Coral Recruitment and Survival in a Remote Maldivian Atoll 11 Years Apart

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

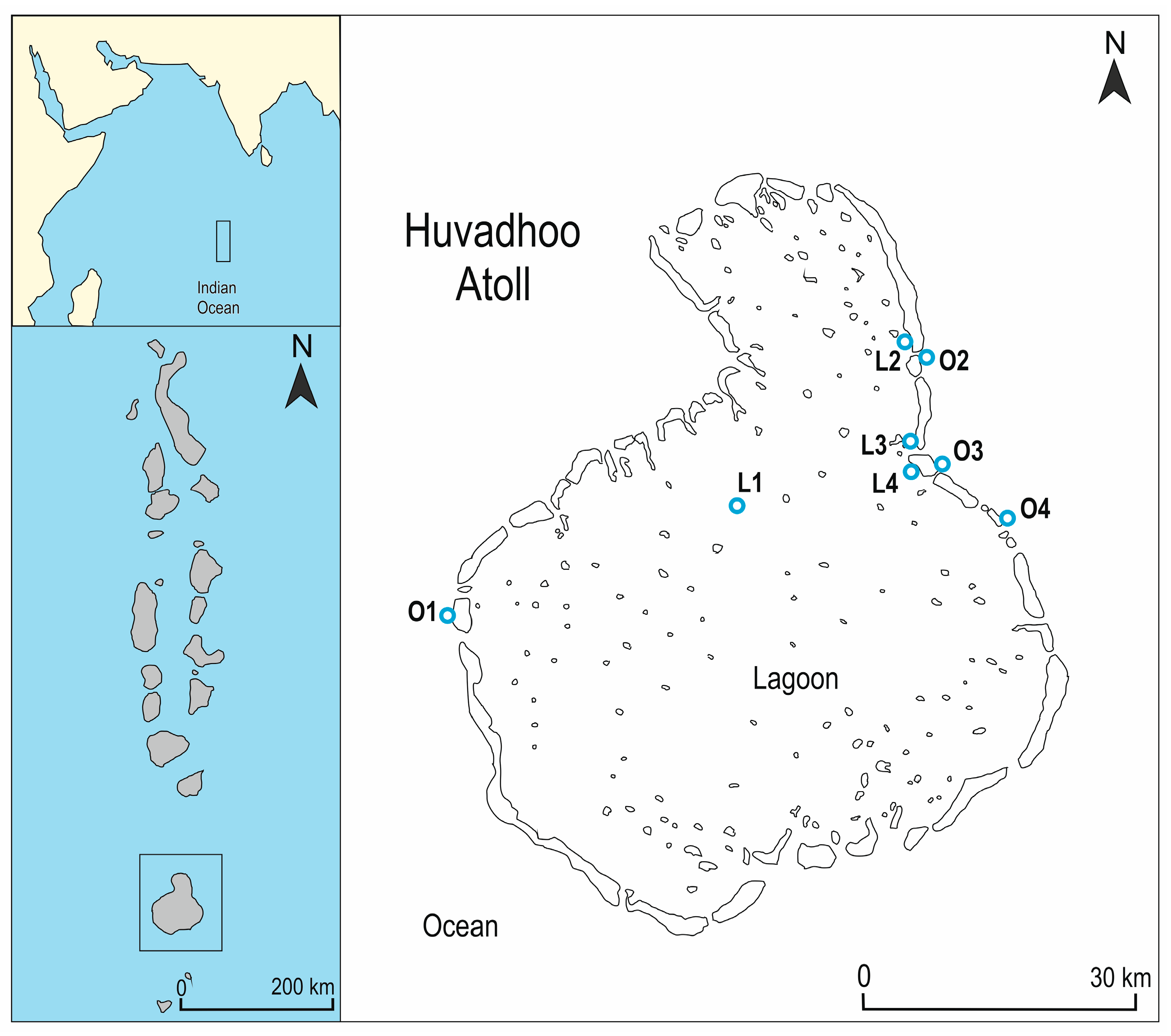

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Activities

2.3. Data Analyses

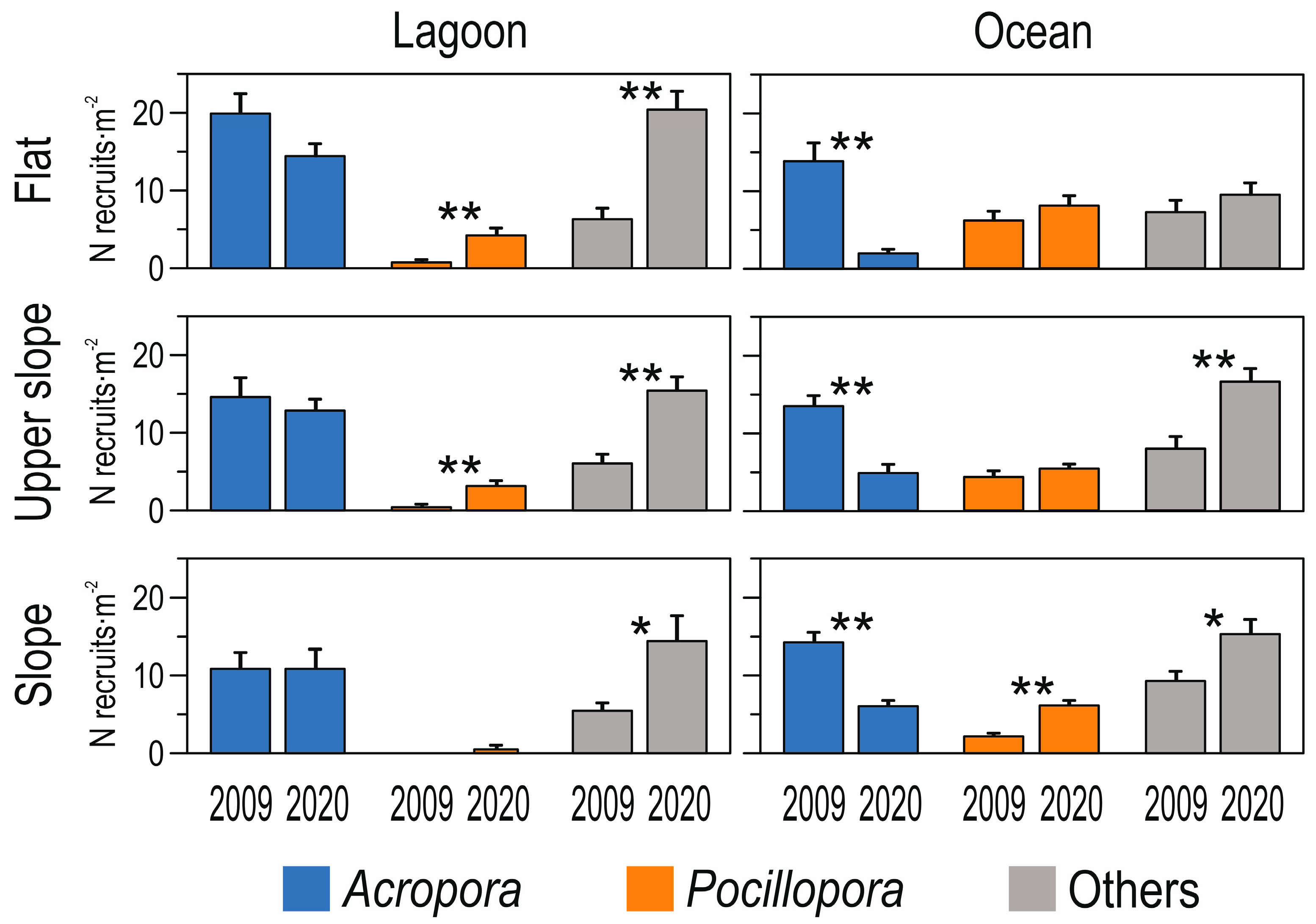

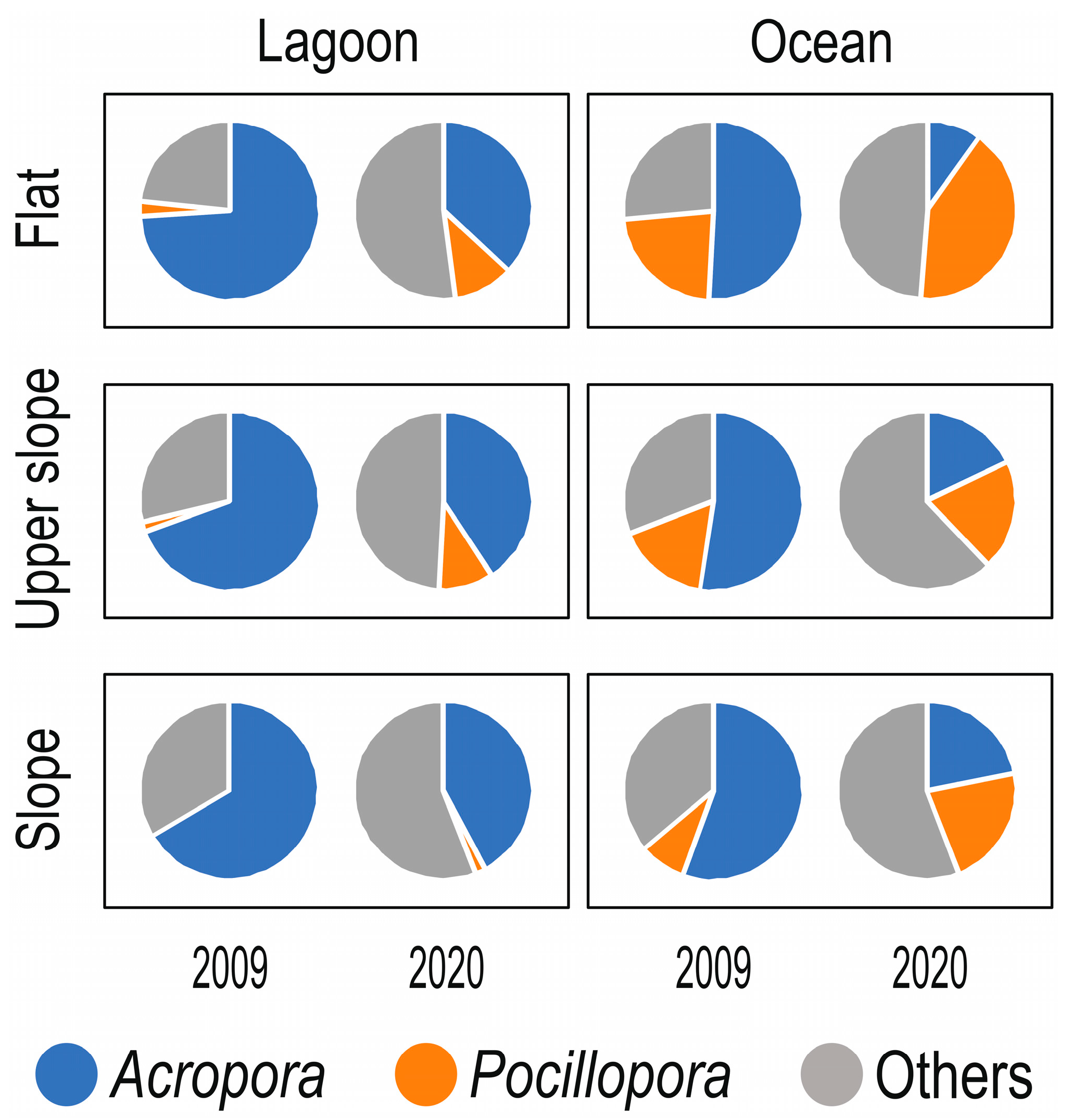

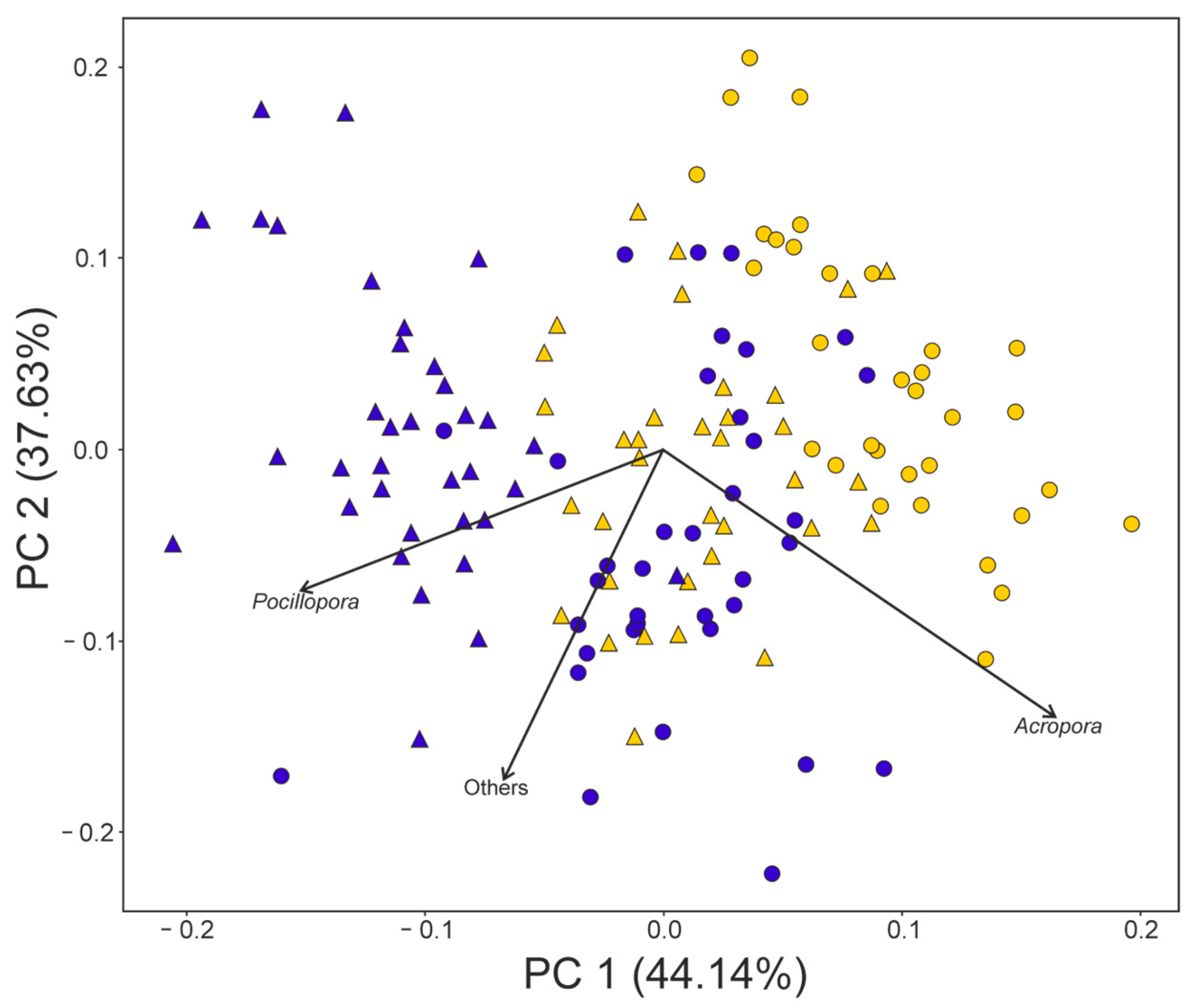

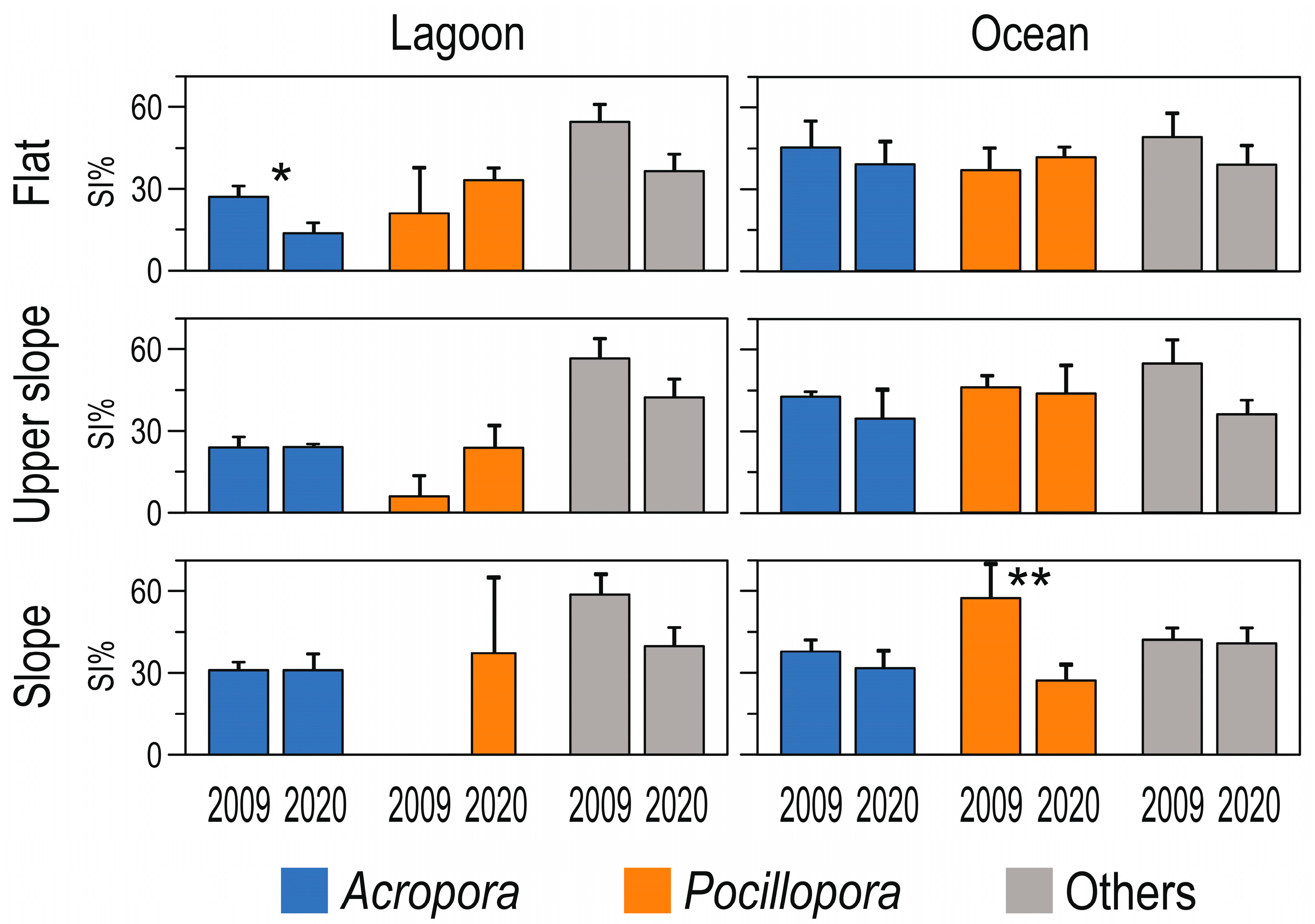

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riegl, B.; Bruckner, A.; Coles, S.L.; Renaud, P.; Dodge, R.E. Coral reefs: Threats and conservation in an era of global change. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1162, 136–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Barnes, M.L.; Bellwood, D.R.; Cinner, J.E.; Cumming, G.S.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Kleypas, J.; van de Leemput, I.A.; Lough, J.M.; Morrison, T.H.; et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature 2017, 546, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A.D.; Karoly, D.J.; Henley, B.J. Australian climate extremes at 1.5 °C and 2 °C of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Anderson, K.D.; Connolly, S.R.; Heron, S.F.; Kerry, J.T.; Lough, J.M.; Baird, A.H.; Baum, J.K.; Berumen, M.L.; Bridge, T.C.; et al. Spatial and temporal patterns of mass bleaching of corals in the Anthropocene. Science 2018, 359, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.G.; Roch, C.; Duarte, C.M. Systematic review of the uncertainty of coral reef futures under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellwood, D.R.; Hughes, T.P.; Folke, C.; Nyström, M. Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 2004, 429, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjeroud, M.; Kayal, M.; Penin, L. Importance of recruitment processes in the dynamics and resilience of coral reef assemblages. In Marine Animal Forests: The Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots; Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., Orejas, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 549–569. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, P.J. Coral recruitment: Patterns and processes determining the dynamics of coral populations. Biol. Rev. 2023, 98, 1862–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Baird, A.H.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Moltschaniwskyj, N.A.; Pratchett, M.S.; Tanner, J.E.; Willis, B.L. Supply-side ecology works both ways: The link between benthic adults, fecundity, and larval recruits. Ecology 2000, 81, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Lasagna, R.; Montefalcone, M.; Gatti, G.; Parravicini, V.; Rovere, A. Resilience of the marine animal forest: Lessons from Maldivian coral reefs after the mass mortality of 1998. In Marine Animal Forests: The Ecology of Benthic Biodiversity Hotspots; Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., Orejas, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1241–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Jokiel, P.L. How corals gain foothold in new environments. Coral Reefs 1992, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarco, P.W.; Andrews, J.C. Localized dispersal and recruitment in Great Barrier Reef corals: The Helix experiment. Science 1988, 239, 1422–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K.P.; Moran, P.J.; Hammond, L.S. Numerical-models show coral reefs can be self-seeding. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1991, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprandi, A.; Montefalcone, M.; Morri, C.; Benelli, F.; Bianchi, C.N. Water circulation, and not ocean acidification, affects coral recruitment and survival at shallow hydrothermal vents. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 217, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCook, L.; Jompa, J.; Diaz-Pulido, G. Competition between corals and algae on coral reefs: A review of evidence and mechanisms. Coral Reefs 2001, 19, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.N.; Steneck, R.S.; Mumby, P.J. Running the gauntlet: Inhibitory effects of algal turfs on the processes of coral recruitment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 414, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.N. Running the Gauntlet to Coral Recruitment Through a Sequence of Local Multiscale Processes. Master’s Thesis, The University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Riegl, B.; Purkis, S. Coral population dynamics across consecutive mass mortality events. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3995–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallela, J.; Crabbe, M.J.C. Hurricanes and coral bleaching linked to changes in coral recruitment in Tobago. Mar. Environ. Res. 2009, 68, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumby, P.J. Bleaching and hurricane disturbances to populations of coral recruits in Belize. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 190, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crabbe, M.J.C. Scleractinian coral population size structures and growth rates indicate coral resilience on the fringing reefs of North Jamaica. Mar. Environ. Res. 2009, 67, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Kerry, J.T.; Baird, A.H.; Connolly, S.R.; Chase, T.J.; Dietzel, A.; Hill, T.; Hoey, A.S.; Hoogenboom, M.O.; Jacobson, M.; et al. Global warming impairs stock–recruitment dynamics of corals. Nature 2019, 568, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.M.A.; Quadir, D.A.; Murty, T.S.; Kabir, A.; Aktar, F.; Sarker, M.A. Relative Sea level changes in Maldives and vulnerability of land due to abnormal coastal inundation. Mar. Geod. 2002, 25, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Pichon, M.; Benzoni, F.; Colantoni, P.; Baldelli, G.; Sandrini, M. Dynamics and pattern of coral recolonization following the 1998 bleaching event in the reefs of the Maldives. In Proceedings of the 10th International Coral Reef Symposium, Ginowan, Japan, 28 June–2 July 2004; Suzuki, Y., Nakamori, T., Hidaka, M., Kayanne, H., Casareto, B.E., Nadaoka, K., Yamano, H., Tsuchiya, M., Eds.; Japanese Coral Reef Society: Tokyo, Japan, 2006; pp. 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Morri, C.; Montefalcone, M.; Lasagna, R.; Gatti, G.; Rovere, A.; Parravicini, V.; Baldelli, G.; Colantoni, P.; Bianchi, C.N. Through bleaching and tsunami: Coral reef recovery in the Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 98, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefalcone, M.; Morri, C.; Bianchi, C.N. Influence of local pressures on Maldivian coral reef resilience following repeated bleaching events, and recovery perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, T.R. Bleaching damage and recovery potential of Maldivian coral reefs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.J.; Clark, S.; Zahir, H.; Rajasuriya, A.; Naseer, A.; Rubens, J. Coral bleaching and mortality on artificial and natural reefs in Maldives in 1998, sea surface temperature anomalies and initial recovery. Mar Pollut Bull 2001, 42, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, K.; Loch, W.; Schuhmacher, H.; See, W.R. Coral recruitment and regeneration on a Maldivian reef 21 months after the coral bleaching event of 1998. Mar. Ecol. 2002, 23, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, K.; Loch, W.; Schuhmacher, H.; See, W.R. Coral recruitment and regeneration on a Maldivian reef four years after the coral bleaching event of 1998. Part 2: 2001–2002. Mar. Ecol. 2004, 25, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, C.; Burn, D.; Yoosuf, R.; Najeeb, A.; Anderson, K.D.; Pratchett, M.S. Coral recovery in the central Maldives archipelago since the last major mass-bleaching in 1998. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowburn, B.; Moritz, C.; Grimsditch, G.; Solandt, J.L. Evidence of coral bleaching avoidance, resistance and recovery in the Maldives during the 2016 mass-bleaching event. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2019, 626, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, C.; Burn, D.; Pratchett, M.S. Changes in the population and community structure of corals during recent disturbances (February 2016–October 2017) on Maldivian coral reefs. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Done, T.J.; DeVantier, L.M.; Turak, E.; Fisk, D.A.; Wakeford, M.; Van Woesik, R. Coral growth on three reefs: Development of recovery benchmarks using a space for time approach. Coral Reefs 2010, 29, 815–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, P.J.; Putnam, H.M.; Nisbet, R.M.; Muller, E.B. Benchmarks in organism performance and their use in comparative analyses. Oecologia 2011, 167, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampa, G.; Azzola, A.; Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Oprandi, A.; Montefalcone, M. Patterns of change in coral reef communities of a remote Maldivian atoll revisited after eleven years. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosoamananto, R.L.; Todinanahary, G.; Gasimandova, L.M.; Randrianarivo, M.; Penin, L.; Adjeroud, M. Regulation of coral assemblages: Spatial and temporal variation in the abundance of recruits, juveniles, and adults. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, T.R. Changes in coral sensitivity to thermal anomalies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 570, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M.; Kench, P.S. Reef island dynamics and mechanisms of change in Huvadhoo Atoll, Republic of Maldives, Indian Ocean. Anthropocene 2017, 18, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullo, W.C. Coral growth and reef growth: A brief review. Facies 2005, 51, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardini, U.; Chiantore, M.; Lasagna, R.; Morri, C.; Bianchi, C.N. Size-structure patterns of juvenile hard corals in the Maldives. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 2012, 92, 1335–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, S.; Warder, S.C.; Plancherel, Y.; Piggott, M.D. Response of tidal flow regime and sediment transport in North Malé Atoll, Maldives to coastal modification and sea level rise. Ocean Sci. Discuss. 2021, 17, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, M.P. Permanent quadrats: An interface for theory and practice. Vegetatio 1981, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, M.; Kühne, A.; Isermann, M. Random vs non-random sampling: Effects on patterns of species abundance, species richness and vegetation-environment relationships. Folia Geobot. 2007, 42, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, I.; Azzola, A.; Bianchi, C.N.; Capello, M.; Cutroneo, L.; Morri, C.; Oprandi, A.; Montefalcone, M. Habitat Fragmentation Enhances the Difference between Natural and Artificial Reefs in an Urban Marine Coastal Tract. Diversity 2024, 16, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouresque, C.F.; Belsher, T. Une méthode de determination de l’aire minimale qualitative. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Médit. 1979, 25, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T.P.; Baird, A.H.; Dinsdale, E.A.; Harriott, V.J.; Moltschaniwskyj, N.A.; Pratchett, M.S.; Tanner, J.E.; Willis, B.L. Detecting regional variation using meta-analysis and large-scale sampling: Latitudinal patterns in recruitment. Ecology 2002, 83, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, E.S.; Alvarez-Filip, L.; Oliver, T.A.; McClanahan, T.R.; Côté, I.M. Evaluating life history strategies of reef corals from species traits. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClanahan, T.; Ateweberhan, M.; Graham, N.A.J.; Wilson, S.K.; Sebastián, C.R.; Guillaume, M.M.; Bruggemann, J.H. Western Indian Ocean coral communities: Bleaching responses and susceptibility to extinction. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 337, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidenbach, M.A.; Stocking, J.B.; Szczyrba, L.; Wendelken, C. Hydrodynamic interactions with coral topography and its impact on larval settlement. Coral Reefs 2021, 40, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, C.; Brandl, S.J.; Rouzé, H.; Vii, J.; Pérez-Rosales, G.; Bosserelle, P.; Chancerelle, Y.; Galzin, R.; Liao, V.; Siu, G.; et al. Long-term monitoring of benthic communities reveals spatial determinants of disturbance and recovery dynamics on coral reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2021, 672, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.W.; Weil, E.; Szmant, A.M. Coral recruitment and juvenile mortality as structuring factors for reef benthic communities in Biscayne National Park, USA. Coral Reefs 2000, 19, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halford, A.; Cheal, A.; Ryan DWilliams, D.M. Resilience to large-scale disturbance in coral and fish assemblages on the Great Barrier Reef. Ecology 2004, 85, 1892–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, S.L.; Bahr, K.D.; Ku’ulei, S.R.; May, S.L.; McGowan, A.E.; Tsang, A.; Bumgarner, J.; Han, J.H. Evidence of acclimatization or adaptation in Hawaiian corals to higher ocean temperatures. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.D.; Wilson, S.K.; Fisher, R.; Ryan, N.M.; Babcock, R.; Blakeway, D.; Bond, T.; Dorji, P.; Dufois, F.; Fearns, P.; et al. Early recovery dynamics of turbid coral reefs after recurring bleaching events. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhmacher, H.; Loch, K.; Loch, W.; See, W.R. The aftermath of coral bleaching on a Maldivian reef—A quantitative study. Facies 2005, 51, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.C.; Wolff, N.H.; Anthony, K.R.; Devlin, M.; Lewis, S.; Mumby, P.J. Impaired recovery of the Great Barrier Reef under cumulative stress. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouezo, M.; Golbuu, Y.; Fabricius, K.; Olsudong, D.; Mereb, G.; Nestor, V.; Wolanski, E.; Harrison, P.; Doropoulos, C. Drivers of recovery and reassembly of coral reef communities. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20182908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.; Tebbett, B.; Morais, A.; Bellwood, R. Natural recovery of corals after severe disturbance. Ecol. Lett. 2024, 27, e14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieler, K. Limiting global warming to 2 °C is unlikely to save most coral reefs. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loya, Y.; Sakai, K.; Yamazato, K.; Nakano, Y.; Sambali, H.; Van Woesik, R. Coral bleaching: The winners and the losers. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Woesik, R.; Sakai, K.; Ganase, A.; Loya, Y. Revisiting the winners and the losers a decade after coral bleaching. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 434, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancrazi, I.; Feairheller, K.; Ahmed, H.; di Napoli, C.; Montefalcone, M. Active coral restoration to preserve the biodiversity of a highly impacted reef in the Maldives. Diversity 2023, 15, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site Code | Site Name | Exposure | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Koamas Giri | Inner lagoon | 0°35.137′ N | 73°15.559′ E |

| L2 | Wiringgili house reef | Inner lagoon | 0°45.050′ N | 73°25.906′ E |

| L3 | Kuredhdhoo Finolhu | Inner lagoon | 0°39.498′ N | 73°26.096′ E |

| L4 | Tippe Giri | Inner lagoon | 0°38.146′ N | 73°26.245′ E |

| O1 | Kadheddhu Beyru | Outer ocean | 0°29.447′ N | 72°59.075′ E |

| O2 | Kooddoo Beyru | Outer ocean | 0°44.368′ N | 73°26.355′ E |

| O3 | Nilandhoo Beyru | Outer ocean | 0°38.108′ N | 73°27.232′ E |

| O4 | Mahadhdhoo Beyru | Outer ocean | 0°34.996′ N | 73°31.119′ E |

| PERMANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Df | SS | R2 | F | p | |

| Year | 1 | 3.002 | 0.222 | 54.648 | 0.001 | |

| Exposure | 1 | 1.635 | 0.121 | 29.752 | 0.001 | |

| Depth | 2 | 0.530 | 0.039 | 4.821 | 0.001 | |

| Year × Exposure | 1 | 0.256 | 0.019 | 4.662 | 0.005 | |

| Year × Depth | 2 | 0.056 | 0.004 | 0.511 | 0.817 | |

| Exposure × Depth | 2 | 0.604 | 0.045 | 5.497 | 0.001 | |

| Year × Exposure × Depth | 2 | 0.167 | 0.0123 | 1.517 | 0.164 | |

| Residual | 132 | 7.252 | 0.537 | |||

| Total | 143 | 13.501 | 1.000 | |||

| Pairwise Test (Year × Exposure) | ||||||

| Pairs | SS | F. Model | R2 | p | p adj | |

| 2009 Lagoon vs. 2009 Ocean | 0.590 | 8.448 | 0.108 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |

| 2009 Lagoon vs. 2020 Lagoon | 1.324 | 19.586 | 0.219 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |

| 2009 Ocean vs. 2020 Ocean | 1.934 | 34.935 | 0.333 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |

| 2020 Lagoon vs. 2020 Ocean | 1.301 | 24.483 | 0.259 | 0.001 | 0.006 | |

| Pairwise Test (Exposure × Depth) | ||||||

| Pairs | SS | F. Model | R2 | p | p adj | |

| F Lagoon vs. U Lagoon | 0.124 | 1.591 | 0.033 | 0.203 | 1 | |

| F Lagoon vs. S Lagoon | 0.588 | 7.431 | 0.139 | 0.001 | 0.015 | |

| F Lagoon vs. F Ocean | 1.250 | 13.379 | 0.225 | 0.001 | 0.015 | |

| U Lagoon vs. S Lagoon | 0.205 | 2.567 | 0.053 | 0.064 | 0.96 | |

| U Lagoon vs. U Ocean | 0.380 | 5.150 | 0.101 | 0.005 | 0.075 | |

| S Lagoon vs. S Ocean | 0.609 | 9.199 | 0.167 | 0.001 | 0.015 | |

| F Ocean vs. U Ocean | 0.309 | 3.455 | 0.070 | 0.016 | 0.24 | |

| F Ocean vs. S Ocean | 0.450 | 5.593 | 0.108 | 0.001 | 0.015 | |

| U Ocean vs. S Ocean | 0.024 | 0.408 | 0.009 | 0.662 | 1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oprandi, A.; Mancini, I.; Azzola, A.; Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Asnaghi, V.; Montefalcone, M. Coral Recruitment and Survival in a Remote Maldivian Atoll 11 Years Apart. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2274. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122274

Oprandi A, Mancini I, Azzola A, Bianchi CN, Morri C, Asnaghi V, Montefalcone M. Coral Recruitment and Survival in a Remote Maldivian Atoll 11 Years Apart. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2274. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122274

Chicago/Turabian StyleOprandi, Alice, Ilaria Mancini, Annalisa Azzola, Carlo Nike Bianchi, Carla Morri, Valentina Asnaghi, and Monica Montefalcone. 2025. "Coral Recruitment and Survival in a Remote Maldivian Atoll 11 Years Apart" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2274. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122274

APA StyleOprandi, A., Mancini, I., Azzola, A., Bianchi, C. N., Morri, C., Asnaghi, V., & Montefalcone, M. (2025). Coral Recruitment and Survival in a Remote Maldivian Atoll 11 Years Apart. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2274. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122274