Behavior of Shared Suction Anchors in Clay Overlying Silty Sand Soils Considering the Souring Effect

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Previous Work

1.3. Objective of the Present Study

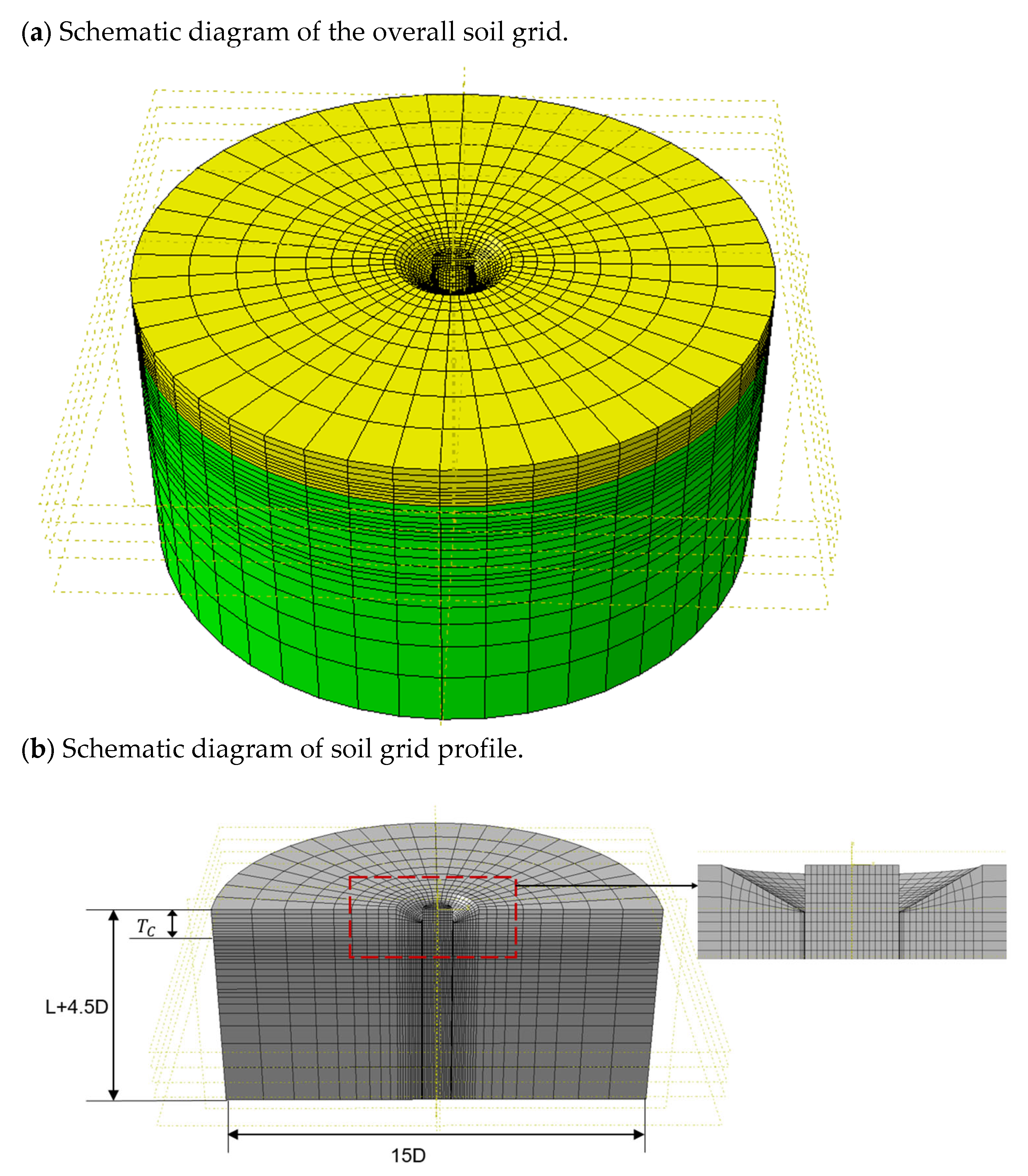

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Geometric Modeling of Shared Suction Anchor

2.2. Geometric Modeling of Soil Mass

2.3. Combination of Soil Mass and Shared Suction Anchors

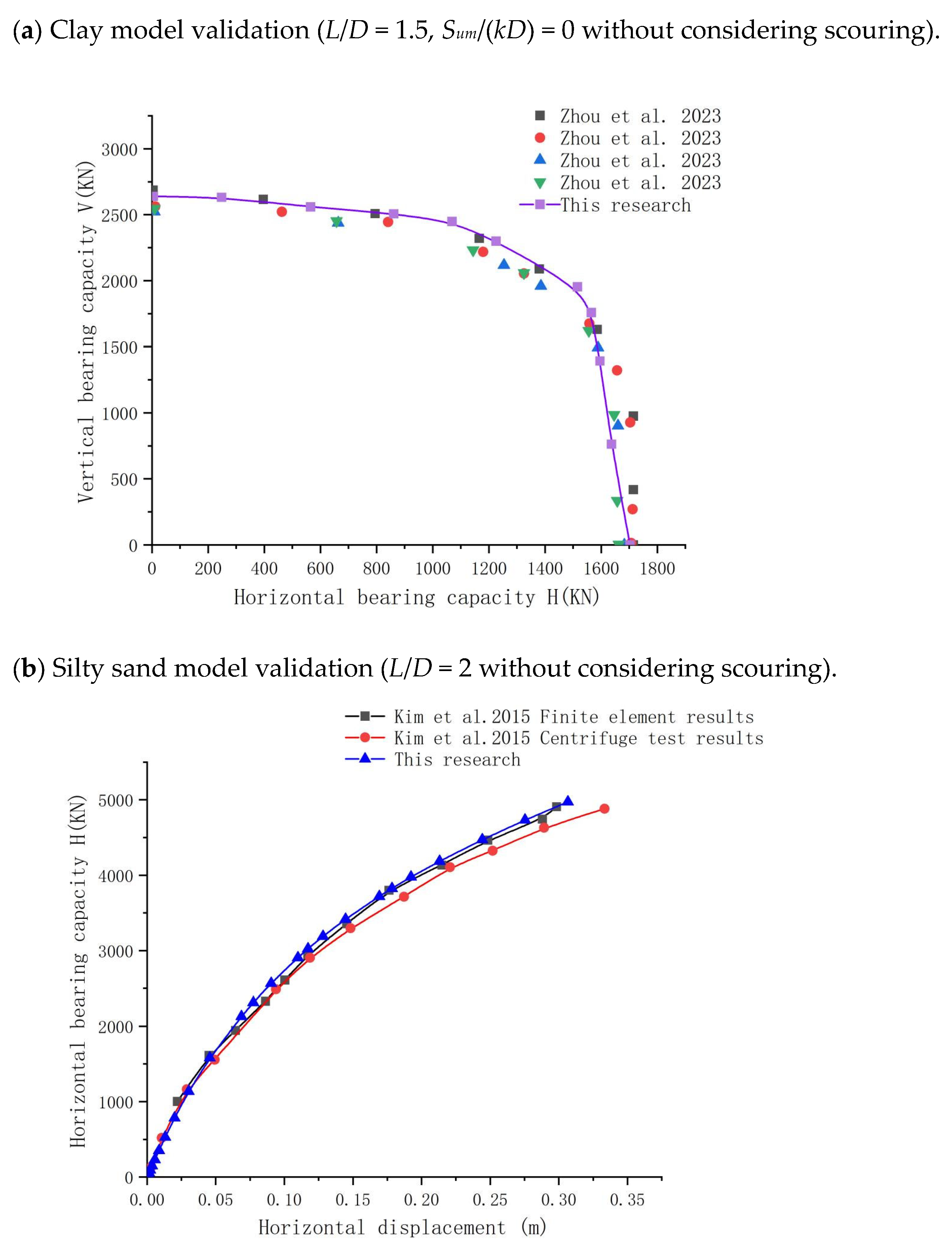

2.4. Model Validation

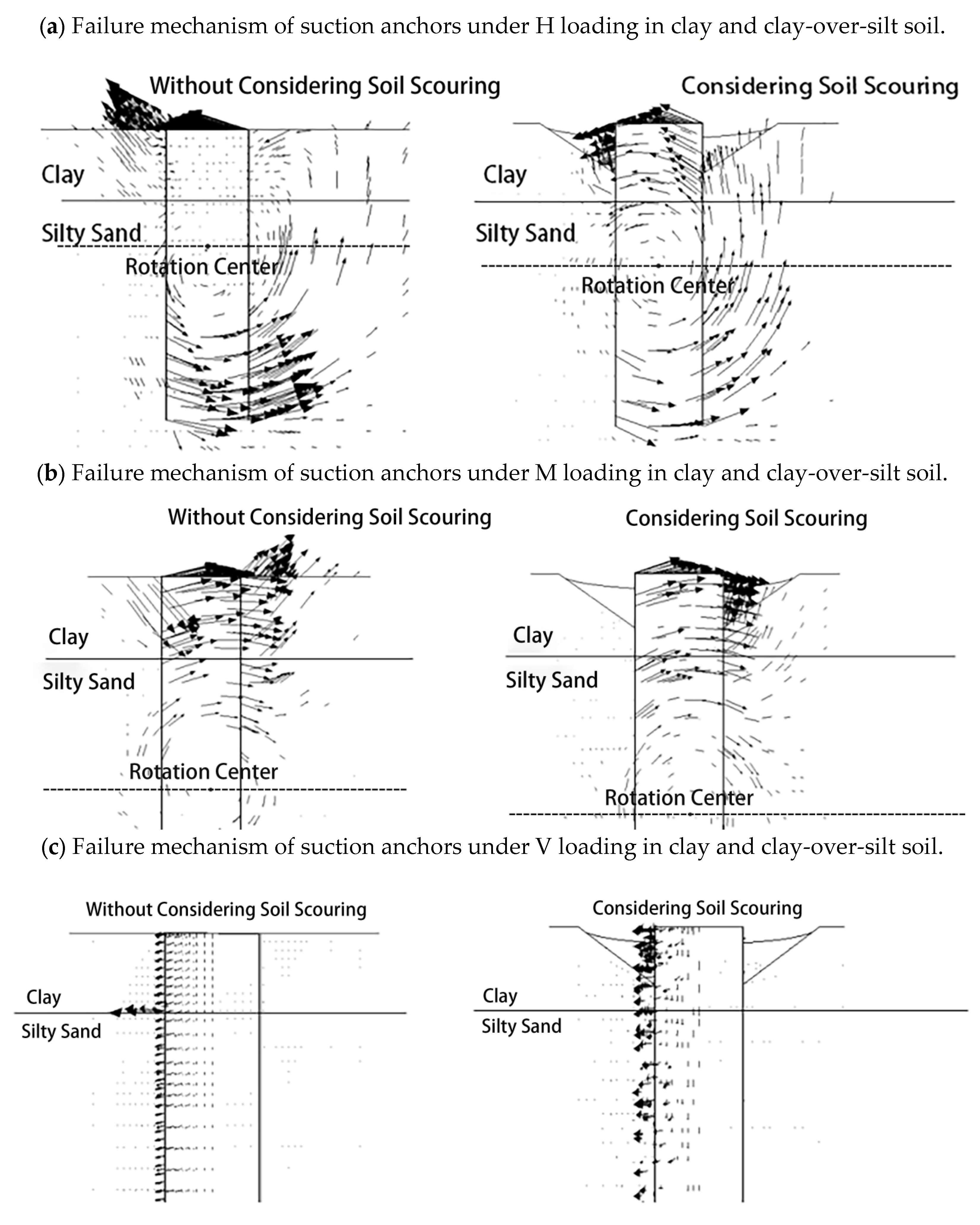

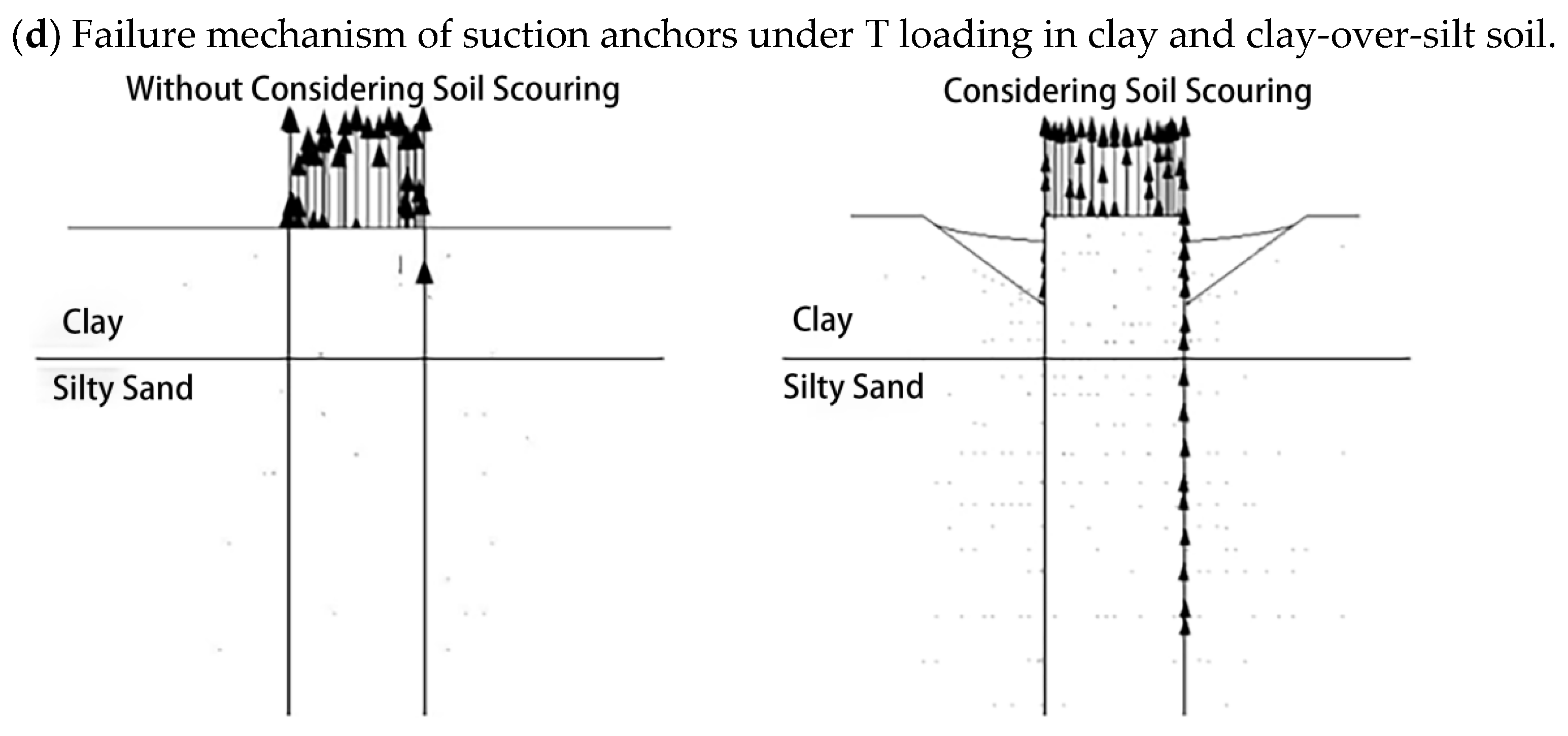

3. Soil Failure Mechanism

4. Loading Methods

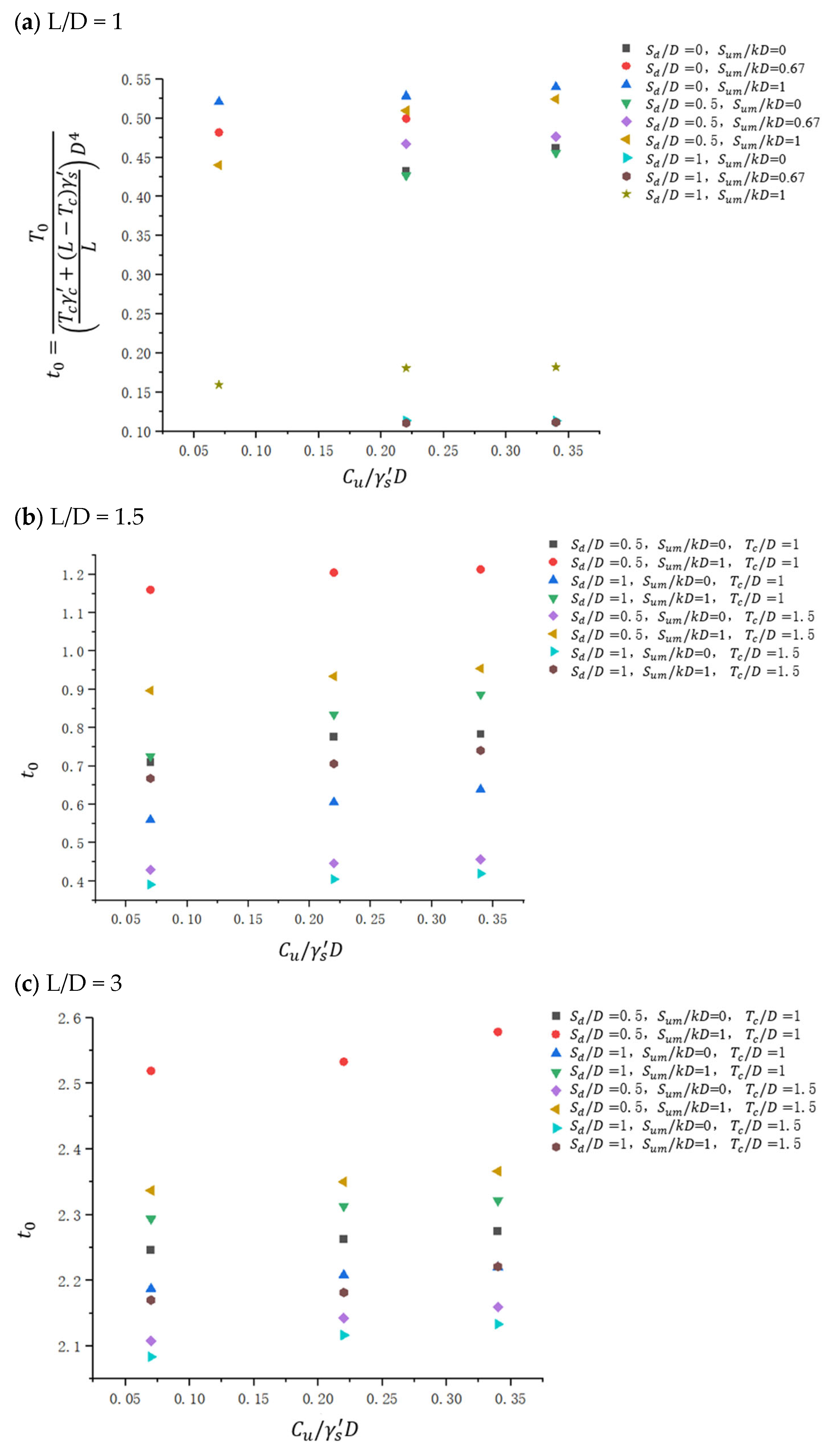

4.1. Uniaxial Loading

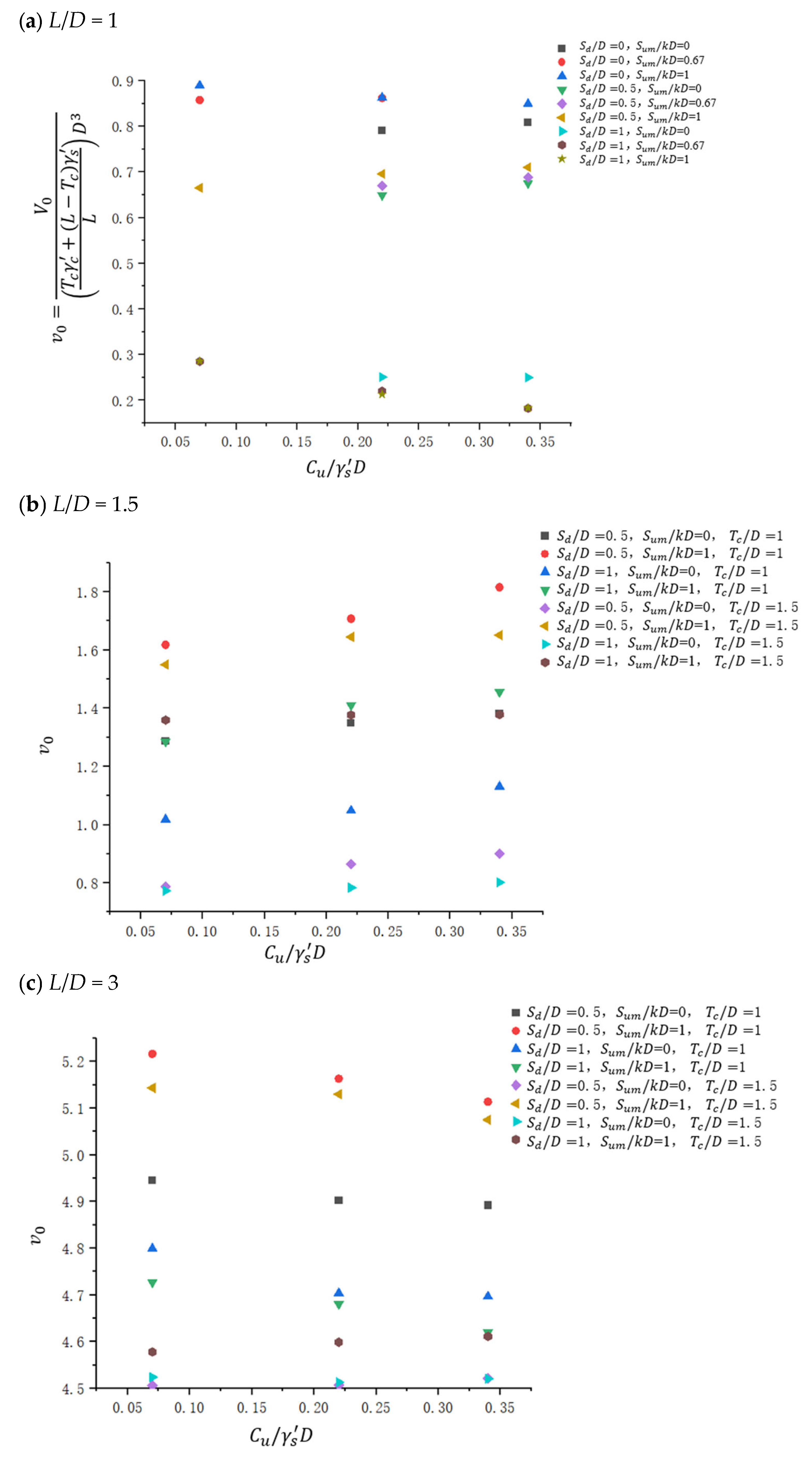

4.1.1. Uniaxial V Loading

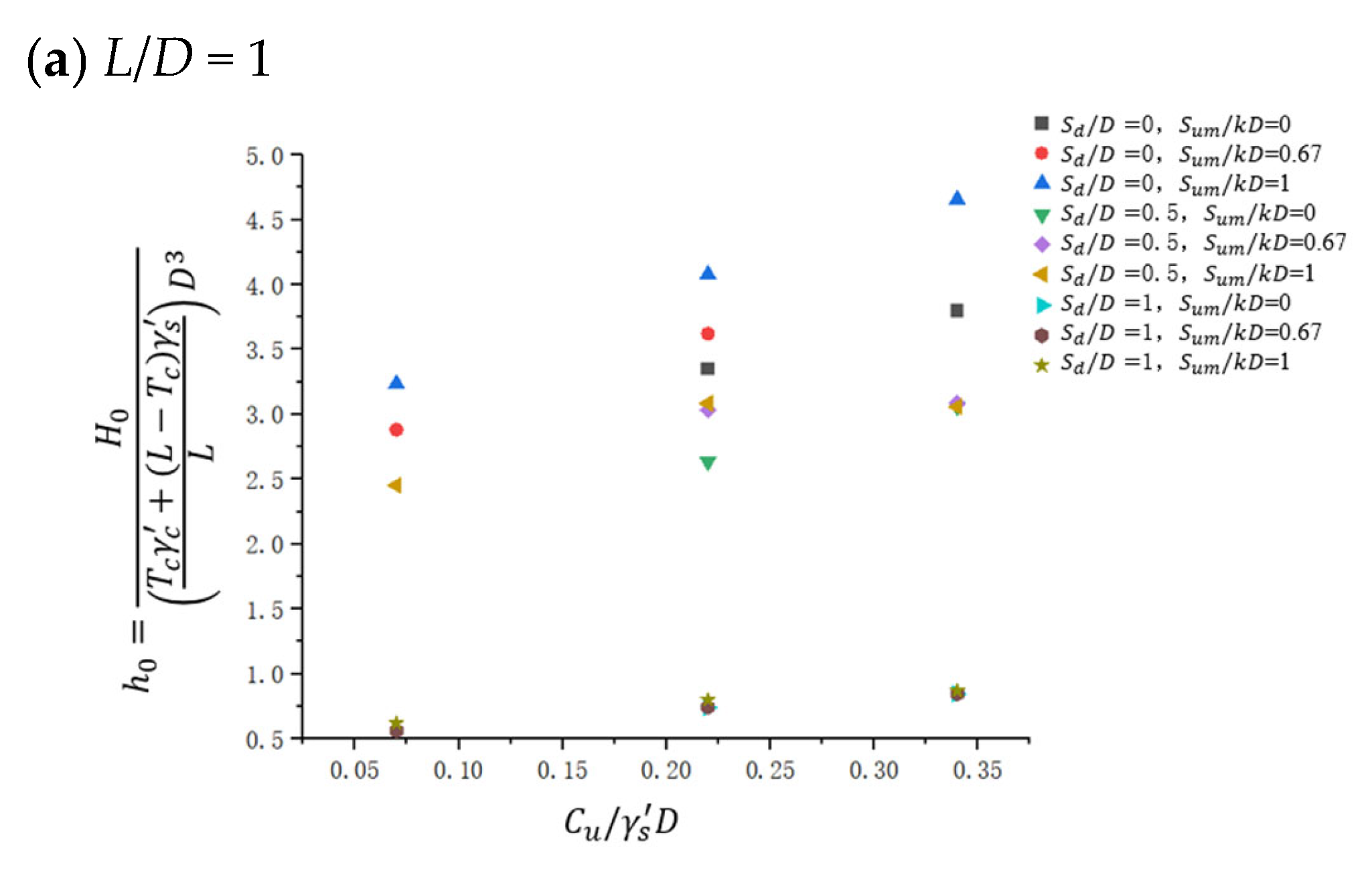

4.1.2. Uniaxial H Loading

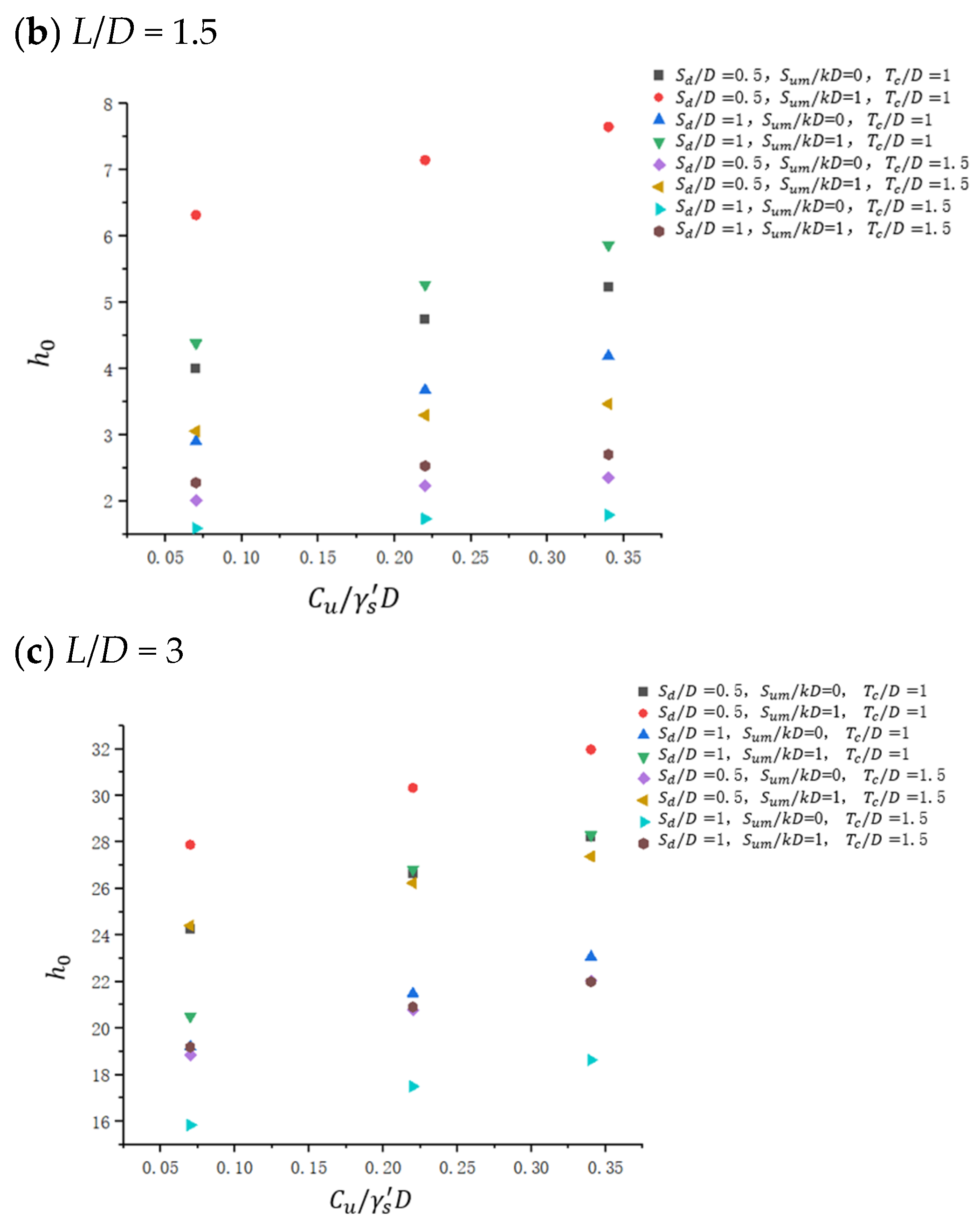

4.1.3. Uniaxial M Loading

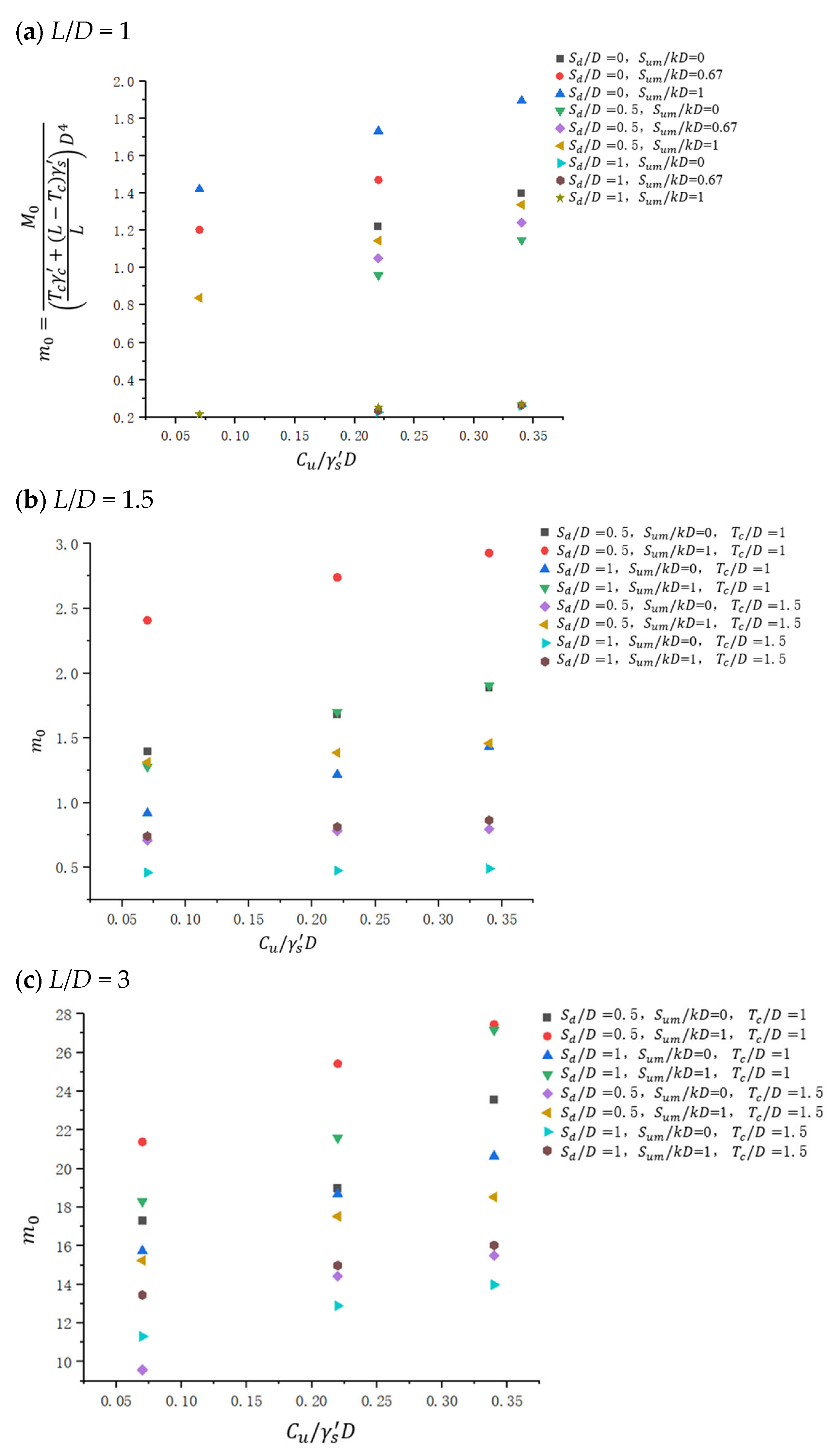

4.1.4. Uniaxial T Loading

4.2. Biaxial Combined Loading

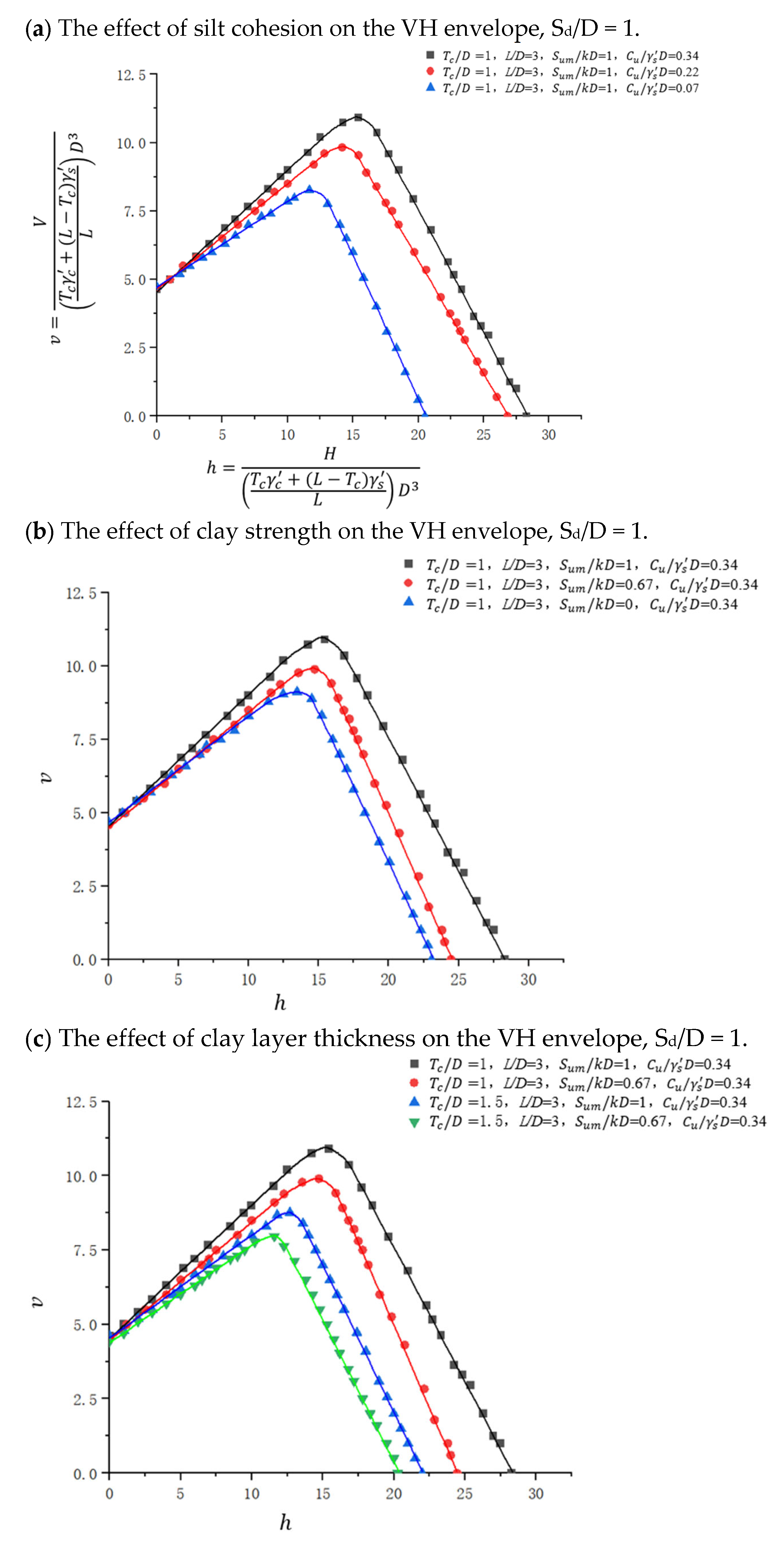

4.2.1. V-H Combined Loading

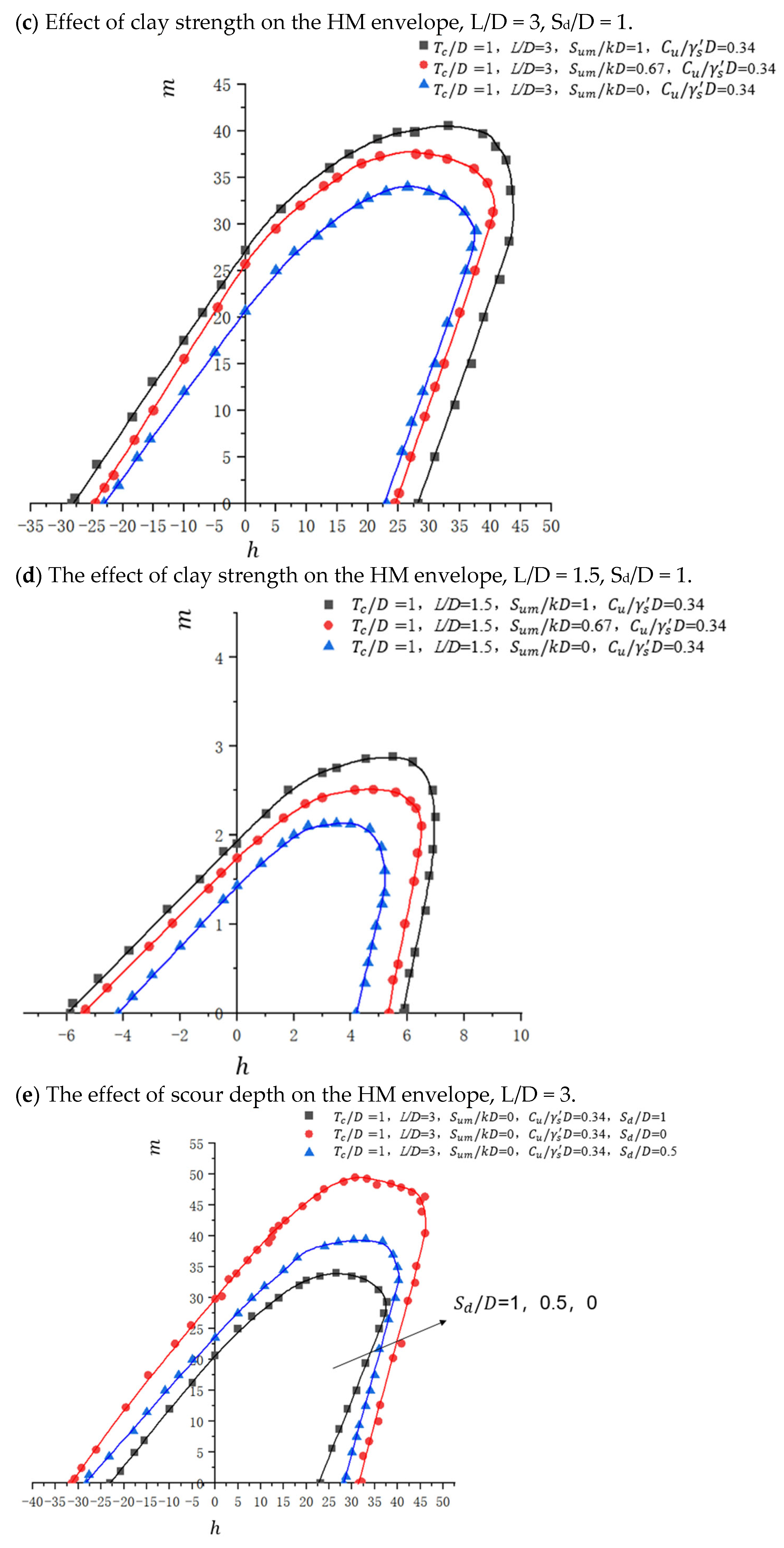

4.2.2. H–M Combined Loading

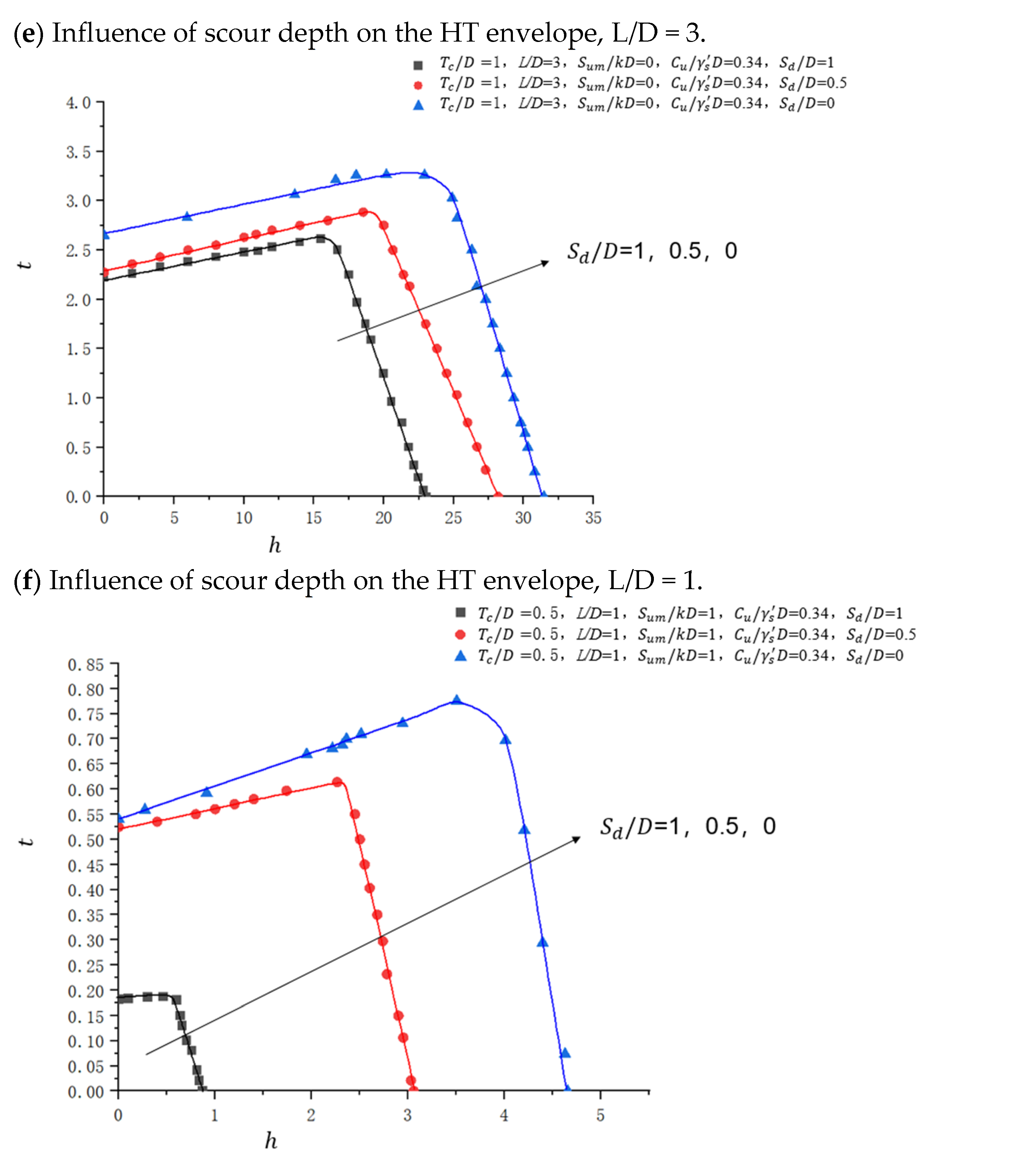

4.2.3. H–T Combined Loading

4.3. VHMT Combined Loading

- (1)

- Vertical Loading (V). In this analysis step, a concentrated upward vertical force V is applied at the center loading point at the bottom of the shared suction anchor in the global coordinate system. The range of V is 0.3V0–0.9V0, where V0 is the ultimate uniaxial bearing capacity in the vertical direction.

- (2)

- Torque Loading (T). In this analysis step, a torque T is applied at the loading point of the shared suction anchor in the global coordinate system. The range of T is 0.3T0–0.9T0, where T0 is the ultimate torque of the individually applied torque.

- (3)

- Displacement Loading (H-M). In this analysis step, a horizontal displacement U1 and a rotational displacement UR2 are applied at the loading point of the shared suction anchor in the global coordinate system. The loading is adjusted by controlling the displacement ratio.

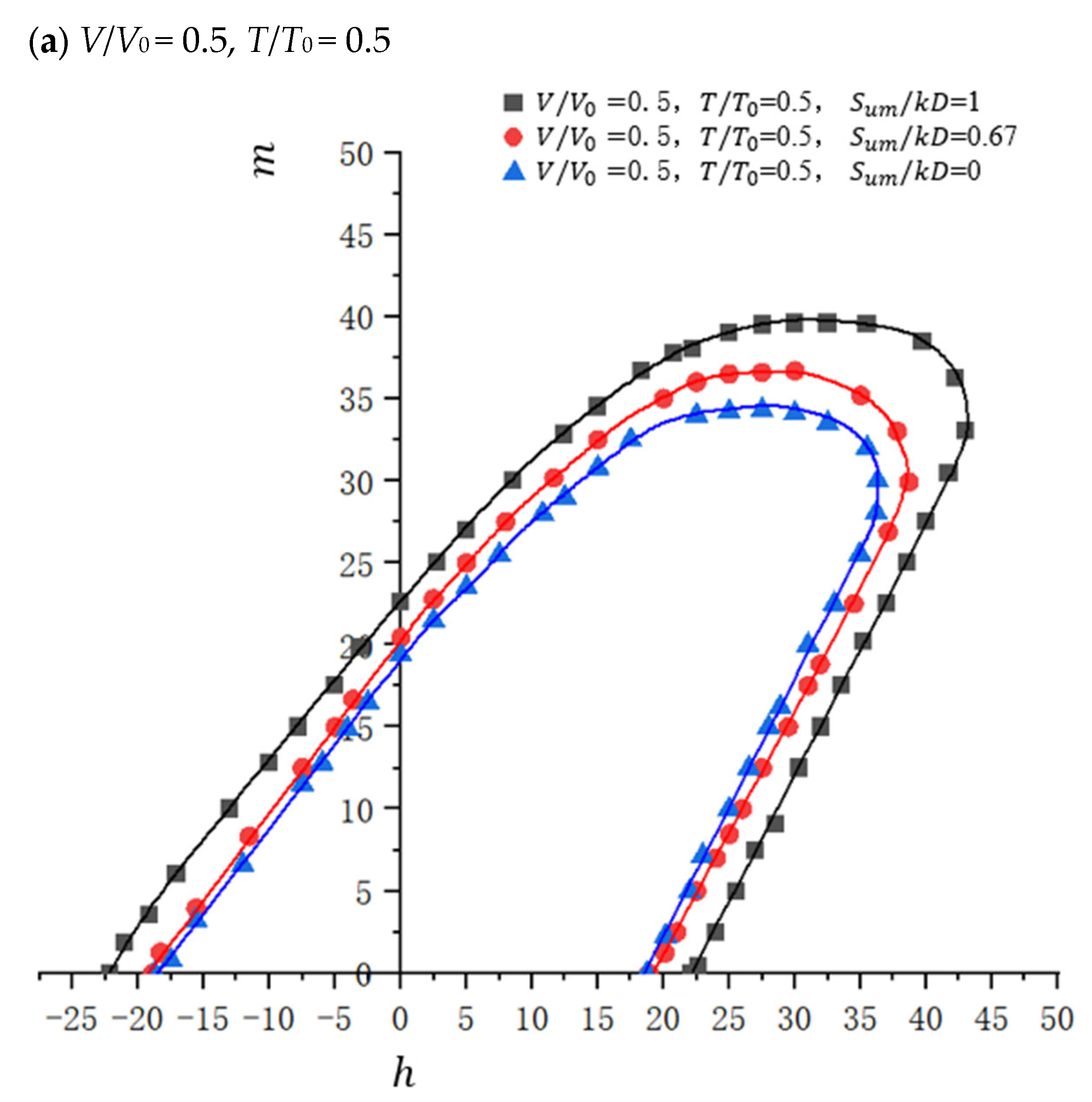

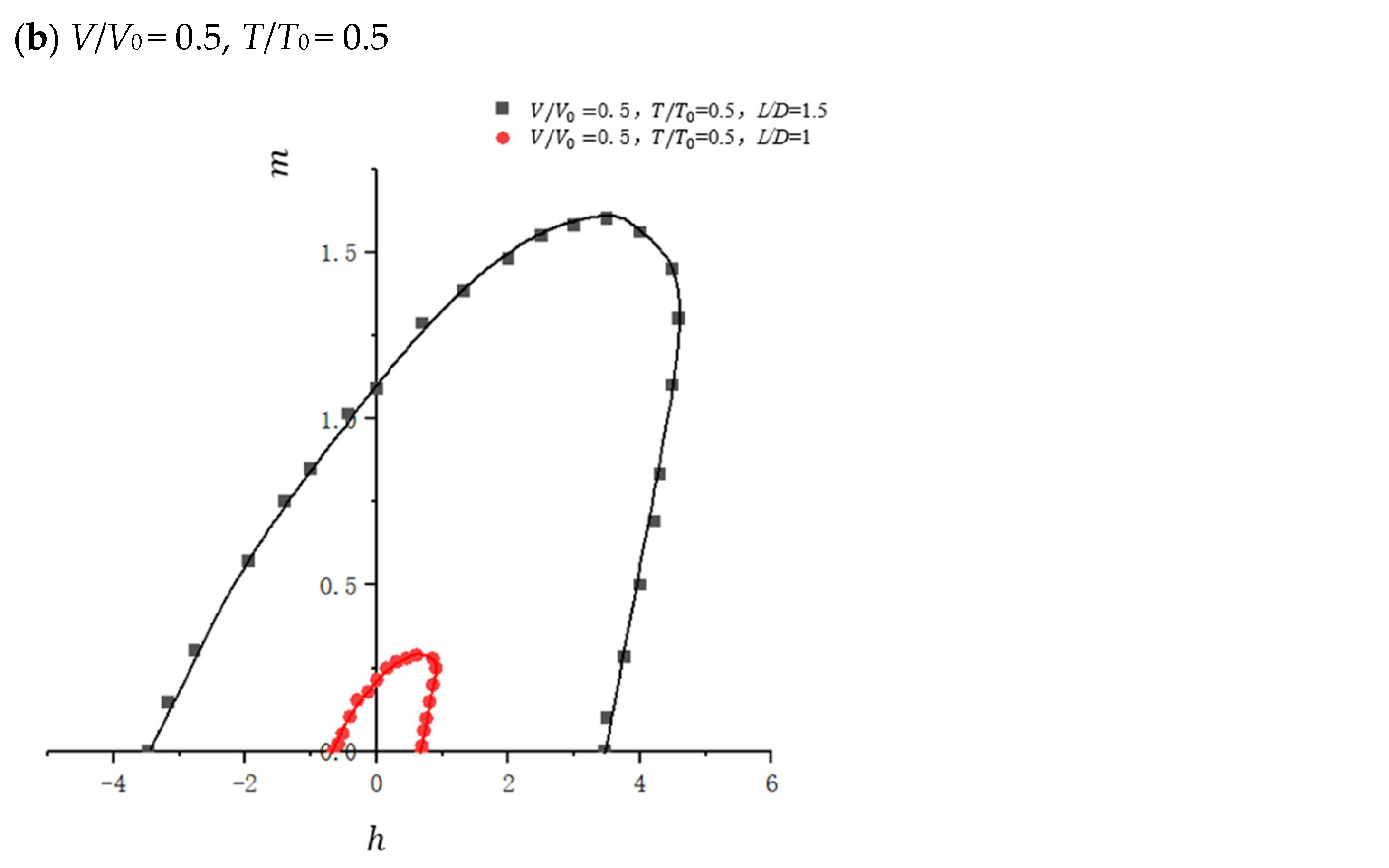

4.3.1. Influence of Changes in V/V0 and T/T0

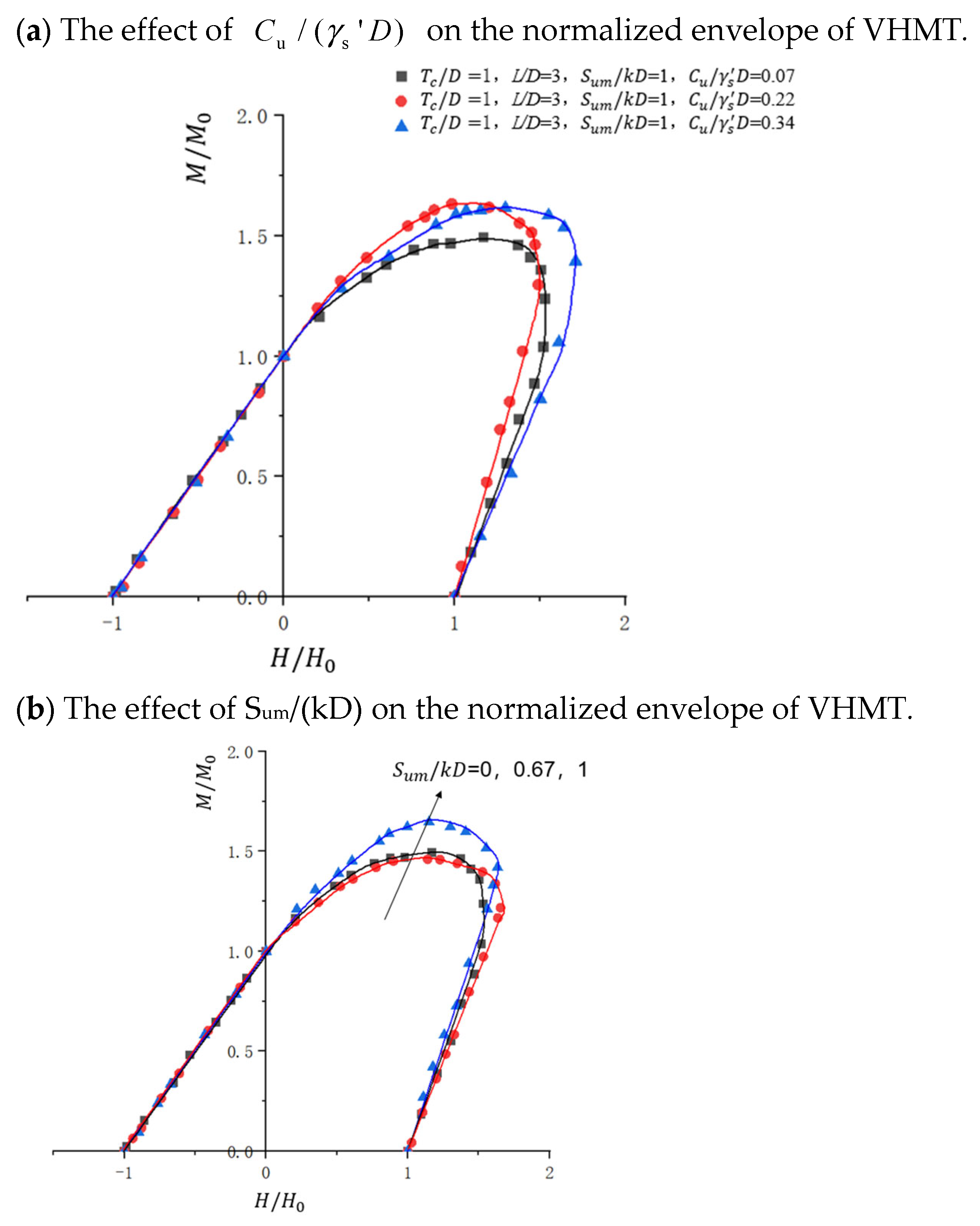

4.3.2. Influence of Changes in Soil Parameters

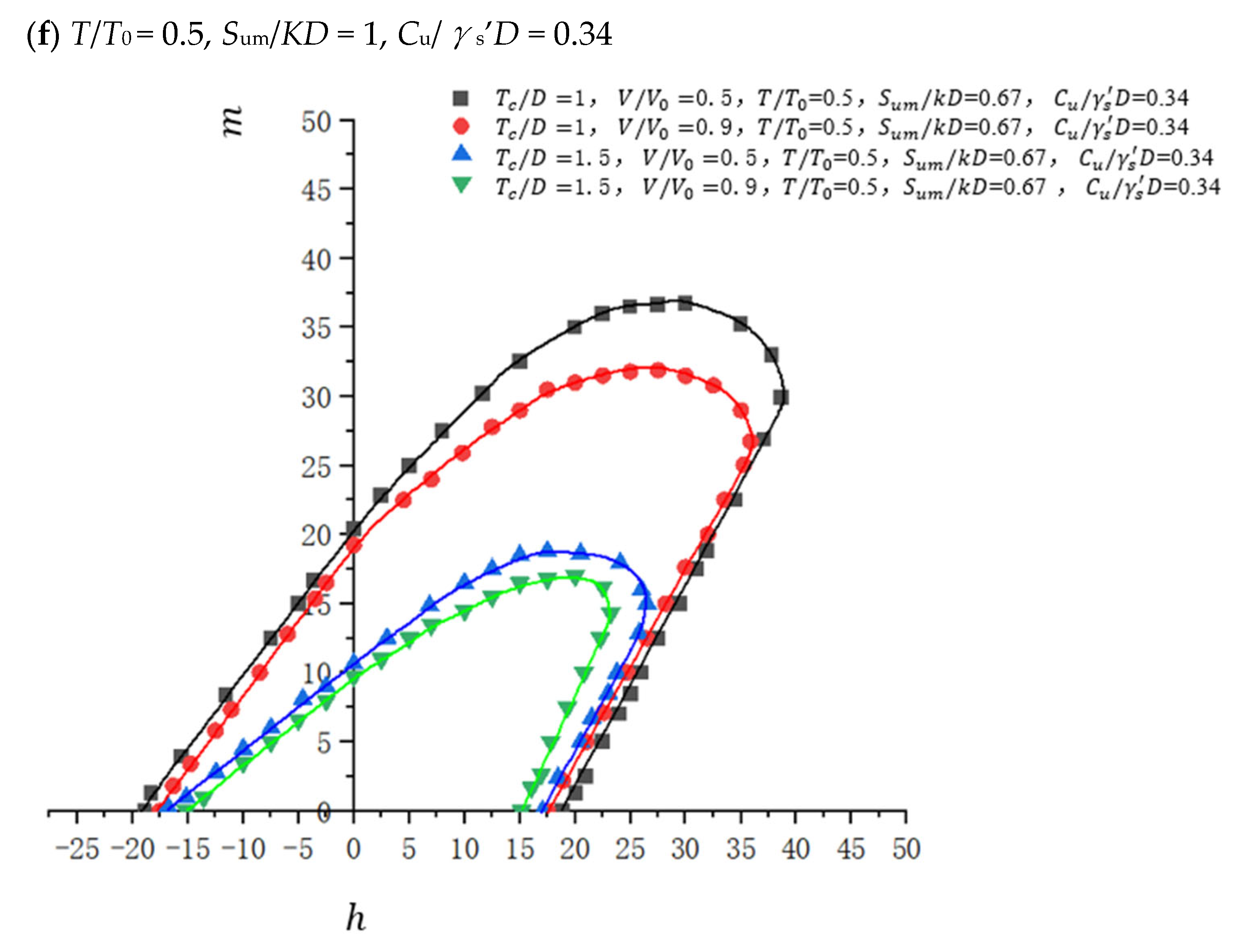

4.3.3. Influence of Changes in the Aspect Ratio of Suction Anchors

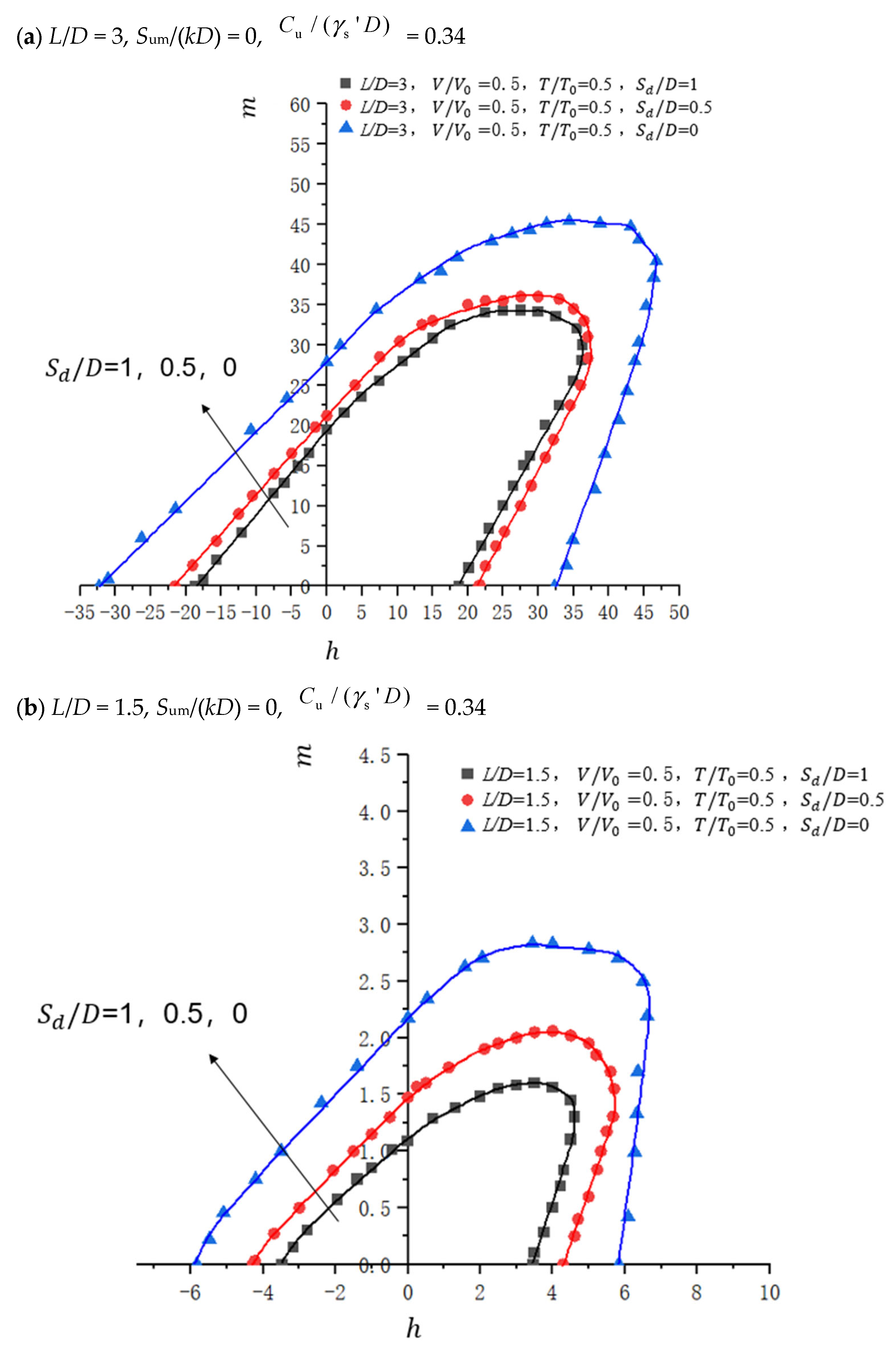

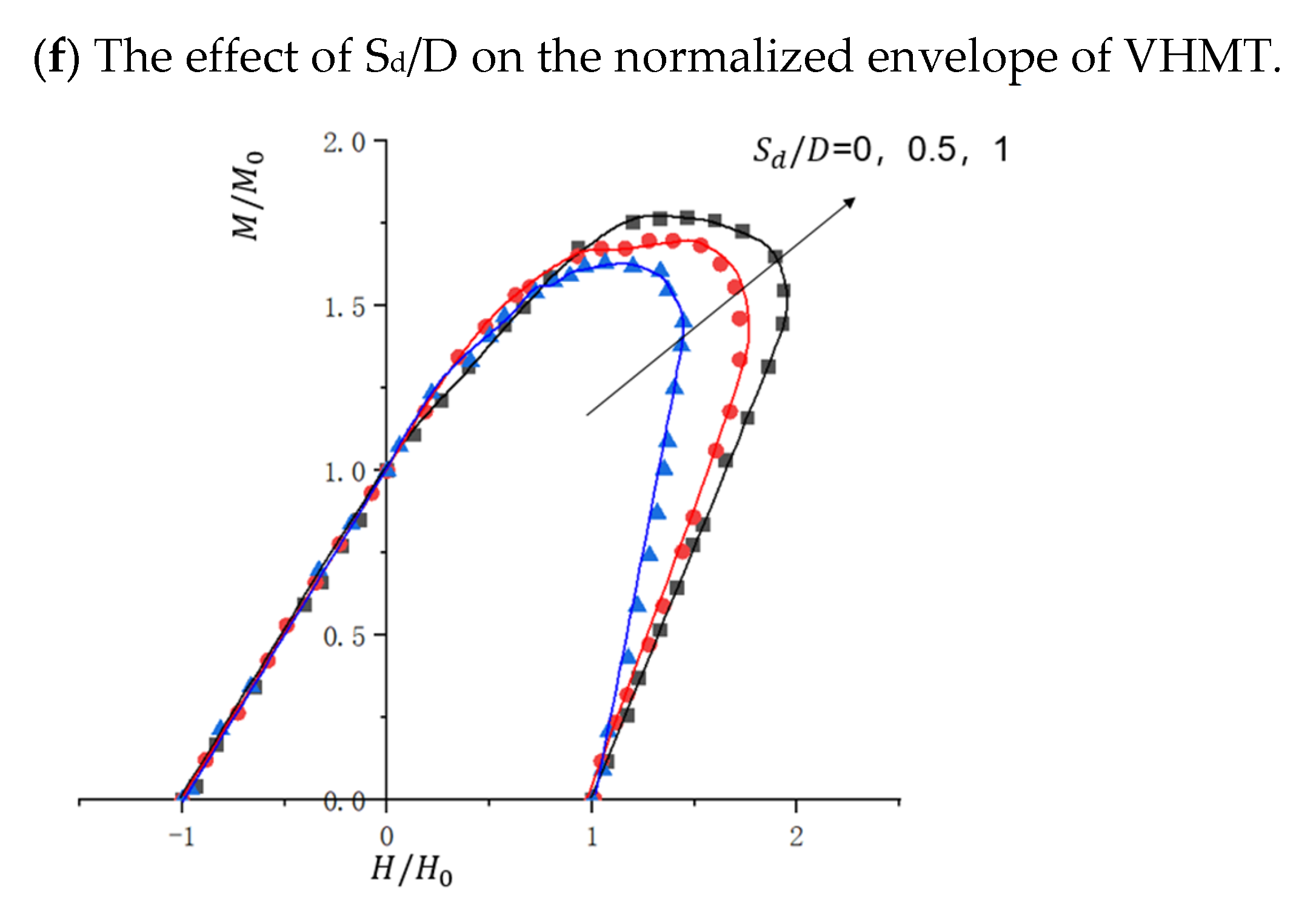

4.3.4. Influence of Changes in Scour Depth

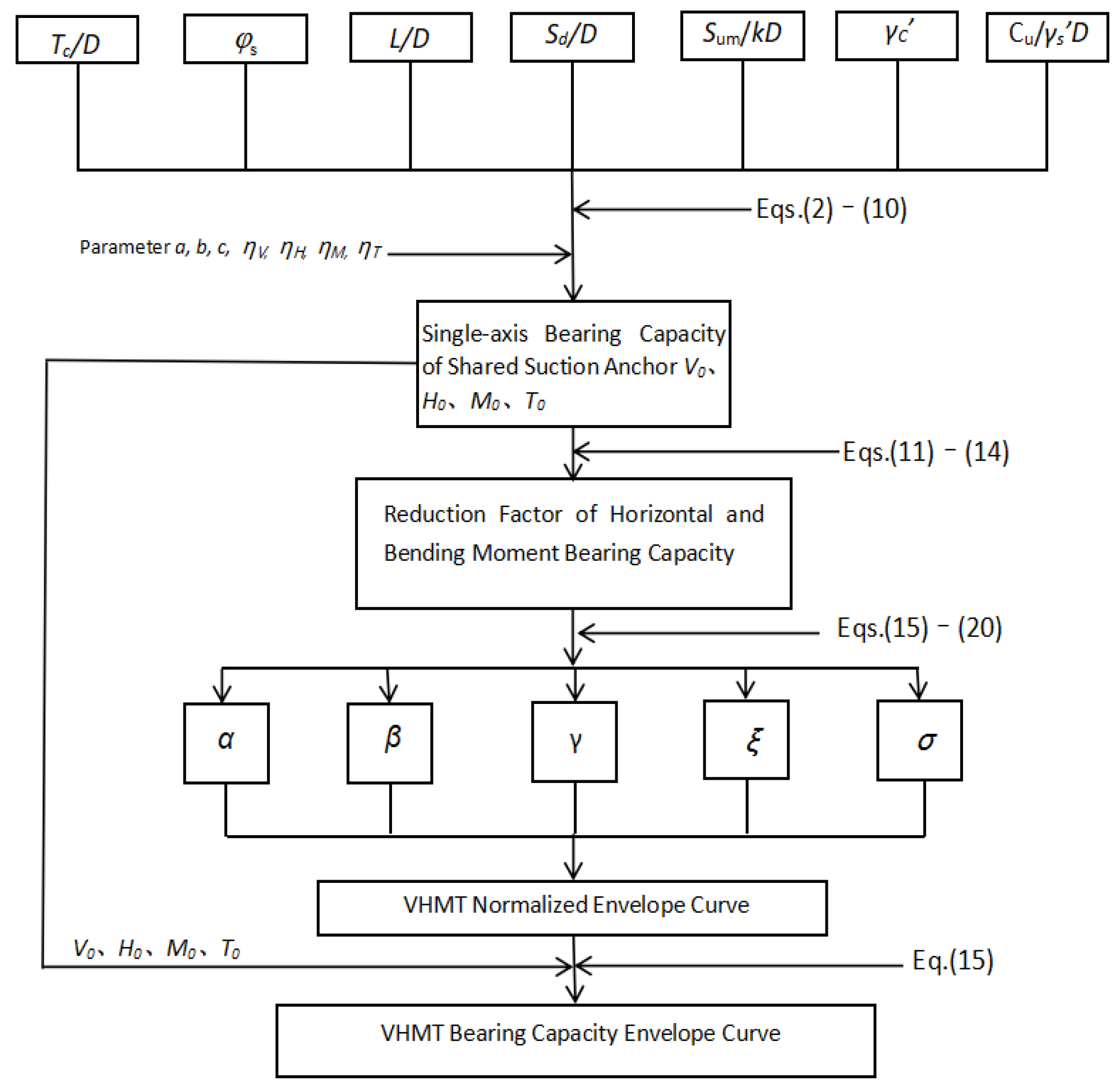

5. Proposed Design Procedure

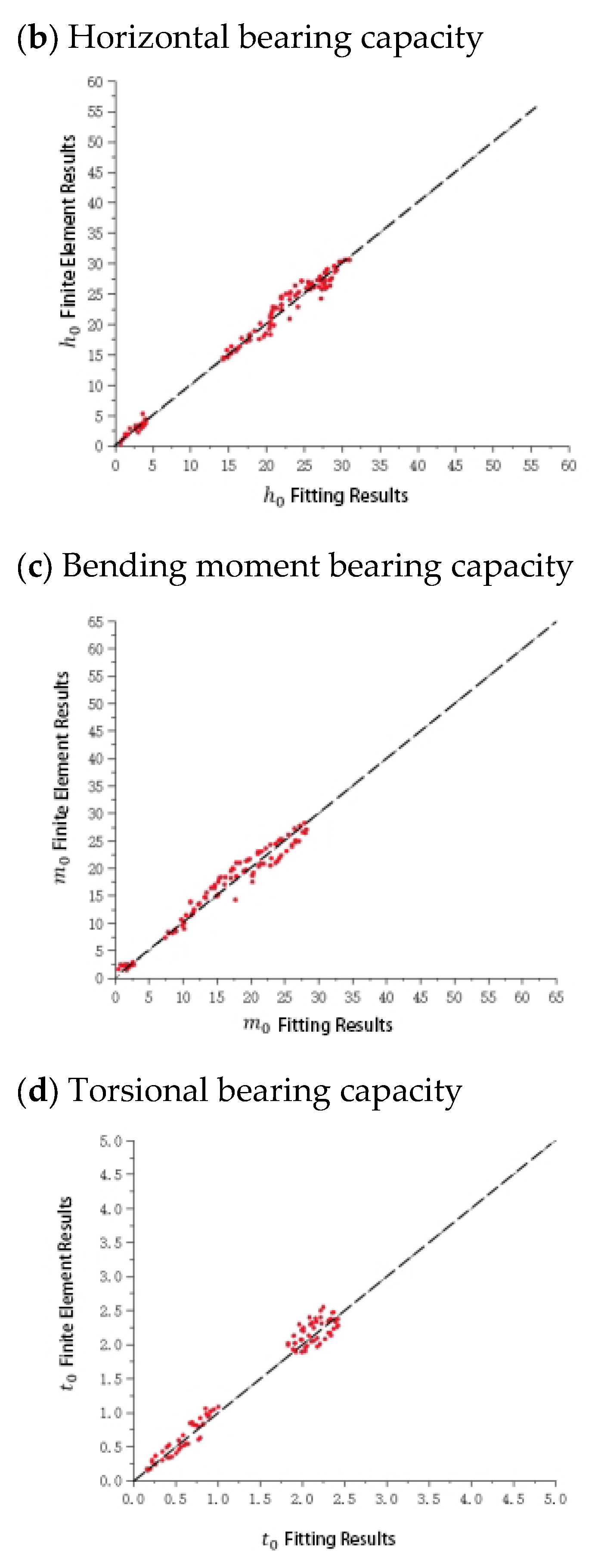

5.1. Bearing Capacity of a Single Bearing

5.2. VHMT Bearing Capacity Curve

5.3. Bearing Capacity Design

- (1)

- Based on the field survey data and soil report, determine the clay layer thickness ratio Tc/D, the suction anchor length-to-diameter ratio L/D, the normalized clay strength Sum/(kD), the normalized silt cohesion, the scour depth ratio Sd/D, the effective unit weight of clay , the effective unit weight of silt , and the silt friction angle .

- (2)

- Using Equations (2)–(10), calculate the single-bearing loads V0, H0, M0, and T0 of the suction anchor.

- (3)

- Represent H0 and M0 from step 2 as Hu and Mu, respectively. Using Equations (11)–(14), obtain the horizontal bearing capacity reduction coefficient H0/Hu and the bending moment bearing capacity reduction coefficient M0/Mu of the shared suction anchor under different V/V0 and T/T0 loading conditions, and calculate H0 and M0 under different V/V0 and T/T0 loading conditions.

- (4)

- Using Equations (15)–(20), obtain the normalized VHMT bearing capacity curve of the shared suction anchor.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- It shows that the failure mechanism of the shared anchor in the foundation without scour is different from that in the condition with scour, and the corresponding bearing capacity decreases significantly.

- (2)

- The tensional force has a significant effect on H, and the bearing capacity of T has a significant contribution to the stability of the shared suction anchor.

- (3)

- The failure mechanisms of the shared suction anchor in clay overlying silty sand and corresponding bearing envelopes are proposed to assess the bearing capacity of the shared suction anchor, which provides guidance for its application.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, Z.; Xiong, T.; Gao, X.; Tian, D.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Wang, W.; Lu, D. Study on the Structural Vibration Control of a 10 MW Offshore Wind Turbine with a Jacket Foundation Under Combined Wind, Wave, and Seismic Loads. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.H.; Jostad, H.P. Foundation design of skirted foundations and anchors in clay. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA; 3–6 May 1999; p. OTC-10824, OTC. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Newson, T. Undrained capacity of circular shallow foundations on two-layer clays under combined VHMT loading. Wind. Eng. 2023, 47, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Meng, Q. Numerical investigation and design of suction caisson for on-bottom pipelines under combined V-H-M-T loading in normal consolidated clay. Ocean Eng. 2023, 274, 113997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Zhou, Z.; Pradhan, D.L.; Yan, Y. Bearing Performance of Finned Suction Caissons under Combined VHMT Loading in Clay. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2024, 150, 04024031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, C.M.; Arwade, S.R.; DeGroot, D.J.; Myers, A.T.; Landon, M.; Aubeny, C. Efficient multiline anchor systems for floating offshore wind turbines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Busan, Republic of Korea, 19–24 June 2016; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA; Volume 49972, p. V006T09A042. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Arwade, S.R.; DeGroot, D.J.; Fontana, C.; Landon, M.; Aubeny, C.P. Comparison of multiline anchors for offshore wind turbines with spar and with semisubmersible. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1452, 12032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviano, A.; Pisanò, F. Effects of misalignment on the undrained HV capacity of suction anchors in clay. Ocean. Eng. 2017, 133, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yang, N.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X. Inclined Pullout Capacity of Suction Anchors in Clay over Silty Sand. J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 2023, 149, 4023030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, J.; Yi, P.; Feng, X.; Han, C. Effects of local scour on failure envelopes of offshore monopiles and caissons. Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 118, 103007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Zhou, M.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X. Numerical investigation on the pullout capacity of suction caissons in silty sand-over-clay deposit. Can. Geotech. J. 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.H.; Murff, J.D.; Randolph, M.F.; Clukey, E.C.; Erbrich, C.T.; Jostad, H.P.; Hansen, B.; Aubeny, C.P.; Sharma, P.; Supachawarote, C. Suction anchors for deepwater applications. In Proceedings of the 1st International Symposium on Frontiers in Offshore Geotechnics, ISFOG, Perth, WA, USA, 19–21 September 2005; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Choo, Y.W.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, D.-S.; Kwon, O. Pullout resistance of group suction anchors in parallel array installed in silty sand subjected to horizontal loading—Centrifuge and numerical modeling. Ocean Eng. 2015, 107, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Sun, C.; Liu, B.; Huang, L.; Deng, H.; Zhu, M.; Li, X.; Dai, G. Numerical Simulation on Anchored Load-Bearing Characteristics of Suction Caisson for Floating Offshore Wind Power. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lang, Y. Numerical Study on the Keying of Suction Embedded Plate Anchors with Chain Effects. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhao, H.; Jeng, D.-S. Numerical Modeling of Composite Load-Induced Seabed Response around a Suction Anchor. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.C.; Kim, S. Evaluation of Undrained Bearing Capacities of Bucket Foundations Under Combined Loads. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2014, 32, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Clay1 | Clay2 | Clay3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum (kPa) | 0.1 | 5 | 10 |

| k (kPa/m) | 1.25 | 1.5 | 2 |

| (kN/m3) | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Sum/(kD) | 0 | 0.67 | 1.0 |

| Parameter | Silt1 | Silt2 | Silt3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu (kPa) | 3 | 10 | 15 |

| (°) | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| (°) | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| (kN/m3) | 8.9 | 8.9 | 8.9 |

| 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.34 |

| Examples | Sum/(kD) | Tc/D | L/D | Sd/D | V/V0 | T/T0 | Loading Methods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Model Validation |

| 2 | 0–1 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.5–1.5 | 1–3 | 0–1 | - | - | Uniaxial Loading |

| 3a | 0–1 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.5–1.5 | 1–3 | 0–1 | - | - | V-H Combined Loading |

| 3b | 0–1 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.5–1.5 | 1–3 | 0–1 | - | - | H-M Combined Loading |

| 3c | 0–1 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.5–1.5 | 1–3 | 0–1 | - | - | H-T Combined Loading |

| 4 | 0–1 | 0.07–0.34 | 0.5–1.5 | 1–3 | 0–1 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.5–0.9 | VHMT Combined Loading |

| Tc/D | L/D | Sd/D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.88 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.95 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.92 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.89 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.22 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.70 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.79 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.84 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 1 | 0.79 |

| Tc/D | L/D | Sd/D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.66 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.87 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.87 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.19 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.55 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.64 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.64 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 1 | 0.69 |

| Tc/D | L/D | Sd/D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.59 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.68 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.66 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.14 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.36 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.38 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.67 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 1 | 0.66 |

| Tc/D | L/D | Sd/D | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.67 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.87 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.86 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.86 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.22 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.49 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.65 |

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 0.84 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 1 | 0.81 |

| Tc/D | L/D | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.07 | −0.02 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.62 | 0.26 | 0.12 |

| 1 | 3 | 5.00 | 0.41 | −0.19 |

| 1 | 3.5 | 6.18 | 0.43 | −0.25 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.08 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 4.61 | 0.84 | −0.17 |

| 1.5 | 3.5 | 5.75 | 0.99 | −0.18 |

| 2 | 3 | 4.14 | 1.27 | −0.06 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 5.34 | 0.97 | −0.27 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 4.45 | 1.59 | 0.03 |

| Tc/D | L/D | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 4.63 | 0.75 | 1.98 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 7.58 | 1.78 | 2.17 |

| 1 | 3 | 34.40 | 6.74 | 9.02 |

| 1 | 3.5 | 50.22 | 5.73 | 10.78 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.86 | 1.25 | 0.60 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 26.39 | 5.60 | 4.52 |

| 1.5 | 3.5 | 39.87 | 7.58 | 7.97 |

| 2 | 3 | 21.45 | 5.03 | 5.03 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 30.10 | 7.49 | 4.88 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 17.47 | 6.62 | 2.98 |

| Tc/D | L/D | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 1.68 | 0.50 | 0.69 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 2.98 | 1.45 | 0.92 |

| 1 | 3 | 39.47 | 6.43 | 22.59 |

| 1 | 3.5 | 61.04 | 9.61 | 27.18 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.23 | 0.90 | 0.23 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 23.25 | 4.27 | 8.00 |

| 1.5 | 3.5 | 48.69 | 7.89 | 22.05 |

| 2 | 3 | 11.59 | 5.11 | 2.49 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 26.26 | 6.25 | 9.78 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 10.10 | 7.40 | 1.00 |

| Tc/D | L/D | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.05 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.36 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| 1 | 3 | 2.75 | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| 1 | 3.5 | 3.05 | 0.29 | 0.27 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.33 | 0.68 | 0.05 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 2.40 | 0.32 | 0.12 |

| 1.5 | 3.5 | 2.96 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| 2 | 3 | 2.00 | 0.51 | 0.10 |

| 2 | 3.5 | 2.67 | 0.44 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 3.5 | 2.08 | 1.11 | 0.40 |

| Tc/D | L/D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.85 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.87 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.86 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.7 | 0.86 |

| Tc/D | L/D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.22 |

| 1 | 1.5 | 0.70 | 0.55 | 0.36 | 0.49 |

| 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.38 | 0.65 |

| 1 | 3 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.84 |

| 1.5 | 3 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Liang, K.; Zhou, M.; Yang, N. Behavior of Shared Suction Anchors in Clay Overlying Silty Sand Soils Considering the Souring Effect. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122394

Wang J, Liang K, Zhou M, Yang N. Behavior of Shared Suction Anchors in Clay Overlying Silty Sand Soils Considering the Souring Effect. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122394

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jinyi, Kai Liang, Mi Zhou, and Ningxin Yang. 2025. "Behavior of Shared Suction Anchors in Clay Overlying Silty Sand Soils Considering the Souring Effect" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122394

APA StyleWang, J., Liang, K., Zhou, M., & Yang, N. (2025). Behavior of Shared Suction Anchors in Clay Overlying Silty Sand Soils Considering the Souring Effect. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2394. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122394