1. Introduction

In 2024, the total cultivated land area in South Korea was 1,504,615 hectares. Although the number of farm households and the agricultural population have continuously decreased over the past decade, the proportion of farmers aged 65 years and older has steadily increased and now accounts for more than half of the total farming population. This demographic shift inevitably leads to an increase in the cultivated area managed per farmer, thereby imposing a significant burden on open-field crop management, particularly when combined with aging-related labor constraints [

1].

To address this aging farm population, Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based smart farming is gaining significant attention as a solution for reducing labor requirements and enhancing management efficiency [

2].

AI-based smart farming is a third-generation agricultural technology. However, despite its technological maturity, the actual adoption rate of smart farming remains relatively low, at approximately 11% based on the most recent officially available statistics, especially in open-field environments. This gap is particularly notable given that horticultural facilities provide more controlled conditions for smart-farm deployment, whereas open-field agriculture faces greater challenges related to environmental variability, cost, and infrastructure limitations [

3].

As a result, the onsite settlement of AI-driven third-generation smart farming systems remains limited in real-world open-field conditions. Existing AI-based solutions for open-field agriculture can generally be categorized into two main approaches: cloud-centric architectures that rely on centralized servers and data transmission, and lightweight edge-based systems that aim to operate under constrained computing and network environments. In this study, we propose an Internet of Things (IoT)-based end-to-end (E2E) smart farming solution specifically tailored for open-field environments, with an emphasis on local processing, system robustness, and real-time operability.

The primary factors hindering the application of smart farming in open fields are summarized as three key challenges: difficulty in responding to environmental variables, high implementation costs, and network instability [

4]. This study aimed to resolve these issues and facilitate the practical adoption of AI-based smart farming systems in open-field environments through a deployment-oriented Edge AI architecture that emphasizes system integration, reliability, and real-time operability under resource constraints. The objective of this study is to design and experimentally validate an on-premise, resource-constrained edge AI system capable of performing real-time pest and disease detection at the farm-unit level. The novelty of this work lies in its system-level design, which integrates a lightweight Leaf-first 2-Stage with low-cost edge hardware and resilient communication mechanisms, rather than introducing new learning algorithms.

The specific contributions of this research are as follows: First, chili pepper plants typically feature dense foliage, averaging 50 to 70 leaves per plant. To accurately detect minute lesions within these dense clusters, we designed a Leaf-first 2-Stage pipeline that strategically combines existing lightweight detection and classification models. This approach significantly improves the recognition rate of infected objects, enabling stable pest and disease detection even against complex open-field backgrounds, while remaining suitable for resource-constrained edge environments.

Second, unlike expensive cloud-based systems, we constructed a cost-effective IoT architecture using AI-Thinker ESP32-CAM module (ESP32-CAM) and Raspberry Pi. This edge-based standalone system was designed to perform AI-based diagnoses by simply powering the device. Consequently, it allows aging farmers who may not be familiar with smart devices to use the system intuitively without requiring specialized training.

Finally, using a communication design that combines modular hardware with Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) and Hyper Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP) protocols, we optimized the stable transmission of image data and diagnostic results, even in unstable network environments. Thus, we aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of using low-cost hardware as a reliable component of open-field smart farms.

2. Related Work

2.1. Object Detection and Disease Diagnosis in Agriculture

Previous studies have applied You Only Look Once (YOLO)–based models to various agricultural tasks, including crop row detection and plant localization, which serve as the basis for agricultural machinery trajectory planning and field automation [

5]. The YOLO series is a convolutional neural network (CNN)–based one-stage real-time object detection framework, widely adopted due to its favorable balance between detection accuracy and inference speed [

6].

In the context of crop disease diagnosis, YOLO-based models have been extensively used to detect symptomatic regions on leaves and fruits. However, standard YOLO architectures, including YOLOv8, exhibit limitations in capturing fine-grained features under conditions of severe occlusion, geometric deformation, and morphological variability commonly observed in open-field crops [

7]. This issue is particularly pronounced in dense foliage environments, where disease symptoms are often small and partially hidden.

To address these challenges, prior studies have proposed enhanced YOLO variants, such as DCGA-YOLOv8, which incorporates deformable convolution (DCN) to improve spatial adaptability and global attention mechanisms (GAM) to emphasize disease-relevant regions [

5]. While these approaches improve detection robustness, they typically increase model complexity and computational overhead, making them less suitable for deployment on low-cost edge devices.

In contrast to prior studies that primarily focus on improving detection backbones or attention mechanisms within a single-stage framework, this study adopts a pipeline-level strategy that separates leaf localization and disease classification to better accommodate dense foliage and small lesion characteristics under edge deployment constraints.

2.2. Edge AI and Model Lightweighting

Recent studies have explored lightweight deep learning models for plant disease detection to enable deployment on resource-constrained platforms. For example, improved YOLOv8n variants incorporating lightweight modules such as C2f-Ghost have been proposed to reduce parameter counts while preserving detection accuracy for chili pepper diseases [

7]. Similarly, hybrid modules combining convolutional neural networks and attention mechanisms, such as C2f-iRMB, have demonstrated improved computational efficiency and feature representation capability [

8].

Beyond model architecture optimization, several studies have investigated Edge AI–based agricultural systems that integrate sensing, inference, and feedback within local environments to reduce reliance on cloud infrastructure. These systems highlight the importance of communication reliability, latency control, and fault tolerance in real-world agricultural deployments.

Unlike prior works that primarily emphasize model-level optimization, this study focuses on the system-level integration of lightweight vision models with low-cost IoT hardware and robust communication mechanisms. By combining YOLOv8n-based leaf detection with a ResNet-18 classifier in a fully on-premise edge architecture, the proposed approach addresses not only model efficiency but also end-to-end operational reliability under unstable network conditions.

Recent studies have also highlighted the limitations of cloud-centric IoT architectures in agricultural environments. Cloud-based systems often suffer from increased latency, recurring operational costs, and strong dependence on stable network connectivity, which can be problematic in open-field farming scenarios. In contrast, edge-based architectures enable localized data processing and real-time responsiveness while reducing communication overhead. While cloud platforms provide scalability and centralized management, edge-centric designs are increasingly favored in agriculture due to their robustness, lower latency, and suitability for environments with unreliable connectivity [

9].

Motivated by these observations, this study adopts a fully on-premise edge deployment strategy, prioritizing real-time operability, low cost, and system resilience over cloud-dependent processing.

3. Materials and Methods

This section introduces the proposed system configuration and experimental setup used in this study. The system consists of multiple observation nodes (“Sticks”) and a centralized edge-processing unit (“Module”). Each Stick is implemented using an ESP32-CAM module (Shenzhen Ai-Thinker Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) based on the ESP32 chip (Espressif Systems (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), equipped with an OV2640 image sensor (OmniVision Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a standard commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) RGB LED. The Module is implemented using a Raspberry Pi 5 Compute Module (Raspberry Pi Ltd., UK). Firmware for the ESP32 devices is developed using the Arduino IDE (Arduino SA, Ivrea, Italy), while the server-side processing and communication are implemented using Flask (Pallets Project, San Francisco, CA, USA) and Redis (Redis Ltd., Mountain View, CA, USA).

3.1. Proposed System and Experiment Setup

We propose a system configuration where multiple observation nodes, termed “Sticks” (Arduino ESP32-CAM), were connected to a central processing unit, termed “Module” (Raspberry Pi 5 Compute Module) [

10]. The proposed system used a dual-protocol approach combining HTTP and MQTT and was designed to operate as a plug-and-play solution that requires no complex manual intervention from the user [

11].

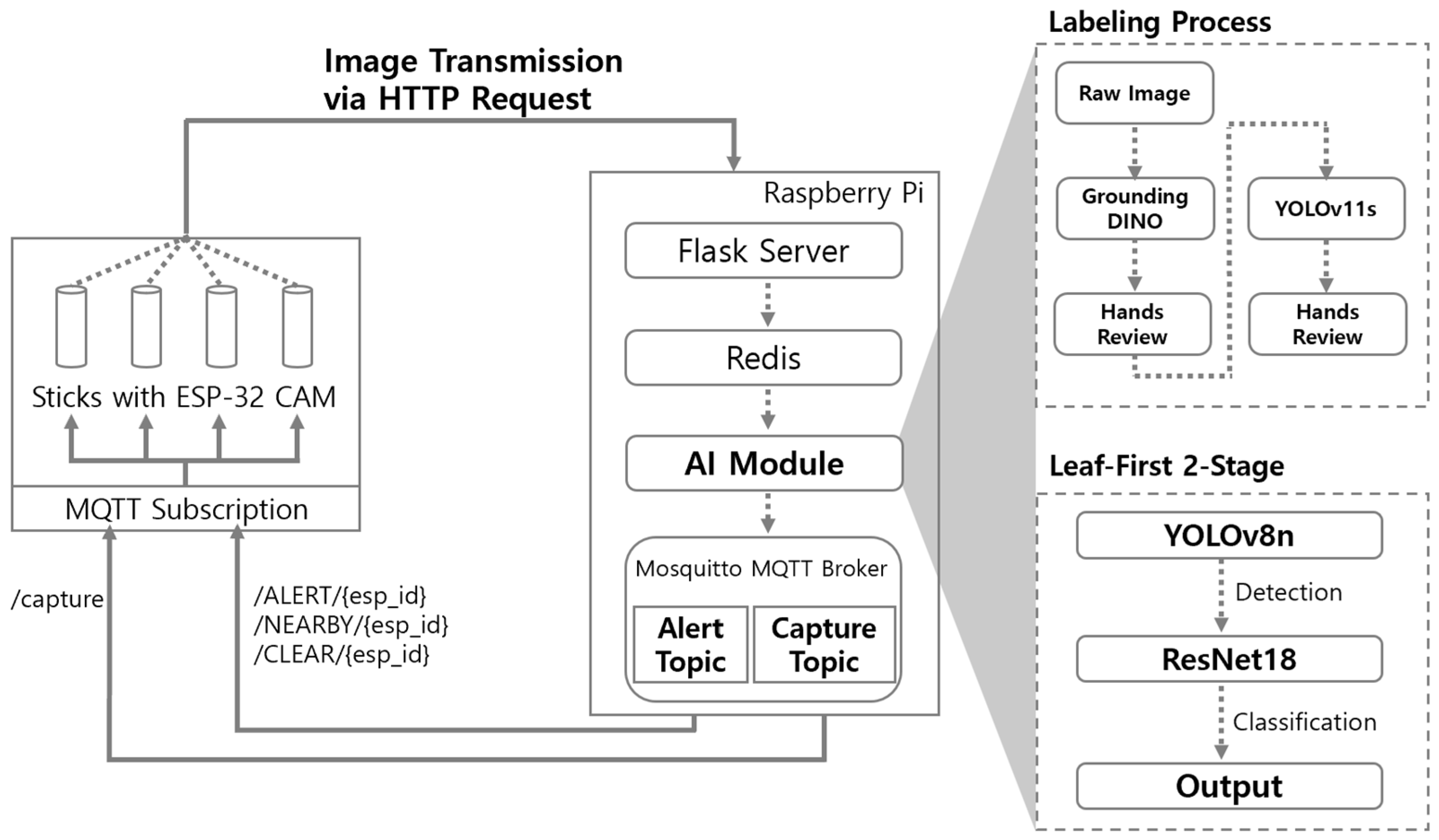

Figure 1 illustrates the overall flow of the system architecture. Images of chili pepper plants captured by the Stick are transmitted via HTTP to the Module, which functions as a local edge server [

12]. The AI model embedded in the Module then performs an inference to diagnose the condition of the crops. Based on the analysis results, the Module sends a control signal back to the Stick to manipulate the attached Red, Green, Blue Light Emitting Diode (RGB LED) and provide immediate visual feedback.

This standalone architecture, designed to enable automatic device interaction upon simple power-up without reliance on external internet connectivity, ensures that aging farmers unfamiliar with electronic devices can easily use this AI-based pest-detection system without requiring specialized training. All system integration and end-to-end latency experiments were performed in 2025 using the hardware configuration described in this section.

From a hardware implementation perspective, the proposed system consists of multiple ESP32-CAM–based imaging nodes (Sticks) deployed at fixed locations within the cultivation area and a single Raspberry Pi–based edge server (Module) installed at the farm unit level. Each Stick operates as an independent sensing and actuation device, integrating image acquisition, wireless communication, and LED-based visual feedback within a single compact unit.

The Module functions as a centralized on-premise processing unit that receives image data from all Sticks, performs AI inference locally, and coordinates system-wide control signals. This physical separation between distributed sensing nodes and a local edge server enables scalable deployment while maintaining low hardware cost and minimizing overall system complexity.

3.2. Modular Hardware

3.2.1. Stick

This section describes the physical hardware components and their respective roles within the proposed edge-based smart farming system. The “Stick” serves as the data acquisition node and consists of an ESP32-CAM module, an OV2640 image sensor, and an RGB LED. The ESP32-CAM, acting as the main controller, supports computation, communication, and storage capabilities within a single system-on-chip (SoC). For development, the AI-Thinker ESP32-CAM module was used as the target hardware board. This module is based on the Espressif ESP32 chip and was programmed using the Arduino IDE [

13].

This module integrates built-in Wi-Fi (802.11 b/g/n) and Bluetooth 4.2 functionalities [

14], eliminating the need for additional external communication modules in the circuit. This simplification enhances the mechanical reliability and reduces the potential failure rate of the hardware in open-field environments characterized by fluctuating humidity and temperature [

15].

An OV2640 sensor module was used for crop image acquisition. OV2640 supports a maximum resolution of 2 MP (1600 × 1200, UXGA) and features built-in hardware Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) compression. This capability not only alleviates the memory burden on the ESP32 by reducing the data size but is also expected to minimize power consumption for the Stick, which requires continuous 24 h operation [

16].

For the status notification, a standard commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) RGB LED compatible with an Arduino was used. Specifically, we selected a large 10 mm unit with a clear lens type, which offers high directionality compared to the diffused types. This design ensures that farmers can clearly identify the LED warning signal from a distance when an anomaly is detected in the chili pepper crops.

3.2.2. Module

We selected the Raspberry Pi 5 16 GB model as the “Module,” the central processing unit responsible for receiving crop images from the Sticks and diagnosing pests and diseases [

17]. As a single-board computer (SBC), the Raspberry Pi model is based on a SoC architecture that integrates the CPU, GPU, and RAM [

18]. This design has the advantage of functioning as an independent edge server without requiring complex peripheral circuit configurations [

19].

The Raspberry Pi 5 model features a 2.4 GHz quad-core Cortex-A76 CPU and 16 GB of LPDDR4X RAM, providing sufficient performance for on-device AI inference. It supports dual-band 802.11ac Wi-Fi, Bluetooth 5.0/BLE, and high-speed microSD storage [

20].

The device was acquired for approximately 200,000 KRW, making it a cost-effective alternative to expensive industrial servers and aligning with our objective of developing a low-cost smart farm solution [

21].

The training of the AI model embedded in the Module was conducted on a high-performance external device (workstation) to maximize the computational efficiency [

22]. Considering the limited resources of the edge device, we adopted a strategy of training the YOLOv8n model externally and then porting the optimized weights to the Module for inference. Consequently, the “Leaf-First 2-Stage” pipeline, which is described in detail in

Section 3.4, was implemented on the Module to perform real-time analysis.

3.3. Communication

3.3.1. Wireless Communication Options

Wi-Fi offers significant advantages in terms of universality and compatibility because the modules are standard in most digital devices and adhere to global protocols [

23]. The Industrial, Scientific, and Medical (ISM) band provides a wide bandwidth, enabling high-speed communication [

24]. Additionally, Wi-Fi allows for convenient experimentation using common access points, and both the ESP32-CAM and Raspberry Pi 5 include built-in Wi-Fi modules by default. Therefore, Wi-Fi was selected as the wireless communication method for this study.

3.3.2. Communication Architecture

The communication architecture of the proposed system operates on an asynchronous framework in which the ESP32-CAM periodically captures crop images and uploads them to a Flask server. These images are then queued in Redis, allowing the AI module to process them sequentially [

25]. Based on the AI analysis results, the control signals were published via the MQTT protocol to manage the LED status of each ESP32 device in real time [

26].

Specifically, the ESP32 transmits captured images as a JPEG binary stream to the upload endpoint of the Flask server [

27]. The HTTP header includes a unique identifier (esp_id) to distinguish the source node (Stick) [

28]. The payload consists of JPEG minimum coded units (MCUs) encoded in RGB565 format, allowing the receiver to reconstruct the image block-by-block, even under packet loss [

29]. Upon receipt, the Flask server converts the raw binary payload into a hexadecimal string and stores it in the Redis queue for asynchronous processing.

This architecture ensures the integrity of the binary data while providing loose coupling via asynchronous messaging through Redis. This design prevents computational latency during AI inference from creating bottlenecks in the image reception or network upload performance. Consequently, Redis functions not only as a message buffer, but also as a core middleware module that facilitated asynchronous processing and fault tolerance in data transmission [

30]. A summary of the Redis features is presented in

Table 1.

The MQTT protocol serves as a reliable bidirectional control channel between the ESP32 (Stick) and Raspberry Pi (Module). The topics are structured as shown in

Table 2.

All ESP32 nodes subscribed to these topics and immediately controlled their hardware (LEDs) in response to the received events. Notably, the farm/capture signal was broadcast to all devices simultaneously to induce synchronized image capture across the entire sensor network.

The analysis results from the AI module were categorized into three states: ALERT, NEARBY, and CLEAR. These states were disseminated to each device via the MQTT based on the following control algorithm:

1. Detection: Upon detection of a pest or disease, an ALERT topic is published to a specific node Identity (ID).

2. Propagation Warning: When an ALERT is triggered, a NEARBY topic is automatically published to the adjacent nodes (ID $\pm$ 2). This logic was designed to visualize the potential spatial spread of infestations without requiring Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates.

3. State Persistence: The ALERT status persists until an explicit CLEAR topic is published. Conversely, the NEARBY status operates independently of the CLEAR signal to maintain heightened caution in the surrounding area.

This spatial logic not only intuitively represents the diffusion path of pests within the farm but also prevents LED malfunctions caused by message collisions. Upon receiving a message within the MQTT callback function, the ESP32 immediately updated the LED color according to the mapping rules listed in

Table 3, thereby providing real-time visual feedback for onsite monitoring.

3.3.3. Communication Reliability and Fault Tolerance Design

The proposed architecture functionally decouples the HTTP and MQTT protocols, thereby eliminating the interference between high-volume data traffic and lightweight control signals. HTTP is dedicated to the transmission of large JPEG images, whereas MQTT handles event-driven real-time control. This separation ensures bandwidth efficiency and network resilience [

31].

The specific mechanisms for ensuring reliability are as follows. First, in the event of an HTTP upload failure, the ESP32 triggers an automatic retry logic and simultaneously illuminates the LED in yellow, providing immediate visual feedback regarding the communication fault [

32]. Second, for MQTT communication, QoS Level 0 was adopted to minimize latency. To compensate for the potential message loss inherent in QoS 0, we used Redis for state synchronization. Even if a message is transiently lost, the system was designed to recover automatically at the next synchronization point based on the latest state information stored in Redis, thereby ensuring data reliability [

33]. Third, unlike standard MQTT clients that rely on a 60 s Keep-Alive cycle, this system employs an aggressive recovery strategy. The MQTT connection routine (implemented in a function named connectMQTT()) on ESP32 detects session disconnections and performs immediate reconnection and re-subscription [

26].

3.4. Vision Pipeline (Leaf-First 2-Stage)

The vision system proposed in this study adopted a “Leaf-First 2-Stage” pipeline architecture. Instead of relying on a single model to perform all tasks, this approach serially integrates two independent models, one for object detection and the other for object classification, to increase analysis precision.

3.4.1. Stage-1: Object Detection by YOLOv8n

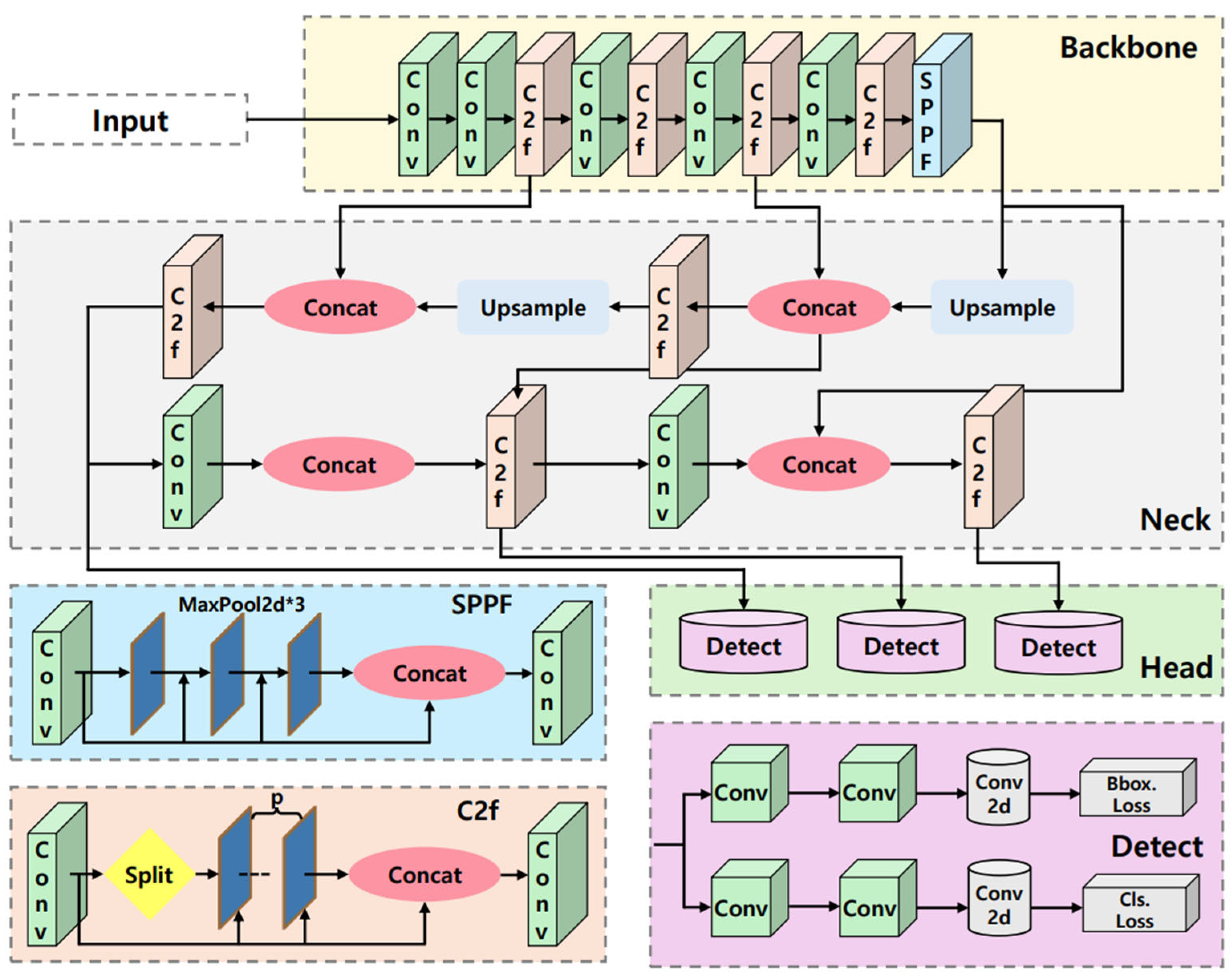

Figure 2 illustrates the overall architecture of YOLO. YOLO is a single-stage object detector that predicts the object locations in a single forward pass. The backbone extracts key visual patterns from the input image, the neck aggregates multiscale feature maps, and the detection head directly outputs bounding boxes and class scores at each grid or anchor point. The final output consists of bounding boxes and their corresponding confidence and class scores, followed by non-maximum suppression (NMS) to remove redundant detections.

In this study, YOLO was used in stage-1 to localize chili pepper leaves and pass the cropped regions to the stage-2 classifier (ResNet).

Chili pepper leaves are not merely classes to be categorized but are individual objects that require precise localization within a complex environment. Therefore, we constructed a leaf detection model using YOLOv8n, which identified objects based on bounding boxes [

34].

Unlike its predecessors, YOLOv8n adopts an anchor-free mechanism that does not rely on predefined anchor boxes. This approach reduces the number of unnecessary box predictions, thereby enhancing inference speed and efficiency [

5]. Such characteristics are particularly advantageous for detecting agricultural crops such as chili leaves, which exhibit irregular sizes and non-rigid shapes.

To maximize the recognition rate for small objects, such as chili leaves, we optimized the Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV), geometric, and mosaic augmentation techniques embedded in YOLOv8n. The specific parameter settings for the training pipeline were as follows:

To configure the detection setup for YOLOv8n·v8s and YOLOv11n·v11s, we applied a combination of color and spatial data augmentation techniques, as detailed in

Table 4, to improve robustness against variations in lighting, color, and framing. Unless otherwise stated, all numerical values correspond to normalized ratios or probabilities.

Color Augmentation: HSV jitter parameters were set to h = 0.015, s = 0.7, and v = 0.4.

Spatial Augmentation: Translation was applied within a range of 0.1, and scaling within 0.5. A horizontal flip was enabled with a probability of 0.5, whereas the vertical flip, shear, and perspective transformations were disabled.

Mosaic Augmentation: To improve the representation of small objects, mosaic augmentation was activated only during the first ten epochs of training and was subsequently disabled.

Others: Mixup, cut mix, and copy paste were not used. Autoaugmentation was set to random augmentation, and random erasing was applied with an intensity limit of 0.4.

Despite its detection advantages, YOLOv8n employs a backbone that progressively down samples feature maps to accelerate computation. This structural characteristic leads to a loss of fine-grained details, presenting a weakness in distinguishing between the normal and abnormal states of an object [

35]. To overcome this limitation in classification accuracy, we integrated ResNet-18 as the second stage of the vision pipeline, as described in

Section 3.4, thereby ensuring both detection performance and diagnostic precision.

3.4.2. Stage-2: Object Classification by ResNet-18

Stage-2, responsible for classification, was constructed using the ResNet-18 architecture. Unlike YOLOv8n in the previous stage, which focuses on object localization, ResNet-18 does not perform bounding box regression. Instead, they focus exclusively on distinguishing the semantic attributes of detected objects [

36,

37].

In general, deep CNNs suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, in which gradients diminish during backpropagation as the network depth increases, thereby hindering training [

38]. To address this issue, ResNet introduces shortcut connections that add input data directly to the output. This mechanism is mathematically expressed as follows:

In ResNet, the residual mapping is defined as

, where

denotes the learned transformation implemented by convolutional layers and

represents the input signal propagated through an identity mapping. By directly adding the input

to the output of the learned transformation, ResNet minimizes information loss during backpropagation and effectively mitigates the vanishing gradient problem. This identity mapping enables stable training even as network depth increases and prevents the progressive degradation of feature representations across layers. Consequently, this architectural characteristic plays a critical role in preserving and extracting fine-grained visual features, such as minute lesions on crop leaves, which are essential for accurate classification in the proposed system [

39,

40].

For the classification setup using ResNet-18 and ResNet-50, as summarized in

Table 5, the training pipeline involved resizing input images to 224 × 224, followed by horizontal flipping (

p = 0.5), rotation (±10°), and ColorJitter augmentation (brightness = 0.2, contrast = 0.2, saturation = 0.2, and hue = 0.1). The augmented images were then converted to tensors and normalized using ImageNet statistics (mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406], standard deviation = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]). For validation and testing, only resizing and normalization were applied to eliminate augmentation-induced variability.

3.5. Model Lightweighting and Optimization

To realize a low-cost, high-efficiency pest detection device, this study used the Raspberry Pi 5 compute module, a device with limited computing resources, as described in

Section 3.2.2. Computational efficiency is a critical requirement considering the system’s ability to perform the entire inference process locally on the edge device.

Consequently, the lightest model in the YOLO series, YOLOv8n, was adopted for the object detection stage. For the classification stage, ResNet-18 was selected instead of the larger ResNet-50 to prioritize the balance between lightweight architecture and accuracy.

The conversion and deployment processes for the trained model weights on the edge device followed model-specific optimization paths [

41]. The full implementation of the overall pipeline, including stick-to-module communication and Leaf-First 2-Stage framework, is available on GitHub at

https://github.com/sydney0716/spoiled-pepperleaf-detector-classifier (accessed on 11 January 2026).

3.6. End-to-End Operation and Latency Definition

3.6.1. Latency Definition Method

To compare the operational efficiency of the end-to-end (E2E) pipeline, we introduced the metric.

The metric was used as a key performance indicator (KPI) to assess the operational efficiency of the low-cost smart-farm IoT system architecture under real-world conditions. This metric was used to quantitatively analyze and report changes in the system performance and real-time capability throughout subsequent iterative experiments.

As illustrated in

Figure 1 in

Section 3.1, the ESP32-CAM on the Stick captures an image and transmits it to the Module. The onboard AI model then infers the presence of pests or diseases based on the image and sends the result back to the Stick to control the LED status accordingly.

The LED indicates the status of the crop through visual feedback, following the definitions outlined in

Table 5.

To evaluate the performance of this entire process quantitatively, the E2E latency (

) defined as:

The variables used in the formula are listed in

Table 6.

3.6.2. Results

To quantitatively evaluate the responsiveness of the proposed end-to-end (E2E) smart-farm pipeline, we collected 60 samples of complete operational cycles and computed statistical metrics for each latency component. For consistency, all the reported latency measurements were rounded to four decimal places using standard rounding. The empirical results and all components are summarized in

Table 7.

These results indicated that the proposed low-cost E2E pipeline operated with an average end-to-end response time of approximately 0.86 s, from image capture to LED actuation.

4. Dataset and Training

4.1. Data Collection Design

The dataset used to train the proposed model was sourced from an open-access repository provided in part by the Korea Artificial Intelligence (AI) Hub (

https://www.aihub.or.kr/, (accessed on 11 January 2026) data collected in 2025) and in part by the Korea National Institute of Agricultural Sciences (data collected in 2025). All preprocessing script, dataset, and full implementation code for the entire pipeline that including stick-to-module communication and the Leaf-First 2-Stage framework are available at the GitHub repository (URL:

https://github.com/sydney0716/spoiled-pepperleaf-detector-classifier, accessed 2 December 2025). The detailed status of the dataset used for training is listed in

Table 8. In addition, to compensate for the limited availability of normal-condition samples in public datasets, a subset of normal leaf images was directly collected by the authors in open-field environments and incorporated into the training and validation datasets.

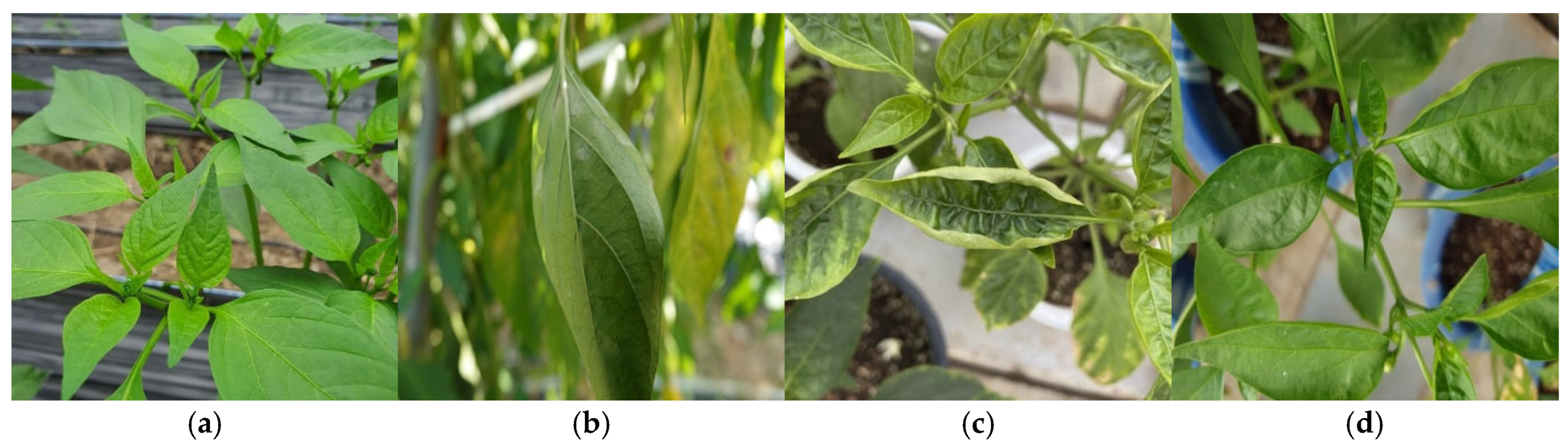

Figure 3 shows an example of data from the image category presented in

Table 8.

4.2. Labeling Pipeline

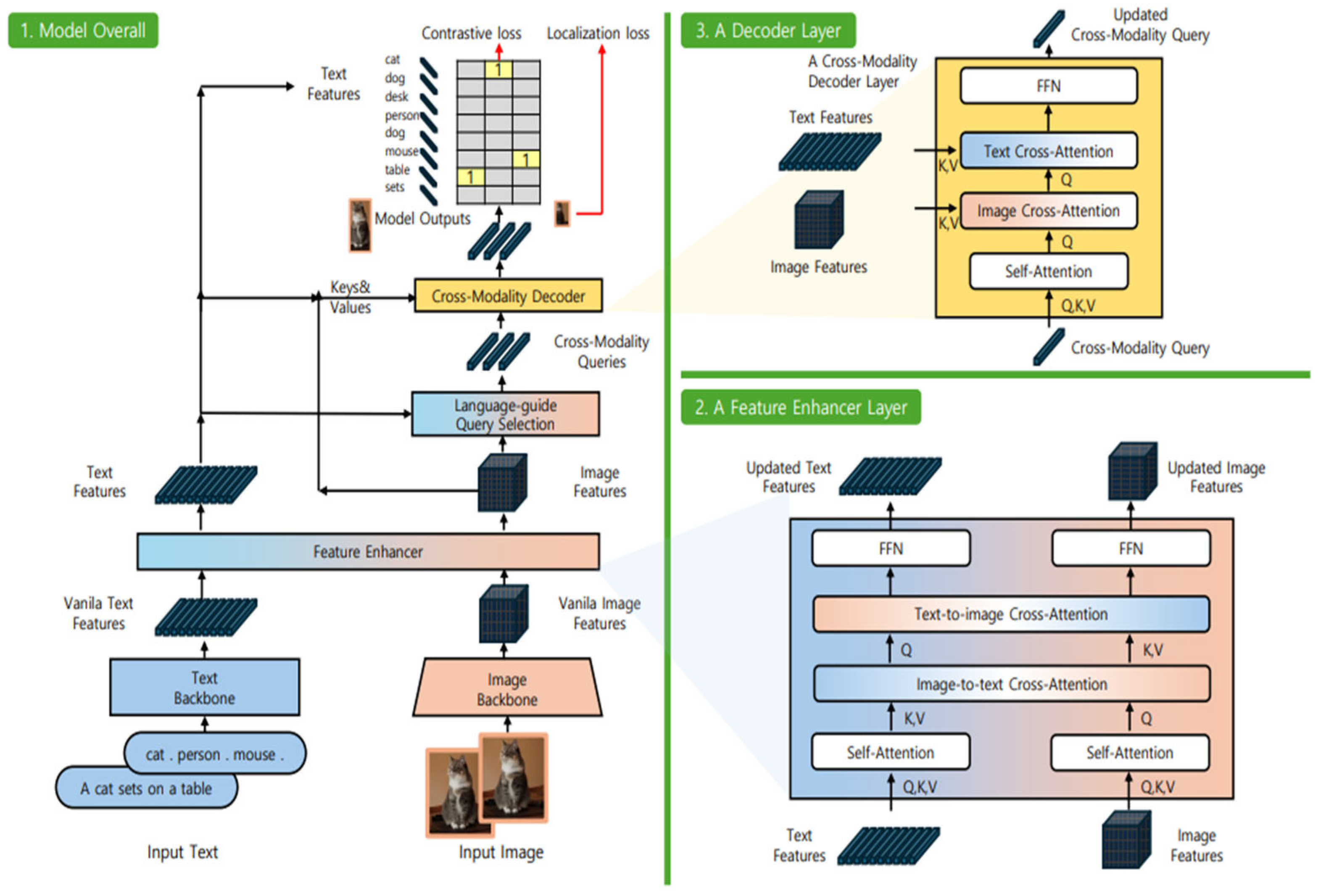

The study utilized Cheongyang chili pepper images from the “Facility Crop Object Images” dataset provided by the AI Hub. However, the original annotations were incomplete, which necessitated the creation of a high-quality custom dataset. To mitigate the inefficiency of fully manual labeling, we implemented a hybrid pipeline that combines auto-labeling with manual review and refinement.

(1) Primary Auto-Labeling and Review: Initial bounding boxes were generated using the Grounding DINO model (

Figure 4), which exploits cross-modality interactions between text prompts and image features to localize target objects for auto-labeling. The prompts were set to provide a caption “a green leaf” and a keyword “leaf.” We prioritized recall to capture the maximum number of objects by setting both box and text thresholds to a low value of 0.15. Errors arising from this low threshold, such as over-detection or overlapping boxes, were refined through manual inspection using Roboflow, an online collaborative labeling service. Of the 356 images, 230 were finalized through the Grounding DINO auto-labeling and manual review processes.

Figure 5 shows example images, an automatically generated label using Grounding DINO and a manually refined annotation created in Roboflow based on auto-labeled results.

(2) Secondary Bootstrap Labeling: To accelerate the processing and enhance the label quality, a bootstrap strategy was implemented. A total of 230 finalized images were used to train the YOLOv11s model. The trained YOLOv11s model then performed secondary auto-labeling on the remaining images, which were subjected to the same manual review process. This iterative approach significantly reduced the total manual labeling burden.

Figure 6 shows an example of secondary labeling results obtained using YOLOv11s.

The final high-quality detection annotations were used to train YOLOv8n, which served as the final first-stage model for leaf detection, as described in

Section 3.4.1.

4.3. Model Training Details

Three models were trained in this study: YOLOv11s for the secondary labeling phase, YOLOv8n for the first stage of the pipeline, and ResNet-18 for the second stage. Each model employed individually optimized hyperparameters for their respective training regimens.

For the YOLOv11s used in the data bootstrapping step, the initial learning rate was set to 0.01, batch size to 8, and weight decay to 5 × 10−4. The training ran for 150 epochs, incorporating an early stopping patience of 50 epochs to stop training when the performance plateaued. This model, consisting of 11.5 M parameters, used a dataset split of 80% for training and 20% for testing.

Subsequently, the First-Stage YOLOv8n for final leaf detection employed the same initial learning rate of 0.01, weight decay of 5 × 10−4, 150 epochs, and 50 patience; however, the batch size was increased to 16 to enhance the training throughput. YOLOv8n was composed of 3.2 M parameters and used an identical 80% training and 20% test data split.

Finally, the Second-Stage ResNet-18 for disease classification adopted ReLU as the activation function, cross entropy as the loss function, and Adam as the optimizer. The learning rate was set to 0.001, batch size to 32, and number of epochs to 150. This classification model also used an 80% training and 20% test dataset split.

4.4. Experimental Scheme

The overall experimental scheme of this study is summarized as follows. First, image data were collected from both public datasets and additional open-field acquisitions to construct the training, validation, and test sets. Stage-1 object detection models (YOLOv8n·v8s and YOLOv11n·v11s) were trained to localize chili pepper leaves, and the detected leaf regions were subsequently cropped and passed to the Stage-2 classification models (ResNet-18 and ResNet-50) for disease diagnosis.

Model training and evaluation were conducted independently for each stage using standardized augmentation and preprocessing pipelines, as described in Sections in the detection and classification setup for YOLOv8n·v8s, YOLOv11n·v11s, and ResNet-18·ResNet-50. Performance was evaluated using detection metrics (mAP) for Stage-1 and classification metrics (accuracy and F1-score) for Stage-2.

Finally, the trained models were deployed on the proposed on-premise Edge AI system, consisting of ESP32-CAM–based sensing nodes and a Raspberry Pi–based processing module. System-level experiments were conducted to evaluate end-to-end latency, communication stability, and autonomous recovery under controlled deployment-oriented conditions, as described in

Section 6.

5. Results Analysis

5.1. Experimental Setup and Model Results Analysis

All the model training and performance verification procedures were conducted in standardized hardware and software environments to ensure reproducibility.

Table 9 provides the detailed hardware and software versions used in this study. All experiments reported in this section were conducted in 2025.

5.2. First-Stage Model Selection

A comparative analysis of the mAP performances of the four investigated YOLO model versions (YOLOv8n, YOLOv8s, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv11s) revealed no statistically significant differences in accuracy

Figure 7. Consequently, when considering the complexity of computation and efficiency of storage space for deployment on an Edge Device, configuring the detection model using the most lightweight variant (YOLOv8n) proved to be the most rational choice.

An analysis of the KPIs during the YOLOv8n training process demonstrated that both the training and validation loss functions exhibited a sharp decline early in training and stabilized after approximately 100 epochs (

Figure 8). The box_loss converged from an initial value of approximately 1.6 to a level of 0.8, indicating that the model successfully learned to accurately estimate the location of objects. cls_loss and dfl_loss exhibited a generally smooth decreasing curve, with a slight upward trend in the latter stages, suggesting that overfitting was effectively suppressed. The validation losses exhibited a similar pattern of decrease and stabilization; val_box_loss converged from 1.3 to 0.9, and val_cls_loss converged from 1.6 to 0.6. This consistency confirms the robust generalization performance of the model across both training and validation data.

The detection metrics, precision and recall curves, converged to approximately 0.82 and 0.84, respectively, maintaining a stable trend after epoch 50. This signifies that both false positives (over-detection) and false negatives (missed detection) concerning the targets (chili leaves and lesions) were effectively suppressed. The core performance metrics, mAP50 and mAP50-95, rapidly increased after epoch 25, converging at approximately 0.90 and 0.68, respectively. This demonstrates that the model achieved very high detection accuracy under the IoU ≥ 0.5 condition and maintained stable performance even under the stricter IoU conditions (from 0.5 to 0.95).

In conclusion, considering the stable convergence of training and validation losses and the sustained high level of key metrics, the proposed YOLOv8n model secured a stable and generalized leaf detection performance without overfitting.

5.3. Second-Stage Model Selection

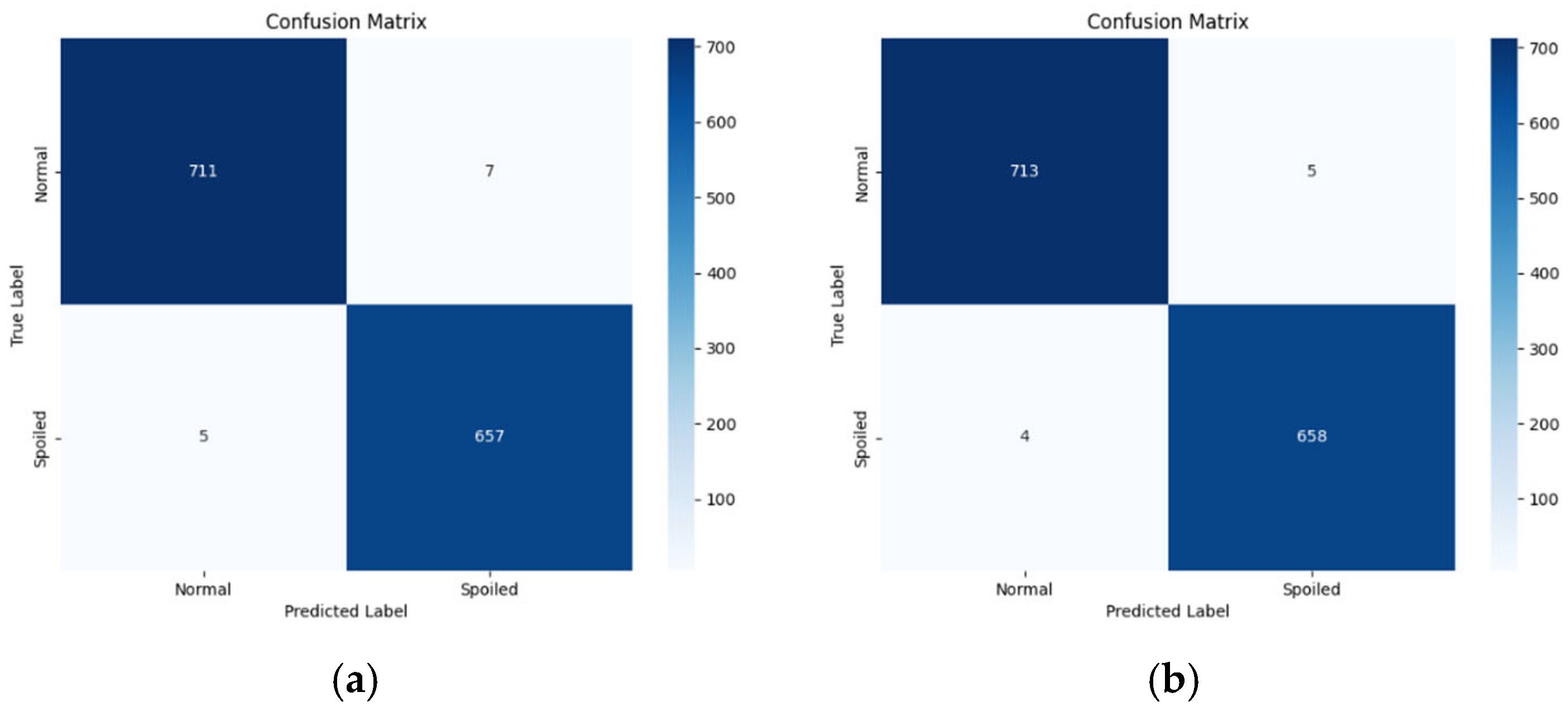

We trained ResNet-18 and ResNet-50 under the same experimental settings and compared their classification performances. Both models achieved high accuracy, and the confusion matrices demonstrated that the false positives and false negatives were highly limited. The quantitative metrics are shown in

Figure 9.

As shown in

Table 10, ResNet-50 demonstrated a slightly better performance and the gap was minimal, which was approximately 0.2–0.3 percentage points. However, the computational and memory costs differed substantially.

ResNet-18 contained 11.7 M parameters and required 1.8 Giga Floating-point Operations per second (GFLOPs, based on 224 × 224 inputs), whereas ResNet-50 contained 25.6 M parameters and 4.1 GFLOPs.

On edge devices, increased computation directly translates into higher latency, power consumption, and thermal load. Therefore, such a marginal accuracy gain does not justify the additional computational cost. Accordingly, adopting the lightweight ResNet-18 as a Stage-2 classifier was the more appropriate choice for this task.

6. Discussion

This study successfully proposed and implemented an on-premise edge IoT architecture for early detection of pests and diseases in agricultural environments. The proposed system comprises a video data collection module using ESP32-CAM, a data management layer that leverages a Flask server and Redis queue, and an AI model integrating YOLOv8n and ResNet18 on a Raspberry Pi. Critically, this architecture establishes an autonomous structure that operates independently within each farm unit without relying on the cloud infrastructure. The experimental results demonstrated that the proposed architecture exhibits excellent resilience and reliably recovers from network disconnections or reboots through Redis state restoration and MQTT auto-reconnection mechanisms.

Furthermore, the AI model successfully achieved a balance between lightweight design and performance, significantly reducing the computational load and power consumption while minimally compromising the mAP performance compared with larger models, such as YOLOv11 or ResNet50. Finally, this study validated the feasibility of a practical, lightweight Edge AI detection system capable of real-time operation in the field. It should be noted that this study does not introduce new learning paradigms or model architectures; rather, its contribution lies in demonstrating how existing lightweight AI models can be effectively integrated into a robust, low-cost, and field-deployable Edge AI system for open-field agriculture.

The proposed edge-based architecture proved to be superior to central server-dependent structures in terms of field applicability and resilience. This aligns with the findings of Miguel et al. (2018), who noted that cloud-centric disease monitoring systems are vulnerable to latency and network failures, which was addressed in this study by introducing independent AI-processing server nodes at the farm unit level [

42]. Moreover, although previous research often focused on image transmission efficiency based on cloud upload, this study focused on onsite data processing using the Redis queue and MQTT [

43]. This approach substantially complements the security vulnerabilities and stability issues inherent in traditional cloud-transfer methods. This design allows real-time disease determination and state recovery, even in environments that are constrained by computing power and bandwidth. In terms of operation under bandwidth constraints, our findings are consistent with those of Bauer and Aschenbruck (2017), who adopted MQTT [

44]. However, we used a two-track strategy, which employs HTTP to transfer large amounts of image data, to prevent the MQTT channel from being delayed by image transmission while ensuring data integrity.

Specifically, an integrated model combining YOLOv8n and ResNet18 confirmed that a practical level of accuracy could be maintained within the performance limits of edge devices. This model achieved an mAP improvement of less than 4%, despite a reduction of approximately 60% in the computational load compared to superior models (YOLOv11 and ResNet50). This result provides experimental evidence that differentiates our study from existing studies, particularly by demonstrating that increased model complexity does not necessarily translate into improved field utility, which is a crucial implication for the design of resource-constrained Edge AI systems.

7. Conclusions

This study presented a resource-constrained, on-premise edge AI system for real-time pest and disease detection in open-field chili pepper cultivation. By integrating a lightweight Leaf-first 2-Stage with low-cost IoT hardware, the proposed system enables autonomous farm-unit-level operation without reliance on cloud infrastructure. Experimental results demonstrated that the system maintains reliable detection performance while reducing computational load by approximately 60% compared to larger models, confirming its suitability for deployment on edge devices. These findings provide clear evidence that practical, real-time crop monitoring can be achieved through system-level integration of existing lightweight models under resource-constrained conditions.

7.1. Limitations and Future Studies

This study successfully developed an on-premise edge IoT architecture capable of operating independently at the farm unit level for early pest and disease detection without relying on a centralized server. The proposed structure secures practical field applicability, not only by lightweighting the AI model but also by designing the entire data collection, analysis, and feedback process to be recoverable within the local environment.

However, the current system, which is centered on a single ESP32-CAM-based image sensor, does not fully account for the complex interplay of diverse environmental factors (temperature, humidity, and soil moisture) present in real-world agriculture. From a system design perspective, these limitations reflect deliberate trade-offs made to ensure robustness, simplicity, and real-time operability under resource-constrained edge environments. Therefore, future studies should establish a system capable of determining the contextual factors of disease occurrence by constructing a multimodal AI model that integrates various types of sensor data.

Furthermore, although the current chili leaf detection model operates efficiently on Raspberry Pi 5 without pruning, the proposed architecture has not yet been validated on crops other than chili pepper. Extending the system to additional crops (e.g., cucumber, rice, and strawberry) would require crop-specific datasets, model retraining, and pruning to ensure stable operation within the resource constraints of edge devices.

In addition, the current study focuses on three representative disease conditions (powdery mildew, PMMoV, and bacterial spot) and does not aim to provide exhaustive disease coverage for real-world crop monitoring. Expanding the disease spectrum and incorporating additional crop types is therefore positioned as an important direction for future work and would primarily involve dataset expansion and model retraining while preserving the same system architecture.

From an application perspective, the proposed system can be readily deployed in small- to medium-scale open-field farms where cloud connectivity is unreliable or economically impractical. The plug-and-play design allows farmers to perform real-time pest and disease monitoring with minimal technical intervention, making it particularly suitable for aging farming populations. In future deployments, the system may also be extended to cooperative farming units, local agricultural monitoring stations, or region-level early warning systems by aggregating multiple farm-unit edge servers. These practical application scenarios highlight the potential of the proposed architecture as a scalable and cost-effective solution for real-world smart farming.

In addition, repeated experiments and formal statistical variability analysis were not conducted in this study, as the primary focus was on deployment-oriented feasibility and system reliability under resource-constrained edge environments. Likewise, a controlled quantitative comparison between edge-based and cloud-based deployments under identical workloads, including latency, cost, and reliability metrics, was beyond the scope of the current work. Incorporating repeated evaluations, statistical confidence reporting, and direct cloud–edge benchmarking is therefore identified as an important direction for future research, particularly for large-scale or long-term agricultural deployments.

7.2. Research Implications

This study addressed the primary reasons for the low adoption rate of 3rd-generation smart farms in open fields. We highlight high cost and the challenges older farmers experience in adopting the technology as key factors. Although existing smart-farm research has largely focused on technical accuracy, this study significantly broadened its scope by addressing methods that efficiently adjust the return on investment of adopting smart-farm technologies. To achieve this, hardware was constructed using low-cost components such as ESP32-CAM and Raspberry Pi 5, and open-source AI models such as YOLOv8n and grounding DINO were used.

Furthermore, for the convenience of users, the architecture was designed to operate autonomously through edge-stage computations, thereby eliminating the need for constant user intervention or cloud reliance. A significant problem with conventional smart-farm equipment is its restriction to specific crops, which is addressed by the architecture developed in this study, thereby offering versatility, as it can be adapted to crops such as cucumber, rice, and strawberry through simple AI model updates. Although the use of public data imposes constraints on extensive iterative experimentation, we believe that future collaboration with local farmers to use onsite data will establish an even greater differentiation from existing research in terms of versatility, cost, and efficiency.

In summary, this study presented a practical on-premise Edge AI system for early pest and disease detection in open-field agriculture. By integrating a lightweight two-stage vision pipeline with low-cost IoT hardware, the proposed architecture achieves real-time operation, robustness against network instability, and ease of deployment at the farm-unit level. The experimental results demonstrate that reliable detection performance can be maintained under resource-constrained conditions, highlighting the feasibility of deploying AI-based crop monitoring systems without reliance on centralized cloud infrastructure. These findings underscore the potential of the proposed system as a practical foundation for next-generation smart farming applications.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, H.C., J.-H.K., J.A. and E.K.; Methodology, H.C., J.-H.K., J.A. and E.K.; Software, H.C. and J.A.; Validation, E.K.; Formal analysis, H.C., J.-H.K. and J.A.; Investigation, H.C., J.-H.K., Y.C. and J.A.; Resources, H.C., Y.C., E.K. and W.H.; Data curation, H.C., J.-H.K. and J.A.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.C., J.-H.K., J.A., Y.C. and E.K.; Writing—review & editing, J.-H.K., Y.C., E.K. and W.H.; Visualization, H.C., J.-H.K. and J.A.; Supervision, E.K. and W.H.; Project administration, E.K.; Funding acquisition, E.K. and W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the research fund of Hanyang University (HY-202500000001616).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences for providing the datasets, valuable guidance and support throughout this research. The authors also extend their appreciation to the AI Hub team for supplying the datasets and resources that made this study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Korea Agro-Fisheries & Food Statistical Service. Agri-Food Statistical Tables. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Available online: https://kass.mafra.go.kr/newkass/kas/sts/sts/stsFrmngList.do (accessed on 11 January 2026).

- Kim, J.; Kim, G.; Yoshitoshi, R.; Tokuda, K. Real-time object detection for edge computing-based agricultural automation: A case study comparing the YOLOX and YOLOv12 architectures and their performance in potato harvesting systems. Sensors 2025, 25, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byeon, J.Y. Status and Improvement Tasks of Smart Agriculture Promotion Projects; National Assembly Budget Office: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Autio, A.; Johansson, T.; Motaroki, L.; Minoia, P.; Pellikka, P. Constraints for adopting climate-smart agricultural practices among smallholder farmers in Southeast Kenya. Agric. Syst. 2021, 194, 103284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B. Multi-crop navigation line extraction based on improved YOLO-v8 and threshold-DBSCAN under complex agricultural environments. Agriculture 2023, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rangel, H.; Morales-Rosales, L.A.; Imperial-Rojo, R.; Roman-Garay, M.A.; Peralta-Peñuñuri, G.E.; Lobato-Báez, M. Analysis of statistical and artificial intelligence algorithms for real-time speed estimation based on vehicle detection with YOLO. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Liu, W. Lightweight pepper disease detection based on improved YOLOv8n. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S. Tomato flower recognition method at the maturity stage based on improved YOLOv8n. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 6th International Conference on Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (PRML), Chongqing, China, 13–16 June 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Padhiary, M. Field to Cloud: Unveiling IoT Triumphs in Agricultural Evolution. In Enhancing Data-Driven Electronics Through IoT; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 391–430. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, A.; Iqbal, M.T. Low-cost ESP32, Raspberry Pi, Node-Red, and MQTT protocol based SCADA system. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International IOT, Electronics and Mechatronics Conference (IEMTRONICS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–12 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Almazroi, A.A. Security mechanism in the internet of things by interacting HTTP and MQTT protocols. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 11th International Conference on Communication Software and Networks (ICCSN), Chongqing, China, 12–15 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, A.R.; Gadge, J. Home server and nas using raspberry PI. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI), Manipal, India, 13–16 September 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 2270–2275. [Google Scholar]

- Lellapati, A.R.; Pidugu, B.K.; Rangari, M.S.R.; Acharya, G.P.; Jayaprakasan, V. Development of advanced alerting system using Arduino interfaced with ESP32 CAM. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Cybernetics, Cognition and Machine Learning Applications (ICCCMLA), Goa, India, 8–9 October 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- PBV, R.R.; Mandapati, V.S.; Pilli, S.L.; Manojna, P.L.; Chandana, T.H.; Hemalatha, V. Home security with IoT and ESP32 CAM-AI thinker module. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Cognitive Robotics and Intelligent Systems (ICC-ROBINS), Coimbatore, India, 17–19 April 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 710–714. [Google Scholar]

- Vimal, M.; Sathyabama, K.; Abishek, A. Design and implementation of an IoT-enabled Rover with ESP32 CAM for object detection, environmental monitoring, and web-based control. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Multi-Agent Systems for Collaborative Intelligence (ICMSCI), Erode, India, 20–22 January 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 457–465. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, J.D.; Zhang, J.X. Development and power characterization of an IoT network for agricultural imaging applications. J. Adv. Inf. Technol. 2021, 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obu, U.; Ambekar, Y.; Dhote, H.; Wadbudhe, S.; Khandelwal, S.; Dongre, S. Crop disease detection using Yolo V5 on Raspberry Pi. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Social Networking (ICPCSN), Salem, India, 19–20 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, S.J.; Cox, S.J. The raspberry Pi: A technology disrupter, and the enabler of dreams. Electronics 2017, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindarat, S.; Wuttidittachotti, P. Smart farm monitoring using Raspberry Pi and Arduino. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Computer, Communications, and Control Technology (I4CT), Kuching, Malaysia, 21–23 April 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 284–288. [Google Scholar]

- Minott, D.; Siddiqui, S.; Haddad, R.J. Benchmarking edge AI platforms: Performance analysis of NVIDIA Jetson and Raspberry Pi 5 with Coral TPU. In SoutheastCon; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1384–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Saqib, M.; Almohamad, T.A.; Mehmood, R.M. A low-cost information monitoring system for smart farming applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouini, O.; Sethom, K.; Namoun, A.; Aljohani, N.; Alanazi, M.H.; Alanazi, M.N. A survey of machine learning in edge computing: Techniques, frameworks, applications, issues, and research directions. Technologies 2024, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S. Analogy of promising wireless technologies on different frequencies: Bluetooth, wifi, and wimax. In Proceedings of the The 2nd International Conference on Wireless Broadband and Ultra Wideband Communications (AusWireless 2007), Sydney, Australia, 27–30 August 2007; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Abinader, F.M., Jr.; de Sousa, V.A., Jr.; Choudhury, S.; Chaves, F.S.; Cavalcante, A.M.; Almeida, E.P.; Vieira, R.D.; Tuomaala, E.; Doppler, K. LTE/Wi-Fi coexistence in 5 GHz ISM spectrum: Issues, solutions and perspectives. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 99, 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokita, M.; Modrzejewski, M.; Rokita, P. PyBrook—A Python framework for processing and visualising real-time data. SoftwareX 2025, 30, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Agrawal, A.; Prakash, N.; Goyal, P. Smart saline level monitoring system using ESP32 and MQTT-S. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on e-Health Networking, Applications and Services (Healthcom), Ostrava, Czech Republic, 17–20 September 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.H.; Wu, F.C.; Lin, H.W. Design and implementation of ESP32-based edge computing for object detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadient, P.; Nierstrasz, O.; Ghafari, M. Security header fields in http clients. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 21st International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security (QRS), Haikou, China, 6–10 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino, J. Implementation of a JPEG packetization code for wireless sensor networks in animal monitoring applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE ANDESCON, Barranquilla, Colombia, 16–19 November 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Calagna, A.; Ravera, S.; Chiasserini, C.F. Enabling efficient collection and usage of network performance metrics at the edge. Comput. Netw. 2025, 262, 111158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgur, U.; Nair, H.T.; Sundararajan, A.; Akkaya, K.; Sarwat, A.I. An efficient MQTT framework for control and protection of networked cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–11 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Vania, E.; Sanjaya, R.; Pamudji, A.K. Message queuing telemetry transport utilization for Internet of Things-based document locker management. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer and Information Technology (ICEECIT), Jember, Indonesia, 22–23 November 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shvaika, D.; Shvaika, A.; Artemchuk, V. MQTT broker architectural enhancements for high-performance P2P messaging: TBMQ scalability and reliability in distributed IoT systems. IoT 2025, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksamana, A.D.P.; Fakhrurroja, H.; Pramesti, D. Developing a labeled dataset for chili plant health monitoring: A multispectral image segmentation approach with YOLOv8. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and its Applications (IC3INA), Bandung, Indonesia, 9–10 October 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Bao, Y. Small target detection algorithm for UAV aerial photography based on improved YOLO V8n. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Data-driven Optimization of Complex Systems (DOCS), Hangzhou, China, 16–18 August 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 870–875. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Hu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, G. Multi-plant disease identification based on lightweight ResNet18 model. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Sun, B.; Lu, X.; Jia, S. Geographic semantic network for cross-view image geo-localization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, S.H. Performance comparison of CNN models using gradient flow analysis. Informatics 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; He, Y. An improved ResNet based on the adjustable shortcut connections. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 18967–18974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Shen, C.; Van Den Hengel, A. Wider or deeper: Revisiting the ResNet model for visual recognition. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 90, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surantha, N.; Sutisna, N. Key considerations for real-time object recognition on edge computing devices. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Izquierdo, M.A.; Santa, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Martínez, V.; Skarmeta, A.F. Smart farming IoT platform based on edge and cloud computing. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 177, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, D.; Stamenković, Z.; Đorđević, B.; Ranđić, S. Image processing for smart agriculture applications using cloud-fog computing. Sensors 2024, 24, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.; Aschenbruck, N. Measuring and adapting MQTT in cellular networks for collaborative smart farming. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 42nd Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN), Singapore, 9–12 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 294–302. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

System architecture.

Figure 1.

System architecture.

Figure 2.

YOLOv8 architecture.

Figure 2.

YOLOv8 architecture.

Figure 3.

Training data inspection ((a) Facility-grown crop 1, (b) Powdery mildew 1, (c) Mild mottle virus 1, (d) Bacterial spot 1).

Figure 3.

Training data inspection ((a) Facility-grown crop 1, (b) Powdery mildew 1, (c) Mild mottle virus 1, (d) Bacterial spot 1).

Figure 4.

Grounding Deep Intermediate-level Non-contrastive features with Output (DINO) framework used for primary auto-labeling.

Figure 4.

Grounding Deep Intermediate-level Non-contrastive features with Output (DINO) framework used for primary auto-labeling.

Figure 5.

Auto-labeling results ((a) AI-hub example, (b) Grounding DINO label, (c) Manual review in Roboflow).

Figure 5.

Auto-labeling results ((a) AI-hub example, (b) Grounding DINO label, (c) Manual review in Roboflow).

Figure 6.

Secondary bootstrap labeling results ((a) YOLOv11s example 1, (b) YOLOv11s example 2, (c) YOLOv11s example 3).

Figure 6.

Secondary bootstrap labeling results ((a) YOLOv11s example 1, (b) YOLOv11s example 2, (c) YOLOv11s example 3).

Figure 7.

Model-wise comparison of mAP.

Figure 7.

Model-wise comparison of mAP.

Figure 8.

Y Training, validation, and detection performance metrics of the YOLOv8n model across epochs. (The first row shows training loss curves, the second row presents precision, recall, and validation box loss, and the third-row reports validation classification losses and detection performance metrics (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95)).

Figure 8.

Y Training, validation, and detection performance metrics of the YOLOv8n model across epochs. (The first row shows training loss curves, the second row presents precision, recall, and validation box loss, and the third-row reports validation classification losses and detection performance metrics (mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95)).

Figure 9.

YOLOv8n model performance metrics ((a) Resnet-18 confusion matrix, (b) Resnet-50 confusion matrix).

Figure 9.

YOLOv8n model performance metrics ((a) Resnet-18 confusion matrix, (b) Resnet-50 confusion matrix).

Table 1.

Summary of Redis features.

Table 1.

Summary of Redis features.

| Category | Description | Expectation |

|---|

Asynchronous

decoupling | Separates HTTP image upload from AI inference to mitigate differences in processing speed | Prevents transmission delays on ESP32 devices and improves overall throughput |

| Queue buffering | Stores incoming image data in memory sequentially and waits until a worker becomes available | Maintains load balancing between data transmission and processing |

| Fault tolerance | Enables safe reprocessing without data loss even if the AI module or network experiences failures | Enhances system reliability |

| State management | Stores each ESP-32’s ALERT/NEARBY/CLEAR status using Redis key-value pairs | Allows state recovery when MQTT reconnects |

Table 2.

Summary of MQTT topics.

Table 2.

Summary of MQTT topics.

| Topic | Description |

|---|

| farm/capture | Image capture request |

| farm/alert/<esp_id> | Pest/disease detection |

| farm/nearby/<esp_id> | Nearby alert |

| farm/clear/<esp_id> | Normal state |

Table 3.

LED status indicators.

Table 3.

LED status indicators.

| LED Color | Internal State (Topic) | Description |

|---|

| Red | ALERT | Confirmed pest/disease detection |

| Orange | NEARBY | Alert triggered in nearby nodes (±2 nodes) |

| Green | CLEAR | Normal operating condition |

| Yellow | Error or Retry | HTTP upload failure or network instability |

Table 4.

Detection augmentation parameters.

Table 4.

Detection augmentation parameters.

| Augmentation Item | Parameter/Value |

|---|

| HSV jitter | H = 0.015, s = 0.7, v = 0.4 |

| Translate | 0.1 |

| Scale | 0.5 |

| Horizontal flip | p = 0.5 |

| Mosaic | O (For 1–10 epoch) |

| Auto augment | randaugment |

| Random erasing | 0.4 |

Table 5.

Classification augmentation parameters.

Table 5.

Classification augmentation parameters.

| Augmentation Item | Parameter/Value |

|---|

| Resize | 224 × 224 |

| Flip | p = 0.5 |

| Rotation | ±10° |

| Color | b/c/s = 0.2, hue = 0.1 |

| ToTensor | O |

| Normalize | Mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406]

Std = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225] |

Table 6.

E2E Latency variable description.

Table 6.

E2E Latency variable description.

| Component | Description |

|---|

| Time required for the camera sensor to capture an image |

| Time required for the ESP32 to transmit an image to the module |

| Time required for the module to run AI inference |

| Time required to interpret the inference result and generate a signal |

| Reaction time until the LED actually turns on |

| Total latency |

Table 7.

E2E latency results (Unit: mms).

Table 7.

E2E latency results (Unit: mms).

| Component | Avg | SD | Min | Max |

|---|

| 0.181 | 0.019 | 0.138 | 0.276 |

| 132.183 | 49.53 | 69 | 314 |

| 728.891 | 332.741 | 332.33 | 1804.17 |

| 0.685 | 0.266 | 0.48 | 1.99 |

| 0.101 | 0.011 | 0.094 | 0.131 |

| 862.041 | | | |

Table 8.

Training data inspection.

Table 8.

Training data inspection.

| Image Category | Data Volume | Purpose of Use |

|---|

| Facility-grown crop specimens | 400 images | Used for leaf detection across entire chili pepper plants |

| Powdery mildew (Leveillula taurica) | 1027 images | Used for training disease diagnosis models for open-field crops |

| Pepper mild mottle virus (PMMoV) | 2653 images | Used for training disease diagnosis models for facility-grown crops |

| Bacterial spot (Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria) | 836 images | Used for training disease diagnosis models for facility-grown crops |

Table 9.

Experimental setup environment.

Table 9.

Experimental setup environment.

| Software and Hardware | Version or Model |

|---|

| Operating system | Ubuntu 22.04 |

| CPU | AMD Ryzen 5 5600X |

| GPU | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3070 |

| Display memory | Display memory 8GB |

| CUDA | 12.8 |

| CUDNN | 9.0.7 |

| Ultralytics | 2.7.1 |

| Scikit-learn | 1.7.1 |

| Python | 3.11.13 |

| Visual Studio Code | 1.96 |

Table 10.

Precision and recall f1-score for ResNet-18 and Resnet-50.

Table 10.

Precision and recall f1-score for ResNet-18 and Resnet-50.

| Cat. | ResNet-18 | ResNet-50 |

|---|

Precision

(%) | Normal | 99.3 | 99.4 |

| Spoiled | 98.9 | 99.2 |

Recall

(%) | Normal | 99.0 | 99.3 |

| Spoiled | 99.2 | 99.4 |

F1-score

(%) | Normal | 99.1 | 99.3 |

| Spoiled | 99.1 | 99.3 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |