Temporal Dynamics and Recovery Patterns of Reef Benthic Communities in the Maldives Following a Mass Global Bleaching Event

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

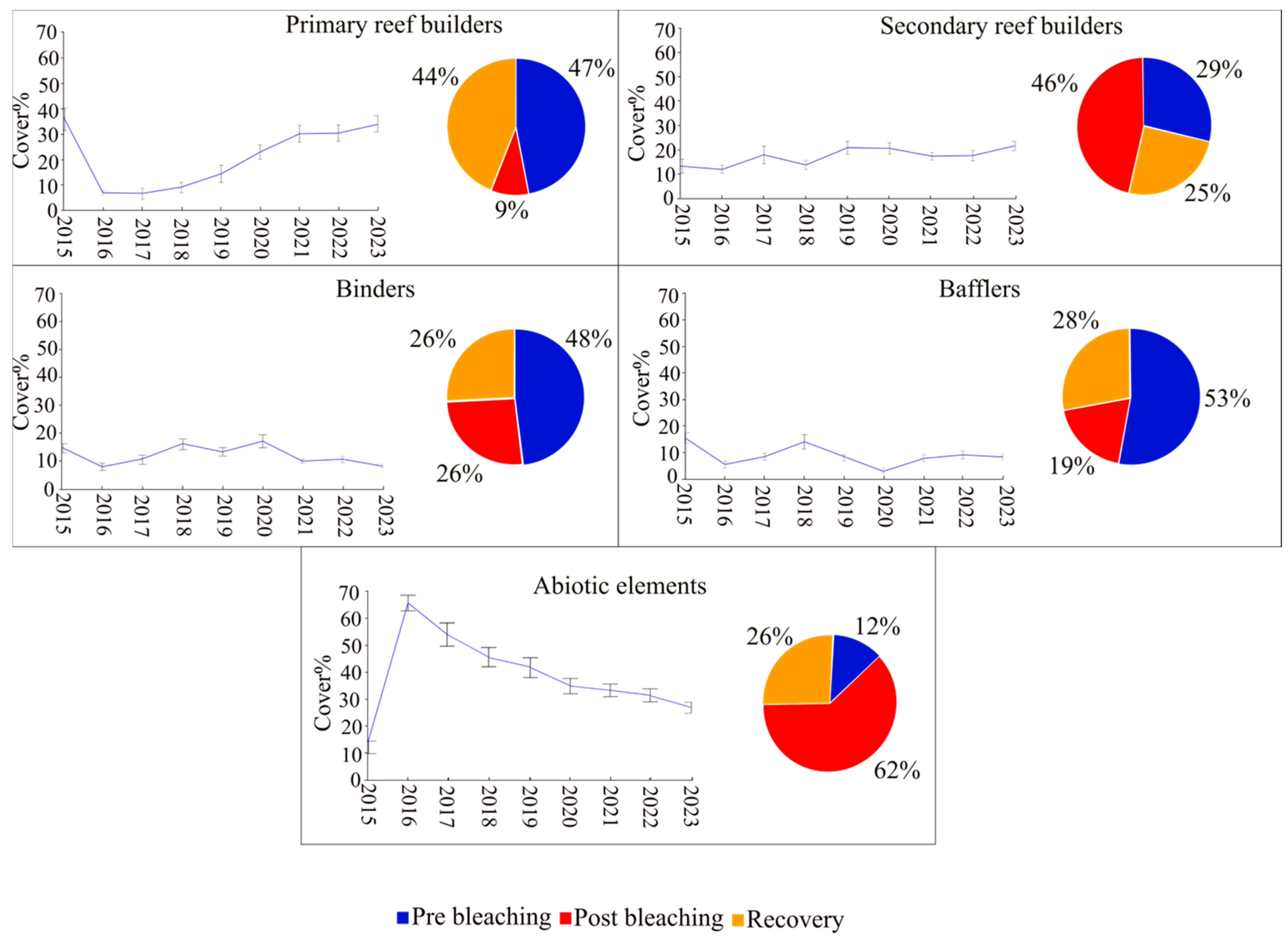

- (1)

- Primary reef builders (P): these organisms directly form the reef’s structural framework by secreting calcium carbonate. Corals such as Acropora species (with branching, digitate, and tabular morphologies), Tubastraea, Heliopora (blue coral), and Millepora (fire coral, class Hydrozoa), are major contributors, building the complex three-dimensional architecture essential for reef ecosystems [9,35].

- (2)

- Secondary reef builders (S): although not forming the primary structure, these organisms enhance reef stability and complexity. They include foliose corals and members of the Fungiidae family (solitary corals with distinctive, disc-like shapes), as well as bivalves like Tridacna, whose calcareous shells contribute to habitat formation and material accumulation [9,35].

- (3)

- Binders (Bi): these organisms stabilize and consolidate the reef by cementing sediments and debris. Key binders include encrusting corals and coralline algae, which secrete calcareous substances that act as natural cement. While binders do not create the foundational framework, they are indispensable in maintaining the structural integrity and resilience of the reef ecosystem [9,35].

- (4)

- Bafflers (Ba): by reducing the strength of water currents and promoting sediment deposition, bafflers create suitable conditions for the settlement and growth of other reef-building organisms. Representative taxa include Corallimorpharia, genus Palythoa, soft corals (both zooxanthellate and azooxanthellate), fleshy algae, sponges, Tunicata, fan and feather corals, and whip and wire corals. Their role in modulating hydrodynamics enhances reef resilience and biodiversity [9,35].

- (5)

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burke, L.; Reytar, K. Reefs at Risk Revisited: Technical Notes on Modeling Threats to the World’s Coral Reefs; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world’s coral reefs. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1999, 50, 839–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moberg, F.; Folke, C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, F.M.; Benkwitt, C.E.; Peralta, G.; Robinson, J.P.W.; Graham, N.A.J.; Tylianakis, J.M.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A.C.; Ferreira, J.; Louzada, J.; et al. Climatic and local stressor interactions threaten tropical forests and coral reefs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.J.; Alexander, L.V.; Perkins, S.E.; Smale, D.A.; Straub, S.C.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Burrows, M.T.; Donat, M.G.; Feng, M.; et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 2016, 141, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, E.C.J.; Donat, M.G.; Burrows, M.T.; Moore, P.J.; Smale, D.A.; Alexander, L.V.; Benthuysen, J.A.; Feng, M.; Gupta, A.S.; Hobday, A.J.; et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trenberth, K.E. The Definition of El Niño. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1997, 78, 2771–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claar, D.C.; Szostek, L.; McDevitt-Irwin, J.M.; Schanze, J.J.; Baum, J.K. Global patterns and impacts of El Niño events on coral reefs: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefalcone, M.; Morri, C.; Bianchi, C.N. Long-term change in bioconstruction potential of Maldivian coral reefs following extreme climate anomalies. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 5629–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roff, G.; Bejarano, S.; Bozec, Y.M.; Nugues, M.; Steneck, R.S.; Mumby, P.J. Porites and the Phoenix effect: Unprecedented recovery after a mass coral bleaching event at Rangiroa Atoll, French Polynesia. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 1385–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgen-Urcelay, A.; Donner, S.D. Increase in the extent of mass coral bleaching over the past half-century, based on an updated global database. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, J.D.; Peixoto, R.S.; Davies, S.W.; Traylor-Knowles, N.; Short, M.L.; Cabral-Tena, R.A.; Burt, J.A.; Pessoa, I.; Banaszak, A.T.; Winters, R.S.; et al. The Fourth Global Coral Bleaching Event: Where do we go from here? Coral Reefs 2024, 43, 1121–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, H.C.; Cohen, A.L. Skeletal records of community-level bleaching in Porites corals from Palau. Coral Reefs 2016, 35, 1407–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Alcoverro, T.; Gómez, C.; Kelkar, N.; Pagès, J.F.; Pinto, W.; Yadav, S.; Karkarey, R.; Gangal, M.; Ibrahim, M.K.; et al. Local Environmental Filtering and Frequency of Marine Heatwaves Influence Decadal Trends in Coral Composition. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e70043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.; Harris, A.; Sheppard, A. Archipelago-wide coral recovery patterns since 1998 in the Chagos Archipelago, central Indian Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 362, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montefalcone, M.; Morri, C.; Bianchi, C.N. Influence of Local Pressures on Maldivian Coral Reef Resilience Following Repeated Bleaching Events, and Recovery Perspectives. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, C.; Montefalcone, M.; Lasagna, R.; Gatti, G.; Rovere, A.; Parravicini, V.; Baldelli, G.; Colantoni, P.; Bianchi, C.N. Through bleaching and tsunami: Coral reef recovery in the Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 98, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donati, M.; Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Montefalcone, M. Idiosyncratic recovery patterns in coral reefs of the Maldives following climate disturbance. Mar. Ecol. 2025, 46, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C.; Lasagna, R.; Montefalcone, M.; Gatti, G.; Parravicini, V.; Rovere, A. Resilience of the Marine Animal Forest: Lessons from Maldivian Coral Reefs After the Mass Mortality of 1998. In Marine Animal Forests; Rossi, S., Bramanti, L., Gori, A., Orejas, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1241–1269. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-21012-4_35 (accessed on 26 January 2025).

- Fagerstrom, J.A. Reef-building guilds and a checklist for determining guild membership. Coral Reefs 1991, 10, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocito, S. Bioconstruction and biodiversity: Their mutual influence. Sci. Mar. 2004, 68 (Suppl. S1), 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.A. Morphological plasticity in scleractinian corals. Biol. Rev. 2008, 83, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Garin, B.; Montaggioni, L.F. Into the Intimacy of Corals, Builders of the Sea. In Corals and Reefs: From the Beginning to an Uncertain Future; Martin-Garin, B., Montaggioni, L.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.H. On the Prevalence and Relative Importance of Interspecific Competition: Evidence from Field Experiments. Am. Nat. 1983, 122, 661–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, A.K.; Thomson, D.P.; Haywood, M.D.E.; Renton, M. Frequent hydrodynamic disturbances decrease the morphological diversity and structural complexity of 3D simulated coral communities. Coral Reefs 2020, 39, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Done, T.J. Ecological criteria for evaluating coral reefs and their implications for managers and researchers. Coral Reefs 1995, 14, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, S.A. Differential thermal bleaching susceptibilities amongst coral taxa: Re-posing the role of the host. Coral Reefs 2014, 33, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Yu, K.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Huang, X.; Chen, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Pan, Z. Spatial and Intergeneric Variation in Physiological Indicators of Corals in the South China Sea: Insights Into Their Current State and Their Adaptability to Environmental Stress. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 3317–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawada, K.J.A.; Madin, J.S.; Baird, A.H.; Bridge, T.C.L.; Dornelas, M. Morphological traits can track coral reef responses to the Anthropocene. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 962–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.D.; Nelson, C.E.; Oliver, T.A.; Quinlan, Z.A.; Remple, K.; Glanz, J.; Smith, J.E.; Putnam, H.M. Differential resistance and acclimation of two coral species to chronic nutrient enrichment reflect life-history traits. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, A. Pre-and post-tsunami coastal planning and land-use policies and issues in the Maldives. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Coastal Area Planning and Management in Asian Tsunami-Affected Countries, Bangkok, Thailand, 27–29 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikheyan, T.C. Environmental Challenges for Maldives. South Asian Surv. 2010, 17, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Coral Bleaching Report—CORDIOEA. 2024. Available online: https://cordioea.net/2024-wio-bleaching-report/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Wilson, S.K.; Graham, N.A.J.; Polunin, N.V.C. Appraisal of visual assessments of habitat complexity and benthic composition on coral reefs. Mar. Biol. 2007, 151, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolfi, J.M.; Bradbury, R.H.; Sala, E.; Hughes, T.P.; Bjorndal, K.A.; Cooke, R.G.; McArdle, D.; McClenachan, L.; Newman, M.J.H.; Paredes, G.; et al. Global Trajectories of the Long-Term Decline of Coral Reef Ecosystems. Science 2003, 301, 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Kerry, J.T.; Baird, A.H.; Connolly, S.R.; Dietzel, A.; Eakin, C.M.; Heron, S.F.; Hoey, A.S.; Hoogenboom, M.O.; Liu, G.; et al. Global warming transforms coral reef assemblages. Nature 2018, 556, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, A.C.; Glynn, P.W.; Riegl, B. Climate change and coral reef bleaching: An ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 80, 435–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, M.E.; Rasher, D.B. Coral reefs in crisis: Reversing the biotic death spiral. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2010, 2, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, F.; Saalmann, F.; Thomson, T.; Coker, D.; Villalobos, R.; Jones, B.; Wild, C.; Carvalho, S. Coral reef degradation affects the potential for reef recovery after disturbance. Mar. Environ. Res. 2018, 142, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obura, D.; Gudka, M.; Samoilys, M.; Osuka, K.; Mbugua, J.; Keith, D.A.; Porter, S.; Roche, R.; van Hooidonk, R.; Ahamada, S.; et al. Vulnerability to collapse of coral reef ecosystems in the Western Indian Ocean. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 5, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.C.; Wolff, N.H.; Anthony, K.R.N.; Devlin, M.; Lewis, S.; Mumby, P.J. Impaired recovery of the Great Barrier Reef under cumulative stress. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouezo, M.; Golbuu, Y.; Fabricius, K.; Olsudong, D.; Mereb, G.; Nestor, V.; Wolanski, E.; Harrison, P.; Doropoulos, C. Drivers of recovery and reassembly of coral reef communities. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 286, 20182908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, D.J.; Pratchett, M.S.; Munday, P.L. Coral bleaching and habitat degradation increase susceptibility to predation for coral-dwelling fishes. Behav. Ecol. 2009, 20, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, K.S. The northernmost coral frontier of the Maldives: The coral reefs of Ihavandippolu Atoll under long-term environmental change. Mar. Environ. Res. 2012, 82, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, K.S. Impact of repetitive Thermal anomalies on survival and development of mass reef-building corals in the Maldives. Mar. Ecol. 2015, 36, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancrazi, I.; Ahmed, H.; Chimienti, G.; Montefalcone, M. The new face of the northernmost coral reefs of the Maldives revisited after 13 years. Coral Reefs 2025, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.P.W.; Wilson, S.K.; Graham, N.A.J. Abiotic and biotic controls on coral recovery 16 years after mass bleaching. Coral Reefs 2019, 38, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, K.A.; Osborne, K.O.; Logan, M. Contrasting rates of coral recovery and reassembly in coral communities on the Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs 2014, 33, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisapia, C.; Burn, D.; Yoosuf, R.; Najeeb, A.; Anderson, K.D.; Pratchett, M.S. Coral recovery in the central Maldives archipelago since the last major mass-bleaching, in 1998. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, J.; University of New South Wales. Soft Corals More Resilient than Reef-Building Corals During a Marine Heatwave. 2022. Available online: https://phys.org/news/2022-06-soft-corals-resilient-reef-building-marine.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Marshall, P.A.; Baird, A.H. Bleaching of corals on the Great Barrier Reef: Differential susceptibilities among taxa. Coral Reefs 2000, 19, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, C.E.; Carlot, J.; Branson, O.; Courtney, T.A.; Harvey, B.P.; Perry, C.T.; Andersson, A.J.; Diaz-Pulido, G.; Johnson, M.D.; Kennedy, E.; et al. Crustose coralline algae can contribute more than corals to coral reef carbonate production. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Pulido, G.; McCook, L. The fate of bleached corals: Patterns and dynamics of algal recruitment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 232, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goatley, C.H.R. The Ecological Role of Sediments on Coral Reefs. Ph.D. Thesis, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia, 2013. Available online: http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.1.2083.5441 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Pisapia, C.; Burn, D.; Pratchett, M.S. Changes in the population and community structure of corals during recent disturbances (February 2016–October 2017) on Maldivian coral reefs. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loya, Y.; Sakai, K.; Yamazato, K.; Nakano, Y.; Sambali, H.; van Woesik, R. Coral bleaching: The winners and the losers. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, A.C.; Kiessling, W.; Bellwood, D.R. Fast-growing species shape the evolution of reef corals. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norzagaray-López, C.O.; Calderon-Aguilera, L.E.; Hernández-Ayón, J.M.; Reyes-Bonilla, H.; Carricart-Ganivet, J.P.; Cabral-Tena, R.A.; Balart, E.F. Low calcification rates and calcium carbonate production in Porites panamensis at its northernmost geographic distribution. Mar. Ecol. 2015, 36, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Noriega, M.; Baird, A.H.; Dornelas, M.; Madin, J.S.; Connolly, S.R. Negligible effect of competition on coral colony growth. Ecology 2018, 99, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

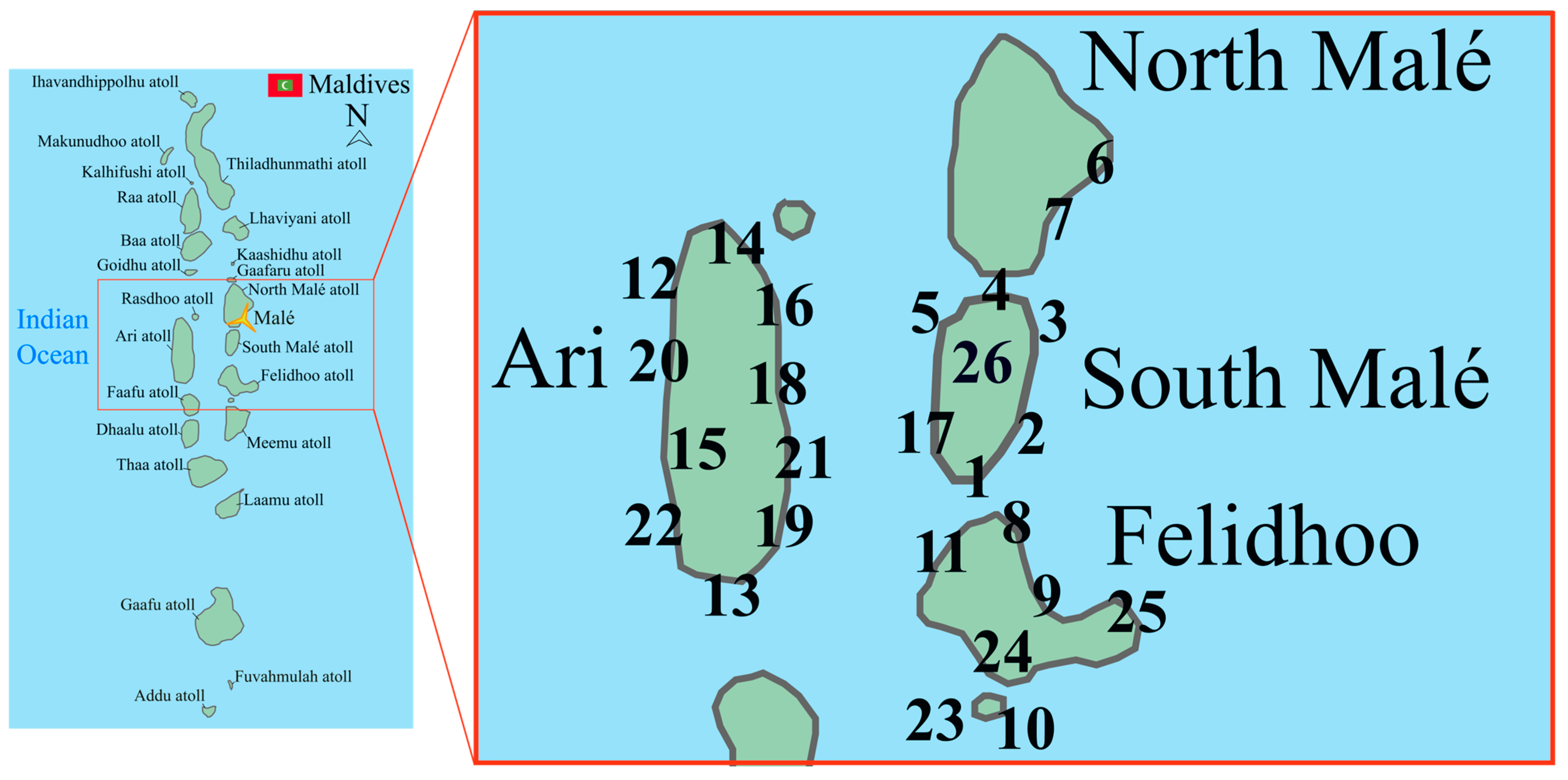

| Atoll | Site Name | Site Code | Latitude | Longitude | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Malé | Maadhoo Beyru | 1 | 3°52.959′ N | 73°28.085′ E | 2015 2016 2017 |

| South Malé | Villivaru Kuda Giri | 2 | 3°54.234′ N | 73°26.663′ E | 2015 2016 2017 |

| South Malé | Myharu Faru | 3 | 3°59.573′ N | 73°31.479′ E | 2015 |

| South Malé | Cocoa Beyru | 4 | 3°54.731′ N | 73°29.116′ E | 2015 2016 2017 |

| South Malé | Kuda Finolhu | 5 | 3°59.931′ N | 73°23.613′ E | 2015 |

| North Malé | Hulhumale Beyru | 6 | 4°14.238′ N | 73°33.322′ E | 2015 2016 2017 |

| North Malé | Kuda Khali | 7 | 4°14.032′ N | 73°31.945′ E | 2015 2016 2017 |

| Felidhoo | Miyaru Kandu | 8 | 3°35.868′ N | 73°30.241′ E | 2015 2023 |

| Felidhoo | Devana Kandu | 9 | 3°34.959′ N | 73°30.325′ E | 2015 |

| Felidhoo | Vattaru Beyru East | 10 | 3°13.188′ N | 73°25.639′ E | 2015 2023 |

| Felidhoo | Fushi Falhu Etere | 11 | 3°39.853′ N | 73°24.373′ E | 2015 |

| Ari | Viligilee Falhu | 12 | 3°59.947′ N | 72°47.140′ E | 2016 |

| Ari | Dhigurah Beyru | 13 | 3°31.923′ N | 72°55.801′ E | 2016 2023 |

| Ari | Ellahidoo | 14 | 4°01.663′ N | 72°57.561′ E | 2016 |

| Ari | Toshiganduhau | 15 | 3°43.400′ N | 72°48.124′ E | 2016 2023 |

| Ari | Fishi Faru Beyru | 16 | 3°56.817′ N | 72°57.472′ E | 2016 2023 |

| South Malé | Vaagali Faru | 17 | 3°54.660′ N | 73°22.631′ E | 2016 |

| Ari | Faanu Mudugau Beyru | 18 | 3°55.527′ N | 72°57.478′ E | 2023 |

| Ari | Dhangethi House Reef | 19 | 3°36.172′ N | 72°56.102′ E | 2023 |

| Ari | Emboodhoo House Reef | 20 | 3°48.819′ N | 72°45.135′ E | 2023 |

| Ari | Maafaru falhu | 21 | 3°42.332′ N | 72°58.178′ E | 2023 |

| Ari | Rehi reef | 22 | 3°43.754′ N | 72°45.550′ E | 2023 |

| Felidhoo | Vattaru Etere | 23 | 3°13.477′ N | 73°25.203′ E | 2023 |

| Felidhoo | Rakeedhoo Beyru | 24 | 3°18.702′ N | 73°27.931′ E | 2023 |

| Felidhoo | Fotteyo Beyru | 25 | 3°30.313′ N | 73°44.569′ E | 2023 |

| South Malé | Sexy Finolhu | 26 | 3°57.318′ N | 73°27.500′ E | 2023 |

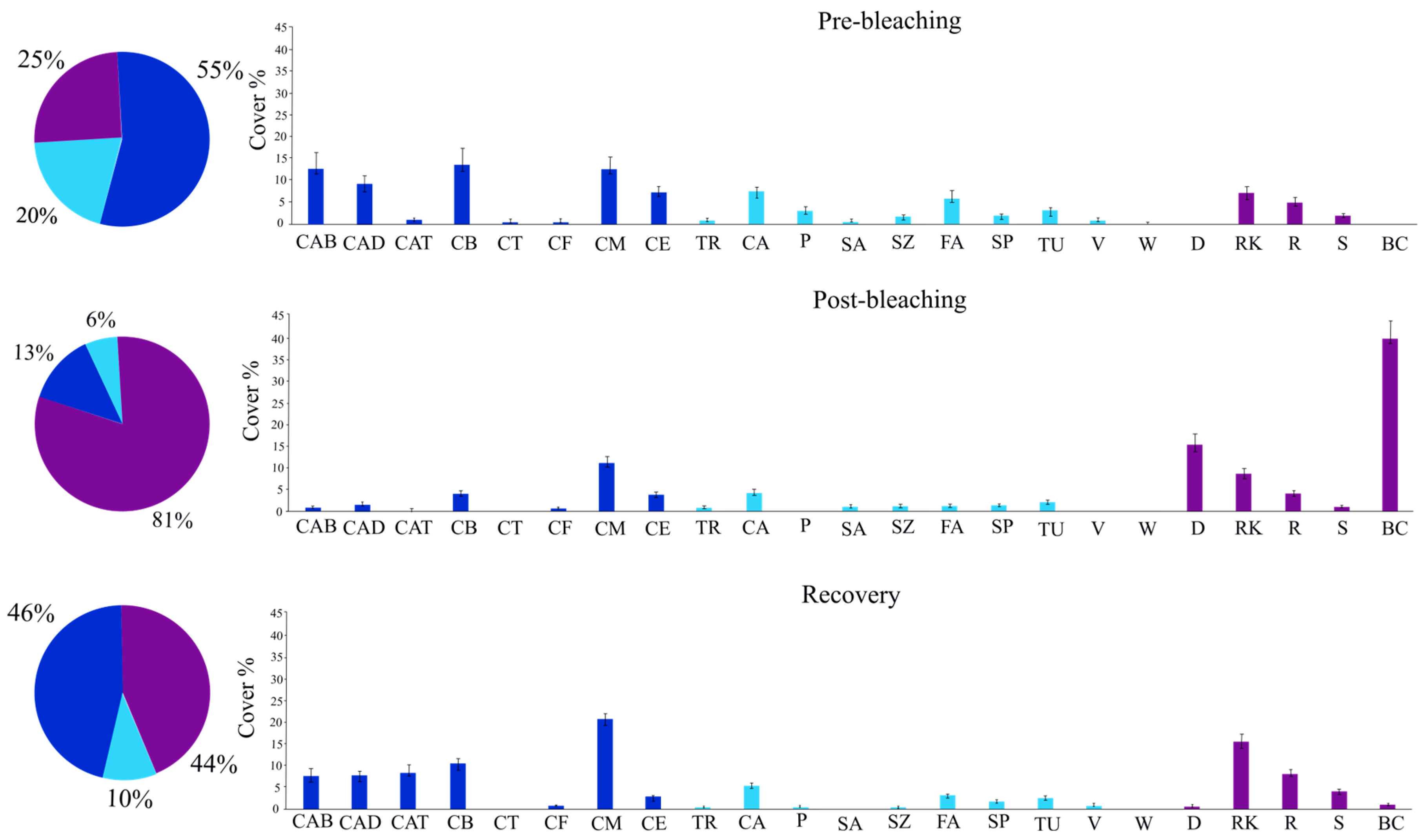

| Category | Code | Bioconstructional Guild | Descriptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| HC | CAB | P | Coral Acropora branching |

| HC | CAD | P | Coral Acropora digitate |

| HC | CAT | P | Coral Acropora tabular |

| HC | CB | P | Coral branching |

| HC | H | P | Heliopora |

| HC | M | P | Millepora |

| HC | CM | P | Coral massive |

| HC | CT | P | Coral Tubastrea |

| HC | CF | S | Coral foliose/Fungidae |

| HC | CE | Bi | Coral encrusting |

| Oth | TR | S | Other clams |

| Oth | CA | Bi | Coralline algae |

| Oth | CMR | Ba | Others Corallimorpharians |

| Oth | P | Ba | Others Palythoa |

| Oth | SA | Ba | Soft corals azooxanthellates |

| Oth | SZ | Ba | Soft corals zooxanthellates |

| Oth | FA | Ba | Flashy algae |

| Oth | SP | Ba | Sponges |

| Oth | TU | Ba | Other tunicates |

| Oth | V | Ba | Others fan and feather corals |

| Oth | W | Ba | Others whip and wire corals |

| Abt | D | A | Dead coral |

| Abt | RK | A | Coral rock |

| Abt | R | A | Coral rubble |

| Abt | S | A | Sand |

| Abt | BC | A | Bleached corals |

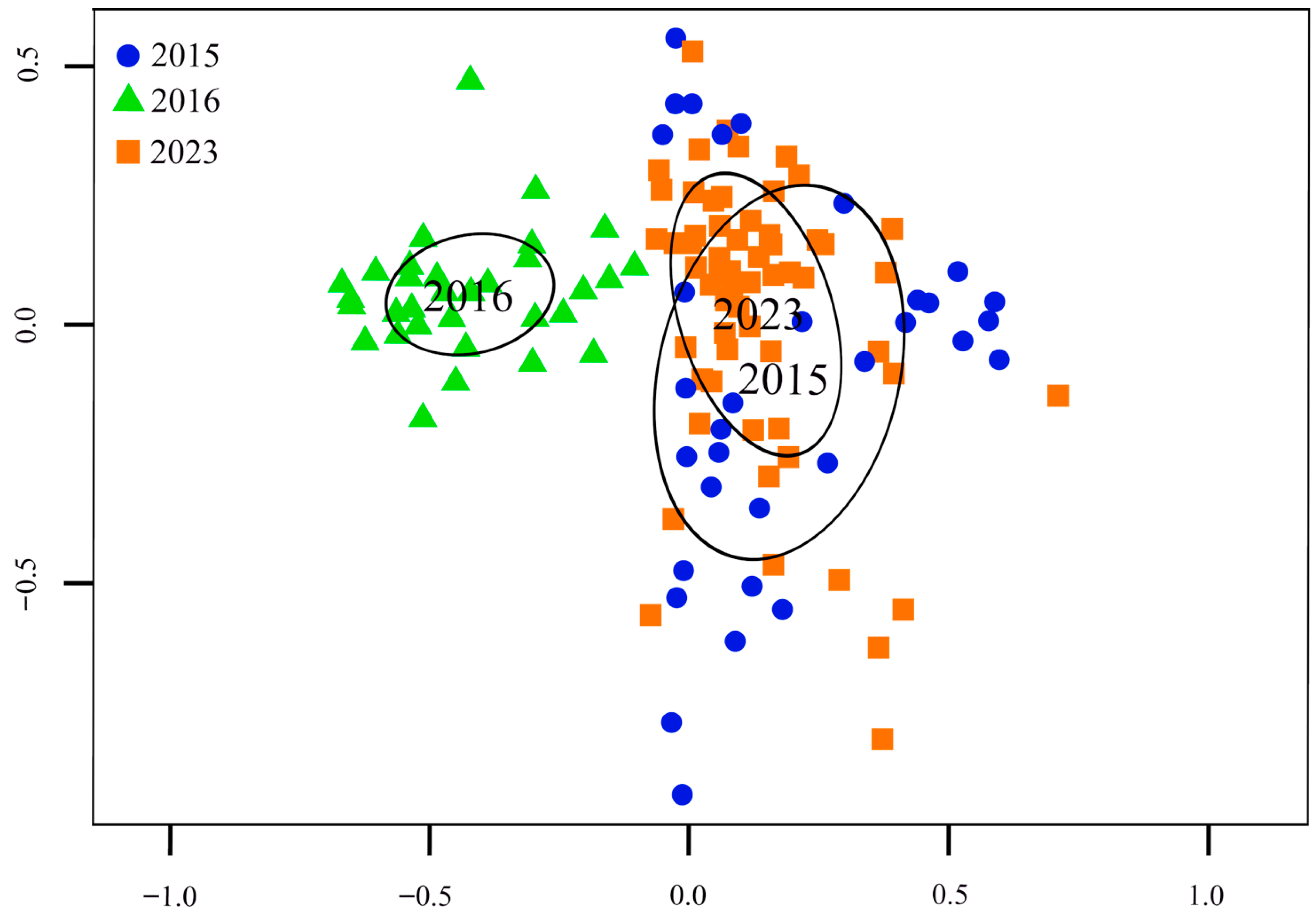

| Statistic | Hard Corals | Branching | Digitate | Massive | Encrusting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | 21.0593 | 16.8301 | 15.4339 | 7.3442 | 7.9677 |

| Degrees of freedom (Between) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Degrees of freedom (Within) | 613.99 | 112.82 | 60.33 | 65.89 | 55.02 |

| p-value * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00132 | 0.00091 |

| Effect size | 0.19 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.41 | 0.46 |

| Bootstrap CI (Effect size) | [0.13; 0.24] | [0.22; 0.45] | [0.32; 0.73] | [0.21; 0.69] | [0.23; 0.65] |

| Post hoc * | 2015 > 2016 2023 > 2016 | 2015 > 2016 2023 > 2016 | 2015 > 2016 2023 > 2016 | 2015 < 2023 2016 < 2023 | 2015 > 2016 2015 > 2023 2016 > 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Germani, E.; Asnaghi, V.; Montefalcone, M. Temporal Dynamics and Recovery Patterns of Reef Benthic Communities in the Maldives Following a Mass Global Bleaching Event. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122265

Germani E, Asnaghi V, Montefalcone M. Temporal Dynamics and Recovery Patterns of Reef Benthic Communities in the Maldives Following a Mass Global Bleaching Event. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(12):2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122265

Chicago/Turabian StyleGermani, Eva, Valentina Asnaghi, and Monica Montefalcone. 2025. "Temporal Dynamics and Recovery Patterns of Reef Benthic Communities in the Maldives Following a Mass Global Bleaching Event" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 12: 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122265

APA StyleGermani, E., Asnaghi, V., & Montefalcone, M. (2025). Temporal Dynamics and Recovery Patterns of Reef Benthic Communities in the Maldives Following a Mass Global Bleaching Event. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(12), 2265. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13122265