1. Introduction

When a UUV performs global route planning in a high-dimensional environment, it faces issues such as long calculation times and a single optimization target, which limits its ability to efficiently find routes in large sea areas. Improving the computational efficiency of global route planning and balancing the navigation distance, planning efficiency, and the feasibility of planning under a multi-objective optimization framework are core issues addressed in this study.

Based on global route planning, the UUV needs to perform local collision avoidance in observable environments under conditions of sparse rewards. The current related collision avoidance algorithms still have deficiencies in terms of reliability, real-time performance, generalization ability, and learning sample utilization of collision avoidance planning. They are unable to make effective decisions for collision avoidance planning with multiple dynamic obstacles, making it difficult for UUVs to make effective decisions when dealing with dynamic obstacles and uncertain environments. How to build an efficient local collision avoidance strategy and improve real-time obstacle avoidance capabilities is a key challenge for UUV intelligent navigation technology.

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has powerful self-learning capabilities. It does not require accurate modeling of the obstacle environment in which the UUV operates, nor does it heavily rely on sensor accuracy. Huang et al. [

1] proposed the Double Deep Q Network (DQN) algorithm to optimize collision avoidance and navigation planning. The Double DQN algorithm decouples action selection and evaluation, obtaining the action index corresponding to the maximum Q value through the current network and inputting it into the target network to calculate the target Q value. The results show that overestimation is reduced, and the Double DQN algorithm can effectively process complex environmental information and perform optimal navigation planning. The application of value function DRL in autonomous collision avoidance has been confirmed in existing studies. Compared with value-based and model-free methods, policy gradient-based methods have great advantages in processing continuous actions. Xi [

2] proposed an end-to-end perception-planning-execution method based on a two-layer deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) algorithm to address the problems of sparse rewards, single strategies, and poor environmental adaptability in UUV local motion planning tasks, in order to overcome the challenges of end-to-end methods that directly output control force in terms of training and learning. Wu et al. [

3] proposed an end-to-end UUV motion framework based on the PPO algorithm. The framework directly takes raw sonar perception information as input and incorporates multiple objective factors, such as collision avoidance, collision, and speed, into the reward function. Experimental results show that the algorithm can enable a UUV to achieve effective collision avoidance in an unknown underwater environment full of obstacles. However, he did not consider the nonlinear characteristics of UUV kinematics and dynamics. To address this problem, Hou et al. [

4] designed a DDPG collision avoidance algorithm in which two neural networks control the thruster and rudder angle position of the UUV, respectively. The reward function considers the distance from the obstacle to the sonar, as well as the difference between the current position and the previous position to the target point. Simulation results show that the UUV can plan a collision-free path in an unknown continuous environment. Sun et al. [

5] demonstrated a collision avoidance planning method that integrates DDPG and Artificial Potential Field (APF), taking sensor information as input and outputting longitudinal velocity and bow angle. This method combines APF to design a reward function and uses a SumTree structure to store experience samples according to their importance, giving priority to extracting high-quality samples, and accelerating the convergence of the SumTree-DDPG algorithm. Li et al. [

6] introduced a goal-oriented post-experience replay method to address the inherent problem of sparse rewards in UUV local motion planning tasks. Simulation results show that this method effectively improves the stability of training and improves sample efficiency. In addition, an additional APF method dynamic collision avoidance emergency protection mechanism, is designed for UUV. The combination of DRL and APF has the potential to improve the performance of intelligent agents in complex environments, but DRL and APF are both reactive collision avoidance algorithms. If they are combined, the UUV decision-making and planning will conflict, and a coordination mechanism needs to be designed. Tang [

7] uses sonar data as the input of the network and uses the policy network output of the TD3 framework as the motion command of the UUV to complete the collision avoidance planning of the UUV in a 3D unknown environment. In the above papers, the interference of ocean currents is not considered, and the obstacles in the environment are regular. To address these problems, Huang [

8] proposed a UUV reactive collision avoidance controller based on the Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) method, and designed the state space, action space, and multi-objective function of reactive collision avoidance. The simulation results show that this method can realize collision avoidance planning in sparse 3D static and dynamic environments.

From the above research results, we know that there are a large number of scholars studying collision avoidance planners based on the DRL algorithm, but only a few papers are studying samples in the learning process. During the model training process, the blind exploration of the DRL algorithm generates a large number of low-quality samples, which will reduce the utilization rate of effective sample data, thereby greatly reducing the learning efficiency. In addition, there is little research on the stability and generalization of the training model. Therefore, this also provides research value and significance for the work of this paper.

UUV autonomous navigation planning is closely related to route tracking. Navigation planning is crucial for ensuring that UUVs provide safe routes and avoid obstacles during autonomous missions, while route tracking is the process of controlling and executing the UUV’s planned routes. The quality of navigation planning directly affects the executability of route tracking; that is, high-quality planned routes should have good command smoothness and eliminate chattering, which is conducive to UUV operation execution.

For 2D route tracking problems, line-of-sight (LOS) is a commonly used method that can be used to guide a UUV to track along a preset path. The LOS method calculates the LOS angle between the current position of the UUV and the target waypoint and generates corresponding heading instructions to gradually converge to the target path, thereby completing route tracking [

9]. Fossen and Pettersen et al. [

10] found the source of tracking error and proved the algorithm’s strong convergence and robustness to disturbances. Although the proportional LOS guidance method is effective and popular, significant tracking errors may occur during route tracking when the UUV is subjected to drift forces caused by ocean currents. To overcome this difficulty, researchers have completed a lot of work to mitigate the effects of sideslip. In reference [

11], accelerometers are used to measure longitudinal and lateral accelerations, and then the corresponding velocities are calculated by integrating these measurements. Reference [

12] proposed an integral LOS guidance method to achieve straight-line route tracking, which can avoid the risk of integrator saturation [

13]. Reference [

14] derived an improved integral LOS guidance method for tracking on curved paths. Reference [

15] proposed direct and indirect integral LOS guidance methods for ships exposed to time-varying ocean currents. The above references mitigate the effects of sideslip angle by adding integral terms to the LOS guidance method. Integral LOS can only handle constant sideslip angles. When following a curved path or time-varying ocean disturbances, the sideslip angle will also change due to the change in ocean current disturbances over time. Secondly, the stability is reduced due to the existence of phase lag superposition integral terms. Liu et al. [

16] used LOS based on an extended state observer [

17] for route tracking of underactuated vehicles when the sideslip angle changes over time. In the marine environment, the actual motion of a UUV is affected by complex nonlinear coupling relationships, involving multiple degrees of freedom and complex motion states. The LOS method has been widely used in two-dimensional route tracking, but there are still challenges in terms of time-varying ocean currents, sideslip angle changes, and 3D path planning. Research route tracking methods suitable for 3D environments to solve the path deviation problem caused by the nonlinear coupled motion of UUVs in 3D space, so as to improve the autonomous navigation capability of UUVs in complex marine environments.

When UUVs perform tasks in the ocean environment, they are inevitably affected by time-varying ocean currents and dynamic sideslip angles, which significantly increase the complexity of route tracking. Traditional guidance methods have poor tracking stability under time-varying flow field disturbances and environmental changes, making it difficult to achieve high-precision three-dimensional route tracking. How to improve navigation stability and autonomous control capabilities in a high-dimensional environment is an important direction that underwater autonomous navigation technology needs to break through.

The main contributions of this article can be summarized as follows:

The multi-level state perturbation guidance mechanism and the noisy network with multi-scale parameter noise fusion solve the training oscillation problem caused by fixed-scale noise, and the sampling number penalty term and stratified priority sampling strategy are used to improve learning efficiency and maintain the generalization ability of the DDPG model.

The horizontal and vertical front sight vectors are designed to decouple the control design of UUV nonlinear motion, and their stable convergence is proved by theory, which solves the problem that the integral LOS guidance method is difficult to directly track the three-dimensional planning waypoints under the condition of UUV attitude change caused by ocean current disturbance.

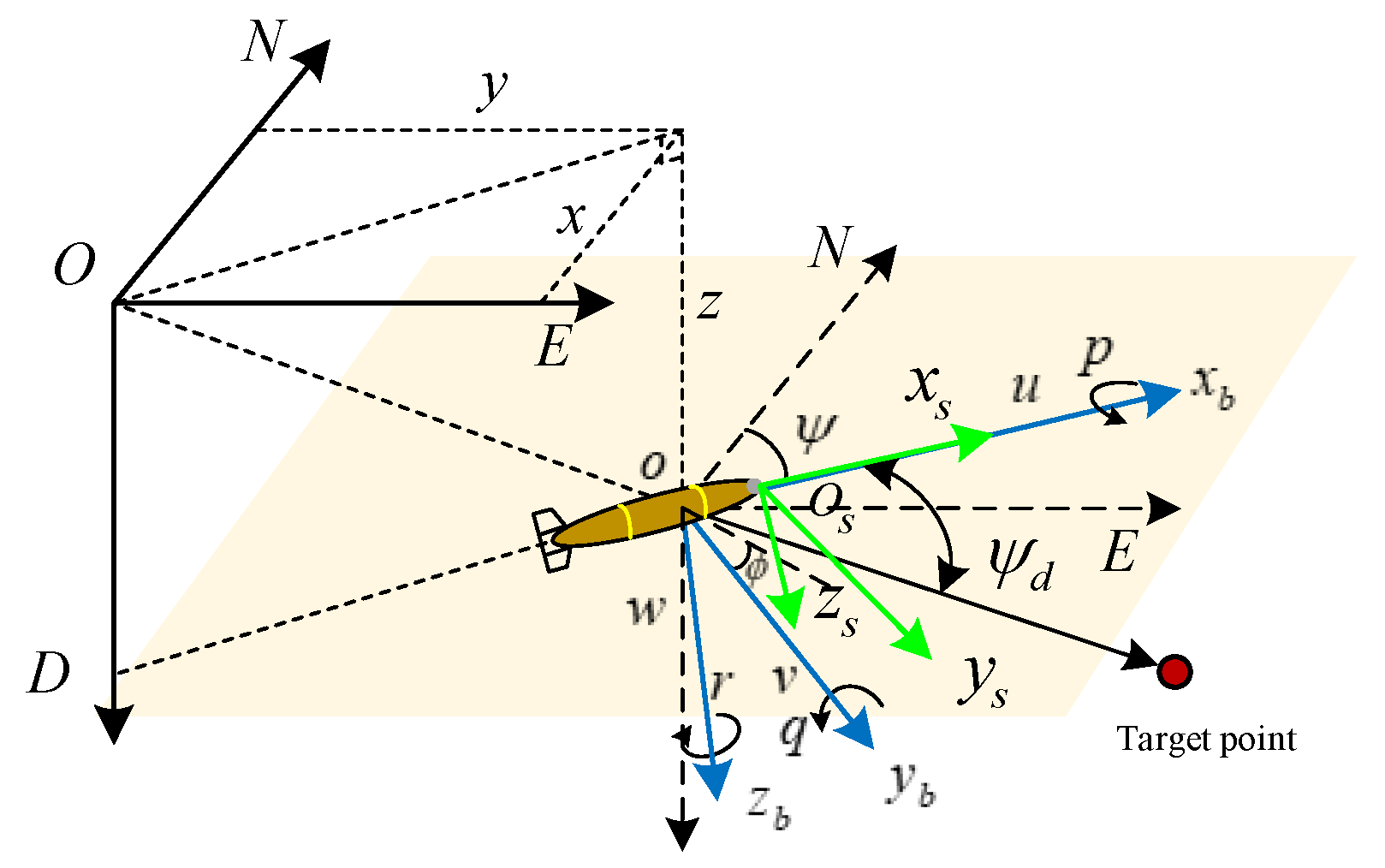

2. Construction of UUV Autonomous Navigation Planning Model

In order to analyze the problem of UUV underwater maneuvering motion control and obstacle detection model construction, the north–east–down (NED), UUV coordinate system, and forward-looking sonar coordinate system were established, as shown in

Figure 1.

,

, and

represent the displacement of the UUV relative to the three axes of the NED coordinate system. A vehicle coordinate system

fixed to the center of mass of the UUV was established to describe the translation and rotation of the UUV. Among them, the axis

is located in the longitudinal section of the UUV, pointing from the center of mass of the UUV to its bow direction; the

axis is perpendicular to the longitudinal section of the UUV, with the starboard direction of the UUV as the positive direction; the

axis is located in the longitudinal symmetry plane of the UUV, perpendicular to the

axis, and points to the bottom of the UUV.

Table 1 shows the UUV motion parameters.

2.1. Kinematic and Dynamic Model of 3-DOF UUV

Considering the 3-DOF underactuated UUV kinematic of

,

and

, spatial motions such as swaying, yawing, and pitching can be realized, providing a model simulation basis for the subsequent 3D route optimization of UUV autonomous navigation planning and the planned route tracking motion in 3D space [

18]:

The kinematics of the UUV should also satisfy the following constraints:

UUV 3-DOF dynamic model:

where

represents the UUV surge, pitch, and yaw.

Mass and added mass matrix

:

where

,

and

represent the equivalent additional inertia caused by the ocean current on the UUV’s motion along the three degrees of freedom of surge, pitch, and bow rotation, respectively, without considering the direct coupling of the 3-DOF in inertia.

Coriolis matrix

:

where

is the inertial force term caused by motion coupling. A simplified asymmetric structure is adopted, and only the bow rotation and pitch cross terms caused by the change in surge velocity are retained.

In the formula, , and represent the linear damping coefficients of the 3-DOF , and , respectively; , and represent the nonlinear damping coefficients of the corresponding degrees of freedom, respectively; , and take absolute values to reflect the physical property that nonlinear damping increases with increasing speed.

These control inputs are expressed in vector form as follows:

Among them, is the longitudinal thrust provided by the propeller, is the pitch moment provided by the horizontal rudder, and is the yaw turning moment provided by the rudder.

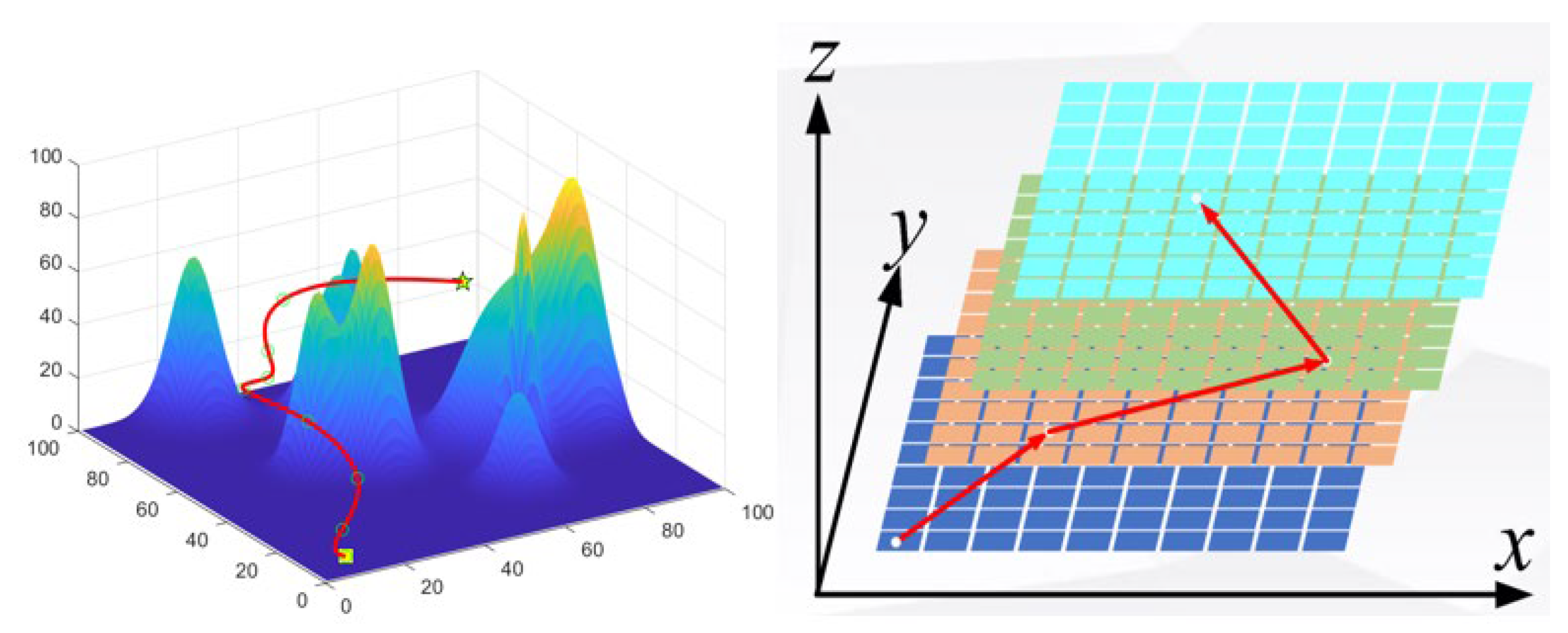

2.2. Three-Dimensional Global Environment Model

This study adopts a grid environment in the horizontal direction and discretizes the space in the vertical direction to form an environment representation suitable for navigation planning, as shown in

Figure 2.

is the coordinate of any point in 3D space, and the UUV planning space can be expressed as:

Among them, , , , , and are the value ranges of each dimension of UUV, respectively.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of 3D space and slices.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of 3D space and slices.

When the UUV moves to point

in 3D space, the altitude of the terrain corresponding to the UUV vertically is represented by

(

,

,

,

are all positive integers). The two-dimensional matrix

represents the environmental model of the UUV, and the index values

and

of

represent the maximum boundaries of the three-dimensional ocean environment in the north and east directions. Therefore, each element in the matrix represents the altitude of the vertical terrain corresponding to the point:

2.3. Time-Varying Ocean Current Disturbance Model

Assuming that in the NED coordinate system, the ocean current speed is

and the direction is

. The ocean current speed

changes dynamically according to the first-order lag system as follows:

where

is the current current speed;

is the target current speed;

is the simulation step size;

is the law of current speed change.

is the normal distribution noise with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

where

is the current direction;

is the target current direction; and

is the law of current direction change. Both

and

are exponentially smooth changes, reflecting the existence of certain inertia and disturbance in natural current changes. At the same time, weak Gaussian white noise disturbances are superimposed to simulate small-scale uncertainties in the real ocean environment.

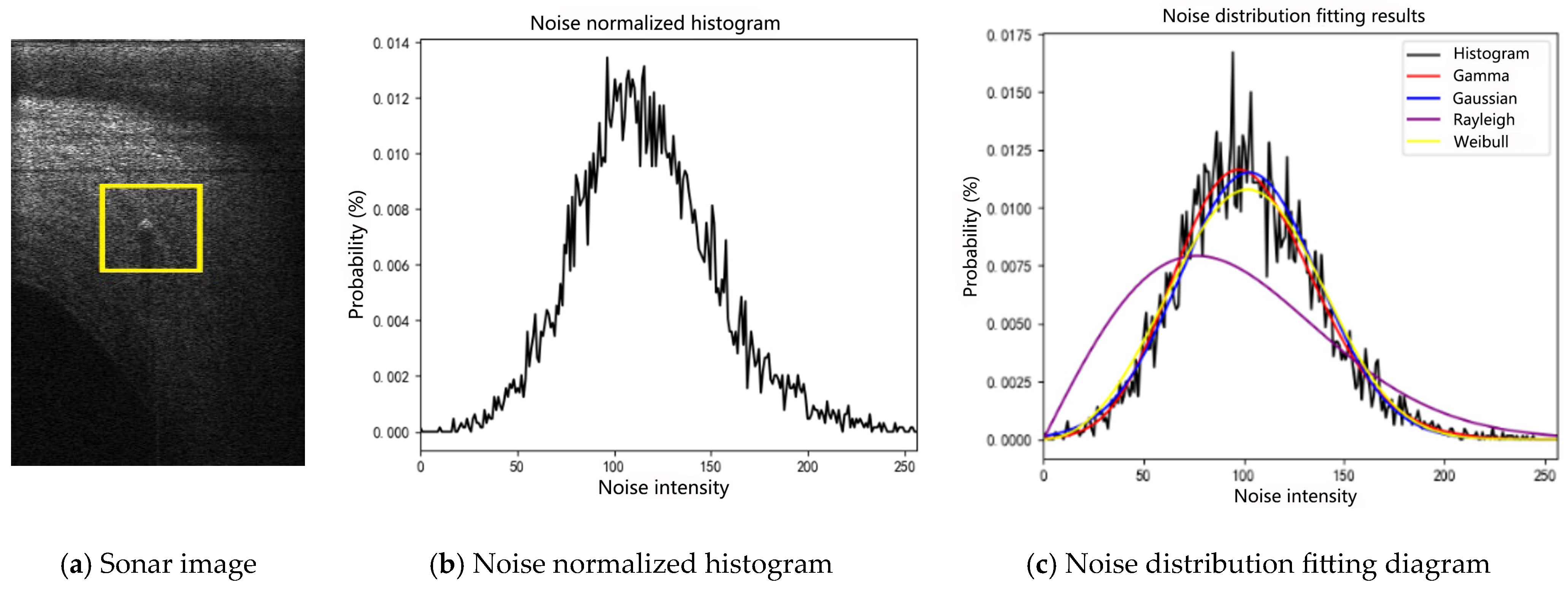

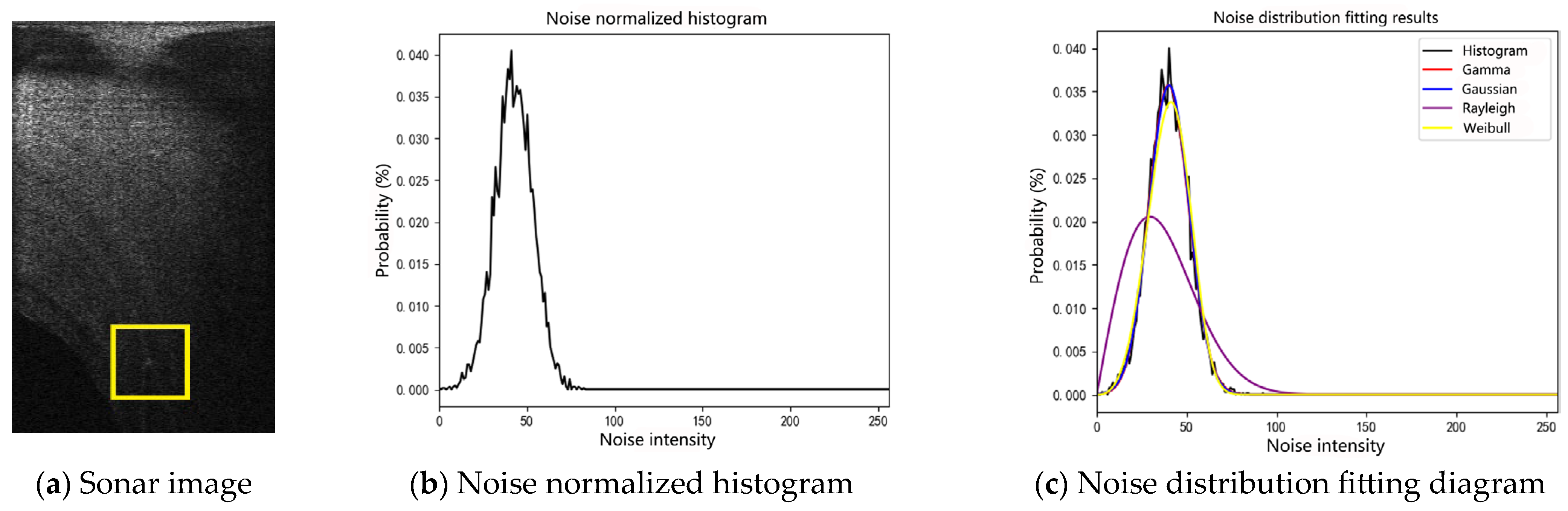

2.4. Noise Modeling and Characteristics Analysis of Forward-Looking Sonar Images

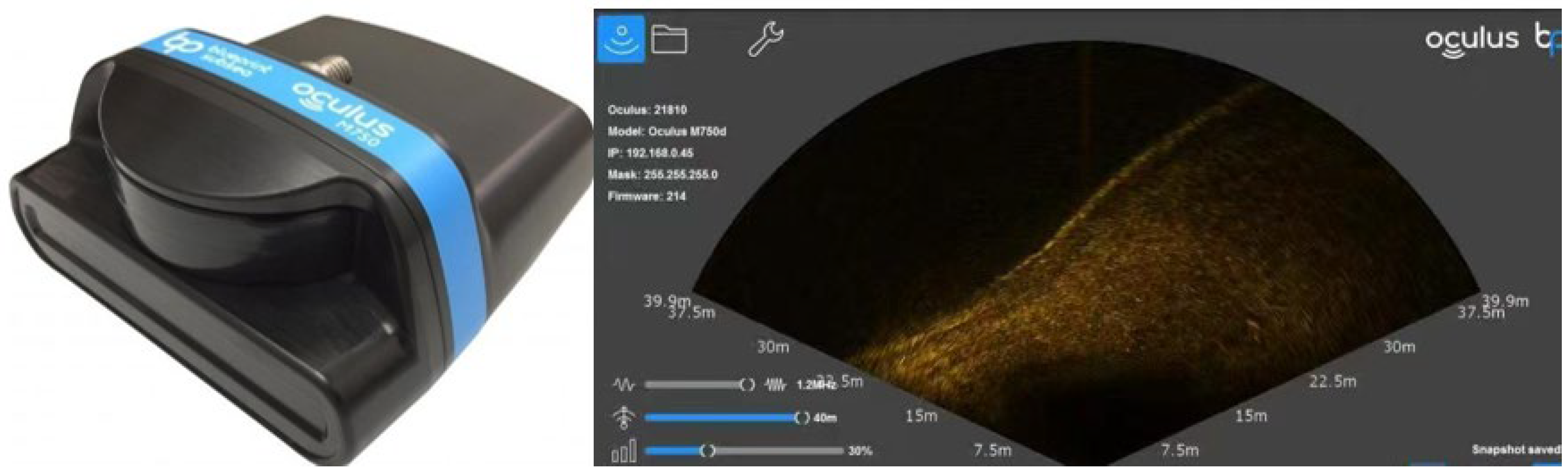

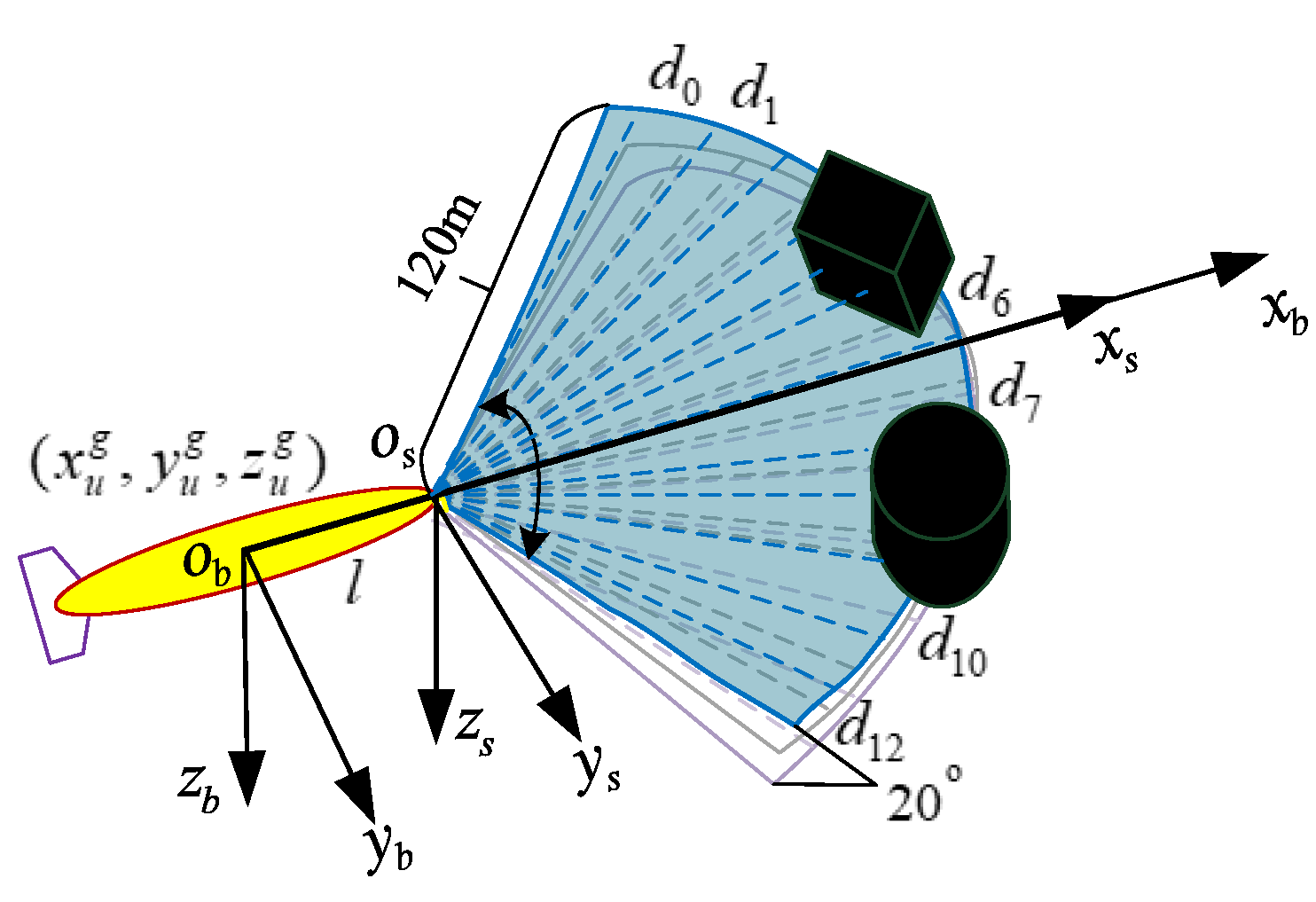

This paper uses the Oculus M750d multi-beam forward-looking sonar as a simulation detection prototype system, as shown in

Figure 3. Its horizontal detection angle is 130° fan-shaped area, vertical angle is 20°, maximum range is 120 m, effective range is 0.1 m–120 m, operating frequency is 750 kHz, and the maximum update rate is 27 Hz. Its distance resolution is 1° and contains 512 beams.

In order to improve the effectiveness of subsequent image enhancement and target detection algorithms, it is necessary to systematically model and analyze the sources, characteristics, and statistical properties of noise in sonar images, as shown in

Appendix A. Sonar image noise can be divided into three categories according to the noise source: self-noise, environmental noise and reverberation noise [

19].

A multi-beam forward-looking sonar simulation model was created to simulate the underwater obstacle perception scene. The sonar horizontal opening angle was divided into a cluster every 10 degrees, and the minimum value among the distance values of the upper, middle and lower layers was selected as the corresponding detection distance

of the sonar. The sonar measurement values of 512 beams were reduced to 13 dimensions

, as shown in

Figure 4.

In order to accurately measure the position of obstacles in the global NED coordinate system, the multi-beam forward-looking sonar obtains the obstacle distance and angle information, and converts it into the NED coordinate system through coordinate transformation:

where

is the coordinate of the obstacle in the NED coordinate system,

is the coordinate of the obstacle measurement information converted to the UUV carrier coordinate system,

is the coordinate of the UUV in the NED coordinate system,

represents the distance from the sonar to the center of mass of the UUV, and the origin of the sonar coordinate is on the

axis of the UUV.

3. Autonomous Collision Avoidance Planning Method for UUV Based on Target Information Driven DDPG

3.1. Deep Deterministic Policy Gradients

We consider an AUV that interacts with the environment in discrete time steps. At time the AUV takes an action according to the observation and receives a scalar reward (here, we assumed the environment is fully observed.) We model it as a Markov decision process with a state space , action space , state distribution , transition dynamics , and reward function . The sum of discounted future reward is defined as with a discounting factor . The AUV’s goal is to obtain a policy that maximizes the cumulative discounted reward . We denote the discounted state distribution for a policy as and the action-value function . The goal of UUV is to learn a series policy that maximizes the expected return .

We use an off-policy approach to learn a deterministic target policy H from the trajectories generated by the random behavior policy

. We average the state distribution of the behavior policy and transform the performance objective function into the value function of the target policy

:

The validity of (16) does not depend on , but it is approximated by a neural network. Replace the true value function with a differentiable value function in Formula (16) to derive an off-policy deterministic policy gradient update policy method. The Critic network estimates the true value from the trajectory generated by the policy using an appropriate policy evaluation algorithm. In the following off-policy DDPG algorithm, the Critic network uses Q-learning updates to estimate the action value function.

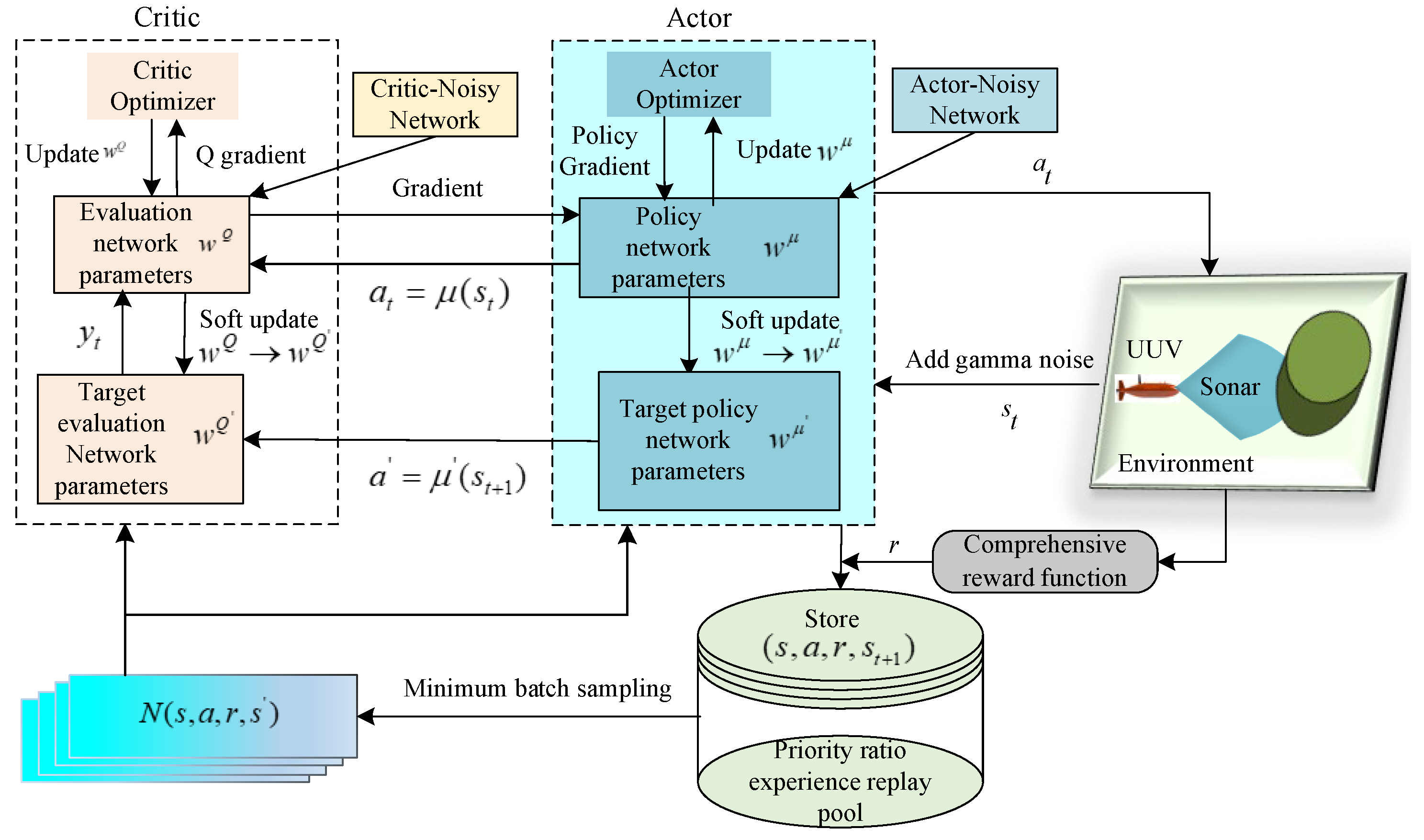

3.2. Target Information Driven DDPG Algorithm Framework

- (1)

State-space design with target information as input

In this paper, the Actor network input is expanded from a 14-dimensional vector to a 15-dimensional vector, which includes the processed sonar data , the distance between the current position of the UUV and the target point, and the deviation angle between the UUV heading and the target point at two moments. The Critic network is 17-dimensional. In addition to the above inputs, it also includes the UUV’s strategy at the previous moment (including longitudinal accelerations and yaw angular velocity), which are normalized and used as the input of the network. Not only is the orientation information of the target point added, but also the strategy of the previous moment is introduced to reduce the probability of blind learning of the UUV in the case of sparse rewards, and make the UUV’s movement smoother.

- (2)

Continuous action space design

DRL methods usually participate in exploration behavior by injecting noise into the action space. Adding noise to the action space is a common method to improve the performance of Dueling DQN. In the Q learning process, by applying the strategy, a certain proportion of random actions will be added when selecting actions. Different from the previous chapter, in this chapter, the continuous state quantities of the longitudinal acceleration and bow angular velocity of the UUV are used as the output strategy, and a noise network is used instead of adding noise to the strategy to improve the stability and generalization of the model.

- (3)

DDPG network framework driven by target information

The improved DDPG algorithm network framework is shown in

Figure 5. The algorithm obtains training data from the sample pool through the experience replay mechanism and uses the Critic network to calculate the Q value gradient information to guide the Actor network update, thereby continuously optimizing the policy network parameters. Compared with the DQN algorithm based on the value function, the DDPG algorithm shows higher stability in tasks in the continuous action space, higher policy optimization efficiency, and faster convergence speed, and the number of training steps required to reach the optimal solution is also significantly reduced. The network update in this paper uses the average reward of the round to eliminate the impact of the difference in the number of rounds on the evaluation results, making the evaluation results more stable and improving the stability of the model.

- (4)

Comprehensive reward function

This paper defines a comprehensive reward function based on the environment in which the UUV is located. The comprehensive reward function designed in this section is expressed as four dynamic reward items:

where

represents the distance penalty factor, which is a negative number;

is the distance between the UUV and the target point at time

, and

is the distance between the starting point and the target point.

where

is the distance between the UUV and the obstacle,

is the maximum detection distance of the sonar, and

is the angle between the UUV heading and the obstacle. If the UUV hits an obstacle or a boundary, then

; if the UUV reaches the target point, then

.

The comprehensive reward function of this paper is the sum of

,

,

,

:

3.3. Design of DDPG Method with Noisy Network

DDPG uses a deterministic strategy. For complex environments in continuous space, it is often difficult to conduct sufficiently effective global exploration by only adding Gaussian noise or OU noise for exploration. Once it falls into a local optimum, it may lack higher-dimensional randomness to jump out of the local extreme point.

In DDPG, the policy network outputs continuous action values, and the square error

can be used directly to measure the difference between the output actions of two policies:

In the DDPG algorithm implementation,

is used as the perturbation of the strategy, and the perturbation strategy distribution also obeys

. Set the adaptive scaling factor to

and construct a single linear unit of the noise network:

where

,

,

,

. The idea of the noise network is to regard the parameter

as a distribution rather than a series of values. The resampling method is used for

. First, a noise

is sampled, and the following is obtained:

At this time, the parameter

needs to learn the mean and variance. Compared with DDPG, the parameters that need to be learned become twice as many as the original. Similarly, the bias becomes

, and the resulting linear unit becomes:

Here we take the standard DQN,

as an example, and replace the Q network weight

with the noisy weight parameters

,

,

, replace

with

,

,

.Get the DQN with noisy network:

TD loss function

:

The training method of the noisy network is exactly the same as that of the standard neural network. Both use backpropagation to calculate the gradient and then use the gradient to update the neural parameters. The chain rule can be used to calculate the gradient of the loss function with respect to the parameters:

In order to further improve the robustness, strategy generalization ability and training stability of UUV’s autonomous collision avoidance in complex dynamic ocean environments, this paper proposes an improved noise network mechanism based on the introduction of noise network in the original DDPG structure, combined with a GRU module, which systematically improves the responsiveness of the collision avoidance strategy to dynamic changes in the environment.

- (1)

Design of multi-level state disturbance guidance mechanism

Different from the traditional noise network method that introduces fixed distributed disturbances at the parameter layer, this study constructs a state disturbance guidance network, which uses the temporal dynamic change in the current observation state to adjust the noise intensity and realize adaptive exploration driven by environmental uncertainty perception. Construct the disturbance weight function

:

In the formula, is the initial disturbance intensity; is the adjustment coefficient; and is the variance of the state change in the -step time window. The parameter noise amplitude in the Actor network is dynamically adjusted according to the disturbance weight to achieve the state perception ability of more aggressive strategy exploration when the environment changes more drastically.

- (2)

Multi-scale parameter noise fusion structure

In order to avoid the training oscillation problem caused by fixed-scale noise, a multi-scale noise fusion module is designed to introduce independent noise of different scales into each actor and critic hidden layer to form an inter-layer noise regularized gradient flow. The hidden state is extracted by GRU and sent to the noise fusion network to improve the memory of historical decision trajectories and cope with dynamic obstacle strategy patterns. Gaussian noise

of different scales is embedded in each layer and flexibly fused:

where

represents the Gaussian noise introduced by the

layer;

represents the learnable noise fusion coefficient of the

layer;

and

represent the weight and bias of the

layer;

represents the original forward feature of the

layer; and

represents the output feature after fusion of the noise.

3.4. Design of Experience Pool Sample Sorting Method Based on Proportional Priority

In order to improve the utilization efficiency of training samples and the speed of strategy convergence, a prioritized experience replay (PPER) mechanism based on temporal difference error (TD error) is introduced. This mechanism quantifies the contribution of each experience to learning, uses TD error as a metric for experience priority, and prioritizes sampling of high TD error samples for training, thereby improving the use value and learning efficiency of samples.

However, although traditional PPER improves sample utilization, it also faces the following problems: ① Scanning the entire experience pool at a high frequency to update the priority increases the computational time; ② It is sensitive to random reward signals or function approximation errors, which can easily introduce training instability; ③ Excessive concentration on a few high TD error samples may cause the strategy to fall into local optimality or even overfitting, reducing the generalization ability of the model [

20].

- (1)

Introducing the Sampling Times Penalty

In order to solve the above problems, this paper introduces a sampling number penalty term, which is between pure greedy priority and uniform random sampling. The

th sampling probability

of the transition state is defined as:

Among them, represents the priority of the experience, expressed as TD error; the exponent determines the priority, corresponds to uniform sampling; is used to ensure that each experience has a certain priority, and is a very small number; represents the number of times the experience is sampled; controls the penalty intensity of the sampling frequency, which is often takes in the range of (0.4~0.6). This mechanism measures the importance of each experience based on its TD error and uses it as the basis for the sampling probability. The larger the TD error, the more valuable the experience is to the current strategy optimization, and therefore, the higher the probability of being sampled.

- (2)

Stratified Prioritized Sampling

In the process of UUV collision avoidance planning model training, due to the large number of samples, the model is prone to overfitting risks. In addition, there are common problems in the UUV environment, such as sparse reward signals and drastic changes in the UUV bow angle. The traditional experience replay mechanism is difficult to effectively improve learning efficiency and maintain the generalization ability of the model.

To alleviate the above problems, the samples in the experience pool are divided into several priority intervals (divided into five levels according to percentiles) according to their TD error size, and random sampling is performed in each interval according to the set sampling weight. This strategy ensures that high-error samples are sampled first while avoiding excessive concentration of samples in intervals with large TD errors, thereby reducing the risk of the model falling into local optimality or overfitting, and enhancing sample diversity and overall training stability.

This paper proposes a DDPG collision avoidance planning algorithm based on sampling number penalty and stratified sampling strategy to improve priority experience replay, namely, proportional priority experience replay.

This form is more robust to outliers, and the Algorithm 1 pseudo-code is as follows:

| Algorithm 1. DDPG Algorithm with TD Error Ratio Priority Experience Replay |

Input: Minimum batch , step length , experience cycle and size , importance index , , total time .

Initialize experience pool , ,

Select according to the state quantity

for

Obtain the observation from the environment and save the state transition

tuple in the experience pool with the largest state priority .

if mod then

for to do

Sampling state transitions from the experience pool

Calculating sampling importance weights .

Calculating TD Error

Update state transition importance probability

Cumulative weight change

end for

Update network weights , Reset

Copy the weights to the Q target network after a period of time

end if

Select action

end for |

3.5. Simulation Verification and Analysis

This paper compares the path planning effects of DQN, Dueling DQN, DDPG, SAC, and the proposed algorithm in static obstacle environments. The evaluation indicators include average path length and planning stability. The DDPG algorithm training parameters are shown in

Table 2.

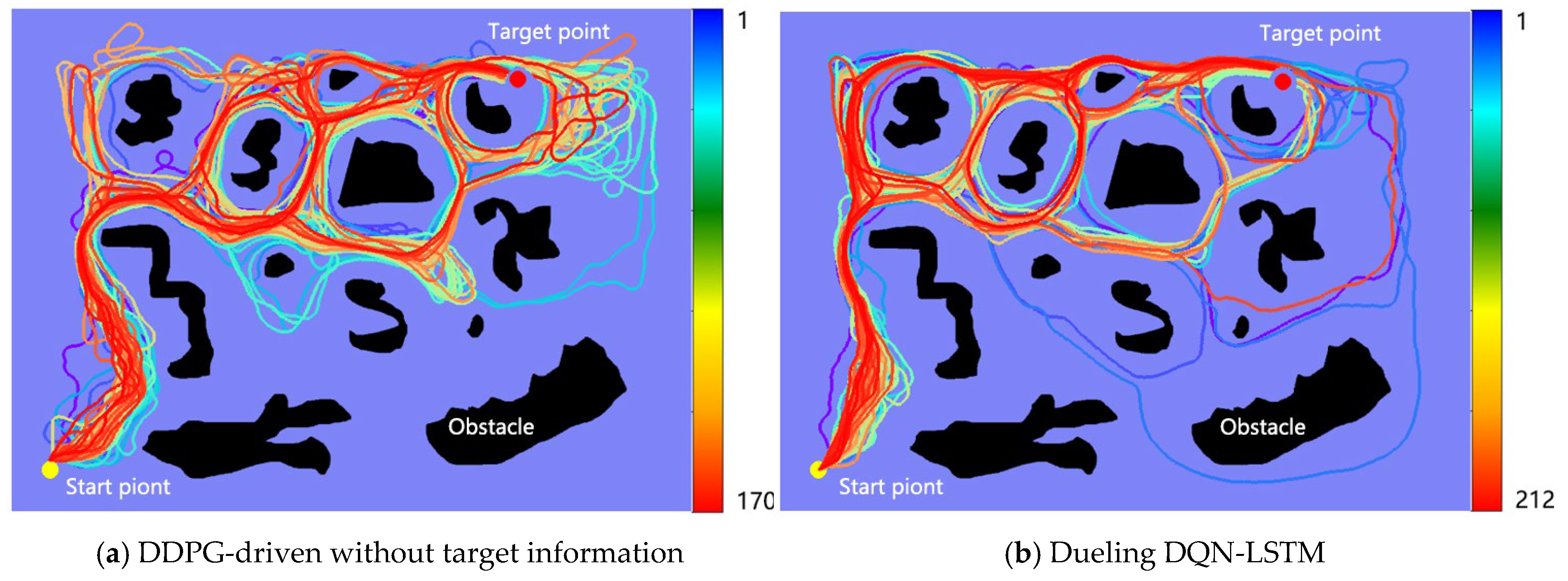

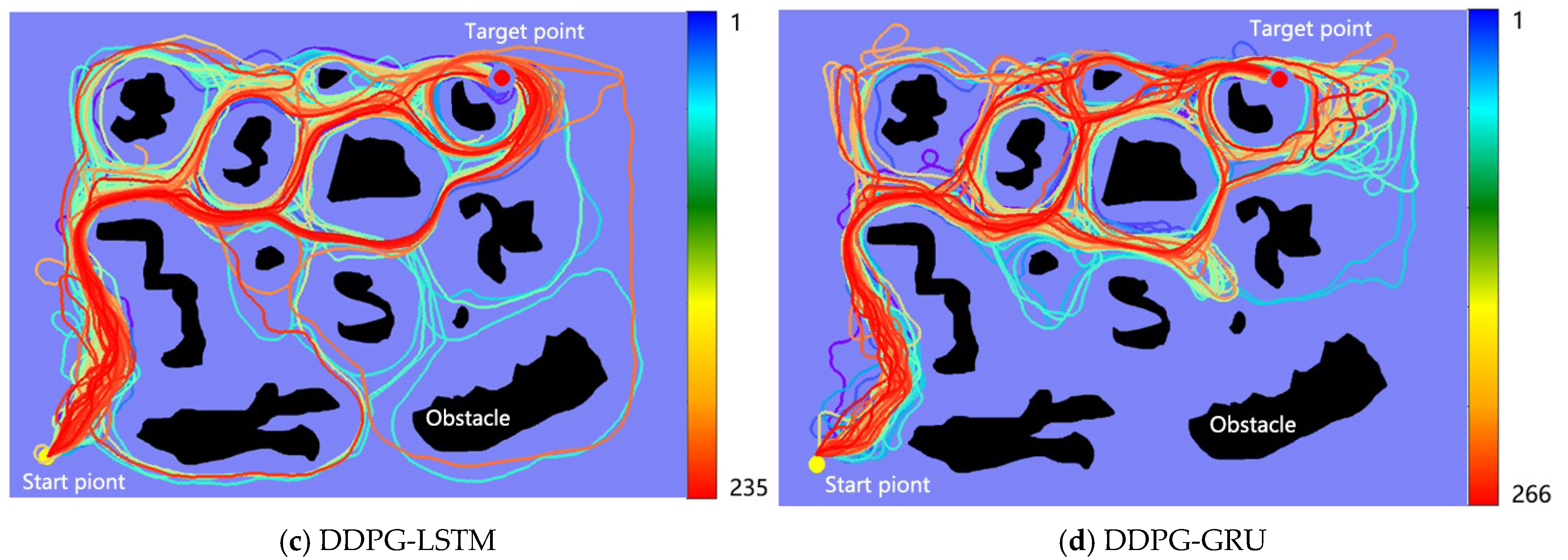

Figure 6 shows the environment obstacles constructed using a randomly generated method. Each collision avoidance planning algorithm was trained for 300 rounds. As shown in the figure, the UUV’s start point is located at [50 m, 45 m] and the target point is located at [520 m, 585 m]. The shortest distance between the two points is 715.9 m. The DDPG (no target information driven) algorithm uses a fully connected neural network. A comparison of

Figure 6a,d shows that without proper target information driving the strategy, effective convergence is difficult. Once the target location or corresponding reward mechanism is clearly defined in DDPG, combined with a recurrent neural network to memorize historical states, navigation efficiency will be significantly improved.

Table 3 shows that DDPG methods using either LSTM or GRU outperform the DDPG collision avoidance planning algorithm without target information in terms of training time, number of early rounds to reach the target, and number of path steps. DDPG-GRU performs best, achieving the best results in all four metrics: shortest training time, earliest target arrival, shortest path, and best success rate. This demonstrates that GRU is more effective in processing time series data for this task. DDPG without target information significantly lags behind in both convergence speed and path efficiency, demonstrating that incorporating target information and leveraging historical state memory are crucial for improving policy learning in complex environments.

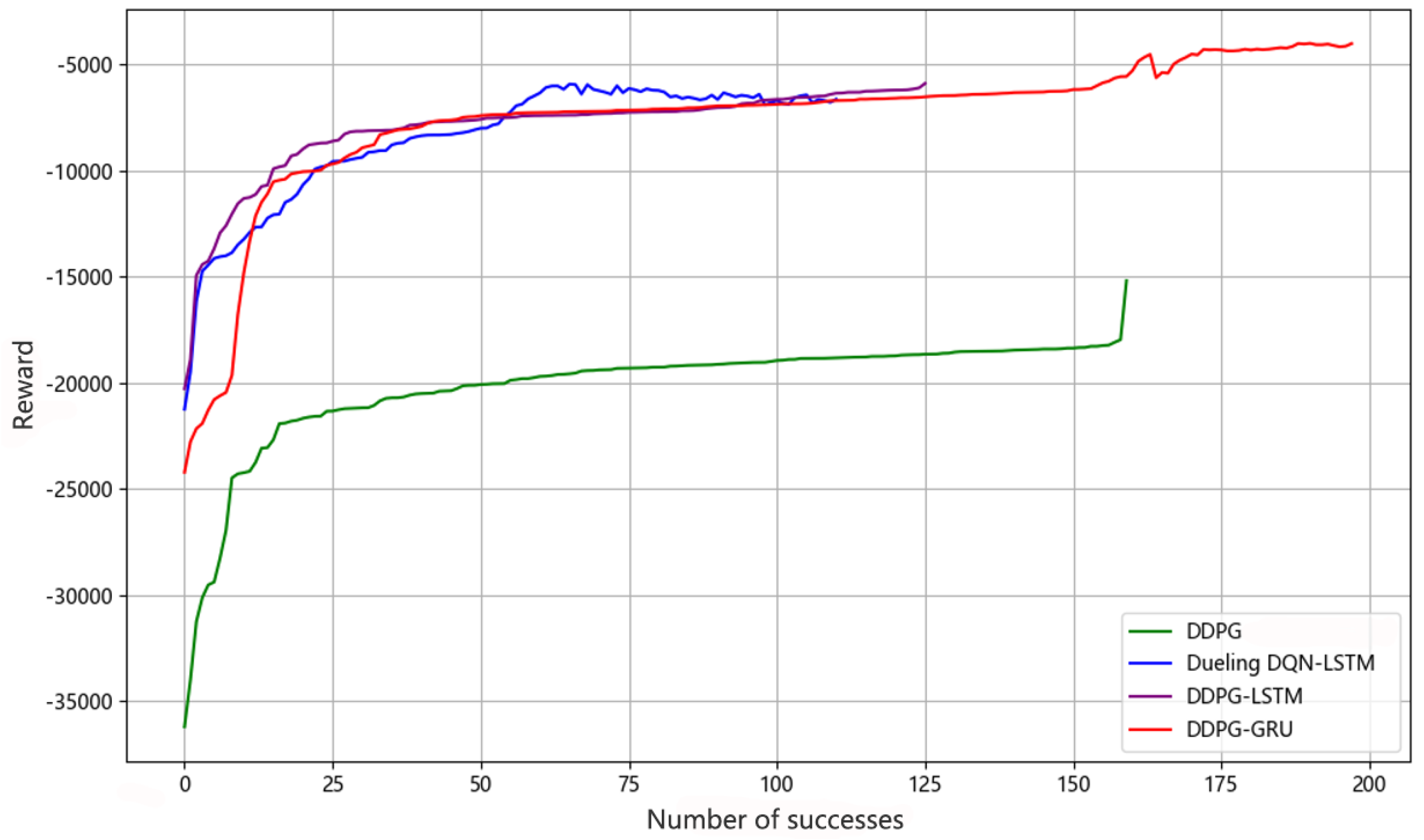

Figure 7 shows that after each algorithm successfully reaches the target for the first time, the reward value rises rapidly, indicating a significant improvement in policy performance. The cumulative returns of all algorithms gradually increase, reflecting the continuous exploration and optimization of the policy. The DDPG-target-free algorithm only incorporates obstacle distance information and lacks target information. In contrast, the algorithm with a memory-enhanced contextual value network and target information achieves higher cumulative returns, demonstrating that historical state and target information are crucial for the UUV collision avoidance model. Although Dueling DQN-LSTM reduces Q-value overestimation, its final performance is less stable than the DDPG-LSTM and DDPG-GRU algorithms, and its success rate is lower.

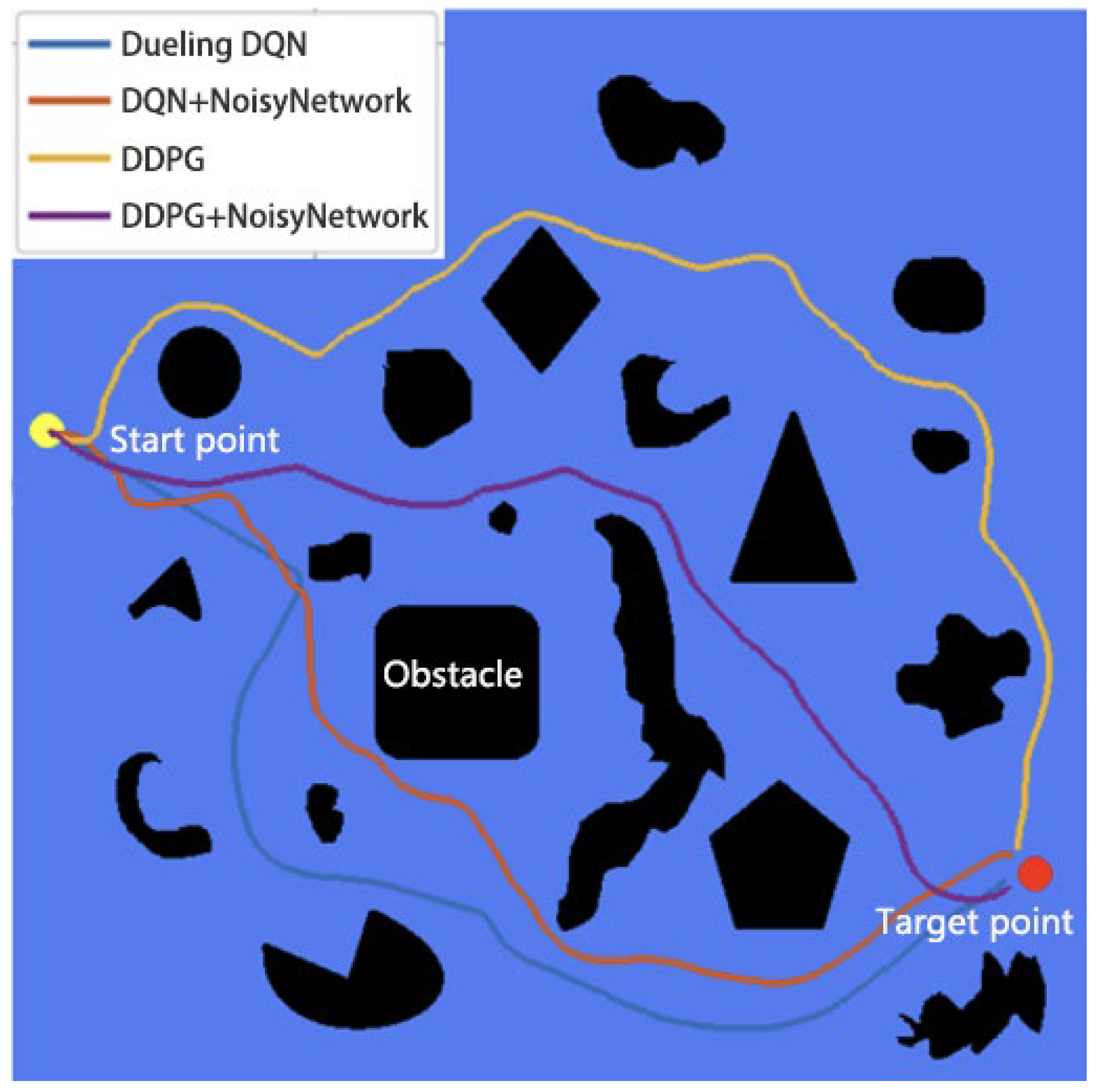

The effect of the noise network on the algorithm is verified in the environment of

Figure 8. The UUV start point (yellow circle) is located at [380 m, 20 m], and the target point (red circle) is located at [135 m, 575 m]. The straight-line distance between the two points is 606.7 m.

Table 4 shows that all collision avoidance algorithms can avoid dense static obstacles. The DDPG algorithm has the longest path, while the DDPG + Noise Network algorithm has the shortest path. The DDPG + Noise Network algorithm has the smallest cumulative heading adjustment angle, resulting in the smoothest path. Compared to the Dueling DQN, DQN + Noise Network, and DDPG algorithms, the cumulative adjustment angle is reduced by 63.0%, 63.2%, and 40.3%, respectively.

Adding noise to the network weights to achieve parameter noise allows the UUV to produce richer behavioral performance. Adding regularized noise to each layer can increase the stability of training, but it may cause changes in the distribution of activation values of the previous and next layers. Although methods such as evolutionary strategies use parameter perturbations, they lose temporal structure information during training and require more learning samples. In this chapter, the same noise is added to each layer, but the noise between layers does not affect each other.

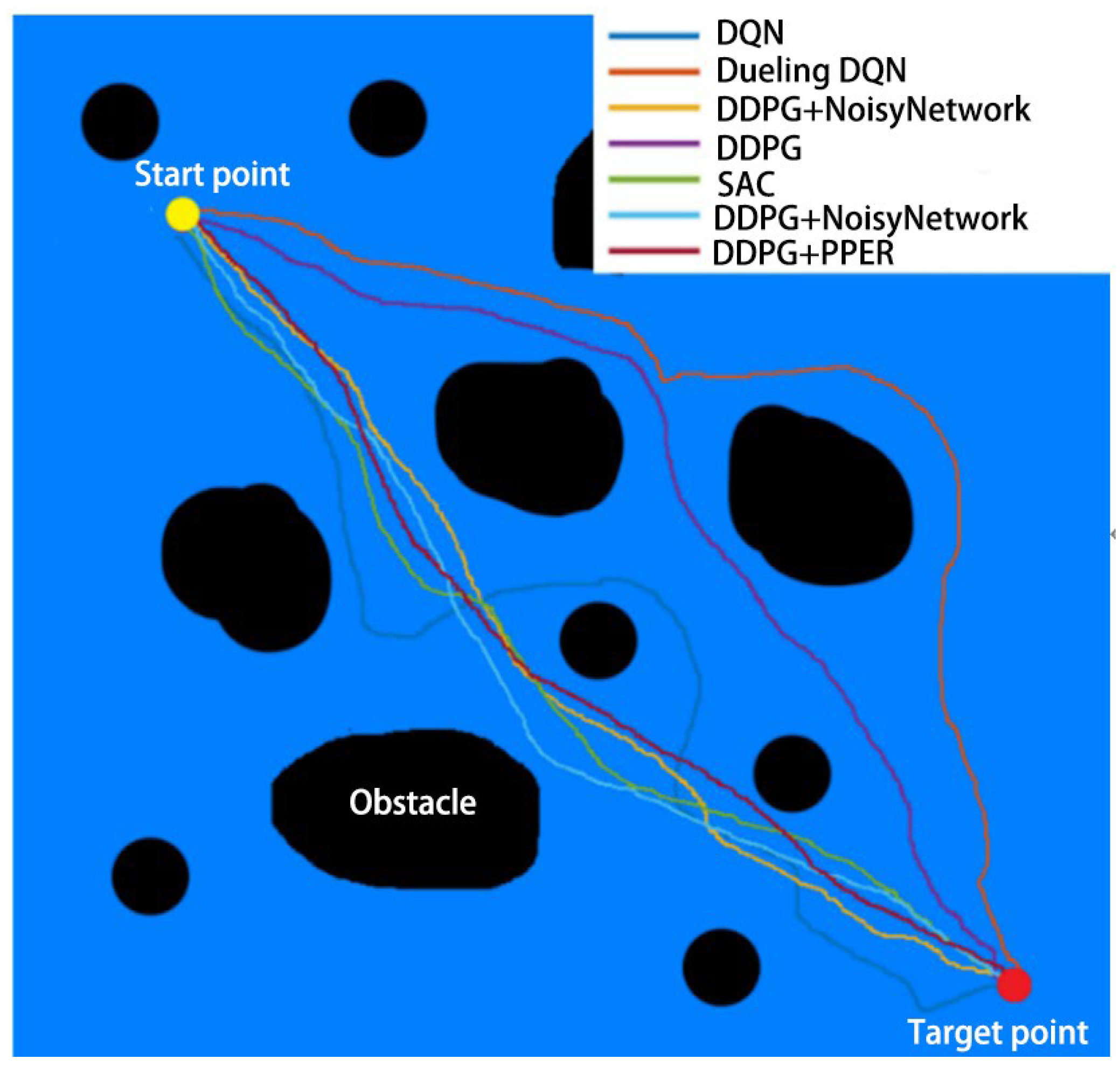

Figure 9 is a test of the performance of different DRL algorithms in a static environment. The positions of the starting point and the target point remain unchanged. The size and distribution range of each obstacle are randomly generated. Each algorithm is run 100 times (only one round is shown in the figure).

As can be seen from the data in

Table 5, the traditional DQN based on a discrete action space and its improved Dueling DQN algorithm performed poorly in terms of average path length and standard deviation, reaching 1494.0 m, 45.5 m and 1451.0 m, 42.0 m, respectively, indicating that they have problems of large path volatility and insufficient strategy accuracy in complex dynamic environments. In comparison, the DDPG series of algorithms using continuous action space modeling has better overall performance. Among them, although the original DDPG algorithm is slightly inferior to some of the comparison algorithms (1452.7 m) in average path length, its standard deviation is only 24.1 m, showing strong path stability.

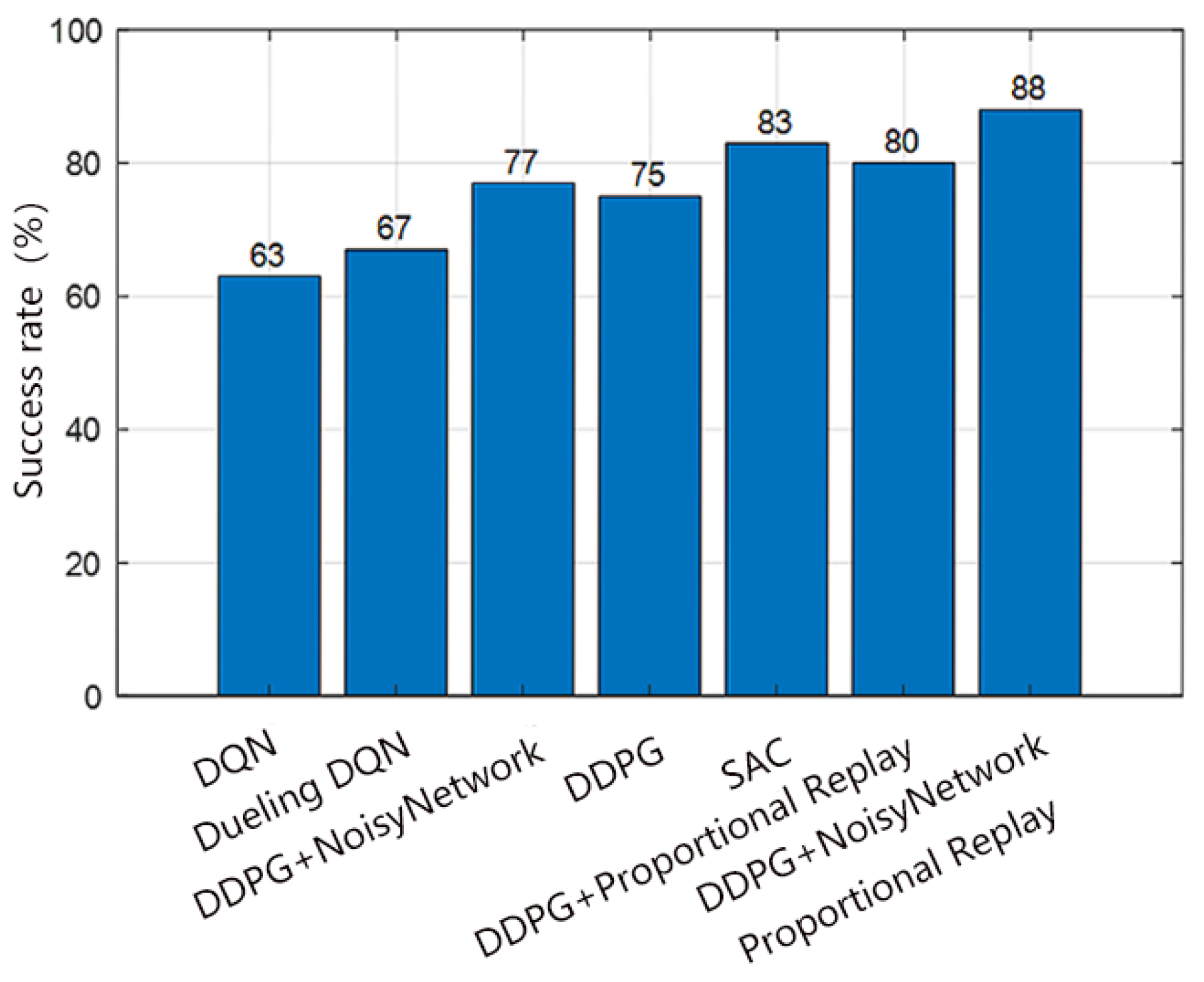

In

Figure 10, the DQN algorithm has the lowest success rate, and the SAC algorithm has a higher success rate than the DDPG algorithm that has only one improvement method; the success rate of the DDPG algorithm with a noisy network is 14%, 11%, and 2% higher than that of DQN, Dueling DQN, and the DDPG algorithm without a noisy network, respectively, indicating the effectiveness of the noisy network; the success rate of the DDPG algorithm with a noisy network and proportional priority experience replay is 25%, 21%, and 5% higher than that of DQN, Dueling DQN, and SAC algorithms, respectively, indicating that the introduction of a noisy network and proportional priority experience replay greatly improves the performance of the DDPG algorithm.

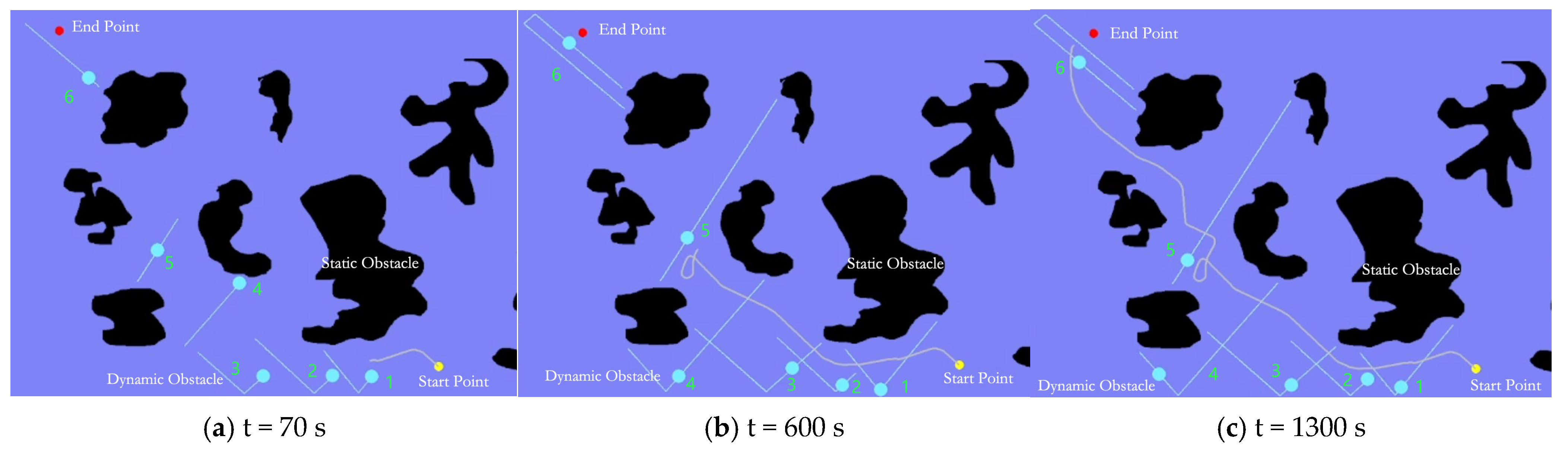

The complex simulation environment in

Figure 11 contains seven irregular static obstacles of unknown islands and six dynamic obstacles. The UUV starting point (yellow circle) is located at [70 m, 990 m], the target point (red circle) is located at [800 m, 135 m], and the shortest distance between the two points is 1124.4 m. The speed of each dynamic obstacle is randomly generated between 1 m/s and 2 m/s, and its direction of movement is also randomly generated.

Figure 11 shows that the UUV adopted a safe collision avoidance strategy based on the DDPG + NoiseNetwork + PPER algorithm at three different times, avoiding the risk of collision between the UUV and different obstacles. At t = 460 s, the UUV is about to meet the dynamic obstacle 5 moving to the lower left. In order to avoid the collision, the UUV deflects to the left and moves in the same direction as the obstacle, and then the two move to the upper left together. When t = 600 s, after the obstacle avoidance action is completed, the UUV quickly adjusts its heading and moves towards the target point again. This shows that the proposed improved DDPG algorithm can perceive the movement of obstacles in real time in a complex dynamic environment and make smooth and coherent collision avoidance decisions.

In summary, the DDPG + NoisyNetwork + PPER model proposed in this paper has become the most advantageous path planning strategy at present with the comprehensive performance of shortest path length and smallest fluctuation. This method significantly improves stability while ensuring the efficiency of UUV path.

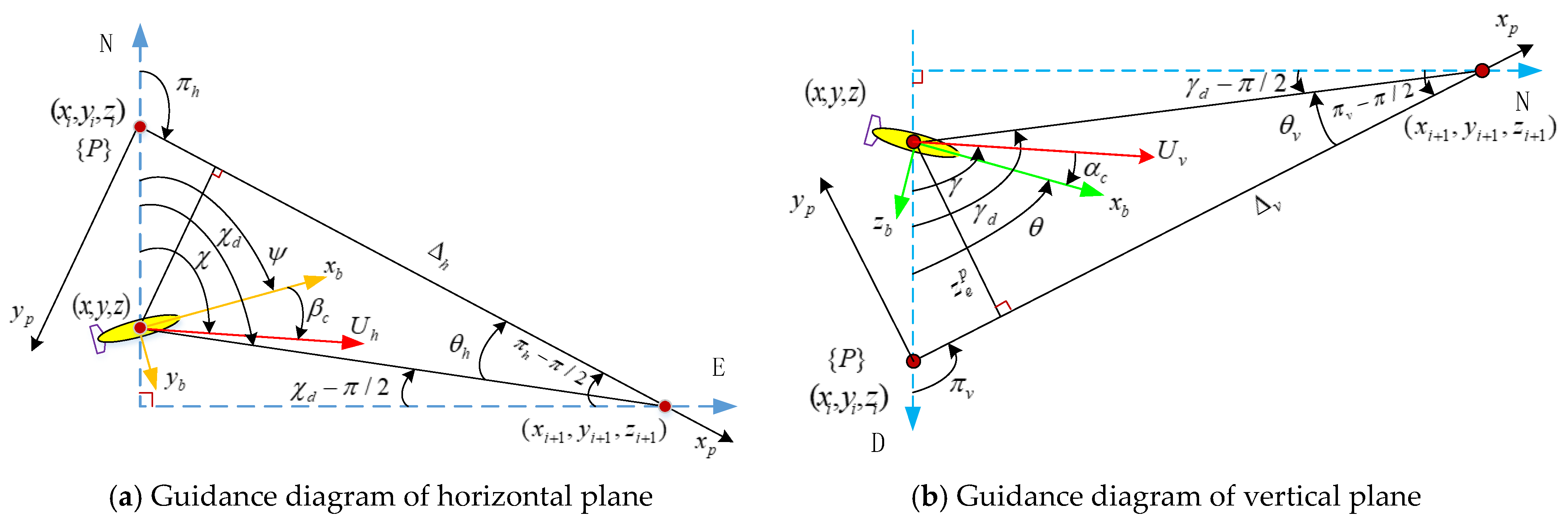

4. Comprehensive Simulation Verification of UUV Planning, Route Tracking and Autonomous Navigation

In order to achieve seamless connection from route planning to execution, UUV needs to have route tracking capability to ensure that it can accurately navigate along the planned route. In complex flow fields, UUVs cause dynamic sideslip angles due to factors such as hydrodynamic nonlinearity, asymmetric flow disturbances, control lag and incomplete observation. Its unpredictability and control limitations make it difficult to completely eliminate it, which seriously affects the path tracking accuracy and navigation stability. To address this problem, this paper constructs horizontal and vertical front sight vectors, and on this basis proposes a 3D adaptive line-of-sight (ALOS) guidance algorithm to ensure the feasibility of the 3D navigation planning results of UUVs. The simulation verifies the effectiveness of the UUV kinematic model in tracking the planned route under current disturbances, ensuring the feasibility of the UUV collision avoidance planning results.

4.1. Design of 3D ALOS Guidance Method Based on Horizontal and Vertical Front Sight Vectors

As shown in

Figure 12, a third coordinate system {P} is introduced when implementing three-dimensional planning route tracking. The axis of the coordinate system {P} is parallel to the introduced path. In the figure,

and

are two waypoints

and

output by the UUV collision avoidance planning in the NED coordinate system. The origin of the tangential coordinate system {P} of the current path is located at

, and its horizontal axis points to the next waypoint

.

is the angle of rotation of the UUV’s NED tracking error around the Z axis, and

is the angle of rotation of the UUV around the Y axis.

According to the conversion relationship between the coordinate system in

Section 2 and the {P} coordinate system, the longitudinal–lateral–vertical tracking error of the UUV in the {P} coordinate system is obtained:

For a surge velocity of

, the differential equation of motion for the rate of change in position of the UUV in the NED coordinates is expressed as:

where

,

,

and

are the velocity components in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, and are given by:

Desired heading and pitch angles:

Under the influence of ocean current disturbance, the UUV’s longitudinal velocity, sway velocity, and bow angle will change due to external environmental interference, and the phase angles and will also change accordingly, which will cause the horizontal front sight component and the vertical front sight component determined by Formulas (40) and (41) to also change. In order to simplify the complexity of tracking, the concept of relative velocity is used to simulate ocean current disturbance. In the process of straight-line path tracking, the following assumptions are made:

Assumption 1. During the path following process, andare fixed values, that isand.

The assumption is satisfied when the UUV follows a straight path at a constant speed and is considered to meet the assumption even if there is a slight speed change under time-varying environmental disturbances.

The tracking error differential equations along three directions are:

Expanding the last two lines of the above equation corresponds to the lateral and vertical tracking errors:

Rewrite the vertical path differential Formula (46) into a function form of P to realize the design of the depth controller. Substitute Formula (41) into Formula (46) to obtain:

Using the trigonometric transformation equation of the sum and difference angles, we can obtain:

Guidance rate ALOS for 3D path following:

For Formulas (45) and (48), the motion of the horizontal and vertical planes is decoupled.

and

are the self-specified forward distances, and

,

are the adaptive gain.

,

is the estimated value of

,

, respectively. The stability analysis assumes that the UUV can obtain perfect path tracking

and

by turning the heading and the deep autopilot. The parameter mapping method is used to enhance the robustness of the ALOS guidance rate:

The parameter estimates are compact sets

,

,

,

is a very small positive number, making

true,

where

is a special form of parameter mapping, which is modified to ensure semi-global stability.

where

,

.

Using the trigonometric transformation equations of sum and difference angles:

Using

and

, the above equation is transformed into a nonlinear cascade system:

From Assumption 1, we can see that , , , , are time-varying, and the and subsystems are non-autonomous systems. In some cases, it is advantageous to make the look-ahead distances , also time-varying. Assumption 1 is valid, and the stability of the cascade c and v is guaranteed by Lemmas 1, 2, and Theorem 1.

Lemma 1. If the perturbation is of initial value , then the cascade system is uniformly semiglobal exponentially stable.

Lemma 2. If the initial value , then the cascade system is uniform semiglobal exponential stable (USGES).

Theorem 1. Consider a three-dimensional path-following system for a UUV guided by the adaptive line-of-sight (ALOS) method. The system dynamics are decoupled into a horizontal guidance subsystem and a vertical guidance subsystem as follows:

where

are control gains;

,

are bounded external disturbances satisfying

;

is a continuous function that satisfies the Lipschitz condition:

for some

.

Then, under suitable selection of and , the origin of the cascaded system is Uniformly Semiglobally Exponentially Stable (USGES) with respect to bounded disturbances.

Proof. - (1)

Lyapunov Stability of the Horizontal Subsystem

Define the Lyapunov function candidate:

Taking the derivative along the trajectory of the system yields:

Therefore, the subsystem is input-to-state stable (ISS) and exponentially stable when .

- (2)

Lyapunov Stability of the Vertical Subsystem

Using the Lipschitz condition and Young’s inequality:

Similarly,

,

, thus:

Let

,

be chosen such that:

Then:

with

,

.

- (3)

Composite Lyapunov Function

Define the total Lyapunov function:

If the gains , are selected so that , the system satisfies “limited input disturbance and exponential convergence of state”, that is, it satisfies the USGES condition. □

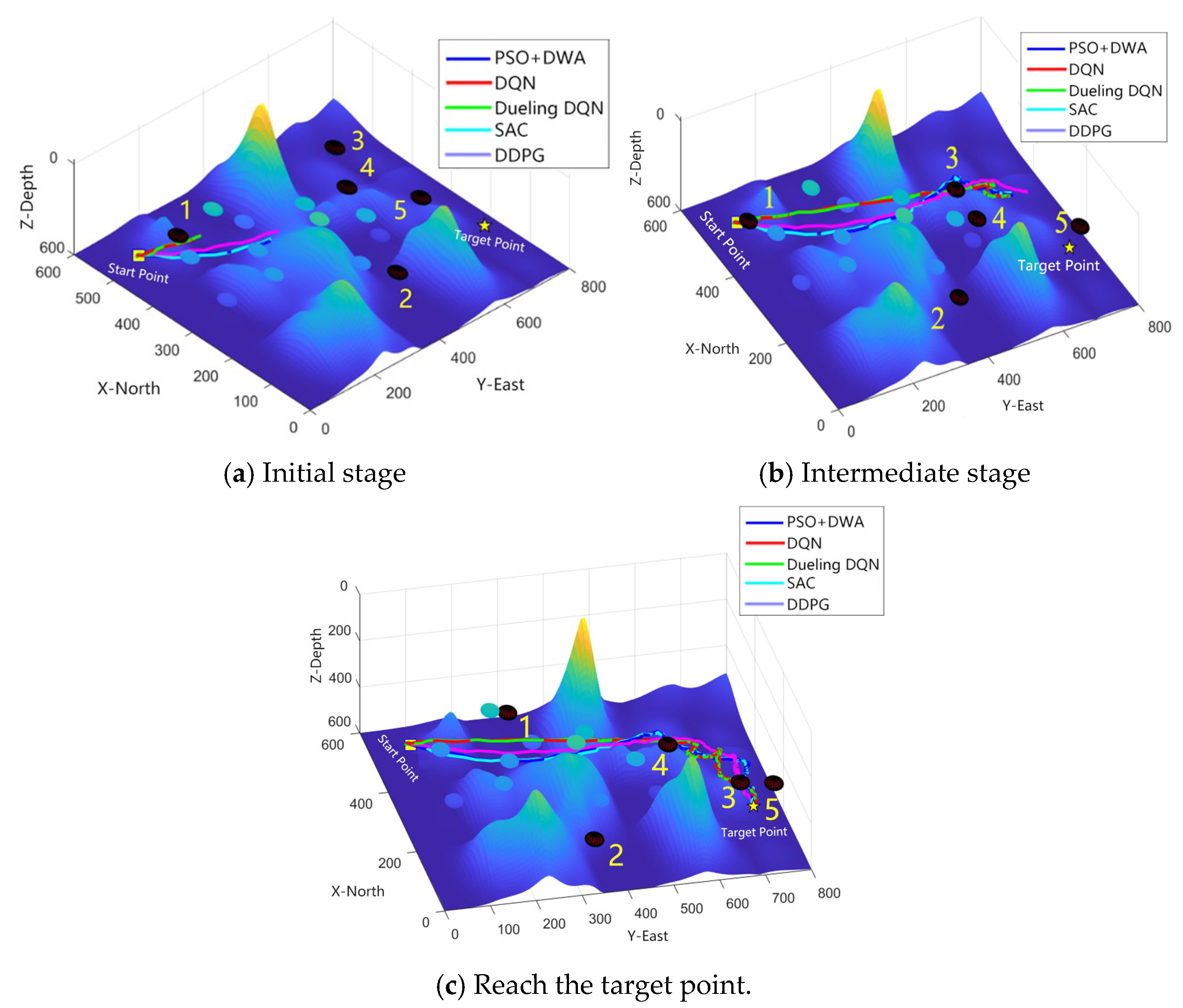

4.2. UUV Autonomous Navigation Planning and Route Tracking Capability Simulation Verification

The simulation environment shown in

Figure 13 simulates the scenario of a UUV searching for targets in narrow waters under variable depth conditions. The UUV starts from the yellow square starting point and heads for the yellow pentagonal target point. During navigation, the UUV will encounter multiple prohibited areas, including light-colored spherical static obstacles and dark-colored dynamic obstacles (such as minefields, enemy moving UUVs, sonar detection areas, etc.), as shown in the figure. These obstacles pose a threat to the safe navigation of the UUV. The simulation parameter settings for variable depth environments are shown in

Table 6. The experiment compares the autonomous collision avoidance performance of PSO combined with five algorithms, DWA, DQN, Dueling DQN, SAC, and DDPG, in a dynamic environment to evaluate the effectiveness and stability of these algorithms in dealing with environmental uncertainty.

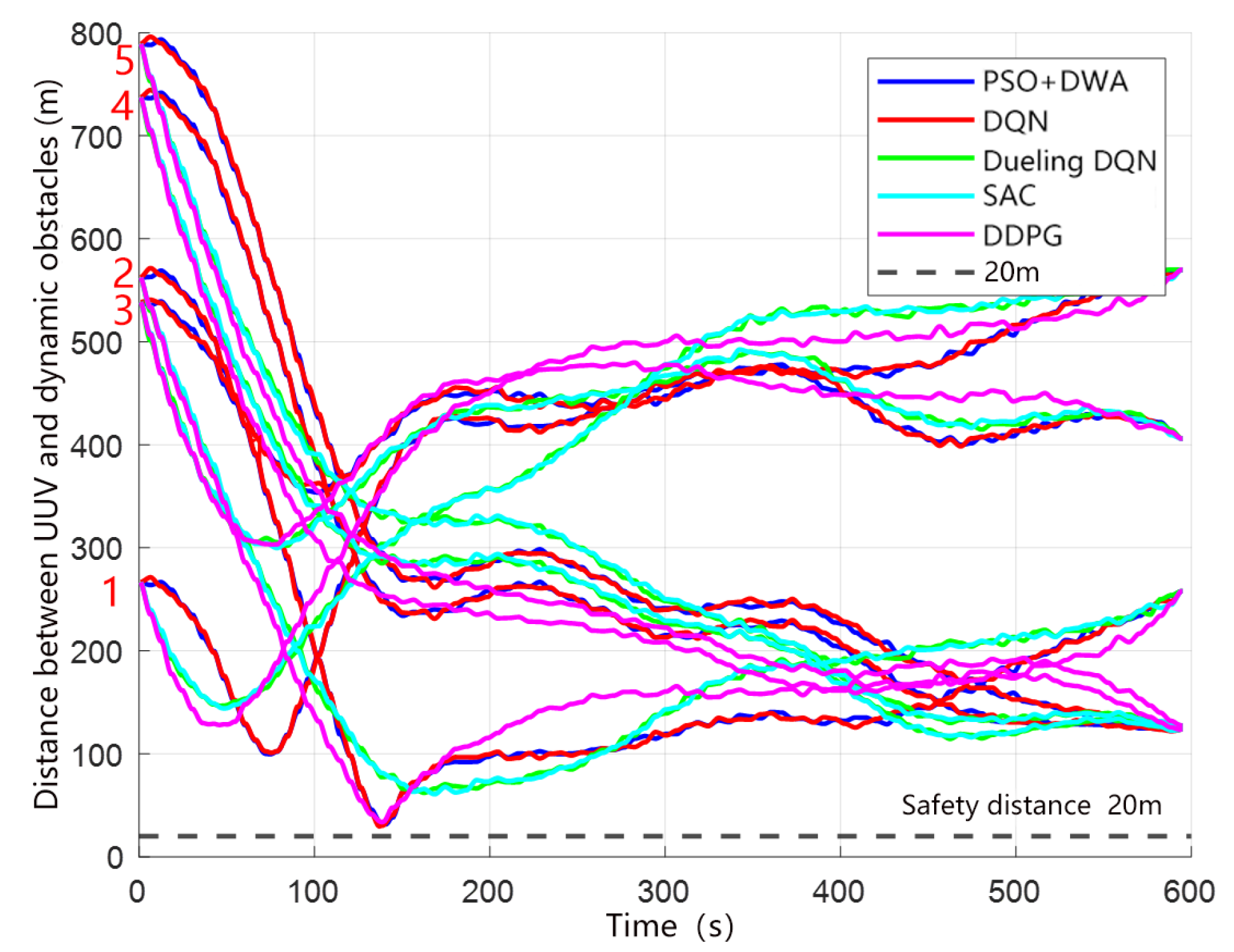

In the planning results of different algorithms shown in

Figure 14, the vertical axis marks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 correspond to the initial distances of the five dynamic obstacles relative to the UUV in

Figure 10. The performance of each algorithm in the figure can be evaluated by the change in the distance between the UUV and the dynamic obstacle over time. The longer the distance, the better the obstacle avoidance effect. The figure shows that the distance between the algorithm proposed in this paper and the dynamic obstacle is greater than 20 m, indicating that the UUV successfully avoided collisions with dynamic obstacles in all simulations of the autonomous collision avoidance planning algorithm.

Table 7 summarizes the path length, planning time, and minimum distance to dynamic obstacles of different algorithms. The results show that the DDPG algorithm generates the shortest path, while the DQN algorithm has the shortest average single-step planning time, that is, the output speed of the control command is the fastest. In contrast, the planning time of PSO combined with DWA is the longest, mainly because in a three-dimensional dynamic environment, the improved PSO requires multiple iterations to optimize the optimal global route, and the DWA algorithm with curvature constraints is also time-consuming each time it predicts the trajectory. In addition, the DWA algorithm with curvature constraints also consumes a lot of time to calculate the predicted trajectory each time. PSO combined with DWA, DQN, and DDPG are similar in the minimum distance to a certain dynamic obstacle. They can all effectively avoid obstacles and ensure the safe navigation of UUVs in complex environments. Relatively speaking, although the path lengths of Dueling DQN and SAC are greater than those of DDPG, their minimum collision avoidance distances with dynamic obstacles are larger, which also reflects a certain degree of safety redundancy.

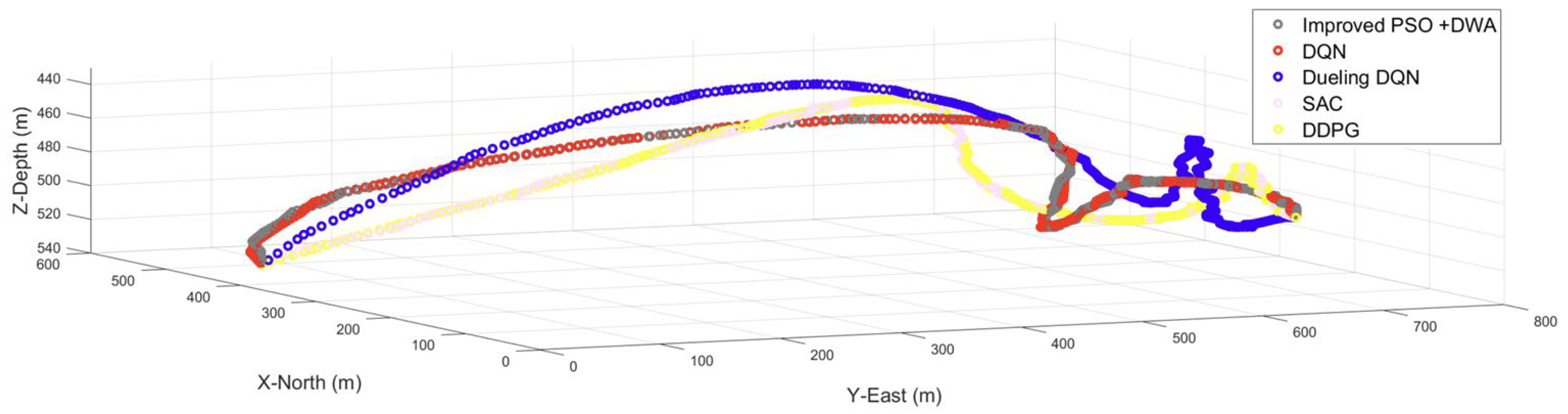

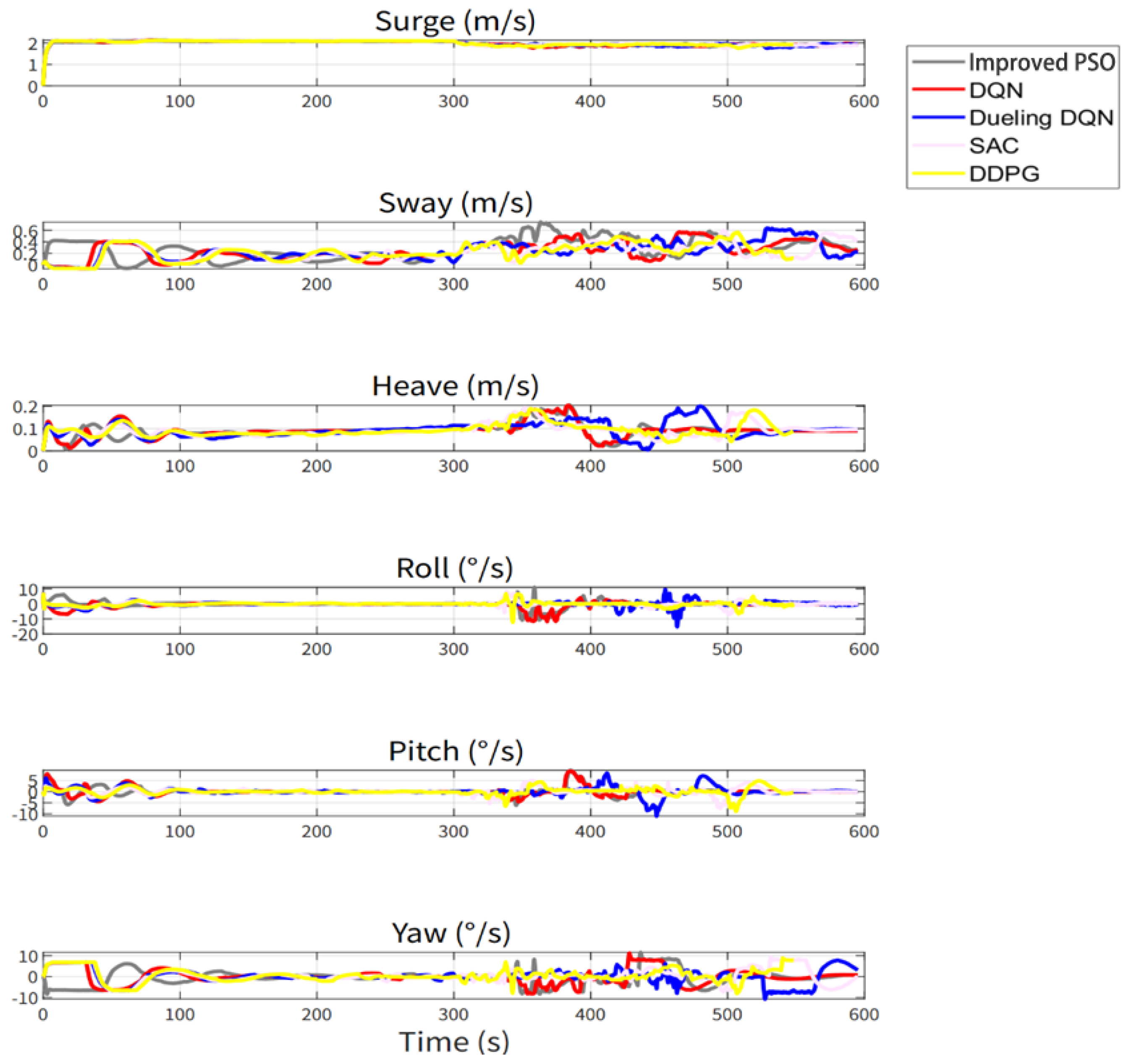

In order to verify whether the UUV waypoints generated by the planning algorithm are executable, the UUV waypoints in

Figure 15 are input into the 3-DOF model of the UUV to observe the change curves of each state quantity. When

, the ocean current disturbance is

,

; when

,

;

gradually increases from

to

and then

fluctuates in a small range.; when

,

gradually increases from

to

, and then fluctuates around

.

Combining

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 16, we can see that the trajectory of each algorithm runs relatively smoothly in the initial stage; when encountering dynamic obstacles 3 and 4, the DWA algorithm, DQN algorithm, and Dueling algorithm made a strategy to make the track bend more, especially the waypoints planned by the DWA algorithm and DQN algorithm, the UUV route tracking control system cannot complete effective tracking. However, the waypoints of the Dueling DQN algorithm can be realized by the UUV route tracking control system. The trajectories of the SAC algorithm and the DDPG algorithm are relatively stable, the overall tracking effect is good, and they show strong dynamic adaptability.

Figure 17 shows that in the presence of ocean current interference, the proposed three-dimensional ALOS guidance algorithm has relatively stable speed control in the longitudinal direction, indicating good control capability of the UUV longitudinal speed; all attitude quantities remain stable before 300 s, and the roll angular velocity and pitch angular velocity are close to 0 between 100 s and 300 s; between 300 s and 500 s, the collision avoidance behavior of each collision avoidance planning algorithm against dynamic obstacles causes fluctuations in attitude quantities. Combined with

Figure 16, it can be seen that the paths of SAC and the proposed DDPG algorithm are smoother, and the collision avoidance strategy is better. It can achieve stable and continuous heading adjustment, which is conducive to improving the overall tracking quality.

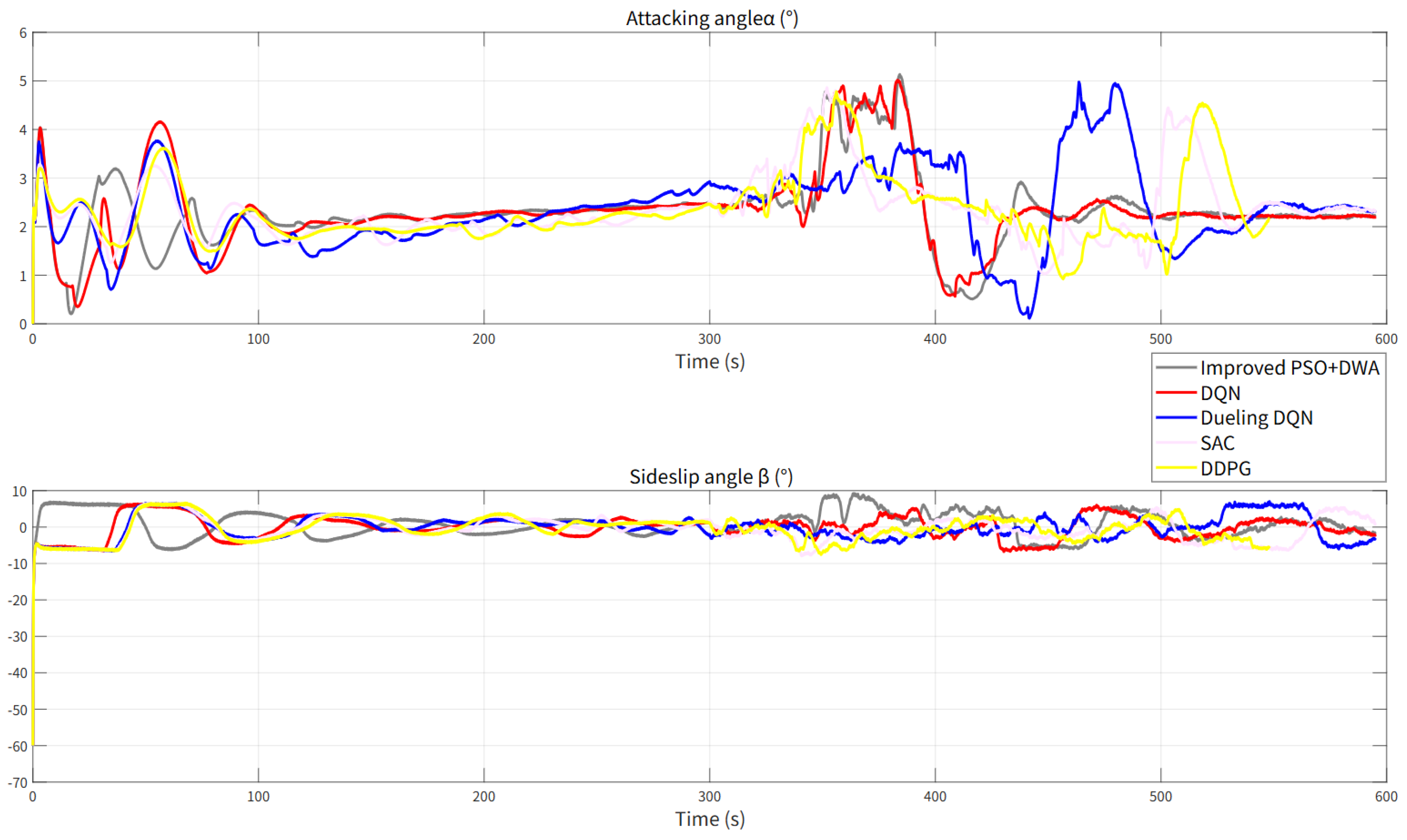

Figure 18 shows the changes in the angle of attack

and sideslip angle

during the navigation process of the UUV under different planning algorithms. The angle of attack of each planning algorithm is positive at the initial moment, indicating that the UUV is in the climbing stage. This is consistent with the path trajectory of

Figure 16, indicating that the pitch attitude control effect is good. The sideslip angle of the UUV at the initial moment is due to the large angle between the bow direction of the UUV and the direction of the ocean current at the beginning. Under the joint action of the three-dimensional ALOS algorithm and the controller, the sideslip angle decreases rapidly. The sideslip angle of each algorithm is controlled within ±10°. The results show that the three-dimensional ALOS track tracking method combined with the collision avoidance strategy can effectively improve the attitude stability of the UUV in a time-varying ocean current environment.

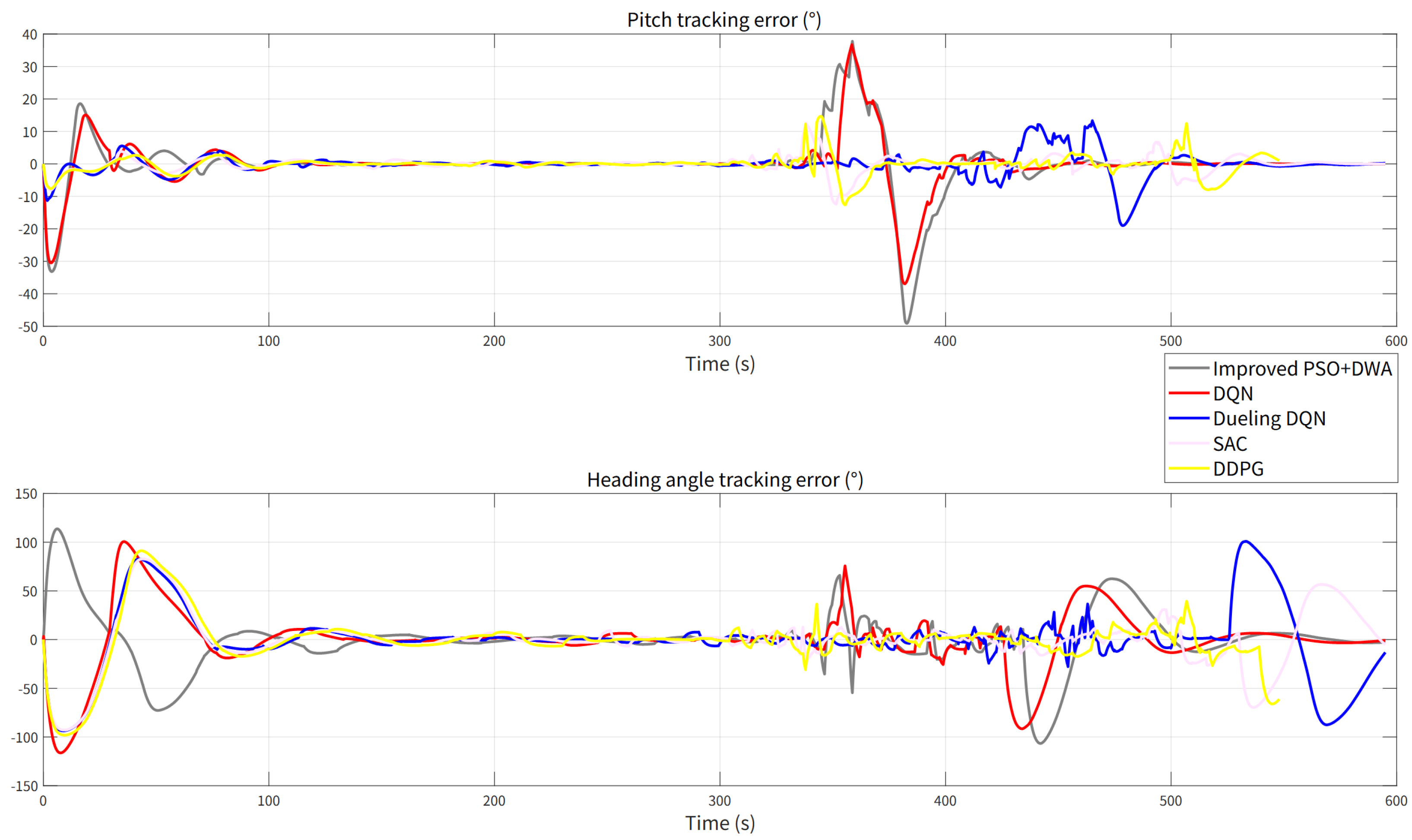

Figure 19 shows the pitch angle and bow angle tracking errors of each algorithm. In the variable depth collision avoidance planning and three-dimensional route tracking tasks, the DDPG algorithm performs best in pitch angle, bow angle, and position error indicators, showing good route tracking accuracy. The SAC algorithm also has high attitude and trajectory control capabilities and is suitable for autonomous navigation in dynamic and complex environments. DQN and Dueling DQN have certain deficiencies in attitude control accuracy and trajectory smoothness. As shown in

Figure 16, the traditional improved PSO + DWA and DQN algorithms cannot reach the target point safely, and it is difficult to complete obstacle avoidance planning in highly dynamic scenes.

Table 8 shows the comparison of the RMS of pitch angle tracking and bow angle tracking of different algorithms in a variable depth environment. The SAC algorithm has the smallest RMSE for pitch angle tracking; the DDPG algorithm has the smallest RMSE for bow angle tracking, which is 12.8%, 17.1%, 21.7%, and 9.4% lower than the DWA, DQN, Dueling DQN, and SAC algorithms, respectively; the DDPG algorithm has the smallest RMSE for position tracking, which is 23.8%, 15.04%, 14.2%, and 11.1% lower than the DWA, DQN, Dueling DQN, and SAC algorithms, respectively. Overall, DDPG shows comprehensive advantages in robustness, accuracy, and track smoothness, verifying its superiority in complex 3D dynamic environments.

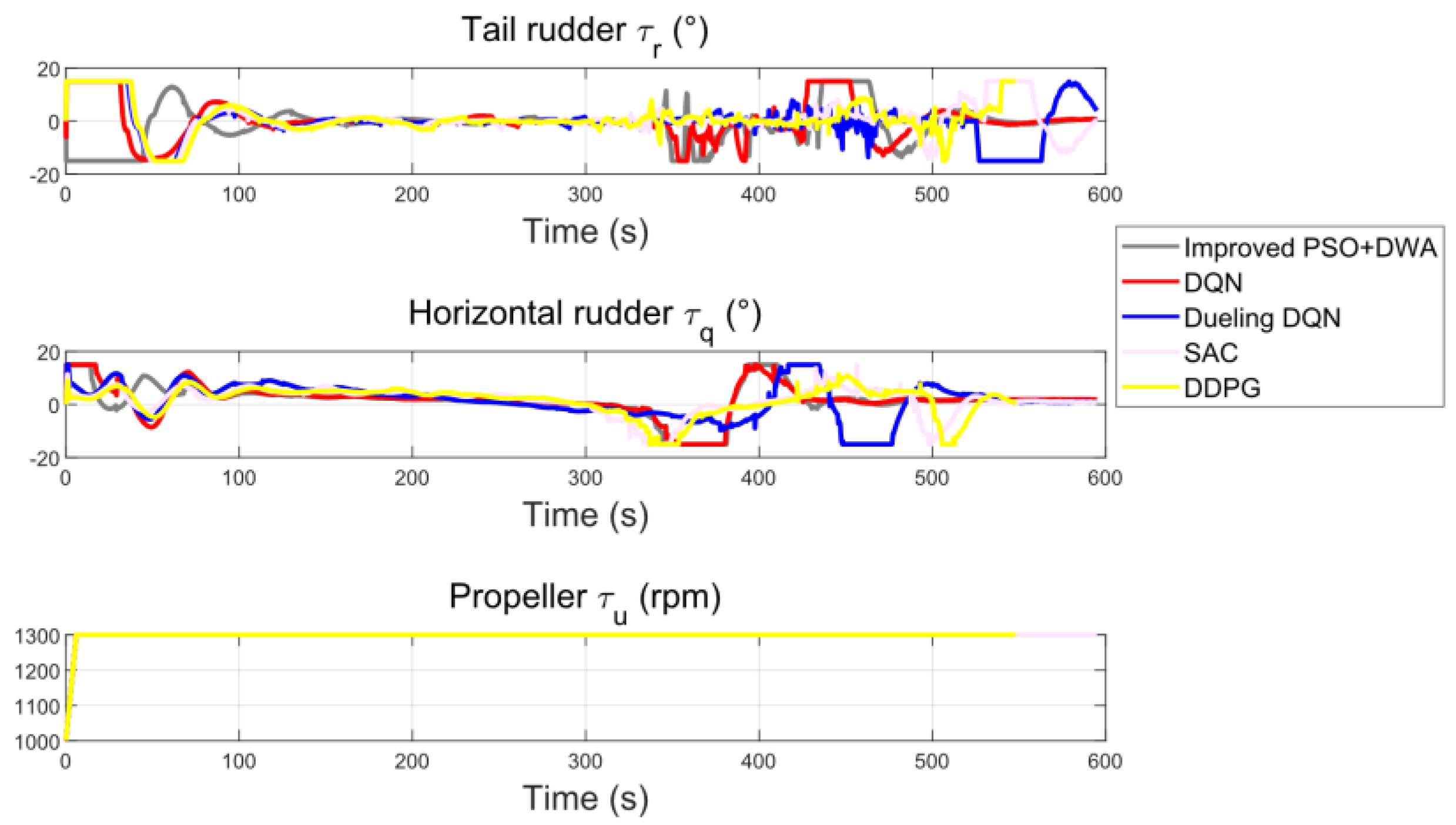

In the UUV actuator change curves of

Figure 20, different planning algorithms, DDPG and SAC, have the smallest fluctuations in the changes in horizontal rudder angle and tail rudder angle, and the control is smoother; the thruster speed of each method can be maintained stably, ensuring the UUV speed stability and track tracking continuity.

From the above simulation results, it can be seen that the improved DDPG algorithm in this paper shows better tracking performance, especially in the bow angle tracking error and position tracking error, which are better than other DRL methods. It is suitable for UUV autonomous navigation tasks with high requirements for route tracking accuracy and stability. The change curve of the actuator shows that the control is smoother, and the algorithm also meets strong adaptability. In addition, compared with the improved DWA algorithm, the collision avoidance planning time of the DDPG algorithm, SAC algorithm, and improved DWA algorithm is shortened by more than 95%, which proves that the DRL algorithm has strong real-time performance when doing collision avoidance planning. The distance between the algorithm proposed in this paper and multiple dynamic obstacles is greater than 20 m, indicating that the UUV successfully avoids collision with dynamic obstacles under the planning of all autonomous collision avoidance algorithms.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a hierarchical autonomous navigation framework for unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), combining global route planning based on an Improved particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, local collision avoidance using a deep deterministic policy gradient (DDPG) method enhanced by noisy networks and proportional priority experience replay (PPER), and robust three-dimensional path tracking using an adaptive line-of-sight (ALOS) guidance strategy.

In summary, the proposed method demonstrates strong capability for efficient and safe UUV navigation in scenarios involving sparse rewards, limited perception, and nonlinear motion coupling. The framework effectively bridges global planning, local avoidance, and route tracking into a coherent autonomous navigation strategy.

Future research work on this topic includes:

When facing multiple dynamic obstacles, the UUV’s collision avoidance planning ability is not as good as the DWA algorithm with curvature constraints. In the future, it is planned to add the ability to perceive dynamic obstacles to the model, use the extended Kalman filter (EKF) for online filtering and trajectory prediction of dynamic obstacles, integrate the EKF output into the state input of DRL, and introduce the reward function of dynamic obstacles. Use the LSTM/GRU network to help the UUV remember the movement trend of obstacles in the past few steps to improve the collision avoidance prediction ability.