A Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm for Planning of Multi-Stage Activities in Modular Shipbuilding Considering Uncertainty Duration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

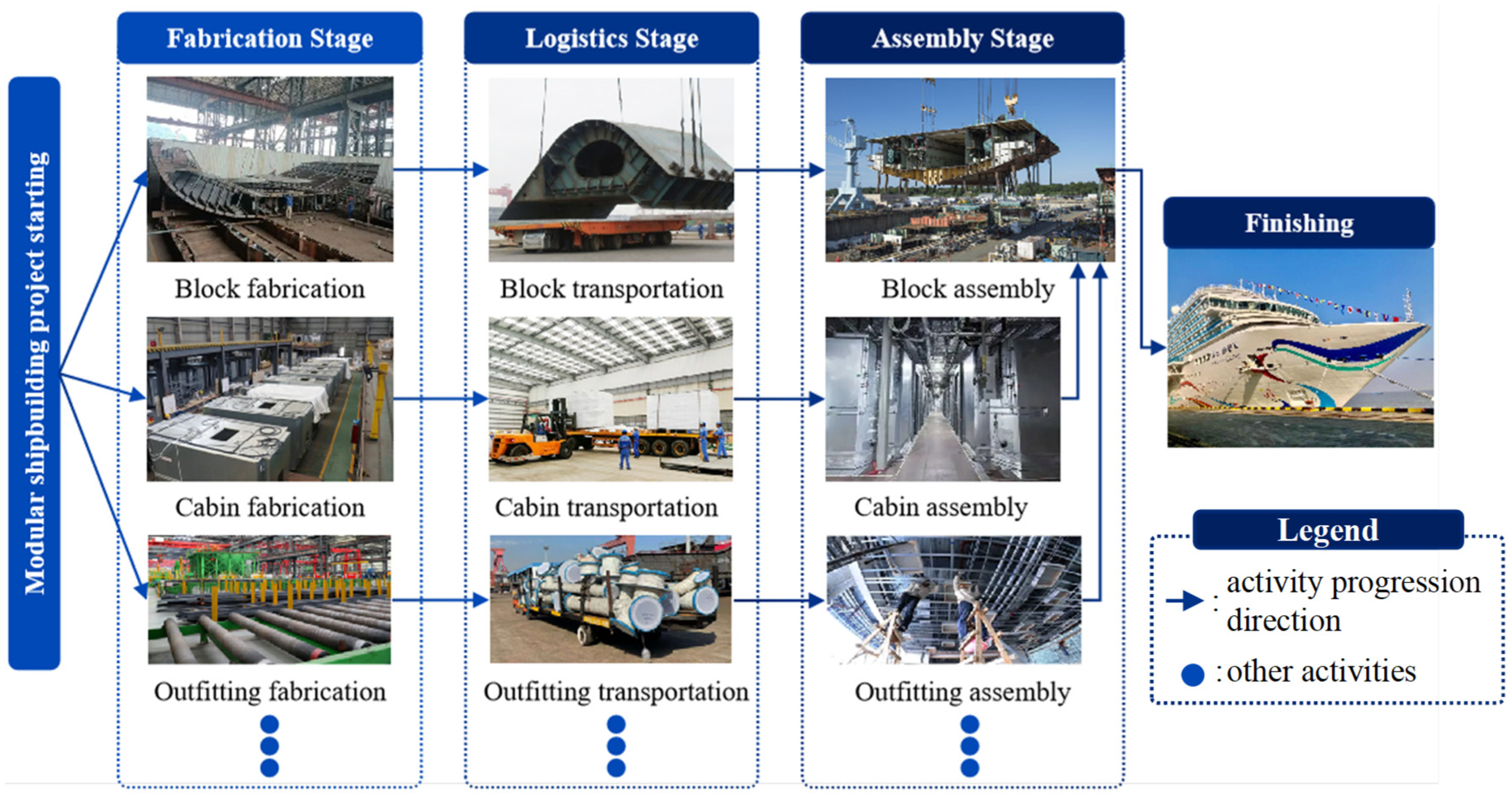

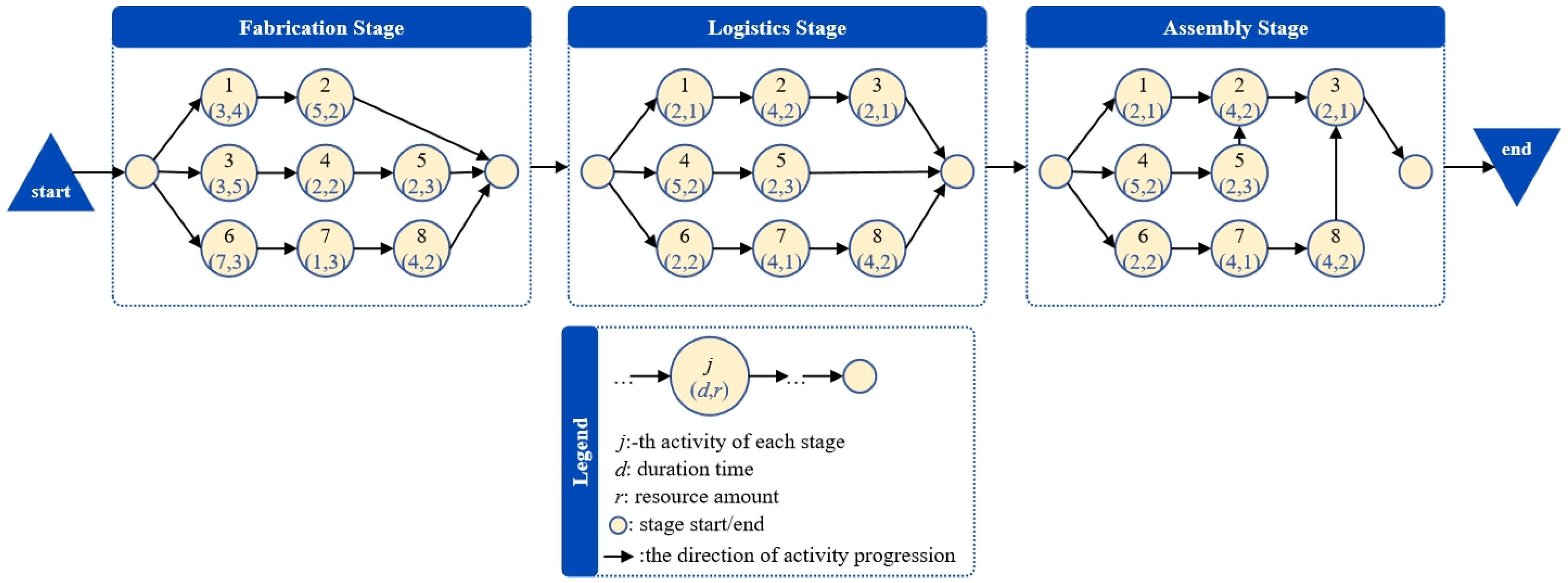

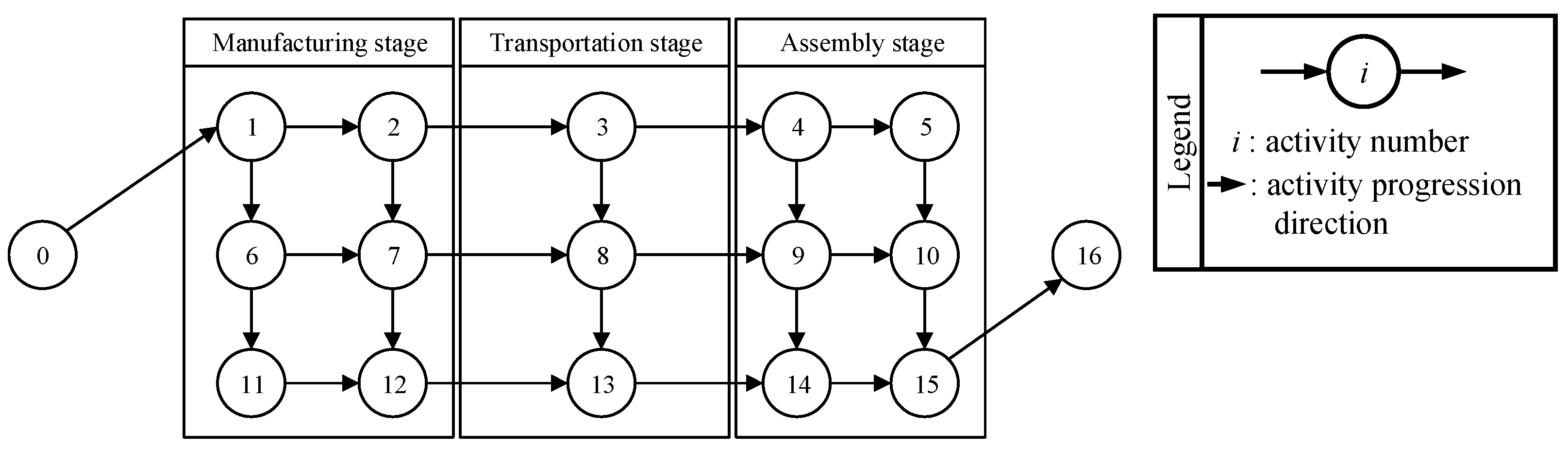

3. Modeling of Modular Shipbuilding Processes for Project Planning

3.1. Problem Description

3.2. M-F-MORCPSP Modeling

- A project is broken down into a series of tasks, each with a pre-determined baseline completion time, which is uncertain in practice.

- The exact duration of any given task is subject to variability.

- The initiation of any given task is contingent upon fulfilling its preconditions, which are defined by the logical relationships and completion status of other tasks in the project network.

- Resources are finite and cannot be replenished during the project’s lifecycle.

- There is no substitution between resources.

- Once an activity is underway, it cannot be interrupted.

- Each task has only one mode that can be executed.

- The manufacturing, transportation, and assembly phases are all connected and work as a cohesive unit.

- Once a phase is underway, it must be seen through to the end before jumping to another.

- The overarching optimization goal is the concurrent minimization of the project timeline and operational expenditures.

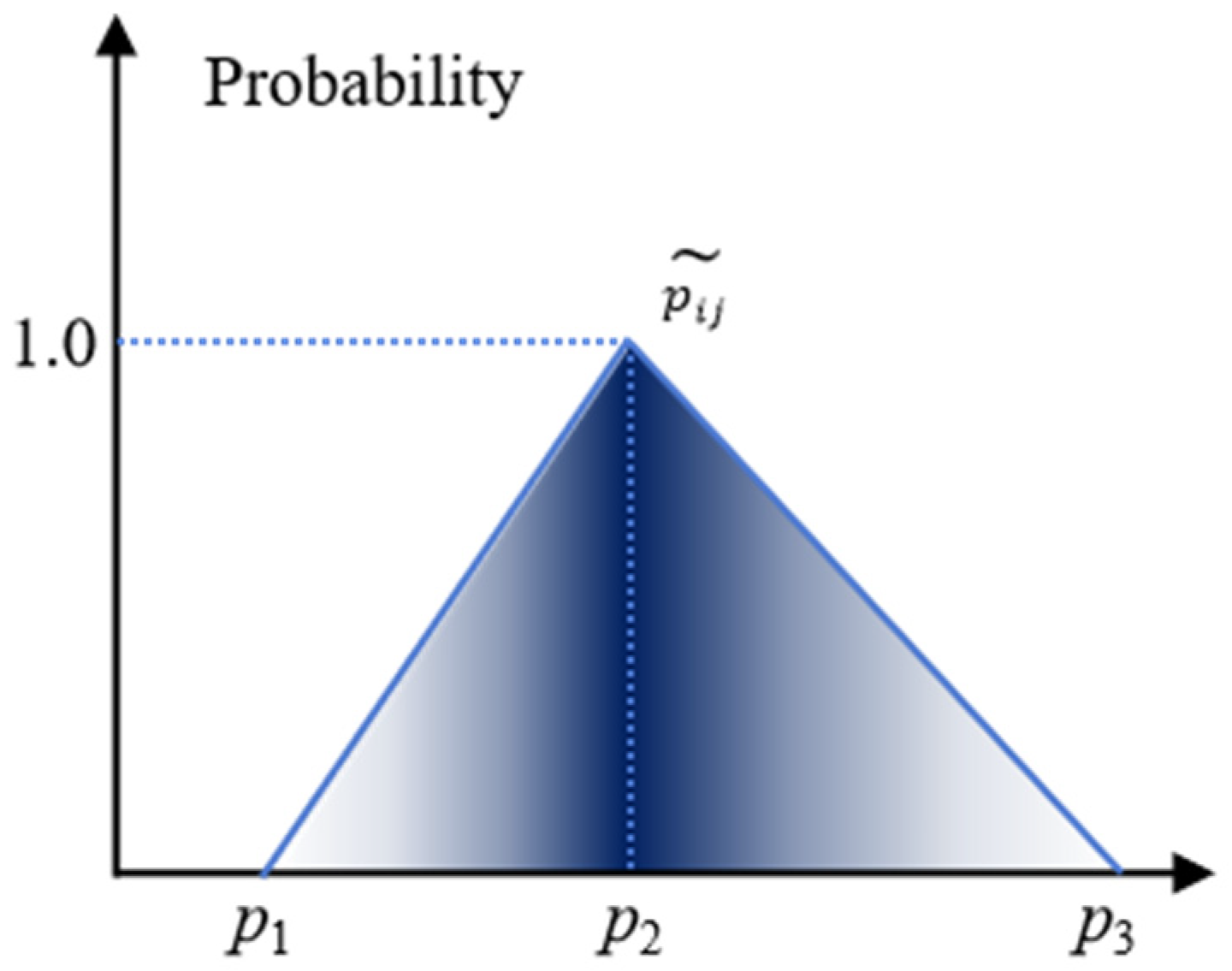

3.3. Representation of Fuzzy Processing Time of Activities

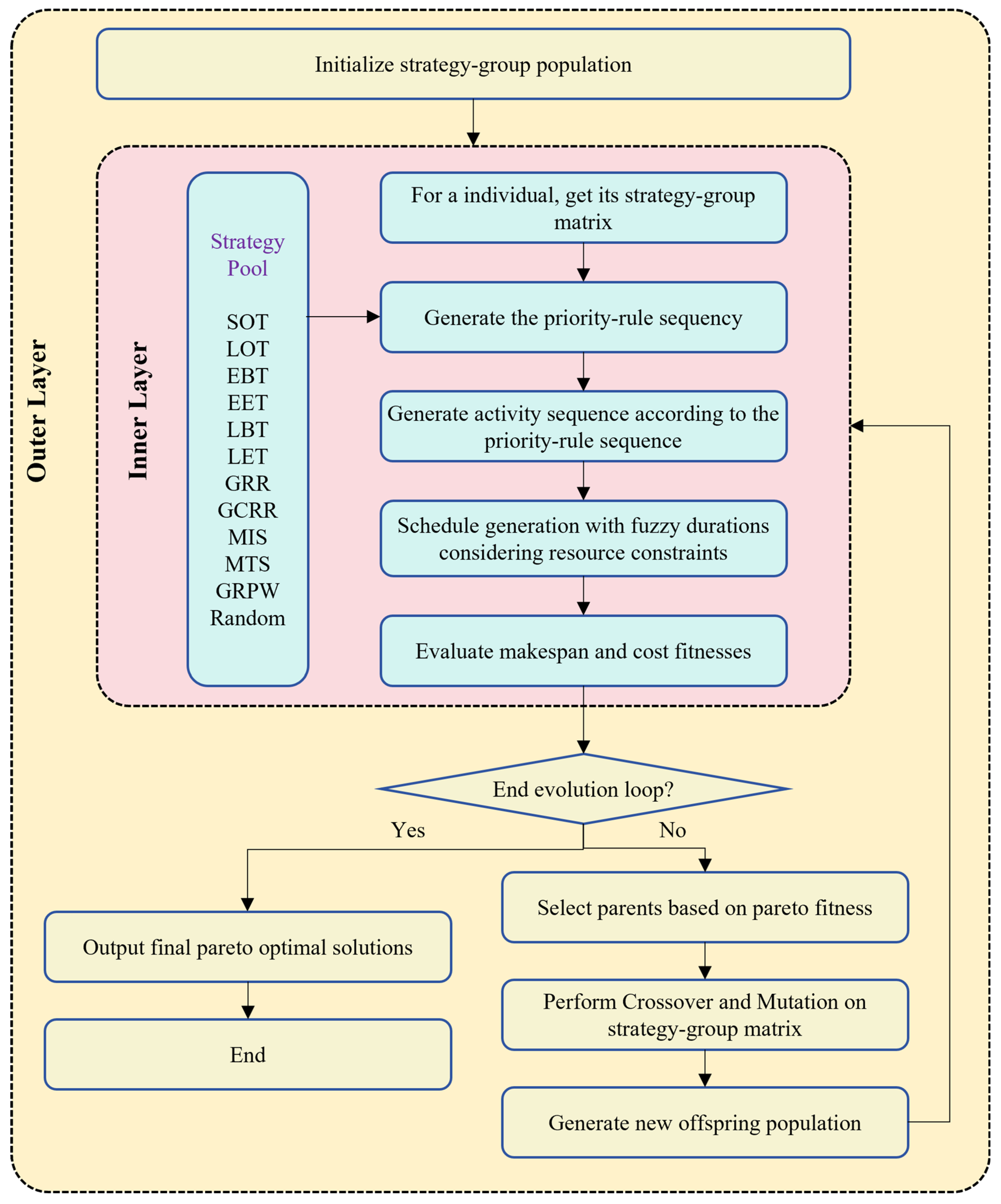

4. Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm

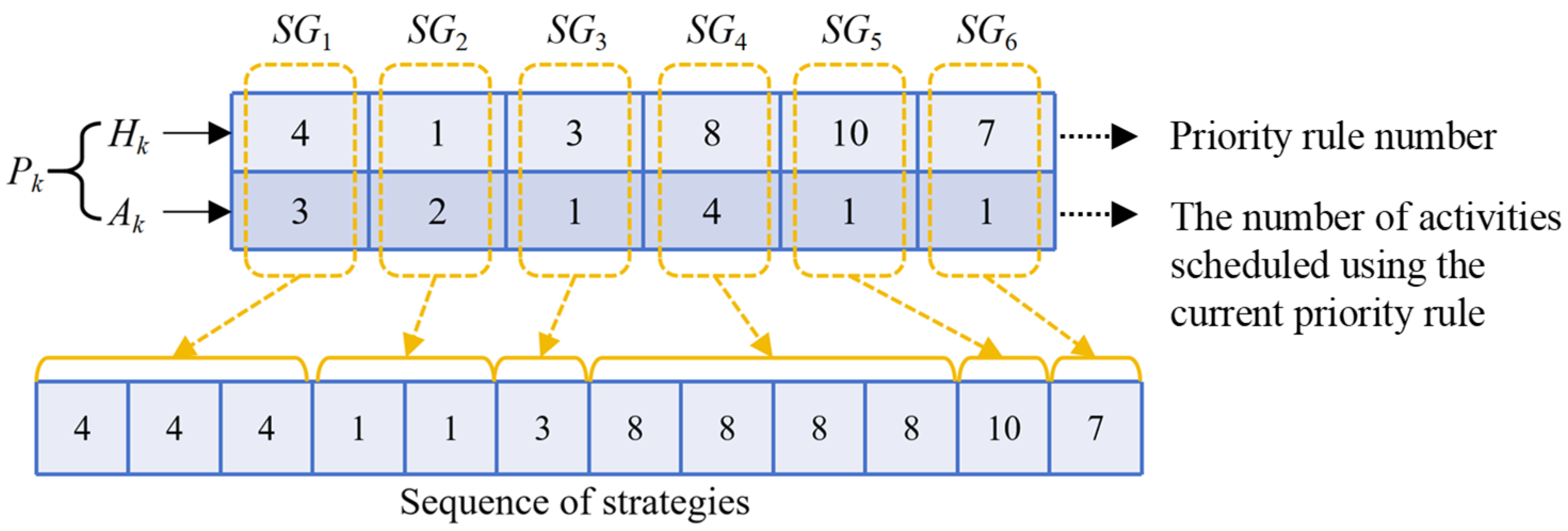

4.1. Inner-Layer Strategies

4.2. Outer-Layer Evolution Policy

- Population initialization

| Algorithm 1: Population initialization |

| Input: |

| : population size, : length of vectors, : set of all priority rules in Table 3, : tabu list, : number of non-dummy activities |

| Output: |

| Initial population |

| Begin |

| while do |

| for to do |

| Randomly select a priority rule from |

| remove |

| end for |

| if do |

| Select a random set of elements whose values are less than m and augment them by 1. |

| else if |

| Select a random set of elements whose values are less than m and augment them by . |

| end if |

| end while |

- Selection

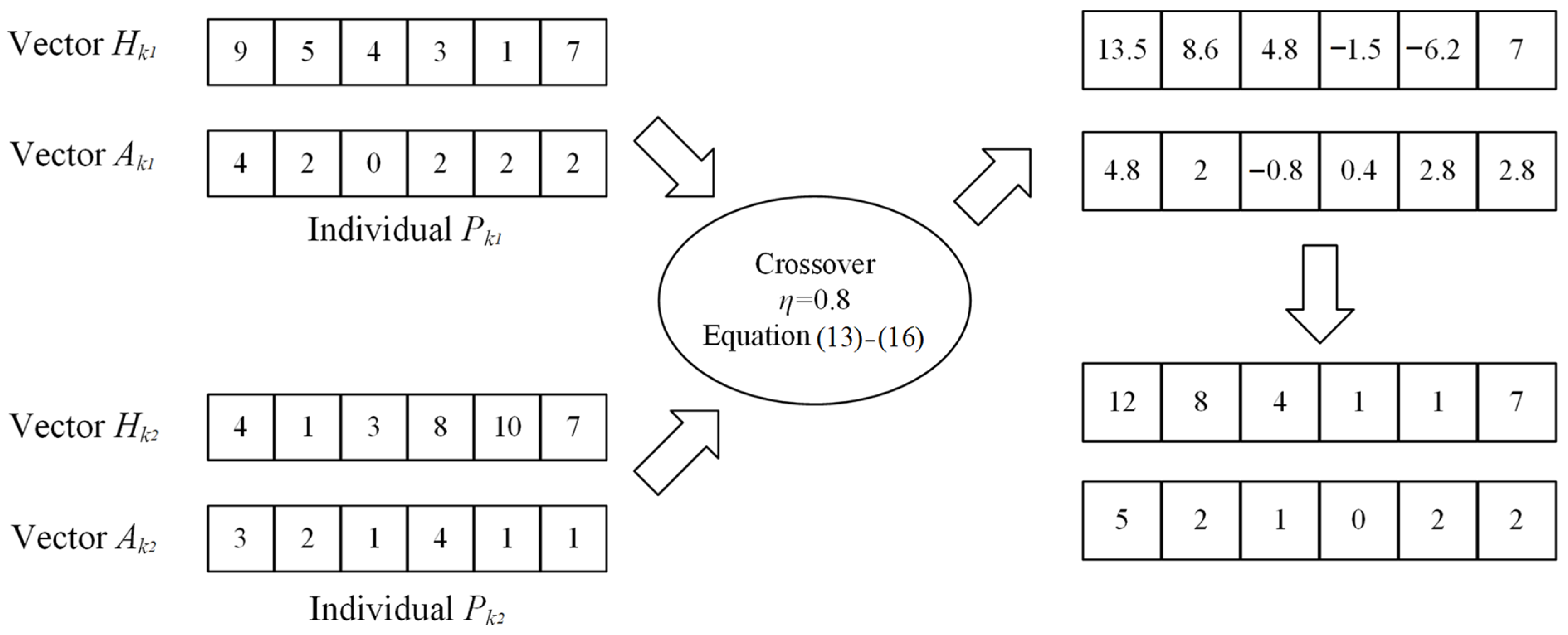

- Crossover

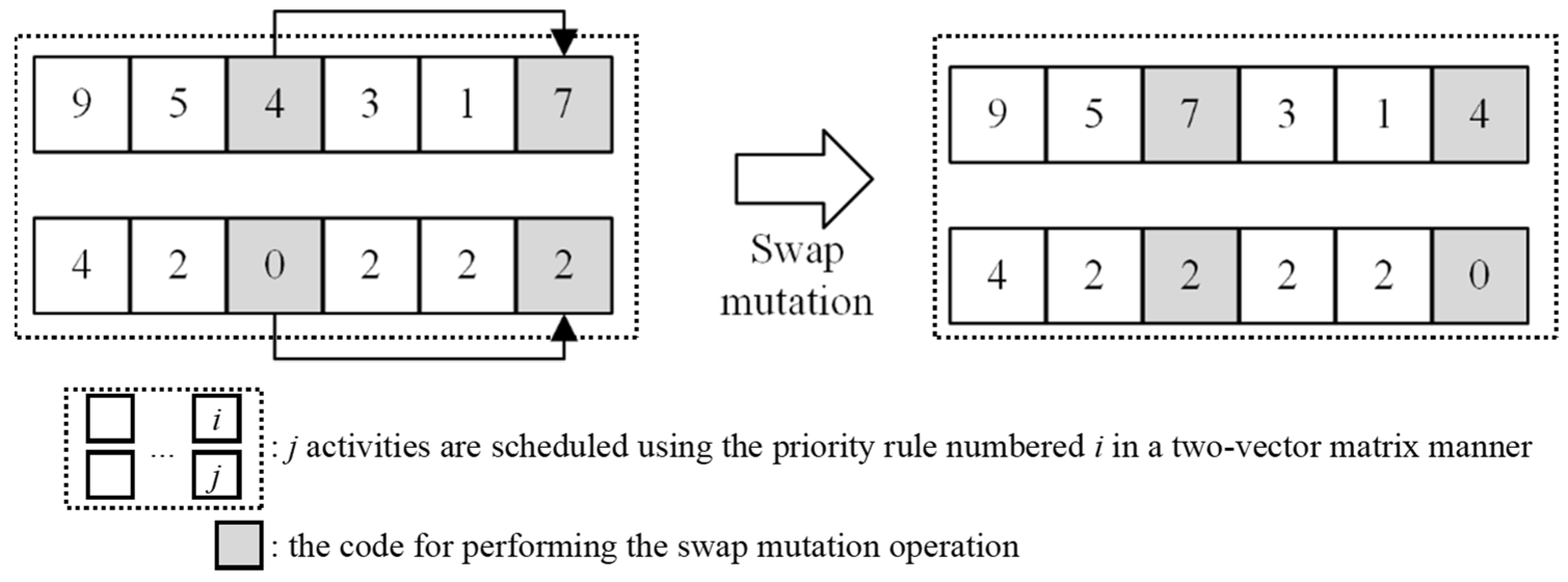

- Mutation

5. Verification Tests

5.1. Data Setup

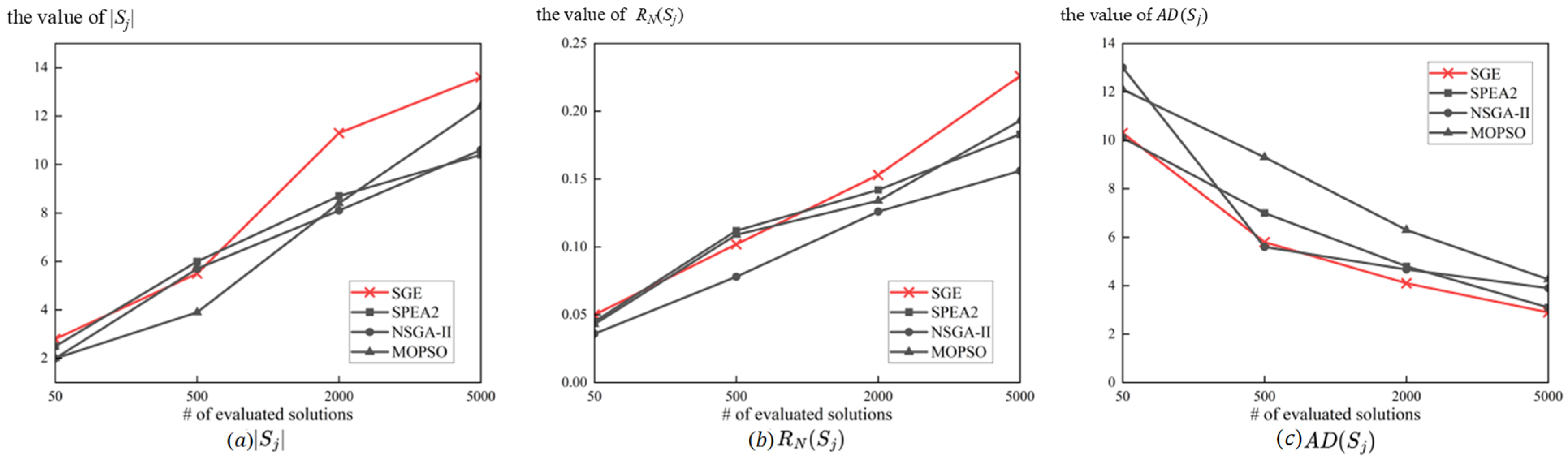

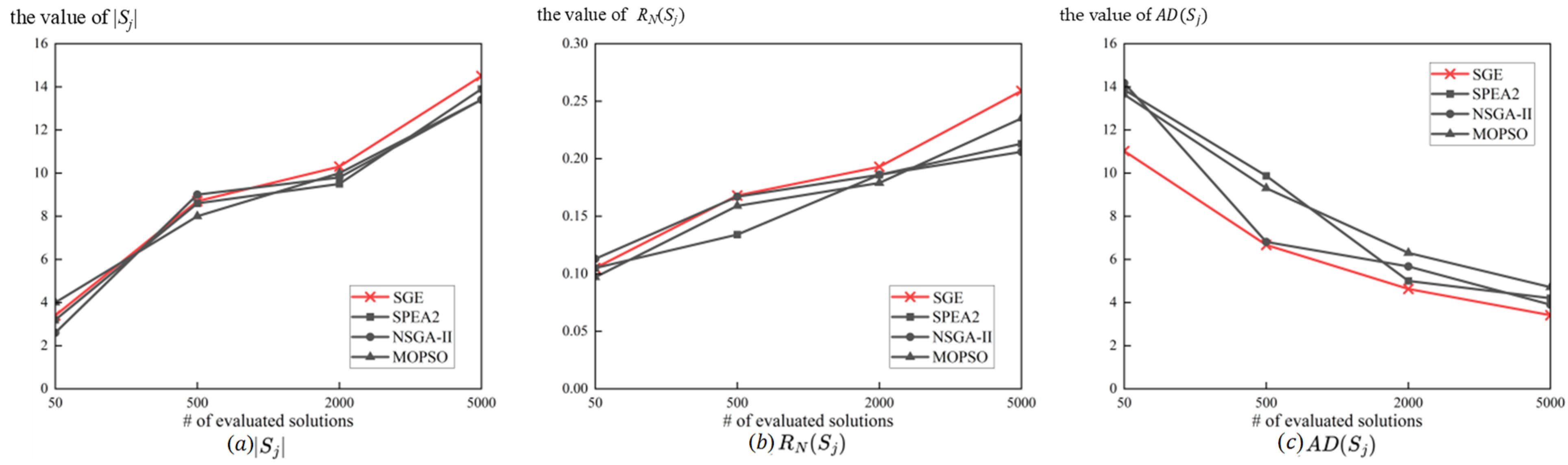

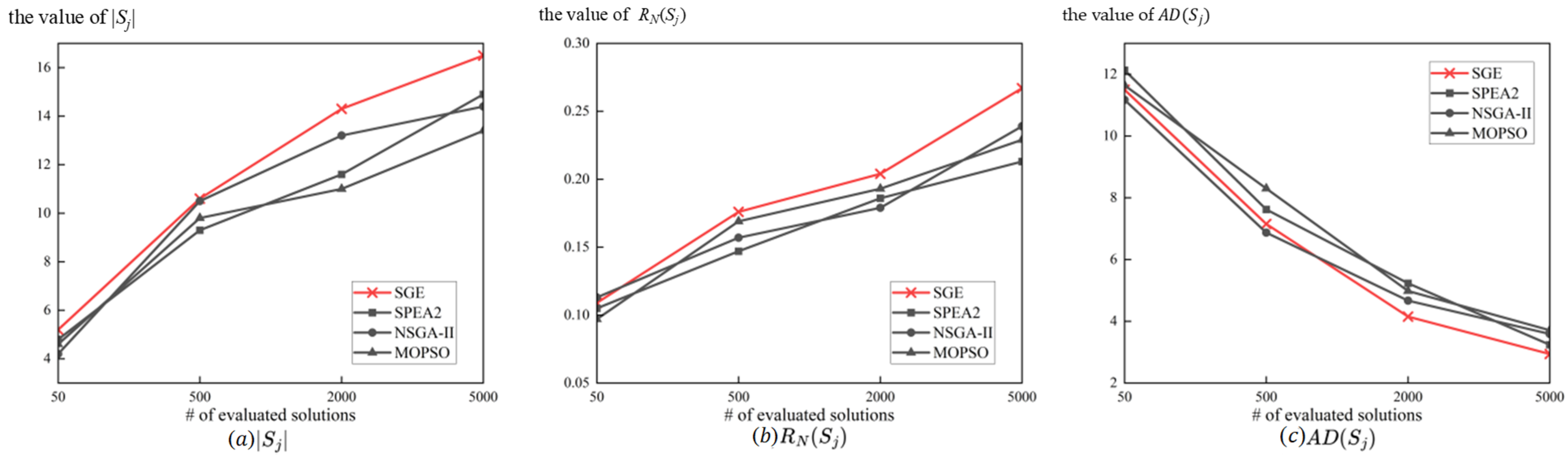

5.2. Performance Metrics

- Number of solutions . An excellent algorithm must avoid a local optimum solution and search for possible solutions as much as possible. Therefore, we hope the larger this indicator is, the better.

- Ratio of non-dominated solutions , which is calculated as:

- Average distance , which is calculated as:

5.3. Testing Results

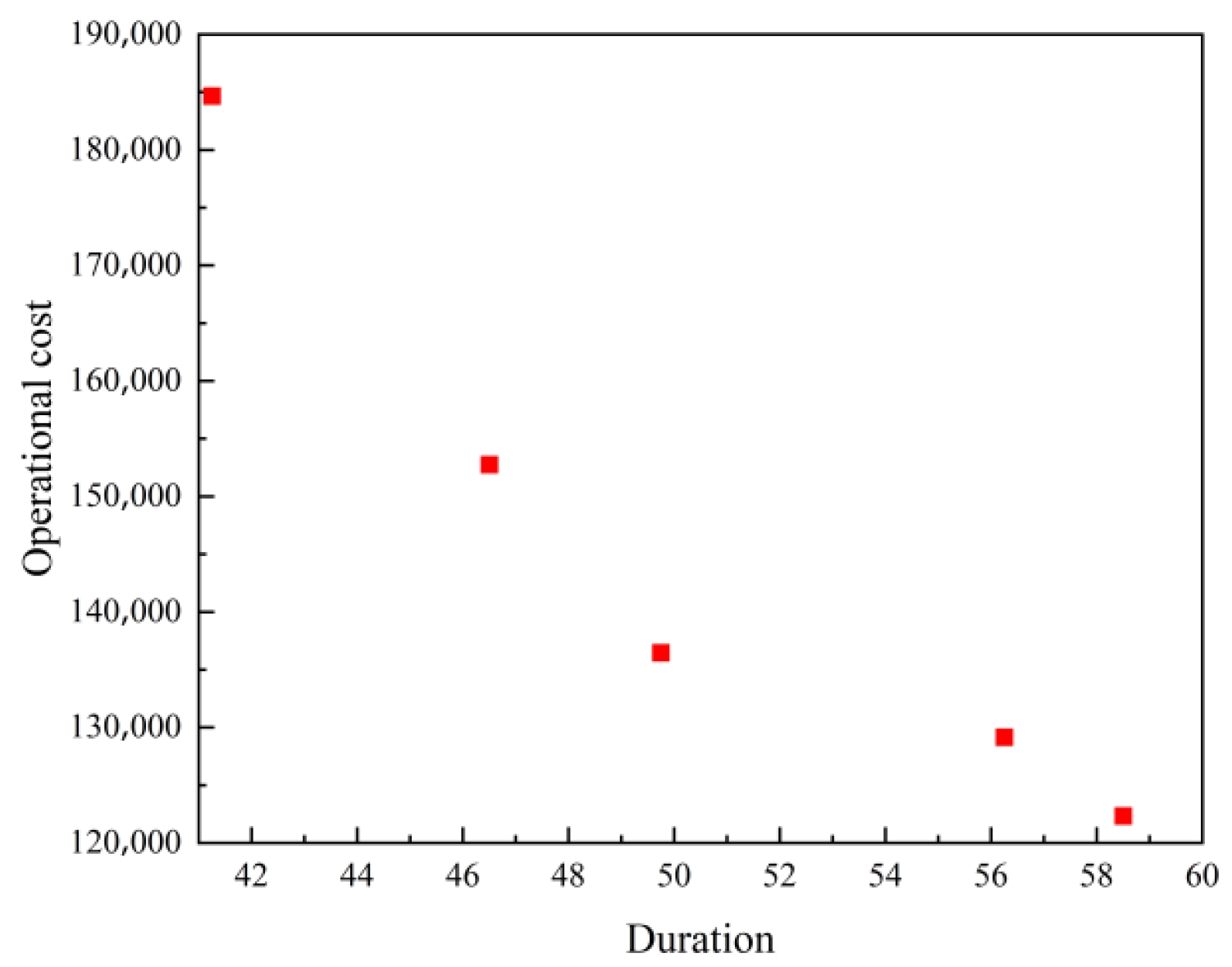

6. Real-Case Application

7. Conclusions

- It explicitly models uncertain activity durations using triangular fuzzy numbers, capturing the ambiguity of manual operations and dynamic resource allocation in modular shipbuilding;

- It formulates a bi-objective optimization framework that simultaneously minimizes fuzzy makespan and total operational cost, aligning with real-world project management needs.

- Grouped tests based on the PSPLIB benchmark instances show that, when handling large-scale instances, compared with the mainstream algorithms SPEA2, NSGA-II, and MOPSO, the Strategy-Group Evolution algorithm achieves a 28% higher average computational benefit, while its average computational efficiency is only 14% lower—verifying the superiority of its algorithmic performance;

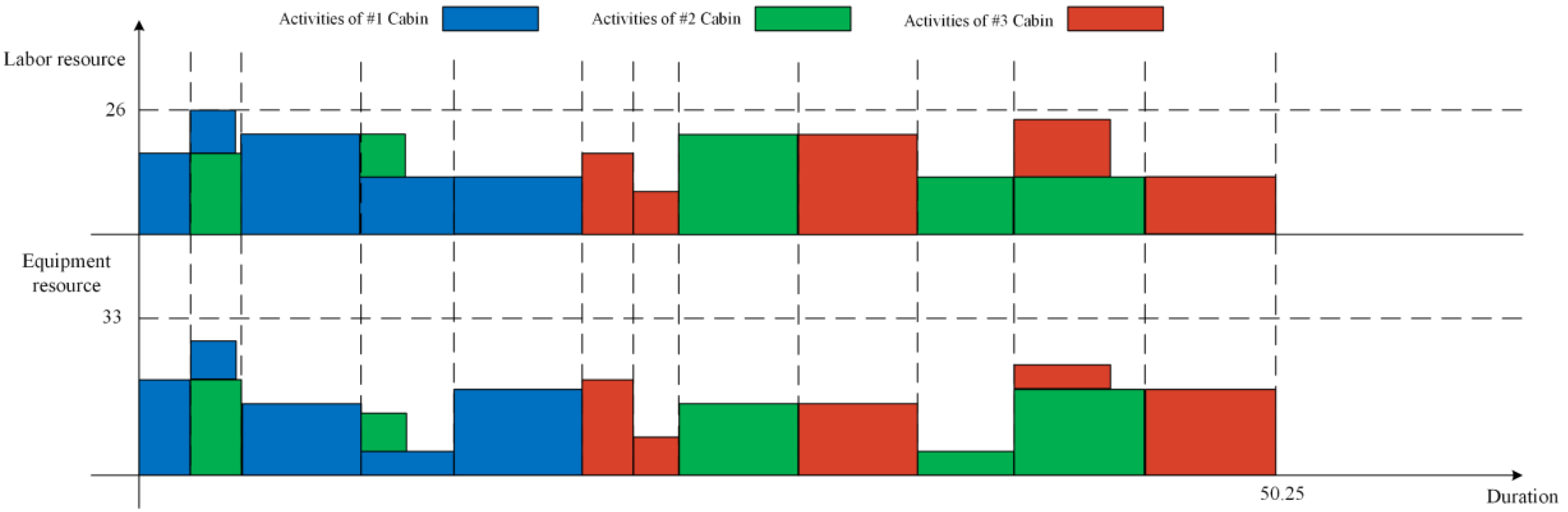

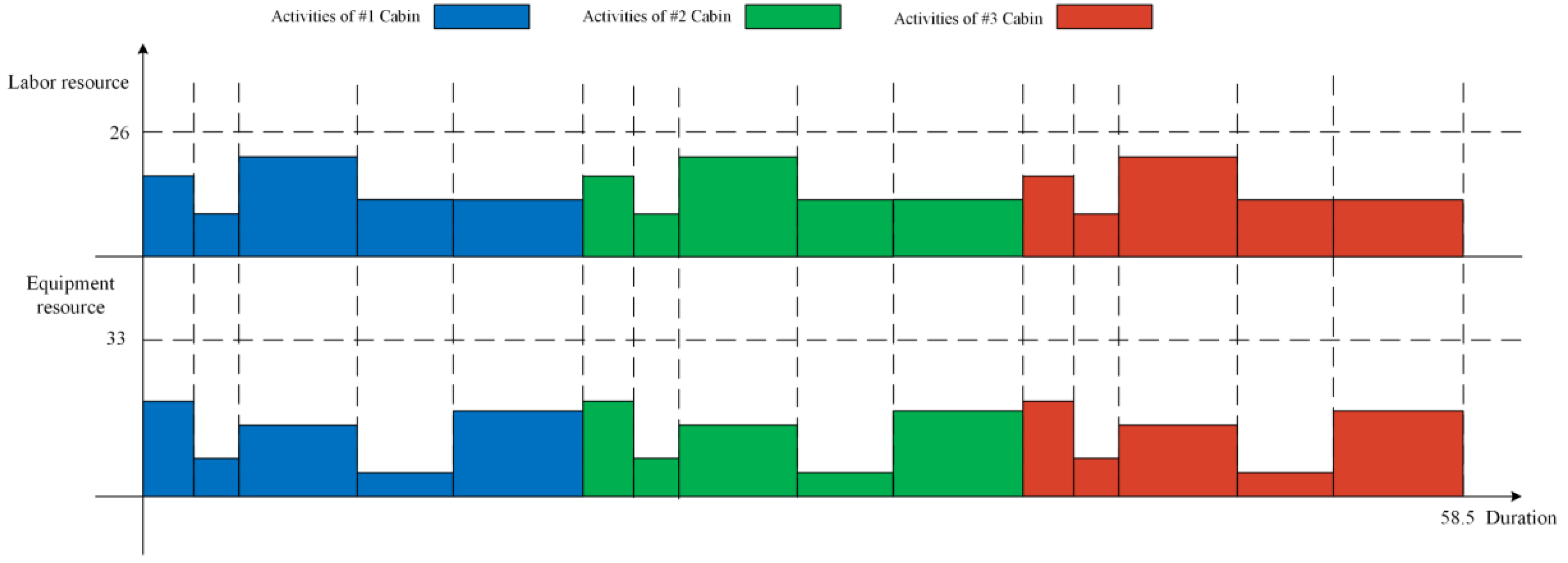

- A real-world case study from a cruise ship prefabricated cabin project demonstrates that, compared to the shipyard’s existing manual scheduling method, the algorithm reduces the project’s fuzzy makespan by 16.2% and operational cost by 8.3%, confirming its practical viability.

- Incorporating dynamic events into the model to enhance its adaptability to real-time project disruptions;

- Extending the Strategy-Group Evolution algorithm’s strategy pool to include multi-site coordination rules, addressing the cross-yard transportation and assembly challenges in large-scale modular shipbuilding.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.M.; Woo, J.H. Development of production planning system for shipbuilding using component-based development framework. Int. J. Nav. Arch. Ocean Eng. 2021, 13, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, A.; Ünsan, Y.; Barlas, B. A novel approach for planning of shipbuilding processes. Brodogradnja 2023, 74, 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuni, I.Y.; Shen, G.Q. Barriers to the adoption of modular integrated construction: Systematic review and meta-analysis, integrated conceptual framework, and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohourian, M.; Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Almaskati, D.; Construction, M. Modular Construction: A Comprehensive Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; Zhong, B.; Fung, I.W.; Lee, Y.Y.R. Exploring the adoption of blockchain in modular integrated construction projects: A game theory-based analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.R. Applications of Modular Construction Techniques for Habitability Spaces in Naval Ship Design and Production. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/50481 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Liu, J.; Yin, J.; Khan, R.U. Scheduling management and optimization analysis of intermediate products transfer in a shipyard for cruise ships. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Li, J.; Guo, H.; Wu, X. Research on Collaborative Planning and Symmetric Scheduling for Parallel Shipbuilding Projects in the Open Distributed Manufacturing Environment. Symmetry 2020, 12, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.E., Jr.; Walker, M.R. Critical-Path Planning and Scheduling: An Introduction. In Proceedings of the IRE-AIEE-ACM ‘59 (Eastern): Papers Presented at the December 1–3, 1959, Eastern Joint IRE-AIEE-ACM Computer Conference, New York, NY, USA, 1–3 December 1959; Mauchly Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1959; pp. 160–173. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K.; Zhang, L. Multi-objective optimization for improved project management: Current status and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddhakulsomsiri, J.; Kim, D.S. Priority rule-based heuristic for multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling problems with resource vacations and activity splitting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 178, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritsker, A.A.B.; Waiters, L.J.; Wolfe, P.M. Multiproject Scheduling with Limited Resources: A Zero-One Programming Approach. Manag. Sci. 1969, 16, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Beek, T.; Souravlias, D.; van Essen, J.; Pruyn, J.; Aardal, K. Hybrid differential evolution algorithm for the resource constrained project scheduling problem with a flexible project structure and consumption and production of resources. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 313, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Beek, T.; van Essen, J.; Pruyn, J.; Aardal, K. Exact solution methods for the Resource Constrained Project Scheduling Problem with a flexible Project Structure. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 322, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Kao, Y.; Ito, T. A project scheduling problem with spatial resource constraints and a corresponding guided local search algorithm. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2019, 70, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Li, H.; Xu, Z. Multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling with uncertain activity cost. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 168, 114475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.C.; Neves, F.d.A.d.; Souza, M.J.F. Multi-objective metaheuristic algorithms for the resource-constrained project scheduling problem with precedence relations. Comput. Oper. Res. 2014, 44, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, F.; Arashpour, M.; Mirnezami, S.-A.; Shahabi-Shahamiri, R.; Ghasemi, M. Multi-skill resource-constrained project scheduling problem considering overlapping: Fuzzy multi-objective programming approach to a case study. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ballesteros, S.; Alcaraz, J.; Anton-Sanchez, L. Metaheuristics for the bi-objective resource-constrained project scheduling problem with time-dependent resource costs: An experimental comparison. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 163, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamginzadeh, A.; Najafi, A.A.; Khalilzadeh, M. Multi-Objective Multi-Skill Resource-Constrained Project Scheduling Problem Under Time Uncertainty. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 23, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Ye, S.; Lin, L.; Gen, M. Multi-objective multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling with fuzzy activity durations in prefabricated building construction. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birjandi, A.; Mousavi, S.M. Fuzzy resource-constrained project scheduling with multiple routes: A heuristic solution. Autom. Constr. 2019, 100, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bold, M.; Goerigk, M. A faster exact method for solving the robust multi-mode resource-constrained project scheduling problem. Oper. Res. Lett. 2022, 50, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, S.; Kolisch, R. Experimental evaluation of state-of-the-art heuristics for the resource-constrained project scheduling problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 127, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminaniesfahani, A.; Gu, H.; Naeni, L.M.; Salehipour, A. An efficient relax-and-solve method for the multi-mode resource constrained project scheduling problem. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 338, 41–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Meng, J. A Multi-objective Fuzzy Genetic Algorithm for Job-shop Scheduling Problems. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security, Guangzhou, China, 3–6 November 2006; pp. 398–401. [Google Scholar]

- Nezhad, S.S.; Assadi, R.G. Preference ratio-based maximum operator approximation and its application in fuzzy flow shop scheduling. Appl. Soft Comput. 2008, 8, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D. A genetic algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling with fuzzy processing time. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 2995–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indices | |

|---|---|

| Stage number, | |

| Number of the task in stage , | |

| Number of resource, | |

| Time | |

| Parameters | |

| Fuzzy start time of task in stage . | |

| Fuzzy end time of task in stage . | |

| Fuzzy operation time of task in stage . | |

| Operational cost per time unit of activity in stage . | |

| Set of preorder stages of stage . | |

| Set of preorder tasks of task in stage . | |

| Maximum amount of existing resource . | |

| Expected maximum timeline of the event. | |

| Total expected expenditures of the event. | |

| Decision variables | |

| Decision variable, where if task of stage is scheduled at time , or else . | |

| Decision variable, where if resource is selected for task in stage , or else . |

| Operations | Rules |

|---|---|

| Ranking | Criterion 1. |

| Criterion 2. | |

| Criterion 3. |

| No. | Inner-Layer Strategy | Priority Rule | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SOT | Shortest operation time | |

| 2 | LOT | Longest operation time | |

| 3 | EBT | Earliest beginning time | |

| 4 | EET | Earliest ending time | |

| 5 | LBT | Latest beginning time | |

| 6 | LET | Latest ending time | |

| 7 | GRR | Greatest resource required | |

| 8 | GCRR | Greatest cumulative resource required | |

| 9 | MIS | Most immediate amount of successors | |

| 10 | MTS | Most total amount of successors | |

| 11 | GRPW | Greatest rank positional weight | |

| 12 | Random | Random priority |

| Set Number | Number of Instances | Number of Tasks per Instance | Number of Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| J30 | 50 | 30 | 4 |

| J60 | 50 | 60 | 4 |

| J90 | 50 | 90 | 4 |

| Algorithm | Strategy-Group Evolution | SPEA2 | NSGA-II | MOPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Settings | crossover probability: 0.8 mutation probability: 0.2 population size: 30 max iterations: 150 | crossover probability: 0.8 mutation probability: 0.2 population size: 30 max iterations: 150 | crossover probability: 0.8 mutation probability: 0.2 population size: 30 max iterations: 150 | inertia weight: 0.5 cognitive constant: 1 social constant: 2 n.g.r.i.d.: 30 max iterations: 150 |

| Algorithm | Strategy-Group Evolution | SPEA2 | NSGA-II | MOPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average computation time per run | 12.26 s | 10.14 s | 9.33 s | 11.41 s |

| Activity Node | Activity Name | Labor Resource | Equipment Resource | Fuzzy Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Start node (dummy) | - | - | - |

| 1 | #1 Wet unit positioning and installation | 17 | 20 | (1, 2, 4) |

| 2 | #1 Cabin prefabricate | 9 | 8 | (1, 2, 3) |

| 3 | #1 Cabin storage and transportation | 21 | 15 | (3, 5, 8) |

| 4 | #1 Cabin embarkation and pushing | 12 | 5 | (2, 4, 7) |

| 5 | #1 Cabin installation and commission | 12 | 18 | (2, 6, 9) |

| 6 | #2 Wet unit positioning and installation | 17 | 20 | (1, 2, 4) |

| 7 | #2 Cabin prefabricate | 9 | 8 | (1, 2, 3) |

| 8 | #1 Cabin storage and transportation | 21 | 15 | (3, 5, 8) |

| 9 | #2 Cabin embarkation and pushing | 12 | 5 | (2, 4, 7) |

| 10 | #2 Cabin installation and commission | 12 | 18 | (2, 6, 9) |

| 11 | #3 Wet unit positioning and installation | 17 | 20 | (1, 2, 4) |

| 12 | #3 Cabin prefabricate | 9 | 8 | (1, 2, 3) |

| 13 | #3 Cabin storage and transportation | 21 | 15 | (3, 5, 8) |

| 14 | #3 Cabin embarkation and pushing | 12 | 5 | (2, 4, 7) |

| 15 | #3 Cabin installation and commission | 12 | 18 | (2, 6, 9) |

| 16 | Finish node (dummy) | - | - | - |

| Scheme No. | Fuzzy Duration | Operational Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (21, 42, 60) | 184,680 |

| 2 | (22, 48, 68) | 152,760 |

| 3 | (28, 51, 69) | 136,460 |

| 4 | (30, 62, 71) | 129,160 |

| 5 | (32, 65, 72) | 122,340 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Q.; Li, J.; Wu, X.; Dong, R.; Xu, Z.; Song, D.; Zhou, L. A Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm for Planning of Multi-Stage Activities in Modular Shipbuilding Considering Uncertainty Duration. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112130

Zhou Q, Li J, Wu X, Dong R, Xu Z, Song D, Zhou L. A Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm for Planning of Multi-Stage Activities in Modular Shipbuilding Considering Uncertainty Duration. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112130

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Qi, Jinghua Li, Xiaoyuan Wu, Ruipu Dong, Zhichao Xu, Dening Song, and Lei Zhou. 2025. "A Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm for Planning of Multi-Stage Activities in Modular Shipbuilding Considering Uncertainty Duration" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112130

APA StyleZhou, Q., Li, J., Wu, X., Dong, R., Xu, Z., Song, D., & Zhou, L. (2025). A Strategy-Group Evolution Algorithm for Planning of Multi-Stage Activities in Modular Shipbuilding Considering Uncertainty Duration. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112130