1. Introduction

In underwater environments, robots designed for tasks such as marine exploration, military reconnaissance, and search-and-rescue require accurate navigation to operate effectively. This requirement is particularly critical for autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that operate without a tether, as the exchange of external information is intrinsically constrained unless they surface or employ dedicated underwater communication systems such as acoustic modems. Due to the attenuation of electromagnetic signals in water, absolute positioning based on the global navigation satellite system (GNSS) is practically unavailable, and the application of perception sensors such as light detection and ranging (LiDAR) that provide relatively high rate and high precision information is also limited.

For these reasons, underwater robots typically estimate their position and attitude using a strapdown inertial navigation system (SINS), and mitigate errors by integrating auxiliary sensors such as a Doppler velocity log (DVL), magnetometer (digital compass), or depth sensor. Whether based solely on an inertial measurement unit (IMU) or combined with such aiding sensors in an integrated navigation framework, these systems fundamentally rely on dead-reckoning (DR), in which position, velocity and attitude are estimated by integrating measured or derived motion quantities such as acceleration, velocity, or angular rate [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, due to the nature of integration, errors inevitably accumulate over time, causing the estimate to drift. In particular, initial position and attitude errors propagate through all integration steps. Among these, an initial attitude error misaligns the estimated velocity and acceleration vectors at every step, amplifying estimation errors as the number of integration steps increases. Therefore, a precise initial alignment process to estimate accurate initial attitude is crucial in such navigation systems, and a variety of methods have been proposed to address this challenge.

The initial alignment process generally consists of two stages: coarse alignment and fine alignment. The fine alignment is typically implemented using a Kalman filter, which uses the initial attitude estimated from the coarse alignment phase as a prior and refines it through measurement updates [

5,

6]. The coarse alignment method can be classified into static alignment and in-motion alignment. Static alignment estimates the initial attitude by measuring gravity and the Earth’s rotation rate while the vehicle is stationary. It is suitable when a stable base or long stationary period is feasible. However, most water surface and underwater robots lack a fixed base, are continually affected by currents, and often require rapid deployment or submergence, making static alignment impractical. Consequently, in-motion alignment is predominantly used in field operations [

7].

A representative approach for in-motion alignment is the optimization-based alignment (OBA) method first introduced by Wu et al. [

8]. This method estimates the initial attitude by exploiting recursive estimation based on multiple observations, and subsequent studies have adapted it for underwater vehicles by integrating DVL measurements [

9]. Various improvements have been proposed to enhance the performance of OBA [

10,

11]. However, it still suffers from slow convergence, particularly in the heading direction, and requires dynamic maneuvers to ensure sufficient observability [

8].

To overcome these limitations, multiple studies have used GNSS measurements to improve the initial heading estimation. GNSS-based methods include those that estimate the initial heading using multiple antennas [

12,

13,

14], multiple GNSS-derived velocity vectors [

15], or single-antenna GNSS-derived trajectories [

16]. In addition, several studies have aligned the DR-derived trajectory with the GNSS-derived trajectory based on their similarity to estimate the initial heading [

17,

18]. These similarity-based approaches mitigate issues such as comparatively high system cost, structural complexity, and degraded performance at low speeds, which are commonly associated with the aforementioned approaches. However, such methods require that the GNSS-derived trajectory be sufficiently accurate not only because it serves as a ground-truth reference, but also because the travel distance of the DR trajectory is computed from GNSS measurements. Therefore, real-time kinematic (RTK) or time-differenced carrier phase (TDCP) techniques are typically employed to ensure the necessary precision. Such requirements not only limit the applicability of these methods but also make them unsuitable for marine environments, where multipath effects are prevalent during surface operations.

In contrast, some studies have explored the use of GNSS positions computed via standard point positioning (SPP) together with DR positions for initial heading estimation. These methods do not rely on RTK, TDCP, or differential GNSS (DGPS) corrections. Instead, they estimate the initial heading through multiple GNSS positions acquired over a short period (e.g., about 20 s) with the corresponding DR positions computed by the SINS or the integrated underwater navigation system at the same time instances [

19,

20,

21]. By using multiple discrete position samples rather than a single observation, these approaches can maintain a reasonable level of heading estimation accuracy even when high-precision GNSS solutions are unavailable.

However, these multiple GNSS position-based initial heading alignment (MGPA) approaches have their own limitations. The primary issue is that the error in the initial position affects the performance of the initial heading estimation. Typically, this initial position is defined as the first GNSS position acquired during the alignment segment and serves as the starting point for DR. In prior MGPA studies using SPP-based GNSS, which is less reliable, substantial initial position errors can occur. These errors not only lead to inaccurate initial heading estimates but also introduce a persistent position offset into all subsequent DR positions, even if the initial heading is accurately corrected. In contrast, GNSS/DR trajectory-alignment methods using RTK GNSS fundamentally address this issue by employing precise GNSS positioning, thereby minimizing both the magnitude and uncertainty of the initial position error [

17]. Meanwhile, studies using TDCP technique address this issue by computing precise position increments rather than relying on absolute positions, making the initial heading estimation independent of the initial position error [

15,

18]. Similarly, other studies have mitigated the impact of initial position errors by estimating the initial heading using displacement vectors between consecutive GNSS or DR positions, rather than relying on vectors referenced to the absolute initial position [

22].

Therefore, this paper proposes an iterative initial position correction method designed to mitigate the adverse effects of the error in GNSS-derived initial position within the MGPA process. The core of the proposed method lies in decomposing the coupled 2D optimization problem. We identify orthogonal correction basis vectors in the initial position-error space from the structure of the alignment problem, which effectively decomposes the horizontal position correction into two 1D optimization problems along two orthogonal directions: along one of which position corrections do not affect the heading estimation, and the other that is coupled with the heading estimation. By iteratively applying corrections along this basis, the algorithm efficiently corrects the error in initial position while simultaneously refining the estimated initial heading.

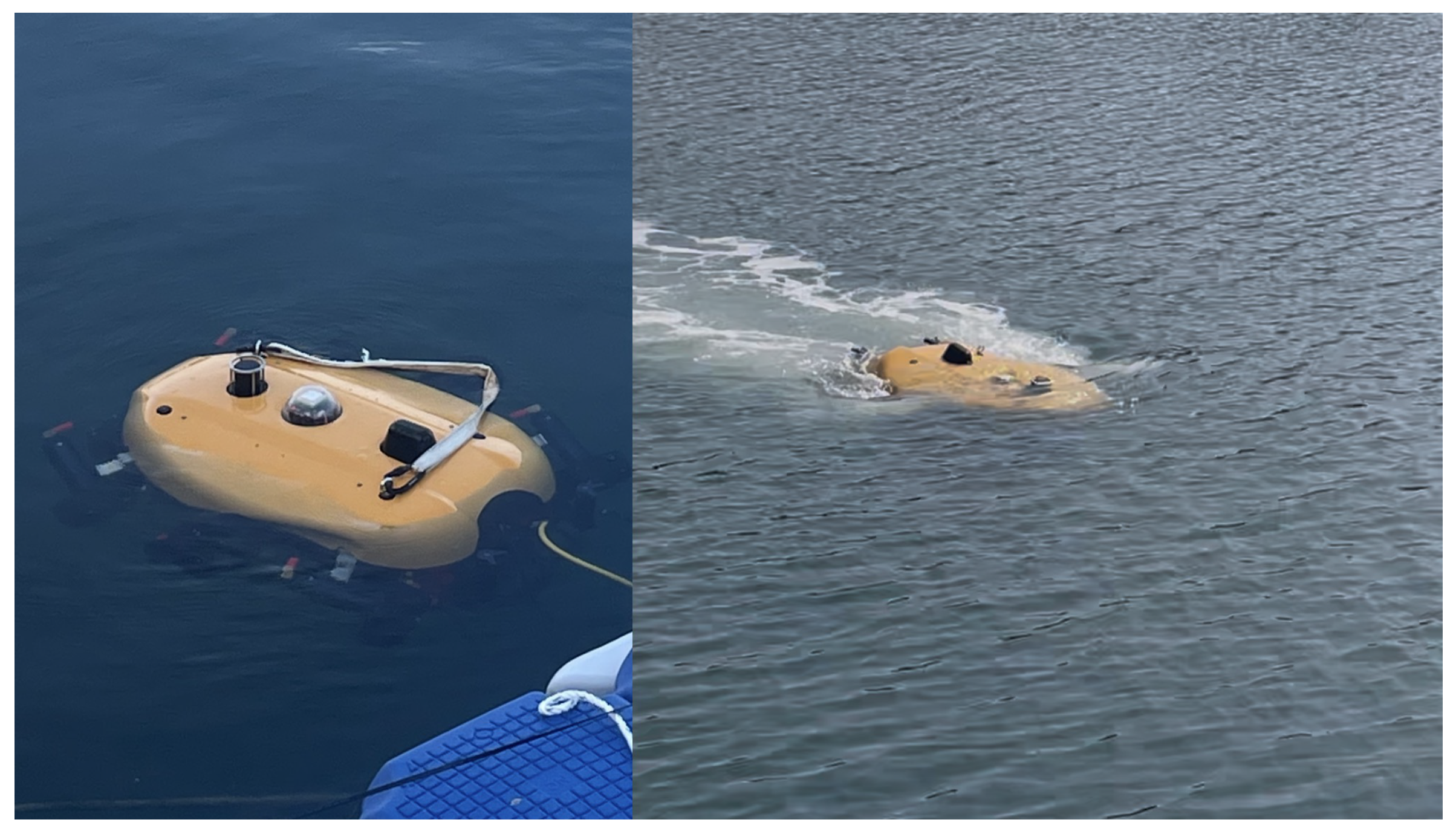

The main contribution of this work is an improved alignment framework that robustly handles the uncertainties of the GNSS-derived initial position. This leads to improved accuracy in the initial heading estimation and corrects the initial position offset, thereby enhancing the overall accuracy of subsequent DR navigation. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted sea trials with an AUV.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the MGPA method and its modified formulation for this study.

Section 3 details the proposed iterative initial position correction method.

Section 4 demonstrates the sea trials and results. Finally, conclusions are drawn in

Section 5.

2. MGPA: Multiple GNSS Position-Based Initial Heading Alignment

An overview of the MGPA approach introduced in prior studies is presented in this section, where the initial heading is estimated by aligning DR positions with the corresponding GNSS positions at matching time instances. The principle and assumptions of MGPA, as well as the procedure for defining GNSS and DR positions within a unified reference frame and estimating the initial heading are described.

2.1. Overview of Multiple GNSS Position-Based Initial Heading Alignment

Figure 1 illustrates the concept of MGPA. The AUV collects GNSS positions and DR positions on the water surface during the alignment process. The DR position is estimated by onboard navigation sensors, while GNSS positions are obtained through SPP. Since the DR position is updated at a much higher rate than GNSS, several DR positions may lie between successive GNSS fixes. Among these the DR positions corresponding to each GNSS epoch are selected for the alignment process.

In the underwater robotic platform considered in both prior studies and this work, the navigation system consists of IMU, DVL, digital compass, and depth sensor. The digital compass provides the initial attitude information, where roll and pitch angles can be estimated with relatively high accuracy. However, the heading measured from the compass includes an offset due to the discrepancy between magnetic north and true north. During DR integration, the attitude is updated by gyro measurements, while the linear velocity is estimated by fusing accelerometer and DVL measurements. In addition, the initial position is provided by GNSS. Therefore, the initial heading is estimated by correcting the measurement error of the compass, using the DR positions and the GNSS positions, where this error includes not only measurement noise but also the compass bias.

2.2. Dead Reckoning Position and GNSS Position Computation

In the MGPA, the initial heading is estimated by aligning DR positions with GNSS positions. To estimate the initial heading using these two position sources, both must be expressed in a common coordinate frame. The local navigation frame defined at the initial position is adopted as the common reference. Thus, both positions are transformed and represented with respect to this fixed frame, where the origin corresponds to the first GNSS position.

Under ideal conditions, when the underwater vehicle’s velocity in the body frame (

b-frame) and its attitude with respect to the navigation frame (

n-frame) are steadily estimated by the SINS, the velocity in the

n-frame required for DR can be obtained as:

where the

n-frame follows the North-East-Down (NED) navigation coordinate frame,

is the direction cosine matrix (DCM) that transforms vectors from the

b-frame to the

n-frame, and

denotes the vehicle’s linear velocity expressed in the

b-frame.

The DR position vector can be calculated by integrating the velocity:

where

and

represent the DR position vectors at the current and initial epochs, and

represents the position increment vector in the

n-frame. The attitude matrix

in Equation (

3) can be decomposed through the chain rule as:

Here,

and

represent the rotation of the

n-frame and

b-frame from the initial time to epoch

t.

is the initial attitude matrix of the

b-frame with respect to the

n-frame. If the alignment process is sufficiently short, the rotation of the navigation frame can be neglected, allowing the following approximation:

where

is the 3 × 3 identity matrix.

Consequently, DR integration can be performed in the fixed

-frame during the initial heading alignment process, and Equations (

2) and (

3) can be rewritten as:

GNSS measurements provide the vehicle’s latitude

, longitude

, and altitude

h in a geodetic coordinate system (WGS-84). To compare them with DR-derived positions, the GNSS position must also be transformed into the

-frame. For short-range and short-time applications, where the Earth curvature can be locally approximated as planar, the GNSS-derived position increment in the

-frame can be expressed as:

The

denote the incremental changes in latitude, longitude, and altitude, respectively. The

and

represent the radii of curvature of the reference ellipsoid along the meridian and the prime vertical at the initial latitude

respectively, and are defined as:

Here,

a and

e denote the semi-major axis and the first eccentricity of the ellipsoid (WGS-84), respectively.

Consequently, the local GNSS position increment in the

-frame can be equivalently expressed as the difference between the instantaneous and initial positions:

2.3. Initial Heading Estimation

The position equations expressed in the initial position navigation frame in

Section 2.2 hold under ideal conditions. However, the estimated motion of the vehicle contains errors that originate from sensor measurements. From Equation (

3), the attitude increment term

is obtained by integrating the angular velocity measured by gyroscopes. In short-duration alignment, these gyro integration errors are relatively small and can be neglected compared to errors in the initial attitude and velocity estimation. For the initial attitude matrix

, as discussed in

Section 2.1, when the digital compass is used, roll and pitch can be estimated with relatively high accuracy. Therefore, only the heading error needs to be considered. To reflect these errors, the DR position increment can be expressed as:

where the hat symbol ^ denotes the variables that include measurement errors, and the subscript

e represents the corresponding error component.

The initial attitude matrix with errors

can be written as:

Here,

denotes the rotation matrix corresponding to the initial heading error

, which can be expressed as:

Similarly, the GNSS position increment containing measurement errors can be written as:

Since heading estimation in MGPA is performed based on spatial relationship between multiple GNSS-DR position pairs, the initial heading misalignment primarily affects the horizontal motion. Therefore, the quantities of interest are the horizontal position increments. The 3D position increment vectors can be reduced to their horizontal components as:

For notational convenience, the horizontal position increments of DR and GNSS over

N epochs are collectively represented in stacked matrix form as:

Each row corresponds to the horizontal increment between the initial and each epoch in the same

-frame.

In prior MGPA studies, the horizontal position increments described above have been used to estimate the initial heading by averaging-type approaches. Various implementations of this approach have been adopted, including weighted circular means and Wiener-filter-based formulations. These methods exploit the fact that the compared position pairs contain measurement noise that can be modeled by certain statistical distributions (e.g., Gaussian distributions). By combining multiple observations, the overall estimate benefits from a noise-averaging effect, thereby improving the reliability of the estimated heading. Among these implementations, the following linear least-squares formulation of the same estimation objective is adopted, which preserves the averaging property of prior approaches while providing an analytically tractable cost function that is compatible with the subsequent optimization process. Consequently, the initial heading correction value can be estimated as:

where

denotes the horizontal rotation matrix corresponding to the heading correction angle

. This least-squares formulation yields the statistical averaging effect in a linearized structure that is suitable for integration of initial position correction will be introduced in

Section 3.

The closed-form solution for the correction angle estimation can be derived as follows:

Here, the estimated correction angle

exhibits nearly the same magnitude as the initial heading error

but with the opposite sign. Applying this correction yields a corrected initial heading close to the true values. For brevity, we refer to this procedure as initial heading estimation in the remainder of the paper.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a method to correct the initial position and thereby improve the performance of in-motion initial heading alignment based on multiple GNSS positions (MGPA) for AUVs. When the initial position is obtained from standard point positioning (SPP) GNSS, it can contain a large error, which not only degrades the heading alignment itself but also introduces an offset into all subsequent dead-reckoning (DR) positions. To overcome this problem, the proposed method iteratively corrects the initial position within the alignment process. The core idea is to decompose the coupled 2D optimization problem by identifying an orthogonal basis in the initial position-error space. The initial position is corrected along these basis directions, and the heading is then estimated from the corrected position.

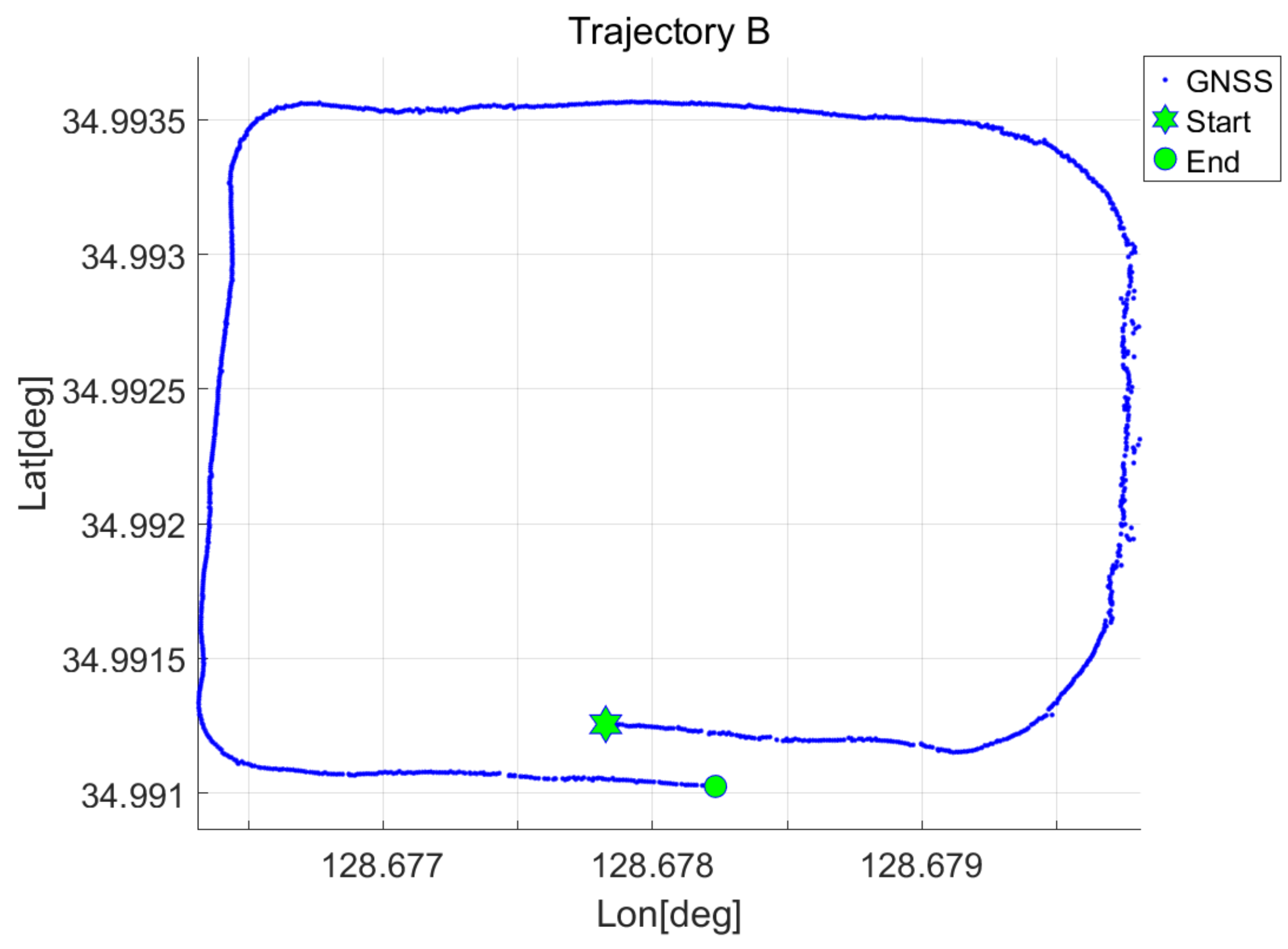

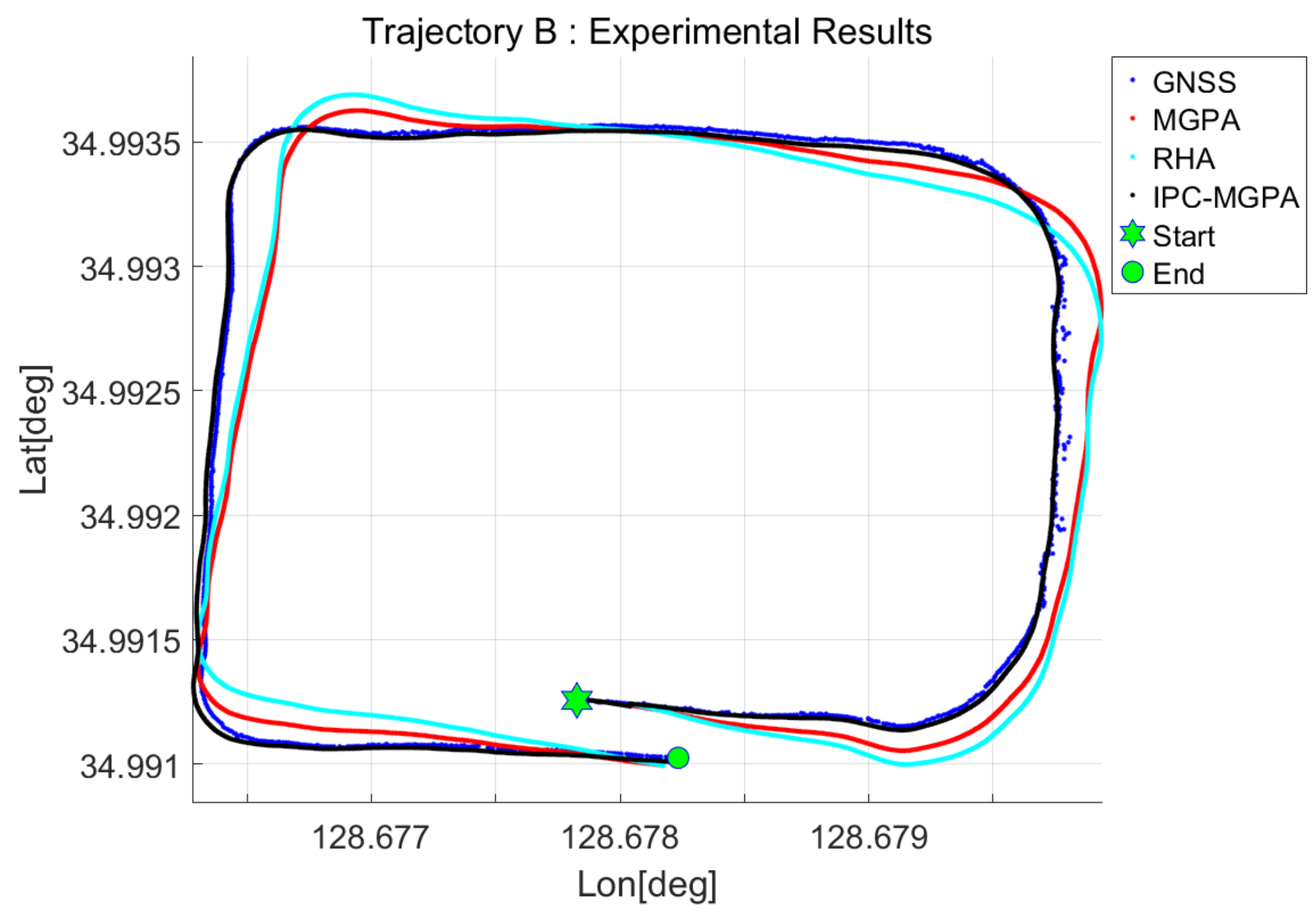

The effectiveness of the proposed method was validated through sea trials involving two trajectories. In both cases, the proposed IPC-MGPA correcting the initial position error led to improved alignment accuracy and reduced DR position error compared with both the MGPA and RHA methods. Furthermore, to confirm that the improvement was not specific to the initial positions of these two paths, we defined multiple alignment segments with lengths of 20, 30, and 40 s within each trajectory and conducted independent experiments. Across these segments, the proposed method showed better performance in most segments and achieved lower mean errors and variances overall. These results demonstrate that compensating for the uncertainty in the GNSS-derived initial position enables more stable estimation of the initial heading.

This study evaluated the performance of the proposed method indirectly through navigation errors, as a high-precision reference heading was not available for direct validation. Future work should therefore include verification of the proposed method in an environment where such reference data can be obtained. Furthermore, the alignment process in this study relied on several assumptions for computational simplicity. Future study will also be necessary to develop alignment methods that account for these additional uncertainty factors.