A Lightweight Facial Landmark Recognition Model for Individual Sheep Based on SAMS-KLA-YOLO11

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Acquisition and Feature Engineering

2.1. Data Source and Collection

2.2. Labeling Methods and Rules

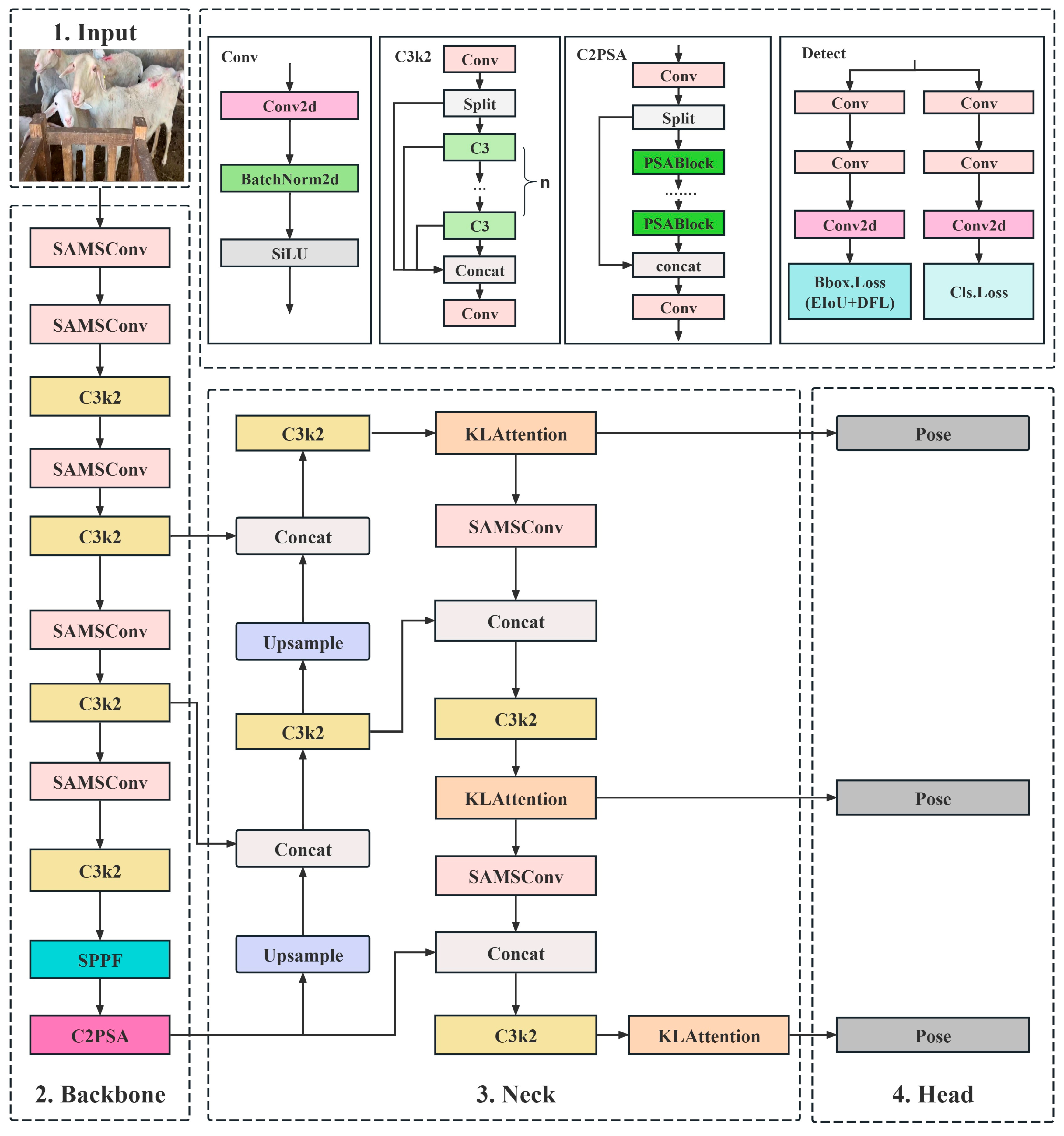

3. SAMS-KLA-YOLO11 Recognition Model

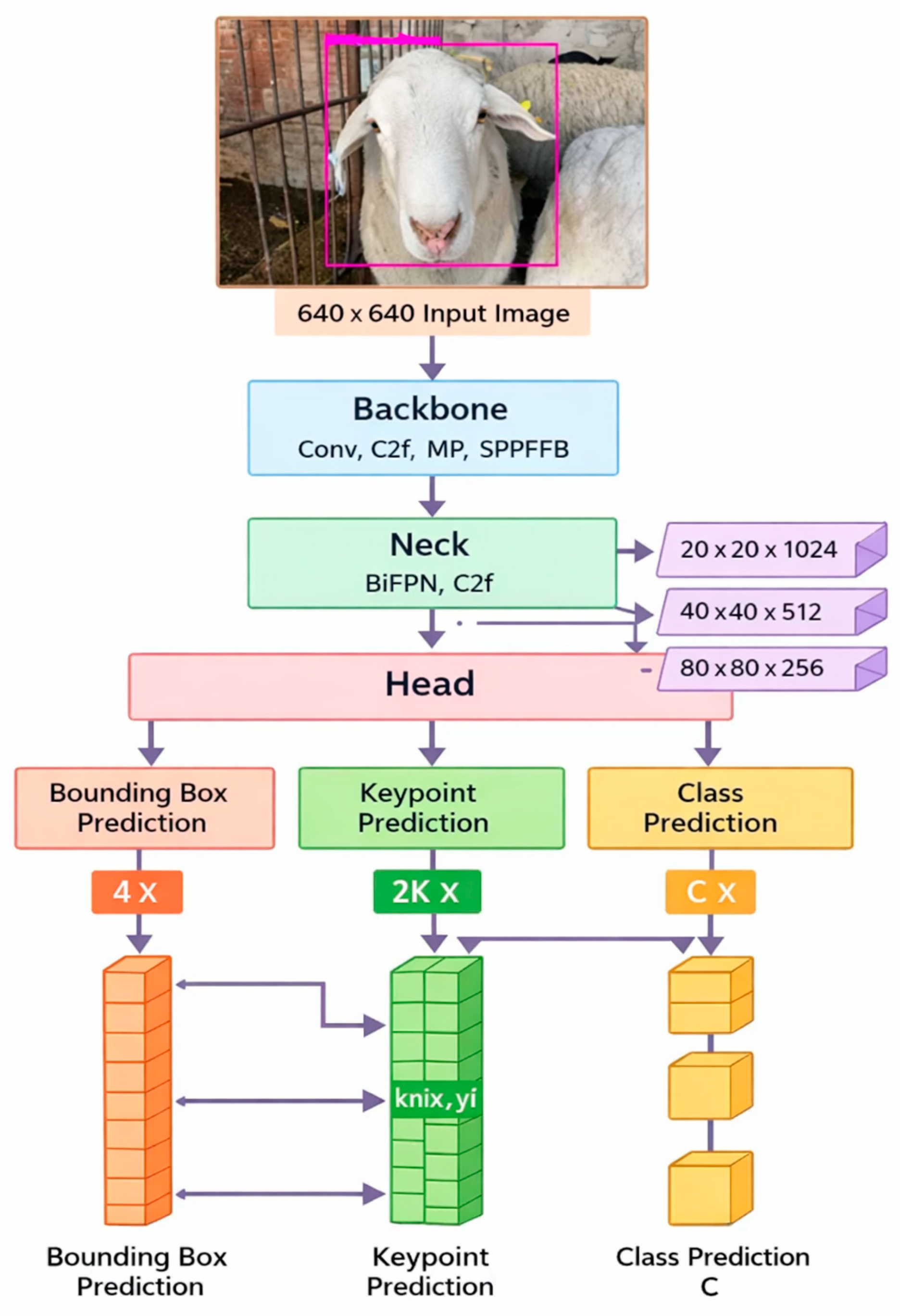

3.1. Original YOLO11 Model Framework

3.2. Model Improvement Strategy

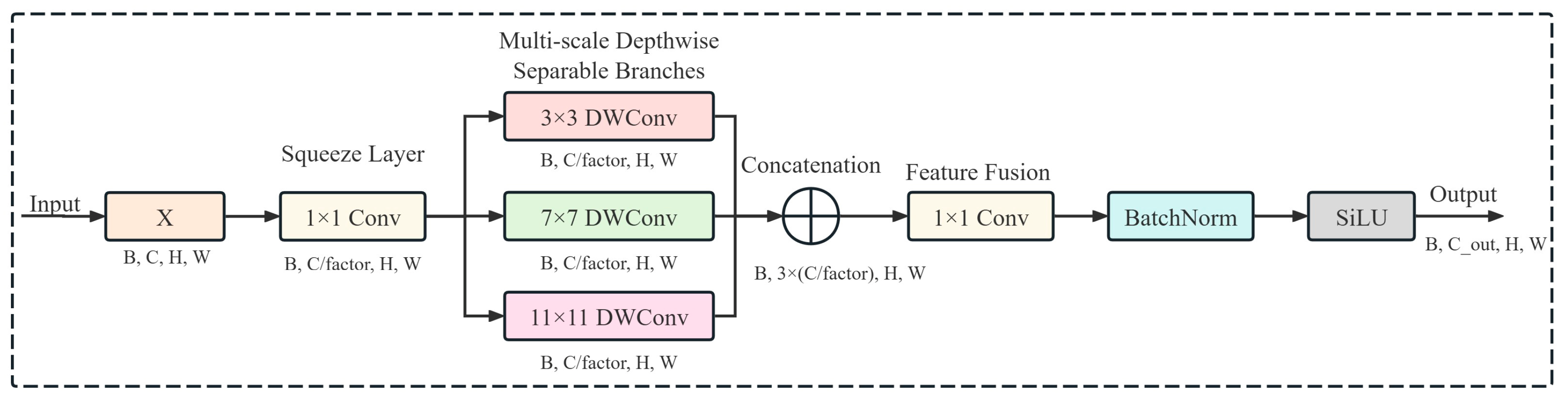

3.2.1. SAMSConv: Sheep Adaptive Multi-Scale Convolution Design

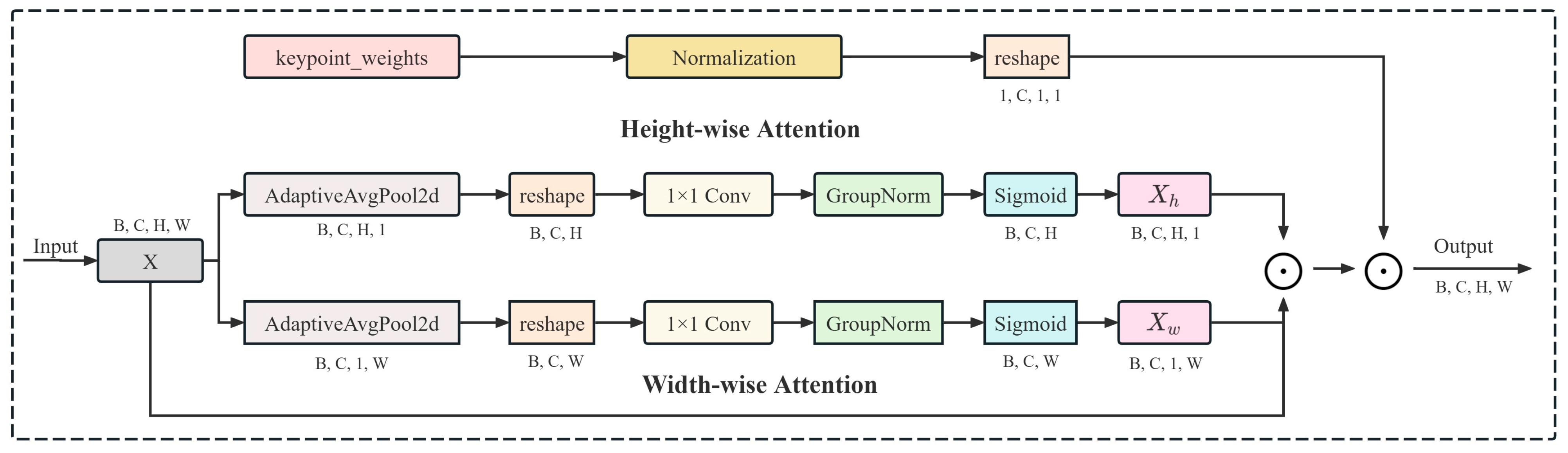

3.2.2. KLAttention: Keypoint Aware Lightweight Attention Module

3.2.3. EIoU Loss: Bounding Box Regression Optimization

3.3. Improve Overall Architecture of the Model

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Setting

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Comparison of Experimental Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Comparison with the Mainstream YOLO Series Model

4.3.2. Effectiveness of Individual Modules and Their Combinations

4.3.3. Comparison of SAMSConv with Other Lightweight Convolutional Structures

4.3.4. Comparison Between KLAttention and Other Attention Mechanisms

4.3.5. Comparison of EIoU and Other IoU Loss Functions

4.3.6. OKS-Based Keypoint Evaluation

4.4. Analysis of Visual Results

4.5. Failure Case Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meng, H.; Zhang, L.; Yang, F.; Hai, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J. Livestock biometrics identification using computer vision approaches: A review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Santos, S.; Goncalves, P. Precision agriculture for crop and livestock farming—Brief review. Animals 2021, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z.; Tan, H.; Tian, F.; Zhou, Y. Research progress of computer vision technology in smart sheep farm. China Feed 2021, 1, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Application of machine vision technology in animal husbandry. Agric. Eng. 2021, 11, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, R.S.; Sitton-Candanedo, I.; Garcia, O.; Prieto, J.; Rodriguez-Gonzalez, S. An intelligent Edge-IoT platform for monitoring livestock and crops in a dairy farming scenario. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 98, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Qi, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. VanillaFaceNet: A Cow face Recognition Method with high Accuracy and Fast Inference. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Hou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, H.; Dou, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, J. Cattle face keypoint detection and posture recognition method based on improved YOLO v7-Pose. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 84–92+102. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Wu, M.; Bao, J.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, P.; Liu, W.; Chen, G. Individual pig face recognition combined with attention mechanism. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.F.; Smith, M.L.; Smith, L.N.; Salter, M.G.; Baxter, E.M.; Farish, M.; Grieve, B. Towards on-farm pig face recognition using convolutional neural networks. Comput. Ind. 2018, 98, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsot, M.; Mei, J.; Shan, X.; Ye, L.; Feng, P.; Yan, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y. An adaptive pig face recognition approach using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Hou, Z.; Xuan, C.; Ma, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, L. A sheep identification method based on three-dimensional sheep face reconstruction and feature point matching. Animals 2024, 14, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurtz, K.; Camerlink, I.; D ’Eath, R.B.; Fernandez, A.P.; Norton, T.; Steibel, J.; Siegford, J. Recording behaviour of indoor-housed farm animals automatically using machine vision technology: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Yu, W.; Xuan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, P. A Large Benchmark Dataset for Individual Sheep Face Recognition. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ran, X. Deep learning with edge computing: A review. Proc. IEEE 2019, 107, 1655–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Yang, J.; Li, S. When mobilenetv2 meets transformer: A balanced sheep face recognition model. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.; Hao, J.; Sun, Y. Sheep face recognition method based on improved MobileFaceNet. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2022, 53, 267–274. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S. SheepFaceNet: A speed–accuracy balanced model for sheep face recognition. Animals 2023, 13, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Tian, F.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, S.; Du, X. Research on sheep face recognition algorithm based on improved AlexNet model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 24971–24979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Sun, Q.; Xuan, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Song, S. Lightweight small—Tailed han sheep facial recognition based on improved SSD algorithm. Agriculture 2024, 14, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Zhao, Y.; Koubaa, A.; Wu, L.; Khan, R.; Abdalla, F.Y. Automated sheep facial expression classification using deep transfer learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Xue, J.; Luo, G.; Qu, C.; Sun, W.; Qu, L. Comparative study on performance of Dorper × Hu crossbred F1 lambs and Hu sheep. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 60, 169–172+182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.W.; Qian, B.; Guan, F.; Hou, Z. Sheep face recognition model based on wavelet transform and convolutional neural network. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLO11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Ren, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 2022, 506, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Su, X.; Hai, N.; Huang, X. Pinwheel-shaped convolution and scale-based dynamic loss for infrared small target detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2025; pp. 9202–9210. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, M.G.d.; Fawcett, R.; Prisacariu, V.A. Dsconv: Efficient convolution operator. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 5148–5157. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, H. SCSA: Exploring the synergistic effects between spatial and channel attention. Neurocomputing 2025, 634, 129866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Ro, Y. Shvit: Single-head vision transformer with memory efficient macro design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 5756–5767. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.; Sun, L.; Dong, J.; Pan, J. SMFANet: A lightweight self-modulation feature aggregation network for efficient image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 359–375. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wang, P.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ye, R.; Ren, D. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 12993–13000. [Google Scholar]

- Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU loss: More powerful learning for bounding box regression. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, R. Wise-IoU: Bounding box regression loss with dynamic focusing mechanism. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.10051. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Xu, Y. MPDIoU: A loss for efficient and accurate bounding box regression. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.07662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Papaleo, F. Understanding others: Emotion recognition in humans and other animals. Genes Brain Behav. 2019, 18, e12544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistatos, M.C.; De Cola, T.; Kourtis, M.A.; Apostolopoulou, V.; Xilouris, G.K.; Sagias, N.C. AGRARIAN: A Hybrid AI-Driven Architecture for Smart Agriculture. Agriculture 2025, 15, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Han, S.; Guo, L.; Chi, L.; Yang, L. Artificial intelligence drives high-quality development of new quality productivity of animal husbandry: Constraints, generation logic and promotion path. Smart Agric. 2025, 7, 165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, J.; Rehman, A.U.; Othman, M.T.B.; Ahmad, M.; Tariq, H.B.; Khalid, M.A.; Moosa, M.A.R.; Shafiq, M.; Hamam, H. Deployment of wireless sensor network and iot platform to implement an intelligent animal monitoring system. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Configuration | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Operating system | Windows 11 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) |

| Central processing unit | Intel Core i5-14600KF (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) |

| GPU | RTX 4060 (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) |

| Application packages | python: 3.9, pytorch: 2.0, CUDA: 11.7 |

| Models | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | FLOPs (G) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO3-pose | 0.950 | 0.902 | 0.956 | 0.948 | 19.8 | 12.66 M |

| YOLO5-pose | 0.921 | 0.867 | 0.921 | 0.906 | 7.3 | 2.58 M |

| YOLO6-pose | 0.919 | 0.826 | 0.910 | 0.895 | 11.9 | 4.27 M |

| YOLO8-pose | 0.929 | 0.883 | 0.936 | 0.920 | 8.4 | 3.08 M |

| YOLO9-pose | 0.928 | 0.894 | 0.938 | 0.921 | 7.8 | 2.03 M |

| YOLO10-pose | 0.907 | 0.848 | 0.924 | 0.911 | 6.8 | 2.34 M |

| YOLO11-pose | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO12-pose | 0.933 | 0.886 | 0.946 | 0.927 | 6.6 | 2.63 M |

| SAMS + KLA + YOLO11 | 0.983 | 0.963 | 0.986 | 0.980 | 5.9 | 2.27 M |

| EIoU | KLAttention | SAMSConv | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | FLOPs(G) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| × | × | × | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| √ | × | × | 0.942 | 0.920 | 0.958 | 0.949 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| × | √ | × | 0.949 | 0.928 | 0.968 | 0.954 | 6.8 | 2.75 M |

| × | × | √ | 0.943 | 0.914 | 0.963 | 0.951 | 5.7 | 2.18 M |

| √ | √ | × | 0.958 | 0.943 | 0.974 | 0.962 | 6.8 | 2.75 M |

| × | √ | √ | 0.961 | 0.957 | 0.980 | 0.973 | 5.9 | 2.27 M |

| √ | × | √ | 0.954 | 0.925 | 0.967 | 0.960 | 5.7 | 2.18 M |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.983 | 0.963 | 0.986 | 0.980 | 5.9 | 2.27 M |

| Models | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | FLOPs (G) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11 | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + SAMSConv | 0.943 | 0.914 | 0.963 | 0.951 | 5.7 | 2.18 M |

| YOLO11 + DSConv | 0.950 | 0.896 | 0.956 | 0.940 | 4.9 | 2.67 M |

| YOLO11 + PConv | 0.963 | 0.894 | 0.959 | 0.942 | 7.4 | 2.53 M |

| YOLO11 + DWConv | 0.939 | 0.877 | 0.940 | 0.924 | 5.0 | 2.00 M |

| YOLO11 + GhostConv | 0.941 | 0.856 | 0.931 | 0.916 | 5.8 | 2.33 M |

| Models | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | FLOPs (G) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11 | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + KLAttention | 0.949 | 0.928 | 0.968 | 0.954 | 6.8 | 2.75 M |

| YOLO11 + CBAM | 0.937 | 0.907 | 0.951 | 0.936 | 6.7 | 2.75 M |

| YOLO11 + SCSA | 0.929 | 0.898 | 0.946 | 0.931 | 6.6 | 2.67 M |

| YOLO11 + SHSA | 0.936 | 0.892 | 0.941 | 0.924 | 6.8 | 2.75 M |

| YOLO11 + SMFA | 0.923 | 0.916 | 0.946 | 0.932 | 8.0 | 3.54 M |

| Models | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50–95 | FLOPs (G) | Params |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLO11 | 0.938 | 0.895 | 0.951 | 0.938 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + EIoU | 0.942 | 0.920 | 0.958 | 0.949 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + DIoU | 0.927 | 0.901 | 0.951 | 0.936 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + SIoU | 0.928 | 0.895 | 0.946 | 0.930 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + WIoU | 0.940 | 0.892 | 0.951 | 0.935 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

| YOLO11 + MPDIoU | 0.921 | 0.892 | 0.951 | 0.932 | 6.6 | 2.66 M |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bai, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, W. A Lightweight Facial Landmark Recognition Model for Individual Sheep Based on SAMS-KLA-YOLO11. Agriculture 2026, 16, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020151

Bai Y, Zhao X, Liang X, Zhang Z, Yan Y, Li F, Zhang W. A Lightweight Facial Landmark Recognition Model for Individual Sheep Based on SAMS-KLA-YOLO11. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020151

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Yangfan, Xiaona Zhao, Xinran Liang, Zhimin Zhang, Yuqiao Yan, Fuzhong Li, and Wuping Zhang. 2026. "A Lightweight Facial Landmark Recognition Model for Individual Sheep Based on SAMS-KLA-YOLO11" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020151

APA StyleBai, Y., Zhao, X., Liang, X., Zhang, Z., Yan, Y., Li, F., & Zhang, W. (2026). A Lightweight Facial Landmark Recognition Model for Individual Sheep Based on SAMS-KLA-YOLO11. Agriculture, 16(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020151