Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family and Construction and Screening of High-EPA Transgenic Strains in Phaeodactylum tricornutum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Algal Strain Cultivation

2.2.2. Identification of the FAD Gene Family in P. tricornutum

2.2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family in P. tricornutum

2.2.4. Construction of Ptd5α Gene Overexpression Vector

2.2.5. Growth Curves and Biomass Measurement

2.2.6. Extraction and Determination of Fatty Acids

2.2.7. Quantitative Fluorescent Detection of Ptd5α Gene Expression Levels

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Members of the Desaturase Gene Family in P. tricornutum

3.2. Sequence Characteristic Analysis of Gene Family Members

3.3. Motif Analysis of the FAD Family

3.4. Structural Analysis and Chromosomal Localization of the PtFAD Gene Family

- Acyl-CoA desaturase, primarily localized on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in animals and fungi, is a membrane-bound fatty acid desaturase. Its function is to catalyze the formation of double bonds in fatty acids bound to coenzyme A. For example, Δ9 Acyl-CoA desaturase belongs to this category [30].

- Acyl-ACP desaturase is primarily localized in the plant plastid matrix and belongs to the soluble fatty acid desaturase family. Its function is to catalyze the formation of double bonds in fatty acid substrates bound to acyl carrier protein (ACP) [31]. In P. tricornutum, genes such as Pt44622, Pt55137, and Pt9316 are classified within this category.

- Acyl-Lipid desaturase, primarily found in higher plants and cyanobacteria, functions to catalyze the formation of double bonds in fatty acids present in membrane-bound lipid complexes. Examples include desaturases such as Ptd12 and Ptd15, which belong to the membrane-bound FAD family and are difficult to isolate and purify [32].

- Members of the FAD gene family can act on both Acyl-CoA, and Acyl-Lipid substrates, hence their classification into the Acyl-CoA/Acyl-Lipid subfamily. For example, Ptd5α and Ptd5b, as well as Ptd6 and Pt22510, exhibit high sequence homology, indicating their evolutionary conservation. Based on phylogenetic relationships, members of the PtFAD gene family in P. tricornutum primarily belong to the Acyl-CoA/Acyl-Lipid and Acyl-Lipid subfamilies [33].

3.5. Analysis of the Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Ptd5α Protein

3.6. Construction of Ptd5α Gene Overexpression Vector and Acquisition of Overexpression Algal Strains

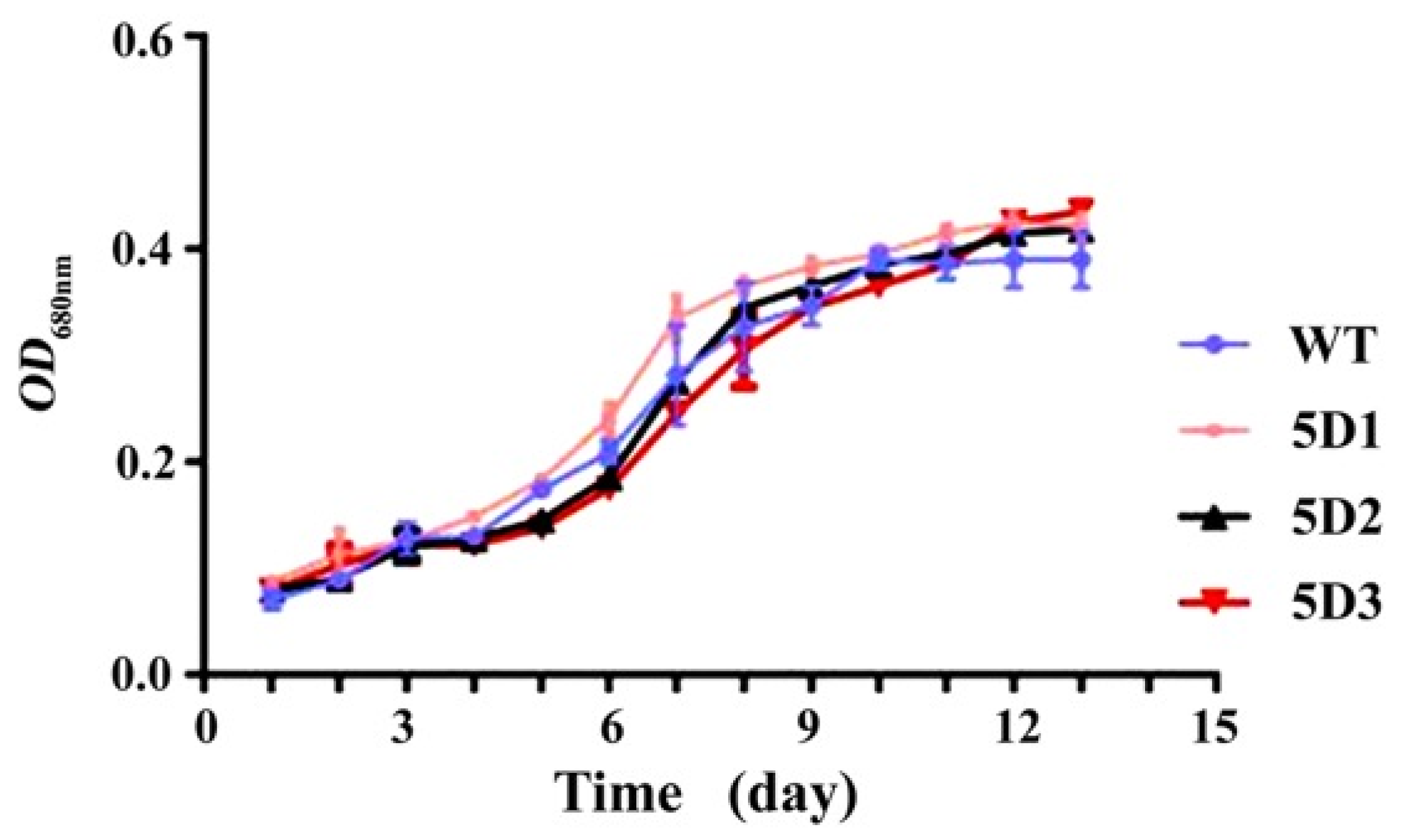

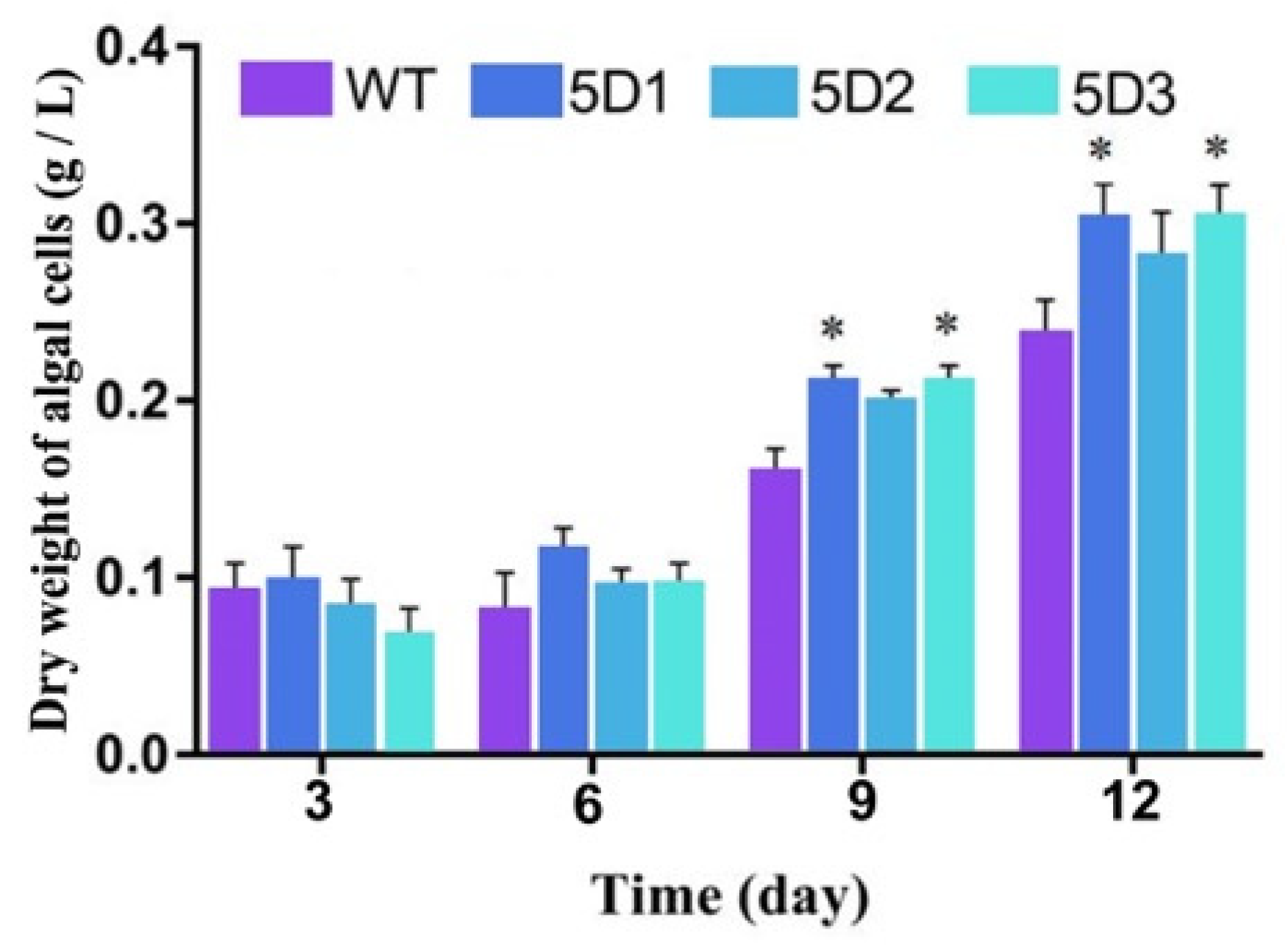

3.7. Determination of the Growth Curve of P. tricornutum

3.8. Determination of Fatty Acid Content in P. tricornutum

3.9. Fluorescence Quantitative Detection of Ptd5α Gene Expression

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowler, C.; Allen, A.E.; Badger, J.H.; Grimwood, J.; Jabbari, K.; Kuo, A.; Maheswari, U.; Martens, C.; Maumus, F.; Otillar, R.P.; et al. The Phaeodactylum genome reveals the evolutionary history of diatom genomes. Nature 2008, 456, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Xing, H.; Zhong, Y.S.; Song, D.H.; Xu, Y.C. Comparison of Nutrient Contents between Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Chlorella vulgaris. J. Tianjin Univ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 2, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Olguín, E.J.; SánchezGalván, G.; AriasOlguín, I.; Melo, F.J.; GonzálezPortela, R.E.; Cruz, L.; De Philippis, R.; Adessi, A. Microalgae-Based Biorefineries: Challenges and Future Trends to Produce Carbohydrate Enriched Biomass, High-Added Value Products and Bioactive Compounds. Biology 2022, 11, 1146. [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki, K.; Takamiya, K.; Nishimura, M. Studies on Electron Transfer Systems in the Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Biochem. 2008, 83, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.N.; Yang, M.; Zhou, Y.H.; Chen, X.Q.; Huang, B.Y. Effect of RNA Demethylase FTO Overexpression on Biomass and Bioactive Substances in Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Biology 2025, 14, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Liang, L.; Liu, K.; Xie, L.J.; Huang, L.Q.; He, W.J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Xue, T. Spent yeast as an efficient medium supplement for fucoxanthin and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) production by Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhu, L.Y.; Wang, B.Y.; Liu, Z.Y. Effect of Temperature and Salinity on Feeding and Metabolism of Two Marine copepods. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 2020, 51, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ayed, R.; Chirmade, T.; Hanana, M.; Khamassi, K.; Ercisli, S.; Choudhary, R.; Kadoo, N.; Karunakaran, R. Comparative Analysis and Structural Modeling of Elaeis oleifera FAD2, a Fatty Acid Desaturase Involved in Unsaturated Fatty Acid Composition of American Oil Palm. Biology 2022, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.X.; Zhang, Z.H. Identification and analysis of the FAD gene family in walnuts (Juglans regia L.) based on transcriptome data. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Nian, H.J. Characteristics of Δ12-fatty Acid Desaturase FAD2 and Its Functions Under Stress. Life Sci. Res. 2013, 17, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, H.; Movahedi, A.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Aghaei-Dargiri, S.; Ghaderi Zefrehei, M.; Zhu, S.; Yu, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of Fatty acid Desaturase Gene Family in Poplar. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.F.; Xiao, L.; Wu, Y.H.; Wu, G.; Lu, C.M. Research Progress on Plant Fatty Acid Desaturase and Its Encoding Genes. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2007, 24, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.T.; Fu, C.H.; Li, M.T.; Yu, L.J. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Δ6 Fatty Acid Elongase Gene from Phaeodactylm tricomutum. Biotechnol. Bull. 2009, 10, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K.T.; Zheng, C.N.; Xue, J.; Chen, X.Y.; Yang, W.D.; Liu, J.S.; Bai, W.B.; Li, H.Y. Delta 5 fatty acid desaturase upregulates the synthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 35, 8773–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.M.; Ma, X.L.; Zhu, B.H.; Li, S.; Yu, W.G.; Yang, G.P.; Pan, K.H. Expression ression of Δ5 fatty acid desaturase encoding gene of Phaeodactylum tricornutum in prokaryotic system. Trans. Oceanol. Limnol. 2012, 1, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dolch, L.J.; Maréchal, E. Inventory of Fatty Acid Desaturases in the Pennate Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 5732–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M.L.; Powers, S.; Napier, J.A.; Sayanova, O. Heterotrophic Production of Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids by Trophically Converted Marine Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domergue, F.; Spiekermann, P.; Lerchl, J.; Beckmann, C.; Kilian, O.; Kroth, P.G.; Boland, W.; Zähringer, U.; Heinz, E. New Insight into Phaeodactylum tricornutum Fatty Acid Metabolism. Cloning and Functional Characterization of Plastidial and Microsomal Δ12-Fatty Acid Desaturases. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 1648–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viso, A.-C.; Marty, J.C. Fatty acids from 28 marine microalgae. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Thomas-Hall, S.R.; Chua, E.T.; Schenk, P.M. Development of High-Level Omega-3 Eicosapentaenoic Acid (EPA) Production from Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Phycol. 2020, 57, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Kavanagh, J.M.; McClure, D. A scalable model for EPA and fatty acid production by Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1011570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, J.R.; Shrestha, P.; Zhou, X.R.; Mansour, M.P.; Liu, Q.; Belide, S.; Nichols, P.D.; Singh, S.P. Metabolic Engineering Plant Seeds with Fish Oil-Like Levels of DHA. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Said, I.H.; Thorstenson, C.; Thomsen, C.; Ullrich, M.S.; Kuhnert, N.; Thomsen, L. Pilot-scale production of antibacterial substances by the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum Bohlin. Algal Res. 2018, 32, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remmers, I.M.; Martens, D.E.; Wijffels, R.H.; Lamers, P.P. Dynamics of triacylglycerol and EPA production in Phaeodactylum tricornutum under nitrogen starvation at different light intensities. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.T.; Xiong, B.H.; Cheng, G.; Zhong, Y.H.; Yu, L. A novel non-genetic strategy to increase lipid content in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesionowska, M.; Ovadia, J.; Hockemeyer, K.; Clews, A.C.; Xu, Y. EPA and DHA in microalgae: Health benefits, biosynthesis, and metabolic engineering advances. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2023, 100, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.L.; Guo, B.; Wan, X.; Gong, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.B.; Hu, C.J. Isolation and Characterization of the Diatom Phaeodactylum Δ5-Elongase Gene for Transgenic LC-PUFA Production in Pichia pastoris. Mar. Drugs 2014, 12, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, R.P.; Hamilton, M.L.; Economou, C.K.; Smith, R.; Hassall, K.L.; Napier, J.A.; Sayanova, O. Overexpression of an endogenous type 2 diacylglycerol acyltransferase in the marine diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum enhances lipid production and omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid content. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şirin, P.A.; Serdar, S. Effects of nitrogen starvation on growth and biochemical composition of some microalgae species. Folia Microbiol. 2024, 69, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Quan, W.; Wang, D.; Cui, J.; Wang, T.; Lin, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of Fatty Acid Desaturase (FAD) Genes in Camelina sativa (L.) Crantz. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Sun, Y.; Hang, W.; Wang, X.; Xue, J.; Ma, R.; Jia, X.; Li, R. Characterization of a Novel Acyl-ACP Δ9 Desaturase Gene Responsible for Palmitoleic Acid Accumulation in a Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 584589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starikov, A.Y.; Sidorov, R.A.; Kazakov, G.V.; Leusenko, P.A.; Los, D.A. The substrate preferences and “counting” mode of the cyanobacterial ω3 (Δ15) acyl-lipid desaturase. Biochimie 2025, 232, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starikov, A.Y.; Sidorov, R.A.; Los, D.A. Counting modes of acyl-lipid desaturases. Funct. Plant Biol. 2025, 52, 24338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lu, G.; Yang, G.; Bi, Y. Improving oxidative stability of biodiesel by cis-trans isomerization of carbon-carbon double bonds in unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters. Fuel 2019, 242, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, L.; Pazos, M.; Gallardo, J.M.; Torres, J.L.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Nogués, R.; Romeu, M.; Medina, I. Reduced protein oxidation in Wistar rats supplemented with marine ω3 PUFAs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 55, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Ren, X.L.; Fu, Y.Q.; Gao, J.L.; Li, D. Ratio of n-3/n-6 PUFAs and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of 274,135 adult females from 11 independent prospective studies. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A. Fish as Source of n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs), Which One is Better-Farmed or Wild? Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 455–466. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, H.; Kajiwara, S. A Stearoyl-CoA-specific Δ9 Fatty Acid Desaturase from the Basidiomycete Lentinula edodes. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2003, 67, 2431–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makay, K.; Griehl, C.; Grewe, C. Downstream Process Development for Multiproduct Recovery of High-Value Lead Compounds from Marine Microalgae. Chem. Ing. Tech. Verfahrenstech. Tech. Chem. Apparatewesen Biotechnol. 2022, 94, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónasdóttir, A.H. Fatty Acid Profiles and Production in Marine Phytoplankton. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltomaa, E.; Johnson, M.; Taipale, S. Marine Cryptophytes Are Great Sources of EPA and DHA. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.Y.; Lu, Y.D.; Wang, M.Q.; Bian, S.G.; Yang, Q.L.; Qin, S. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of the Δ12 Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene in Chlorella. Mar. Sci. 2009, 33, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gai, W.Y.; Sun, H.; Hu, Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Gai, S.P.; Yuan, Y.C. Genome-Wide Identification of Membrane-Bound Fatty Acid Desaturase Genes in Three Peanut Species and Their Expression in Arachis hypogaea during Drought Stress. Genes 2022, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiahmadi, Z.; Abedi, A.; Wei, H.; Sun, W.B.; Ruan, H.H.; Zhuge, Q.; Movahedi, A. Identification, evolution, expression, and docking studies of fatty acid desaturase genes in wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.L.; An, J.B.; Qi, D.S.; Qiao, F.; Jiang, D.; Du, S.B.; Ji, S.; Xie, H.C. Identification and Expression Pattern Analysis of FAD Gene Family in Populus tomentose. Mol. Plant Breed. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.X.; Chen, H.Q.; Gu, Z.N.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.Q. ω3 fatty acid desaturases from microorganisms: Structure, function, evolution, and biotechnological use. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 10255–10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Z.; Xu, J.; Liao, K.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Yan, X. Biosynthesis of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Razor Clam Sinonovacula constricta: Characterization of Δ5 and Δ6 Fatty Acid Desaturases. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 4592–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Sun, Q.X.; Li, X.Z.; Qi, B.X. Functional Characterization of Isochrysis galbana Δ5 Desaturase Gene IgD5 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Agron. Sin. 2013, 39, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohne, F.; Linden, H. Regulation of carotenoid biosynthesis genes in response to light in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Struct. Expr. 2002, 1579, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Pan, K.H.; Wang, X.Q.; Chen, F.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, B.H.; Qing, R.W. Hierarchical recognition on the taxonomy of Nitzschia closterium f. minutissima. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2008, 53, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierli, D.; Barone, M.E.; Graceffa, V.; Touzet, N. Cold stress combined with salt or abscisic acid supplementation enhances lipogenesis and carotenogenesis in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 45, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.J.; Yuan, C.J.; Li, T.; Li, A.F. Growth, biochemical composition, and photosynthetic performance of Scenedesmus acuminatus during nitrogen starvation and resupply. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Bäuerl, C.; Cortés-Macías, E.; Calvo-Lerma, J.; Collado, M.C.; Barba, F.J. The impact of liquid-pressurized extracts of Spirulina, Chlorella and Phaedactylum tricornutum on in vitro antioxidant, antiinflammatory and bacterial growth effects and gut microbiota modulation. Food Chem. 2023, 401, 134083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Thomas-Hall, S.R.; Chua, E.T.; Schenk, P.M. Development of a Phaeodactylum tricornutum biorefinery to sustainably produce omega-3 fatty acids and protein. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 300, 126839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco-Vieir, M.; Costa, D.M.B.; Mata, T.M.; Martins, A.A.; Freitas, M.A.V.; Caetano, N.S. Environmental assessment of industrial production of microalgal biodiesel in central-south Chile. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conserved Domain | ProteinID | Gene Name | Chromosome | Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAD desaturase (PF00487) | XP_002186139.1 | PtFAD2 | Chr3 | Δ12 fatty acid desaturase |

| XP_002178636.1 | Pt44622 | Chr4 | predicted protein | |

| XP_002180514.1 | Pt46275 | Chr9 | predicted protein | |

| XP_002180771.1 | Pt46383 | Chr10 | predicted protein | |

| XP_002185732.1 | Ptd5α | Chr11 | Δ5 fatty acid desaturase | |

| XP_002181794.1 | Ptd9 | Chr13 | Δ9 desaturase | |

| XP_002182901.1 | Ptd6 | Chr17 | Δ6 fatty acid desaturase | |

| XP_002182832.1 | Ptd12 | Chr17 | precursor of desaturase ω-6 desaturase | |

| XP_002182858.1 | Ptd5b | Chr17 | Δ5b fatty acid desaturase | |

| XP_002183026.1 | Pt22510 | Chr18 | predicted protein | |

| XP_002183420.1 | Pt22677 | Chr19 | dihydroceramide Δ4 desaturase | |

| XP_002184864.1 | Pt55137 | Chr26 | acyl desaturase | |

| XP_002185374.1 | Pt50443 | Chr30 | predicted protein | |

| XP_002185498.1 | Ptd15 | Chr31 | precursor of desaturase ω-3 desaturase | |

| FA desatrase.2 (PF03405) | XP_002177417.1 | Pt9316 | Chr1 | predicted protein |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, W.; Chen, Q.; Ye, H.; Gao, P.; Wu, B.; Meng, W.; Zheng, W.; Shi, J.; Murong, H. Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family and Construction and Screening of High-EPA Transgenic Strains in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122369

He W, Chen Q, Ye H, Gao P, Wu B, Meng W, Zheng W, Shi J, Murong H. Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family and Construction and Screening of High-EPA Transgenic Strains in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122369

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Wenjin, Qingying Chen, Haoying Ye, Pingru Gao, Bina Wu, Wenchu Meng, Wenhui Zheng, Jianhua Shi, and Haien Murong. 2025. "Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family and Construction and Screening of High-EPA Transgenic Strains in Phaeodactylum tricornutum" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122369

APA StyleHe, W., Chen, Q., Ye, H., Gao, P., Wu, B., Meng, W., Zheng, W., Shi, J., & Murong, H. (2025). Analysis of the Fatty Acid Desaturase Gene Family and Construction and Screening of High-EPA Transgenic Strains in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2369. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122369