Effects of Dietary Starch Level and Calcium Salts of Palm Fatty Acids on Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Lambs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics

2.2. Animals, Experimental Design, and Diets

2.3. Slaughter and Carcass Evaluation

2.4. Lipid Extraction and Fatty Acid Profile

2.5. Nutritional Quality Indices

2.6. Cholesterol Determination

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Carcass Traits

3.2. Half Carcass Cuts

3.3. Internal Fat Depots and Fatness Indicators

3.4. Physicochemical Parameters of Meat

3.5. Fatty Acid Profile of Longissimus dorsi and Desaturase Activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Carcass Traits

4.2. Fat Depots and Meat Quality

4.3. Fatty Acid Profile and Desaturase Activity

4.4. Health-Related Lipid Indices

4.5. Study Limitations, Practical Implications, and Final Synthesis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AI | Atherogenicity index |

| BW | Body Weight |

| CCW | Cold Carcass Weight |

| CCY | Cold Carcass Yield |

| CEUA | Ethics Committee on Animal Use |

| CLA | Conjugated linoleic acid |

| CL | Chilling Loss |

| CSFA | Calcium salts of fatty acids |

| CSPFA | Calcium salts of palm fatty acids |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| DGAT | Acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| EBW | Empty Body Weight |

| EGIT | Empty gastrointestinal tract |

| EGS | Subcutaneous fat thickness ( |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic Acid |

| FAME | Fatty acid methyl esters |

| FGIT | Full gastrointestinal tract |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| GPAT | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase |

| GR | Grade Rule |

| HCW | Hot Carcass Weight |

| HCY | Hot Carcass Yield |

| h:H | Hypocholesterolemic/Hypercholesterolemic ratio |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HSL | Hormone-sensitive lipase |

| LaPNAR/UESC | Laboratory for Research in Nutrition and Feeding of Ruminants |

| LDL-C | ow-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RFS | Renal fat score |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acid |

| SLW | Slaughter Live Weight |

| SFT | Subcutaneous fat thickness |

| TI | Thrombogenicity Index |

| TY | True Yield |

| UESC | State University of Santa Cruz |

References

- Van Le, H.; Nguyen, D.V.; Nguyen, Q.V.; Malau-Aduli, B.S.; Nichols, P.D.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O. Fatty Acid Profiles of Muscle, Liver, Heart and Kidney of Australian Prime Lambs Fed Different Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Enriched Pellets in a Feedlot System. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prates, J.A.M. The Role of Meat Lipids in Nutrition and Health: Balancing Benefits and Risks. Nutrients 2025, 17, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnampalam, E.; Priyashantha, H.; Vidanarachchi, J.; Kiani, A.; Holman, B. Effects of Nutritional Factors on Fat Content, Fatty Acid Composition, and Sensorial Properties of Meat and Milk from Domesticated Ruminants: An Overview. Animals 2024, 14, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzuna-Orzuna, J.F.; Hernández-García, P.A.; Chay-Canul, A.J.; Díaz Galván, C.; Razo Ortíz, P.B. Microalgae as a Dietary Additive for Lambs: A Meta-Analysis on Growth Performance, Meat Quality, and Meat Fatty Acid Profile. Small Rumin. Res. 2023, 227, 107072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Lu, C.; Yang, W.; Xie, X.; Xin, H.; Lu, X.; Ni, M.; Yang, X.; et al. Effects of Dietary Clostridium Butyricum and Rumen Protected Fat on Meat Quality, Oxidative Stability, and Chemical Composition of Finishing Goats. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toral, P.G.; Monahan, F.J.; Hervás, G.; Frutos, P.; Moloney, A.P. Review: Modulating Ruminal Lipid Metabolism to Improve the Fatty Acid Composition of Meat and Milk. Challenges and Opportunities. Animal 2018, 12, s272–s281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Martin, G.B.; Wen, Q.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Shi, B.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yan, S. Palm Oil Protects α-Linolenic Acid from Rumen Biohydrogenation and Muscle Oxidation in Cashmere Goat Kids. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashkari, S.; Bonefeld Petersen, M.; Krogh Jensen, S. Rumen Biohydrogenation of Linoleic and Linolenic Acids Is Reduced When Esterified to Phospholipids or Steroids. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Livshitz, L.; Portnick, Y.; Kamer, H.; Alon, T.; Moallem, U. The Effects of High-Fat Diets from Calcium Salts of Palm Oil on Milk Yields, Rumen Environment, and Digestibility of High-Yielding Dairy Cows Fed Low-Forage Diet. Animals 2022, 12, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shpirer, J.; Livshits, L.; Kamer, H.; Alon, T.; Portnik, Y.; Moallem, U. Effects of the Palmitic-to-Oleic Ratio in the Form of Calcium Salts of Fatty Acids on the Production and Digestibility in High-Yielding Dairy Cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2024, 107, 6785–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyebade, A.; Lifshitz, L.; Lehrer, H.; Jacoby, S.; Portnick, Y.; Moallem, U. Saturated Fat Supplemented in the Form of Triglycerides Decreased Digestibility and Reduced Performance of Dairy Cows as Compared to Calcium Salt of Fatty Acids. Animal 2020, 14, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Alves, S.P.; Francisco, A.; Almeida, J.; Alfaia, C.M.; Martins, S.V.; Prates, J.A.M.; Santos-Silva, J.; Doran, O.; Bessa, R.J.B. The Reduction of Starch in Finishing Diets Supplemented with Oil Does Not Prevent the Accumulation of Trans-10 18:1 in Lamb Meat1. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 3745–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A.; Alves, S.P.; Portugal, P.V.; Dentinho, M.T.; Jerónimo, E.; Sengo, S.; Almeida, J.; Bressan, M.C.; Pires, V.M.R.; Alfaia, C.M.; et al. Effects of Dietary Inclusion of Citrus Pulp and Rockrose Soft Stems and Leaves on Lamb Meat Quality and Fatty Acid Composition. Animal 2018, 12, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Establishes Procedures for the Scientific Use of Animals; Brazil. Law No. 11.794, 8 October 2008; Diário Oficial da União: Brasília, Brazil, 2008.

- Pereira, E.S.; Teixeira, I.A.M.A.; Azevêdo, J.A.G.; Santos, S.A. Exigências Nutricionais de Caprinos e Ovinos—BR-Caprinos & Ovinos; Editora Scienza: São Carlos, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- da Cruz, C.H.; Santos, S.A.; de Carvalho, G.G.P.; Azevedo, J.A.G.; Detmann, E.; Valadares Filho, S.d.C.; Mariz, L.D.S.; Pereira, E.S.; Nicory, I.M.C.; Tosto, M.S.L.; et al. Estimating Digestible Nutrients in Diets for Small Ruminants Fed with Tropical Forages. Livest. Sci. 2021, 249, 104532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dische, Z. General Color Reactions. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 1962, 1, 478–512. [Google Scholar]

- Tebbe, A.W.; Faulkner, M.J.; Weiss, W.P. Effect of Partitioning the Nonfiber Carbohydrate Fraction and Neutral Detergent Fiber Method on Digestibility of Carbohydrates by Dairy Cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2017, 100, 6218–6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasil Regulamento Da Inspeção Industrial e Sanitária de Produtos de Origem Animal—RIISPOA 2017. Available online: https://www.sertaobras.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/RIISPOA.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cezar, M.F.; Sousa, W.H. Carcaças Ovinas e Caprinas: Obtenção, Avaliação e Classificação [Sheep and Goat Carcases: Procurement, Evaluation and Classification]; Editora Agropecuária Tropical: Uberaba, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vasta, V.; Priolo, A.; Scerra, M.; Hallett, K.G.; Wood, J.D.; Doran, O. Δ9 Desaturase Protein Expression and Fatty Acid Composition of Longissimus Dorsi Muscle in Lambs Fed Green Herbage or Concentrate with or Without Added Tannins. Meat Sci. 2009, 82, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A.V.; Nute, G.R.; Sheard, P.R.; Richardson, R.I.; Hughes, S.I.; Whittington, F.M. Fat Deposition, Fatty Acid Composition and Meat Quality: A Review. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannon, C.D.; Craske, J.D.; Hai, N.T.; Harper, N.L.; O’Rourke, K.L. Analysis of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters with High Accuracy and Reliability. J. Chromatogr. A 1982, 247, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, J.V.; Busboom, J.R.; Nelson, M.L.; Gaskins, C.T. A Direct Method for Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Synthesis: Application to Wet Meat Tissues, Oils, and Feedstuffs. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentainer, J.V.; Franco, M.R.B. Ácidos Graxos Em Óleos e Gorduras: Identificação e Quantificação; Barela: São Paulo, Brazil, 2006; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bichi, E.; Toral, P.G.; Hervás, G.; Frutos, P.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Juárez, M.; de la Fuente, M.A. Inhibition of ∆9-Desaturase Activity with Sterculic Acid: Effect on the Endogenous Synthesis of Cis-9 18:1 and Cis-9, Trans-11 18:2 in Dairy Sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 5242–5252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Siebert, B.D.; Bottema, C.D.K.; Pitchford, W.S. A Comparison of the Fatty Acid Composition of Triacylglycerols in Adipose Tissue from Limousin and Jersey Cattle. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1997, 48, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary Heart Disease: Seven Dietary Factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, H.D.R.; Freitas Júnior, J.E.d.; Leite, L.C.; Azevêdo, J.A.G.; Santos, S.A.; Pina, D.S.; Cirne, L.G.A.; Rodrigues, C.S.; Silva, W.P.; Lima, V.G.O.; et al. Protected or Unprotected Fat Addition for Feedlot Lambs: Feeding Behavior, Carcass Traits, and Meat Quality. Animals 2021, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, T.; Mazalli, M.R.; Bragagnolo, N. Avaliação Comparativa Entre Dois Métodos Para Determinação Do Colesterol Em Carnes e Leite. Ciência Tecnol. Aliment. 2004, 24, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS. Statistical Analysis System, Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013.

- Pewan, S.B.; Otto, J.R.; Kinobe, R.T.; Adegboye, O.A.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O. Nutritional Enhancement of Health Beneficial Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Muscle, Liver, Kidney, and Heart of Tattykeel Australian White MARGRA Lambs Fed Pellets Fortified with Omega-3 Oil in a Feedlot System. Biology 2021, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, E.; Cooke, R.F.; Mackey, S.; Pickett, A.; Batista, L.F.; Pohler, K.; Sousa, O.; Cappellozza, B.; Brandão, A.P. 36 Productive and Physiological Responses of Feedlot Cattle Receiving Different Sources of Ca Salts of Fatty Acids in the Finishing Diet. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Bárcena, M.; Domínguez-Vara, I.A.; Morales-Almaraz, E.; Sánchez-Torres, J.E.; Bórquez-Gastelum, J.L.; Hernández-Ramírez, D.; Trujillo-Gutiérrez, D.; Rodríguez-Gaxiola, M.A.; Pinos-Rodríguez, J.M.; Velázquez-Garduño, G.; et al. Effect of Zilpaterol Hydrochloride and Zinc Methionine on Growth, Carcass Traits, Meat Quality, Fatty Acid Profile and Gene Expression in Longissimus Dorsi Muscle of Sheep in Intensive Fattening. Agriculture 2023, 13, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Gao, A. Performance, Meat Quality, Intramuscular Fatty Acid Profile, Rumen Characteristics and Serum Parameters of Lambs Fed Microencapsulated or Conventional Linseed Oil. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 67, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Torres, R.d.N.; Ghedini, C.P.; Chardulo, L.A.L.; Baldassini, W.A.; Curi, R.A.; Pereira, G.L.; Schoonmaker, J.P.; Almeida, M.T.C.; Costa, C.; Neto, O.R.M. Potential of Different Strategies to Increase Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Sheep: A Meta-Analysis Study. Small Rumin. Res. 2024, 234, 107258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Méndez, J.L.; Estrada-Angulo, A.; Rodríguez-Gaxiola, M.A.; Gaxiola-Camacho, S.M.; Chaidez-Álvarez, C.; Manriquez-Núñez, O.M.; Barreras, A.; Zinn, R.A.; Soto-Alcalá, J.; Plascencia, A. Grease Trap Waste (Griddle Grease) as a Feed Ingredient for Finishing Lambs: Growth Performance, Dietary Energetics, and Carcass Characteristics. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 101, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadros, D.G.; Kerth, C.R. Replacing Cottonseed Meal and Sorghum with Dried Distillers’ Grains with Solubles Enhances the Growth Performance, Carcass Traits, and Meat Quality of Feedlot Lambs. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2022, 6, txac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, M.; Dobrzyn, A.; Man, W.C.; Chu, K.; Sampath, H.; Kim, H.-J.; Ntambi, J.M. Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase 1 Gene Expression Is Necessary for Fructose-Mediated Induction of Lipogenic Gene Expression by Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-1c-Dependent and -Independent Mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 25164–25171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.A.; Alves, S.P.; Santos-Silva, J.; Bessa, R.J.B. Effect of Dietary Starch Level and Its Rumen Degradability on Lamb Meat Fatty Acid Composition. Meat Sci. 2017, 123, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougouin, A.; Martin, C.; Doreau, M.; Ferlay, A. Effects of Starch-Rich or Lipid-Supplemented Diets That Induce Milk Fat Depression on Rumen Biohydrogenation of Fatty Acids and Methanogenesis in Lactating Dairy Cows. Animal 2019, 13, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungerfeld, E.M. Metabolic Hydrogen Flows in Rumen Fermentation: Principles and Possibilities of Interventions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño, D.; Toral, P.G.; Pinloche, E.; Belenguer, A.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Hervás, G.; McEwan, N.R.; Newbold, C.J.; Frutos, P. Rumen Bacterial Community Responses to DPA, EPA and DHA in Cattle and Sheep: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.P.V.; Pimentel, P.R.S.; dos Santos, N.J.A.; da Silva Júnior, J.M.; Virginio Júnior, G.F.; de Andrade, E.A.; Barbosa, A.M.; Pereira, E.S.; Ribeiro, C.V.D.M.; Bezerra, L.R.; et al. Dietary Effect of Palm Kernel Oil Inclusion in Feeding Finishing Lambs on Meat Quality. Animals 2022, 12, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, T.; Gallardo, B.; Lavín, P.; Ruiz Mantecón, Á.; Cejudo, C.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; de la Fuente, M.Á. Enrichment of Ewe’s Milk with Dietary n-3 Fatty Acids from Palm, Linseed and Algae Oils in Isoenergetic Rations. Animals 2022, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberger, D.; Eggert, A.; Kalbe, C.; Woitalla, A.; Schwudke, D. Are n- 3 PUFAs from Microalgae Incorporated into Membrane and Storage Lipids in Pig Muscle Tissues?—A Lipidomic Approach. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 24785–24794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omachi, D.O.; Aryee, A.N.A.; Onuh, J.O. Functional Lipids and Cardiovascular Disease Reduction: A Concise Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, O.; Mendizabal, J.A.; Alfonso, L.; Soret, B.; Insausti, K.; Arana, A. Adipose Tissue Modification Through Feeding Strategies and Their Implication on Adipogenesis and Adipose Tissue Metabolism in Ruminants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bosco, A.; Cavallo, M.; Menchetti, L.; Angelucci, E.; Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Vaudo, G.; Marconi, S.; Camilli, E.; Galli, F.; Castellini, C.; et al. The Healthy Fatty Index Allows for Deeper Insights into the Lipid Composition of Foods of Animal Origin When Compared with the Atherogenic and Thrombogenicity Indexes. Foods 2024, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.H.; Harris, W.S.; Belury, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Calder, P.C. Beneficial Effects of Linoleic Acid on Cardiometabolic Health: An Update. Lipids Health Dis. 2024, 23, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davinelli, S.; Intrieri, M.; Corbi, G.; Scapagnini, G. Metabolic Indices of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Current Evidence, Research Controversies, and Clinical Utility. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela-Vásquez, D.A.; Sifuentes-Rincón, A.M.; Delgado-Enciso, I.; Ordaz-Pichardo, C.; Arellano-Vera, W.; Treviño-Alvarado, V. Effect of Consuming Beef with Varying Fatty Acid Compositions as a Major Source of Protein in Volunteers Under a Personalized Nutritional Program. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, R.; Caroprese, M.; della Malva, A.; Santillo, A.; Sevi, A.; Albenzio, M. Role of Whole Linseed and Sunflower Seed on the Nutritional and Organoleptic Properties of Podolian × Limousine Meat. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramana, A.; Kurnia, D.; Firmanda, A.; Rossi, E.; AR, N.H.; Putri, V.J. Using Palm Oil Residue for Food Nutrition and Quality: From Palm Fatty Acid Distillate to Vitamin E toward Sustainability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 4728–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkah, N.N.; Despal; Retnani, Y.; Putri, N.O.H.; Rahmayuni, S.; Metania, R.D.N. Comparative Analysis of The Physical Properties and Energy Content of Rumen-Protected Fats from Crude Palm Oil for Dairy Nutrition. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1484, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Experimental Diets | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch level, g/kg DM | 220 | 220 | 420 | 420 |

| CSPFA level, g/kg DM | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Ingredients proportion, g/kg DM | ||||

| Corn silage | 400.0 | 400.0 | 400.0 | 400.0 |

| Ground corn | 190.4 | 187.3 | 485.0 | 483.2 |

| Soy hull | 322.6 | 314.1 | 0.0 | 12.7 |

| Soybean meal | 32.1 | 74.6 | 60.2 | 74.6 |

| Urea | 9.9 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 |

| Limestone | 6.5 | 12.0 | 9.7 | 14.0 |

| Mineral mixture 1 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 5.1 | 8.5 |

| CSPFA 2 | 30.0 | 0.0 | 30.0 | 0.0 |

| Chemical composition, g/kg DM | ||||

| Dry matter, as-fed basis | 663.3 | 662.2 | 664.8 | 653.8 |

| Organic matter | 961.1 | 955.5 | 961.9 | 953.5 |

| Ether extract | 54.45 | 22.23 | 60.4 | 36.5 |

| Crude protein | 135.0 | 135.0 | 135.0 | 136.1 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 466.0 | 474.0 | 323.4 | 330.5 |

| Starch | 220.0 | 220.0 | 420.0 | 420.0 |

| Residual organic matter | 85.7 | 104.3 | 23.2 | 30.4 |

| Metabolizable energy (Mcal/kg DM) 3 | 2.85 | 2.69 | 2.96 | 2.81 |

| Fatty acid profile, mg/100 g DM | ||||

| Caprylic (C8:0) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Capric (C10:0) | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Lauric (C12:0) | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.31 |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 1.99 | 1.81 | 1.78 | 1.62 |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 15.08 | 14.50 | 15.34 | 15.14 |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 4.39 | 4.71 | 4.38 | 4.69 |

| Palmitoleic (C16:1) | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.36 |

| Oleic (C18:1 n-9) | 28.10 | 28.09 | 28.09 | 27.94 |

| Linoleic (C18:2 n-6) | 46.61 | 47.13 | 46.58 | 46.87 |

| α-linolenic (C18:3 n-3) | 2.96 | 2.90 | 2.96 | 2.88 |

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| Weight, kg | ||||||||

| Slaughter weight | 34.55 | 34.91 | 34.83 | 34.63 | 0.61 | 0.780 | 0.876 | 0.458 |

| Empty body weight | 31.85 | 32.16 | 32.04 | 31.97 | 0.58 | 0.807 | 0.959 | 0.403 |

| Hot carcass weight | 17.16 | 17.19 | 17.07 | 17.29 | 0.36 | 0.968 | 0.775 | 0.303 |

| Cold carcass weight | 16.47 | 16.37 | 16.47 | 16.37 | 0.35 | 0.894 | 0.891 | 0.353 |

| Chilling loss, % | 4.01 | 4.41 | 4.58 | 3.83 | 0.25 | 0.439 | 0.165 | 0.593 |

| Carcass yield, kg/100 kg BW | ||||||||

| Hot carcass yield | 49.63 | 49.20 | 49.01 | 49.82 | 0.46 | 0.645 | 0.395 | 0.339 |

| Cold carcass yield | 47.68 | 46.85 | 47.28 | 47.19 | 0.40 | 0.363 | 0.914 | 0.440 |

| Biological yield | 53.85 | 53.41 | 53.30 | 53.96 | 0.47 | 0.655 | 0.507 | 0.422 |

| Non-carcass components, kg | ||||||||

| FGIT 1 | 6.65 | 7.08 | 6.85 | 6.88 | 0.18 | 0.291 | 0.939 | 0.917 |

| EGIT 2 | 2.66 | 2.72 | 2.76 | 2.62 | 0.12 | 0.826 | 0.600 | 0.783 |

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| Half carcass, kg | ||||||||

| Neck | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.121 | 0.237 | 0.512 |

| Shoulder | 1.45 | 1.38 | 1.36 | 1.46 | 0.04 | 0.477 | 0.314 | 0.995 |

| Rib | 1.56 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 1.56 | 0.06 | 0.259 | 0.277 | 0.559 |

| Flank rib | 1.62 | 1.77 | 1.70 | 1.69 | 0.06 | 0.267 | 0.943 | 0.205 |

| Loin | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.659 | 0.111 | 0.408 |

| Leg | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.64 | 2.69 | 0.06 | 0.964 | 0.714 | 0.863 |

| Half carcass yield, % | ||||||||

| Neck | 4.04 | 3.84 | 3.86 | 4.02 | 0.10 | 0.391 | 0.490 | 0.329 |

| Shoulder | 17.58 | 17.02 | 16.87 | 17.73 | 0.44 | 0.554 | 0.372 | 0.603 |

| Rib | 18.84 | 17.32 | 17.38 | 18.77 | 0.58 | 0.209 | 0.247 | 0.594 |

| Flank rib | 19.59 | 21.71 | 20.88 | 20.42 | 0.56 | 0.048 | 0.651 | 0.098 |

| Loin | 7.53 | 7.27 | 8.26 | 6.52 | 0.42 | 0.745 | 0.041 | 0.273 |

| Leg | 32.39 | 32.81 | 32.7 | 32.51 | 0.36 | 0.594 | 0.806 | 0.347 |

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| Internal fat depots | ||||||||

| Cavity fat, g | 90 | 150 | 90 | 140 | 20 | 0.281 | 0.446 | 0.143 |

| Perirenal fat, g | 530 | 460 | 400 | 590 | 30 | 0.223 | 0.005 | 0.196 |

| Renal fat, g | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 10 | 0.992 | 0.762 | 0.689 |

| Fatness indicators | ||||||||

| RFS 1 (1–3) | 2.77 | 2.80 | 2.66 | 2.90 | 0.05 | 0.788 | 0.035 | 0.673 |

| SFT 2, mm | 2.87 | 2.78 | 1.86 | 3.80 | 0.40 | 0.899 | 0.017 | 0.988 |

| Grade Rule meas, mm | 13.04 | 12.30 | 13.11 | 12.24 | 0.68 | 0.622 | 0.564 | 0.609 |

| Loin eye area, cm2 | 7.35 | 6.80 | 7.60 | 6.55 | 0.28 | 0.331 | 0.078 | 0.392 |

| Physicochemical parameters | ||||||||

| pH at 30 min | 6.54 | 6.56 | 6.56 | 6.54 | 0.05 | 0.854 | 0.889 | 0.587 |

| pH at 24 h | 5.62 | 5.67 | 5.64 | 5.65 | 0.05 | 0.592 | 0.972 | 0.426 |

| Temp at 0 h, °C | 32.08 | 31.83 | 32.21 | 31.70 | 0.23 | 0.584 | 0.266 | 0.072 |

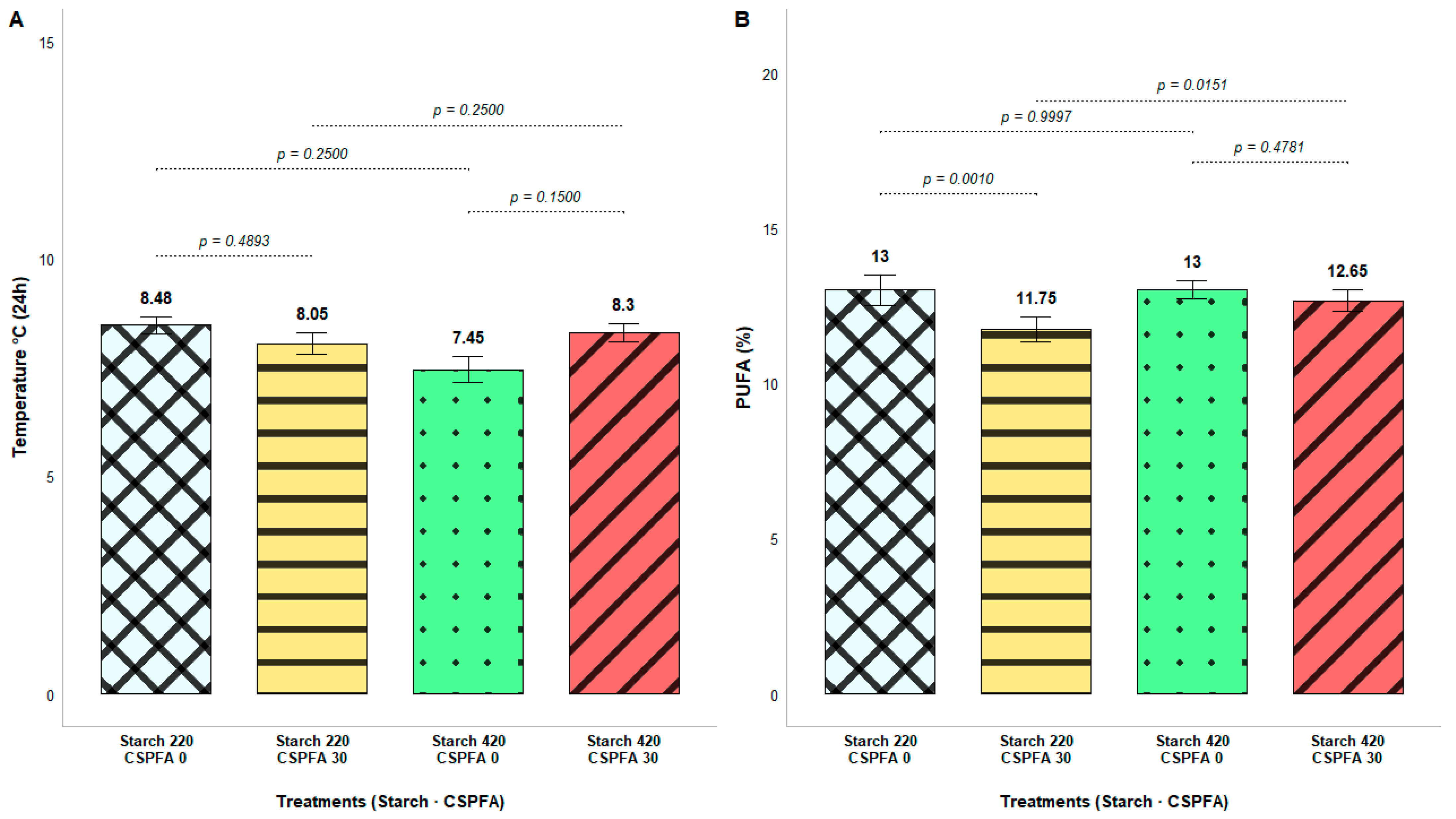

| Temp at 24 h, °C | 8.26 | 7.87 | 7.96 | 8.17 | 0.13 | 0.118 | 0.406 | 0.014 |

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| Saturated fatty acids (SFA, %) | ||||||||

| Caproic (C6:0) | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.093 | 0.552 | 0.026 |

| Capric (C10:0) | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.161 | 0.970 | 0.745 |

| Lauric (C12:0) | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.288 | 0.221 | 0.630 |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.467 | 0.375 | 0.069 |

| Pentadecanoic (C15:0) | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 0.203 | 0.581 | 0.748 |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 22.95 | 23.66 | 21.01 | 25.61 | 0.82 | 0.441 | <0.001 | 0.487 |

| Heptadecanoic (C17:0) | 1.17 | 1.20 | 1.52 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.467 | <0.001 | 0.088 |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 23.48 | 19.93 | 20.78 | 21.62 | 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.496 | 0.153 |

| Arachidic (C20:0) | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.002 |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA, %) | ||||||||

| Palmitoleic (C16:1) | 2.20 | 2.18 | 1.49 | 2.89 | 0.18 | 0.681 | <0.001 | 0.050 |

| Heptadecenoic (C17:1) | 1.51 | 1.39 | 1.38 | 1.53 | 0.11 | 0.528 | 0.422 | 0.011 |

| Elaidic (C18:1n9t) | 3.27 | 3.14 | 3.16 | 3.25 | 0.06 | 0.362 | 0.498 | 0.440 |

| Oleic (C18:1n9c) | 31.72 | 32.94 | 34.79 | 29.88 | 1.16 | 0.463 | 0.010 | 0.152 |

| Eicosenoic (C20:1) | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 |

| Erucic (C22:1n9) | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Nervonic (C24:1) | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.034 | <0.001 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA, %) | ||||||||

| Linolelaidic (C18:2n6t) | 9.00 | 8.77 | 8.81 | 8.96 | 0.07 | 0.110 | 0.298 | 0.390 |

| α-Linolenic (C18:3n3) | 1.44 | 1.45 | 1.53 | 1.36 | 0.05 | 0.929 | 0.203 | 0.482 |

| Rumenic (C18:2c9t11) | 0.90 | 1.11 | 1.32 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.379 |

| CLA (C18:2t10c12) 1 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.01 | <0.001 | 0.039 | 0.896 |

| Eicosatrienoic (C20:3n3) | 0.16 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| DHA (C22:6n3) 2 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.495 |

| EPA (C20:5n3) 3 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.023 | <0.001 |

| Item | SCAGP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starch | 0 | 30 | p Value | |

| Caproic (C6:0), % | 220 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.959 |

| 420 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.042 | |

| p Value | 0.550 | 0.041 | ||

| Heptadecenoic (C17:1), % | 220 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.400 |

| 420 | 0.21 | 0.18 | <0.001 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.978 | ||

| Arachidic (C20:0), % | 220 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.400 |

| 420 | 0.82 | 0.73 | <0.001 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.978 | ||

| Eicosenoic (C20:1), % | 220 | 0.25 | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| 420 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.006 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Nervonic (C24:1), % | 220 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.596 |

| 420 | 0.15 | 0.21 | <0.001 | |

| p Value | 0.145 | <0.001 | ||

| Erucic (C22:1n9), % | 220 | 0.20 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| 420 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.809 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | 0.809 | ||

| Eicosatrienoic (C20:3n3), % | 220 | 0.23 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| 420 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.848 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| EPA (C20:5n3) 1, % | 220 | 0.21 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| 420 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.017 | |

| p Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| SFA 1 | 48.74 | 45.02 | 44.47 | 49.28 | 1.00 | 0.221 | 0.005 | 0.228 |

| MUFA 2 | 39.32 | 40.38 | 41.43 | 38.29 | 0.97 | 0.492 | 0.048 | 0.219 |

| PUFA 3 | 12.36 | 12.82 | 12.99 | 12.19 | 0.15 | 0.021 | <0.001 | 0.027 |

| Atherogenicity index | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.868 | <0.001 | 0.258 |

| Thrombogenicity index | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.659 | <0.001 | 0.210 |

| h:H 4 | 2.21 | 2.16 | 2.50 | 1.86 | 0.11 | 0.756 | 0.003 | 0.281 |

| n-6/n-3 ratio | 5.10 | 4.17 | 4.29 | 4.98 | 0.19 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.252 |

| Cholesterol (mg/100 g) | 58.87 | 58.44 | 59.15 | 58.16 | 2.46 | 0.937 | 0.859 | 0.837 |

| Item | Starch (S), g/kg | CSPFA (FA), g/kg | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220 | 420 | 0 | 30 | S | FA | SxFA | ||

| Δ9-desaturase 14 | 19.59 | 57.57 | 40.58 | 36.58 | 8.89 | 0.040 | 0.816 | 0.945 |

| Δ9-desaturase 16 | 27.71 | 15.23 | 36.20 | 6.75 | 7.51 | 0.389 | 0.054 | 0.644 |

| Δ9-desaturase 18 | 60.43 | 42.18 | 52.54 | 50.07 | 5.94 | 0.154 | 0.842 | 0.959 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ferreira, J.M.S.; Rodrigues, H.P.; Pereira, M.I.B.; Trajano, L.S.; Souza, L.L.; Alba, H.D.R.; de Freitas Junior, J.E.; Carvalho, G.G.P.d.; Pina, D.d.S.; Santos, S.A.; et al. Effects of Dietary Starch Level and Calcium Salts of Palm Fatty Acids on Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Lambs. Agriculture 2026, 16, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010098

Ferreira JMS, Rodrigues HP, Pereira MIB, Trajano LS, Souza LL, Alba HDR, de Freitas Junior JE, Carvalho GGPd, Pina DdS, Santos SA, et al. Effects of Dietary Starch Level and Calcium Salts of Palm Fatty Acids on Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Lambs. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Joyanne Mirelle Sousa, Hérick Pachêco Rodrigues, Maria Izabel Batista Pereira, Lais Santos Trajano, Ligia Lins Souza, Henry Daniel Ruiz Alba, José Esler de Freitas Junior, Gleidson Giordano Pinto de Carvalho, Douglas dos Santos Pina, Stefanie Alvarenga Santos, and et al. 2026. "Effects of Dietary Starch Level and Calcium Salts of Palm Fatty Acids on Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Lambs" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010098

APA StyleFerreira, J. M. S., Rodrigues, H. P., Pereira, M. I. B., Trajano, L. S., Souza, L. L., Alba, H. D. R., de Freitas Junior, J. E., Carvalho, G. G. P. d., Pina, D. d. S., Santos, S. A., & Azevêdo, J. A. G. (2026). Effects of Dietary Starch Level and Calcium Salts of Palm Fatty Acids on Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Lambs. Agriculture, 16(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010098