Priestia megaterium Inoculation Enhances the Stability of the Soil Bacterial Network and Promotes Cucumber Growth in a Newly Established Greenhouse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Greenhouse Experiment

2.2. Soil Samples Collection and Soil Nutrients Determination

2.3. Plant Samples Collection and Plant P and K Accumulation Determination

2.4. HPLC Analysis of Phytohormone Produced by Strain P. megaterium

2.5. Real-Time PCR Quantification of the Number of P. megaterium Copies and Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of P. megaterium on Cucumber Growth and Yields

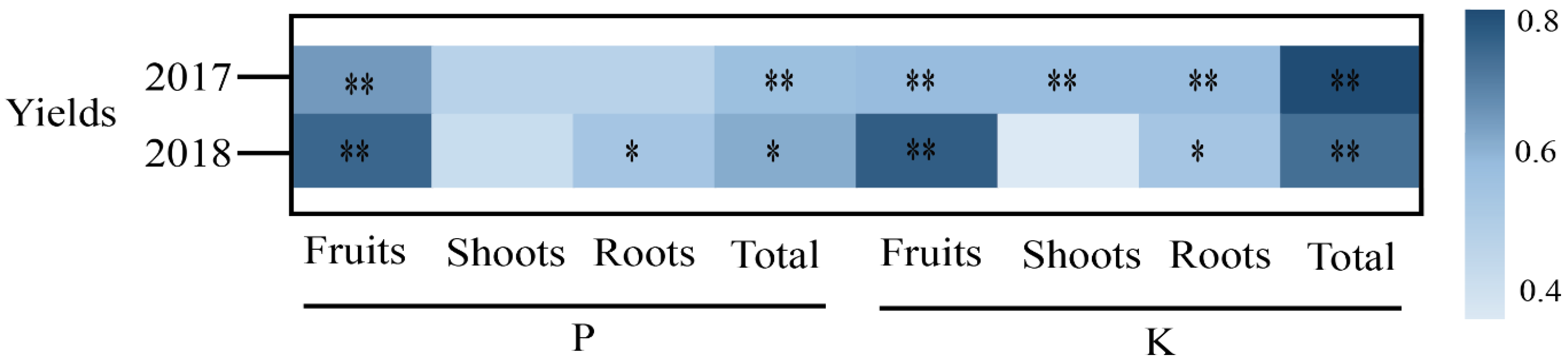

3.2. Relationships Between Bioavailability of P and K and Cucumber Yields

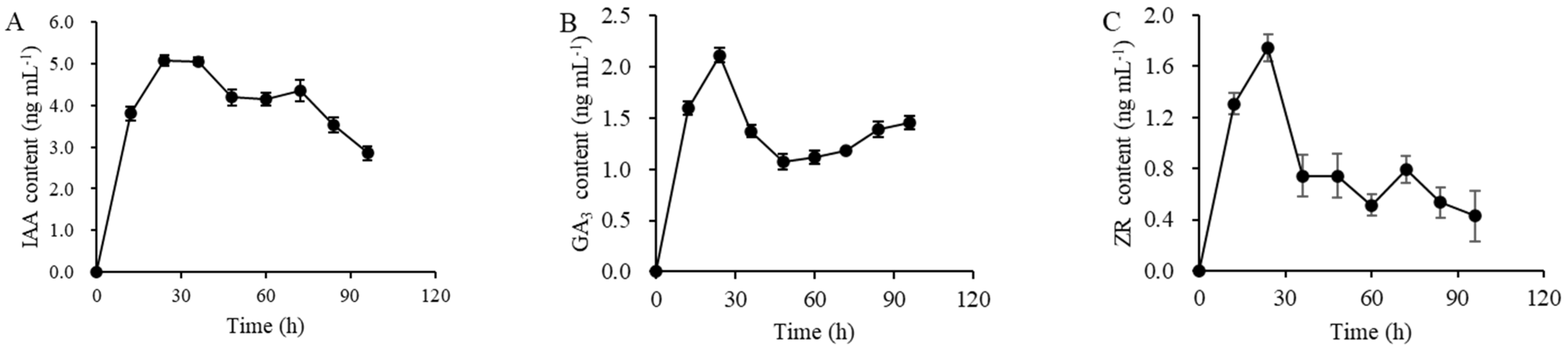

3.3. Analysis of Phytohormones Produced by P. megaterium

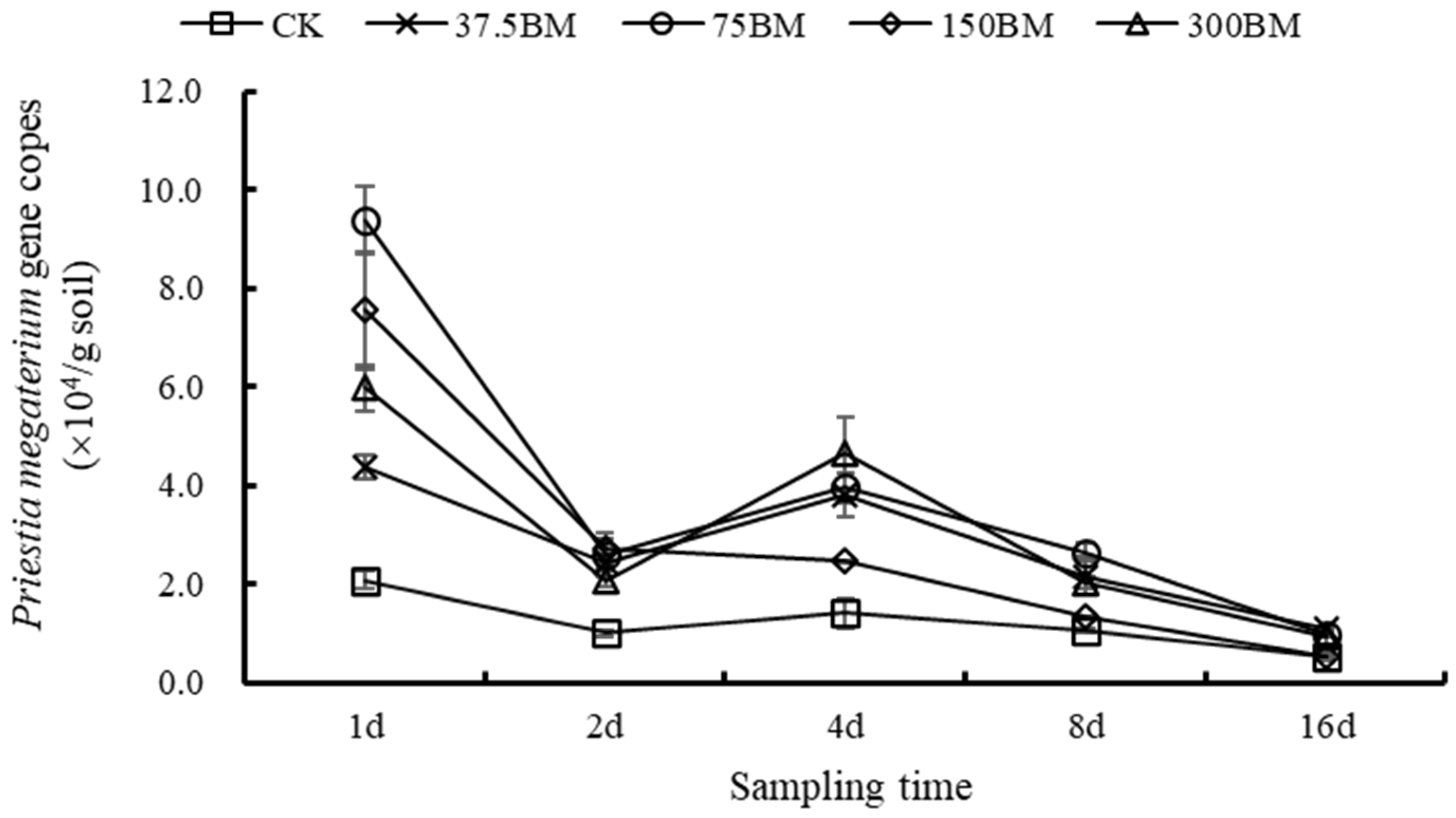

3.4. q-PCR Quantitative Analysis of P. megaterium

3.5. Effects of P. megaterium on Soil Bacterial Community Diversity

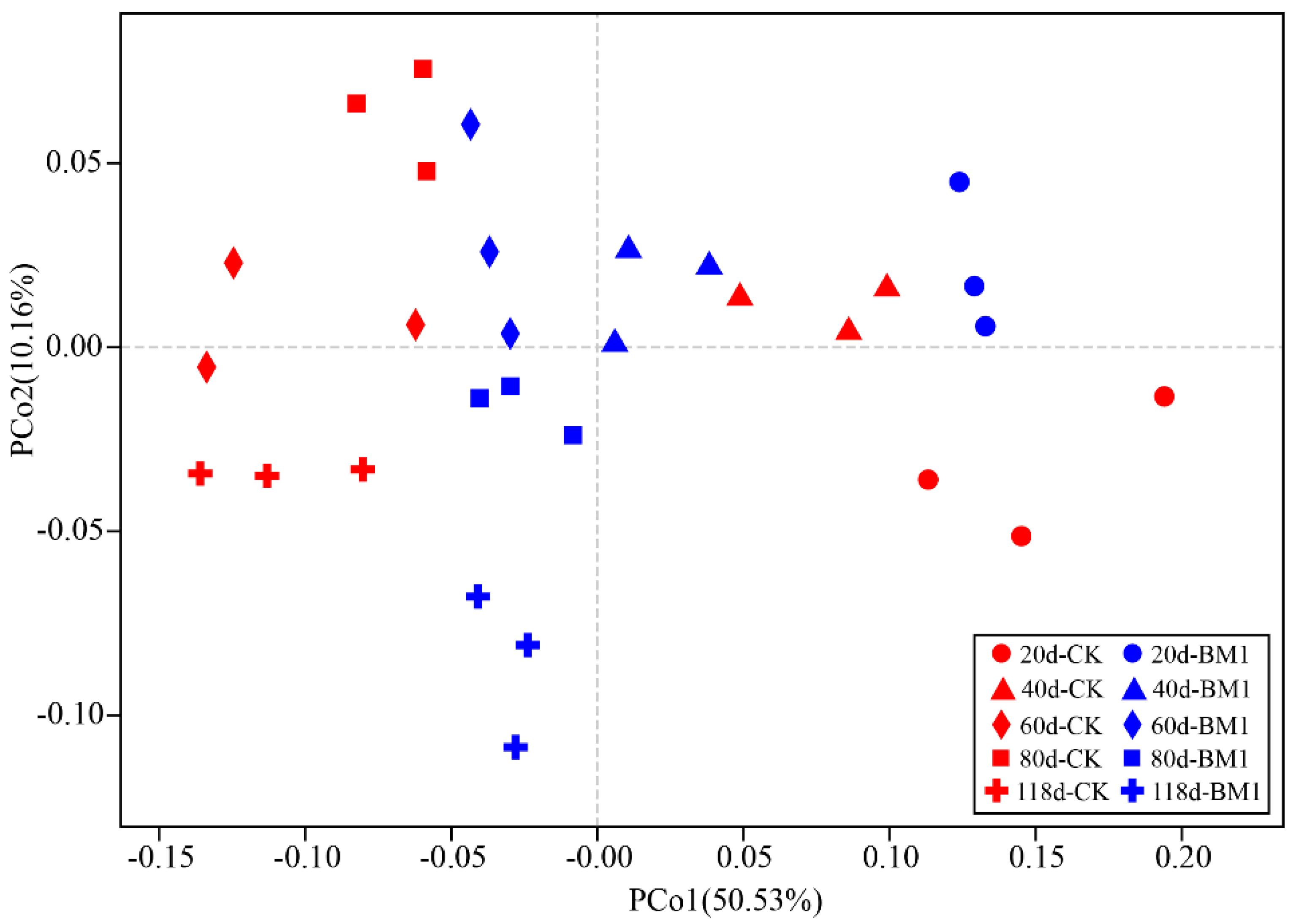

3.6. Effects of P. megaterium on Soil Bacterial Community Structure

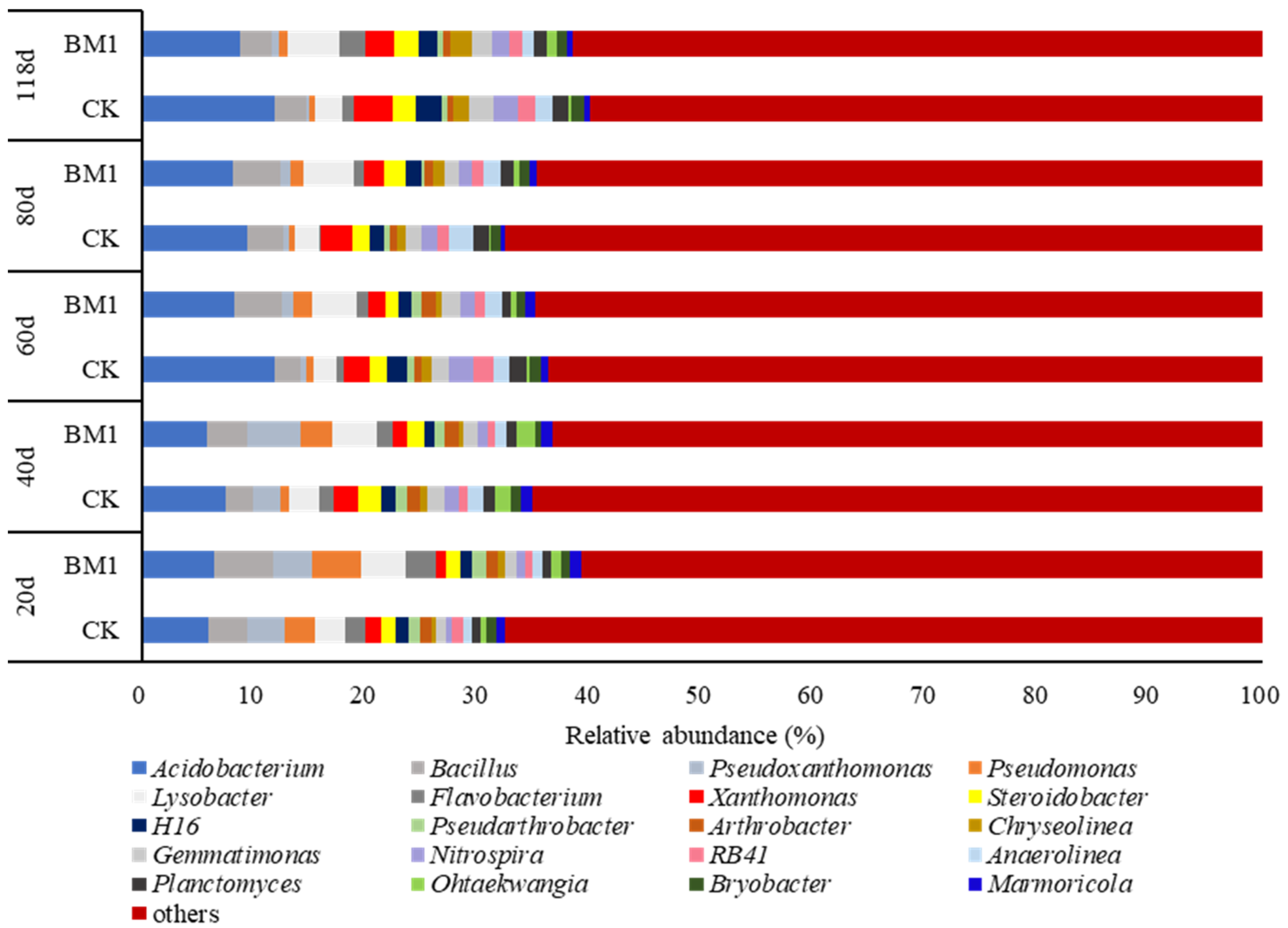

3.7. Effects of P. megaterium on Soil Bacterial Community Composition

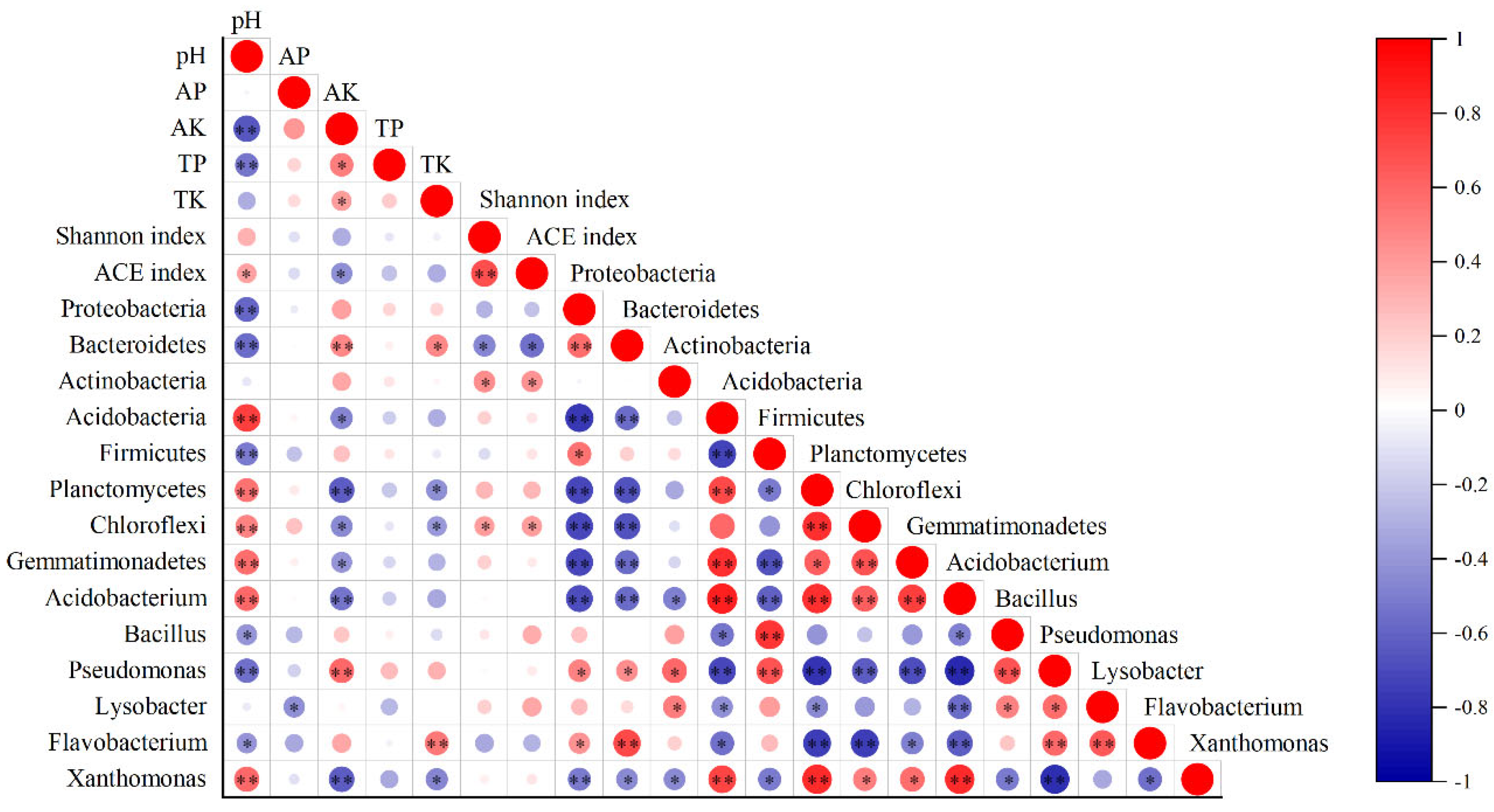

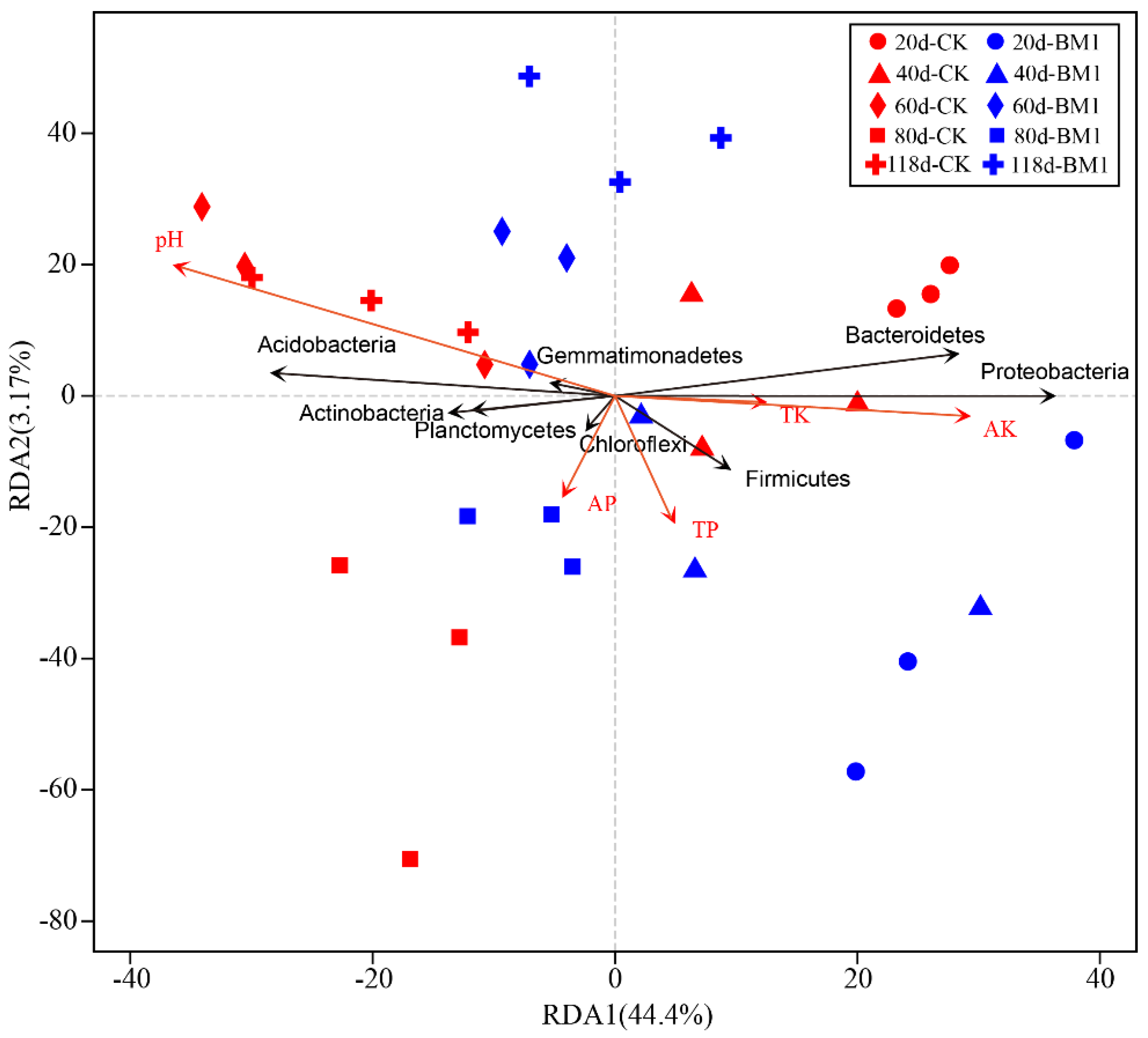

3.8. Relationship Between the Soil Bacterial Community Structure and Soil Properties

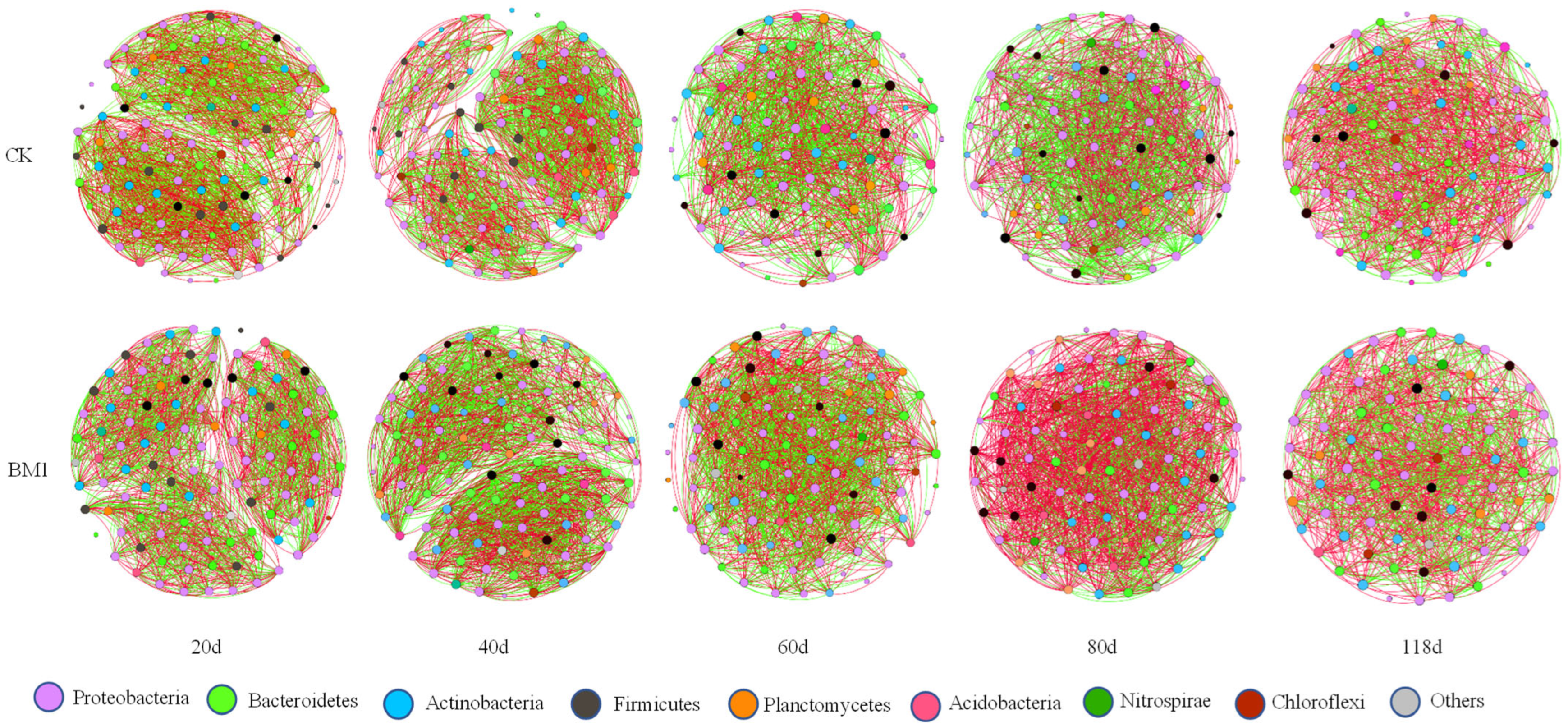

3.9. Effects of P. megaterium on Co-Occurrence Networks of Soil Bacterial Community

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Gan, Y.; Lupwayi, N.; Hamel, C. Influence of introduced arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphorus sources on plant traits, soil properties, and rhizosphere microbial communities in organic legume-flax rotation. Plant Soil 2019, 443, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namis, E.; Mohamed, B.; Guo-Chun, D.; Dinah, N.; Nino, W.; Ellen, K.; Günter, N.; Uwe, L.; Leo, V.; Kornelia, S. Enhanced tomato plant growth in soil under reduced P supply through microbial inoculants and microbiome shifts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpoor Kalkhajeh, Y.; Huang, B.; Hu, W.; Ma, C.; Gao, H.; Thompson, M.L.; Bruun Hansen, H.C. Environmental soil quality and vegetable safety under current greenhouse vegetable production management in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 307, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasupo, I.O.; Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Yan, Y.; He, C. Chili residue and Bacillus laterosporus synergy impacts soil bacterial microbiome and agronomic performance of leaf mustard (Brassica juncea L.) in a solar greenhouse. Plant Soil 2022, 479, 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability. Microbiome 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Fu, X.; Zhou, X.; Guo, M.; Wu, F. Effects of seven different companion plants on cucumber productivity, soil chemical characteristics and Pseudomonas community. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mao, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Di, H.J.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Response of soil microbial communities to continuously mono-cropped cucumber under greenhouse conditions in a calcareous soil of north China. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2446–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Qiu, Y.; Yao, T.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X. Effects of PGPR microbial inoculants on the growth and soil properties of Avena sativa, Medicago sativa, and Cucumis sativus seedlings. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 199, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, J.; Mark Ibekwe, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C.-H. Influence of Bacillus subtilis B068150 on cucumber rhizosphere microbial composition as a plant protective agent. Plant Soil 2018, 429, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ni, T.; Li, J.; Lu, Q.; Fang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Li, R.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q. Effects of organic–inorganic compound fertilizer with reduced chemical fertilizer application on crop yields, soil biological activity and bacterial community structure in a rice–wheat cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsilp, N.; Nimnoi, P. Inoculation of Ensifer fredii strain LP2/20 immobilized in agar results in growth promotion and alteration of bacterial community structure of Chinese kale planted soil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, F.; E, Y.; Yuan, J.; Raza, W.; Huang, Q.; Shen, Q. Long-term application of bioorganic fertilizers improved soil biochemical properties and microbial communities of an apple orchard soil. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conversa, G.; Lazzizera, C.; Bonasia, A.; Elia, A. Yield and phosphorus uptake of a processing tomato crop grown at different phosphorus levels in a calcareous soil as affected by mycorrhizal inoculation under field conditions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2012, 49, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salvo, L.P.; Cellucci, G.C.; Carlino, M.E.; García de Salamone, I.E. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation and nitrogen fertilization increase maize (Zea mays L.) grain yield and modified rhizosphere microbial communities. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 126, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Padda, K.P.; Chanway, C.P. Evidence of nitrogen fixation and growth promotion in canola (Brassica napus L.) by an endophytic diazotroph Paenibacillus polymyxa P2b-2R. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 52, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Shen, Q.; Ran, W.; Xiao, T.; Xu, D.; Xu, Y. Inoculation of soil by Bacillus subtilis Y-IVI improves plant growth and colonization of the rhizosphere and interior tissues of muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.). Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Raza, W.; Yuan, J.; Huang, R.; Ruan, Y.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain W19 can promote growth and yield and suppress Fusarium Wilt in banana under greenhouse and field conditions. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Feng, Y.; Rong, N. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus megaterium JX285 isolated from Camellia oleifera rhizosphere. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019, 79, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xing, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, B. Low-temperature straw biochar: Sustainable approach for sustaining higher survival of B. megaterium and managing phosphorus deficiency in the soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 830, 154790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antil, S.; Kumar, R.; Pathak, D.V.; Kumar, A.; Panwar, A.; Kumari, A. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria—Bacillus cereus KMT-5 and B. megaterium KMT-8 effectively suppressed Meloidogyne javanica infection. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 174, 104419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, H.; Mungai, N.W.; Thuita, M.; Hamba, Y.; Masso, C. Co-inoculation Effect of Rhizobia and Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria on Common Bean Growth in a Low Phosphorus Soil. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Yao, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, W.; He, W.; Dai, C. Endophytic Bacillus megaterium triggers salicylic acid-dependent resistance and improves the rhizosphere bacterial community to mitigate rice spikelet rot disease. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 156, 103710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.Y.O.; de Oliveira, C.M.; da Silva, P.R.A.; de Melo, L.H.V.; do Carmo, M.G.F.; Baldani, J.I. Taxonomical and functional characterization of Bacillus strains isolated from tomato plants and their biocontrol activity against races 1, 2 and 3 of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Lycopersici. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 120, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mao, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Di, H.J.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Li, B. The application of Bacillus Megaterium alters soil microbial community composition, bioavailability of soil phosphorus and potassium, and cucumber growth in the plastic shed system of North China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 307, 107236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D.R.; Rathore, A.P.; Sharma, S. Effect of halotolerant plant growth promoting rhizobacteria inoculation on soil microbial community structure and nutrients. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 150, 103461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Pan, L.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L. Comparison of greenhouse and open field cultivations across China: Soil characteristics, contamination and microbial diversity. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 243, 1509–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Du, N.; Shu, S.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Guo, S. Paenibacillus polymyxa NSY50 suppresses Fusarium wilt in cucumbers by regulating the rhizospheric microbial community. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, X. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens B1408 suppresses Fusarium wilt in cucumber by regulating the rhizosphere microbial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2019, 136, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Tian, H.; Xiao, Q.; Jiang, H. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil microbial community structure and analysis of soil properties with vegetable planted at different years under greenhouse conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 187, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Walder, F.; Buchi, L.; Meyer, M.; Held, A.Y.; Gattinger, A.; Keller, T.; Charles, R.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Agricultural intensification reduces microbial network complexity and the abundance of keystone taxa in roots. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1722–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, F.T.; Griffiths, R.I.; Bailey, M.; Craig, H.; Girlanda, M.; Gweon, H.S.; Hallin, S.; Kaisermann, A.; Keith, A.M.; Kretzschmar, M.; et al. Soil bacterial networks are less stable under drought than fungal networks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mao, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Tao, B.; Qi, Y.; Ma, L.; et al. A Genomic Analysis of Bacillus megaterium HT517 Reveals the Genetic Basis of Its Abilities to Promote Growth and Control Disease in Greenhouse Tomato. Int. J. Genom. 2022, 2022, 2093029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Song, N. Biochar and vermicompost improve the soil properties and the yield and quality of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) grown in plastic shed soil continuously cropped for different years. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 315, 107425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Shen, J.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Jiang, B.; Wu, J. Effects of biochar amendment on net greenhouse gas emissions and soil fertility in a double rice cropping system: A 4-year field experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 262, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, T.; Lin, J.; Fu, W.; Feng, B.; Li, G.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Tao, L.; et al. Functions of Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium in Energy Status and Their Influences on Rice Growth and Development. Rice Sci. 2022, 29, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Contribution of indole-3-acetic acid in the plant growth promotion by the rhizospheric strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2014, 51, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M.Z.; Hu, A.; Feng, C.; Maeda, T.; Shirai, Y.; Hassan, M.A.; Yu, C.P. Influence of pretreated activated sludge for electricity generation in microbial fuel cell application. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 145, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yang, Y.; Guan, P.; Geng, L.; Ma, L.; Di, H.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Remediation of organic amendments on soil salinization: Focusing on the relationship between soil salts and microbial communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 239, 113616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Dong, K.; Geisen, S.; Yang, W.; Friman, V.P. The effect of microbial inoculant origin on the rhizosphere bacterial community composition and plant growth-promotion. Plant Soil 2020, 454, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wei, S.; Su, D.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Luo, Z.; Shen, X.; Lai, Y.; Jamil, A.; Tong, J. Comparison of the rhizosphere soil microbial community structure and diversity between powdery mildew-infected and noninfected strawberry plants in a greenhouse by high-throughput sequencing technology. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1724–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Di, H.J.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Effects of microbial inoculants on phosphorus and potassium availability, bacterial community composition, and chili pepper growth in a calcareous soil: A greenhouse study. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 3597–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, N.; Li, H.; Jiao, J. Interactions of bacterial-feeding nematodes and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)-producing bacteria promotes growth of Arabidopsis thaliana by regulating soil auxin status. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, N.; Huang, Q.; Raza, W.; Li, R.; Vivanco, J.M.; Shen, Q. Organic acids from root exudates of banana help root colonization of PGPR strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 13438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, N.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, X.; Shen, B.; Shen, Q. Bacillus subtilis SQR 9 can control Fusarium wilt in cucumber by colonizing plant roots. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Razavi, B.S.; Yao, S.; Hao, C.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Tian, J. Contrasting mechanisms of nutrient mobilization in rhizosphere hotspots driven by straw and biochar amendment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 187, 109212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodharan, K.; Palaniyandi, S.A.; Le, B.; Suh, J.W.; Yang, S.H. Streptomyces sp. strain SK68, isolated from peanut rhizosphere, promotes growth and alleviates salt stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom). J. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Effects of different plant root exudates and their organic acid components on chemotaxis, biofilm formation and colonization by beneficial rhizosphere-associated bacterial strains. Plant Soil 2013, 374, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Saharan, B.; Nain, L.; Prasanna, R.; Shivay, Y.S. Enhancing micronutrient uptake and yield of wheat through bacterial PGPR consortia. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2012, 58, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.; Gulluce, M.; von Wirén, N.; Sahin, F. Yield promotion and phosphorus solubilization by plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria in extensive wheat production in Turkey. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2012, 175, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ruan, Y.; Chao, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Rhizosphere microbial community manipulated by 2 years of consecutive biofertilizer application associated with banana Fusarium wilt disease suppression. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2015, 51, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Paulitz, T.C.; Steinberg, C.; Alabouvette, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 2008, 321, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Schlaeppi, K.; Banerjee, S.; Kuramae, E.E.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ruan, Y.; Tao, C.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Continous application of bioorganic fertilizer induced resilient culturable bacteria community associated with banana Fusarium wilt suppression. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Samaddar, S.; Anandham, R.; Kang, Y.; Kim, K.; Selvakumar, G.; Sa, T. Beneficial soil bacterium Pseudomonas frederiksbergensis OS261 augments salt tolerance and promotes red pepper plant growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukanova, K.A.; Chebotar, V.K.; Meyer, J.J.M.; Bibikova, T.N. Effect of plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria on plant hormone homeostasis. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, J.; Stevens, L.H.; Wiegers, G.L.; Davelaar, E.; Nijhuis, E.H. Biological control of Pythium aphanidermatum in cucumber with a combined application of Lysobacter enzymogenes strain 3.1T8 and chitosan. Biol. Control 2009, 48, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, E.C.; Cleenwerck, I.; Maes, M.; Baeyen, S.; Van Malderghem, C.; De Vos, P.; Cottyn, B. Genetic characterization of strains named as Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. dieffenbachiae leads to a taxonomic revision of the X. axonopodis species complex. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principe, A.; Fernandez, M.; Torasso, M.; Godino, A.; Fischer, S. Effectiveness of tailocins produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens SF4c in controlling the bacterial-spot disease in tomatoes caused by Xanthomonas vesicatoria. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 212, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krober, M.; Wibberg, D.; Grosch, R.; Eikmeyer, F.; Verwaaijen, B.; Chowdhury, S.P.; Hartmann, A.; Puhler, A.; Schluter, A. Effect of the strain Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 on the microbial community in the rhizosphere of lettuce under field conditions analyzed by whole metagenome sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, H.; Zeng, H.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Xu, D.; et al. Effects of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ZM9 on bacterial wilt and rhizosphere microbial communities of tobacco. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 103, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawarda, P.C.; Le Roux, X.; Dirk van Elsas, J.; Salles, J.F. Deliberate introduction of invisible invaders: A critical appraisal of the impact of microbial inoculants on soil microbial communities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Richardson, A.E.; O’Callaghan, M.; DeAngelis, K.M.; Jones, E.E.; Stewart, A.; Firestone, M.K.; Condron, L.M. Effects of selected root exudate components on soil bacterial communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 77, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, S.; Zhalnina, K.; Kosina, S.; Northen, T.R.; Sasse, J. The core metabolome and root exudation dynamics of three phylogenetically distinct plant species. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, T.C.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Tiemann, L.K.; Friesen, M.L.; Evans, S.E. Plant root exudates and rhizosphere bacterial communities shift with neighbor context. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 108753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Sun, B.; Wang, B. Agricultural intensification weakens the soil health index and stability of microbial networks. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 339, 108118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Kong, L.; Tong, L.; Cao, H.; Zhou, H.; Lv, Y. Long-term application of Bio-compost increased soil microbial community diversity and altered its composition and network. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.M.; Guo, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Ning, D.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Wang, H.; Cai, K.; Xiao, R.; Xu, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, J.; Huang, F. Characterization of soil microbial community activity and structure for reducing available Cd by rice straw biochar and Bacillus cereus RC-1. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 156202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Growing Season | Treatments | Yields | Fruits | Shoots | Roots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | CK | 132.7 ± 2.0 b | 5759.0 ± 85.6 c | 5853.0 ± 34.7 b | 316.7 ± 5.7 b |

| 37.5BM | 132.8 ± 0.8 b | 5865.9 ± 55.8 bc | 5836.6 ± 35.4 b | 338.2 ± 1.7 ab | |

| 75BM | 141.6 ± 0.8 a | 6258.4 ± 37.3 a | 6131.1 ± 78.3 a | 368.0 ± 16.4 a | |

| 150BM | 140.9 ± 1.8 a | 6078.0 ± 35.8 ab | 6057.7 ± 30.2 ab | 348.2 ± 6.5 ab | |

| 300BM | 141.7 ± 2.5 a | 6190.8 ± 23.9 a | 6155.6 ± 80.7 a | 357.8 ± 6.3 a | |

| 2018 | CK | 125.5 ± 0.4 b | 4379.8 ± 15.0 c | 5119.3 ± 38.4 b | 517.1 ± 3.3 b |

| BM1 | 136.6 ± 4.4 a | 6145.8 ± 196.5 a | 5367.9 ± 36.7 a | 542.7 ± 7.5 a | |

| BM2 | 130.0 ± 1.0 ab | 5341.4 ± 42.4 b | 5231.3 ± 21.4 ab | 519.8 ± 4.4 ab | |

| BM1 + BM2 | 128.6 ± 1.4 ab | 5425.0 ± 57.1 b | 5188.9 ± 93.1 ab | 522.1 ± 6.1 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Di, H.J.; Ma, L.; Liu, W.; Li, B. Priestia megaterium Inoculation Enhances the Stability of the Soil Bacterial Network and Promotes Cucumber Growth in a Newly Established Greenhouse. Agriculture 2026, 16, 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030361

Zhao Y, Zhang M, Yang W, Wang X, Yang Y, Di HJ, Ma L, Liu W, Li B. Priestia megaterium Inoculation Enhances the Stability of the Soil Bacterial Network and Promotes Cucumber Growth in a Newly Established Greenhouse. Agriculture. 2026; 16(3):361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030361

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yingnan, Minshuo Zhang, Wei Yang, Xiaomin Wang, Yang Yang, Hong Jie Di, Li Ma, Wenju Liu, and Bowen Li. 2026. "Priestia megaterium Inoculation Enhances the Stability of the Soil Bacterial Network and Promotes Cucumber Growth in a Newly Established Greenhouse" Agriculture 16, no. 3: 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030361

APA StyleZhao, Y., Zhang, M., Yang, W., Wang, X., Yang, Y., Di, H. J., Ma, L., Liu, W., & Li, B. (2026). Priestia megaterium Inoculation Enhances the Stability of the Soil Bacterial Network and Promotes Cucumber Growth in a Newly Established Greenhouse. Agriculture, 16(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030361