1. Introduction

The Yangtze River Estuary (YRE) is the largest estuary in China, and the discharge is only less than that of the Amazon River and the Congo River, ranking third in the world. Under the combined influence of runoff and tide, the YRE has developed a unique morphology characterized by three distributaries and four passages to the sea [

1]. Tidal reach is affected by both upstream runoff and downstream tidal action. Within this tidal reach, the tidal current limit refers to the point furthest upstream along the river where the tide encounters resistance from both the riverbed and the opposing downstream flow of freshwater. At this location, the velocity generated by the incoming tide counterbalances the river’s flow velocity, causing the net upstream movement of tidal water to cease. It marks the upper boundary of significant tidal hydrodynamic influence. Further upstream, the tidal limit signifies where the tidal wave’s energy is ultimately depleted, causing the tidal range to diminish to zero. It represents the absolute farthest extent of periodic tidal water level fluctuations. Both the tidal limit and the tidal current limit are dynamic boundaries, shifting in response to upstream discharge volume, tidal intensity, and seasonal variations. The tidal limit of the Yangtze River is generally near Datong (117°37′ E, 30°46′ N), Anhui province [

2,

3]. After analyzing the hydrological data of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River from 2007 to 2016, Shi et al. concluded that the tidal limit extends up to approximately 900 km upstream of the estuary during extreme dry seasons and retreats to 640–665 km upstream during flood seasons [

4]. The tidal current limit is near Jiangyin [

5,

6]. Under the combined influence of tide and runoff, the average water level within this tidal reach (from the estuary to the tidal limit) gradually rises further upstream, while the change in water level fluctuation amplitude decreases [

7].

Sea level change in a certain region is mainly driven by changes in sea water mass (land glacier, storage loss), specific volume (sea water temperature, salinity), and seabed elevation. Sea level rise poses multifaceted threats, including the flooding of coastal zones [

8,

9], saltwater intrusion [

10,

11], and even an increased risk of geological hazards [

12,

13]. At the global scale, Cazenave et al. showed that about 30% of climate-induced sea level change is attributed to ocean temperature changes, while the melting of land glaciers accounted for about 55% [

14]. Horton et al. predicted that under a global temperature rise of 4.5 °C in 2100, SLR would be more than 1 m [

15]. In the East China Sea, specific volume is affected by Yangtze River runoff and Kuroshio current [

16], playing a dominant role in the regional sea level change, which presents obvious periodic variations [

17]. Significant anthropogenic alterations in the lower Yangtze basin have dramatically altered sediment properties, leading to intensified riverbed scour and increasing estuary water depth [

18]. The morphological shift transformed the estuarine tidal wave from a dissipative progressive wave into a standing wave system, enhancing susceptibility to tidal amplification [

19]. Broader mechanistic research includes Chen’s analysis of dominant sea level change modes using AVISO satellite altimeter data, alongside modeling studies investigating long-term trends and their impacts on the North Pacific Ocean [

20]. Focusing on the impact of the Yangtze River on the Yangtze estuary, Kuang et al. [

21] adopted Mike 21 to establish a hydrodynamic model of the East China Sea, evaluating seasonal and long-term changes under characteristic discharge scenarios (75th percentile, median, 25th percentile and multi-year monthly average discharge during 1950–2011). Simulations indicate that a 20,000 m

3/s increase in Yangtze River discharge typically induced a 5–10 mm sea level rise across most areas of Hangzhou Bay.

A recent study on the environmental impacts of SLR mainly integrate field measurements with numerical models. Wang et al. used MIKE 21 to compare the effect of SLR, land subsidence, and water depth changes on the coastal environment in the Shanghai coastal area [

22]. Liu applied a three-dimensional EFDC hydrodynamic model in the Pearl River Estuary, demonstrating that SLR intensifies estuarine water column stratification [

23,

24]. Projected salinity intrusion lengths under 1.0 m SLR would increase by 21.37, 9.64, 9.75, and 4.82 km at the Humen, Jiaomen, Hongqili, and Hengmen outlets, respectively. Chen simulated the influence of a 100 cm SLR on the ebb and flood duration within the upper YRE using a two-dimensional tidal model under flood, dry, and average annual discharge conditions [

25]. Yan used the SPRC (source–pathway–receptor–consequence) model combined with MIKE 21 to assess the potential combined impacts of SLR and storm surges [

26].

Previous studies have extensively addressed SLR effects on estuarine saline intrusion and tidal currents, few studies have specifically investigated the impacts of SLR on tidal wave propagation characteristics. In this paper, a two-dimensional hydrodynamic model of the Yangtze Estuary is established using MIKE 21 to examine changes in tidal wave propagation characteristics in the tidal reach of the Yangtze River under different discharge conditions.

3. Model Setup

3.1. Model Introduction

MIKE is a modeling system developed by the Danish Hydraulic Institute (DHI), which has strong post-processing capability [

27]. It provides a comprehensive framework integrating specialized numerical modules, and is suitable for hydrodynamic environment simulation across diverse conditions.

3.2. Computational Domain

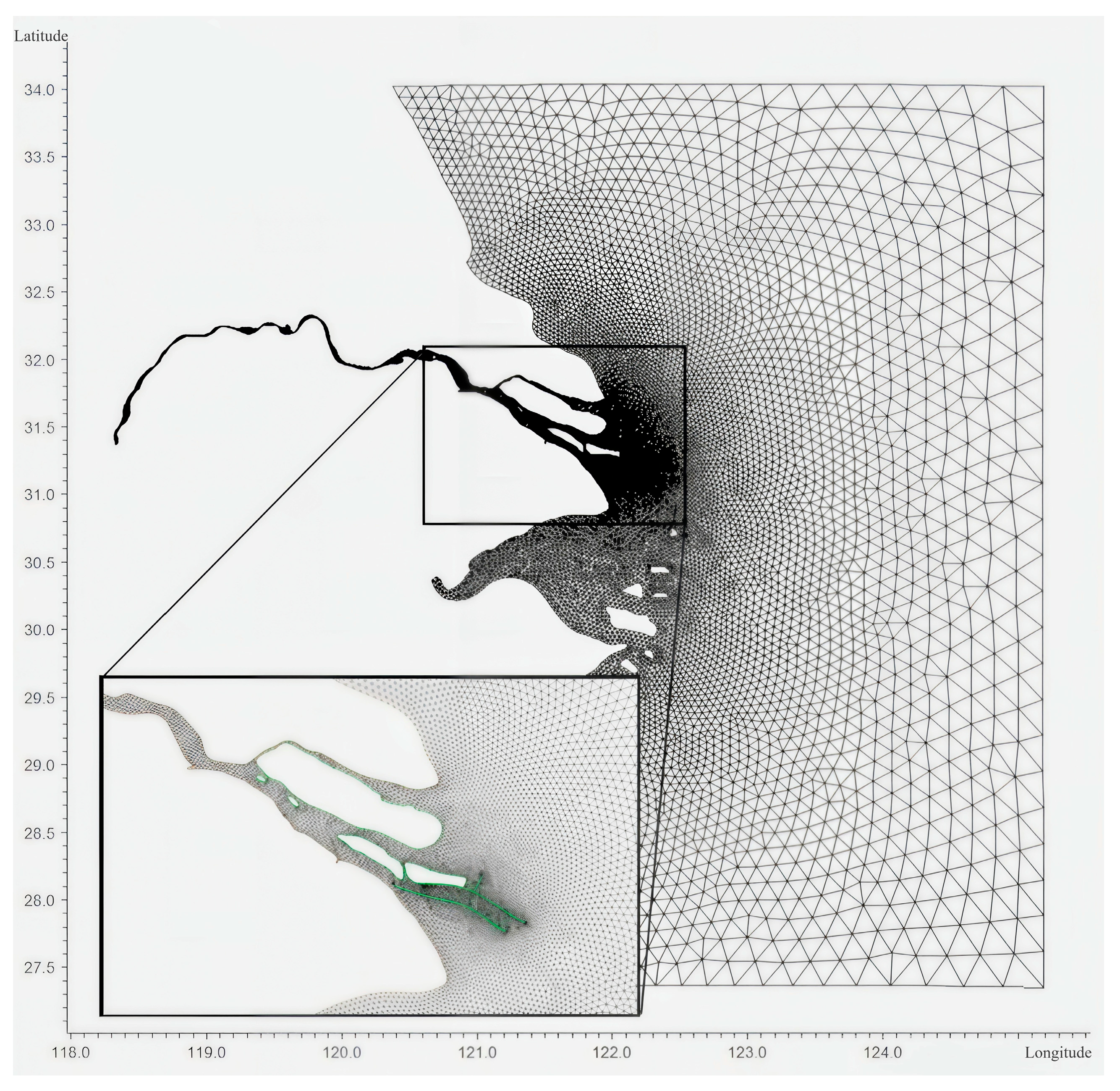

The model extends from Wuhu of the Yangtze River in the west to longitude 125° E in the east, to Lianyungang in the north, and to latitude 27.4° N in the south, including Hangzhou Bay, Zhoushan Islands, and other sea areas, covering the main tidal reaches of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. To minimize boundary effects, the lateral width of the domain is about 653 km, and the longitudinal length is about 740 km, covering a computational area of approximately 273,135 km

2. Due to the long and tortuous coastline of the YRE and the numerous islands with complex terrain in the Zhoushan sea area, an unstructured triangular mesh was employed, which enables the model to simulate the shoreline situation more realistically. The g mesh was optimized with resolutions ranging from 500 to 24,000 m to balance computational efficiency and accuracy, with higher resolution applied in the estuary area. As shown in

Figure 2, the model contains 18,114 nodes and 33,544 grids.

The accuracy of underwater terrain data is critical for model calculation. A wide-range underwater topography across the computation domain was obtained through the GIS digitization of charts provided by the Naval Aviation Protection Department. River depths were assigned based on navigational chart data, with all elevation data referencing the National 1985 Elevation Datum [

28].

3.3. Boundary Conditions and Parameter Settings

The time step of the model was automatically adjusted in the range of 0.01~30 s. The Courant number limit was set to 0.8. Bed roughness was represented by the Manning coefficient, which varied with water depth within a range of 20 to 80. A discharge boundary condition was applied at the upstream river boundary. Tidal level forcing at the open boundaries was derived from the MIKE 21 Tide Prediction Tool, encompassing 10 tidal constituents: M2, S2, K2, N2, S1, K1, O1, P1, Q1, and M4. Land and island boundaries were treated as impermeable, with a free-slip condition applied for water particles tangent to the coastline.

The horizontal eddy viscosity coefficient was calculated using the Smagorinsky formulation, which accounts for subgrid-scale effects. The expression is , where Cs is a constant, and mixing length l is calculated as (where are grid cell dimensions), and is defined by . Additionally, the Coriolis force varies with latitude, calculated as (where ω is the angular velocity of Earth’s rotation, and ϕ is the geographic latitude).

In this study, a modified model of the static water depth was adopted to simulate the influence of the rising sea level in the East China Sea on the tidal reach of the Yangtze River. To minimize the impact of the initial static water depth increase on simulated river levels, a cold start was employed, with the initial water level set uniformly to −5 m.

3.4. Model Calibration and Verification

The hydrodynamic model was calibrated against field observations before validation to ensure accurate tidal dynamics within the study domain. Tidal level and current velocity/direction measurements were used to optimize key parameters, with a primary focus on the spatially distributed bed roughness coefficient. Initial Manning values were assigned based on sedimentological properties and established research values, with subsequent localized adjustments based on bathymetric and seabed sediment distribution variations. Additional parameters, including the horizontal eddy viscosity coefficient, were determined using established empirical formulations. The model employed a wet–dry moving boundary scheme. The critical depth [

29] for dry, flood, and wet points was set to 0.005 m, 0.05 m, and 0.1 m, respectively.

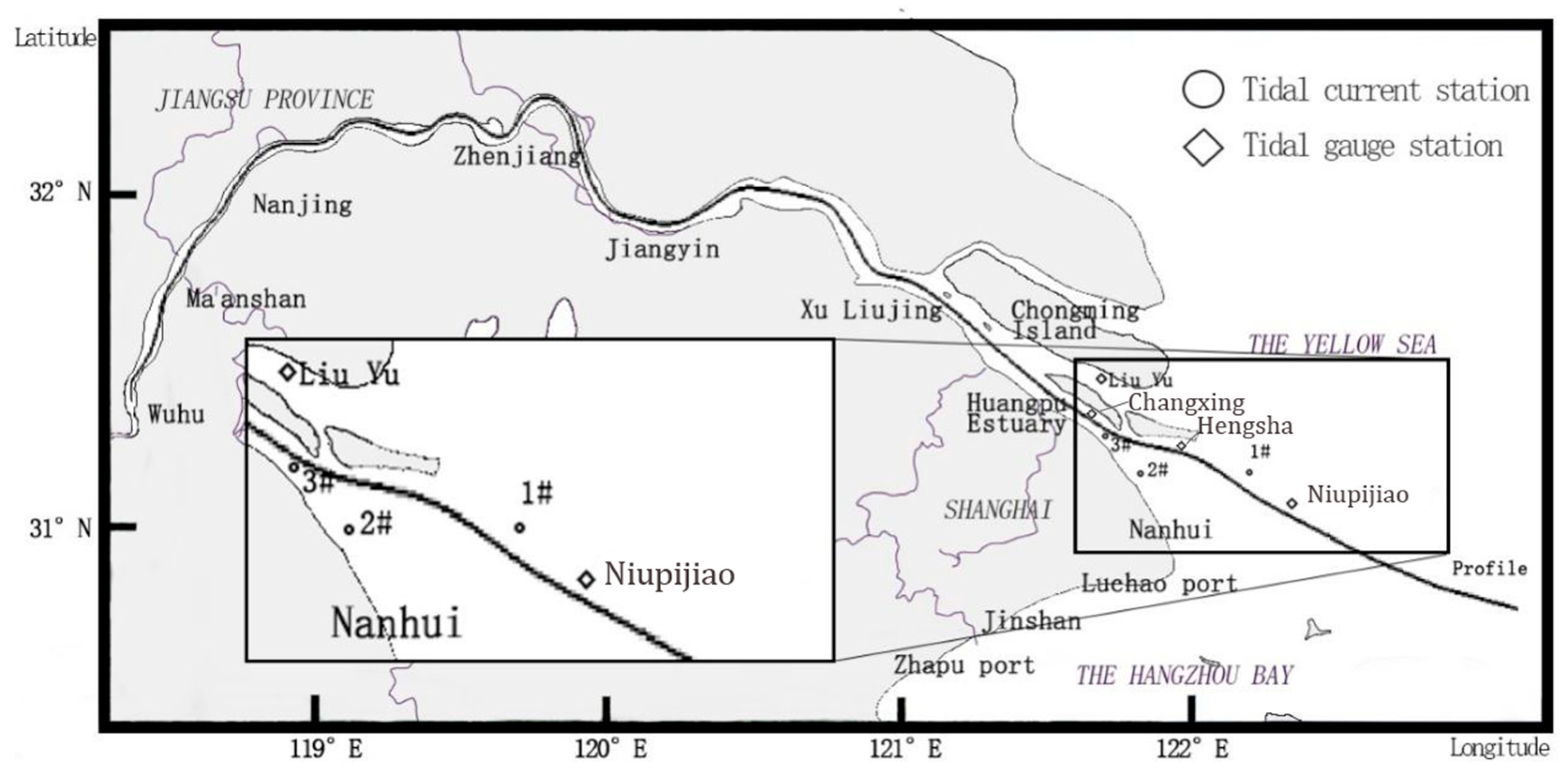

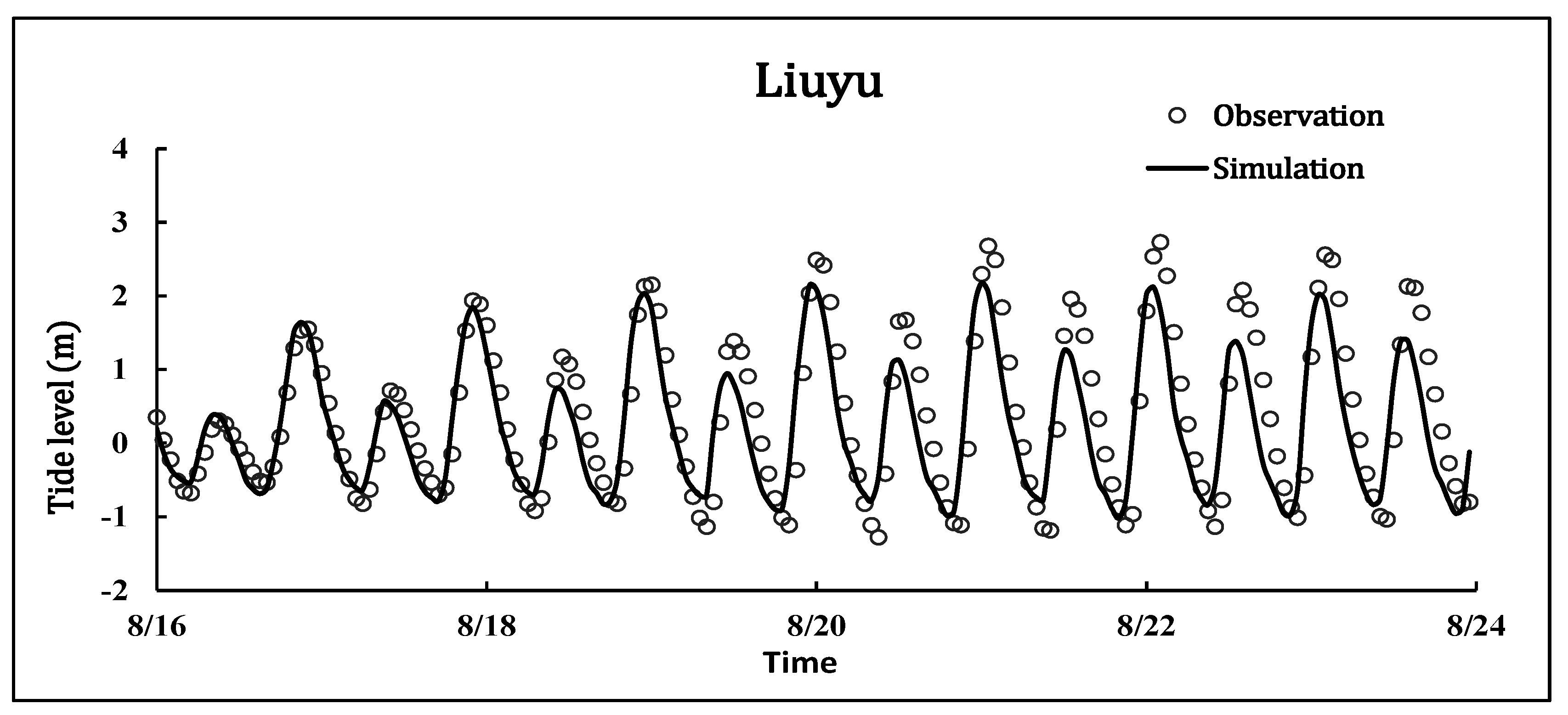

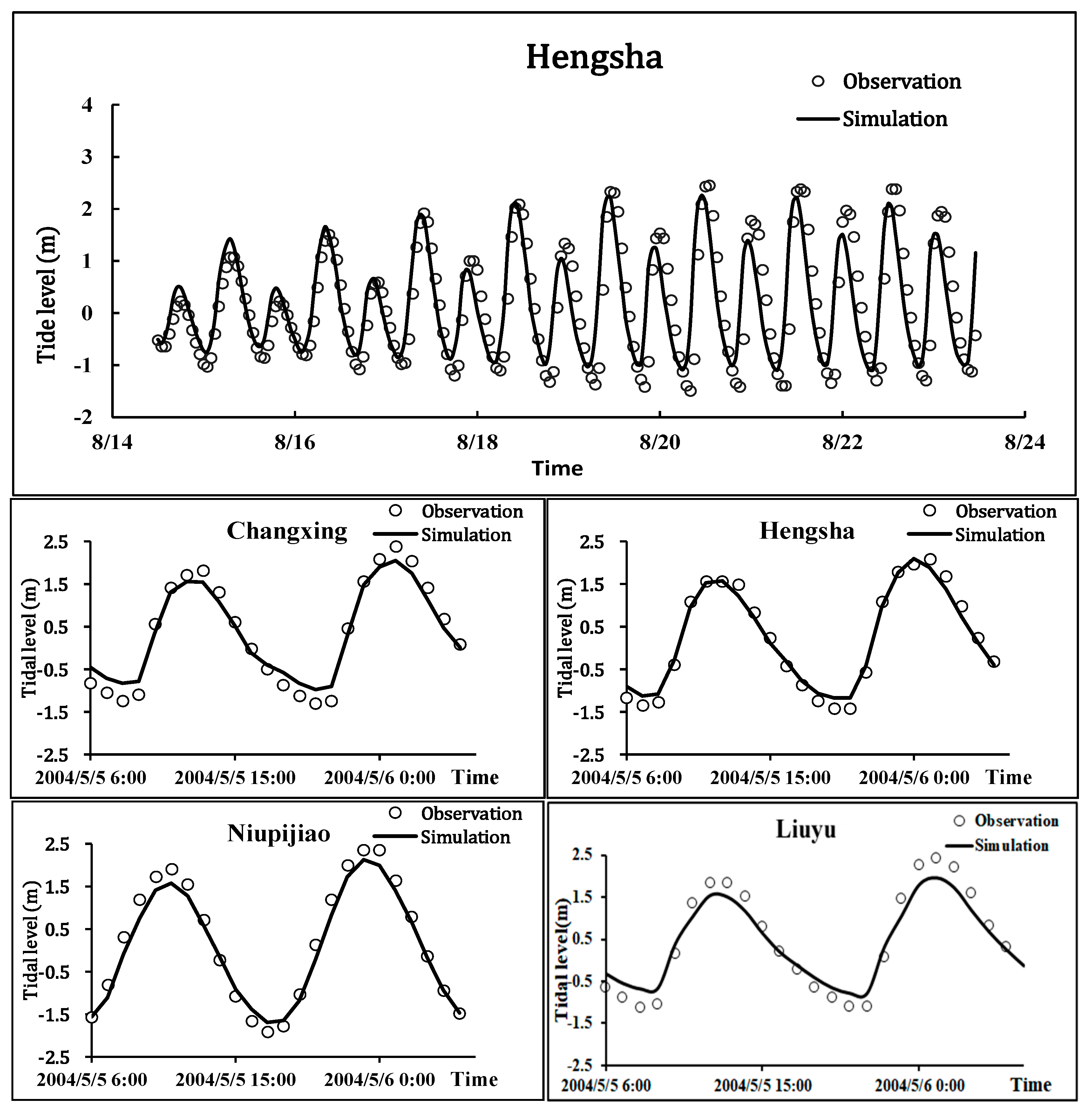

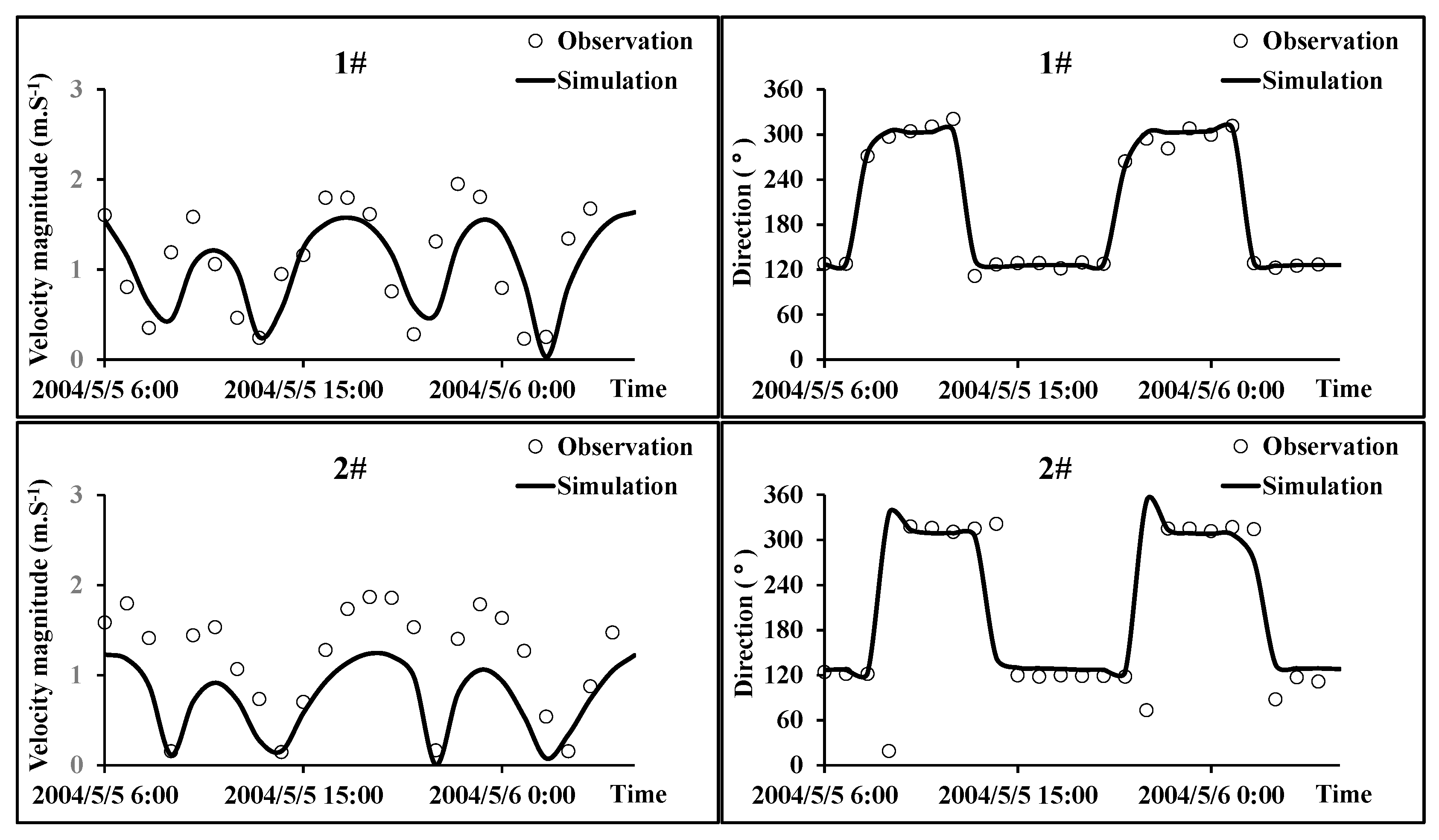

Measured tidal level, velocity, and direction data from four tidal stations and three flow stations were used for model validation. Station locations are shown in

Figure 1. Tidal levels at Liuyu and Hengsha (tidal stations) were validated using extended observational records spanning 14–24 August 2005. To broaden the validation period coverage and include the Yangtze Estuary–Yellow Sea confluence zone, tidal level data from Niupijiao and Changxing, along with velocity and direction data from stations #1–#3 during the spring tide period (5–6 May 2005), were also included.

Figure 3 shows the tidal level verification results. As shown in the figure, the calculated low tide levels at the Liuyu, Hengsha, Changxing, and Niupijiao stations are slightly higher than the measured values. The calculated high tide level at the Liuyu station is slightly lower than the measured value. Overall, the verification accuracy is better for short-term sequences than for long-term sequences.

Figure 4 presents the current velocity and direction verification process for stations #1–#3. The results show that the calculated maximum flood current velocity at #2 is less than the measured value; the calculated maximum flood current velocities at stations #1 and #3 are also slightly less than the measured values. For the remaining parts, the measured current velocities and directions match the calculated results well. Due to limitations in onsite measurements, tidal and seasonal velocity verification for the upstream tidal reach is currently not feasible. This study employed typical flow scenarios for subsequent simulations. In general, the verification results indicate that this model can effectively simulate the fundamental characteristics of tidal current movement in the Yangtze Estuary.

The model performance was quantitatively assessed using the skill model proposed by Wilmott [

30]. The skill model is formulated as below:

where

Pi is the simulated value,

Oi is the value of the in situ observed data,

is the average value of the observed data, and

N is the number of

i observations. A skill value of 1.0 indicates perfect model performance, excellent between 0.65 and 1, very good in the range of 0.5–0.65, good in the range of 0.2–0.5, and poor when less than 0.2 [

31]. According to the calculated results

Table 1, the validation generally supports the applicability of the hydrodynamic model in the YRE.

4. Computational Conditions Analysis

Yangtze River discharge exhibits significant seasonal variation between flood and dry seasons. The discharge increases significantly from May to October, accounting for 71.7% of the annual discharge, and decreases from November to April of the following year, accounting for 28.3%.

Based on China Sea Level Bulletin 2019, the rate of SLR along the coastal area of China is 3.4 mm/a from 1980 to 2019, and it is expected that in the next 30 years, the coastal sea level of Zhejiang province will rise by 51–179 mm [

32]. Cheng et al. believed that due to the superimposed effects of channel erosion in estuaries, including land reclamation projects in estuaries and water level rise caused by marine construction projects, the observed actual sea level rise would be larger than that of the predicted results [

33]. The IPCC 2013 assessment projected approximately 1 m of cumulative sea level rise from 1700 to 2100 under the RCP 8.5 scenario [

34]. Based on the historical relationship between global average land surface temperature and sea level change rate, Rahmstorf integrated the semi-empirical model of global average land surface temperature, concluding that the global sea level rise in 2100 could reach a maximum of 2.05 m [

35]. Based on various predictions of SLR, this study simulated the effects of an SLR of 0.5 m, 1.0 m, and 2.0 m on tidal waves in the YRE.

Based on the observed discharge data of the Yangtze River, combined effects of SLR and river discharges on tidal waves in the YRE were investigated using the maximum flood peak discharge, minimum dry discharge, and annual average discharge in the observation period. The time of the three discharge conditions corresponds, respectively, to the monthly average flow from July to September in the year of 1954 (76,900 m3/s), the monthly average flow from January to March in the year of 1963 (7800 m3/s), and the multi-year average flow from 1950 to 2000 (28,560 m3/s).

5. Results and Discussions

Based on the numerical results, water level data in May 2004 (the section position of which can be seen in

Figure 1) were extracted. The average, maximum, and minimum water level values under different SLR scenarios at the section nodes are calculated. The maximum water level fluctuation amplitude, the ratio R of average water level to fluctuation amplitude, and the change in tidal current along the river are computed [

36]. The harmonic analysis of tidal levels in Shanghai, Xuliujing, Jiangyin, Zhenjiang, Nanjing, and Wuhu was carried out to analyze the amplitude

η of the M

2, S

2, K

1, O

1, and M

4 tidal constituents and calculate the tidal wave attenuation rate

D [

37]. The formula is as follows:

where

is the sum of the amplitude value of partial tide in section nodes, namely

.

is the distance between two locations.

To clarify spatial relationships between stations, Wuhu is set as the reference point (0 km point), with along-estuary coordinates increasing eastward (

Table 2).

5.1. Changes in Tidal Waves

5.1.1. Effects of SLR Under Multi-Year Average Discharge

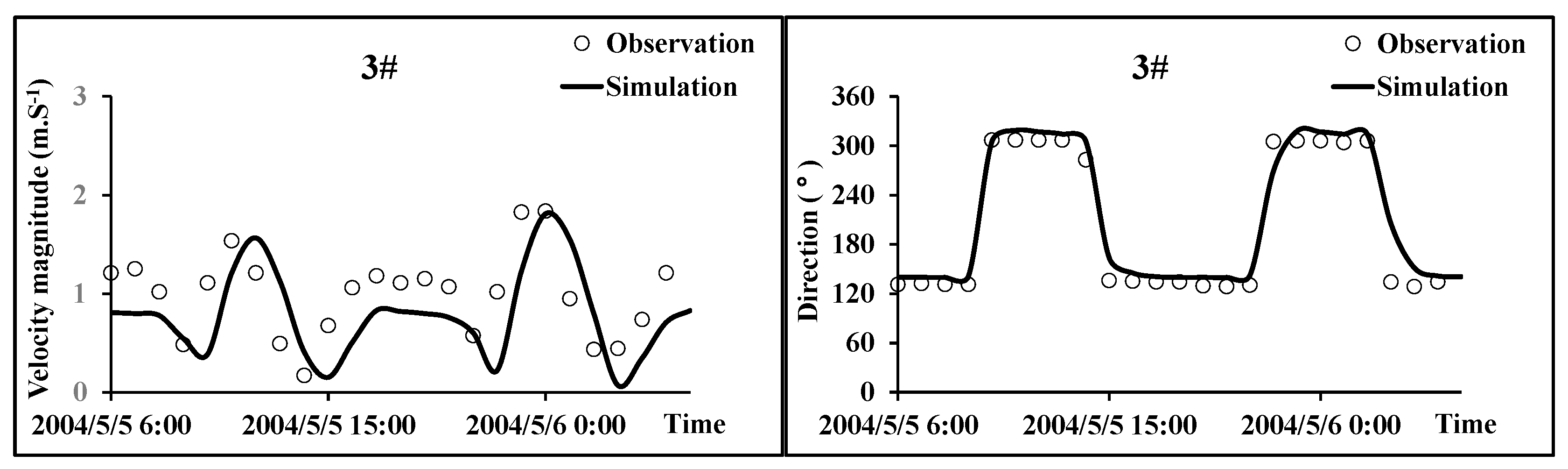

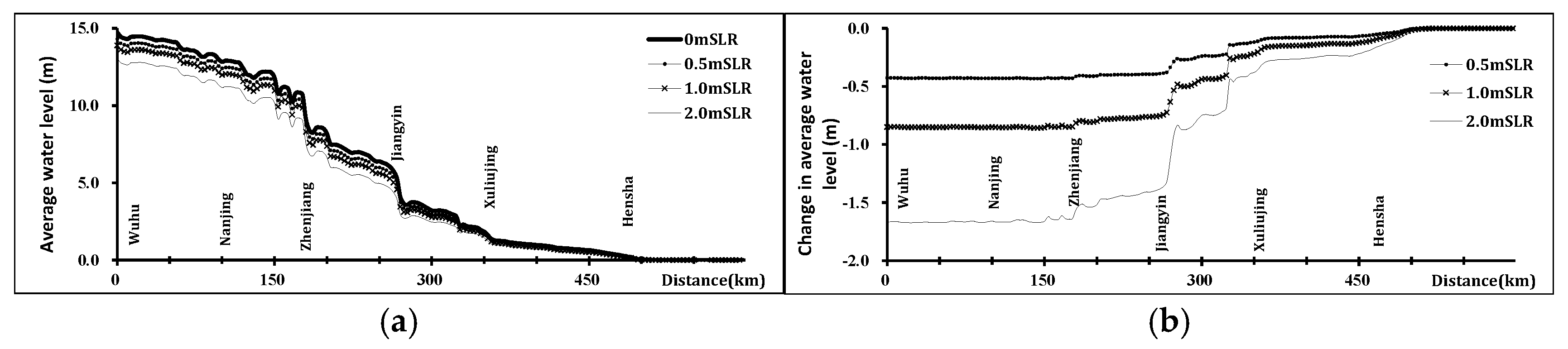

Figure 5 shows the average water level and corresponding water level changes along the river for different SLR scenarios (relative to the 0 m SLR baseline) under multi-year average discharge. Average water level denotes the tidal cycle averaged water surface elevation, referencing the local MSL in tidal-dominated zones and the Wusong Datum upstream, capturing both tidal and flow influences. Under multi-year average discharge conditions, the average water level gradually rises upstream. A rapid increase in average water level at approximately 95 km can be observed, along with another section exhibiting a rapid increase near Jiangyin. Sea level rise elevates the average water level throughout the tidal reach. Furthermore, the increase in the water level diminishes progressively upstream. At Wuhu, the average water level rise is only about 50% of the sea level rise.

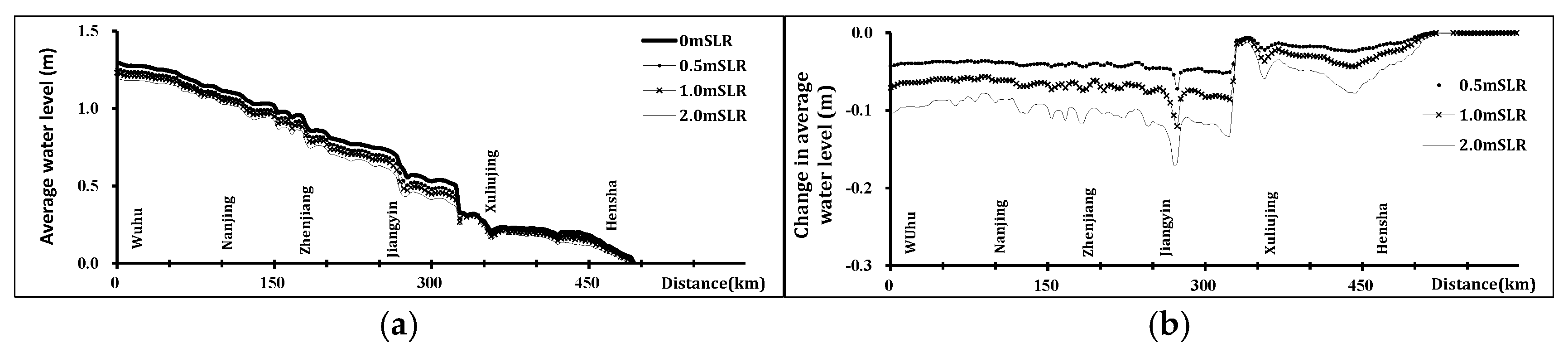

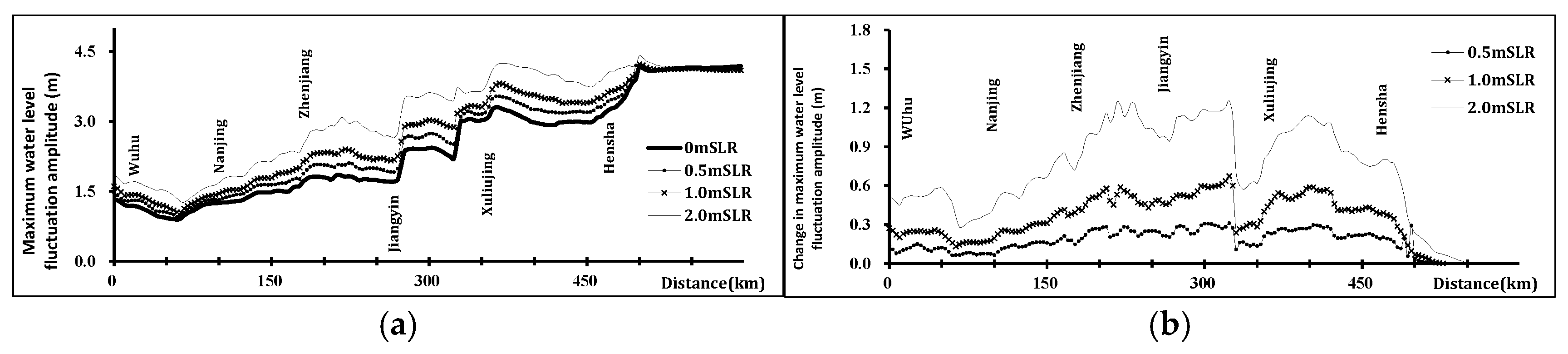

Figure 6 shows the maximum water level fluctuation amplitude and its corresponding changes for different SLR scenarios under multi-year average discharge. The maximum water level fluctuation amplitude gradually decreases upstream within the YRE, with a significant point of decrease at a point 315 km downstream from Wuhu (near Jiangyin). Changes in these fluctuation amplitudes are proportional to the SLR magnitude. Within the reach between Xuliujing and Jiangyin, the amplitudes decrease sharply to a minimum and then increase sharply to a secondary peak. Subsequently, the fluctuation amplitudes decrease gradually upstream from Jiangyin.

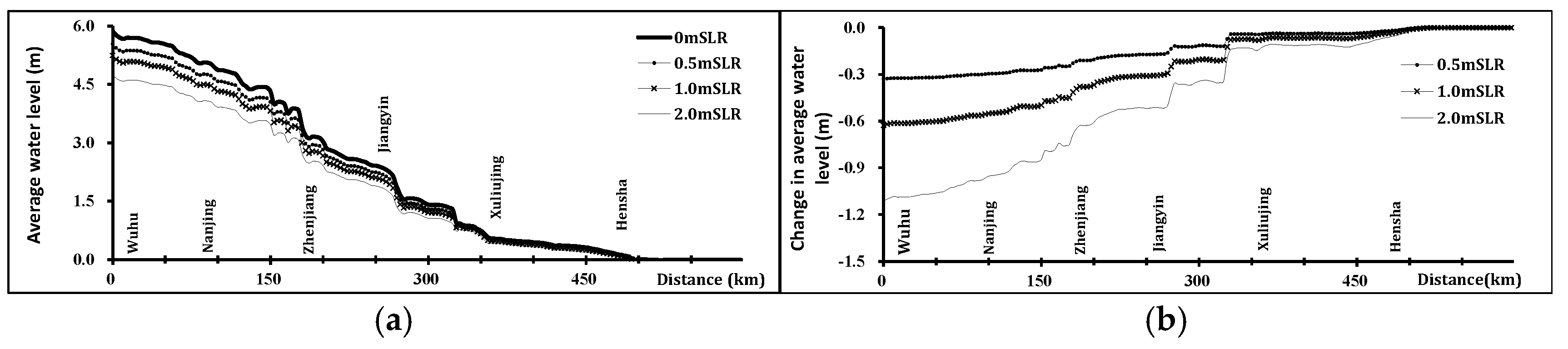

5.1.2. Effects of SLR Under Maximum Flood Discharge

Figure 7 shows the average water level and its change under different SLR scenarios. Under maximum discharge, the spatial pattern of the average water level change along the estuary is similar to that under average annual discharge (

Figure 5), but the changes are more significant. For 0.5 m and 1 m SLR, the amplitude of water level fluctuation tends to flatten in the upper reaches near Jiangyin. In contrast, under the 2 m SLR scenario, the amplitude continues to fluctuate and decrease along the reach from Jiangyin to Nanjing, stabilizing only in the upper reaches of Nanjing. Furthermore, the water level rise observed in Nanjing’s upper reaches accounts for only about 20% of the 2 m SLR.

Figure 8 shows the absolute maximum water level fluctuation amplitude and its change under different SLR scenarios. Under the maximum peak flood discharge, the absolute maximum water level fluctuation amplitude (

Figure 8a) gradually decreases upstream along the Yangtze River (from Hensha to Wuhu). Upon entering the Yangtze Estuary region from downstream, the change in amplitude increases gradually. The fluctuation reaches its first peak near 400 km. The amplitude then peaks again near 315 km (Jiangyin). Further upstream, both the absolute maximum amplitude and its change decrease progressively (

Figure 8b), approaching zero in the upper Nanjing reaches.

5.1.3. Effects of SLR Under Minimum Dry Discharge

Figure 9 shows the average water level and its change under different SLR scenarios. In the case of minimum dry discharge, SLR induces water level rise along the tidal reach, which is largely equivalent to the magnitude of SLR. A sharp increase in water level occurs approximately 35 km upstream from Xuliujing. Beyond this point, the water level increase induced by SLR diminishes sharply. Under the influence of SLR, the water level change in the estuary decreases at first and then increases. Upstream from Xuliujing, the change in the water level decreases rapidly and stabilizes further upstream.

Figure 10 shows the maximum water level fluctuation amplitude and its change under different SLR scenarios. The maximum amplitude fluctuates and decreases upward along the river, with rapid (though not large) decreases observed near Jiangyin and approximately 35 km upstream of Xuliujing. The magnitude of the maximum amplitude change is proportional to the magnitude of SLR. At about 35 km upstream of Xuliujing, the amplitude change increases sharply and remains at this range until the second peak occurs between Jiangyin and Zhenjiang. Beyond this point, both the water level fluctuation amplitude and its change decrease progressively upstream.

5.1.4. Changes in Ratio of Average Water Level to Maximum Water Level Fluctuation Amplitude

Figure 11 shows the ratio (R) of the average water level to the maximum water level fluctuation amplitude. Under SLR scenarios, this ratio decreases in the tidal reach as sea level rises, but its specific value is significantly influenced by the river discharge.

Under the multi-year average discharge, the ratio changes relatively smoothly in the river section downstream of Zhenjiang, while in the upstream section, it exhibits a fluctuating upward trend. The magnitude of this increase diminishes as sea level rises, as shown in

Figure 11a.

Under maximum flood discharge conditions, this ratio is significantly affected by SLR at 270 km downstream from Wuhu. Under the original sea level, it rapidly increases from 2 times to 20. However, under the 2 m SLR scenario, the magnitude of change significantly narrows, increasing only from 1 to 4, as shown in

Figure 11b. Changes in the ratio at 330 km downstream from Wuhu are relatively smaller and primarily influenced by river discharge.

Under minimum dry-flow conditions, this ratio within the study area is consistently less than 1.5, as shown in

Figure 11c. The peak occurs at approximately 65 km downstream from Wuhu.

5.2. Changes in Tidal Current Velocity Within the Tidal Reach

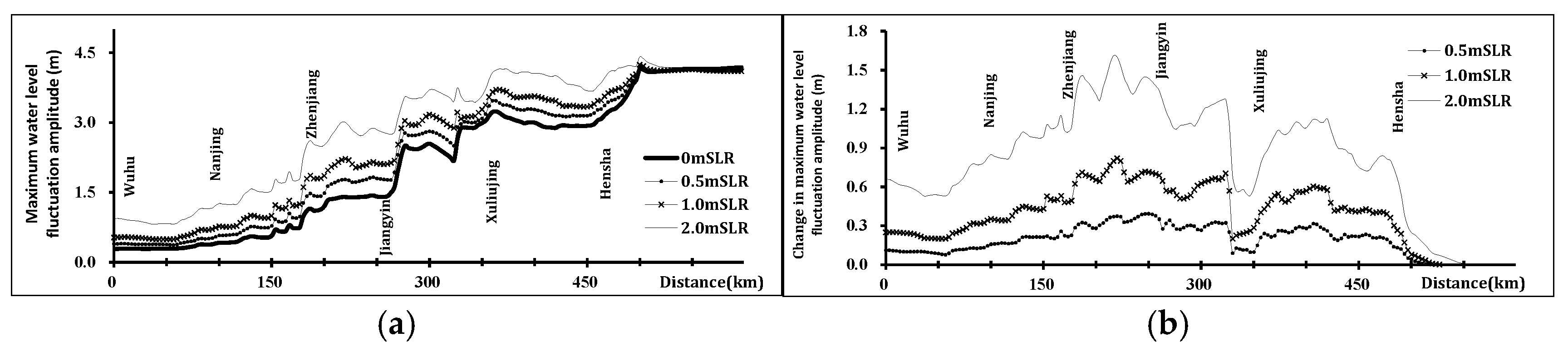

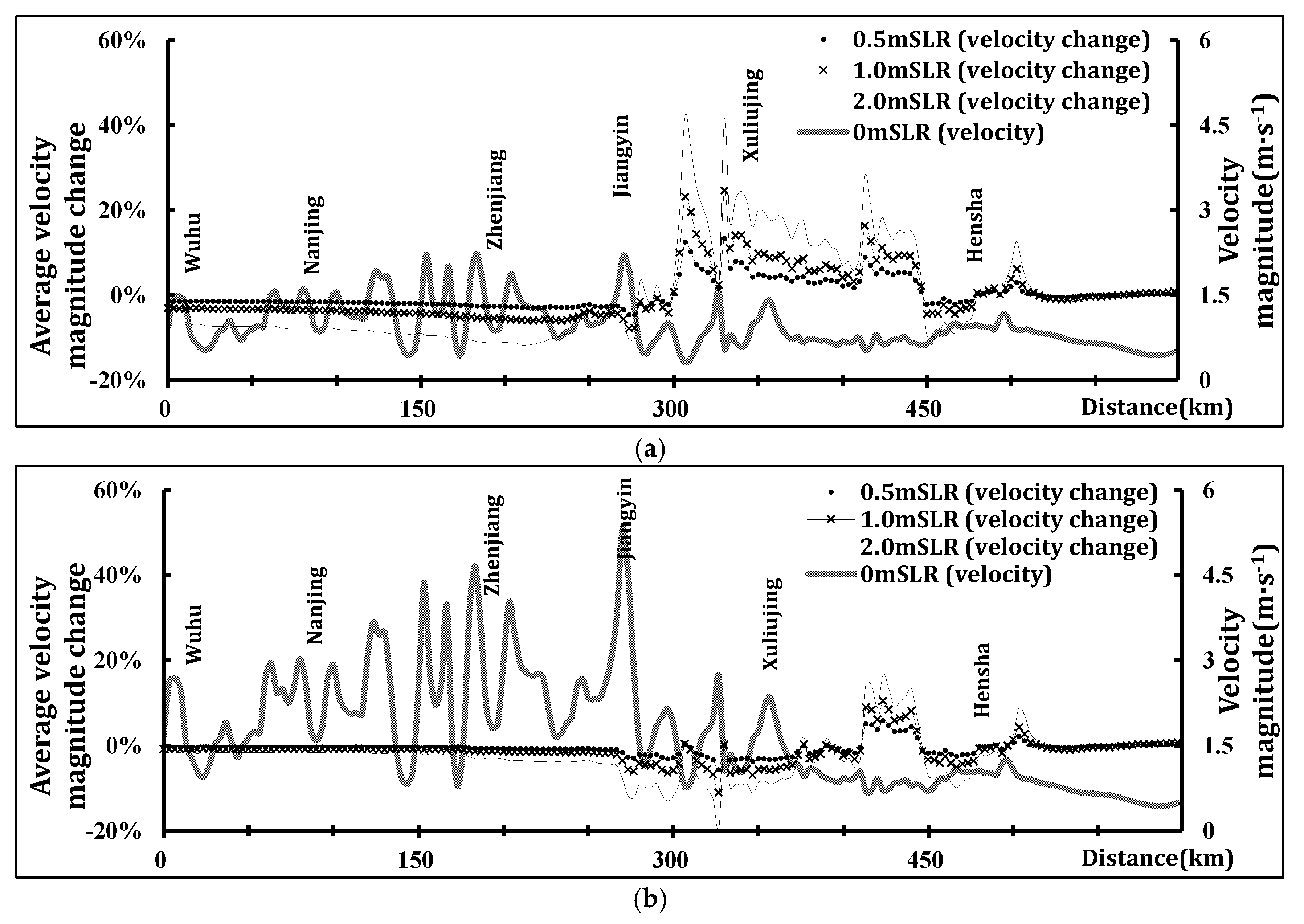

Figure 12 shows the percentage change in tidal current velocity magnitude under different river discharge and SLR scenarios. The amplitude of tidal current change correlates positively with the magnitude of SLR, while the shape of the change curve is determined by river discharge conditions. Moving upstream from the estuary, the velocity magnitude increases slightly at 500 km mark but decreases slightly between approximately 400 and 430 km. SLR-induced increases in velocity magnitude generally remain below 60%.

Under the annual average discharge scenario (

Figure 12a), the change in velocity magnitude correlates positively with SLR, showing fluctuating increases along the 350–400 km reach. Within the subsequent 300–350 km reach, two peaks of 40% change occur, but the magnitude rapidly decreases to zero at 300 km downstream from Wuhu. Upstream of 300 km, velocity changes become negligible, except a maximum reduction of −12% can be observed at 225 km under 2 m SLR.

Under maximum flood flow conditions (

Figure 12b), velocity changes upstream of 400 km are negative (0% to −20%) with irregular fluctuations. The magnitude of this decrease correlates negatively with SLR magnitude (larger SLR leads to larger velocity reduction). Changes gradually converge around 250 km and stabilize by 150 km, showing a 1.6% reduction in velocity under 2 m SLR.

During minimum dry-flow conditions, tidal velocity magnitude changes significantly with SLR. Across most of the reach, velocity change positively correlates with SLR (greater SLR increases velocity). Under 2 m SLR, velocity magnitude increases by over 20% between 100 and 350 km, peaking at 54%. However, after reaching its maximum at 100 km, velocity magnitude rapidly decays upstream, dropping to zero at 20 km downstream from Wuhu. Further upstream, velocity changes become negative, with the magnitude of reduction also positively correlated with SLR (larger SLR leads to larger velocity reduction).

5.3. Tidal Wave Attenuation

The attenuation of tidal wave amplitudes under different SLR conditions obtained from tidal harmonic analysis is shown in

Table 3. Tidal energy within the river channel is attenuated by bottom friction and river discharge, while SLR reduces the bottom friction of the channel.

The tidal wave attenuation rate in the Wuhu–Xuliujing reach is significantly reduced by SLR. It is worth noting that the tidal wave attenuation rate increases in the Xuliujing–estuary area under 0.5 m and 1 m SLR, but decreases under 2 m SLR. In the Zhenjiang–Xuliujing River section, the decrease in attenuation rate caused by SLR is more obvious than that in the Wuhu–Zhenjiang River section. The decrease in the former reach is about 1.3 × 10−6, 2.4 × 10−6, and 4.2 × 10−6 under an SLR of 0.5 m, 1 m, and 2 m, respectively. In comparison, the decrease in the latter is only about 0.4 × 10−6, 0.9 × 10−6, and 2.1 × 10−6. The reduction in the Wuhu–Zhenjiang reach is about half of that in the Zhenjiang–Xuliujing reach.