Abstract

Organophosphorus esters (OPEs), widely utilized as flame retardants and plasticizers, are physically incorporated into those products and exhibit semi-volatility, resulting in release throughout their lifecycle. The ocean serves as a significant sink and plays a pivotal role in the global distribution and environmental fate of OPEs. However, the OPEs’ behavior and ecological effects in marine systems are not well understood. This review systematically examines recent advances in the sources, transport pathways, transformation mechanisms, and distributions of OPEs in the marine environment, and it also addresses current research limitations and suggests directions for future work. It is found that OPEs predominantly enter the marine environment through terrestrial input and in situ release; the transportation means include river input, long-range atmospheric transport, air–sea exchange, and oceanic circulation; and the degradation processes of OPEs are recognized as hydrolysis, photodegradation, and biodegradation. The distributions of OPEs in marine environments vary in different media, with their concentrations observed to range from pg m−3 to ng m−3 in marine air, ng L−1 to hundreds of ng L−1 in seawater, and pg g−1 dw to ng g−1 dw in sediments. The distributions of different species of OPEs are affected by many factors, such as compound properties, environmental conditions, and policy regulations. Comparisons between different regions and different seasons need to be further studied, and predictive models should be developed to better assess ecological risks and exposure pathways of OPEs.

1. Introduction

Organophosphate esters (OPEs) are a group of synthetic chemicals characterized by the general structure of O=P(OR)3 [1]. These compounds have been widely utilized as flame retardants and plasticizers [2]. OPEs were previously regarded as an ideal substitute for brominated flame retardants (BFRs) [3] due to their simpler production processes, lower cost, effective flame retardant performance, and good durability [4]. In recent years, with global restrictions on BFRs [5,6], OPE usage has surged from approximately 0.68 million tons in 2015 to over 100 million tons in 2018 [7].

Based on substituent differences, OPEs are typically categorized into alkyl-, aryl-, and chlorinated-OPEs [8]. Common alkyl-OPEs include triethyl phosphate (TEP) and tri-n-butyl phosphate (TnBP); typical aryl-OPEs include triphenyl phosphate (TPhP) and tricresyl phosphate (TCP); major chlorinated OPEs include tri(2-chloroethyl) phosphate (TCEP), tri(2-chloroisopropyl) phosphate (TCPP), and tri(1,3-dichloroisopropyl) phosphate (TDCPP) [3,4,9]. These compounds generally exhibit high chemical stability, moderate water solubility, and a relatively wide range of octanol–water partition coefficients (lgKow) [10,11], as detailed in Table 1. Their environmental migration and distribution behaviors vary due to differences in physicochemical properties [8,12]. For example, the water solubility of OPEs generally decreases with increasing molecular weight [11]. And chlorinated OPEs tend to exhibit stronger hydrophobicity and adsorption properties, making them more prone to accumulation in sediments and organisms. Trimethyl phosphate (TMP) and TEP possess high water solubility, whereas TCIP is virtually insoluble in water [13]. Most OPEs exhibit lgKOW values greater than zero, reflecting their hydrophobic nature and tendency to adsorb onto soil and sediments or accumulate within organisms [14,15,16,17]. Significant variations in vapor pressure exist among different OPEs. For instance, TEP and TCPP exhibit high vapor pressures, enhancing their volatility and potential for atmospheric entry, where they may subsequently adsorb onto particulate matter [8,18], enabling long-range transport. Table 1 summarizes the structures, names, abbreviations, and physicochemical properties of commonly studied OPE compounds.

In applications, chlorinated OPEs are primarily used as flame retardants due to their excellent fire-retardant properties [18], finding widespread use in building materials, insulation foams, and electronic components. Non-chlorinated OPEs are typically employed as plasticizers to enhance the flexibility of plastics and polymers. Additionally, OPEs serve as defoaming stabilizers, floor polishes, lubricants, varnish additives, and hydraulic fluid additives [8,19]. Notably, most OPEs are incorporated into products through physical mixing rather than chemical bonding [9,20] and exhibit semi-volatile properties. Consequently, OPEs readily migrate into environmental media via volatilization, leaching, and abrasion [14,21,22], leading to increasing detection rates in the environment. To date, OPEs have been detected in diverse environmental media including air, water, sediments, soil, and biological organisms [2,6,14]. These findings have raised concerns about the potential toxicological impacts of OPEs on ecosystems and human health [23].

The marine environment serves as a significant sink for OPEs. Current research indicates that OPEs can enter the ocean through multiple pathways, including river input [24,25,26], atmospheric deposition [27,28,29], and in-suit plastic degradation [30]. For instance, chlorinated OPEs, due to their strong hydrophobicity, are more likely to adsorb onto particulate matter and eventually enter sediments and organisms [3]; while certain highly volatile alkyl OPEs can affect distant marine areas through atmospheric transport [10]. The widespread use of OPEs, along with their substantial release to marine environment and resulting environmental and ecological effects, has prompted extensive scientific concern [30]. However, systematic research on OPEs in the marine environment is still insufficient, especially lacking data from open sea and deep-sea regions. Their environmental behavior, migration and transformation mechanisms, and multi-media distribution patterns require further clarification. Therefore, this review systematically summarizes the latest research advances on the sources, migration pathways, distribution characteristics, and influencing factors of OPEs in marine systems. It aims to identify the key knowledge gaps in current research and propose future research directions, with the goal of providing important scientific basis for related mechanism research, environmental policy formulation, and risk assessment.

Table 1.

Structures, names, abbreviations, and physicochemical properties of commonly studied OPEs.

Table 1.

Structures, names, abbreviations, and physicochemical properties of commonly studied OPEs.

| Category | Compound | Abbr. | Molecular Formula | Molecular Mass | lgKow | Solubility (mg/L, 25 °C) | Structural Formulae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: alkyl- | Trimethyl phosphate | TMP | C3H9O4P | 140.07 | −0.7 | 3.00 × 105 |  |

| Triethyl phosphate | TEP | C6H15O4P | 182.16 | 0.8 | 5 × 105 |  | |

| Tri-n-butyl phosphate | TnBP | C12H27O4P | 266.32 | 4.0 | 280 |  | |

| Tri-iso-butyl phosphate | TiBP | C12H27O4P | 266.31 | 3.6 | 3.72 |  | |

| Tripropyl phosphate | TPP | C9H21O4P | 224.23 | 2.4 | 6450 |  | |

| Tris(2-ethylhexyl)phosphate | TEHP | C24H51O4P | 434.64 | 9.4 | 2 |  | |

| Tris(2-butoxyethyl)phosphate | TBOEP | C18H39O7P | 398.48 | 3.8 | 1100 |  | |

| Group B: aryl- | Triphenyl phosphate | TPhP | C18H15O4P | 326.29 | 4.6 | 1.9 |  |

| 2-Ethylhexyl diphenyl phosphate | EHDPP | C20H27O4P | 362.40 | 6.3 | 1.9 |  | |

| Tri-m-Tolyl Phosphate | TmCP | C21H21O4P | 368.36 | 5.1 | 1.20 × 10−2 |  | |

| Tri-o-Tolyl Phosphate | ToCP | C21H21O4P | 368.36 | 5.1 | 0.36 |  | |

| Cresyl diphenyl phosphate | CDP | C19H17O4P | 340.31 | 4.5 | 0.24 |  | |

| Bisphenol-A bis(diphenyl phosphate) | BDP | C39H34O8P2 | 692.63 | 7.4 | 0.42 |  | |

| Group C: chlorinated- | Tris (2-chloroethyl) phosphate | TCEP | C6H12Cl3O4P | 285.48 | 1.4 | 7000 |  |

| Tris(1-chloro-2-propyl)phosphate | TCPP | C9H18Cl3O4P | 327.56 | 2.6 | 1200 |  | |

| Tris(1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate | TDCPP | C9H15Cl6O4P | 430.90 | 3.8 | 1.5 |  |

Note—abbr.: abbreviation; lgKow: octanol–water partition coefficient (adapted from [8,30]).

2. Sources, Transport, and Degradation of OPEs in Marine Environments

2.1. Source of OPEs in Marine Environments

The ocean serves as a significant reservoir for organic pollutants. Consequently, it plays a crucial role in the environmental transport, fate, and sinks of OPEs at both regional and global scales [31]. Marine OPEs primarily originate from two major sources: terrestrial inputs [18,24,25,26,27,28,29] and in situ releases within the marine environment [32,33]. Among these, terrestrial sources constitute the predominant contributor of OPEs in marine systems [18]. For instance, OPEs are widely incorporated as flame retardants and plasticizers into industrial products such as plastics, furniture, electronic devices, and construction materials [8,18,34]. OPEs may be released into the environment through wastewater [35,36], exhaust gases [37], and solid waste during manufacturing, usage, and disposal processes [14,38,39] of these materials. Furthermore, the use of consumer products, including textiles, coatings, adhesives, and personal care products, also leads to environmental emission of OPEs. Additionally, tire wear particles generated during transportation, as well as fuels and lubricants, contain OPEs that can indirectly enter marine waters via surface runoff and atmospheric deposition [40,41]. Effluents from municipal wastewater treatment plants, along with pesticide residues and plastic film remnants derived from agricultural activities, may ultimately reach the ocean through fluvial transport and soil leaching [3,42].

Internal sources within the marine environment also contribute to OPEs release [32,33]. Marine plastics and microplastics may release OPEs through physical abrasion, photodegradation, and biodegradation. OPEs originating from ship coatings, hydraulic fluids, and offshore platform equipment enter seawater via corrosion and leakage. Those accumulated in seabed sediments can be resuspended and released due to disturbances such as ocean currents, dredging activities, or bioturbation [26,43]. Moreover, the uptake and excretion of OPEs by marine organisms facilitate their recycling within the water column [44]. In summary, the sources of OPEs exhibit both the extensive nature of terrestrial inputs and the complexity of marine endogenous releases, collectively forming their multi-source characteristics in the marine environment.

2.2. Transport of OPEs in Marine Environments

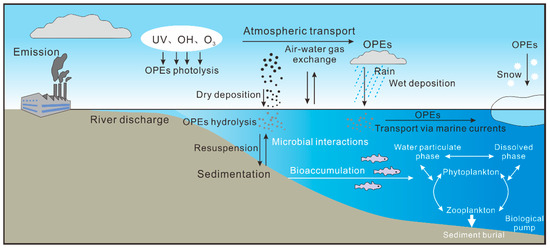

The transport of OPEs in the marine environment is a complex, multi-medium, multi-pathway process (Figure 1). Key pathways include riverine transport, atmospheric transport, sea–air exchange and oceanic circulation, which collectively determine the spatial distribution and ultimate fate of OPEs in the global ocean.

- (1)

- Riverine transport serves as an important pathway for the transmission of OPEs in coastal waters [30]. Terrestrial OPEs enter rivers through wastewater discharge, surface runoff, and industrial effluents, subsequently entering coastal environments via estuaries. During this process, estuaries often function as “filters”, where some OPEs undergo migration and transformation due to particle adsorption or sedimentation. The remaining portion disperses along the coast with freshwater plumes and undergoes long-distance migration driven by coastal currents and ocean currents, ultimately being transported to the open ocean [26,45,46,47]. For instance, the Mackenzie River in Canada discharges into the Arctic, where the concentration of OPEs in nearshore waters and sediments increases. This observation supports the hypothesis that riverine transport and discharge are key sources of OPEs in the Canadian Arctic [43]. Based on the annual runoff volume of Germany’s Elbe River, approximately 50 tons of OPEs enter the North Sea each year [48]. Based on annual river discharge estimates, approximately 113 tons of TPPO enter the Bohai Sea annually, with roughly 7 tons, 1.5 tons, and 3.4 tons of OPEs entering the Liaodong Bay, Laizhou Bay, and the Bohai Sea, respectively [24].

- (2)

- Atmospheric transport also provides a significant pathway for OPEs entering the marine environment. Long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) can carry OPEs originating from industrial zones and urban clusters to remote marine areas [49]. The atmosphere serves as a medium for the long-distance transmission of these pollutants. Atmospheric OPEs primarily exist in gaseous and particulate-bound forms, entering surface seawater through dry deposition (e.g., aerosol deposition) and wet deposition (e.g., precipitation processes like rain and snow) [50,51]. Substantial data supports the existence of this phenomenon. For instance, cruise data from East Asia to the Arctic indicate that the concentration of OPEs in aerosol samples collected from the Sea of Japan can reach as high as 2900 pg/m3 [49]. The production and utilization of OPEs by Asian countries significantly influence the atmospheric concentration of these compounds in this region. Additionally, research conducted in the North Sea demonstrates that OPEs emitted from urbanized and industrialized areas in Western Europe are transported to the North Sea via LRAT [52]. However, it is worth noting that a consensus on the duration for OPEs can stably exist in the atmosphere has not yet to be reached [30]. Earlier studies suggested OPEs as a potentially “environmentally friendly” alternative for PBDEs due to their supposed low persistence in the environment and presumed lack of LRAT [43,53]. In contrast, recent research indicates that OPEs can facilitate long-distance transport over extended time scales [50,54]. Data comparing different compound structures reveal that long-distance transmission is primarily associated with chlorinated OPEs [54]. This finding implies that the transport of OPEs is closely related to variations in their physical and chemical properties, as well as their stability and degradation characteristics in both air and water [30].

- (3)

- Air–water exchange is the key interfacial process governing the transfer of OPEs from the atmosphere into seawater. This process involves multiple mechanisms including gas diffusion, dry deposition, and wet deposition [55]. Gaseous OPEs can enter seawater via gas–liquid molecular diffusion, while OPEs adsorbed onto particulate matter enter the ocean directly through deposition. Dry deposition fluxes of OPEs ranging from 4 to 140 ng/m2/d have been observed in tropical and subtropical regions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans [54]. Particulate OPEs observed in the atmosphere across different ocean regions indicate that atmospheric dry deposition [37] can remove particulate OPEs from the atmosphere. Rainfall and snowfall effectively remove OPEs from the atmosphere and rapidly transport them to the ocean surface [47,56,57,58]. Highly water-soluble OPEs are also readily removed by wet deposition. High concentrations of OPEs have been observed in some terrestrial rainwater samples [52,59], underscoring the significance of wet deposition. In high-latitude oceans, snowfall effectively removes atmospheric OPEs over the Arctic, Southern Ocean, and Antarctica. High OPEs concentrations observed in snow samples from Arctic and Antarctic expeditions underscore the significance of snowfall deposition [56,59]. Collectively, these processes facilitate the transfer of OPEs from the atmosphere to marine environments and significantly influence the subsequent accumulation of pollutants and their transfer through food web within marine ecosystems [57].

- (4)

- Seawater can also serve as a transport medium for organic pollutants, facilitating the long-distance movement of OPEs. Compared with the open seas, coastal seas will have higher levels of OPEs based on the receiving large inputs of water-bound OPEs [15,60]. Once in the ocean, OPEs can be subject to long-range transport via oceanic circulation [30]. For example, the transport of OPEs in seawater, driven by seawater dynamics, appears to be confined to the Canadian Arctic [43] and the North Atlantic [26]. Additionally, OPEs enter aquatic environments through atmospheric deposition and riverine input, subsequently undergoing a series of processes before being sequestered in deep-sea sediments. Dissolved organic pollutants tend to adsorb onto particles or plankton, and through the sinking of these particles and the vertical migration of zooplankton, they are removed from surface waters and transported to the deep sea for storage in seabed sediments [61,62]. Consequently, OPEs accumulate in seabed sediments, forming repositories in various marine regions. A significant quantity of OPEs has been detected in the sediments of the Yellow Sea, Bohai Sea, and other locations in China [15,63,64]. Additionally, the five-year contribution of OPEs in the sediments of the Canadian Arctic continental shelf has reached 4.1 × 103 tons [43]. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring and assessing the OPEs pollution in marine fauna, particularly in remote sea areas, deep-sea basins, and trenches.

Furthermore, global climate change can also significantly influence OPEs transport behavior. Melting polar and mid-latitude glaciers release OPEs previously frozen in ice and snow back into seawater and surrounding environments. This process not only alters regional pollutant composition but may also enhance sea–air exchange fluxes by modifying fugacity gradients [65]. For example, along the eastern Greenland coast, freshwater influx from melting ice results in local seawater OPEs concentrations that are 2–5 times higher than those in the open waters of the Fram Strait [30,56], demonstrating the potential amplifying effect of climate feedback on pollutant transport [63,66].

In summary, the migration pathways of OPEs in the marine environment are complex and their impact is widespread. Therefore, there is an urgent need to strengthen systematic research in remote areas such as the open ocean, deep sea, and polar regions.

2.3. The Environmental Degradation of OPEs in Marine Environments

The degradation of OPEs in marine environments is a critical component of their fate and behavior, primarily involving three pathways: hydrolysis, photochemical degradation, and biodegradation. These processes influence the persistence, mobility, and ecological risks of OPEs.

- (1)

- The hydrolysis of OPEs fundamentally involves a nucleophilic substitution process [67]. There are two primary mechanisms of hydrolysis: one in which hydroxide ions (OH−) or water (H2O) attacks the phosphorus (P) atom, and another in which water (H2O) attacks the carbon (C) atom [68,69]. The cleavage of ester bonds during the hydrolysis process is primarily influenced by the pH value of the reaction solution and the structure of the side chain [11,45]. With increasingly basic pH the order of OPEs stability was group A (with alkyl moieties) > group B (chlorinated alkyl) > group C (aryl) [11]. For group A with alkyl moieties, an increase in the number of carbon atoms in the chain corresponds to a decrease in the rate of hydrolysis [54,56].

- (2)

- Photochemical degradation represents a significant transformation pathway for organic pollutants in aquatic environments [10]. The photochemical degradation of OPEs in water can be categorized into direct and indirect photolysis [67]. Direct photolysis occurs when OPEs absorb light energy directly [70], whereas indirect photolysis involves the absorption of light energy by other chemical substances, such as natural organic matter, which subsequently transfer energy to transient reactive species (e.g., OH and singlet oxygen) that induce the degradation of OPEs [71]. Chlorinated and alkyl OPEs are particularly resistant to direct photolytic degradation, primarily due to their lack of absorption bands across the ultraviolet-visible spectrum, with only aryl OPEs exhibiting absorption bands within the range of 220–400 nm [72]. In real marine environments, indirect photolysis often plays a more significant role due to the influence of water transparency and dissolved substances.

- (3)

- Biodegradation is one of the key pathways for OPEs transformation in the environment, particularly in water bodies rich in microorganisms (such as rivers, estuaries, and sewage discharge areas) [73]. This degradation typically relies on microbial enzyme systems for the stepwise hydrolysis of phosphate bonds, involving sequential catalysis by phosphotriesterases, phosphodiesterases, and phosphomonoesterases [30,74]. To date, the only identified phosphotriesterase that facilitates the biodegradation of TCEP and TDCIPP is a haloalkylphosphorus hydrolase (HAD) [75]. And some recent studies have indicated that the presence of the nutrient element phosphorus (P) in water may influence the stability of these compounds [75,76,77].

In summary, the degradation of OPEs in marine environments is a complex, multi-pathway process whose efficiency is jointly influenced by compound structure and environmental conditions (e.g., pH, light exposure, microbial communities, and nutrient levels). The relative contributions of different degradation pathways in marine environments and the coupled effects of multiple processes require further investigation. Particularly, little is known about degradation behavior in extreme environments such as the deep sea and polar regions.

Figure 1.

Major sources and pathways of OPEs in coastal and open oceans (adapted from [30,78]).

3. Distribution of OPEs in Different Marine Environments

OPEs are generally semi-volatile compounds with relatively high solubility. They have been extensively detected in primary environmental media [6]: the atmosphere, seawater, and marine sediments. The concentrations of OPE pollutants in these major media across various sea areas worldwide are as follows:

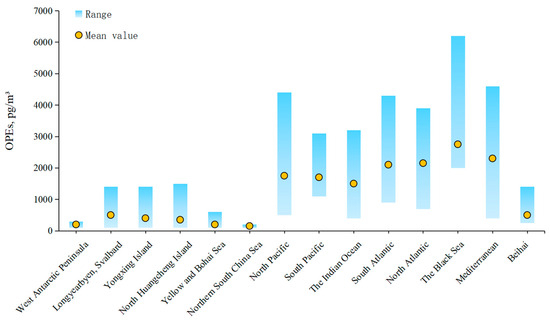

3.1. OPEs in Atmosphere

OPEs are semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs) that can be transported regionally and globally through the atmosphere. OPEs have been detected in major oceans, including the Pacific, Indian, Atlantic, and Arctic [37,49]. Reported concentrations of OPEs in global marine aerosol samples range from picograms per cubic meter (pg m−3) to several nanograms per cubic meter (ng m−3), with TCEP and tris(1-chloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TCIPP) being the predominant compounds [49]. Overall, airborne concentrations of OPEs are elevated in nearshore areas, particularly those adjacent to urban and industrial regions, followed by mid-latitude open oceans and the Arctic, with the Southern Ocean exhibiting the lowest concentrations [37,79]. The global prevalence of OPEs sharply contrasts with predictions from previous LRAT models. This discrepancy suggests that our understanding of the physicochemical properties of OPEs remains significantly inadequate [30,80].

The concentration of OPEs in the Arctic Ocean at high latitudes is as low as 29–180 pg m−3; however, near Russia and the United States, concentrations are significantly higher, reaching approximately 600 pg m−3 [56,57]. In contrast, concentrations in the North Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and Black Sea at mid-latitudes can reach ng m−3 [65]. OPEs concentrations in subtropical and tropical oceans are comparable, while those in the northern and southern oceans are of similar magnitudes [54]. Notably, OPEs concentrations along the coast of the Northern Hemisphere exceed those of the Southern Hemisphere. For instance, the concentration from the Sea of Japan to the North Pole ranges from 230 to 2900 pg m−3, which is higher than the concentrations observed in aerosol samples from East Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Antarctic, which range from 120 to 1700 pg m−3 [49]. Generally, OPEs concentrations detected in aerosol samples from coastal stations are greater than those found in open ocean samples [54,77] (Figure 2). For example, the concentration of OPEs in aerosol samples collected along the Yellow and Bohai Seas in 2020 ranged from 426 to 3933 pg m−3 [81], whereas concentrations in marine aerosol samples from the Yellow and Bohai Seas and Beihuangcheng Island during 2015–2016 were notably lower, ranging from 44 to 520 pg m−3 [37].

Figure 2.

OPEs in the ocean air (adapted from [10]).

The distribution of OPEs in the atmosphere exhibits several notable characteristics. Chlorinated OPEs are the most abundant compounds, with TCEP and TCPP concentrations surpassing those of TDCP [74,82]. Additionally, the levels of TPPO and TiBP species are relatively high in urban areas along the Bohai Sea and the Mediterranean Sea, primarily due to local pollution sources associated with OPEs [40]. One reason for the elevated presence of chlorinated OPEs in the atmosphere compared to other OPE congeners is their longer photodegradation time [18]. The proportion of OPE homologues in the atmosphere of various bordering countries correlates with the usage of these compounds within those nations. For instance, European countries have prohibited the use of TCEP as an additive, resulting in the detection of higher levels of TCPP than TCEP in nearby marine environments [65]. Conversely, TCEP remains in use in Asian markets, where its concentration in coastal atmospheres exceeds that of TCPP [49,82]. Furthermore, the increasing TCPP/TCEP ratio in Asian waters indicates a rise in TCPP usage within these countries [74].

3.2. OPEs in Seawater

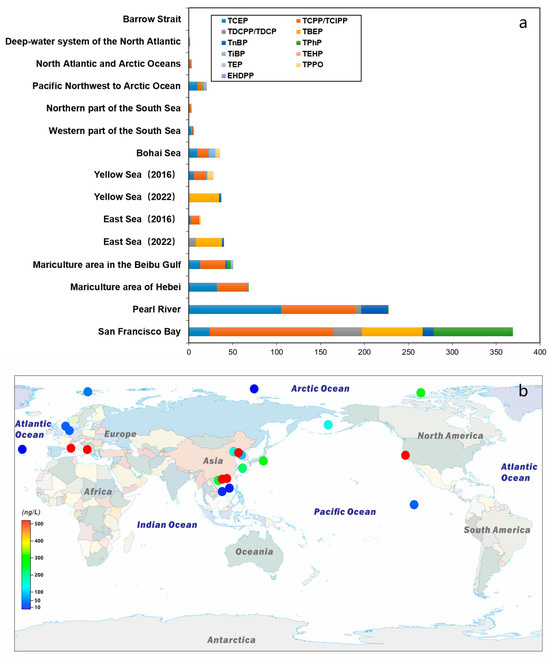

Currently, with the increasing emphasis on marine environmental research, surveys of OPEs in seawater samples have been conducted to varying extents in different worldwide regions [46,83] (Figure 3 and Table 2). The findings indicate that OPEs have been detected in seawater samples from major oceanic areas, highlighting the long-distance migration potential of these compounds [30,48]. The concentrations of OPEs identified in various seawater environments exhibit significant variability, ranging from a few to several hundred ng L−1 [25,84]. A recent review article synthesized the distribution of OPEs across key sea areas globally [30,85]. Notably, by analyzing coastal survey data from seven European countries [86], it was determined that OPEs were present in all ocean surface water samples collected from these regions. The total concentration range was found to be between 0.43 and 867 ng L−1 [48,87], with elevated levels primarily observed near urban areas in the UK and Portugal.

Figure 3.

Concentrations of OPEs (ng/L) in seawater. (a) Concentrations of different OPEs compounds. (b) The total amount of OPEs. Data sources are provided in Table 2.

Seawater survey data from the western Pacific Ocean indicate that the concentration range of OPEs is between 3.02 and 48.4 ng L−1 [88]. Similarly, studies of water samples from various coastal areas in China and Japan have demonstrated the widespread distribution of these compounds in these maritime regions. Samples collected in 2016 from China’s Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, and East China Sea revealed concentration ranges of 19.7 to 100 ng L−1, 9.26 to 86.8 ng L−1, and 8.81 to 55.7 ng L−1, respectively [10,12,34,84,89]. Additionally, the distribution range reported by [90] for the South China Sea is 1 to 147 ng L−1, while the concentration range for Tokyo Bay in the Sea of Japan is 107 to 284 ng L−1.

Chlorinated OPEs have also been detected in higher latitude seas [30], including Arctic waters, with concentrations ranging from approximately 0.9 to 17 ng L−1 [46,91]. Similarly, the concentrations of ∑8OPEs in the North Atlantic and Arctic were found to range from 0.35 to 8.4 ng L−1 [56]. In studies conducted near the northwest Pacific and Arctic waters, the distribution of OPEs concentrations in samples varied from 8.47 to 143.45 ng L−1 [57]; however, only one sample reached 143.45 ng L−1, while the values of the remaining samples were all below 50 ng L−1. Unfortunately, the article did not provide an explanation for this unusually high value.

It is important to note that the primary compounds detected in seawater are TCPP, TCEP, and TDCPP. This distribution characteristic can be attributed to the extensive use of these three chlorinated OPEs. Furthermore, their stable branched chain structures and high resistance to degradation also contribute to their persistence in seawater [85].

The factors influencing the distribution characteristics of OPEs in seawater are complex. Comparative research indicates that the concentration of OPEs in seawater samples varies across different sampling times, depths, and locations. Research conducted in China’s Bohai Sea, South China Sea, and various other marine regions has demonstrated that the concentration of OPEs in seawater exhibits a gradient distribution from estuarine to coastal and pelagic zones [10]. As the distance from shore increases, the concentration of OPEs gradually diminishes [24,92]. These findings highlight the influence of sampling location on the distribution patterns of OPEs.

A comparison of data from the Yellow Sea in 2015 and 2019 revealed notable changes in OPE concentrations across different years, with varying patterns observed among different compounds [12]. For instance, TCPP exhibited a significant increase, while TCEP showed no substantial change. The rising use of TCPP as a substitute for TCEP may explain these trends. More importantly, a comparison of the total amounts of chlorinated OPEs in the Yellow Sea, Bohai Sea, and other seawater bodies over the past five years indicates an exponential increase [60]. These data illustrate that chlorinated OPEs can persist stably in the ocean for extended periods. Conversely, they also indicate an annual increase in emissions from adjacent coastal areas.

Table 2.

Occurrence of OPEs in seawater (average value, ng/L).

Table 2.

Occurrence of OPEs in seawater (average value, ng/L).

| Country/Region | Location | Sampling Year | TCEP | TCPP/TCIPP | TDCPP/TDCP | TBEP | TnBP | TPhP | TiBP | TEHP | TEP | TPPO | EHDPP | ΣOPEs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Mariculture area in the Beibu Gulf | 2015 | 13.1 (5.21–82.1) | 28.2 (13.9–92.5) | 0.49 (0.19–1.68) | na | 1.53 (0.69–4.8) | 3.99 (1.28–7.76) | 2.74 (0.63–5.68) | 0.14 (0.03–0.36) | na | na | na | 68.7 (32.9–227) | [93] |

| China | Mariculture area of Hebei | 2017 | 31.97 (4.17–74.76) | 34.39 (14.49–69.68) | 1.04 (0.52–3.01) | nd | na | 0.65 (0.11–3.22) | na | na | na | na | na | 74.5 (40.40–154.05) | [34] |

| Norway | Ny-Ålesund region | 2016 | 5.58 (nd–60.84) | 2.45 (nd–15.03) | 0.34 (nd–0.99) | nd | na | 0.25 (nd–0.89) | na | 0.79 (nd~11.37) | na | na | na | 13.4 (0.66–61.64) | [34] |

| USA | San Francisco Bay | 2013 | 7.4–300 | 46–2900 | 14–450 | 24–1000 | 7.8–43 | 41–360 | na | nd–11 | nd–3.2 | na | nd–2.3 | 170–5100 | [83] |

| Germany | North Sea | 2010 | na | 3–28 | na | nd–6 | na | na | 0.5–5 | na | 0.7–7 | nd–12 | na | 5–50 | [48] |

| Ocean | Pacific Northwest to Arctic Ocean | 2018 | 9.9 (1.10–86.19) | 3.81 (0.76–20.87) | 1.25 (nd–4.53) | 0.32 (nd–7.70) | 0.02 (nd–0.33) | 0.88 (0.26–2.64) | 4.07 (2.37–6.00) | 0.37 (0.0004–1.55) | na | na | na | 8.47–143.45 | [57] |

| Ocean | Deep-water system of the North Atlantic | 2014–2015 | 0.08 (nd–0.39) | 0.04 (nd–0.05) | 0.004 (0.001–0.007) | na | 0.01 (nd–0.06) | 0.60 (nd~1.2) | na | 0.61(nd–1.5) | na | na | 0.21(0.06–0.33) | 0.0063–0.44 | [46] |

| Canada | Barrow Strait | 2014–2015 | 0.001 (0.0001–0.002) | 0.003 (0.0001–0.006) | 0.00006 (nd–0.0001) | na | 0.0004 (0.0002–0.0006) | 0.0006 (0.0004–0.0008) | na | 0.00002 (nd–0.00005) | na | na | 0.0003 (nd–0.0006) | - | [46] |

| Ocean | North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans | 2014 | 0.70 (nd–2.40) | 1.84 (0.28–5.77) | 0.007 (nd–0.04) | na | 0.12 (nd–0.41) | nd | 0.26 (0.04–0.64) | 0.006 (nd–0.07) | na | na | na | 2.94 (0.34–8.59) | [1] |

| China | Bohai Sea | 2016 | 9.56 (6.06–19.8) | 11.4 (3.97–26.7) | 2.03 (nd–5.16) | na | nd–37.2 | 0.15 (nd–3.28) | 6.96 (1.97–27.4) | na | na | 5.16 (1.86–26.6) | na | 39.1 (19.7–100) | [15] |

| Yellow Sea | 5.84 (1.24–16.9) | 13.1 (5.17–35.6) | 2.07 (nd–8.13) | na | nd–26.5 | 0.14 (nd–0.76) | nd–9.64 | na | na | 6.93 (1.18–43.5) | na | 30.7 (9.26–86.8) | |||

| East Sea | 1.93 (0.59–12.4) | 9.63 (5.61–29.6) | 0.51 (nd–4.92) | na | nd | 0.11 (nd–1.95) | nd | na | na | 1.63 (nd–19.1) | na | 15.1 (8.81–55.7) | |||

| China | Yellow Sea | 2022 | na | na | nd | 34.51 (nd–334.88) | 2.61 (nd–9.36) | nd | na | na | na | na | na | 22.94 (nd–497.40) | [89] |

| East Sea | na | na | 7.73(nd–9.84) | 30.15 (nd–124.82) | 2.12 (nd–22.74) | nd | na | na | na | na | na | 8.11 (nd–126.49) | |||

| China | Yellow Sea and East Sea | 2023 | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | 66.73 (12.72–202.60) | [12] |

| China | Pearl River | 2022 | 169.4 ± 157.1 (39.3–414.9) | 105.9 ± 78.6 (37.8–260.9) | 7.4 ± 3.9 (1.2–11.6) | na | 50.3 ± 57.7 (13.6–179.0) | 1.8 ± 1.5 (0.7–4.2) | na | na | na | na | na | 361.8 ± 283.3 (117.5–854.8) | [10] |

| Northern part of the South Sea | 2.0 ± 1.9 (0.2–5.4) | 2.7 ± 3.2 (0.3–10.3) | 0.06 ± 0.04 (0.002–0.1) | na | na | 0.09 ± 0.07 (0.01–0.2) | na | 0.08 ± 0.05 (0.01–0.2) | 0.05 ± 0.02 (0.01–0.09) | 6.7 ± 5.2 (1.3–17.6) | |||||

| Western part of the South Sea | 4.2 ± 4.7 (0.8–22.6) | 2.4 ± 1.7 (0.4–6.2) | 0.06 ± 0.08 (nd–0.3) | na | 0.5 ± 0.5 (0.1–2.2) | 0.06 ± 0.03 (0.01–0.10) | na | na | na | na | na | 7.6 ± 5.5 (2.3–24.4) |

na: not analyzed; nd: not detected.

In addition, Zhang Lutao [12] compared the distribution of OPEs in seawater samples collected at various depths in the Yellow Sea. The results highlighted differences in the concentration distribution of OPEs among surface seawater, 20 m deep seawater, and bottom seawater samples, indicating the influence of sampling depth.

To fully understand the distribution characteristics of OPEs in seawater, it is essential to conduct comparative studies under varying conditions. Such studies will provide a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the distribution, physical and chemical properties, as well as the migration and transformation mechanisms of these compounds.

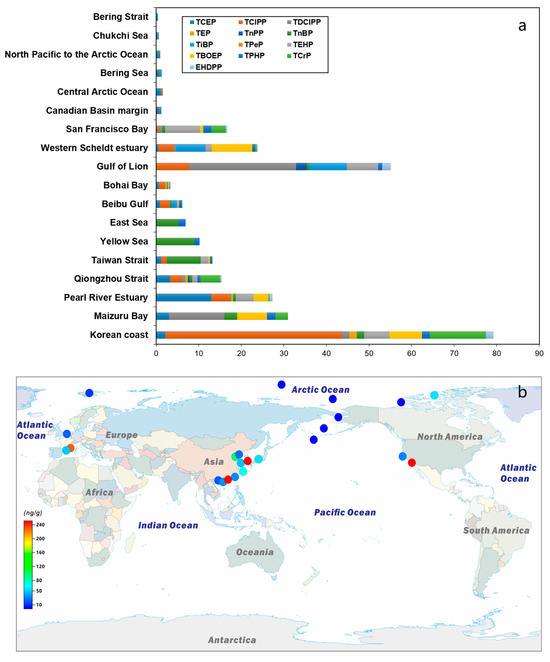

3.3. OPEs in Marine Sediment

Currently, there is a limited amount of research data on marine sediments, primarily focused on marginal seas near inland areas, with significantly less data available from the open ocean. Published data indicate that the total concentration of OPEs varies from pg g−1 dw to ng g−1 dw [10,30] and the following distribution characteristics are present (Figure 4 and Table 3). Furthermore, a trend of increasing OPEs concentrations in marine sediments is observed, progressing from polar regions to estuaries. For instance, the concentrations in the Bering Strait and the Arctic Ocean are reported to be 0.29–2.01 ng/L and 0.32–4.66 ng/L [63], respectively. The distribution ranges of Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea are 0.08–1.86 ng/L and 0.21–4.55 ng/L [94]. In contrast, the Beibu Gulf marine aquaculture area exhibits a distribution range of 4.35–22.1 ng/L. Additionally, the distribution ranges in the Taiwan Strait and Qiongzhou Strait are 5.26–34.23 ng/L and 0.99–36.2 ng/L [95,96]. And the available research data reveal several consistent characteristics.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of OPEs (ng/g) in marine sediments. (a) Concentrations of different OPEs compounds. (b) The total amount of OPEs. Data sources are provided in Table 3.

- (1)

- Chlorinated OPEs, particularly TCEP and TCIPP, are the most abundant components in sediments located closer to the continent [10,30]. This prevalence is attributed to their widespread use and low degradation rates. Furthermore, due to their relatively high hydrophobicity, TEHP (lgKow 9.5) and TCrP (lgKow 5.1) were also identified as dominant components of OPEs in the sediments [94,95].

- (2)

- The levels of OPEs in sediments tend to be higher in areas closer to land and more densely populated regions [30]. In contrast, the concentrations of OPEs in open-ocean sediment are significantly lower than those found in marginal-sea sediments [97]. For instance, in the Bohai Sea, decreasing levels of ΣOPEs have been reported in sediment as the distance from shore increases: Laizhou Bay (6.6–100 ng g−1 d.w.) > Bohai Bay (1.7–29 ng g−1 d.w.) > Bohai Sea (0.20–4.6 ng g−1 d.w.) [98,99]. This pattern indicates that the primary sources of OPEs in marine sediments are likely terrestrial contributions. Conversely, the concentrations of OPEs in open-sea sediments are significantly lower, such as those from the North Pacific to the Arctic Ocean, range from 0.2 to 4.7 ng g−1 d.w [63].

- (3)

- Differences in the content of OPEs in sediments can be attributed to varying depths. Investigating the concentration of organic pollutants in sedimentary columns at different depths is essential for understanding the pollution history across different time periods [100]. Several factors are currently recognized as influencing the vertical distribution of OPEs, including variations in regional production, usage, and emission intensity within the current year [99,101]. Additionally, differences in the adsorption and distribution behavior of various compounds in water and sediments arise from their distinct physical and chemical properties, as well as the transformation and degradation of chemical compounds during post-deposition. Nonetheless, there remains a significant gap in systematic research within this field, leading to an insufficiently comprehensive summary of existing patterns. Therefore, further investigation is warranted.

Table 3.

Occurrence of OPEs in ocean surface sediment (average value, ng/g dw).

Table 3.

Occurrence of OPEs in ocean surface sediment (average value, ng/g dw).

| Country/ Region | Location | Sampling Year | Sampling Number | TCEP | TCIPP | TDCIPP | TEP | TnPP | TnBP | TiBP | TPeP | TEHP | TBOEP | TPHP | TCrP | EHDPP | ΣOPFRs (Range) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Beibu Gulf | 2015 | 12 | 0.880 | 2.35 | 0.090 | 0.210 | 1.33 | 0.360 | 0.160 | 0.690 | 0.040 | 7.56 (4.35–22.1) | [63] | ||||

| China | Taiwan Strait | 2016 | 32 | 1.10 | 1.31 | 0.124 | nd | nd | 7.92 | 1.82 | 0.343 | 0.549 | 0.042 | 12.8 (5.26–34.2) | [102] | |||

| China | Coast of Hainan Island (Qiongzhou Strait) | 2015 | 20 | 3.27 | 2.69 | 0.870 | 0.640 | 0.380 | 0.660 | 1.15 | nd | 0.760 | 4.67 | 0.310 | 15.9 (0.990–36.2) | [30] | ||

| Coast of Hainan Island (Near-shore) | 14 | 1.62 | 3.28 | 0.550 | 0.790 | 0.230 | 1.04 | 0.850 | nd | 0.510 | 7.95 | 0.480 | 16.4 (nd–60.0) | |||||

| coast of Hainan Island (Off-shore) | 9 | 1.60 | 2.72 | 0.640 | 1.02 | 0.880 | 1.34 | 0.870 | nd | 0.580 | 6.05 | 0.410 | 15.1 (2.40–28.4) | |||||

| China | Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea | 2017–2018 | 15 | 7.40 | 16.3 | 20.1 | 15.0 | 9.70 | 33.8 | 11.0 | 26.0 | 32.1 | 68.2 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 18.4 | 304.2 ± 16.2 | [98] |

| China | Bohai Bay, Bohai Sea | 2014–2017 | 12 | 0.637 | 1.48 | 0.055 | 0.346 | nd | 0.184 | 0.232 | 0.189 | 0.082 | 0.091 | 0.068 | 3.79 (1.66–28.7) | [30] | ||

| China | Bohai Yellow Seas | 2010 | 44 43 | 0.202 0.111 | 0.113 0.076 | 0.018 0.011 | 0.024 0.010 | 0.085 0.016 | 0.002 0.002 | 0.375 0.080 | 0.053 0.036 | 1.14 (0.205–4.55) 0.411 (0.083–1.86) | [103] | |||||

| China | Pearl River Estuary | 2010 | 10 | 13.0 | 4.30 | 0.340 | 0.400 | 0.040 | 0.600 | 4.20 | 3.50 | nd-16.0 | 0.300 | 0.620 | 34.0 (12.0–66.0) | [104] | ||

| China | Yellow Sea | 2022 | 66 | 9.02 | 1.16 | 5.28 (nd–47.85) | [89] | |||||||||||

| East Sea | 5.31 | 1.60 | 6.10 (nd–66.50) | |||||||||||||||

| Japan | Maizuru Bay | 2009 | 13 | 3.00 | 13.0 | nd | 3.00 | 7.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | <0.500–56.0 | [48] | ||||||

| Korea | Korean coast | 2016 | 50 | 2.16 | 41.5 | 1.78 | 1.70 | 1.73 | 5.95 | 7.63 | 1.83 | 1.33/3.94/7.92 | 1.78 | 71.0 (2.18–347) | [40] | |||

| Netherlands | Western Scheldt estuary | 2008 | 3 | 0.500 | 3.60 | 0.600 | 6.90 | 1.50 | 9.50 | 0.600 | 0.400 | 0.300 | - | [105] | ||||

| USA | San Francisco Bay | 2014 | 10 | nd | 0.540 | 0.960 | nd | - | 0.570 | 8.20 | 0.810 | 1.90 | 3.40 | 0.280 | 23.0 | [47] | ||

| Northwest Mediterranean Sea | Gulf of Lion | 2018 | 12 | 7.78 | 25.05 | 2.55 | 0.59 | 8.85 | 7.36 | 0.92 | 1.97 | 54 (4–227) | [43] | |||||

| Arctic | Ny-Ålesund | 2017 | 9 | <0.02–2.88 | 0.01–7.41 | <0.02–0.73 | <0.02–2.64 | <0.01–0.37 | <0.01–0.64 | <0.01–0.87 | 2.44 (0.01–14.94) | [106] | ||||||

| Ocean | North Pacific to the Arctic Ocean | 2010 | 30 | 0.536 | 0.068 | 0.014 | 0.068 | 0.162 | 0.007 | 0.023 | 0.878 (0.159–4.66) | [107] | ||||||

| Bering Sea | 4 | 0.655 | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.114 | 0.315 | 0.002 | 0.030 | 1.21 | |||||||||

| Bering Strait | 4 | 0.109 | 0.009 | nd | 0.060 | 0.170 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.350 | |||||||||

| Chukchi Sea | 12 | 0.281 | 0.033 | 0.006 | 0.052 | 0.126 | 0.002 | 0.023 | 0.524 | |||||||||

| Canadian Basin margin | 3 | 0.717 | 0.114 | 0.037 | 0.095 | 0.177 | 0.020 | 0.028 | 1.19 | |||||||||

| Central Arctic Ocean | 7 | 1.07 | 0.136 | 0.028 | 0.061 | 0.123 | 0.015 | 0.028 | 1.46 |

nd: not detected; a median value; b TmCP/ToCP/TpCP.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

As a result of their widespread application, OPEs have been detected at different concentration levels in marine environments globally, and OPEs’ persistence allows these compounds to exert a lasting and extensive impact on the environment and ecosystem. Consequently, it is urgent and important to investigate the distribution, migration, fate, and other related issues concerning these compounds. Based on the comprehensive analysis in this article, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

- OPEs in the marine environment primarily originate from terrestrial sources and in situ releases. The transplantation of OPEs are complex, including river input, LRAT, air–water exchange, and dry and wet deposition. Additionally, OPEs can be remobilized by snow and ice melting, and they can also be transported in ocean via currents and biological vectors (e.g., food chains). Furthermore, OPEs are found to be degraded in the environment primarily through hydrolysis, photolysis, and biodegradation.

- (2)

- The distributions of OPEs in marine environments have been intensively investigated. OPEs have been detected in the air of major oceans, with concentrations in global marine aerosol samples ranging from pg m−3 to several ng m−3. Notably, chlorinated OPEs are the most abundant compounds identified. Furthermore, OPEs have been found in seawater samples from various regions, confirming their long-distance migration experience. The concentrations of OPEs identified in seawater exhibit significant variability, ranging from a few to several hundred ng L−1. The primary compounds detected in seawater are TCPP, TCEP, and TDCPP. The data published indicate that the total concentration of OPEs in marine sediments varies from pg g−1 dw to ng g−1 dw. Furthermore, an increasing trend of OPE concentrations in marine sediments is observed from polar regions to estuaries. Chlorinated OPEs, particularly TCEP and TCIPP, are identified as the most abundant components in sediments located closer to the continent. The concentration levels of OPEs in sediments tend to be higher in areas closer to land and more densely populated regions.

Future studies might be conducted in the following directions for the purposes of ecological conservation and to deepen our understanding of marine biogeochemical cycles:

- (1)

- Systematic investigations of OPEs in different marine environments: It is essential to carry out systematic comparative studies, including analyses of air, seawater, and sediments within the same area, to advance understanding of the migration and transformation processes of OPEs in marine systems. Comparisons should also be made to understand the influences of environmental factors on the distributions of OPEs. To clarify the mechanisms of their environmental distribution differences, the structural details of OPEs should be specified.

- (2)

- Development of predictive models: Establishing a machine learning framework, which integrates key physicochemical parameters (e.g., lgKow, pKa, and hydrolysis rate constants), oceanic environmental variables (e.g., ocean current dynamics and meteorological conditions), and annual organic phosphate emissions (e.g., flux, geographic distribution, and chemical composition), could aid in the precise prediction of the fate of OPEs in marine systems.

Author Contributions

X.X.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft, Funding acquisition. M.P.: Visualization, Writing—review and editing. Y.W.: Writing—review and editing. B.S.: Resources, Project administration. P.F.: Writing—review and editing. J.Y.: Visualization. H.L.: Conceptualization, Writing-review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41702159) and the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences Basal Research Fund (Grant Nos. CSJ-2024-05 and CSJ-2023-08).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.; An, C.; Elektorowicz, M.; Tian, X. Sources, Behaviors, Transformations, and Environmental Risks of Organophosphate Esters in the Coastal Environment: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 180, 113779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, L.; Waniek, J.J.; Pohlmann, T.; Mi, W.; Xu, W. Organophosphate Esters in Air and Seawater of the South China Sea: Spatial Distribution, Transport, and Air–Sea Exchange. Environ. Health 2023, 1, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhuang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W. A Review of Organophosphate Esters in Aquatic Environments: Levels, Distribution, and Human Exposure. Water 2023, 15, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Tao, M.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, M.; Sun, J.; Jia, S.; Liu, C.-H. Occurrence, Spatial Distribution and Risk Assessment of Organophosphate Esters in Surface Water from the Lower Yangtze River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Stubbings, W.A.; Abdallah, M.A.-E.; Cline-Cole, R.; Harrad, S. Formal Waste Treatment Facilities as a Source of Halogenated Flame Retardants and Organophosphate Esters to the Environment: A Critical Review with Particular Focus on Outdoor Air and Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. A Review of Organophosphate Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in the Environment: Analysis, Occurrence and Risk Assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Bao, L.; Wu, C.; Liu, L.; Wong, C.S.; Zeng, E.Y. Organophosphate Flame Retardants Emitted from Thermal Treatment and Open Burning of E-Waste. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 367, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Veen, I.; De Boer, J. Phosphorus Flame Retardants: Properties, Production, Environmental Occurrence, Toxicity and Analysis. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1119–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, M.; Shi, Y.; Na, G.; Cai, Y. A Review of Organophosphate Esters in Indoor Dust, Air, Hand Wipes and Silicone Wristbands: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G. Organophosphate Esters in Marine Environment: Sources, Transport and Air-Sea Interface Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Su, G.; Letcher, R.J.; Yu, H. Organophosphate Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Aqueous Solution: pH-Dependent Hydrolysis, Kinetics, and Pathways. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 8103–8111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Pollution Characteristics and Ecological Risks of Emerging Pollutant Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in Typicalareas of the Yellow Sea and East China Sea. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoshi, Y.; Fukunaga, I.; Itoh, H. Distribution of Organophosphoric Acid Triesters between Water and Sediment at a Sea-Based Solid Waste Disposal Site. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 1999, 1, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Wen, J.; Zeng, F.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, Z. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphate Esters in Urban Soils of the Subtropical City, Guangzhou, China. Chemosphere 2017, 175, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Tang, J.; Guo, X.; Guo, C.; Li, F.; Wu, H. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in the Bohai, Yellow and East China Seas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, K.; Corcoran, M.B.; Hosseini, S.; Bonina, S.M.C.; Rockne, K.J.; Sturchio, N.C.; et al. Organophosphate Esters in Sediment of the Great Lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 1441–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, K.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, X.; Yu, Z. Organophosphate Esters in the Water, Sediments, Surface Soils, and Tree Bark Surrounding a Manufacturing Plant in North China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.-L.; Li, D.-Q.; Zhuo, M.-N.; Liao, Y.-S.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Guo, T.-L.; Li, J.-J.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Liang, Z.-Q. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers: Sources, Occurrence, Toxicity and Human Exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 196, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Accumulation, Distribution and Transformation Oforganophosphate Flame Retardants in Fsh and Their Underlying Mechanism. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Shi, C.; Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G. Similarities and Differences among the Responses to Three Chlorinated Organophosphate Esters in Earthworm: Evidences from Biomarkers, Transcriptomics and Metabolomics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokwe, T.B.; Abafe, O.A.; Mbelu, S.P.; Okonkwo, J.O.; Sibali, L.L. A Review of Sources, Fate, Levels, Toxicity, Exposure and Transformations of Organophosphorus Flame-Retardants and Plasticizers in the Environment. Emerg. Contam. 2020, 6, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cai, Y. Occurrence, Distribution and Seasonal Variation of Organophosphate Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Urban Surface Water in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 209, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A.; Behl, M.; Birnbaum, L.S.; Diamond, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Singla, V.; Sipes, N.S.; Stapleton, H.M.; Venier, M. Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants: Are They a Regrettable Substitution for Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers? Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 638–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tang, J.; Xie, Z.; Mi, W.; Chen, Y.; Wolschke, H.; Tian, C.; Pan, X.; Luo, Y.; Ebinghaus, R. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in 40 Rivers Draining into the Bohai Sea, North China. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 198, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Fauvelle, V.; Ourgaud, M.; Sempéré, R. Occurrence of Organic Plastic Additives in Surface Waters of the Rhône River (France). Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.; Fauvelle, V.; Ody, A.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Jouanno, J.; Changeux, T.; Thibaut, T.; Sempéré, R. The Amazon River: A Major Source of Organic Plastic Additives to the Tropical North Atlantic? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7513–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ding, N.; Wang, T.; Tian, M.; Fan, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, S.-J.; Mai, B.-X. Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in Fine Particulate Matter (PM2.5) in Urban, e-Waste, and Background Regions of South China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.V.; Diamond, M.L.; Venier, M.; Stubbings, W.A.; Romanak, K.; Bajard, L.; Melymuk, L.; Jantunen, L.M.; Arrandale, V.H. Exposure of Canadian Electronic Waste Dismantlers to Flame Retardants. Environ. Int. 2019, 129, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Peris, A.; Rifat, M.R.; Ahmed, S.I.; Aich, N.; Nguyen, L.V.; Urík, J.; Eljarrat, E.; Vrana, B.; Jantunen, L.M.; et al. Measuring Exposure of E-Waste Dismantlers in Dhaka Bangladesh to Organophosphate Esters and Halogenated Flame Retardants Using Silicone Wristbands and T-Shirts. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Kallenborn, R.; Liao, C.; Mi, W.; Lohmann, R.; Vila-Costa, M.; Dachs, J. Organophosphate Ester Pollution in the Oceans. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachs, J.; Lohmann, R.; Ockenden, W.A.; Méjanelle, L.; Eisenreich, S.J.; Jones, K.C. Oceanic Biogeochemical Controls on Global Dynamics of Persistent Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 4229–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paluselli, A.; Fauvelle, V.; Galgani, F.; Sempéré, R. Phthalate Release from Plastic Fragments and Degradation in Seawater. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauvelle, V.; Garel, M.; Tamburini, C.; Nerini, D.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Schmidt, N.; Paluselli, A.; Fahs, A.; Papillon, L.; Booth, A.M.; et al. Organic Additive Release from Plastic to Seawater Is Lower under Deep-Sea Conditions. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. Distribution Characteristics and Bioaccumulation of Organophosphate esters in the Typical Marine Area. Master’s Thesis, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Bin, L.; Cui, J.; Nyobe, D.; Li, P.; Huang, S.; Fu, F.; Tang, B. Tracing the Occurrence of Organophosphate Ester along the River Flow Path and Textile Wastewater Treatment Processes by Using Dissolved Organic Matters as an Indicator. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; He, L.; Cao, S.; Ma, S.; Yu, Z.; Gui, H.; Sheng, G.; Fu, J. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphate Flame Retardants/Plasticizers in Wastewater Treatment Plant Sludges from the Pearl River Delta, China. Enviro Toxic Chem. 2014, 33, 1720–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Tang, J.; Mi, W.; Tian, C.; Emeis, K.-C.; Ebinghaus, R.; Xie, Z. Spatial Distribution and Seasonal Variation of Organophosphate Esters in Air above the Bohai and Yellow Seas, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, P.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, G. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphate Esters in the Air and Soils of Ny-Ålesund and London Island, Svalbard, Arctic. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Taylor, A.R.; Cryder, Z.; Schlenk, D.; Gan, J. Inference of Organophosphate Ester Emission History from Marine Sediment Cores Impacted by Wastewater Effluents. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 8767–8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Jiménez, J.; Sempéré, R. Atmospheric Particle-Bound Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in a North African Mediterranean Coastal City (Bizerte, Tunisia). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Du, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y. A Review of a Class of Emerging Contaminants: The Classification, Distribution, Intensity of Consumption, Synthesis Routes, Environmental Effects and Expectation of Pollution Abatement to Organophosphate Flame Retardants (OPFRs). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, S.; Chen, C.; Rogers, M.J.; Ramaswamy, R.; He, J. Insights into the Occurrence, Fate, and Impacts of Halogenated Flame Retardants in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 4205–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sühring, R.; Diamond, M.L.; Bernstein, S.; Adams, J.K.; Schuster, J.K.; Fernie, K.; Elliott, K.; Stern, G.; Jantunen, L.M. Organophosphate Esters in the Canadian Arctic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Soltwedel, T.; Bauerfeind, E.; Adelman, D.A.; Lohmann, R. Depth Profiles of Persistent Organic Pollutants in the North and Tropical Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6172–6179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wei, G.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Su, L.; Qin, W. Aqueous OH Radical Reaction Rate Constants for Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers: Experimental and Modeling Studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2790–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, C.A.; De Silva, A.O.; Sun, C.; Cabrerizo, A.; Adelman, D.; Soltwedel, T.; Bauerfeind, E.; Muir, D.C.G.; Lohmann, R. Dissolved Organophosphate Esters and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers in Remote Marine Environments: Arctic Surface Water Distributions and Net Transport through Fram Strait. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 6208–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, T.F.M.; Truong, J.W.; Jantunen, L.M.; Helm, P.A.; Diamond, M.L. Organophosphate Ester Transport, Fate, and Emissions in Toronto, Canada, Estimated Using an Updated Multimedia Urban Model. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 12465–12474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollmann, U.E.; Möller, A.; Xie, Z.; Ebinghaus, R.; Einax, J.W. Occurrence and Fate of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Coastal and Marine Surface Waters. Water Res. 2012, 46, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, A.; Sturm, R.; Xie, Z.; Cai, M.; He, J.; Ebinghaus, R. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Airborne Particles over the Northern Pacific and Indian Ocean toward the Polar Regions: Evidence for Global Occurrence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3127–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liggio, J.; Harner, T.; Jantunen, L.; Shoeib, M.; Li, S.-M. Heterogeneous OH Initiated Oxidation: A Possible Explanation for the Persistence of Organophosphate Flame Retardants in Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Yang, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Yang, G. Review of organophosphate esters in oceans and atmospheres. Mar. Sci. 2020, 44, 154–165, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Regnery, J.; Püttmann, W. Seasonal Fluctuations of Organophosphate Concentrations in Precipitation and Storm Water Runoff. Chemosphere 2010, 78, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sühring, R.; Serodio, D.; Bonnell, M.; Sundin, N.; Diamond, M.L. Novel Flame Retardants: Estimating the Physical–Chemical Properties and Environmental Fate of 94 Halogenated and Organophosphate PBDE Replacements. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 2401–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Jiménez, J.; González-Gaya, B.; Pizarro, M.; Casal, P.; Pizarro-Álvarez, C.; Dachs, J. Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in the Global Oceanic Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 12831–12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, E.; Jaward, F.M.; Lohmann, R.; Jones, K.C.; Simó, R.; Dachs, J. Atmospheric Dry Deposition of Persistent Organic Pollutants to the Atlantic and Inferences for the Global Oceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 5505–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xie, Z.; Mi, W.; Lai, S.; Tian, C.; Emeis, K.-C.; Ebinghaus, R. Organophosphate Esters in Air, Snow and Seawater in the North Atlantic and the Arctic. Environ. Sci. 2017, 51, 6887–6896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, G.; Hou, C.; Li, R.; Shi, Y.; Gao, H.; Jin, S.; Gao, Y.; Jiao, L.; Cai, Y. Occurrence, Distribution, Air-Seawater Exchange and Atmospheric Deposition of Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) from the Northwestern Pacific to the Arctic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 157, 111243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnery, J.; Püttmann, W. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Rain and Snow from Middle Germany. CLEAN Soil Air Water 2009, 37, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, U.-J.; Kannan, K. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphate Flame Retardants/Plasticizers in Surface Waters, Tap Water, and Rainwater: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 5625–5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Gan, Z.; Qu, B.; Chen, S.; Dai, Y.; Bao, X. Temporal and Seasonal Variation and Ecological Risk Evaluation of Flame Retardants in Seawater and Sediments from Bohai Bay near Tianjin, China during 2014 to 2017. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and Fragmentation of Plastic Debris in Global Environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Xie, Z.; Blais, J.M.; Zhang, P.; Li, M.; Yang, C.; Huang, W.; Ding, R.; Sun, L. Organophosphorus Esters in the Oceans and Possible Relation with Ocean Gyres. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 180, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xie, Z.; Lohmann, R.; Mi, W.; Gao, G. Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Ocean Sediments from the North Pacific to the Arctic Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3809–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; He, Z.; Yuan, J.; Ma, X.; Du, J.; Yao, Z.; Wang, W. Comprehensive Evaluation of Organophosphate Ester Contamination in Surface Water and Sediment of the Bohai Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 163, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, A.; Xie, Z.; Caba, A.; Sturm, R.; Ebinghaus, R. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in the Atmosphere of the North Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2011, 159, 3660–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casal, P.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Pizarro, M.; Katsoyiannis, A.; Dachs, J. Seasonal Soil/Snow-Air Exchange of Semivolatile Organic Pollutants at a Coastal Arctic Site (Tromsø, 69°N). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Mechanisms Study on Characterizing ChemicalOxidation and Biodegradation of Organophosphorus Ester Flame Retardants. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, P.W.C.; Bunton, C.A.; Llewellyn, D.R.; Vernon, C.A.; Welch, V.A. 523. The Reactions of Organic Phosphates. Part V. The Hydrolysis of Triphenyl and Trimethyl Phosphates. J. Chem. Soc. 1961, 8, 2670–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Kim, E.; Strathmann, T.J. Mineral- and Base-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Organophosphate Flame Retardants: Potential Major Fate-Controlling Sink in Soil and Aquatic Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, H.; Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Wang, L.; Gao, N.; Ke, J. Degradation of Tris(2-Chloroethyl) Phosphate by Ultraviolet-Persulfate: Kinetics, Pathway and Intermediate Impact on Proteome of Escherichia Coli. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chládková, B.; Lechtenfeld, O.J.; Lian, S.; Schindelka, J.; Herrmann, H.; Richnow, H.H. Characterizing Chemical Transformation of Organophosphorus Compounds by 13C and 2H Stable Isotope Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristale, J.; Dantas, R.F.; De Luca, A.; Sans, C.; Esplugas, S.; Lacorte, S. Role of Oxygen and DOM in Sunlight Induced Photodegradation of Organophosphorous Flame Retardants in River Water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeger, V.W.; Hicks, O.; Kaley, R.G.; Michael, P.R.; Mieure, J.P.; Tucker, E.S. Environmental Fate of Selected Phosphate Esters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1979, 13, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, W.; Mi, W.; Yan, W.; Guo, T.; Zhou, F.; Miao, L.; Xie, Z. Atmospheric Deposition, Seasonal Variation, and Long-Range Transport of Organophosphate Esters on Yongxing Island, South China Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemergut, D.R.; Costello, E.K.; Hamady, M.; Lozupone, C.; Jiang, L.; Schmidt, S.K.; Fierer, N.; Townsend, A.R.; Cleveland, C.C.; Stanish, L.; et al. Global Patterns in the Biogeography of Bacterial Taxa. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.; Wenley, J.; Lockwood, S.; Twigg, I.; Currie, K.; Herndl, G.J.; Hepburn, C.D.; Baltar, F. Relative Importance of Phosphodiesterase vs. Phosphomonoesterase (Alkaline Phosphatase) Activities for Dissolved Organic Phosphorus Hydrolysis in Epi- and Mesopelagic Waters. Front. Earth Sci. 2020, 8, 560893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Costa, M.; Cerro-Gálvez, E.; Martínez-Varela, A.; Casas, G.; Dachs, J. Anthropogenic Dissolved Organic Carbon and Marine Microbiomes. ISME J. 2020, 14, 2646–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, R.; Dachs, J. Polychlorinated Biphenyls in the Global Ocean. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 269–282. ISBN 978-0-12-805052-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, C.; Fu, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Fu, J.; Hao, Y.; Matsiko, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Novel Brominated Flame Retardants in West Antarctic Atmosphere (2011–2018): Temporal Trends, Sources and Chiral Signature. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, P.; Zhao, J.; Fu, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Atmospheric Organophosphate Esters in the Western Antarctic Peninsula over 2014–2018: Occurrence, Temporal Trend and Source Implication. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L.; Yang, M.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Y. Occurrence and Dry Deposition of Organophosphate Esters in Atmospheric Particles above the Bohai Sea and Northern Yellow Sea, China. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 269, 118831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Xie, Z.; Song, T.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mi, W.; Peng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, S.; Ebinghaus, R. Occurrence and Dry Deposition of Organophosphate Esters in Atmospheric Particles over the Northern South China Sea. Chemosphere 2015, 127, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, R.; Chen, D.; Sun, J.; Greig, D.J.; Wu, Y. Characterization of Brominated, Chlorinated, and Phosphate Flame Retardants in San Francisco Bay, an Urban Estuary. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, M.; Lin, C.; Wu, T.; Xin, M.; Gu, X.; Lu, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, B.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, X.; et al. Occurrence, Spatiotemporal Distribution, and Ecological Risks of Organophosphate Esters in the Water of the Yellow River to the Laizhou Bay, Bohai Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Z.; Yang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J. Review of organophosphate esters in seawater and marine sediments. Mar. Sci. 2023, 47, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Alemany, Ò.; Aminot, Y.; Vilà-Cano, J.; Köck-Schulmeyer, M.; Readman, J.W.; Marques, A.; Godinho, L.; Botteon, E.; Ferrari, F.; Boti, V.; et al. Halogenated and Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in European Aquaculture Samples. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, N.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Oursel, B.; Sempéré, R. Phthalates and Organophosphate Esters in Surface Water, Sediments and Zooplankton of the NW Mediterranean Sea: Exploring Links with Microplastic Abundance and Accumulation in the Marine Food Web. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 272, 115970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, K.; Lu, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhao, S.; Zheng, H.; Gao, Y.; Kaluwin, C.; Liu, Y.; Cai, M. Occurrence, Distribution and Risk Assessment of Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Surface Seawater of the West Pacific. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 170, 112691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L. Occurrence, Distribution Characteristics and Distribution of Organophosphates in Coastal Seawater and Sediments of the East Yellow. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N.L.S.; Kwok, K.Y.; Wang, X.; Yamashita, N.; Liu, G.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lam, P.K.S.; Lam, J.C.W. Assessment of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Aquatic Environments of China (Pearl River Delta, South China Sea, Yellow River Estuary) and Japan (Tokyo Bay). J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 371, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Huang, P.; Huang, Q.; Rao, K.; Lu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Gabrielsen, G.W.; Hallanger, I.; Ma, M.; Wang, Z. Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic Contaminants in Arctic Seawaters: On-Board Passive Sampling Coupled with Target and Non-Target Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 253, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Y.; Qian, Z.; Lin, W. Spatial Pattern Analysis Reveals Multiple Sources of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in Coastal Waters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yu, K.; Li, A.; Zeng, W.; Lin, T.; Wang, Y. Occurrence, Phase Distribution, and Bioaccumulation of Organophosphate Esters (OPEs) in Mariculture Farms of the Beibu Gulf, China: A Health Risk Assessment through Seafood Consumption. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Wu, H.; Mi, W.; Li, F.; Ji, C.; Ebinghaus, R.; Tang, J.; Xie, Z. Occurrences and Distribution Characteristics of Organophosphate Ester Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in the Sediments of the Bohai and Yellow Seas, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, Y.-G.; Chen, B.-J.; Liu, B.; Ma, Y.-H.; Li, M.; Zhuo, L.; Chen, S.-J. Legacy and Emerging Contaminants in Coastal Surface Sediments around Hainan Island in South China. Chemosphere 2019, 215, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Xu, L.; Hu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Liao, W.; Yu, Z. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants/Plasticizers in Coastal Sediments from the Taiwan Strait in China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 151, 110843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.-K.; Moon, H.-B. Organophosphate Flame Retardants and Plasticizers in Sediment and Bivalves along the Korean Coast: Occurrence, Geographical Distribution, and a Potential for Bioaccumulation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 156, 111275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, T.G.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Transfer of Emerging Organophosphate Flame Retardants in the Marine Food Webs of Laizhou Bay, North China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 13417–13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, M.; Zhao, H.; Xie, Q.; Du, J.; Chen, J. Organophosphate Esters in Sediment Cores from Coastal Laizhou Bay of the Bohai Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607–608, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Kim, U.-J.; Kannan, K. Occurrence and Distribution of Organophosphate Esters in Sediment from Northern Chinese Coastal Waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.-X.; Luo, X.-J.; Zheng, X.-B.; Li, Z.-R.; Sun, R.-X.; Mai, B.-X. Distribution of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in Sediments from the Pearl River Delta in South China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghimire, H.; Ariya, P.A. E-Wastes: Bridging the Knowledge Gaps in Global Production Budgets, Composition, Recycling and Sustainability Implications. Sustain. Chem. 2020, 1, 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Jiménez, J.; González-Fernández, D.; Fornier, M.; Schmidt, N.; Sempéré, R. Macro-Litter in Surface Waters from the Rhone River: Plastic Pollution and Loading to the NW Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 146, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; Van Der Zwet, J.; Damsteeg, J.-W.; Slat, B.; Andrady, A.; Reisser, J. River Plastic Emissions to the World’s Oceans. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolschke, H.; Sühring, R.; Mi, W.; Möller, A.; Xie, Z.; Ebinghaus, R. Atmospheric Occurrence and Fate of Organophosphorus Flame Retardants and Plasticizer at the German Coast. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 137, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, X. Persistent Organic Pollutant Cycling in Forests. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wania, F.; Haugen, J.-E.; Lei, Y.D.; Mackay, D. Temperature Dependence of Atmospheric Concentrations of Semivolatile Organic Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).