Effects of Anchor Chain Arrangements on the Motion Response of Three-Anchor Buoy Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Methodology

2.1. Wind Load

2.2. Wave Load

2.2.1. Three-Dimensional Potential Flow Theory

2.2.2. Morison Formula

2.3. Current Load

2.4. Dynamic Response Analysis Theory of Mooring System

2.4.1. Frequency Domain Analysis Theory

2.4.2. Time Domain Analysis Theory

3. Numerical Simulation Model

3.1. Buoy Geometric Parameters

3.2. Geometric Parameters

3.3. Anchor Chain Arrangement

4. Frequency Domain Analysis

4.1. Hydrodynamic Analysis of the Buoy

4.1.1. Added Mass

4.1.2. Radiation Damping

4.1.3. Motion Response Amplitude Operator (RAO)

- The RAO curves exhibit analogous trends in both surge and yaw motions. Under surge conditions, the RAO amplitude approaches zero at a wave incident angle of 90°; however, the RAO demonstrates a proportional relationship with increasing wave period at non-orthogonal wave directions. For fixed wave periods, the RAO exhibits an inverse correlation with wave incident angle. During yaw motion, minimal RAO amplitudes occur at 0° wave incidence, and the RAO demonstrates a proportional relationship with increasing wave period while non-orthogonal wave angles. Notably, under constant wave periodicity, the yaw RAO displays a direct proportionality to the wave incidence angle magnitude.

- The heave motion displays angular independence, with all RAO curves following identical growth trajectories. The response increases monotonically with wave period before asymptotically approaching a 1 m/m amplitude ratio.

- The roll RAO curves exhibited consistent variation patterns across different wave incident angles as a function of wave period. Initially, all curves demonstrated an ascending trend with increasing wave period, reaching peak magnitudes at approximately 3 s, followed by a gradual decline until asymptotic convergence toward zero. Notably, under equivalent wave period conditions, the roll RAO magnitude showed proportional enhancement with increasing wave incident angle. As illustrated in Figure 8c, the maximum roll RAO peak value of 24.65°/m was recorded at a 90° wave incidence. This critical value, indicative of potential buoy capsizing, deviates from practical operational conditions, thereby necessitating implementation of damping correction measures to ensure system stability.

4.2. Frequency Domain Analysis of the Three-Anchor Buoy System

4.2.1. Environmental Conditions

4.2.2. Maximum Offset of Buoy System

4.2.3. Calculation of Wind/Current Force Coefficient Matrix

- We calculated the area and centroid coordinates of each part of the windward area;

- The centroid coordinates of the whole windward area are obtained by weighted average after multiplying the wind coefficient of each part of the above area and combining the centroid coordinates;

- According to Formulas (18) and (19), the wind coefficients of the X and Y directions at any angle are obtained;

- Because the wind load is acting on the centroid of the wind area, and the centroid and the center of gravity do not coincide, it will also produce the relevant torque and ;

- Because, in the Z direction, the center of gravity and the centroid overlap, there is no or along the positive direction of the wind when the wind coefficient is solved;

- The whole wind coefficient matrix can be obtained by calculating the wind coefficient at other angles.

4.2.4. Results and Discussions

- The motions of the buoy system with five anchor chain arrangements in the sway, roll, and yaw directions all show a symmetry of about 90°, and all increase from 0 to the minimum. In the sway direction, the amplitude of configuration 1 is the largest and reaches 46.715°, which will obviously lead to capsizing. The motion amplitude of the buoy system of configuration 5 is the smallest. In the roll direction, the motion amplitude of each medium configuration is small. On the whole, configuration 1 is the smallest and configuration 3 is the largest. In the yaw direction, except for configuration 1, the motion amplitude of the buoy shows fluctuating changes.

- The response amplitudes in surge, heave, and pitch for each configuration exhibit a close alignment with the variation curve of the load angle. But with the increase in the load angle, the motion amplitude of configuration 5 in the surge and pitch decrease, while for the heave, it increases. Moreover, the maximum value of configuration 5 in the surge reaches 24.756 m, which exceeds our set value, so configuration 5 also has shortcomings. In the heave and pitch directions, the motion amplitude of configuration 4 is basically smaller than that of other configurations, and the motion response of configuration 4 also shows a symmetry of about 90° in the pitch but not in the heave.

- Through the above analysis, the variation curve and the maximum value of the motion amplitude with the change in wave angle of each configuration can be obtained. Through comparison, it can be found that configuration 1 and configuration 5 have the maximum offset values, exceeding the set value in the roll and pitch, respectively, so they have obvious defects. Except for in roll, the motion response of configuration 4 is basically smaller than that of configuration 2 and configuration 3, so configuration 4 is the optimal design as a whole.

5. Time Domain Analysis of Three-Anchor Buoy System

- For anchor chain 1#, the maximum tension in all configurations exhibited a positive correlation with the load combination angle, while the minimum submarine anchor chain length demonstrated an inverse relationship. Under identical load angles, configurations 1 to 5 sequentially displayed decreasing tension magnitudes and correspondingly increasing minimum submarine anchor chain lengths.

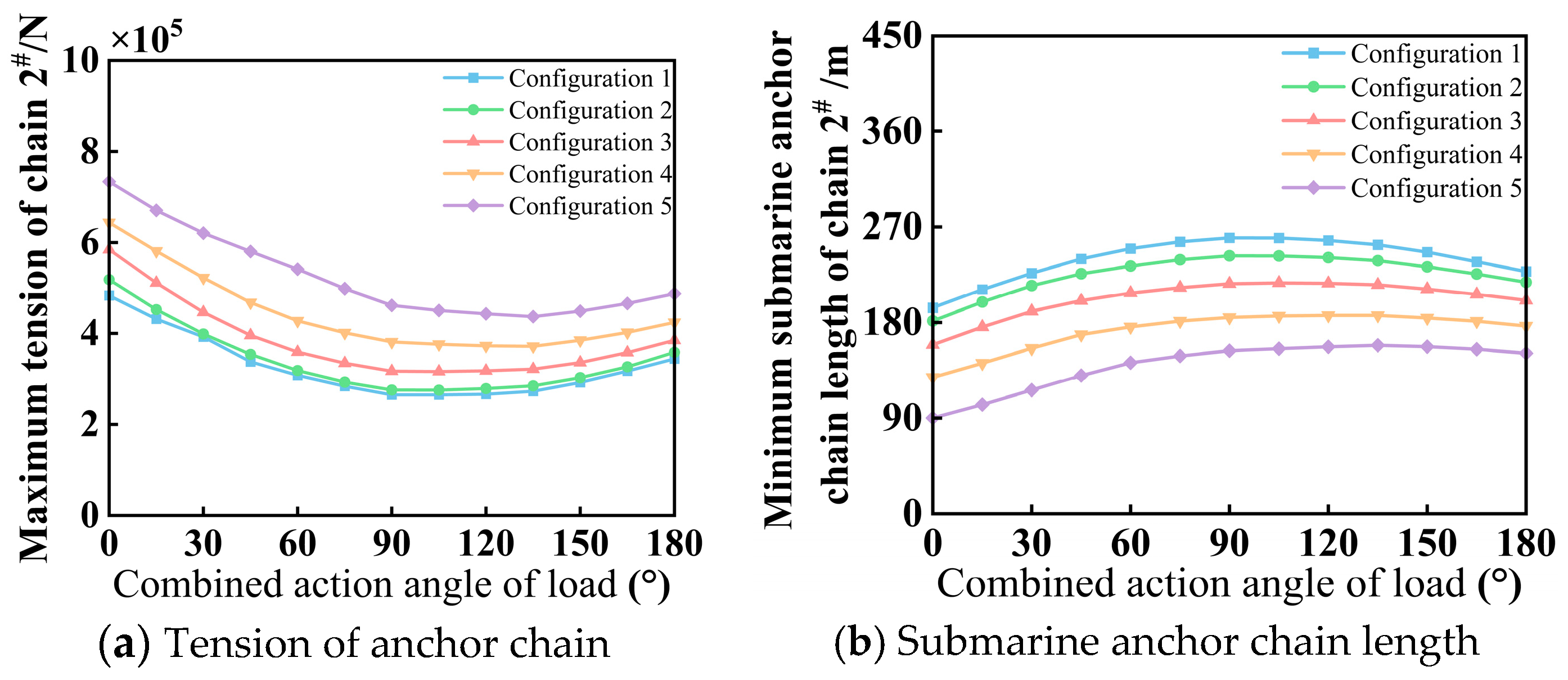

- For anchor chain 2#, the maximum tension in anchor chains in all configurations demonstrated a non-monotonic response to increasing load angles, exhibiting an initial decrease followed by a subsequent increase. The minimum submarine anchor chain length displayed the following behavior: initially increasing then decreasing with angular progression. Comparative analysis revealed that, at equivalent load angles, configurations 1 through 5 exhibited sequential reductions in the minimum submarine anchor chain length and increases in chain tension.

- For anchor chain 3#: As the load angle increased, the maximum tension of the anchor chain in each configuration increased and then decreased, while the minimum submarine anchor chain length decreased and then increased; when the load angle was the same, the tension in configuration 1 to configuration 5 increased in turn, while the minimum submarine anchor chain length decreased in turn.

- The variation curves of buoy motion amplitude with load angle obtained by frequency domain analysis and time domain analysis are basically the same in each degree of freedom.

- The numerical values of frequency domain analysis are basically larger than those of time domain analysis to a certain extent, and some of the analysis values are far beyond the maximum value of motion set by us. This is because frequency domain analysis does not consider the coupling effect, and the calculation results can only be used as a preliminary analysis.

- It can be seen that frequency domain analysis can quickly determine the response of the motion response of the buoy system with the change in the load angle. However, because the coupling effect is not considered in the calculations, time domain analysis should be carried out in order to reflect the motion response of the buoy system more comprehensively.

- Under the designed sea conditions, the maximum 6-DOF time domain responses of the buoy system with five anchor chain arrangements were analyzed. In the surge, configuration 4 exhibited the minimum response amplitude of 5.551 m when subjected to a combined action angle of 0°. Configuration 5 had the largest response amplitude, which was 20.277 m when the combined load action angle was 0°. In the sway, configuration 5 had the smallest response amplitude, which was 3.301 m when the combined load action angle was 90°; configuration 1 had the largest response amplitude, which was 34.803 m when the combined loading angle was 90°. In the heave, configuration 4 had the smallest response amplitude, which was 1.197 m when the combined load action angle was 15°; configuration 1 had the largest response amplitude, which was 1.294 m when the combined load action angle was 75°. In the roll, configuration 5 had the smallest response amplitude, which was 3.191° when the combined action angle of load was 90°; configuration 1 had the largest response amplitude, which was 18.601° when the combined load action angle was 90°. In the pitch, configuration 4 had the smallest response amplitude, which was 5.024° when the combined load action angle was 0°; configuration 5 had the largest response amplitude, which was 11.847° when the combined load action angle was 0°. In the yaw, configuration 4 had the smallest response amplitude, which was 0.231° when the combined action angle of load was 90°; configuration 1 had the largest response amplitude, which was 1.172° when the combined load action angle was 75°.

- In the time domain analysis of cable tension responses, configuration 1 exhibited the maximum tension value of 952.23 kN, occurring at anchor chain 1# under a combined load angle of 180°, with a corresponding safety factor of 1.33. Configuration 4 demonstrated the minimum tension response of 778.72 kN under identical load conditions, achieving a safety factor of 1.63. Notably, while all five configurations failed to meet the specified safety factor requirement (>1.67) for anchor chain tension standards, configuration 4 showed the closest compliance with this criterion, suggesting better alignment with design specifications. Ways to the improve safety factor include an increase in anchor chain length or anchor chain diameter or higher-strength types of anchor chains.

- For the time domain analysis of horizontal chain length responses, configuration 4 exhibited the maximum displacement of 103.93 m at anchor chain 1# under the combined loading angle of 180°, whereas configuration 1 demonstrated the minimum response amplitude of 45.30 m at the same chain location under identical angular loading conditions.

6. Conclusions

- The hydrodynamic analysis revealed distinct trends in the 6-DOF responses of the buoy under varying wave periods. For surge, sway, heave, roll, and pitch, both added mass and radiation damping led to a trend characterized by an initial increase, followed by a decrease and subsequent stabilization as wave period increased. The yaw demonstrated an initial decrease and then stabilization with increasing wave period. Under constant wave incidence angles, the RAO displayed period-dependent characteristics: the RAO of pitch and roll showed progressive enhancement with increasing wave period; the RAO of heave initially increased before stabilizing at higher periods; and roll response exhibited a unique pattern of initial amplification followed by reduction. Under constant wave periods: the RAO of pitch decreased with increasing wave incidence angle; the RAO of heave remained essentially constant regardless of incidence angle variations; roll and yaw responses demonstrated positive correlation with wave incidence angles. Notably, the addition of additional viscous damping demonstrated significant effects on the RAO value of roll response mitigation.

- With an increase in the angle of the combined action of loads, the maximum tension of anchor chain 1# increased and the minimum submarine anchor chain length decreased; the maximum tension of anchor chain 2# firstly decreased and then increased and the minimum submarine anchor chain length firstly increased and then decreased; the maximum tension of anchor chain 3# firstly increased and then decreased, and the minimum submarine anchor chain length firstly decreased and then increased.

- Compared with the other four anchor chain arrangement configurations, the response amplitude of the three-anchor buoy system with a uniform distribution of three anchors at 120° was basically the minimum value for six degrees of freedom, and the maximum tension of the anchor chain and the minimum submarine anchor chain length were also at a relatively optimal state. Therefore, the design with a uniform distribution of three anchor chains can effectively limit the movement of the buoy and better adapt to a marine environment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barge, L.M.; Price, R.E. Diverse geochemical conditions for prebiotic chemistry in shallow-sea alkaline hydrothermal vents. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Liu, S.X.; Li, Y.Z. Current situation and trend of marine data buoy and monitoring network technology of China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2016, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, H.R.; Ertekin, R.C.; Mills, T.R.J. Wave-induced response of a 5-module mobile offshore base. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–9 July 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bayati, I.; Gueydon, S.; Belloli, M. Study of the effect of water depth on potential flow solution of the OC4 semisubmersible floating offshore wind turbine. Energy Procedia 2015, 80, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaechi, C.V.; Wang, F.; Hou, X.; Ye, J. Strength of submarine hoses in Chinese-lantern configuration from hydrodynamic loads on CALM buoy. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Robertson, A.; Jonkman, J.; Yu, Y.-H.; Koop, A.; Nadal, A.B.; Li, H.; Bachynski Polić, E.; Pinguete, R.; Shi, W.; et al. OC6 Phase Ib: Validation of the CFD predictions of difference-frequency wave excitation on a FOWT semisubmersible. Ocean Eng. 2021, 241, 110026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe-Føre, H.; Christian Endresen, P.; Gunnar Aarsæther, K.; Jensen, J.; Føre, M.; Kristiansen, D.; Fredheim, A.; Lader, P.; Reite, K.J. Structural analysis of aquaculture nets: Comparison and validation of different numerical modeling approaches. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2015, 137, 041201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Decew, J.; Tsukrov, I.; Bai, X.; Bi, C. Comparative study of two approaches to model the offshore fish cages. China Ocean Eng. 2015, 29, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Jahangiri, V. Bi-directional vibration control of offshore wind turbines using a 3D pendulum tuned mass damper. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2018, 105, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuco, B.; Amador, S.D.; Katsanos, E.I.; Tygesen, U.T.; Christensen, E.D.; Brincker, R. Comparing measured responses of an offshore structure with operational modal analysis-assisted classical model approach. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2021, 143, 031702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.M.; Ma, M.; Chu, Y.; Jeng, D.; Zhang, H. Developments in modeling techniques for reliability design of aquaculture cages: A review. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.W. A Reliability Based Design Methodology for Extreme Responses of Offshore Wind Turbines. Doctorial Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 1 October 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kreuzer, E.; Wike, U. Mooring systems-A multibody dynamic approach. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2002, 8, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; You, J.; Glomnes, E.B. Stochastic linearization and its application in motion analysis of cylindrical floating structure with bilge boxes. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Busan, Republic of Korea, 19–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Xiang, X.; Liu, J. Numerical investigation of wave-frequency pontoon responses of a floating bridge based on model test results. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 9–14 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Arreba, I.; Bruinsma, N.; Bachynski, E.E.; Viré, A.; Paulsen, B.T.; Jacobsen, N.G. Modeling of a semisubmersible floating wind platform in severe waves. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Madrid, Spain, 17–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, J.; Eskilsson, C. Mooring systems with submerged buoys: Influence of buoy geometry and modeling fidelity. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 102, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Robertson, A.; Jonkman, J.; Yu, Y. Uncertainty assessment of CFD investigation of the nonlinear difference-frequency wave loads on a semisubmersible FOWT platform. Sustainability 2021, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Peyrard, C.; Pan, G. Assessing focused wave applicability on a coupled aero- hydro-mooring FOWT system using CFD approach. Ocean Eng. 2021, 240, 109987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzon, I.; Nava, V.; Gao, Z.; Petuya, V. Frequency domain modelling of a coupled system of floating structure and mooring Lines: An application to a wave energy converter. Ocean Eng. 2021, 220, 108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brommundt, M.; Krause, L.; Merz, K.; Muskulus, M. Mooring system optimization for floating wind turbines using frequency domain analysis. Energy Procedia 2012, 24, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, M.; Muskulus, M. Coupled mooring systems for floating wind farms. Energy Proc. 2015, 80, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, H.; Dardel, M. Parametric study of catenary mooring system on the dynamic response of the semi-submersible platform. Ocean Eng. 2018, 153, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzon, I.; Nava, V.; de Miguel, B.; Petuya, V. A comparison of numerical approaches for the design of mooring systems for wave energy converters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masciola, M.; Jonkman, J.; Robertson, A. Implementation of a multisegmented, quasi-static cable model. In Proceedings of the International Ocean (Offshore) and Polar Engineering Conference, Anchorage, AK, USA, 30 June–5 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.W.; Sung, H.G.; Hong, S.Y. Coupled Versus Decoupled Analysis for Floating Body and Mooring Lines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hermawan, Y.A.; Furukawa, Y. Coupled three-dimensional dynamics model of multi-component mooring line for motion analysis of floating offshore structure. Ocean Eng. 2020, 200, 106928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Roh, M.I.; Ham, S.H.; Ku, N.K. Coupled analysis method of a mooring system and a floating crane based on flexible multibody dynamics considering contact with the seabed. Ocean Eng. 2018, 163, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liang, M.; Wang, X.; Ding, A. A mooring system deployment design methodology for vessels at varying water depths. China Ocean Eng. 2020, 34, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.T.; Bruen, F.J. Mooring line dynamics: Comparison of time domain, frequency domain, quasi-static analyses. In Proceedings of the 23rd Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 6–9 May 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, D.L. Coupled analysis of floating production systems. Ocean. Eng. 2005, 32, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cunff, C.; Ryu, S.; Heurtier, J.; Duggal, A.S. Frequency-domain calculations of moored vessel motion including low frequency effect. In Proceedings of the ASME 2008 27th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Arctic Engineering, Estoril, Portugal, 15–20 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Low, Y.M.; Langley, R.S. Time and frequency domain coupled analysis of deepwater floating production systems. Appl. Ocean Res. 2006, 28, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.O.A.; Ja’e, I.A.; Hwa, M.G.Z. Effects of water depth, mooring line diameter and hydrodynamic coefficients on the behaviour of deepwater FPSOs. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 11, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijs, F.; de Bruijn, R.; Savenije, F. Concept design verification of a semi-submersible floating wind turbine using coupled simulations. Energy Procedia 2014, 53, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahri, D.; Ghassemi, H. Dynamic Response Analysis of a Floating Wind Turbine Tri-Floater Type with Heave-Plate and Mooring System. J. Subsea Offshore Sci. Eng. 2017, 9, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 19901-7:2013; Petroleum and Natural Gas Industries—Specific Requirements for Offshore Structures—Part 7: Stationkeeping Systems for Floating Offshore Structures and Mobile Offshore Units. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://cdn.standards.iteh.ai/samples/39068/73d7fb0e544c4f4c870856e8abb31666/ISO-19901-7-2005.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Aqwa User’s Manual. Available online: https://ansyshelp.ansys.com/public/Views/Secured/corp/v251/en/pdf/Aqwa_Users_Manual.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Classification of Mooring Systems for Permanent and Mobile Offshore Units. Available online: https://erules.veristar.com/dy/data/bv/pdf/493-NR_2021-07.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- American Petroleum Institute. Recommended Practice for Planning, Designing and Constructing Fixed Offshore Platforms-Working Stress Design, 21st ed.; API Publishing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaretto, O.M.; Menéndez, M.; Lobeto, H. A global evaluation of the JONSWAP spectra suitability on coastal areas. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 112756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Petroleum Institute. Design and Analysis of Stationkeeping Systems for Floating Structures, 3rd ed.; API Publishing Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass/t | 45.0 | Heave natural period/s | 3.26 |

| Displacement/m3 | 43.9 | Roll natural period/s | 2.76 |

| Draft/m | 0.862 | Transverse metacentric height/m | 8.20 |

| Base cylindrical height/m | 2.2 | Longitudinal metacentric height/m | 8.20 |

| Bottom round table high/m | 1.0 | Rolling inertia radius/m | 2.59 |

| Center of buoyancy/m | (0, 0, −0.378) | Pitching inertia radius/m | 2.59 |

| Center of gravity/m | (0, 0, 0.533) | Yawing inertia radius/m | 3.28 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Diameter/mm | 48.0 |

| Mass per unit length (in the air)/(kg/m) | 50.46 |

| Length/m | 600 |

| Breaking strength/kN | 1270 |

| Parameters | Mass /kg | Added Mass /kg | Stiffness /N·m−1 | Critical Damping /N·m·s·deg−1 | Viscous Damping /N·m·s·deg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heave | 45,000 | ||||

| Roll |

| Parameters | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | Value | Angle | Value | Angle | Value | Angle | Value | Angle | Value | |

| Surge/m | 180° | 8.212 | 180° | 7.707 | 180° | 6.612 | 0° | 5.551 | 0° | 20.277 |

| Sway/m | 90° | 34.803 | 90° | 16.547 | 90° | 8.659 | 90° | 4.971 | 90° | 3.301 |

| Heave/m | 75° | 1.294 | 60° | 1.243 | 165° | 1.225 | 15° | 1.197 | 75° | 1.261 |

| Roll/° | 90° | 18.601 | 90° | 12.379 | 90° | 7.322 | 90° | 4.389 | 90° | 3.191 |

| Pitch/° | 135° | 6.479 | 180° | 5.925 | 180° | 5.202 | 0° | 5.024 | 0° | 11.847 |

| Yaw/° | 75° | 1.172 | 90° | 0.638 | 150° | 0.331 | 90° | 0.231 | 60° | 0.459 |

| Parameters | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | 180° | 180° | 180° | 180° | 45° |

| Anchor chain | 1# | 1# | 1# | 1# | 3# |

| Maximum tension/kN | 952.23 | 927.55 | 878.03 | 778.72 | 838.81 |

| Safety factor | 1.33 | 1.37 | 1.45 | 1.63 | 1.51 |

| Parameters | Configuration 1 | Configuration 2 | Configuration 3 | Configuration 4 | Configuration 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | 180° | 180° | 180° | 180° | 180° |

| Anchor chain | 1# | 1# | 1# | 1# | 3# |

| Submarine anchor chain length/m | 45.30 | 52.96 | 70.31 | 103.93 | 78.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.; Mi, Z.; Zhang, L. Effects of Anchor Chain Arrangements on the Motion Response of Three-Anchor Buoy Systems. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122368

Li Z, Mi Z, Zhang L. Effects of Anchor Chain Arrangements on the Motion Response of Three-Anchor Buoy Systems. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122368

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zudi, Zhinan Mi, and Lunwei Zhang. 2025. "Effects of Anchor Chain Arrangements on the Motion Response of Three-Anchor Buoy Systems" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122368

APA StyleLi, Z., Mi, Z., & Zhang, L. (2025). Effects of Anchor Chain Arrangements on the Motion Response of Three-Anchor Buoy Systems. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122368