Underwater Sound Source Depth Estimation Using Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Feature Verification

2.1. Theoretical Basis

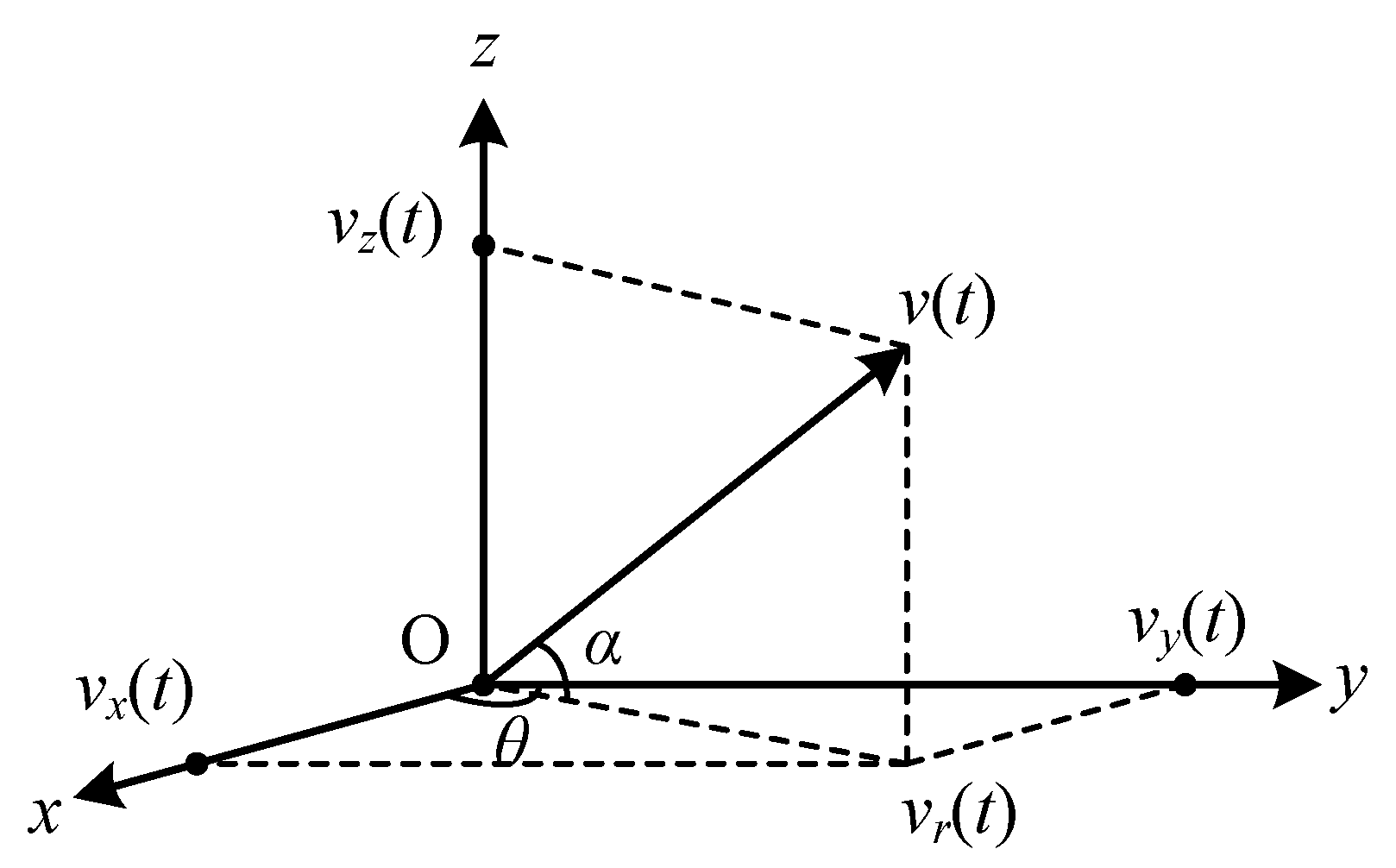

Vector Sound Field Calculation Model Based on Normalised Wave Theory

2.2. Depth Estimation of Underwater Sound Sources Based on Matching Field Algorithms

2.2.1. Matched Field Processing

2.2.2. Depth Estimation Performance Analysis

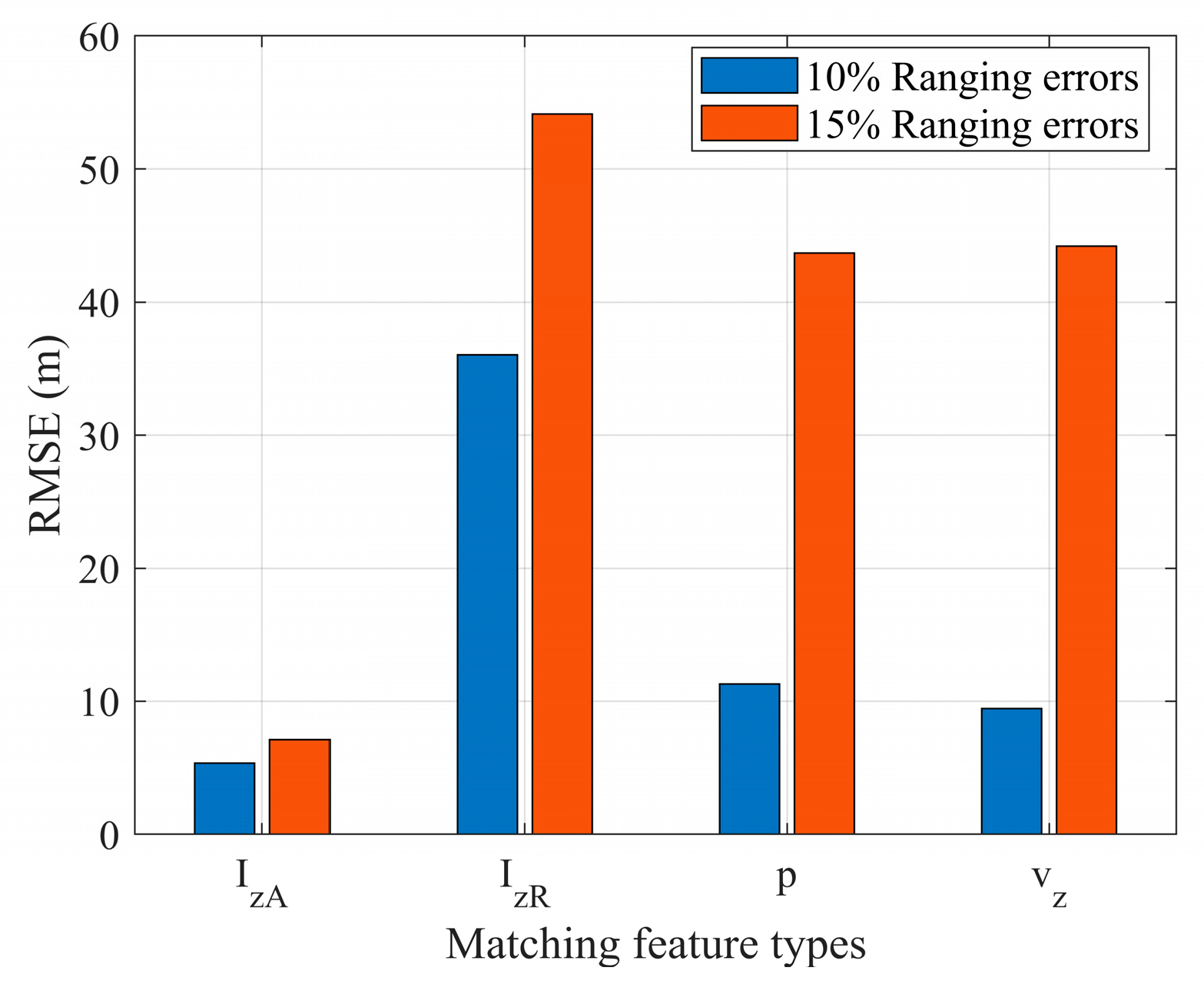

The Impact of Distance Measurement Errors on Depth Estimation

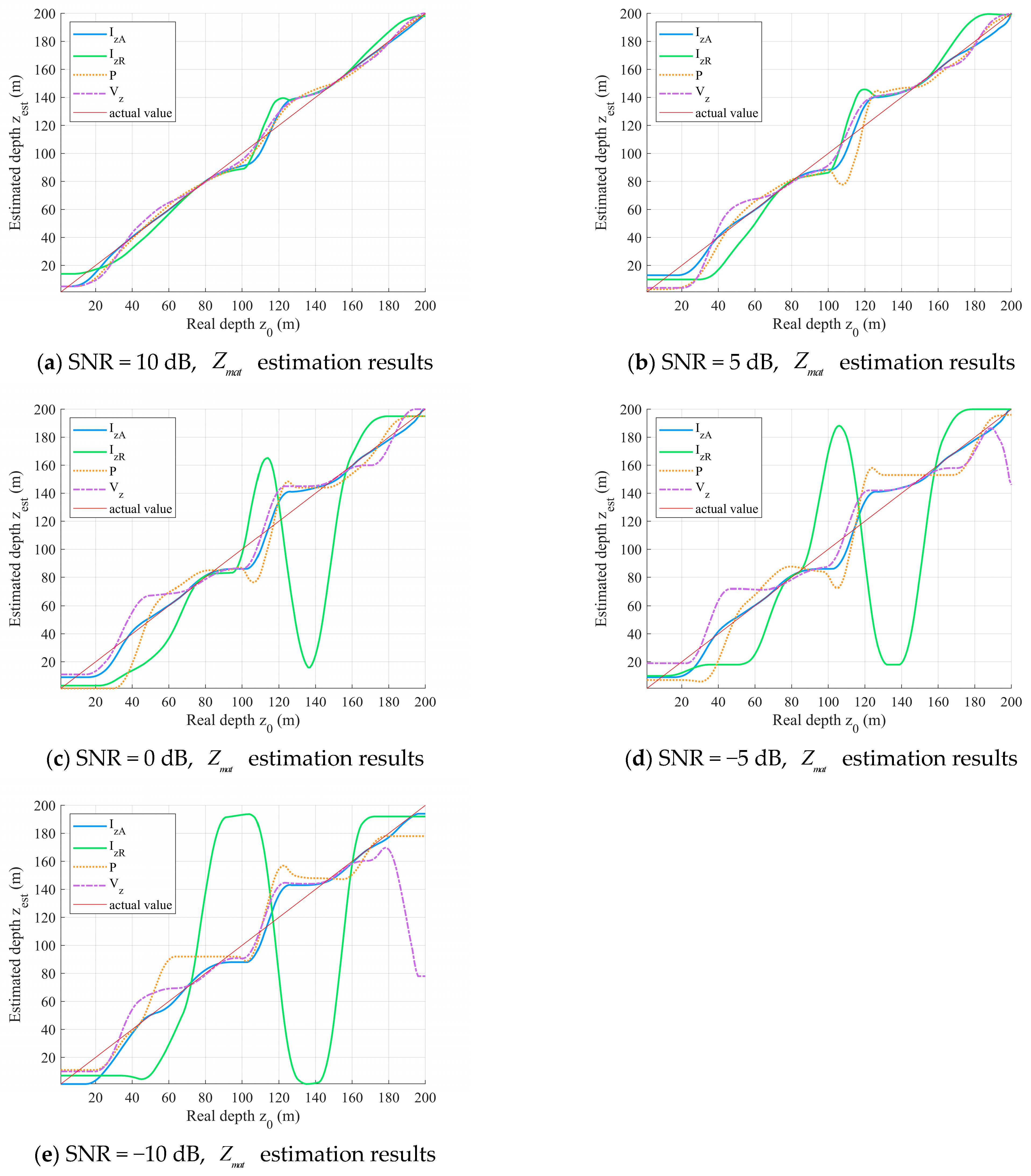

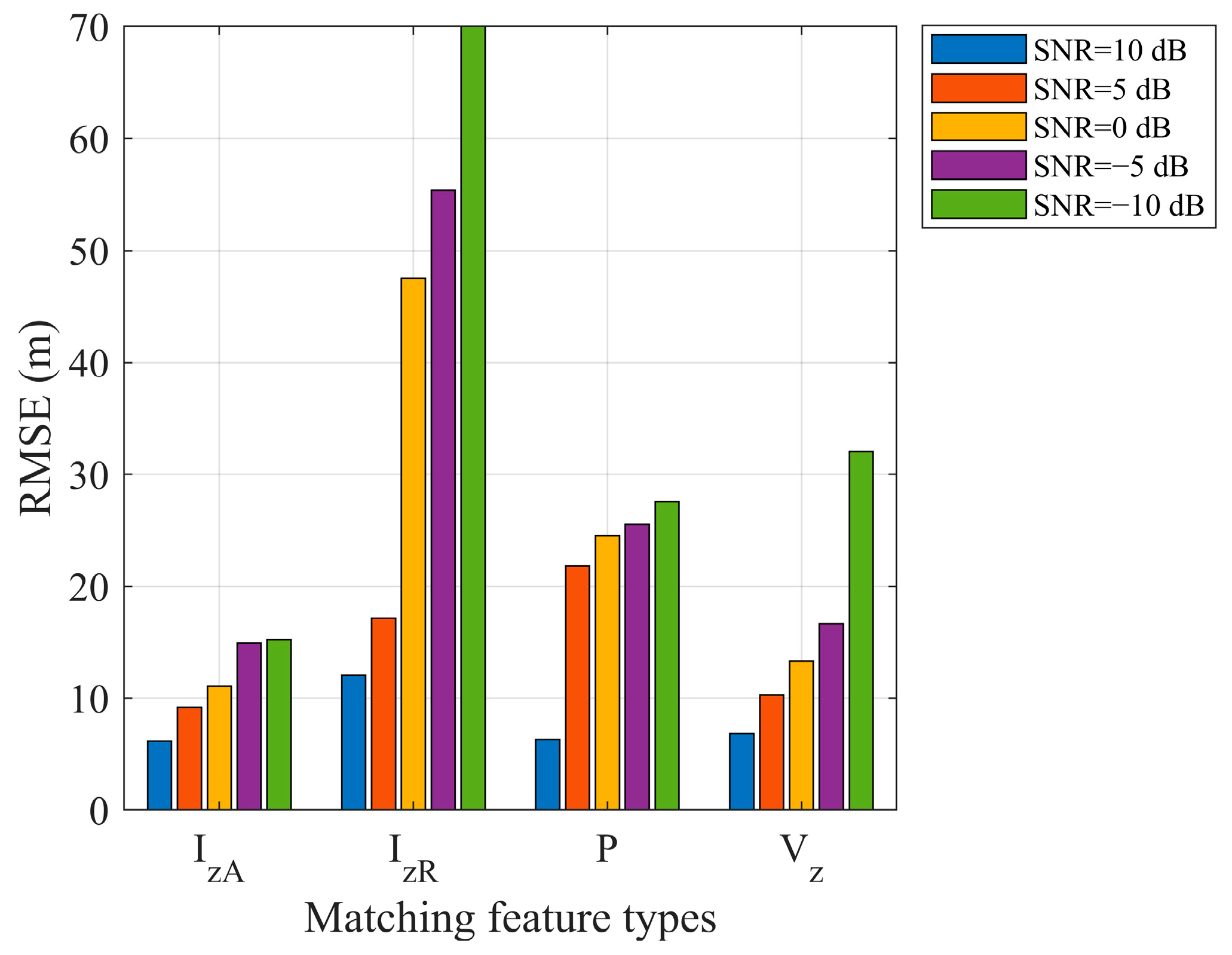

The Impact of Different SNR on Depth Estimation

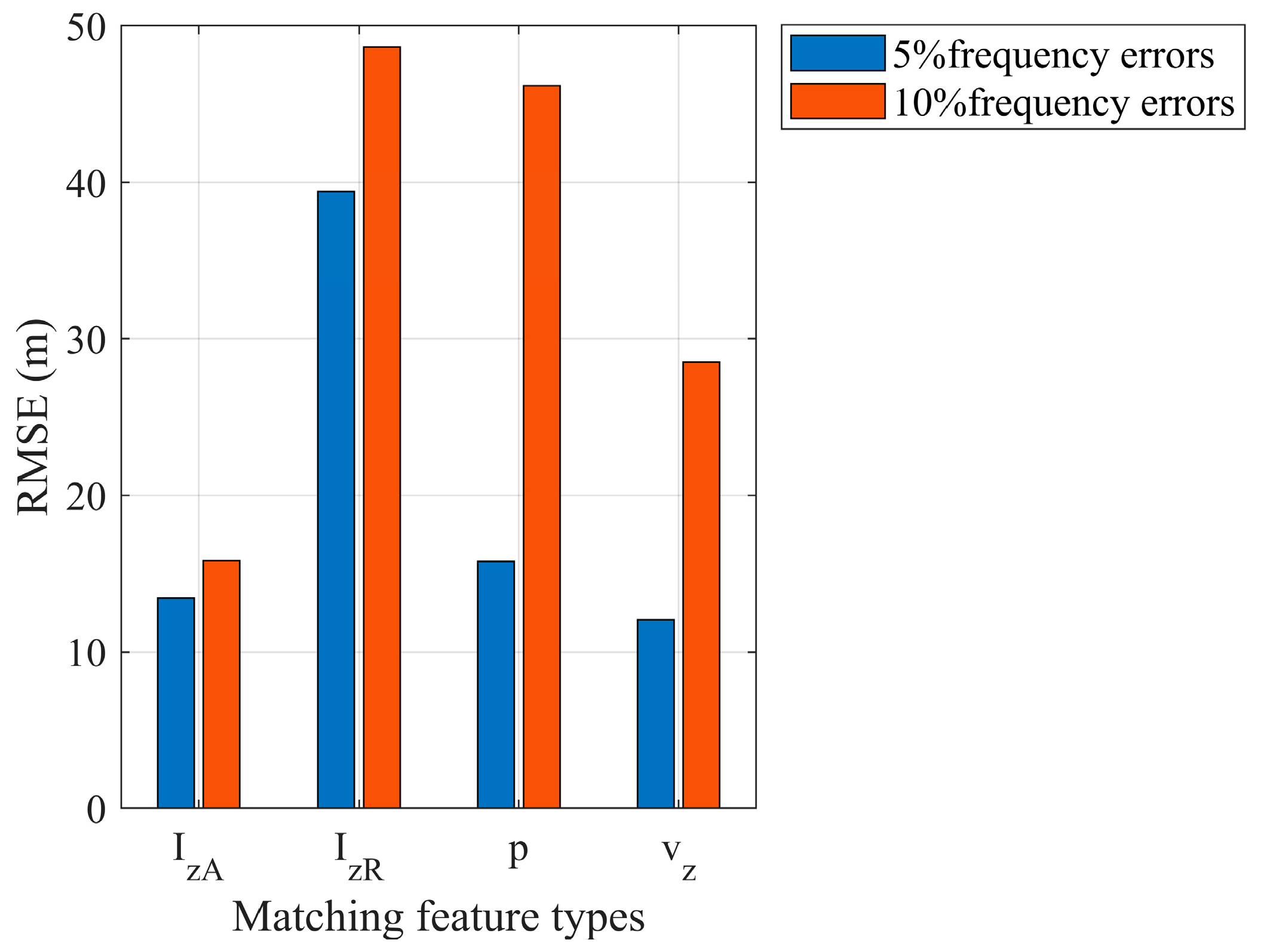

Impact of Sound Source Frequency Estimation Error on Depth Estimation

2.3. Underwater Sound Source Depth Identification Based on Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features

2.3.1. Overall Framework

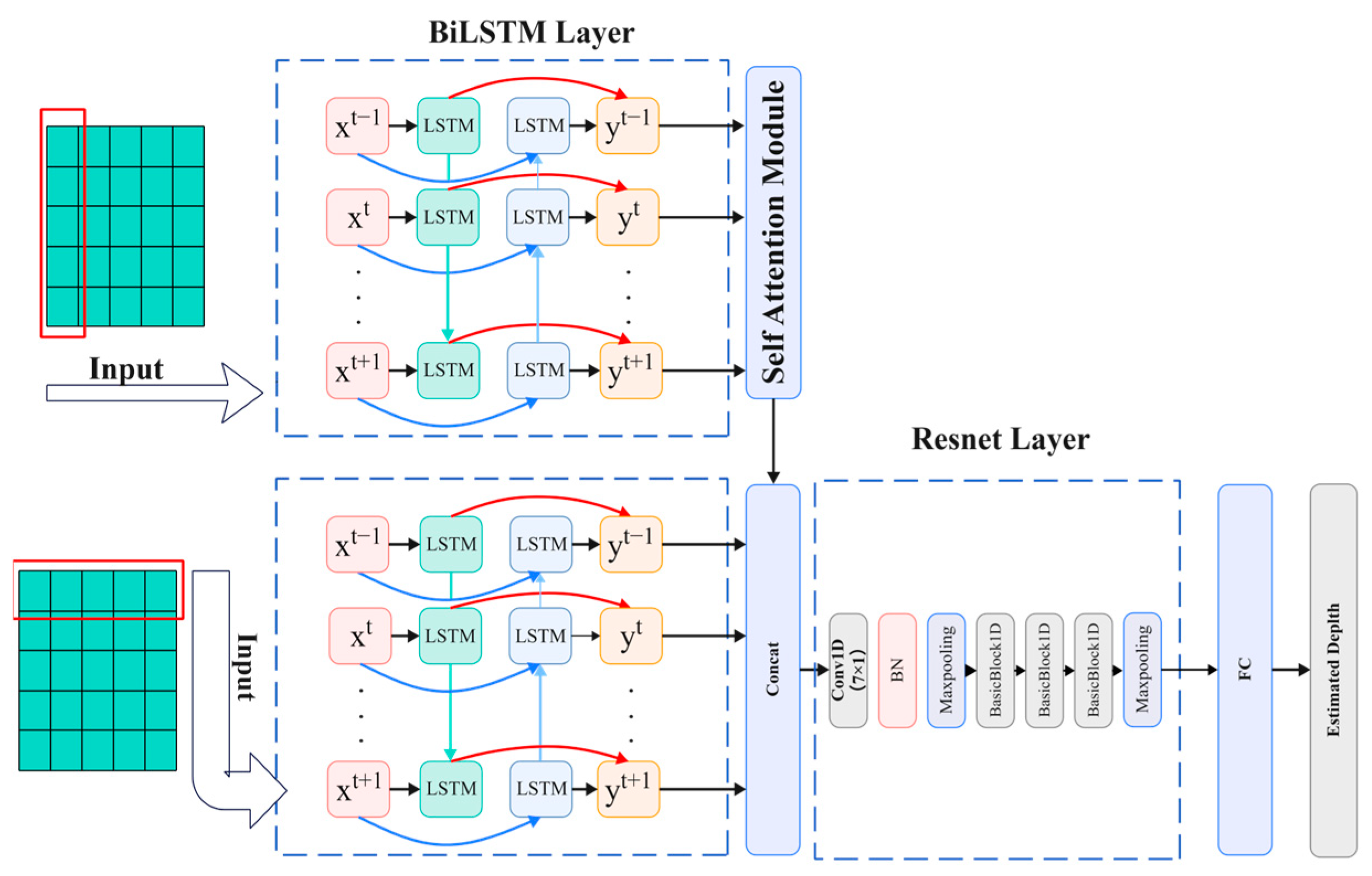

2.3.2. Network Model Structure Design

2.3.3. Evaluation Criteria

3. Experimental Results and Discussion

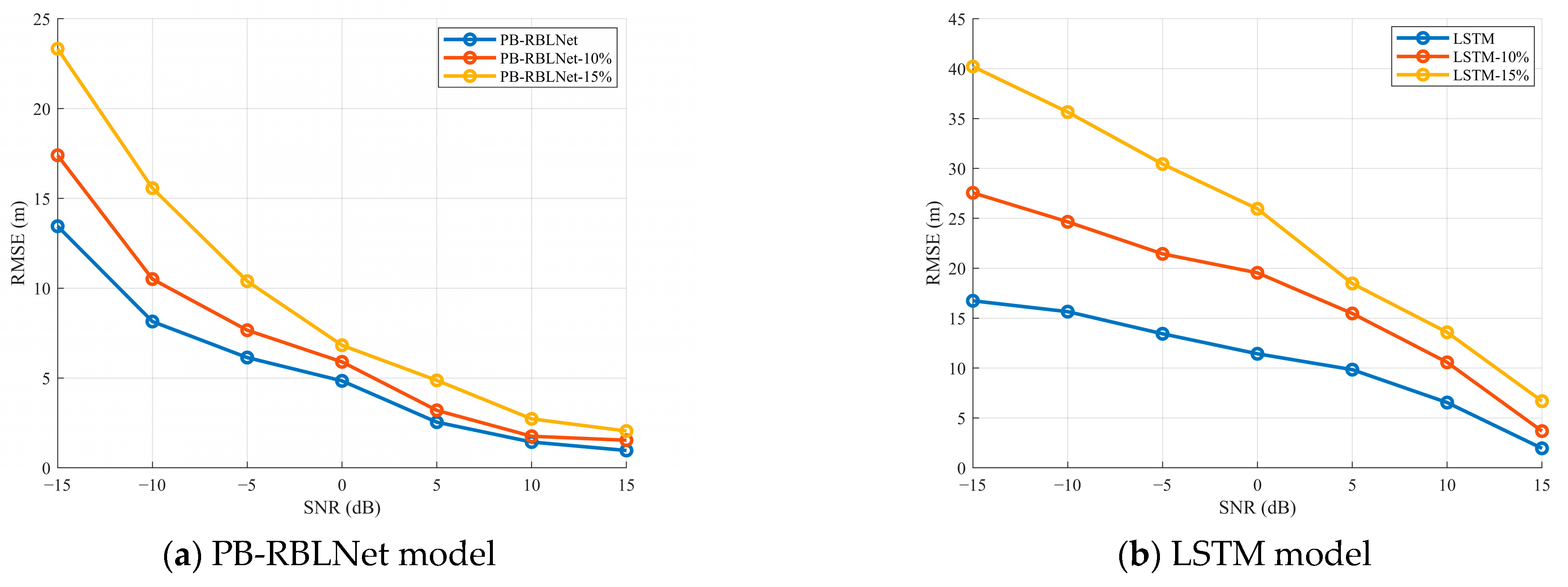

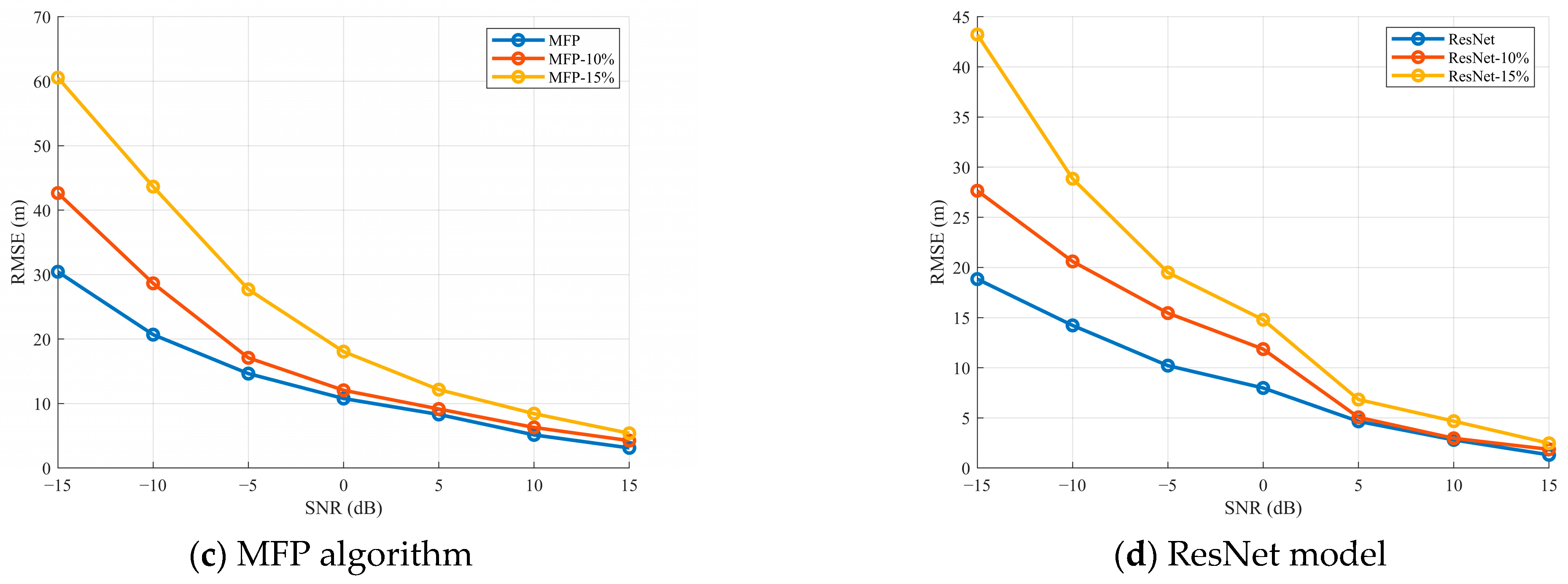

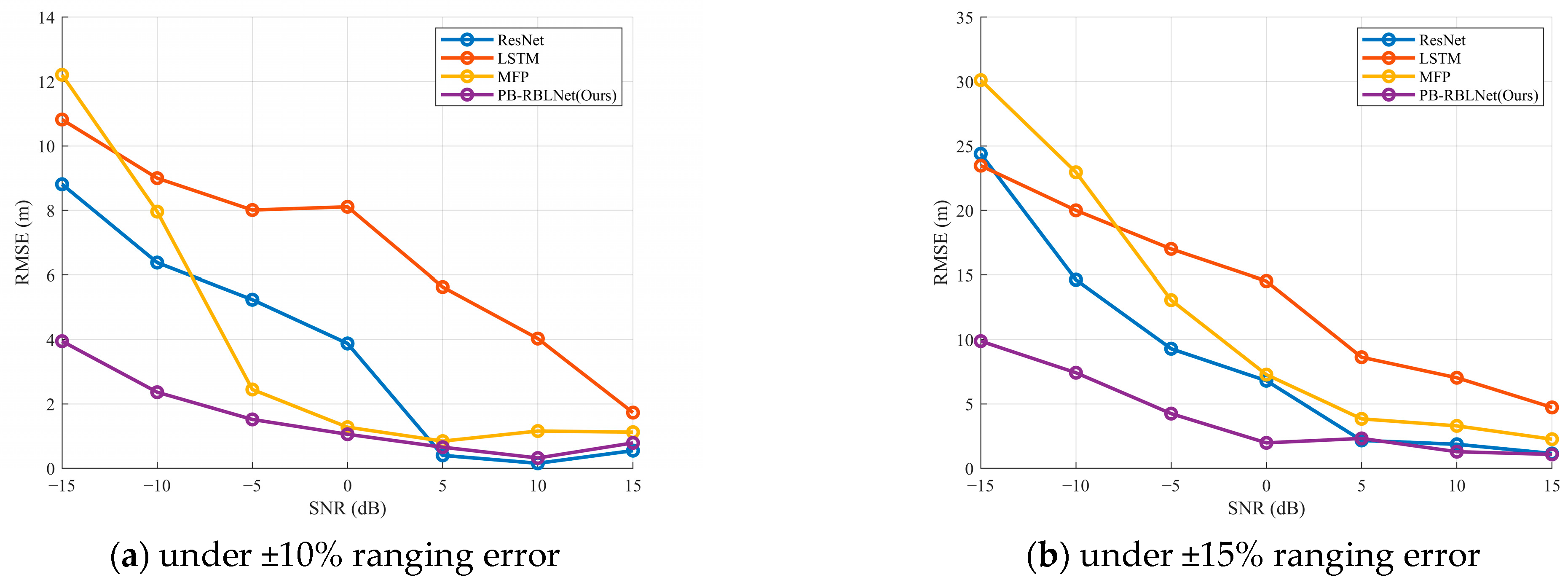

3.1. Performance Analysis Under Different SNR

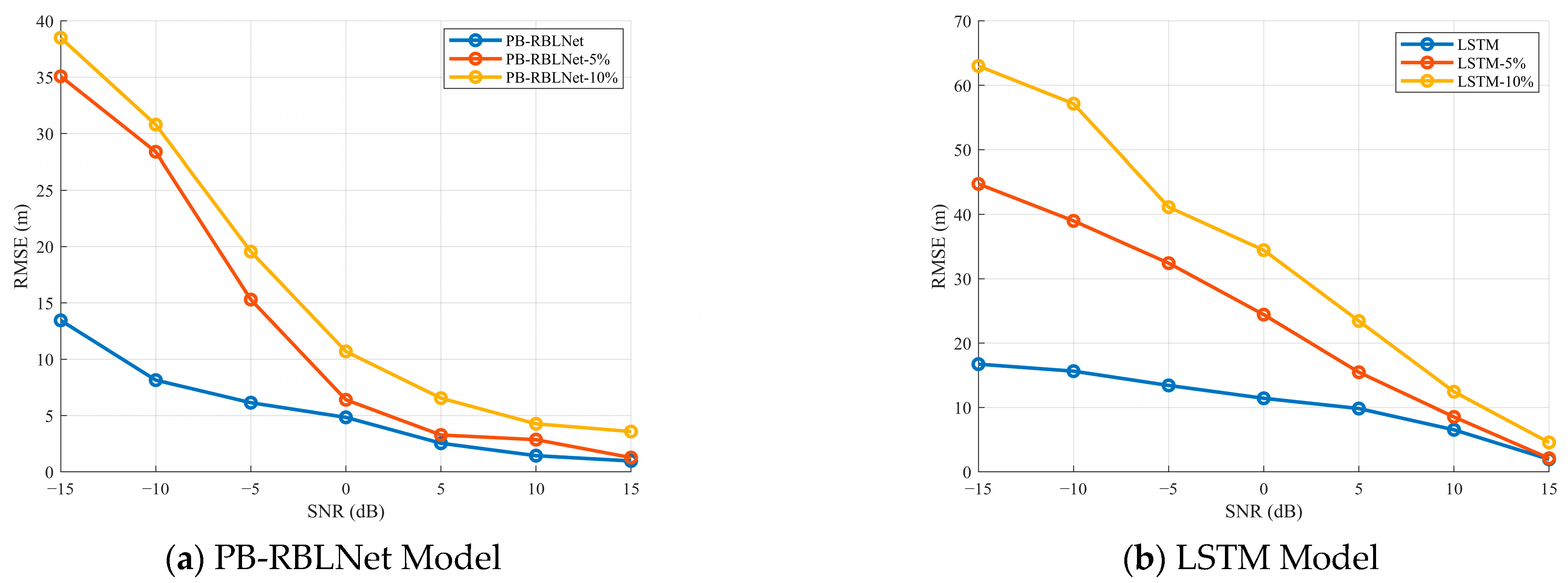

3.2. Performance Analysis Under Different Ranging Errors

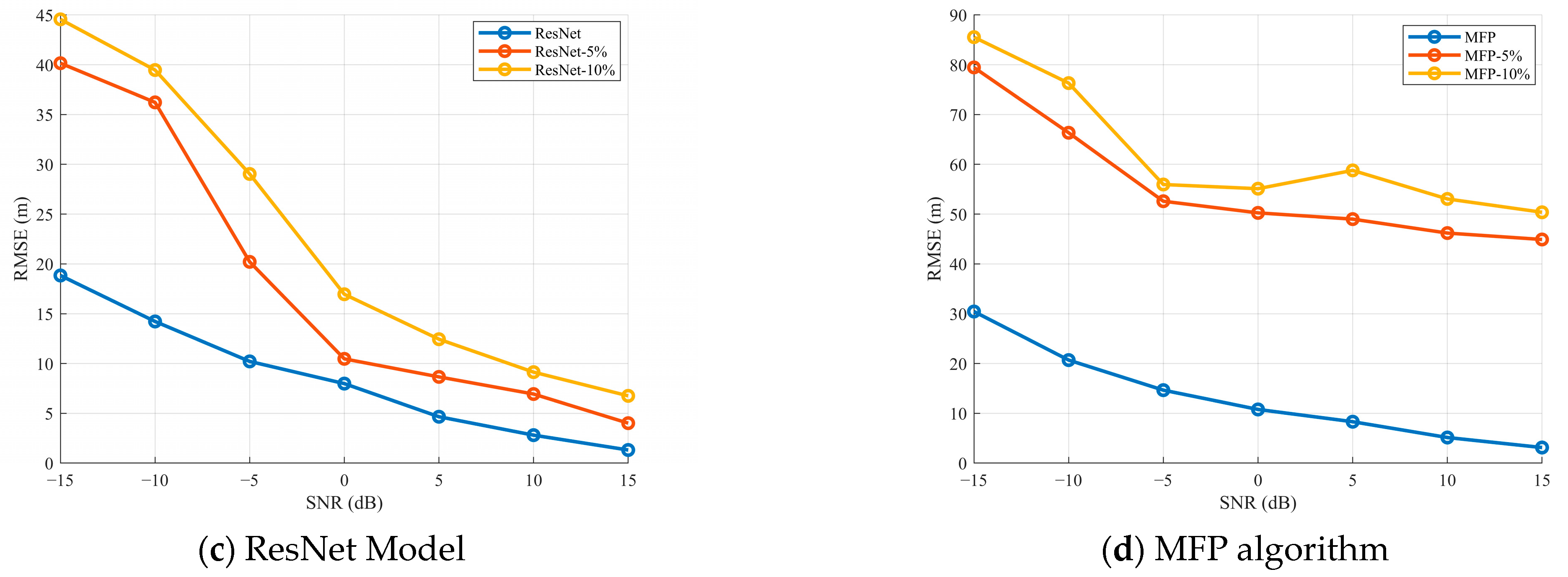

3.3. Performance Analysis Under Different Frequency Errors

3.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, X.; Guo, L.; Luo, C.; Zhou, X.; Yu, C. A Survey of Target Detection and Recognition Methods in Underwater Turbid Areas. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, K.; Duan, R.; Lei, Z. Joint Estimation of Source Range and Depth Using a Bottom-Deployed Vertical Line Array in Deep Water. Sensors 2017, 17, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kniffin, G.P.; Boyle, J.K.; Zurk, L.M.; Siderius, M. Performance metrics for depth-based signal separation using deep vertical line arrays. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCargar, R.; Zurk, L.M. Depth-based signal separation with vertical line arrays in the deep ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 133, EL320–EL325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byun, G.; Song, H.C.; Kim, J.S. Performance comparisons of array invariant and matched field processing using broadband ship noise and a tilted vertical array. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2018, 144, 3067–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.; Felisberto, P.; Jesus, S.M. Vector Sensor Arrays in Underwater Acoustic Applications. In Emerging Trends in Technological Innovation; Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Pereira, P., Ribeiro, L., Eds.; DoCEIS 2010. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, L.; Lei, B.; Gu, T.; He, Z. Depth Estimation of an Underwater Moving Source Based on the Acoustic Interference Pattern Stream. Electronics 2025, 14, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ling, Q.; Xu, J. Pressure and velocity cross-spectrum of normal modes in low-frequency acoustic vector field of shallow water and its application. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2015, 26, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yin, J.; Yu, Y.; Shi, Z. Depth classification of underwater targets based on complex acoustic intensity of normal modes. J. Ocean Univ. China 2016, 15, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Bi, X.; Hui, J.; Zeng, C.; Ma, L. Application and Extension of Vertical Intensity Lower-Mode in Methods for Target Depth-Resolution with a Single-Vector Sensor. Sensors 2018, 18, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Tu, X.; Qu, F. An Underwater Wideband Sound Source Localization Method Based on Light Neural Network Structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 20970–20980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Su, L.; Hu, T.; Ren, Q.; Gerstoft, P.; Ma, L. Source depth estimation using spectral transformations and convolutional neural network in a deep-sea environment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 3633–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, A.; Arikan, T.; Wornell, G.W. Direct Localization in Underwater Acoustics Via Convolutional Neural Networks: A Data-Driven Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 32nd International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), Xi’an, China, 22–25 August 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y. A Deep-Sea Broadband Sound Source Depth Estimation Method Based on the Interference Structure of the Compensated Beam Output. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Hui, J.; Zhao, A.; Wang, B.; Ma, L.; Li, X. Underwater Target Depth Classification Method Based on Vertical Acoustic Intensity Flux. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2021, 43, 3237–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Hui, J.; Zhao, A.; Wang, B.; Ma, L.; Li, X. Research on Acoustic Target Depth Classification Method Based on Matching Field Processing in Shallow Water. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2022, 44, 3917–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, B. Particle velocity gradient based acoustic mode beamforming for short linear vector sensor arrays. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2014, 135, 3463–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, D.M.F.; Thomson, D.J.; Ellis, D.D. Modeling air-to-water sound transmission using standard numerical codes of underwater acoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1992, 91, 1904–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’osto, D.R.; Dahl, P.H.; Choi, J.W. Properties of the acoustic intensity vector field in a shallow water waveguide. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2012, 131, 2023–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, F.B.; Kuperman, W.A.; Porter, M.B.; Schmidt, H.; Tolstoy, A. Computational Ocean Acoustics. Phys. Today 1994, 47, 91–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.J.; Giddens, E.M. On the acoustic field in a Pekeris waveguide with attenuation in the bottom half-space. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2006, 119, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Depth of the sea H | 200 m |

| Seawater density ρ1 | 1.026 g/cm3 |

| Sediment density ρ2 | 1.769 g/cm3 |

| Sound source frequency f | 40 Hz |

| Sound velocity in seawater c1 | 1480 m/s |

| Sedimental acoustic velocity c2 | 1550 m/s |

| Sound source depth range | 1~200 m |

| Horizontal distance range | 2~8 km |

| Layer | Type | Input Shape | Output Shap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input (vertical branch) | (1, 200, 1500) | ||

| BiLSTM1 (bidirectional, H = 128) | BiLSTM | (1, 200, 1500) | (1, 200, 256) |

| Self-attention module | Attention | (1, 200, 256) | (1, 256) |

| Input (horizontal branch) | (1, 1500, 200) | ||

| BiLSTM2 (bidirectional, H = 128) | BiLSTM | (1, 1500, 200) | (1, 1500, 256) |

| AvgPool | AvgPool1D | (1, 1500, 256) | (1, 256) |

| feature fusion | Concatenation | (1, 256) + (1, 256) | (1, 512) |

| ResNet module | Multi-layer residual blocks | (1 × 512) | (1 × 512) |

| Fully connected layer 1 (ReLU) | FC + ReLU | (1 × 512) | (1 × 256) |

| Fully connected layer 2 | FC2 | (1 × 256) | 1 × 1 (output) |

| SNR (dB) | PB-RBLNet | ResNet | LSTM | MFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 96.32% | 95.44% | 88.12% | 84.10% |

| 10 | 92.96% | 89.75% | 84.23% | 78.76% |

| 5 | 88.17% | 70.59% | 53.14% | 51.98% |

| 0 | 70.22% | 32.21% | 42.17% | 42.28% |

| −5 | 49.53% | 26.13% | 38.53% | 36.51% |

| −10 | 38.39% | 18.89% | 30.94% | 28.49% |

| −15 | 35.51% | 12.14% | 9.68% | 8.4% |

| SNR (dB) | PB-RBLNet | ResNet | LSTM | MFP | PB-RBLNet | ResNet | LSTM | MFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 96.32% | 95.44% | 88.12% | 84.10% | 94.47% | 93.97% | 68.69% | 61.47% |

| 10 | 92.96% | 89.75% | 84.23% | 78.76% | 92.17% | 84.36% | 58.18% | 46.84% |

| 5 | 88.17% | 70.59% | 53.14% | 51.98% | 86.55% | 66.18% | 20.91% | 32.41% |

| 0 | 70.22% | 32.21% | 42.17% | 42.28% | 61.31% | 30.87% | 13.54% | 21.64% |

| −5 | 49.53% | 26.13% | 38.53% | 36.51% | 41.34% | 20.11% | 11.42% | 11.77% |

| −10 | 38.39% | 18.89% | 30.94% | 28.49% | 27.63% | 17.45% | 8.34% | 6.23% |

| −15 | 35.51% | 12.14% | 9.68% | 8.4% | 17.51% | 8.17% | 6.75% | 4.25% |

| Model | Parameters | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|

| PB-RBLNet | 3,650,896 | 1.34 G |

| LSTM | 1,798,912 | 719 M |

| ResNet1D | 1,742,848 | 697 M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Bi, X.; Yang, K. Underwater Sound Source Depth Estimation Using Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122284

Wang B, Chen C, Bi X, Yang K. Underwater Sound Source Depth Estimation Using Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122284

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Biao, Chao Chen, Xuejie Bi, and Kang Yang. 2025. "Underwater Sound Source Depth Estimation Using Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122284

APA StyleWang, B., Chen, C., Bi, X., & Yang, K. (2025). Underwater Sound Source Depth Estimation Using Deep Learning and Vector Acoustic Features. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2284. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122284