1. Introduction

The coastline represents a dynamic space of great ecological, economic, and social value [

1]. However, it is also one of the most fragile environments on the planet [

2], subject to constant interaction between terrestrial, atmospheric and marine processes that shape its morphology [

3].

The coastal zone, due to its transitional nature between the terrestrial and marine environments, hosts a wide variety of ecosystems and natural resources. This environmental richness, combined with its accessibility and scenic value, has historically encouraged the concentration of population and economic activities nearby. It is estimated that around 60% of the population is concentrated along the coastline [

4]. Over time, this phenomenon has intensified, especially since the late 20th century, when the growth of tourism in Europe solidified the recreational use of beaches [

5]. Since then, the coastline has experienced increasing occupation, linked to the expansion of urban infrastructure and the rising demand for tourism services [

6,

7]. This trend has been particularly pronounced in regions such as the Mediterranean, where the number of residents and visitors has grown significantly in recent decades [

8,

9,

10]. The growing influx of users has influenced the way beaches are managed. Today, many decisions focus on meeting public needs, prioritizing recreational use over ecological or conservation criteria [

11]. Furthermore, to address the risks associated with erosion and to protect urbanized areas near the sea, regenerative measures such as beach nourishment are undertaken, along with the construction of various protection structures like groynes or breakwaters. However, these interventions, far from solving the problem, have disrupted the natural balance of the coastal system by interrupting sediment transport and promoting erosion processes in other areas of the coastline [

12].

On the other hand, the shoreline is one of the most complex elements to delineate within the coastal system due to its dynamic and changing nature [

13]. Although it can be basically defined as the meeting point between land, sea, and atmosphere [

14], this description is insufficient when attempting to accurately quantify the processes of retreat or advance of the coastal strip. Its exact location is influenced by multiple factors, such as the slope of the beach profile, sea level fluctuations, and wave intensity, which can create ambiguities when interpreting the shoreline at different times [

15,

16]. In this context, the coastline undergoes changes at different temporal scales. In the short term—ranging from hours to days—the effects of storms, tides, and storms dominate, which can cause significant variations in the profile without indicating a real trend [

17]. In the medium and long term—spanning decades to centuries—factors such as changes in sediment balance, sea level rise, and human intervention come into play [

18,

19,

20,

21]. However, the high short-term variability can obscure underlying trends, so numerous studies recommend using long time series, with records distributed over more than ten years, to more reliably detect the evolutionary behavior of the coastline [

17,

22].

Finally, among the agents influencing coastal evolution, those induced by human activity can be distinguished from those of natural origin. The main natural factors are sea level fluctuations, wave patterns, currents, and storms. The role of anthropic activity is increasingly decisive, both due to the reduction in sediment supply—through reservoirs, urbanization, or dune destruction—and the installation of infrastructures that modify longitudinal sediment transport, such as ports, groynes, or breakwaters. These types of alterations cause sediment accumulation on the updrift side of the structures and erosive processes downstream [

21,

23,

24]. Furthermore, climate change is intensifying these natural and anthropogenic dynamics. The alteration of hydrodynamics and the sea level rise increase the rate and extent of erosion, as well as a greater risk of coastal erosion [

25]. In this regard, the IPCC projections (2007) estimate a possible sea level rise of up to one meter by the end of the century [

26]. Although recent predictions are less dramatic, an increase in sea level could worsen coastal retreat, as is currently observed in one-quarter of the coastline of the Valencian Community [

1].

In this context, to study these changes, the comparison of shorelines based on historical data has become one of the most widely used methodologies [

21]. This approach allows for determining rates of erosion or accretion depending on the mechanisms influencing the coast, thereby projecting possible future changes, which is key for spatial planning [

27,

28]. However, shoreline analysis can present limitations when based on isolated observations or very short periods. Seasonal variations, run-up, or sea level fluctuations can induce errors if there are not enough records distributed in a representative manner [

20]. In recent years, the use of technologies such as satellite imagery, aerial photography, LiDAR sensors, video surveillance, and RTK-GPS has increased the capacity for observation and precision in detecting the shoreline. Despite this, satellite images have spatial resolution limitations that affect erosion rate calculations, though they enable digital processing to enhance shoreline extraction [

6,

14]. To facilitate analysis, tools such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have become essential, as they allow for the comparison of spatial data from different periods and the analysis of the morphological evolution of the coastal strip [

6,

29]. Finally, the Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) complement enables quantification of shoreline changes both in the short [

30,

31] and long term [

32].

This study focuses on analyzing the evolution of the coastline between the Port of Valencia and the Port of Sagunto from 1957 to the present day. The aim is to quantify changes in the shoreline over time through the application of Geographic Information System (GIS) tools and the calculation of key quantitative indicators, including the End Point Rate (EPR), Linear Regression Rate (LRR), Net Shoreline Movement (NSM), Shoreline Change Envelope (SCE), and Weighted Linear Regression (WLR). The objective of the research is to identify areas affected by predominant erosion or accretion processes, the interpretation of which will be related to both anthropogenic and natural factors. This is a 20 km stretch of coastline that has been studied exhaustively on three different time scales: long term (1957–2024), medium term (1997–2024) and short term (2015–2024). This time intervals were selected based on the availability of historical and recent data on the coastline. The longest period (1957–2024) includes all available observations from the oldest historical records, allowing for the analysis of long-term trends. The intermediate interval (1997–2024) reflects the start of modern satellite coverage, while the shortest interval (2015–2024) focuses on the most recent high-resolution data. This selection ensures that each analysis is based on reliable data series, optimizing the assessment of coastal processes across different time scales. Its importance lies in the fact that it is one of the areas with the highest number of coastal infrastructures on the Valencian coast, built since the 1970s. Capturing significant spatial and temporal variations and detecting underlying trends is essential for future short- and medium-term actions, whose evolutionary model could be exported to other microtidal coastal sectors. The results obtained will be an important contribution to coastal management, environmental conservation, and land-use planning in vulnerable coastal regions. This research constitutes an important contribution to our understanding of the coast, as until now, no comprehensive analyses of coastal evolution have been conducted for the coastal section in this area, except for regional studies or isolated geomorphological observations.

2. Study Area

The study area covers approximately 20 km of coastline and is located in the province of Valencia (Valencian Community, Spain), specifically in the coastal section between the Port of Valencia and the Port of Sagunto (

Figure 1). This area is characterized geomorphologically by the presence of beaches, fossil dunes, and alluvial plains [

33]. The beach sediment is mainly sand, pebbles and gravel, with a low content of sediment of biological origin. Palancia River is the main source of the fluvial deposits that reach the coast. However, some sections have been artificially nourished with sand to promote tourism.

From an oceanographic perspective, a microtidal regime is observed, with a range of less than 30 cm and an astronomical component of about 8–10 cm, typical of the western Mediterranean [

4]. However, meteorological storm surges constitute the main factor causing sea level variations, which can reach up to 45 cm during extreme events. These surges are associated with sudden drops in atmospheric pressure, with an average response estimated between 2 and 3 cm per hectopascal (hPa) in the Mediterranean, whose sensitivity is greater than that recorded in the Atlantic (around 1.5 cm/hPa) due to the semi-enclosed nature of the Mediterranean Sea [

34].

The prevailing winds in the area have a direct influence on the direction of incoming waves, which affects the formation of coastal currents and the transport of sediments along the shore [

4]. The coastal currents in the area have a net southward direction, mainly driven by the prevailing east and northeast winds [

34,

35]. To characterize the marine dynamics and wave conditions in the stretch between the Port of Valencia and the Port of Sagunto, data from SIMAR node number 2081115, managed by Puertos del Estado [

35], have been used. This point was selected for its proximity to the studied coast, allowing for representative recordings of the oceanographic conditions along the coastline under study. Although no significant trend has been detected in the increase in storm surges (1993–2022), the frequency of extreme events appears to be rising; this is the case in Valencia, where the storm surges (SS) greater than 20 cm have increased by +1.5 mm/year [

34]. Global studies such as those by Griggs and Reguero [

36] warn that rising sea levels and increased storm intensity will heighten flood risks in coastal wetlands, affecting vulnerable areas like Marjal dels Moros, due to its lower topography.

Finally, the area as a whole is considerably anthropized and features a wide variety of coastal infrastructures that modify the coastal dynamics and shoreline. This stretch is bounded to the south by the Port of Valencia and to the north by the Port of Sagunto, two port infrastructures that act as barriers to the north-south longitudinal sediment transport. Additionally, throughout the studied sector, a large number of groynes, breakwaters, dikes, promenades and other structures are distributed, which interfere with the coastline and alter accumulation and erosion patterns, limiting the natural processes of beach regeneration. The distribution of these structures is greater in urbanized areas compared to more natural zones. Finally, in some sectors of the study area, regenerative measures were carried out to restore ecosystems and protect the coastline against erosive processes. On one hand, a volunteer action coordinated by Acció Ecologista-Agró Horta Nord, in collaboration with the Sagunto City Council, restored the flora of the dunes at Puzol Beach [

37]. This measure, in addition to contributing to the conservation of native flora, also increased the area’s resistance to erosion by protecting the dune system. Moreover, in Marjal dels Moros, the coastline was replenished with external sandy material as a soft measure to preserve it against storms [

38]. These types of regenerative actions help restore environments and mitigate erosion.

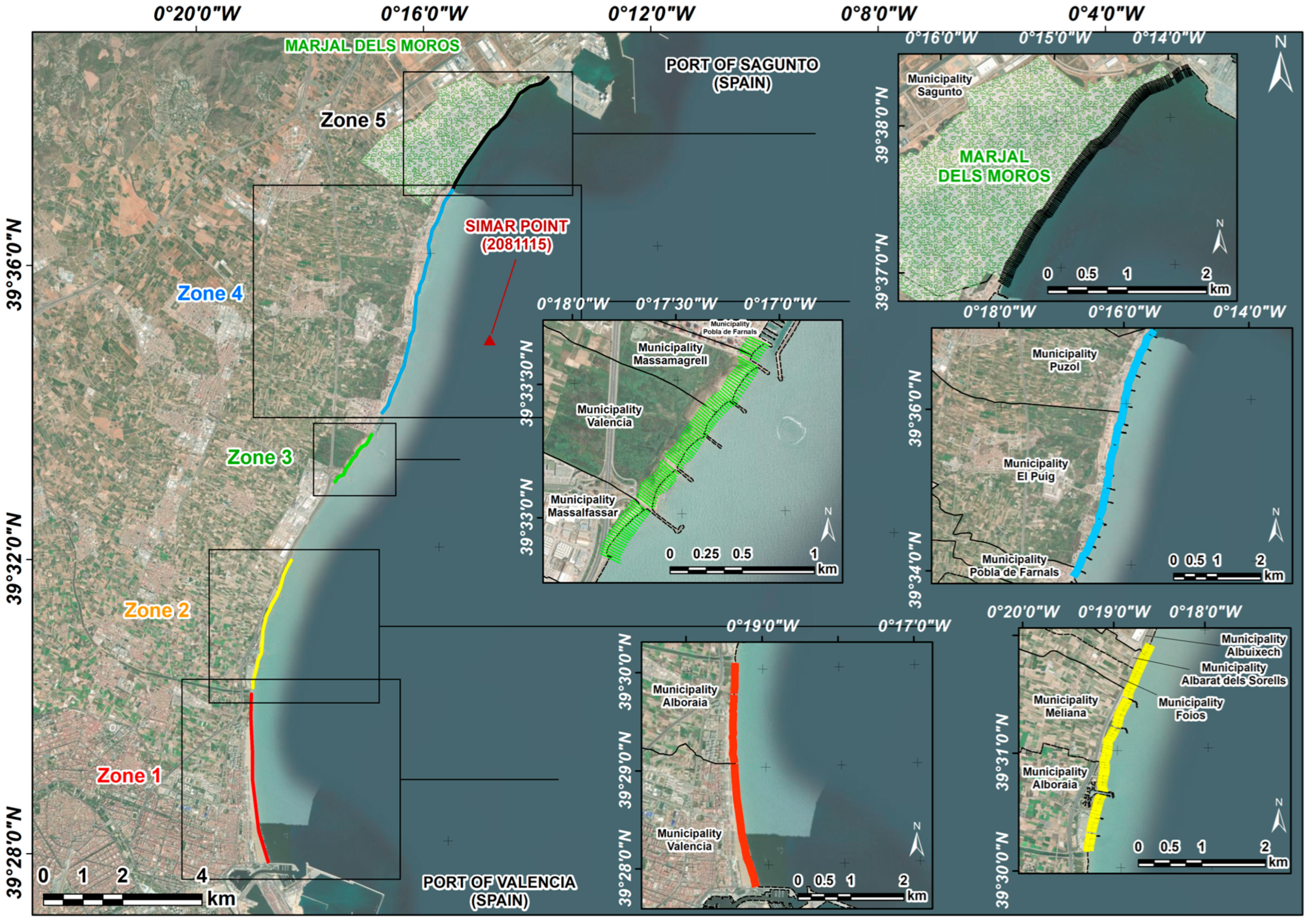

To conduct a more detailed analysis and more clearly identify the shoreline behavior patterns, the study area was divided into five distinct sections based on the geomorphological, sedimentary, and anthropogenic characteristics of the coast: Arenas–Malvarrosa–Patacona, Port Saplaya, Pobla de Farnals, Puzol, and Marjal dels Moros (

Table 1). At the sedimentary level, beaches composed of sand and pebbles dominate all five zones [

33], especially in zones 1, 3, and 4. From an anthropogenic perspective, all areas are characterized by a significant presence of coastal protection structures (groynes, breakwaters, among other), which alter the coastal dynamics, in addition to existing port infrastructures. In zone 5, slag deposits resulting from the industrial activity of the Altos Hornos de Sagunto stand out, acting as a barrier against erosion [

24].

3. Materials and Methods

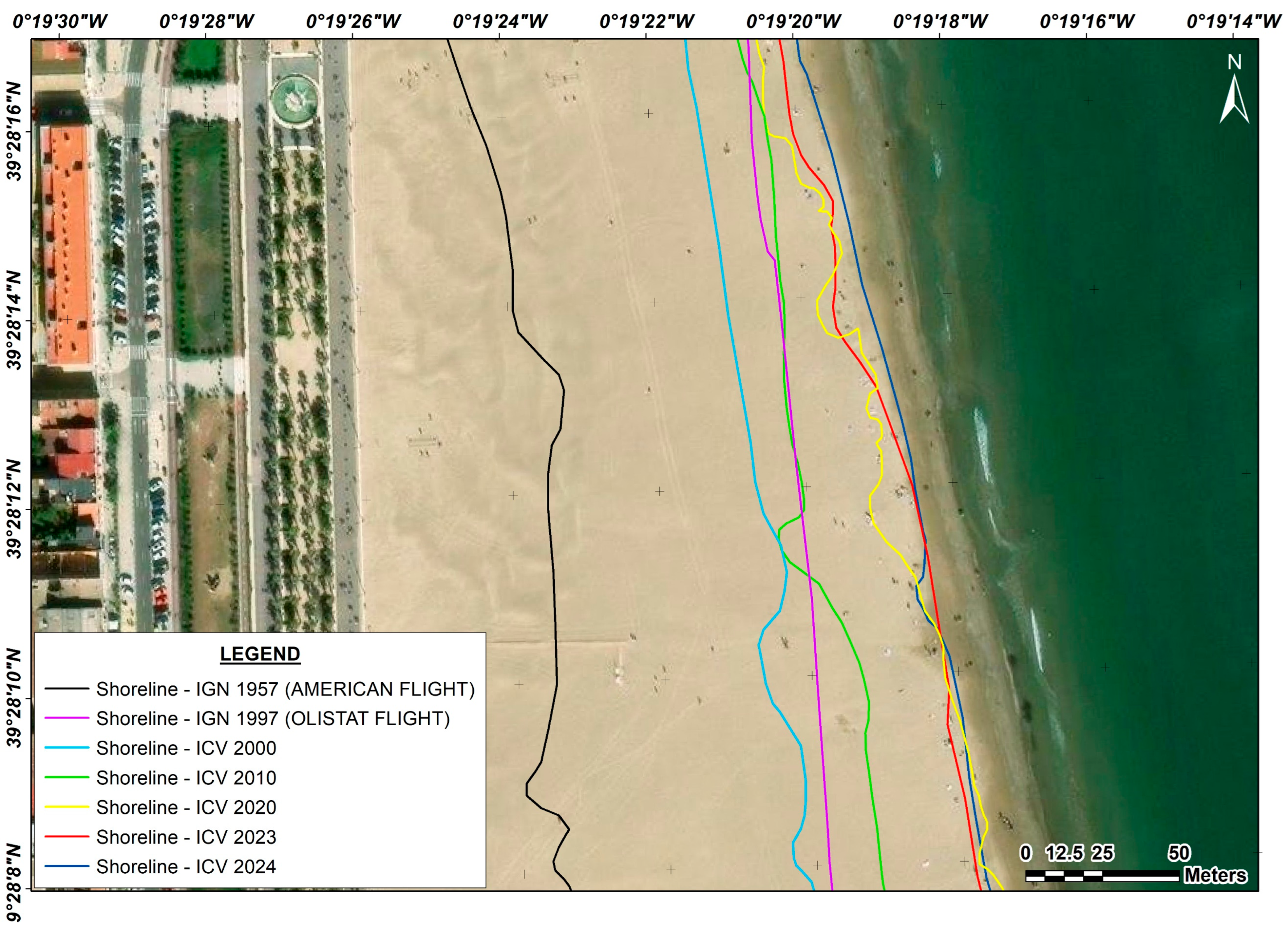

To carry out the study of the coastline evolution in the stretch between the Port of Valencia and the Port of Sagunto from 1957 to 2024, a series of satellite images and orthophotos of the area within that time frame were obtained. These images were downloaded from the data sources of the official websites of the National Geographic Institute (IGN) and the Valencian Cartographic Institute (ICV) (

Table 2) and were projected to the UTM Zone 30N coordinate system (EPSG: 25830) in order to facilitate the calculation of length metrics. Once the images were obtained, they were added to the QGIS software (version 3.40). QGIS is one of the main GIS software used for shoreline digitization, data analysis and figures creation. Then, each shoreline was manually digitized using a polyline composed of multiple points, following a consistent criterion for each one of them (

Figure 2).

To delineate the shoreline, the visual criterion of the transition between the dry zone and the wet part of the beach was used, that is, the wet-dry boundary, which marks the usual reach of the water [

39]. As this is a microtidal coast, tides were not taken into account for this study [

17]. The tides produced by atmospheric effects have also not been taken into account, as the marine conditions reflected in the orthophotos analyzed are similar and do not correspond to stormy conditions. Nevertheless, meteorologically induced water-level variations may locally affect the wet–dry boundary used as shoreline proxy. Although their magnitude is generally small compared to the long-term shoreline shifts observed in this work, they may contribute to short-term variability, particularly in the 2015–2024 period. This widely used and recognized criterion allows for clear distinction of the shoreline in aerial photographs and shows relative stability against momentary variations in waves or tides, making it a good indicator of the coastal position [

16]. Therefore, changes in the coastline reflect erosion/sediment accumulation on the coast and not differences in tides, which justifies the fact that the position of the tides is not a determining factor in the images. Once the shorelines from each of the obtained images were digitized, the DSAS extension [

40] was used to calculate the distances between them, enabling a more precise analysis. DSAS version 6.0.170 is currently a freeware and a standalone software developed by USGS (USA). This tool generates perpendicular profiles, called transects, from a baseline and calculates various metrics that quantify the changes in the shoreline over time.

Although the study area is microtidal, short-term water-level variations associated with meteorological forcing—mainly storm surges—can locally raise sea level by up to 45 cm during energetic events [

34]. Such variations may shift the wet–dry boundary landward or seaward, introducing short-term positional noise in the extracted shoreline. This effect is especially relevant for the high-resolution 2015–2024 dataset, in which small interannual displacements may partly reflect water-level anomalies rather than true morphological change. However, this source of noise is partially mitigated by the use of regression-based indicators (LRR, WLR), which integrate multiple shoreline positions and reduce the influence of episodic events. For this reason, short-term coastal trends in this study are interpreted with caution and in the broader context of multi-decadal behavior.

To perform the calculations in DSAS, a baseline parallel to the digitized shorelines was created using the buffer geoprocess (100 m) and subsequent digitization of the outer boundary as a polyline. This baseline serves as a reference for generating the transects, which are perpendicular to it, with a length of 150 m, a spacing of 20 m, and a smoothing distance of 200 m. The 20 m spacing between transects was chosen to ensure spatial independence between sampling units, minimize autocorrelation, and at the same time maintain adequate coverage of the study area. Using the transects and shorelines from different years, and applying the statistics tool included in DSAS, a series of parameters were obtained:

- (a)

End Point Rate (EPR): Calculates the total change in the shoreline by dividing the net shoreline movement (NSM) by the number of years between the first and last dates of the analysis, expressed in meters per year. Its main strength lies in its simplicity of calculation. However, since it is based only on two time points, it does not consider the available intermediate data, which can limit its ability to adequately reflect changes or trends over time. For this reason, it is common to compare its results with more robust methods, such as linear regression or weighted regression, which take multiple observations into account [

41].

- (b)

Linear Regression Rate (LRR): Estimates the overall trend of coastal change by fitting a linear regression line to all available shoreline positions. In this calculation, the linear regression is derived from the intersection points of each transect, and the slope represents the rate of change expressed in meters per year. It is a useful tool for predicting how the coastline may evolve in the future and allows for assessing whether there is a clear relationship between the passage of time and shoreline movement. However, it can be affected by outliers that skew the results and, in some cases, tends to produce a lower rate of change compared to other methods [

17].

- (c)

Net Shoreline Movement (NSM): Represents the distance (m) between the oldest and most recent shoreline positions, without considering the time elapsed [

32].

- (d)

Shoreline Change Envelope (SCE): Indicates the maximum distance (m) between the most distant shoreline positions, regardless of their temporal order [

40].

- (e)

Weighted Linear Regression (WLR): Similar to LRR but incorporates the uncertainty of each shoreline position as a weighting factor in the analysis, reducing the impact of less precise data and improving the reliability of the statistical fit [

40]. It is used to represent how the shoreline has evolved over time. This method allows identification of areas that have changed more rapidly, helping to highlight zones that may be more vulnerable to erosion [

17,

42].

These indicators allow for a detailed analysis of erosion and accretion processes along the coast, as well as the detection of potential spatial or temporal behavior patterns. Positive values of the parameters indicate a seaward movement of the shoreline (accretion), while negative values indicate a landward movement (erosion).

It is important to consider the limitations of this study, as it is based on images with varying resolutions and temporal coverages, whose characteristics may influence the manual digitization of the shorelines. Additionally, the study area contains a large number of anthropogenic structures that alter the shoreline and sediment balance. The total uncertainty in determining the position of the coastline was calculated by considering three main sources of error: the spatial resolution of the images, the manual accuracy in digitization, and the zoom level used during tracing. In this study, most of the aerial photographs used had a spatial resolution of 0.25 m, corresponding to the pixel size. Manual accuracy was estimated based on the operator’s “hand steadiness” when drawing the line, and an approximate error of 0.75 m was assumed. The zoom level applied during digitization was around 1:2000, which translates into an additional estimated error of 0.75 m. Combining these sources using the root sum of squares (RSS), the approximate total uncertainty in the location of the coastline was calculated as:

This calculation is based on approximations derived from the study by Ruggiero et al. (2013) [

43], in which they derived the uncertainty of coastline tracing using multiple variables. For this study, only those mentioned above have been considered. However, it is important to note that errors associated with the rectification of satellite images and orthophotos have not been taken into account in these calculations. The positional uncertainty of the extracted shoreline was quantified following the standard DSAS approach, combining georeferencing error, pixel resolution, orthorectification accuracy and wet–dry boundary interpretation. The resulting total shoreline positional uncertainty is estimated at ±1.1 m. This value was assigned as the uncertainty parameter for the DSAS calculations and should be considered when interpreting short-term change rates.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of the Indices Obtained

A representative image of the different areas is shown in

Figure 3. The average statistical values obtained for each parameter in the five delineated zones are shown in

Figure 4, broken down into three different temporal scales: long term (1957–2024), medium term (1997–2024) and short term (2015–2024) (

Table 3). The criteria used to define the different scales were the context and availability of data, as well as the balance between resolution and noise in coastal evolution data. The long-term trend captures structural trends and changes in the system over several decades. In the medium term, decadal variability and the effects of modern climate and management patterns are analyzed. In the short term, rapid responses to extreme events and recent transient dynamics are addressed. Statistical values were obtained for each of the five parameters analyzed (EPR, LRR, NSM, SCE and WLR). The results of this study include: mean, median, standard deviation, total sum, minimum, maximum, range, as well as the values of the first quartile (Q1), third quartile (Q3), and the interquartile range (IQR). These values are shown in the

Tables S1–S3 (see Supplementary Materials). The descriptive statistics (mean, median, SD, min–max, quartiles) for each DSAS metric were included as supplementary.

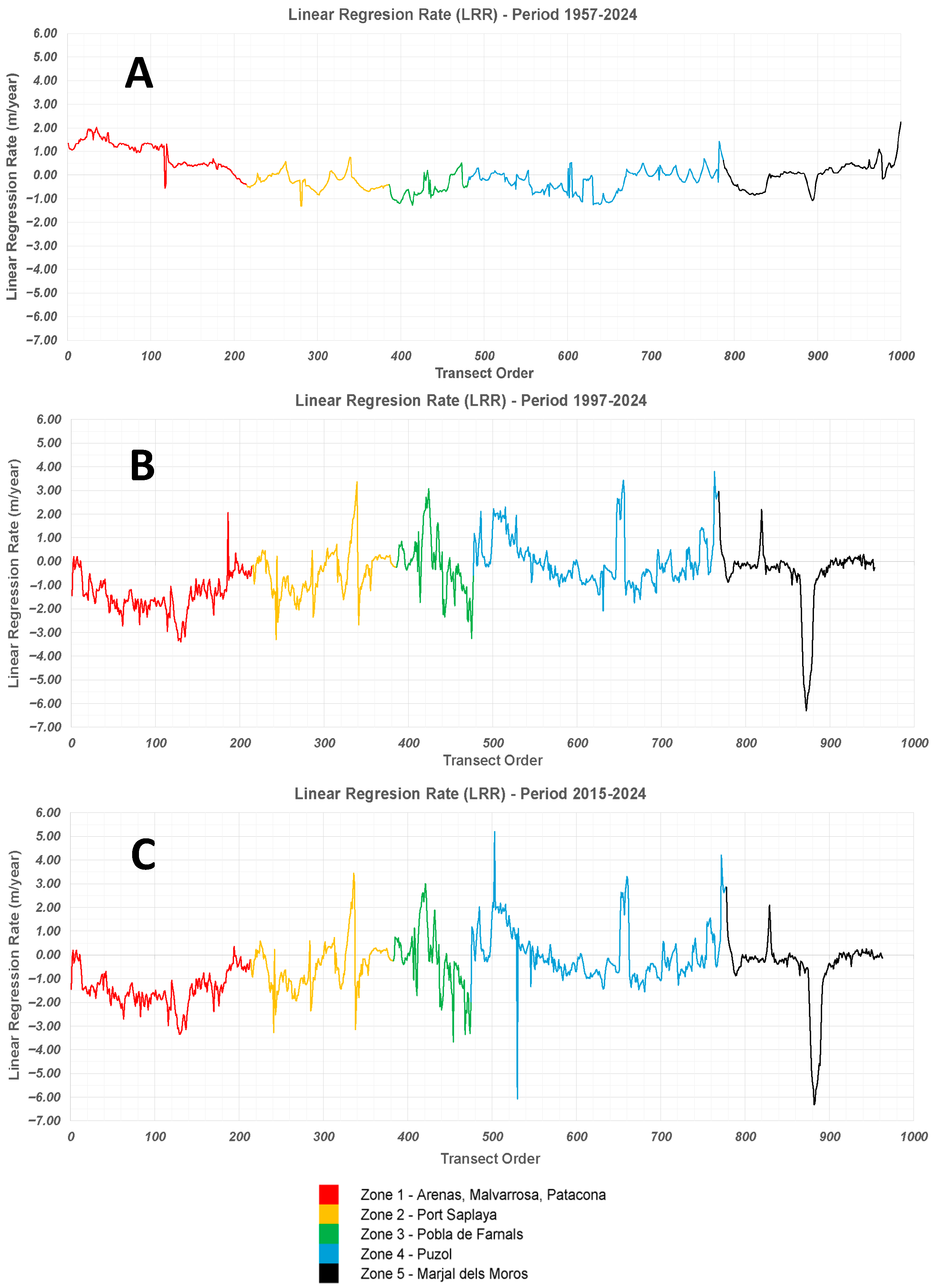

With the aim of clearly and comparatively representing the results graphically, the LRR parameter was selected. Unlike other parameters such as NSM or SCE, which can be more influenced by extreme values or isolated changes, LRR offers a more consistent view of coastal behavior over time (see

Supplementary Materials), allowing for the identification of a general and stable trend in shoreline evolution [

17].

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show the evolution of the LRR and WLR indicators across the five study zones over three different time periods: 1957–2024 (long term), 1997–2024 (medium term), and 2015–2024 (short term).

In

Figure 4A and

Figure 5A (1957–2024) gentle fluctuations are observed in most zones, with generally positive values standing out in Zone 1 (Arenas–Malvarrosa–Patacona) and negative values in Zones 2, 3, and 4 (Port Saplaya, Pobla de Farnals, and Puzol). In Zone 5 (Marjal dels Moros), there is a noticeable trend towards positive values in the final section.

The variations in the LRR progressively increase when the 1997–2024 time interval is considered (

Figure 4B and

Figure 5B). All zones exhibit more pronounced peaks, both positive and negative. Notably, there is a very pronounced minimum value in Zone 5, which did not appear in the longer-term timeframe. Additionally, more intense oscillations are identified in the central zones (Zones 2, 3, and 4).

In the shortest time interval (2015–2024), a general trend toward negative values is observed in most of the sections (

Figure 4C and

Figure 5C). Zone 5 maintains a graph shape similar to that of the intermediate time interval, with relatively constant low values. Zones 2 and 3 show less variability compared to the longer time frames.

A clear spatial correspondence between anthropogenic structures and shoreline-change patterns can be identified across the study area. In all groyne fields (Zones 2–4), accretion consistently occurs on the updrift side of the structures, while downdrift sectors show persistent erosion, following the expected response under a predominant southward sediment transport. Similarly, the northern breakwater of Valencia Harbour promotes sediment accumulation immediately updrift, whereas the southern sectors exhibit erosion. In Zone 5, the boundary of Sagunto Harbour produces a comparable downdrift erosional shadow. Although no formal distance-based quantification was performed, these structure-associated patterns are spatially coherent across transects and provide strong qualitative evidence that anthropogenic interventions exert primary control on the observed shoreline changes.

4.2. Dominant Processes and Time Scales

The analysis of the obtained results has made it possible to identify significant spatial and temporal patterns in the evolution of the coastline. To strengthen the analysis and validate the findings, this information was compared with a recent study conducted by the Geoenvironmental Cartography and Remote Sensing Group (CGAT) of the Polytechnic University of Valencia (UPV), in collaboration with the Valencian Cartographic Institute (ICV), which provides a detailed and up-to-date view of the coastal dynamics in the Valencian region.

The apparent discrepancy between the long-term LRR values and the short-term behavior depicted in

Figure 5A is explained by the different temporal sensitivity of the indicators. The LRR incorporates all shoreline positions between 1957 and 2024, giving equal weight to early decades characterized by widespread accretion in Zone 1 due to nourishment and harbor-related sediment trapping. As a result, transects 1–200 show positive multidecadal trends.

In contrast,

Figure 5A displays interannual shoreline variability, which is strongly driven by the most recent decade, during which erosional pulses have become more frequent. These recent changes, although noticeable, are not yet long enough to shift the 67-year regression into negative values. However, the WLR, which assigns greater weight to the most recent shoreline positions, already captures this transition towards erosion.

Thus, LRR and WLR are complementary rather than contradictory: LRR reflects the cumulative multidecadal behavior of the system, whereas WLR and the time-series plot highlight the emerging erosional tendency of the last decade.

Marked differences between LRR and WLR are also evident in Zones 2, 3 and 4. In these sectors, LRR integrates the entire 1957–2024 record and therefore reflects multi-decadal behavior dominated by the structural configuration and nourishment history. Conversely, WLR is more sensitive to the last decade, during which erosion has intensified. As a result, WLR tends to show more negative values in the most recent short-term windows, whereas LRR often remains near-stable or mildly accretional.

In Zone 5, the discrepancy is particularly large. The short-term analysis (2015–2024) exhibits an erosion peak of approximately 6 m/year before transect 900, but this signal does not appear in the LRR results (

Figure 4A). This is because LRR dilutes high-magnitude but short-lived events when fitting a regression across the full 67-year dataset. Episodic erosional pulses strongly influence short-term indicators but have limited influence on multi-decadal slopes.

4.2.1. Zone 1: Arenas–Malvarrosa–Patacona

In the long term (1957–2024), this zone shows a clear trend of shoreline accretion, as observed in the LRR graph, with an average of 0.88 m/year. Additionally, it presents positive average values for each of the other parameters: NSM of 58.42 m; SCE of 76.31 m; and WLR of 0.81 m/year. This accretion dynamic could be related to the influence of the port of Valencia, which was built as an artificial port in the early 19th century and underwent several phases of expansion from the late 20th century onwards; in 1980, the dock with the maximum penetration into the sea was built. This structure has acted as a barrier to the transport of sediments predominantly from north to south, favoring the accumulation of sediments to the north of the obstacle [

21,

23,

25].

Recent studies, such as Pagán et al. [

28], confirm this accretion trend in the area. Specifically, the Malvarrosa Beach width has increased from 48 m to 240 m between 1957 and the present day, in response to the port’s effect as a sedimentary barrier.

Despite this trend, the positive evolution has shifted in recent decades. In the medium term (1997–2024), an inversion in the trend is observed, with negative values for EPR (−0.40 m/year) and LRR (−1.47 m/year), suggesting the onset of an erosive phase, which is also confirmed in the 2015–2024 period (mean LRR: −1.43 m/year). This transition has been highlighted in studies such as those by CGAT-UPV. The intensification of sediment loss could be related to the increase in the intensity and frequency of storms, due to the consequences of climate change observed throughout the 21st century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Since the end of the 20th century, there has been an increase in energy and frequency of these extreme phenomena in coastal areas, as a result of the increase in temperature. This process, which is intrinsically erosive, is added to the scarcity of sediments associated with anthropogenic activities that took place during the 20th century (dams, destruction of dune systems, among other) [

23,

24,

25].

4.2.2. Zone 2: Port Saplaya

In the long term (1957–2024), Port Saplaya shows a moderate but steady erosive trend, with average negative values of EPR (−0.25 m/year) and LRR (−0.27 m/year), accompanied by a net coastline loss of −16.15 m (NSM) and a similar rate of shoreline retreat in WLR (−0.23 m/year). This erosive dynamic persists in the medium and short term, with LRR values around −0.44 m/year, suggesting a continuous presence of erosive coastline processes across all time scales.

Despite this, the relatively low NSM and SCE values reflect an apparent stability. According to CGAT-UPV, this may be due to the strong anthropogenic control exerted over this area and the presence of defensive structures, such as groynes, which slow down erosive processes—albeit at the cost of interrupting coastal sediment transport and hindering the natural regeneration of the system.

4.2.3. Zone 3: Pobla de Farnals

In the long term (1957–2024), Pobla de Farnals is characterized by a strong erosive trend, with notably negative values across all analyzed indicators: EPR (−0.71 m/year), LRR (−0.57 m/year), NSM (−43.99 m), and WLR (−0.39 m/year). These data reflect a significant accumulated loss of shoreline in recent decades, making this area one of the most vulnerable stretches of the Valencian coast.

In the medium term (1997–2024), a temporary change in trend is observed, with a positive LRR value (0.13 m/year), suggesting some stabilization or partial recovery of the system during this period. This improvement could be attributed to various factors, such as milder hydrodynamic conditions, targeted interventions, or variations in sediment transport [

5]. However, this recovery is not sustained in the short term (2015–2024), as a pronounced negative EPR (−1.05 m/year) is recorded again, indicating that the vulnerability persists and that positive fluctuations may not be sustainable without structural measures or nourishment works efforts.

According to Sánchez-Arcilla et al. [

42], erosion in the Mediterranean has intensified as a result of the sharp reduction in riverine sediment supply, caused by basin regulation, reforestation, and the construction of dams. This sediment scarcity, worsened by retention in rivers, is one of the key factors identified in the assessment of Pobla de Farnals, classifying it as one of the areas most affected by erosive processes [

25]. Additional factors are the intensive urbanization of the coastline and the lack of effective interventions, such as coastal protection structures or nourishment projects, which have left the coast especially exposed to storms, facilitating a progressive retreat of the shoreline.

In this context, Pobla de Farnals represents a clear case of sedimentary imbalance and anthropogenic pressure, as a result of a domino effect, where the natural dynamics have been profoundly altered without an effective adaptive response [

20]. These coastal structures, despite being an effective short-term solution at the local scale, have negative long-term consequences because, although they can protect a specific area, they alter the natural transport of sediments along the coast. Erosion not only affects the coastal profile but also threatens infrastructures, urban areas, and nearby ecosystems, highlighting the urgent need for integrated planning and specific protective measures.

4.2.4. Zone 4: Puzol

In the overall analysis (1957–2024), this area shows moderate negative values, with an EPR of −0.27 m/year, an LRR of −0.23 m/year, and an NSM of −18.36 m. However, at the medium scale (1997–2024), the EPR becomes positive (0.58 m/year) and the LRR remains stable at 0.04 m/year, suggesting a possible recovery or phase of stability. In the short term (2015–2024), this period of stability persists, with an EPR of 0.65 m/year and an LRR of 0.06 m/year.

These negative values could be attributed to the influence of the Port of Sagunto and the associated urban developments, which disrupt the coastal drift and cause erosive processes in adjacent sectors such as the stretch between Puzol and Massalfassar [

4]. However, stabilization is observed in the medium and short term, which may be related to the strong anthropization of the area, due to the construction of numerous defensive structures and the implementation of nourishment works that help mitigate erosion, such as the one carried out in 2023 by the Puçol City Council [

37].

The CGAT-UPV study also recognizes this recent stabilization, although it warns that the defensive works have induced erosion in other stretches, especially towards the south, highlighting the domino effect of coastal structures and the need to plan coastal interventions in a comprehensive and non-sectoral manner.

4.2.5. Zone 5: Marjal dels Moros

In the long term (1957–2024), it presents very stable values of EPR (−0.004 m/year) and LRR (0.03 m/year), suggesting a relatively balanced coastline, although the values of NSM (−2.37 m) and SCE (33.95 m) indicate some mobility in the coastline. As the period shortens, the dynamics become more regressive, with negative LRR values, both in the medium (−0.52 m/year) and in the short term (−0.53 m/year), and similar WLR values, suggesting an increase in coastline regression.

This regression is mainly influenced by the interruption of the coastal drift generated by the Port of Sagunto. This situation is aggravated by the reduction in fluvial sedimentary contributions, due to the construction of the Regajo reservoir in 1959, which has contributed to the sedimentary imbalance and increased regression on the southern coast of the port [

44]. In addition, the absence of defensive structures directly on the coastline leaves the marsh (Marjal dels Moros) particularly exposed to natural erosion processes. However, the presence of slag from historical dumping by steel companies (Altos Hornos de Sagunto), which encrusts the sediment, and anthropogenic nourishment projects carried out by the Sagunto City Council [

38], mitigated the effects of erosion on this coastal stretch in the medium and short term. Also noteworthy is the action carried out in 2017 to reinforce the protection of the marsh (Marjal dels Moros), with the repair of about 50 m of the defense mote and the restitution of the protective platform by pouring 850 m

3 of boulders from accumulations in nearby breakwaters. Although this intervention did not directly modify the position of the coastline, it did increase the resilience of the system against extreme events [

45].

The CGAT-UPV study coincides in pointing out this area as particularly vulnerable, constituting a representative case to evaluate the natural response of the coastline in the absence of intensive and permanent interventions.

4.3. Coastal Evolution Between the Ports of Sagunto and Valencia in the Mediterranean Context

Overall, the results show a heterogeneous evolution throughout the five analyzed areas, conditioned by both natural and anthropogenic factors. The urbanized areas have a greater presence of infrastructures (seawalls, revetments, groins and breakwaters or nourishment works) that protect and stabilize the coast, while the natural areas are more vulnerable to erosive processes. The comparison of the results obtained with other studies confirms and reinforces the validity of the data obtained, highlighting the importance of carrying out multiscale analyses that allow for observing trends in the coastline over several time scales.

The investigated littoral is bounded by two ports that constitute almost impermeable fixed limits of a large morphological cell [

46]. The cell is divided into small sub-cells because of coastal armoring during the last third of the 20th century, which increases the negative domino effect on the coastline. This model is becoming increasingly common on Mediterranean coasts [

46,

47].

Considering the scarcity of sediments that characterizes Mediterranean beaches [

46], due to anthropogenic causes (reservoirs, destruction of dune systems, among others), it can be observed that the largest positive displacements are usually related to recent coastal nourishment works or take place upstream of a coastal obstacle (e.g., in the northern area of the Port of Valencia). Coastal nourishment works and other protection measures (remodeling or removal of rigid structures, reforestation of seagrass in offshore, sand transfer between different coastal sectors, among others) constitute the main actions to counteract the loss of sediments on Mediterranean beaches since the end of the 20th century. In this context, during the 21st century, coastal defense policies have undergone significant changes compared to the 1960s and 1970s, when protection policies based on coastal armoring were dominant. Both types of measures seek to increase the carrying capacity of beaches in response to fierce demand from the tourism sector. Although they have protected the coast in both cases, the set of measures applied in recent decades show greater respect for the environment.

During the 1960s and 1970s, coastal retreat caused by new structures was counteracted by the gradual installation of groins to expand tourist beaches and/or halt coastal erosion, leading to intense artificialization of the coastline. In the case of the study area, there were 28 groins along 22 km of coastline, in addition to the Port of the Pobla de Farnals. Similar studies also indicate intense occupation in other areas of the Mediterranean [

46,

48,

49,

50]. The sedimentary imbalance produced as a result of coastal armoring is one of the factors that explain the intensification of erosion processes in the study area. Long-term coastal changes (1957–2024) are determined by the interruption of the longitudinal coastal current due to anthropogenic obstacles (specifically, rigid engineering structures) built in the second half of the last century. North of these obstacles, coastal accretion is observed, while south of them, intense coastal retreat is recorded. Coastal armoring, therefore, has a domino effect on other adjacent areas. By altering the natural flow of sediments and wave dynamics, these structures often cause increased erosion in adjacent unprotected sections. This process, known as induced erosion, can trigger a chain of additional interventions along the coastline, exacerbating sediment imbalance and affecting fragile coastal ecosystems such as beaches, dunes and wetlands, which depend on natural processes for their regeneration [

48,

50]. On the other hand, the most negative values, especially in Pobla de Farnals and Puzol, seem to be related to erosion episodes linked to intense storms or downstream of the side of the port. Several studies link the incidence of storms to coastal erosion, especially during the 21st century [

47], which is directly related to current climate change. However, other indirect and recent human actions that may have contributed to coastal erosion in the study area include sea level rise associated with climate change and local factors such as seagrass regression.

Finally, comparing the different time scales and their relationship with the dominant processes allows to conclude that the progressive artificialization of the coastline is key to explaining the long-term evolution of this coastal sector, which adds to the reduced availability of sediment due to the construction of dams and the destruction of dune systems during the last century [

23,

24]. To compensate for erosion and promote tourism, coastal nourishment projects have been carried out, which could make it difficult to analyses the erosion signal in the medium term (1997–2018). The dominant processes in the short term (2015–2024) are storms, which cause coastal regression in all areas. These episodes are becoming increasingly intense, which explains, to a certain extent, why their effects are visible on this time scale. This factor is in addition to those derived from anthropogenic action, which have persisted since the second half of the 20th century. In short, the coastline studied varies over time as a result of sedimentary imbalance caused by both natural dynamics and human interference, with the reduction in river inflows playing a key role. This decrease is mainly due to the construction of reservoirs, the reforestation of basins, and the channeling of rivers [

4,

42]. Therefore, the changes observed in this section should not be understood as an isolated event, but rather as the result of a set of natural processes and human transformations that have been accumulating over decades.

These observed trends warn about the need to act against this type of erosive process, carrying out more effective coastal planning in the context of climate change and sea level rise [

25]. Considering the impact of climate change predicted for the coming decades, coastal protection strategies must be drawn up based on respect for the environment, i.e., on solutions based on nature itself. There is currently widespread sand loss on Mediterranean beaches [

5,

6,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50], which requires sand supply work to be carried out every year to serve the tourism sector. It is therefore necessary to establish better nourishment models that ensure the long-term sustainability of the system. This will reduce the need for structural interventions, which have led to the denaturalization of the coastline in an attempt to curb erosion at the local level.

The influence of climate-related drivers on the study area is supported by quantitative observations from Puertos del Estado [

35]. The monthly mean sea-level record from the REDMAR Valencia 3 tide gauge (1992–2024) shows a rise of approximately 0.17–0.20 m over the last three decades (≈5–6 mm/year). In parallel, monthly current-speed data (2011–2024) indicate a clear increase in nearshore hydrodynamic energy, from typical values of 4–5 cm/s in 2011–2014 to recurrent peaks of 7–10 cm/s after 2020. These trends confirm the measurable intensification of marine forcing, which helps explain the recent acceleration of erosion observed along this coastal segment. Assuming characteristic beach slopes of 1–3%, values commonly reported for dissipative to intermediate Mediterranean sandy beaches, a sea-level anomaly of 0.20 m would correspond to a potential horizontal shoreline displacement of approximately 7–20 m [

51,

52]. This order of magnitude is consistent with the short-term retreat detected in several transects between 2015 and 2024, supporting the interpretation that increased sea level and storminess are contributing drivers of the recent acceleration of erosion.

5. Conclusions

The analyzed indicators (EPR, LRR, NSM, SCE and WLR), obtained using GIS tools such as QGIS and DSAS, have made it possible to quantitatively characterize the evolution of the coastline. The comparison with other study reinforces the reliability of the results and demonstrates the validity of the applied methodology. It is confirmed that the sedimentary imbalance combined with the proliferation of rigid structures has profoundly altered the coastal morphodynamics since 1957.

The multi-temporal analysis of the evolution of the coastline between the Port of Valencia and the Port of Sagunto has shown a coastal dynamic strongly conditioned by human action and natural processes. In the long term (1957–2024), the results show an alternation of areas with clear accumulation, such as zone 1 (Arenas–Malvarrosa–Patacona), and others markedly erosive, such as zone 3 (Pobla de Farnals), reflecting the impact of infrastructures such as ports, which interrupt the longitudinal transport of sediments. At this scale, accretionary processes dominate to the north of these structures, while regressive processes affect the southern sections.

At the medium scale (1997–2024), erosion is more influenced by nourishment works and other punctual works. Even so, the fact that some areas, such as zone 3 (Pobla de Farnals), remain vulnerable indicates that these interventions do not always work in the medium term. In the short term (2015–2024), erosion is the main process in almost the entire stretch, especially after strong storms such as Gloria, which caused significant setbacks in unprotected areas.

In addition, the analysis confirms that areas with greater urban pressure tend to coincide with sections where artificial accretion is observed. However, this pattern may be more closely related to the presence of infrastructures such as ports, which alter the longshore sediment transport and promote accumulation in certain areas. In contrast, more exposed zones with less direct intervention, such as Marjal dels Moros (zone 5), show higher rates of erosion despite having structures like the breakwater from the Altos Hornos, indicating limited protection against erosive processes. These patterns highlight the need to integrate land-use and sediment dynamics into coastal planning.

As mitigating measures to prevent coastal erosion, especially in the context of the sea level rise predicted by the IPCC in the medium term, it is recommended to protect the scarce undeveloped land from future urban development and, in particular, to carry out artificial sand nourishment with a grain size appropriate to the energy of the environment in order to promote its permanence.

Despite the conclusions reached, the positional error of ±1.1 m represents a critical limitation in DSAS-based analyses of coastline changes, as it can obscure small variations and undermine the interpretation of actual trends. While regression-based methods (LRR and WLR) partially reduce this uncertainty and provide more reliable information in the long term, the EPR becomes particularly unreliable when the rate of change approaches the magnitude of the error itself. Therefore, only extended time periods, multiple shoreline dates, and regression approaches provide robust results; any trends close to the error threshold should be interpreted with great caution and should not be considered definitive evidence of erosion or accretion.