1. Introduction

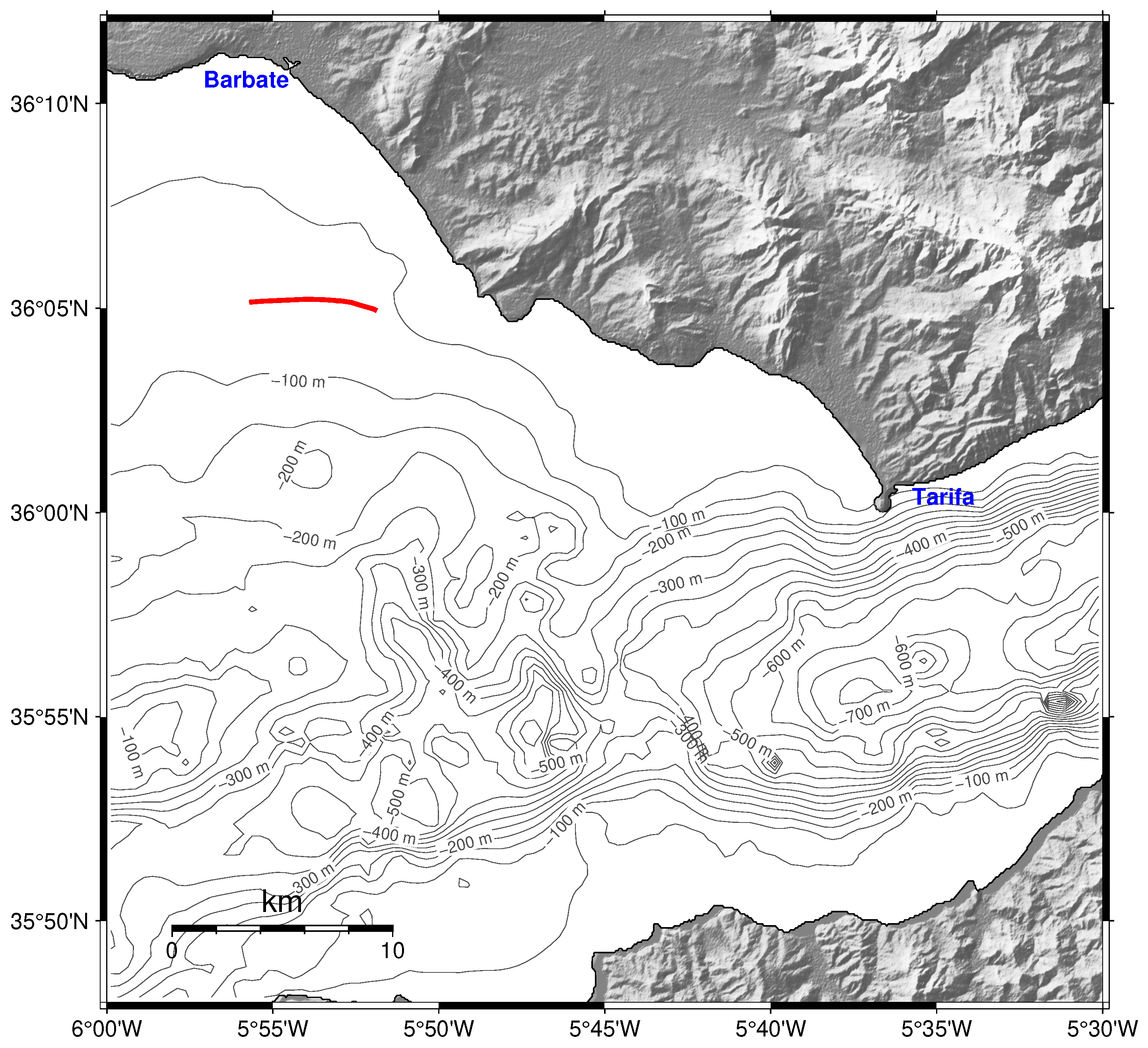

As the sole natural gateway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, the Strait of Gibraltar (

Figure 1) constitutes an obligatory corridor for marine fauna migrating or dispersing between these two basins. The earliest descriptions of marine fauna in the Strait naturally focused on cetaceans, as these large and conspicuous animals were the most evident representatives of marine megafauna observed by early coastal communities and navigators. Archaeological findings of fin whale remains on both shores of the Strait, dated between 1350 and 2150 yr BP, provide the first direct evidence of their long-standing presence in the region [

1]. Subsequent systematic records emerged during the nineteenth century, when American whaling vessels reported numerous fin whale sightings in the Gulf of Cádiz and within the Strait itself, followed by the onset of intensive commercial exploitation in the early twentieth century [

2,

3]. In that sense, the Strait of Gibraltar hosts a remarkable diversity of cetaceans, encompassing both resident and migratory species such as common (

Delphinus delphis), striped (

Stenella coeruleoalba), and bottlenose dolphins (

Tursiops truncatus), long-finned pilot whales (

Globicephala melas), Cuvier’s beaked whales (

Ziphius cavirostris), killer whales (

O. orca), fin whales (

B. physalus) and sperm whales (

Physeter macrocephalus), with occasional records of humpback whales (

Megaptera novaeangliae) and harbour porpoises (

Phocoena phocoena) (See review at [

4]).

Acoustic monitoring has become an increasingly valuable tool for investigating the presence and movements of vocal marine species [

5,

6,

7]. Although such datasets are limited to acoustically active individuals, they offer notable advantages over traditional observation methods, providing a non-invasive means to study animal distribution and behaviour [

8]. Furthermore, acoustic instruments can operate continuously over extended periods, enabling data collection across all seasons, weather conditions, and diel cycles.

Killer whales are distributed throughout all the world’s oceans [

9], exhibiting pronounced differences in diet, behaviour, morphology, and genetic composition among populations [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Orcas produce three main categories of acoustic signals—whistles, echolocation clicks and pulsed calls—the latter comprising rapidly repeated broadband pulses that generate frequency-modulated harmonic structures and sidebands, forming the stereotyped calls [

14]. Their vocal repertoire is believed to be socially learned rather than genetically encoded [

15,

16,

17,

18], resulting in the emergence of culturally transmitted call dialects that are characteristic of particular ecotypes. Such dialects have been most extensively described in the well-studied resident, transient, and offshore ecotypes from British Columbia and Washington State, and also in the southern Alaska and eastern Kamchatka residents where groups share distinct repertoires of stereotyped calls [

16,

17,

19].

In the North Atlantic, several populations also exhibit distinct acoustic signatures associated with geographic isolation and feeding ecology. Acoustic studies across the northeastern Atlantic indicate that the call repertoire of Icelandic killer whales differs markedly from that of Norwegian populations, yet shows partial overlap with individuals recorded around Shetland, UK [

20,

21,

22], consistent with photo-identification and genetic evidence of occasional connectivity among these regions [

23,

24,

25].

Despite more than three decades of continuous monitoring through dedicated photo-identification studies [

26], no descriptions of the acoustic dialects of the Iberian killer whale subpopulation have yet been published. Previous passive acoustic monitoring efforts in the Strait of Gibraltar and adjacent waters have primarily focused on fin whales, aiming to describe population identity, migratory behaviour, and the acoustic differentiation between Mediterranean and North Atlantic individuals [

27]. Other studies have concentrated on characterising underwater noise levels and assessing the contribution of anthropogenic sources to the regional soundscape, with emphasis on the intense maritime traffic and its potential ecological impacts [

4]. The lack of documented vocal data for orcas in the Strait of Gibraltar stands in marked contrast to the wealth of photo-identification, genetic, and ecological information already available for this population [

26]. Analyses based on mitochondrial DNA, microsatellite loci, and other biochemical markers demonstrate that the killer whales inhabiting the Strait constitute a genetically and demographically distinct subpopulation within the broader Northeast Atlantic assemblage [

12,

26,

28]. No confirmed sightings of Iberian orcas have been recorded beyond the Alboran Sea, and none of the identified individuals have been matched with catalogues of resident populations elsewhere in the Northeast Atlantic [

29]. Long-term monitoring between 2011 and 2023 confirmed that the Iberian killer whale subpopulation remains demographically isolated, with an estimated abundance of 37 individuals [

26]. Although calf survival rates have improved relative to pre-2011 estimates, adult survival—particularly among females—has declined, resulting in an overall stable but non-recovering population with a growth rate close to zero. Reproductive rates remain low, with a mean interbirth interval of approximately 8.3 years, and most births occur during summer and autumn. Genetic comparisons indicate historical but limited connectivity with killer whales from the Canary Islands, which differ in mitochondrial haplotypes, stable isotope signatures, and contaminant profiles [

12,

30,

31]. These updated demographic data confirm that the killer whales inhabiting the Strait of Gibraltar and the wider Iberian Atlantic margin constitute a geographically, genetically, and demographically isolated subpopulation, distributed along the Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula from the Strait of Gibraltar to the south of France [

26]. Despite this extended range, concerns about their conservation status persist, with low reproductive output and limited recruitment constraining population demographics. Moreover, although their ecology, distribution, and demographic parameters have been extensively characterised, the acoustic behaviour and potential dialectal structure of this subpopulation remain entirely undescribed, representing a major gap in understanding of their social and cultural organisation [

32].

Given the ecological significance and isolation of the Iberian killer whale subpopulation, a preliminary exploratory study was designed to evaluate the feasibility of employing drifting passive acoustic buoys to monitor cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar. The aim was to obtain recordings suitable for characterising the vocal repertoire of this population to assess its potential dialectal structure and simultaneously monitor the presence and acoustic behaviour of other cetacean species inhabiting the area. Additionally, this approach offers an opportunity to obtain more details on the components of the regional soundscape.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site and Data Collection

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow and shallow seaway linking the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, extending roughly 60 km in length and narrowing to 14 km at its minimum width (

Figure 1). Its complex bathymetry, dominated by the Camarinal Sill at approximately 300 m depth, governs a persistent two-layer circulation characterised by a surface inflow of relatively low saline Atlantic water and a compensatory deep outflow of denser, saltier Mediterranean water [

33]. These opposing fluxes are separated by a sharp interface that shoals eastward from about 180 m to 100 m within the strait, where tides and topographic constraints induce strong internal waves, hydraulic jumps and mixing processes [

34]. Such hydrodynamic variability, modulated by the interaction of barotropic tides and density gradients, plays a central role in regulating nutrient fluxes and biological productivity, enhancing phytoplankton growth particularly along the northern and eastern sectors where upwelling and interface oscillations are most intense [

34].

The experimental protocol consisted of identifying a group of killer whales, releasing the drifting acoustic buoy equipped with the SoundTrap ST400 recorder (Ocean Instruments, Auckland, New Zealand) into the water, and allowing it to drift freely while the research vessel followed the animals to know their position and movements and collect data on their activities opportunistically. At the end of each trial, the buoy was to be retrieved before returning to port. The field experiment was conducted during the final week of May 2025 in the Strait of Gibraltar, with daily operations departing from Barbate Harbour (Cádiz, Spain). The objective was to locate groups of Iberian Orcas to deploy the drifting acoustic buoy in proximity to active individuals. Searches were carried out each day with the support of local vessels operating in the area. However, adverse weather conditions and the elusive nature of the species resulted in several aborted or unsuccessful attempts.

A custom-designed drifting acoustic buoy system was developed and deployed in the Strait of Gibraltar to evaluate the feasibility of passive acoustic monitoring under local oceanographic and navigational conditions. The system comprised a compact surface buoy equipped with two independent SPOT Trace® satellite tracking devices (Globalstar, Covington, LA, USA) to ensure continuous geolocation and facilitate retrieval. Each SPOT Trace unit provided real-time positional updates through the SPOT Mapping platform, enabling live monitoring of the buoy’s drift trajectory via a mobile application and computer interface. This redundancy minimised the risk of signal loss and enhanced the reliability of position tracking under variable sea states.

A SoundTrap ST400 recorder (Ocean Instruments, Auckland, New Zealand) was secured to the drifting buoy via a 5 m nylon line, such that the device floated at approximately 5 m depth, oriented facing downwards to reduce surface-generated noise while allowing free drift with prevailing surface currents. The ST400 was configured for continuous recording at 192 kHz, thereby capturing underwater acoustic activity, including biological, geophysical, and anthropogenic sources. The acoustic environment was characterised using the ST400, which stored data internally in uncompressed WAV format with a nominal sensitivity accuracy of across a calibrated frequency band of 20–60,000 Hz; factory end-to-end system sensitivity values were applied for all calibrations.

2.2. Data Analysis

To characterise the acoustic environment during the experiment, power spectral density (PSD) analyses were conducted using a custom Python script developed for this study. The script computed an integrated power spectrum for the entire recording period by segmenting the acoustic data into one-minute intervals and calculating percentile-based PSD distributions for each segment. The spectral levels were expressed in decibels (dB re 1 µPa2 Hz−1) and averaged across the full frequency range to obtain representative noise statistics.

In addition to the PSD, a long-term spectrogram was generated to provide a comprehensive visual representation of the acoustic activity recorded throughout the entire experiment. The spectrogram was computed using a custom Python (version 3.12.2) routine based on the matplotlib (version 3.9.2) and numpy (version 1.26.4) libraries, with data segmented into consecutive analysis windows to preserve both temporal and frequency resolution. The analysis covered the full bandwidth of the SoundTrap ST400 recorder (0–96 kHz), enabling the detection of a wide range of acoustic sources.

Acoustic data were analysed through detailed visual inspection using Audacity (version 2.4.2; Audacity Team, 2020), employing a multiple-view configuration that displayed both the waveform and the corresponding spectrogram to facilitate signal discrimination. Spectrograms were computed using a 4096-point fast Fourier transform (FFT) with a Hanning window and 50% overlap, allowing adequate temporal and spectral resolution across a broad frequency range.

Spectrograms used to describe and illustrate orca vocalisations were generated using a custom Python script developed for this study. The script computed the short-time Fourier transforms (STFT) of the audio files recorded by the SoundTrap ST400. Orca pulsed calls were identified within the 1–10 kHz frequency band based on their distinctive pulsed and frequency-modulated patterns [

10]. When broadband impulse-like signals were detected in the spectrogram, typically associated with odontocete echolocation clicks, the corresponding waveform was examined in detail to assess its fine-scale temporal structure. This inspection aimed to verify the presence of multi-pulse click sequences with inter-pulse intervals (IPI) consistent with the model proposed by Norris and Harvey [

35], thereby confirming their attribution to sperm whales (

P. macrocephalus). For low-frequency baleen whale vocalisations, the waveform segments showing tonal or rhythmic oscillations were further analysed in low-frequency spectrograms (0–200 Hz) to confirm the presence of concentrated acoustic energy in the expected bands, typical of fin whale and other mysticete calls [

36,

37]. This combined time–frequency visual analysis ensured robust identification of the main cetacean sound types in the recordings.

3. Results

On 26 May 2025, a group of 6–8 killer whales was successfully located at 17:28 UTC, approximately 8 nautical miles south of Barbate (

Figure 1). The buoy was deployed at that time and retrieved at 20:24 UTC. Shortly after deployment, the whales were observed interacting with a sailing vessel and remained in the vicinity for approximately 15 min before dispersing. A subgroup of 4 individuals moved westward and was subsequently followed by the research vessel, where several feeding events were observed, confirmed by the presence of bluefin tuna (

Thunnus thynnus) remains floating at the surface between 10 and 15 nautical miles west of the drifting buoy. Reports from other vessels operating in the area indicated the presence of additional killer whale groups nearby, although no information on their number or behaviour was provided. During the observation period, the buoy drifted approximately 4 nautical miles eastward and was successfully recovered during the return transit to Barbate Harbour.

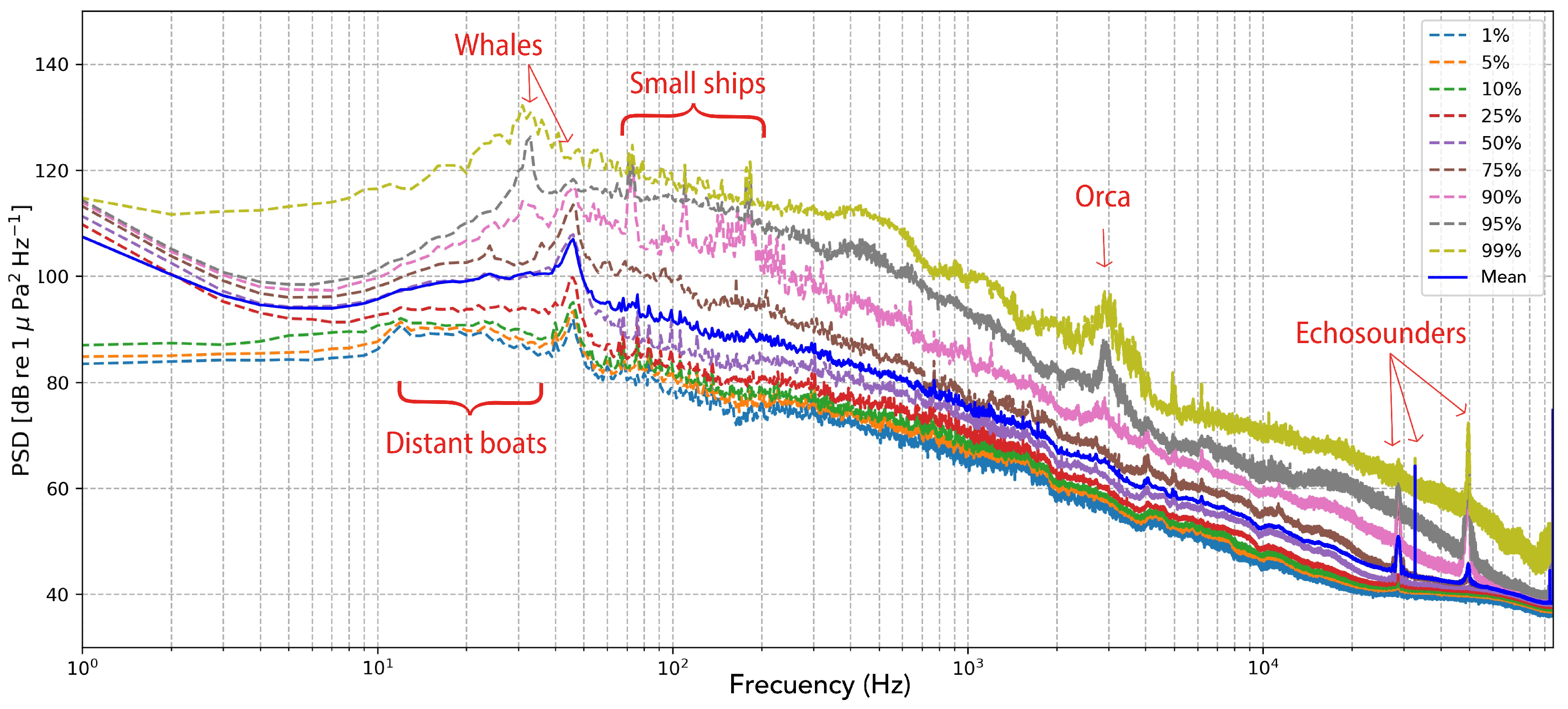

The resulting integrated spectra were plotted as percentile curves (1st–99th) together with the mean PSD (

Figure 2), providing an overview of the temporal and spectral variability throughout the drifting experiment. The power spectral distribution revealed broad low-frequency peaks between 30 and 50 Hz, which were consistently present across all PSD percentiles and are therefore interpreted as a pervasive biological component of the soundscape, likely produced by large marine fauna. Additionally, the PSD curves exhibited a general elevation of background energy between 10 and 60 Hz, compatible with the continuous passage of large commercial vessels through the Strait. Although this low-frequency energy was not sufficient to mask the biological sounds, it was consistently present across the entire recording, raising the overall spectral baseline in that range, as clearly visible even in the lowest percentiles of the PSD plot. In contrast, narrower peaks between 70 and 110 Hz appeared only above the 90th percentile, suggesting intermittent anthropogenic sources such as small vessel engines sailing relatively closer to the buoy. Similarly, acoustic energy within the 2–4 kHz band—corresponding to killer whale pulsed sounds—was only detectable above the 90th percentile, indicating that orca vocalisations were occasional rather than continuous during the drift. Conversely, tonal energy in the frequency range associated with echosounder emissions was evident in more than half of the temporal segments, highlighting the persistent presence of these high-frequency anthropogenic signals within the regional soundscape.

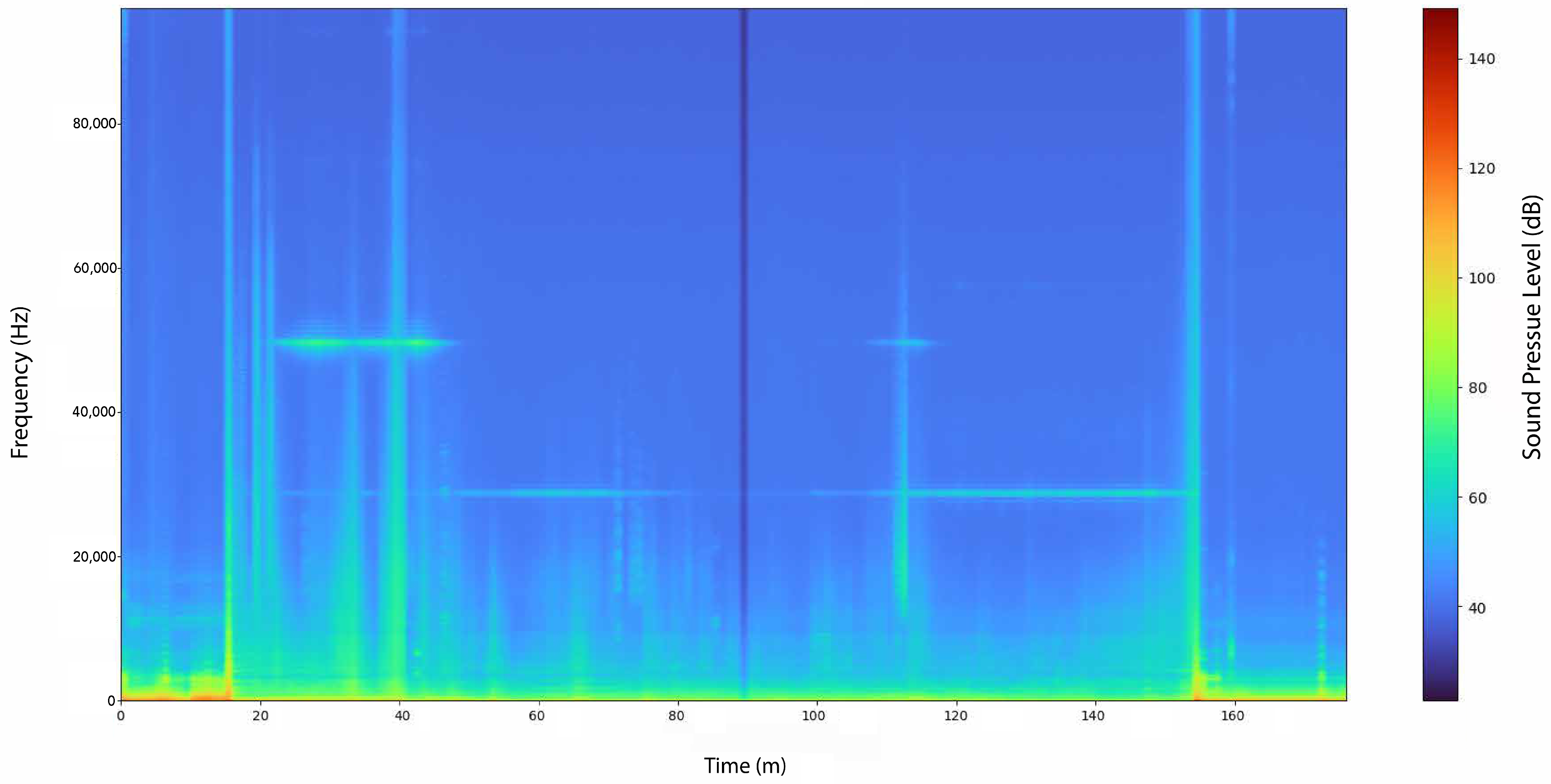

Figure 3 provides an overview of the acoustic data collected during the drifting period, presenting a time–frequency representation used to analyze sound events across the entire experiment in the frequency domain. The moment of buoy deployment is clearly visible around minute 17, followed by continuous acoustic activity until its recovery at approximately minute 155. Horizontal narrow-band lines at 30 kHz and 50 kHz correspond to persistent echosounder emissions, indicating the near-constant presence of active sonar systems in the area. In contrast, vertical broadband features represent transient acoustic events, typically associated with vessels passing in close proximity to the drifting buoy. These vessel-related signatures (e.g., at minutes 35, 40 and 155) exhibit strong low-frequency energy together with broadband vertical streaks. Several discontinuous vertical traces also display harmonic structures characteristic of orca pulsed vocalisations (e.g., around minutes 42, 45 and 75). By comparison, the short, high-energy vertical lines observed near minute 115 are consistent with odontocete echolocation clicks, which lack any low-frequency component and appear exclusively as brief broadband impulses above 10 kHz, thereby allowing for their clear distinction from vessel noise.

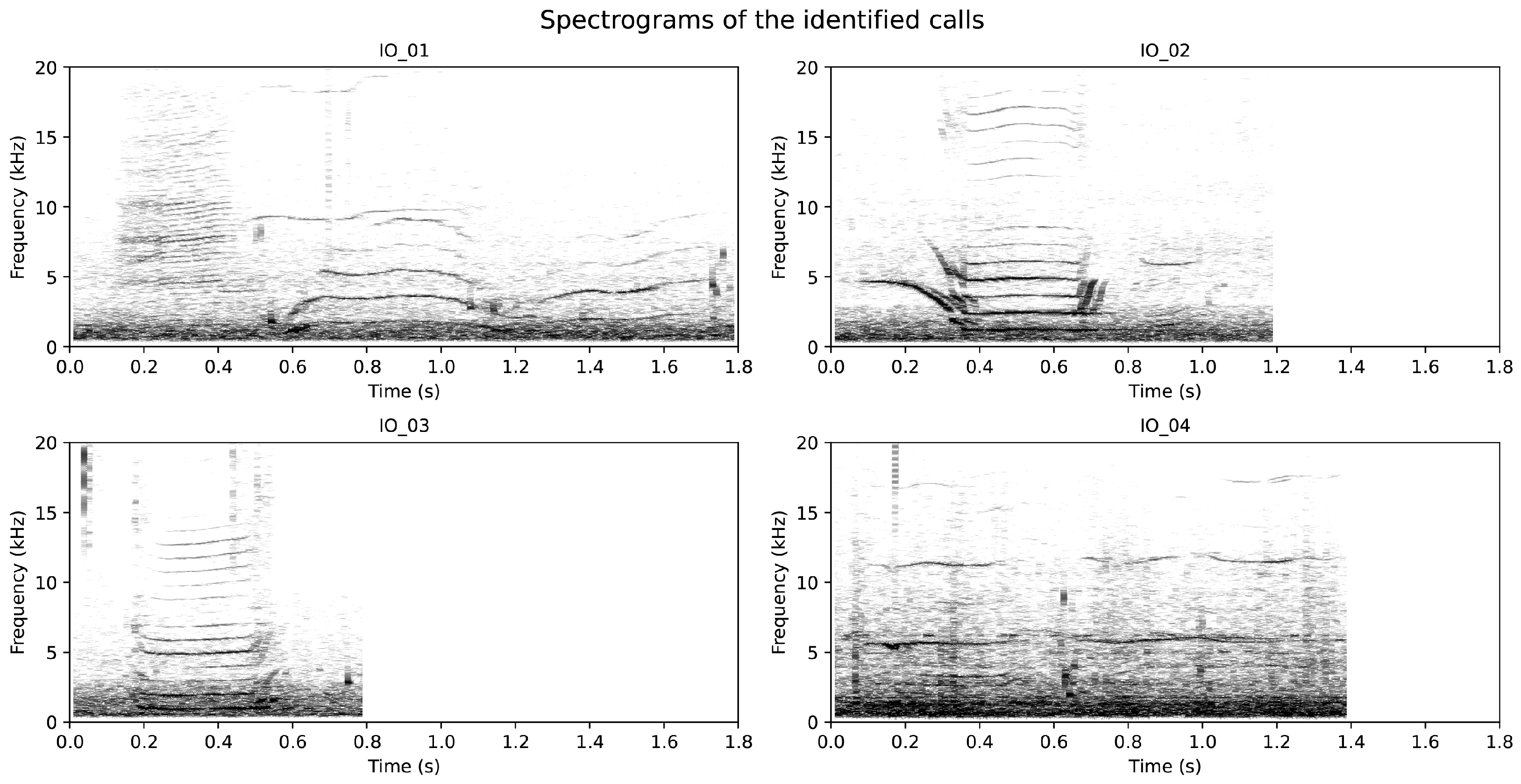

A detailed analysis of the acoustic recordings obtained during the drifting deployment revealed a total of 85 killer whale pulsed calls. Of these, 42 calls exhibited sufficient signal-to-noise ratio and structural consistency to be classified into four distinct call types based on the visual similarity of their spectrographic patterns (

Figure 4). These call types were designated as the Iberian Orca (IO) series: IO_01 (22 calls), IO_02 (10 calls), IO_03 (6 calls), and IO_04 (4 calls). Many calls displayed the characteristic dual-component structure typical of killer whale vocalisations, including clearly defined low-frequency (LFC) and high-frequency components (HFCs), and in several instances, subtle sideband structures (SBI) [

35]. However, given the small number of calls per class and the exploratory nature of the dataset, a quantitative analysis of sidebands—such as computation of the Sideband Index (SBI)—was not attempted. Instead, the recurring temporal and spectral features observed visually provided a robust basis for classifying these calls as discrete acoustic units within the constraints of this short-duration deployment.

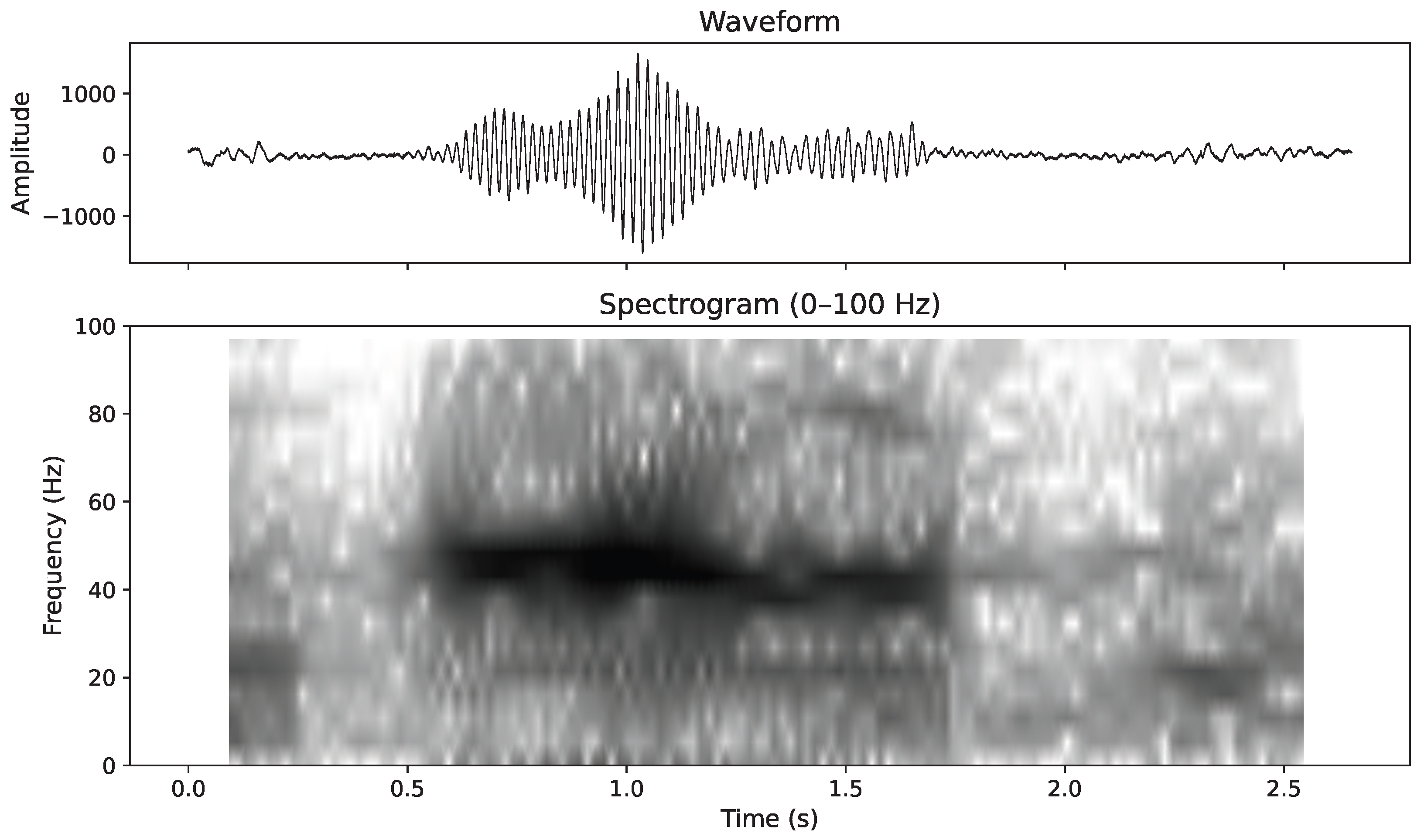

The analysis of the low-frequency band (<100 Hz) revealed a total of 281 discrete acoustic events characterised by short tonal emissions of less than one second in duration, with peak energy concentrated between 40 and 50 Hz (

Figure 5). These low-frequency signals, consistent with the frequency range of tonal emissions produced by several baleen whale species, did not occur in a regular temporal sequence and showed a marked concentration during the initial portion of the drifting period. A total of 209 events were detected within the first hour, followed by 72 in the second hour. These low-frequency tonal events were completely separate from the 85 killer whale pulsed calls described earlier. In addition, the recordings contained sporadic detections of sperm whale clicks and several mid-frequency whistles consistent with those produced by delphinids or long-finned pilot whales (

G. melas); these mid- and high-frequency sounds were not included in the count of 281 low-frequency events.

4. Discussion

The acoustic environment described in this study closely aligns with the soundscape previously described for the Strait of Gibraltar by Pérez Tadeo and O’Brien [

4]. In both investigations, the dominant contributors to the regional acoustic energy were low-frequency bands associated with intense maritime traffic, particularly between 63 Hz and 125 Hz, consistent with the continuous noise produced by commercial shipping and local vessel operations. Similar to their findings, the power spectral density analysis from the present deployment revealed persistent low-frequency energy bands below 200 Hz, reflecting the heavy anthropogenic influence of the Strait as one of the busiest maritime corridors in Europe. A comparable pattern of high-frequency noise was also detected in this study, consistent with the echosounder signals described by Pérez Tadeo and O’Brien [

4]. In both cases, narrow-band emissions centred at approximately 30 kHz and 50 kHz were clearly visible in the spectrograms as continuous or intermittent horizontal lines, corresponding to frequency-modulated chirps typical of vessel-mounted echosounders. These signals likely originated from navigational sonar systems operating in the vicinity of the drifting buoy, similar to the devices reported by Pérez Tadeo and O’Brien [

4]. Their regular, pulsed structure and harmonic content up to 60 kHz are characteristic of such systems, and their persistence throughout the drift suggests that echosounder activity represents a stable and recurrent component of the regional soundscape. The agreement between both studies further confirms the widespread operation of high-frequency sonar systems across the Strait of Gibraltar and their contribution to the continuous anthropogenic acoustic background in this heavily trafficked maritime area.

While the overall structure of the soundscape observed in this study closely mirrors that reported by Pérez Tadeo and O’Brien [

4], a key difference lies in the biological component of the recordings. Their survey comprised short-term deployments (30–60 min) undertaken during daylight and early night-time hours between 21 and 24 October 2024 at 14 stations distributed across the southwest and south of Portugal, the Gulf of Cádiz, and the Strait of Gibraltar, yielding a total of 8.5 h of acoustic data. In their survey, conducted in October, only a few delphinid whistles were detected, with no acoustic evidence of killer whales or baleen whales. This temporal pattern is consistent with the seasonal distribution of the species: November falls outside the period of Iberian Orca occurrence in the Strait, as these animals are typically present during late spring and summer in association with bluefin tuna fisheries, whereas it coincides with the expected passage of Atlantic fin whales entering the Strait from the Atlantic, as previously reported by Castellote et al. [

27], although no fin whale vocalisations were detected in that survey [

4].

In contrast to the findings of Castellote et al. [

27], who documented the characteristic 20 Hz calls of fin whales in the Strait of Gibraltar, no such low-frequency pulse trains were detected during the present experiment. Instead, the analysis revealed a high number of transient events, shorter than one second in duration, with peak energy concentrated between 40 and 50 Hz. Although no visual confirmation of fin whale presence was obtained during the survey, the spectral and temporal characteristics of these signals are compatible with sounds produced by baleen whales, as similar 40 Hz calls have been described in recent years in several regions of the North Pacific and the North Atlantic and attributed to fin whales [

7,

38]. According to Širović et al. [

7], these 40 Hz signals occur seasonally, often peaking during foraging periods and preceding the 20 Hz reproductive calls by several months, suggesting a feeding-related function. Romagosa et al. [

38] further supported this interpretation, linking the 40 Hz calls to feeding behaviour associated with increased zooplankton biomass and upwelling dynamics. The detection of such signals in late May, coinciding with the seasonal increase in primary productivity and prey availability in the Strait of Gibraltar, reinforces the likelihood that these sounds were produced by foraging fin whales, and represents the first description of this 40 Hz call type in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Although the limited number of killer whale vocalisations recorded in this short deployment is insufficient to establish a complete description of the Iberian killer whale dialect, these data nonetheless provide the first acoustic characterisation of this subpopulation. The four call types identified represent a preliminary but significant step towards documenting the vocal repertoire of Iberian orcas, which had not previously been described. When compared with published repertoires of North Atlantic populations, including those from Iceland [

39], Shetland [

20], and western Icelandic waters [

24], no clear structural similarities or shared call types were observed. This absence of matching call patterns should, however, be interpreted with caution, given the very small sample size and the exploratory nature of this study.

Nevertheless, the lack of overlap with northern North Atlantic repertoires would be consistent with earlier comparative analyses showing limited acoustic similarity between killer whale populations from Iceland, Shetland, and Norway [

40]. In those studies, no call type matches were confirmed between Iceland and Norway or between Shetland and Norway, with only a few shared call types between Iceland and Shetland, indicating partial but distinct regional differentiation. The preliminary evidence presented here therefore aligns with the broader pattern of acoustic and genetic isolation observed among North Atlantic killer whale populations. At the same time, it provides further indirect support for the status of the Iberian subpopulation as an acoustically and demographically distinct group [

26].

The results of this exploratory drifting buoy deployment demonstrate the substantial potential of broadband passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) to characterise both the soundscape and the cetacean community of the Strait of Gibraltar [

41,

42]. Even using a single, short-term drifting system, it was possible to identify acoustic signatures of at least three key species—killer whales, fin whales, and sperm whales—alongside a detailed depiction of the prevailing anthropogenic noise regime. These results strongly support the establishment of a permanent, multi-station PAM network in the region, which would enable continuous monitoring of both biological and anthropogenic acoustic activity in one of the busiest and most ecologically significant marine passages worldwide.

Future Research Directions

The killer whale vocalisations recorded in this study highlight the potential of sustained passive acoustic monitoring to clarify the ecological and behavioural roles of cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar. Although the limited duration of our drifting deployment precludes assigning calls to specific behavioural contexts (e.g., feeding, social coordination or travel), previous work on baleen and toothed whales demonstrates that long-term PAM datasets can successfully discriminate such behaviours from acoustic patterns. For example, the seasonality of the fin whale 20 Hz song has been linked to reproductive activity [

43], whereas 40 Hz calls have been associated with foraging and seasonal zooplankton dynamics [

7,

38]. Likewise, detailed analyses of sperm whale click trains have revealed fine-scale diel foraging patterns in other regions [

44,

45,

46]. Establishing a permanent PAM system in the Strait would therefore allow comparable approaches to be applied to Iberian killer whales, enabling the behavioural interpretation of their call types and temporal patterns.

Beyond behavioural inference, future research would benefit from an array of synchronised PAM stations capable of localising sound sources and tracking the movement of vocalising cetaceans. Such systems have previously been used to infer migratory pathways, movement speeds and even approximate body size for various mysticetes [

8,

27,

47,

48,

49]. In the context of the Strait, where killer whale groups frequently interact with tuna fisheries, localisation-based tracking could provide valuable insights into spatial use, encounter rates and fine-scale habitat preferences. Finally, integrating long-term acoustic records with environmental covariates such as sea surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration and seasonal cycles would facilitate predictive modelling of cetacean presence and behaviour, building upon habitat-modelling frameworks already established for North Atlantic species [

50,

51]. Such models would substantially advance our capacity to interpret the biological patterns emerging from the present study and guide management strategies for this ecologically and culturally significant region.

Implementing long-term acoustic observatories in the Strait of Gibraltar would also contribute to broader biodiversity monitoring goals, providing early indicators of changes in species distribution, population connectivity, and acoustic habitat quality. Such systems have already proven essential to infer reproductive timing and habitat use in a variety of taxa, including pinnipeds [

48] and minke whales [

51,

52]. In the context of increasing anthropogenic pressure, a sustained PAM effort in the Strait could thus serve as a powerful tool for conservation management—supporting the identification of feeding hotspots, migratory corridors, and breeding zones—and inform the design of mitigation measures to reduce acoustic impacts and ship-strike risks in this critical ecological bottleneck.