1. Introduction

Tea quality depends largely on the levels of amino acids (AA) and tea polyphenols (TP), which shape flavor and health benefits [

1,

2]. AA, mainly L-theanine, enhance umami flavor. TP are dominated by catechins, adding astringency and color while offering strong antioxidant and health-promoting effects. Traditional laboratory techniques—known as wet methods (e.g., high-performance liquid chromatography and spectrophotometric assays)—offer accurate AA and TP measurements but are slow, destructive, and costly [

3,

4,

5]. Hyperspectral remote sensing has emerged in precision agriculture as a non-destructive way to monitor crop chemistry in situ [

6].

Most spectral studies evaluate tea quality using dried or processed materials. Near-infrared or hyperspectral reflectance combined with Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) or similar chemometric models has been widely applied to quantify major quality components such as theanine, catechins, and polyphenols in tea powders, extracts, or processed leaves [

7,

8,

9,

10]. These studies established effective modeling frameworks and demonstrated the potential of spectral techniques for rapid and non-destructive assessment of tea quality. However, most experiments were conducted on low-moisture or homogenized matrices under laboratory conditions. Previous studies have shown that fractional-order derivatives can enhance weak biochemical absorption features in hyperspectral modelling of soils and plants [

11], and that band-pair indices such as NDSI have been applied in agricultural and tea-related biochemical estimation [

12].

Choosing fresh leaves as the object presents several challenges. First, AA and TP occur at low concentrations, so their spectral signals are weak [

13]. Second, high water content (65–80%) and the complex leaf matrix cause overlapping absorption bands near 1450 nm and 1950 nm. These bands can obscure the spectral features of chemical components [

14]. Third, interactions among compounds make it harder to isolate each component’s signature [

15]. Hydrogen bonding between TP and AA is one example of such interactions. To address these difficulties, researchers have applied various approaches. Radiative transfer models such as PROSPECT can simulate leaf optical properties for pigments and water but have rarely been used for tea leaves due to limited spectral information on AA and TP [

16]. Other methods, including PLSR, support vector machines (SVM), and neural networks, have mostly targeted processed tea products, with few efforts on fresh-leaf prediction [

17,

18]. Derivative transforms enhance weak spectral features, and wavelength-selection algorithms such as Principal component analysis-genetic algorithm (PCA-GA), successive projections algorithm (SPA), competitive adaptive reweighted sampling (CARS), and variable iterative space shrinkage approach (VISSA) reduce data redundancy [

19,

20]. Despite their usefulness, these models often require large datasets, extensive parameter tuning, and rely on imaging systems, which restrict their feasibility for in-field monitoring [

11].

In this study, we aimed to establish a rapid, non-destructive method for estimating AA and TP in fresh leaves using hyperspectral reflectance. Purified AA and TP powders and their water mixtures were analyzed to identify absorption features. Fractional-order differentiation was then applied to fresh-leaf spectra to enhance weak signals and examine the sensitivity of candidate wavelength regions. Based on these findings, two-band spectral indices were constructed and tested against a full-spectrum PLSR reference model. This approach provides a mechanistically guided framework that supports practical monitoring of leaf-level tea quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

For spectroscopic measurements of purified powders, L-theanine (Thea) was selected as a representative AA due to its predominance in tea leaves, accounting for over half of the total free amino acids [

20], and its availability.

Two types of samples were collected for analysis in this study. The first type comprised purified powders of Thea and TP, their binary mixture powders, and corresponding water mixtures. These samples were used to analyze the spectral features of these two quality indicators and to identify sensitive spectral bands. The second category included fresh tea leaf samples, for which field-collected leaf spectral data and laboratory-analyzed tea quality parameters were obtained. These samples served to validate the sensitive bands identified in the purified powder analysis and to construct spectral indices. Detailed sample information is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Preparation of Purified Tea Quality-Related Component Powder Samples and Spectral Acquisition

Thea powder (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; Lot No. A2129041) and TP purified powder (Shanghai Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; Lot No. S25HS195833) were obtained as commercially available dried samples. These materials were individually stored in screw-capped test tubes wrapped with aluminum foil to prevent light exposure. Prior to experimentation, the purified powders were homogenized using a ceramic mortar to prevent aggregation and ensure sample uniformity.

For the experimental procedures, polypropylene (PP) containers with lids approximately 3 cm in diameter were utilized. To prepare the purified dry powder samples, 2 g of the corresponding substance was directly weighed using an electronic balance (Zhejiang Lichen Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shaoxing, China). For binary mixed dry powder preparation, 1 g of each corresponding substance was weighed using an electronic balance and transferred into a PP container. The container was then capped and thoroughly shaken to ensure homogeneous mixing. For the preparation of the water-mixed samples, 2 g of dry powder was first weighed as the base material. Different volumes of purified water (e.g., 0.5 mL, 1 mL, and 2 mL) were then added using a syringe. The mixture was stirred with a glass rod until complete contact and uniform dispersion between the powder and water were achieved. After being stirred, the samples were allowed to stand for 5 min to ensure complete water penetration and thorough integration of water with the samples. Three independent replicates were prepared for each sample type.

The samples were placed in PP containers within a dark room maintained at an ambient temperature of 23 ± 1 °C and a relative humidity of 15 ± 2% due to fixed laboratory constraints. The humidity level is lower than standard conditions but remained stable throughout all measurements. Spectral measurements were conducted using an ASD FieldSpec 4 spectroradiometer (ASD Inc., Boulder, CO, USA) coupled with a contact probe attachment. The system was equipped with an integrated halogen lamp as the light source, and the optical probe was positioned in close contact with the sample surface to acquire spectra across the wavelength range of 350–2500 nm. For each sample, five replicate measurements were taken at 3 different positions, resulting in a total of 15 measurements per sample type. To ensure data reliability, outlier values were identified and excluded using the Grubbs test (α = 0.05) at a few representative wavelengths. The remaining spectral data were averaged to obtain the final reflectance spectrum for each sample.

2.3. Leaf Sample Collection and Spectral Measurement of Fresh Tea Leaves

The tea leaf samples were collected from the Shengzhou Tea Experimental Base of the Tea Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, located in Shengzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China (119°44′ E, 30°45′ N, altitude 63 m, flat terrain). The experimental area is located in a northern subtropical monsoon climate zone, which is characterized by mild temperatures, distinct seasons, abundant rainfall, and high humidity. The annual average temperature is 17.2 °C, with an annual precipitation of 1355.1 mm, an average relative humidity of 75.5%, an annual sunshine duration of 1696.1 h, and a frost-free period of 235 days. The tea plantation covers an area of 15.67 ha, with diverse tea plant varieties. The soil in this region is red soil derived from a basalt parent material, with a pH of approximately 4.0, deep soil layers, and rich nutrients, making it highly suitable for tea cultivation and yielding high-quality tea leaves. These climatic and soil characteristics make the site representative of major high-quality tea-producing regions in China. For this experiment, 53 tea plant varieties were selected (two samples were collected for each variety in general. for a few varieties showing less healthy leaves, only one representative sample was taken), including Zhongcha 108, Zhenong 139, Xin’an 4, Zhenong 21, Zhenong 113, Xicha 8, and Longqu 1, whose ages ranged from 10 to 15 years.

Fresh leaf samples were collected on 14 May 2023 during the spring tea season. This period is widely regarded as the optimal harvest time for high-quality tea leaves in the study region. The date aligns with the mid-spring developmental stage. At this stage, AA and TP concentrations in mature leaves have reached a relatively stable level after the early flush but before summer heat stress begins. Meteorological records indicate clear weather on 14 May, with air temperatures ranging from 18 to 22 °C. These conditions minimized short-term impacts of rainfall or drought on leaf water content and spectral reflectance. An additional 40 independent set of fresh leaf samples was collected on 9 August 2023 during the summer flush to evaluate the temporal robustness of the proposed indices. All spectral calibration and parameter tuning, including FOD order selection, wavelength pairing, and PLSR components, were performed on the May dataset using 5-fold cross-validation. The August samples were not involved in model development and were used solely for external validation.

We sampled the top and bottom leaves from each branch to fit the ASD leaf clip, ensuring full probe contact and avoiding shadows. Moreover, mature leaves still contain significant levels of quality-related compounds such as AA and TP, and are widely used in mid- to low-grade tea production, functional tea processing, and quality monitoring at the canopy or field scale. Evaluating the spectral characteristics of such leaves thus has both agronomic relevance and practical implications for scalable, non-destructive quality assessment. Approximately 200 g of leaves was collected per sample, totaling 102 samples for subsequent analysis.

The collected samples were immediately transported to the laboratory for spectral measurements. Spectral measurements were conducted using an ASD FieldSpec 4 spectroradiometer equipped with a leaf clip attachment which provides a fixed illumination and round geometry, reducing the impact of the environment and observation geometry on the spectral measurement results. The spectral range covered 350–2500 nm. The spectral sampling intervals were 1.4 nm in the 350–1000 nm range and 1.8 nm in the 1000–2500 nm range. A halogen lamp with a color temperature of 2900–3100 K was used as the light source. Both the instrument and the light source were preheated for 1.5 h before the measurements. For each tea sample, reflectance spectra were measured at five positions on each of ten fresh leaves, with three replicates per location. After the outliers were removed, the average spectral data were calculated and used as the final spectrum for each sample.

2.4. Chemical Analysis

The collected leaf samples were subjected to enzyme deactivation and drying processes before being transported to the laboratory for analysis. The samples were ground using a ball mill and extracted with ultrapure water for subsequent analysis. For AA content determination, the sample extracts were reacted with a specified concentration of ninhydrin solution and phosphate buffer. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer for quantitative analysis. Similarly, the TP content was determined by treating the sample extracts with a standardized ferric tartrate solution, followed by spectrophotometric measurement at 540 nm. To ensure data reliability, each sample was analyzed in triplicate for both quality parameters. The quality control measures included the use of standard reference materials and routine calibration of the spectrophotometer. The analytical procedures follow GB/T 8314-2013 for AA and GB/T 8313-2018 and ISO 14502-1:2005 for TP [

21,

22,

23].

2.5. Spectra Data Preprocessing

All reflectance spectra were processed with a Savitzky-Golay (SG) smoothing filter [

24] first. SG uses local polynomial regression within a moving window, which suppresses high-frequency sensor and surface-texture noise while preserving the position and width of genuine absorption features—properties that are critical because differentiation can strongly amplify noise. A single SG configuration was applied consistently to both dry-powder and fresh-leaf datasets to ensure comparable preprocessing across samples. The SG filter parameters were optimized with a 7-point window size and second-order polynomial fitting to achieve an optimal balance between noise reduction and preservation of critical spectral features. The SG-smoothed spectra then served as the input for subsequent 1.0-order and fractional-order differentiation analyses.

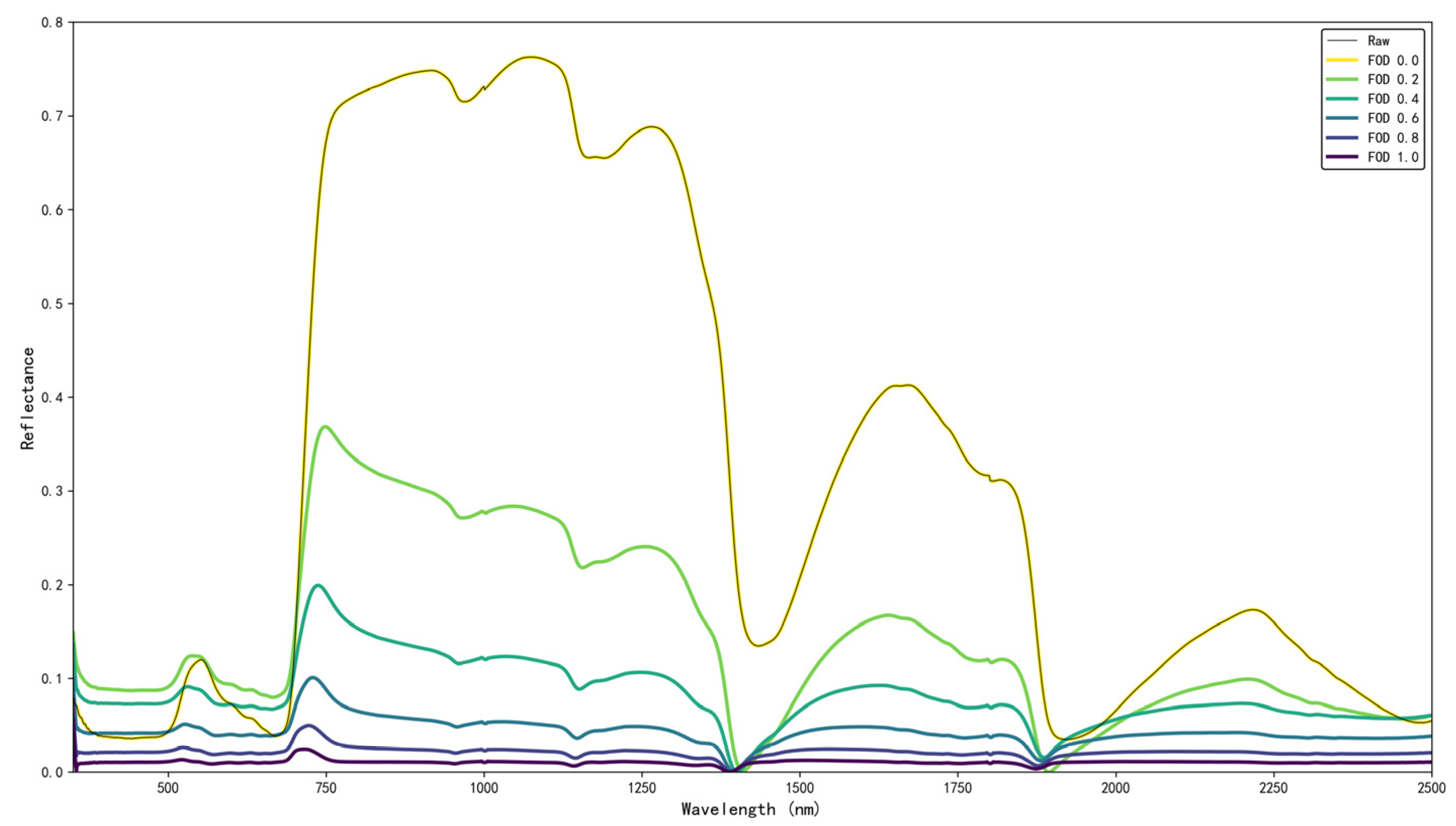

Then the reflectance data was processed by differentiation. Traditional integer-order differentiation can enhance the strength of weak signals; however, it also amplifies noise, which may negatively affect the accuracy of the model [

11,

25]. Schmitt pioneered the application of fractional-order differentiation theory to spectral analysis and demonstrated its advantages over traditional integer-order methods [

26]. In this study, both 1.0-order and fractional-order differentiation (FOD) methods were employed to enhance weak spectral signals associated with tea quality-related components. Considering the noise amplification effect inherent in differentiation operations, we evaluated FOD orders from 0.0 to 1.0 (step 0.1). In this study, FOD 0.0 denotes the non-differentiated reflectance spectrum (i.e., no derivative applied), which serves as a baseline reference. 1.0-order FOD is mathematically identical to the classical first derivative, so no separate subsection is provided for the integer case.

The FOD method extends traditional integer-order differentiation to non-integer orders, achieving a better balance between signal detail enhancement and noise suppression [

27]. This approach enhances subtle spectral features and improves the robustness of subsequent quantitative modeling.

The mathematical formulation for FOD is based on the Grünwald-Letnikov definition [

28]. For a reflectance spectrum

the fractional-order derivative of order

can be expressed as:

where

represents the sampling step size and

v denotes the fractional order of differentiation, which can take non-integer values. The term

refers to the generalized binomial coefficient [

29]. The formula applied to actual discrete spectra is:

where

. When the FOD method was applied to the smoothed spectra, various differentiation orders were tested by increasing

from 0.1 to 1.0 in steps of 0.1 to investigate the sensitivity of the spectral features of the leaf quality-related components to the fractional order. The FOD method was implemented in Python 3.11.5, utilizing a custom-developed program to numerically compute the summation based on the Grünwald-Letnikov formula. For numerical implementation, the Grünwald-Letnikov series was truncated to a finite window (k = 0 to K), with K = 11. Edge effects were handled by computing derivatives only where the full truncation window was available; wavelengths affected by incomplete windows were excluded from subsequent analysis.

To address the variability in interference factors during sample measurements, different spectral preprocessing strategies were adopted in this study: for dry powder samples with minimal interference, the original spectra and 1.0-order derivative spectra were selected to enhance the signal; for leaf samples, multi-order fractional differentiation techniques were applied to achieve an effective balance between the signal and noise.

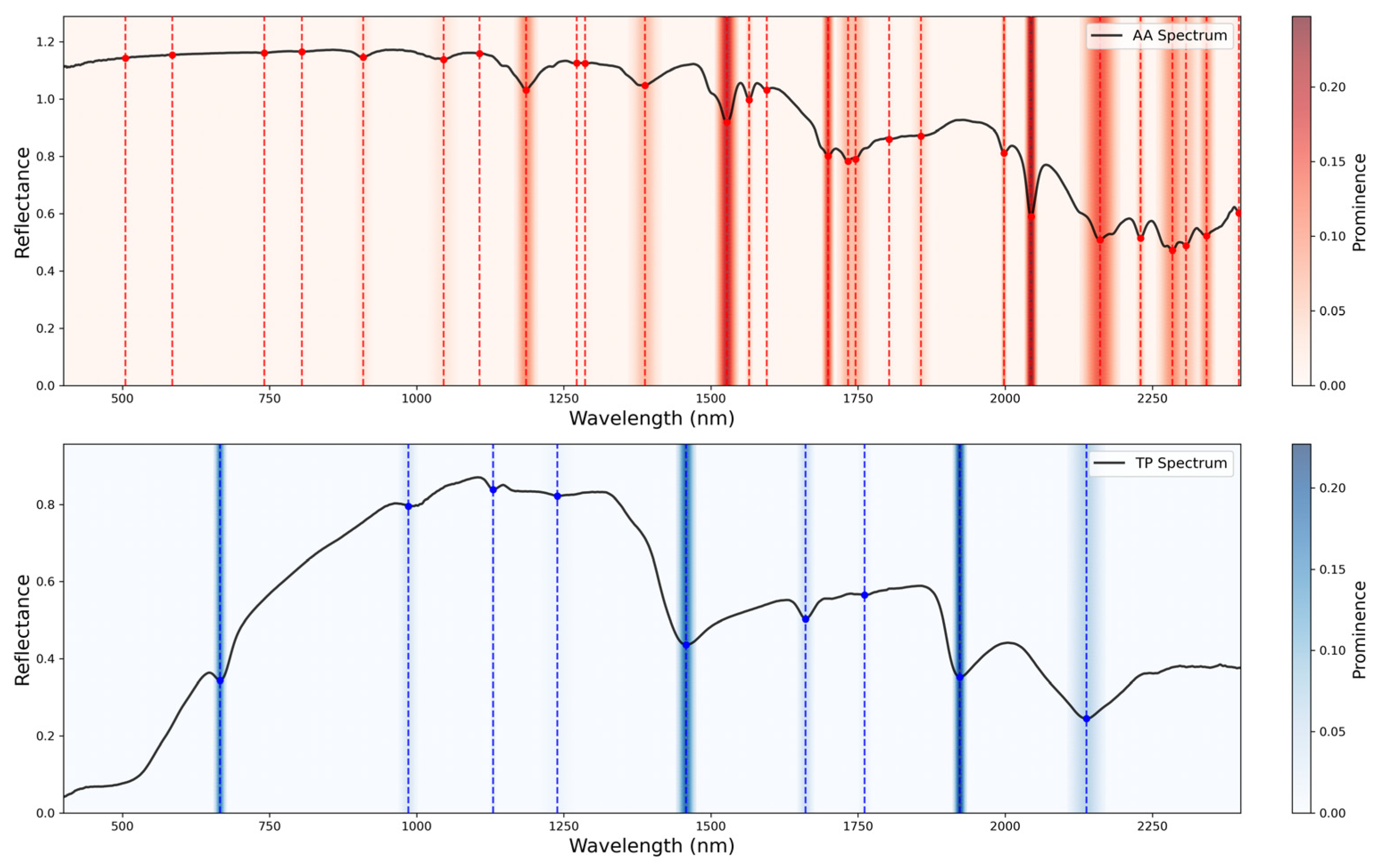

Figure 1 illustrates the SG-smoothed and FOD-transformed spectra used in subsequent analyses.

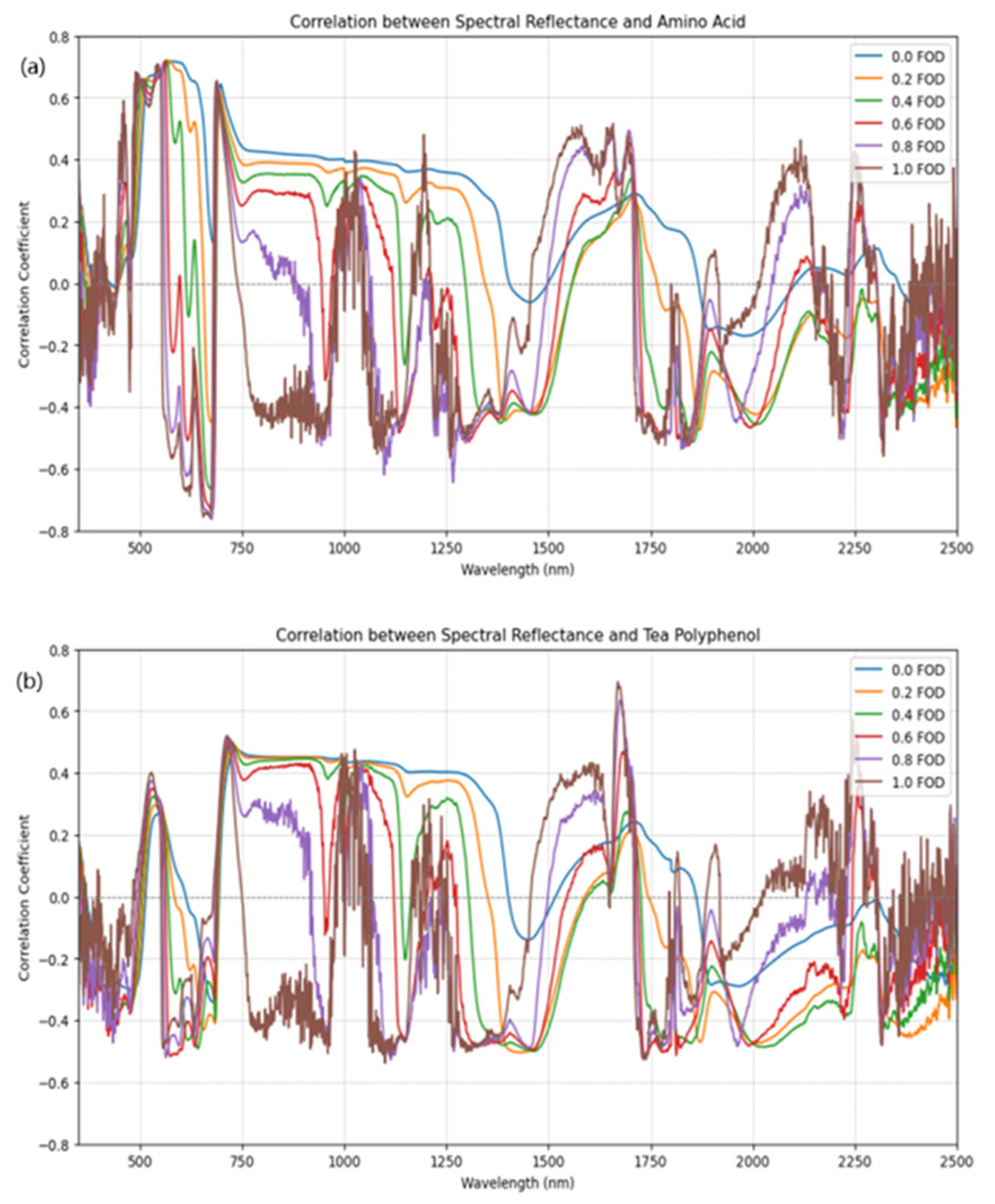

To investigate the enhancement effect of FOD on spectral characteristics of quality components in fresh tea leaves, a band-by-band correlation analysis was conducted based on the measured AA and TP content and their corresponding FOD spectral data. This analysis aimed to evaluate the sensitivity of spectral bands and FOD orders to these quality components. The set of FOD orders (0.0–1.0, step 0.1) was used to examine how spectral sensitivity to AA and TP changes with derivative order, and to avoid orders that introduce excessive noise.

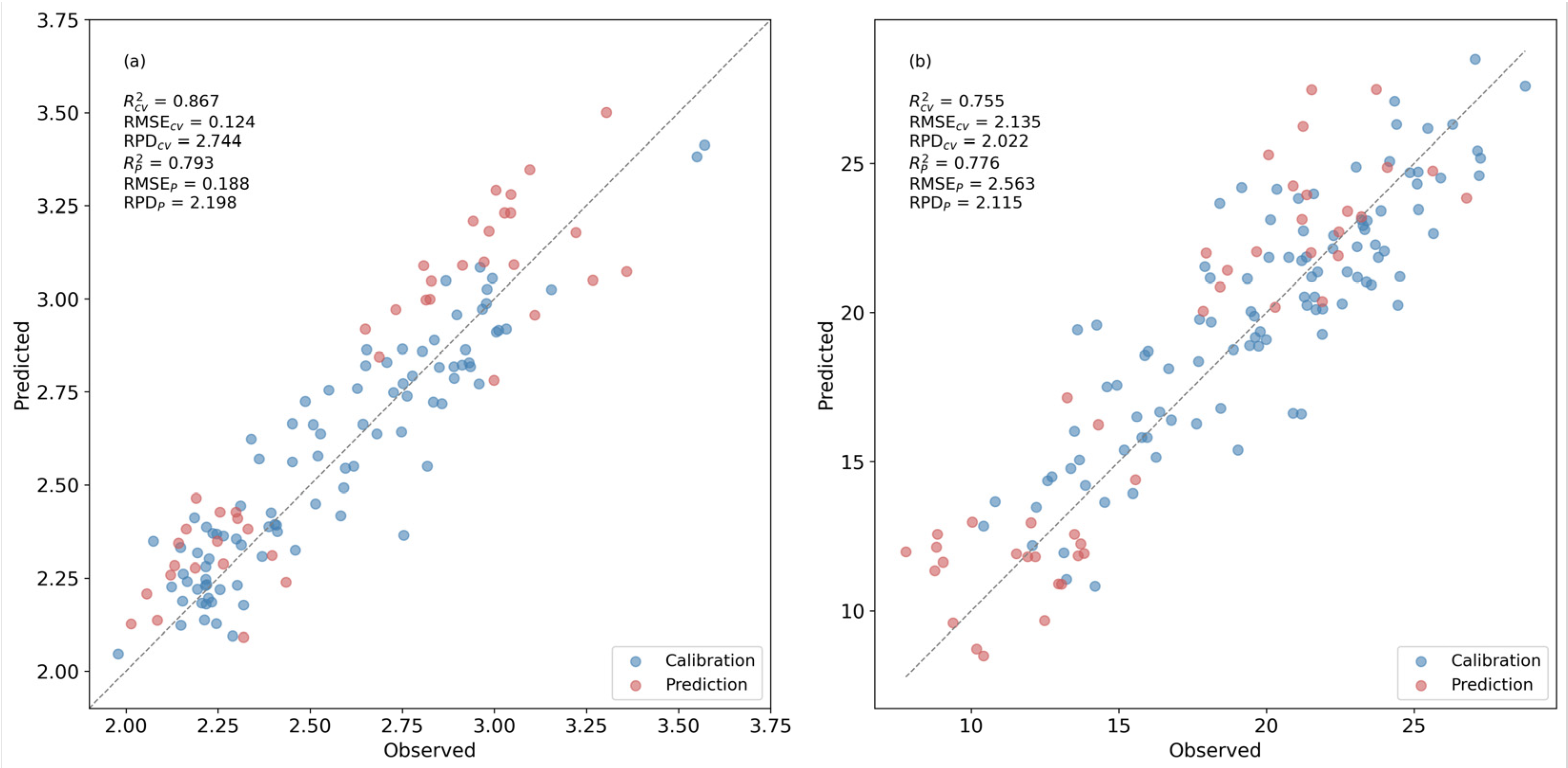

2.6. Full-Spectrum FOD-PLSR Modelling

PLSR models were constructed to provide a full-spectrum reference for AA and TP estimation. For each constituent, the reflectance spectra of the samples were first transformed by the optimal FOD order identified in the analysis. The resulting FOD spectra across the full spectral range were used as predictors, and laboratory-measured AA or TP contents were used as independent variables. The number of latent variables was selected by minimizing the cross-validated Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) within a 5-fold scheme on the calibration dataset. The number of latent variables was determined by scanning candidate values within a predefined upper limit and selecting the value that minimised RMSEcv in the 5-fold cross-validation on the May dataset.

Model performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R

2), RMSE and the ratio of performance to deviation (RPD). These metrics were calculated for both the internal 5-fold cross-validation on the May samples and the external prediction on the August samples. The full-spectrum PLSR models thus served as comparison.

In this expression,

is the coefficient of determination, SSE is the Sum of Squared, SST is Errors Total Sum of Squares,

is the measured constituent value for sample

,

is the corresponding predicted value,

is the mean of all measured values, and

is the number of samples. The numerator represents the sum of squared residuals, and the denominator represents the total sum of squares around the mean, so higher

values indicate better model performance.

In this expression above,

represents root mean square error, with the variable

,

,

,

, defined in Equation (2).

In this expression above, represents ratio of performance to deviation, with the variable , , , , defined in Equations (3) and (4).

In this research, R2, RMSE and RPD from five-fold cross-validation are denoted as R2cv, RMSEcv and RPDcv, while those from external prediction are denoted as R2p, RMSEp and RPDp.

2.7. Extraction of Absorption Bands and Construction of the NDSI

By analyzing reflectance spectra, the positions and characteristics of absorption bands in the spectra of materials can be inferred [

30,

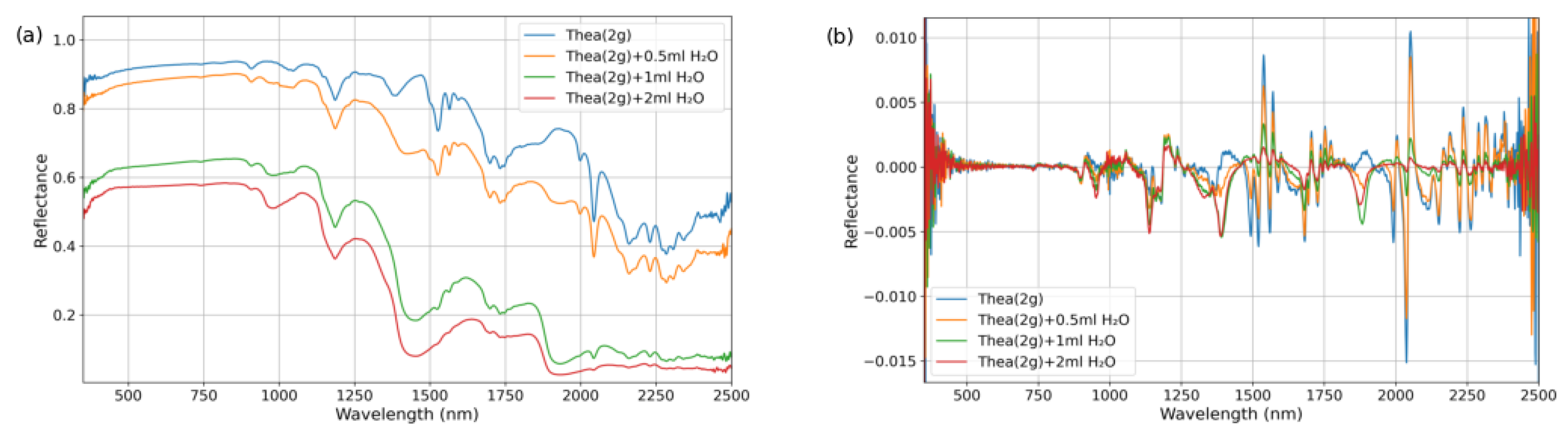

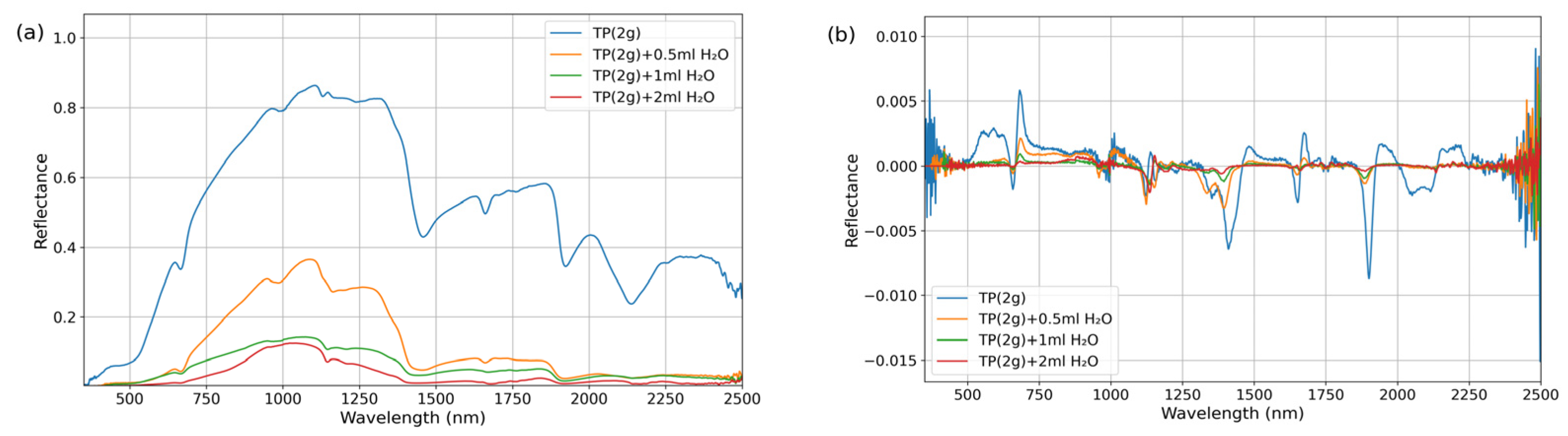

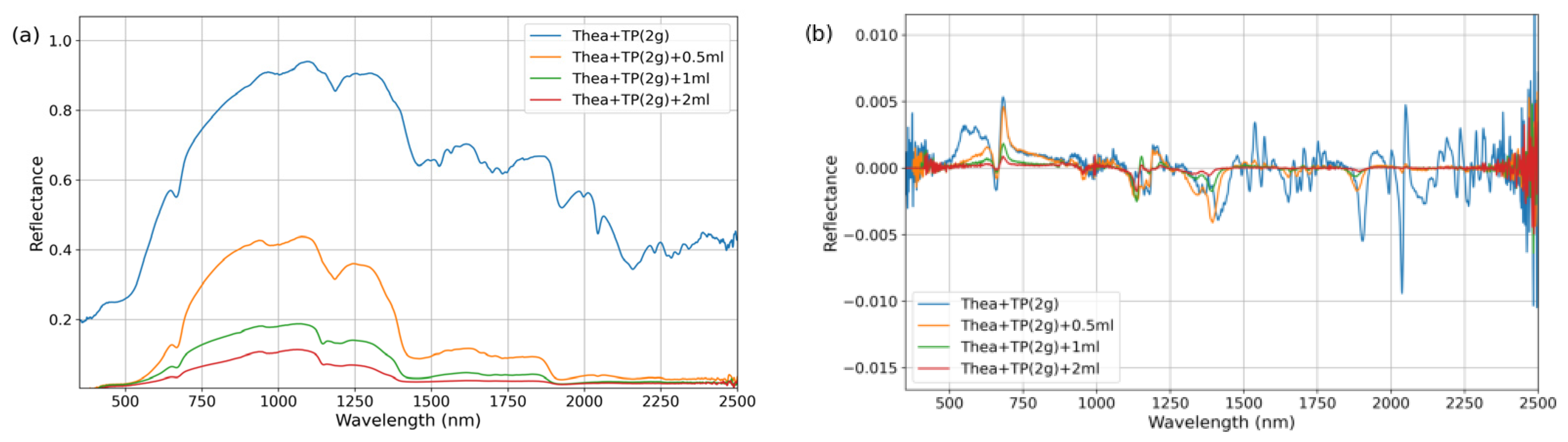

31]. A feature-driven strategy was employed to extract sensitive bands associated with tea quality-related components. Initially, the wavelength positions of absorption bands for quality-related components were preliminarily screened based on spectral data from dry powder and water-mixed samples. By subsequently integrating the preliminary sensitive bands with the quality-related content and differential spectral data of fresh leaf, the sensitive spectral bands for quality-related components of the fresh leaf were identified.

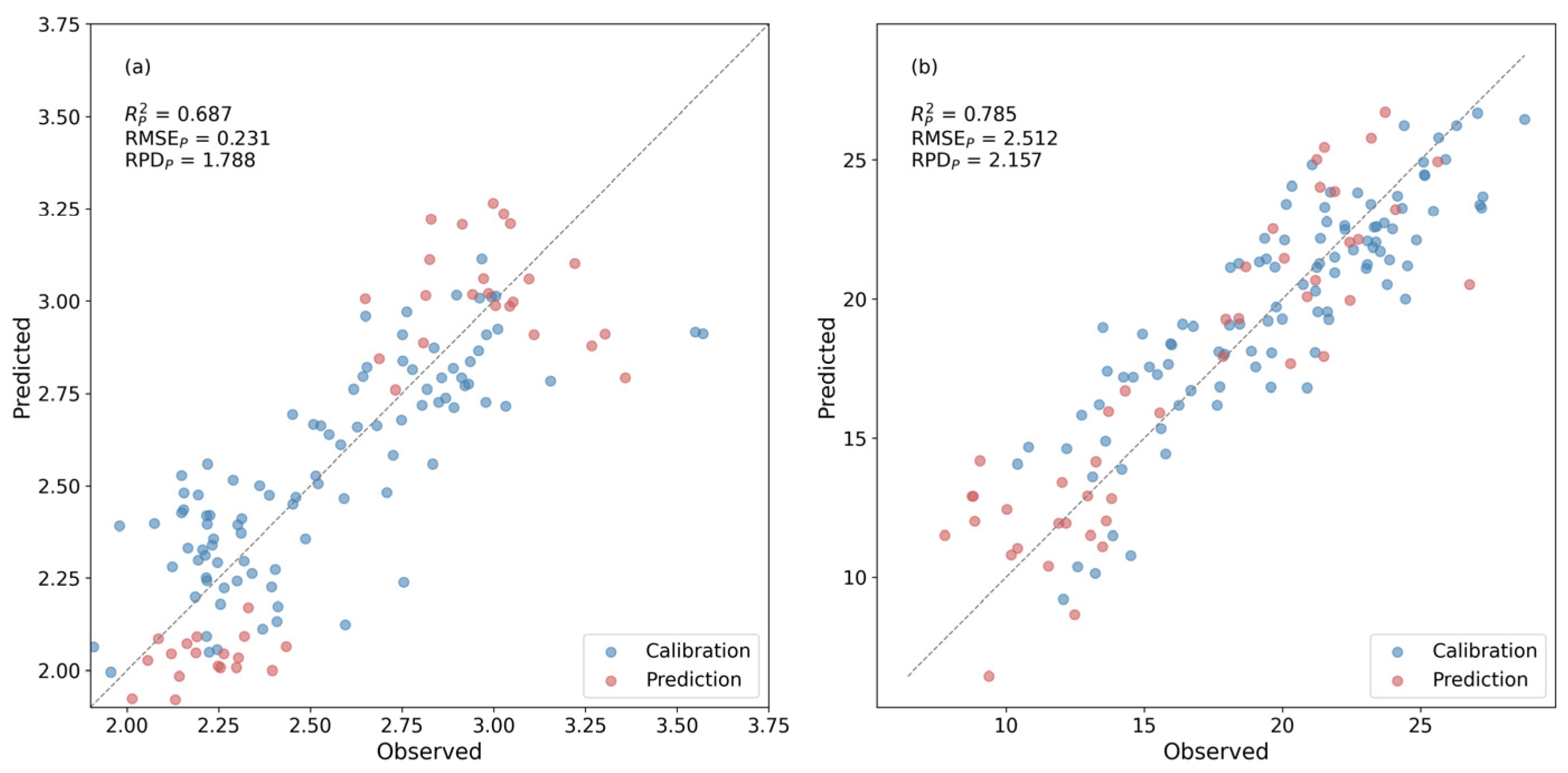

Absorption features typically represent the selective absorption of photons at specific wavelengths by target components (e.g., the C-H bond vibration absorption of TP at 1650 nm), which directly reflects the concentration information of the components. However, single absorption peaks are susceptible to interference from background noise (e.g., atmospheric scattering, instrument drift) and spectral overlap (e.g., the broad absorption of cellulose in the 1600–1800 nm range). By introducing non-sensitive signal or reflectance peak as reference bands and constructing normalized spectral indices using reflectance values at absorption peaks, systematic noise caused by factors such as lighting conditions and leaf surface structures (e.g., wax layers) can be mitigated. Simultaneously, the absorption signals of the target components are amplified. To quantify the spectral response characteristics of AA and TP in water-containing materials, spectral indices were constructed using the normalized difference index method based on sensitive bands. The calculation formula is as follows:

Among the variables and , one represents the absorption band, while the other represents the reference band.

The band selection strategy for the NDSI is as follows: (1) Sensitive band candidate set: Based on the original and 1.0-derivative spectra of the purified powders and FOD spectral sensitive wavelengths identified from fresh leaf spectra. (2) Reference band positioning: For each sensitive band, the reference band was selected by insensitive bands or absorption peaks. This placement reduces overlap from adjacent absorptions and improves index robustness to noise and illumination. (3) Iterative computation and validation: NDSI values are calculated for all candidate combinations, and the universality and stability of the band combinations are evaluated using data from dry powder and mixed samples.

In this study, wavelength combinations for NDSI construction were primarily selected based on their performance in univariate regression models, with the coefficient of determination (R2) used as the main criterion to evaluate predictive strength. The NDSI pairs with the highest R2 values for each biochemical trait were considered optimal. Additionally, FOD spectral preprocessing was applied, and the optimal order was selected to enhance spectral features and improve the performance. Combinations involving high-noise bands were excluded to ensure robustness.

To fully exploit the advantages of fractional-order differentiation, in addition to the original reflectance spectra, we applied fractional-order differentiation with the order ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 to balance the signal and noise. The optimal NDSI for each quality-related component was then selected and constructed by integrating the processed spectral data with corresponding quality-related content measurements.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that AA and TP in fresh tea leaves can be estimated from leaf reflectance by combining mechanistic band selection with fractional-order differentiation and two-band NDSI models. The approach links compound-level absorption features obtained from purified powders with leaf-scale spectra. In doing so, it provides an intermediate option between purely data-driven chemometric models and unconstrained vegetation indices.

The key absorption window around 1650–1700 nm, which was highlighted by the powder experiments and FOD-based correlations, proved to be informative for both AA and TP in hydrated leaves. The strong water absorptions near 1450 and 1940 nm are dominated by O-H overtone and combination bands, which can mask biochemical signals in hydrated leaves. In contrast, water absorption is comparatively weaker in the 1650–1700 nm window, allowing overlapping C-H/N-H/C=O-related combination features to contribute more to the reflectance variations. This region corresponds to overlapping overtones and combination bands of N-H, C-H, and C=O groups in tea metabolites and related plant compounds, and is less strongly dominated by liquid water absorption than the 1900–2000 nm range. Previous studies have also reported stable TP features near 1660 nm and around 2140–2142 nm in teas and related matrices, as well as the importance of water absorption near 1450 and 1940 nm when interpreting plant spectra [

7,

8,

9,

34]. The present results are consistent with this pattern and further support the view that indices anchored on the 1650–1700 nm flank are more robust under high leaf water content than those relying on broader bands in the 1900–2000 nm zone [

34]. For AA, the 1735/1626 nm index combines an AA-related feature region with a nearby reference flank, which can mitigate background and continuum variation. For TP, the 1673/1660 nm pair samples the shape of the absorption feature near 1660 nm, making the index sensitive to feature-depth variation within a comparatively water-tolerant window.

Compared with laboratory studies based on tea extracts, powders, or low-moisture processed products, the prediction accuracy obtained here is moderate, especially for TP. Many previous works achieved high coefficients of determination and low prediction errors for AA or TP using near-infrared or hyperspectral data under controlled conditions, often after homogenization or extraction [

2,

7,

12,

19]. In fresh leaves, however, AA and TP signals are diluted by water and confounded with overlapping absorption of cellulose, proteins, and other constituents, and the leaf mesophyll structure introduces additional scattering variability. The inclusion of more than fifty varieties and a separate summer validation set further exposes the models to such sources of variability, which partly explains the moderate, yet practically meaningful, accuracy levels obtained. The R

2 and RPD values observed here therefore reflect both the intrinsic difficulty of the target (low-concentration compounds in hydrated tissue) and the more realistic, field-oriented configuration of the measurements. The external validation RPD values (1.788 for AA and 2.157 for TP) indicate approximate quantitative capability. Therefore, the proposed indices are more suitable for screening, relative ranking, and trend monitoring across samples rather than replacing laboratory assays when strict grading thresholds are required. In applications where decision boundaries are narrow, confirmatory wet-chemistry analysis remains necessary.

The use of fractional-order derivatives was motivated by previous work showing that non-integer differentiation can enhance weak spectral features while moderating noise amplification compared with classical first derivatives. In this study, FOD was used both to sharpen compound-specific absorption features and to stabilize the correlation structure across wavelengths. The results suggest that mid-order FOD can improve sensitivity to AA- and TP-related bands in the 1650–1700 nm region without excessive noise, which agrees with earlier findings on soils and plant components where fractional derivatives improved quantitative modeling performance [

11,

27].

From a modeling perspective, the full-spectrum FOD-PLSR models provided solid comparison, with decent cross-validated and external R

2 for both AA and TP. However, they highly count on latent variables and tuning, which complicates transfer to new instruments or growing conditions. In contrast, the two-band NDSI models use only a small number of parameters and a single linear regression step, yet still achieve external prediction accuracies close to those of PLSR. This is important for practical tea quality monitoring, where simple, interpretable indices are more easily implemented on field spectrometers or less-channel sensors than high-dimensional chemometric models. Similar trade-offs between accuracy and simplicity have been noted in other tea and plant-spectroscopy applications that compare complex machine-learning models with more index-based approaches [

10,

12,

19,

35,

36].

AA and TP exhibited a weak but significant positive correlation in our dataset, indicating partial biochemical covariation. This covariation may arise from shared physiological drivers such as nitrogen status, leaf developmental stage, and general metabolic activity. Therefore, some degree of cross-sensitivity is possible, especially because the informative SWIR window is partially overlapping. However, the final indices use different wavelength pairs (AA: 1735/1626 nm; TP: 1673/1660 nm) and the sensitivity analysis highlighted distinct local maxima for AA and TP, suggesting that the indices capture compound-related variation beyond a single shared trend. We therefore interpret the indices as compact, mechanistically guided proxies, while acknowledging that broader validation and controlled experiments are needed to further confirm compound specificity.

Several limitations should be noted. The experiment was conducted at a single site and year, so model transfer to other regions or climate conditions might need to be verified. Tea biochemical composition can vary with soil, climate, elevation, cultivar, and management practices, so multi-site validation is needed to confirm whether these relationships are broadly applicable. Transferability between sensors may be affected by differences in spectral resolution, band centers and bandwidths, signal-to-noise ratio, and radiometric calibration, which can change the effective response of the selected AA and TP bands. Most commercial multispectral SWIR sensors provide broader bands and may not align exactly with 1626, 1660, 1673, and 1735 nm. A potential option is to resample the hyperspectral spectra to realistic multispectral bandpasses and re-optimise the wavelength pairs within available centres and bandwidths. If strict alignment is required, custom narrowband filters or handheld SWIR spectrometers would be needed, with higher hardware cost. The two-band design also cannot fully exploit all spectral information. Scalability to field conditions is constrained by variations in illumination and viewing geometry, background, and leaf water-status dynamics, so further validation under representative field acquisition protocols is recommended. Leaf water status is a key source of variability under field conditions. Although the selected 1650–1700 nm window is less dominated by water absorption than the 1900–2000 nm region, changes in leaf water content can still alter reflectance and may affect the robustness of the AA and TP indices. In the current dataset, leaf water content was not measured independently, so we could not quantify whether prediction errors covary with water status or seasonal moisture differences. This should be considered a key limitation for practical deployment and warrants targeted validation with concurrent moisture measurements. Finally, TP is intrinsically more difficult to predict than AA because its absorption overlaps more strongly with other biochemical and structural signals and with water-related variability [

34]; however, the FOD-NDSI index for TP achieved external

values comparable to, or slightly higher than, those for AA, suggesting that the selected window still captures TP-related variation effectively. The use of FOD and two-band indices in this study aligns with earlier efforts to enhance biochemical sensitivity in reflectance spectroscopy [

27,

36], and our contribution extends these strategies to AA and TP in fresh tea leaves.

Future work should extend testing across more regions, seasons, and variety groups, and explore light-weight refinements that remain mechanistically grounded. For example, carefully designed three-band or ratio-difference indices could capture additional aspects of the 1650–1700 nm feature while retaining a clear physical interpretation. Integrating the present band-level approach with advances in tea phenotyping and leaf-level spectroscopy may also support multi-scale applications that link leaf measurements to canopy or plantation monitoring [

10,

36]. In this way, FOD-informed NDSIs anchored in a chemically justified window could provide a practical basis for non-destructive, in situ assessment of AA and TP in fresh tea leaves. In addition, the experimental conditions (23 °C, 15% RH) differ from standard laboratory settings, so model transfer to other environments should be treated cautiously. Further testing under more varied temperature and humidity is recommended.

5. Conclusions

In this study, reflectance-based models were able to estimate AA and TP in fresh tea leaves with moderate accuracy and acceptable robustness between seasons. Pure-compound spectra were first used to identify a chemically meaningful window around 1660 nm, and this information was then transferred to leaf-level FOD spectra. Full-spectrum FOD-PLSR served as a comparison and reached quantitative accuracy on the spring calibration set and good performance on the summer validation set. Under the same calibration-validation scheme, the best NDSI indices (1735/1626 nm for AA, R2ₚ = 0.687, RPDₚ = 1.788; 1673/1660 nm for TP, R2ₚ = 0.785, RPDₚ = 2.157) achieved external R2 and RPD values close to those of the corresponding PLSR models (AA, R2ₚ = 0.793, RPDₚ = 2.198; TP, R2ₚ = 0.776, RPDₚ = 2.115), indicating that much of the useful information for these traits is concentrated in this narrow SWIR region. Notably, the TP index provided external R2 values comparable to, or slightly higher than, those of the AA index, even though TP is generally more difficult to predict in fresh leaves.

The proposed indices are simple and interpretable, relying on only two bands and a single linear regression, which suggests potential suitability for implementation on portable spectrometers in field-based tea quality monitoring. However, the present models were developed at a single site and year, and the two-band design cannot exploit all spectral information. Further testing across additional regions, seasons and cultivars are encouraged.