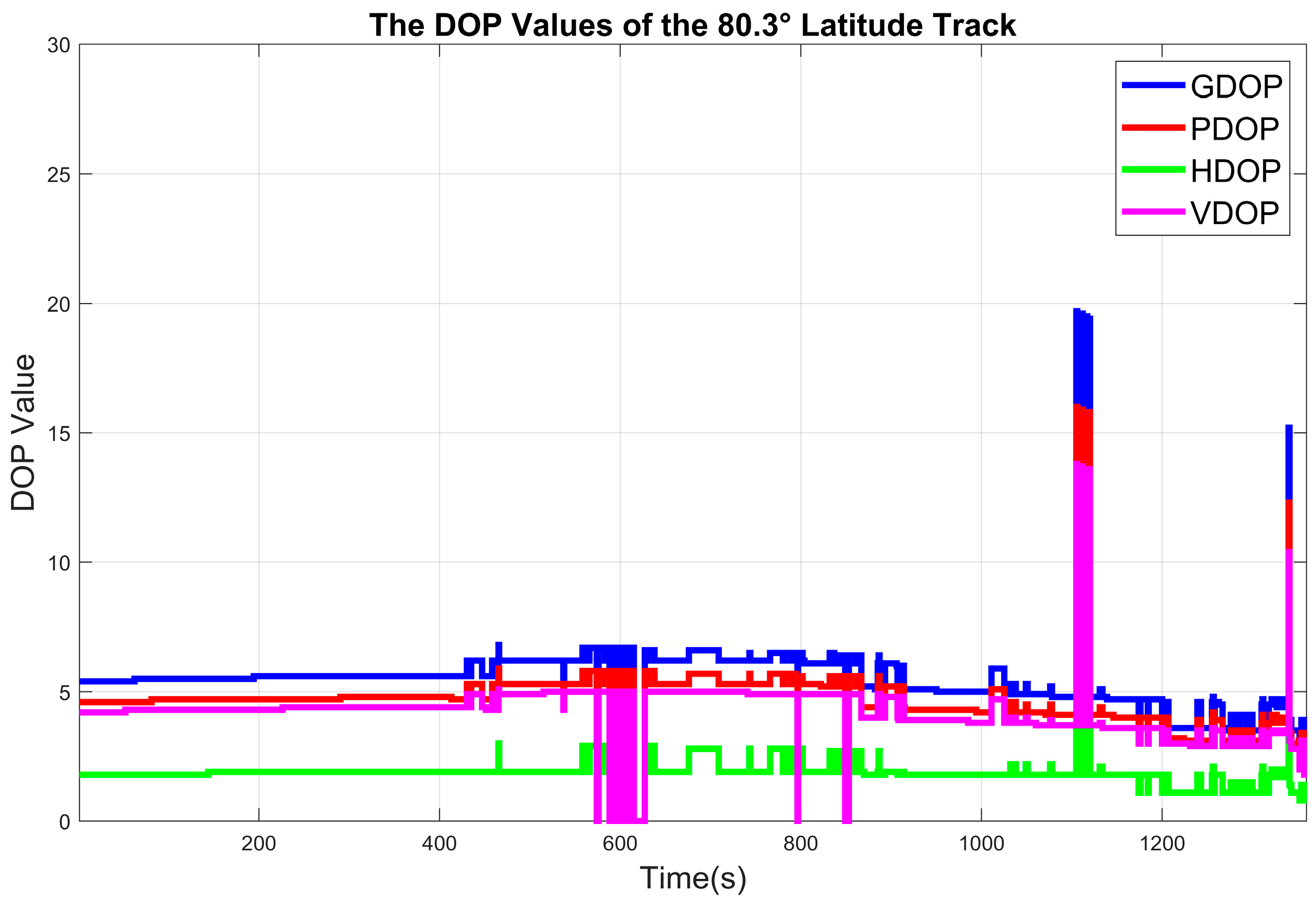

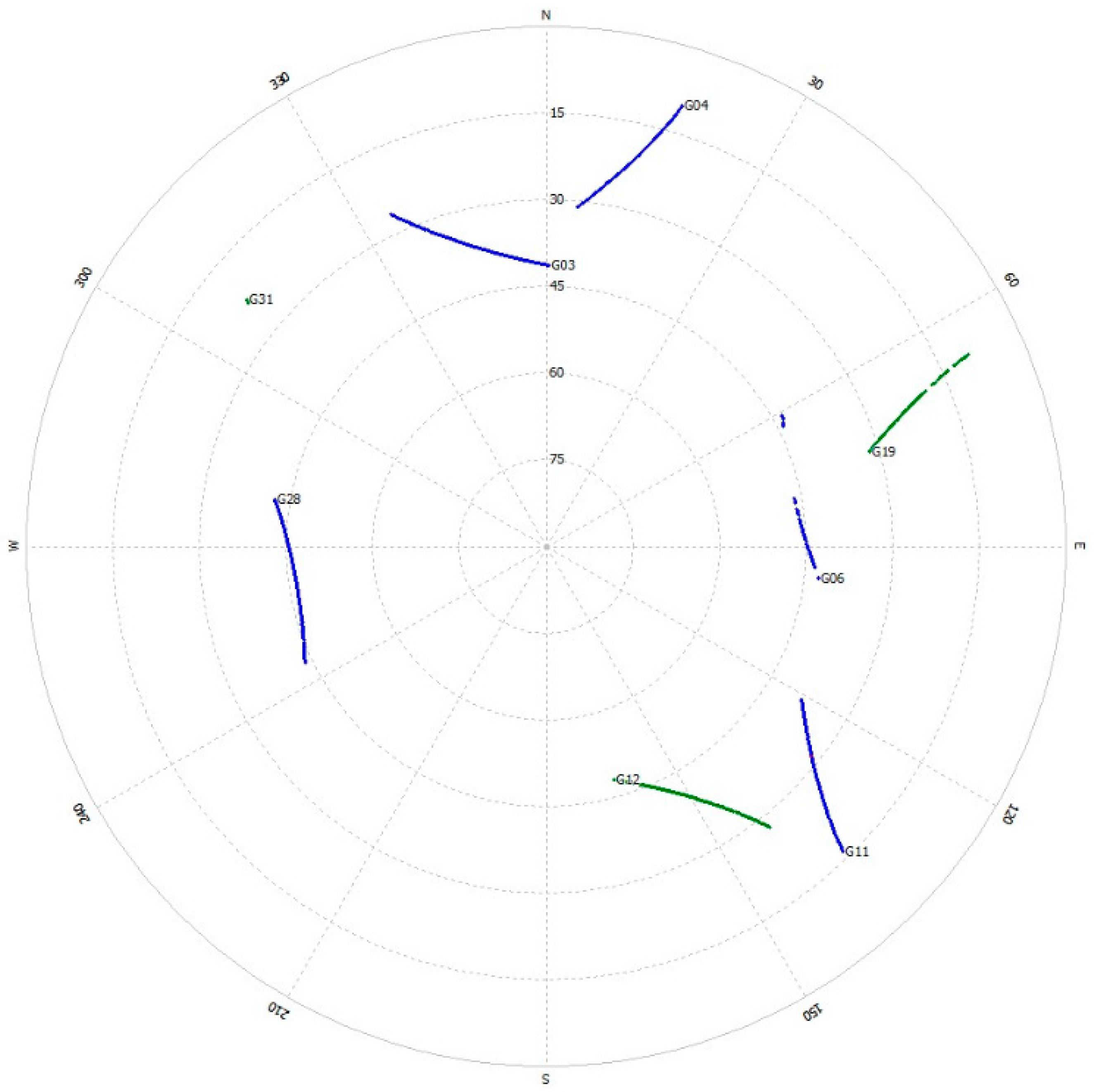

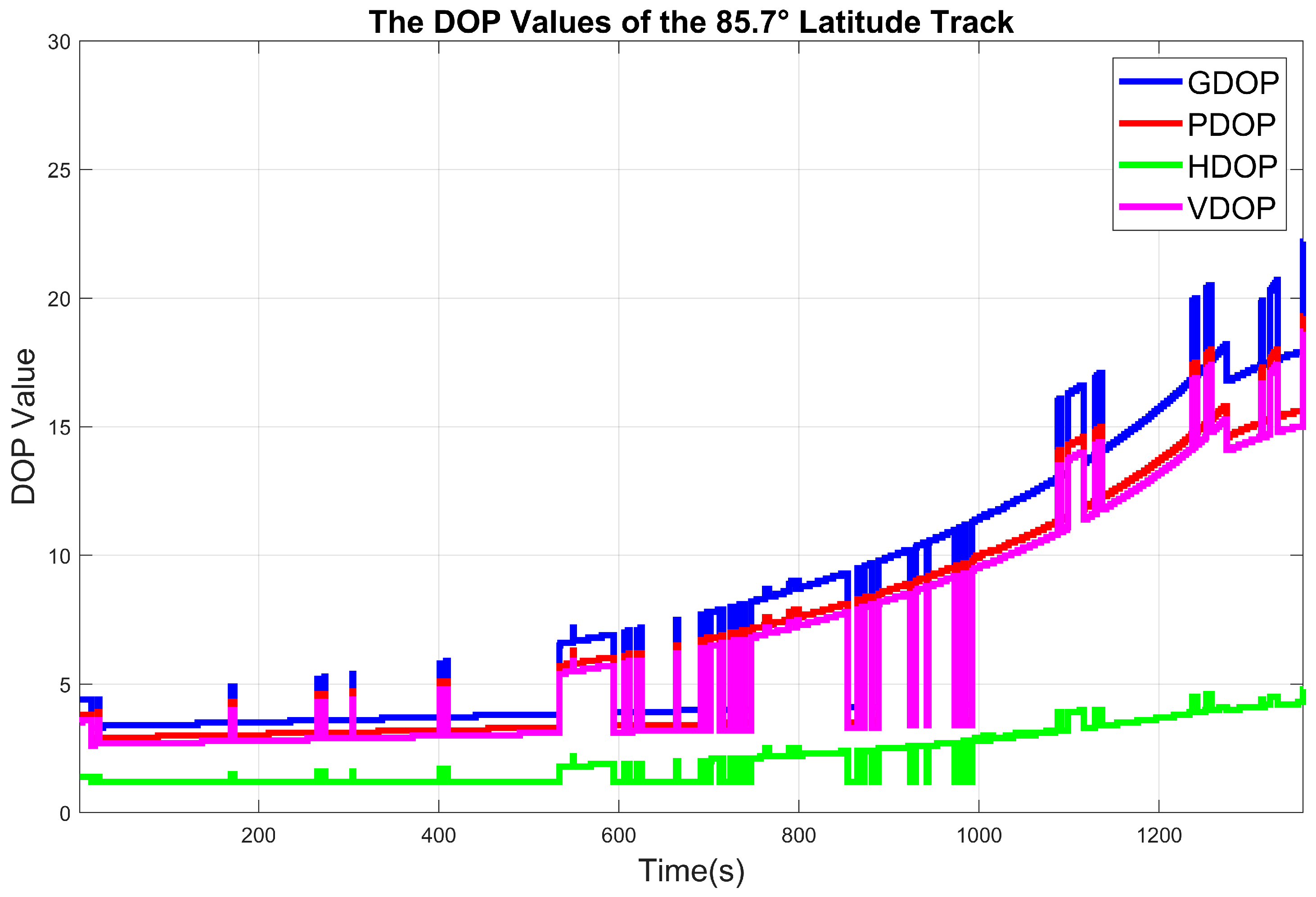

4.1. Arctic GNSS Navigation Features

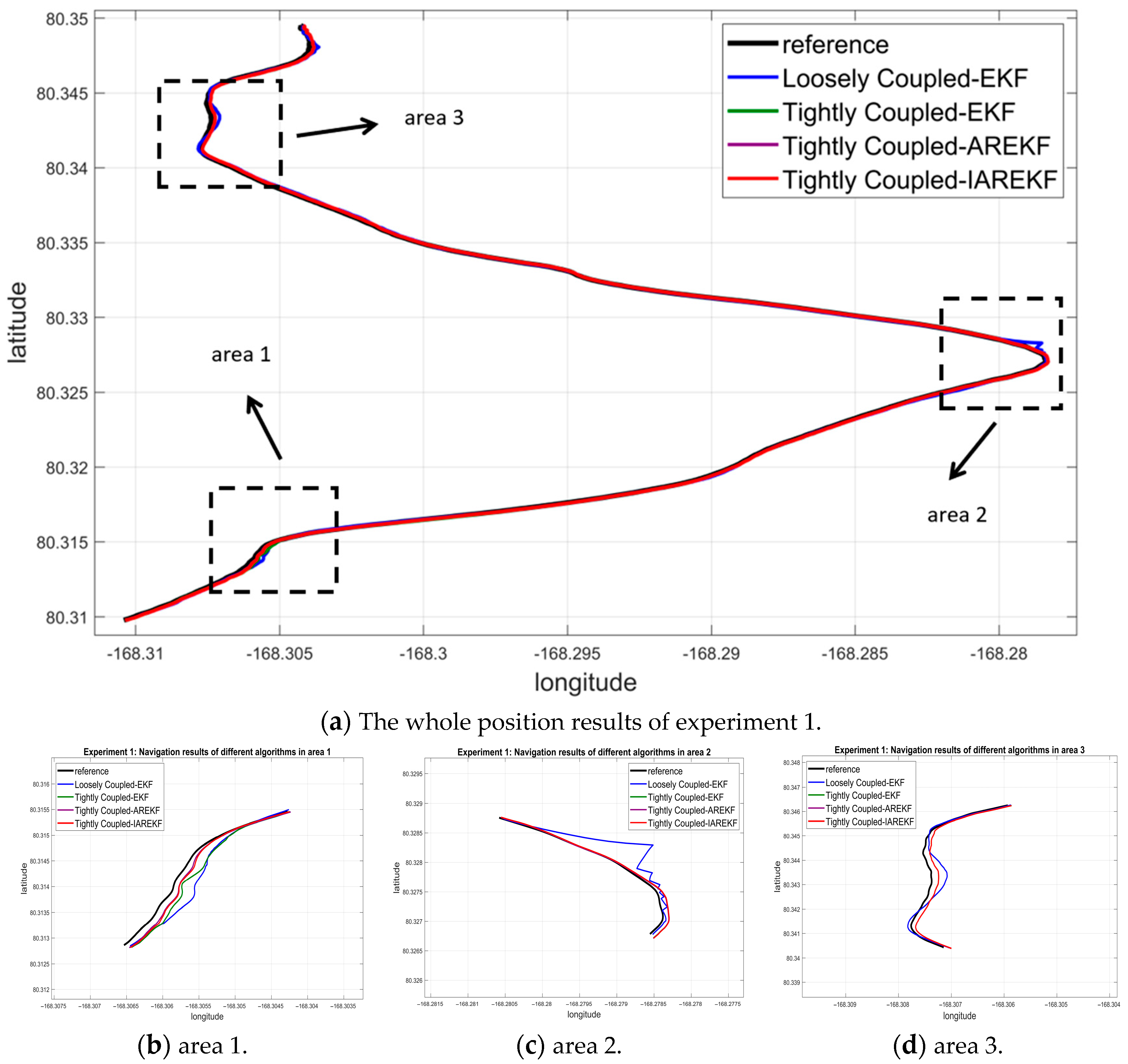

4.2. Experimental 1 Results

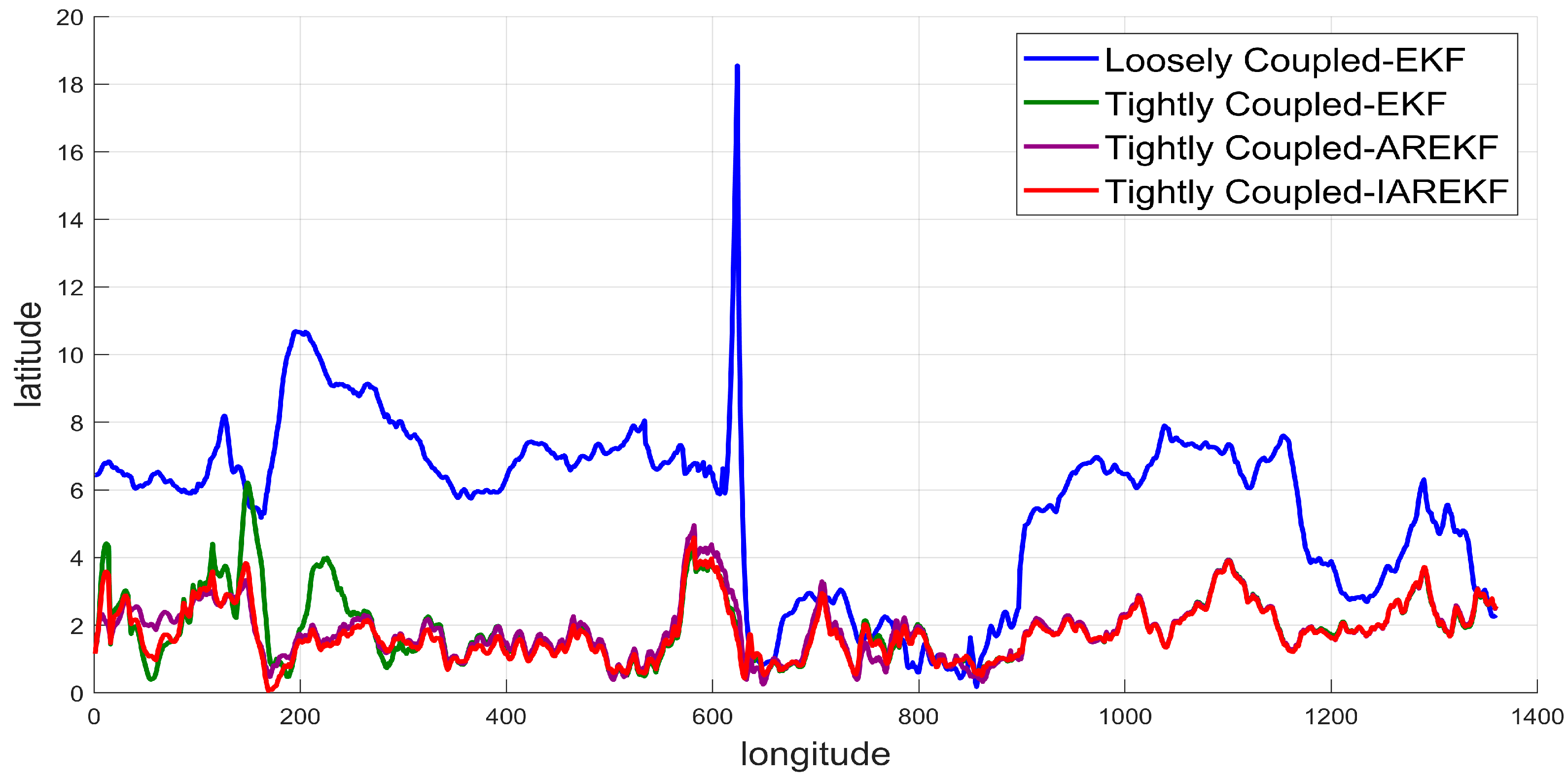

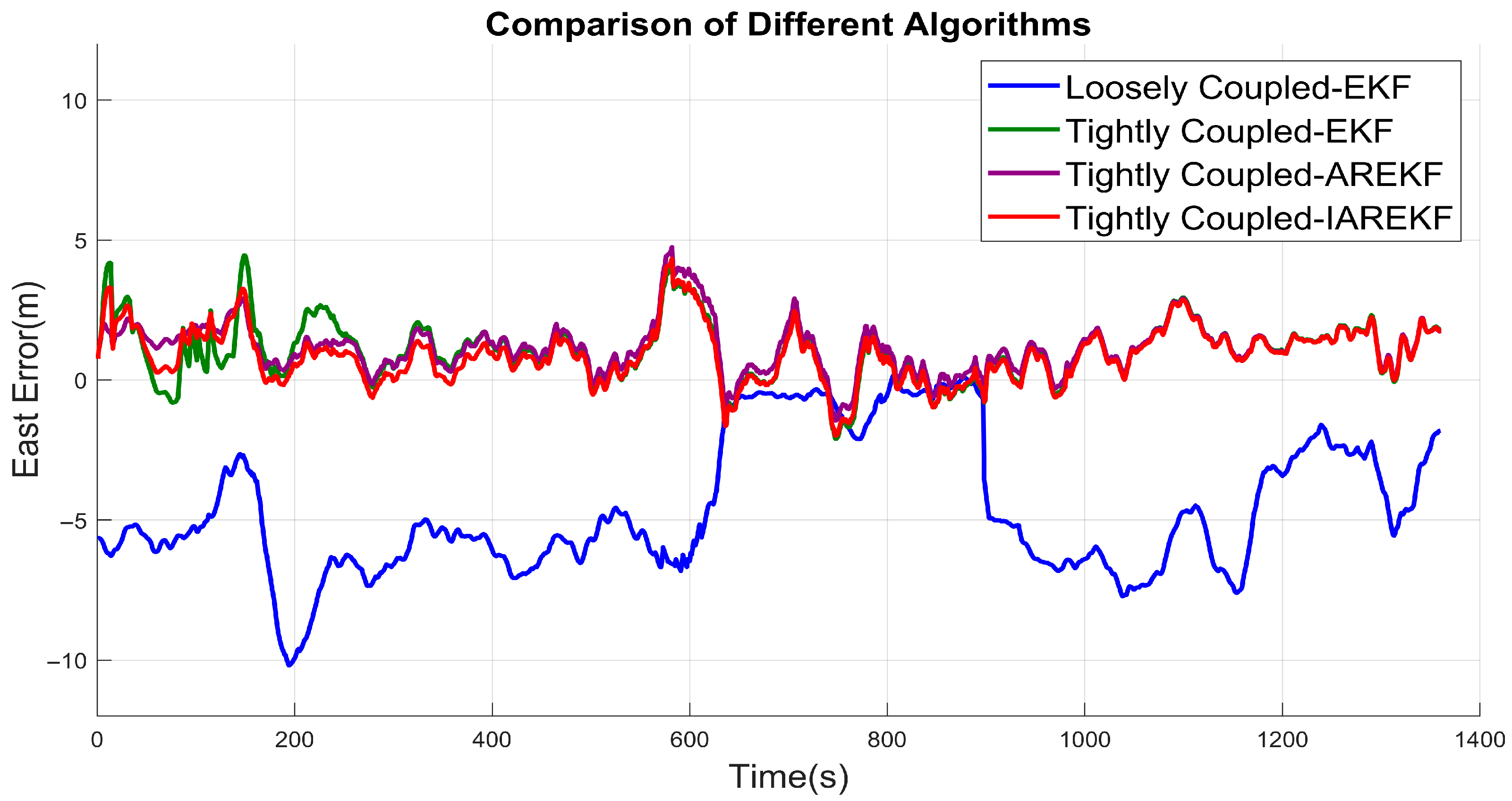

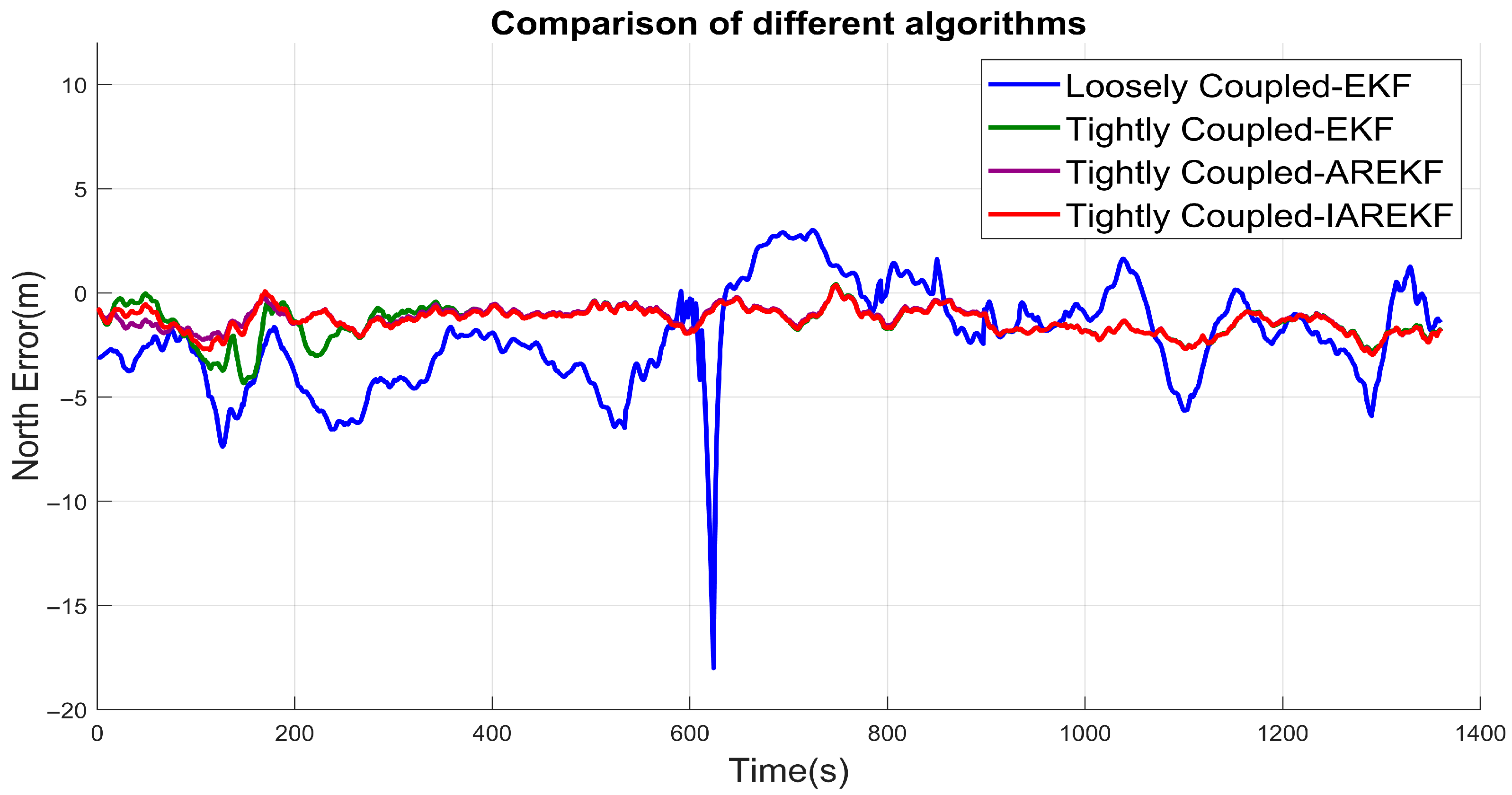

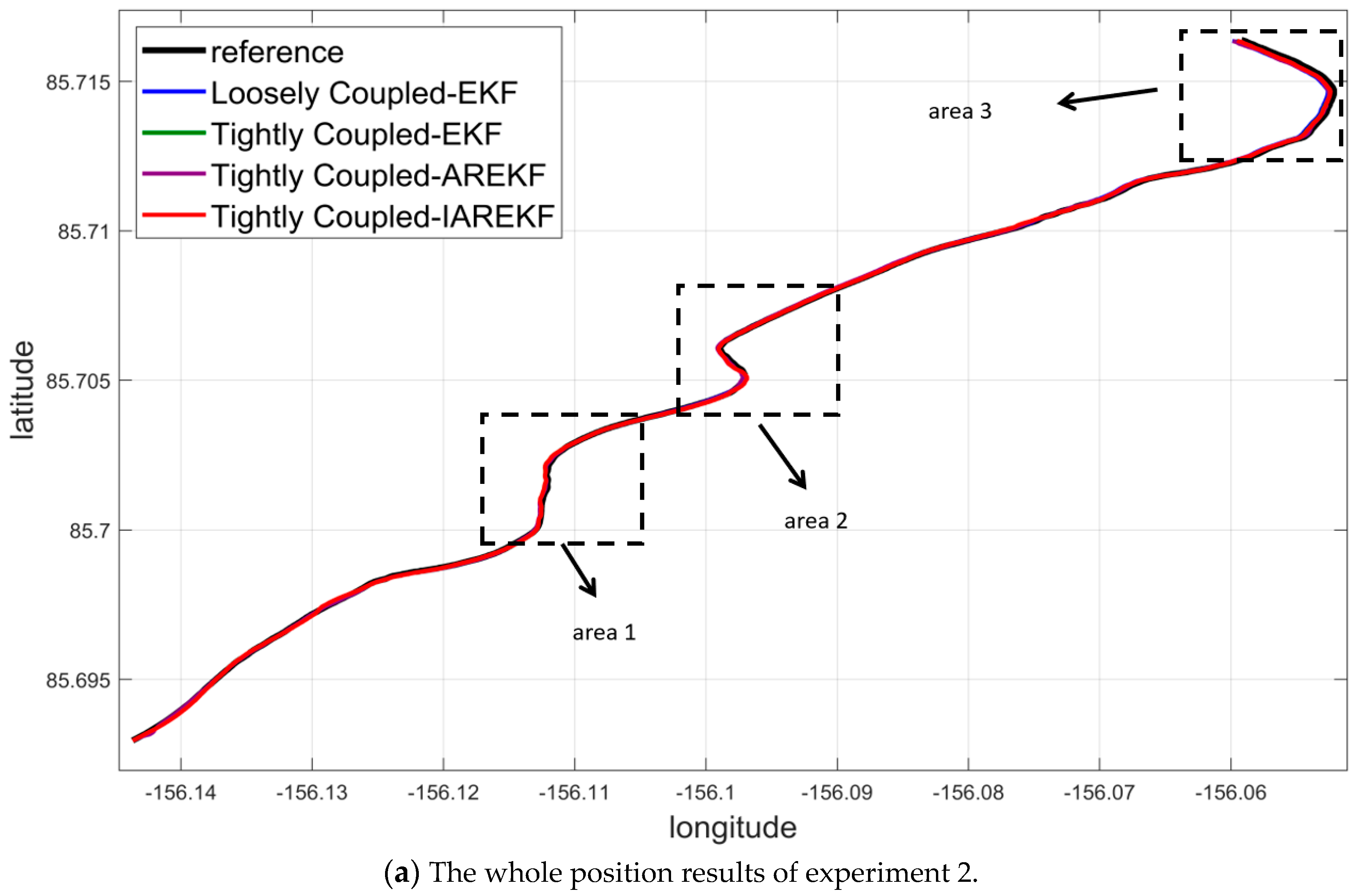

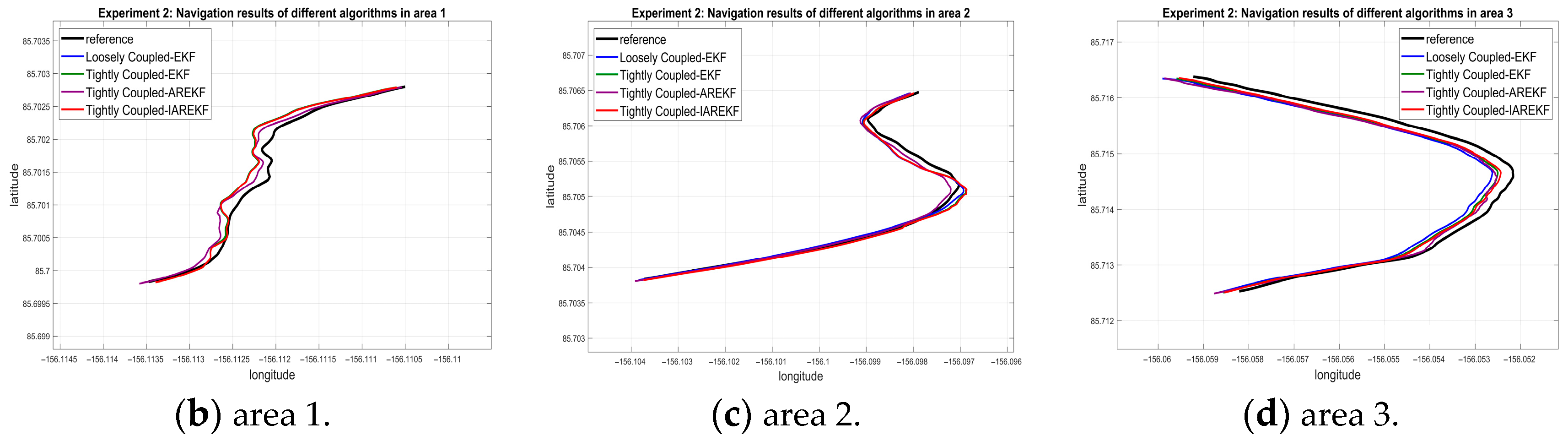

4.3. Experimental 2 Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUV | autonomous underwater vehicle |

| GNSSs | Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| INSs | Inertial Navigation Systems |

| IAREKF | Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter |

| AREKF | Adaptive Robust 27 Extended Kalman Filter |

| GDOP | geometric dilution of precision |

| IMUs | inertial measurement units |

| KF | Kalman filter |

| MMSE | minimum mean square error |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| UKF | unscented Kalman filter |

| CKF | cubature Kalman filter |

| PF | particle filter |

| AKF | Adaptive Kalman Filter |

| RKF | Robust Kalman Filter |

| ARKF | adaptive robust Kalman filter |

| I-MORKF | improved multiple-outlier-robust Kalman filter |

| IF | Intermediate Frequency |

| PPS | Pulse-Per-Second |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

References

- Huntington, H.P.; Olsen, J.; Zdor, E.; Zagorskiy, A.; Shin, H.C.; Romanenko, O.; Kaltenborn, B.; Dawson, J.; Davies, J.; Abou-Abbsi, E. Effects of Arctic commercial shipping on environments and communities: Context, governance, priorities. Transp. Res. Part D 2023, 118, 103731. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, M.R.; Roushdi, M.; Aboelkhear, M. Potential benefits of climate change on navigation in the northern sea route by 2050. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Environmental impacts of Arctic shipping activities: A review. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 247, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Zhou, X.; Luo, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Q. Toward quantifying the increasing accessibility of the Arctic Northeast Passage in the past four decades. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2023, 40, 2378–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meeren, C.; Oksavik, K.; Lorentzen, D.A.; Rietveld, M.T.; Clausen, L.B.N. Severe and localized GNSS scintillation at the poleward edge of the nightside auroral oval during intense substorm aurora. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 10607–10621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayyil, J.P.; McCaffrey, A.M.; Wang, Y.; Themens, D.R.; Watson, C.; Reid, B.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, Z. Global positioning system (GPS) scintillation associated with a polar cap patch. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Ben, Y.; Cui, W.; Li, Q. An improved damping method for grid inertial navigation system in polar region. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 8505713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Shang, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ma, D. Panoramic sea-ice map construction for polar navigation based on multi-perspective images projection and camera poses rectification. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 3417–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Hu, J.; Guo, Y. Global integrated navigation position correction algorithm and virtual polar region technology based on normal vector. Measurement 2025, 242, 116031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ben, Y.; Yu, F.; Tan, J. Transversal strapdown INS based on reference ellipsoid for vehicle in the polar region. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 65, 7791–7795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Xu, T.; Wang, A.; Fan, W. Polar Integrated Navigation Algorithm Based on Transverse Earth Coordinate System. In Proceedings of the 2023 38th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Hefei, China, 27–29 August 2023; pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Yastrebova, A.; Höyhtyä, M.; Boumard, S.; Lohan, E.S.; Ometov, A. Positioning in the Arctic region: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 53964–53978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, T.; Walter, T.; Blanch, J.; Enge, P. GNSS Integrity in the Arctic. NAVIGATION J. Inst. Navig. 2016, 63, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, K.; Goode, M.; Liu, X.; Stone, M. Precise GNSS positioning in Arctic regions. In Proceedings of the OTC Arctic Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 10–12 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X.; Dai, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q. Feature-based GNSS positioning error consistency optimization for GNSS/INS integrated system. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhan, X.; Yang, R. INS-aiding information error modeling in GNSS/INS ultra-tight integration. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Duan, X. A Low-Cost GNSS/INS integration method aided by Cascade-LSTM Pseudo-Velocity measurement for bridging GNSS outages. Measurement 2025, 240, 115518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, S. A novel factor graph framework for tightly coupled GNSS/INS integration with carrier-phase ambiguity resolution. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 13091–13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, G.; Pini, M.; Marucco, G. Loose and tight GNSS/INS integrations: Comparison of performance assessed in real urban scenarios. Sensors 2017, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broumandan, A.; Lachapelle, G. Spoofing detection using GNSS/INS/odometer coupling for vehicular navigation. Sensors 2018, 18, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.; Bobye, M.; Kruger, B.; Jacox, J. GNSS/INS sensor fusion with on-board vehicle sensors. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2020), Online, 21–25 September 2020; pp. 424–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Pan, S.; Gao, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, L. Variational Bayesian-based robust adaptive filtering for GNSS/INS tightly coupled positioning in urban environments. Measurement 2023, 223, 113668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tan, H.; Yan, P.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, G.; Jiang, J. A GNSS/INS integrated navigation compensation method based on CNN–GRU+ IRAKF hybrid model during GNSS outages. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, P. A tutorial introduction to kalman filtering. In Proceedings of the IEE Colloquium on Kalman Filters: Introduction, Applications and Future Developments, London, UK, 21 February 1989; pp. 1/1–1/6. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin, J.; Koopman, S.J. Time Series Analysis by State Space Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Han, B.; Wang, S. A robust GNSS sensors in presence of signal blockage for USV application. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 35, 035124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, Y. Improvement of carrier phase tracking in high dynamics conditions using an adaptive joint vector tracking architecture. GPS Solut. 2019, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Li, G.; Dai, W.; Tian, S.; Fan, G.; Wang, J.; Dai, X. Cooperative relative localization for UAV swarm in GNSS-denied environment: A coalition formation game approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 11560–11577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, G.; Cai, Q. Autonomous aerial–ground cooperative navigation based on information-seeking in GNSS-denied environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 17058–17069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Shen, G.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, P.; Wang, Q.-G. Angle residual weighted adaptive Kalman filtering for mine-used underground monorail crane localization based on UWB/INS integration. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 74, 1000711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y. Artificial neural network based on strong track and square root UKF for INS/GNSS intelligence integrated system during GPS outage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Q. An Innovation-Based Adaptive Cubature Kalman Filtering for GPS/SINS Integrated Navigation. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 25, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhu, N.; Renaudin, V. A voting-based robust estimator aided by INS redundancy for tightly coupled GNSS/INS integration in urban environment. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 13430–13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, R.E.; Bucy, R.S. New results in linear filtering and prediction theory. J. Basic Eng. 1961, 83, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Qian, H.; Shen, F. Application of neural network and improved unscented kalman filter for GPS/SINS integrated navigation system. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), Portland, OR, USA, 20–23 April 2020; pp. 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X. Motion constraint aided integrated navigation method based on SVD-CKF. J. Electron. Meas. Instrum. 2022, 36, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, T. A novel method for ai-assisted INS/GNSS navigation system based on CNN-GRU and CKF during GNSS outage. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Sheng, C.; Yu, B.; Huang, L.; Rong, Q. An indoor and outdoor multi-source elastic fusion navigation and positioning algorithm based on particle filters. Future Internet 2022, 14, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Griebel, T.; Graichen, K. Adaptive kalman filtering: Measurement and process noise covariance estimation using kalman smoothing. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 11863–11875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Zuo, J.; Yang, Z. Adaptive-robust fusion strategy for autonomous navigation in GNSS-challenged environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 6817–6832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, T.; Kim, S. State-of-charge estimation for remaining flying time prediction of small UAV using adaptive robust extended kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 61, 959–977. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Pan, S.; Gao, W.; Liu, L. An improved multiple-outlier-robust kalman filter for GNSS/INS tightly coupled positioning in urban canyons. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 48131–48145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input: | Observation vector , observation matrix , observation noise covariance |

| Output: | |

| Step 1: | Initialize sliding window size |

| Step 2: | Calculate the innovation residual covariance matrix (27). |

| Step 3: | Calculate the residual vector and calculate the Mahalanobis distance based on the residual, then update the sliding window storing the historical residuals (32). |

| Step 4: | Calculate the residual mean αmean and standard deviation αstd for the calculation of the adaptive factor (38), (39). |

| Step 5: | Set a threshold to determine if the residual is too large (34). |

| Step 6: | Calculate the adaptive factor and adjust the observation noise matrix based on the mean and fluctuation of the residuals (40). |

| Step 7: | Update the observation noise covariance matrix R based on the adaptive factor. If the residual is too large or the fluctuation is too high, increase the noise (41). |

| Step 8: | Output the updated . |

| Sensor | Specification | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEMS IMU (STIM 300, Sensonor AS, Norway) | Gyro bias instability | 0.5 | °/h |

| Angular random walk | 0.15 | ||

| Accelerometer bias | 0.05 | Mg | |

| Velocity random walk | 0.07 | m/s/ | |

| Sampling rate | 1000 | Hz | |

| Trimble BD992 | Sampling rate | 1 | Hz |

| Horizontal accuracy | 0.50 | m | |

| IF signal collector | Operating frequency | 16.369 | MHz |

| East Maximum Position Error (m) | North Maximum Position Error (m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Loosely Coupled-EKF | 10.1883 | 18.0037 |

| Tightly Coupled-EKF | 4.45543 | 4.3292 |

| Tightly Coupled-AREKF | 4.7444 | 2.95583 |

| Tightly Coupled-IAREKF | 4.32647 | 2.97044 |

| East Position RMSE (m) | North Position RMSE (m) | Horizontal Position RMSE (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loosely Coupled-EKF | 5.174 | 3.2496 | 6.1098 |

| Tightly Coupled-EKF | 1.4822 | 1.5886 | 2.1727 |

| Tightly Coupled-AREKF | 1.4846 | 1.4229 | 2.0564 |

| Tightly Coupled-IAREKF | 1.3416 | 1.453 | 1.9777 |

| East Maximum Position Error (m) | North Maximum Position Error (m) | |

|---|---|---|

| Loosely Coupled-EKF | 3.89833 | 5.69322 |

| Tightly Coupled-EKF | 3.86296 | 4.03766 |

| Tightly Coupled-AREKF | 3.88049 | 5.79537 |

| Tightly Coupled-IAREKF | 3.45221 | 3.83625 |

| East Position RMSE (m) | North Position RMSE (m) | Horizontal Position RMSE (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loosely Coupled-EKF | 2.0924 | 2.501 | 3.261 |

| Tightly Coupled-EKF | 2.0293 | 1.9296 | 2.8003 |

| Tightly Coupled-AREKF | 1.7242 | 2.0756 | 2.6983 |

| Tightly Coupled-IAREKF | 1.8248 | 1.7862 | 2.5535 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, W.; Qi, T.; Hu, Y.; Fu, S.; Han, B.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Wang, S. An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122395

Liu W, Qi T, Hu Y, Fu S, Han B, Hsieh T-H, Wang S. An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122395

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Wei, Tengfei Qi, Yuan Hu, Shanshan Fu, Bing Han, Tsung-Hsuan Hsieh, and Shengzheng Wang. 2025. "An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122395

APA StyleLiu, W., Qi, T., Hu, Y., Fu, S., Han, B., Hsieh, T.-H., & Wang, S. (2025). An Improved Adaptive Robust Extended Kalman Filter for Arctic Shipborne Tightly Coupled GNSS/INS Navigation. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122395