Case in Taiwan Demonstrates How Corporate Demand Converts Payments for Ecosystem Services into Long-Run Incentives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Conceptual Evolution of PES: From Market Transactions to Broad Incentives

2.2. The Duality of Participation Motivation: Economic Incentives vs. Intrinsic Values

2.3. Systematic Challenges in Practical Implementation

3. Materials and Methods

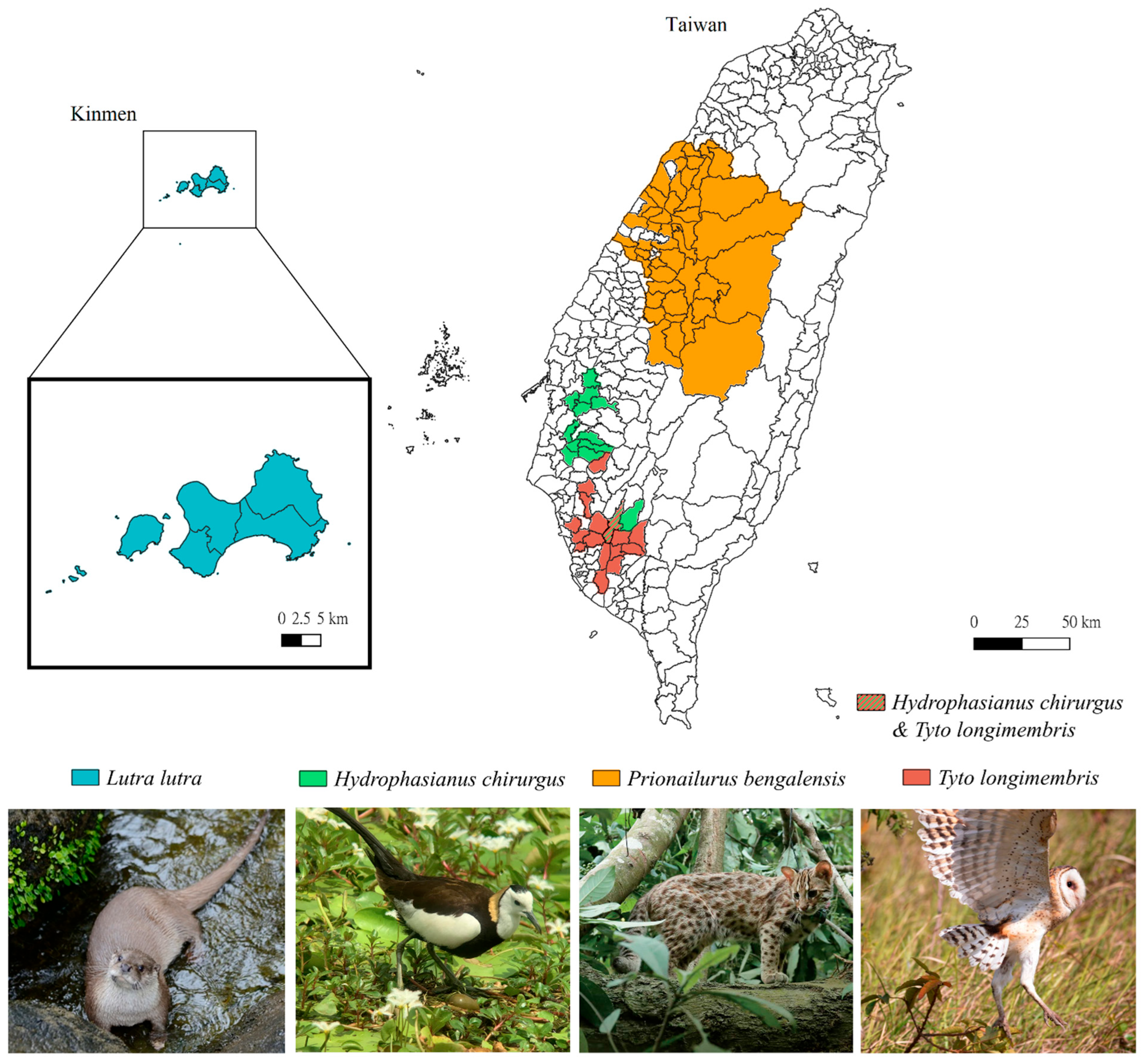

3.1. Study Site

3.2. Method

3.3. Interview Target

3.4. Questionnaire Design

- (1)

- Threat factors: Based on your observations, what are the main threats to the survival of endangered species in the local area?

- (2)

- Eco-friendly Farming: In your opinion, which eco-friendly farming practices or types of plants can effectively promote the survival and reproduction of endangered species?

- (3)

- Challenges in conservation: What do you think is the biggest challenge or obstacle in endangered species conservation efforts?

- (4)

- Impact of PES programs: What impact does the Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) program have on the lives and livelihoods of local communities or farmers?

- (5)

- Relationship between agriculture and conservation: Does endangered species conservation have any direct or indirect effects on agricultural operations and production? If so, what are they?

- (6)

- Incentives for participation: Would increasing incentives or raising the amount offered in the PES program encourage more people to participate in such conservation efforts?

- (7)

- Suggestions and improvements: Do you have any suggestions or ideas for improving the current PES programs or conservation initiatives?

4. Results

4.1. The Impact of Economic Development and Agricultural Expansion on Species

4.2. Effectiveness of the Three-Year PES Policy

4.3. Policy Components Requiring Improvement

4.4. Who Is More Likely to Participate in the PES Program

4.5. Changes in Farmers’ Attitudes and Motivations

4.6. Persistent Challenges in Conserving Protected Species

4.7. Additional Benefits Generated by the PES Policy

4.8. Study Results Concerning Endangered Species

4.8.1. Prionailurus bengalensis

4.8.2. Lutra lutra

4.8.3. Tyto longimembris

4.8.4. Hydrophasianus chirurgus

5. Discussion

5.1. Behavioral Drivers and Socio-Psychological Transformation in Taiwan’s PES Programs

5.2. Impact on the Natural Environment

5.3. Community Cohesion, Private Sector Engagement, and Policy Influence in PES Programs

5.4. A Core Principle of PES Programs Is Conditionality

5.5. High-Quality PES Programs Exhibit Additionality

5.6. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WWF (World Wildlife Fund). 2024 Living Planet Report—A System in Peril; WWF International: Gland, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, B.M.; McBeath, J.; Wang, B. Implementation deficits in endangered species protection: Comparing the U.S. and Chinese approaches. In Imperiled: The Encyclopedia of Conservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD (Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity). Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Meeting Part II, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–19 December 2022; Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2026).

- Benton, T.G.; Carling, B.; Helen, H.; Roshan, P.; Laura, W. Food system impacts on biodiversity loss. In Energy, Environment and Resources Programme; Chatham House: London, UK, 2021; Volume 7, Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/2021-02-03-food-system-biodiversity-loss-benton-et-al_0.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B.; et al. Global effects of land use on local terrestrial biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D.; Alexander, S. Agriculture and biodiversity: A review. Biodiversity 2017, 18, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, L.; Romero-Muñoz, A.; Polaina, E.; Estes, L.; Kreft, H.; Kuemmerle, T. Biodiversity at risk under future cropland expansion and intensification. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F.; Wyckhuys, K.A.G. Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 232, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Gossner, M.M.; Simons, N.K.; Blüthgen, N.; Müller, J.; Ambarlı, D.; Ammer, C.; Bauhus, J.; Fischer, M.; Habel, J.C.; et al. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature 2019, 574, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendrill, F.; Gardner, T.A.; Meyfroidt, P.; Persson, U.M.; Adams, J.; Azevedo, T.; Bastos Lima, M.G.; Baumann, M.; Curtis, P.G.; De Sy, V.; et al. Disentangling the numbers behind agriculture-driven tropical deforestation. Science 2022, 377, eabm9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, P.; Zimmert, F.; Dux, D.; Blaser, S.; Gilgen, A. Agricultural production and biodiversity conservation: A typology of Swiss farmers’ land use patterns. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). Agriculture and Conservation; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 75, Available online: https://iucn.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/iucn-mtr-final-report_0.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2024).

- Muradian, R.; Corbera, E.; Pascual, U.; Kosoy, N.; May, P. Reconciling theory and practice: An alternative conceptual framework for understanding payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.P.; Perrings, C.; Chapin, F.S., III; Polasky, S.; Smith, V.K.; Tilman, D.; Turner, B.L. Paying for ecosystem services—Promise and peril. Science 2011, 334, 603–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomers, S.; Matzdorf, B. Payments for ecosystem services: A review and comparison of developing and industrialized countries. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Brouwer, R.; Engel, S.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Muradian, R.; Pascual, U.; Pinto, R. From principles to practice in paying for nature’s services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Cyr, L.D.; Védrine, L.; Legras, S.; Le Gallo, J.; Bellassen, V. Drivers of PES effectiveness: Some evidence from a quantitative meta-analysis. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 210, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, X.; Wang, Y.; Leung, K.M.Y. The impact of payment for ecosystem service schemes on participants’ motivation: A global assessment. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 65, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Erik, L.; David, A.N. Payments and penalties in ecosystem services programs. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2024, 126, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, A.; Ulibarri-Svancara, C.; Vanasco, W.; Ruyle, G.; Bonar, S.; López-Hoffman, L. Opportunities and barriers for endangered species conservation using payments for ecosystem services. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 232, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry and Nature Conservation Agency, Taiwan. Payments for Ecosystem Services for Endangered Species and Important Habitats. 2021. Available online: https://www.forest.gov.tw/0004614 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Clancy, N.G. Protecting endangered species in the USA requires both public and private land conservation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorice, M.G.; Haider, W.; Conner, J.R.; Ditton, R.B. Incentive structure of and private landowner participation in an endangered species conservation program. Conserv. Biol. 2011, 25, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woinarski, J.C.Z.; Burbridge, A.B.; Harrison, P.L. Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: Decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 11, 4531–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, E.L.; Mellish, S.; McLeod, E.M.; Sanders, B.; Ryan, J.C. Can we save Australia’s endangered wildlife by increasing species recognition? Nat. Conserv. 2022, 69, 126257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Scaling Up Biodiversity-Positive Incentives: Delivering on Target 18 of the Global Biodiversity Framework. 2025. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1787/19b859ce-en (accessed on 20 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. 1983. Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/text.php (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Daniel, C.D. Evaluating U.S. endangered species legislation: The Endangered Species Act as an international example. William Mary Environ. Law Policy Rev. 1999, 23, 683–704. [Google Scholar]

- Kreye, M.M.; Pienaar, E.F. A critical review of efforts to protect Florida panther habitat on private lands. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, L. Collaborative adaptive management: Challenges and opportunities. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, B.K.; Kousky, C.; Sims, K.R.E. Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentive-based mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9465–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras Gamarra, M.J.; Toombs, T.P. Thirty years of species conservation banking in the U.S.: Comparing policy to practice. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 214, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the concept of payments for environmental services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. The efficiency of payments for environmental services in tropical conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S. The devil in the detail: A practical guide on designing payments for environmental services. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 9, 131–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Rival, L. Between markets and hierarchies: The challenge of governing ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, A.M.; Svancara, C.; Vanasco, W.; Ruyle, G.; López-Hoffman, L. The land ethic of ranchers: A core value despite divergent views of government. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 70, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selinske, M.J.; Coetzee, J.; Purnell, K.; Knight, A.T. Understanding the motivations, satisfaction, and retention of landowners in private land conservation programs. Conserv. Lett. 2015, 8, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Donlan, C.J. A human-centered framework for innovation in conservation incentive programs. Ambio 2015, 44, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorice, M.G. Retooling the traditional approach to studying the belief–attitude relationship: Explaining landowner buy-in to incentive programs. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langpap, C. Conservation of endangered species: Can incentives work for private landowners? Ecol. Econ. 2006, 57, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, Ö. Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social–ecological systems. Science 2017, 357, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, D.N.; Blumentrath, S.; Rusch, G. Policyscape- A spatially explicit evaluation of voluntary conservation in a policy mix for biodiversity conservation in Norway. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Arsel, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Adaman, F.; Aguilar, B.; Agarwal, B. Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, L. Interviews: In-depth, semistructured. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Naz, N.; Gulab, F.; Aslam, N. Development of qualitative semi-structured interview guide for case study research. Compet. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2022, 3, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colaizzi, P.F. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Existential-Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology 48–71; Valle, R.S., King, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1986, 8, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Pei, K.J.C.; Chen, C.C.; Chuang, M.-F. Roadkill and domestic dog predation as major mortality sources for leopard cats (Prionailurus bengalensis) in agricultural landscapes of Taiwan. J. Wildl. Manag. 2022, 86, e22254. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.F.; Wang, C.T.; Pei, K.J.C. Agroecological practices, biodiversity, and coexistence potential for Taiwan’s small carnivores: Evidence from eco-friendly farmland units. Biol. Conserv. 2023, 283, 110355. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.K.; Petrovan, S.O.; Sutherland, W.J. Roads and reservoirs as drivers of habitat fragmentation for otters (Lutra lutra): A global evidence review. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 2015–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, I.; Shore, R.F.; Wyllie, I.; Birks, D.S.; Dale, L. Secondary poisoning of raptors by rodenticides: Trophic transfer pathways and population-level implications. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 1171–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-M.; Wang, Y.-C. Decline of floating-leaf wetland systems under agricultural and climate pressures: Implications for jacana habitat persistence in East and Southeast Asia. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 29, 653–670. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, P.W.; Mica, E.; Joseph, S.; Rebecca, S.; Nilmini, S. Using in-home displays to provide smart meter feedback about household electricity consumption: A randomized control trial comparing kilowatts, cost, and social norms. Energy 2015, 90, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, I.; Paul, C.S. Examining the decision-making processes behind household energy investments: A review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 10, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.T.; Roongtawanreongsri, S.; Ho, T.Q.; Tran, P.H.N. Can payments for forest environmental services help improve income and attitudes toward forest conservation? Household-level evaluation in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 132, 102578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ola, O.; Menapace, L.; Benjamin, E.; Lang, H. Determinants of the environmental conservation and poverty alleviation objectives of payments for ecosystem services (PES) programs. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 35, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinton, S.M. Payments for ecosystem services where spatial configuration and scale matter. Encycl. Energy Nat. Resour. Environ. Econ. Second. Ed. 2025, 3, 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Klain, S.; Olmsted, P.; Chan, K.; Satterfield, T. Relational values resonate broadly and differently than intrinsic or instrumental values, or the new ecological paradigm. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.; Haider, L.J.; Masterson, V.; Enqvist, J.; Svedin, U.; Tengö, M. Stewardship, care and relational values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 35, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diver, S.; Vaughan, M.; Baker-Médard, M.; Lukacs, H. Recognizing “reciprocal relations” to restore community access to land and water. Int. J. Commons 2019, 13, 400–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillos, T.; Patrick, B.; David, C.; Nigel, A.; Julia, P.G.J. In-kind conservation payments crowd in environmental values and increase support for government intervention: A randomized trial in Bolivia. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 166, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maca-Millán, S.; Paola, A.; Lina, R. Payment for ecosystem services and motivational crowding: Experimental insights regarding the integration of plural values via non-monetary incentives. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, L.; Doole, G.J. Drivers of landholder participation in tender programs for Australian biodiversity conservation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 33, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, K.M.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. Psychological drivers of willingness to pay for urban forest ecosystem services: An extended Theory of Planned Behavior approach. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 47, e02567. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, B.K.; Jayachandran, S. Self-selection into payments for ecosystem services programs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5326–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.; Steg, L.; Gatersleben, B. Biospheric values and conservation behavior: Insights for PES scheme design. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.Y.; Yap, J.L.; Lin, C.C. Balancing conservation and development: A review of navigating malaysian forest policies and initiatives. Int. For. Rev. 2024, 26, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, W.; Zhang, L. Determinants of herders’ participation in China’s grassland PES policy: The role of socioeconomic and institutional factors. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2022, 8, 2052762. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak, S.K.; Wunder, S.; Ferraro, P.J. Show me the money: Do payments supply environmental services in developing countries? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2010, 4, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asah, S.T.; Guerry, A.D.; Blahna, D.J.; Lawler, J.J. Perception, acquisition and use of ecosystem services: Human behavior, and ecosystem management and policy implications. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Lu, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhou, T.; Deng, J.; Kong, L.; Yang, W. Integrated assessment of a payment for ecosystem services program in China from the effectiveness, efficiency and equity perspective. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 56, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcove, D.S.; Lee, J. Using economic and regulatory incentives to restore endangered species: Lessons learned from three new programs. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadykalo, A.N.; Buxton, R.T.; Morrison, P.; Anderson, C.M.; Bickerton, H.; Francis, C.M.; Smith, A.C.; Fahrig, L. Bridging research and practice in conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J.; Bennett, G.; Carroll, N.; Goldstein, A.; Jenkins, M. The global status and trends of payments for ecosystem services. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bähr, T.; Bernal-Escobar, A.; Wollni, M. Can payments-for-ecosystem-services change social norms? Ecol. Econ. 2025, 228, 108468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batáry, P.; Lynn, V.; Dicks, D.K.; William, J.S. The role of agri-environment schemes in conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-A.T.; Vodden, K.; Wu, J.; Bullock, R.; Sabau, G. Payments for ecosystem services programs: A global review of contributions towards sustainability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e22361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Tort, S.; Jayachandran, S.; Saavedra, S. Redesigning payments for ecosystem services to increase cost-effectiveness. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoud, H.; Costedoat, S.; Izquierdo-Tort, S.; Moros, L.; Villamayor-Tomás, S.; Castillo-Santiago, M.Á.; Wunder, S.; Corbera, E. Sustained participation in a Payments for Ecosystem Services program reduces deforestation in a Mexican agricultural frontier. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, C.; Hernandez, S.; Le Moal, M.; Gruau, G. Payment for Ecosystem Services: An Efficient Approach to Reduce Eutrophication? Water 2023, 15, 3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. The Conditionality of Wetland Ecological Compensation: Supervision Analysis Based on Game Theory. Water 2023, 15, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts. Cent. Int. For. Res. 2005, 42, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg, E. Additionality in Payment for Ecosystem Services Programs: Agricultural Conservation Subsidies in Maryland. Land Econ. 2022, 98, 558–573. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzatesta, M.; Newburn, D.A.; Woodward, R.T. Additionality and the Adoption of Farm Conservation Practices. Land Econ. 2013, 89, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, R.; Atwood, J.W.; Christian, L. Conservation program design: Targeting, performance, and potential efficiency. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2018, 40, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, S.; de Laat, J.; Lambin, E.F.; Stanton, C.Y.; Audy, R.; Thomas, N.E. Cash for carbon: A randomized trial of payments for ecosystem services to reduce deforestation. Science 2017, 357, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Species | Eco-Friendly Farming | Self-Reporting | Patrolling and Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prionailurus bengalensis | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used, and the standards for pesticide residue safety are met. | 1. In cases of species invading poultry farms, an initial reward of NT $3000 will be granted without endangering the survival of the target species. 2. An additional NT $10,000 reward will be issued upon capturing images of the invasive species using an automatic camera. | 1. Community development associations or local civil organizations that establish patrol teams to assist in promoting endangered species conservation efforts will be eligible for an annual reward of up to NT $60,000. 2. Captured images of a species are eligible for a reward of up to NT $50,000 per instance, limited to twice a year. Each submission must be spaced at least three months apart. |

| Lutra lutra | 1. No subsidies. | 1. In cases of species invading poultry farms, an initial reward of NT $3000 will be granted without endangering the survival of the target species. 2. An additional NT $10,000 reward will be issued upon capturing images of the invasive species using an automatic camera. | 1. Community development associations or local civil organizations that establish patrol teams to assist in promoting endangered species conservation efforts will be eligible for an annual reward of up to NT $60,000. 2. Captured images of a species are eligible for a reward of up to NT $50,000 per instance, limited to twice a year. Each submission must be spaced at least three months apart. |

| Tyto longimembris | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used, and the standards for pesticide residue safety are met. 2. Those who assist in setting up and maintaining perching racks will receive a reward of NT $3000. If images of raptors are captured using automatic cameras within a three-month period, an additional NT $10,000 reward will be granted. | 1. No subsidies. | 1. Community development associations or local civil organizations that establish patrol teams to assist in promoting endangered species conservation efforts will be eligible for an annual reward of up to NT $60,000. |

| Hydrophasianus chirurgus | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used, and the standards for pesticide residue safety are met. 2. The farmland is maintained in a paddy field condition. | 1. For those who identify breeding nests and successfully hatch chicks, a reward of NT $3000 will be granted per nest. | 2. Community development associations or local civil organizations that establish patrol teams to assist in promoting endangered species conservation efforts will be eligible for an annual reward of up to NT $60,000. |

| No. | Age (Years) | Sex | Survey Location | Occupation | Endangered Species | Years of Experience | Measures and Efforts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | female | Miaoli County | Chicken farmers | Prionailurus bengalensis | 3 | 1. Renovating a chicken coop. 2. Installing surveillance cameras. |

| 2 | 65 | male | 3 | ||||

| 3 | 62 | male | Taichung City | Banana farmers | 3 | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used. 2. Agricultural management using grass-based cultivation techniques. | |

| 4 | 59 | female | 3 | ||||

| 5 | 58 | female | Nantou County | 5 | |||

| 6 | 59 | male | 5 | ||||

| 7 | 42 | female | Wildlife conservation organization | 8 | 1. Community advocacy for conservation measures 2. Tracking changes in population distribution and numbers. | ||

| 8 | 67 | male | Kinmen County | Community resident | Lutra lutra | 3 | 1. Installing road signs and surveillance cameras. 2. Tracking changes in population distribution and numbers. |

| 9 | 59 | male | 3 | ||||

| 10 | 42 | female | 3 | ||||

| 11 | 33 | female | 3 | ||||

| 12 | 50 | male | 3 | ||||

| 13 | 47 | female | 3 | ||||

| 14 | 30 | female | Wildlife conservation organization | 5 | 1. Community advocacy for conservation measures | ||

| 15 | 50 | female | Tainan City | Community resident | Tyto longimembris | 3 | 1. Installing surveillance cameras. 2. Tracking changes in population distribution and numbers. |

| 16 | 45 | male | 3 | ||||

| 17 | 66 | male | Water caltrop farmer | Hydrophasianus chirurgus | 6 | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used. | |

| 18 | 65 | female | 7 | ||||

| 19 | 64 | female | 6 | ||||

| 20 | 69 | male | Kaohsiung City | Retiree | Tyto longimembris | 4 | 1. Organizing the environment and removing sensitive plants (Mimosa diplotricha). |

| 21 | 59 | male | Pineapple farmer | 3 | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used. 2. Setting up observation perches in farmlands. | ||

| 22 | 61 | male | 3 | ||||

| 23 | 58 | male | 3 | ||||

| 24 | 50 | male | Wildlife conservation organization | 5 | 1. Community advocacy for conservation measures | ||

| 25 | 50 | female | Water lily farmer | Hydrophasianus chirurgus | 3 | 1. No herbicides, rodenticides, toxic baits, or non-eco-friendly pest control nets are used. 2. Postpone the harvest time. | |

| 26 | 49 | female | 3 | ||||

| 27 | 55 | male | 3 | ||||

| 28 | 60 | female | Wildlife conservation organization | 10 | 1. Community advocacy for conservation measures 2. Tracking changes in population distribution and numbers. |

| Themes | Theme Clusters |

|---|---|

| 1. The impact of economic development and agricultural expansion on species. | 1-1 Local economic development and infrastructure projects. 1-2 The ecological impact of agricultural production. |

| 2. Effectiveness of the three-year PES policy. | 2-1 Function of surveillance cameras. 2-2 The policy can increase farmers’ income or compensate for losses. 2-3 More opportunities for interaction between wildlife conservation groups and farmers. 2-4 Effectiveness of ecological corridors or perch installations. 2-5 Maintenance or increase in species population. 2-6 Benefits of eco-friendly farming. |

| 3. Policy components requiring improvement. | 3-1 Effectiveness of ecological corridor or perch installations 3-2 Strengthening education and outreach on species conservation 3-3 Improving contact points and administrative procedures 3-4 Removal of harmful invasive species 3-5 Increasing collaboration with academic institutions for research |

| 4. Who is more likely to participate in the PES program? | 4-1 Residents or farmers with relatively higher incomes are more willing to participate. 4-2 Beneficial for agricultural product marketing and brand development. 4-3 Contribution to community building and image enhancement. 4-4 Residents or farmers with a deep emotional attachment to the land are more inclined to join. |

| 5. Changes in farmers’ attitudes and motivations. | 5-1 Increasing public concern for species conservation. 5-2 Benefits for agricultural product marketing and brand development. 5-3 Contribution to community building and positive image formation. 5-4 Sense of accomplishment from successful species restoration. 5-5 Successful experiences of other farmers help alleviate doubts and concerns |

| 6. Persistent challenges in conserving protected species. | 6-1 Aging population in rural communities. 6-2 Local economic development and infrastructure expansion. 6-3 Reluctance to change traditional farming practices. 6-4 Impacts of climate change. 6-5 Uncertainty regarding continued government support. 6-6 Increasing population of stray dogs. 6-7 Inability to completely prevent roadkill incidents. 6-8 Difficulty in tracking species population numbers. |

| 7. Additional benefits generated by the PES policy. | 7-1 Benefits for agricultural product marketing and brand development. 7-2 Contribution to community building and positive image formation. 7-3 Enables feedback to the government for policy improvement 7-4 Increasing public concern for species conservation. 7-5 Attracts support from the private sector |

| Development | Phase I Community and Farmer Participation | Phase II Effectiveness of Conservation Actions | Phase III Additionality of Conservation Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | 1. Academic institutions or wildlife conservation organizations promote the PES program. 2. Farmers with better financial conditions adopt eco-friendly farming practices first, and then promote them to other farmers. | 1. Install surveillance cameras to monitor ecological changes in conservation species. 2. Community organizations in different areas also exchange experiences on conserving and restoring endangered species. | 1. Private enterprises participate in conservation efforts. 2. Utilize information and network technology to enhance public awareness of conservation species. |

| Challenges | 1. Farmers lack professional knowledge and experience in conservation. 2. Concerns arise about whether conservation measures will impact agricultural production. | 1. Whether conservation measures are truly effective and whether the population of the species has genuinely increased. 2. Identifying other factors that threaten habitats. | 1. How to sustain conservation outcomes. 2. How to involve more people in conservation efforts. |

| Effects | 1. Farmers’ losses are limited and can be compensated through the PES program, increasing their willingness to participate. 2. Adopting a learning by doing approach to accumulate knowledge and experience related to conservation species. | 1. Not only is there an increase in the population of conservation species, but also in the variety and number of other organisms. 2. Farmers promptly identify and eliminate factors threatening habitats and monitor annual changes in species populations. | 1. Enterprises are willing to participate in conservation efforts, creating a win-win situation for both conservation species and increased farmer income. 2. Local public infrastructure must consider whether it will pose a threat to endangered species. |

| Type of Species | Thought | Action | Emotion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prionailurus bengalensis | 1. The leopard cat threatens the operation of chicken coops, and the population is becoming increasingly scarce. | 2. With the advocacy of conservation organizations, assistance is provided to renovate chicken coops. | 3. Losses can be compensated while also conserving the leopard cat. |

| 1. Stray dogs threaten the movement of leopard cats. | 2. Planting trees or bananas can help conserve leopard cats. | 3. Selling bananas can increase income while also conserving leopard cats. | |

| Lutra lutra | 1. The construction of reservoirs has led to a decreasing population. | 2. Roadkill is a major cause of the decline in the otter population. 3. Community organizations help maintain habitats. | 4. To prevent the continued decline of otters, the species must be protected, as they are only found locally. |

| Tyto longimembris | 1. The concept of healthy eating. | 2. Using eco-friendly farming or organic cultivation methods to grow fruit, leading to an increase in field biomass and attracting barn owls or raptors for foraging. 3. The government installs nesting boxes to monitor changes in the barn owl population. | 4. Eco-friendly farming practices promote biodiversity, and losses of some agricultural products can be compensated. |

| Hydrophasianus chirurgus | 1. Infrastructure development has led to a decreasing population. | 2. Establishing ecological ponds and planting floating plants for species rehabilitation. 3. Encouraging farmers to participate in the conservation of the pheasant-tailed jacanas. | 4. Successful rehabilitation has led to a sense of accomplishment with an increase in population, and pheasant-tailed jacanas have become a distinctive cultural feature of the community. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, T.-Y.; Liu, W.-Y. Case in Taiwan Demonstrates How Corporate Demand Converts Payments for Ecosystem Services into Long-Run Incentives. Agriculture 2026, 16, 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020224

Lee T-Y, Liu W-Y. Case in Taiwan Demonstrates How Corporate Demand Converts Payments for Ecosystem Services into Long-Run Incentives. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):224. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020224

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Tian-Yuh, and Wan-Yu Liu. 2026. "Case in Taiwan Demonstrates How Corporate Demand Converts Payments for Ecosystem Services into Long-Run Incentives" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020224

APA StyleLee, T.-Y., & Liu, W.-Y. (2026). Case in Taiwan Demonstrates How Corporate Demand Converts Payments for Ecosystem Services into Long-Run Incentives. Agriculture, 16(2), 224. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020224