Numerical Comparison of Piston-, Flap-, and Double-Flap-Type Wave Makers in a Numerical Wave Tank

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Methodology

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Principles of Wave Generation

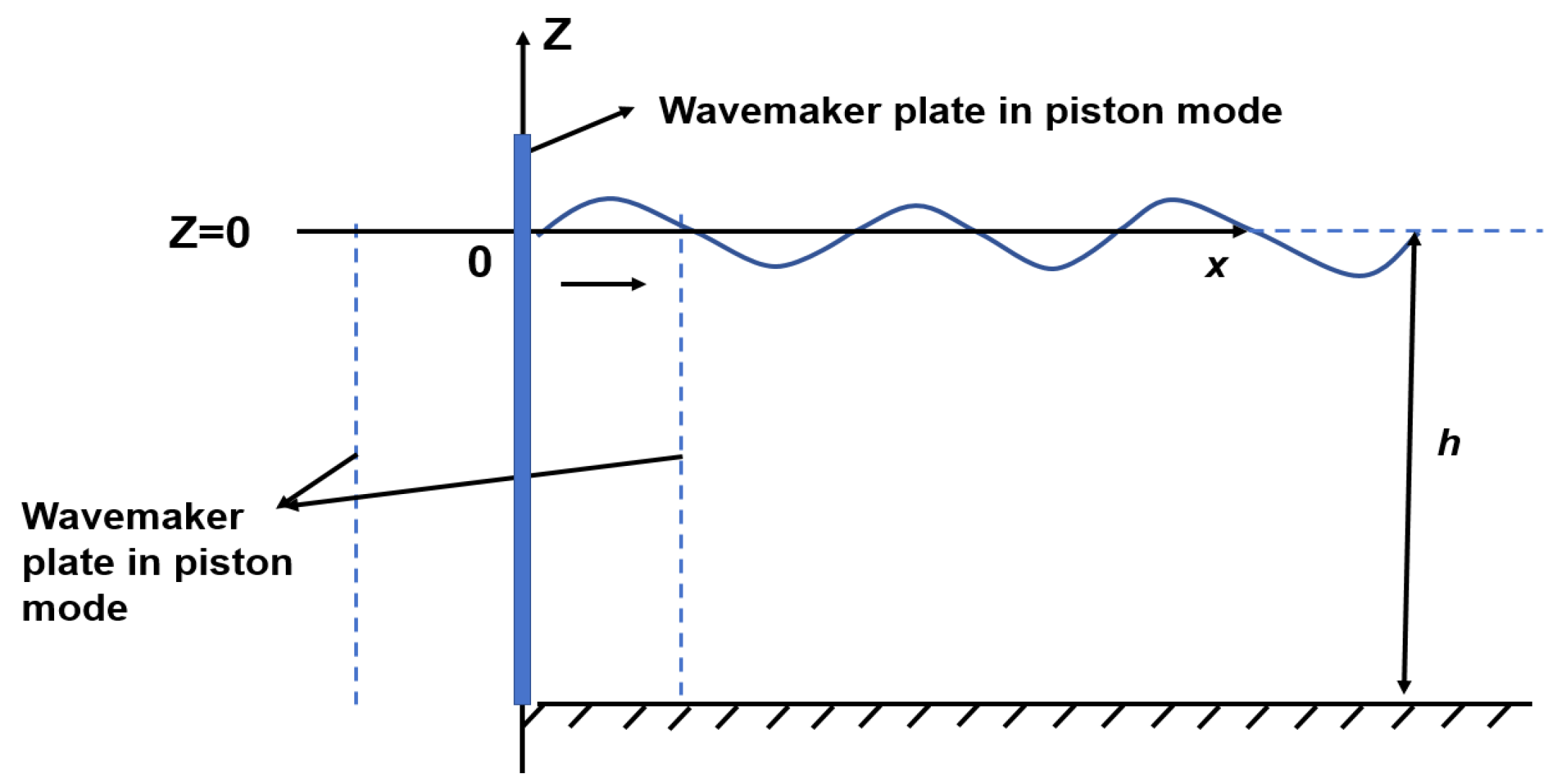

2.2.1. Piston-Type Wave Generation

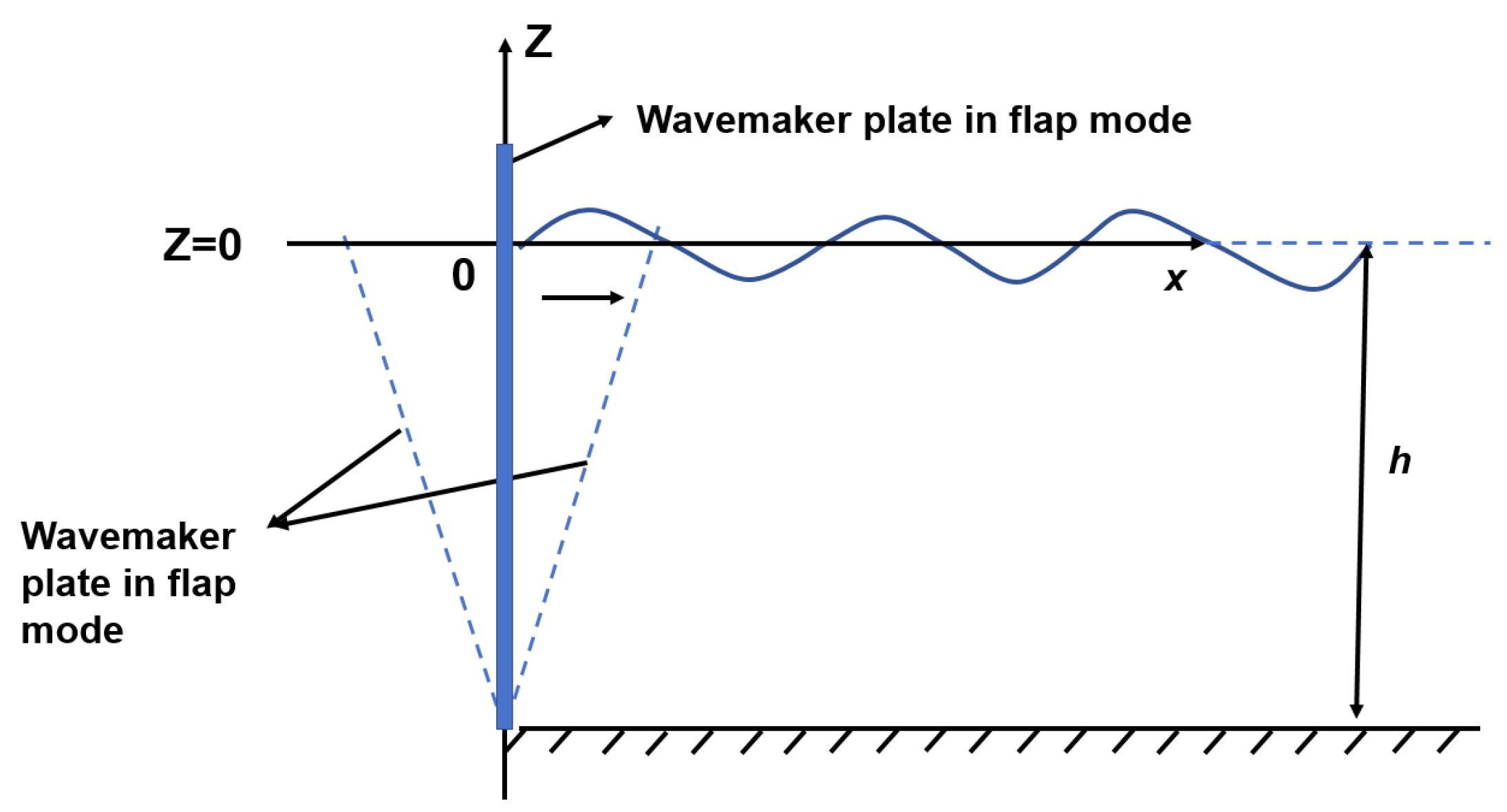

2.2.2. Flap-Type Wave Generation

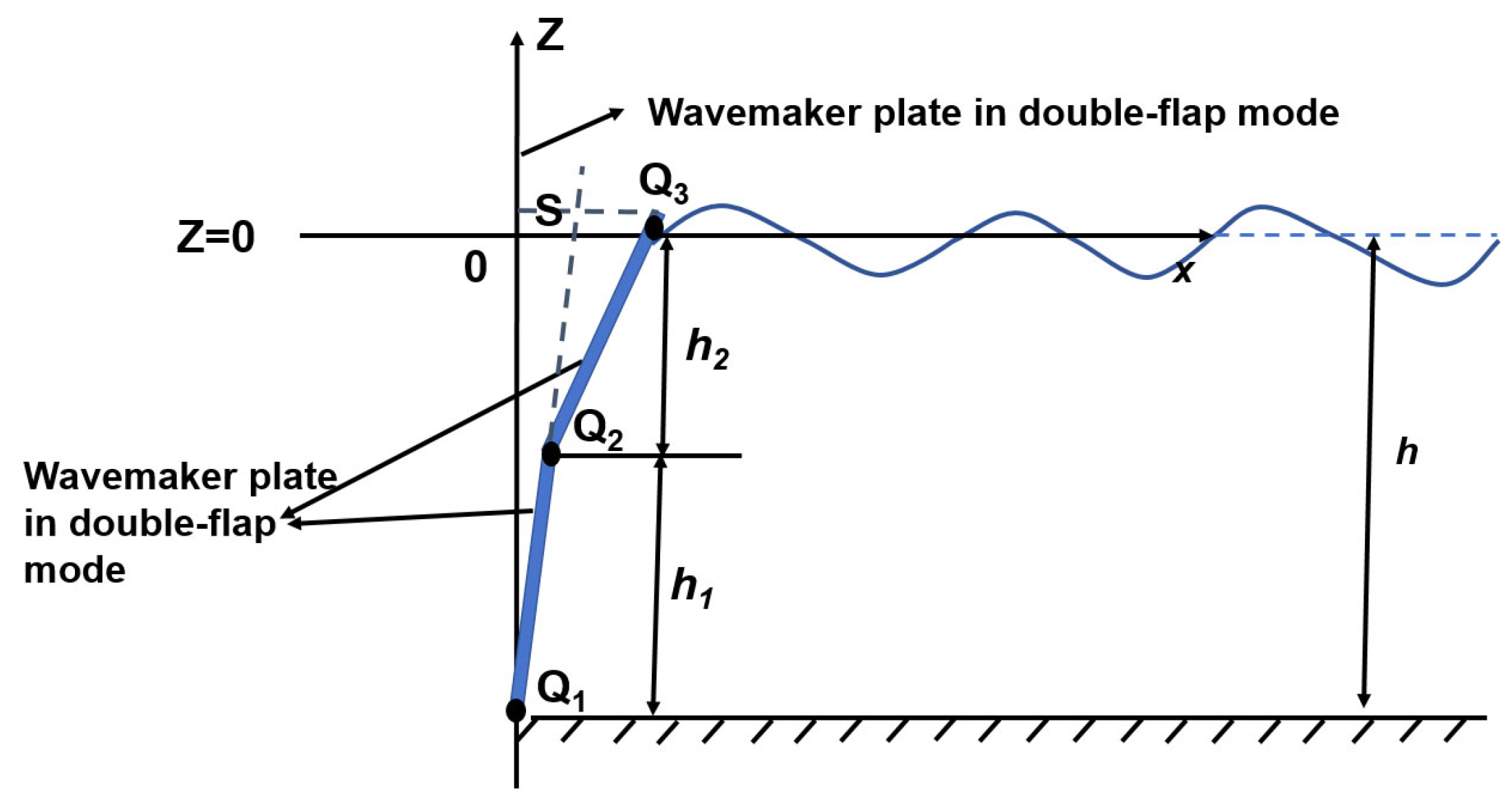

2.2.3. Double Flap-Type Wave Generation

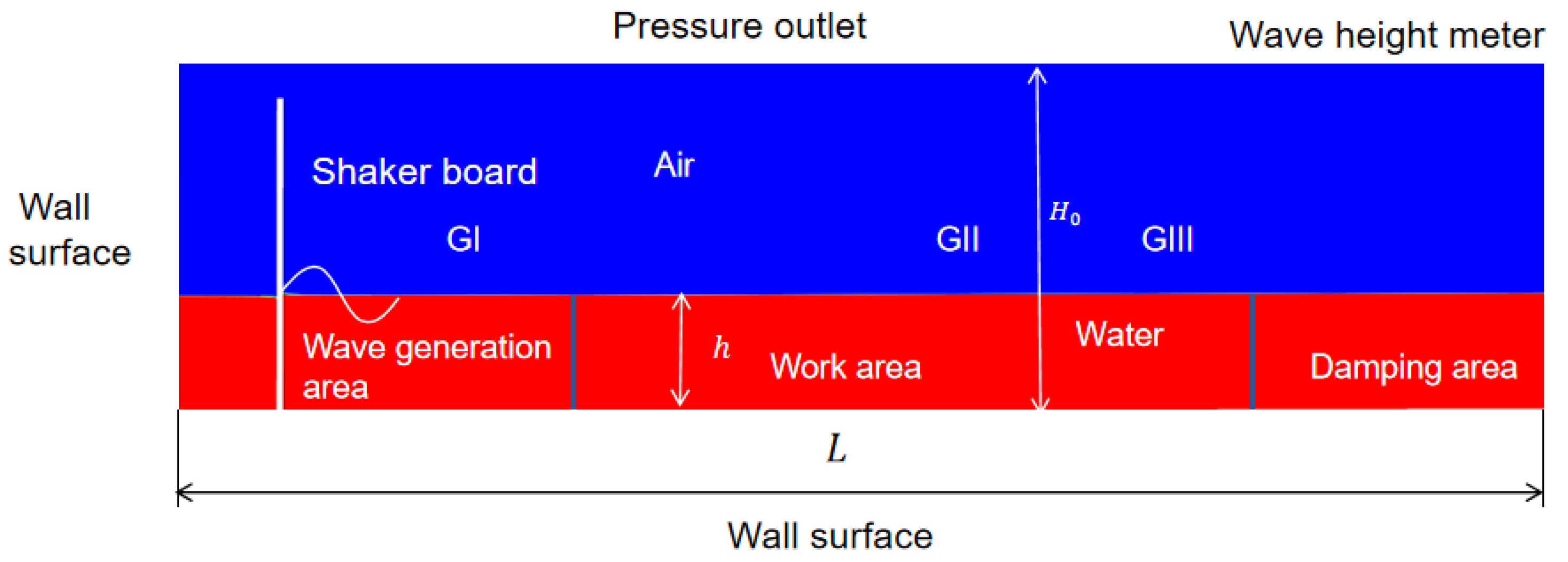

3. Numerical Modeling and Wave Generation Analysis

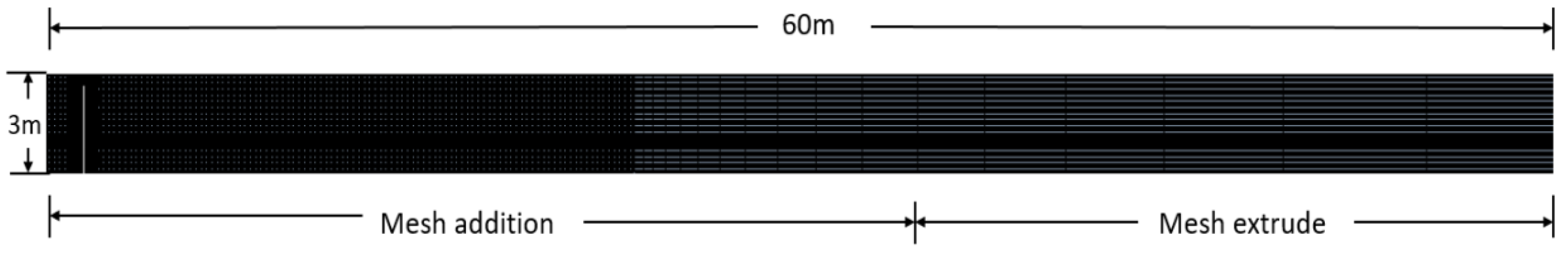

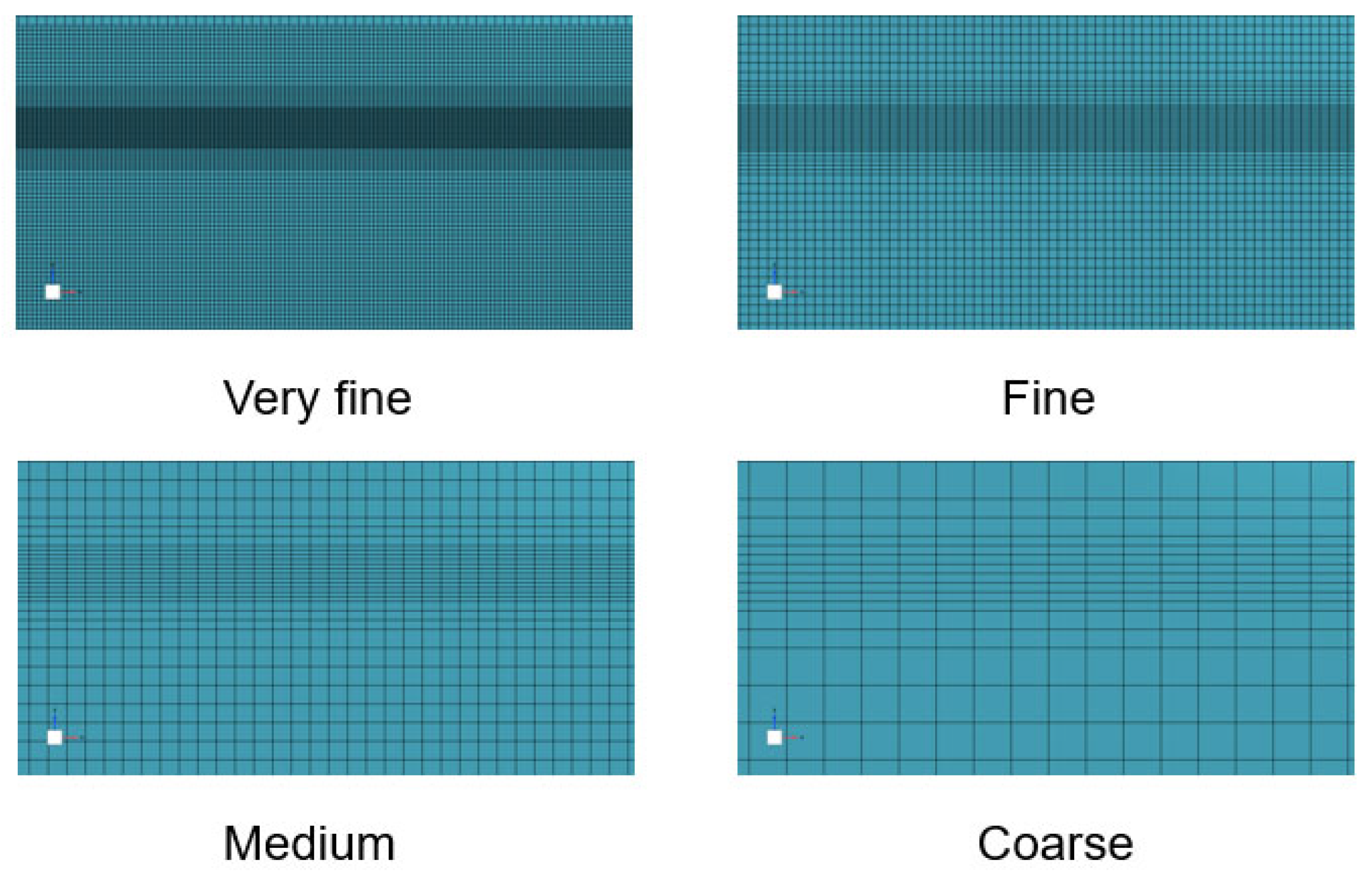

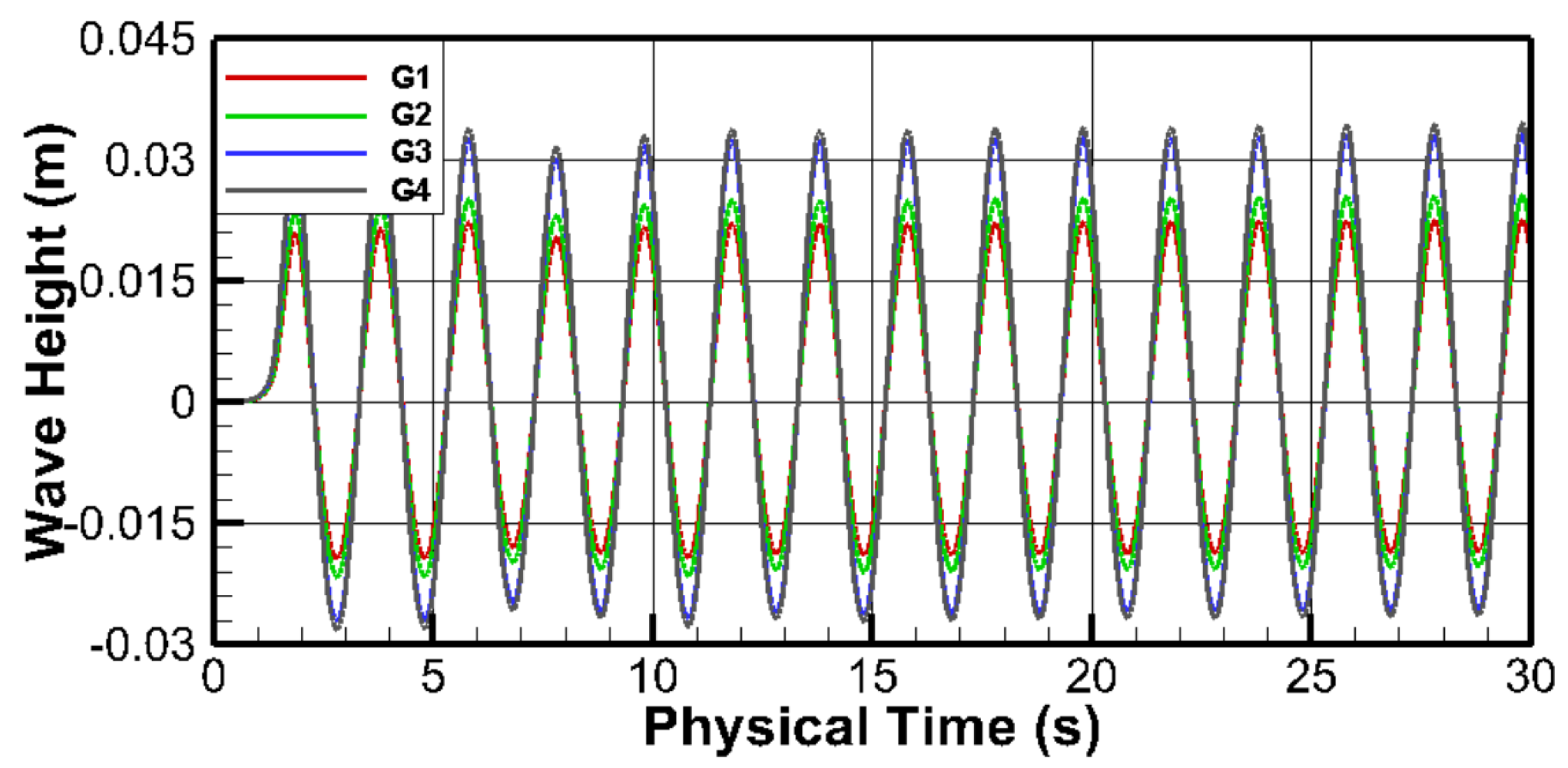

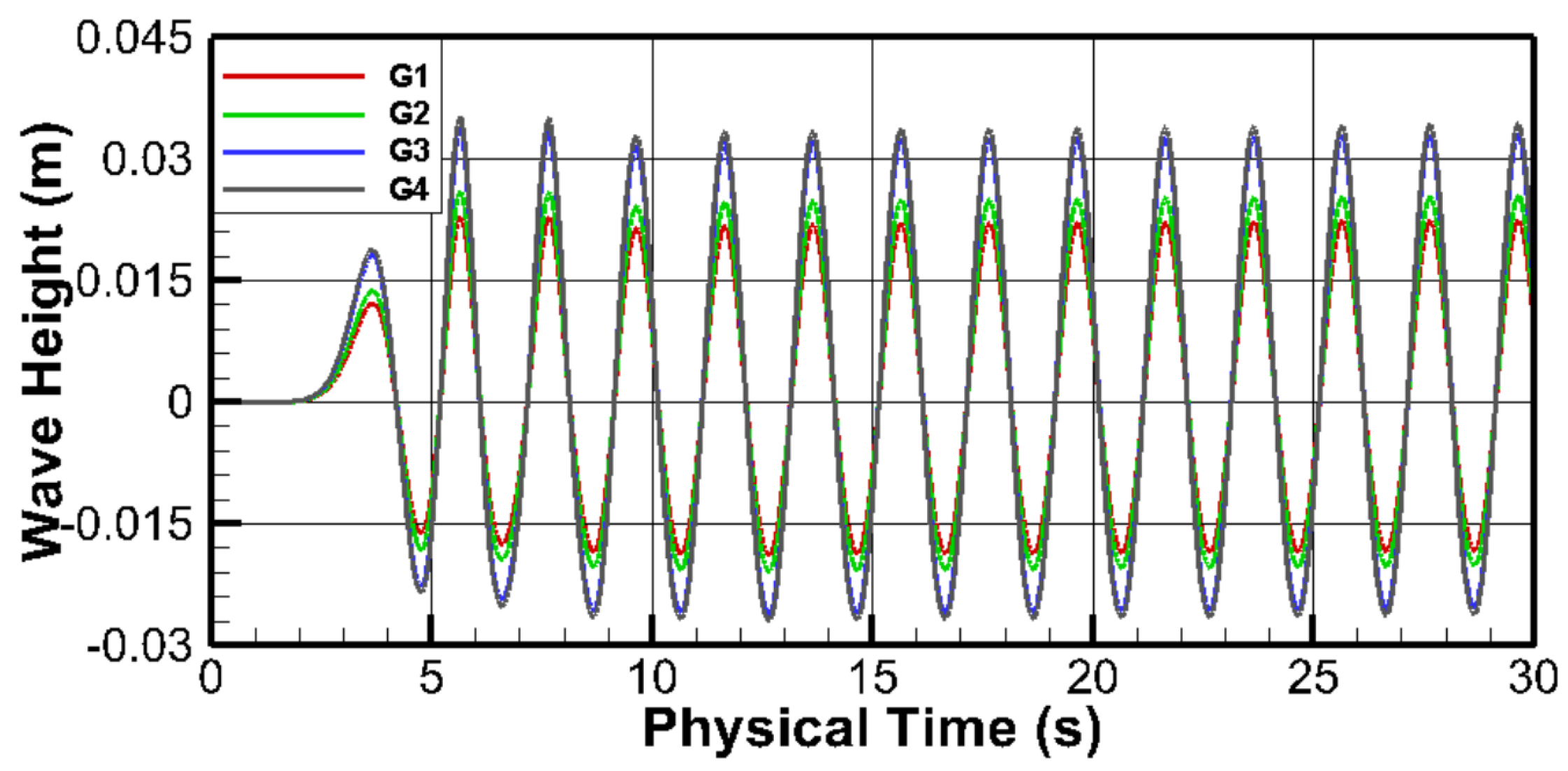

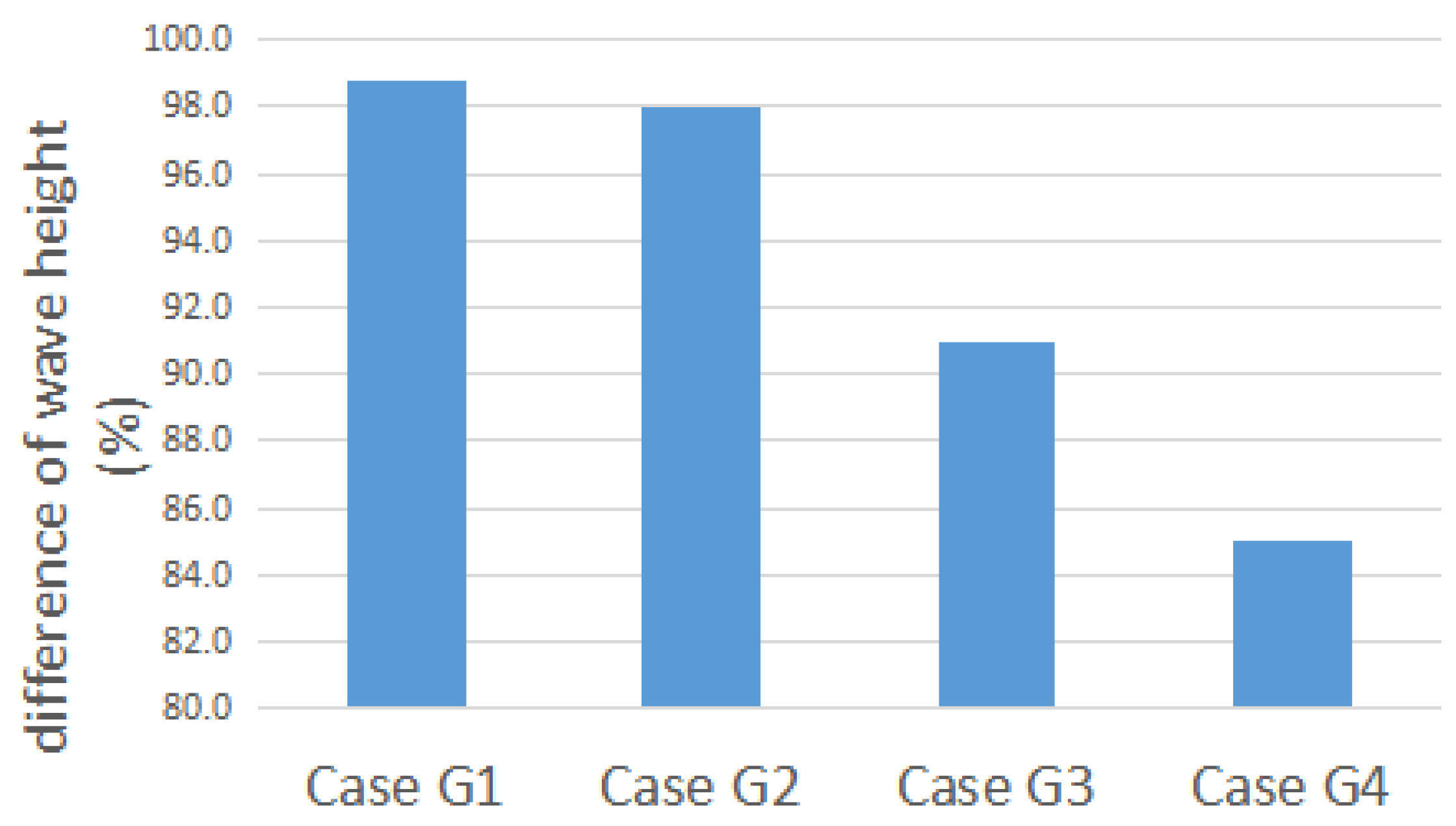

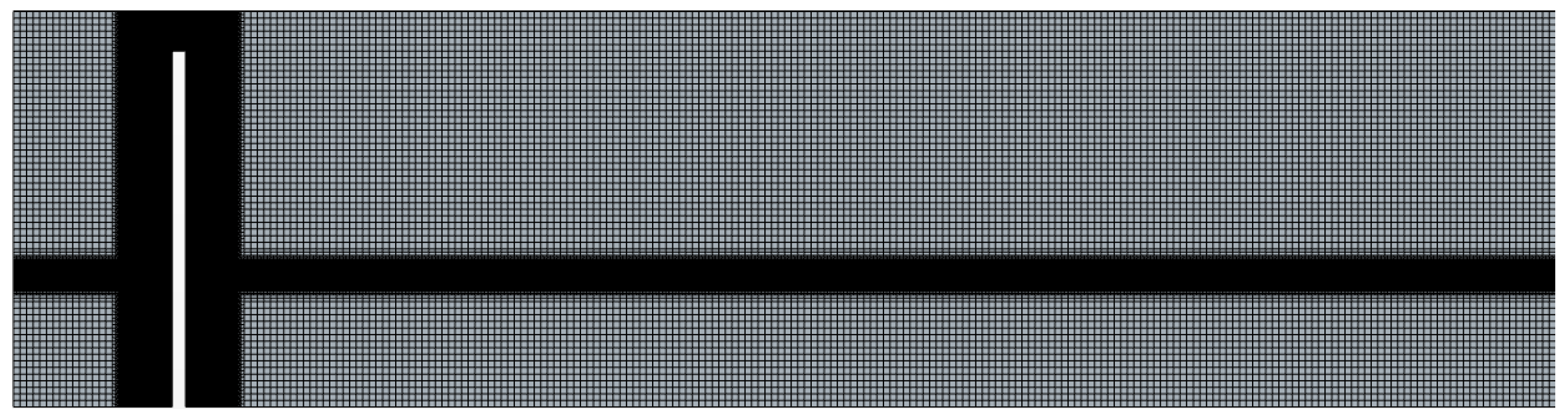

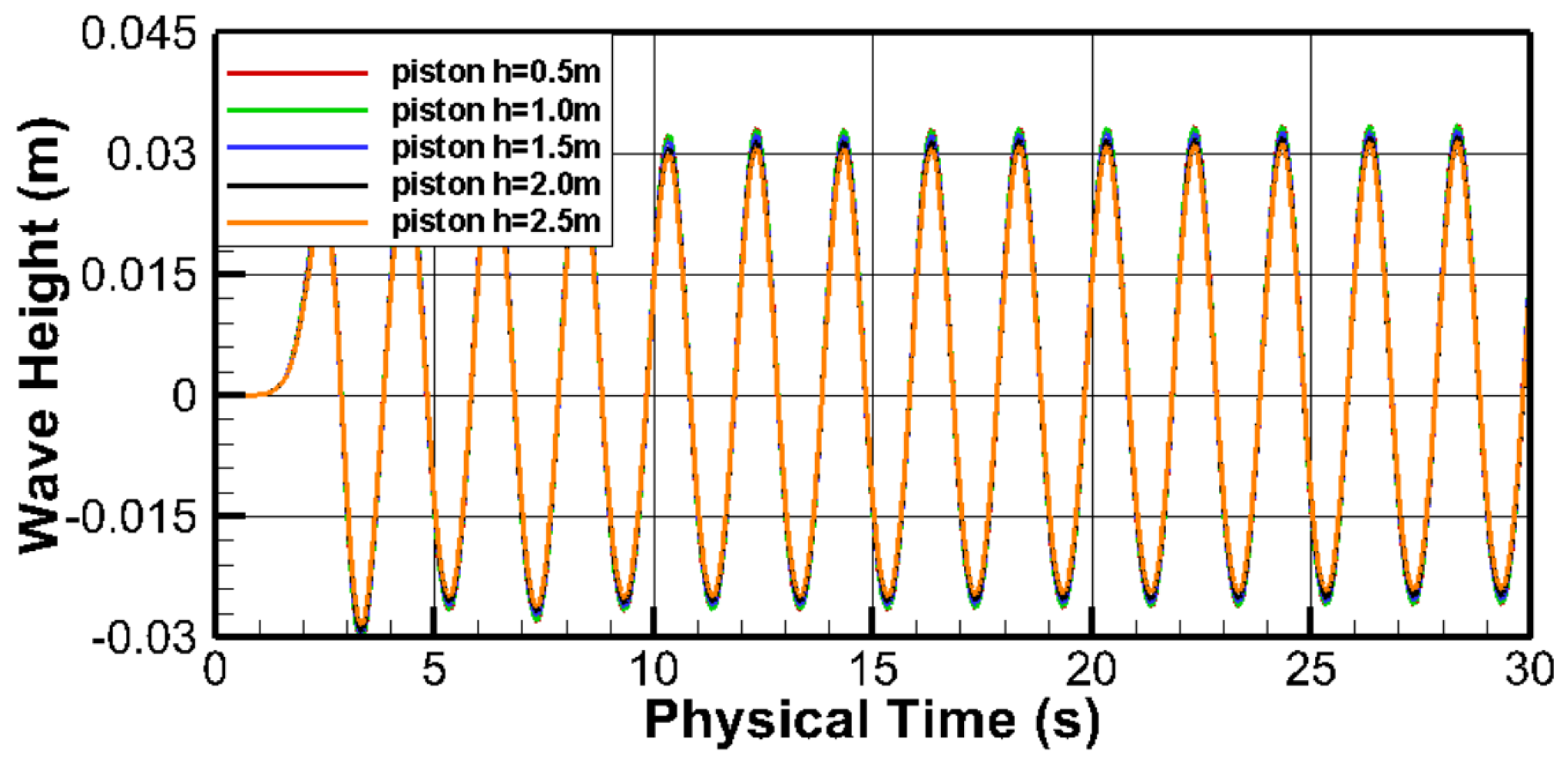

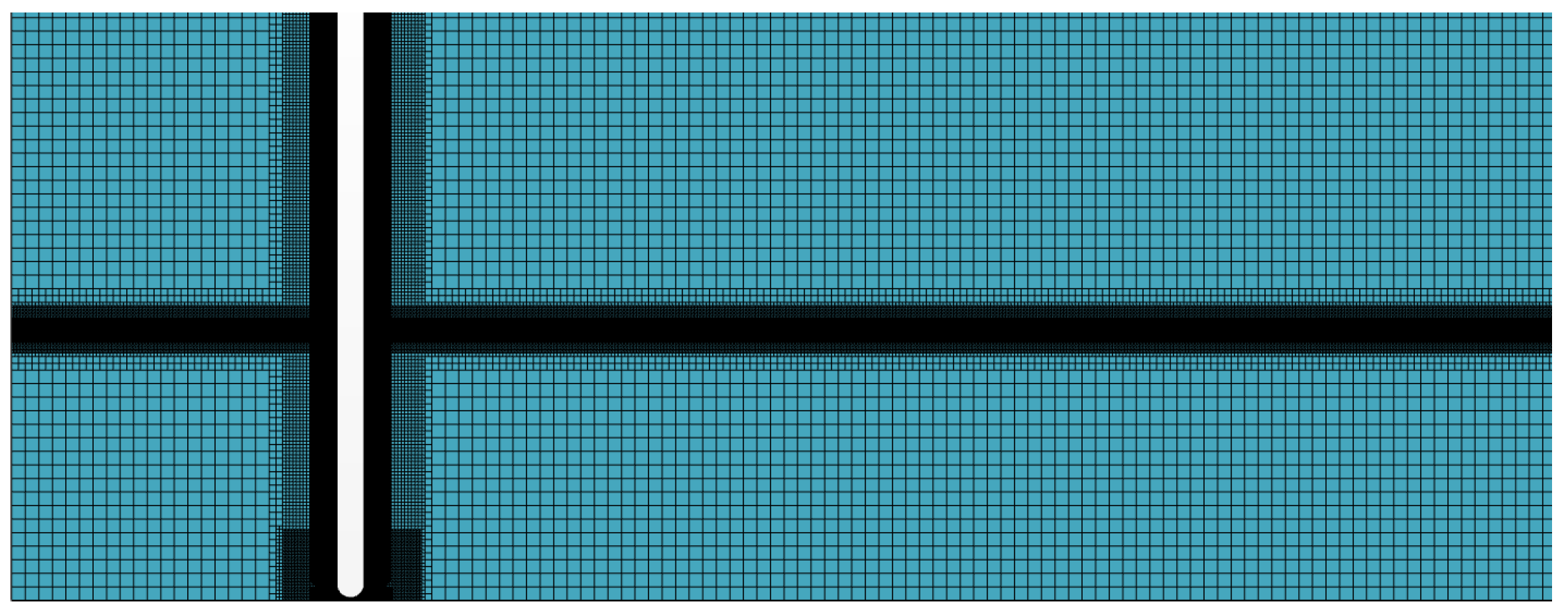

3.1. Grid Sensitivity Test

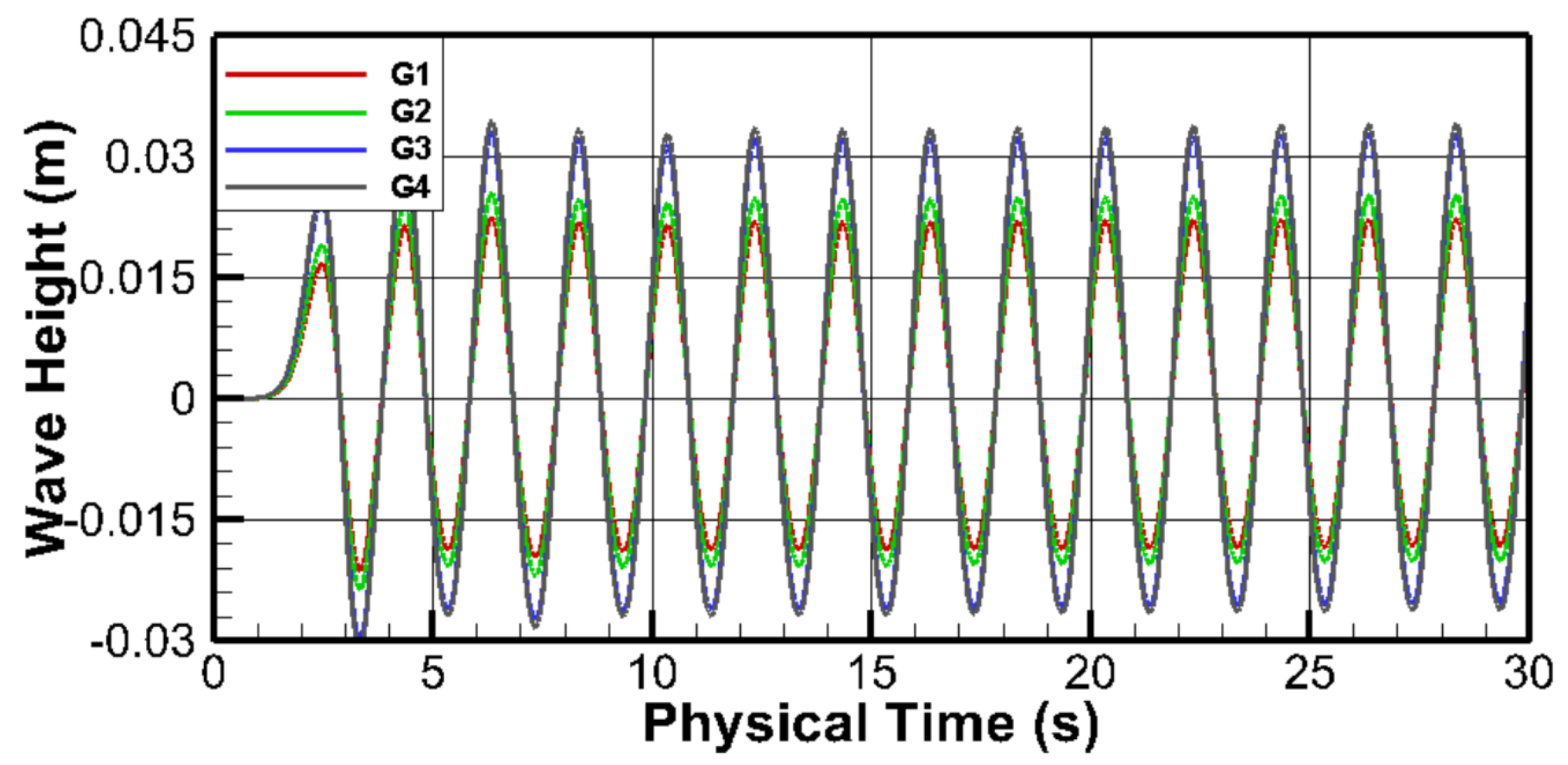

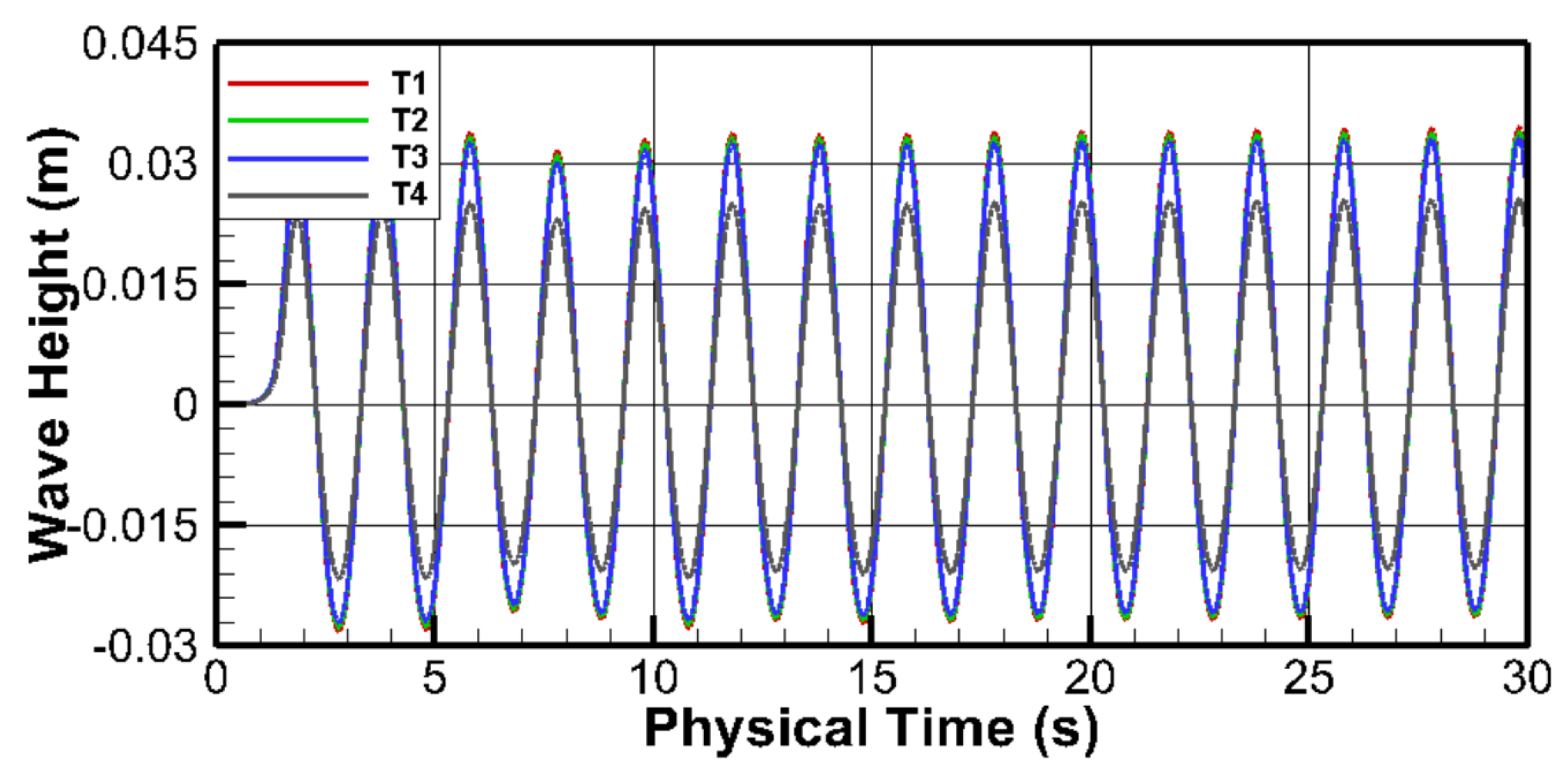

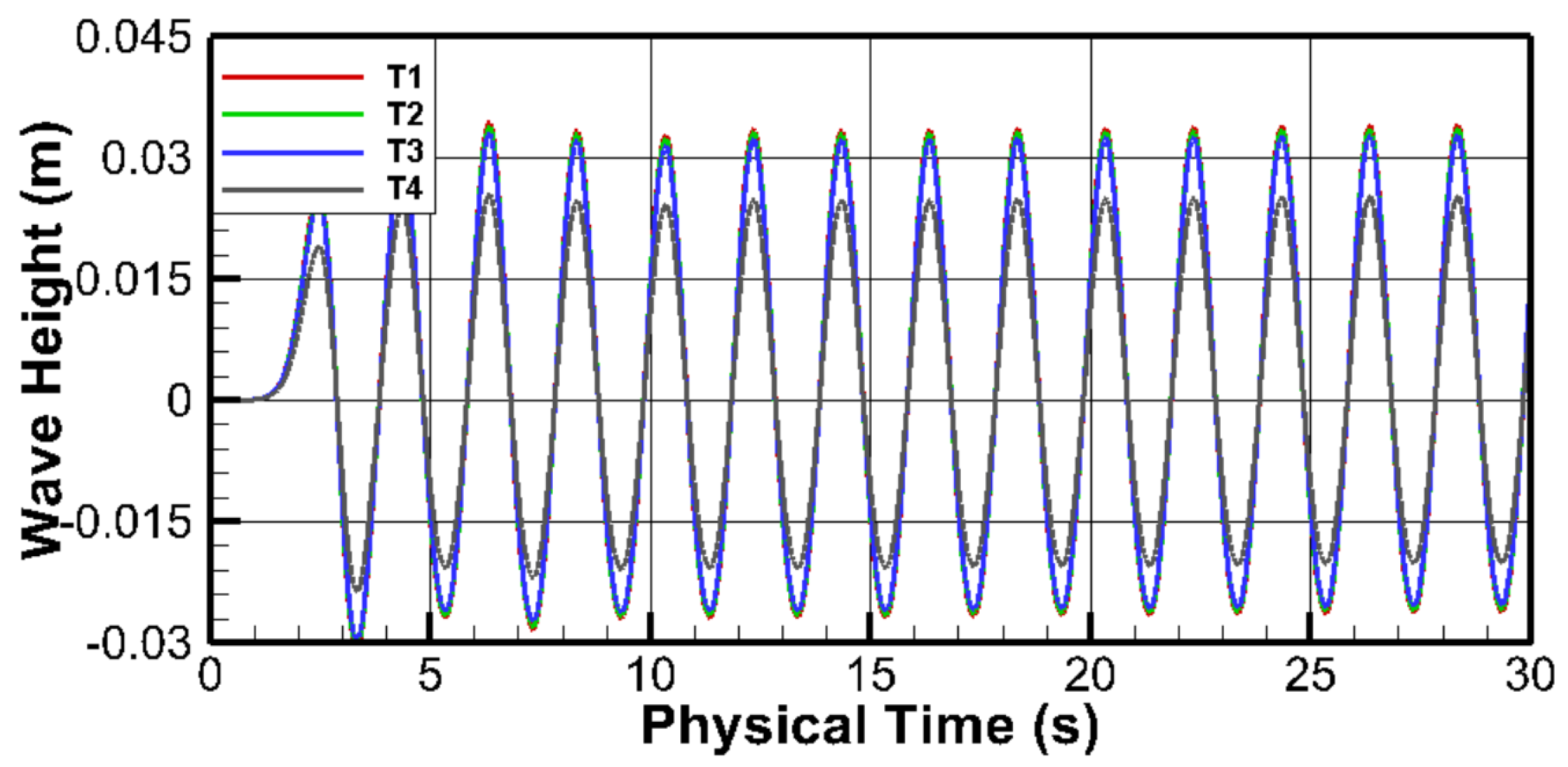

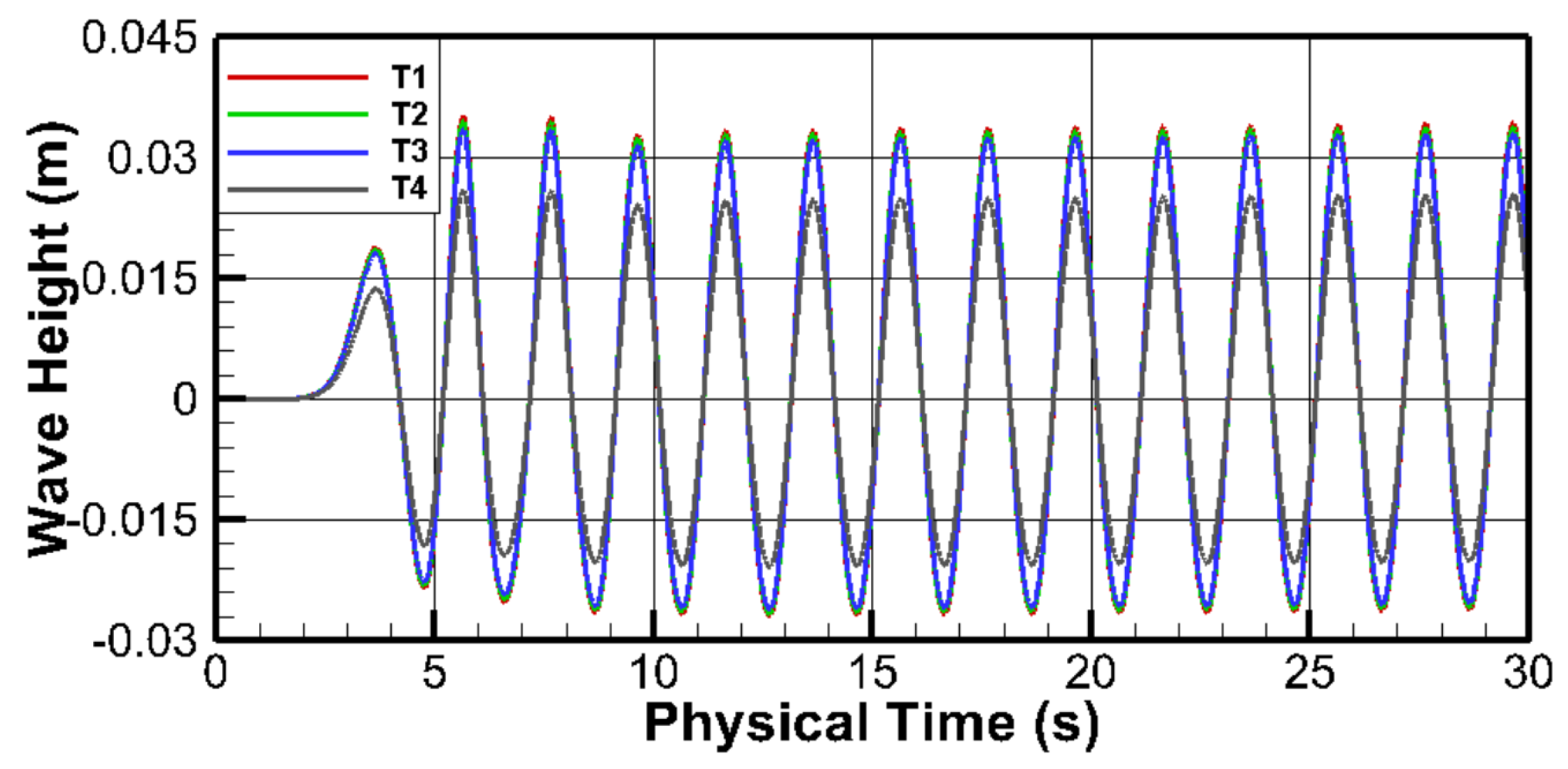

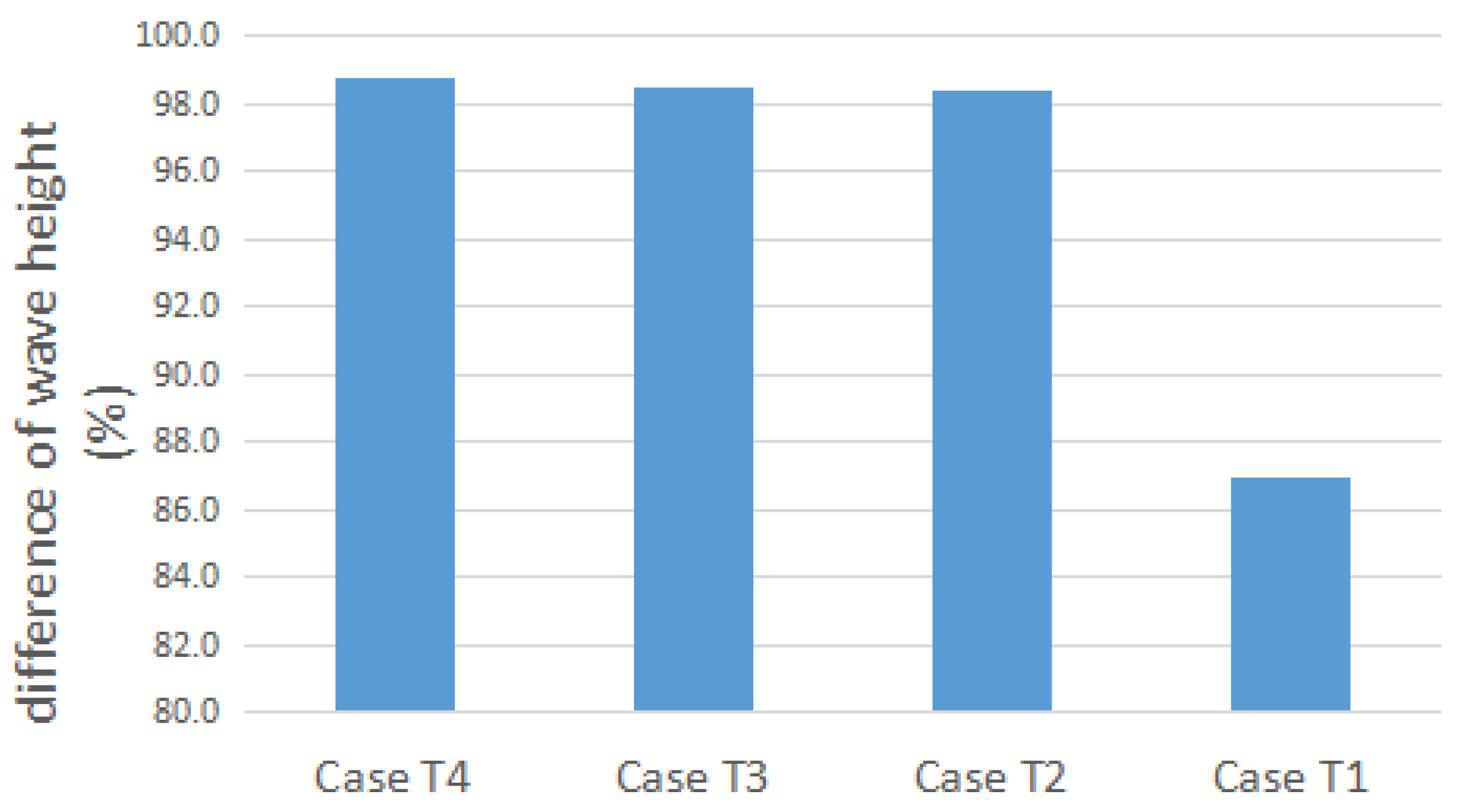

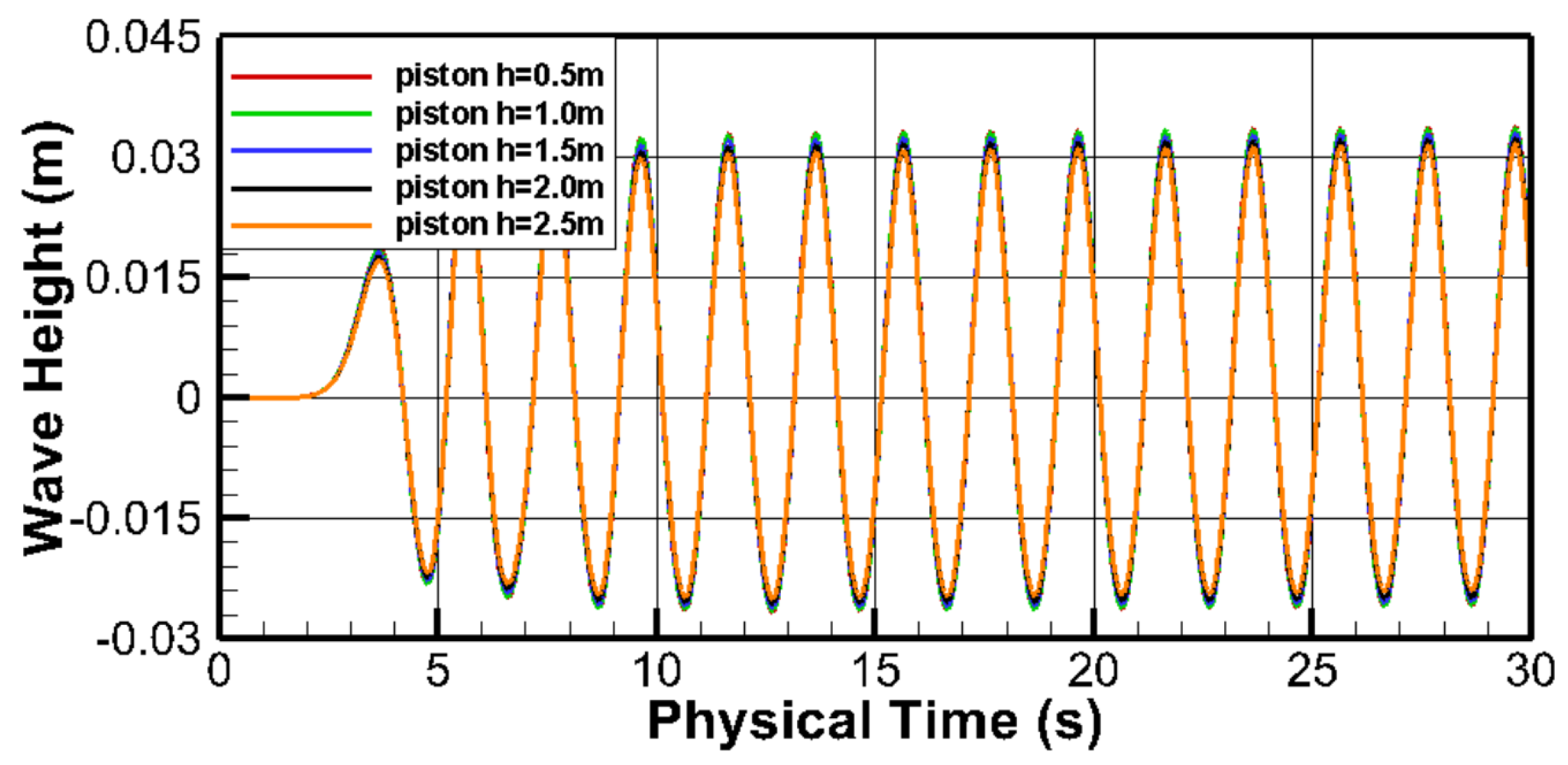

3.2. Time Step Independence Test

3.3. Piston-Type Wave Maker

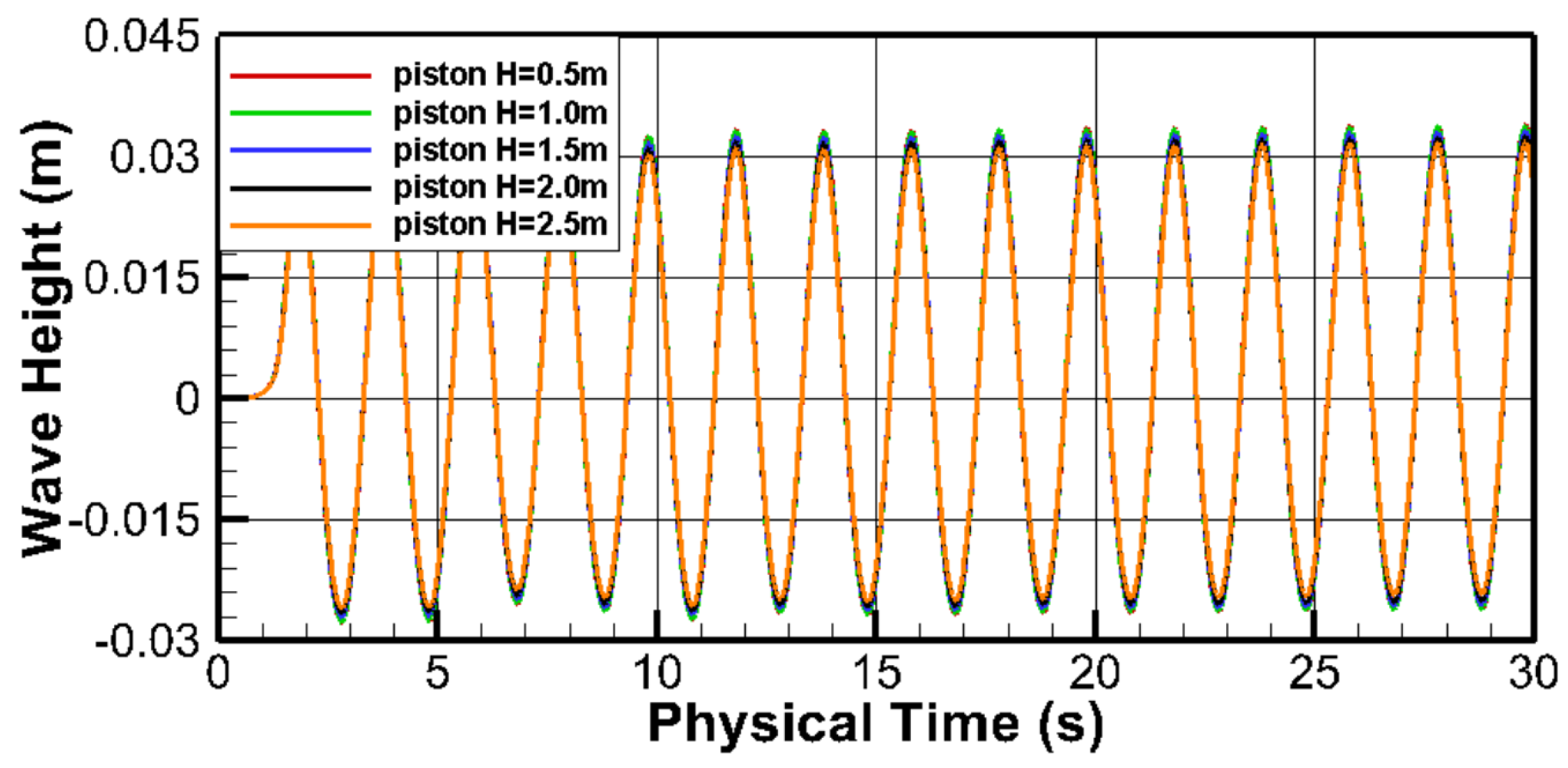

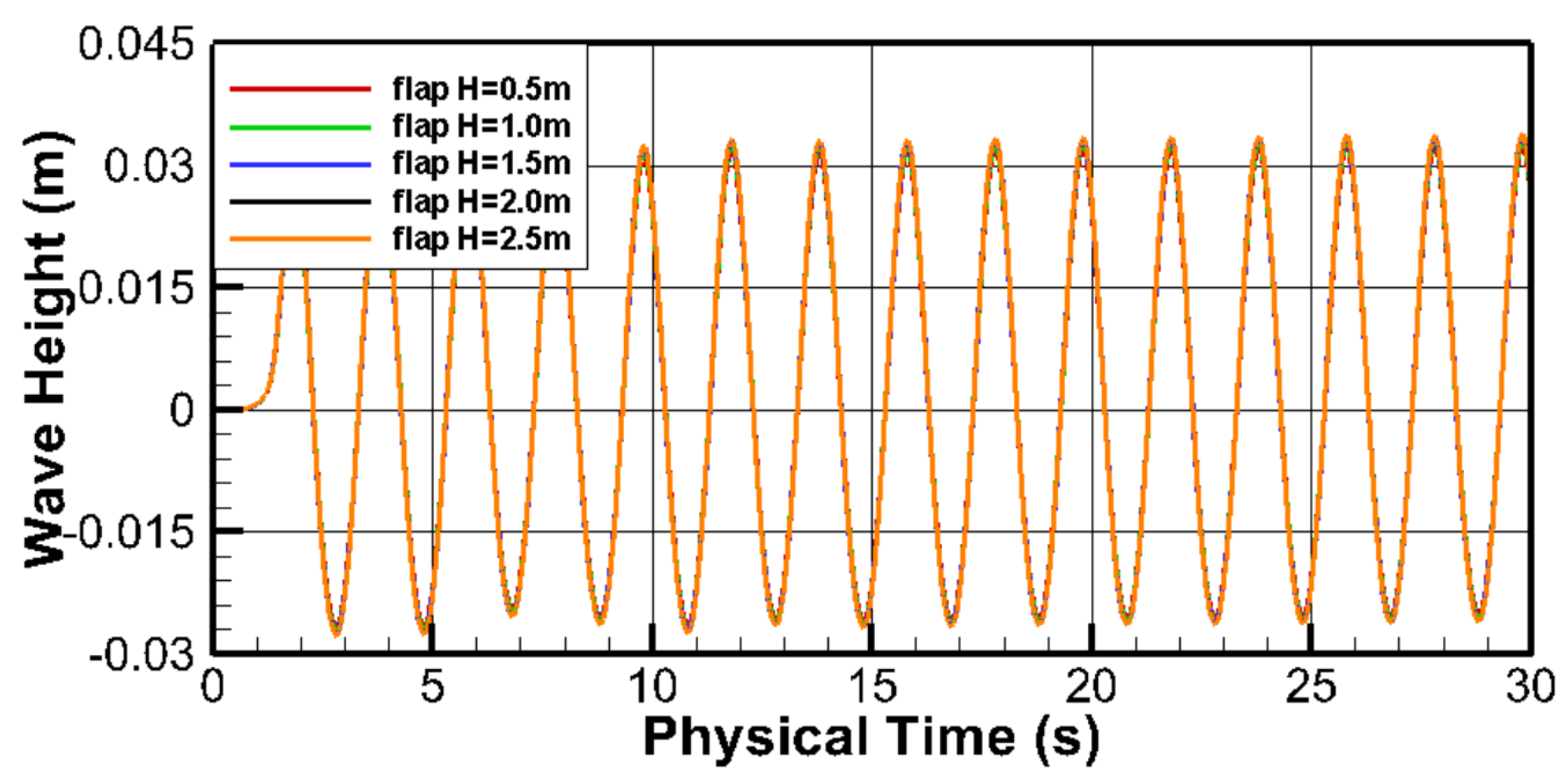

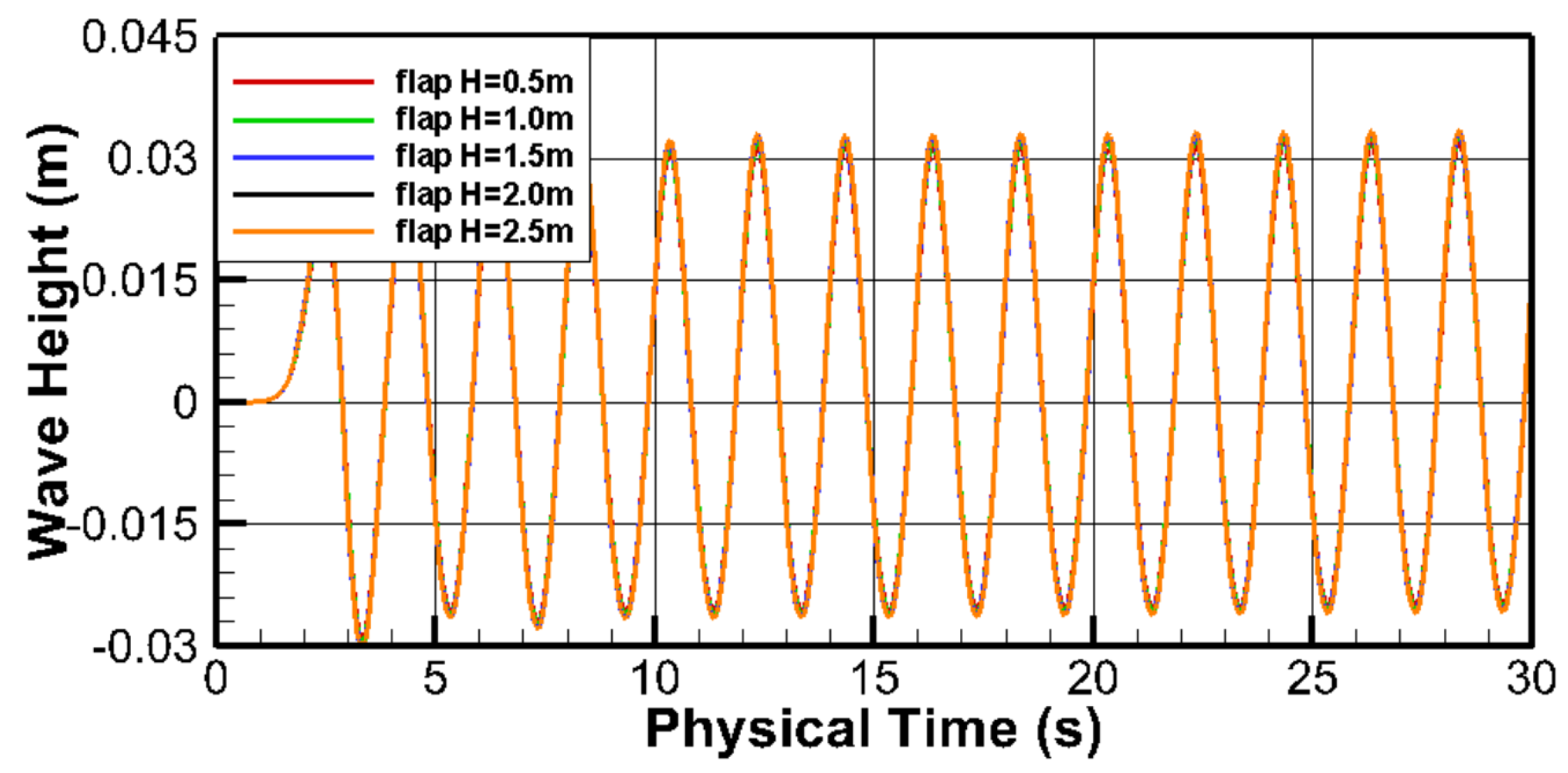

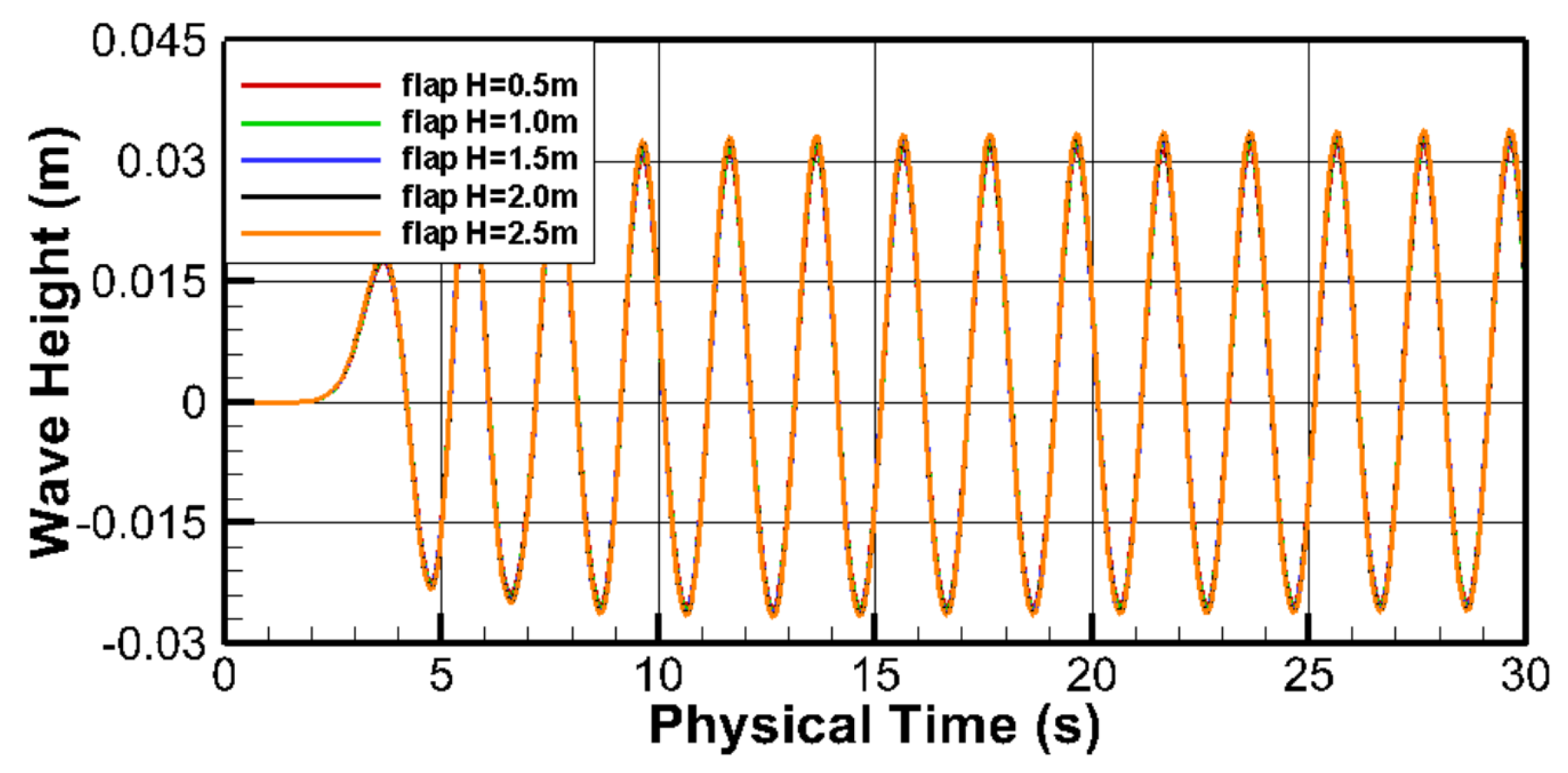

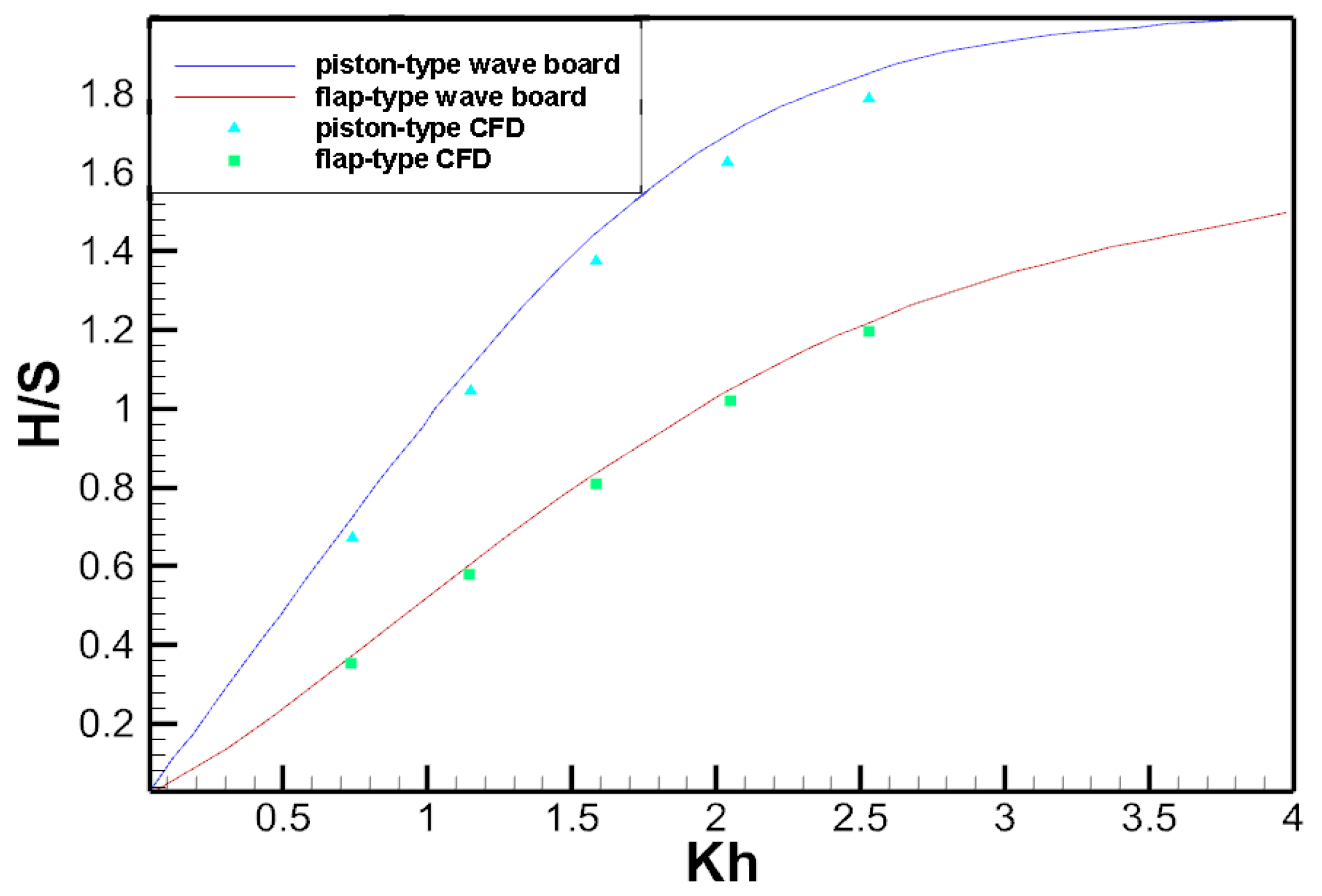

3.4. Flap-Type Wave Maker

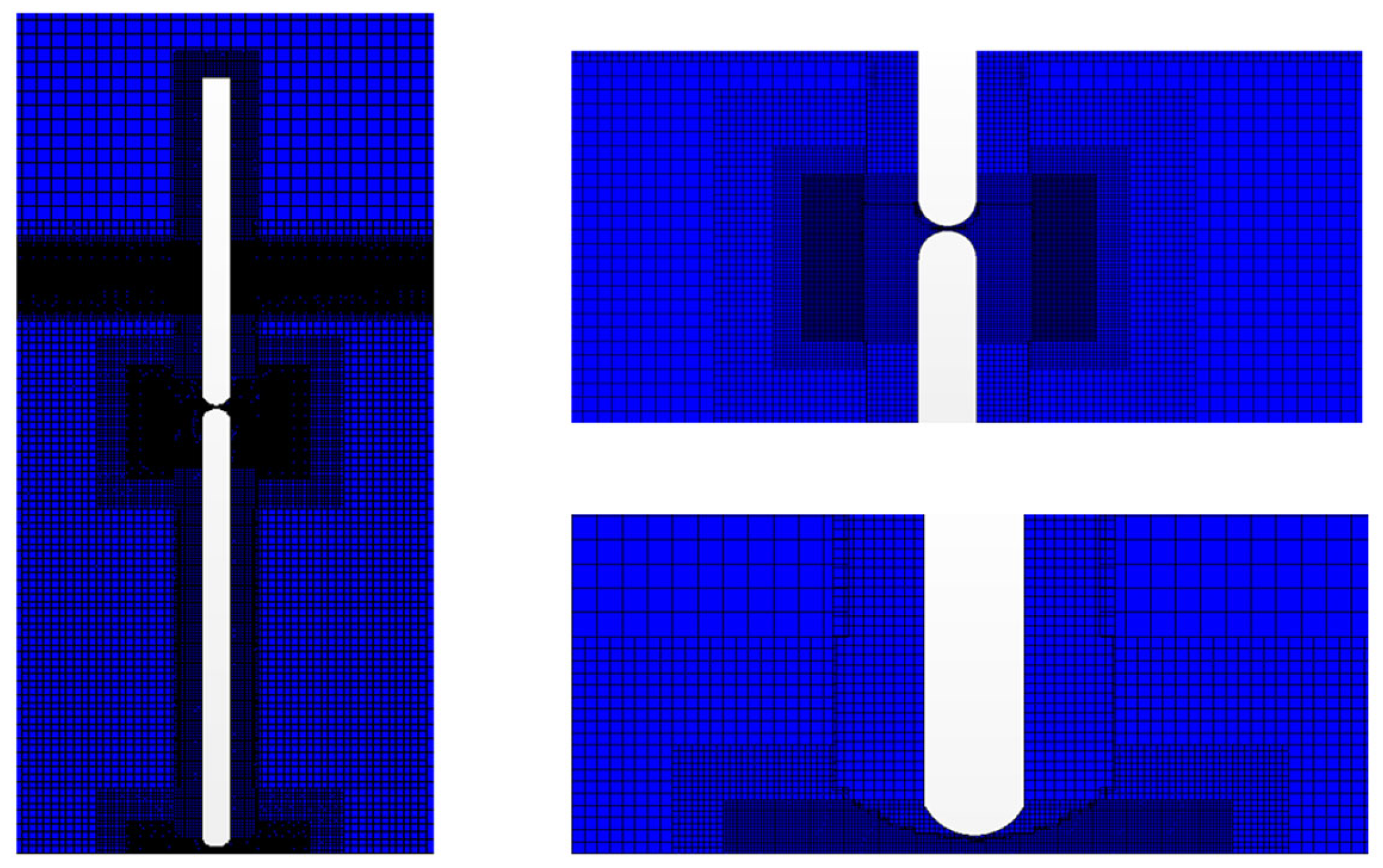

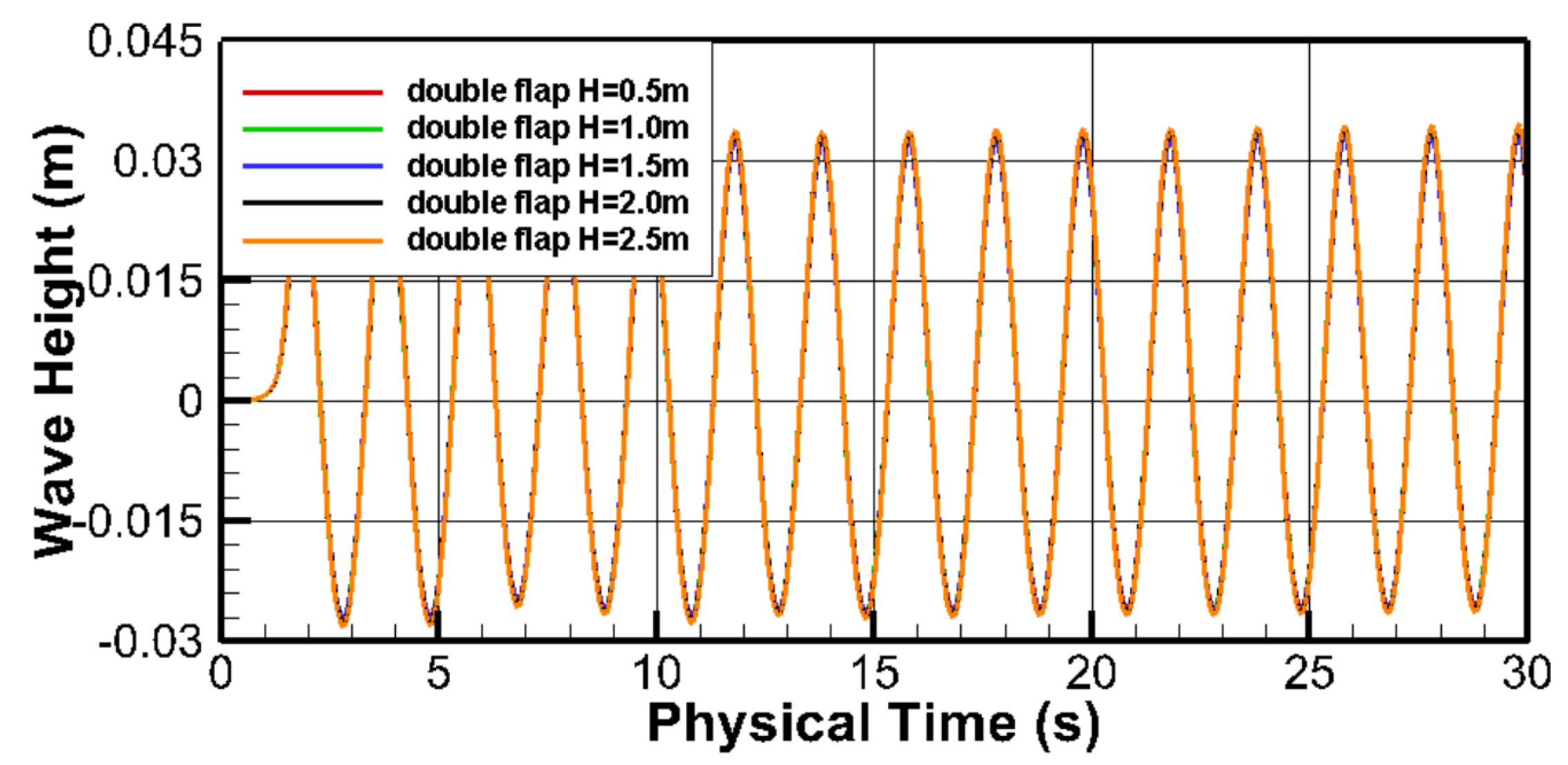

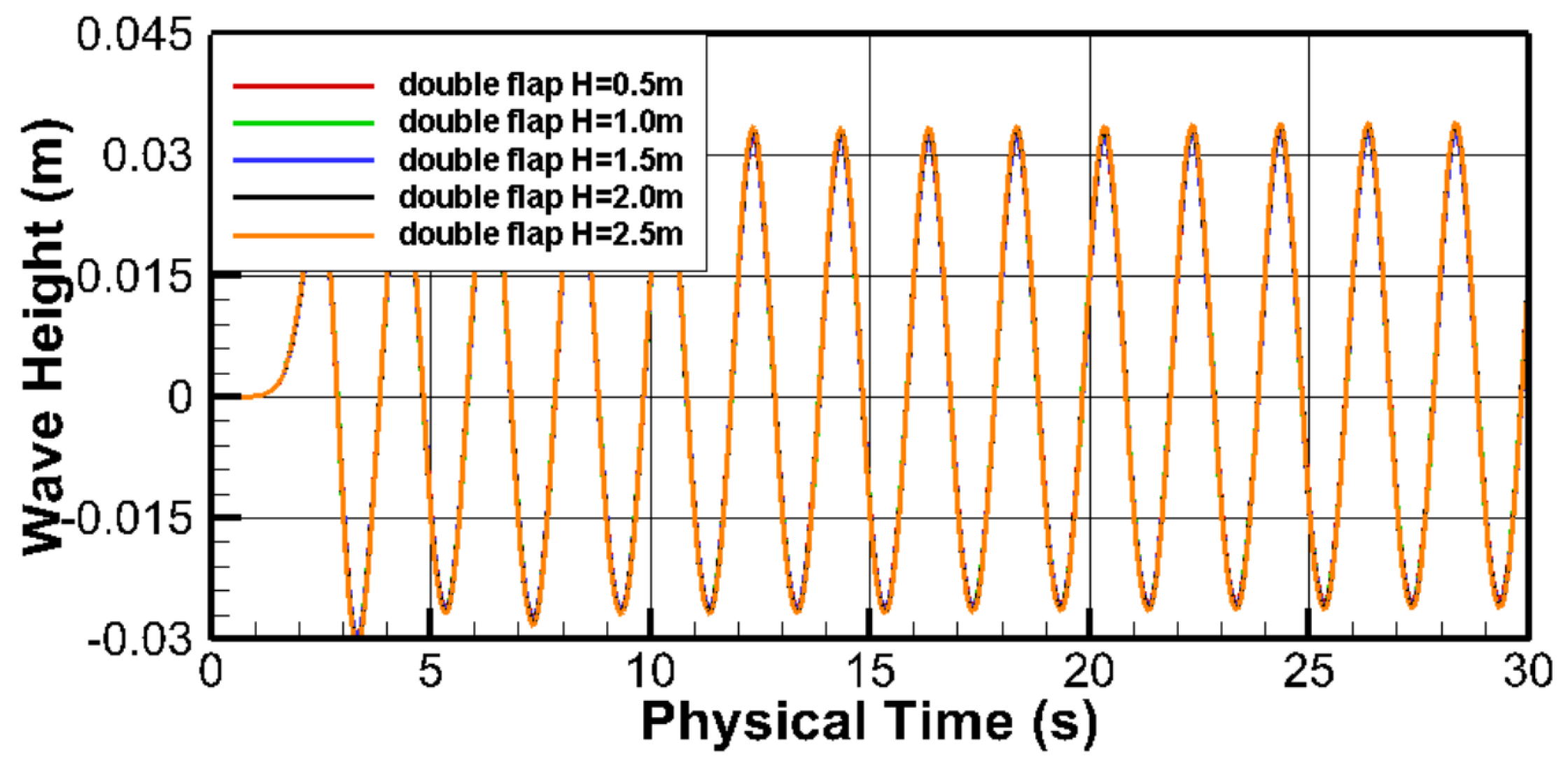

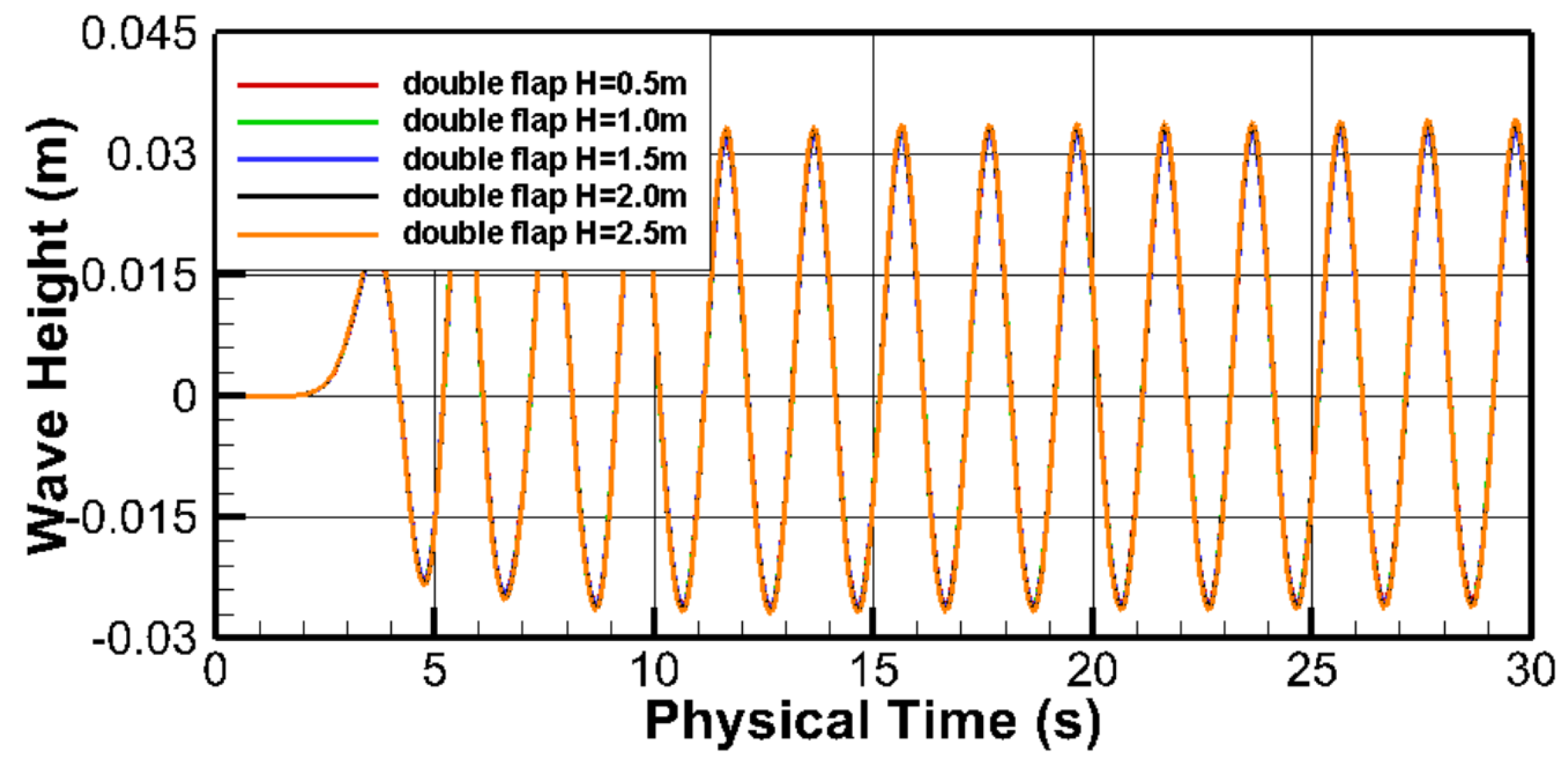

3.5. Double-Flap Wave Maker

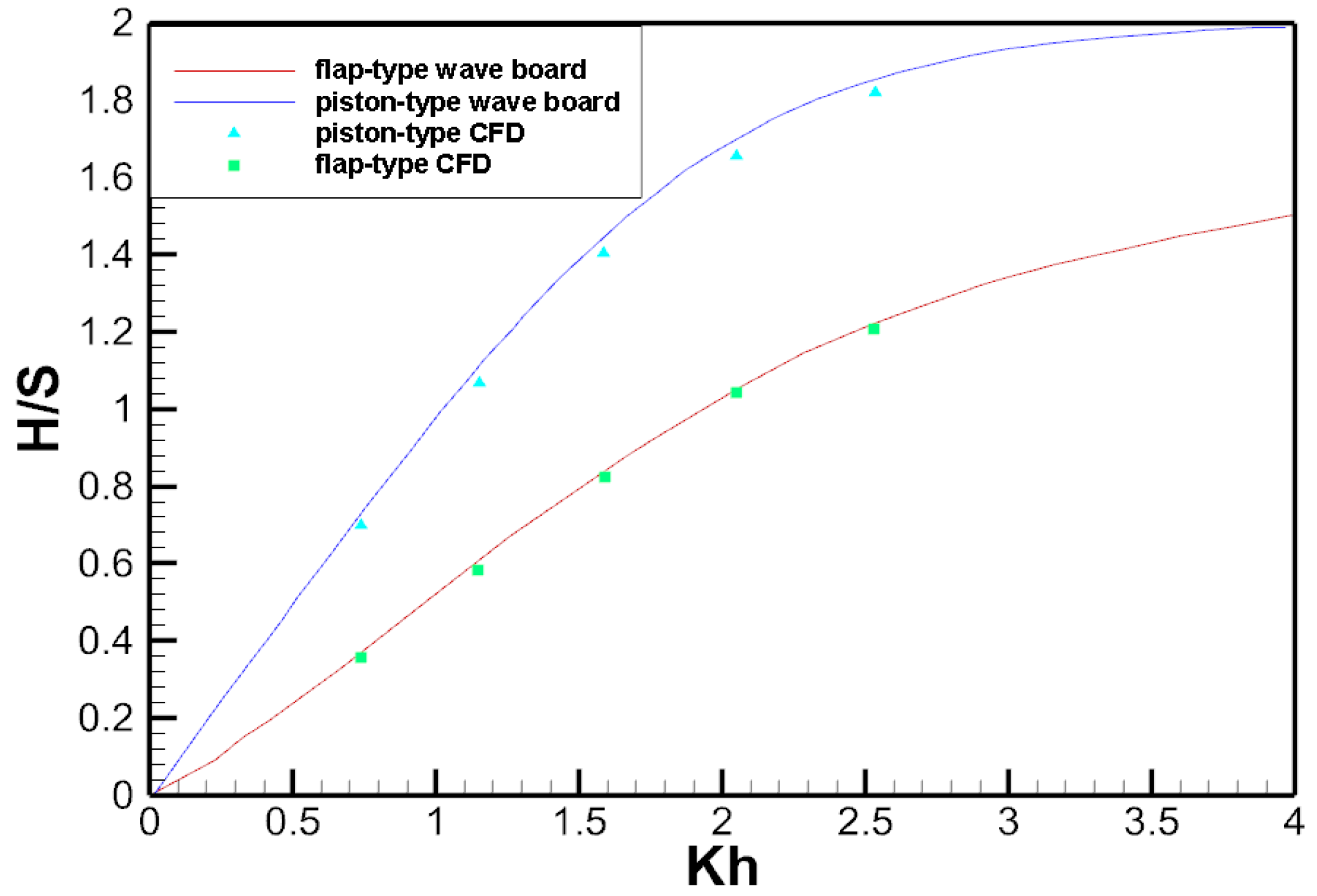

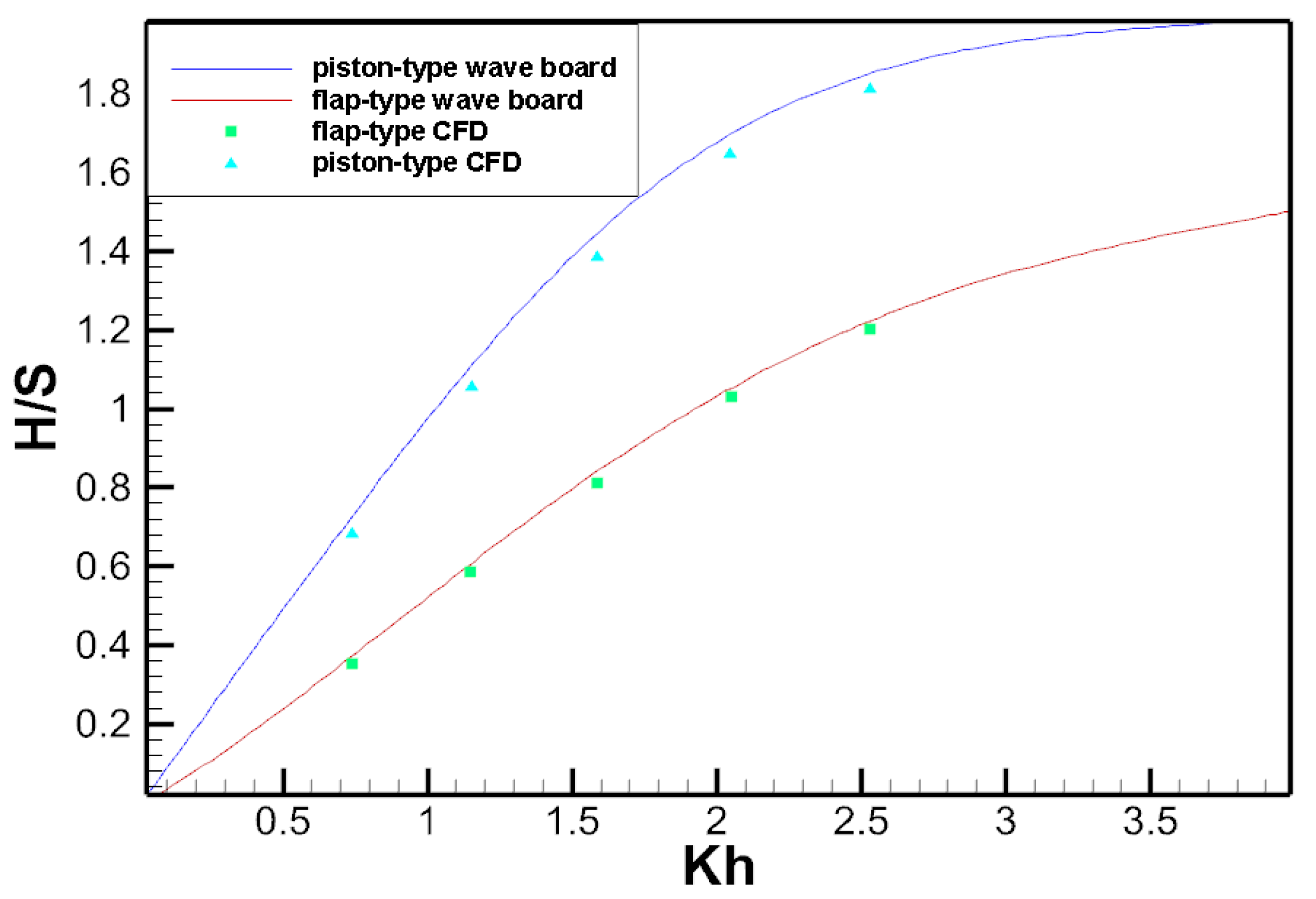

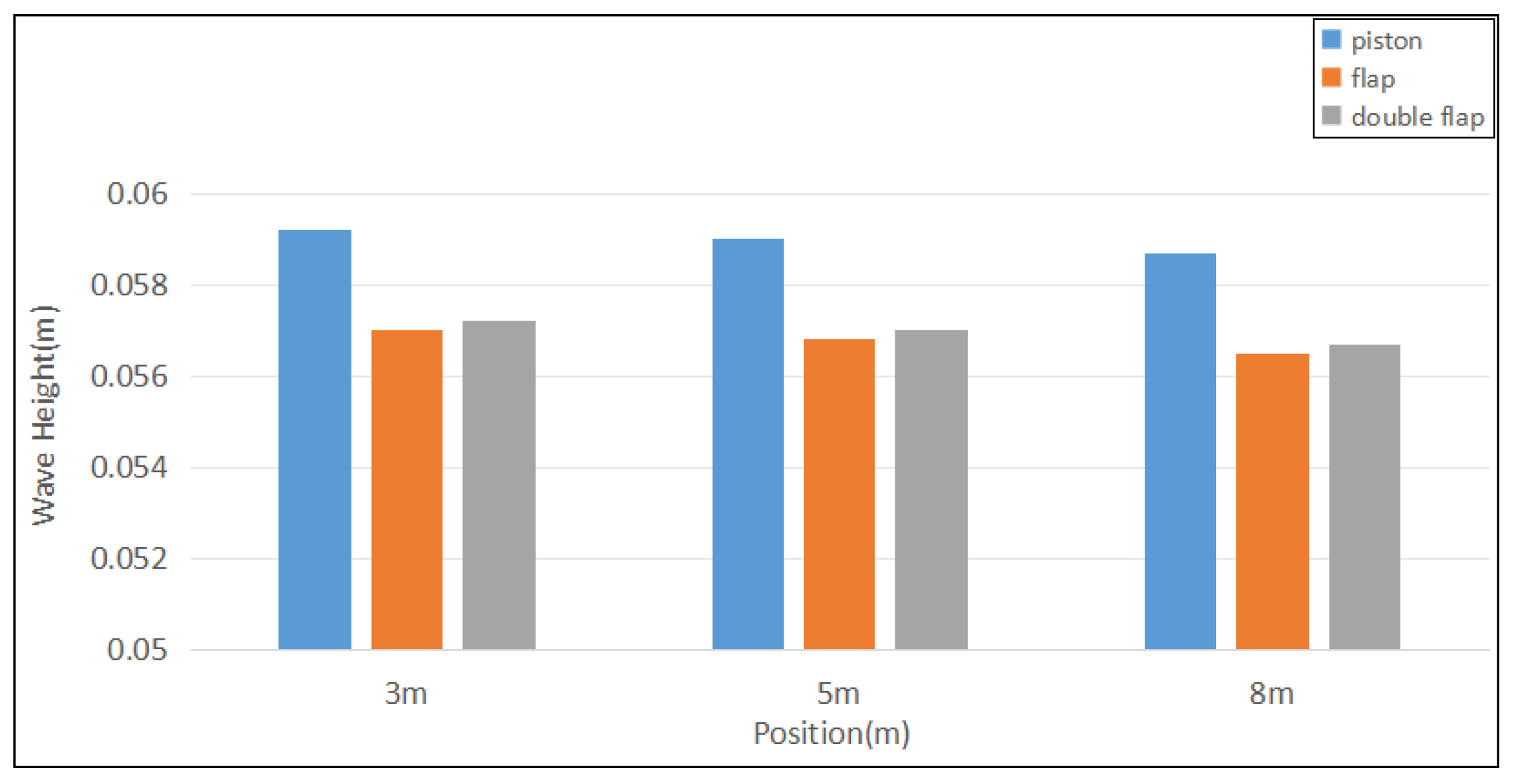

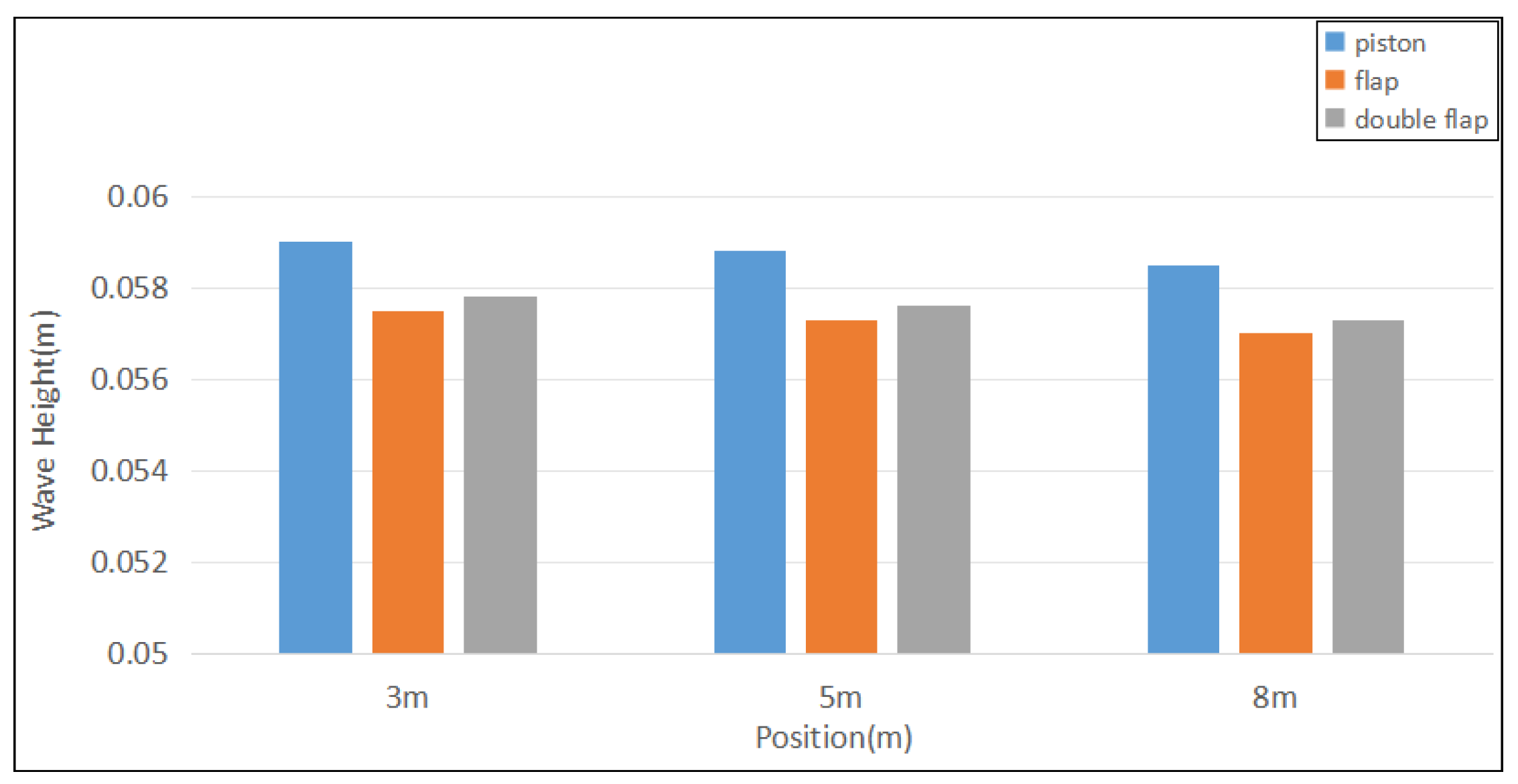

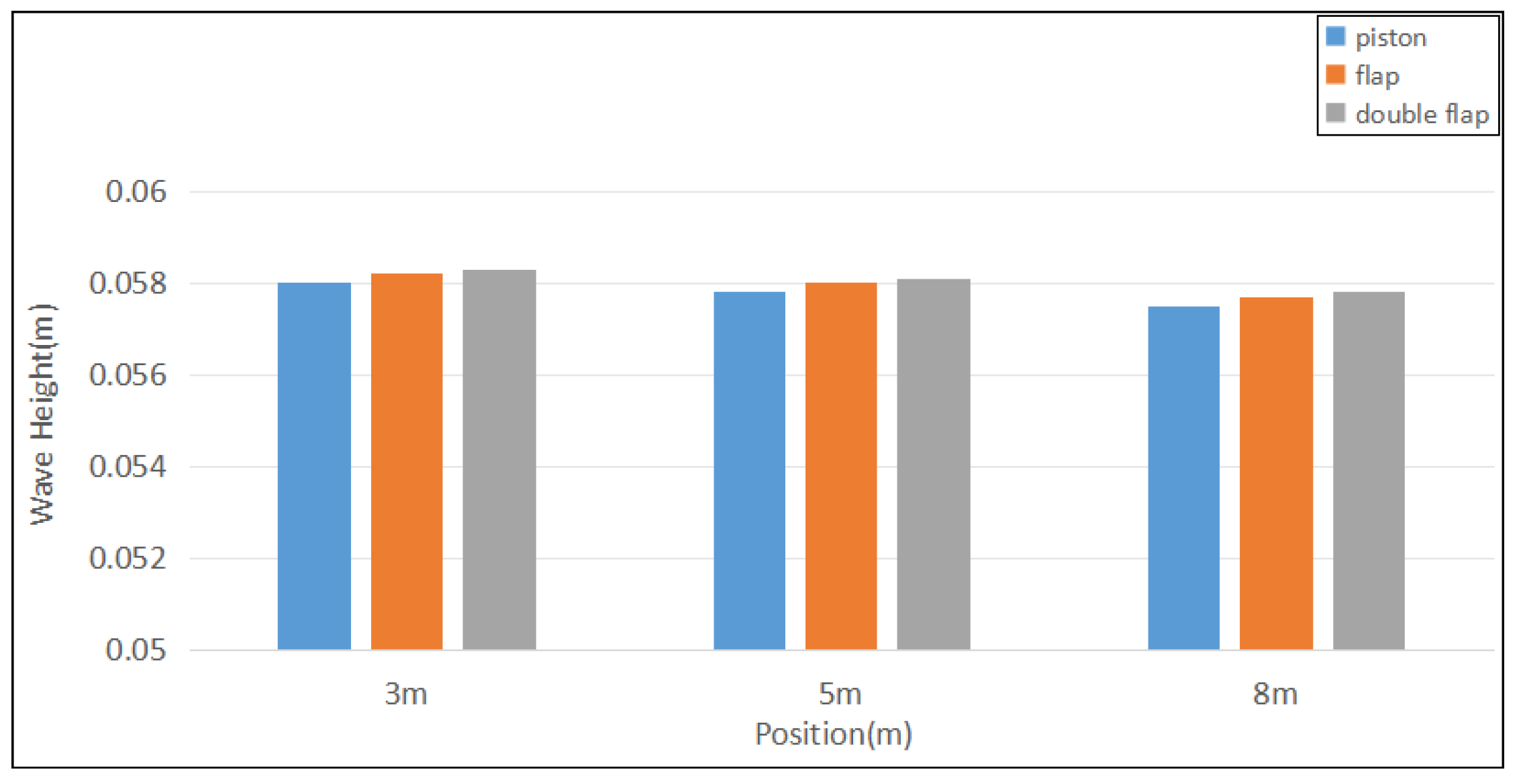

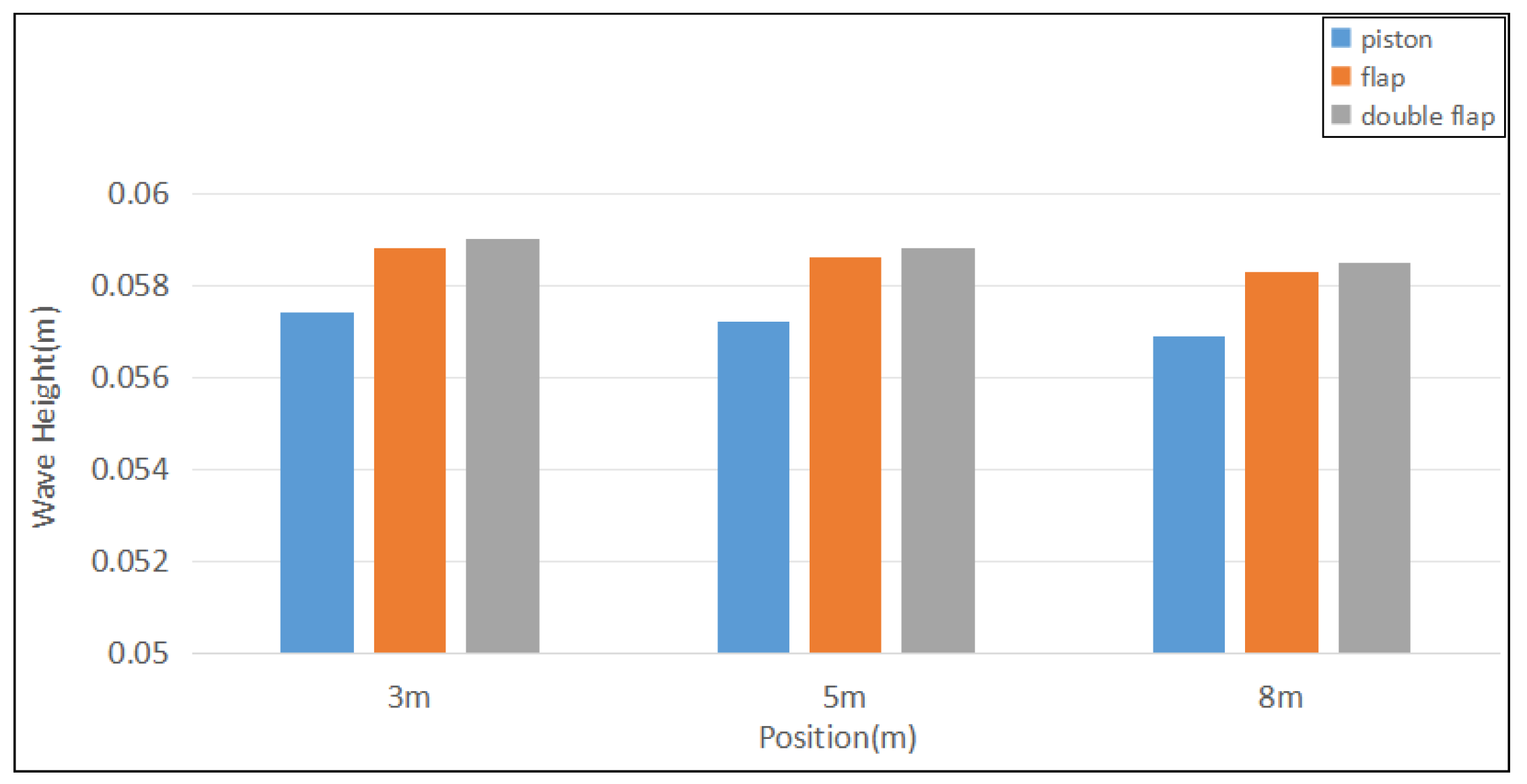

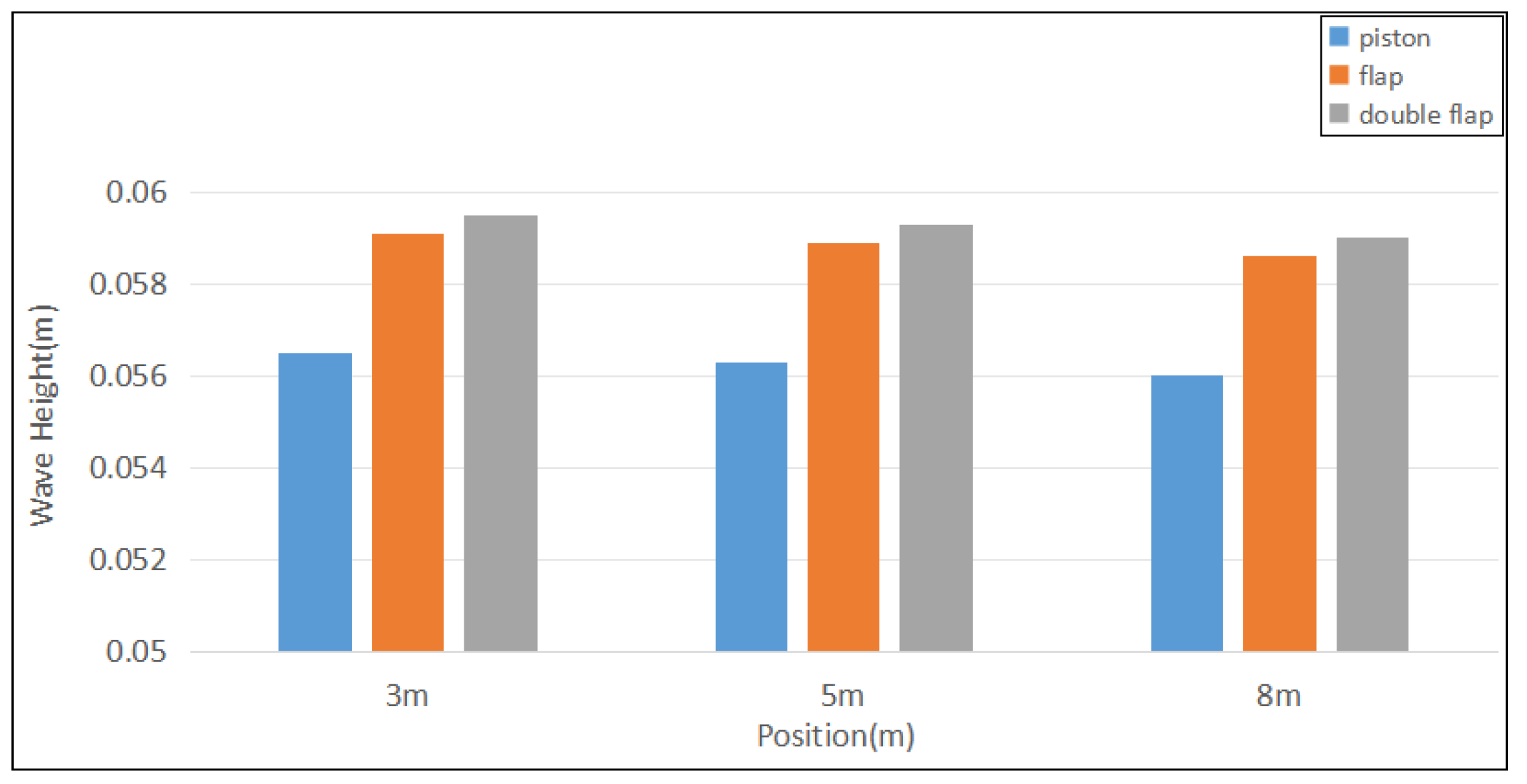

3.6. Comparison of Piston-Type, Flap-Type and Double Flap-Type Wave Makers

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dean, R.G.; Dalrymple, R.A. Water Wave Mechanics for Engineers and Scientists; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Blenkinsopp, C.E.; Chaplin, J.R. The effect of relative crest submergence on wave breaking over submerged slopes. Coast. Eng. 2008, 55, 967–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Oh, J.; Lew, J.-M.; Rhee, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Wave and wave board motion of hybrid wave maker. J. Soc. Nav. Archit. Korea 2021, 58, 339–347. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, J.; Oh, J.; Kim, H.; Lew, J.-M. Linear analysis of water surface waves generated by submerged wave board whose upper and lower ends oscillate horizontally freely. J. Soc. Nav. Archit. Korea 2019, 56, 418–426. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.; Kwon, J.; Lew, J.-M. Approximate solution of vertical wave board oscillating in submerged condition and its design application. J. Soc. Nav. Archit. Korea 2018, 55, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, P.C.; Hai, N.L.D. A study on design and fabrication of a wave maker in laboratory environment. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Scientific Conference on Applying New Technology in Green Buildings (ATiGB), Danang, Vietnam, 10–11 November 2023; ISBN 979-8-3503-4397. [Google Scholar]

- Fouques, S.; Laflèche, S.; Akselsen, A.; Sauder, T. An experimental investigation of nonlinear wave generation by flap wavemakers. In International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Proceedings of the ASME 2021 40th, Virtual Conference, 21–30 June 2021; The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): Houston, TX, USA, 2021; Paper No. OMAE2021-63120. [Google Scholar]

- Shehab, A.; El-Baz, A.M.R.; Elmarhomy, A.M. CFD modeling of regular and irregular waves generated by flap-type wave maker. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2021, 85, 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, A.; Elangovan, M. CFD simulation and validation of flap-type wave-maker. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2008, 2, 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nouioui, B.; Doğan, M. Irregular wavemaker (piston type) in a numerical and physical wave tank. Usak Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2022, 52, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krvavica, N.; Ružić, I.; Ožanić, N. New approach to flap-type wavemaker equation with wave breaking limit. Coast. Eng. J. 2018, 60, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawinahyu, W.M.; Karjanto, N.; Klopman, G. Linear theory for single and double flap wavemakers. J. Indones. Math. Soc. 2006, 12, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Marques Machado Fábio, M.; Gameiro Lopes António, M.; Ferreira, A.D. Numerical simulation of regular waves: Optimization of a numerical wave tank. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 170, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Folley, M.; Whittaker, T.J.T.; Henry, A. The effect of water depth on the performance of a small surging wave energy converter. Ocean. Eng. 2007, 34, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, G.; Deng, W.; Gao, Z. Numerical and Experimental Studies on a Three-Dimensional Numerical Wave Tank; IEEE Access: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 6, p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Analysis of overtopping wave energy converters with ramp angle variations using particle-based simulation. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 48, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H. Effects of wave generation distance in particle-based numerical wave tank on the analysis of overtopping wave energy converters. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2024, 48, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanzadeh, S.; Ozbulut, M.; Yildiz, M. Simulation of irregular wave motion using a flap-type wavemaker. In Proceedings of the VIII. International Conference on Computational Methods in Marine Engineering (MARINE 2019), Gothenburg, Sweden, 13–15 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan, M.; Lal, A. Simulation and validation of plunger type wave maker by CFD. ResearchGate. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290952269 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Li, M. Wave generation by flap-type wavemaker in circular arc numerical wave tanks. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 170, 022021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Song, R.; Chen, J.; Jin, H. Wave generation characteristic analysis of piston and flap-type wave maker with rotary-valve-control vibrator. J. Vib. Control 2022, 26, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Cho, D.; Jang, T. A numerical experiment on a new piston-type wavemaker: Shallow water approximation. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2023, 15, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.M.; Park, J.C.; Jeon, G.-M.; Chun, H.-H. Numerical simulation of wave and curent interaction with a fixed offshore substructure. Int. J. Nav. Archit. Ocean Eng. 2016, 8, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.M. Theory for Articulated Double-Flap Wavemakers in Water of Constant Depth. J. Soc. Nav. Archit. Jpn. 1977, 141, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.A. Physical Models and Laboratory Techniques in Coastal Engineering; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 1993; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, O. Waves generated by a piston-type wavemaker. Coast. Eng. 1970, 1, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, R.I. Solution of the implicitly discretised fluid flow equations by operator-splitting. J. Comput. Phys. 1986, 62, 40–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferziger, J.H.; Perić, M. Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Case | Cells per Wave Height | Number of Grid Cells (Million) | Grid Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 5 | 0.05 | Very fine |

| G2 | 10 | 0.15 | Fine |

| G3 | 20 | 0.55 | Medium |

| G4 | 40 | 0.98 | Coarse |

| Case | Time Steps per Wave Period | Courant Number |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 400 | 0.95 |

| T2 | 600 | 0.50 |

| T3 | 800 | 0.10 |

| T4 | 1000 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, K.; Dou, H.; Oh, J.; Seo, D. Numerical Comparison of Piston-, Flap-, and Double-Flap-Type Wave Makers in a Numerical Wave Tank. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122273

Yan K, Dou H, Oh J, Seo D. Numerical Comparison of Piston-, Flap-, and Double-Flap-Type Wave Makers in a Numerical Wave Tank. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122273

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Kaicheng, Haoyu Dou, Jungkeun Oh, and Daewon Seo. 2025. "Numerical Comparison of Piston-, Flap-, and Double-Flap-Type Wave Makers in a Numerical Wave Tank" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122273

APA StyleYan, K., Dou, H., Oh, J., & Seo, D. (2025). Numerical Comparison of Piston-, Flap-, and Double-Flap-Type Wave Makers in a Numerical Wave Tank. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122273