The Influence of Sampling Hole Size and Layout on Sediment Porewater Sampling Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

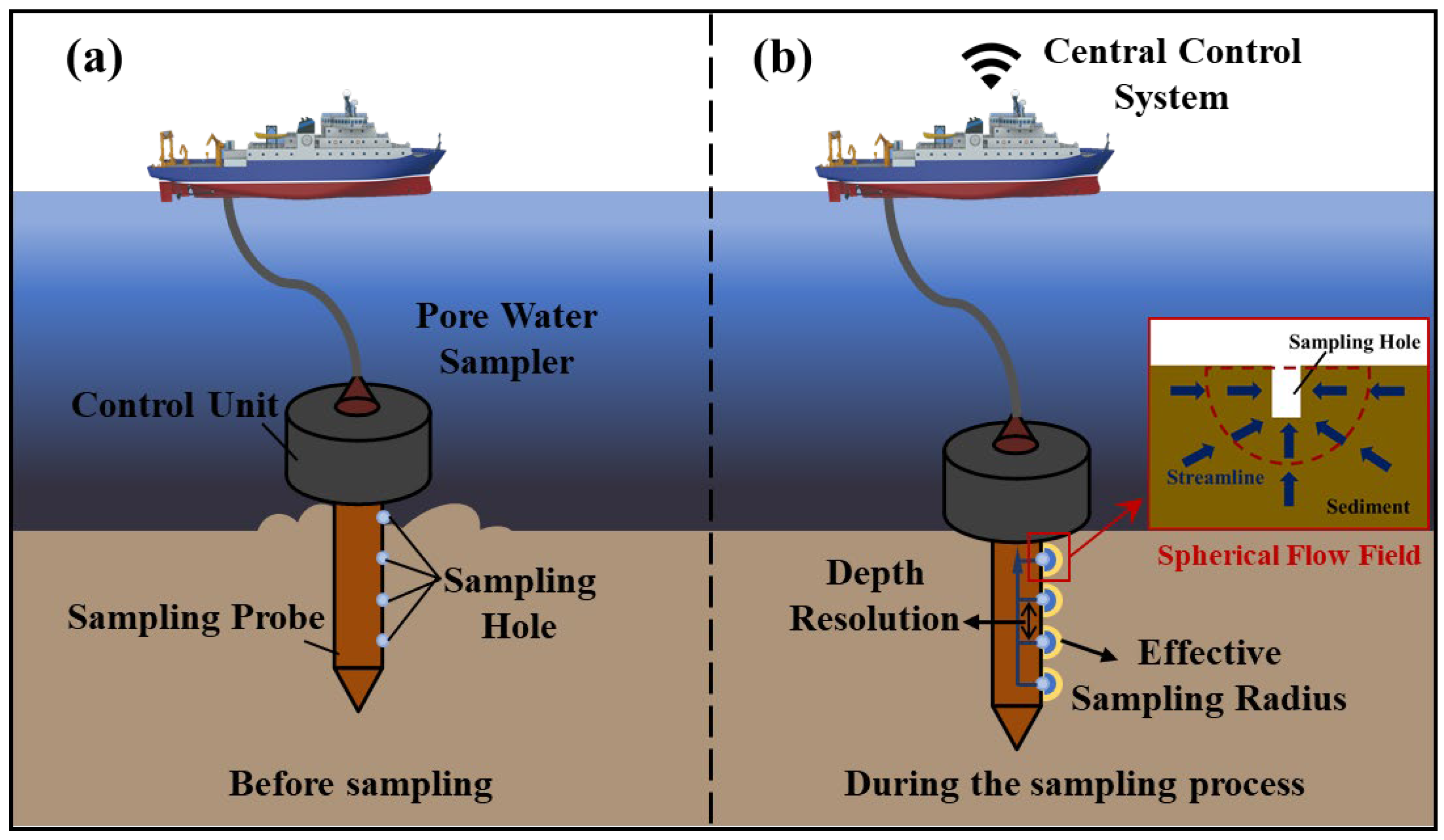

2. Multi-Level Sampling Technology for Pore Water

3. Methods

3.1. Theory of Pore Water Flow in Sediment

3.1.1. Time Flow

3.1.2. Spatial Flow

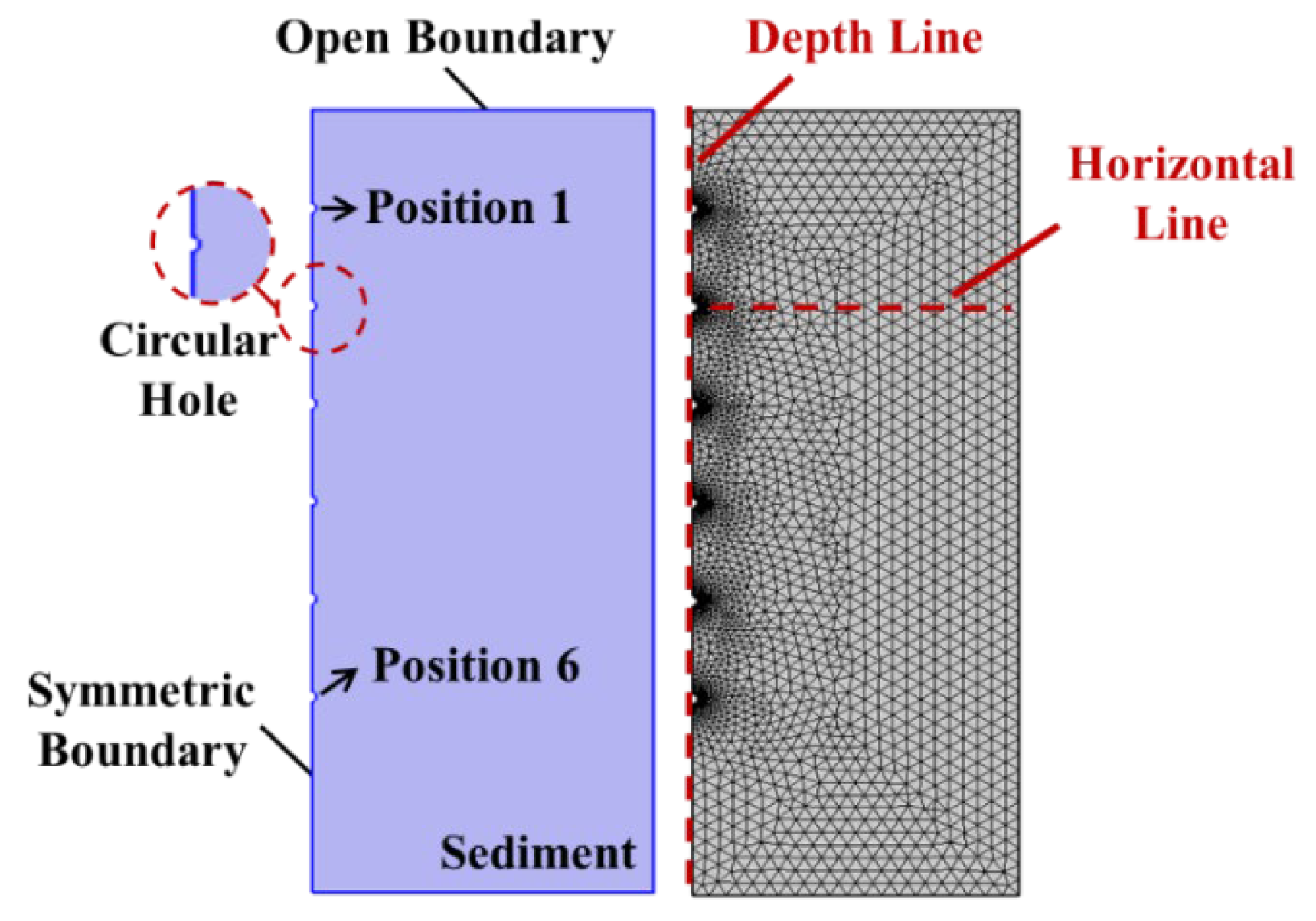

3.2. Numerical Calculation of Multi-Level Pore Water Sampling

3.3. Experiment of Sampling Depth Resolution

3.4. Sea Trial

4. Results

4.1. Effect of Sampling Hole Size on the Flow Field of Sediment

4.2. Analysis of Effective Sampling Range

4.2.1. Consider Sampling Depth and Sampling Interval

4.2.2. Calculation of Effective Sampling Range (ESR)

4.3. Results of Sampling Depth Resolution

4.4. Results of Sea Trial

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. The Applicability of the Sampling Strategy

5.2. Study Limitations

5.3. Future Research Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fiket, Ž.; Fiket, T.; Ivanić, M.; Mikac, N.; Kniewald, G. Pore water geochemistry and diagenesis of estuary sediments—An example of the Zrmanja River estuary (Adriatic coast, Croatia). J. Soils Sediments 2018, 19, 2048–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.-L.; Pape, T.; Schmidt, C.; Yao, H.; Wallmann, K.; Plaza-Faverola, A.; Rae, J.; Lepland, A.; Bünz, S.; Bohrmann, G. Interactions between deep formation fluid and gas hydrate dynamics inferred from pore fluid geochemistry at active pockmarks of the Vestnesa Ridge, west Svalbard margin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 127, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.W.; Yang, C.J. Ocean observation technologies: A review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 33, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.W.; Swart, P.K. Evidence for recrystallization and fluid advection in the Maldives using the sulfur isotopic composition of porewaters, carbonates, and celestine. Chem. Geol. 2022, 609, 121062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Yang, Z.; Boon, N.; Wang, F.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Y. Genomic and enzymatic evidence of acetogenesis by anaerobic methanotrophic archaea. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.A.L.; Schmidt, K.; Achterberg, E.P.; Koschinsky, A. The importance of the soluble and colloidal pools for trace metal cycling in deep-sea pore waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1339772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot-Wasik, A.; Zabiegała, B.; Urbanowicz, M.; Dominiak, E.; Wasik, A.; Namieśnik, J. Advances in passive sampling in environmental studies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 602, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, J.; Yu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y. Advances and development in sampling techniques for marine water resources: A comprehensive review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1365019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.G.; Frickers, T.E. A multilevel in situ pore-water sampler for use in intertidal sediments and laboratory microcosms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1990, 35, 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.B.; Hartl, K.M.; Corbett, D.R.; Swarzenski, P.W.; Cable, J.E. A multi-level pore-water sampler for permeable sediments. J. Sediment. Res. 2003, 73, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.; Dellwig, O.; Kolditz, K.; Freund, H.; Liebezeit, G.; Schnetger, B.; Brumsack, H. In situ pore water sampling in deep intertidal flat sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2007, 5, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risacher, F.F.; Schneider, H.; Drygiannaki, I.; Conder, J.; Pautler, B.G.; Jackson, A.W. A review of peeper passive sampling approaches to measure the availability of inorganics in sediment porewater. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 328, 121581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, Z.; Lazar, B.; Erez, J.; Turchyn, A.V. Comparing Rhizon samplers and centrifugation for pore-water separation in studies of the marine carbonate system in sediments. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2018, 16, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, J.; Tan, X.; Yu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. Design and Testing of a Multi-Channel In-Situ Sampling System for Marine Microorganisms. In Proceedings of the 34th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference, Rhodes, Greece, 16–21 June 2024; p. I-24-035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg-Elverfeldt, J.; Schlüter, M.; Feseker, T.; Kölling, M. Rhizon sampling of porewaters near the sediment-water interface of aquatic systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2005, 3, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owari, S.; Tomaru, H.; Matsumoto, R. Long-term, continuous OsmoSampler results for interstitial waters from an active gas venting site at a shallow gas hydrate field, Umitaka Spur, eastern margin of the Japan Sea. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 104, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, X.; Lin, X.; Fang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. An in-situ portable pore-water sampler for evaluating the vertical distribution in the sediment interface. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2024, 43, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ito, K.; Wu, Z.; Lowry, C.S.; Ii, S.P.L. COMSOL Multiphysics: A Novel Approach to Ground Water Modeling. Groundwater 2009, 47, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, K.; Biastoch, A.; Rüpke, L.; Burwicz, E. Modeling the fate of methane hydrates under global warming. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2015, 29, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitaker, S. Flow in porous media I: A theoretical derivation of Darcy’s law. Transp. Porous Media 1986, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorduijn, S.L.; Harrington, G.A.; Cook, P.G. The representative stream length for estimating surface water–groundwater exchange using Darcy’s Law. J. Hydrol. 2014, 513, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.G.; Miller, C.T. Examination of Darcy’s law for flow in porous media with variable porosity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 5895–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Li, G.; Huang, S.; Li, C. Physical properties of sediments on the Northern Continental Shelf of the South China Sea. Mar. Georesources Geotechnol. 2006, 24, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisitzin, A.P.; Politova, N.V.; Shevchenko, V.P. Progress of marine geology in the reports at the 17th International Scientific Conference (School) “Geology of Seas and Oceans”. Oceanology 2008, 48, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pan, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, P.; Li, Q.; He, Y.; Li, Y. Experimental study on the effect of hydrate reformation on gas permeability of marine sediments. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 108, 104849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, X.; Wu, D.; He, Y.; Li, Q.; Song, Y. Hydrate-bearing sediment of the South China Sea: Microstructure and mechanical characteristics. Eng. Geol. 2022, 307, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Chen, J. The Influence of Sampling Hole Size and Layout on Sediment Porewater Sampling Strategies. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122335

Wang Y, Chen J. The Influence of Sampling Hole Size and Layout on Sediment Porewater Sampling Strategies. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122335

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ying, and Jiawang Chen. 2025. "The Influence of Sampling Hole Size and Layout on Sediment Porewater Sampling Strategies" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122335

APA StyleWang, Y., & Chen, J. (2025). The Influence of Sampling Hole Size and Layout on Sediment Porewater Sampling Strategies. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122335