Spatial Analysis of Extreme Coastal Water Levels and Dominant Forcing Factors Along the Senegalese Coast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

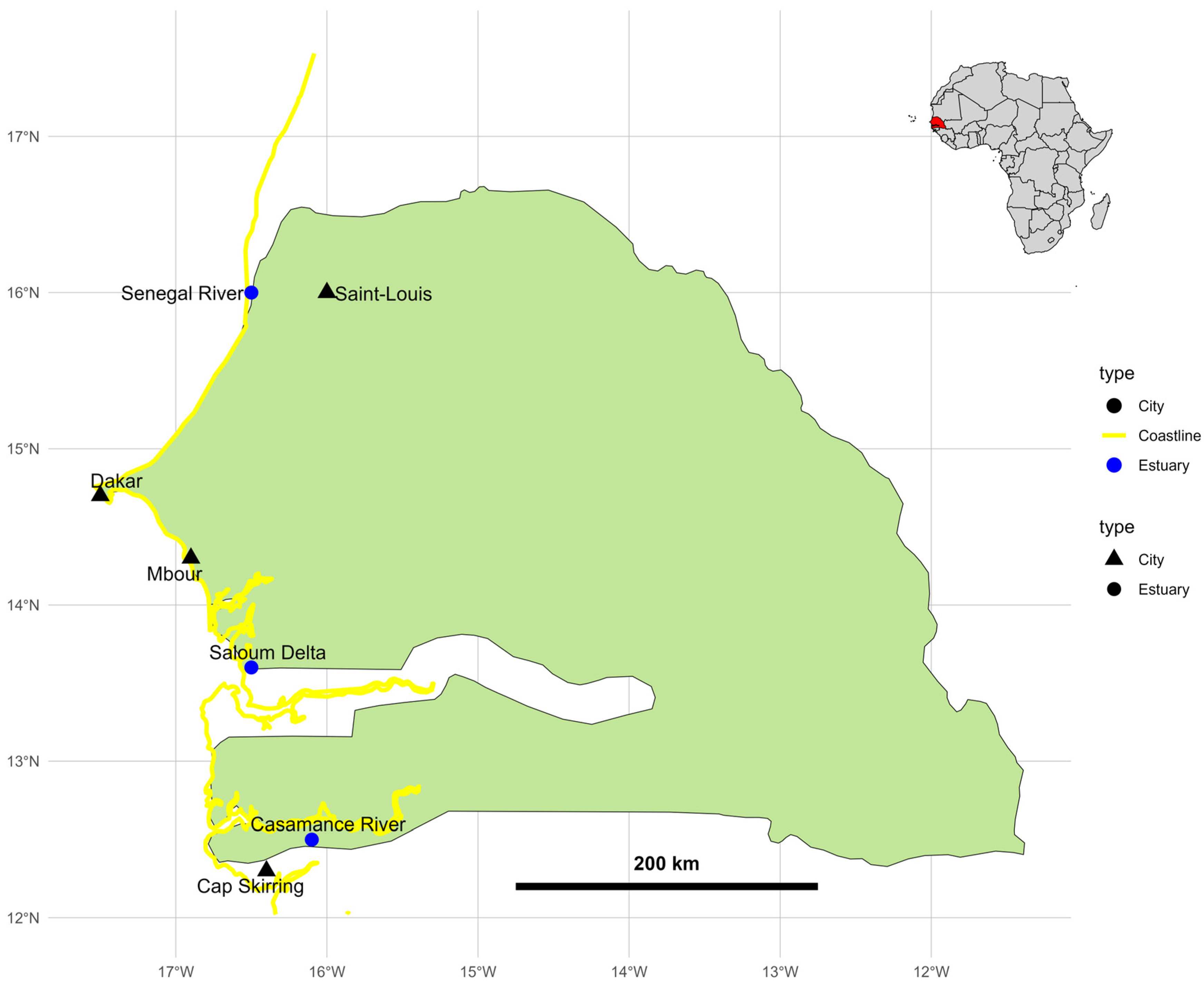

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Hydrodynamic Data

Wave Runup (R)

2.3. Application of the Generalized Pareto Distribution (GPD) Model for the Analysis of ECWL Extreme Values

2.4. Analysis of Trends in Extreme Water Levels

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Factors Controlling Extreme Water Levels

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pérez, F.M.; Miyashita, T.; Shimura, T.; Mori, N. Analysis of historical extreme coastal water level, and Contributors along south American pacific coast. Coast. Eng. Proc. 2024, 38, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulent, J.; Bricheno, L.M.; Green, M.J.; Haigh, I.D.; Lewis, H. Distribution of coastal high water level during extreme events around the UK and Irish coasts. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 2021, 21, 3339–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charuka, B.; Angnuureng, D.B.; Agblorti, S.K. Mapping and assessment of coastal infrastructure for adaptation to coastal erosion along the coast of Ghana. Anthr. Coasts 2023, 61, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankrah, J.; Monteiro, A.; Madureira, H. Shoreline change and coastal erosion in West Africa: A systematic review of research progress and policy recommendation. Geosciences 2023, 13, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luque Söllheim, Á.L.; Scafura, J. Effects of Climate Change on Coastal Erosion and Flooding May 2020 Technical Report in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania, Senegal, and Togo; International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Croitoru, L.; Croitoru, L. The Cost of Coastal Zone Degradation in West Africa: Benin, Côte D’Ivoire, Senegal and Togo; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Bolle, A.; das Neves, L.; De Nocker, L.; Dastgheib, A.; Couderé, K. A methodological framework of quantifying the cost of environmental degradation driven by coastal flooding and erosion: A case study in West Africa. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 54, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghomsi, F.E.K.; Nyberg, B.; Raj, R.P.; Bonaduce, A.; Abiodun, B.J.; Johannessen, O.M. Sea level rise and coastal flooding risks in the Gulf of Guinea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbedemah, S.F.; Frimpong, L.K.; Mensah, S.L.; Amenyogbe, G.K. Sea level rise and climate change adaptation planning in coastal West Africa. In Handbook on Planning and Climate Change Adaptation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, UK, 2025; pp. 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kulp, S.A.; Strauss, B.H. New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, D.A.; Caldwell, R.L.; Brondizio, E.S.; Siani, S.M. Coastal flooding will disproportionately impact people on river deltas. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirezci, E.; Young, I.R.; Ranasinghe, R.; Muis, S.; Nicholls, R.J.; Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J.; Brown, S.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Meyssignac, B.; Hanson, S.E.; Merkens, J.-L.; Fang, J. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, D.; Lichter, M. Social and economic vulnerability of coastal communities to sea-level rise and extreme flooding. Nat. Hazards 2014, 71, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakho, P. Dakar and the coast. Population (Inhabitants) 2007, 3906592, 6. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295921049_Dakar_et_le_littoral?_sg%5B0%5D=LhdOxHAmAFahWKbyeaVm7S73Jb3lB2anh793s1M61BCM5o6yVhh4MqhNTSLVqh-DXR0oum_NECLIGnAlKJt9lt4QJKLswn1psLAFje7P.pQLJV5DfADYi4rTOq1UP-5SCNGjERHl1_qdCJoShdoLW9c_pWx8G3JDqU_CeXaLyNfxCEZzsI9kflw2FHryU3A&_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6ImxvZ2luIiwicGFnZSI6InByb2ZpbGUiLCJwcmV2aW91c1BhZ2UiOiJwcm9maWxlIiwicG9zaXRpb24iOiJwYWdlQ29udGVudCJ9fQ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Sidibé, I. A coastal territory in Senegal’s political, economic, and religious landscape. The case of Ouakam Bay (Dakar). Espace populations sociétés. Space Popul. Soc. 2013, 2013/1–2, 159–176. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/eps/5415 (accessed on 4 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cissé, C.O.T.; Marić, I.; Domazetović, F.; Glavačević, K.; Almar, R. Derivation of coastal erosion susceptibility and socio-economic vulnerability models for sustainable coastal management in Senegal. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.T.; Salameh, E.; Turki, E.I.; Deloffre, J.; Laignel, B. Satellite-based flood mapping of coastal floods: The Senegal River estuary study case. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 138, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouye, I.; Adjoussi, D.P.; Ndione, J.A.; Sall, A. Evaluation of the economic impact of coastal erosion in Dakar region. J. Coast. Res. 2024, 40, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakho, I. Evolution and Hydro-Sedimentary Functioning of the Somone Lagoon, Petite Côte, Senegal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Rouen, Rouen, France, Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar, Dakar, Senegal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SAGNE, P. Morphosedimentary evolution of Mamelles and Ouakam beaches (Dakar, Senegal). Environ. Water Sci. Public Health Territ. Intell. J. 2019, 3, 238–252. [Google Scholar]

- Thior, M.; Sy, A.A.; Cisse, I.; Dieye, E.H.B.; Sane, T.; Ba, B.D.; Descroix, L. A cartographic approach to shoreline evolution in the Casamance estuary. Mappemonde Q. J. Geogr. Imag. Territ. Forms 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yade, D. Coastal erosion and adaptation strategies to climate variability on the Senegalese Petite Côte: The case of the municipalities of Mbour and Saly Portudal (Senegal). Master’s Thesis, Université Assane Seck de Ziguinchor (UASZ), Ziginsauer, Senegal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pouye, I.; Adjoussi, D.P.; Ndione, J.A.; Sall, A.; Adjaho, K.D.; Gomez, M.L.A. Coastline dynamics analysis in dakar region, Senegal from 1990 to 2040. Am. J. Clim. Change 2022, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, S.; Barnard, P.L.; Fletcher, C.H.; Frazer, N.; Erikson, L.; Storlazzi, C.D. Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye, Y.; Ba, K.; Sedrati, M.; Diouf, I.; Diouf, M.B. Coastal Risk Assessment and Management-Related Issues of Sand Spits on the Southern Coast of Senegal. J. Coast. Res. 2025, 113, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, A.; Kane, A. Morphological and hydrodynamic changes in the lower estuary of the Senegal River: Effects on the environment of the breach of the ‘Langue De Barbarie’sand spit in 2003. In The Land/Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone of West and Central Africa; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Melet, A.; Almar, R.; Meyssignac, B. What dominates sea level at the coast: A case study for the Gulf of Guinea. Ocean Dyn. 2016, 66, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, M.; Rohmer, J.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Mentaschi, L.; Le Cozannet, G.; Amores, A. Increased extreme coastal water levels due to the combined action of storm surges and wind waves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 4356–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni-Pérez, F.; Miyashita, T.; Shimura, T.; Mori, N. Analysis of historical extreme coastal water level and its contributors along the South American Pacific coast. Coast. Eng. J. 2025, 67, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayan, S.; Kumar, V.S.; Sajeev, R. Variabilities in the estimate of 100-year return period wave height in the Indian shelf seas. J. Oceanogr. 2024, 80, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, S. Geomorphological Evolution of the Coastline on the Little Coast in Dakar. Master’s Thesis, Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar, Dakar, Senegal, 1982; 117p. [Google Scholar]

- Dramé, A.B.; Burningham, H.; Sall, M. Ocean and Wave Climate Variability in West Africa, and Implications for Alongshore Sediment Transport on the Senegal-Mauritania Coast. J. Coast. Res. 2025, 113, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, I.; Dansokho, M.; Faye, S.; Gueye, K.; Ndiaye, P. Impacts of climate change on the Senegalese coastal zones: Examples of the Cap Vert peninsula and Saloum estuary. Glob. Planet. Change 2010, 72, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang-Diop, I. Coastal Erosion on the Small Senegalese Coast, Using the Example of Rufisque the Example of Rufisque. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Anger, Angers, France, 1996; 285p. [Google Scholar]

- Dee, D.P.; Uppala, S.M.; Simmons, A.J.; Berrisford, P.; Poli, P.; Kobayashi, S.; Andrae, U.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Balsamo, G.; Bauer, P.; et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: Configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 553–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, M.-I.; Faugère, Y.; Taburet, G.; Dupuy, S.; Pelloquin, C.; Ablain, M.; Picot, N. DUACS DT2014: The new multi-mission altimeter data set reprocessed over 20 years. Ocean Sci. 2016, 12, 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marti, F.; Cazenave, A.; Birol, F.; Passaro, M.; Léger, F.; Niño, F.; Almar, R.; Benveniste, J.; Legeais, J.F. Altimetry-based Sea level trends along the coasts of western Africa. Adv. Space Res. 2021, 68, 504–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrere, L.; Lyard, F.H.; Cancet, M.; Guillot, A. Finite Element Solution FES2014, a New Tidal Model–Validation Results and Perspectives for Improvements. In Proceedings of the ESA Living Planet Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, 9–13 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stockdon, H.F.; Holman, R.A.; Howd, P.A.; Sallenger, A.H., Jr. Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coast. Eng. 2006, 53, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, P.; Van Dongeren, A.; Giardino, A.; Vousdoukas, M.; Gaytan-Aguilar, S.; Ranasinghe, R. Global distribution of nearshore slopes with implications for coastal retreat. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almar, R.; Ranasinghe, R.; Bergsma, E.W.J.; Diaz, H.; Melet, A.; Papa, F.; Vousdoukas, M.; Athanasiou, P.; Dada, O.; Almeida, L.P.; et al. A global analysis of extreme coastal water levels with implications for potential coastal overtopping. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Q.; Huang, W.; Yu, R.; Cheng, X. Analysis of extreme water levels on Feiyun River (Rui’an section) based on peaks-over-threshold (POT) model. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruest, B.; Neumeier, U.; Dumont, D.; Lambert, A. Wave climate evaluation in the Gulf of St. Lawrence with a parametric wave model. Ext. Abstr. Coast. Dyn. Coast. Dyn. Res. Emphasizing Pract. Appl. 2013, 1363, 1374. [Google Scholar]

- Northrop, P.J.; Attalides, N.; Jonathan, P. Cross-validatory extreme value threshold selection and uncertainty with application to ocean storm severity. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 2017, 66, 93–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkani, M.; Otmani, H.; Mezouar, K.; Saf, B. Forecasting extreme events and storms and prediction of coastal flooding along microtidal Coast of El Djamila Bay, Algeria. J. Coast. Conserv. 2025, 29, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S.; Bawa, J.; Trenner, L.; Dorazio, P. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values; Springer: London, UK, 2001; Volume 208, p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Serafin, K.A.; Ruggiero, P. Simulating extreme total water levels using a time-dependent, extreme value approach. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2014, 119, 6305–6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkersh, K.; Atabay, S.; Yilmaz, A.G. Extreme Wave Analysis for the Dubai Coast. Hydrology 2022, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, A.; Shu, X.; Guo, J.; Li, H.; Ye, R.; Ren, P. Statistical modeling and dependence analysis for tide level via multivariate extreme value distribution method. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañellas, B.; Orfila, A.; Méndez, F.J.; Menéndez, M.; Gómez-Pujol, L.; Tintoré, J. Application of a POT model to estimate the extreme significant wave height levels around the Balearic Sea (Western Mediterranean). J. Coast. Res. 2007, 50, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazas, F.; Kergadallan, X.; Garat, P.; Hamm, L. Applying POT methods to the Revised Joint Probability Method for determining extreme sea levels. Coast. Eng. 2014, 91, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Lee, O.; Kim, K.; Kim, S. Non-stationary frequency analysis of extreme sea level using POT approach. J. Korean Soc. Hazard Mitig. 2018, 18, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.J. Extreme Value Analysis of Ocean Still Water Levels along the USA East Coast—Case Study (Key West, Florida). Coasts 2023, 34, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Patrotny, D.; Mentaschi, L.; Monioudi, I.N.; Feyen, L. Coastal flood impacts and lost ecosystem services along Europe’s Outermost Regions and Overseas Countries and Territories. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortlock, T.R.; Metters, D.; Soderholm, J.; Maher, J.; Lee, S.B.; Boughton, G.; Stewart, N.; Zavadil, E.; Goodwin, I.D. Extreme water levels, waves and coastal impacts during a severe tropical cyclone in northeastern Australia: A case study for cross-sector data sharing. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 2603–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguli, P.; Merz, B. Extreme coastal water levels exacerbate fluvial flood hazards in Northwestern Europe. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, K.A.; Ruggiero, P.; Stockdon, H.F. The relative contribution of waves, tides, and nontidal residuals to extreme total water levels on US West Coast sandy beaches. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 1839–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.F.; Marani, M. Extreme-coastal-water-level estimation and projection: A comparison of statistical methods. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2022, 22, 1109–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niang, I. Le Sénégal face à l’évolution du littoral: Le cas de la brèche de la langue de Barbarie. Cours Nouv. 2011, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Cissé, C.O.T.; Tano, A.R.; Brempong, E.K.; Taveneau, A.; Almar, R.; Angnuureng, D.B.; Sy, B.A. Compounded influence of extreme coastal water level and subsidence on coastal flooding from satellite showcased at Saint-Louis (Senegal, West Africa). Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 2025, 112, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhoum, P.W. A peninsula in coastal erosion? Dakar, the Senegalese capital city facing the sea level rise in the context of climate change. Environ. Water Sci. Public Health Territ. Intell. J. 2018, 2, 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Nederhoff, K.; Saleh, R.; Tehranirad, B.; Herdman, L.; Erikson, L.; Barnard, P.L.; Van der Wegen, M. Drivers of extreme water levels in a large, urban, high-energy coastal estuary–A case study of the San Francisco Bay. Coast. Eng. 2021, 170, 103984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Sun, S.; Shi, P.; Wang, J.A. Assessment and mapping of potential storm surge impacts on global population and economy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2014, 5, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwer, L.M.; Jonkman, S.N. Global mortality from storm surges is decreasing. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.; Wahl, T.; Cid, A. Data-driven modeling of global storm surges. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, S.; Strobl, E.A. The global long-term effects of storm surge flooding on human settlements in coastal areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 024016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergillos, R.J.; Rodriguez-Delgado, C.; Iglesias, G. Wave farm impacts on coastal flooding under sea-level rise: A case study in southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouakou, M.; Bonou, F.; Gnandi, K.; Djagoua, E.; Idrissou, M.; Abunkudugu, A. Determination of current and future extreme sea levels at the local scale in port-Bouët Bay (Côte d’Ivoire). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissé, C.O.T.; Almar, R.; Youm, J.P.M.; Jolicoeur, S.; Taveneau, A.; Sy, B.A.; Sakho, I.; Sow, B.A.; Dieng, H. Extreme Coastal Water Levels Evolution at Dakar (Senegal, West Africa). Climate 2022, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, P.; Anselme, B.; Thomas, Y.F. L’impact de l’ouverture de la brèche dans la langue de Barbarie à Saint-Louis du Sénégal en 2003: Un changement de nature de l’aléa inondation? Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2010. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/cybergeo/23017 (accessed on 4 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Esteban, M.; Mikami, T.; Fujii, D. Projection of coastal floods in 2050 Jakarta. Urban Clim. 2016, 17, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, W.W.V.; Dusek, G.; Obeysekera, J.T.B.; Marra, J.J. Patterns and Projections of High Tide Flooding Along the US Coastline Using a Common Impact Threshold; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh, K.J.; Wilson, C.; Baptie, B.J.; Cooper, A.; Cresswell, D.; Musson, R.M.W.; Ottemöller, L.; Richardson, S.; Sargeant, S.L. Impact of a Lisbon-type tsunami on the UK coastline and the implications for tsunami propagation over broad continental shelves. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2008, 113. Available online: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2007JC004425 (accessed on 4 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Diouf, A.; Sakho, I.; Sow, B.A.; Deloffre, J.; Seujip, M.S.; Diouf, M.B.; Lafite, R. The Influence of Tidal Distortion on Extreme Water Levels in Casamance Estuary, Senegal. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 48, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, S. Assessing the Impacts of Climate Change in Senegal: A Case Study of Casamance Region. Master’s Thesis, Pan-African University, Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiaye, P.M.; Ogilvie, A.; Bodian, A.; Descroix, L.; Legay, T.; Guillet, R. Hydrological variability of large rivers in West Africa: Gap-filling with Earth observations and daily rainfall-runoff modelling. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 2219–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, B.; Tang, Q. Integrated modeling analysis of estuarine responses to extreme hydrological events and sea-level rise. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 261, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piecuch, C.G.; Bittermann, K.; Kemp, A.C.; Ponte, R.M.; Little, C.M.; Engelhart, S.E.; Lentz, S.J. River-discharge effects on United States Atlantic and Gulf coast sea-level changes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 7729–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, F.; Piecuch, C.G.; Becker, M.; Papa, F.; Raju, S.V.; Khan, J.U.; Ponte, R.M. Impact of continental freshwater runoff on coastal sea level. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 1437–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, A.; Fortes, C.J.; Capitão, R.; Neves, M.D.G.; Moura, T.; Antunes do Carmo, J.S. Wave hydrodynamics around a multi-functional artificial reef at Leirosa. J. Coast. Conserv. 2012, 16, 543–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cissé, C.O.T.; Almar, R.; Ndour, A. Spatial Analysis of Extreme Coastal Water Levels and Dominant Forcing Factors Along the Senegalese Coast. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122342

Cissé COT, Almar R, Ndour A. Spatial Analysis of Extreme Coastal Water Levels and Dominant Forcing Factors Along the Senegalese Coast. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122342

Chicago/Turabian StyleCissé, Cheikh Omar Tidjani, Rafael Almar, and Abdoulaye Ndour. 2025. "Spatial Analysis of Extreme Coastal Water Levels and Dominant Forcing Factors Along the Senegalese Coast" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122342

APA StyleCissé, C. O. T., Almar, R., & Ndour, A. (2025). Spatial Analysis of Extreme Coastal Water Levels and Dominant Forcing Factors Along the Senegalese Coast. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122342