1. Introduction

Offshore oil and gas development is a key link in China’s important energy strategic layout [

1,

2]. However, China has not yet fully broken through deep-sea oil and gas development technologies, with shortcomings remaining in core deepwater technologies, and exploration and extraction equipment has not yet formed systematic capabilities. Therefore, the development of marine energy equipment is urgent and necessary [

3]. The subsea dual-channel connector is applied in the subsea flow control module, integrating components such as the throttle valve and flowmeter into a retrievable module, which is connected in series to the internal oil pipeline of the Subsea Christmas tree. Its most important feature is that it seals two oil transmission channels simultaneously within a limited space and in the same body structure [

4].

Since the subsea dual-channel connector is directly connected to the Subsea Christmas tree, it faces the environment of low temperature of external seawater and high temperature of internal oil and gas medium. The sealing structure is subjected to the combined action of external force and temperature load during underwater operation, which can easily cause excessive deformation of the contact surface and affect the sealing performance. Researchers worldwide have conducted a large number of analytical studies on this.

In 2015, Sawa T, Takagi Y [

5] and others used the high-temperature material properties obtained from compression tests to conduct stress analysis and calculate the sealing performance of pipeline flange connections. In 2018, Abdullah O I, Schlattmann J [

6] and others concluded that changes in the distribution of contact stress during the heating phase significantly affect the magnitude and distribution of the generated thermal stress. In 2018, Wang Lu, Chen Xuedong [

7] and others used the thermal–structural coupling method to analyze the changes in axial bolt force, maximum stress and sealing contact stress of the bolted flange connector under steady-state and transient thermal loads. In 2020, Wang Qiang, Hu Yaping [

8] and others developed a leakage and thermal performance analysis method combined with porous media and actual structural models, and numerically simulated the leakage, heat transfer and thermal deformation characteristics of contact finger seals. In 2020, Yun Feihong, Liu Dong [

9] and others established a heat transfer model for the sealed seawater layer of subsea connectors, and determined the relationship between the equivalent thermal conductivity, composite heat transfer coefficient of the seawater layer and temperature. Existing studies provide a theoretical foundation and methodological guidance for establishing heat transfer models, but there is no research on the thermo-structural coupling of clamp-type underwater dual-hole connectors. The operating conditions for single-hole and dual-hole connectors differ, and the effect of temperature on sealing performance also varies. Therefore, further research on clamp-type underwater dual-hole connectors is required.

When the subsea dual-channel connector is in a high-temperature environment for a long time, it will lead to uneven distribution of the internal temperature field, which in turn will cause thermal stress. At the same time, the performance of structural materials may change with temperature, which will affect the sealing performance of the connector. In particular, both oil transmission channels of the subsea dual-channel connector need to withstand high temperatures, making this problem more prominent. The typical operating temperature range for underwater connectors is −55 °C to 125 °C. For the engineering research scenario considered in this paper, the analysis is carried out under the condition where the internal temperature is 150 °C and the external environmental temperature is 3 °C. This paper takes an underwater dual-channel connector with two internal oil transmission channels each of 5.12 inches as the research object, and establishes a heat transfer model for the underwater dual-hole connector; it deduces the heat transfer coefficients of each seawater layer and analyzes the temperature field distribution characteristics of the core components; it uses the ANSYS Heat Transfer module (2023 version) to perform numerical simulations of steady-state heat transfer and transient heat transfer under different operating conditions, and to identify the temperature field distribution patterns of the underwater dual-channel connector under various conditions; and to conduct thermo-structural coupling numerical simulations for both steady-state and transient heat transfer under different operating conditions; finally, it evaluates the sealing performance of the connector under different temperature working conditions.

2. Establishment of Heat Transfer Model Based on Third-Type Boundary Condition

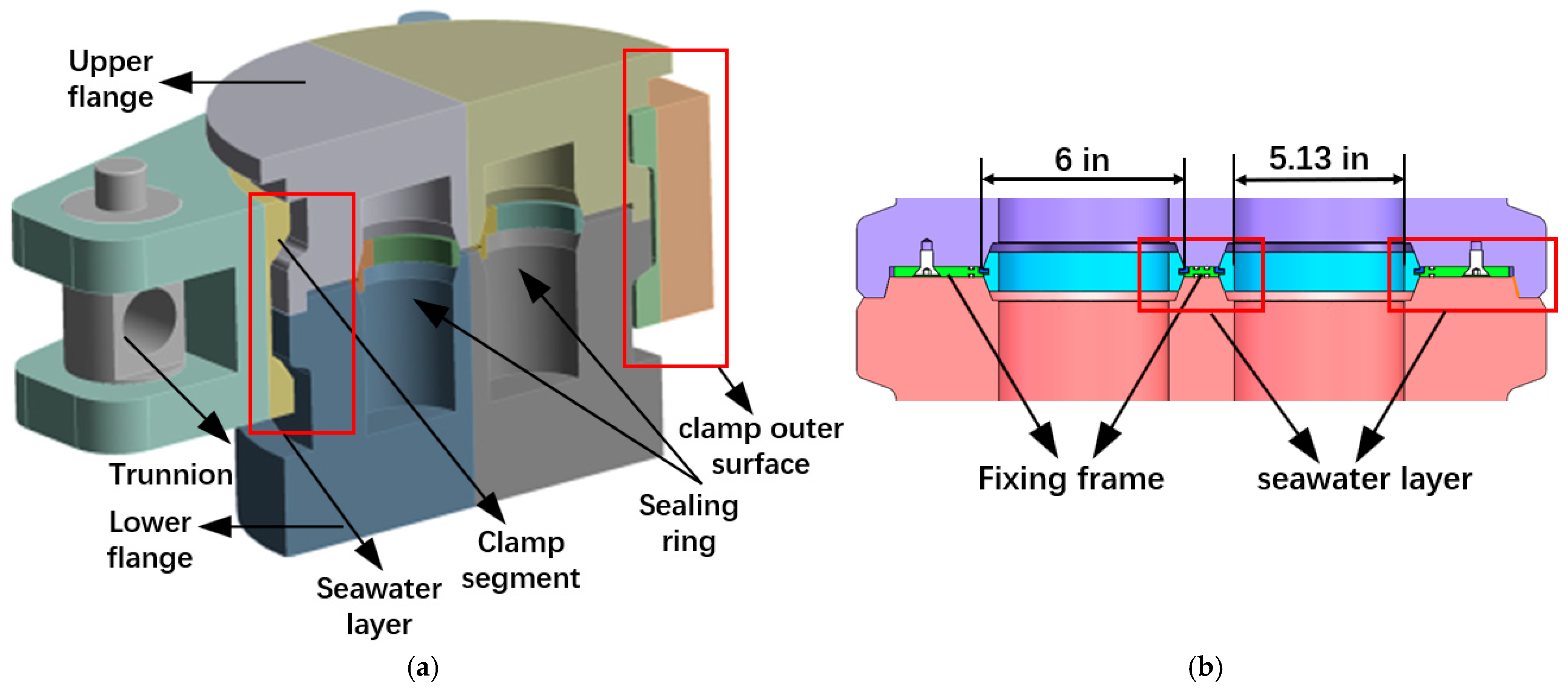

Before constructing the heat transfer model of the connector, a brief description of its core components is provided. The main structure of the connector includes the flanges, a clamp assembly, and a sealing system, with the clamp and sealing structures being critical to ensuring proper operation. The clamp assembly consists of clamp segments, trunnions, and pins, while the sealing system is composed of a sealing ring and a support frame. During operation, the oil–gas mixture is transported through the connector’s two internal channels. Furthermore, the three specific structural heat transfer models involved in this study are illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.1. Heat Transfer Modes

According to the second law of thermodynamics, as long as there is a temperature difference, heat will spontaneously transfer from a high-temperature object to a low-temperature object [

10]. During the operation of the subsea dual-channel connector, its interior is subjected to the high temperature of media such as oil and gas, while its exterior is affected by the low temperature of seawater. Therefore, a temperature difference is formed between the inside and outside of the connector, leading to heat transfer issues.

Heat transfer can be achieved through three main forms: heat conduction, heat convection, and thermal radiation [

11]. These three heat transfer methods usually coexist in many heat transfer processes, which makes the analysis of heat transfer more complex.

Heat conduction: Thermal energy exchange occurs between parts of an object that are in direct contact without relative displacement, and this phenomenon is called heat conduction. In the subsea dual-channel connector, there is direct contact between various components; therefore, the main form of energy transfer between these components is heat conduction. Heat conduction can be expressed using Fourier’s law as follows [

11]:

In the following formula,

is the heat flux density during the conduction process, W/m2:

is the thermal conductivity of an object, W·m−1·K−1;

is the temperature distribution gradient along the heat flow direction, K/m.

Heat convection: When a fluid has macroscopic motion and there is a temperature difference inside it, relative displacement occurs between different parts, leading to mutual heat exchange. The surfaces of components such as the sealing ring, flange and clamp of the subsea dual-channel connector are in direct contact with seawater; therefore, the heat transfer methods are convection and conduction. Heat convection can be expressed using Newton’s law of cooling as follows [

11,

12]:

In the following formula,

is the heat transfer rate during convective heat transfer, W:

is the temperature of the fluid surrounding the object, K;

is the surface temperature at the contact between solid and fluid, K;

is the heat convection coefficient, W·m−2·K−1.

Thermal radiation: Thermal radiation is a process of transferring heat through electromagnetic waves, which does not require a medium. All objects radiate thermal energy to a certain extent, and the intensity depends on their temperature and surface characteristics. The main heat transfer method for the outer surface of the connector in contact with seawater is thermal radiation. Thermal radiation can be expressed using the Stefan–Boltzmann equation as follows [

11]:

In the following formula,

is the heat transfer rate during thermal radiation, W:

is the temperature of the object’s surface, K;

is the surface temperature of objects with a large area, K;

is the emissivity of the object’s surface, ;

is the shape factor from surface 1 to surface 2 of the object;

is the surface area of the smaller object, m2;

is the Stefan–Boltzmann Constant, 5.67 × 10−8 W·m−2·K−4.

2.2. Heat Transfer Boundary Conditions

Heat transfer boundary conditions refer to the conditions that the interface must satisfy during the heat conduction process, and they can be divided into three categories [

13].

First-type boundary condition: When the temperature value on the object boundary or the function of temperature changing with time and position is taken as a known condition, it can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

T is the temperature of the object, K;

represents the heat transfer boundary conditions;

is the function of temperature variation with time and position.

Second-type boundary condition: The heat flux value on the boundary of the object or the function of heat flux varying with time and position is a known condition, which can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

is the known heat flux, W/m2;

is the known heat flux function.

Third-type boundary condition: The heat transfer coefficient and temperature of the fluid flowing over the object are known conditions, which can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

is the temperature of the fluid medium, K;

is the heat transfer coefficient, W·m−1·K−1.

In the heat transfer analysis of an underwater dual-channel connector, considering that the temperatures of the internal medium and the external seawater are known, both heat conduction and heat convection occur simultaneously during the oil and gas transportation process. Therefore, simply applying the first-type boundary condition for heat transfer is not appropriate. In addition, since the heat flux of the connector cannot be directly determined, the second-type boundary condition is also not applicable. Finally, the seawater temperature in the connector’s working environment and the temperature of the medium flowing through the interior are known, and taking into account that the heat transfer coefficients of the internal and external fluids are known, the underwater dual-channel connector thus satisfies the third-type boundary condition [

14,

15].

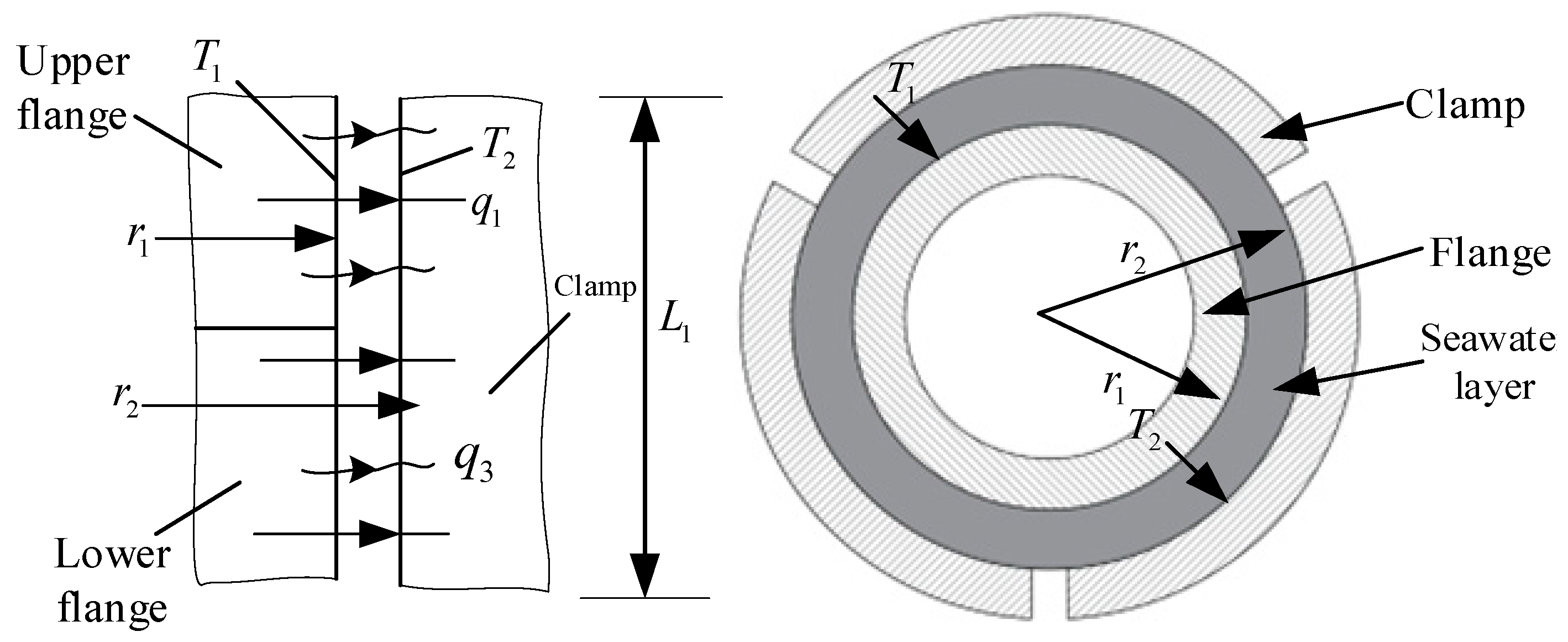

2.3. Heat Transfer Model of Seawater Layer Between Flange and Clamp Segment

Figure 2 displays the two-dimensional view of the connection between the clamp and flange after preloading. The heat transfer methods between the flange and clamp segment include three types: thermal conduction

, convective heat transfer

and thermal radiation

[

2,

16]. Since the flow velocity of seawater between the clamp segment and the flange is extremely low, convective heat transfer can be neglected, and only thermal conduction and thermal radiation are considered [

17]. However, neither the inner surface of the clamp segment nor the outer surface of the flange is a flat surface, which may cause other surfaces to interfere with energy exchange. To accurately describe the energy transfer efficiency between the two surfaces, the view factor is introduced; the value of the view factor mainly depends on the geometric state of the two heat transfer surfaces, and it only represents the percentage of energy transfer between the two surfaces, without involving the energy absorption capacity of the surfaces. For the heat transfer model between the flange and the clamp, it is simplified to the heat transfer problem between two concentric cylinders, and the view factor is expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

r1 is the radius of the outer surface of the flange, m;

r2 is the radius of the inner surface of the clamp segment, m.

; ; ; .

Considering the influence of multiple absorption and radiation in the gray body system on heat transfer, to more accurately describe its energy exchange characteristics, the system emissivity is introduced, which can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

is the emissivity of the flange, 0.8;

is the emissivity of the clamp segment, 0.8.

Then, the heat transfer quantity generated by thermal conduction

and the heat transfer quantity generated by thermal radiation

between the flange and the clamp can be expressed as follows:

If we introduce the equivalent thermal conductivity

, according to the third-type boundary condition, heat transfer between the flange and the sealing ring

can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula:

λk2 is the thermal conductivity of seawater at temperature T2, W·m−1·K−1;

T1 is the temperature of the outer surface of the flange, K;

T2 is the temperature of the inner surface of the clamp segment, K;

C0 is the blackbody radiation coefficient, 5.67 W·m−2·K−4.

Then, the equivalent thermal conductivity of seawater between the flange and the clamp segment can be expressed as follows:

2.4. Heat Transfer Model of Seawater Layer Between Sealing Ring and Fixing Frame

Figure 3 shows the simplified model of the seawater layer between the sealing ring and the flange. Considering the low fluidity of seawater between them, convective heat transfer will be ignored, and only the effects of thermal conduction and thermal radiation will be taken into account. The equivalent thermal conductivity is introduced according to third-type boundary condition

and the heat transferred between the sealing ring and the flange can be obtained

:

In the following formula,

λk4 is the thermal conductivity of seawater at temperature t4, w·m−1·k−1;

T3 is the temperature of the outer surface of the sealing ring, k;

T2 is the temperature of the inner surface of the flange, k.

Then, the equivalent thermal conductivity of seawater between the sealing ring and the flange can be expressed as follows:

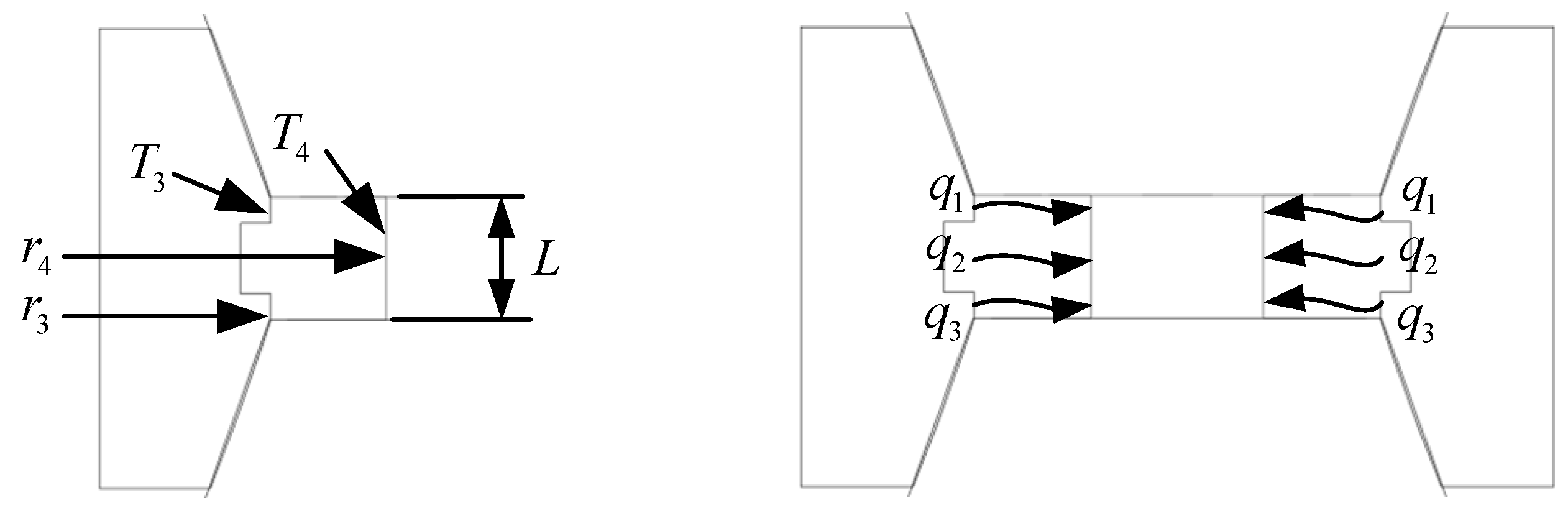

2.5. Heat Transfer Model of the Outer Surface of the Clamp

The outer surface of the clamp segment is directly exposed to seawater. Considering the strong fluidity of seawater in this area, the heat transfer process between it and seawater is dominated by thermal radiation and thermal convection. The heat transfer diagram is shown in

Figure 4. The heat flow loss caused by thermal convection can be expressed as follows:

In the following formula,

is the convective heat transfer coefficient of seawater;

A is the area of the outer surface of the clamp, m2;

T5 is the temperature of the outer surface of the clamp segment, k;

T6 is the temperature of seawater, k.

The heat loss caused by thermal radiation can be expressed as follows:

If we introduce the composite heat transfer coefficient he, then the heat loss can be expressed as follows:

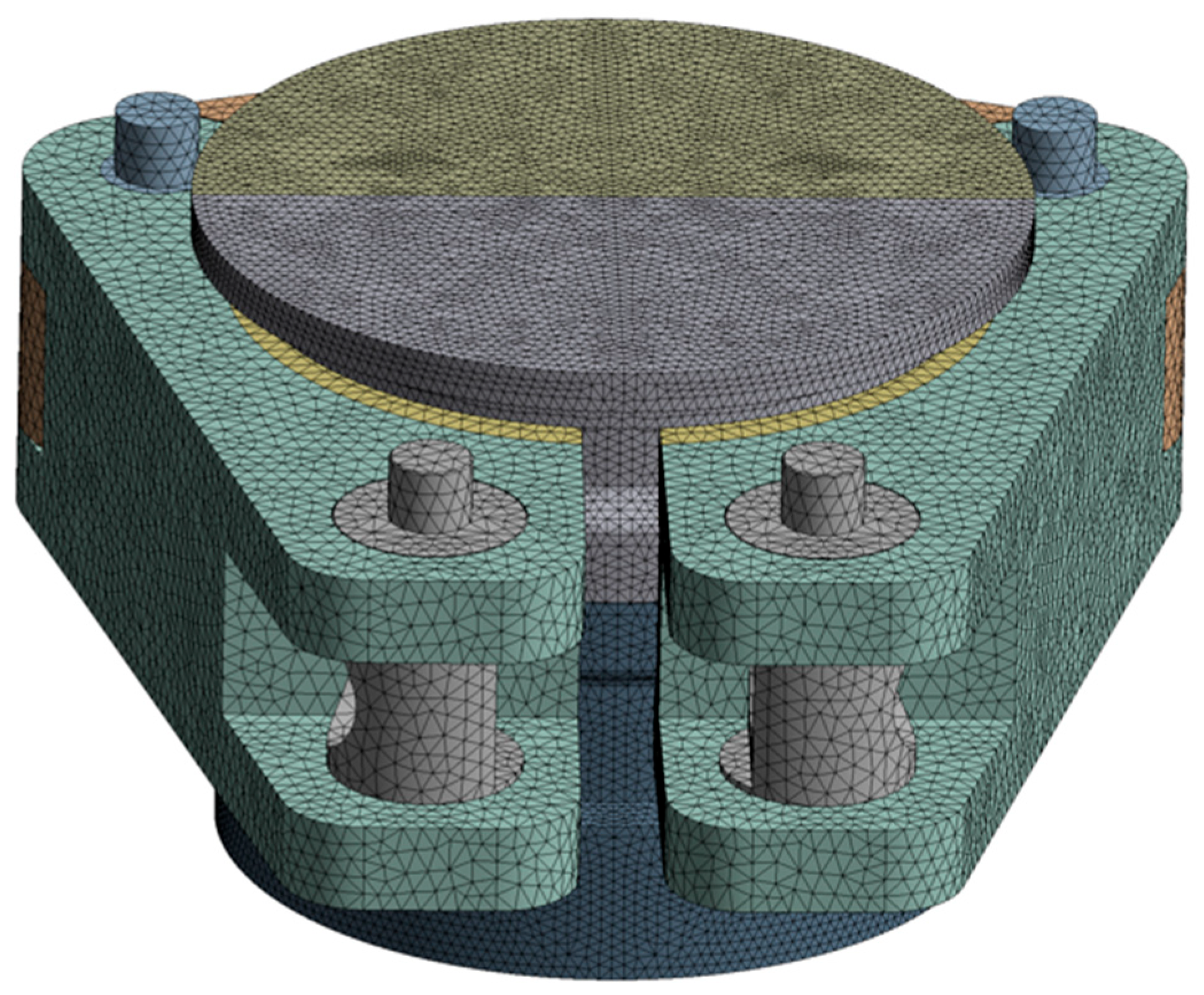

4. Thermal–Structural Coupling Analysis Combined with Simulation

To verify that the underwater dual-hole connector can maintain an effective seal under the temperature field analyzed previously, an axial displacement was first applied as the initial load based on the prior heat transfer model to achieve a preloaded state [

19,

20]. Then, internal pressure and end loads were applied to the dual holes inside the connector to simulate the actual conditions when oil and gas are introduced. In addition, the “body load” corresponding to the temperature of each node of the underwater dual-hole connector obtained from the temperature field analysis was converted into a static load, which was then applied to the components together with the pressure and preload force, thereby obtaining the thermal–structural coupled stress state of the underwater dual-hole connector [

21,

22]. Thermal expansion coefficients of subsea dual-channel connector materials is shown in

Table 2.

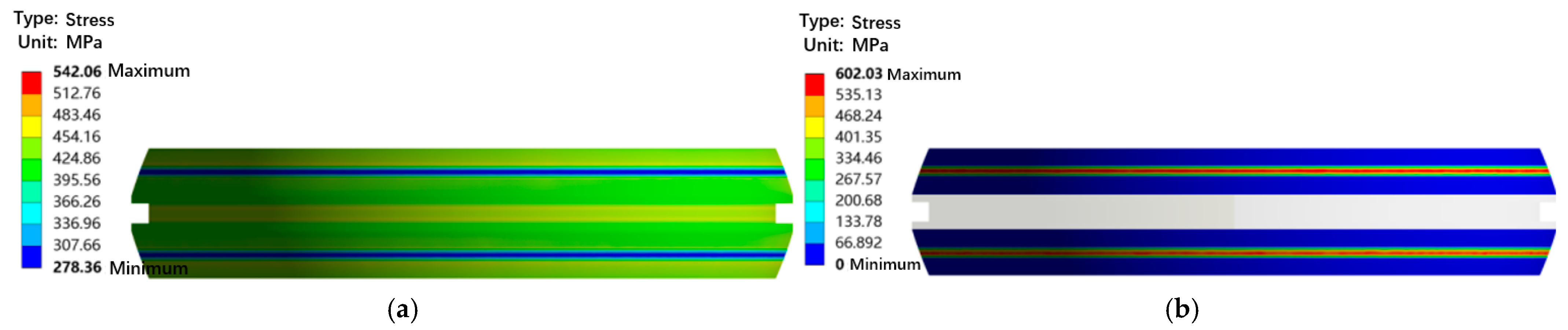

The stress and contact stress distributions of the metal sealing ring of the subsea dual-channel connector under the preload condition are shown in

Figure 12. It can be seen from the figure that the maximum equivalent stress of the metal sealing ring is 542.06 MPa, which is located at its groove; the stress distribution of the two sealing rings is uniform and basically consistent; the maximum equivalent stresses of the upper and lower flanges are 316.54 MPa and 291.44 MPa, respectively; the maximum contact stress of the sealing ring is 602.03 MPa. The thermal–structural coupling analysis in this section adopts solid models. To reduce the amount of calculation, only the upper and lower flanges and sealing rings are subjected to thermal–structural coupling simulation analysis.

To simulate the full-process effect of the temperature field on the structure, numerical simulation of transient coupling stress is carried out [

23,

24]. The application methods of node temperature and static force are consistent with those in the steady-state simulation. First, the simulation results of the subsea dual-channel connector under preload conditions are solved, then the temperature and pressure load under different working conditions are applied in sequence, and finally the variation law of its sealing performance under the action of transient temperature field and pressure is analyzed.

4.1. Analysis of Temperature Rise and Pressure Rise Condition

The temperature rise and pressure rise condition is used to simulate the sealing performance of the subsea dual-channel connector when the oil and gas pressure and temperature inside it rise synchronously after the wellhead of the Subsea Christmas Tree is opened.

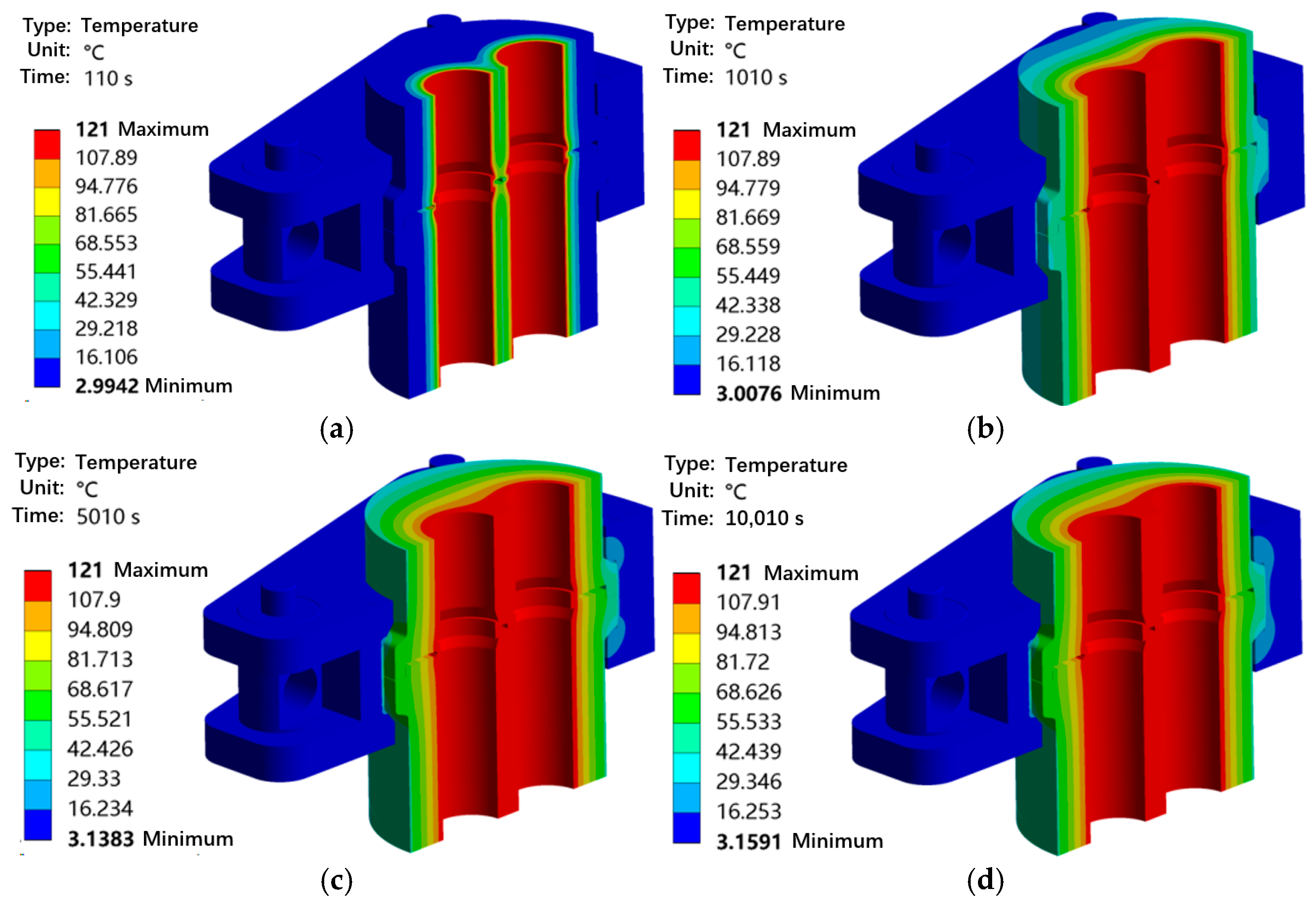

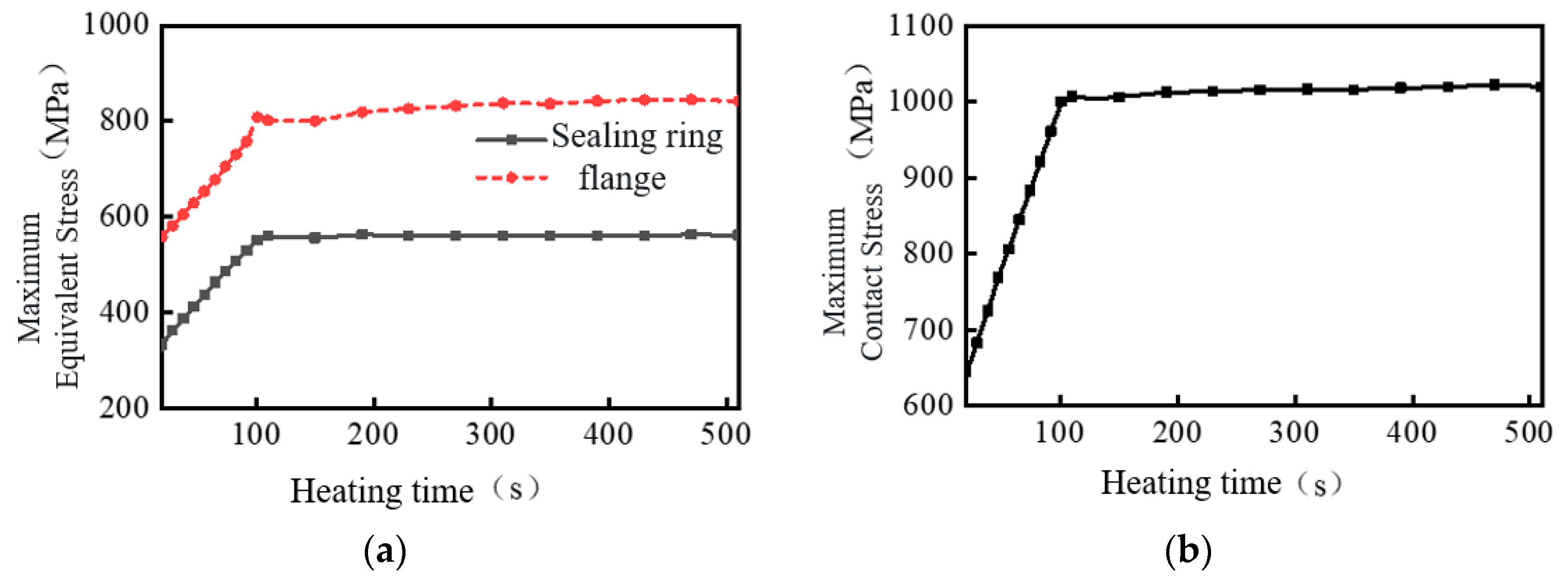

It can be seen from

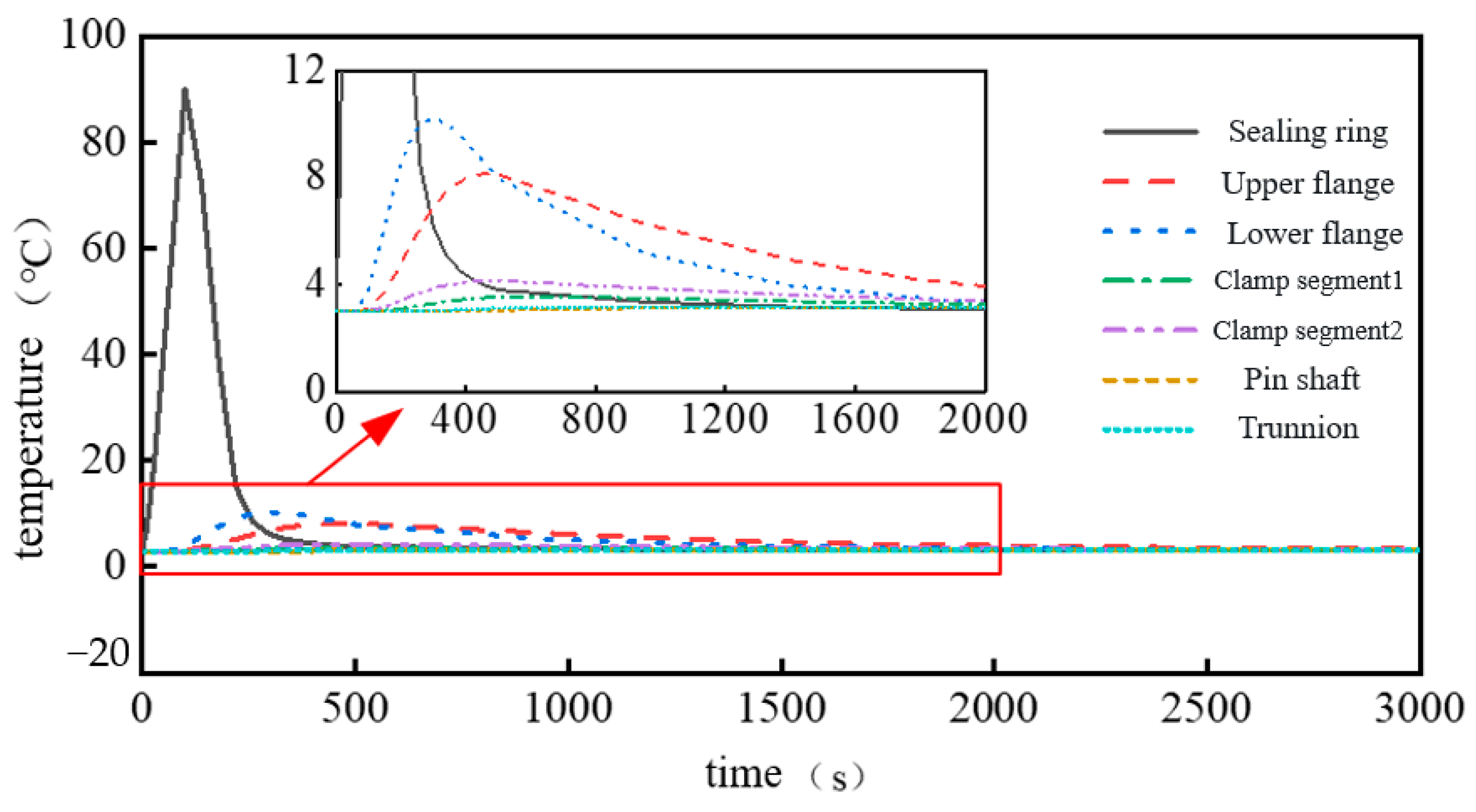

Figure 13 that the period from 0 to 10 s is the preload state, and the period from 10 to 110 s is the temperature and pressure rise stage. During 100 s, the internal pressure of the subsea dual-channel connector rises from 0 to 69 MPa, and the inner wall temperature rises from 3 °C to 121 °C. During this stage, the maximum equivalent stress of the sealing ring gradually increases; when the temperature rises to 121 °C, the maximum equivalent stress of the metal sealing ring is 801.07 MPa (which is less than the yield strength of Inconel 718 material), and it is located at the contact position between the flange and the sealing ring, with the maximum contact stress being 1006.7 MPa. Compared with the preload state, under the action of temperature and pressure, the maximum stress of the sealing ring increases by approximately 200 MPa, the maximum contact stress increases by approximately 404 MPa, and the flange stress is 558.71 MPa (which is higher than that in the preload state). This is because during heating and pressurization, the temperature difference of the sealing ring gradually increases, and it expands outward under the combined action of temperature and pressure, resulting in further compression between the sealing ring and the flange, and thus a rapid increase in stress. Additionally, the constraints at both ends of the flange in the simulation lead to a certain degree of overestimation of the results 110–510 s. During the period from 110 s to 510 s, the maximum equivalent stress and contact stress of the sealing ring and flange continue to increase, but the growth rate decreases and gradually flattens out. This is because the temperature difference between the inside and outside of the sealing ring gradually decreases to a stable state at this time, resulting in a reduction in the stress growth rate. In summary, although the subsea dual-channel connector is significantly affected by temperature and pressure, it can still meet the sealing requirements.

4.2. Analysis of Temperature Drop and Pressure Reduction Condition

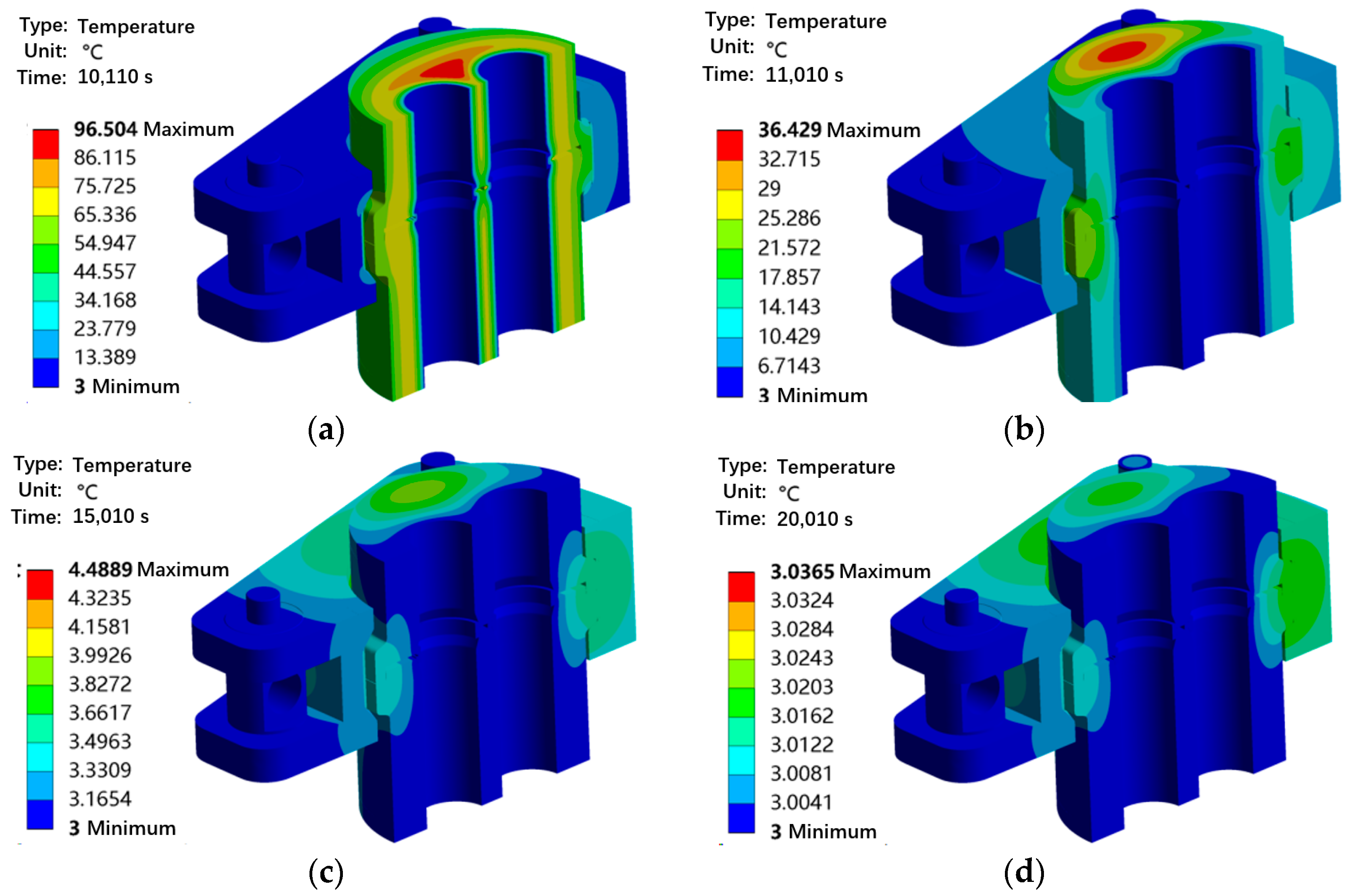

The temperature dropping and pressure reduction condition is used to simulate the change in the sealing performance of the connector when the oil and gas pressure and temperature decrease synchronously after the wellhead of the Subsea Christmas Tree is closed.

Figure 14 shows the coupling stress analysis results under different temperature drop and pressure reduction times. The period from 0 to 100 s is the temperature drop and pressure reduction stage. During 100 s, the internal pressure of the subsea dual-channel connector drops from 69 MPa to 0 MPa, and the inner wall temperature drops from 121 °C to 3 °C. Within 0–100 s, the equivalent stress and contact stress of the sealing ring and flange decrease rapidly; when the temperature drops to 3 °C, the maximum equivalent stress of the sealing ring is 669.28 MPa (located at the contact position between the flange and the sealing ring), the maximum contact stress is 578.42 MPa, and the flange stress is 558.71 MPa, all of which are much higher than those in the preload state (100–500 s). During the period from 100 s to 500 s, the maximum equivalent stress and contact stress of the sealing ring and flange continue to decrease, but the rate of reduction gradually decreases. This is because the temperature difference between the inside and outside of the sealing ring gradually decreases at this time, leading to a reduction in the stress change rate. When the temperature drops to 500 s, the maximum equivalent stress of the sealing ring is 562.79 MPa (still greater than that in the preload state), and the contact stress is 555.98 MPa (lower than that in the preload state). This is due to the plastic deformation occurring on the surface of the sealing ring, which cannot fully recover its initial shape after the load disappears. For the connector as a whole, although the sealing ring undergoes plastic deformation, the contact stress analysis indicates that it still meets the sealing requirements.

4.3. Analysis of Temperature and Pressure Impact Condition

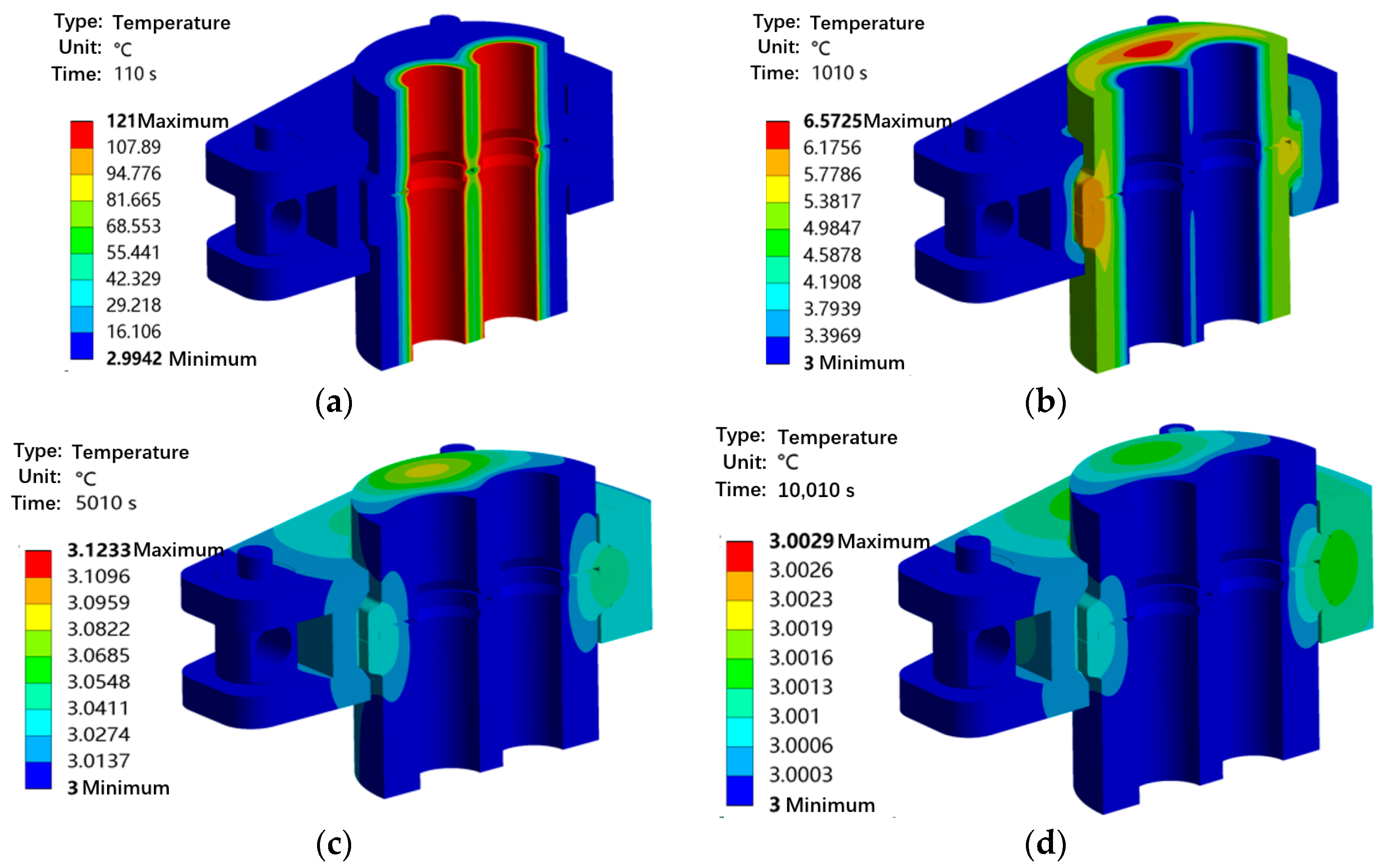

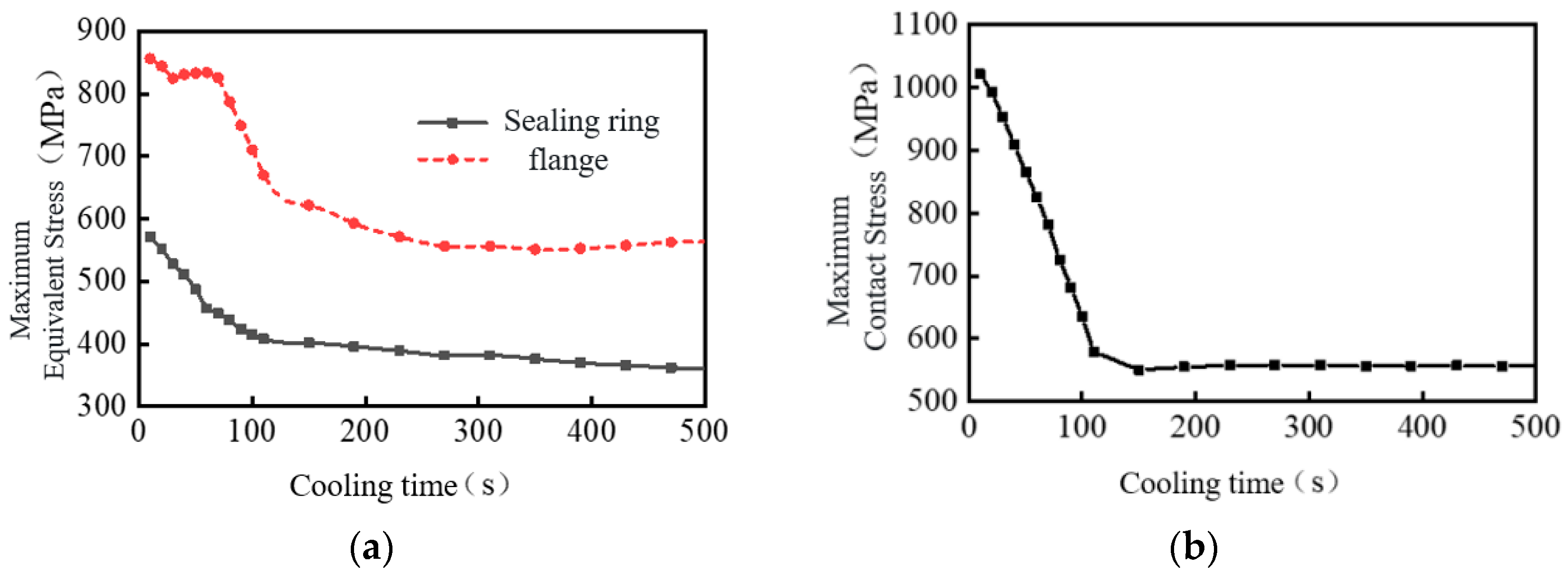

The temperature and pressure impact condition is used to simulate the change in the sealing performance of the connector when the wellhead of the Subsea Christmas Tree is closed immediately after being opened.

Figure 15 shows the coupling stress analysis results under the temperature and pressure impact condition: the period from 0 to 100 s is the temperature rise and pressure rise stage. During 100 s, the internal pressure of the subsea dual-channel connector increases from 0 MPa to 69 MPa, and the inner wall temperature rises from 3 °C to 121 °C; 100–200 s; the period from 100 s to 200 s is the temperature drop and pressure reduction stage. During 100 s, the internal pressure drops from 69 MPa to 0 MPa, and the inner wall temperature decreases from 121 °C to 3 °C. Within 0–100 s, the equivalent stress and contact stress of the sealing ring and flange rapidly increase to their peak values; when the temperature rises to 121 °C, the maximum equivalent stress of the sealing ring is 789.07 MPa (located at the contact position between the flange and the sealing ring), the maximum contact stress is 996.81 MPa, and the flange stress is 549.93 MPa, all of which are much higher than those in the preload state 100–200 s. During the period from 100 s to 200 s, the maximum equivalent stress and contact stress of the sealing ring and flange decrease rapidly; after 200 s, the rate of reduction gradually decreases. This is because the temperature difference between the inside and outside of the sealing ring gradually decreases at this time, leading to a reduction in the stress change rate. When the temperature drops to 500 s, the maximum equivalent stress of the sealing ring is 563.39 MPa (greater than that in the preload state), and the contact stress is 571.16 MPa (lower than that in the preload state). The underlying mechanism is the same as previously discussed for the pressure reduction scenario. Under this working condition, the sealing ring can still maintain good sealing performance. In long-term operation, sudden changes in temperature and pressure can cause significant fluctuations in the performance of lens-type sealing rings. Consequently, repeated heating–cooling cycles are likely to induce fatigue wear, making it necessary to avoid such conditions to ensure the reliability and longevity of the sealing system.

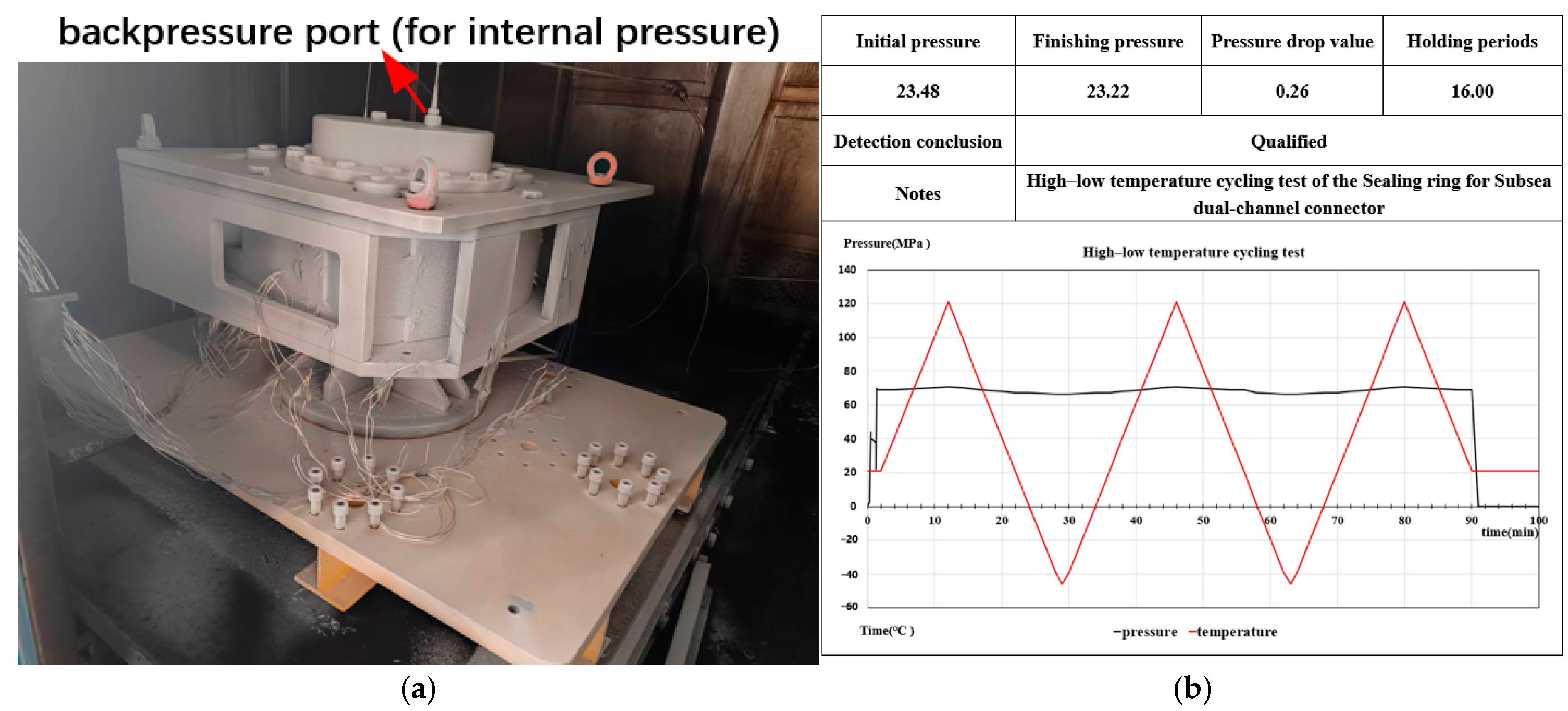

4.4. Temperature Cycle Test

This test was conducted in a high–low temperature cycling chamber to verify the sealing performance of the underwater connector under high and low temperature conditions. The procedure strictly followed the requirements for high–low temperature cycling tests specified in Appendix F1.11.3 of the API 6A (2018 edition) [

25] standard, focusing on the connector’s sealing reliability under pressure within the temperature range of −46 °C to 121 °C.

The test parameters and operational steps were as follows:

Nitrogen gas was introduced into the connector through its preset backpressure port until the internal pressure stabilized at 68.9 MPa (rated working pressure), at which point the gas supply was stopped.

High-temperature gas was then released into the cycling chamber to adjust the internal temperature. Using built-in temperature sensors to monitor changes in real time, the temperature was controlled to rise gradually from room temperature to 121 °C, and then slowly decrease to –46 °C, completing one full high–low temperature cycle.

This process was repeated three times to complete all cycling tests. During the experiment, internal pressure data were collected in real time via the sensor installed on the backpressure port, and temperature data were recorded simultaneously using temperature sensors mounted on the inner walls of the connector’s dual holes. Corresponding temperature–time and pressure–time curves were generated, and the test data graphs are shown in

Figure 16.

Previous analysis indicates that the core criterion for evaluating the sealing performance of the O-ring is the magnitude of the sealing contact stress: when the contact stress meets the design threshold, the connector can achieve an effective seal. However, in actual high–low temperature cycling tests, real-time and accurate direct measurement of the O-ring contact stress is difficult due to limitations in the testing environment and sensor technology. Based on this, the present study adopts an indirect characterization approach to define the sealing qualification criterion: after the internal pressure of the connector reaches 68.9 MPa, if the pressure dropping during the entire high–low temperature cycling process does not exceed 3% [

25] of the rated working pressure (68.9 MPa), the connector’s sealing performance is deemed reliable.

The rationality of this evaluation criterion derives from the essential requirement of sealing performance: the goal of reliable connector sealing is to prevent leakage of the oil and gas medium transported inside, and medium leakage is inevitably accompanied by an abnormal drop in internal pressure. Thus, if the internal pressure drop can be maintained within the allowable range during the test, it can indirectly prove that no leakage channels have formed in the sealing ring, and the sealing state is qualified. Analysis of the test data graphs shows that the underwater dual-hole connector maintained a stable internal pressure throughout the temperature range of −46 °C to 121 °C, with the pressure drop meeting the qualification standard, confirming its sufficiently reliable and effective sealing capability.

5. Conclusions

Based on heat transfer theory, this paper simplifies the heat transfer model of the subsea dual-channel connector, establishes a seawater model between various components, and uses the ANSYS heat transfer module to numerically simulate its temperature field, obtaining the temperature field distribution under different working conditions. Furthermore, combined with the solved temperature field distribution, thermal–mechanical coupling studies under various working conditions are carried out to evaluate the sealing performance of the subsea dual-channel connector under different temperature conditions.

- (1)

Aiming at the heat transfer problem during the working process of the subsea dual-channel connector, an equivalent heat transfer model was established for the lens-type sealing ring and flange, between the flange and the clamp segments, and the seawater layer on the outer surface of the clamp segments. The relationships between the equivalent thermal conductivity, composite heat transfer coefficient and temperature were obtained through solving the model.

- (2)

Steady-state temperature field analysis and transient temperature field analysis under temperature rise, temperature drop, and temperature impact conditions were carried out on the subsea dual-channel connector. The simulation results show that in the steady-state temperature field, the temperature field distribution of each component gradually decreases from the inside to the outside. In the transient heat transfer analysis, during the process of the temperature gradually flattens out, both the sealing ring and the flange are significantly affected by temperature, whether in the case of temperature rise or temperature drop.

- (3)

A thermal–structural coupling numerical simulation was conducted on the subsea dual-channel connector under multiple working conditions. The analysis shows that when the inner wall temperature and pressure rise, the connector material expands due to heat, resulting in an increase in the sealing contact stress and simultaneous sliding of the sealing surface; when the temperature and pressure drop, the material contracts due to cold, leading to a decrease in the sealing contact stress; when there are sudden changes in temperature and pressure, the sealing surface slides repeatedly to accommodate the deformation, which may cause wear of the sealing surface. Long-term operation may easily lead to sealing failure and even leakage risks.

- (4)

Sealing performance tests were conducted on the sealing ring of the underwater dual-hole connector under temperature cycling conditions, with pressure changes monitored simultaneously during the test. The results show that as the temperature increased, the internal pressure of the connector increased accordingly; as the temperature decreased, the internal pressure also decreased in tandem. The overall pressure rise and drop did not exceed 3% of the rated working pressure. Based on the above test results, it can be concluded that under the three conditions of temperature cycling, heating, and cooling, the sealing performance of the underwater dual-hole connector meets the requirements, can satisfy the sealing demands in actual working scenarios, and further verifies its sealing reliability during temperature changes.

In subsequent research, a comparative analysis will be conducted on the influence of thermal radiation, focusing on its effects on the heat transfer characteristics and sealing performance of the connector within the temperature range of −46 °C to 121 °C, in order to determine whether this factor can be neglected. Furthermore, the impact of temperature changes on the lifespan of key sealing components and their fatigue fracture behavior under long-term operating conditions will be investigated, providing support for the design of long-term reliable connectors.