22 Years of Governance Structures and Performance: What Has Been Achieved in Agrifood Chains and Beyond? A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. How has the relationship between governance structures and performance in the agrifood sector and beyond evolved over the last two decades?

- RQ2. What theories have been applied in investigating the relationship between governance structures and performance?

2. Performance Measurement in Agrifood Chains and Beyond

3. Material and Methods

- Planning;

- Searching/paper identification;

- Screening/eligibility and inclusion criteria;

- Extraction and synthesis;

- Reporting.

3.1. Planning

- How has the relationship between governance structures and performance in the agrifood sector and beyond evolved over the last two decades?

- What theoretical mechanisms underpin the outcome relationship?

- What types of governance structures are being measured in agrifood chains, manufacturing companies, or service companies?

- What performance measurement indicators have been proposed and observed in linking its relationship to governance structure?

3.2. Paper Identification/Searching

(“Governance Structures” OR “Coordination Mechanisms” OR “Governance Mechanisms” OR “Vertical Coordination” OR “Distribution Channels” OR “Governance Arrangements” OR “Relational Governance” OR “Formal OR Contractual Governance”) AND (“Performance Measurement” OR “Chain Performance” OR “Chain Enhancement” OR “Effectiveness” OR “Business outcome” OR “Customer satisfaction” OR “Performance”) AND NOT (“Corporate governance” OR “Corporate Performance”), (“Agrifood chain”).

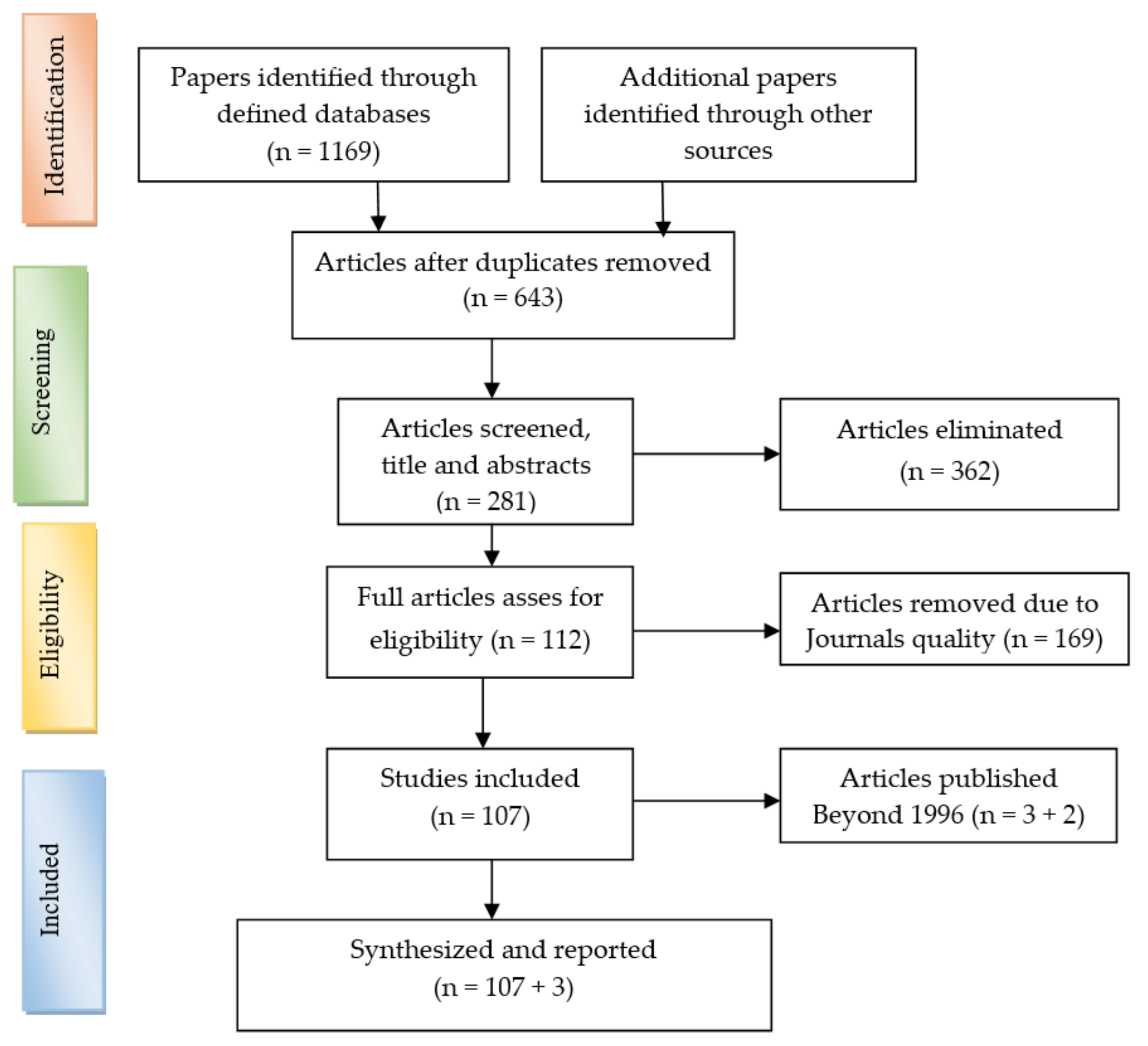

3.3. Screening/Eligibility and Inclusion Criteria

3.4. Extraction and Synthesis

3.5. Reporting

4. Findings

4.1. Industry Sectors and Distribution of Research Methods

4.2. Major Theories That Have Been Applied

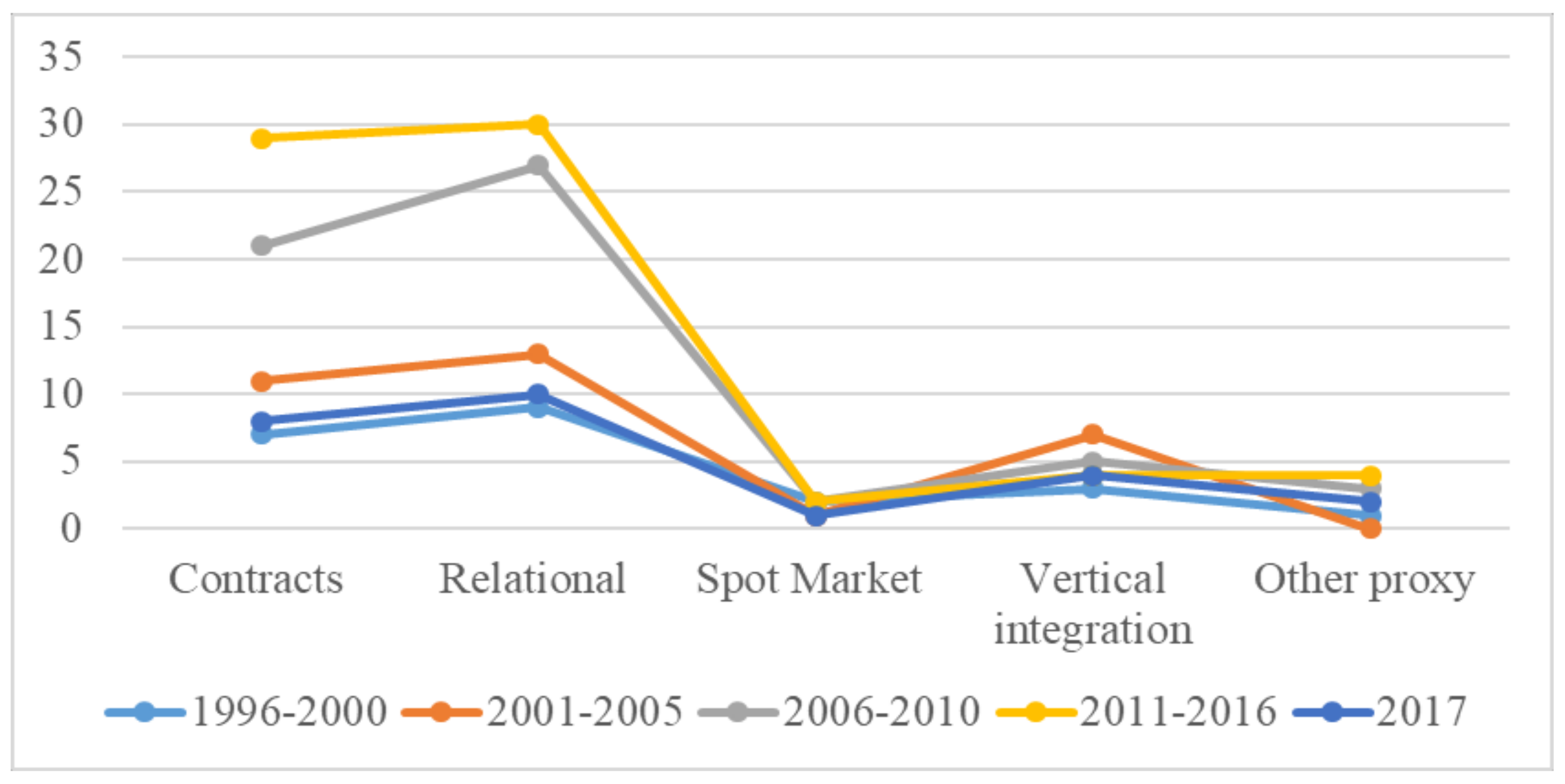

4.3. Governance Structures Measured over the Past 22 Years

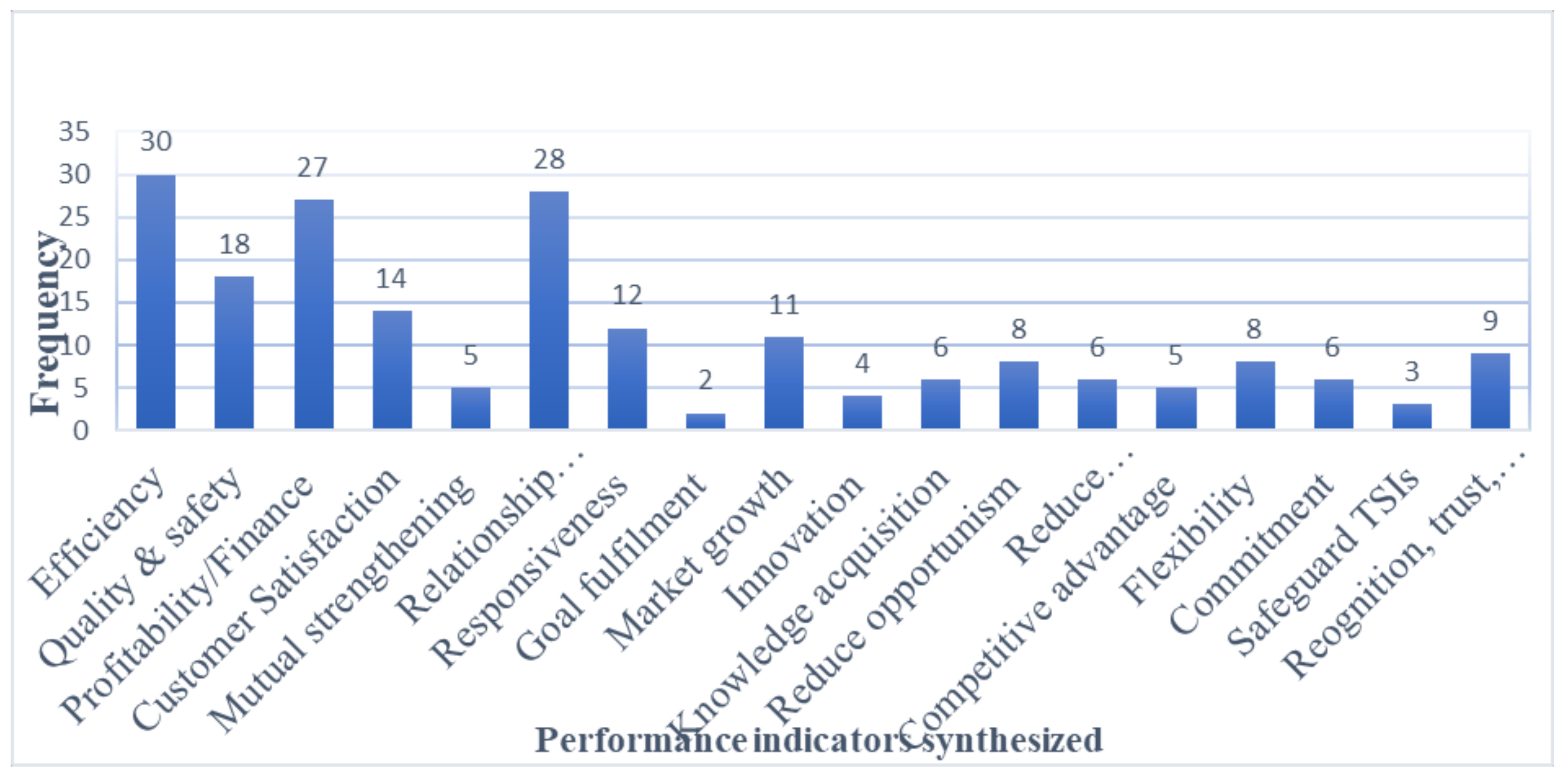

4.4. Measured Performance Indicators

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Contributions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williamson, O.E. The Mechanisms of Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Intstitutions of Capitalism; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H. Does governance matter? Keiretsu alliances and asset specificity as sources of Japanese competitive advantage. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Heide, J.B. Transaction cost analysis: Past, present, and future applications. J. Market. 1997, 61, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.; Gelderman, C.J. The safeguarding effect of governance mechanisms in inter-firm exchange: The decisive role of mutual opportunism. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, P.-M.; Cassivi, L.; Hadaya, P.; Caya, O. Safeguarding mechanisms in a supply chain network. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2006, 106, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathne, K.H.; Heide, J.B. Opportunism in interfirm relationships: Forms, outcomes, and solutions. J. Market. 2000, 64, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jap, S.D.; Ganesan, S. Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. J. Market. Res. 2000, 37, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, P.S.; Van de Ven, A.H. Structuring cooperative relationships between organizations. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; Venkatraman, N. Relational governance as an interorganizational strategy: An empirical test of the role of trust in economic exchange. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.K.; Teng, B.-S. Between trust and control: Developing confidence in partner cooperation in alliances. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J.; Poppo, L.; Zhou, K.Z. Relational mechanisms, formal contracts, and local knowledge acquisition by international subsidiaries. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppo, L.; Zenger, T. Do formal contracts and relational governance function as substitutes or complements? Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.Y.; Fulop, L. Managerial trust and work values within the context of international joint ventures in China. J. Int. Manag. 2007, 13, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.J.; Handfield, R.B.; Lawson, B.; Cousins, P.D. Buyer dependency and relational capital formation: The mediating effects of socialization processes and supplier integration. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2008, 44, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Liu, T. Governing buyer–supplier relationships through transactional and relational mechanisms: Evidence from China. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangpong, C.; Hung, K.-T.; Ro, Y.K. The interaction effect of relational norms and agent cooperativeness on opportunism in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fałkowski, J.; Chlebicka, A.; Łopaciuk-Gonczaryk, B. Social relationships and governing collaborative actions in rural areas: Some evidence from agricultural producer groups in poland. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 49, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-C.; Cheng, H.-L.; Tseng, C.-Y. Reexamining the direct and interactive effects of governance mechanisms upon buyer–supplier cooperative performance. Ind. Market. Manag. 2014, 43, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, H.C.; Wysocki, A.; Harsh, S.B. Strategic choice along the vertical coordination continuum. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2001, 4, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynaud, E.; Sauvee, L.; Valceschini, E. Alignment between quality enforcement devices and governance structures in the agro-food vertical chains. J. Manag. Gov. 2005, 9, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Aramyan, L.H. A conceptual framework for supply chain governance: An application to agri-food chains in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2009, 1, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, M.; Wognum, P.M.; Trienekens, J.H.; Omta, S.W.F. Supply chain-wide consequences of transaction risks and their contractual solutions: Towards an extended transaction cost economics framework. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012, 48, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Calculativeness, trust, and economic organization. J. Law Econ. 1993, 36, 453–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The institutions of governance. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Arias, G.; Ruben, R. Determinants of market outlet choice for mango producers in costa rica. Gov. Qual. Trop. Food Chains 2007, 2, 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, J.P.; Perreault, W.D., Jr. Buyer-seller relationships in business markets. J. Market. Res. 1999, 36, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, M.; Deepak, T.; Salim, A.N.; Ponniah, V. Analysis of delays in tanzanian construction industry: Transaction cost economics (TCE) and structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2017, 24, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.R.; Krishen, A.S.; Dev, C.S. The role of ownership in managing interfirm opportunism: A dyadic study. J. Market. Channels 2014, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporleder, T.L. Managerial economics of vertically coordinated agricultural firms. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1992, 74, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.R. Measuring and assessing vertical ties in the agro-food system. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D’agroecon. 1994, 42, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, B.; Spiller, A.; Theuvsen, L. A broader view on vertical coordination: Lessons from german pork production. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2007, 7, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banterle, A.; Stranieri, S. The consequences of voluntary traceability system for supply chain relationships. An application of transaction cost economics. Food Policy 2008, 33, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, M.; Wognum, N.; Trienekens, J.; Omta, O. Alignment between chain quality management and chain governance in EU pork supply chains: A transaction-cost-economics perspective. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilelu, C.W.; Klerkx, L.; Leeuwis, C. Supporting smallholder commercialisation by enhancing integrated coordination in agrifood value chains: Experiences with dairy hubs in Kenya. Exp. Agric. 2017, 53, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, M.A.; Fawcett, S.E. Data science, predictive analytics, and big data: A revolution that will transform supply chain design and management. J. Bus. Logist. 2013, 34, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.; Oke, A.; Olhager, J. Supply chain processes: Linking supply logistics integration, supply performance, lean processes and competitive performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. A transaction cost approach to supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 1996, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weseen, S.; Hobbs, J.E.; Kerr, W.A. Reducing hold-up risks in ethanol supply chains: A transaction cost perspective. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S.D.; Henderson, D.R. Transaction costs as determinants of vertical coordination in the US food industries. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1992, 74, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, J.T. The choice of organizational form: Vertical financial ownership versus other methods of vertical integration. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 559–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, D.C.; Gilliland, D.I. The effect of output controls, process controls, and flexibility on export channel performance. J. Market. 1997, 61, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. The art of the possible: Relationship management in power regimes and supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L.M.; Hobbs, J.E. Vertical linkages in agri-food supply chains: Changing roles for producers, commodity groups, and government policy. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2002, 24, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Hartmann, M.; Reynolds, N.; Leat, P.; Revoredo-Giha, C.; Henchion, M.; Albisu, L.M.; Gracia, A. Factors influencing contractual choice and sustainable relationships in european agri-food supply chains. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2009, 36, 541–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, R.J.; Han, S.K. A systematic assessment of the empirical support for transaction cost economics. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelanski, H.A.; Klein, P.G. Empirical research in transaction cost economics: A review and assessment. J. Law Econom. Organ. 1995, 11, 335–361. [Google Scholar]

- Pyone, T.; Smith, H.; van den Broek, N. Frameworks to assess health systems governance: A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2017, 32, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbufalo, E. Outcomes of inter-organizational trust in supply chain relationships: A systematic literature review and a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilbeam, C.; Alvarez, G.; Wilson, H. The governance of supply networks: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 358–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, G. Tourism value chain governance: Review and prospects. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramyan, L.H.; Oude Lansink, A.G.; Van Der Vorst, J.G.; Van Kooten, O. Performance measurement in agri-food supply chains: A case study. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2007, 12, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.; Gregory, M.; Platts, K. Performance measurement system design: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1995, 15, 80–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beamon, B.M. Supply chain design and analysis: Models and methods. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1998, 55, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Strategies for Reducing Cost and Improving Service; Financial Times: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Patel, C.; Tirtiroglu, E. Performance measures and metrics in a supply chain environment. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2001, 21, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Ngai, E.W. Information systems in supply chain integration and management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 159, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Lai, K.-H.; Edwin Cheng, T. Responsive supply chain: A competitive strategy in a networked economy. Omega 2008, 36, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, F.; Nookabadi, A.S.; Kadivar, M. A model for measuring the performance of the meat supply chain. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 1090–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellynck, X.; Molnár, A.; Aramyan, L. Supply chain performance measurement: The case of the traditional food sector in the EU. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2008, 8, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, A.D.; Adams, C.; Kennerley, M. The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Business Success; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yeung, J.F.; Chan, A.P.; Chiang, Y.; Chan, D.W. A critical review of performance measurement in construction. J. Facil. Manag. 2010, 8, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Kaluarachchi, Y. Performance measurement and benchmarking of a major innovation programme. Benchmark. Int. J. 2008, 15, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, O.; Haupt, T. Key performance indicators and assessment methods for infrastructure sustainability—A south African construction industry perspective. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Singh, A.P.; Metri, B.A. Key performance indicators for the organized farm products retailing in India. Bus. Anal. Cyber Secur. Manag. Organ. 2016, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, S.S.A.; Al Shobaki, M.J.; Amuna, Y.M.A. Knowledge management maturity in universities and its impact on performance excellence “comparative study”. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Electr. Eng. 2016, 5, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Nadiri, M. Performance assessment of Iranian petrochemical companies using sustainable excellence model. Saf. Sci. 2016, 87, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Xu, D. How foreign firms curtail local supplier opportunism in China: Detailed contracts, centralized control, and relational governance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, X.; Ao, J.; Cai, L. Governance mechanisms and new venture performance in China. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2013, 30, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.P.; Achrol, R.S.; Gundlach, G.T. Contracts, norms, and plural form governance. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2000, 28, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, M.; Aulakh, P.S. Do country-level institutional frameworks and interfirm governance arrangements substitute or complement in international business relationships? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, L.; Florez-Lopez, R.; Ramon-Jeronimo, J.M. Accounting, performance measurement and fairness in uk fresh produce supply networks. Account. Organ. Soc. 2018, 64, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.-C.; Chiu, Y.-P. Relationship governance mechanisms and collaborative performance: A relational life-cycle perspective. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staples, M.; Niazi, M. Experiences using systematic review guidelines. J. Syst. Softw. 2007, 80, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Pittaway, L.; Robertson, M.; Munir, K.; Denyer, D.; Neely, A. Networking and innovation: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2004, 5, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashman, L.; Withers, E.; Hartley, J. Organizational learning and knowledge in public service organizations: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2009, 11, 463–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, A. The literature search: A library-based model for information skills instruction. Libr. Rev. 1996, 45, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, A.R.; Cook, D.J.; Jones, A.; Klassen, T.P.; Tugwell, P.; Moher, M.; Moher, D. Methodology and reports of systematic reviews and meta-analyses: A comparison of cochrane reviews with articles published in paper-based journals. JAMA 1998, 280, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordewier, T.G.; John, G.; Nevin, J.R. Performance outcomes of purchasing arrangements in industrial buyer-vendor relationships. J. Market. 1990, 54, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruekert, R.W.; Walker, O.C., Jr.; Roering, K.J. The organization of marketing activities: A contingency theory of structure and performance. J. Market. 1985, 49, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske-Janssen, P.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. 20 years of performance measurement in sustainable supply chain management–what has been achieved? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two decades of sustainability management tools for smes: How far have we come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.J.; Baird, J.; Arai, L.; Law, C.; Roberts, H.M. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, A.; Garcia, J.; Oliver, S.; Rees, R.; Shepherd, J.; Brunton, G.; Oakley, A. Applying systematic review methods to studies of people’s views: An example from public health research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a Systematic Review; Sage Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Manning, J.; Denyer, D. 11 evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2008, 2, 475–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmans, M.E.; Rogge, E.; Mettepenningen, E.; Knickel, K.; Šūmane, S. The role of multi-actor governance in aligning farm modernization and sustainable rural development. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 59, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Bánkuti, S.S.; Lourenzani, A.E. “Pingado dilemma”: Is formal contract sweet enough? J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, G.K.; Chalak, A.; Abiad, M.G. The effect of governance mechanisms on food safety in the supply chain: Evidence from the lebanese dairy sector. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2908–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolci, P.C.; Maçada, A.C.G.; Paiva, E.L. Models for understanding the influence of supply chain governance on supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2017, 22, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Zhao, Y. Contract Specificity, Contract Violation, and Relationship Performance in International Buyer–Supplier Relationships; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, G.; Zhou, N. Relational norms and collaborative activities: Roles in reducing opportunism in marketing channels. Ind. Market. Manag. 2015, 46, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, C.; Patterson, P.G.; Ahmed, F. A relational model of export performance. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2008, 39, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, R.; Claycomb, C.; Dröge, C. Supply chain variability, organizational structure, and performance: The moderating effect of demand unpredictability. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yeung, H.Y.J.; Liu, Y. Improving logistics outsourcing performance through transactional and relational mechanisms under transaction uncertainties: Evidence from China. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 175, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S. Impact of specific investments, governance mechanisms and behaviors on the performance of cooperative innovation projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, M.; Ivens, B.S.; Shan, J. Governance mechanisms in domestic and international buyer–supplier relationships: An empirical study. Ind. Market. Manag. 2012, 41, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S.; Lawson, B.; Krause, D.R. Social capital configuration, legal bonds and performance in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooi, E.A.; Ghosh, M. Contract specificity and its performance implications. J. Market. 2010, 74, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hoetker, G.; Mellewigt, T. Choice and performance of governance mechanisms: Matching alliance governance to asset type. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, E.; Teo, H.-H.; Peng, M.W. Formal control and social control in domestic and international buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Trienekens, J.H.; Omta, S.O. Relationship and quality management in the chinese pork supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 134, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, D.; Haunschild, P.R.; Khanna, P. Organizational differences, relational mechanisms, and alliance performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 1453–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, J.S.; Frankel, R.; Anselmi, K. The effect of governance structure on performance: A case study of efficient consumer response. J. Bus. Logist. 1999, 20, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Tachizawa, E.M.; Wong, C.Y. The performance of green supply chain management governance mechanisms: A supply network and complexity perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 51, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capaldo, A.; Giannoccaro, I. How does trust affect performance in the supply chain? The moderating role of interdependence. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 166, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S. Specific subjects. J. Inf. Sci. 1985, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Birthal, P.S.; Chand, R.; Joshi, P.; Saxena, R.; Rajkhowa, P.; Khan, M.T.; Khan, M.A.; Chaudhary, K.R. Formal versus informal: Efficiency, inclusiveness and financing of dairy value chains in Indian punjab. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Zhao, J.; George, J.F.; Li, Y.; Zhai, S. The influence of inter-firm it governance strategies on relational performance: The moderation effect of information technology ambidexterity. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthuysen, K.; Slabbinck, H.; Roodhooft, F. Formal controls and alliance performance: The effects of alliance motivation and informal controls. Manag. Account. Res. 2017, 37, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, M.; Aulakh, P.S. Locus of uncertainty and the relationship between contractual and relational governance in cross-border interfirm relationships. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 771–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Feng, Y.; Choi, S.-B. The role of customer relational governance in environmental and economic performance improvement through green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.M.; Trienekens, J.; Omta, O. Governance structures and coordination mechanisms in the brazilian pork chain–diversity of arrangements to support the supply of piglets. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhao, X. Governance mechanisms of dual-channel reverse supply chains with informal collection channel. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 155, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, J.G.; Yang, C.; Sheu, C. A transaction cost economics model for estimating performance effectiveness of relational and contractual governance: Theory and statistical results. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 1551–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifković, N. Vertical coordination and farm performance: Evidence from the catfish sector in vietnam. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Liang, J.; Zhou, K.Z. How to enhance supplier performance in China: An integrative view of partner selection and partner control. Ind. Market. Manag. 2016, 56, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-García, A.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J.; Rey-Moreno, M. Relational governance mechanisms in export activities: Their determinants and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4750–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmonbekov, T.; Gregory, B.; Chelariu, C.; Johnston, W.J. The impact of social and contractual enforcement on reseller performance: The mediating role of coordination and inequity during adoption of a new technology. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 2016, 31, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Guo, S.; Qian, L.; He, P.; Xu, X. The effectiveness of contractual and relational governances in construction projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.L.; Ju, M.; Gao, G.Y. Export relational governance and control mechanisms: Substitutable and complementary effects. Int. Market. Rev. 2015, 32, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Maksimov, V.; Hou, J. Improving performance and reducing cost in buyer–supplier relationships: The role of justice in curtailing opportunism. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heide, J.B.; Kumar, A.; Wathne, K.H. Concurrent sourcing, governance mechanisms, and performance outcomes in industrial value chains. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1164–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppo, L.; Zhou, K.Z. Managing contracts for fairness in buyer–supplier exchanges. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1508–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Li, X.; Lai, V.S. Transaction-specific investments, relational norms, and erp customer satisfaction: A mediation analysis. Decis. Sci. 2013, 44, 679–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lu, H.; Trienekens, J.H.; Omta, S.W.F. The impact of supply chain integration on firm performance in the pork processing industry in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2013, 7, 230–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Tong, J.; Liu, X. Relational mechanisms, market contracts and cross-enterprise knowledge trading in the supply chain: Empirical research based on chinese manufacturing enterprises. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 488–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Keil, M.; Hornyak, R.; WüLlenweber, K. Hybrid relational-contractual governance for business process outsourcing. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 213–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, N.; Arroyabe, J. Effect of formal contracts, relational norms and trust on performance of joint research and development projects. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Su, C.; Fam, K.-S. Dealing with institutional distances in international marketing channels: Governance strategies that engender legitimacy and efficiency. J. Market. 2012, 76, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.C.; Teo, T.S. Contract performance in offshore systems development: Role of control mechanisms. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 115–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumineau, F.; Henderson, J.E. The influence of relational experience and contractual governance on the negotiation strategy in buyer–supplier disputes. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yeung, J.H.Y.; Zhang, M. The impact of trust and contract on innovation performance: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, G. The impact of relation-specific investment on channel relationship performance: Evidence from China. J. Strateg. Market. 2011, 19, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Yang, Z.; Jun, M. Cooperative norms, structural mechanisms, and supplier performance: Empirical evidence from chinese manufacturers. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2011, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, D. Farmer-buyer relationships in China: The effects of contracts, trust and market environment. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2011, 3, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, L. When do formal control and trust matter? A context-based analysis of the effects on marketing channel relationships in China. Ind. Market. Manag. 2011, 40, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Espallardo, M.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Sánchez-Pérez, M. Inter-organizational governance, learning and performance in supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.K.; Narasimhan, R.; Barbieri, P. Strategic interdependence, governance effectiveness and supplier performance: A dyadic case study investigation and theory development. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 537–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.; Mukherji, A.; Mukherji, J. Examining relational and resource influences on the performance of border region smes. Int. Bus. Rev. 2009, 18, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Z. Exploring the governance mechanisms of quasi-integration in buyer–supplier relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-M.J.; Liao, T.-J. The impact of governance mechanisms on transaction-specific investments in supplier-manufacturer relationships: A comparison of local and foreign manufacturers. Manag. Int. Rev. 2008, 48, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyau, A.; Spiller, A. The impact of supply chain governance structures on the inter-firm relationship performance in agribusiness. Zemed. Ekon. Praha 2008, 54, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A.; Lado, A.A.; Chen, I.J. Inter-organizational communication as a relational competency: Antecedents and performance outcomes in collaborative buyer–supplier relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Mahapatra, S.; Arlbjørn, J.S. Impact of relational norms, supplier development and trust on supplier performance. Oper. Manag. Res. 2008, 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.C.; James, W.L.; Hatten, K.J. Duration and relational choices: Time based effects of customer performance and environmental uncertainty on relational choice. Ind. Market. Manag. 2008, 37, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, M.J.; Katsikeas, C.S.; Bello, D.C. Drivers and performance outcomes of trust in international strategic alliances: The role of organizational complexity. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Nickerson, J.A. Interorganizational trust, governance choice, and exchange performance. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.C.; Edelman, L.F.; Hatten, K.J. Supplier performance improvements in relational exchanges. J. Bus. Ind. Market. 2007, 22, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Shenkar, O.; Luo, Y.; Nyaw, M.K. Do multiple parents help or hinder international joint venture performance? The mediating roles of contract completeness and partner cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1021–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terawatanavong, C.; Whitwell, G.J.; Widing, R.E. Buyer satisfaction with relational exchange across the relationship lifecycle. Eur. J. Market. 2007, 41, 915–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Cavusgil, S.T. Enhancing alliance performance: The effects of contractual-based versus relational-based governance. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, P.D.; Handfield, R.B.; Lawson, B.; Petersen, K.J. Creating supply chain relational capital: The impact of formal and informal socialization processes. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-M.J.; Liao, T.-J.; Lin, Z.-D. Formal governance mechanisms, relational governance mechanisms, and transaction-specific investments in supplier–manufacturer relationships. Ind. Market. Manag. 2006, 35, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.C.; Edelman, L.F.; Hatten, K.J. Relational exchange strategies, performance, uncertainty, and knowledge. J. Market. Theory Pract. 2006, 14, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sako, M. Does trust improve business performance. In Organisafional Trust: A Reader; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 267–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rooks, G.; Raub, W.; Tazelaar, F. Ex post problems in buyer–supplier transactions: Effects of transaction characteristics, social embeddedness, and contractual governance. J. Manag. Gov. 2006, 10, 239–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Delmas, M.; Tokat, Y. Deregulation, governance structures, and efficiency: The US electric utility sector. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Myers, M.B. The performance implications of strategic fit of relational norm governance strategies in global supply chain relationships. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2005, 36, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, T.Y. An empirical analysis of the influence of cross-relational impacts of strategy analysis on relationship performance in a business network context. J. Strateg. Market. 2005, 13, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopfer, H.; Kotzab, H.; Corsten, D.; Felde, J. Exploring the performance effects of key-supplier collaboration: An empirical investigation into swiss buyer-supplier relationships. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2005, 35, 445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, R.J.; Paulin, M.; Bergeron, J. Contractual governance, relational governance, and the performance of interfirm service exchanges: The influence of boundary-spanner closeness. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2005, 33, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, H.; Haugland, S.A. The evolution of governance mechanisms and negotiation strategies in fixed-duration interfirm relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1226–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoetker, G.P.; Mellewigt, T. Choice and Performance of Governance mechanisms: Matching Contractual and Relational Governance to Sources of Asset Specificity. 2004. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=621742 (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Claro, D.P.; Hagelaar, G.; Omta, O. The determinants of relational governance and performance: How to manage business relationships? Ind. Market. Manag. 2003, 32, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, D.C.; Chelariu, C.; Zhang, L. The antecedents and performance consequences of relationalism in export distribution channels. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cavusgil, S.T.; Roath, A.S. Manufacturer governance of foreign distributor relationships: Do relational norms enhance competitiveness in the export market? J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2003, 34, 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-R.; Chen, W.-R.; Kao, C. Determinants and performance impact of asymmetric governance structures in international joint ventures: An empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handfield, R.B.; Bechtel, C. The role of trust and relationship structure in improving supply chain responsiveness. Ind. Market. Manag. 2002, 31, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvik, A.; Andersen, O. The impact of vertical coordination on ex post transaction costs in domestic and international buyer-seller relationships. J. Int. Market. 2002, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buvik, A. Hybrid governance and governance performance in industrial purchasing relationships. Scand. J. Manag. 2002, 18, 567–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Contract, cooperation, and performance in international joint ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boger, S. Quality and contractual choice: A transaction cost approach to the polish hog market. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, P.; Singh, H.; Perlmutter, H. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, T.; Donaldson, B. Relationship governance structures and performance. J. Market. Manag. 2000, 16, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppo, L.; Zenger, T. Substitutes or complements? Exploring the relationship between formal contracts and relational governance. Poppo, Laura and Zenger, Todd, Substitutes or Complements? Exploring the Relationship between Formal Contracts and Relational Governance (17 April 2000). 2000. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=223518 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.223518 (accessed on 24 December 2017).

- Houston, M.B.; Johnson, S.A. Buyer–supplier contracts versus joint ventures: Determinants and consequences of transaction structure. J. Market. Res. 2000, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulin, M.; Perrien, J.; Ferguson, R. Relational contract norms and the effectiveness of commercial banking relationships. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Brown, J.R. Interdependency, contracting, and relational behavior in marketing channels. J. Market. 1996, 60, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, R.; Schmitz Whipple, J.; Frayer, D.J. Formal versus informal contracts: Achieving alliance success. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 1996, 26, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, P.S.; Kotabe, M.; Sahay, A. Trust and performance in cross-border marketing partnerships: A behavioral approach. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1996, 27, 1005–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlmann, J.; Spiller, A. The relationship between supply chain coordination and quality assurance systems: A case study approach on the german meat sector. In Proceedings of the System Dynamics and Innovation in Food Networks, Innsbruck-Igls, Austria, 18–22 February 2008; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhe, A. Strategic alliance structuring: A game theoretic and transaction cost examination of interfirm cooperation. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 794–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiblein, M.J.; Reuer, J.J.; Dalsace, F. Do make or buy decisions matter? The influence of organizational governance on technological performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B.; Clark, D.N. Resource-Based Theory: Creating and Sustaining Competitive Advantage; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Lumineau, F. Revisiting the interplay between contractual and relational governance: A qualitative and meta-analytic investigation. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quality Criteria | Reason for Inclusion/Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Year of publication | The paper published between 1996 and 2017. The scholarly works regarding governance structures and performance in empirical and conceptual perspectives significantly increased in the previous two decades but seminal or theoretical papers were from much earlier dates. |

| Articles in the English language | Most academic journals are published in English. |

| Thematic | Focus on governance structures and performance to narrow the research question and synthesize appropriate findings. |

| Scholarly published articles | To provide more rigorous knowledge in the field of governance structures and performance. |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

| Articles that do address corporate governance and corporate performance | The purpose of the systematic review is governance structures such as contractual and performance. |

| Unpublished articles | Peer-reviewed published articles are of good quality. |

| Conference paper, books, working papers, and technical reports | To ensure quality and consistency, all articles included are peer-reviewed |

| Sector | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Agrifood | 23 | 20.91% |

| Non-Agrifood | 75 | 68.18% |

| Non-Agrifood and Agrifood | 7 | 6.36% |

| Environment | 3 | 2.73% |

| Not stated | 2 | 1.82% |

| Total | 110 | 100% |

| Methods | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Case Studies | 7 | 6.36% |

| Surveys | 99 | 90.% |

| Experimental | 1 | 0.9% |

| Conceptual | 3 | 2.72% |

| Total | 110 | 99.98% |

| Author (s) | Theory | Methods | Industry/Sector | Governance structures | Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [92] | SNT | Case study | Agrifood | Informal Horizontal coordination Vertical coordination Hierarchal Trust and transparency | Agricultural efficiency | Trust is instrumental in reducing transaction costs, improving investments, improving the stability in relations and in stimulating learning, knowledge exchange, and innovation. Informal structures facilitate collaboration due to the flexibility in terms of enrolling new members. In the absence of formal control, informal networks are more open-ended and can support multiple ways of envisioning and operationalization. |

| [93] | TCT | Case Study | Agrifood | Formal contract | Quality | Quality standards and other obligations are not settled in the contract, being orally agreed between parties (relational). Contracts improve the supply of high-quality milk. |

| [113] | - | Survey | Agrifood | Formal Informal | Profitability Efficiency | Farmers associated with informal structures earn more profit than private processors. Formal structure suffers from low compliance rates probably due to poor governance and enforcement mechanisms. |

| [19] | - | Survey | Agrifood | Cooperation (Trust) Informal | Relationship Satisfaction | Trust plays an important role in enhancing cooperation. Trust is perceived as an important aspect for solving commitment problems that more often resort to close interpersonal relations to govern collaborative actions. |

| [114] | RBV | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Relational | Relationship | Both governance structures by balancing or complementing, significantly contributes to relationship performance. However, the complementing dimension only has a weak significant effect on relationship performance. |

| [115] | OCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Formal controls Informal controls | Alliance performance | In the absence of formal controls, alliance performance seems to benefit from high reliance on informal controls. At low levels of informal controls, the interaction is positive and marginally significant but at high levels, the interaction is insignificant. |

| [116] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contracts | Mutual strengthening | Complementary and substitutive dynamics between governance arrangements drive them into mutually strengthening or mutually debilitating relationships. Contractual arrangements can infuse cross-cultural partnerships with relational norms. |

| [117] | - | Survey | Environment | Relational | Environmental and Economic performance | Relational factors, that is, trust and cooperation, affect environmental and economic performance. |

| [101] | TCT, RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational | Innovation | Relational trust positively and significantly affects performance cooperative innovation. However, the relationship between formal contracts and performance cooperative innovation was insignificant. |

| [118] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Spot market Relational Contracts Mini integration | Price Volume Quality Resource allocation | Contracted production improves their capabilities and performance. Contracts assume different positions within the market hierarchy continuum. The cooperative combines market-like and hybrid values for price, quality, and resources allocation. |

| [119] | - | Survey | Environment | Formal Informal | Economic value | The existence of informal norms may decrease the profit of the formal arrangement. |

| [120] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Relational Contract | Effectiveness | Relational governance displays a greater influence on performance than contractual. However, contractual appears to be complementary to relational governance. |

| [121] | - | Survey | Agrifood | Vertical integration Contract | Yield and revenue | The vertically integrated structure has significantly higher yields than non-integrated farms. Vertically integrated and contract farms have higher yields and revenue than non-integrated farms. |

| [122] | RET, TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contract | On-time delivery Delivery consistency Quality Cost control Volume and scheduling flexibility Competition intensity | Contractual appeared more important than relational in affecting performance. Public selection and contractual control have a negative effect on supplier performance. Public selection and relational control have a positive effect on supplier performance. |

| [100] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational | Satisfaction Financial | Although relational norms enhance satisfaction more effectively than contracts, the effect on financial performance is not significantly different. |

| [123] | Channel theory | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Flexibility Relationship | Relational norms have a positive impact on an exporter's performance results. |

| [124] | Network theory, Equity theory | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Social control Contracts | Relationship performance | Social enforcement positively affects coordination. Yet negatively impacts perceived inequity and improves performance. Contracts positively and significantly impact on perceived inequity but the impact on coordination and performance is not significant. |

| [125] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Relational | Quality, Satisfaction, Effective, Efficiency, Responsive Reduce opportunism | Relational governance is effective in restricting opportunism because if the firms seek to reduce opportunism, inter-firm trust and relational norms are important means. Contractual governance has a stronger impact on the overall project performance than the relational governance. |

| [111] | - | Experimental | Non-Agrifood | Trust (relational) | Chain performance | Trust encourages collaboration across the chain, although the results revealed a positive effect, the degree of interdependence on the relationship between trust and performance in the chain shows that such an effect is not statistically significant. |

| [110] | SET | Conceptual | Environmental | Informal Formal | Environmental performance | Formal and informal governance mechanisms complement each other to positively affect environmental performance. |

| [96] | - | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Contract | Relationship | The stronger the contract monitoring, the weaker the negative association between contract violation and relationship performance. |

| [126] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contract | Export performance | Relational governance contributes positively to export performance, while contract control leads negatively to export performance. |

| [127] | SET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational Vertical integration | Governance costs Relationship | Interactional justice has a negative and significant effect on opportunism. Distributive justice has a significant negative effect on opportunism whereas governance costs increase more significantly because of strong form opportunism. |

| [97] | - | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Relational Vertical integration | Reduce opportunism Satisfaction | Relational norms have a negative effect on opportunism, but the effect of collaborative activities is contingent on the level of consistency between the relational norms and collaborative activities. |

| [128] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Market sourcing Contract Solidarity Norms/relational | Supplier’s performance | The monitoring contract has a significant effect on performance. Solidarity norms enhance performance in both concurrent and singular sourcing. |

| [20] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Control Social | Cooperative performance | There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between formal control and cooperative performance. Relational has a consistent effect on cooperative performance. |

| [129] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract | Fair exchange | Contractual design goes beyond its safeguarding function to establish a fair frame of reference. |

| [130] | TCT, RBV, RDT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Customer satisfaction | The impact of relational norms on customer satisfaction is bridged by the perceived service quality and customer trust. |

| [71] | TCT, RBV | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational (trust) Contracts | Relationship and Economic performance | Trust is positively associated with economic performance whereas contracts are marginally associated with economic performance. |

| [131] | OT | Survey | Agrifood | Integration | Financial Organizational Strategic | Internal integration and buyer-supplier relationship coordination are significantly related to firm performance in both relationships. |

| [132] | RBV | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Knowledge | Contracts have a significant and positive effect on explicit knowledge. |

| [102] | TCT, RBV | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational norms | Commitment Satisfaction | Formal contracts have a negative relationship on customer commitment. Also, the relationship between formal contracts and customer satisfaction is insignificant. The relational has an indirect positive effect on commitment and satisfaction. |

| [70] | TCT, RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Reduce opportunism | Where legal institutions are weak, detailed contracts are ineffective in curtailing partner opportunism. Under such circumstances, relational governance provides a proxy for legal institutions to ensure contract execution. Relational governance complements detailed contracts but substitutes for centralized control in curtailing opportunism. |

| [73] | IT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Relational | Firm performance | Performance benefits of relational governance are reinforced at higher degrees of informal institutional distance. Contrastingly, contractual governance is found to have a complementary relationship, with performance gains. |

| [108] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Revenues; Quality; Reduced time; Generate new customers; Customer satisfaction; Recognition; Long-term relationship | With mutual trust, relational embeddedness, and relational commitment, each contribute to the overall alliance performance. |

| [133] | CT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contractual | Satisfaction | The relational and contractual substitute for BPO satisfaction. |

| [134] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational norms Trust | Set of cost Time Goal fulfillment | Relational norms are more forceful in improving performance than contractual mechanisms. |

| [135] | IT, TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contractual | Selling/market Economic | The relational has a positive and significant effect on channel performance. A combination of contractual and relational governance enhances channel performance. |

| [136] | TCT, RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational | Cost Quality Knowledge integration | Contract and relational governance are significantly related to quality performance. |

| [137] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contractual | Negotiation strategy | Increasing contractual governance weakens the positive effect of cooperative relational experience on cooperative negotiation strategy. |

| [138] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Trust | Innovation | Contracts and trust have a major effect on a firm’s innovation performance |

| [107] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Spot market Relational Contract | Quality management practices (QMP) | Contractual governance has a significant positive impact on QMP. However, spot market transaction has a negative impact on the implementation of QMP. Results also reveal the significant positive impact of relational and trust on QMP. |

| [103] | SCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contracts | Innovation Reduce costs | Relational is positively and significantly related to cost reduction. Contracts positively moderate the relationship between relational and buyer innovation improvement. |

| [139] | TCT, RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Relationship | Relational trust exerts an adverse influence on the effectiveness of relationship learning. |

| [140] | SCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Cooperative norms Structural mechanism | Supplier’s performance | Cooperative norms positively influence both operational and informational linkages, but the norms have no significant and direct impact on supplier performance. Structural mechanisms have a significant and positive impact on performance. |

| [141] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Contracts Trust (relational) | Environmental uncertainty | There is a positive relationship between environmental uncertainty and contractual governance. |

| [142] | TCT, SCT | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Formal control Trust (relational) | Opportunism Long-term orientation | Formal control enhances long-term orientation and reduces opportunism in a weak relationship context. Trust (relational) reduces opportunistic behavior and enhances long-term relationships. |

| [143] | TCT, RBV | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Formal control Social control | Uncertainty Knowledge | Contracts reduce the uncertainty that shifts the risk to the controlled firm. Output and behavior control have an insignificant effect on performance. Social control and behavior control favors knowledge sharing, learning, and performance in the supply chain. |

| [104] | TCT | Case Study | Non-Agrifood | Contracts | Low ex ante and ex post costs | Contracts that were more specific than predicted lowered the ex post transactions costs and vice versa. |

| [13] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Formal control Relational | Knowledge acquisition | Indirect and direct relational mechanisms differentially affect the acquisition of tacit and explicit knowledge. Formal contracts enhance positive effects of relational mechanisms on the acquisition of explicit and tacit knowledge. Contractual specification increases the transfer of explicit knowledge. |

| [5] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Control Dominant power | Reduce opportunism | Administrative control and power did not show a significant impact on supplier opportunism. |

| [106] | SNT, TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Institutionalization Formal control Social control | Satisfaction Overall set goals Core competencies Competitive advantage | The length of cooperation on the use of social control mechanisms is positive and significant in international cooperation, but insignificant in domestic cooperation. Formal and social control in explaining cooperation performance are substitutes in domestic cooperation but have an insignificant relationship in international buyer–supplier relationships. |

| [36] | TCT | Case Study | Agrifood | Spot market Verbal agreement Formal contracts Equity-based contractsVertical integration | Quality management systems | The results show that different forms of governance structures largely relate to specific aspects of quality management systems. |

| [144] | RBV, TCT, SCT | Case Study | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Relational | Relational Operational performance | Contracts encourage practices such as strategic information exchange, asset-specific investments, collaborative initiatives, and social interactions to enhance governance effectiveness, which contributes to relationship building and superior operational performance. |

| [105] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Formal Relational | Financial Sales network | Formal contract is a reliance on financial parameters and the drafting and implementation of contracts. Formal governance enables coordination by enhancing the predictability of each party's action and structuring communication flow. Formal and relational governance depends on the assets involved in an alliance, with formal mechanisms best suited to property-based assets and relational governance best suited to knowledge-best assets. |

| [47] | PRT, TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Contracts Vertical coordination | Relationship sustainability | Significant results indicate that relationship sustainability is largely independent of the adopted contract type. |

| [145] | RBV | Survey | Agrifood | Relational | Overall performance | Overall performance is positively affected by relational components. |

| [23] | TCT, RET | Conceptual | Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Quality Efficiency Flexibility | Relational enhances efficiency, productivity, and effectiveness because costs of quantity and price negotiations are low due to mutual open disclosure of information concerning future business plans and costs. Formal contracts attempt to mitigate risk and uncertainty in exchange relationships which improves exchange performance. |

| [146] | TCT, RDT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Legal contracts Joint problem-solving Joint planning -integration Collaborative | commitment -Sales services -Delivery -Product quality -Total values | Collaborative communication positively affects supplier’s performance. Joint problem solving and collaborative communication significantly enhances the buyer’s commitment. |

| [147] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Formal | TSIs | The efficacy of different governance mechanisms, as shaped by local and foreign manufacturers, exerts varying degrees of impact on the suppliers’ transaction-specific investments. |

| [148] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Spot market Long-term relationships Contracts Vertical integration | Behavioral performance -Overall satisfaction -Commitment -Economic -Reduction in costs -Overall financial success | Economic performance is influenced by the type of governance structures used, whereas behavioral relationship performance is not. Marketing Contracts do not significantly differ from Spot Market in terms of the economic relationship performance. The economic performance of all the other governance structures improves as one uses a more coordinated governance structure except marketing contracts. |

| [98] | RBV | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Relational | Export performance | There is significant support for the critical role that the key relational variables trust, competence, and goodwill on a commitment to export performance. |

| [149] | Network theory | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational competency | Buyer and Supplier performance | Relational competency enhances buyers’ and suppliers’ performance with strong support for the notion of inter-organizational communication. |

| [150] | RBV, SET | Survey | - | Relational norms | Cost reduction Volume and Schedule flexibility | Relational norms such as trust have relatively higher correlations with overall performance. |

| [99] | Contingency theory | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Formal control Integration | Financial | In a predictable demand environment, formal control affects the chain process variability, thus giving financial results. Whereas, in an unpredictable demand environment, integration affects chain process variability, hence, leading to financial performance. |

| [151] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Customer performance | Customer performance improvement associated with supplier knowledge transfer and technological uncertainty are significant and positively related to relational governance. |

| [152] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Effectiveness Efficiency Responsiveness | Inter-partner trust is positively associated with alliance performance. |

| [153] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Trust | Exchange performance | The effect of inter-organizational trust on governance mode choice shapes exchange performance. Regardless of the governance mode chosen for an exchange, trust enhances exchange performance. |

| [154] | OT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational norms | Customer performance | Customers may achieve better performance through relational exchange, suppliers may not always reap reciprocal benefits. |

| [155] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Sales level, market share, profitability, quality management, customer service, reputation and product design | Relational is positively related to joint venture performance and the relationship is mediated by contract completeness and partner cooperation. |

| [156] | RET | Survey | Agrifood and Non-Agrifood | Relational | Satisfaction Commitment | Relational is associated with higher relationship satisfaction in the build-up and maturity phases while commitment is associated with higher relationship satisfaction in the maturity phase. |

| [34] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Quality assurance | The farmers are not convinced of the benefits of stricter vertical coordination and prefer to stay independent and take their own decisions. Despite the negative attitude towards contracts, the farmers agree to consider quality requirements of their production. |

| [157] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Market performance Alliance performance -Stability -Knowledge acquisition -Strength | Relational is more effective and influential than contractual in strengthening interfirm partnership, stabilizing alliance relationship, and acquiring knowledge from partners. Contracts may serve as the basis of partnership, but it is relational governance that could leverage alliance performance. |

| [158] | RCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Formal Informal | Relationship | Informal socialization processes are important in creating relational capital which, in return, improves supplier relationship performance. |

| [159] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Formal | TSIs | Formal and relational governance positively affect suppliers’ tendencies to make specialized transaction specific investments (TSIs). |

| [160] | OT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Purchasing Production | Relational exchange is significantly and positively related to the purchase and production performance. |

| [161] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Reduce costs Profit margins Just in time delivery Problem-solving | The only type of trust with which the first measure of supplier performance and cost reduction is associated significantly with is goodwill trust. |

| [162] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contract | Delivery delays Inferior quality Insufficient service | The occurrence of performance problems does not support the hypotheses on effects on contractual governance. Whereas there is consistent support for hypotheses on the effects of relational. |

| [163] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Vertical integration | Productive efficiency | Vertically integrated firms are more sufficient than firms that adopt a hybrid form of governance structures. Combining vertical integration with contracting improves production efficiency. |

| [22] | TCT | Case Study | Agrifood | Hierarchy Market | Quality | In hierarchy-like modes of organization, reputational capital is the main quality assurance device, whereas market-like governance is more prevalent in cases with public certification. |

| [164] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Sales growth Profit growth Profitability | Results indicate firm performance is enhanced when the relational norms of information exchange and solidarity are fit to culturally founded norm expectations. |

| [165] | OT, RBV | Survey | Agrifood | Relational Contracts | Relationship performance | Greater degree of control or less dependent parties in business relationships would have more bargaining power and hence, could contribute to relationship performance. |

| [166] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Collaboration Trust Dependence | Innovation, Cost reduction, Financial | Suppliers’ collaboration has a positive effect on buyers’ performance. |

| [167] | TCT, TRT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contractual | Exchange performance | Relational is the predominate governance associated with exchange performance Contractual is also associated with exchange performance but to a lesser extent. Relational exchanges between commercial banks and their clients are important with respect to future revenue generation and profits emanating from satisfied business clients continuing to purchase bank services and referring other clients. |

| [168] | CT Negotiation theory | Case Study | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Price incentives Authority Trust norms | A cooperative characterized by trust and relational norms can develop even in a temporally delimited relationship. There are complementary relationships between governance mechanisms where trust and control can coexist and jointly contribute to partner confidence |

| [169] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contract | Knowledge | No significant relationship between the presence of knowledge assets and the performance of contractual governance mechanisms. |

| [170] | - | Survey | Agrifood | Relational -Joint planning -Joint problem-solving | Sales growth rate Perceived satisfaction | Joint planning has a significant positive effect on sales growth but has no significant link to perceived satisfaction, while joint problem-solving correlates positively with perceived satisfaction and sales growth |

| [171] | RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Distributor’s performance | Relational exchange is associated with greater distributors’ performance on behalf of the manufacturer in the foreign market. |

| [172] | RET | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Competitive advantage | Relational norms are distinct constructs. Each has a unique influence on the firm’s ability to create relationship specific adaptions Relation norms reside not only in their influence on tangible performance (for instance, competitive position) but also in their ability to generate intangible relational assets like trust. |

| [173] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Joint venture | Venture performance | International joint venture operating under an asymmetric governance revealed no significant differences compared to those operating under a symmetric structure. |

| [174] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Relational | Responsiveness | When buyers do not have a great deal of control over their suppliers, working to build trust within the relationship improves supplier responsiveness. |

| [14] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Exchange performance Satisfaction | Contracts and relational governance function as complements. Both improve exchange performance and satisfaction. |

| [175] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Vertical coordination | Reduce ex post transaction cost | Vertical coordination reduces ex post transaction significantly more in international buyer-seller relationships than in domestic channel dyads. |

| [176] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Vertical coordination | Efficacy | Greater vertical coordination reduces ex post transaction costs significantly. |

| [177] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contracts Cooperation | Domestic and export sales | Contracts and cooperation not only have an effect on joint venture performance but also have a significant interaction with each other to stimulate performance. The contract is important but diminishes in relation to performance while relational sustains it's linear and significant contribution to performance. |

| [178] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Contracts | Quality | Larger producers differ from traders characterized by formal contracts to influence high quality. |

| [72] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Relationship | The effect of governance structures on performance relying on legal bonds is conditional on additional governance apparatuses; that is, the plural forms. Relational governance enhances relationship performance. |

| [179] | RCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Reduce opportunism | Relational governance based on mutual trust and interaction at the individual level between alliance partners creates a basis for learning and know-how transfer across the exchange interface. |

| [180] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Market Hierarchical Recurrent | Satisfaction Profitability Sales Quality | Relational relationships perform significantly better than the other relationship types across most of the financial performance measures. However, performance does vary across the four governance structures. |

| [181] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contract | Cost Quality Responsiveness | Both relational and contractual complexity deliver higher levels of satisfaction with exchange performance. |

| [182] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contract Joint Venture | Financial consequence | Vertical joint ventures between buyers and suppliers are economically similar to contracts. Buyers and suppliers are more likely to form a joint venture versus a simple contract when the supplier’s degree of asset specificity is high. |

| [8] | TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contacts Relational | Commitment | Relational norms increase the retailer's perception of supplier commitment, whereas explicit contracts are associated with perceptions of lower supplier commitment. |

| [109] | TCT | Conceptual | - | Vertical integration Contract Market | Efficiency Effectiveness | Using asset specificity to determine how a manufacturer can vertically coordinate the supply chain addresses the issue of transaction cost but does not directly address the issue of performance. |

| [183] | RET, TCT | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Effectiveness | The relational norms assessed by the client representative are all significantly correlated to the index of effectiveness. |

| [184] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Contractual Interdependency Relational | Business performance Sales, Profit, Growth, Labor, and Productivity | Bilateral dependency between the wholesaler and supplier is high which leads to more reliance on the normative contracts and improve performance. |

| [185] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational Contracts | Alliance success | Contract in achieving and maintaining a successful logistical alliance is of paramount importance. |

| [186] | - | Survey | Non-Agrifood | Relational | Market performance | Bilateral relational norms and informal monitoring mechanisms build and improve market performance of international partnerships. |

| [187] | - | Survey | Agrifood | Relational | Economic performance Quality and safety | A negative relation that exists between safety and governance contradicts the original assumption. |

| [95] | RBV, TCT, AT, RDT, ST | Survey | Agrifood | Relational Contracts Transactional | Financial Operational | Contractual, relational, and transactional aspects, have a positive influence on the operational and financial performance. |

| [94] | TCT | Survey | Agrifood | Contracts Relational | Food quality and safety | Contracts and experience have significant effects in minimizing food quality and safety hazards. |

| Theories Applied | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Transaction Cost Theory | 57 | 50.00% |

| Resource Based-View | 12 | 10.52% |

| Relational Exchange Theory | 16 | 14.04% |

| Social Network Theory | 11 | 9.65% |

| Other Theories | 18 | 15.78% |

| Total | 114 | 100% |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kataike, J.; Gellynck, X. 22 Years of Governance Structures and Performance: What Has Been Achieved in Agrifood Chains and Beyond? A Review. Agriculture 2018, 8, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8040051

Kataike J, Gellynck X. 22 Years of Governance Structures and Performance: What Has Been Achieved in Agrifood Chains and Beyond? A Review. Agriculture. 2018; 8(4):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8040051

Chicago/Turabian StyleKataike, Joanita, and Xavier Gellynck. 2018. "22 Years of Governance Structures and Performance: What Has Been Achieved in Agrifood Chains and Beyond? A Review" Agriculture 8, no. 4: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8040051

APA StyleKataike, J., & Gellynck, X. (2018). 22 Years of Governance Structures and Performance: What Has Been Achieved in Agrifood Chains and Beyond? A Review. Agriculture, 8(4), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture8040051