1. Introduction

With the rapid development of industry, the depletion of fossil energy sources and the damage to the environment have become increasingly significant. According to “Net Zero Emissions 2050”, 90% of the world’s electricity will be generated from renewable energy sources by 2050 [

1,

2], including wave energy, temperature difference energy, tidal energy, salinity difference energy, etc. Among them, ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) uses the surface warm seawater (25–30 °C) and deep cold seawater (4–6 °C) to drive the thermal cycle to generate power [

3]; it is a non-polluting renewable energy with huge reserves. The ocean thermal energy reserves within 100 km of the coastline are 7.2–9.3 TW [

4], and it is estimated that the global ocean thermal energy reserves are about 4.4 × 1016 kWh/a [

5].

Because of the small temperature difference available in OTEC, its power generation efficiency is relatively low [

6], so improving cycle efficiency is a major research interest. In the cycle, the heat exchanger plays an important role in the operation of many systems, such as power plants, nuclear reactors, process industries, and heat recovery devices [

7]. Heat exchanger cost accounts for about 25% of the entire system [

8], and energy consumption accounts for 13% to 15% of industrial energy. According to the heat transfer method and principle, heat exchangers can be divided into heat storage type [

9], hybrid [

10], inter-wall [

11,

12], heat pipe [

13], rising film [

14], falling film, etc., [

15,

16].

There is a variety of methods that can be used to enhance heat transfer of shell-and-tube heat exchangers: (1) changing the shape of the surface of the heat transfer element and the treatment, such as changing the rotational direction of the deflector plate [

17]; (2) adding the insert [

18] to enhance fluid perturbation, such as the addition of a spiral deflector plate [

19,

20]; (3) adjusting the tube bundle support form to optimize the flow distribution and make full use of the heat transfer area inside the heat exchanger; (4) using the internal and external surfaces of the heat exchanger tube’s threaded surface and other forms of processing so that the heat transfer causes fluid turbulence; and (5) increasing the number of bubble cores with a porous heat exchanger to increase the boiling heat transfer coefficient, etc. [

21].

By changing the pipe type and the internal and external surface shapes of heat exchange pipes, to improve the efficiency of heat exchangers, scholars have conducted the following research: Zheng X. R. et al. [

22] conducted experiments on the heat transfer performance of a plate heat exchanger by using carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP), and the study showed that increasing the surface thermal conductivity of CFRP plates could reduce the thermal resistance of the plates and increase the heat transfer rate of the plates. In addition, Nusselt empirical correlations for CFRP plate heat exchangers were established. Professor Uehara’s team [

23] conducted the optimization of closed-cycle OTEC systems, focusing on the performance of plate heat exchangers (PHEs) and their impact on the net power output of the system. One conference paper presents research [

24] on the improvement of shell-and-tube heat exchangers proposed by Japan, aiming to combine the sturdiness of shell-and-tdesigns with the high efficiency of plate designs. Saeed et al. [

25] analyzed the plate heat exchangers through numerical and experimental methods, comparing efficiency under different operating conditions (such as flow rate and temperature). Alireza Zendehboudi [

26] designed a plate heat exchanger applied in a CO

2 heat pump system and evaluated the effect of different parameters on factors such as heat load. Chen Q. H. et al. [

27] carried out a study on the flow boiling of R134a working fluids in a plate heat exchanger and analyzed the trend of heat transfer coefficient and pressure drop of the heat exchanger when the dryness coefficient varies within the plate. Chennu Ranganayakul et al. [

28] studied the heat transfer and flow characteristics of serrated fin surfaces using inlet aspect ratio as a variable. Empirical formulas for the heat transfer factor and friction factor were established, and relevant experiments were conducted to verify their accuracy. Wang L. B. [

29] et al. used the naphthalene sublimation method to study the effects of VG parameters such as vortex fan height and angle of attack on heat transfer and pressure drop, and gave the relationship between heat transfer performance, Nussle number, and friction factor. Yin X. M. et al. [

30] illustrated the effect of the structure of the tube bundle on the flow heat transfer in a shell and tube heat exchanger. Chen B. Q. et al. [

31] investigated the heat transfer efficiency of cross-grooved tubes and light tubes in shell and tube heat exchangers, and the results showed that the heat transfer efficiency of cross-grooved tubes was 60% to 70% higher. Cui H.T. et al. [

32] studied the size, strength, structure, heat transfer phase change, convective heat transfer, thermal resistance, and other aspects of the spiral grooved tube, and proposed the fundamental theory for selecting the model of helical groove tubes according to different working conditions. Xiao G. F. et al. [

33] added spiral convoluted fins on the heat exchanger tube, Ravindra Kumar Pasupuleti et al. [

34] studied the logarithmic mean temperature difference and heat transfer efficiency of spiral-finned tubes and light tubes in shell-and-shell heat exchangers and numerically analyzed them by CFD. Yang L. et al. [

35] experimental simulation of a twisted flat tube, which cross-section is elliptical, the integrated heat transfer performance is ordinary straight elliptical tube 1.5 to 2 times and can prevent fouling accumulation. Qi H. Y. et al. [

36] pointed out that there are two trends in the overall enhancement of heat exchangers, one is to change the fin structure to improve the Reynolds number and reduce the role of the boundary layer thickness; the other is to achieve enhanced heat transfer by changing the tube bundles, such as twisted flat tube heat exchanger [

37] and staggered flat tube heat exchanger [

38].

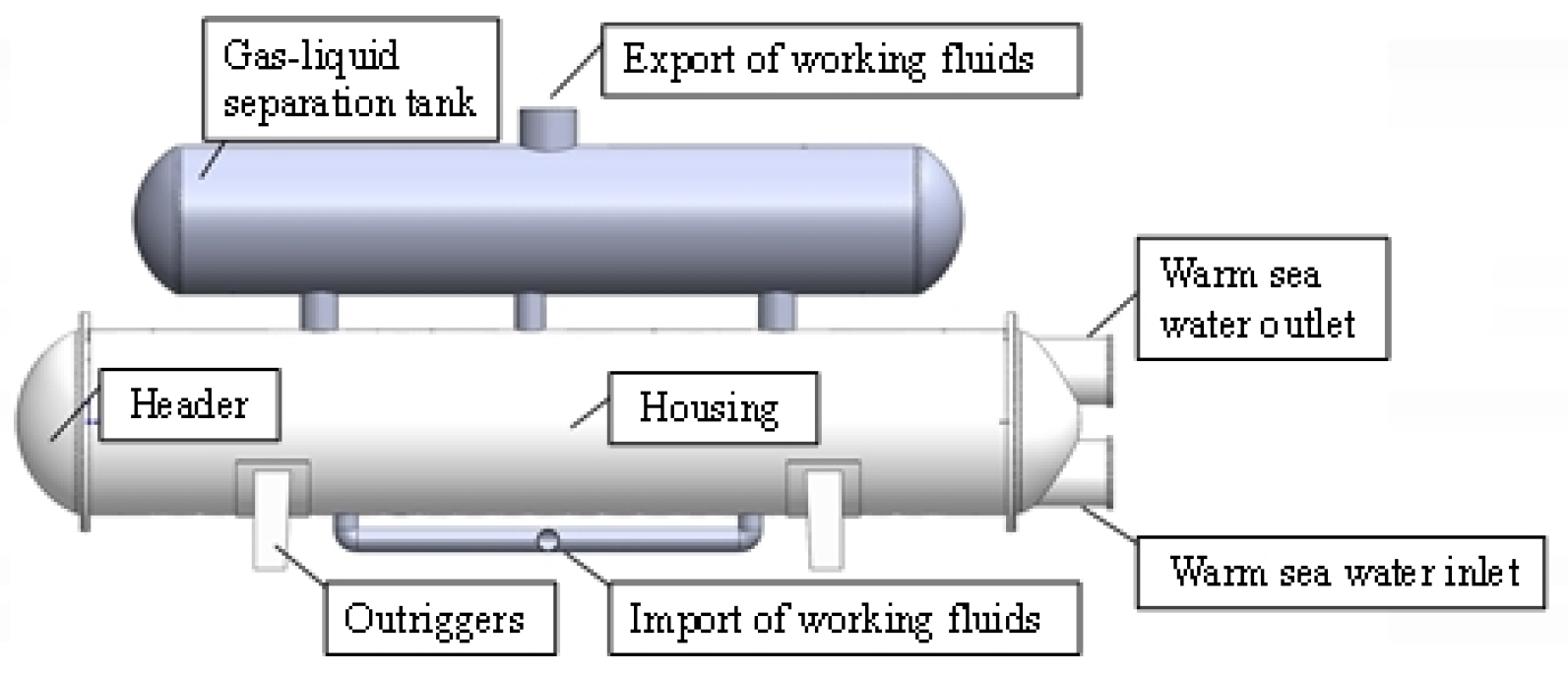

In OTEC systems, shell-and-tube heat exchangers and plate heat exchangers are mainly used. Although plate heat exchangers are superior to shell-and-tube heat exchangers in terms of compact structure and amount of metal consumed per unit of heat transfer area, shell-and-tube heat exchangers have a wide range of applicable working conditions, relatively low manufacturing cost, high operational reliability, and extensive manufacturing and processing experience. Therefore, based on practicality and cost, shell-and-tube heat exchangers are often the preferred choice in engineering. In addition, they are more suitable for environments that require long operating times and high maintenance costs, such as OTEC. Thus, we choose shell-and-tube heat exchangers as the focus of our study.

In addition, with the development of artificial intelligence, machine learning algo-rhythms combined with agent models play an important role in the design and optimization of heat exchanger tube patterns. For example, the use of genetic algorithms to assist in the design of shell and tube heat exchangers from an economic point of view [

39,

40], particle swarm algorithms [

41,

42], simulated annealing algorithms, and other stochastic search algorithms [

43,

44] have also been applied to the design of shell and tube heat exchangers. Xie G.N. et al. [

45] used artificial neural network (ANN) to analyze the heat transfer of shell and tube heat exchangers with segmented baffles and continuous spiral baffles. Lin G. T. et al. [

46] reduced the mean percentage error to 11% based on a condensation prediction method of controlling the heat transfer mechanism for flooded heat exchangers.

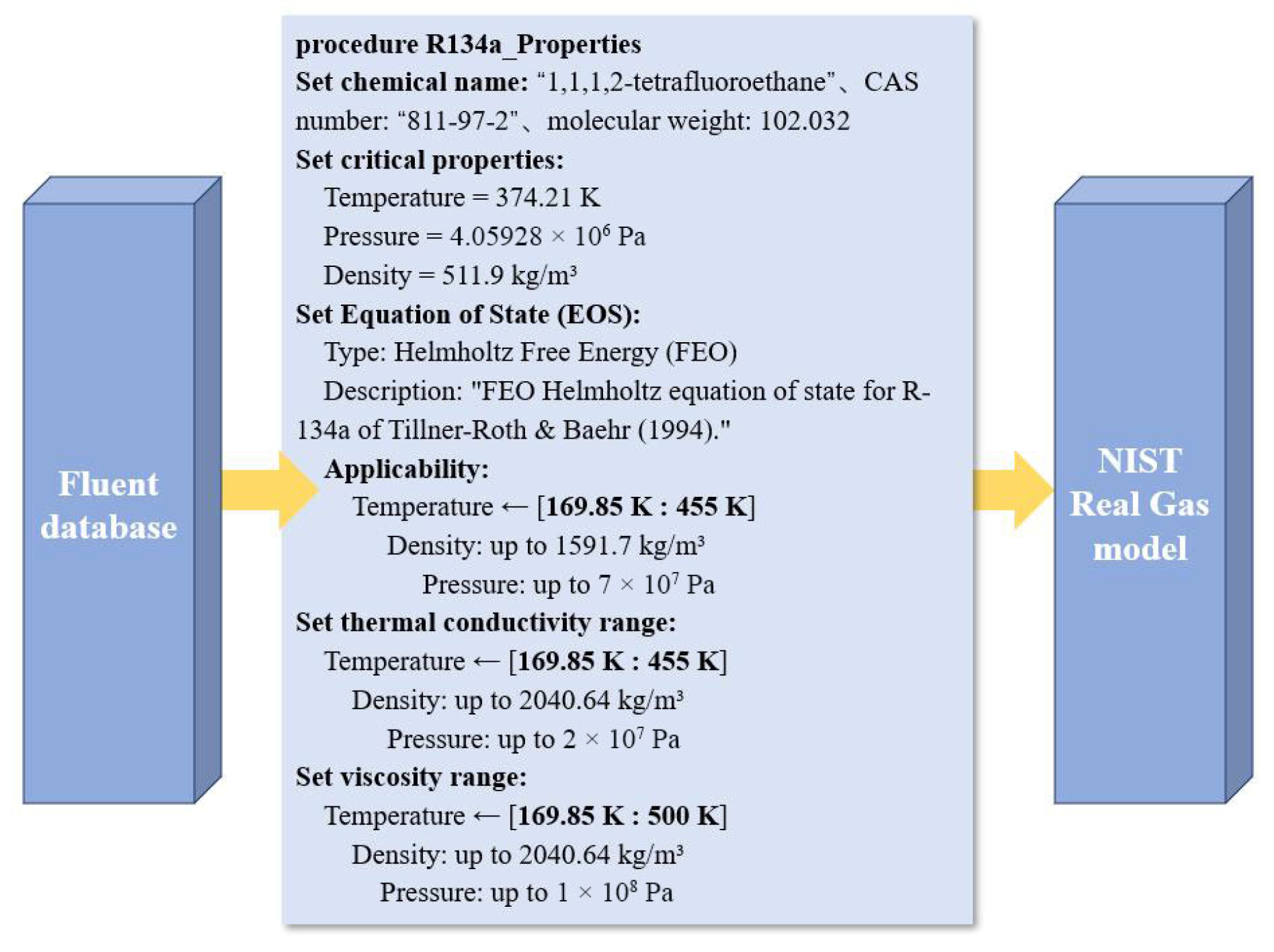

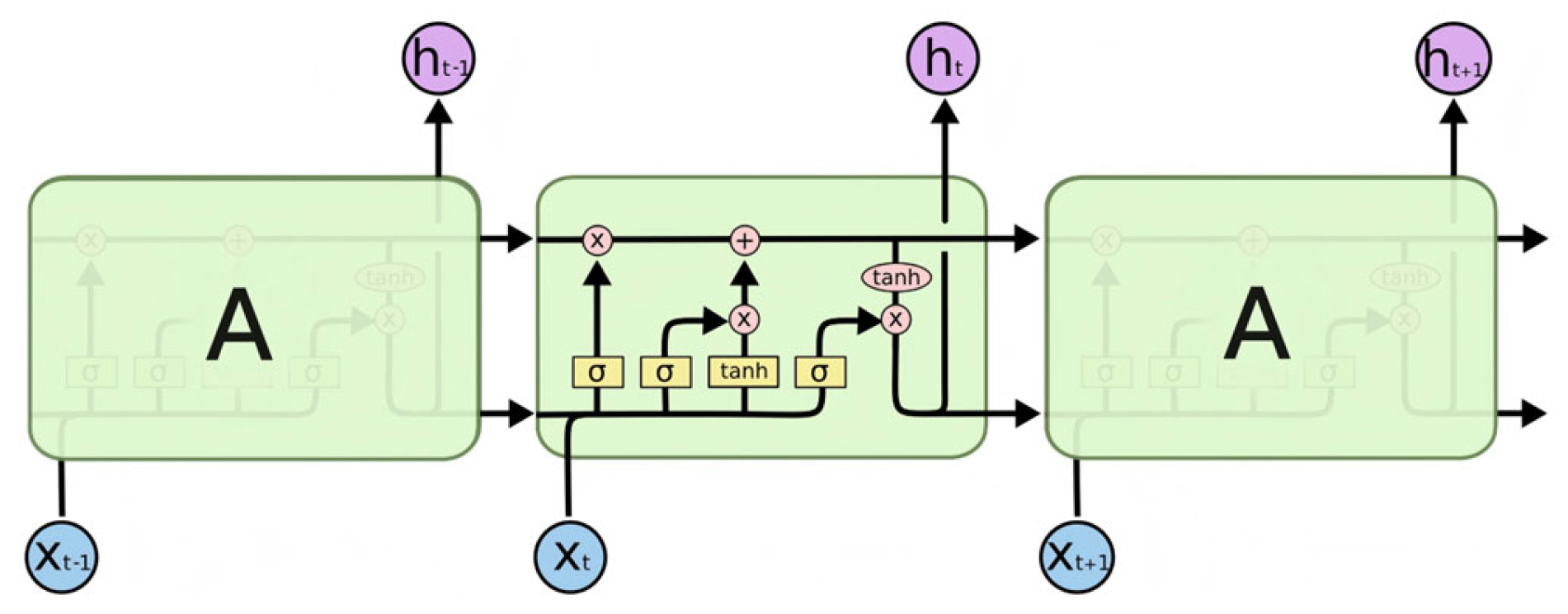

In this study for the problem of small temperature difference of OTEC and low efficiency of thermal cycle, we combined with the effect of elliptical tube bundles on heat transfer efficiency in evaporator and condenser in OTEC. Then the effect of different elliptical tube types on heat transfer coefficient is analyzed with the help of ANSYS-FLUENT 2020R2 simulation software. Finally the training of long and short-term memory network and genetic algorithm is used to establish the heat transfer coefficient with the change of elliptical tube type. Prediction model, using NSGA-II algorithm for multi-objective optimization design of heat exchanger tube type, to derive the optimization scheme of the elliptical tube type of OTEC heat exchanger. Then further improve the heat exchange performance of the heat exchanger. This study improves the heat exchanger tube type, and it is expected to provide new ideas and theoretical support for the subsequent optimization design of the heat exchanger with small temperature difference.

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

3.1. Heat Transfer Simulation of Tubular Structures

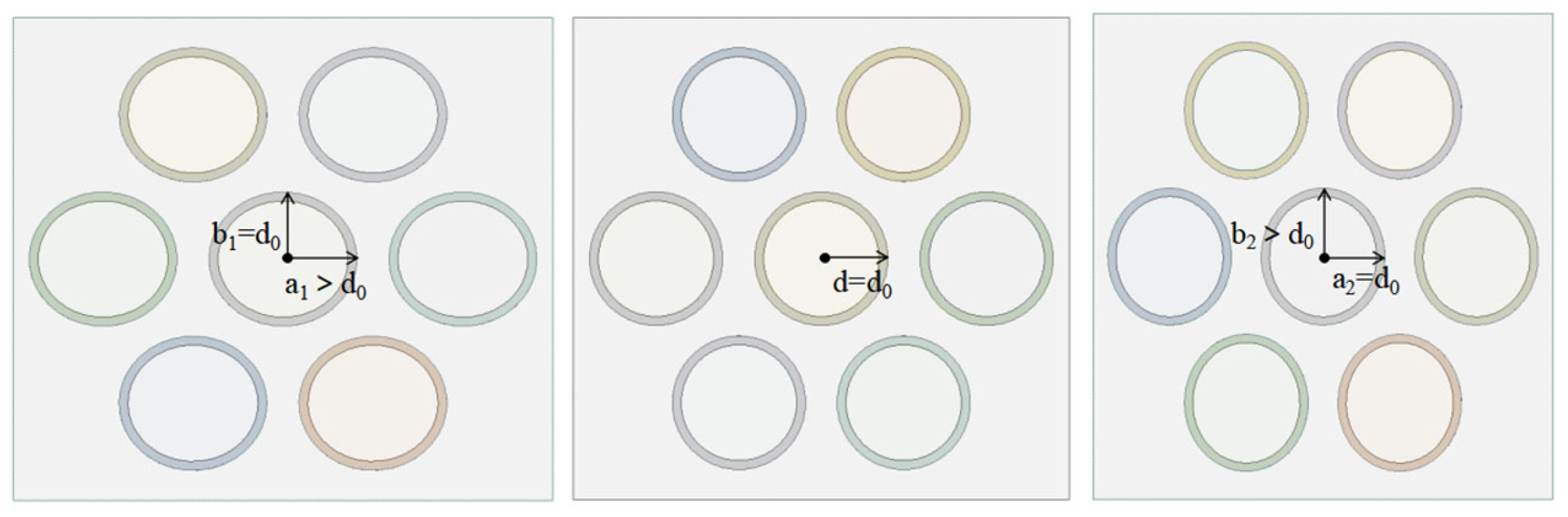

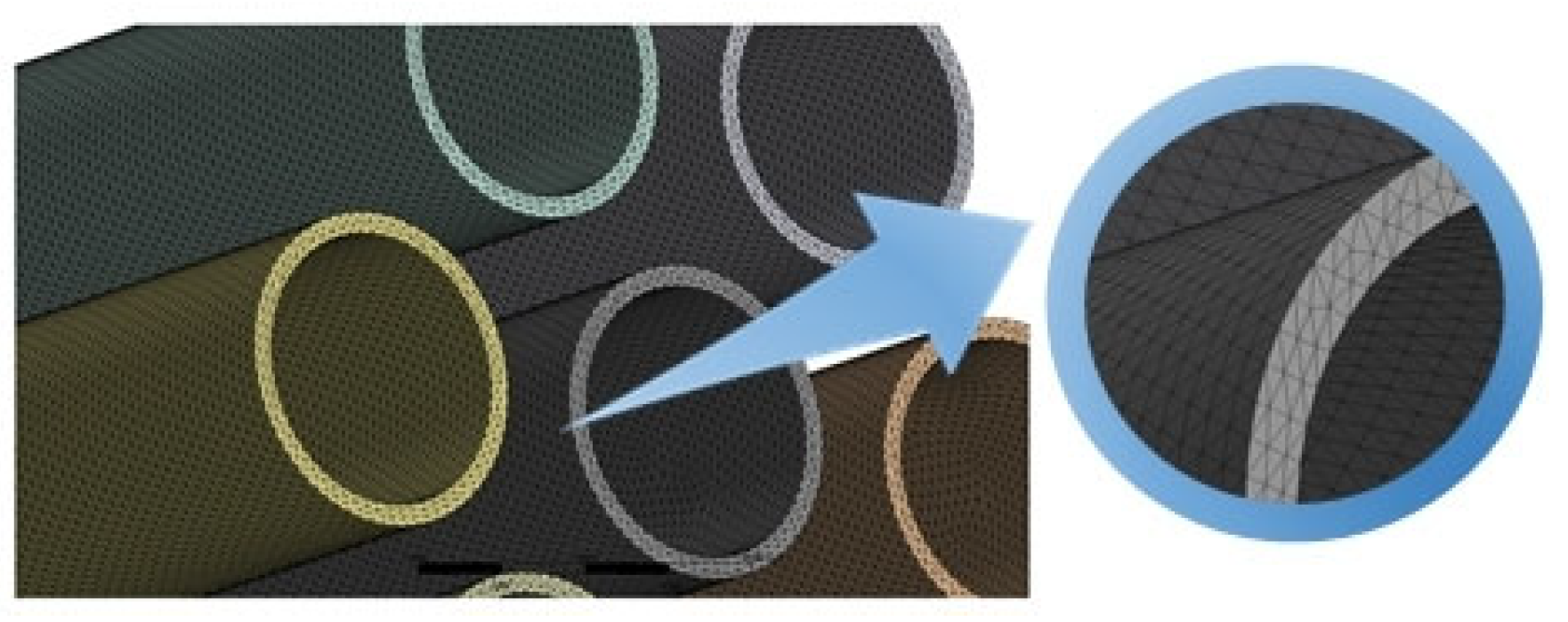

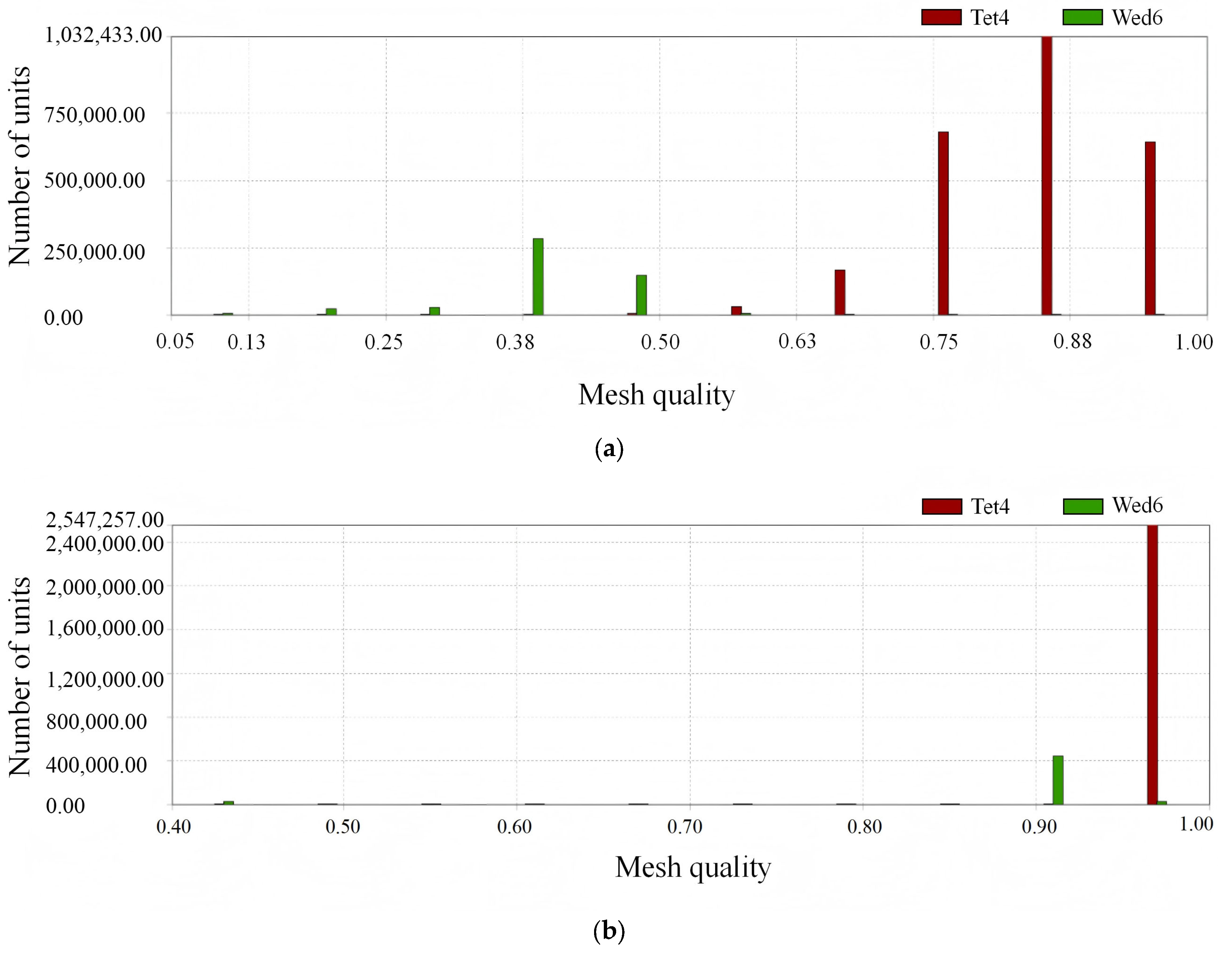

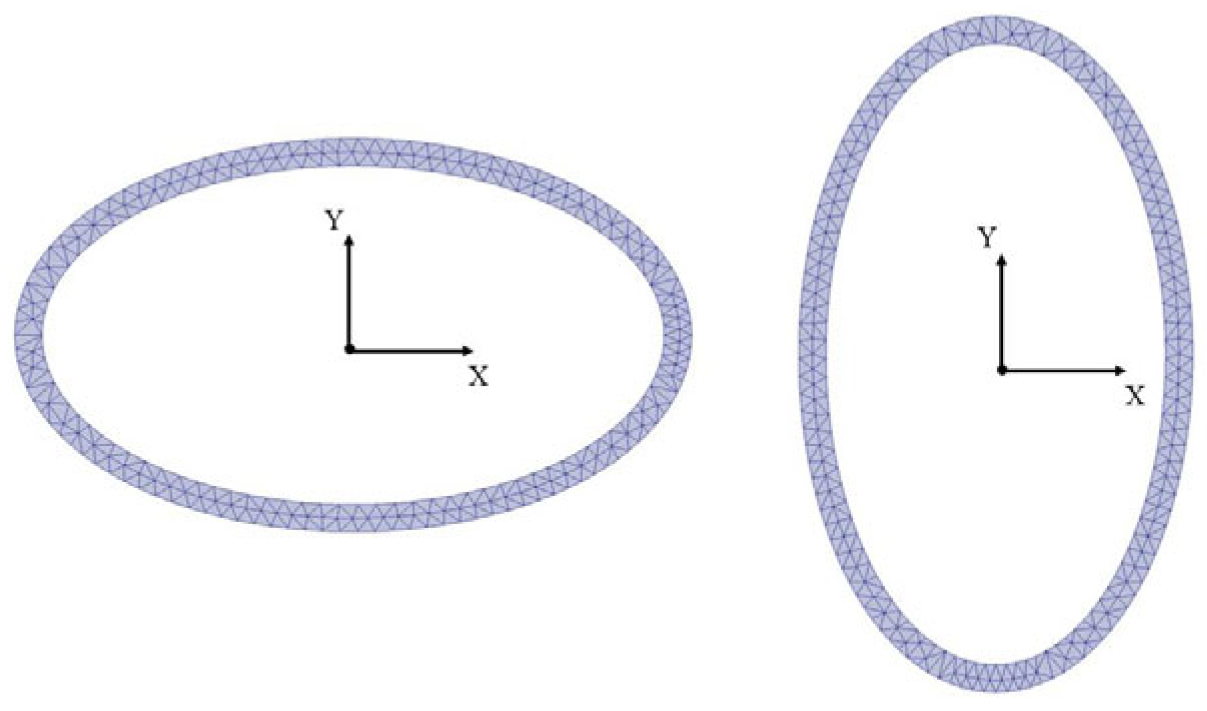

Different structural parameters of the heat exchanger tube [

51] have a certain effect on the heat transfer performance. In order to investigate the effect of the heat exchanger tube type on the heat transfer performance, this study selected oval tubes with different lengths in the horizontal direction (X-axis) and the vertical direction (Y-axis). The spacing between tubes is certain to minimize the effect of the tube spacing on the heat transfer. At the same time to ensure that the rest of the parameters are the same. Under the above conditions, we calculate the heat transfer coefficient and the cold and hot fluid outlet temperature in the evaporator and condenser, and to study the structure of variables shown in

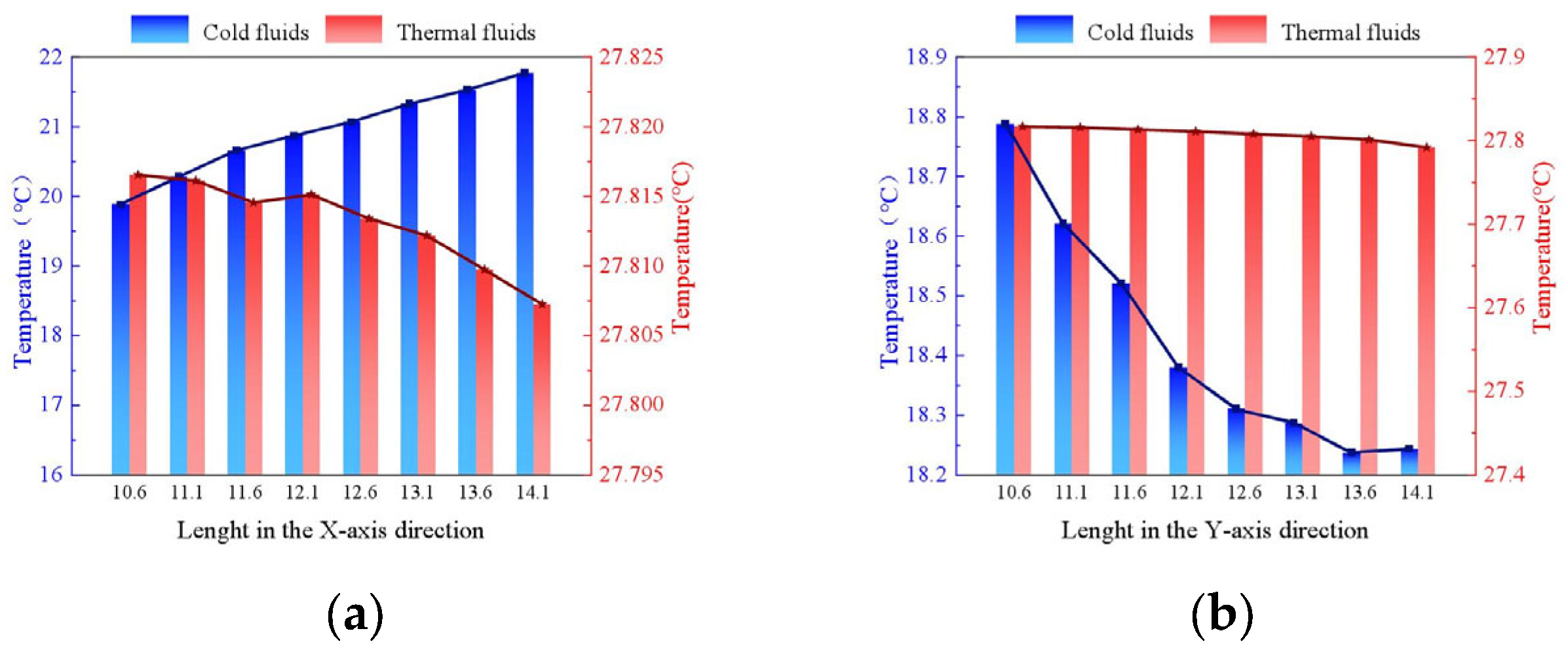

Figure 10. The simulation calculation of evaporator and condenser inlet and outlet temperatures during the change of tube type. According to the heat transfer demand of the ocean temperature energy circulation system, the heat exchanger tube length change interval is selected between 10.6 mm and 14.1 mm, that is, the change range of X and Y axes is 10.6–14.1 mm.

In order to study the effect of parameter changes in the horizontal direction, the cold fluid inlet temperature is fixed at 6 °C, the hot fluid inlet temperature is fixed at 28 °C. The length of the evaporator in the Y-axis direction is kept unchanged while the length of the X-axis direction varies within the interval of 10.6 mm to 14.1 mm, and the same sample is taken every 0.5 mm within this interval to simulate the hot and cold fluid outlet temperatures. Fix the cold fluid inlet temperature as 6 °C and the hot fluid inlet temperature as 28 °C, keep the length of the evaporator in the X-axis direction unchanged while the length of the Y-axis direction varies within the interval of 10.6 mm to 14.1 mm, and take a sample every 0.5 mm within this interval to simulate the hot and cold fluid outlet temperatures, so as to analyze the influence of the parameters in the vertical direction.

Figure 11 shows a line graph drawn based on the simulation results about the cold fluid outlet temperature and the hot fluid outlet temperature when the cold fluid inlet temperature is 6 °C, the hot fluid inlet temperature is 28 °C and only the length of the X-axis or Y-axis changes.

As can be seen from

Figure 10, when the cold and hot fluid inlet temperatures are 6 °C and 28 °C, the Y-axis length of the evaporator is kept at 10.6 mm, the cold fluid outlet temperature shows an increasing trend with the increase of the X-axis direction, and the hot fluid outlet temperature shows a decreasing trend in general; the X-axis length of the evaporator is kept at 10.6 mm, and with the increase of the Y-axis length the cold fluid outlet temperature shows a decreasing trend. In the case of the Y-axis length changing from 10.6 mm to 13.6 mm, the temperature of cold fluid decreases faster, and when the length of Y-axis changes from 13.6 mm to 14.1 mm, the temperature of cold fluid decreases slowly; the temperature of hot fluid outlet has a decreasing trend in general.

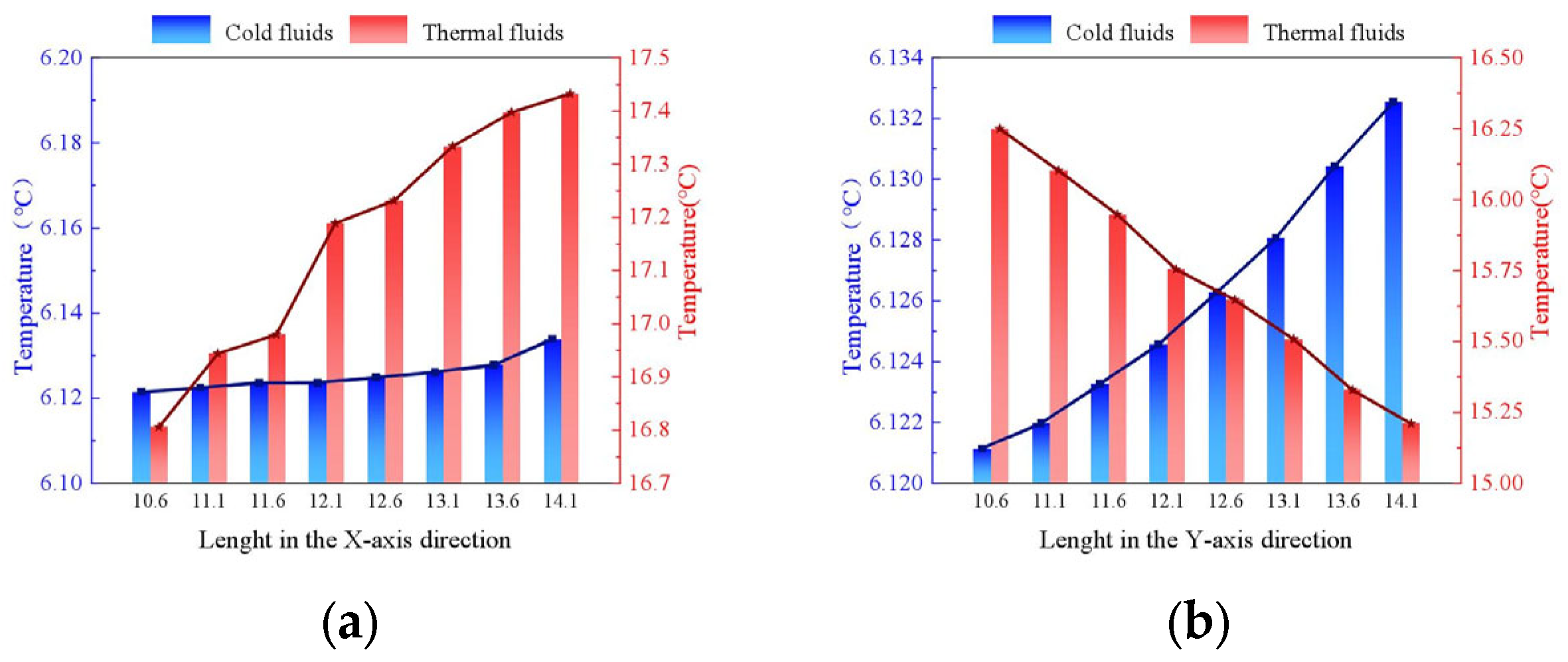

Similarly, the simulation calculation of the condenser inlet and outlet temperatures during the change of tube type is carried out. Fix the cold fluid inlet temperature of 6 °C, hot fluid inlet temperature of 20 °C, keep the condenser Y-axis length unchanged, so that the X-axis length in the in the interval of 10.6 mm to 14.1 mm changes and every 0.5 mm to take a sample for the hot and cold fluid outlet temperature simulation.

Fix the cold fluid inlet temperature of 6 °C, hot fluid inlet temperature of 20 °C, keep the length of the condenser X-axis direction unchanged, so that the length of the Y-axis direction in the interval of 10.6 mm in 14.1 mm change and in the interval of every 0.5 mm to take a sample for the hot and cold fluid outlet temperature simulation. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 12.

As can be seen from

Figure 12, when the cold and hot fluid inlet temperatures are 6 °C and 20 °C, the Y-axis length of the condenser is kept at 10.6 mm, and with the increase of the X-axis length, the cold fluid outlet temperature increases steadily within a small range from 6.12 °C to 6.14 °C, and the hot fluid outlet temperature is in an increasing trend. The X-axis length is kept unchanged, and with the increase of the Y-axis length, the cold fluid outlet temperature is in an increasing trend, and the hot fluid outlet temperature has a decreasing trend in the selected change interval.

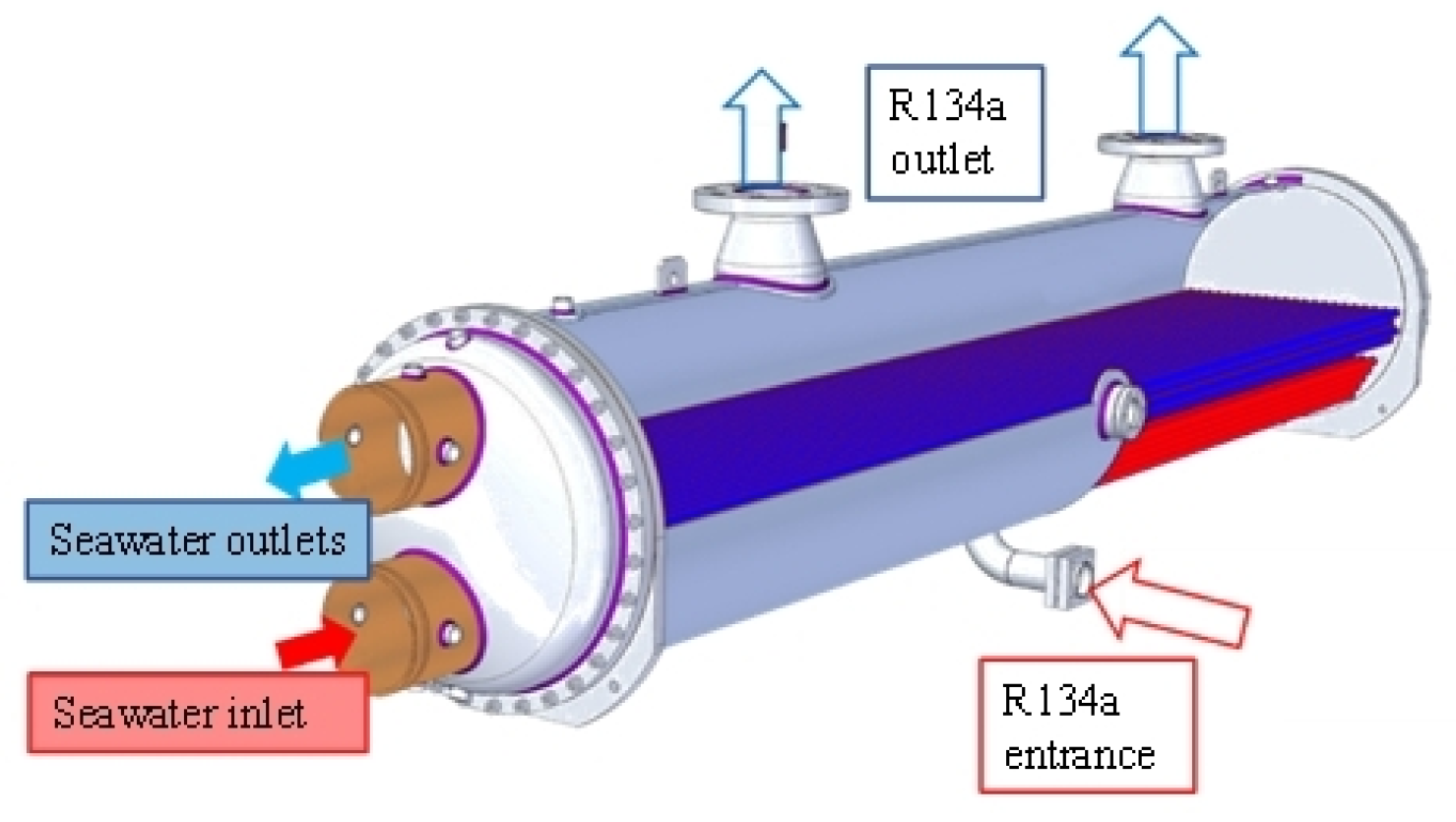

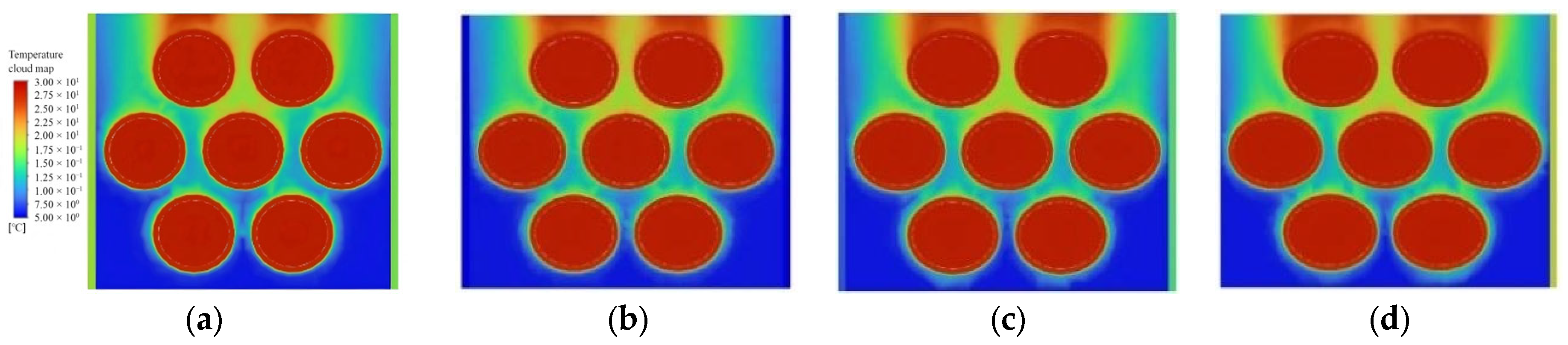

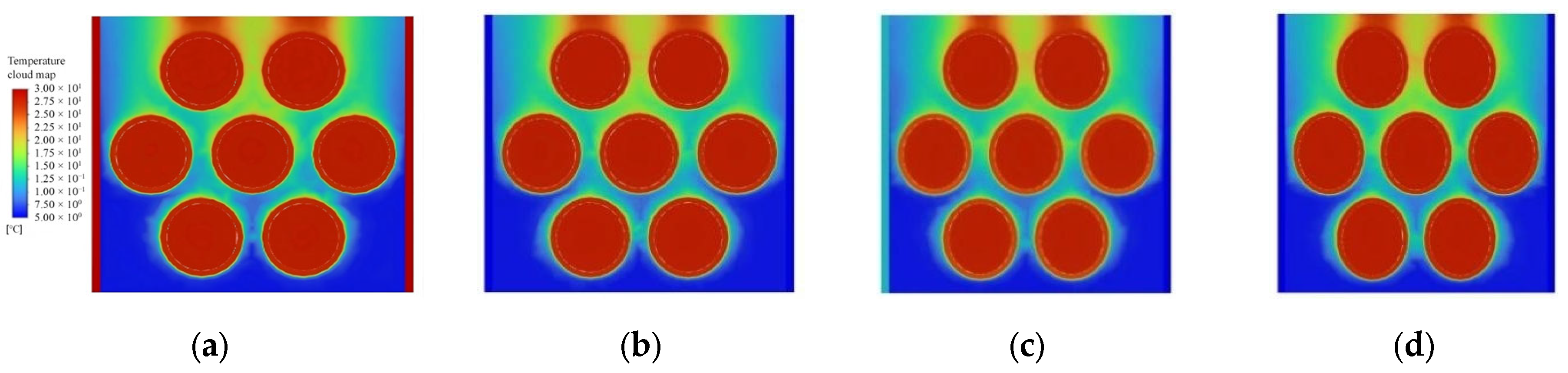

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show evaporator simulation process, shell process with R134a working fluids in different elliptical tube under the temperature cloud distribution. CFD simulation is conducted under the assumption of steady-state. There can be seen in the image that R134a by the tube process heat warm seawater. High temperature working fluids first concentrated in the tube wall around, and then began to float upward by the viscous force and buoyancy by the wall of the tube, and gradually by the liquid working fluids into gaseous working fluids.

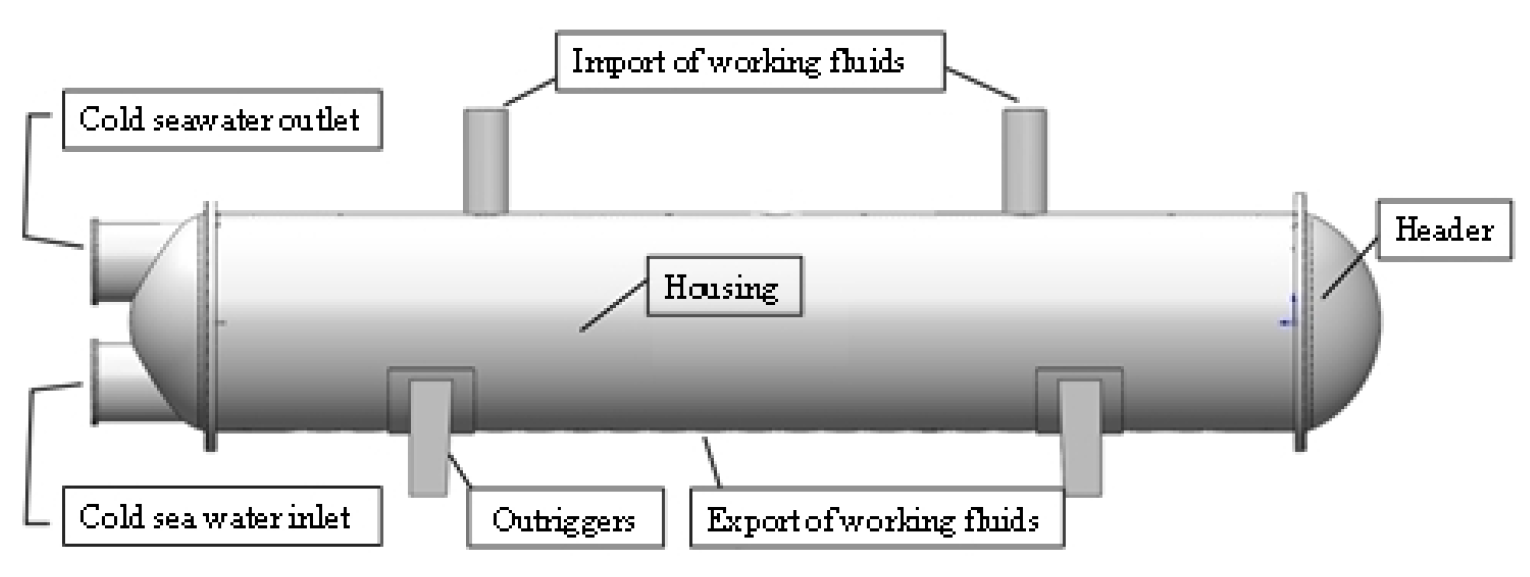

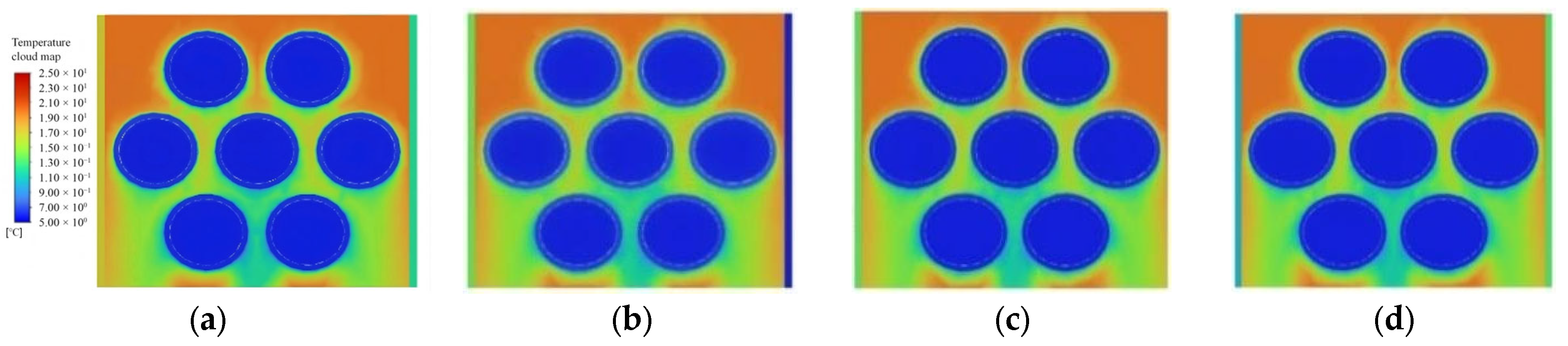

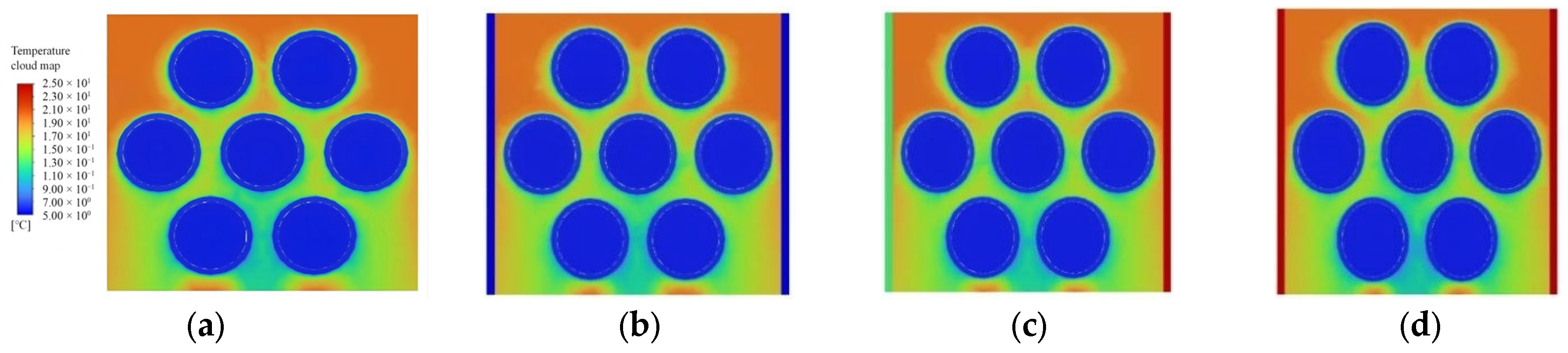

As can be seen in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, the temperature cloud distribution of R134a working fluids in the shell course of elliptical tubes of different diameters during the simulation of heat transfer in the condenser. It is seen that in the condenser, the R134a working fluids are first cooled and condensed around the tube wall, and with the increase in the number of rows of the working fluids skimming over the low-temperature heat exchanger tubes, the condensation of the working fluids is gradually accomplished.

3.2. Data Normalization Process and Model Training

Based on the heat exchanger simulation data, 40 sets of data from the evaporator and condenser are used for model training respectively. Before training, the data should be normalized. To eliminate the adverse effects of the singular sample data on the training, and improve the training efficiency and convergence speed, the preprocessed data should be restricted to between (0, 1). The normalization formula used in this study is:

In model training, the model is randomly divided into a training group and a test group. The data of the test group is not involved in model training but is used to test the accuracy of the model. To set the basic parameters of the model, while considering the way to adjust the model update weights and deviation parameters, and optimize the model to achieve better convergence, the training parameters used in this chapter are shown in

Table 6.

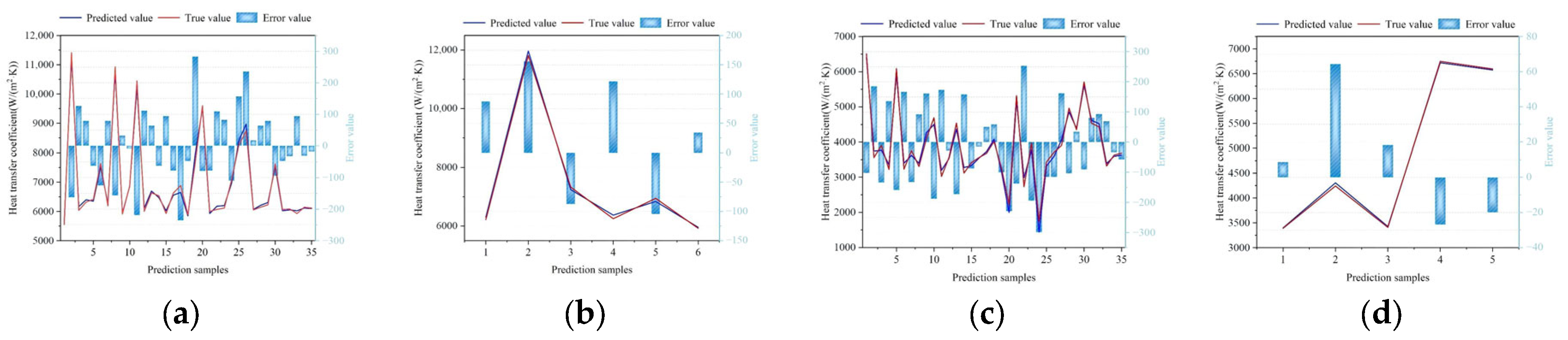

The long short-term memory network model of this design is utilized to train the inlet and outlet parameters of the evaporator and condenser under OTEC conditions. At the same time, five sets of data that not put into the training set are taken out for the validation and prediction of the model’s accuracy, the training results are shown in

Figure 17.

From the comparison of the test set prediction results with the real results, it can be seen that the error interval of the evaporator training set is −300 to 300 W/(m2·k), and the error interval of the evaporator test set is −150 to 200 W/(m2·k); the error interval of the condenser training set is −300 to 300 W/(m2·k), and the error interval of the condenser test set is −40 to 80 W/(m2·k). The maximum error of the evaporator training set is 3.414%, and the maximum error of the test set is 1.935%; the maximum error of the condenser training set is 1.523%, and the maximum error of the test set is 1.517%, which predicts this model good.

3.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

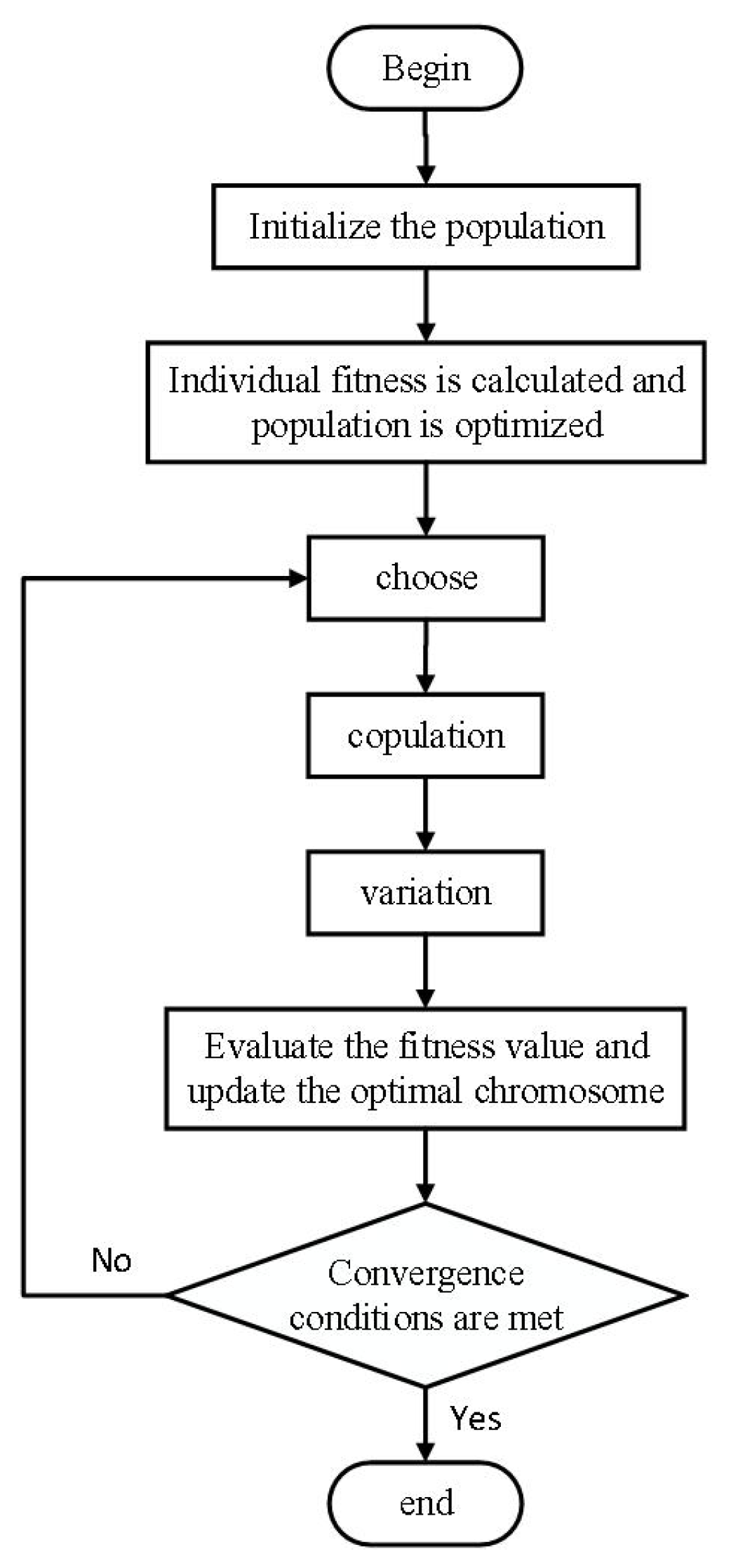

The flowchart of the genetic algorithm is shown in

Figure 18, and it can be regarded as a data training method similar to Darwinian evolution. Starting from an arbitrary initial population, individuals that are more adapted to the environment are bred through random selection, crossover, and mutation. By simulating the process of natural selection and reproduction, the population gradually evolves to better regions in the search space over generations, eventually converging to the population best suited to the environment In this section, based on the tube model trained by LSTM, the optimization study of the heat transfer model is carried out with the length of the elliptical tube in the horizontal and vertical directions as the design variables, and the heat transfer coefficient as the optimization objective. The heat transfer coefficient equation is:

where

h is the convective heat transfer coefficient,

A is the heat transfer area, ∆

T is the temperature difference between the fluid and the solid surface.

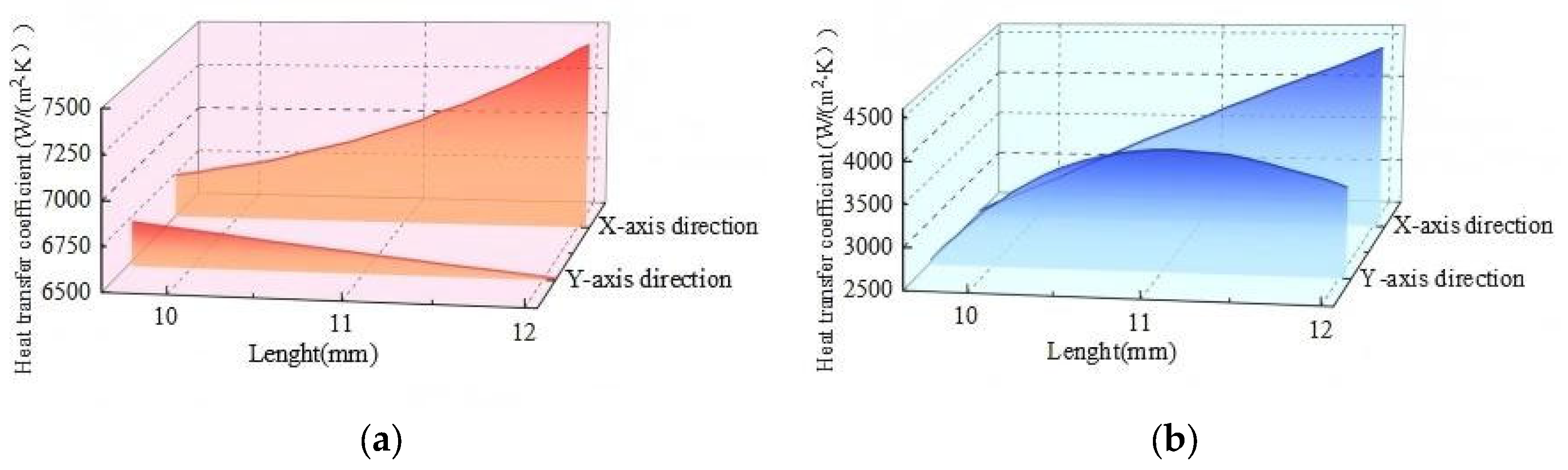

The change rule of heat transfer coefficient with tube type is predicted by genetic algorithm, and the changing trend of heat transfer coefficient with the change of long axis of the elliptical tube is obtained as shown in

Figure 19.

In the case of the given cold and hot inlet temperatures, fixed evaporator Y-axis length, the heat transfer coefficient shows an increasing trend with the increase in the length of the X-axis direction. Then fixed evaporator X-axis length, with the increase in the length of the Y-axis, the heat transfer coefficient shows a decreasing trend.

In the case of the given cold and hot inlet temperatures, the fixed condenser Y-axis length, with the increase of the X-axis length, the heat transfer coefficient tends to increase. Fixed condenser Y-axis length, with the increase of the Y-axis length, the heat transfer coefficient shows the trend of increasing first and then slowly decreasing. When fluid flows into a flatter elliptical tube, it experiences more intense streamlining and acceleration on the upper and lower walls of the pipe (in the Y-axis direction). According to Bernoulli’s principle, an increase in flow velocity leads to a decrease in static pressure, which enhancing the suction effect on the fluid, allowing the fluid in the core region to impact near the wall more effectively. When the ellipse is stretched in the Y direction (vertically) and the cross-sectional shape becomes closer to a circular pipe, the flow of fluid becomes smoother and more stable, with no intense zones of acceleration or deceleration. As it approaches a circular shape, its heat transfer performance declines. This phenomenon is consistent with the conclusions of A. Žukauskas’s review, numerical studies by Djeffal, Fares et al. [

52].

3.4. Multi-Objective Optimization

After obtaining the relationship between heat transfer coefficient and tube shape change, the improved NSGA-II algorithm based on genetic algorithm is used to take the length change of tube shape along horizontal and vertical directions as the independent variable, and the maximum heat transfer coefficient corresponding to the change of tube shape along horizontal and vertical directions and the minimum cross-sectional area of tube shape as the optimization objectives. This optimization of the tube structure can improve the heat transfer efficiency, and avoid excessive encroachment on the shell space, so as to lay a foundation for the subsequent optimization of the shell space layout.

Compared with the traditional genetic algorithm, the NSGA-II algorithm introduces the non-dominated sorting mechanism, divides the individuals in the population into different levels, uses the crowding distance to maintain the diversity of the population, and combines the non-dominated sorting and crowding distance in the selection strategy. The NSGA-II algorithm can promote global convergence and provide better performance and more comprehensive solutions for multi-objective optimization problems.

There are multiple optimization objectives in this article. Conflicts between targets cannot be quantitatively compared. It is difficult to find a solution that makes all the objective functions optimal at the same time, i.e., to find the global optimal solution, from within the interval. Therefore, for multi-objective optimization problems, the result of the optimization is usually a set of solutions that are guaranteed not to weaken at least one of the other objective functions without changing the objective function, and at the same time are not comparable concerning all the objective functions. These solutions are often called non-dominated or Pareto optimal solutions.

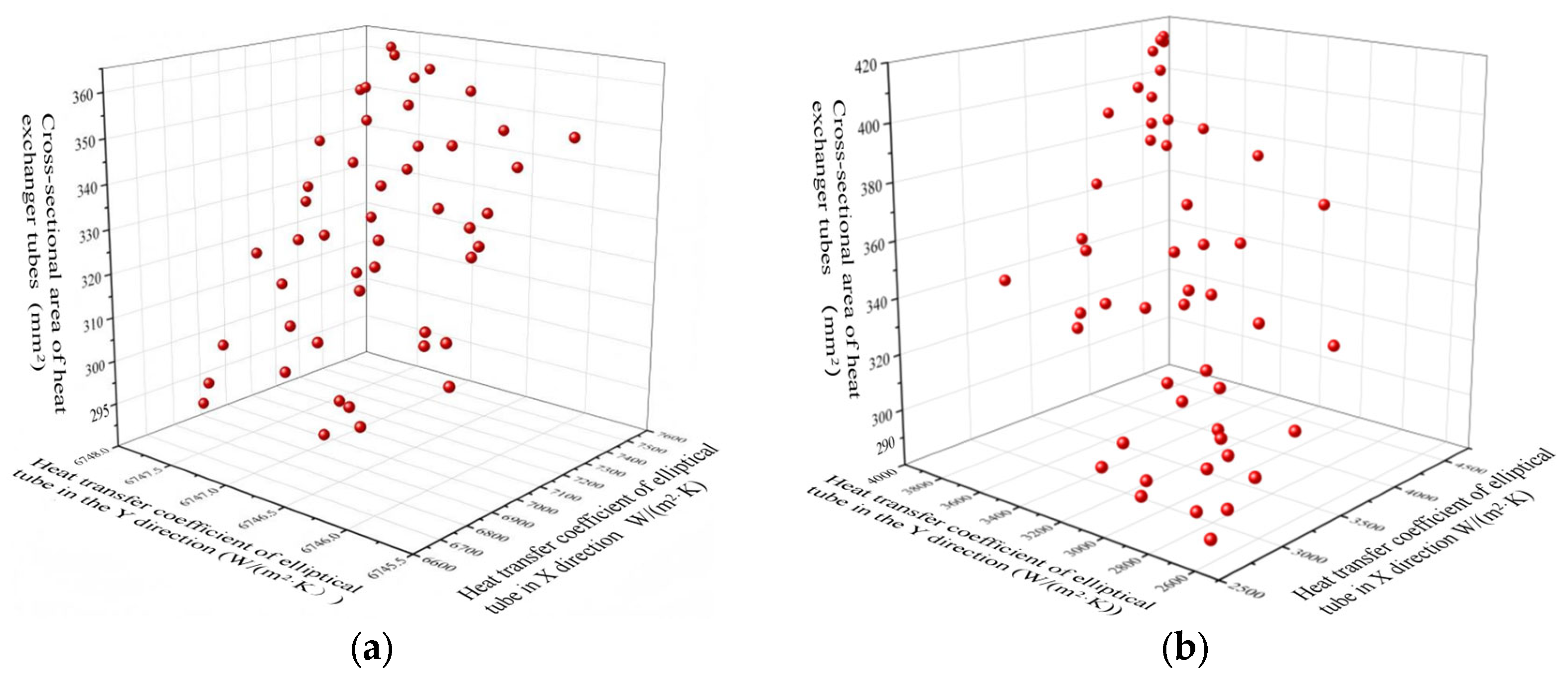

In the setup of the NSGA-II optimization algorithm, the population size is set to 50, the number of iterations is set to 200, the crossover probability is set to 0.9, the variance probability is set to 0.1, and the resulting Pareto frontier is shown in

Figure 20.

The Pareto solution set selected in the scheme largely ensures the heat transfer efficiency of the heat exchanger tube bundle while controlling the area of the heat exchanger tubes well, realizing the purpose of obtaining a higher heat transfer coefficient with a smaller heat transfer area, which can effectively control the material cost, optimize the layout of the shell process, and improve the efficiency of heat transfer.

Based on the three optimization objectives—the maximum heat transfer coefficient of the elliptical tube along the X-direction, the maximum heat transfer coefficient along the Y-direction, and the minimum cross-sectional area of the heat exchanger tubing, we set the heat transfer coefficients in the X and Y directions to be k1 and k2 respectively, and the cross-sectional area of the heat exchanger to be S. To improve heat transfer efficiency, we aim for larger heat transfer coefficients. However, higher coefficients are often accompanied by greater heat transfer areas. As the heat transfer area increases, the space for heat transfer between the hot and cold fluids is reduced. To achieve a balance between the “maximum possible heat transfer coefficient” and the “minimum possible heat transfer area,” the optimization difficulty is increased.

Theoretically, all Pareto solutions can be used for the design of heat exchanger tube configurations. However, solutions near the central region perform better in balancing these three optimization objectives. Specifically, we selected the solution closest to the ideal point and located in the central region of the Pareto front, which exhibits good balance across all objectives rather than pursuing extreme performance in any single objective.

Table 7 and

Table 8 show the three selected optimal Pareto solutions for the evaporator and condenser, respectively.

4. Conclusions

In this study, for the problem of small temperature difference of ocean thermal energy conversion and low circulating thermal efficiency, combined with the influence of elliptical tube bundles on heat transfer efficiency in the evaporator and condenser in OTEC, the prediction model of heat transfer coefficient change with elliptical tube type is established, and the NSGA-II algorithm is used to carry out the multi-objective optimization design of the heat transfer tube type, and the following conclusions are obtained.

4.1. Effect of Axial Length on the Heat Transfer Coefficient of Tube Heat Exchanger

Heat transfer coefficient with the tube type in the horizontal and vertical length changes, evaporator and condenser show different trends: evaporator heat transfer coefficient with the increase in the length of the horizontal direction become larger, with the increase in the length of the vertical direction is reduced. Condenser heat transfer coefficient with the increase in the length of the horizontal direction is increased, and with the increase in the length of the vertical direction, condenser heat transfer coefficient shows the trend of increasing first and then slowly decreasing. The conclusions obtained lay the foundation for subsequent multi-objective optimization. The research in this paper is limited to the description of macroscopic phenomena (e.g., axial length affects heat transfer coefficient). However, since the topic of this paper is to improve the heat transfer efficiency of heat exchangers, there is no need for an in-depth theoretical model of the internal microscopic state of the heat exchanger tube.

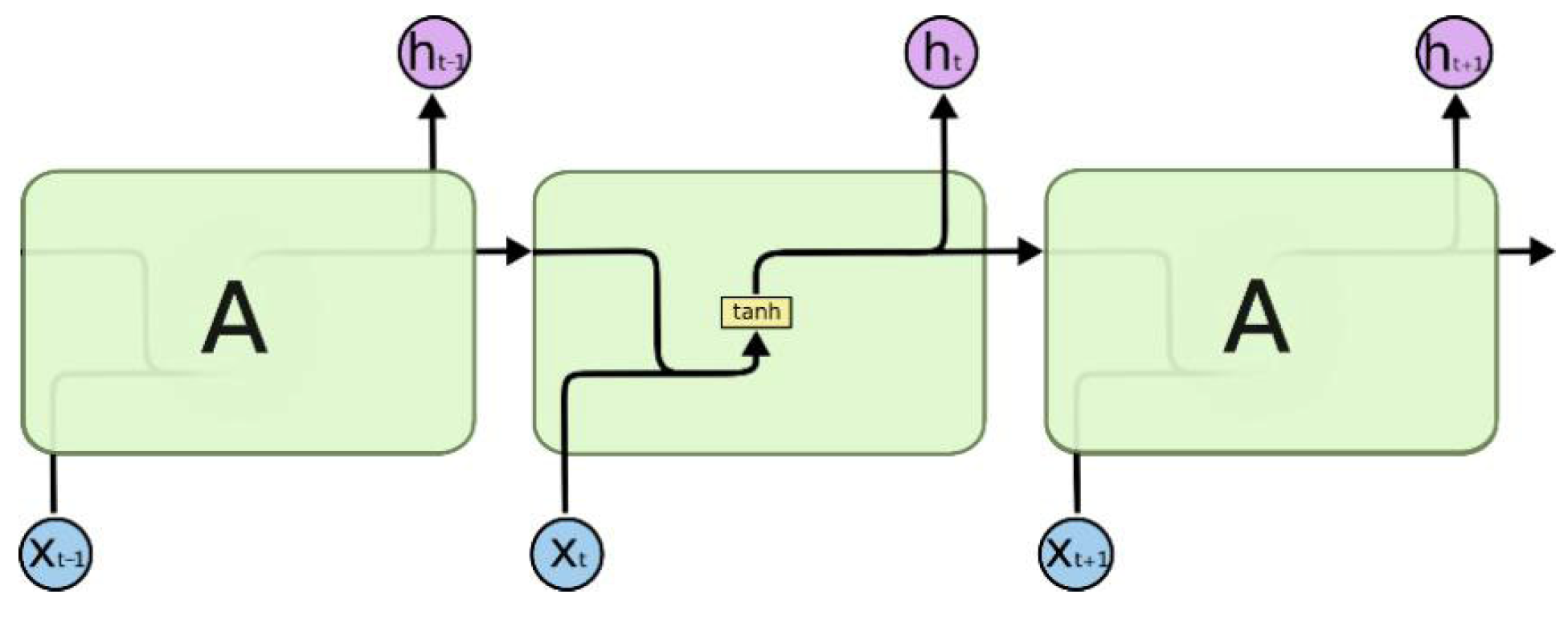

4.2. Application of LSTM in Predicting Heat Transfer Coefficient in Elliptical Tubes

In this study, LSTM is applied to establish a prediction model linking the heat exchanger heat transfer coefficient with the X and Y axis of the elliptical tube, which reduces the prediction error caused by the sensitivity of RNN to short-term inputs, and better captures the long-term relationship in the sequence data to improve the accuracy of the prediction. The maximum error of the evaporator training set is 3.414%, and the maximum error of the test set is 1.935%. The maximum error of the condenser training set is 1.523%, and the maximum error of the test set is 1.517%, In the

Section 4 of the experiment the error of the mathematical model is 5–10%, so the prediction effect is good. However, the amount of data in this study is relatively limited, although we have tried to control the risk of overfitting during model design and training. Nonetheless, validating the model’s generalization ability on a larger and more diverse dataset remains an important direction for future work.

4.3. Design pl

In this study, a multi-objective optimization method for OTEC heat exchangers is proposed based on the improved NSGA-II algorithm of the genetic algorithm, and a design scheme with better heat transfer performance is obtained to realize the coexistence of a larger heat transfer coefficient and a smaller tube area. The optimized evaporator heat exchanger tube with X-axis heat transfer coefficient of 6852 W/(mm2·k), Y-axis heat transfer coefficient of 6749 W/(mm2·k) and cross-sectional area of 289.5 mm was finally obtained; the condenser heat exchanger tube with X-axis heat transfer coefficient of 3160 W/(mm2·k), Y-axis heat transfer coefficient of 3528 W/(mm2·k) and cross-sectional area of 328.7 mm was obtained. It should be noted that this study employed an idealized heat exchanger model and did not consider the actual pinch point temperature difference. This simplification may overestimate system efficiency and underestimate the required heat exchange area. However, this does not affect the comparative conclusions regarding heat exchange efficiency and tube types presented in this paper. A detailed analysis of the impact of the pinch point on system performance and economic viability will be the core focus of our future research efforts.

4.4. Multi-Objective Opimization

The OTEC heat transfer model (LSTM-EVA) based on long and short-term memory network and efficiency improvement study proposed in this study explores the optimal heat transfer efficiency of ocean thermal energy heat transfer tubes, solves the problem of improving the heat transfer efficiency while avoiding excessive encroachment on the shell range space, and can provide ideas and references for the subsequent ocean thermal energy research. Because the article uses a simple oval pipe, the cost is low, and it is of great significance for large-scale production and application.