1. Introduction

With rapid population growth and accelerated urbanization, the increasing demand for construction land has led to a growing scarcity of available inland space, driving large-scale engineering activities to expand toward coastal and nearshore regions [

1]. These coastal zones are characterized by complex geological conditions and highly variable stratigraphic structures, which are significantly influenced by tidal dynamics, wave action, and sedimentary processes. Therefore, the precise investigation of shallow subsurface geological structures, mechanical properties, and sedimentary environments is a critical prerequisite for ensuring the safety, reliability, and feasibility of marine engineering design and construction [

2,

3,

4,

5]. A variety of methods are available for coastal engineering investigation [

6,

7,

8], including geological drilling [

9,

10], geophysical exploration [

11,

12], and in situ geotechnical testing [

13,

14,

15]. The application of traditional geological drilling techniques in shallow marine environments is severely constrained by high costs, complex operations, and strong environmental disturbances, which makes them unsuitable for efficient and detailed subsurface characterization. In contrast, geophysical exploration has become a key approach for investigating subsurface geological structures, sedimentary features, and engineering geological conditions in coastal and shallow marine areas. Owing to its non-destructive nature, continuity, and high resolution [

16], geophysical methods—such as seismic, microtremor, electrical, and geo-electrical tomography techniques—can integrate limited borehole data to perform constrained inversion of subsurface structures, thereby revealing stratigraphic boundaries, lithological variations, and the distribution of physical parameters [

17,

18,

19]. This provides essential support for marine engineering construction, coastal protection, and offshore resource development.

In recent years, with the continuous advancement of China’s coastal economic belt development and marine power strategy, coastal engineering projects have placed increasingly higher demands on high-resolution and high-precision geophysical exploration technologies [

20,

21,

22,

23]. Among these, surface wave–based geophysical methods—particularly microtremor surface wave exploration—have gained widespread application in urban foundation assessment, subway tunnel investigation, geothermal resource evaluation, and coastal engineering exploration. Microtremors refer to weak ground vibrations generated by non-seismic events, containing a mixture of body and surface waves, with surface wave energy typically accounting for more than 70% of the total signal energy. Owing to their non-destructive nature, high resolution, and strong sensitivity to shallow subsurface structures, these methods have become powerful tools for near-surface characterization. By integrating modern signal processing and high-performance computing, microtremor exploration has enabled multimodal dispersion analysis and high-precision S-wave velocity inversion, allowing effective identification of weak interlayers, reclaimed sediments, and variations in bedrock depth. Consequently, this technique provides new insights and approaches for evaluating foundation stability, site selection, and engineering design in coastal and coastal environments [

24,

25].

In conventional seismic exploration, Rayleigh surface waves were traditionally regarded as noise and thus suppressed. However, in the 1950s, researchers discovered that Rayleigh waves exhibit significant dispersion characteristics in layered media and can effectively reveal subsurface velocity structures, marking the beginning of their extensive application in geophysics and engineering geology [

26,

27]. During propagation, Rayleigh waves carry abundant information about subsurface stratigraphy—their phase velocity is closely related to the density, elastic modulus, and S-wave velocity of the medium—making them particularly valuable for characterizing shallow geological structures and engineering foundations. Surface wave exploration typically involves three key stages: theoretical dispersion computation, dispersion curve extraction, and S-wave velocity inversion. In terms of theoretical dispersion computation, significant advancements have been achieved—from Haskell’s transfer matrix method to Knopoff’s algebraic refinement [

28,

29], followed by Ling’s δ-matrix algorithm [

30] and the more recent modified Thomson–Haskell method proposed by Zhang [

31]. These developments have continuously improved computational efficiency and high-frequency stability, establishing a robust theoretical framework for Rayleigh wave analysis. The generalized reflection–transmission coefficient method and its subsequent modifications have further enhanced computational accuracy, enabling more efficient and stable forward modeling of Rayleigh waves. Regarding dispersion curve extraction techniques, a variety of analytical approaches have been developed for both active- and passive-source data, including the two-dimensional Fourier transform, τ–p transform, phase-shift method, Radon transform, frequency–wavenumber (f–k) analysis, spatial autocorrelation (SPAC) method, and frequency–Bessel (F–J) transform [

32,

33]. Each method offers distinct advantages in terms of resolution, noise resistance, and computational efficiency. Among them, the Radon transform and phase-shift methods excel in improving dispersion accuracy, while the SPAC and F–J approaches have extended surface wave exploration from active to passive sources, enabling cost-effective investigations in complex environments. In the domain of S-wave velocity inversion, the transition from empirical fitting to quantitative inversion represents a major milestone. Techniques such as the least-squares method, damped least-squares, genetic algorithms, simulated annealing, Occam inversion, particle swarm optimization, and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms have been successively applied to dispersion inversion, achieving high-resolution imaging of shallow subsurface structures and complex geological bodies [

34,

35,

36,

37]. The joint inversion of fundamental and higher-order modes has further improved stability and resolution, offering distinct advantages in identifying weak interlayers and delineating lithological variations.

The Microtremor Survey Method (MSM), a passive-source surface wave exploration technique, has become a vital tool for investigating shallow S-wave velocity structures since Aki first introduced the SPAC principle in 1957. Unlike active-source surveys, MSM utilizes naturally occurring or anthropogenic ambient noise as the seismic source, enabling continuous recording of subtle ground motions without blasting or site disturbance. Studies have demonstrated that microtremor signals carry rich Rayleigh-wave dispersion characteristics, which can be used to invert for subsurface S-wave velocity structures and image stratigraphic variations. Compared with conventional active-source seismic exploration, the MSM offers distinct advantages, including cost-effectiveness, operational simplicity, non-destructiveness, and strong adaptability, making it widely applicable to both large-scale crustal investigations and small-scale engineering geological surveys [

38,

39].

In terms of methodological evolution, the extraction of microtremor surface wave dispersion information has undergone a significant transition—from the frequency–wavenumber (f–k) method to the SPAC method. The f–k method, first introduced in the 1960s, effectively identifies dominant energy features across frequency bands, while Aki’s SPAC approach pioneered passive surface wave analysis by establishing a quantitative relationship between phase velocity and spatial autocorrelation coefficients through the Bessel function. With subsequent theoretical and computational advancements, the SPAC method has become one of the core techniques for near surface and urban subsurface investigations [

40]. To overcome the SPAC method’s dependence on regular array geometries, researchers later developed the Extended Spatial Autocorrelation (ESPAC) method, which enables applications under non-circular and complex terrain conditions, greatly enhancing field adaptability [

41]. Various array types—such as nested triangular and randomly distributed arrays—have since been introduced, allowing microtremor surveys to flexibly accommodate diverse acquisition environments. From a practical standpoint, the microtremor surface wave method has evolved from theoretical validation to extensive engineering applications. It has been successfully applied in geothermal resource exploration, metro tunnel investigations, landslide structure delineation, and karst and fault zone detection [

42,

43]. Studies have shown that S-wave velocity structures derived from microtremor inversion exhibit strong consistency with borehole data and can effectively identify weak interlayers, boulders, and subsurface cavities. In recent years, the advancement of two-dimensional microtremor profiling has significantly improved the resolution of large-area shallow investigations, while the introduction of high-frequency microtremor exploration has enhanced sensitivity to high-frequency surface wave energy, enabling simultaneous characterization of shallow and deeper structures [

44]. In this study, “high-frequency” microtremors refer specifically to surface-wave signals in the frequency range of 2–40 Hz, which are particularly sensitive to shallow subsurface structures and are well suited for nearshore engineering investigations. However, its application in coastal engineering exploration remains largely unexplored.

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of ambient vibration and microtremor techniques in marine and nearshore environments, including offshore structural monitoring and coastal energy-related engineering investigations [

45,

46]. These studies highlight the growing importance of passive seismic methods in complex marine settings. However, most existing works primarily focus on offshore dynamic response analysis, wave–structure interaction, or large-scale subsurface characterization. The application of high-frequency, multi-station microtremor surface-wave arrays for the purpose of detailed coastal reclamation boundary delineation remains largely unexplored and underutilized. In particular, the precise imaging of the original and reclaimed coastline boundaries in nearshore engineering environments using high-frequency ambient noise has rarely been systematically investigated. Therefore, there is a clear methodological and application gap in combining high-frequency microtremor surface-wave analysis with multi-array deployment for high-resolution coastal geomorphological boundary mapping.

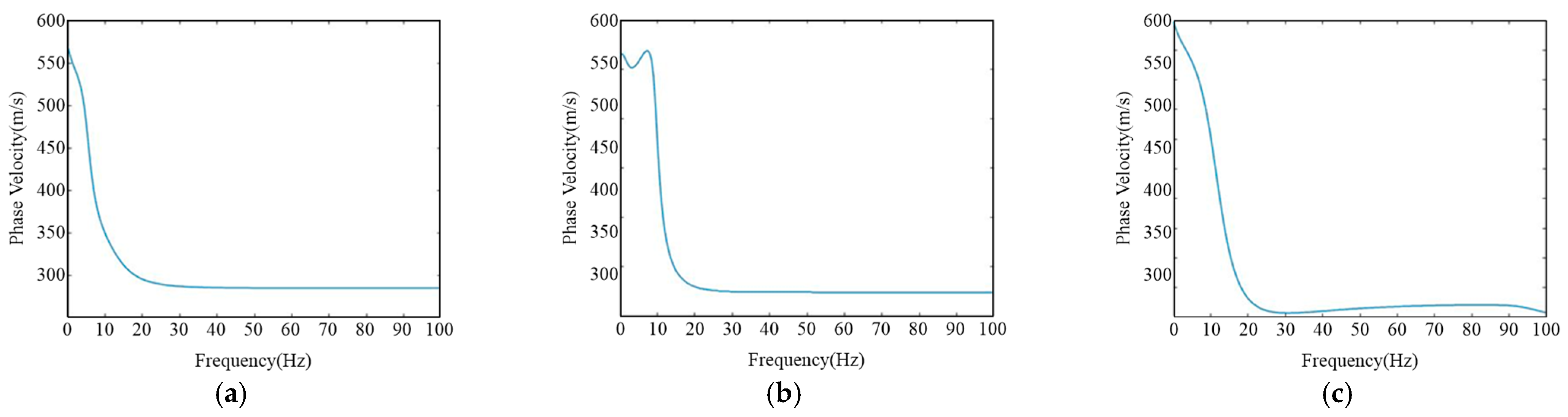

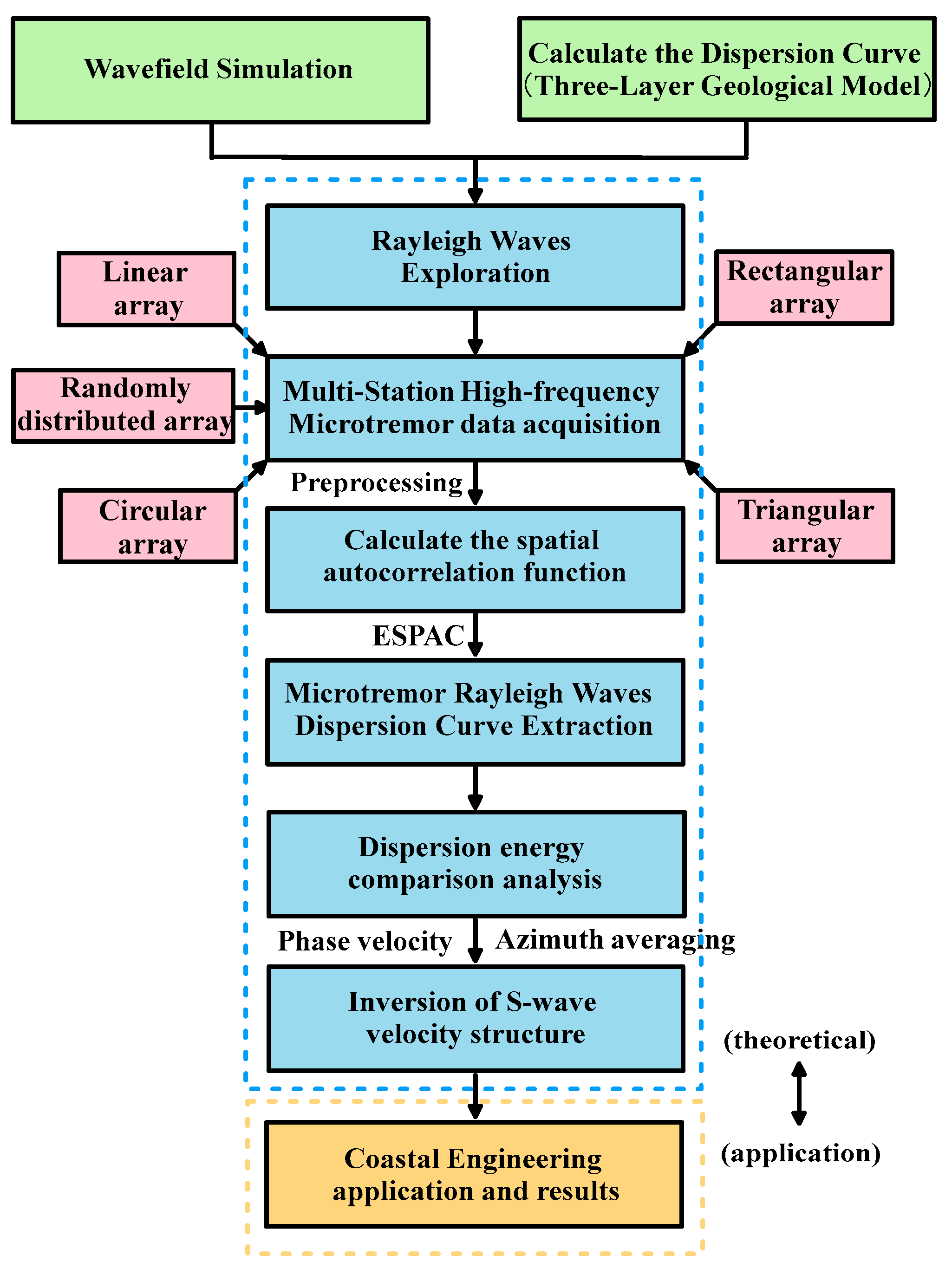

Therefore, this study begins with theoretical simulations by constructing three representative layered geological models and calculating the Rayleigh wave theoretical dispersion curves using the fast vector transfer algorithm to analyze dispersion characteristics under different stratigraphic conditions. Based on the multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface wave theory, a one-time acquisition and five-array synchronous observation strategy was employed to collect microtremor data. The ESPAC method was then used to extract dispersion curves for the five array types, and the underground S-wave velocity structure was inverted using the damped least-squares method. By comparing and analyzing the mismatch between the observed and theoretical dispersion curves across different array geometries, the optimal observation system configuration was determined. On this basis, a multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface wave exploration approach is proposed for high-resolution subsurface characterization in coastal engineering. Field measurements were conducted on the Dongzhou Peninsula in Fujian Province, where dispersion curve inversion successfully revealed the shallow subsurface S-wave velocity structure, enabling a refined stratigraphic division of the coastal engineering site.

3. Results and Discussion

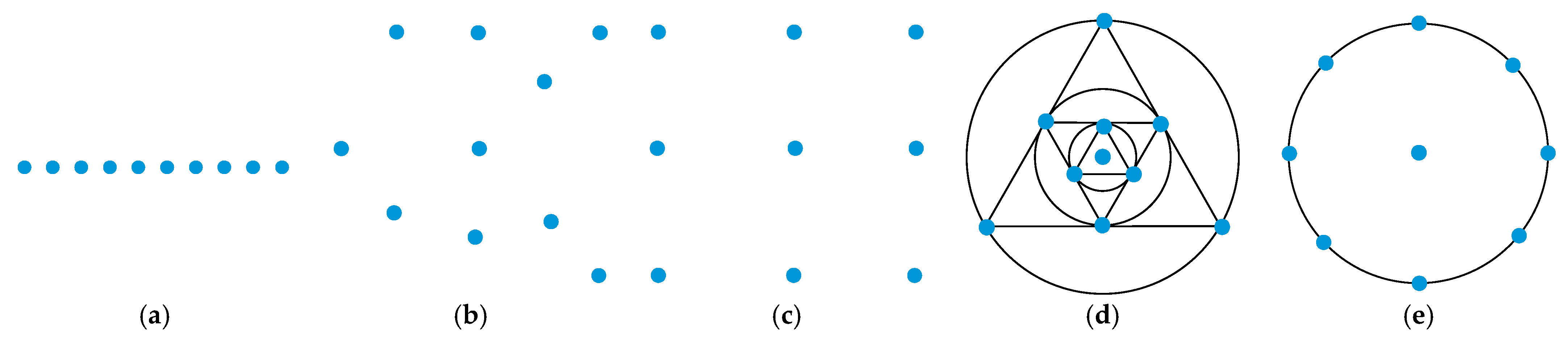

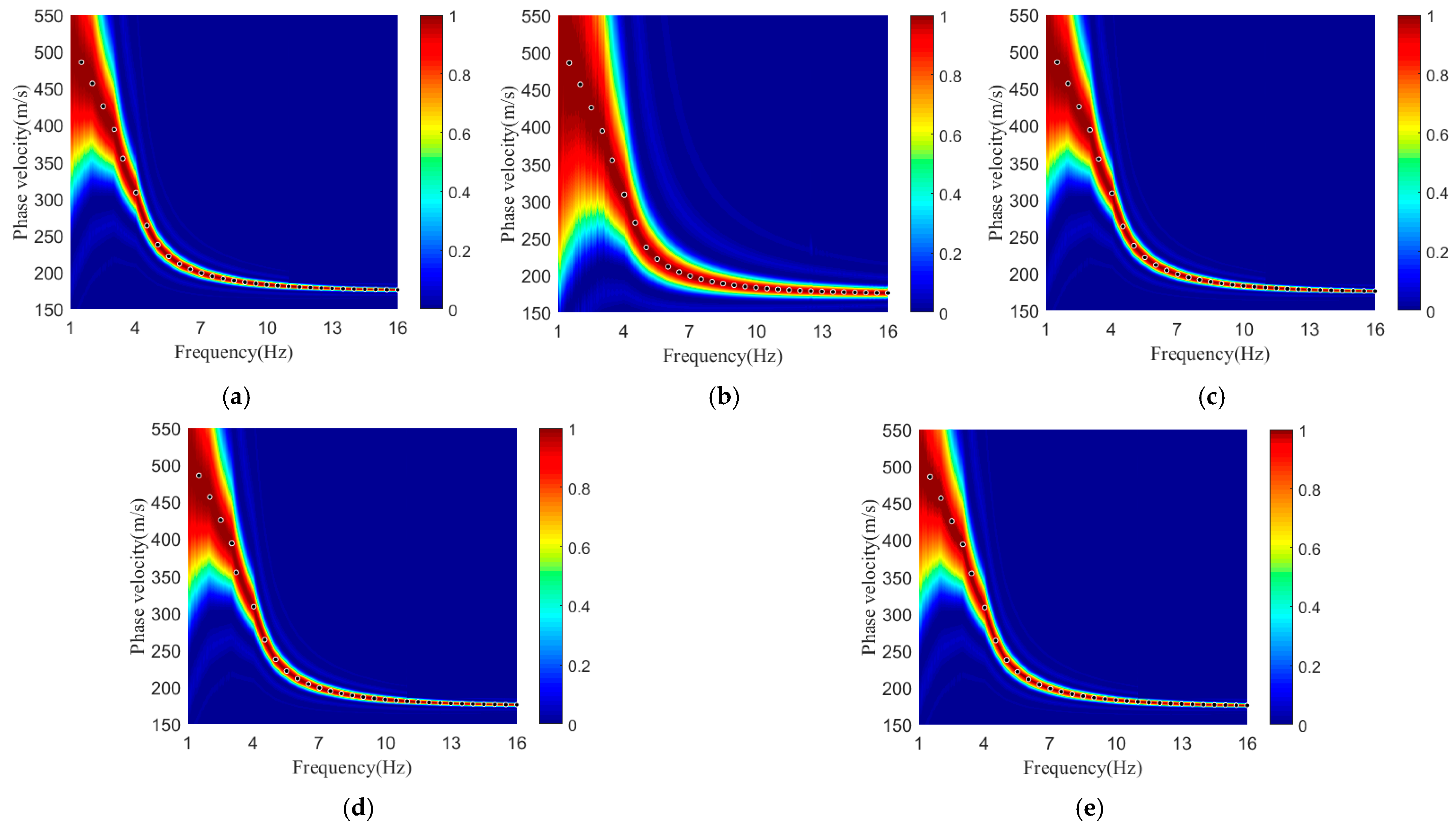

3.1. Discussion of Dispersion Curves for Different Observation Array

The accuracy of the obtained dispersion curves varies with different observation ar-ray configurations. Therefore, in this experiment, a two-dimensional rectangular array layout was adopted for data acquisition, consisting of 7 rows and 7 columns with a total of 49 geophones. The spacing between adjacent geophones in the east–west direction was fixed at 4 m, while the spacing in the north–south direction simulated the layout of actual road networks, with an 8 m separation between the two central lines and 3 m spacing between the outer lines. Based on a single data acquisition, five common types of observation arrays frequently used in practical applications were designed, all centered at the midpoint of the middle line: linear, square, circular, and nested triangular arrays (as shown in

Figure 4). The maximum aperture lengths of the five arrays were 24 m, 32.56 m, 24 m, and 28 m, respectively.

The maximum investigation depth was estimated based on the effective wavelength criterion of Rayleigh waves. According to the widely adopted empirical relationship, the reliable exploration depth of surface waves is approximately 0.5 times the maximum wavelength. The lowest reliable frequency obtained from the ESPAC analysis was ap-proximately 2 Hz, and the corresponding Rayleigh-wave phase velocity was about 480 m/s. Therefore, the maximum wavelength is estimated as λ_max = 240 m, yielding a maximum investigation depth of approximately 120 m by these arrays was approximately 120 m. Comparative analysis of the results allows for the determination of the optimal observation array configuration for field applications.

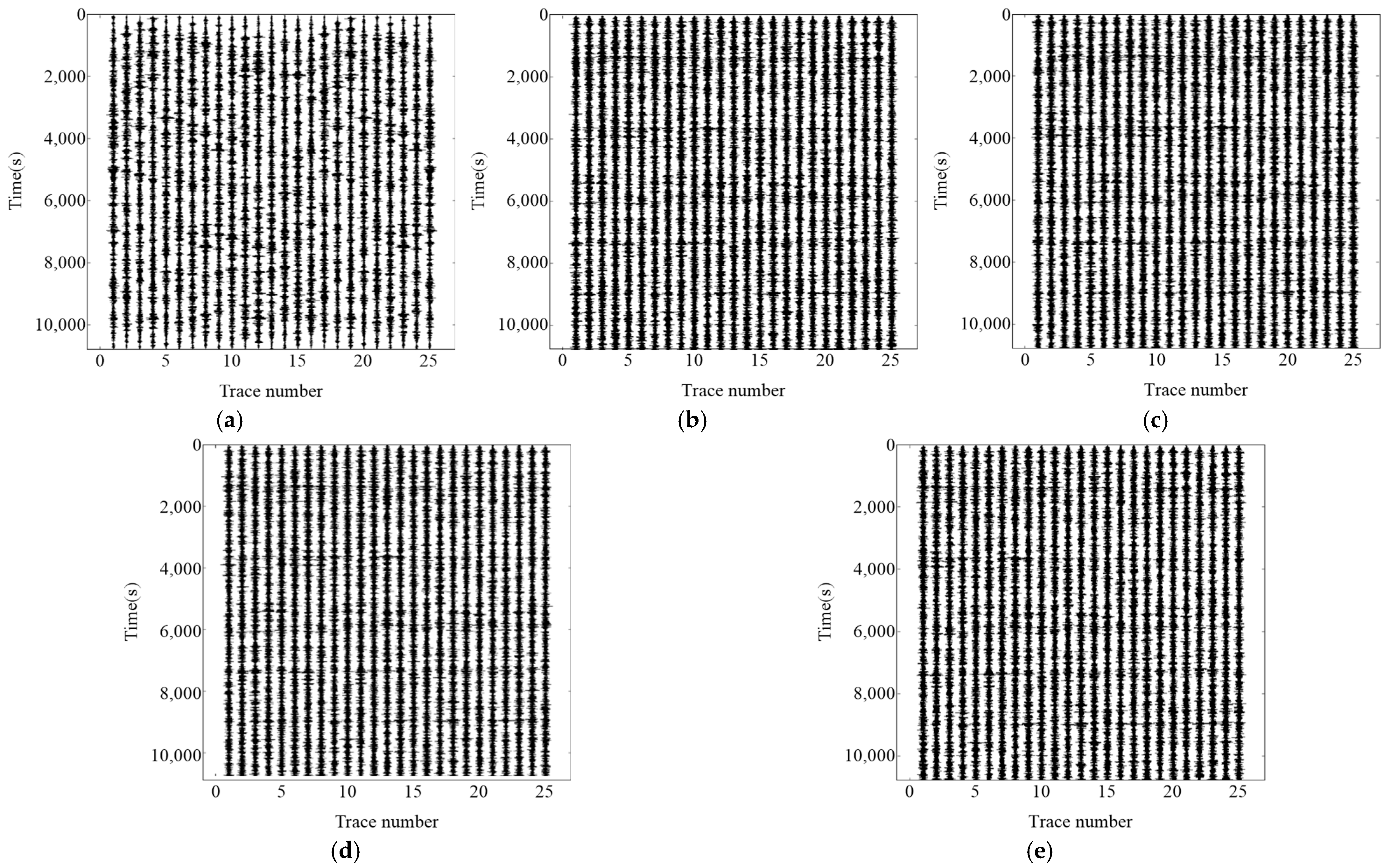

To compare the variations in dispersion curves resulting from different array types, each setup consisted of 25 geophones, yielding 25 recording channels with a maximum array length of 120 m. In the linear array, the spacing between adjacent sensors was 5 m, while in both the randomly distributed and circular arrays, the maximum distance between geophones was also 120 m. The rectangular array was arranged in a 5 × 5 grid configuration. Based on theoretical numerical simulations, microtremor signals were generated for the four array types (

Figure 5), with a recording duration of three hours for each configuration.

Before extracting the dispersion curves from the ambient noise records, the microtremor signals were preprocessed to improve data quality and ensure the reliability of subsequent analysis. First, spectral analysis of each geophone record was performed to determine the effective frequency range for digital filtering. Detrending was then applied to eliminate long-period drift caused by sensor aging or spring relaxation; the Hilbert–Huang Transform (HHT) method was adopted, which decomposes the signal into a series of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) until only a monotonic residual remains, and this residual is removed from the original signal to achieve trend elimination. The mean value of the signal was subsequently removed to eliminate the zero-frequency (DC) component. Digital filtering was conducted based on the useful frequency range identified from spectral analysis to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio by suppressing interference bands. To further reduce transient spikes and instrument-related artifacts, time-domain normalization using the one-bit normalization technique was applied, effectively preserving signal polarity while equalizing amplitude. Finally, spectral whitening was performed to smooth the non-flat energy distribution of the ambient noise spectrum, suppressing dominant frequency peaks and broadening the usable frequency bandwidth, thereby improving the stability and accuracy of the extracted dispersion curves.

After preprocessing the theoretical microtremor data, the SPAC method was applied to compute the dispersion curves. Prior to calculating the dispersion characteristics, it is necessary to evaluate the cross-correlation spectra between station pairs. To determine the cross-correlation coefficients between any two stations, an appropriate time window must first be selected. The window length and the effective correlation duration are key parameters: the cross-correlation function is computed for each time segment and then stacked to enhance signal stability.

The choice of time window directly affects the resolution of the dispersion curve. Within each window, the microtremor signal must maintain temporal and spatial stationarity, with consistent frequency content. If the window is too long, the number of stacking operations becomes insufficient, reducing resolution; conversely, an excessively short window may result in the loss of useful surface-wave information and decreased imaging quality. Therefore, the window length must be carefully selected based on factors such as sampling rate and array geometry.

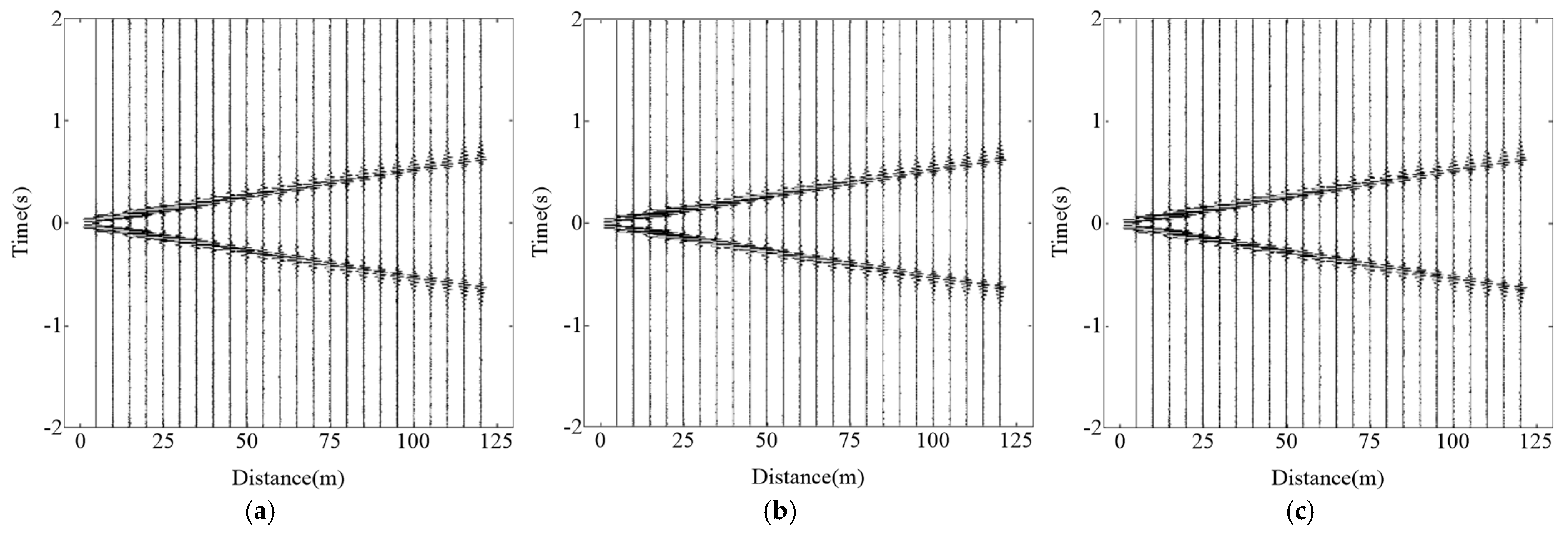

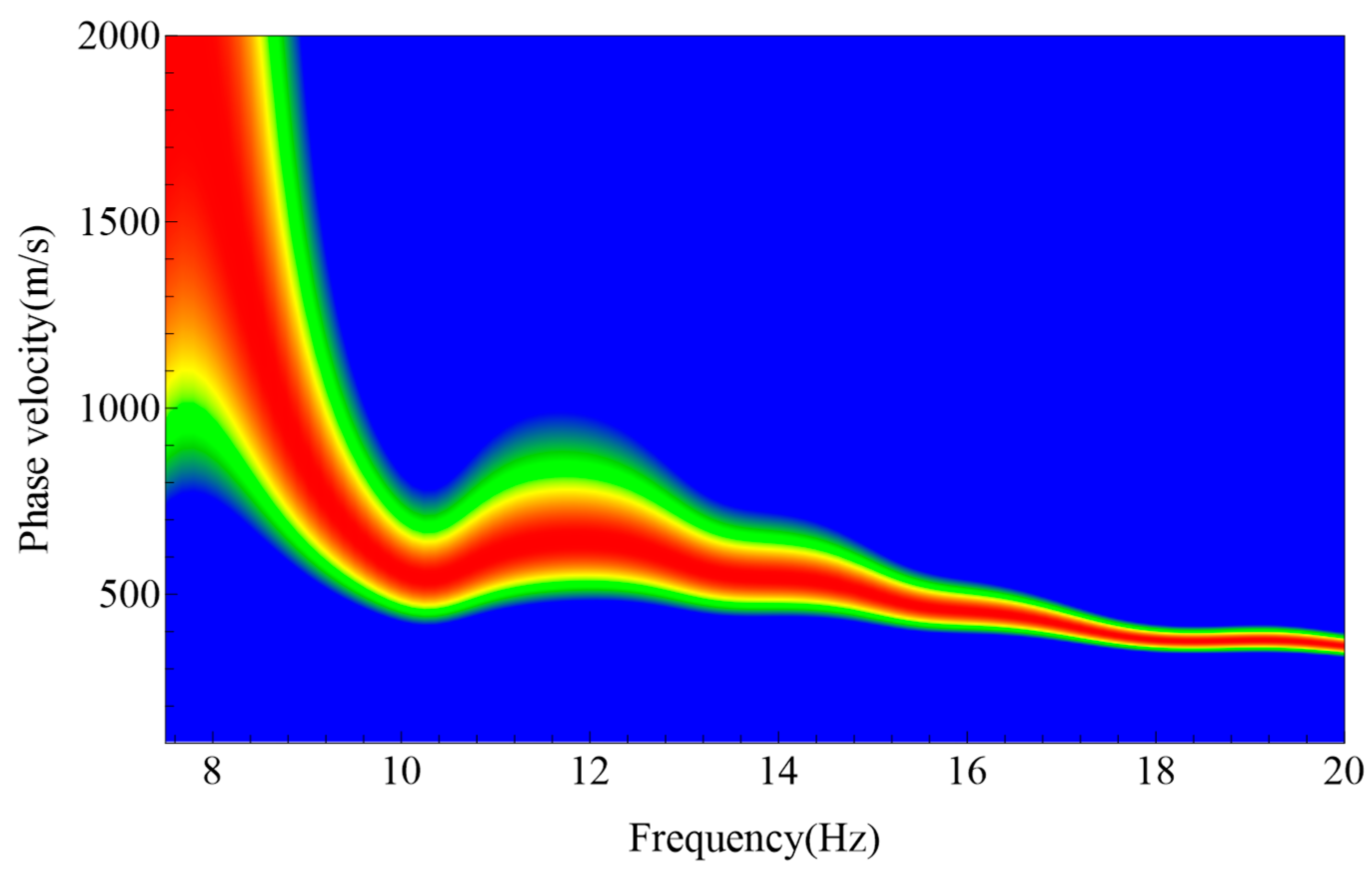

Through testing and validation, the total recording duration of three hours was divided into six segments, each lasting 30 min. A time window of 30 s and an effective correlation length of 2 s were adopted, resulting in 60 stacking iterations per segment. The obtained cross-correlation functions are shown in

Figure 6, where clear and continuous in-phase axes can be observed. The frequency range used for analysis was 1–10 Hz, and by fitting the results with the Bessel function, the dispersion energy map (

Figure 7) was generated. The dispersion curves are clearly imaged with distinct energy distributions. The black solid dots in the figure represent the theoretical dispersion curves calculated using the fast vector transfer algorithm, which show excellent agreement with the forward-modeled dispersion results.

3.2. Comparison and Analysis of Dispersion Curves and Inversion Results

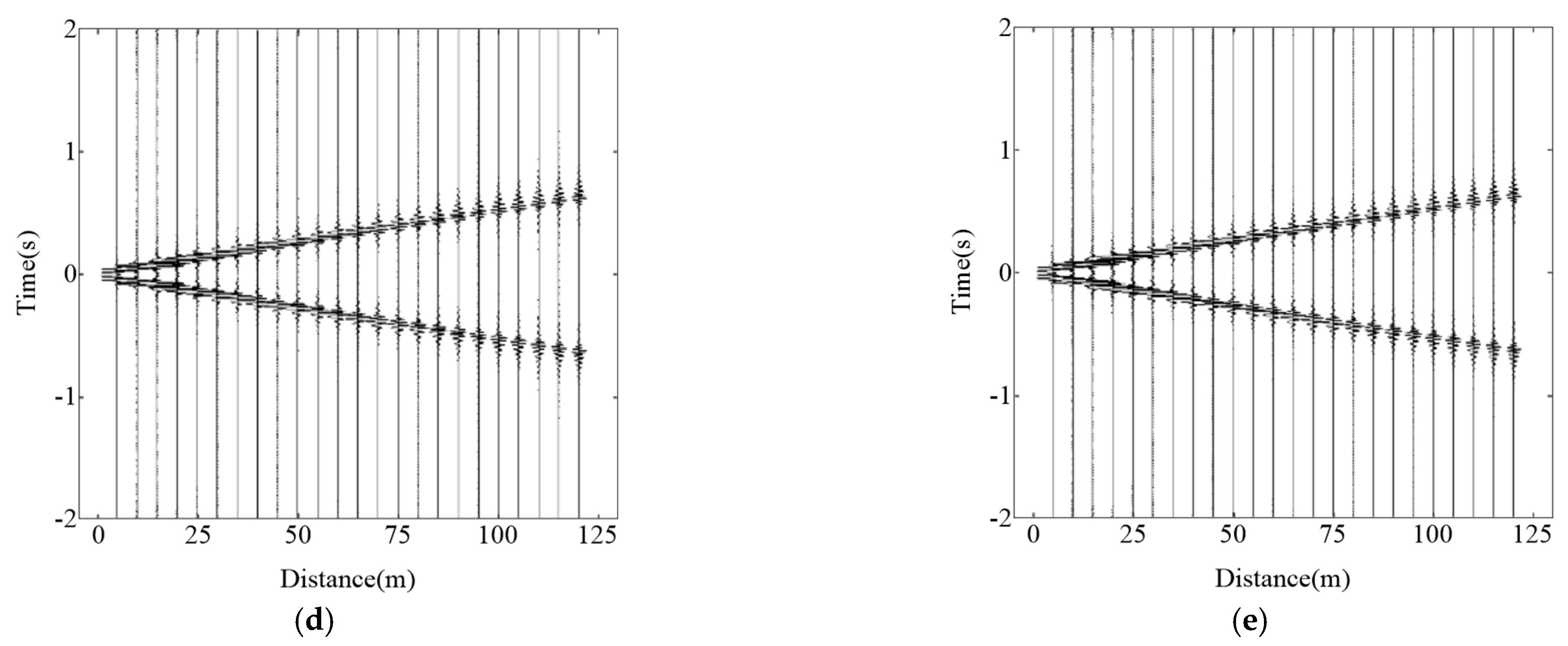

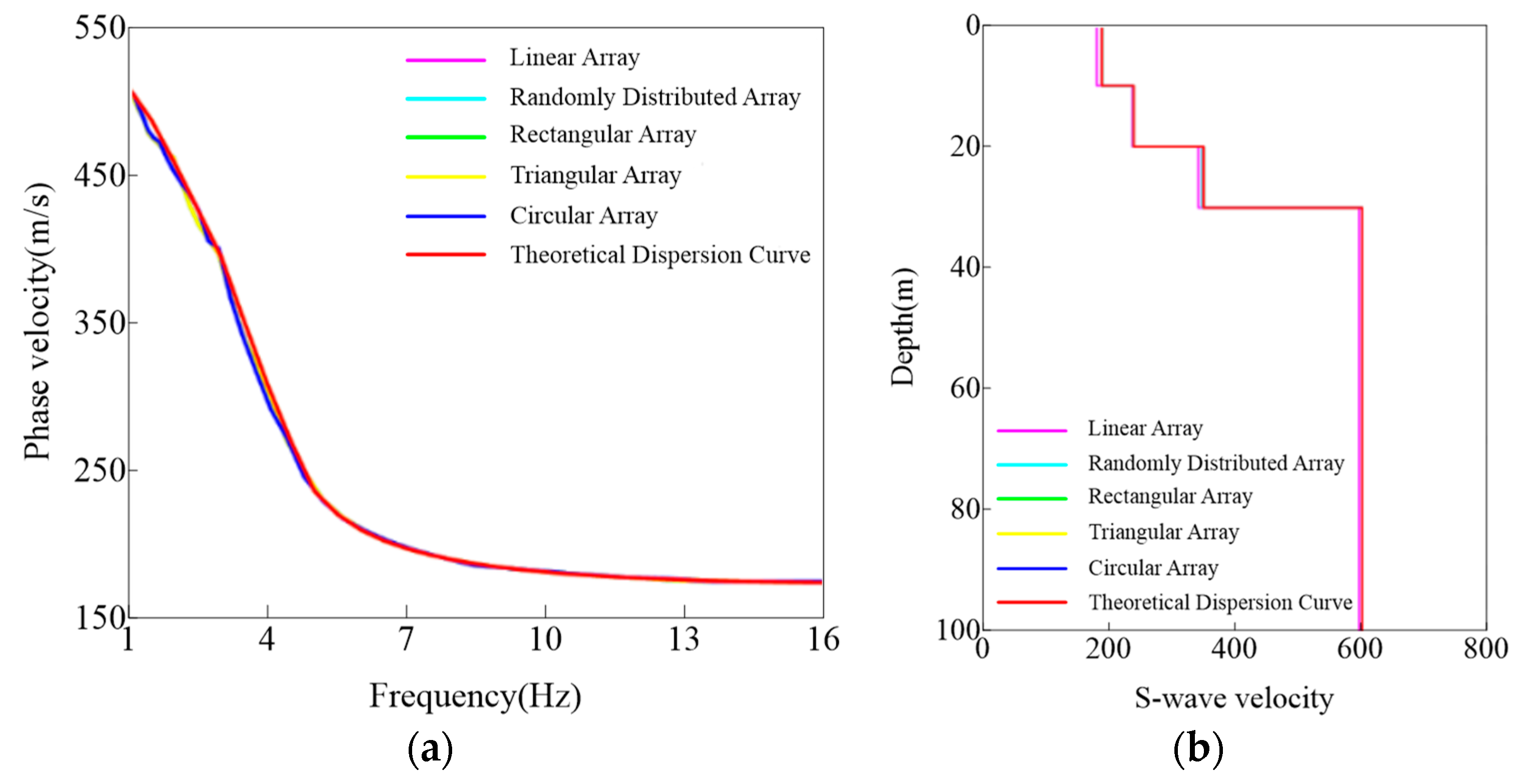

A comparative analysis of the dispersion curves extracted from the five array types is presented in

Figure 8. In

Figure 8a, the blue curve represents the circular array, the yellow the triangular array, the green the square array, the light blue the linear array, and the red curve denotes the theoretical dispersion curve calculated using the fast vector transfer algorithm. Overall, the dispersion curves obtained from the five arrays agree well with the theoretical prediction. The linear and random arrays exhibit slight deviations from the theoretical curve at higher frequencies, and their low-frequency curves appear less smooth, indicating minor inconsistencies, though the discrepancies remain small. The random array also shows imperfect matching in the low-frequency range. In contrast, both the triangular and circular arrays yield dispersion curves that align almost perfectly with the theoretical results. As shown in

Figure 8b, the inversion results likewise demonstrate good agreement with the theoretical model. Except for the linear array—which displays noticeable mismatches at depths of approximately 0–10 m and 20–30 m—the remaining array types produce inverted S-wave velocity structures that closely match the theoretical model. These observations indicate that among the five tested array geometries, the rectangular, triangular, and circular arrays provide superior dispersion imaging and, consequently, more reliable inversion results.

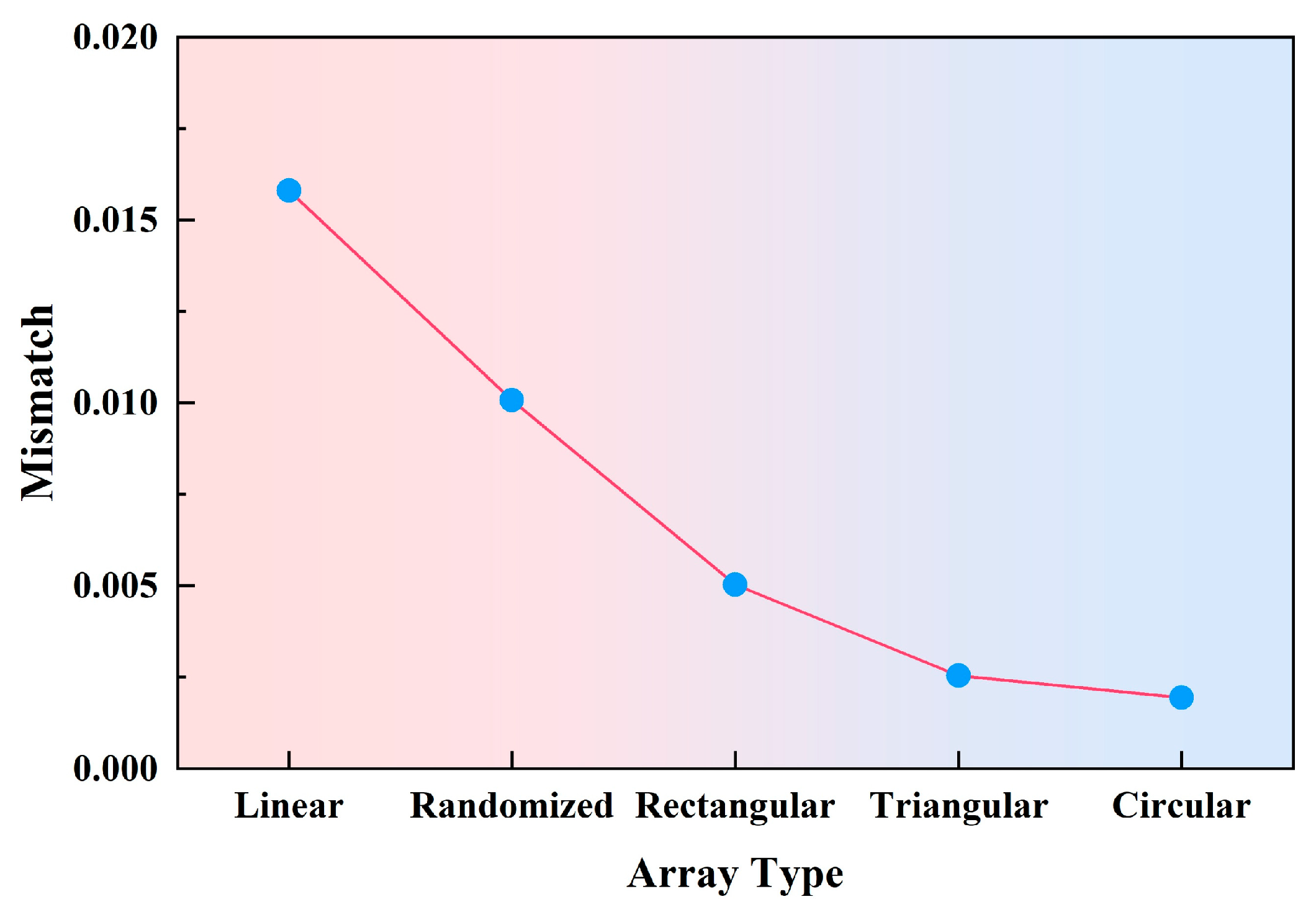

The degree of mismatch between the dispersion curves extracted by the two methods for each array configuration was calculated to evaluate their fitting consistency. The mismatch can be computed using the following equation:

where

vij represents the dispersion curve extracted using the SPAC method,

voj represents the theoretical dispersion curve, and

N denotes the total number of data points along the dispersion curve. where RMS denotes the root mean square, and RMSE denotes the root mean square error. The calculation results obtained using Equation (8) are shown in

Figure 9. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the fitting accuracy of the dispersion curves improves progressively across the five array types. Among them, the rectangular, triangular, and circular arrays exhibit superior fitting performance, with fitting errors all below 0.5%.

The propagation of dispersion-curve mismatches into the inverted shear-wave velocity (Vs) structure and layer thickness exhibits clear depth-dependent characteristics. From a theoretical perspective, mismatches at high frequencies mainly affect the shallow subsurface, as these frequencies are sensitive to near-surface materials, whereas low-frequency mismatches primarily propagate into deeper layers and influence both Vs and layer depth estimates. As shown in

Figure 9, the observed inversion results are consistent with this expected behavior. For the linear and randomly distributed arrays, the relatively larger mismatches observed at high frequencies lead to noticeable uncertainties in the shallow Vs structure, while low-frequency discrepancies result in instability in the deeper velocity layers and interface depths. In contrast, the rectangular, triangular, and circular arrays exhibit systematically lower mismatch levels across both high- and low-frequency ranges, which effectively suppresses error propagation into both shallow and deep inverted structures. Specifically, the reduced low-frequency mismatch for these three optimized array geometries significantly constrains deep-layer thickness estimates, while their stable high-frequency performance ensures reliable delineation of shallow low-velocity layers and fill materials. This dual-frequency stability directly translates into more robust and physically meaningful S-wave velocity models. From an engineering perspective, these observations indicate that dispersion-curve mismatch does not propagate uniformly with depth but instead exhibits frequency-controlled uncertainty amplification. The optimized array geometries minimize this amplification, thereby enhancing the reliability of shallow foundation assessment, weak interlayer identification, and reclaimed-land boundary delineation.

From a geophysical and statistical perspective, these symmetric, multi-azimuth array geometries ensure more uniform spatial sampling of the wavefield, which better satisfies the quasi-isotropic assumption required by SPAC/ESPAC theory. The multi-directional inter-station paths significantly enhance the stacking efficiency of spatial autocorrelation functions and improve the stability of dispersion energy imaging. In contrast, linear arrays suffer from strong directional bias and limited azimuthal coverage, while random arrays exhibit irregular inter-station spacing that degrades statistical convergence. Therefore, symmetric two-dimensional arrays are more suitable for coastal ambient-noise surveys characterized by complex wavefields and strong directional noise sources.

Based on these results, it can be concluded that among the tested array configurations, the rectangular array exhibits the most stable and reliable overall performance under both theoretical simulations and practical field conditions, and is therefore recommended as the preferred configuration for engineering applications. Although the triangular and circular arrays also demonstrate good dispersion imaging capability under ideal conditions, their practical deployment is often constrained by site accessibility, terrain limitations, and layout feasibility. In contrast, the linear array shows comparatively inferior performance, particularly in terms of dispersion resolution and inversion stability.

4. Coastal Engineering Application and Results

The numerical simulations presented in

Section 3 establish the theoretical foundation for the subsequent field investigation and directly guide the design of the observation scheme and data processing strategy. By constructing representative layered geological models and calculating the corresponding theoretical Rayleigh-wave dispersion curves using the fast vector transfer algorithm, the sensitivity of dispersion characteristics to different stratigraphic structures was systematically analyzed. These results provide a quantitative reference for determining the effective frequency band for shallow subsurface imaging, which directly supports the selection of the high-frequency range (2–40 Hz) adopted in the field data processing.

In addition, the simulation-based comparison of dispersion extraction and inversion performance under different array geometries provides essential guidance for optimizing the field observation layouts. On this basis, five representative array configurations were designed for high-frequency ambient noise acquisition, allowing a comprehensive evaluation of the influence of array geometry on dispersion stability and inversion reliability. The simulated dispersion curves further serve as benchmark references for assessing the consistency and accuracy of the field-extracted dispersion results.

Therefore, the field experiment described in

Section 4 is not an independent application, but rather a direct engineering validation and practical extension of the theoretical and numerical findings.

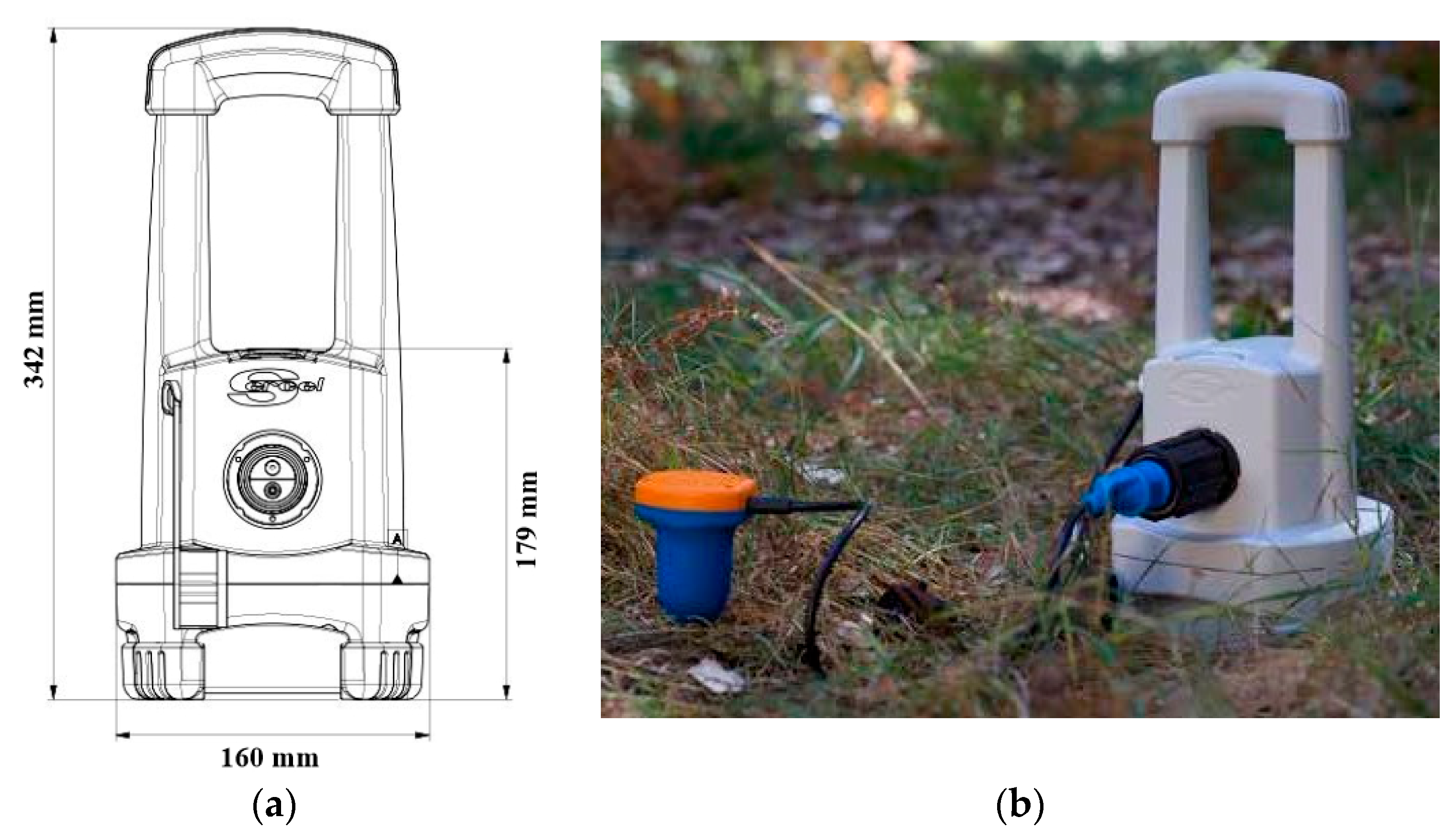

4.1. Instruments and Equipment

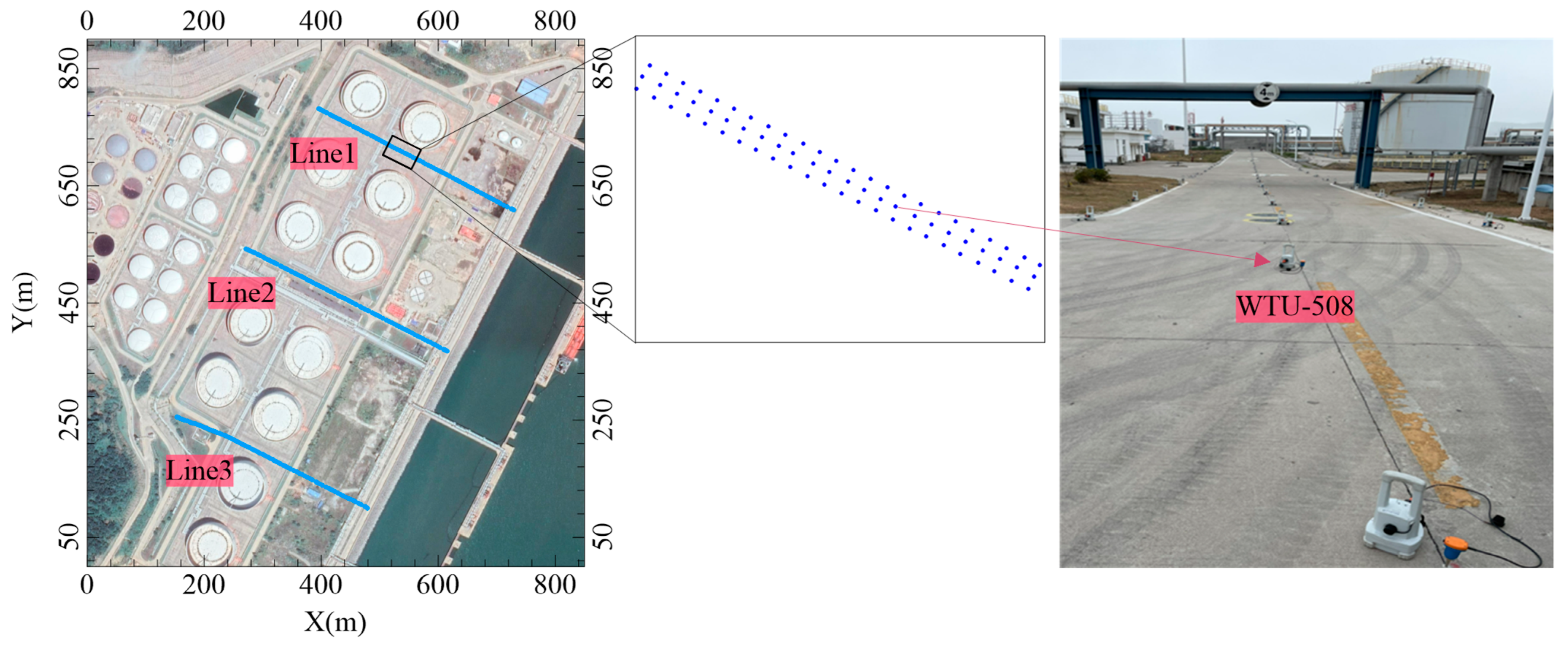

The instrument used for ambient noise data acquisition in this study was the WTU-508, developed by Sercel (Nantes, France) (

Figure 10). The WTU-508 is a single-channel autonomous land node that stores seismic data internally, with a recording capacity of up to 30 days. Benefiting from Sercel’s innovative XT-Pathfinder technology, the system enables 100% real-time quality control directly on the instrument. Fully integrated into the 508XT platform, it further strengthens the 508XT’s position as a new benchmark for land seismic data acquisition. The geophones employed were SG-5 high-sensitivity seismic sensors, featuring a natural frequency of 5 Hz.

4.2. Engineering Application

4.2.1. Survey Area Overview

Based on the simulation-guided observation strategy described above, a field microtremor survey was conducted on the Dongzhou Peninsula, Hui’an County, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, to validate the performance of the proposed high-frequency multi-station surface-wave method in a real coastal engineering environment. It lies in the northern part of Quanzhou Bay and within the Douwei Port area of Meizhou Bay, possessing a distinct advantage in marine geographic location. Geologically, the area is situated in the central segment of the Mindong volcanic fault–depression zone and has undergone multiple episodes of magmatic activity and tectonic movement throughout its geological history. These processes have resulted in a bedrock structure dominated by miarolitic alkali-feldspar granite and hybrid monzonitic granite. The presence of multiple levels of marine erosion terraces around the area indicates active neotectonic movements. The degree of bedrock weathering within the survey area varies significantly. The bedrock is overlain by loose Quaternary marine, alluvial, and diluvial deposits, forming an engineering geological setting characterized by competent bedrock with high bearing capacity and an overlying compressible cover layer. The coastline alternates between erosional granitic mountain shores and sedimentary sandy–muddy coasts, where shoreline stability requires appropriate engineering protection measures.

To further strengthen coastal infrastructure and expand usable land resources, large-scale reclamation projects have been carried out in the Dongzhou Peninsula area.

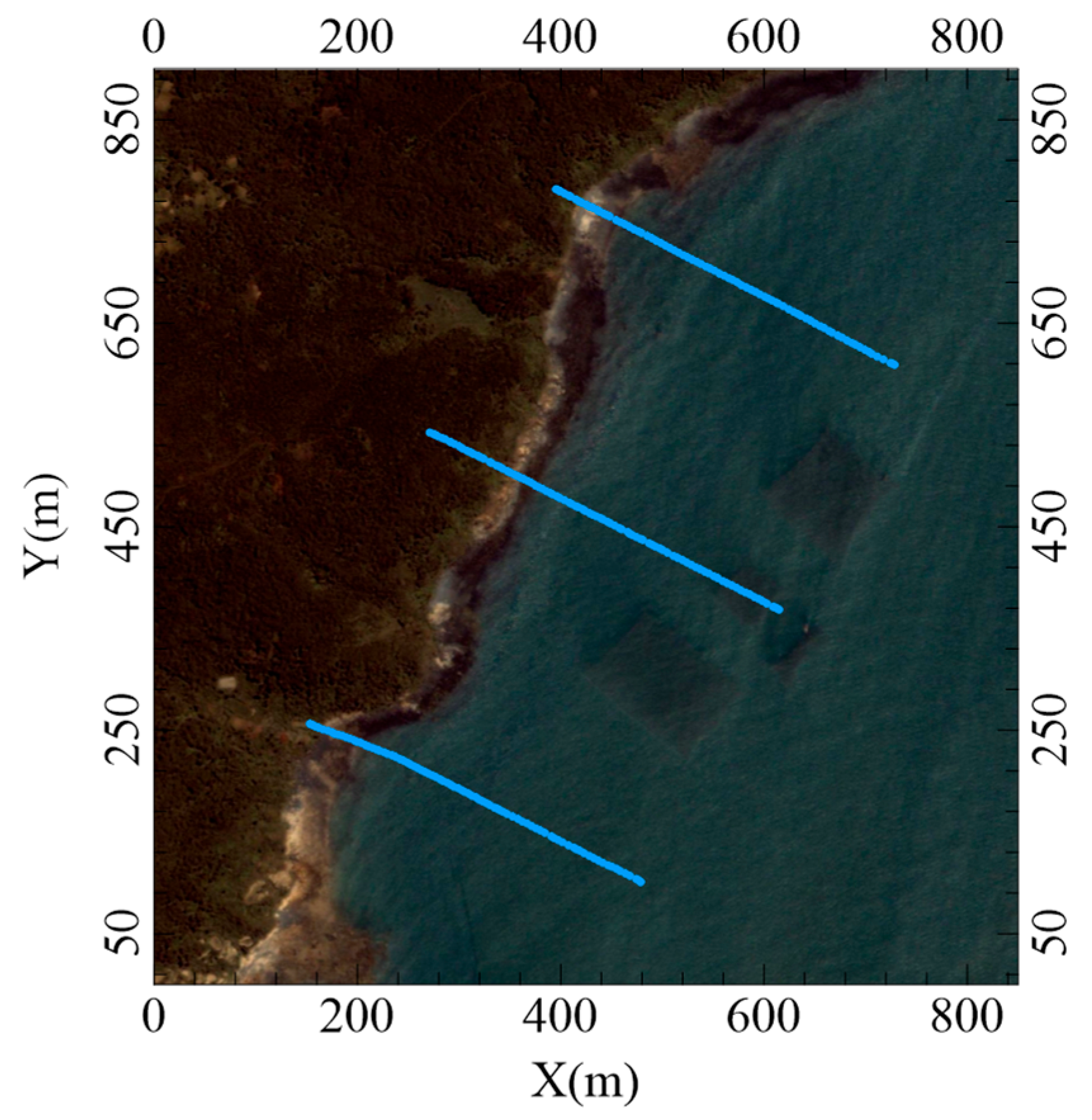

Figure 11 shows the coastline prior to reclamation, while

Figure 12 illustrates the present configuration after the completion of the reclamation project. The newly formed coastal zone has significantly extended the shoreline seaward, providing additional space for marine engineering construction and industrial development. By applying the proposed multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface wave exploration method to this area, it is possible to accurately delineate the original shoreline boundary beneath the reclaimed ground. This verification demonstrates the reliability and precision of the proposed method in identifying subsurface geological transitions associated with coastal reclamation.

4.2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

In this study, the multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface wave survey was conducted using the observation system shown in

Figure 12. A rectangular array configuration was adopted, with an inter-station spacing of 3.5 m and a line spacing of 5 m. A total of 246 WTU-508 autonomous seismic nodes were deployed, and each station recorded continuously for no less than 2.5 h at a sampling interval of 2 ms. This setup enabled the acquisition of a dense, high-quality high-frequency ambient noise dataset suitable for multi-station microtremor analysis. Subsequently, the acquired field microtremor data were first preprocessed using normalized spectral analysis, including detrending, demeaning, digital band-pass filtering, time-domain normalization, and spectral whitening. Based on the effective frequency range of Rayleigh-wave dispersion observed in both the numerical simulations and the field data, a band-pass filter of 2–40 Hz was applied. Frequencies lower than 2 Hz were generated by the interaction of opposing ocean wave systems during storms in shallow and deep marine environments, while frequencies higher than 40 Hz exhibited rapidly decaying surface-wave energy and poor signal stability due to attenuation and array aperture limitations. After band-pass filtering, the ESPAC analysis was conducted using time windows of varying lengths to ensure both statistical stability and effective identification of transient disturbances. A long-duration window of 30 s was adopted to characterize the stable background noise field, while a short-duration window of 1 s was used to capture short-term abnormal signals induced by human activities or instrumental interference. Anomaly detection was performed by comparing the mean amplitudes of the short- and long-time windows. Data segments were classified as anomalous and excluded from subsequent analysis if the short-time mean exceeded 2.5 times or fell below 0.20 times the long-time mean. These threshold values were determined based on repeated tests on multiple ambient noise records and are also consistent with those widely adopted in previous microtremor studies to achieve a balance between effective noise suppression and signal preservation. The resulting ESPAC frequency–coefficient curves are presented in

Figure 13.

4.2.3. Data Interpretation and Results

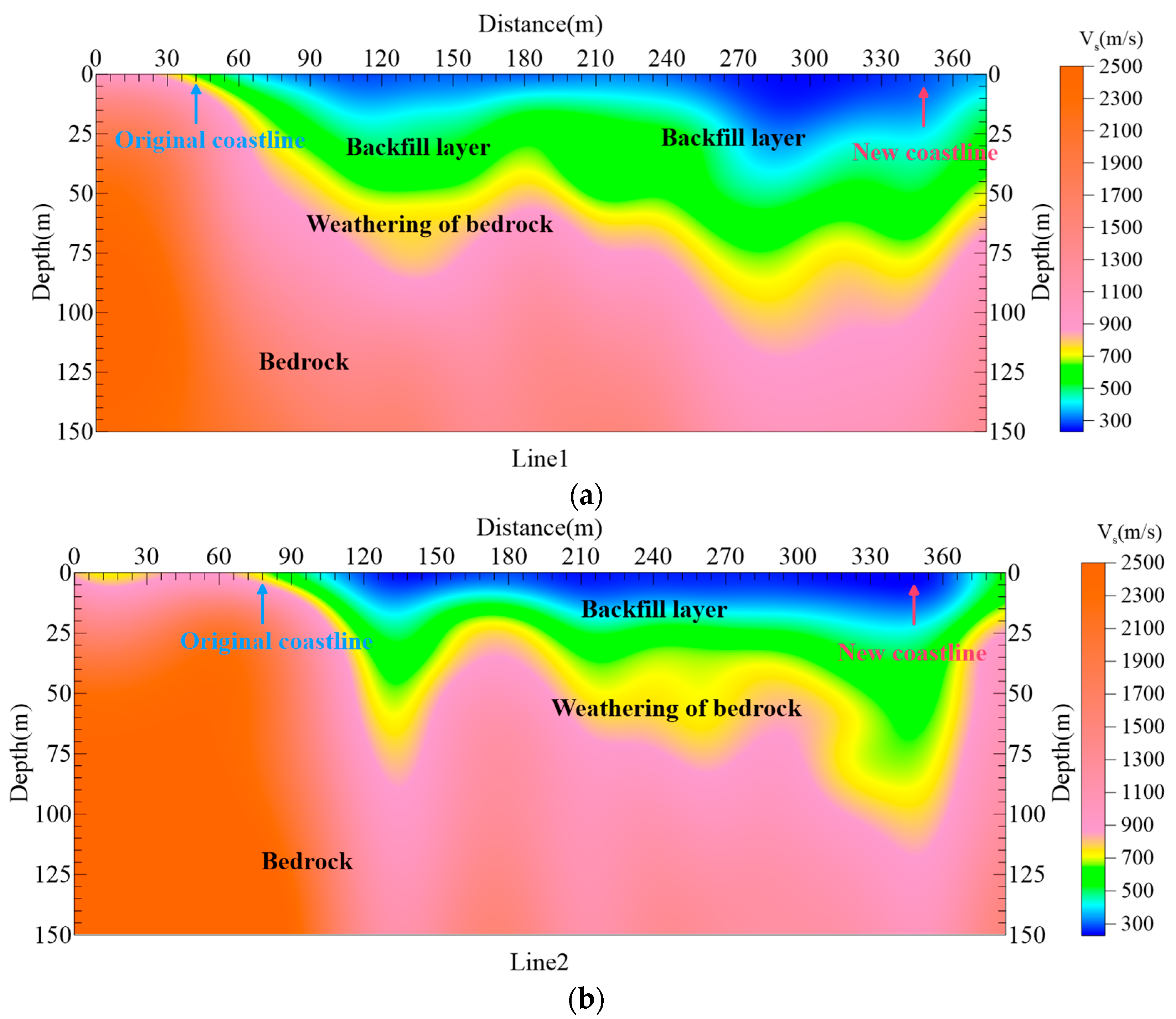

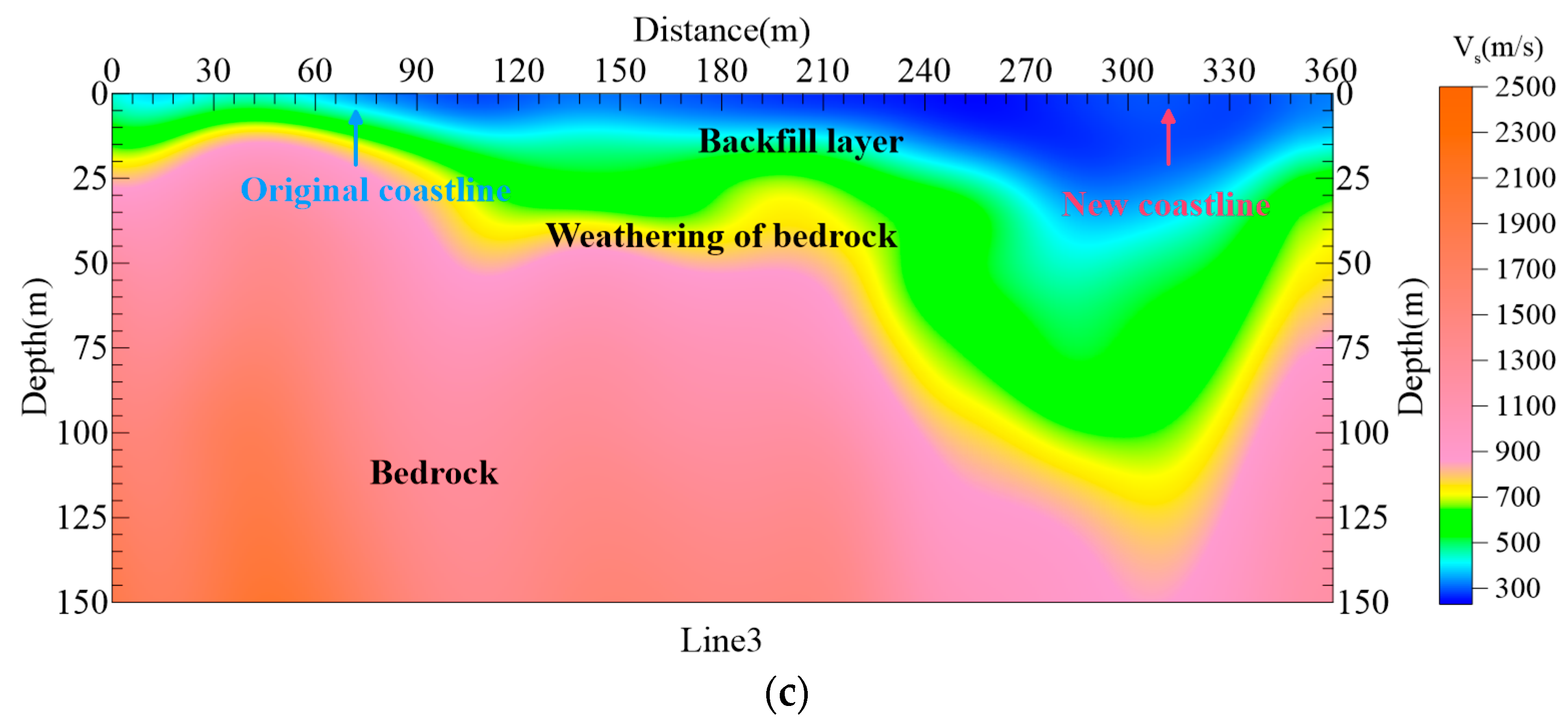

After dispersion curves were extracted using the proposed method, the subsurface shear-wave velocity structures beneath each survey line were inverted using a damped least-squares inversion scheme. The model parameters included the shear-wave velocity (Vs) and the thickness of each subsurface layer. During the inversion process, initial models were constructed based on the general geological conditions of the study area, and the model parameters were iteratively updated to minimize the misfit between the observed and theoretical dispersion curves. The inversion procedure was terminated when either of the following stopping criteria was satisfied: (1) the maximum number of iterations reached 10, or (2) the relative fitting error between the observed and simulated dispersion curves decreased to below 5%. This strategy ensured both the stability of the inversion results and computational efficiency. The final inverted shear-wave velocity profiles for the three survey lines are shown in

Figure 14.

Based on regional engineering geological conditions and the inversion results shown in

Figure 14, the S-wave velocity (Vs) structure of the survey area can be classified into four typical categories: Vs < 400 m/s corresponds to reclaimed sandy fill materials formed during the marine reclamation process; Vs of 400–700 m/s represents silty clay of moderate stiffness mixed locally with gravel fragments derived from weathered bedrock; Vs of 700–900 m/s indicates moderately weathered granitic bedrock; and Vs > 900 m/s corresponds to slightly weathered to fresh bedrock with high mechanical strength. From an engineering perspective, layers with Vs lower than 700 m/s are regarded as the reclaimed overburden, while the zones with Vs exceeding 700 m/s represent weathered and intact bedrock formations.

Figure 14a presents the S-wave velocity profile along Line 1. Along Line 1, the near-surface zone from 0 to approximately 42 m is dominated by low velocities below 700 m/s, indicating reclaimed sandy fill and silty clay deposits, which are characterized by high compressibility and relatively low bearing capacity. Beyond this distance, Vs rapidly increases to 700–900 m/s and locally exceeds 900 m/s, marking a clear transition into weathered and intact granitic bedrock near the newly constructed seawall. This sharp velocity contrast reliably delineates the boundary between the reclaimed layer and the original geological foundation.

Figure 14b shows the S-wave velocity profile for Line 2. A similar structural pattern is observed along Line 2, where the original coastline is inferred near 78 m based on the abrupt transition from reclaimed soft sediments (Vs < 700 m/s) to weathered bedrock (Vs > 700 m/s). Toward the outer boundary at approximately 348 m, the velocity again increases beyond 900 m/s, corresponding to the newly constructed revetment founded on competent bedrock.

Figure 14c illustrates the S-wave velocity structure along Line 3. Along Line 3, due to its different spatial position, the former coastline is inferred at approximately 72 m, while the new seawall is identified at around 312 m based on consistent Vs transitions. From a geotechnical standpoint, the widespread presence of Vs < 400 m/s reclaimed sandy fill indicates loose structure and limited natural bearing capacity, requiring ground improvement measures before large-scale coastal infrastructure construction. The Vs range of 400–700 m/s suggests silty clay layers of moderate stiffness, which are prone to long-term settlement and exhibit non-negligible liquefaction susceptibility under seismic loading. In contrast, the 700–900 m/s zone represents moderately weathered granitic bedrock, which can serve as a secondary bearing layer, while the Vs > 900 m/s formation corresponds to competent bedrock, providing a stable primary foundation for coastal engineering structures. Comparison with the actual pre- and post-reclamation coastline boundaries (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) confirm the consistency of the inversion results. These results demonstrate that the proposed high-frequency microtremor surface wave method can not only accurately delineate reclaimed boundaries but also quantitatively characterize subsurface stratification and engineering properties essential for nearshore foundation design.

4.3. Limitations and Applicability of the Proposed Method

Despite the encouraging results obtained in both numerical simulations and field applications, several limitations of the proposed multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface-wave method should be acknowledged. First, the method is inherently sensitive to strong directional noise sources, such as heavy traffic, construction machinery, or localized industrial activities. These sources may violate the assumption of an isotropic ambient noise field required by SPAC and ESPAC theories, potentially introducing bias into the estimated dispersion curves if not adequately suppressed through preprocessing and azimuthal averaging.

Second, the inversion strategy adopted in this study is based on a 1D layered Earth assumption, which implies lateral homogeneity beneath each array center. In areas characterized by strong lateral heterogeneity, such as abrupt lithological transitions or complex reclamation structures, the 1D inversion may lead to local smearing effects and reduced structural resolution. Future studies could benefit from extending the approach toward quasi-2D or full 2D inversions.

Finally, the applicability of the proposed method is also site-dependent. Its effectiveness is optimal in coastal and nearshore environments where sufficient high-frequency ambient noise energy is available and where reclamation fills and weathered bedrock exhibit distinct velocity contrasts. In environments with extremely weak ambient noise excitation or highly heterogeneous near-surface conditions, supplementary active-source surveys or borehole constraints may be required to improve reliability.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface-wave exploration method was proposed and successfully applied to characterize shallow subsurface structures in a coastal engineering environment. Three representative layered geological models were first constructed, and Rayleigh-wave theoretical dispersion curves were computed using the fast vector transfer algorithm to systematically analyze the intrinsic dispersion characteristics associated with different subsurface conditions. Numerical simulations demonstrate that distinct geological configurations exhibit clearly different dispersion behaviors, providing a quantitative theoretical basis for subsequent dispersion extraction and S-wave velocity inversion.

Building upon this theoretical foundation, the influence of array acquisition strategies was comprehensively investigated using five array geometries (linear, random, rectangular, triangular, and circular). High-frequency ambient noise data were preprocessed through normalized spectral analysis and processed using the ESPAC method to extract dispersion curves. Quantitative mismatch analysis between theoretical and observed dispersion curves indicates that the rectangular, triangular, and circular arrays consistently provide the most stable and accurate performance, with dispersion fitting errors generally below 0.5%, whereas the linear and random arrays show larger high-frequency deviations. The corresponding inversion models derived from the optimal arrays closely match the theoretical models, confirming that array geometry plays a critical controlling role in dispersion imaging quality and inversion reliability.

The field application on the Dongzhou Peninsula, Fujian Province, further validates the effectiveness of the proposed method. The inverted S-wave velocity structures obtained from three survey lines successfully delineate both the original and reclaimed coastlines, showing excellent agreement with known reclamation boundaries. Based on S-wave velocity classification, Vs < 400 m/s corresponds to reclaimed fill materials, 400–700 m/s to silty clay and fractured sediments, 700–900 m/s to moderately weathered bedrock, and Vs > 900 m/s to slightly weathered to fresh bedrock. The interpreted coastline positions achieve a meter-level spatial accuracy, demonstrating the method’s strong capability for detecting subtle subsurface transitions associated with coastal reclamation and nearshore sediment variability.

Overall, the proposed multi-station high-frequency microtremor surface-wave exploration method is explicitly recommended as a practical and reliable protocol for coastal engineering investigations, particularly for foundation condition assessment, weak-layer identification, and reclamation boundary delineation. Owing to its non-invasive nature, cost-effectiveness, high spatial resolution, and strong environmental adaptability, this method provides an efficient geophysical solution for coastal infrastructure planning, engineering safety evaluation, and nearshore geological characterization. The results highlight the significant potential of this technique for broader applications in coastal geology and marine engineering development.