Emissions Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Marine Genset Combusting Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Retrofits for the Marine Genset to Combust Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode

2.1. Marine Genset Specifications

2.2. Retrofits on Marine Genset

3. Experimental Methodology, Measurement Campaigns, and Datalogging

3.1. Biomethane Composition

3.2. Experimental Setup, Measurement Campaigns, and Datalogging

4. Results and Discussion

- A lower engine efficiency (especially at low and intermediate loads) was observed in this case for the dual-fuel mode compared to diesel-only operation, similar to the observations obtained by Papagiannakis et al. [18]. This is due to a lower control of the premixed combustion rate as opposed to diesel-only operation.

- Improvements were found in engine efficiency and overall performance at high loads due to a better utilization of the gaseous fuel under dual-fuel mode compared to diesel-only conditions.

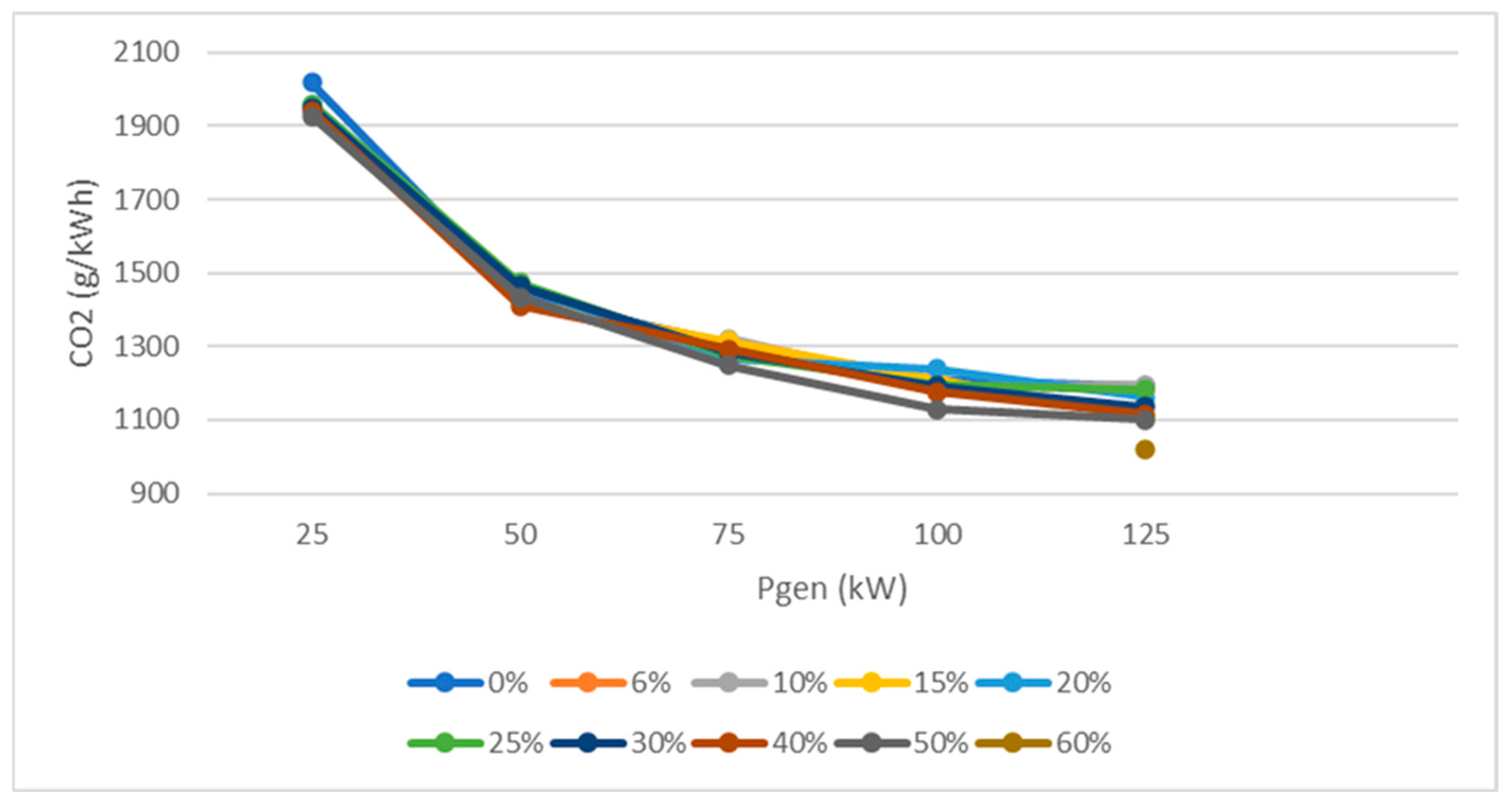

- Lower CO2 emissions at higher loads are observed in the diesel-only measurements due to an improvement in the specific fuel consumption. This is also confirmed by Papagiannakis et al. [18].

- CO2 emissions seem unaltered irrespective of biomethane energy substitution. However, in a lifecycle analysis, a percentage of the CO2 emissions are accounted for due to their “green” source (biomethane). Note that, in terms of lifecycle assessments, methane has a very potent GWP compared to CO2. Thus, by combusting bioCH4, instead of it being naturally decomposed and released into the atmosphere, it is effectively removed from the environment. Therefore, the same number of CO2 molecules are produced, but with significantly less of a greenhouse effect.

- Valve timing control combined with liquid fuel injection control could potentially reduce the biomethane slip and improve the quality of combustion. Such an investigation goes beyond the objectives of the current research, also requiring an experimental setup that supports both control strategies.

- The injection timing of biomethane in the air manifold as currently retrofitted in the engine does not affect the parameters examined; it is not related to the thermodynamic cycle.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallouppas, G.; Yfantis, E.A. Decarbonization in Shipping Industry: A Review of Research, Technology Development, and Innovation Proposals. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallouppas, G.; Yfantis, E.; Ioannou, C.; Paradeisiotis, A.; Ktoris, A. Application of Biogas and Biomethane as Maritime Fuels: A Review of Research, Technology Development, Innovation Proposals, and Market Potentials. Energies 2023, 16, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMMI Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute. Net-Zero-Emissions-CI: Towards bioCNG as a Carbon Negative Maritime Power Source. CMMI Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute. 2025. Available online: https://www.cmmi.blue/net-zero-emissions-ci/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Mallouppas, G.; Ktoris, A.; Yfantis, E.A.; Petrakides, S.; Drousiotis, M. A lifecycle analysis of a floating power plant using biomethane as a drop-in fuel for cold-ironing of vessels at anchorage. Energies 2025, 18, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.-K.; Hwang, K.-R.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.-S. Recent developments and key barriers to advanced biofuels: A short review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 257, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelissen, D.; Faber, J.; van der Veen, R.; van Grinsven, A.; Shanthi, H.; van den Toorn, E. Availability and Costs of Liquefied Bio- and Synthetic Methane. The Maritime Shipping Perspective; CE Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. The Biofuels Market: Current Situation and Alternative Scenarios; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland; New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nisiforou, O.; Shakou, L.; Margou, A.; Charalambides, A. A Roadmap towards the Decarbonization of Shipping: A Participatory Approach in Cyprus. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerkan, K.Y.; Seter, H. Reviewing tools and technologies for sustainable ports: Does research enable decision making in ports? Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 72, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfantis, E.; Mallouppas, G.; Ktoris, A.; Ioannou, C. Fit for 55—Impact on Cypriot shipping industry. In Preliminary Report—Assessment of the New Measures and Their Effect on the Shipping Industry and the Relevant Cyprus Economy Sectors; Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute: Larnaka, Cyprus, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive review of energy storage systems technologies, objectives, challenges, and future trends. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, M.Y. Recent Advances in Energy Storage Systems for Renewable Source Grid Integration: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, H.; Faaij, A. A review at the role of storage in energy systems with a focus on Power to Gas and long-term storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1049–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyprus Marine and Maritime Institute. BioCH4-to-Market: BioMethane as a Drop-In Marine Biofuel: Developing a Virtual Gas-Grid Solution; CMMI: Larnaca, Cyprus, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- AMETEK Land. Lancom 4 User Guide; AMETEK Land: Dronfield, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MRU Gmbh. User Manual VARIOluxx; MRU Gmbh: Neckarsulm, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Technoton. DFM Flow Meters. DFM 50/100/250/500 One-Chamber and Differential, version 8.1; Technoton: Prague, Czech Republic, 2021.

- Papagiannakis, R.G.; Hountalas, D.T.; Rakopoulos, C.D.; Rakopoulos, D.C. Combustion and Performance Characteristics of a DI Diesel Engine Operating from Low to High Natural Gas Supplement Ratios at Various Operating Conditions; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2008; Volume 2008-01-1392, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cengel, Y.; Boles, M.; Kanoglu, M. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 9th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, A.; Yadav, M.S.A.; Singh, G. Proceedings of International Conference in Mechanical and Energy Technology, Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies 174. In Chapter 30: Methane–Diesel Dual Fuel Engine: A Comprehensive Review; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2020; pp. 327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bouguessa, R.; Tarabet, L.; Loubar, K.; Belmrabet, T.; Tazerout, M. Experimental investigation on biogas enrichment with hydrogen for improving the combustion in diesel engine operating under dual fuel mode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 9052–9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.P.; Acharya, S.K. Investigation on influence of thermal barrier coating on diesel engine performance and emissions in dual-fuel mode using upgraded biogas. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2019, 29, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Neill, W.S.; Liko, B. The Combustion and Emissions Performance of a Syngas-Diesel Dual Fuel Compression Ignition Engine. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 Internal Combustion Engine Division Fall Technical Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection, Greenville, SC, USA, 9–12 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Q.; Park, S.; Agarwal, A.K.; Park, S. Review of dual-fuel combustion in the compression-ignition engine: Spray, combustion, and emission. Energy 2022, 250, 123778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seboldt, D.; Lejsek, D.; Bargende, M. Injection strategies for low HC raw emissions in SI engines with CNG direct injection. Automot. Engine Technol. 2016, 1, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabson, C.; Faghani, E.; Kheirkhah, P.; Kirchen, P.; Rogak, S.; McTaggart-Cowan, G. Combustion and Emissions of Paired-Nozzle Jets in a Pilot-Ignited Direct-Injection Natural Gas Engine; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, R.; Neely, G.D.; Abidin, Z.; Miwa, J. Efficiency and Emissions Characteristics of Partially Premixed Dual-Fuel Combustion by Co-Direct Injection of NG and Diesel Fuel (DI 2); SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTaggart-Cowan, G.; Mann, K.; Huang, J.; Singh, A.; Patychuk, B.; Zheng, Z.X.; Munshi, S. Direct Injection of Natural Gas at up to 600 Bar in a Pilot-Ignited Heavy-Duty Engine; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Displacement (lt) | 14 |

| Engine speed (rpm) | 1500 |

| Bore (mm) | 140 |

| Stroke (mm) | 152 |

| Fuel system | Direct injection |

| Number of cylinders | 6 |

| Power (kW) | 180 @1500 rpm (100% load) |

| Aspiration | Turbocharged |

| Type | Biomethane Composition |

|---|---|

| Water (%) | 0.0 |

| O2 (%) | 0.0 |

| CH4 (%) | 94.30 |

| CO2 (%) | 4.39 |

| H2S (ppm) | 10 |

| N2 (computed) (%) | 1.31 |

| Sensor ID | Description [unit] |

|---|---|

| S1 | Mass air flow rage [kg/h] |

| S2 | Intake air temperature [°C] |

| S3 | Intake air manifold absolute pressure [bar] |

| S4 | Diesel flow meter [L/h] |

| S5 | Lambda [-λ] & NOx [ppm] |

| S6 | Biomethane injection pressure [bar] |

| S7 | Biomethane storage pressure [bar] |

| S8 | CH4 slip [ppm] |

| S9 | Ambient air temperature [°C] |

| S10 | Gas analyzer; CO, SO2, O2, NO2, NO (NOx as cumulative of NO2 and NO), CxHy, CO2, and water vapor) + flue gas temperature and ambient air temperature [°C] |

| S11 | Thermal camera |

| S12 | Exhaust temperature sensors per cylinder [°C] |

| S13 | Reducer water temperature [°C] |

| S14 | Engine speed [rpm] |

| Fuel Type | Test Type | Load Conditions (kW) Engine Power: 147 kW | Drop in % (Linked to Biomethane Flow Rate) * | Engine (rpm) ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGO | Baseline reference | 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 | n/a | 1500 |

| MGO + BioCH4 | 25, 50, 75, 100, 125 | 6, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 | 1500 |

| Pgen (kW) | Energy Replacement (%) | Ambient Air Temperature (K) | Estimated Air–Biomethane Mixture Temperature (K) | Air Pressure (kPa) | Cp (kJ/kg.K) | Cv (kJ/kg.K) | Estimated k (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0% | 307.52 | 317.11 | 112.833 | 1.0050 | 0.7180 | 1.399721 |

| 20% | 306.73 | 316.45 | 113.026 | 1.0080 | 0.7204 | 1.399144 | |

| 25% | 306.48 | 316.42 | 113.325 | 1.0089 | 0.7212 | 1.398964 | |

| 30% | 306.28 | 316.21 | 113.325 | 1.0100 | 0.7221 | 1.398754 | |

| 40% | 306.66 | 316.60 | 113.325 | 1.0121 | 0.7238 | 1.398341 | |

| 50% | 306.19 | 316.89 | 114.325 | 1.0148 | 0.7260 | 1.397830 | |

| 50 | 0% | 309.29 | 325.61 | 121.311 | 1.0050 | 0.7180 | 1.399721 |

| 15% | 311.83 | 328.48 | 121.591 | 1.0081 | 0.7205 | 1.399121 | |

| 20% | 311.22 | 329.04 | 123.165 | 1.0090 | 0.7212 | 1.398950 | |

| 25% | 308.00 | 325.74 | 123.325 | 1.0102 | 0.7223 | 1.398705 | |

| 30% | 312.18 | 330.16 | 123.325 | 1.0115 | 0.7233 | 1.398460 | |

| 40% | 312.75 | 331.50 | 124.325 | 1.0147 | 0.7259 | 1.397850 | |

| 50% | 314.03 | 333.62 | 125.368 | 1.0177 | 0.7284 | 1.397265 | |

| 75 | 0% | 304.69 | 329.23 | 132.891 | 1.0050 | 0.7180 | 1.399721 |

| 10% | 305.46 | 332.14 | 135.880 | 1.0075 | 0.7200 | 1.399240 | |

| 15% | 304.56 | 331.46 | 136.325 | 1.0086 | 0.7210 | 1.399012 | |

| 20% | 305.56 | 333.21 | 137.325 | 1.0104 | 0.7224 | 1.398677 | |

| 25% | 304.79 | 332.36 | 137.325 | 1.0119 | 0.7236 | 1.398379 | |

| 30% | 305.11 | 332.70 | 137.325 | 1.0133 | 0.7248 | 1.398112 | |

| 40% | 303.83 | 332.56 | 139.209 | 1.0165 | 0.7274 | 1.397502 | |

| 50% | 301.60 | 331.49 | 141.321 | 1.0205 | 0.7306 | 1.396746 | |

| 100 | 0% | 308.94 | 342.03 | 144.696 | 1.0050 | 0.7180 | 1.399721 |

| 10% | 301.88 | 335.86 | 147.272 | 1.0080 | 0.7204 | 1.399143 | |

| 15% | 301.83 | 336.64 | 148.594 | 1.0095 | 0.7217 | 1.398841 | |

| 20% | 302.46 | 337.80 | 149.325 | 1.0109 | 0.7228 | 1.398581 | |

| 25% | 302.05 | 337.32 | 149.325 | 1.0128 | 0.7243 | 1.398218 | |

| 30% | 301.89 | 337.76 | 150.325 | 1.0145 | 0.7257 | 1.397889 | |

| 40% | 300.49 | 337.36 | 152.238 | 1.0181 | 0.7287 | 1.397197 | |

| 50% | 299.39 | 337.99 | 155.325 | 1.0226 | 0.7323 | 1.396351 | |

| 125 | 0% | 309.16 | 353.96 | 162.758 | 1.0050 | 0.7180 | 1.399721 |

| 6% | 311.07 | 355.22 | 161.325 | 1.0070 | 0.7197 | 1.399323 | |

| 10% | 312.07 | 356.33 | 161.325 | 1.0087 | 0.7210 | 1.399007 | |

| 15% | 311.30 | 354.74 | 160.235 | 1.0102 | 0.7222 | 1.398718 | |

| 20% | 312.81 | 356.50 | 160.325 | 1.0116 | 0.7234 | 1.398439 | |

| 25% | 313.28 | 357.00 | 160.325 | 1.0134 | 0.7248 | 1.398098 | |

| 30% | 312.37 | 355.94 | 160.325 | 1.0155 | 0.7266 | 1.397692 | |

| 40% | 313.36 | 357.00 | 160.325 | 1.0193 | 0.7296 | 1.396971 | |

| 50% | 313.09 | 356.65 | 160.325 | 1.0228 | 0.7378 | 1.396307 | |

| 60% | 313.34 | 358.49 | 162.992 | 1.0293 | 0.7378 | 1.395095 |

| Pgen (kW) | 6% | 10% | 15% | 20% | 25% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 66.26% | 62.61% | 58.48% | 57.75% | 57.05% | n/a |

| 50 | n/a | n/a | 51.18% | 50.20% | 45.73% | 43.79% | 40.14% | 41.19% | n/a |

| 75 | n/a | 45.93% | 38.27% | 31.19% | 28.14% | 27.80% | 26.02% | 24.87% | n/a |

| 100 | n/a | 31.37% | 22.90% | 20.19% | 17.26% | 16.02% | 14.80% | 14.99% | n/a |

| 125 | 37.40% | 24.75% | 20.92% | 17.88% | 15.93% | 14.18% | 12.23% | 11.71% | 11.54% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mallouppas, G.; Kumar, A.; Loizou, P.; Petrakides, S. Emissions Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Marine Genset Combusting Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122389

Mallouppas G, Kumar A, Loizou P, Petrakides S. Emissions Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Marine Genset Combusting Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122389

Chicago/Turabian StyleMallouppas, George, Ashok Kumar, Pavlos Loizou, and Sotiris Petrakides. 2025. "Emissions Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Marine Genset Combusting Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122389

APA StyleMallouppas, G., Kumar, A., Loizou, P., & Petrakides, S. (2025). Emissions Performance Assessment of a Retrofitted Marine Genset Combusting Biomethane in Dual-Fuel Mode. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2389. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122389