Impact of Meteorological Conditions on the Bird Cherry–Oat Aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) Flights Recorded by Johnson Suction Traps

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aphid Sampling

2.2. Meteorological Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

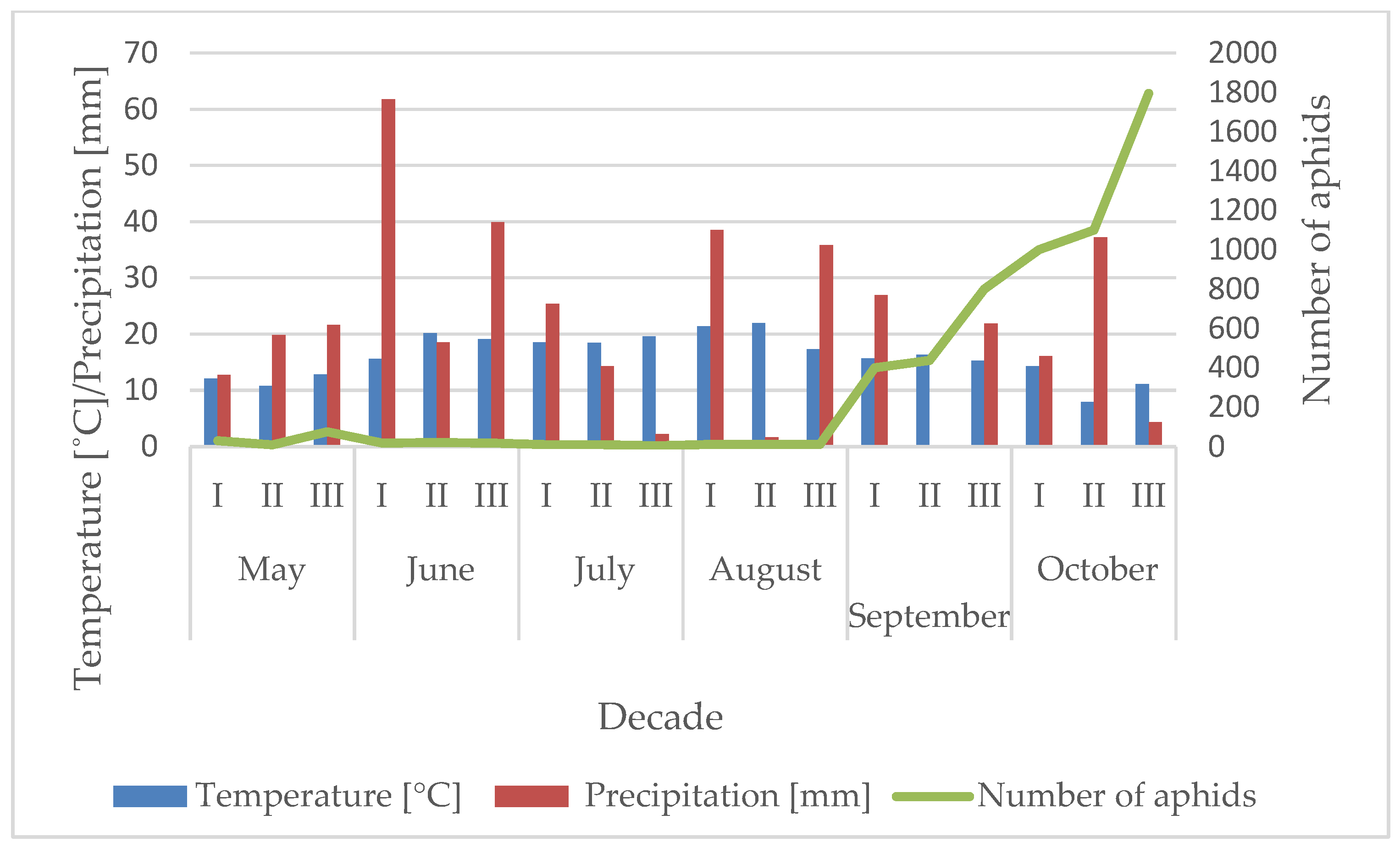

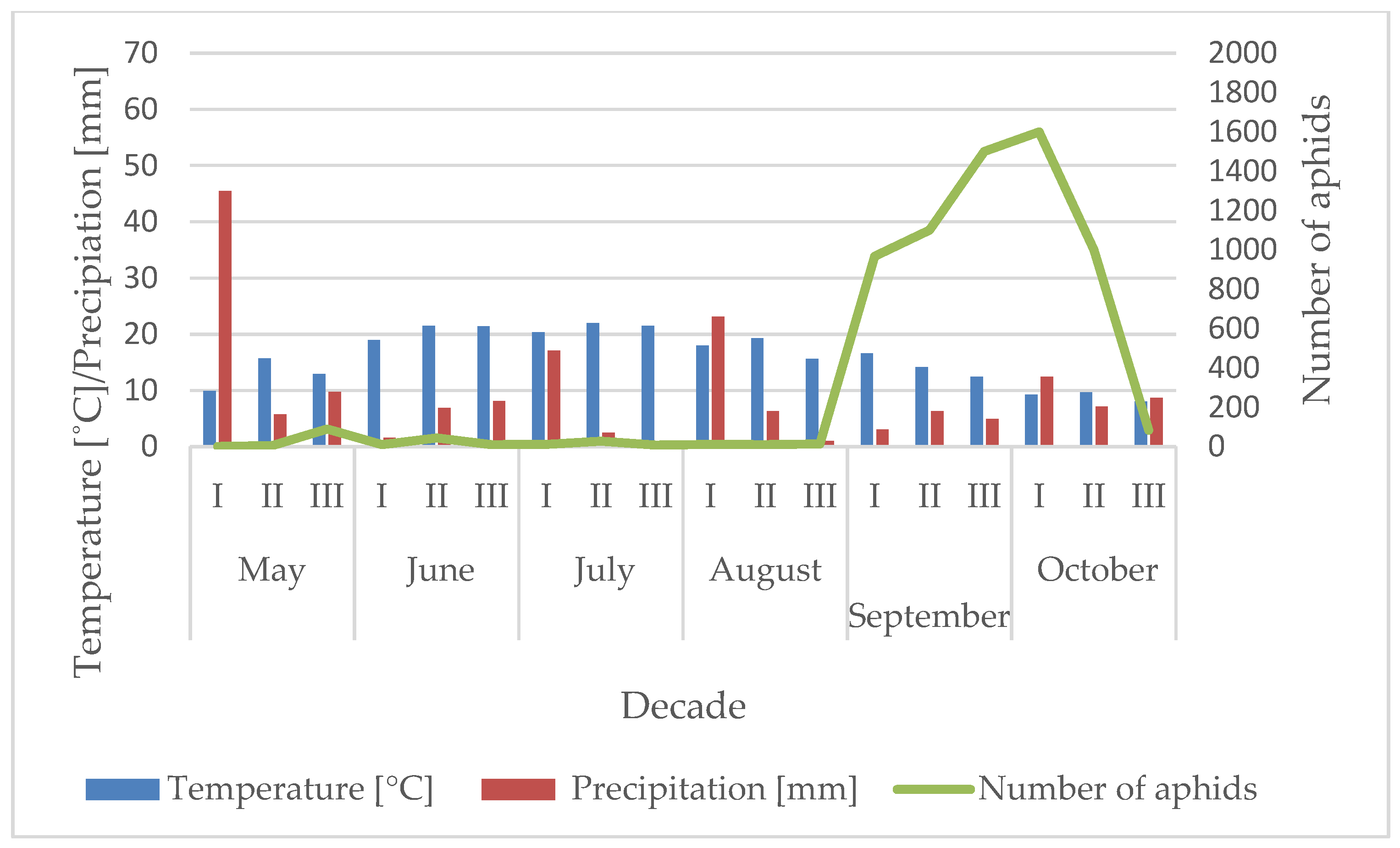

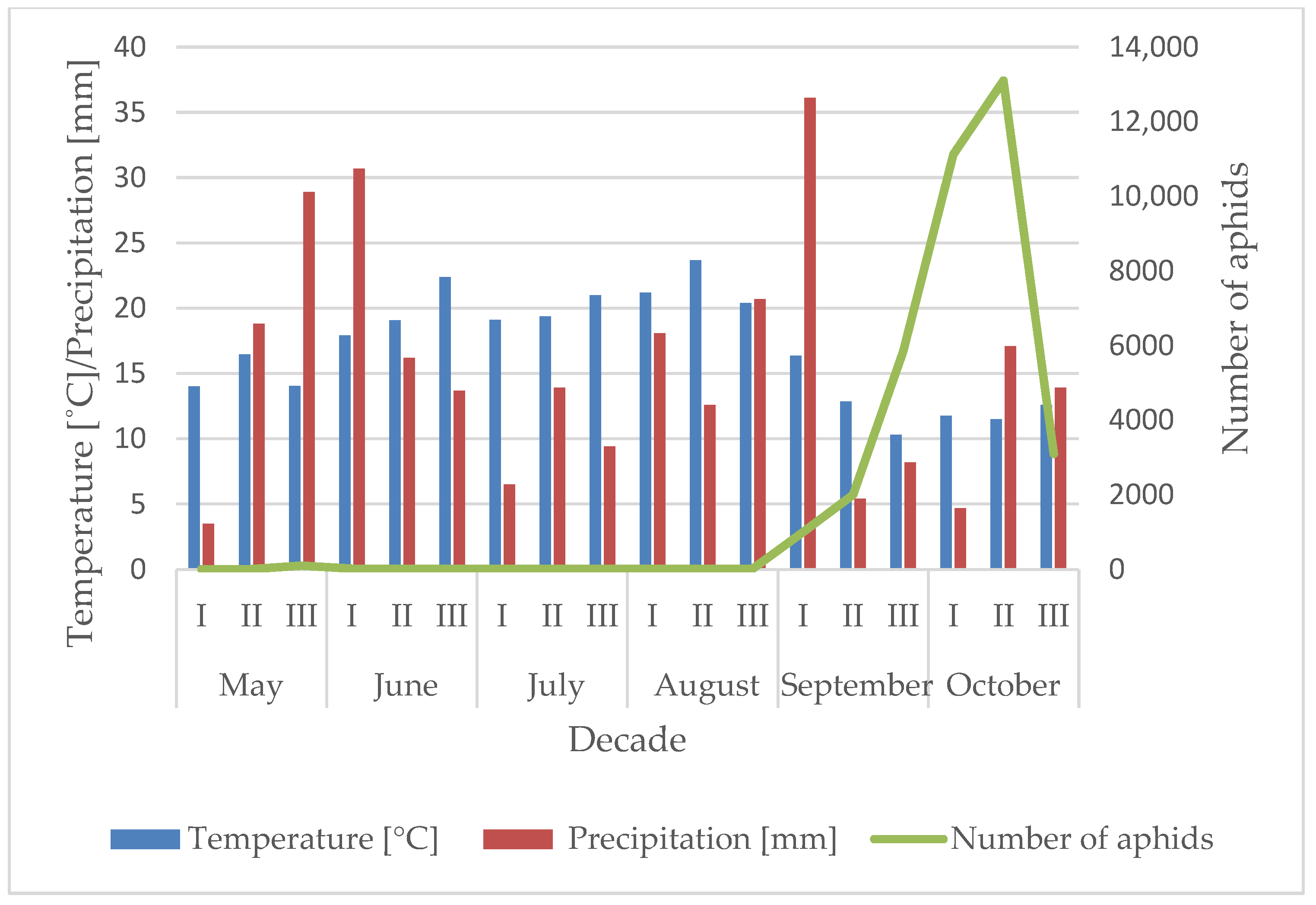

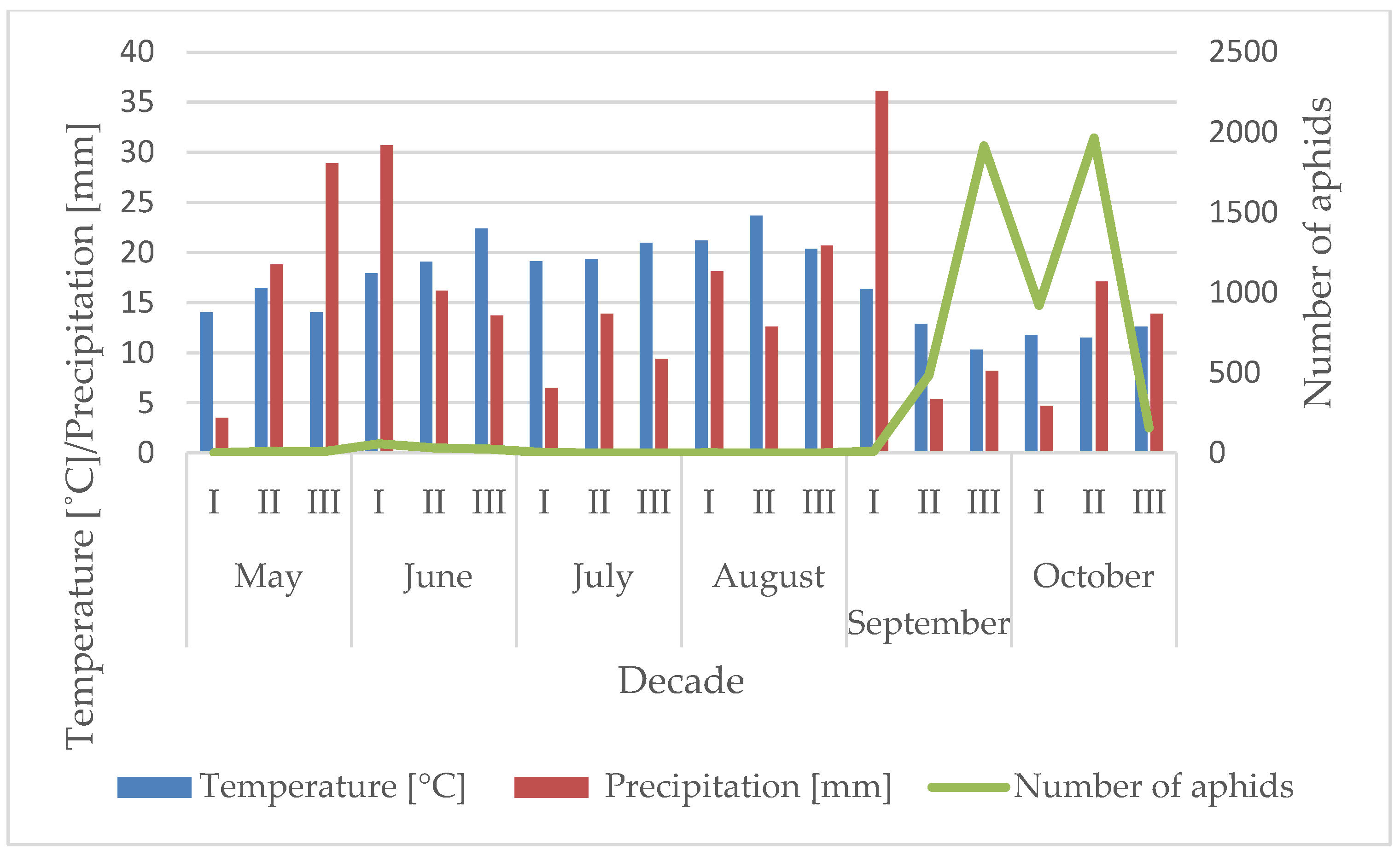

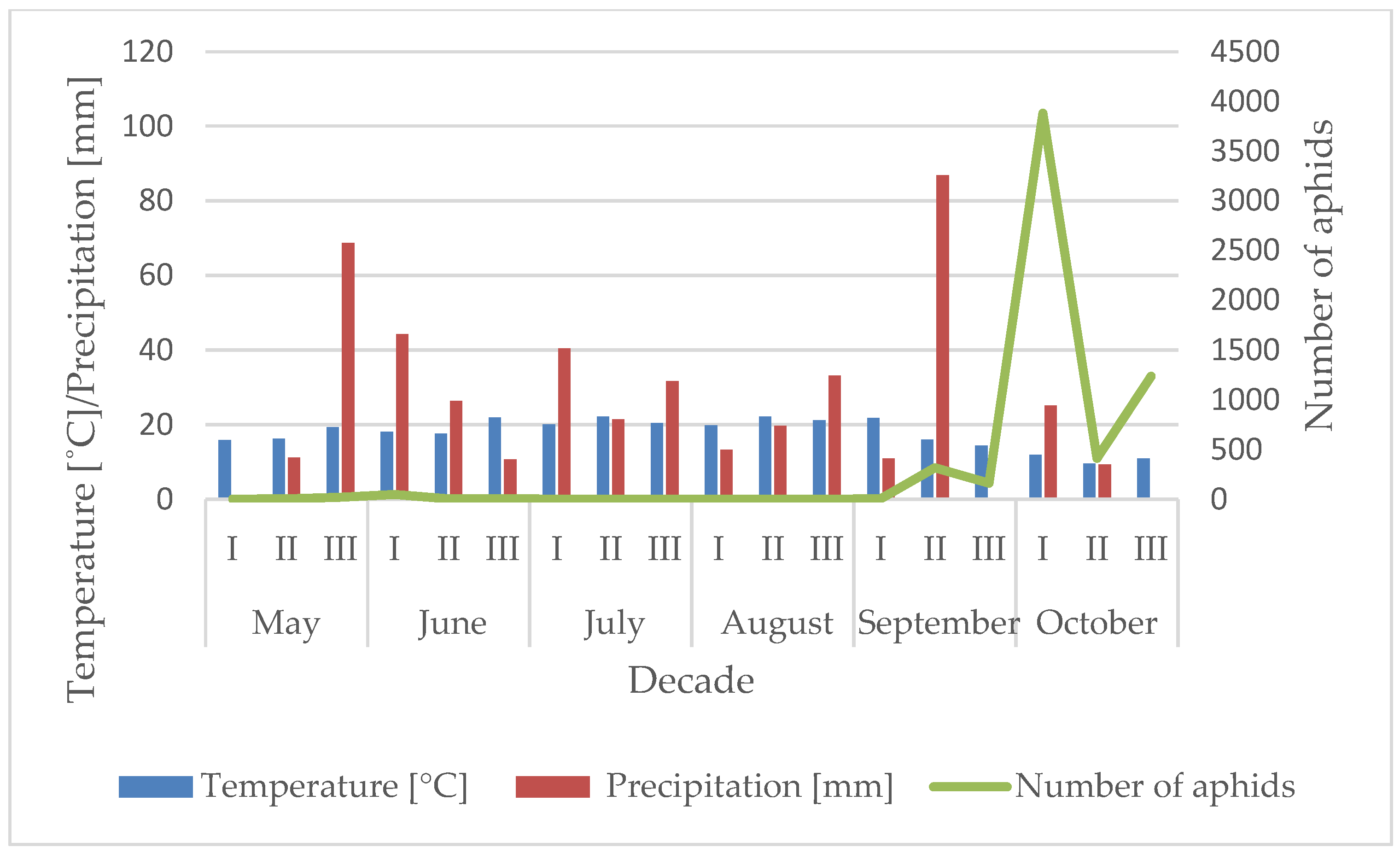

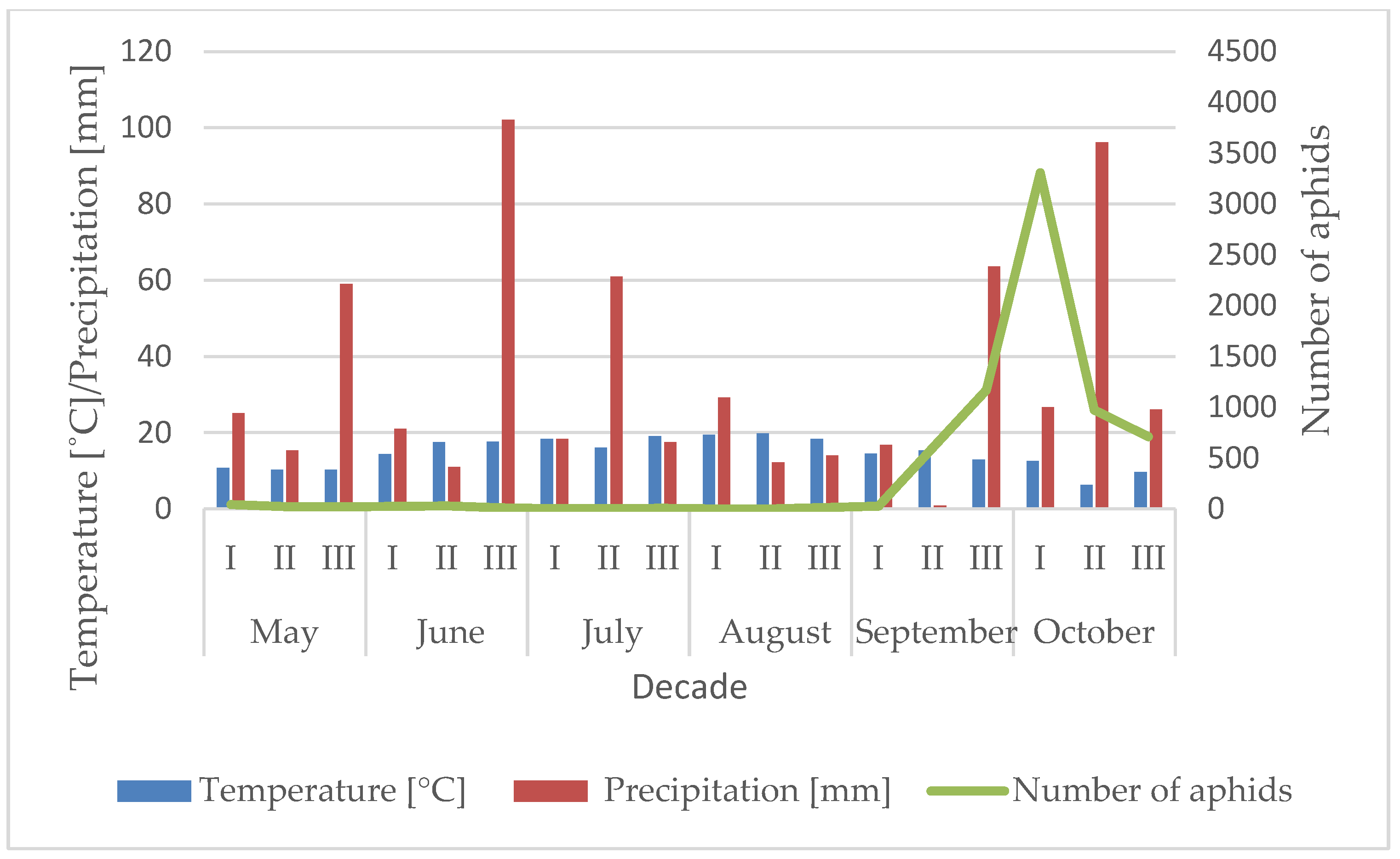

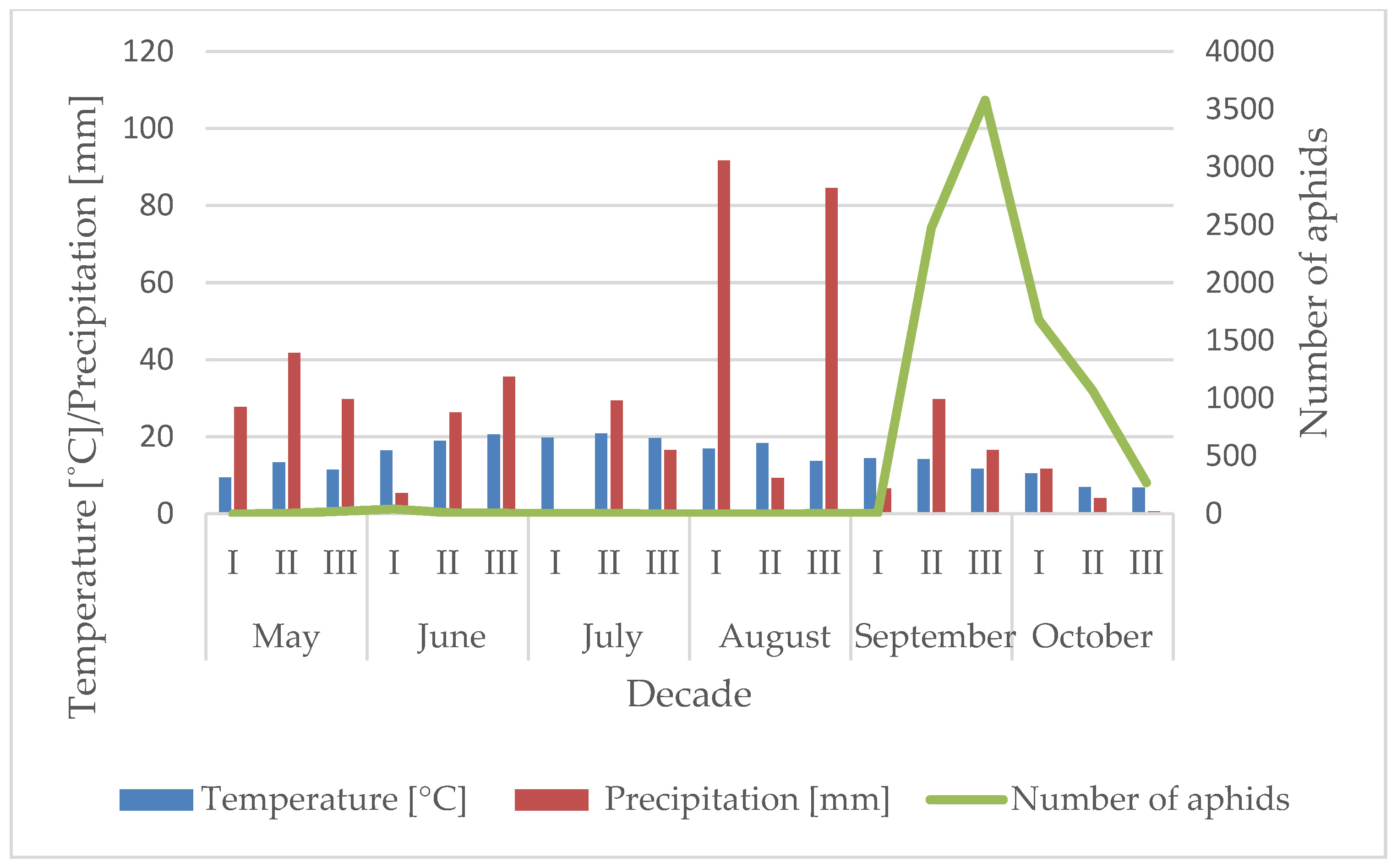

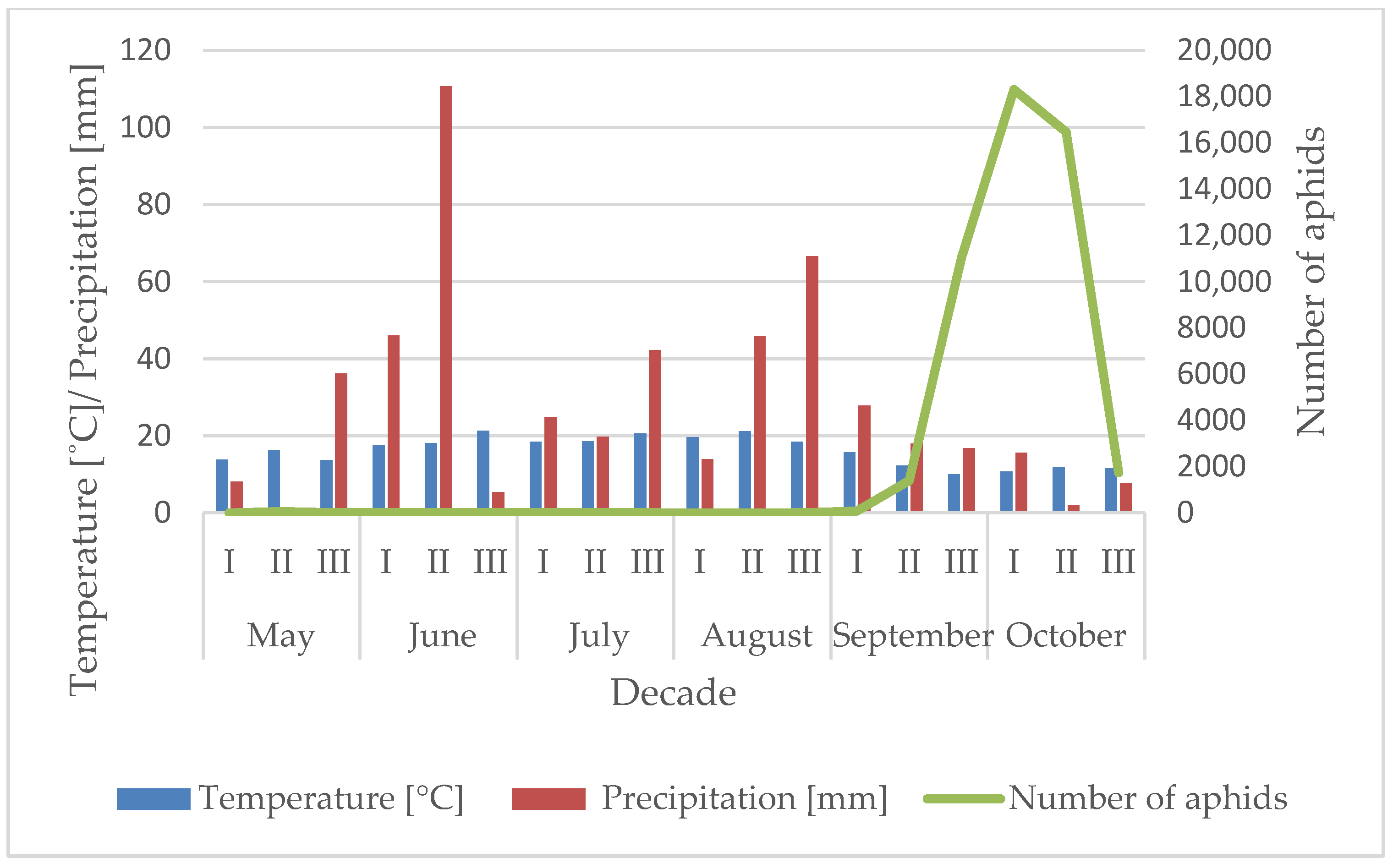

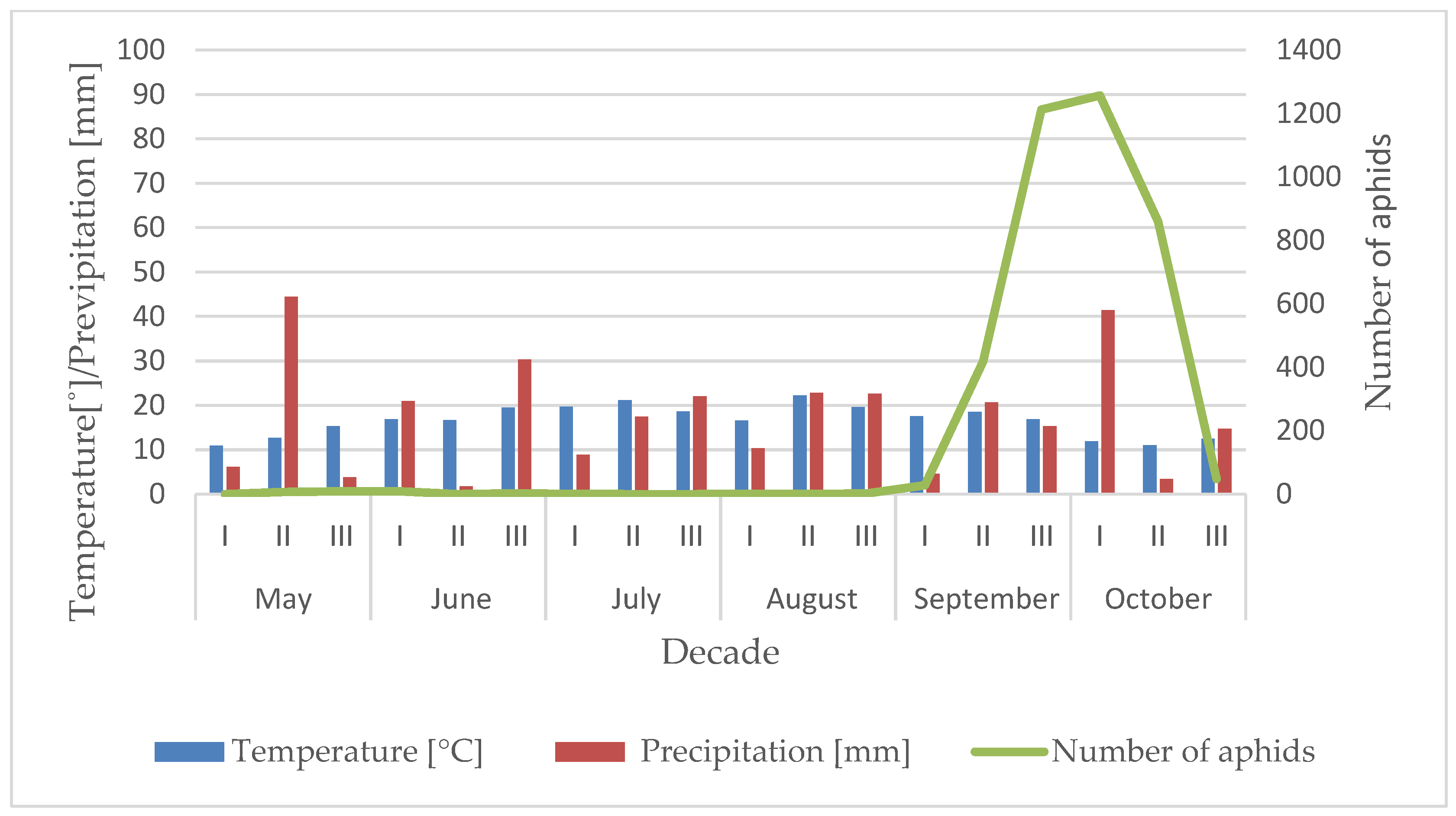

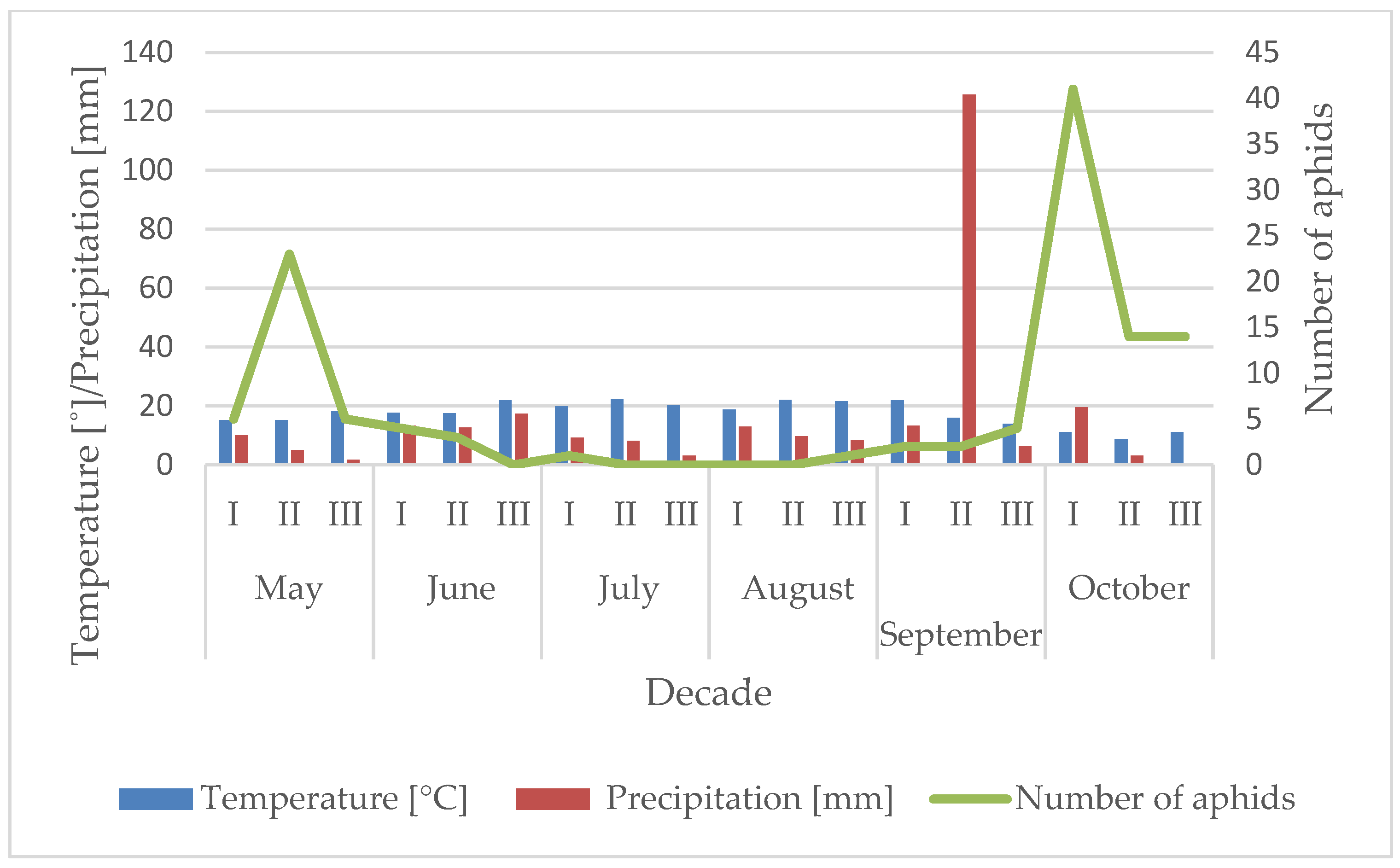

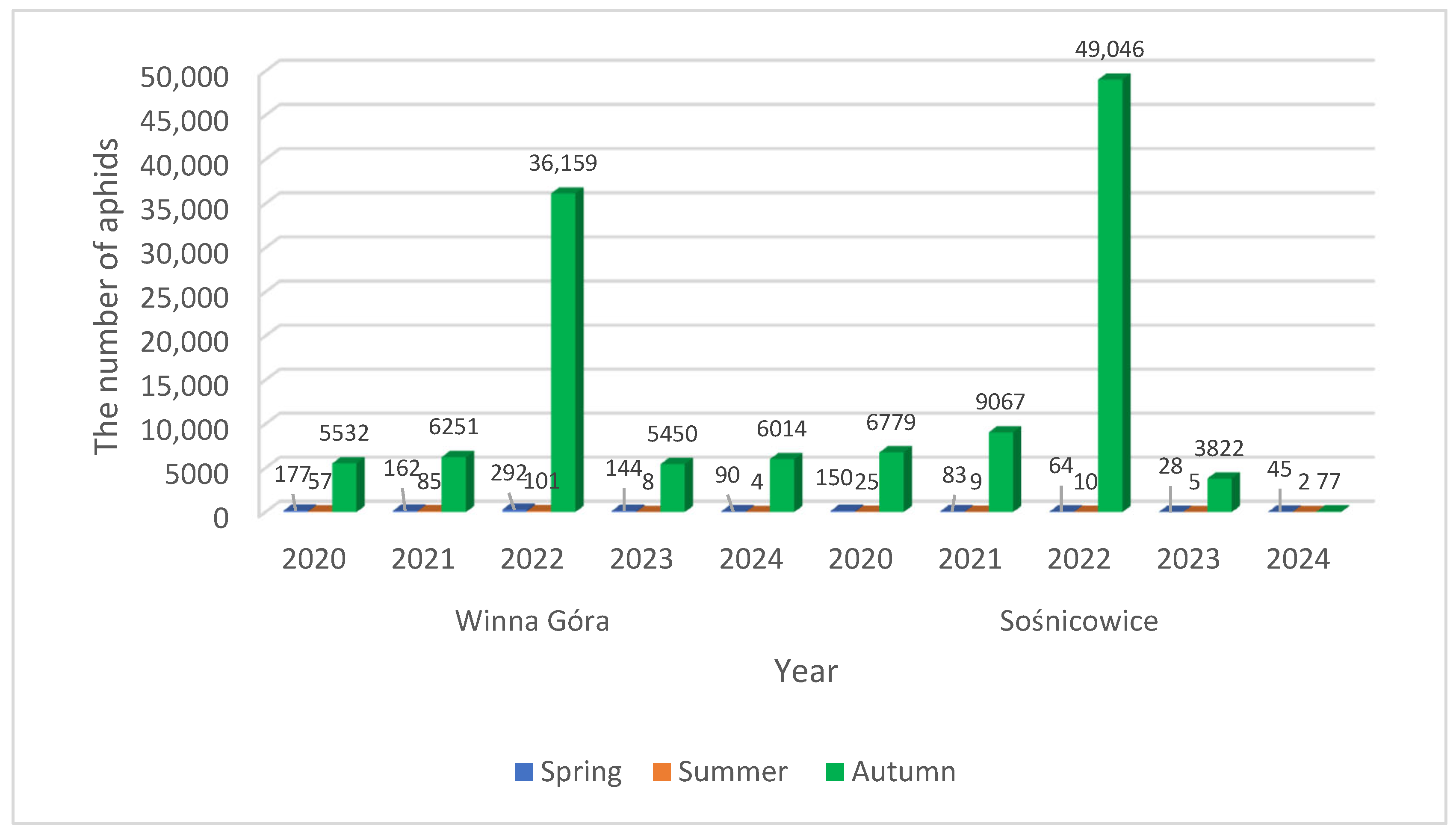

3.1. Influence of the Temperature and Precipitation on the Flight Activity of R. padi

3.2. Dates of the Beginning of First Flights of R. padi Caught by the Johnson Suction Trap

3.3. The Significance of Aphids and Their Monitoring in Plant Protection

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mrówczyński, M.; Walczak, F.; Korbas, M.; Paradowski, A.; Roth, M. Zmiany klimatyczne a zagrożenia roślin rolniczych przez agrofagi. Stud. Rap. IUNG–PIB 2009, 17, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, R.; Bale, J.S.; Tatchell, G.M. Aphids in a changing climate. In Insects in a Changing Environment; Harrington, R., Stark, N.E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995; Volume 535, pp. 126–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hulle, M.; Cœur d’Acier, A.; Bankheat-Dronnet, S.; Harrington, R. Aphids in the face of global changes. Competes Rendus Biol. 2010, 333, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindlmann, P.; Dixon, A.F.G.; Michaud, J.P. (Eds.) Aphid Biodiversity Under Enviromental Change; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; p. 191. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.R.; Anderson, L.; Izera, I.D.; Kruger, T.; Parker, S.; Pickup, J.; Shortall, C.R.; Taylor, M.S.; Verrier, P.; Harrington, R. Onwards and upwards—Aphid flight trends follow climate change. J. Anim. Ecol. 2015, 84, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J.R.; Anderson, L.; Izera, I.D.; Kruger, T.; Parker, S.; Pickup, J.; Shortall, C.R.; Taylor, M.S.; Verrier, P.; Harrington, R. Longterm phonological trends, species accumulation rates, aphid trait and climate: Five decades of change in migrating aphids. J. Anim. Ecol. 2015, 84, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strażyński, P.; Ruszkowska, M. The life cycle functional response of Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) to higher temperature: Territorial expansion of permanent parthenogenetic development as a result of warmer weather conditions. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2015, 55, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodynko-Filas, N.; Pruszyński, G.; Strażyński, P. Wirus żółtaczki rzepy (Turnip Yellows Virus, TuYV) i jego wektory—Nowe zagrożenie w uprawie rzepaku. In Proceedings of the Streszczenia 57, Sesji Naukowej IOR–PIB, Poznań, Poland, 9–10 February 2017; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Vereijken, P.H. Feeding and multiplication of Three Cereal Aphid Species and Their Effect on Yield of Winter Wheat. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1979; pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, G.; Hagele, R.; Wetzel, T. Untersuchungen zur Okonomie der Bekampfung der Getrideblattlaus (Macrosiphum (Sitobion) avenae F.) in Winterweizen. Nachrichtenblatt Pflanzenschutz DDR 1988, 42, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mrówczyński, M.; Wachowiak, H.; Boroń, M. Szkodniki zbóż–aktualne zagrożenia w Polsce. Cereals pests–current thereats in Poland. Prog. Plant Prot. Post. Ochr. Roślin 2005, 45, 929–932. [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, F. Monitoring agrofagów dla potrzeb integrowanej ochrony roślin uprawnych. Agrophages monitoring for plant integrated control needs. Fragm. Agron. 2010, 27, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Roik, K.; Strażyński, P.; Baran, M.; Bocianowski, J. Analiza poziomu zasiedlenia pszenicy ozimej przez mszycę zbożową (Sitobion avenae F.) w różnych rejonach Polski w latach 2009–2018. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2022, 62, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P.; Ruszkowska, M.; Jeżewska, M.; Trzmiel, K. Evaluation of the Risk of the Autumn Infections of Winter Barley with Barley Yellow Dwarf Viruses in Poland in the Years 2006–2008. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2011, 51, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruszkowska, M. Uwarunkowania klimatyczne w rozprzestrzenianiu najważniejszych wektorów chorób wirusowych na zbożach w badanych regionach Polski. Permanent and cyclic parthenogenesis of Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) (Homoptera: Aphidoidea) across different climate regions in Poland. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2006, 46, 276–283. [Google Scholar]

- Klueken, A.M.; Hau, B.; Ulber, B.; Poehling, H.M. Forecasting migration of cereal aphids (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in autumn and spring. J. Appl. Entomol. 2009, 133, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strażyński, P. Population structure of Rhopalosiphum padi (Linnaeus, 1758)/Hemiptera, Aphidoidea/ in Wielkopolska region in 2003–2008 in the context of winter cereals threat of BYDV expansion. In Aphids and Other Hemipterous Insects; Goszczyński, W., Herczek, A., Leszczyński, B., Łabanowski, G., Podsiadło, E., Rakauskas, R., Ruszkowska, M., Wilkaniec, B., Wojciechowski, W., Eds.; The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin: Lublin, Poland, 2010; Volume 16, pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P.; Ruszkowska, M.; Węgorek, P. Dynamika lotów mszyc w latach 2008–2010 najliczniej odławianych w Poznaniu aspiratorem Johnsona. Flights dynamics of aphids caught numerously by Johnson’s suction trap in Poznań in 2008–2010. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2011, 51, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska, M. Choroby wirusowe zbóż w Polsce. Choroby wirusowe zbóż w Polsce, występowanie i zapobieganie. Poznań, 2010, p. 4. Available online: https://www.agrofagi.com.pl/plik,podglad,2773,choroby-wirusowe-zboz-w-polsce.jpg (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Gray, S.M.; Power, A.G.; Smith, D.M.; Seaman, A.J.; Altman, N.S. Aphid transmission of Barley Yellow DwarfVirus: Acquisition acces periods and virus concentration requirements. Phytopatology 1991, 81, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocka, E.; Goszczyński, W.; Leszczyński, W. Wykorzystanie techniki EPG do oceny podatności roślin na mszyce. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 1998, 50, 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska, M. Choroby wirusowe zbóż w Polsce diagnostyka i występowanie. Ochr. Roślin 1995, 6, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska, M. Wirus żółtej karłowatości jęczmienia-niebezpieczny patogen wszystkich gatunków zbóż. Ochr. Roślin 2001, 45, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jeżewska, M. Choroby wirusowe zbóż, diagnostyka i występowanie. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2003, 43, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Kröber, T.; Carl, K. Cereal aphids and their natural enemies in Europe—A literature review. Biocontrol News Inf. 1991, 12, 4. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowska, M. Przekształcenia cyklicznej partenogenezy mszycy Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) (Homoptera: Aphidoidae)—znaczenie zjawiska w adaptacji środowiskowej. Rozpr. Nauk. Inst. Ochr. Roślin 2002, 8, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowska, M. Modyfikacja progów szkodliwości i metody alternatywne w warunkach powstawania nowych form rozwojowych mszyc. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2004, 44, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Hurej, M. Wrażliwość mszyc na ekstremalne temperatury. Wiadomości Entomol. 1991, 1, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyński, B. Wpływ czynników klimatycznych na populację mszyc zbożowych. Zesz. Probl. Postępów Nauk. Rol. 1990, 392, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Leszczyński, B.; Urbańska, A.; Wereda, I. Some factors influencing spring and autumn migrations of bird cherry-oat aphid in Eastern Poland. In Aphids and Other Homopterous Insects; Cichocka, E., Goszczyński, W., Leszczyński, M., Ruszkowska, W., Wojciechowski, W., Eds.; PAS: Siedlce, Poland, 2001; Volume 8, pp. 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowska, M.; Strażyński, P. Mszyce na Oziminach; Instytut Ochrony Roślin: Poznań, Poland, 2007; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L.R. An improved suction trap for insect. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1951, 38, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.; Pike, K.S. An inexpensive suction trap and its use in an aphid monitoring network. J. Agric. Entomol. 1988, 5, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.P. Mszyce-Szkodniki Roślin: Terenowy Klucz do Oznaczania; Instytut Zoologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warszawa, Poland, 1976; p. 119. [Google Scholar]

- Remadieurѐ, G.; Remadieurѐ, M. Catalogue des Aphididae du Monde; Instiut National de la racherche Agronomique: Paris, France, 1977; p. 473. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, L.R. A Handbook for Aphid Identification; Euraphid—Rothamsted, Experimental Station: Rothamsted, UK, 1984; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Blacman, R.L.; Eastop, V.F. Aphids on the Words Crops, an Identification and Information Guide, 2nd ed.; The Natural History Museum: London, UK, 2000; p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, J. Host Plant Catalog of Aphids; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; p. 1140. [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak, K.; Niedbała, W. Wskaźniki biocenotyczne stosowane przy porządkowaniu i analizie danych w badaniach ilościowych. s. 397–416. In Metody Stosowane w Zoologii Gleby; Górny, M., Grüm, L., Eds.; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1981; p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P. Znaczenie rejestracji lotów ważnych gospodarczo gatunków i form mszyc w odłowach aspiratorem Johnsona w Poznaniu w latach 2003–2005 w integrowanych metodach ochrony roślin. Importance of registration of flights of economically important species and forms of aphids in catches by Johnson’s suction trap in Poznań in 2003–2005 in integrated plant protection methods. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2006, 46, 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Honěk, A.; Martinkowá, Z.; Brabec, M.; Saska, P. Predicting aphid abundance on winter wheat using suction trap catches. Plant Prot. Sci. 2020, 56, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavíková, L.; Fryč, D.; Kundu, J.K. Analysis of Twenty Years of Suction Trap Data on the Flight Activity of Myzus persicae and Brevicoryne brassicae, Two Main Vectors of Oilseed Rape Infection Viruses. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocianowski, J.; Liersch, A. Multidimensional Analysis of Diversity in Genotypes of Winter Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VSN International. VSN International Genstat for Windows, 23rd ed.; VSN International Hemel: Hempstead, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P.; Roik, K. Rejestracja dynamiki lotów wazniejszych gospodarczo gatunków mszyc za pomocą aspiratora Johnsona i jej znaczenie w integrowanej ochronie upraw rolniczych. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2021, 61, 2021–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez, R. How are insects responding to global warming? Tijdschr. Voor Entomol. 2007, 150, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Złotkowski, J. Znaczenie pułapki ssącej Johnsona w badaniach migracji mszyc w Polsce w latach 1973–2010. The importance of Johnson’s suction trap in the study of aphid migration in Poland in the years 1973–2010. Prog. Plant Prot./Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2011, 51, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak-Sobkowiak, B.; Durak, R. Biology and ecology of Appendiseta robiniae (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea)—An alien species in Europe. Open Life Sci. 2012, 7, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, J.S.; Masters, G.J.; Hodkinson, I.D.; Awmack, C.; Bezemer, T.M.; Brown, V.K.; Butterfield, J.; Buse, A.; Coulson, J.C.; Farrar, J.; et al. Herbivory in global climate change research: Direct effects of rising temperature on insect herbivores. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2002, 8, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, R.; Fleming, R.A.; Woiwod, I.P. Climate change impacts on insect management and conservation in temperate regions: Can they be predicted? Agric. For. Entomol. 2001, 3, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritopoulos, J.T.; Tsitsipis, J.A.; Goudoudaki, S.; Blackman, R.L. Life cycle variation of Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae) in Greece. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2002, 92, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, K.; Yokozawa, M.; Nishimori, M.; Ueda, Y.; Yokosuka, T. How to analyze long-term insect population dynamics under climate change: 50-year data of three insect pests in paddy fields. Popul. Ecol. 2006, 48, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigton, R.; Tatchell, G.M.; Bale, J.S. Weather, lifecycle strategy and spring populations of aphids. Acta Phytopathol. Entomol. Hung. 1990, 25, 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Klueken, A.M.; Hau, B.; Freier, B.; Friesland, H.; Kleinhenz, B.; Poehling, H.M. Comparison and validation of population models for cereal aphids. Forecasting migration of cereal aphids. J. Plantd Dis. Prot. 2009, 116, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kwon, S.H.; Kim, T.O.; Oh, S.O.; Kim, D.-S. Temperature-dependent development and fecundity of Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on corns. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 2016, 55, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutelabian, A.; Haghani, M.; Norbakhsh, H.; Abbasipour, H.; Toorani, A.H. Selected demografic data of the bird chery-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi L. on corn, Zea mays L. at different temperaturesd. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2020, 22, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P. Wybrane element rozwoju mszycy czeremchowo-zbożowej (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) na żywicielu pierwotnym (Prunus padus L.) w Poznaniu w latach 2007–2008. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2010, 50, 1308–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Brabec, M.; Honěk, A.; Pekár, S.; Martinková, Z. Population dynamics of aphids on cereals: Digging in the time-series data to reveal population regulation caused by temperature. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basky, Z.; Harrington, R. Cereal aphid flight activity in Hungary and England compared by suction traps. Anz. Schädlingskunde Pflanzenschutz Umweltschutz 2000, 73, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Barro, P.J.; Sherratt, T.N.; Brookes, C.P.; David, O.; Maclean, N. Spatial and temporal genetic variation in British field populations of the grain aphid Sitobion avenae (F.) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) studied using RAPD-PCR. Proc. R. Soc. B 1995, 262, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J.C.; Baumann, S.; Sunnucks, P.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Pierre, J.S.; Le Gallic, J.F.; Dedryver, C.A. Reproductive mode and population genetic structure of the cereal aphid Sitobion avenae studied using phenotypic and microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol. 1999, 8, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantegenest, M.; Pierre, J.S.; Dedryver, C.A.; Kindlmann, P. Assessment of the relative impact of different natural enemies on population dynamics of the grain aphid Sitobion avenae in the field. Ecol. Entomol. 2001, 26, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papura, D.; Simon, J.C.; Halkett, F.; Delmotte, F.; Le Gallic, J.F.; Dedryver, C.A. Predominance of sexual reproduction in Romanian populations of the aphid Sitobion avenae inferred from phenotypic and genetic structure. Heredity 2003, 90, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialatte, A.; Plantegenest, M.; Simon, J.C.; Dedryver, C.A. Farm-scale assessment of movement patterns and colonisation dynamics of the grain aphid in arable crops and hedgerows. Agric. For. Entomol. 2007, 9, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedryver, C.A.; Fievet, V.; Plantegenest, M.; Vialatte, A. An overview of the functioning of Sitobion avenae populations at three spatial scales in France. Redia 2009, XCII, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Strażyński, P. Dynamics of aphid seasonal flights in Johnson’s suction trap in Poznań in 2003–2004. In Aphids and Other Hemipterous Insects; Cichocka, E., Goszczyński, W., Ruszkowska, M., Wilkaniec, B., Nowak, P., Kowalski, G., Eds.; Agricultural University of Poznań: Poznań, Poland, 2005; Volume 11, pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Złotkowski, J.; Wolski, A. Badania nad migracjami mszyc przy użyciu aspiratora Johnsona w Winnej Górze w latach 2000–2007. Studies on migrations of aphids with the use of Johnson’s suction trap in Winna Góra during the period of 2000–2007. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2008, 48, 1013–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Złotkowski, J. Sezonowe zmiany w dynamice migracji mszyc w okolicach Winnej Góry (Wielkopolska) w latach 2007–2008. Seasonal changes in aphid migration dynamics in the surrounding area of Winna Góra (Wielkopolska district) in 2007–2008. Prog. Plant Prot./Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2009, 49, 1242–1246. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowska, M.; Złotkowski, J. Badania populacyjne nad ważnymi gospodarczo gatunkami mszyc na podstawie połowów z powietrza. Cz. II. Dynamika sezonowa lotów mszyc. Population studies on economically important species of aphids based on aerial catching. Th. II. Seasonal dynamics of aphid flights. Pr. Nauk. Inst. Ochr. Roślin 1977, 19, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Złotkowski, J. Sezonowe aktywności lotów mszyc w odłowach aspiratorem Johnsona w latach 1998–2001. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2002, 49, 712–715. [Google Scholar]

- Złotkowski, J. Rejestracja sezonowych lotów ważnych gospodarczo mszyc w odłowach aspiratorem zainstalowanym na terenie Pracowni Doświadczalnictwa Polowego w Winnej Górze w latach 2001–2004. Registration of seasonal flights of economically important aphids in catches by suction trap installed in the Field Experimental Station in Winna Góra in the years 2001–2004. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2005, 45, 1229–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowska, M.; Strazyński, P. Profilaktyka w ochronie zbóż przed chorobą żółtej karłowatości jęczmienia. Prog. Plant Prot. Postępy Ochr. Roślin 2007, 47, 363–366. [Google Scholar]

- Tratwal, A.; Bereś, P.K.; Korbas, M.; Danielewicz, J.; Jajor, E.; Horoszkiewicz-Janka, J.; Jakubowska, M.; Roik, K.; Baran, M.; Strażyński, P.; et al. Poradnik Sygnalizatora Ochrony Zbóż; Tratwal, A., Kubasik, W., Mrówczyński, M., Eds.; Instytut Ochrony Roślin-PIB: Poznań, Poland, 2017; p. 248. ISBN 978-83-64655-29-6. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Sośnicowice | Winna Góra | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Precipitation [mm] | Temperature | Precipitation [mm] | |||||

| Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | |

| 2020 | −334 | 29.6 | 99 | 14.9 | −274 | 29.8 | −45.1 | a |

| 2021 | −262 | 3.0 | −57.8 | 0.7 | −211 | 24.1 | −99 | a |

| 2022 | −3162 | 53.5 | −552 | 26.7 | −2013 | 44.9 | −1206 | a |

| 2023 | −150 | 7.3 | −30 | a | −189 | 8.3 | −124 | 8.4 |

| 2024 | −6.724 ** | 89.9 | −0.502 | a | −537 * | 79.7 | −243.9 * | 64.2 |

| Year | Sośnicowice | Winna Góra | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Precipitation [mm] | Temperature | Precipitation [mm] | |||||

| Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | Effect | R2 100 | |

| 2020 | −775 | a | 243 | a | −715 | 4.9 | −317 | a |

| 2021 | −1268 | 65.8 | −351 | 69.1 | −847 | 77.7 | −758 | a |

| 2022 | −6978 | 75.2 | −2399 * | 99.6 | −4579 | 65.2 | −2890 | a |

| 2023 | −488 | a | −3243 | 57.2 | −782 | a | −564 | 40.9 |

| 2024 | −10.68 | 96.1 | 2.97 | 47.1 | −919 | 68.9 | −1263 | 98.4 |

| Dates of Migration | Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| The start of migration | 9.05 | 24.05 | 4.05 | 12.05 | 8.05 |

| The end of migration | 31.10 | 26.10 | 31.10 | 30.10 | 28.10 |

| Dates of Migration | Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| The start of migration | 8.05 | 19.05 | 24.05 | 12.05 | 1.05 |

| The end of migration | 31.10 | 31.10 | 31.10 | 31.10 | 30.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Roik, K.; Małas, S.; Trzciński, P.; Bocianowski, J. Impact of Meteorological Conditions on the Bird Cherry–Oat Aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) Flights Recorded by Johnson Suction Traps. Agriculture 2026, 16, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020152

Roik K, Małas S, Trzciński P, Bocianowski J. Impact of Meteorological Conditions on the Bird Cherry–Oat Aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) Flights Recorded by Johnson Suction Traps. Agriculture. 2026; 16(2):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020152

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoik, Kamila, Sandra Małas, Paweł Trzciński, and Jan Bocianowski. 2026. "Impact of Meteorological Conditions on the Bird Cherry–Oat Aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) Flights Recorded by Johnson Suction Traps" Agriculture 16, no. 2: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020152

APA StyleRoik, K., Małas, S., Trzciński, P., & Bocianowski, J. (2026). Impact of Meteorological Conditions on the Bird Cherry–Oat Aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi L.) Flights Recorded by Johnson Suction Traps. Agriculture, 16(2), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16020152