Structural Response Research for a Submarine Power Cable with Corrosion-Damaged Tensile Armor Layers Under Pure Tension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Homogenization Theory and Periodic Boundary Conditions

3. RUC Finite Element Model

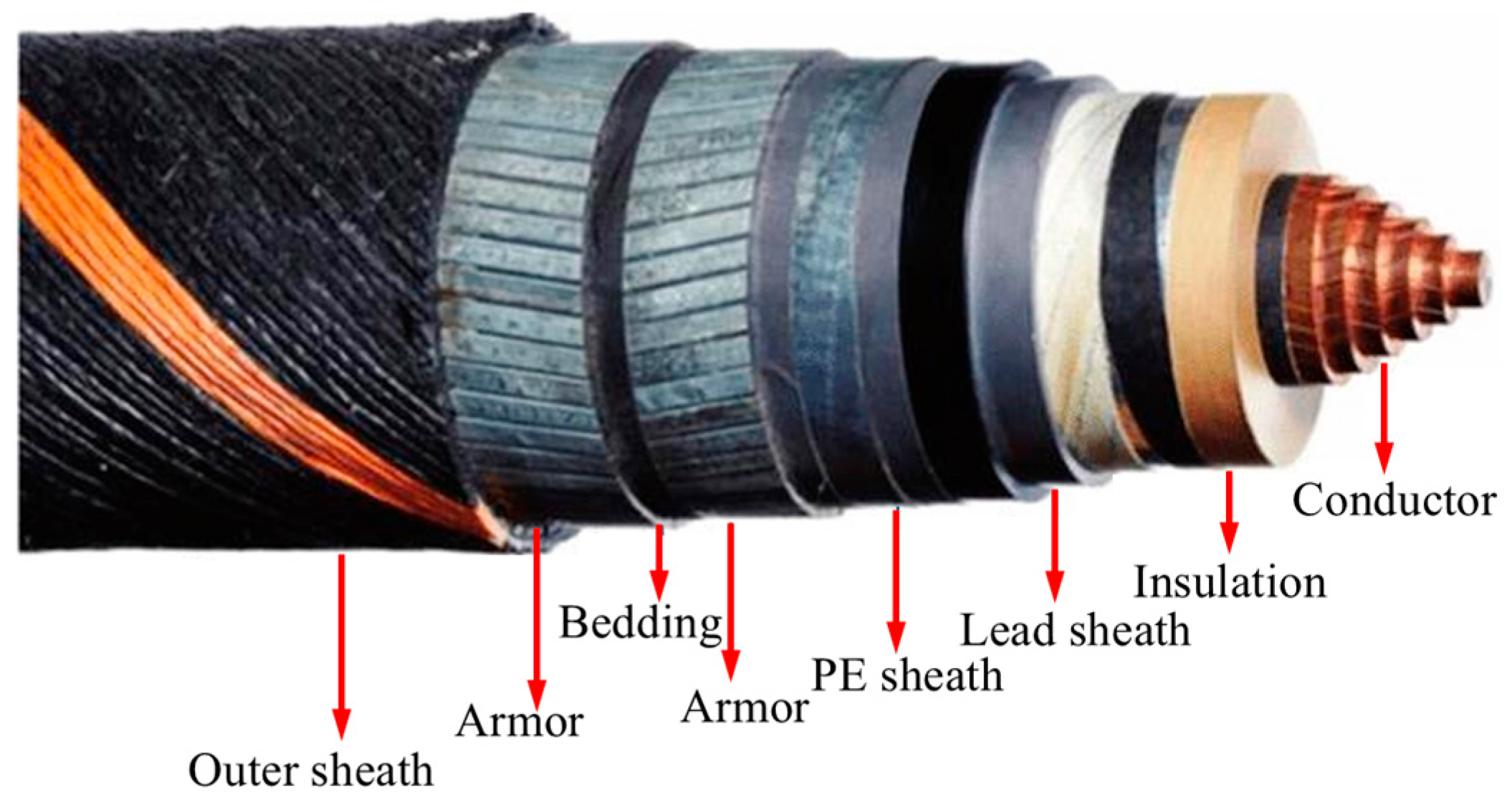

3.1. Finite Element Modeling

3.2. Interaction and Boundary Condition Setting

3.3. Mesh Generation and Element Type

4. Results and Discussions

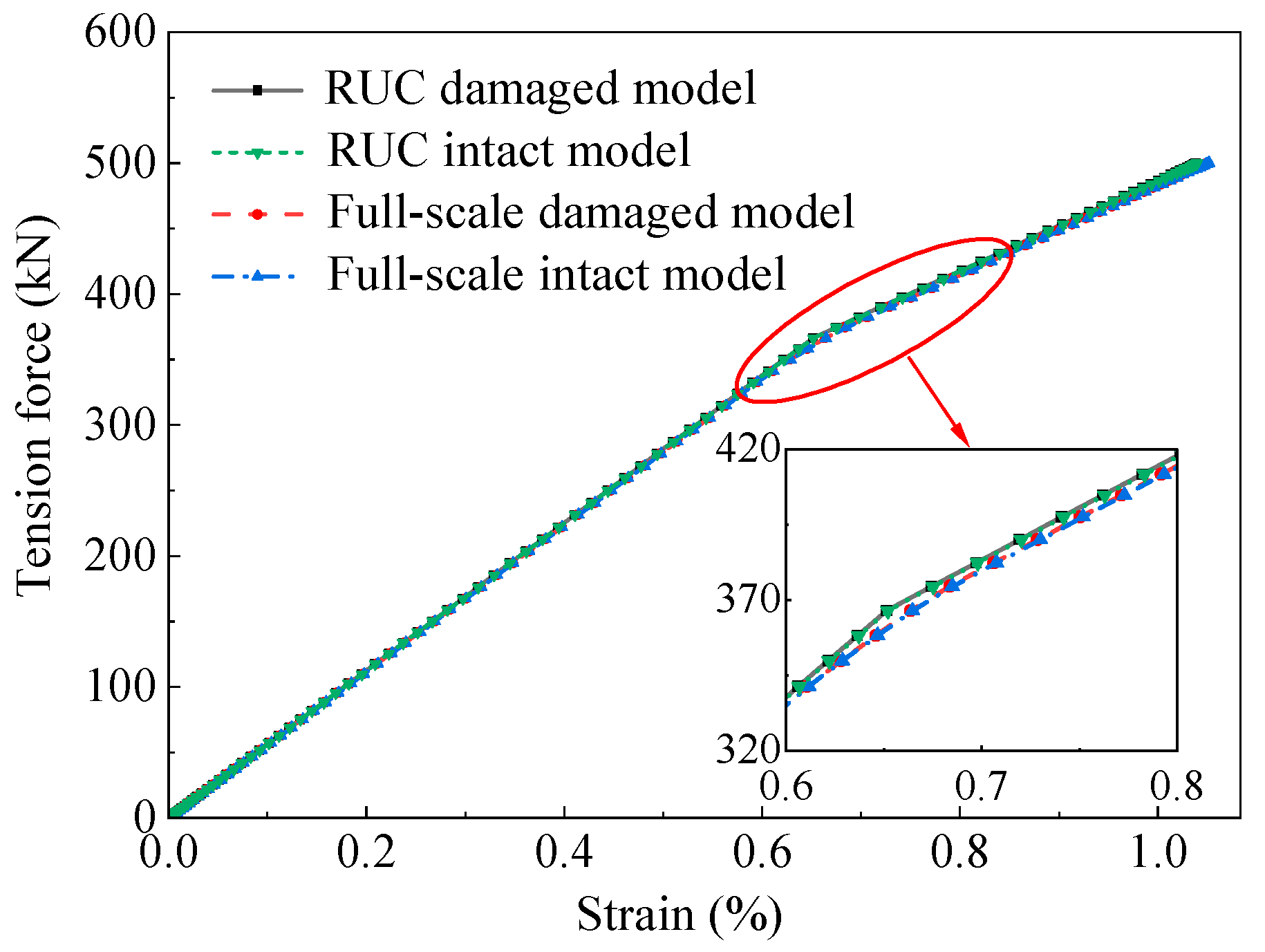

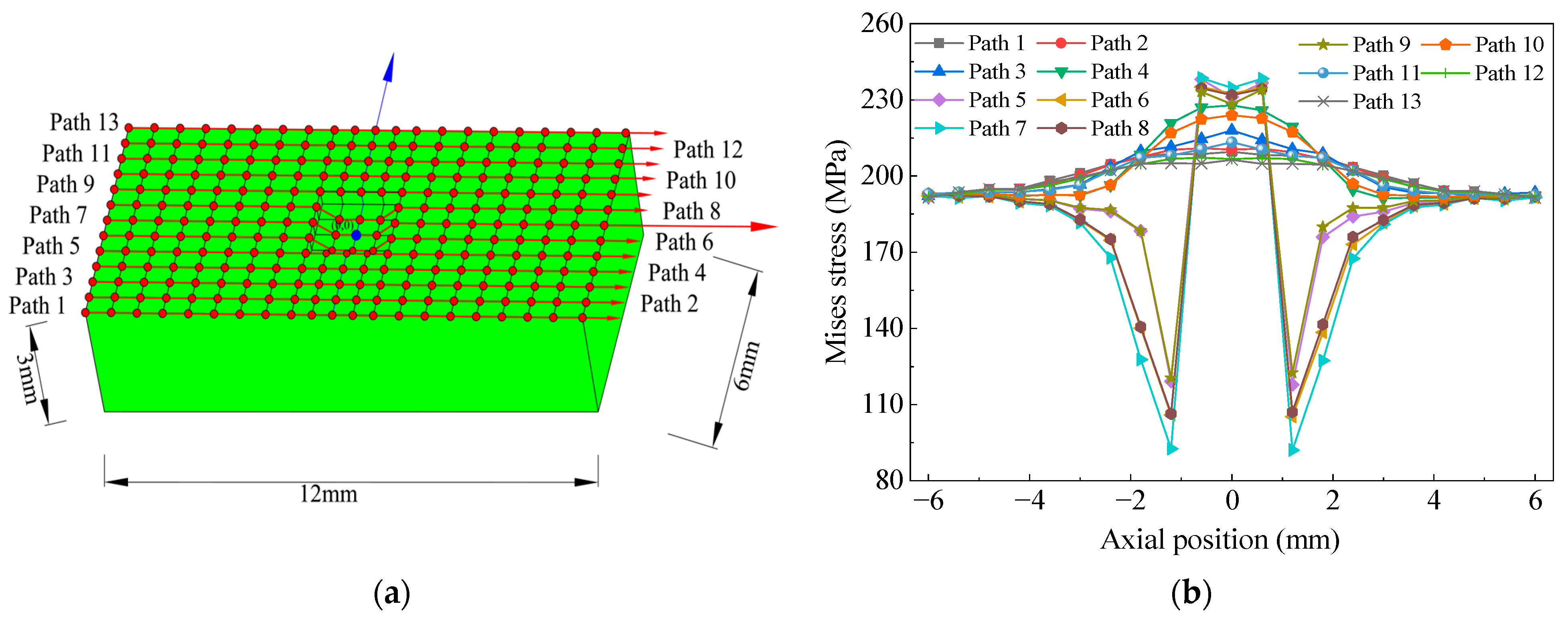

4.1. RUC Model Verification

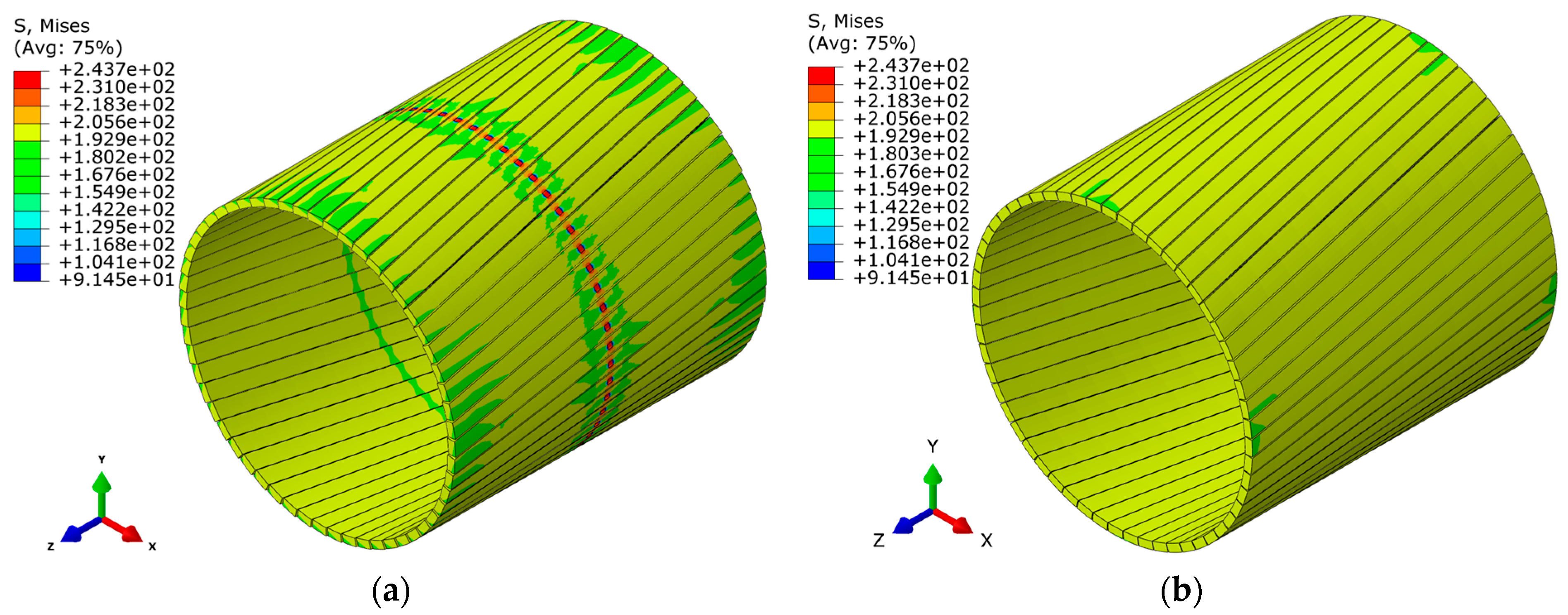

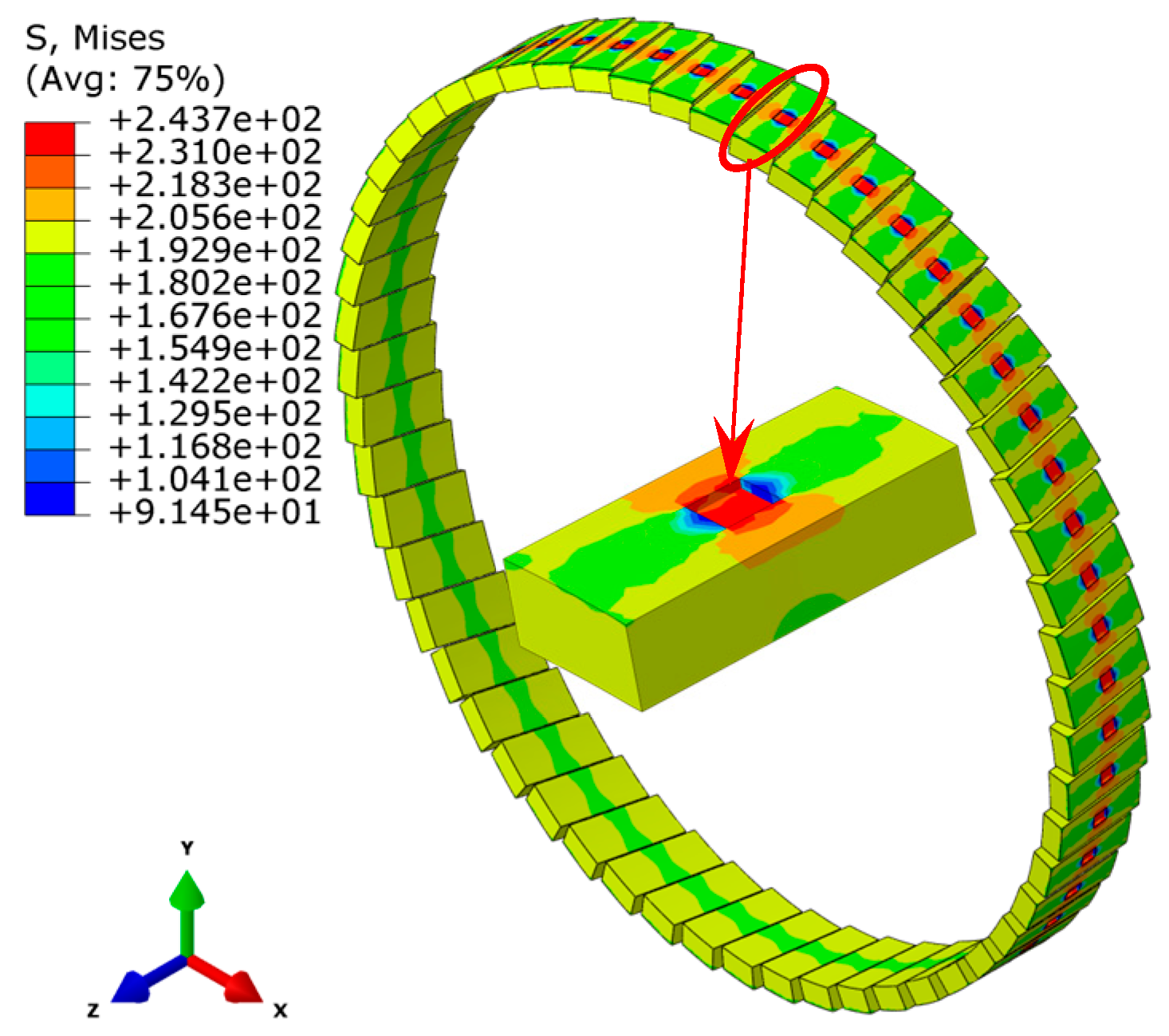

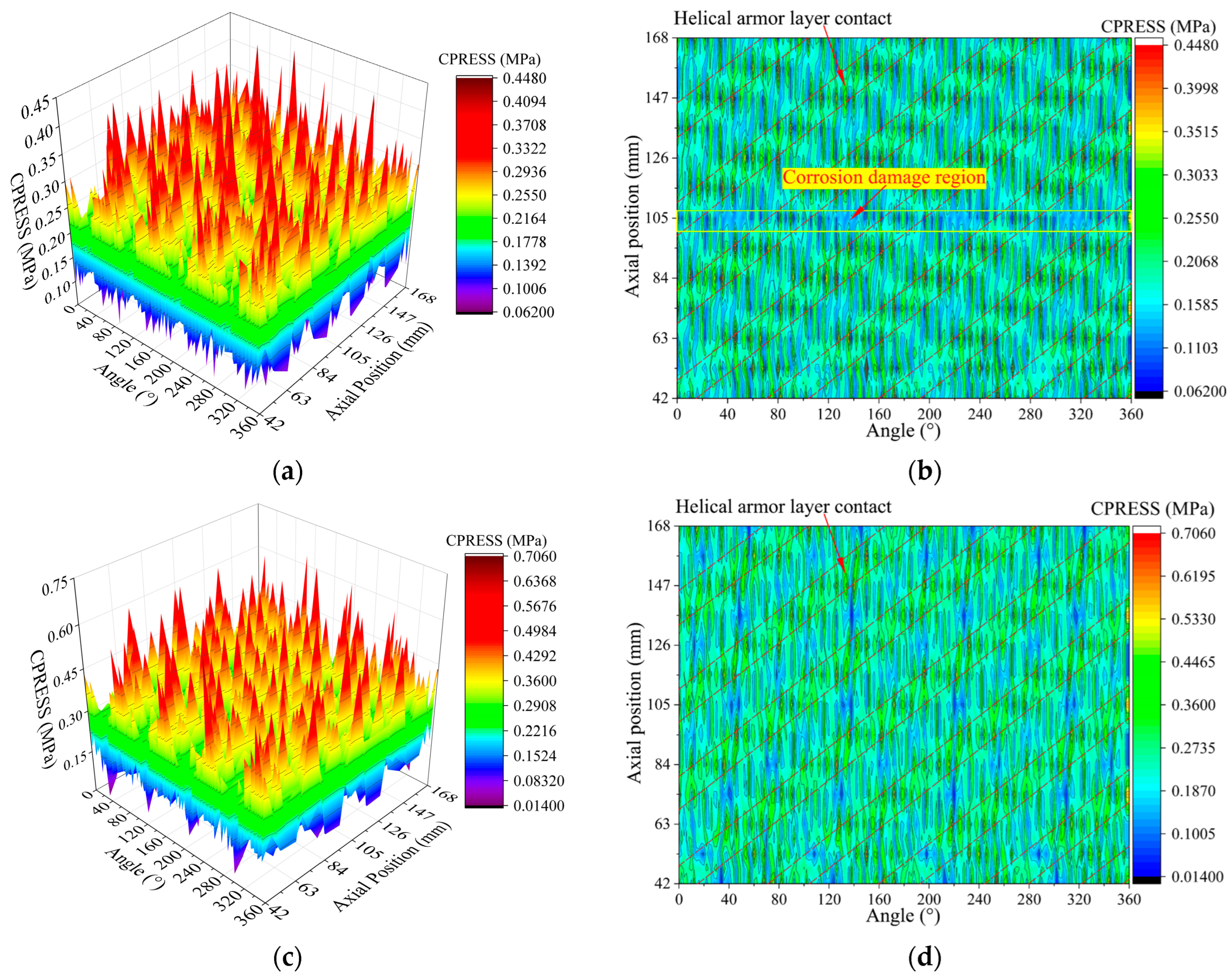

4.2. Results and Analyses

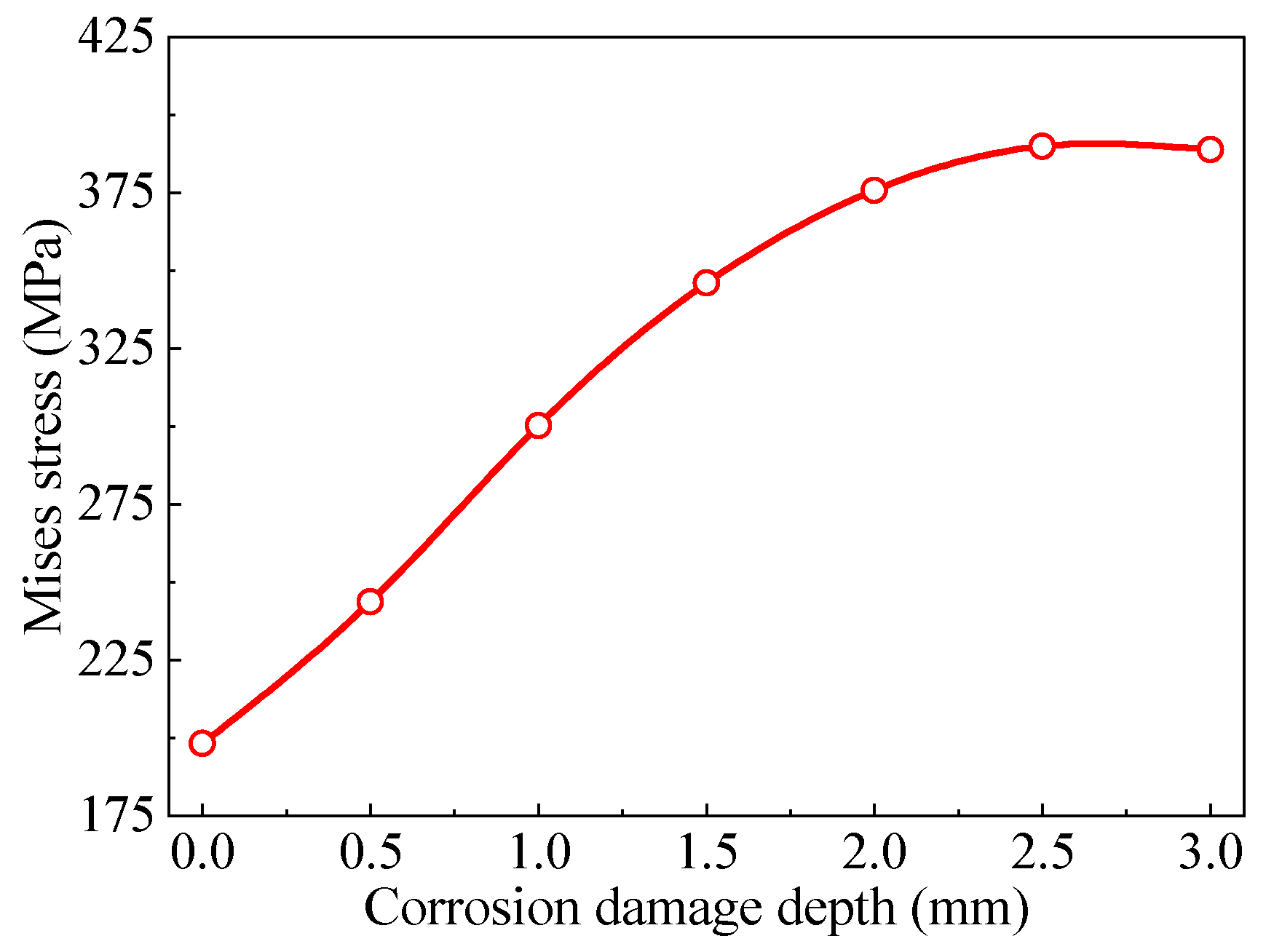

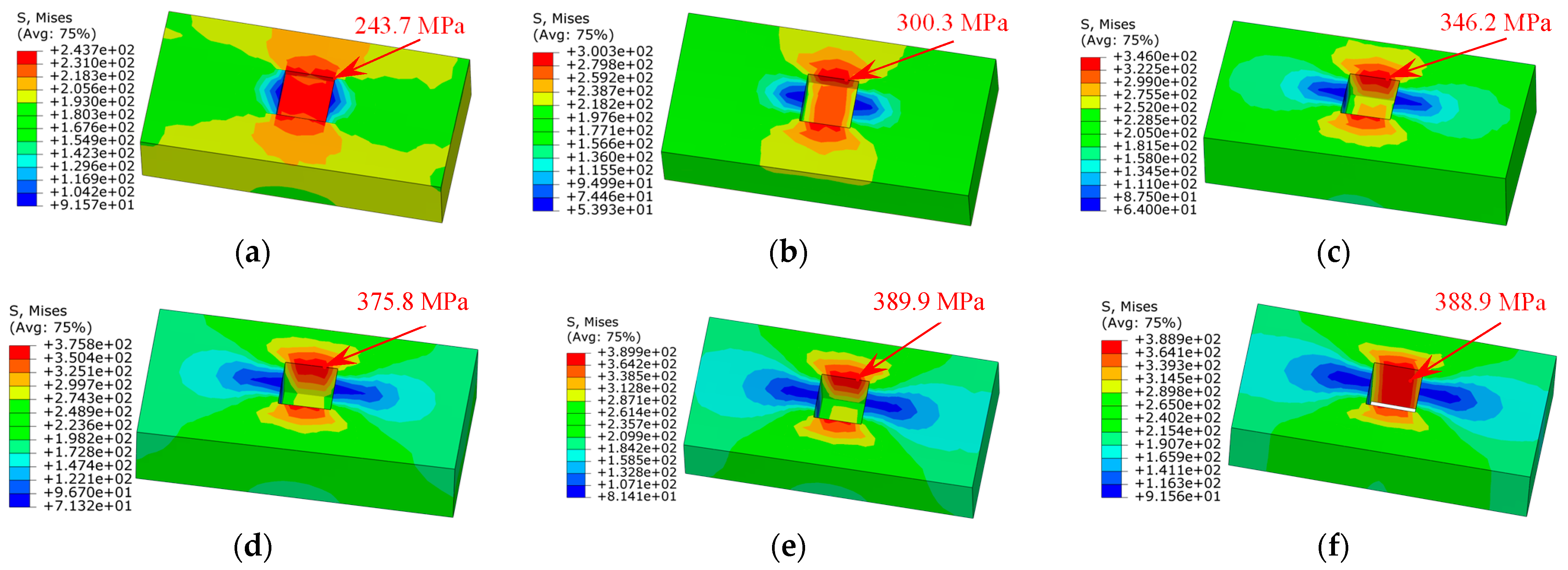

4.3. Effect of Corrosion Damage Depth

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Tensile load is primarily carried by the two tensile armor layers and the conductor layer for the single-core submarine power cable.

- (2)

- Pronounced stress concentration occurs in the corrosion damage region on the outer surface of Layer VII (tensile armor layer). Moreover, in this region, there is a relatively large Mises stress gradient along the cable axial direction. The closer to the corrosion damage region, the greater the Mises stress gradient.

- (3)

- Under the action of a 500 kN tensile load, only the conductor layer (Layer I) and lead sheath layer (Layer III) enter the plastic stage. The plastic strain expands radially from the outside to the inside as the tensile load increases.

- (4)

- For non-penetrating corrosion damage, the maximum Mises stress of the tensile armor layer caused by stress concentration increases with the corrosion damage depth. The tensile stiffness of the SPC decreases as the corrosion damage depth increases, but the decrease is very small, because the corrosion damage area is relatively small compared to the entire cable model dimension.

- (5)

- When the corrosion damage fully penetrates the tensile armor layer, the maximum Mises stress exhibits a slight reduction to 388.9 MPa despite the increased damage severity, which may be due to stress redistribution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Panza, L. Mechanical Performance Study of Submarine Power Cables. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Torino, Turin, Italy, 2020. Available online: https://webthesis.biblio.polito.it/14315/1/tesi.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Wang, W.; Yan, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Ouyang, J.; Ni, X. Failure of submarine cables used in high-voltage power transmission: Characteristics, mechanisms, key issues and prospects. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2021, 15, 1387–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taormina, B.; Bald, J.; Want, A.; Thouzeau, G.; Lejart, M.; Desroy, N.; Carlier, A. A review of potential impacts of submarine power cables on the marine environment: Knowledge gaps, recommendations and future directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benato, R.; Dambone Sessa, S.; Forzan, M.; Marelli, M.; Pietribiasi, D. Core laying pitch-long 3D finite element model of an AC three-core armoured submarine cable with a length of 3 metres. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 150, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Yue, Q. Numerical and experimental analysis of umbilical cables under tension. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2017, 26, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Chen, B. Mechanical behavior of submarine cable under coupled tension, torsion and compressive loads. Ocean Eng. 2019, 189, 106272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Jiang, X.; Hopman, H.; Bai, Y. Mechanical responses of submarine power cables subject to axisymmetric loadings. Ocean Eng. 2021, 239, 109847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, S.; Biglu, M.; von Bock und Polach, F.; Thießen, W. Experimental and numerical investigations of the ultimate strength of two subsea power-transmission cables. Mar. Struct. 2023, 88, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, Z.; Wu, W.; Yan, J. A monitoring strategy for cross-sectional stress distribution of marine unbonded dynamic cables. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Vaz, M.A.; Caire, M. A finite element model for unbonded flexible pipe under combined axisymmetric and bending loads. Mar. Struct. 2020, 74, 102826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lei, Q.; Meng, Y.; Cui, X. Analysis of tensile response of flexible pipe with ovalization under hydrostatic pressure. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 108, 102451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Yuan, S.; Cheng, P.; Bai, Y.; Xu, Y. Mechanical responses of metallic strip flexible pipes subjected to pure torsion. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 86, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukassen, T.V.; Krenk, S.; Glejbøl, K.; Berggreen, C. Non-symmetric cyclic bending of helical wires in flexible pipes. Appl. Ocean Res. 2019, 92, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, J.R.M.; Magluta, C.; Roitman, N.; Campello, G.C. On the extensional-torsional response of a flexible pipe with damaged tensile armor wires. Ocean Eng. 2018, 161, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, J.R.M.; Campello, G.C.; Kwietniewski, C.E.F.; Ellwanger, G.B.; Strohaecker, T.R. Structural response of a flexible pipe with damaged tensile armor wires under pure tension. Mar. Struct. 2014, 39, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornacchia, F.; Liu, T.; Bai, Y.; Fantuzzi, N. Tensile strength of the unbonded flexible pipes. Compos. Struct. 2019, 218, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukassen, T.V.; Gunnarsson, E.; Krenk, S.; Glejbøl, K.; Lyckegaard, A.; Berggreen, C. Tension-bending analysis of flexible pipe by a repeated unit cell finite element model. Mar. Struct. 2019, 64, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.T.; Bahai, H.; Alfano, G. An accurate and computationally efficient small-scale nonlinear FEA of flexible risers. Ocean Eng. 2016, 121, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, F.; Cartraud, P. A computationally efficient finite element model for the analysis of the non-linear bending behaviour of a dynamic submarine power cable. Mar. Struct. 2023, 91, 103465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Hopman, H.; Bai, Y. Bending study of submarine power cables based on a repeated unit cell model. Eng. Struct. 2023, 293, 116606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worzyk, T. Submarine Power Cables: Design, Installation, Repair, Environmental Aspects; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; Volume 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, D.R.; Beckman, R.; Davenport, T.M. Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; Available online: https://cil.nus.edu.sg/publication/submarine-cables-the-handbook-of-law-and-policy-2/ (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Dunham, A.; Pegg, J.R.; Carolsfeld, W.; Davies, S.; Murfitt, I.; Boutillier, J. Effects of submarine power transmission cables on a glass sponge reef and associated megafaunal community. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 107, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Dong, T. Corrosion of copper armor caused by induced current in a 500 kV alternating current submarine cable. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 195, 107144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Tang, W.; Kang, Z.; Geng, H. Numerical study on the axial-torsional response of an unbonded flexible riser with damaged tensile armor wires. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 97, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Lei, Q.; Meng, Y.; Cui, X. Tensile response of a flexible pipe with an incomplete tensile armor layer. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2021, 143, 051702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, J.T.W.; Muren, J. Lifetime assessment of flexible pipes. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 33rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–13 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Engelbreth, K.I. Outer cover damages on flexible pipes: Corrosion and integrity challenges. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 33rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–13 June 2014; Volume 6B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Chen, C.; Zhu, X. Tensile failure behavior of unbonded flexible riser with damaged tensile armor wires. Ocean Eng. 2023, 267, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geers, M.G.D.; Kouznetsova, V.G.; Brekelmans, W.A.M. Multi-scale computational homogenization: Trends and challenges. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2010, 234, 2175–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Hopman, H. RVE model development for bending analysis of three-core submarine power cables with dashpot-enhanced periodic boundary conditions. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartraud, P.; Messager, T. Computational homogenization of periodic beam-like structures. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buannic, N.; Cartraud, P. Higher-order effective modeling of periodic heterogeneous beams. I. Asymptotic expansion method. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2001, 38, 7139–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanasopoulos, N.; Kress, G. Two dimensional modeling of helical structures, an application to simple strands. Comput. Struct. 2016, 174, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, F.; Cartraud, P. Solid and 3D beam finite element models for the nonlinear elastic analysis of helical strands within a computational homogenization framework. Comput. Struct. 2021, 257, 106675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.A.; Durville, D. A mixed stress-strain driven computational homogenization of spiral strands. Comput. Struct. 2023, 279, 106981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.G. A concise finite element model for pure bending analysis of simple wire strand. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2012, 54, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ostoja-Starzewski, M. Finite element solutions to the bending stiffness of a single-layered helically wound cable with internal friction. J. Appl. Mech. 2016, 83, 031008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Hopman, H.; Bai, Y. Development of an effective modeling method for the mechanical analysis of three-core submarine power cables under tension. Eng. Struct. 2024, 317, 118632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Yuan, L.; Yan, J. Modeling the reeling process of offshore pipelines: A theoretical framework based on updated Voce-Chaboche model. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, J.; Grytten, F.; Hopperstad, O.S.; Clausen, A.H. Influence of strain rate and temperature on the mechanical behaviour of rubber-modified polypropylene and cross-linked polyethylene. Mech. Mater. 2017, 114, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Qi, L.; Kang, H.; Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y. The yielding behavior and plastic deformation of oxygen-free copper under biaxial quasi-static and dynamic loadings. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2023, 276, 112333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussolati, F.; Guiton, M.; Guidault, P.A.; Poirette, Y.; Martinez, M.; Allix, O. A new fully-detailed finite element model of spiral strand wire ropes for fatigue life estimate of a mooring line. In Proceedings of the ASME 2019 38th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Glasgow, Scotland, UK, 9–14 June 2019; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systems. ABAQUS Analysis User’s Manual; Version 2021; Dassault Systems Simulia Corp.: Johnston, RI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Component | Thickness (mm) | Radius (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer I | Conductor | - | 23.55 |

| Layer II | Insulation | 21.05 | 44.6 |

| Layer III | Lead sheath | 3.3 | 47.9 |

| Layer IV | PE sheath | 3.6 | 51.5 |

| Layer V | Armor layer | 3 | 54.5 |

| Layer VI | Bedding | 0.5 | 55 |

| Layer VII | Armor layer | 3 | 58 |

| Layer VIII | Outer sheath | 6 | 64 |

| Item | Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Material Type | Poisson Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer I | 1.2 × 105 | Copper | 0.34 |

| Layer II | 350 | XLPE | 0.40 |

| Layer III | 12,000 | Lead | 0.43 |

| Layer IV | 600 | PE | 0.46 |

| Layer V | 2 × 105 | Steel | 0.30 |

| Layer VI | 780 | HDPE | 0.46 |

| Layer VII | 2 × 105 | Steel | 0.30 |

| Layer VIII | 780 | HDPE | 0.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruan, W.; Zhou, C.; Qiu, E.; Zheng, X.; Shang, Z.; Fang, P.; Bai, Y. Structural Response Research for a Submarine Power Cable with Corrosion-Damaged Tensile Armor Layers Under Pure Tension. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112026

Ruan W, Zhou C, Qiu E, Zheng X, Shang Z, Fang P, Bai Y. Structural Response Research for a Submarine Power Cable with Corrosion-Damaged Tensile Armor Layers Under Pure Tension. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. 2025; 13(11):2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112026

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuan, Weidong, Chengcheng Zhou, Erjian Qiu, Xu Zheng, Zhaohui Shang, Pan Fang, and Yong Bai. 2025. "Structural Response Research for a Submarine Power Cable with Corrosion-Damaged Tensile Armor Layers Under Pure Tension" Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 13, no. 11: 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112026

APA StyleRuan, W., Zhou, C., Qiu, E., Zheng, X., Shang, Z., Fang, P., & Bai, Y. (2025). Structural Response Research for a Submarine Power Cable with Corrosion-Damaged Tensile Armor Layers Under Pure Tension. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 13(11), 2026. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmse13112026