Design and Experimentation of High-Throughput Granular Fertilizer Detection and Real-Time Precision Regulation System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

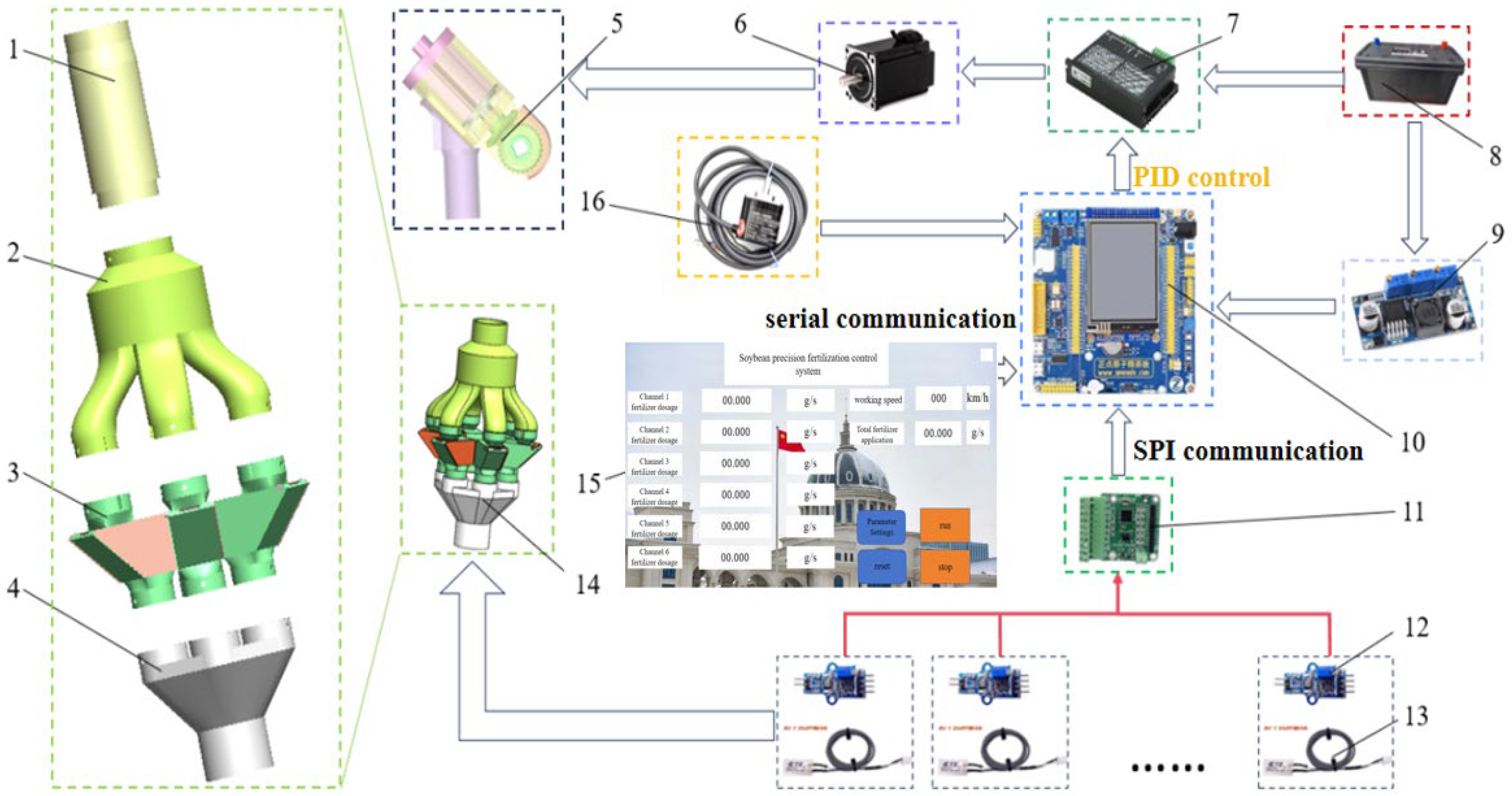

2.1. Overall Structural Design and Working Principle

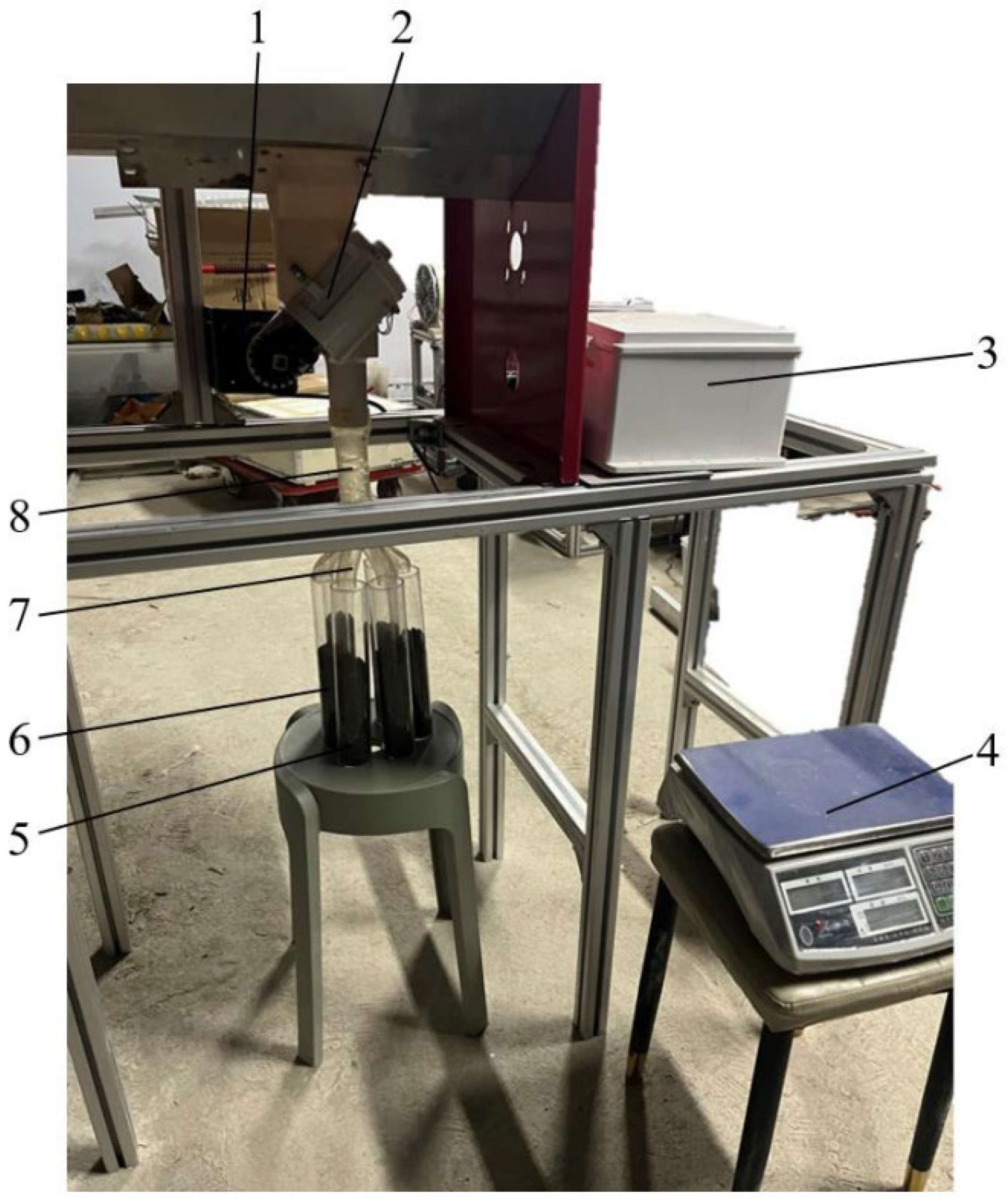

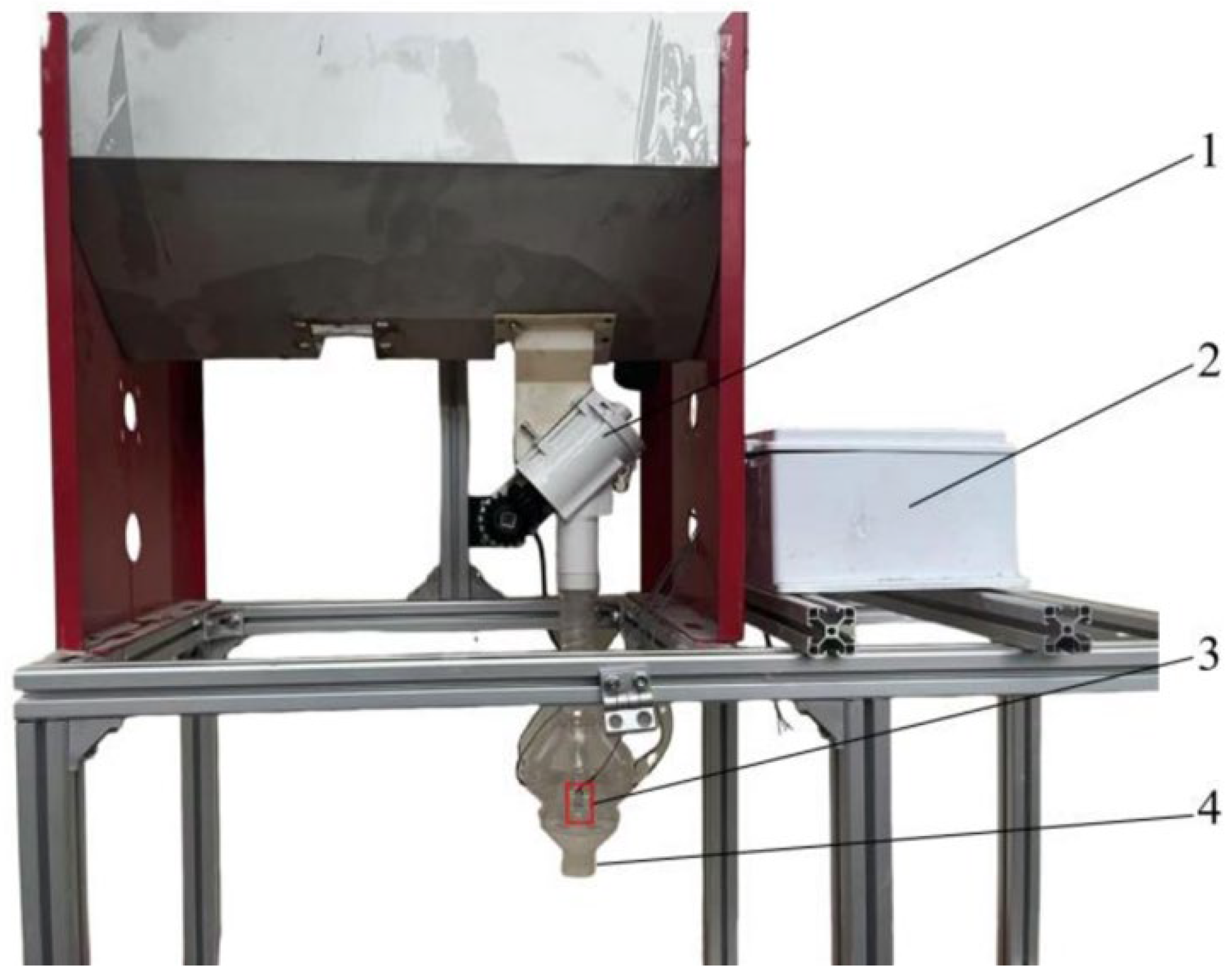

2.1.1. Overall Structure

2.1.2. Working Principle

2.2. Key Component Design

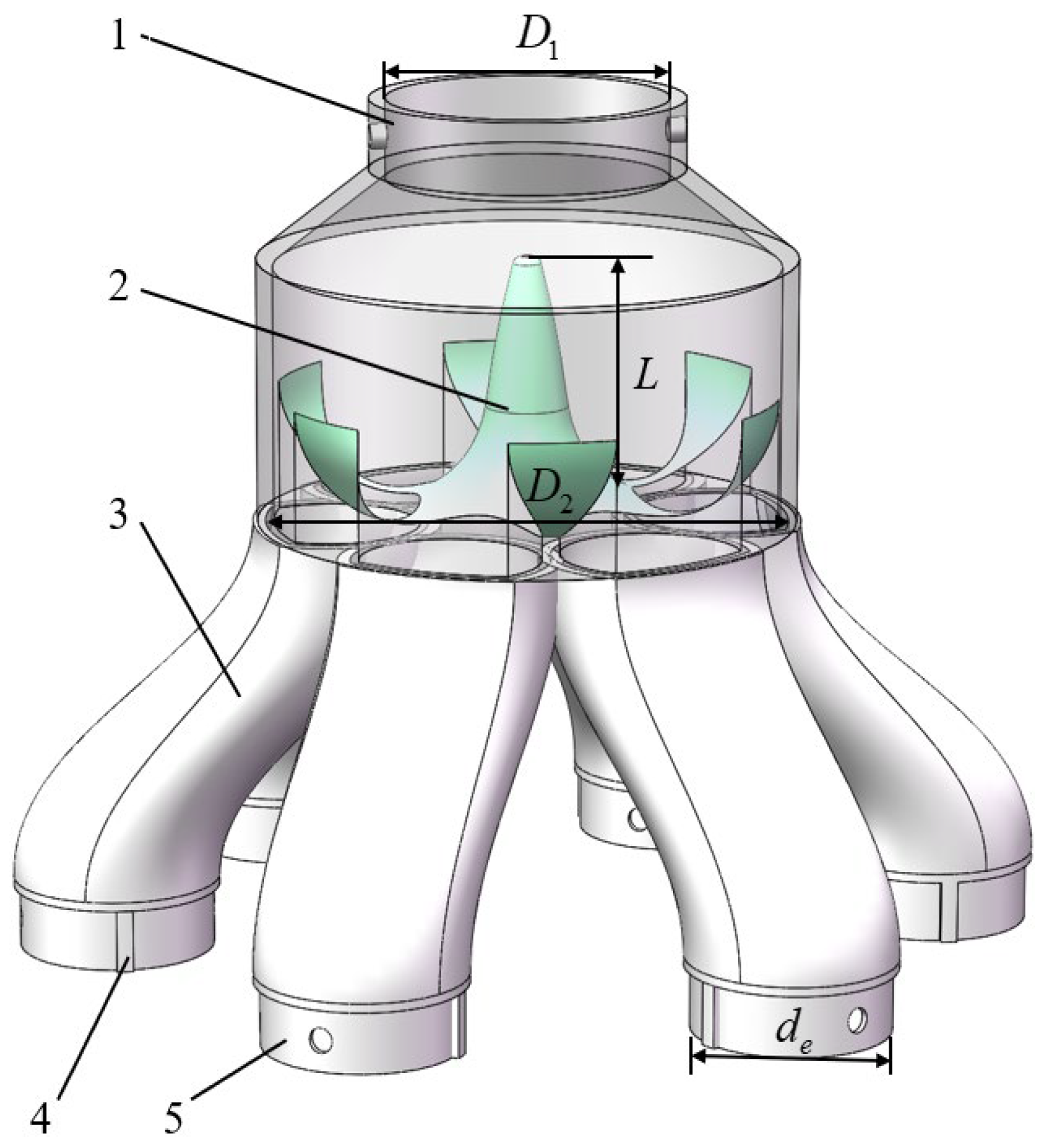

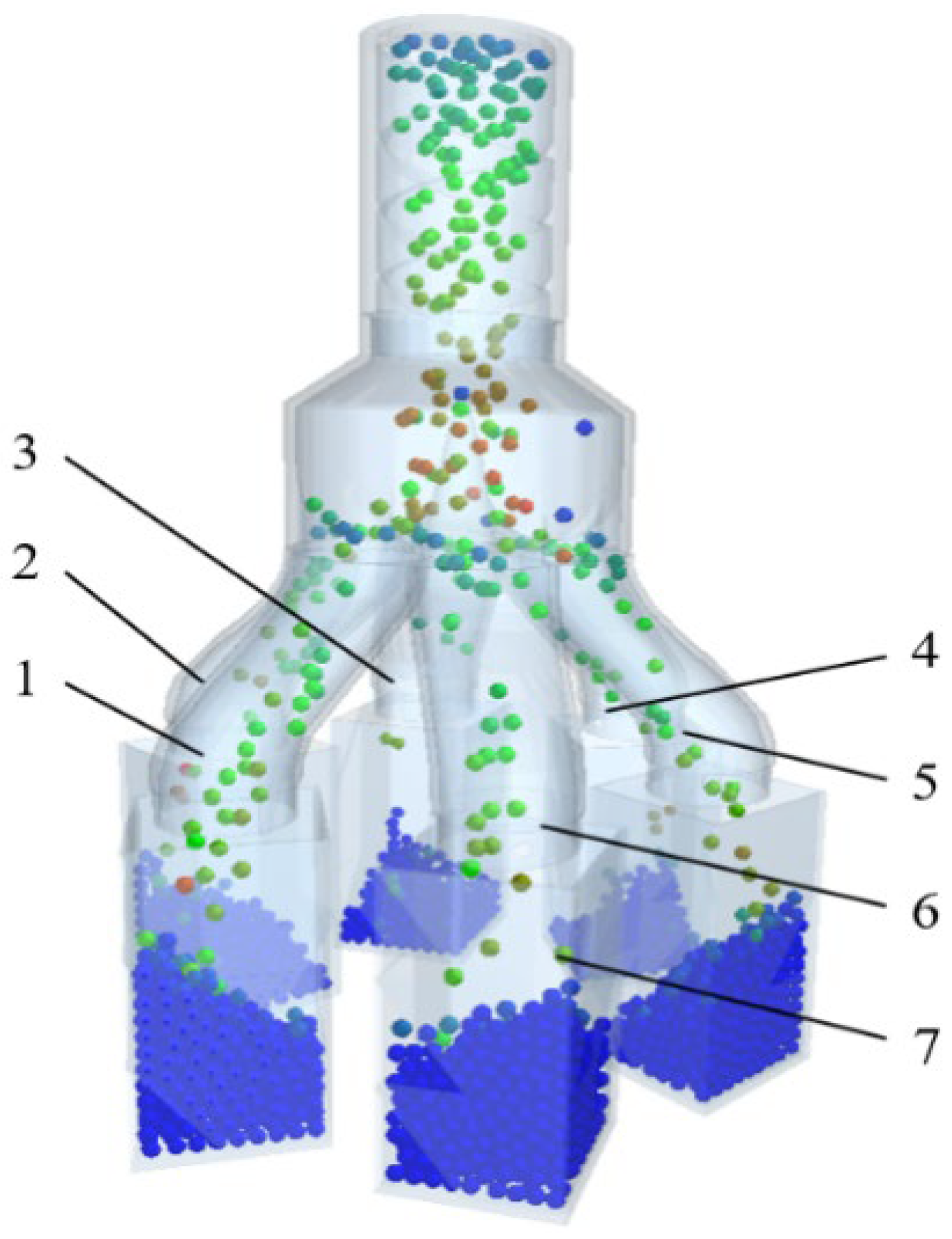

2.2.1. Uniform Fertilizer Distribution Device

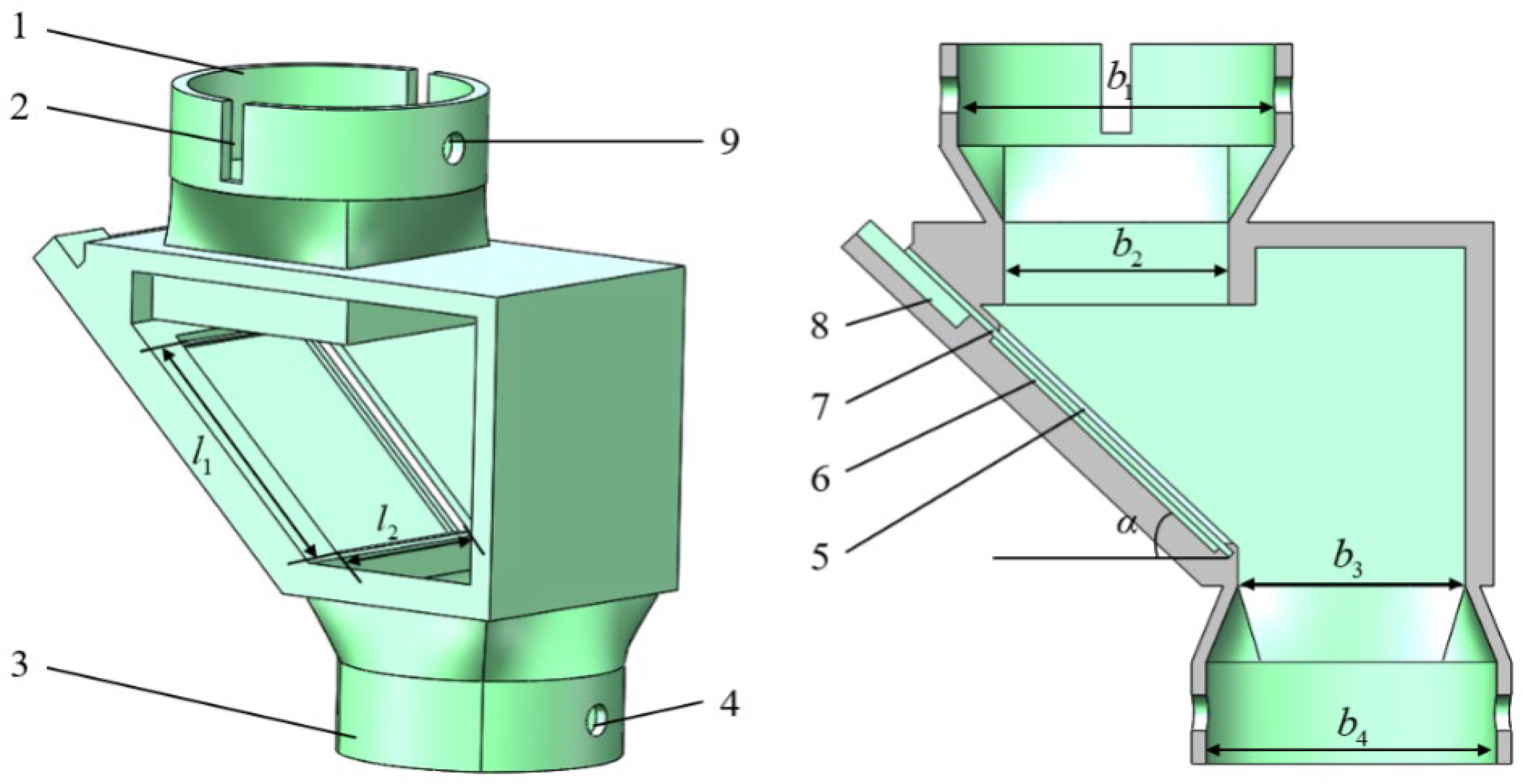

2.2.2. Design of Diversion Structure

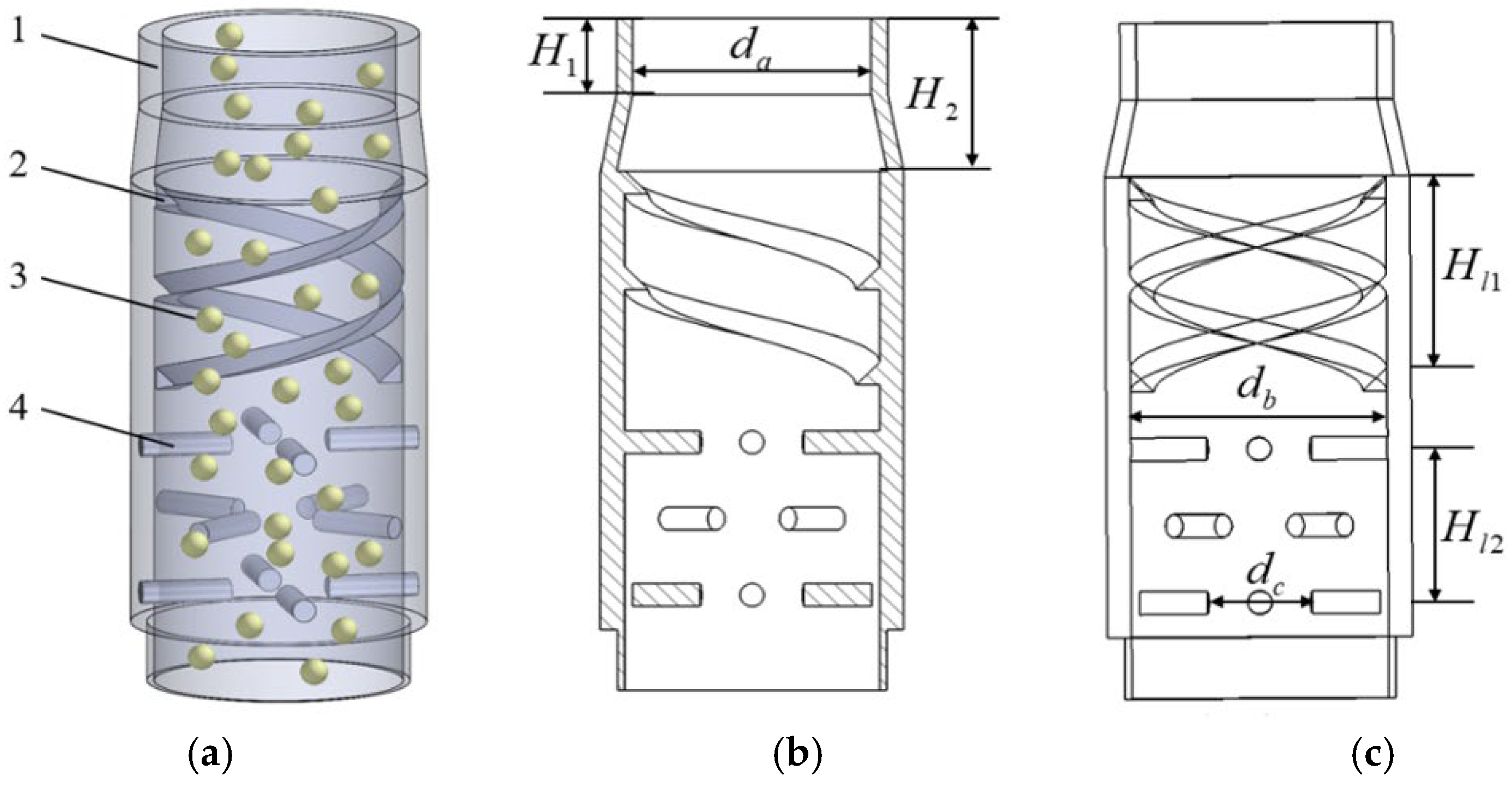

2.2.3. Sensing Device

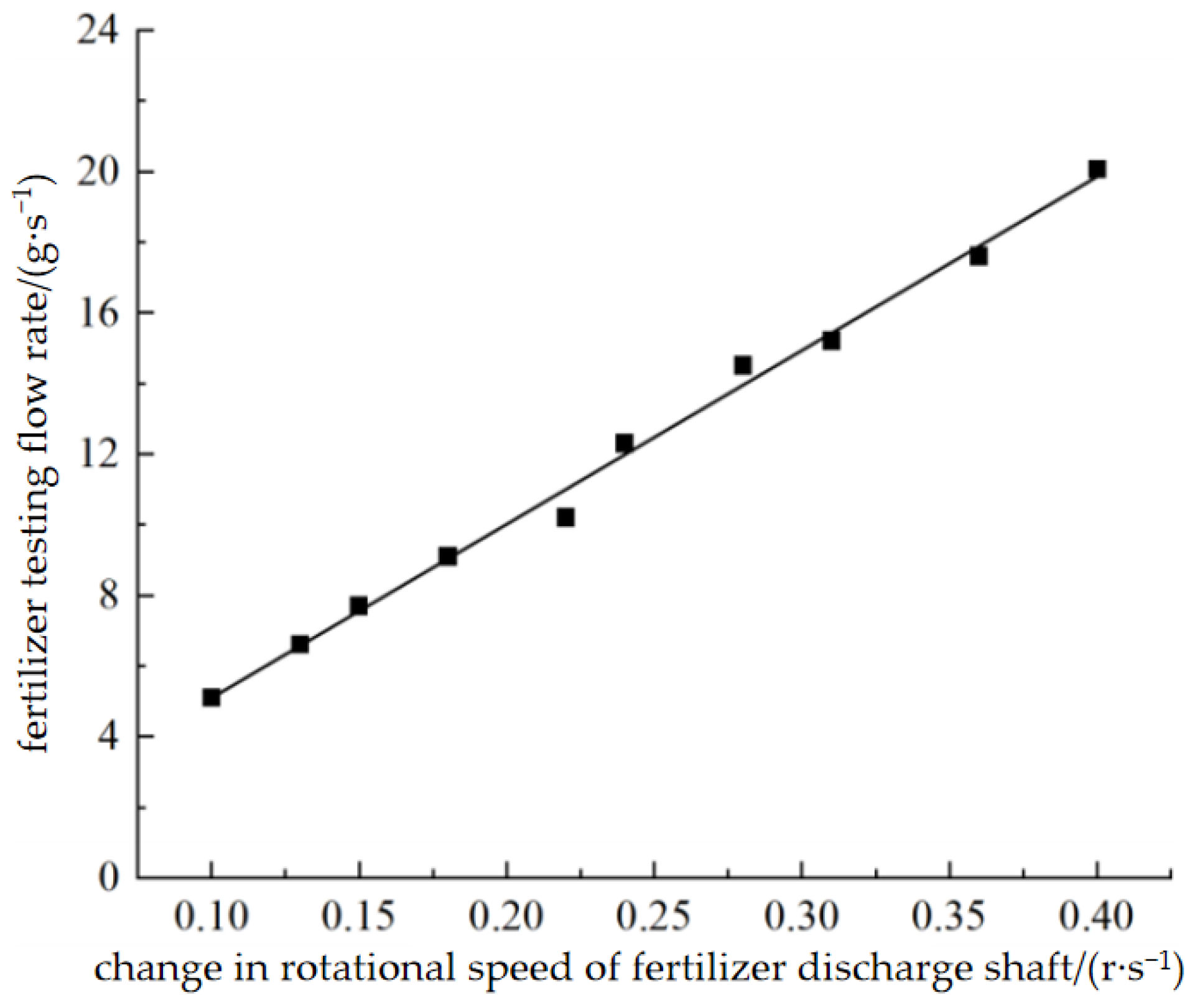

2.2.4. Flow Detection Calibration Test

2.2.5. Testing Process

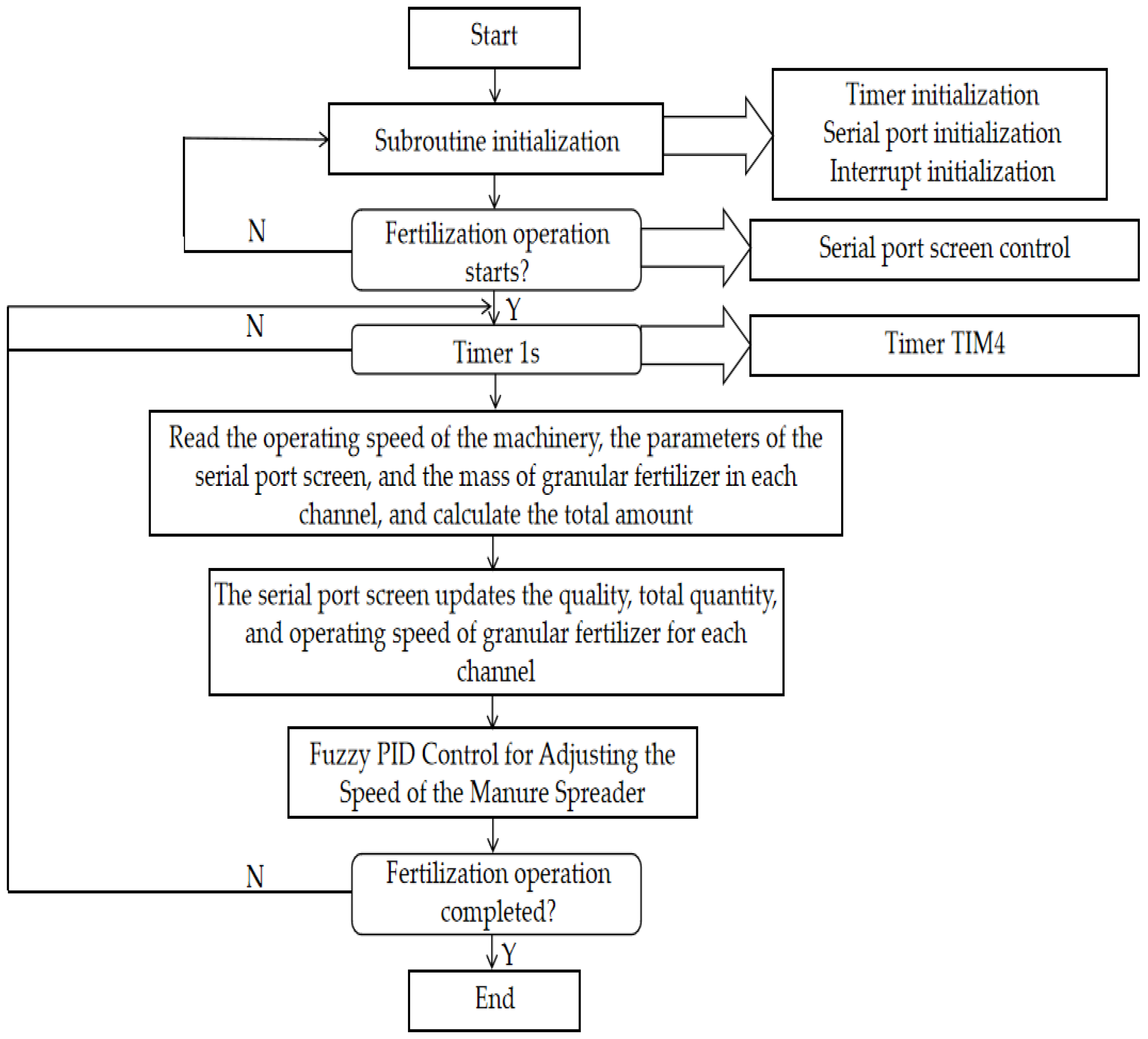

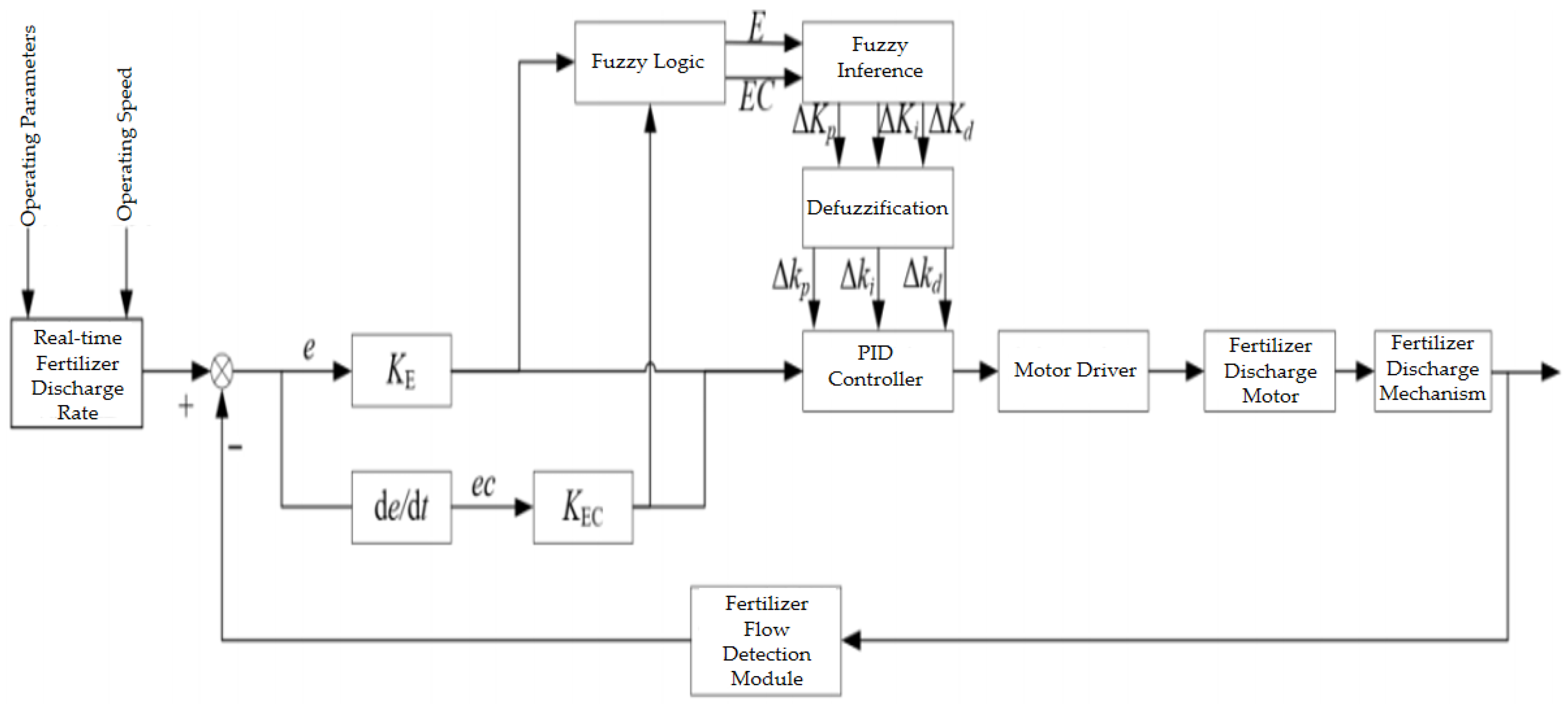

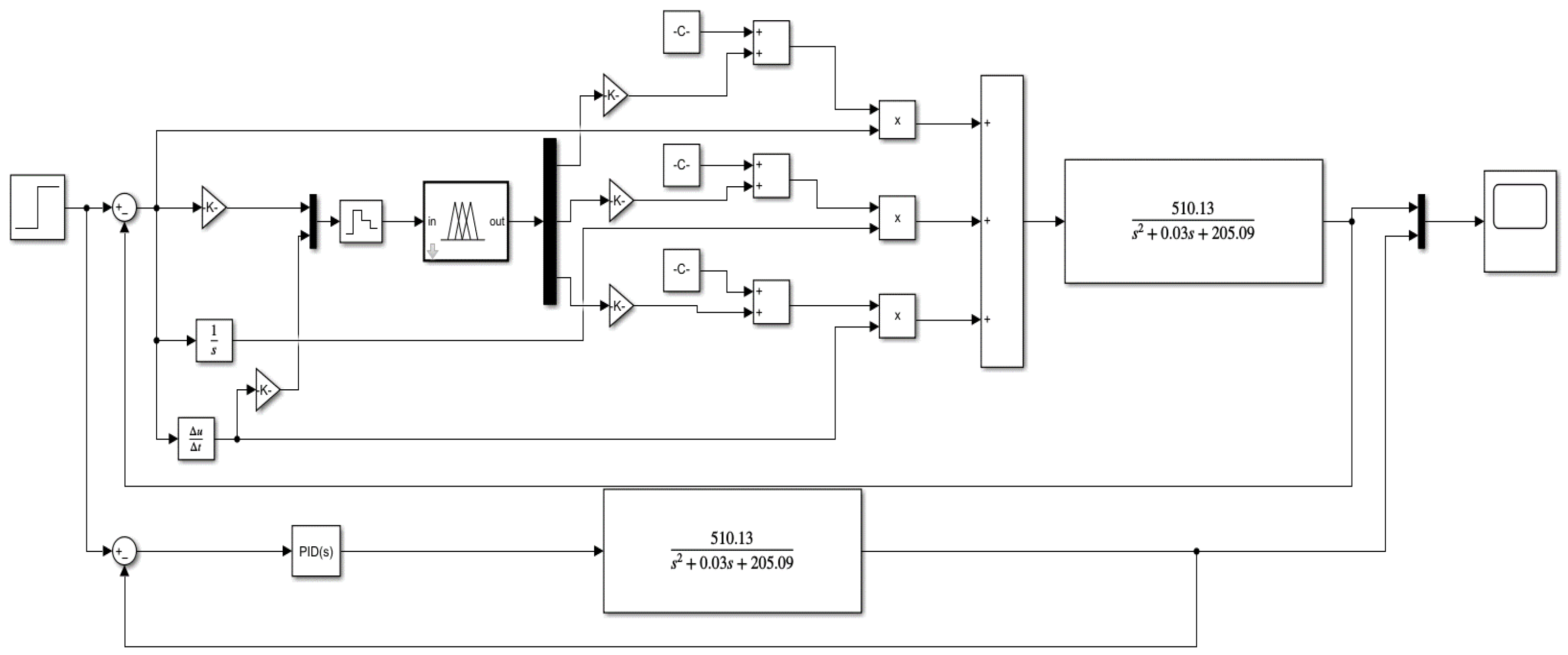

2.3. Fuzzy PID Control

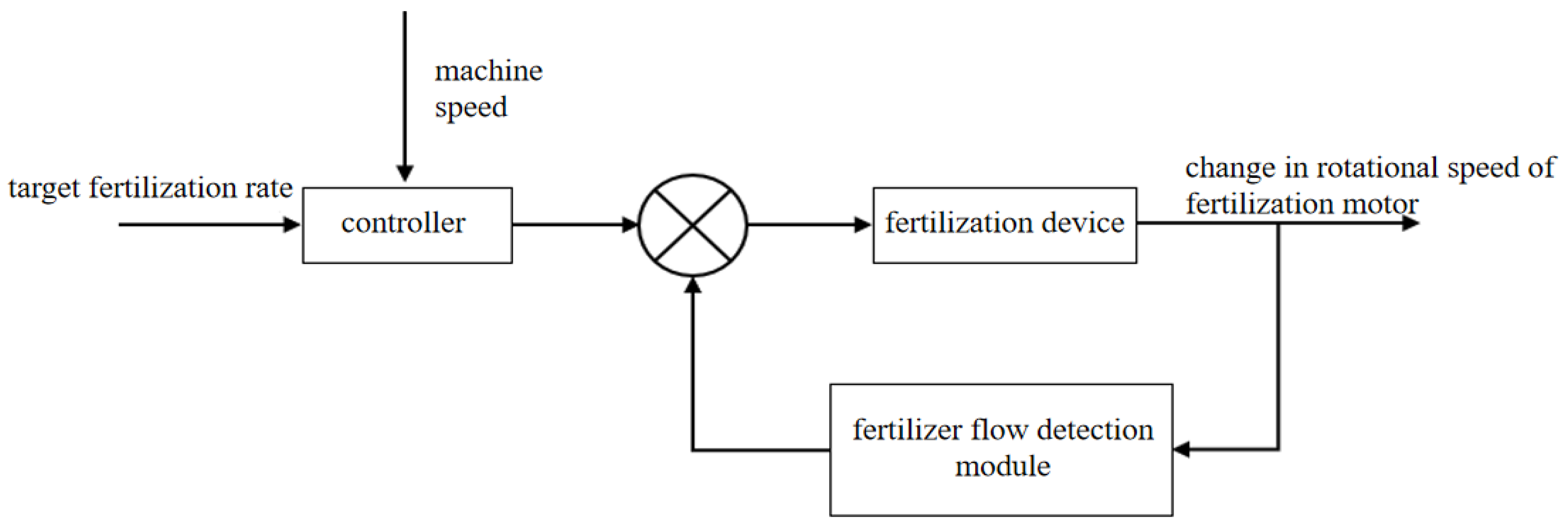

2.3.1. Modeling of Precision Fertilization Control System

2.3.2. Fuzzy Controller Design

- When the system exhibits significant deviation, prioritize the application of a reinforced proportional-derivative control strategy. At this stage, increase the proportional gain ∆Kp to accelerate error elimination while reducing the derivative gain ∆Kd to prevent overshoot. Typically, set the integral gain ∆Ki to zero to avoid integral saturation. This configuration balances response speed and stability requirements.

- When the deviation converges to a smaller range, the proportional gain ∆Kp and integral gain ∆Ki should be increased simultaneously. This strategy maintains the system’s ability to adjust for deviations while enhancing steady-state accuracy through integral action. Care must be taken to avoid oscillations or reduced stability caused by excessively large parameters.

- If the deviation and its rate of change share the same sign, particularly when approaching the target value, the proportional control component and integral action exhibit an inverse relationship. By suppressing the integral accumulation effect, overshoot and accompanying periodic oscillations can be effectively avoided, thereby achieving a smooth convergence process.

- When the absolute value of deviation change rate is large, ∆Kp should be appropriately reduced to minimize sudden increases in control output, while simultaneously increasing ∆Ki to enhance cumulative compensation for dynamic error. This balances system disturbance rejection with control robustness.

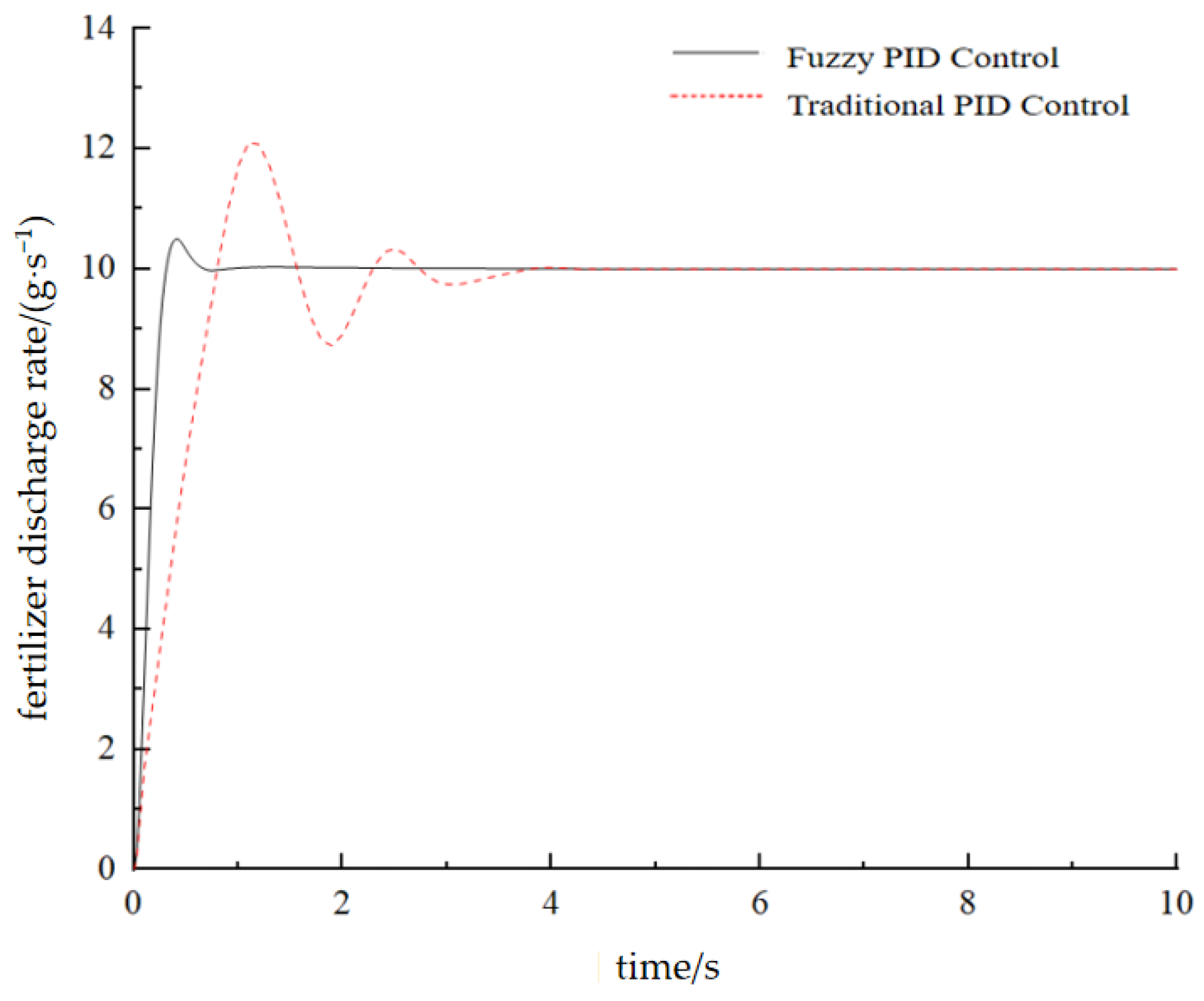

2.3.3. Fuzzy PID Control Simulation

2.3.4. System Control Principle

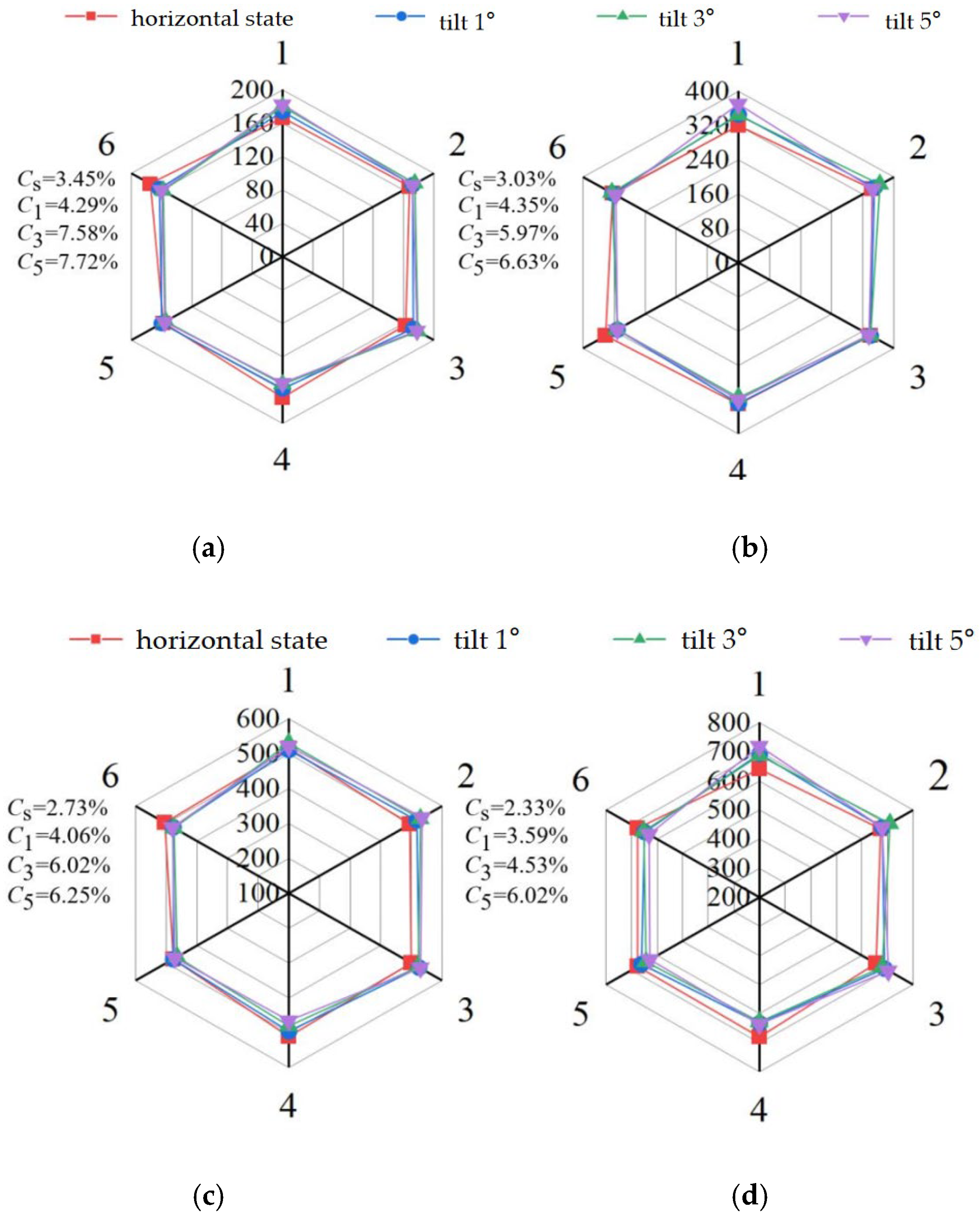

2.4. Simulation Analysis of Shunt Distribution Uniformity

2.4.1. Shunt Distribution Uniformity Simulation Test

2.4.2. Test Method

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Analysis of Flow Distribution Uniformity Test

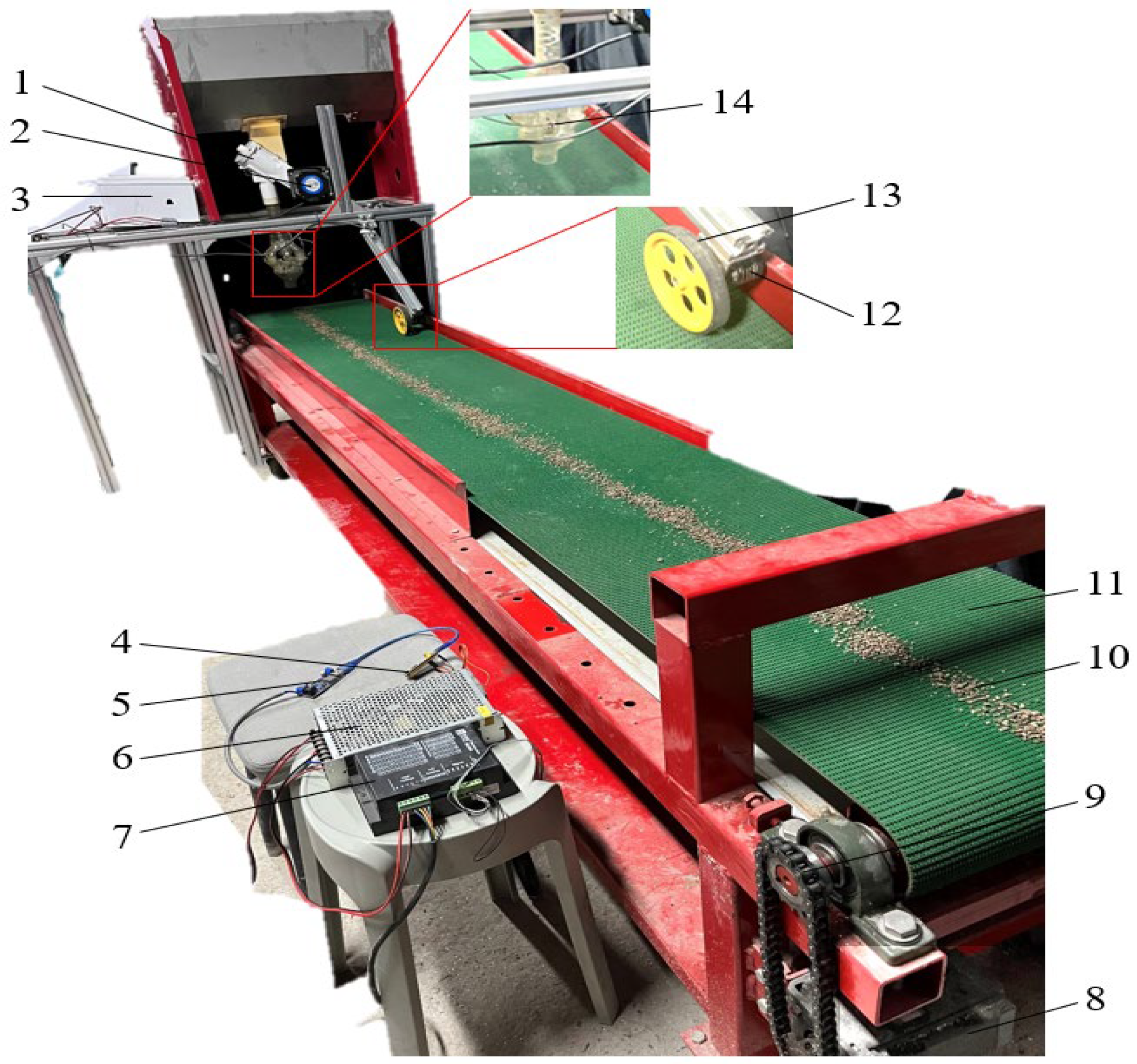

3.2. Rack and Field Tests

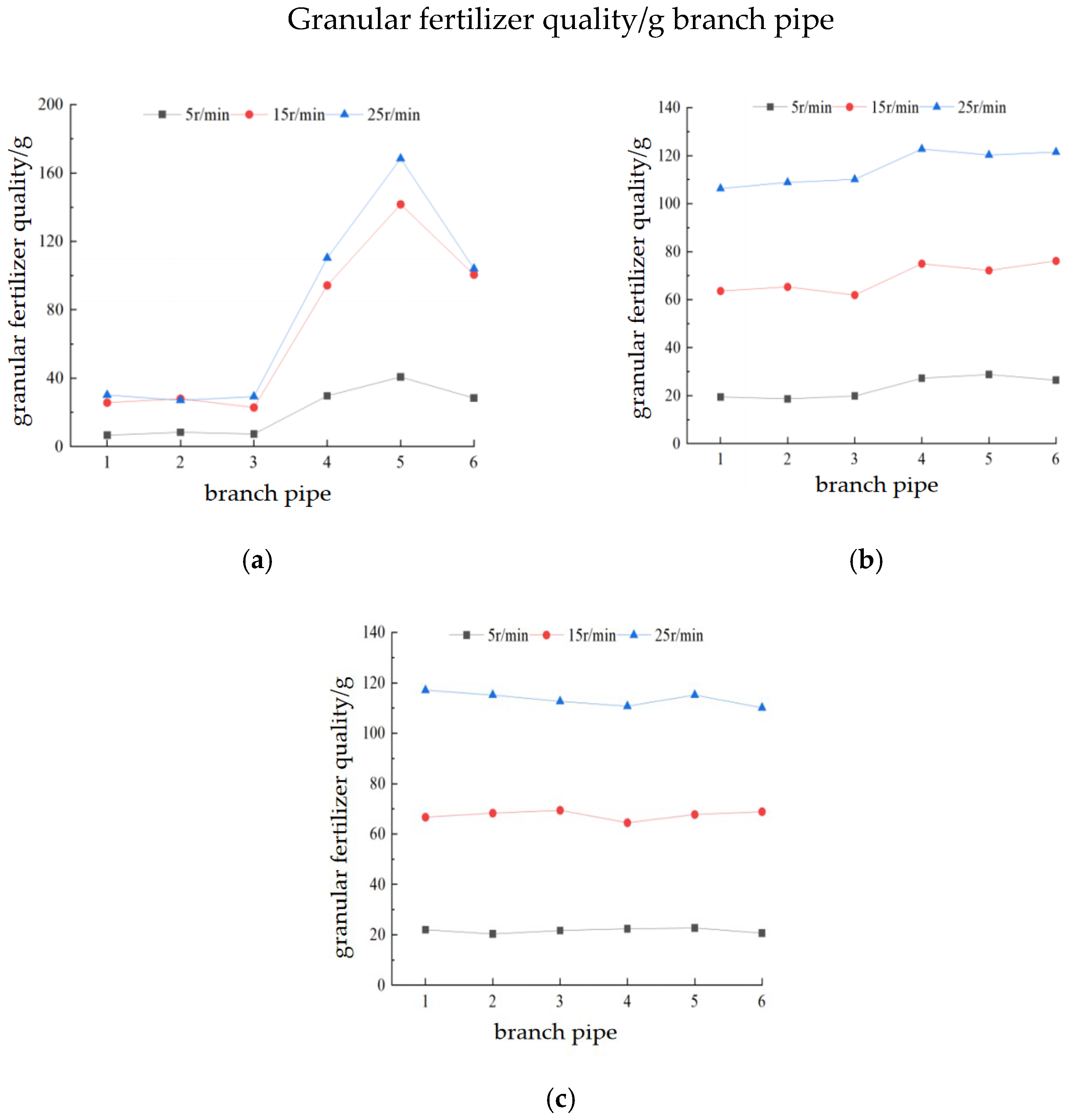

3.2.1. Shunt Distribution Uniformity Bench Test

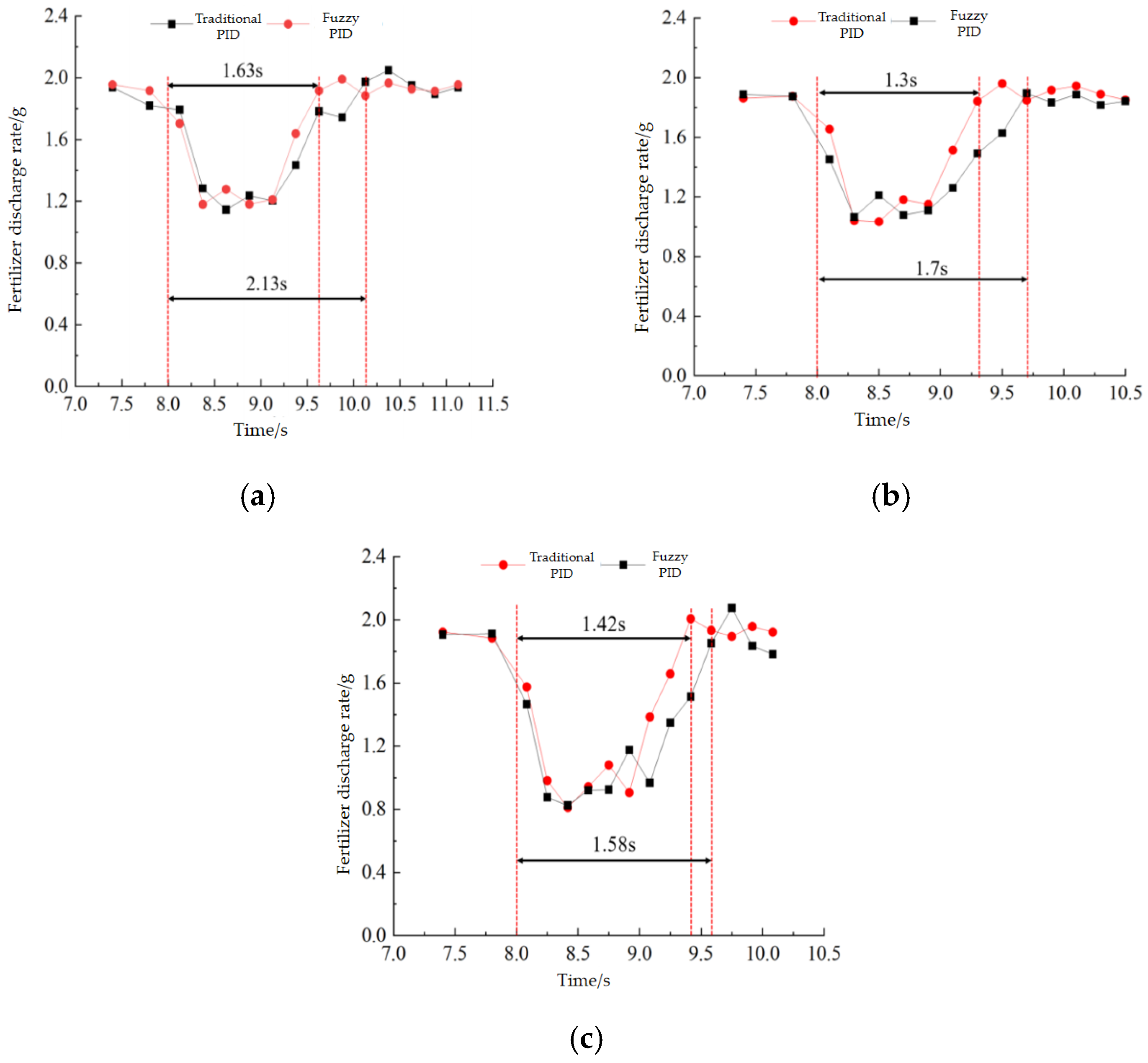

3.2.2. Performance Test of Response Time to Changes in Fertilizer Discharge Quantity

3.2.3. Fertilizer Discharge Quantity Control Accuracy Test

3.2.4. Field Experiment

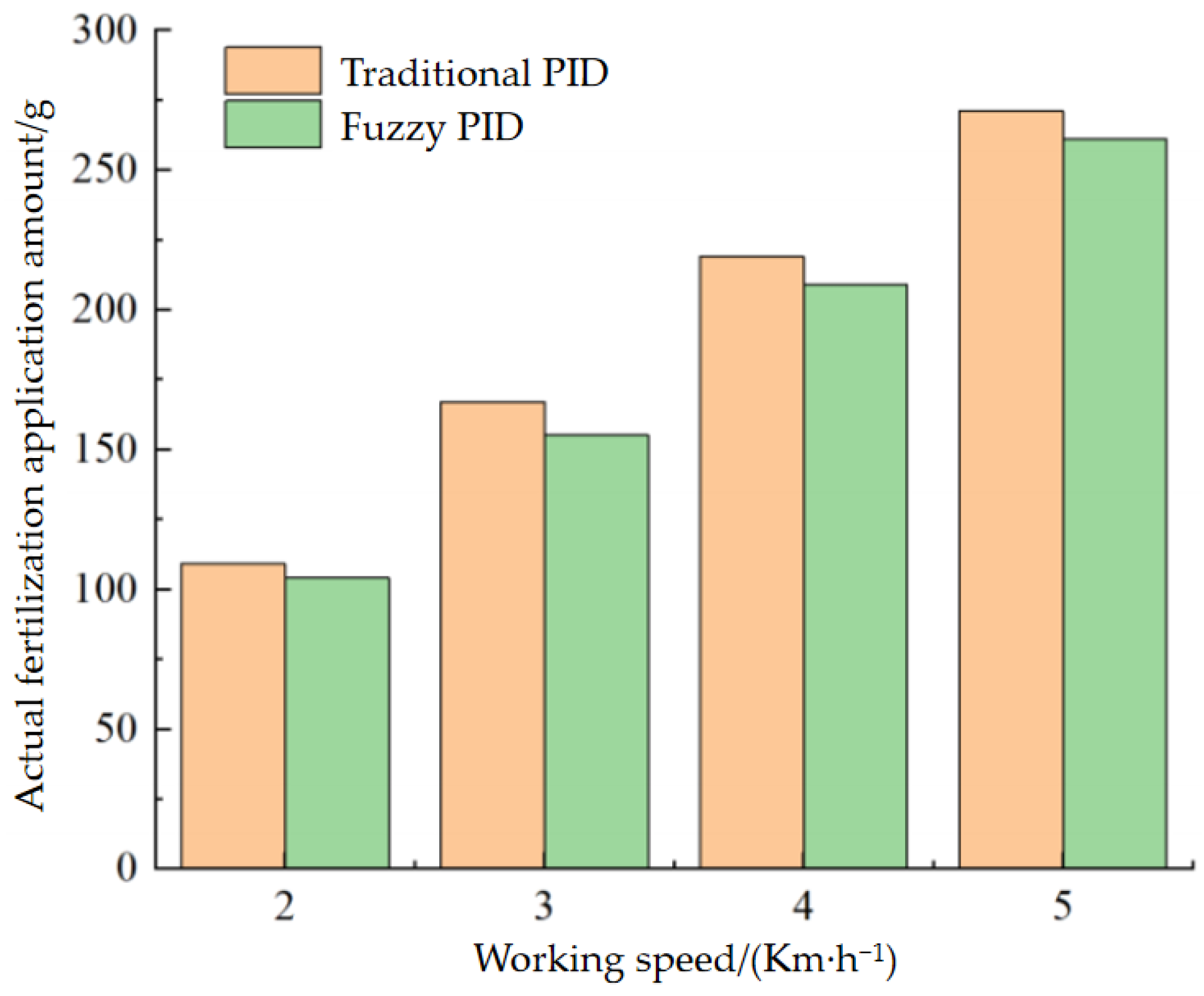

3.2.5. Test Results and Analysis

4. Current System Restrictions and Latest Developments

4.1. Current System Restrictions

- The current system has been optimized for specific fertilizer particle characteristics. In the future, it is necessary to establish a more universal particle physical parameter database, develop adaptive detection algorithms and control models, and improve the compatibility of the system with different shapes, densities, and humidity of granular fertilizers.

- Under extreme high humidity conditions close to 100% RH, PVDF sensors may experience performance degradation due to excessive adsorption of water vapor. Water vapor may condense on the surface or inside of the sensor, affecting its piezoelectric effect or conductivity, resulting in inaccurate or ineffective measurements; under extreme low humidity conditions close to 0% RH, PVDF sensors may not generate sufficient electrical signals due to a lack of sufficient interaction between water vapor molecules and sensitive materials. This may result in weak or unstable sensor output signals, thereby affecting their measurement accuracy. Try to avoid these two situations as much as possible when working.

- Mechanical vibration during high-speed field operations can easily cause sensor signal fluctuations and component fatigue. In the future, a multi-level damping structure can be designed to optimize the mechanical stability of the device, while exploring real-time filtering algorithms for vibration noise to further improve detection accuracy and control robustness.

4.2. Latest Developments

- Multi-channel parallel detection: Blue Rainbow Optoelectronics uses a rotating matrix design with 12 independent optical detection channels to shorten the detection time of N, P, and K for eight soil samples to within 1 h, with a sensitivity of red light ≥ 4.5 × 10−5. Compared to reference [1], the delay is smaller.

- Precision Rotating Colorimetric Cell: Yuntang Technology employs a precision rotating multi-channel colorimetric cell structure integrated with a constant-temperature control module. This design eliminates variations in light source intensity and thermal drift effects between channels, achieving absorbance measurement drift of <0.003 over one hour with error stability maintained at ≤1%. Compared to reference [6], it offers higher detection accuracy.

5. Conclusions

- A high-throughput parallel detection method for granular fertilizer diversion has been proposed. Parametric designs have been carried out for key components such as the uniform fertilizer tube, sensing detection structure, six-channel diversion cone disk, and converging fertilizer tube, and an innovative six-channel parallel detection device has been designed. Research has been conducted on the performance of diversion uniformity. When the generation speed of granular fertilizer is between 100 and 400 particles per second, the coefficient of variation in the diversion consistency in each diversion branch tube of the tilted diversion device gradually decreases with increasing generation speed. Under normal field operation at a tilt angle of 0° to 5°, the coefficient of variation in the diversion consistency in each diversion branch tube does not exceed 7.72%. A multi-channel signal synchronous acquisition system has been designed, and relationship models between the detection flow rate and voltage of granular fertilizer, as well as between the actual flow rate of granular fertilizer and the rotational speed of the fertilizer discharge shaft, have been established through calibration experiments.

- A real-time precision regulation system control model for fertilizer quantity was established, utilizing fuzzy rules to dynamically adjust the parameters of the PID controller. A fuzzy PID control simulation model was created using MATLAB’s Simulink simulation module to analyze the PID parameters of the controlled object and study the system’s response speed and overshoot. The control effects of fuzzy PID and traditional PID algorithms were compared. The results showed that fuzzy PID control reduced the time required to reach steady state by 66.87% compared to traditional PID, and the overshoot decreased from 7.38 g·s−1 to 1.49 g·s−1.

- Bench tests and field trials were conducted. The results of the bench tests showed that the average response time for fertilizer discharge rate changes under fuzzy PID control was 1.45 s, with an average reduction of 19.44% compared to traditional PID control. The minimum and average control accuracy of fertilizer discharge rate under fuzzy PID control was 95.50% and 95.94%, respectively, representing an average improvement of 5.50% over traditional PID control. Under different test conditions, both the response time for fertilizer discharge rate changes and the control accuracy of fertilizer discharge rate under fuzzy PID control were superior to those under traditional PID control. In field trials, when the operating speed was 2, 3, 4, and 5 km·h−1, the control accuracy of fertilizer discharge rate under the fuzzy PID control system reached 96.22%, 95.13%, 95.42%, and 95.36%, respectively, with an average of 95.53%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Tian, H. A fertilizer discharge detection system based on point cloud data and an efficient volume conversion algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumhála, F.; Kvíz, Z.; Kmoch, J.; Prošek, V. Dynamic laboratory measurement with dielectric sensor for forage mass flow determination. Res. Agric. Eng. 2007, 184, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Jin, Z.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y. Research on Microwave Signal Measurement of Particle Fertilizer Flow Rate Based on Variational Mode Decomposition Combined with Wavelet Analysis. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ma, M.; Yuan, Y. Design and experiment of fertilizer application amount detection system based on capacitive method. J. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Han, J.; Niu, Z. Collection and Experimental Study of Millimeter Wave Radar Particle Fertilizer Discharge Signal Based on CAFA-PF. China Agric. Sci. Technol. Guide 2025, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C. Design of a monitoring system for wheat precision sowing and fertilizing integrated machine based on variable-range photoelectric sensor. J. Agric. Eng. 2018, 34, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, J.; Su, Q. Design and experiment of a thin-film light refracting multi-channel parallel detection device for wheat seed flow. J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, D. Research status and prospects of variable application control technology for solid granular fertilizer. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2022, 50, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John Deere. RelativeFlowTM Jam Monitoring. Available online: www.deere.com/en/seeding-equipment/ (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Iida, M.; Umeda, M.; Radite, P.A.S. Variable rate fertilizer applicator for paddy field. In Proceedings of the Annual International Meeting of the American Society of Agricultural Engineers, Sacramento, CA, USA, 30 July–1 August 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, M.R.; Ramon, H.; De Baerdemaeker, J. A study on the time response of a soil sensor. based variable rate granular fertilizer applicator. Biosyst. Eng. 2008, 100, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Ji, W. Research on Precise Application Control System for Multiple Solid Fertilizers Based on Incremental PID Algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2021, 52, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S. Design and experiment of variable-rate fertilization device for solid granular fertilizer on high-speed rice transplanter. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L. Design and experiment of a segmented PID control system for fertilizer flow rate of a fertilizer and seeding machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 32–40+94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Lu, W.; Wang, X. Design and experiment of optimal control system for variable topdressing of winter wheat based on fuzzy PID. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2016, 47, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. Research on the Vibration Characteristics of a Small-Sized Fertilizer Seed and Its Impact on Fertilizer Discharge Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, K. Design and experiment of seed flow sensing device for precision seed metering device of rapeseed. J. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, X.; Zeng, S. Performance test and analysis of adaptive contour-following cutting platform for ratooning rice based on fuzzy PID control. J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, J. Fuzzy PID simulation analysis of stepper motor drive system. J. Mech. Des. Manuf. 2014, 12, 23–25+29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, X.; Ji, C. Design and experiment of single-unit driver for precision corn seeder based on fuzzy PID control. J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input and Output Variables | e | ec | ∆kP | ∆ki | ∆kd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| language variable | E | EC | ∆KP | ∆Ki | ∆Kd |

| Basic Domain | [−30, 30] | [−15, 15] | [−1, 1] | [−0.5, 0.5] | [−2, 2] |

| fuzzy subset | [NB NM NS ZE PS PM PB] | ||||

| fuzzy universe | [−3, 3] | [−1.5, 1.5] | [−3, 3] | [−1.5, 1.5] | [−6, 6] |

| quantitative factor | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Parameter | ec | e | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | NM | NS | ZO | PS | PM | PB | ||

| ∆KP | NB | PB | PB | PM | PM | PS | ZO | Z0 |

| NM | PB | PB | PM | PS | PS | ZO | NS | |

| NS | PM | PM | PM | PS | ZO | NS | NS | |

| ZO | PM | PM | PS | ZO | NS | NM | NM | |

| PS | PS | PS | ZO | NS | NM | NM | NM | |

| PM | PS | ZO | NS | NM | NM | NM | NB | |

| PB | ZO | ZO | NM | NM | NB | NB | NB | |

| ∆Ki | NB | NB | NB | NM | NM | NS | ZO | ZO |

| NM | NB | NB | NM | NS | NS | ZO | ZO | |

| NS | NB | NM | NS | NS | Z0 | PS | PS | |

| ZO | NM | NM | NS | Z0 | PS | PM | PM | |

| PS | NM | NS | ZO | PS | PS | PM | PB | |

| PM | ZO | ZO | PS | PS | PM | PB | PB | |

| PB | ZO | ZO | PS | PM | PM | PB | PB | |

| ∆Kd | NB | PS | NS | NB | NB | NB | NM | PS |

| NM | PS | NS | NB | NM | NM | NS | ZO | |

| NS | ZO | NS | NM | NM | NS | NS | ZO | |

| ZO | ZO | NS | NS | NS | NS | NM | ZO | |

| PS | ZO | ZO | ZO | ZO | Z | ZO | ZO | |

| PM | PB | NS | PS | PS | PS | PS | PB | |

| PB | PB | PM | PM | PM | PS | PS | PB | |

| Working Speed/(km·h−1) | Target Fertilizer Discharge Rate/(g) | System Type | Actual Fertilizer Discharge/(g) | Fertilizer Application Rate Control Accuracy/(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 300 | Traditional PID | 266.29 | 88.76% |

| 328.43 | 90.52% | |||

| 274.97 | 91.66% | |||

| Fuzzy PID | 312.81 | 95.73% | ||

| 310.03 | 96.66% | |||

| 288.85 | 96.28% | |||

| 3 | 450 | Traditional PID | 496.57 | 89.65% |

| 411.65 | 91.48% | |||

| 509.48 | 86.78% | |||

| Fuzzy PID | 472.30 | 95.04% | ||

| 471.52 | 95.22% | |||

| 428.09 | 95.13% | |||

| 4 | 600 | Traditional PID | 658.30 | 90.28% |

| 652.46 | 91.26% | |||

| 688.36 | 85.27% | |||

| Fuzzy PID | 571.89 | 95.32% | ||

| 625.74 | 95.71% | |||

| 628.66 | 95.22% | |||

| 5 | 750 | Traditional PID | 834.34 | 88.75% |

| 818.25 | 90.90% | |||

| 683.04 | 91.07% | |||

| Fuzzy PID | 785.65 | 95.25% | ||

| 781.73 | 95.77% | |||

| 786.95 | 95.07% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ding, L.; Wu, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, B.; Dou, Y. Design and Experimentation of High-Throughput Granular Fertilizer Detection and Real-Time Precision Regulation System. Agriculture 2026, 16, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030290

Ding L, Wu F, Li Y, Wang K, Yuan Y, Liu B, Dou Y. Design and Experimentation of High-Throughput Granular Fertilizer Detection and Real-Time Precision Regulation System. Agriculture. 2026; 16(3):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030290

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Li, Feiyang Wu, Yuanyuan Li, Kaixuan Wang, Yechao Yuan, Bingjie Liu, and Yufei Dou. 2026. "Design and Experimentation of High-Throughput Granular Fertilizer Detection and Real-Time Precision Regulation System" Agriculture 16, no. 3: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030290

APA StyleDing, L., Wu, F., Li, Y., Wang, K., Yuan, Y., Liu, B., & Dou, Y. (2026). Design and Experimentation of High-Throughput Granular Fertilizer Detection and Real-Time Precision Regulation System. Agriculture, 16(3), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16030290